Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

Dispatch from sunny Vancouver

Ballast.

After six days, plenty to report from the Vancouver International Film Festival. It has been unusually warm and sunny during our first week, but we have diligently spent most of our time in darkened theaters.

Kristin here:

Another country heard from

It’s a rare day when one gets to see a Haitian film. It’s an equally rare day when one gets to see a Jordanian film. On Monday I saw both, and the contrast between them could hardly have been greater.

Eat, for This Is My Body (Mange, ceci est mon corps, 2007), a Haitian/French co-production is Michelange Quay’s first feature. A Haitian-American, Quay received his MFA in directing at New York University.

The film’s opening is extraordinary, with a series of low-altitude helicopter shots beginning over the ocean and then moving rapidly across huge shanty-towns and finally into bleak mountain canyons in the country’s interior. After this passage of flight over bright landscapes, the bulk of the story takes place in and around a quiet, dark, nearly deserted colonial mansion somewhere in the countryside.

I’ve noticed that there seems to be a mini-revival of 1970s-style art cinema conventions. After many years in which art cinema tended to mean intricate psychological studies, a more challenging, formalist avant-garde seems to surface now and then. While watching Eat, for This Is My Body, it occurred to me that it could almost have been called Haiti Song, so strongly did it remind me of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. There enigmatic actions, often dancing, were staged in a colonial house. Eat, for This Is My Body’s action is, if anything, more enigmatic, though in this case the native population is present in the house in the person of a dignified manservant and a group of nine boys brought at intervals into the house, apparently as a treat.

The story is so minimal as to be non-existent. Apart from the nine boys, there are only three characters: an  old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

The Jordanian film, Captain Abu Raed (2007), takes a more familiar approach, centering around a likable, heartwarming protagonist. Raed, an airport janitor, finds an old pilot’s hat, and the children in his working-class neighborhood assume he really is a pilot. He plays along, less to feed his own ego than to inspire their imaginations through false tales of his adventures abroad. Gradually he becomes more involved in the lives of some of his listeners, and the film progresses from the sugar-coated tone of the opening scenes into a darker situation as Raed seeks a way to save the family of a violent neighbor.

Director Amin Matalqa was raised principally in the U.S., but he returned to his native country for this, his first feature. It is also the first feature film to come from Jordan in decades, and it reflects a slow but distinct movement into movie production in some of the Middle-Eastern countries where conservative religious views have long suppressed it. Captain Abu Raed is technically polished and makes considerable use of Amman cityscapes and ancient ruins as backdrops for the action. It’s also definitely a crowd-pleaser, judging by the sold-out audience I saw it with.

Another rarity is Australian director Benjamin Gilmore’s first fiction feature, Son of a Lion (2007), which he filmed entirely in the Peshawar region of Pakistan. That’s an area adjacent to the northwest border of the country with Afghanistan, notorious as a refuge for Taliban fighters and probably Osama bin Laden. The program lists Son of a Lion as an Australian/Pakistan production. I doubt any Pakistani funding went into it, but Gilmour wrote the script with the advice of the local people, and non-professionals play all the characters. The credits also contain quite a few Pakistanis performing tasks behind the camera.

The story seems inspired in part by the “child’s quest” narratives of the Iranian classics of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

Son of a Lion was shot under difficult and dangerous circumstances on digital video (with post-production handled, amazingly enough, by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post facility in New Zealand). The shots of the beautiful desert landscapes are not up to those we are used to from Iranian films, but they manage to suggest the grandeur of the area and to give a fascinating and humanizing insight into a region which the American government and media portray as merely a hotbed of terrorism.

Moroccan films are not quite as rare as these, but they’re certainly not common. As Burned Hearts (Morocco/France, 2007) was being introduced, I realized that the only other Moroccan film I had previously seen was by the same director, Ahmed El Maanouni. That had been Trances, a semi-documentary1982 film about a touring pop-music group. It was shown last year at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, having been the first film restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Founda tion.

Burned Hearts was another film that seemed to transport me back to the 1970s art cinema. A young man returns to his childhood home after being educated as an architect in Paris. His tyrannical uncle is dying, and flashbacks present the painful memories evoked by the familiar sights and sounds of the city, this exploration of the character’s mental paralysis, along with the black-and-white cinematography of the locations, evokes both Duras and Antonioni. But El Maanouni refuses to concentrate solely on the hero’s concerns, bringing in several intriguing characters from the neighborhood and having groups spontaneously break into song and dance in the streets and shops.

Melodramas from Mexico

These films all come from regions seldom represented in international film festivals, but Mexican cinema  has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

The other Mexican film, All Inclusive (2008), deals with another family crisis, but one which takes place over a few days in a luxurious resort on the “Mayan Riviera.” The story is slickly told by director Rodrigo Ortúzar Lynch and beautifully shot by Juan Carlos Bustamante, but I found the story forumulaic. A man who has just been told that he has only a short time to live, goes on vacation with his family, whom he has not informed of his condition. As he struggles with his secret, his wife and three children undergo their own crises. One daughter faces up to the fact that she is a lesbian, the son becomes entangled in an online “affair” with another man’s girlfriend, and the wife, assuming that her husband is being unfaithful, allows a young scuba instructor to seduce her—all this observed by the sardonic goth daughter.

As the tensions grow, a hurricane approaches, and the climactic set of revelations and reconciliations come just as it hits. During the narrative, each of the troubled family members manages to find someone gorgeous willing to bed them and/or hear their tales of woe. The idea that the bearish husband, seeking escape in a local bar, would run across a stunning 23-year-old Cuban woman who would take him into her home, listen at length to him, and finally, of course, teaching him to enjoy life. This gives him the courage to return to his family and tell them the truth. Once the family members have bared their soles, they become a jolly, well-adjusted bunch. It’s an entertaining story with likeable characters and touches of humor—but it’s a bit too much to believe.

Americans in Canada

Apart from Craig Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu, which David will cover, I’ve seen two American indies so far. Momma’s Man (2008) is directed by Azazel Jacobs. It deals with Mikey, a man traveling on business who has problems with his flights and ends up staying with his parents in their New York loft. Finding excuses not to return to his wife and baby in California, he fritters away his time by reverting to his childhood pursuits. The film takes the daring step of being centered on an unsympathetic character who is the point-of-view figure for all but a few scenes. It manages to convey his gradual move from indecision to obsession and eventually a full-blown breakdown in a believable fashion.

Part of the appeal of Momma’s Man comes from the fact that Mikey’s parents are played by Ken Jacobs, the great experimental filmmaker, and his artist wife Flo Jacobs. It is set in their actual New York loft, a maze of odd filmmaking devices, accumulated pop-culture artifacts, and artworks. The two give extraordinary performances, managing to seem wise and caring and at the same time obsessive and eccentric to a degree that might have contributed to Mikey’s breakdown. Although Jacobs cast an actor as Mikey, one has to suspect that the film is at least somewhat autobiographical, and the casting of his parents has created a uniquely convincing portrait of a family.

David and I were delighted to see RR (2007) on the program. It’s the latest feature by American avant-gardist James Benning. Jim is an old friend, having been a graduate student in our department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during our early years there. He has concentrated largely on landscape films, usually consisting of lengthy, static shots. This one consists wholly of distant views of trains in what appear mostly to be western and Midwestern locations. In virtually every case the shot holds until the entire train has moved through the shot or out of sight—or stopped, in a few cases.

As so often happens with structural films, small variations become evident to the alert viewer. A shot of a  car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

RR draws us to enter into perceptual play, often with a distinct touch of humor. Few of Jim’s films have contained the measure of their shot length in their mise-en-scene so decisively. The length and speeds of the trains determine the duration of the shots, and one learns to watch for the number of engines pulling or pushing a train as an indicator of how long the train is likely to be. A few shots show trains moving slowly and decelerating at an almost imperceptible rate, teasing us as to whether they will stop altogether and whether the shot will end if they do. At times a train may move through the shot, only to reveal another on a parallel track. One shot plays a very clever game with us. I won’t reveal what it is, but the shot comes perhaps a third of the way through: an oblique view along a track with bushes prominently in the foreground and a short, arched underpass in the middle distance.

Jim has continued to shoot in 16mm in an increasingly digital age, and he consistently manages to make gorgeous images that look more like 35mm. The last one of RR, involving a vast wind farm, is a stunner.

Captain Abu Raed.

David here:

An unusually good VIFF, with many films to get your eyes open.

Enter the Dragons, with Tigers

As usual, the venerable Dragons and Tigers thread is offering some remarkable new films from Asia. The Good the Bad the Weird lived up to its reputation, not to mention its title, offering frenetic action and comic-book (in the good sense) bravura. Sell Out!, a Malaysian satire of corporate maneuvering and media brainwashing, doesn’t get points for subtlety—the goliath is called the FONY corporation—and sometimes it tries too hard. Still, it’s likeable enough, and the fact that it’s a musical adds a welcome bit of froth. The funniest bit, for me, was the opening parody of an art movie, which does actually get integrated into the main action.

Two late works by long-time Japanese directors offered a study in contrast. Kitano Takeshi’s Achilles and the Tortoise starts out sweet and ends very sour, not to say bitter. In telling the story of a boy whose spontaneous love of drawing is forced into narrow commercial channels, Kitano suggests that art is a racket. Across the decades, schools and galleries push the pliant, nearly comatose young artist to create a signature style. He is told to be original, but also he must harmonize with fashion and tradition. With a grim obstinacy he tries to fulfill what the business demands, and to the end he is still trying.

Achilles is less willful than Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!, and it tells a more coherent tale, but their glum narcissism is still in evidence. The film cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: is the naïve filmmaker corrupted by exposure to international art cinema? Pictorially, there’s some confirmation of this: Kitano seems to have abandoned his early films’ ingenious use offscreen spaces and planimetric compositions. Like his hero, who can’t achieve artistic singularity, Kitano has become a surprisingly academic and anonymous stylist.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

Wakamatsu’s technique is unstressed: No fancy angles, neverending tracking shots, or virtuoso compositions, just a businesslike application of today’s wobbly handheld look. The cunning lies in the film’s structure. After a half-hour montage summarizing the formation of the group, we are carried into the hideouts and watch the punishment grow more feverish and self-destructive under the domination of two leaders who seem parallel to Mao and Madam Mao.

By the end of the second hour, the remains of the army are on the run, struggling through vast snowy landscapes. Soon four survivors straggle into a ski lodge, hold the owner’s wife hostage, and face their final challenge: wave after wave of police assaults. Waiting for the inevitable outcome, the survivors spare time for grim humor: On 28 February one remarks, “I’m glad the all-out war won’t be tomorrow. Then my death anniversary could come only every four years.” And they can pause for an exercise in political discipline. After a lad takes an extra cookie, he criticizes himself. Stern reprimand follows: “That very cookie you ate is an anti-revolutionary symbol.” Unsentimental and unsparing, United Red Army is over three hours long, with not a longueur in sight.

A man parks his car to pick up some cake at a bakery. He has been away from home all night; now he’s rude to the lady behind the counter. Having bought a couple of cakes, he finds that a sinister black car has double-parked and hemmed him in. His efforts to find the owner lead to a spiral of comic and pathetic confrontations with an orphan child, burly Triads armed with whitewash, and a pimp with a distinctly bad haircut.

Creating something of a network narrative, Chung Mong-hong’s Parking in its modest way offers a cross-section of Taiwanese society, from the prostitute brought over from China to a jaunty barber who more or less controls the switch-points of the story. The ending will strike some as dovetailing all the cards a little too smoothly, but I found it satisfying, if only because it lets our haughty hero show unexpected resilience and compassion. This is only Chung’s second feature, but his work bears watching.

For once, it really is rocket science.

If you’ve already figured out the deep connections among Scientology, the aerospace industry, ritual sex magic, New Age spirituality, and the migration of Los Angeles hipsters to San Francisco in the 1950s, Mock Up on Mu won’t come as news. If, like me, you haven’t the faintest idea about the cat’s-cradle ties among these cultural phenomena, Craig Baldwin’s latest collage-essay-epic-lyric-narrative (all terms he applies to it) is the very thing you need. It’s as exuberantly peculiar as his earlier work like Tribulation 99 and Spectres of the Spectrum, flooding us with a relentless voice-over that splits off from and reconnects with the torrent of images grabbed from all manner of movies.

These earlier films had stories of a sort, swollen conspiracies and ominous coincidences that make Baldwin the eccentric cousin to Fritz Lang. But Baldwin says that these stories couldn’t really engage people, couldn’t get them to identify. Mu tells a more personalized tale. L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, has colonized the moon and sends Agent C to earth to arrange for people to be shipped up. Agent C runs afoul of Lockheed Martin, corrupt aerospace executive, and becomes attached to Jack Parsons, an early rocketeer who in the 1950s assumed the secret identity of Richard Carlson, so-so Hollywood actor. Meanwhile, Aleister Crowley rules a secret society at the center of the earth….

Or maybe not.

Actually, I won’t swear to much of what I just said. Baldwin’s phantasmagoria tests my memory, as well as plausibility. The story line is swallowed up by what he calls footnotes—swarming digressions, tangents, and flashbacks which are conjured up in imagery that shoots off in a dozen different directions. A few frames from a kiddie science movie or a grade-Z space opera, juxtaposed to Parsons’ rapid-fire account of the history of rocket testing, whiz by almost subliminally.

In any case, there are characters and a more or less linear story. But Baldwin is Baldwin, so things can’t be so simple. He has for the first time staged and shot footage of actors, and their scenes form a sort of string that you can follow. But just as crystals grow in fantastic array along a string, alien footage exfoliates out from the staged scenes. Baldwin aims, he says, at “a dialectical density.”

The result is a narrative experiment I’ve never seen before. With a simple cut, our characters are replaced by figures from other films, who become, in some spectral fashion, both alien inserts and our characters.

Confused? Here’s an example. Agent C (who will turn out to be Marjorie Cameron, muse of many West Coast artists) is riding with rocket scientist Jack Parsons. A series of shots shows them in the car’s front seat.

As the scene goes on, one character gets replaced by another.

Eventually both of our originals have been replaced.

The stand-ins can even change position as the dialogue continues uninterrupted (but always mis-synchronized).

The cuts make the inserted characters surrogates or avatars for our people, but they retain wisps of their original, enigmatic existence. They also remind us that situations like driving in a car are genre stereotypes, schemas so common that individual instances can serve as place-holders for one another. Yet the shots always return to the original actors, anchoring the associations and keeping at least one plane of the narrative moving forward.

These phantasmagoric shifts make the identity transformations in I’m Not There look labored. In Mock Up on Mu Baldwin may have found a new method of cinematic storytelling. Don’t expect Hollywood to pick it up soon.

Pulling half away

How do you tell your audience what it needs to know to understand what it’s seeing, and what it will see? A film can handle exposition (aka backstory) in several ways. Most films favor concentrated and preliminary exposition: Most information is given in one spot and quite early on. This is when you get the opening dialogue when characters say to one another: “Look, you’re my sister. You can tell me.” (Ohh…They’re sisters.) Concentrated, preliminary exposition is usually clunky, but it can be done with finesse, as in the opening soliloquy of Jerry Maguire.

The major alternative is distributed exposition, where information about the backstory is spread out, evenly or unevenly, across the film. This is common in mystery films (as when, under pressure, characters start to confess their relation to the murder victim) and in “puzzle films” like Memento, where we only gradually understand the relations among the characters. Delayed and distributed exposition in straight dramas is common in European art cinema, but it’s rare in the US, although independent films like Claire Dolan and Man Push Cart have made good use of the technique. Kristin already mentioned a similar strategy at work in Eat, for This Is My Body.

Lance Hammer’s Ballast comes garlanded with praise from festivals and major news outlets like the New York Times. For once the advance word is justified. I thought that Ballast was an exceptional intimate drama, focused almost entirely on three people and their layered relationships in a country town in the Mississippi Delta.

At this point I should mention how the three principals are connected, but part of the daring of Hammer’s film is to postpone, for almost an hour, telling you such things. He says he wanted a film that is, like the Delta, “spacious and quiet and slow.” Here the very issue of what we need to know is put into question. By blocking our knowledge of characters’ relationships, Hammer forces us to confront moments of action in a pure state. Each instant, each shot even, gains an integrity and gravity it wouldn’t have if we knew the full dramatic context.

Take the opening. After a brief, wordless prologue showing a boy in a field of crows, we’re in a vehicle pulling up at a bungalow.

The indistinct figure of a man goes to the door. Inside, a brief shot shows a black man’s face in silhouette.

Soon, the first man, who is white and weatherbeaten, is seen at the door, expressing concern for the man inside.

The white man enters, wrinkles his nose at a smell, and proceeds to another room, where a figure, turned from us, lies on a bed.

The black man continues to sit impassively before his TV, though now we can see his face more clearly.

Who are these men? What connects them? Who has died? An ordinary film would tease us with these questions but answer them fairly soon (say, in the next three or four scenes). Here, we will have to wait a considerable time to find out the answers. In the meantime, what we have registered in place of an action arc is the atmosphere of shock, sorrow, grieving, and lowering skies. And almost immediately a rather dramatic event will occur, nearly offscreen, and its causes will remain equally opaque for quite some time.

Ballast’s delay in spelling out its story premises is sustained by two unusually quiet main characters. Lawrence, the man sitting in the darkness, leads a solitary life and speaks reluctantly and briefly. Likewise, the boy James is often silent or alone. These two don’t soliloquize, and they live one day at a time. We must simply observe their behavior, try reading their minds, and more generally absorb the emotional tenor of their lives.

The sparseness of the exposition also puts us on the alert for any scrap of information that will fill in the blanks. For instance, references to “the store” flash out as clues to possible connections among the characters. Hammer’s strategy demands that the audience exercise a degree of patient concentration that most films never ask for.

For roughly the first half of the film, then, Hammer’s narrational technique creatively impedes our full understanding of the basic givens of the story. Once the relationships have coalesced (though there are still some revelations to come), the dialogue becomes more explicit and, some would say, the drama more traditional. But the visual narration continues to mute and elide dramatic moments. At some points pieces of action are rendered opaque by the bobbing, jump-cut camerawork. Most memorably, a clumsy embrace is hidden by a “wrong” camera setup, all the better to make us wonder about the impulses behind the gesture. Hammer matches his oblique plotting with an oblique visual style.

Hammer has cited Bresson as an inspiration, and in conversation he also mentioned late Godard, who has become willing to avoid exposition for nearly an entire film. Unlike Godard, who seems to revel in the pure artifice of withholding information, Hammer appeals to realism: The gradual piecing together of the narrative, he remarked to me, is like our coming to know people in life, bit by bit.

Correspondingly, by the end of Ballast we come to feel more empathy for Hammer’s characters than for Godard’s, and possibly even for most of Bresson’s enigmatic souls. But the empathy doesn’t come cheap, and it isn’t wallowed in. The climax is brushed past in one sideswiping shot; blink and you’ll miss it. In another interview, Hammer speaks of “putting something out and pulling half away.” By leaving us to fill in that half, Hammer exhibits his respect for his characters, and for his audience.

Mock Up on Mu

P. S. For dispatches from 2006 and 2007 editions of the VIFF, type Vancouver into our search box.

More light from the East

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke, China, 2007).

DB’s last communiqué from the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival:

I’m so taken with José Luis Guerin’s En la ciudad de Sylvia (Spain/ France) that I’ll be devoting a separate blog entry to it soon. At Vancouver it was projected with his Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia, a remarkable sketchpad for and rumination on the feature. Rubbed together, the two films throw off sparks. En la ciudad is in color and very tightly constructed, Unas fotos consists of hundreds of black-and-white stills linked by associations and intertitles, with no sound accompaniment. Guerin, an admirer of Murnau, says that as a young man he watched old films in “a sacred silence” and he wanted to try something similar.

Unas fotos may not be factual—call it a lyrical documentary—but it illuminates En la ciudad in striking ways and is intriguing in its own right. Structured as a quest for a woman the narrator met 22 years ago, the film moves across several cities and invokes as its patrons Dante and Petrarch, each of whom yearned for an unattainable woman. But this isn’t exactly a photo-film à la Marker’s La jetée; it uses dissolves, superimpositions, and staggered phases of action to suggest movement. The subjects? Dozens of women photographed in streets and trams. Some will find a creepy edge to the movie, but it didn’t strike me as the obsessions of a stalker. Guerin becomes sort of a paparazzo for non-celebs, capturing the many looks of ordinary women.

Watch this space for more on the many looks of Sylvia. For now, more Asian highlights from Vancouver.

Fujian Blue.

Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai have reunited for The Mad Detective (Hong Kong), which is as off-balance as you’d expect from its premise. Evidently spun off those TV series that feature telepathic profilers, the film stars Lau Ching-wan as a detective who solves cases by intuiting crooks’ “inner personalities.” We’re introduced to him crawling into a suitcase and asking his partner to throw it downstairs. After a few bumpy descents, he flops out and names the man who packed up a girl’s body the same way. Soon Lau is mentally reenacting a convenience-store robbery, and To/Wai cut together various versions of it as he plays with the possibilities.

Years after Lau leaves the force, his partner brings him back as a consultant to another case. By now, though, our mentalist has gone mental. The filmmakers get comic mileage, and some genuine poignancy, out of intercutting his hallucinations with what’s really happening. Lau envisions multiple personalities within the man they’re hunting, and as he traces out clues each personality flares up. To and Wai carry their dotty premise to a vigorous climax that multiplies the mirror confusions of both Lady from Shanghai and The Longest Nite. The brilliant sound designer Martin Chappell is back on the Milkyway team, making the effects and music magnify Lau’s heroic disintegration.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Secret Sunshine earns its 130-minute length, because Lee needs time to do several things. He traces the assimilation of a widow and her little boy into a rural town. Then he must follow the remorseless playing out of a harrowing crime. He makes plausible her succumbing to fundamentalist Christianity and her growing conviction that she needs to forgive the criminal. And there are more changes to come.

For me the most unforgettable moment was the heroine’s appalled confrontation, in a prison visiting room, with the man who wronged her. His unexpected reaction dramatizes how religious faith can cultivate both emotional security and an almost invincible smugness. Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress award at Venice for her nuanced performance, and Song Kang-ho, best known for The Host and Memories of Murder, lightens the somber affair playing a man of indomitable cheerfulness and compassion.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

Off to China for Fujian Blue by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). The setting is the southeastern coast, a jumping-off point for illegal immigration. The plotline has two lightly connected strands. In one, a boys’ gang tries to blackmail straying wives by photographing them with boyfriends, going so far as to sneak in homes and catch the couples sleeping together. The other plot strand presents Dragon, a boy who’s trying to sneak out of China and make money overseas. The whole affair is reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Boys from Fengkuei, and in Dragon’s story we can spot overtones of Hou’s distant, dedramatized imagery. Yet Weng adds original touches as well, including an almost subliminal ghost of London across the blue skies of the China straits.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

In the second episode . . . But why give away any more? In this relaxed, peculiar little film Beckett meets the Buñuel of The Milky Way and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. As the enigmatic men without pasts or even psychologies wound their way through the long shots, Zheng’s quietly comic incongruities won me over long before the last dog had barked and the last ball had bounced.

Jia Zhang-ke is known principally for fiction films like Platform, The World, and Still Life, but from the start of his career he has shown himself a gifted documentarist as well. His In Public (2001) is a subtle experiment in social observation, and Dong (2006) made an enlightening companion piece to Still Life. Useless is more conceptual and loosely structured than Dong. Omitting voice-overs, Useless offers a free fantasia on the theme of China as apparel-house to the world.

The first section of the film presents images of workers in Guangdong factories as they cut, sew, and package garments. Jia’s camera refuses the bumpiness of handheld coverage; it opts for glissando tracking shots along and around endless rows of people bent over machines. (Now that fiction films try to look more like documentaries, one way to innovate in documentaries may involve making them look as polished as fiction films.) Jia also gives us glimpses of workers breaking for lunch and visiting the infirmary for treatment.

In a second section, Useless follows the success of a fashion house called Exception, run by Ma Ke. Her new clothing line Inutile (Useless) consist of handmade coats and pants that are stiff and heavy, almost armor-like, and that flaunt their ties to work and nature. (Some outfits are buried for a while to season.) Ending this part with Ma’s Paris show, in which the models’ faces are daubed with blackface, Jia moves back to China and the industrial wasteland of Fenyang Shaoxi. There he concentrates on home-based spinning and sewing. Neighborhood tailors patch up people’s garments while the locals descend into the coalmines. A former tailor tells us that he gave up his work because large-scale clothes production rendered him useless.

Jia’s juxtaposition of three layers of the Chinese clothes business evokes major aspects of the country’s industry: mass production, efforts toward upmarket branding, and more traditional artisanal work. Without being didactic, he uses associational form to suggest critical contrasts. The miners’ sooty faces recall the Parisian models’ makeup, and their stiff workclothes hanging on a washline evoke the artificially distressed Inutile look. What, the film asks, is useless? Jia shows industrial China’s effort to move ahead on many fronts, while also forcefully reminding us of what is left behind.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Mark Peranson, and all their colleagues for a wonderful festival. They’re so relaxed and amiable, they make it look easy to mount 16 days crammed with movies. Be sure to check on CinemaScope, the vigorous and unpredictable magazine that makes its home in Vancouver. It gives you many gems online, but it’s well worth subscribing to.

Alan Franey, Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival; PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager; and Mark Peranson, Program Associate and Editor of Cinema Scope.

Vancouver visions

Drizzle every day can’t dampen audiences’ enthusiasm.

DB again:

More dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

“Be pleased, then, you living one, in your delightfully warmed bed, before Lethe’s ice-cold wave will lick your escaping foot.” As a tram destination, Lethe makes a brief appearance in the Swedish film You, the Living, Roy Andersson’s latest comedy of trivial miseries. The line from Goethe is apt. After ninety minutes of drab apartments and Balthus-like figures, all bathed in sickly greenish light, you’re ready to stay in bed forever.

As in Songs from the Second Floor, Andersson gives us a loose network narrative, with barely characterized figures threading their way through urban locales. Long-shot, single-take scenes turn clinics and dining rooms into monumentally desolate spaces. Humans, either bulbous or emaciated, trudge through torrential rain and peer out from distant windows. The bodies may be distorted and careworn, but the spaces are even more so. We get a sort of dystopian Tati, in which gags, near-gags, and anti-gags are swallowed up in the cavities we call home and workplace. A carpet store stretches off into the distance, and a cloakroom seems like a basketball court.

In You, the Living, Andersson’s characters recount their dreams, and these open onto areas only a step beyond our world in their lumpish crowds and eerie vacancy. Judges at a trial are served beer as they condemn the accused. Spectators at an electrocution snack on popcorn from supersized buckets. How can I not like a filmmaker so committed to moving his actors around diagonal spaces, even if the frame is either sparse or uniformly packed, and though he does treat his people like sacks of coal? Don’t look for hope here, only a sardonic eye attracted by banality and pointlessness, images made all the bleaker by an occasional song.

I’m drawn to directors who create a powerful visual and auditory world more or less out of phase with reality as we usually see it (in life and in movies). Andersson is one such director; Jiang Wen is another, whose audacious The Sun Also Rises is one of my favorites of the festival so far. Not doing so well with Mainland Chinese audiences, according to the International Herald Tribune, it hasn’t warmed up a lot of Western critics either. Amazingly, it was declined for competition at Cannes.

It seems impossible to discuss The Sun Also Rises without using the word “magic,” as in magic realism, but I saw it as more of a fairy tale or fable. Set in the Cultural Revolution, it tells two stories in the first two sections. A young boy’s mother goes a little mad on a labor farm; in another village, a teacher is compromised by the passionate love of a nurse and an accusation of sexual misconduct. The two stories intersect in a third section, which leads to a jubilant, if disconcerting, final stretch.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

The exuberance of the characters and the style contrasts with the usual presentation of this cruel era of PRC history. Jiang finds real pleasure in Cultural Revolution kitsch, and he links a snapshot of the missing father to an iconic image from The Red Detachment of Women. It’s another knot joining the two plot strands; in the second section, villagers watch a screening of that film. Jiang makes the event a real festivity, with couples courting, the teacher humming along with the tunes, and an old lady feeding fish in a pond. Jiang dares to suggest that the force-fed popular culture of Maoism, so scoffed at now, gave genuine enjoyment

The fairy-tale atmosphere is conjured up by little mysteries, such as a talking bird and the possibility of taking dictation on an abacus, and bigger ones about fatherhood, a stone hut in the forest, and a shadowy figure named Alyosha, whose identity is more or less revealed in the film’s final long sequence. Variety‘s Derek Elley found The Sun Also Rises both rushed and dawdling, but you could say that about 8 ½ too. Like Fellini’s film, Jiang’s shows a filmmaker at the top of his powers inviting us to savor the exhilarating attractions of imagination.

Another world, another vision. The camera frames a rope descending into black water and tilts slowly, really slowly, up to reveal the ship’s prow and the deck, swathed in darkness. Two silhouettes are visible, and one says, “Don’t follow me too soon.” Soon we’re following the transfer of a small suitcase, the disembarking of passengers making their way to a train. This nearly thirteen-minute shot (!) gives way to another long take, in which we see, in the distance, a murder on the quay.

Béla Tarr has called The Man from London a film noir, and he explained that to me by saying, “Not an American film noir. They were done by bad directors. More like the original French film noirs.” Indeed, the opening shot, with its mists and murky waterfront, suggests Quai des brumes. But here the plot action is slight, presented at a distance, and opaque in its motives; 10 % story, we might say, but 90 % atmosphere. The camera coasts across the waterfront town with the same grave deliberation we see in Damnation, Sátántangó, and Werckmeister Harmonies, swallowing up the Simenon situation in Tarr’s fluid way of seeing, a scanning of ever-shifting surfaces and vistas.

With fewer than thirty shots across about 133 minutes, The Man from London is another exercise in long-take virtuosity, but I thought I noticed some fresh departures. For one thing, there are few characters and relatively few locales, and situations are brought out with unusual explicitness (for Tarr). Instead, it seemed to me that Tarr was exploring new possibilities in one of his pet techniques, the over-the-shoulder long shot I mentioned in an earlier entry.

The opening shot, at first an apparently objective survey of the moored ship, turns out to be a view from the tower manned by Maloin. In shooting the wharf, the camera is forever oscillating, within a single shot, between what we can see outside, at a distance, from a high angle, and glimpses of Maloin at his post, his head or shoulder sliding into the foreground. Imagine Rear Window without the reverse shots of Jimmy Stewart watching.

In earlier films, Tarr tended to be quite clear when his foreground character was noticing something in the distance; his chief interest lay in suppressing the character’s reaction. What we get here can be seen as a refinement of the opening shot of Damnation, with its awesome landscape gradually reframed by Karrer looking out his window, or of passages of the doctor at his window in Sótántangó. Several of the tower scenes in The Man from London, are elaborations of that image scheme, but with more ambiguity. The camera, slipping from long-shot background and close-up foreground, coasts along without telling us whether Maloin has seen exactly what we’ve seen. The result is a suspenseful uncertainty not only about what’s happening in the noir plot but also about what Maloin knows.

There are many other points of interest in the new film, and after one viewing I can’t claim to have a grip on them. But I do think critics have overlooked its sheer visual beauty and Tarr’s efforts to turn his style toward a fluid pictorial suspense.

Altogether less flamboyant than any of these was Suo Masayuki’s I Just Didn’t Do It (Japan), which I’d been looking forward to since my February entry. It’s definitely a change of pace for a director known for comedies that satirize youth culture and middle-aged boredom. A young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl on a crowded traincar. The police advise him to confess and pay a fine, but he insists on his innocence. This decision drops him into a judicial mill that grinds slow and altogether too fine.

The script carpentry seems to me excellent. The presentation of each phase of the boy’s case could have been dry, but Suo makes each step hinge on a detail of fact or inference, so small questions keep popping up—including questions about whether the boy really might have done it. The finale, which recalls Kurosawa’s Ikiru in its methodical summing up of everything we have seen, becomes grueling, but in a salutary way. In Japan, the film is a trailblazing critique of the criminal justice system, where most people arrested confess in order to avoid the almost inevitable guilty verdict in a trial. Eliminating a jury, barring defense counsel’s discovery of prosecution evidence, and capriciously replacing one judge by another midway through a case, the system encourages cynical submission.

Suo avoids stylistic pyrotechnics. He plays down his signature mugshot framings (the publicity still above is an exception) and has recourse to handheld camerawork simply to distinguish the train scenes from the rest of the film. Still, his shooting displays a quiet agility. The high point is probably the testimony of the schoolgirl, her identity protected by screens set up around her. Suo finds a remarkable variety of camera setups here, each well-judged to impart a particular piece of information. (In its resourceful changes of viewpoint, the sequence reminded me of Mizoguchi’s courtroom scenes in Taki no Shiraito and Victory of Women.) The title suggests a strident social-problem film, but Suo’s calm plainness of handling yields a quality rare in the genre: tact.

Many more films to report on, including Johnnie To’s latest, but I must rush off to—what else?—another movie. I’ll try for a wrapup on Thursday, while I’m on that highway in the sky.

The critics line up: Bérénice Reynaud, Shelly Kraicer, Chuck Stephens, and Tony Rayns.

Back in Vancouver

DB again:

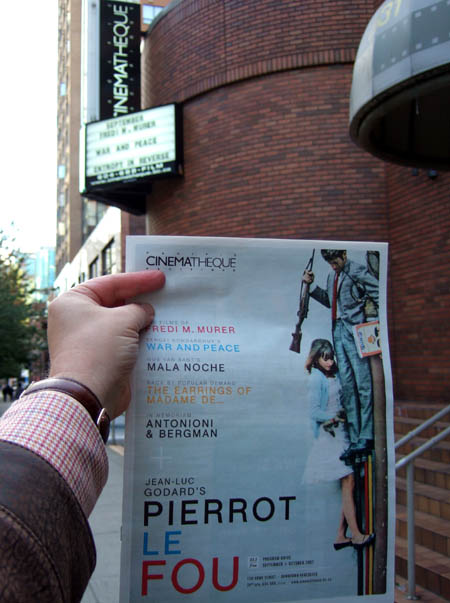

I sang the praises of the Vancouver International Film Festival in my first venture into blogging a year ago, so it’s a pleasure to report that this year’s event is no less captivating. Too many movies to take in, natch, so I’ll concentrate on two of the fest’s great strengths, documentaries and Asian films (programmed this year by both Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer). Top and bottom of today’s entry: glimpses of the two venues where I spend the most time: the Empire Granville 7 multiplex and the Pacific Cinémathèque a couple of blocks away, the latter offering ambitious programming to gladden the heart of any cinephile.

Two docus

10 + 4 (Iran) provides vignettes of Mania Akbari’s struggle to live with cancer therapy. The fact that she’s also the filmmaker, and that she starts, at Kiarostami’s suggestion, from the visual premise of 10, gives the film extra layers of interest. In fewer than seventy shots, most from within moving vehicles, the film presents a series of dialogues, usually between only two people. Since most major action takes place elsewhere, we watch and listen for signs of characters’ pasts, their relationships, and their states of mind.

We can trace Akbari’s development from cheery pride, going to parties despite her chemotherapy (“Every morning I thank God for make-up”), to anguish as the pain mounts and the treatments intensify. No viewer will forget the scene on a cablecar when she and Behnaz, from 10, reveal their different responses to their illness, and offscreen, examine each others’ mastectomies. In a final scene, Akbari, her hair now regrown, is confronted by another woman who warns her of using cancer as a weapon. The final words, heard under the credits—”I am using it, and I can’t give up the joy of this game”—reveal a psychological insight we rarely find in discussions of the social implications of illness.

Oatmeal-video visuals shot handheld and often out of focus, talking heads, dicey sound, overbusy editing—never mind. My Kid Could Paint That shows that we’ll forgive all sorts of technical faults if the subject, story, and ideas are gripping.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

It’s partly because, he shows, experts are pretty evasive when it comes to explaining how to tell good abstract painting from bad. Can’t you tell just by looking, as we can when we appreciate the figurative work of old and new masters? Turns out it’s not so easy. Critic Michael Kimmelman suggests, somewhat vaguely, that even abstract art is about a “story”—if not in the picture, behind the picture. Marla, of course provides a great story, but the question of how to judge her oeuvre remains.

We might insist that an artwork’s goodness is intrinsic, regardless of the circumstances of its making. If we learned on good evidence an eighty-year old woman had composed The Marriage of Figaro, surely it wouldn’t lose its sublimity. But philosophers Arthur Danto and Denis Dutton have suggested that our information about how an artwork came to be is usually relevant to interpreting and judging it. Sure enough, collectors rhapsodized about the work when they thought Marla had done it, but they cooled after a 60 Minutes story suggested that the father had coached her, and perhaps even finished the pieces himself.

That raises another issue, encapsulated by a Binghamton journalist. She explains that if a story is to run long in the media, it has to be given steep ups and downs. Hyped at the start, Marla’s paintings are suddenly called con jobs, and even Bar-Lev starts to get doubtful. How the family tries to regain their credibility, and how Bar-Lev exposes his own hesitations and complicities, makes for a fascinating film.

My Kid Could Paint That touches on other matters, such as the world’s love of a prodigy, the money that drives the gallery scene, and the issue of how much craft, such as skill in drawing, we now demand of our artists. What shines through the intellectual issues is a childhood joy in picture-making. As portrayed here, Marla remains a kid, and she reminds us of the pleasure in gooping up a surface with our fingers. Sony Pictures Classics made a wise move in acquiring this engrossing movie.

Turning Japanese

I try mostly to blog about films I like, passing over the others in silence. Hammer jobs are fun to write and to read, and I confess to having indulged in a couple when I felt that historical or stylistic analysis could cast light on current films that were being overpraised for originality. By and large, though, I prefer what Cahiers du cinéma called the criticism of enthusiasm. Everyone should write about the films she admires, and let history sort them out.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

Kitano is such an important filmmaker that you can’t ignore even something as offhand as this, but we have to hope for more.

Ten Nights of Dreams, a portmanteau feature based on stories by Soseki Natsume, is as uneven as these affairs usually are. The first chapter, a lovely episode by Jissoji Akio, is eerie in a subdued way, with some quietly canted compositions and some cutting reminiscent of the great Page of Madness. I also enjoyed Ichikawa Kon’s entry, a sober monochrome exercise. Most of the others, however, rely on turbocharged CGI and frantic grotesquerie—all justified by the indulgent premise that dreams are really, really weird.

Yamashita Nobohiro’s Matsugane Potshot Affair (2006), however, bowled right down my center lane. A crooked couple comes to a small town and their search for stolen bullion becomes one thread in a tangle of dysfunctional families and grubby sex. My last sentence does the film an injustice, though, because the laconic narration fills in the circumstances and backstory at such a leisurely pace that all your attention is on the grim comic byplay and furtive eroticism of the townfolk. Any movie that starts with a little boy feeling up what appears to be a woman’s corpse on a frozen lake signals its tone pretty straightforwardly.

As in Linda Linda Linda, the only other Yamashita I’ve seen (and mentioned here), the staging and shooting are quietly commanding. The shots average about 23 seconds, but they seem longer because the camera almost never moves. Lovely long takes with layers of depth and pockets of action captured in windows and paper doorways recall the great Japanese tradition of all-over composition. Yamashita provides several shots that could be filed in my gallery of funny framings. When you film this way, you have to know exactly where to put the camera, and several scenes—notably a confrontation among the thieves and the twin brothers—quicken areas of the frame we never normally notice. Movies like this remind you of the pleasure of having time to see everything.

I haven’t yet mentioned the film I enjoyed most, Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises, and today I’m also seeing the new Suo (I Just Didn’t Do It) and some other enticing items. So I turn Chinese, and Japanese again, in my next entry.

For more blogs anchored to the festival offerings, go here.