Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

ROW, take a bow

Of Love and Other Demons.

Kristin here:

There are dozens of American films playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, but the vast majority of them are documentaries. Once again the Rest of the World (ROW) gets its turn. David has started by handling a group of Asian films (one of the festival’s specialities), and I’ve got films from three continents to describe.

Morgen (Romania; dir. Marian Crisan, 2010)

Morgen opens with the camera following the hero, Nelu, riding his motorcycle toward a border checkpoint. The border guards question him and discover that he’s been fishing and caught a large carp. One guard is inclined to let him pass, but the stricter one insists that he can’t take it across. We may think that this guard wants the fish for himself, but when Nelu finally empties his bucket into the gutter, the guards retire into their office and the fish is left to flap pathetically as Nelu rides across the border.

It’s a simple, obvious way to set up the absurdity and arbitrariness of border controls within the European Union, but it also sets up the character of the two guards, who will figure later when a more important border-crossing is attempted.

A security guard at a local grocery store, Nelu lives with her termagant wife in a modest farmhouse near the Hungarian border. During one of his regular fishing trips, he spots a forlorn Turkish refugee hiding from the border police. He takes the man home. Although the Turk’s dialogue isn’t subtitled, he mentions Germany often enough for Nelu and us to grasp where the man is heading. Not having a clue about how to help, Nelu hides the Turk in his cellar, and despite the wife’s objections, he gradually becomes a sort of handyman around the place. Nelu keeps telling him, “Morgen” (“tomorrow”) suggesting that he vaguely hopes to do something eventually.

Virtually every scene occupies a single take, some long, some not. But these aren’t the deliberately lugubrious shots of a Béla Tarr. In its quiet way, Morgen is a comedy, and an entertaining one. Nelu’s passivity presents the slowly growing friendship between him and the Turk without the film tipping over into sentimentality, and there is genuine suspense in the scenes of threatened encounters with the border police and guards. It’s a charming film, reminiscent of some of the Czech New Wave comedies of the 1960s.

12 Angry Lebanese: The Documentary (Lebanon; dir. Zeina Daccache, 2009)

The film’s subtitle is intended to differentiate it from a play of the same name that was produced within the largest prison in Lebanon, starring a group of prisoners. In the United States the director, Leina Daccache, studied drama as a method of prisoner habilitation. She managed to get funding to try the first ever use of this method in Lebanon, though there followed a year of negotiations before government officials allowed the experiment. The  program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

The process of casting and rehearsals took fifteen months, and Dacchache documented the process with a cinematographer shooting digital video. There are atmospheric shots of the prison, scenes of the rehearsal and premiere performances, and interviews with the prisoners who play the lead roles. The resulting images are necessarily not of high photographic quality, but the intrinsic drama of the situation more than makes up for that.

Although 45 prisoners were involved in the performances, Daccache wisely concentrates on the central dozen, composed of several murderers, some drug dealers, and a rapist. Even in the early interviews, before rehearsals have progressed very far, all are remarkably articulate and thoughtful about their own lives and how they ended up in prison. (Presumably they were chosen because they could speak so revealingly.) By the end, they realize that they have learned all the things they were deprived of during their early years, most notably how to function as a group and work toward a goal beyond their own wants.

The film creates a moving and convincing image of the effects art can have in changing the lives of prisoners thought to be beyond rehabilitation. It’s a rare documentary that has an immediate positive effect on society. In this case, there had been a law providing for early release for prisoners on the books in Lebanon for several years. As Daccache revealed in a Q&A after the film, that law was never put into practice until after the successful run of the play.

Of Love and Other Demons (Costa Rica/Colombia; dir. Hilda Hidalgo, 2010)

Filmmaking on a sophisticated level continues to spread through Latin America. Hidalgo’s adaptation of Gabriel García Márquez’s novella seems to have been shot in Costa Rica, with financing and other technical work done in Colombia.

The story is relatively simple. The teenage daughter of a local nobleman in colonial Cartagena is bitten by a rabid dog. It’s not clear whether she has contracted the disease, but she is taken to a local nunnery and locked away in a cell for observation. Somehow the diagnosis is changed to demonic possession, mainly because the girl has been raised by her family’s black slaves and has been steeped in their native, highly non-Catholic beliefs. A young, philosophically minded priest is sent to exorcize her but ends up falling in love with her instead.

In contrast to the slapdash editing so common in contemporary Hollywood films, it’s a pleasure to see a film where every shot has been intelligently planned. The Variety review compares cinematographer Marcelo Camorino’s lighting to Caravaggio paintings, an apt parallel. The heroine’s implausibly dense, waist-length red curls are lovingly dwelt upon, as in the shot illustrated at the top of this entry. The sense of magical realism emerges most powerfully in a dazzling sequence in which the priests watch a solar eclipse. A moon far larger than it would normally appear passes across an equally huge sun, creating a fiery corona that hovers above the open sea (see below).

Microphone (Egypt; dir. Ahmad Abdalla, 2010)

Ahmad Abdalla, whose first feature Heliopolis we blogged about last year, is back with his second. Microphone is much more polished, reflecting a longer shooting time and perhaps a bigger budget. The same lead actor, Khaled Abol Naga, returns as Khaled, a young man returning to his native Alexandria after seven years in the United States. Finding that the girl he had hoped to marry has decided to go abroad to do her Ph.D., he sets out to help set up a studio in a warehouse. Gradually he gets drawn into the more popular goings-on in the working-class districts, notably rap music, skateboarding, and graffiti art. After a hypocritical government arts bureaucrat promises funding and then reneges, Khaled sets out to stage a concert in the open air, only to be confronted by Islamic and police opposition.

While Heliopolis simply followed a set of disparate characters around the upscale Cairo suburb, Microphone has a more ambitious structure, flashing back to stages in Khaled’s disillusioning reunion with his ex-girlfriend–flashbacks that are presented out of order within the ongoing scenes of his growing interest in street art. The result has the sophistication of a modern festival film.

The film presents a grim take on government repression and censorship. Abdalla, on hand to answer questions, told us that we had seen the full version, which he fully expects will be cut by the Egyptian authorities. Even  though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

Indeed, one audience member, a young man from Alexandria, objected to the portrayal of his beautiful home city as ugly, since the story is set mostly in poorer neighborhoods. Abdalla defended the approach, saying that the film is intended to portray a certain arena of life in the city realistically, with the incidents in the film being derived from stories recounted to him by the actual young artists who played themselves.

The film’s criticism of the Egyptian government may seem rather tame by western standards. Yet a telling change in the ending reveals how current are its concerns. There is a street vendor selling pop-music cassettes out of a cardboard box who returns at intervals as a motif, though he has little to do with the story. The film was to have had an upbeat ending involving the vendor. But in June, when the filming was still going on, the beating death of Khaled Said by two policemen outside an internet cafe in Alexandria took place. The filmmakers altered their ending, with police chasing the cassette vendor and starting to beat him. (The trial of the real-life policemen is ongoing and has every appearance of being a sham.)

The Man Who Will Come (Italy; dir. Giorgio Diritti, 2009)

This film dramatizes a set of massacres of villagers perpetrated by Nazi soldiers in the region around Bologna in 1944 in response to the people’s support of partisan troops. It’s a tale told through the eyes of Martina, a girl of about 9 who has been mute since her newborn brother died in her arms. (No points for guessing whether she regains speech by the end.) Since the main peasant family to which Martina belongs is fictional, there was no necessity to make her mute, and unfortunately the result is that she has very little personality. She is shown being bullied by some boys early on, which presumably is intended to make us sympathize more with her, though the choice of a pretty little girl as the point-of-view figure entails a pretty automatic sympathy on the audience’s part.

The film is largely episodic, with the life of the central peasant family and their neighbors being vividly conveyed as we see them at their tasks. At intervals, Nazis are seen near the village, and the partisans recruit young men and have some early successes. But since Martina understands little of what goes on around her, she has no particular goal, though eventually she gains one as the Germans begin the massacre and she is left to save another newborn brother. I found it difficult to keep track of the lengthy scene of the rounding up of the peasants and their executions in various venues. One group is taken to a chapel in a graveyard to be killed, another is killed by the church, and so on, but it is difficult to tell one group from another or to get a sense of how many peasants were slaughtered. (The original total was somewhere around 750 to 800.)

Overall the cinematography conveys the setting well, both the hilly, wooded landscapes and the ancient stone farmhouses. There’s a very effective scene where the townspeople take refuge in a church and Martina’s older sister runs back and forth from the bell-tower, reporting the fighting below, which we see only from far away, as she does. In fact, this sister is a more engaging character than Martina, and would have made a better point-of-view figure. Another gripping scene comes when she, seriously wounded in the massacre, is suddenly pulled out of the pile of bodies and given first aid by a Nazi officer. She’s mystified as to why he’s doing this, though we hear him tell another soldier that she reminds him of his wife. It may seem as if the insanity of war would be more effectively conveyed through a thoroughly naive character’s eyes, but at least in this case, somehow that doesn’t work.

Of Love and Other Demons.

Dragons, tigers, one bear

Sawako Decides.

DB here:

As has become our habit, we’re at the Vancouver International Film Festival, gulping down movies. The perennial Dragons and Tigers collection of recent Asian film is especially ripe this year, at over forty-three features and many shorts, and of course there are several other choices, across ten venues, competing for your eyeballs. Herewith, my first dispatch from this sunny, hospitable city. Kristin will follow up soon.

A girl, a boy, and many guns

She’s completely ordinary, “below-middle,” as she proclaims. Her contribution to a conversation is always a couple of steps behind. She spends her nights watching TV and guzzling beer. She has lost five jobs and been dumped by five boyfriends. Her main relaxation seems to be colonic irrigation. But when she’s fired and her father lies dying, she returns to her hometown to take over his clam-processing factory. She brings in tow her latest paramour, a twitchy ex-toy-designer who enjoys knitting.

Such is Sawako, who has the face of an anime princess and the mind of . . . well, that’s part of the problem. Psychologically, she’s the opposite of those fast-comeback youngsters spraying American indies with quirk. She mopes in her father’s factory, absently minds her boyfriend’s daughter, shrugs off the malice of her former teen friend, and ignores gossip about why she left town in the first place. Nothing can shake her obdurate passivity. She won’t fight. With beer as her only solace, Sawako seems not the stuff of drama at all.

But drama, tradition tells us, pivots on decisions (usually bad ones). Sawako Decides surrounds a woman resigned to misfortune with a range of eccentrics who do take action, sometimes recklessly. There are the older women who work in the processing plant, the faithless boyfriend with his powder-blue sweaters, the vindictive ex-friend, the alcoholic father who rips off his IV for a fight, even a college girl doing research on toxic clams. When Sawako finally chooses to do something, she’s acting, she says, for all the “below-middle” people—that is, nearly all of us. Associated throughout with body wastes, she turns the tide: Even the feces she spreads on the family garden yield a giant watermelon. The film ends with a trim long take in which Sawako finally blows her top and finds an agreeably aggressive use for her father’s bones. Ishii Yuya’s film shows how the blankest of characters can, if treated with wary respect, yield engaging cinema.

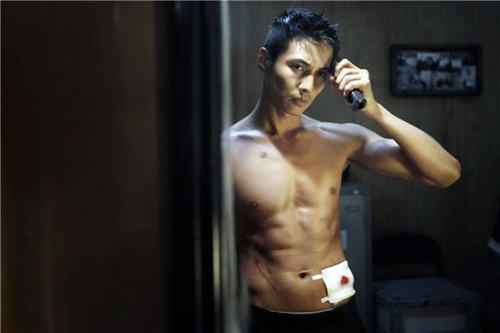

Won Bin is probably best known to Western audiences as the scatty, tormented son in Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, but he’s become a major Korean heartthrob. I know this because of the collective gasps and shrieks that greeted moments of The Man from Nowhere, a grisly action picture by Lee Jeong-Beom. Won plays a retired government agent running a pawnshop in a seedy neighborhood. He reenters the underworld to rescue a neighbor woman’s daughter, snatched by a drug gang for a little child labor and organ-stripping. He is a Bourne-style killing machine, and he is given plenty of chance for some rousing brawls and gunplay (though most of his fighting skills can be credited to editing and blur-o-vision camerawork). Mountainous, bug-eyed, and ominously silent bad guys round out the cast. Director Lee is also shrewd enough to feed the fanbase. There are some touching moments between the girl and the hitman; she even gives him a decorative fingernail while he sleeps. The film’s pin-up image shows Won, stripped to the waist at the mirror, clipping his hair, a bloodied groin-level bandage artfully completing the ensemble. (If you can’t wait, see the end of this entry.) A limited North American release comes later this month.

Excess, two varieties

I’ve written briefly about Sono Sion’s perverse coming-of-age tale Love Exposure, and this year’s Vancouver fest brings us his latest, Cold Fish. Who would have thought that business rivalry between two tropical-fish vendors would lead to the carnage we see here? Meek Shamoto has a sexy wife and a disobedient teenage daughter. An aggressively friendly rival, Murata, owns a much bigger shop and offers to take the wayward Mitsuko under his wing. Soon Murata reveals that he plunges as voraciously into murder as he does into fish connoisseurship, and Shamato is caught up in the untidy business of human butchery.

A charnel-house of copulation and dismemberment, the film takes place in a vacuum; a police investigation comes virtually as an afterthought. Cold Fish is more linear and genre-bound than Love Exposure, but when the quiet march of Mahler’s first symphony signals the onset of dread you recall the wilder side of the earlier movie. Also carrying over is the blasphemous use of Christian iconography, associated here with slaughter and child abuse. The film is in the tradition of The Family Game and other dismantlings of Japanese domesticity. Once again, you can find as much lust and murder as you like just by looking into the nuclear family. In this case, the choice offered to the father is straightforward: be a wimp or be a brute. Sono aims to outrage, but once you know that you’re in for a bloodbath, you settle comfortably in for an engrossing exercise in splatter, Japanese-style.

At the other extreme is The Drunkard, Freddy Wong’s adaptation of Liu Yichang’s well-regarded novel about a dissolute writer. Lau wants to be the Hemingway of Hong Kong, but his addiction to alcohol and his inability to love drive him into writing film scripts, pulp fiction, and eventually pornography. The fear of selling out your artistic ideals may not strike a chord in the age of Damien Hirst, but in the 1960s, the novel’s epoch, it held sway over literary culture. Lau’s struggle is presented as an oscillation between his collaboration on a literary magazine and his grubby business dealings with movie producers and publishers. In between, and constantly, he smokes and drinks. The women along his downward path include a seventeen-year-old temptress who has read Lolita, a sincere working woman who offers him lodging and sex, and an aged landlady who thinks he’s her son. His drunken refusal to sympathize with their needs brings sorrow to nearly all and death to a couple of them.

The Drunkard is shot in an unusual style. There are almost no long shots; the framing above is about as far back as the camera gets. Nearly everything happens in medium-shot and close-up. Wong was partly making a virtue of necessity, since streets and shops of the Hong Kong of the 1960s could not be reconstructed on the film’s budget. The positive result is an unrelenting concentration on Lau and repetitive bits of his behavior–gesturing with a cigarette, pouring whisky, or fading into a blackout. From scene to scene, we’re confined to his awareness, broken by fragmentary memories of wartime Japanese invasion. Only after his binges do we learn how viciously he acted when under the influence.

This tightly circumscribed world is enhanced by shots focusing on only a curtain edge or a streaked whisky glass, while people and surroundings drown in a blur. Shot on the Red camera, The Drunkard shows that high-definition digital is perfectly capable of giving foregrounds or backgrounds a hallucinatory softness. That softness, you could argue, is a correlative for the drunkard’s vision, locked on details and oblivious to the flux of human passions around him. In its effort to render the glowing warmth of alcohol, Wong and his cinematographer Henry Chung have given digital cinema a decisively subjective turn.

Two men and a sofa

Ho Wi Ding’s Pinoy Sunday is a heartfelt, low-pressure comedy-drama that makes some telling points about cultural dislocation. Dado and Manuel are Filipino “guest workers” in Taiwan. Friends since high school, they work in a bike factory and live in the factory dormitory. In their dreams they imagine installing a lavish raspberry-bright sofa on the dorm roof where they could lounge, drink beer, and look at the stars. One day, visiting Pinoy on break, they see that very sofa abandoned on the street.

Emigrant Filipino workers fill the lower-rank jobs in many Asian countries, and I’ve seldom seen fiction films show the texture of their lives. Through Dado’s phone conversations with his family, the pain of loss comes through. He buys his daughter a Barbie for her birthday, even while he carries on an affair with an émigré woman (who herself has a husband and family back home). Manuel is on the make, but with winning naivete has a knack for picking the wrong women to idealize (hookers, policewomen). In a way, the sofa becomes the tangible emblem of not just material comfort but the men’s aspiration for a more stable life.

With something of the wistful satire of 1960s Eastern European films like Intimate Lighting or The Fireman’s Ball, Pinoy Sunday turns an anecdote into a mini-saga. (It was inspired by Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe.) At the canonical turning point (circa 28:00), Manuel persuades Dado to carry the sofa back to their dorm before the gates close. The ensuing misadventures recall Laurel and Hardy, but with stronger sentiment.

Their journey reminds them they are outsiders. A TV reporter thinks they’re Malaysian. Trying to explain an accident to a cop puts them at a disadvantage. Their inability to speak Mandarin gives us a crash course in how gestures, English phrases, and situational logic are pieced together to communicate across cultures. At the height of the men’s frustration, there is a poignant musical interlude that evokes magic realism, but that moment is immediately undercut by sober reality. Yet our concern for these two resilient strivers is rewarded with a sort of happy ending.

Finally, the bear of this entry’s title is Alex Law’s Echoes of the Rainbow, the Hong Kong film that won the Crystal Bear at this year’s Berlin festival. I haven’t seen it yet but I hope eventually to pass you some words about it.

The Man from Nowhere.

Wrapping up the ROW

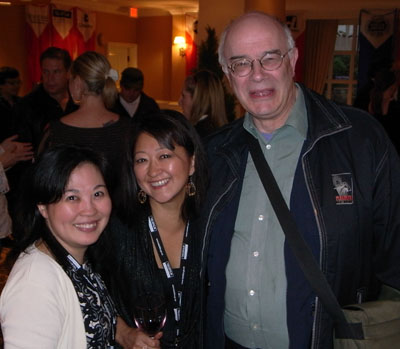

Paparazzi swarm over the nominees for the Dragons and Tigers Award at the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Kristin here:

Some final films from VIFF

So far Central American countries have produced fewer films than their neighbors to the north and south. So I couldn’t pass up The Wind and the Water, the first fiction feature made in Panama. Made by a collective of fifteen young indigenous people from the Kuna Yala archipelego under the leadership of MIT graduate and first-time director Vero Bollow, it’s a tale of threats to the paradisiacal island by developers who want to build a giant hotel there. It also reflects temptations for young people to desert their traditional lives on the islands for the attractions of nearby Panama City.

The contrast between the islands emerges through a simple tale. Machi, a young man from the islands, goes to the city for schooling and finds it grim and threatening. Rosy, a transplanted native who grew up there, aspires to be a model.

She returns to the islands for her grandfather’s funeral. Confronted with crude latrines and fish-head stews, she is initially miserable but gradually falls under the spell of the area’s beauty. Meanwhile her father works for the group planning to move the islands’ population to a new suburb and build their resort.

The plot is based loosely on that population’s vigorous efforts—successful so far—to fend off efforts of outsiders to gain control of the islands. I was reminded while watching it of the many classic documentaries of the 1930s and 1940s, like Song of Ceylon, shot by Americans and Europeans in exotic locales. For decades film scholars deplored the fact that the people who formed the subjects of such films were being portrayed by outsiders. The Wind and the Water, though a fiction film, has a strongly documentary thread running through it, but this time it is the local population making a film about their own situation.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

In some ways, Ozcan Alper’s debut feature, Autumn, is a classic art-house film. Yusuf, a student radical, is released after ten years in prison because he has a fatal lung disease. He returns to his home. He returns to his rural home in the eastern Turkish mountains and settles in with his widowed mother, keeping his illness secret. He tutors a local boy in math and perhaps falls in love with a melancholy prostitute struggling to support her child.

Many of the scenes consist of the hero lying or sitting in the yard, contemplating the surrounding mountains as autumn slowly changes them. David found the lack of dramatic action and the slow pace of the scenes to be overly familiar conventions of art cinema. No doubt the hero’s goals are de-dramatized, as when he promises a bicycle to the student should he succeed in mother or when very late in the film he decides to help the prostitute. There is one central motif that becomes overly emphatic. When Yusuf first notices the prostitute, she is buying a Russian novel; they simultaneously sit alone watching the same broadcast of Uncle Vanya; eventually she tells Yusuf that he’s like a character out of Russian literature. The film’s tone successfully suggests this comparison without our needing to have it made explicit.

To me, the success of the film arises from the director’s integration of the landscape into the story. The prominence of the rugged landscape and the care with which the story is linked to the fall of leaves and the creeping of snow down the mountainsides lifts this above standard art-house fare. In this case, the fading of the year, beautifully brought into a central role by the cinematography, becomes linked more subtly to the hero’s plight.

Kill Daddy Goodnight, an Austrian film by veteran director Michael Glawogger, starts with a promising premise. The protagonist Ratz hates his father, a cold and critical government minister, and creates a videogame, “Kill Daddy Goodnight,” to wreak a fantasy revenge. Summoned by Mimi, a friend with whom he may or may not be in love, he abruptly flies to New York. She wants him to renovate the basement hideaway of her grandfather, a fugitive Nazi war criminal. Initially revolted, over the course of his work he comes to like the old man. Ratz also manages to find a sleazy internet entrepreneur willing to offer “Kill Daddy Goodnight” on his website, where it becomes an immediate success. Interspersed with this plot are scenes of an unidentified man (below) recording testimony against and visiting his childhood friend, who had worked for the Nazis during the war and killed his father.

So far, so good. But the film’s already complex plot is overburdened by strong hints of Ratz’s incestuous desire for his sister, a thread that comes to little. Mimi’s motivations are confusing, and it’s hard to sympathize with any of the characters. Perhaps that was the intention, but my sense was that the two intriguing plotlines, which could have fit neatly together, were diffused by distractions and uncertainties.

I didn’t get to many documentaries, but being a lover of Vivaldi’s vocal music, I had to see Argippo Resurrected. It’s the fascinating tale of how Czech conductor and musicologist Ondrej Macek ingeniously tracked down the lost 1730 opera, which had originally been composed for Prague. He then staged the piece in one of the two perfectly preserved court theaters of the era, the Castle Theatre at Cesky Krumlov, two hours outside of Prague, near the Austrian border.

The other is at Drottningholm, outside Stockholm, where in 1999 David and I had the privilege of seeing The Garden, a new opera about Linnaeus. (It was the first premiere at the theater since it was sealed in the 18th century.) The original candles have prudently been replaced by electric replicas of one candlepower each, flickering realistically. The Cesky Krumlov theater still uses real candles to light both the stage and the musicians’ stands. I guess this says something about fire codes in Eastern Europe. I for one would be happy to risk it in order to have a thoroughly authentic experience, especially if a Vivaldi opera was playing.

It’s a complicated story to fit into 62 minutes. Director Dan Krames took a clever and effective approach, starting backwards. He shows the theater first, with its wooden framework, sets, and stage machinery. He then goes on to introduce some of the musicians and singers, in the process explaining the concept of authentic performance style to those who may not be familiar with it. We also get to see some short excerpts from rehearsals, so that we come to know the opera a little. Only then does Krames proceed to the tale of Macek’s search for the original manuscript and his laborious piecing-together of the individual arias. Macek makes an engaging subject, though he is so self-deprecating about his discovery that the film has to include another musicologist to explain just how extraordinary the accomplishment was.

Finally Macek takes us on a tour of Venice, showing the few surviving places associated with Vivaldi, whose life is little documented. Along the way, there are further excerpts from rehearsal for the production shown, featuring a collection of excellent singers. Krames told me that Argippo Resurrected should be released on DVD in about a year. In the meantime, a live recording of Macek’s production is available as a 2-CD set.

Some final photos

Film festivals aren’t just for watching movies, of course. They’re for seeing old friends, meeting new ones, and sharing meals—including the festival’s wonderful hand-made waffles—to talk about what we’ve seen. As usual, David had his camera in hand nearly all the time, as the accompanying images show.

Theresa Ho, Eunhee Cha, and Tony Rayns: Three key players in the Vancouver Festival.

Chris Chong (director of Karaoke) and Liu Jiayin (Oxhide II).

Bob Davis, of American Cinematographer, and Noel Vera, Critic after Dark.

Canadian corner: Lisa Roosen-Runge, Shelly Kraicer, and Peter Rist.

Get your Terimayo, Oroshi, and Okonomi here: Japadog, a Vancouver Institution.

Wantons and wontons

Oxhide II.

DB here, with more from the Vancouver film fest:

Two of the more innovative films I saw evoked film history—one explicitly, the other obliquely. Raya Martin’s Independencia is part of a planned series devoted to the history of the Philippines, told from the bottom up. In this first installment, villagers flee into the jungle to hide from the American “liberation” of their islands. The film centers on a mother and son who, joined by a woman the son finds, create a new family. After years, the son and the woman have a child, but their new life is threatened by the encroachment of the invaders.

What sets Independencia apart is Martin’s effort to create the look and feel of a 1930s fiction feature. He shot the movie wholly in a studio, and the evidently faked backdrops are counterbalanced by gorgeously controlled lighting effects, and even dashes of color. Since virtually no Filipino films survive from this period, Martin gives us less a pastiche than a possibility, a sort of hypothetical archival film. The fact that the film makes aggressive use of Dolby sound, especially during a tremendous storm sequence, only adds to the sense of history being reimagined for today.

More traditional, at first glance, is Puccini and the Girl, a historical drama by Paolo Benenuti and Paolo Baroni. Facts of the case: In 1909, a maid in Puccini’s Tuscan villa, accused of being his concubine, committed suicide. But an autopsy revealed that she was a virgin.

The film’s reconstruction of what happened behind the scenes, tracing the veins of jealousy and deceit running through the household, relies on recent research into the tragedy.

At the same time, we have an homage to silent cinema. In most scenes we hear no dialogue: actors whisper at a distance from us, or simply conduct themselves without speaking. What words we do hear are recited pro forma (the Mass) or sung (in a waterside tavern, or in nondiegetic accompaniment). There is only one line of conversation, and that is given greater saliency by being a cry from the heart.

So we’re largely confronted with a silent film, accompanied by music and sound effects. To add to the estranging effect, characters communicate chiefly through letters and telegrams—exactly as in the films of the period. We hear the letters’ text read aloud, but the sense of stately compositions propelled by written commentary, distinctive features of 1910s cinema, remains. An unwitting homage, perhaps, but one that pleased this fan of classic tableau cinema.

Independencia was part of the Dragons and Tigers thread, one of the hallmarks of the Vancouver event. Year after year it gives an unequaled view of current Asian cinema. This year’s program, assembled by Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, was at least as fine as ever. Eight films compete for the $10,000 prize given to first or second features. The winning film, Eighteen by Jang Kun-jae, centered on the familiar situation of teenage lovers separated by parents and school pressures. I didn’t see all the competitors, but my own favorite was Chris Chong’s Karaoke, a Malaysian story of a young man coming to terms with his mother’s decision to sell her karaoke bar. The first ten minutes are quite creative, disorienting the audience through complicated sound mixing, while the boy’s community, devoted to the production of palm oil, is presented with a documentary directness.

Outside the competition, I saw several Asian films of consequence. I’ve already discussed Yang Heng’s Sun Spots and Bong Joon-ho’s Mother. Ho Yuhang’s At the End of Daybreak marks a shift from his lyrical first feature, Rain Dogs, which I reviewed at Vancouver in 2006. A plot situation close to that of Eighteen is treated in much darker tones. A young man falls in love with a high-school girl, but he’s driven to murder by her growing indifference to him. The familiar elements of furtive sex, drinking parties, and demands from the girl’s family for reparations are given a noirish treatent. Ho’s admiration for American crime novels shows in his increasingly bleak handling of the affair. Here the femme fatale is a high-school girl, and the entrapped male’s revenge is complicated by an unexpected erection.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Bong Joon-ho has been something of a leitmotif on this site lately, with my comments on Influenza and Mother. Under the rubric “Bong Joon-Ho & Co.,” Dragons and Tigers screened a collection of shorts paying tribute to the Korean Academy of Film Arts. Most were from the 2000s, but Kim Eui-suk’s Chang-soo Gets the Job, dated from 1984. Focusing on a gang of teenage purse snatchers, Kim’s film was a little rough technically, but it built its story deftly. The quality of the rest was quite strong, with the grisly and wacky Anatomy Class (2000, Zung So-yun) being a high point. Meanwhile, Bong’s Incoherence (1994) shows that his urge to deflate official hypocrisy, seen in Memories of Murder and The Host, was already present in his student days.

My admiration for Hirokazu Kore-eda runs high, as I indicated in my discussion of Still Walking at last year’s VIFF. But Air Doll, while full of vagrant pleasures, left me unsatisfied. The Kafkaesque premise, derived from a manga, is that an inflatable saucy-French-maid dolly comes to life, endowed with speech and movement but retaining her seams and air valve (both of which will figure in the plot). Her sad-sack owner doesn’t notice the transformation, but while he’s at work, she takes a job at a video store and wanders the city.

The aim, I think, is to defamiliarize ordinary city life by seeing it through Nazomi’s eyes. The fact that a sex effigy is the most innocent character in the movie is part of the point. Makeup, money, and fashion start to seem extensions of sad, solitary eroticism, and the line between mainstream movies and porn gets blurred. But all the thematic elements didn’t blend very well, and at moments, as during the music montages showing people’s desperate loneliness, I worried that for once Kore-eda had slipped into conventional sentimentality. The tone also shifts, with a climax that revises the big scene of In the Realm of the Senses. Kore-eda deserves credit for his unflagging effort to try something fresh with every project, but here, it seemed to me, that the film was defeated by an overcute conceit and underdeveloped execution.

The most exciting Asian film I saw at VIFF was Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II. Her first feature, Oxhide, was screened at Vancouver in 2005. (Full disclosure: I was on the jury that awarded that film the D & T prize.) This one seemed to me even better.

To say that this 132-minute film is about a family making dumplings is accurate but misleading. To add that the action consumes only nine shots makes it sound like an arid exercise. In fact, it’s a consistently warm, engaging—I don’t hesitate to say entertaining—film that is also a demonstration of how a simple form, patiently pursued, can yield unpredictable rewards.

In the first Oxhide, we saw the comedy and tensions of Liu’s life with her parents, who run a leatherwork shop. By the time she shot part two, they had already lost their business, but the sequel presupposes that the shop is still going, albeit coming to a critical point. So there’s a quasi-documentary aspect, as the family’s financial strains, discussed cryptically at various points, hover over the mundane process of wonton cookery. Yet although everything looks spontaneous, it was all completely staged—written out in detail, rehearsed over months, reworked in test footage, and eventually played out in “real time.”

And in real space. The first shot, which consumes twenty minutes, shows Liu’s father pummeling a hide in his vise and eventually clearing the table for serious food preparation.

Actually, the film’s subject is that table. On its surface, a meal is prepared; around it, the family gathers; we even see what happens underneath. We watch father and mother chop scallions, mince pork, twist and yank dough, pinch the dumpling wrappers around the filling. We watch the daughter try to match her parents’ dexterity. This is a movie about housework as handiwork, and family routines and frictions.

For minutes on end, we see only hands and arms; Liu’s 2.35 frame often chops off faces. Liu employed a construction-paper mask to create the CinemaScope format within HD video. Why the wide frame? Most filmmakers use it for expansive spectacle, she remarks; but “I wanted to see less.” And the horizontal stretch further emphasizes the table.

As if this weren’t rigorous enough, Liu has filmed the table from a strictly patterned arc of camera positions, dividing the space into 45-degree segments. These unfold in a clockwise sequence around the table. What could seem an arbitrary structural gimmick is justified by the fact that each setup proves ideally suited to each stage of the process. When father and mother team up to start the meal, the angle gives us two centers of interest. And Liu feels free to “spoil” her mathematical structure by varying the height and angle of her camera. Plates, bowls, and an articulated lamp become massive outcroppings in this micro-landscape.

Oxhide II is unpretentiously inventive, quietly virtuosic. Evidently it took a Chinese filmmaker (whose day job is writing TV dramas) to blend domestic life with the rigor of Structural Film. Liu displays the fine-grained resources yielded by several cinema techniques, from framing and staging to lighting and sound. The finished dumplings get constantly rearranged on the cutting board. Each family member has a different technique for pulling off bits of dough, and each gesture yields its own distinctive snap.

I had to think, almost with pity, of all those US indie filmmakers who believe they have to cultivate CGI and slacker acting, to seduce investors and strain for outrageous sex and edgy violence. Liu made this no-budget, low-key masterpiece over years in a single room, and with her parents. That’s a new definition of cool.

Liu promises us another installment. In the meantime, every festival that’s serious about the art of cinema should pledge to show Oxhide II.

Puccini and the Girl.

PS 12 October: Thanks to Matthew Flanagan for correcting an embarrassing typo.

PS 15 October: Thanks to Ben Slater for correcting yet another one!