Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

Attachment anxieties at the Vancouver International Film Festival

DB and KT, front row center, at the screening of The Lighthouse. Photo by Shelly “Sales Agent Cinema” Kraicer.

DB here:

Storytelling cinema depends on characters, and our relations to them. At the level of individual scenes, we can be more or less restricted to what they experience; we can know as much as they do, or more, or less. Across a film, the filmmaker can attach us consistently to one or two characters, or instead roam freely among many viewpoints. And within a scene, the filmmaker’s choice of camera placement can put us “with” one character or another.

In other words, narrative cinema 101. But it’s worth remembering that these are forced choices. As a filmmaker, you can have restricted or unrestricted access to characters, but at every moment you have to choose one or the other. How objective or subjective will you make your presentation? Will you limit your camera setups or go for ubiquity–that tendency to give us shots divorced from the immediate situation? Examples are a drone-delivered image above a city, or that sudden high or low angle that calls our attention to a detail the characters may have missed.

Three films at the Vancouver Film Festival presented a nice menu of attachment options–ways in which we can be tied to our protagonist. All are well worth your attention, so without getting too much into spoilers, I’ll use them as an occasion to study how these forced choices are handled creatively.

The party’s over

Take as a midrange example The Realm (El Reino, 2018), a Spanish political thriller directed by Rodrigo Sorogoyen. Manuel López Vidal is a brisk, no-nonsense functionary enjoying the good life thanks to the corruption of his party. He and his colleagues, the Amadeus Group, meet regularly over expensive meals to plan their schemes of influence-peddling and money laundering. They tease their fastidious accountant about his meticulous ledgers, but those records will become important to Manuel when one colleague leaks incriminating audio tapes of Manuel’s dealmaking. There’s an orgy of document shredding, damage control among the party’s top brass, and the growing likelihood that Manuel will go to jail.

The screenplay restricts nearly all the action to Manuel. This method is established at the start, when a long tracking shot follows him from the beach as he strides into an Amadeus lunch. Thereafter, we’re with him as he learns of the danger he’s in and mounts one tactic after another to save himself. At a couple of moments the camera lingers on his colleagues’ reactions after he’s left the scene, but on the whole we’re firmly attached to him. Some virtuoso long takes, including a ten-minute shot that follows Manuel’s frantic search for the ledgers, virtually fetishize our adhesion to the protagonist.

By and large, the presentation doesn’t delve into his mind. The throbbing techno score conveys his growing panic as he strides from one confrontation to another, but we get no voice-overs, or flashbacks, or mental imagery. And we don’t see Manuel confide his plans to others (although he seems to have told his wife some of them offscreen). This degree of objectivity allows more suspense, as his schemes to save himself unfold in the moment. We must figure out why he’s bracing one colleague, or bursting into a friend’s home in the course of a teenage party. His manic resourcefulness is all the more impressive when he keeps dodging new problems, often revising his plan on the fly.

It’s no easy feat to maintain tension across two hours, especially when we’re asked to invest our sympathy in a corrupt politician, but The Realm manages it. It’s achieved partly through the trim, crisp performance of Antonio de la Torre but also through plot and style: the refusal of omniscient narration (say, showing us the police or party officials tracking him) and a mild degree of camera ubiquity that accentuates the character’s plight, whether in a meeting or all alone.

The Realm is a good example of how manipulating character attachment can strongly engage the audience. We know just enough to understand Manuel’s crisis, but without access to his mind, each scene can yield a surprise when he comes up with a new survival stratagem.

A lot from a little

I hadn’t really considered the Dardennes brothers “minimalist” filmmakers, but seeing Young Ahmed brought home to me how strictly they’ve limited their cinematic palette. Given their emphasis on actors and faces, you might think they rely on the sort of “intensified continuity” on display in modern film and television. Yet they’re far more purist than that, and they take objective presentation further than does Sorogoyen.

They seldom use long shots, let alone establishing shots: a scene starts in medias res with character action, shot from quite close. Filming in handheld long takes, they avoid shot/reverse-shot cutting, either panning between participants in a dialogue or simply framing them in tight two-shots.

The Dardennes minimize camera ubiquity. Not for them the picturesque, distant shots that The Realm sometimes provides. In a car carrying two passengers, the camera isn’t lashed to the hood or filming alongside; it’s in the back seat.

True, cutting yields some ubiquity. When Ahmed’s teacher pursues him through a classroom, she runs ahead of us but then, in the next shot, she catches up with him as he’s about to leave the building.

Like most cuts, it’s an instantaneous change of position that a real observer couldn’t execute. Still, this frame-edge cut creates simple continuity, driven by dramatic necessity and barely noticeable. The cut is softened by a staging that neatly settles into a standard over-the-shoulder setup.

Apparently uninterested in pictorial composition, these filmmakers simply center their subjects in undistinguished framings. No shot becomes strikingly lit or framed. There’s no nondiegetic music, and the soundtrack is subdued; of all modern filmmakers, they benefit least from surround channels.

As in The Realm, the Dardennes’ minimalist approach works well in tying us to the protagonist, while also denying us direct access to his mind. Ahmed, an adolescent in Liège, has given up video games for fundamentalist Islam. Convinced by his imam that his classroom teacher has become an apostate, he decides to take action against her.

His plans emerge wholly through his actions. Without benefits of voice-over, subjective sequences, or flashbacks, we must infer how he will respond to the demands of the Qu’ran as he has been taught to understand it.

The Dardennes’ objectivity doesn’t make the plot hard to follow. A dozen minutes into the film, the premises are clear, the main characters (Ahmed’s mother, his imam, his teacher) are delineated, and Ahmed’s motivation is established. At the half-hour point, his mission is launched. Apart from the ellipsis I mentioned, everything that follows stems from the dramatic premises. And however horrifying Amed’s plans may be, the wistful, pursed-mouth young actor Idir Ben Addi is mesmerically angelic. His glasses make him look adorable.

The style also keeps everything clear. The texture is close to that of documentary filmmaking, but of course the Dardennes’ films are scripted and staged. There’s a high degree of artifice in their apparently artless method. As in the more flamboyant Birdman, their long takes catch every reaction and gesture with great precision.

We always see what we need to see at just the right moment. When something is suppressed–here, the result of a violent knife attack–it’s not an accident (as if the camera were in the wrong spot) but rather the result of our attachment to Ahmed and a clever narrative ellipsis. We could have had a cut like the one in the school, but we remain with Ahmed, and in fact know a bit less than he does about the result of the violence.

All of which is not to deny the originality of Young Ahmed. All the Dardennes films seem modest, but they are, within their limits, quite ambitious in using dramatic psychology to probe social problems. Throughout, I think, we are asked to reflect on how firmly Ahmed believes in his version of Islam. Is it a transitory teen obsession or is he on his way to becoming a dogmatic martyr? We watch his behavior, his encounters with farm life and a young girl, for any signs that his lonely, taciturn demeanor will crack. In other words, this is a suspense film–one based less on the threat of violence (which is there, to be sure) than on how a boy who hasn’t fully formed his character will define himself.

Not such light housekeeping

Both The Realm and Young Ahmed are, to varying degrees, objective in their presentation. We must judge characters by what they do and say. Something very different is going on in Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse. It too adheres largely to one character, but a battery of cinematic techniques, including camera ubiquity, works to plunge us into the man’s mind.

Although the film is a two-hander, it doesn’t balance viewpoints. Thomas Wake, an experienced lighthouse supervisor, arrives at his post with the novice Ephraim Winslow. Almost immediately we are attached to Winslow, who’s assigned grimy menial duties while Wake tends the beacon. Wake tells Winslow that his previous assistant went mad from the weeks of isolation, and very quickly Winslow struggles against the bleak, craggy island they’re on.

We’re prepared for an assault on your senses by the opening, when a ship roars out of the fog toward us. Thereafter, Wake subjects Winslow to a punishing routine of cleaning the cistern, heaving coal into the boiler, and scrubbing floors, while nightly meals with the nattering old salt are just as hard to bear. Winslow’s misery is rendered in vivid, expressionist terms. The deafening fog horns, thunderclaps, and boiler blasts are reinforced by stark, ominous black-and-white imagery. (The film was shot on 35mm film.) Winslow seems trapped in a world of raging elements and gigantic machines.

Eggers builds our affinity with Winslow through classic techniques. He watches Wake at the beacon from a distance; we get optical point-of-view shots of discoveries (real? imagined?) that start to unhinge him.

All the drudgery and pain, punctuated by Wake’s continual harangues and farts, lead Winslow into fantasies and hallucinations. His deterioration is rendered in shock cuts and distended compositions reminiscent of Welles’ Mr. Arkadin or German’s Hard to Be a God. Some will compare the film’s over-the-top climax to that of Aronofsky’s Mother!, but The Lighthouse, with its rapid montage and Gothic chiaroscuro, harks back to silent cinema. The fact that it’s shot in the 1:1.17 ratio favored by early sound film gives it an archaic feel as well. The dialogue, a late title informs us, is drawn from nineteenth-century sources, including Melville and Sarah Orne Jewett.

The Lighthouse has a cadence typical of modern horror films, but Kristin points out that it’s an expressionistic Kammerspiel too–a subjectively tinted drama setting very few characters in a constrained locale. Eggers shows that you can renew a genre’s appeals by reviving imagery from a classic period of film history. When you do it, you’ll still have to make fundamental choices about viewpoint and camera placement. They come with the territory.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis and Shelly Kraicer for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on classic Kammerspiel films go here and here.

The Lighthouse (2019).

Vancouver 2018: A final few films

Kristin here:

As I write, David and I have been at home after the Vancouver International Film Festival for one week. Between Venice and Vancouver, I saw about 40 films, some of them likely awards competitors for the year and some more modest works that need to be sought out at festivals and big-city art-houses. (Today, in a cyclical gesture, we’re going back to the very first film we saw at Venice, First Man, this time in IMAX.)

During any festival there’s never time enough to write up comments on all the films we see. This is our last report on the 2018 Vancouver event, this time dealing with Middle Eastern films and one from South America.

3 Faces (Jafar Panahi, 2018)

3 Faces begins startlingly, with a vertical cell-phone image of a girl in a rocky area, dictating a suicide note as she walks. She identifies herself as Marziyah, a peasant girl who aspires to be study acting but whose conservative family (along with their entire village) have blocked her from doing so. She has written repeatedly to a famous TV actress, Behnaz Jafari (played by herself) for help, but receiving no response, she has decided to kill herself. The recording ends as the girl apparently hangs herself and the camera falls.

The image opens to fullscreen as Jafari, riding in a car with Panahi, watches the recording, distraught at the possibility that she has failed to help the girl. She also wonders whether Marziyah has really killed herself. Was the film edited to create that impression? Panahi thinks it looks authentic, and he drives Jafari out to the girl’s village to find out.

3 Faces is the fourth feature Panahi has made since his trial in 2010 and the resulting sentence banning him from filmmaking for twenty years. We had been following his career before that, most notably with The Circle and Offside. In happier days, David met Panahi briefly at the Hong Kong Film Festival, when they sat next to each other at an award ceremony. David posted an account of Panahi’s charges and sentencing in 2010. We have also written about films that Panahi has made since then: This Is Not a Film and Closed Curtain. Somehow, though we saw Taxi, we didn’t blog about it. Today Panahi remains unable to leave Iran to attend the festivals where his films are honored (3 Faces won the best-screenplay award at Cannes), and he has no access to studio facilities.

With 3 Faces, Panahi has moved on from making films about his plight and looks at the repression suffered by women and girls in the rural areas of Iran.

This time he follows the classic quest pattern of many of the golden age of Iranian cinema from the 1980s to the early 2000s. 3 Faces is perhaps most reminiscent of Kiarastami’s And Life Goes On, another director’s journey to the countryside to check on a child who may have died. It’s gratifying to see the fruitful quest pattern revived, and Panahi creates a work that is at once familiar and uniquely imaginative. The settings, mostly in Panahi’s car and the countryside of Iran near the Turkish border.

As in other such films, 3 Faces is as much about the unexpected encounters with strangers along the way: a wedding group celebrating on a steep mountain road, a woman testing out her own grave to make sure it’s comfortable, an old man who introduces Panahi to the patterns of honks locals use when approaching each other on the narrow roads. Upon reaching the village and encountering Marziyah’s family, it becomes apparent that they are baffled and annoyed by the girl’s ambitions to devote herself to a frivolous career rather than marry and settle down.

Jahari also encounters a retired actress from before the 1979 revolution, Shahrazade, now a recluse living in a tiny house near the village (see top). The “3 Faces” title apparently refers to the three generations of actresses, Shahrazade, Jafari, and Marziyah. This explanation is not apparent from the film, especially since Shahrazade is glimpsed only in extreme long shot from the back as she paints in a field.

Panahi has made a more acerbic film than those of Kiarostami, poking fun at the villages and especially emphasizing the way the men are obsessed with virility and controlling their womenfolk. Receding into the background despite his major role, Panahi takes p the feminism he displayed in Offside and reveals the more serious lack of freedom women and girls experience in rural areas. He does so without abandoning the humor that underlies many of the quest films.

Kino Lorber will distribute the film in the US, with a release planned for March, 2019.

Dressage (Pooya Badkoobeh, 2018)

Another trend in recent Iranian cinema might be termed the Farhadi effect. Asghar Farhadi has become the most prominent of the current group of Iranian directors, winning best foreign-language Oscars for both A Separation and The Salesman. His films tend to center around a serious mistake or a crime committed early on, with the varying reactions of the characters forming the bulk of the drama. In some cases sudden twists reveal motivations that tend to make the situation more ambiguous morally, and the rights and wrongs of the situation do not resolve clearly.

Dressage, Badkoobeh’s first feature, fits this pattern to some degree. A group of middle-class and upper-middle-class students are in the habit of robbing shops for thrills. As the film opens, they have robbed a small grocery store. When a clerk who lives in the store unexpectedly interrupts them, their leader knocks him out. Having fled, the group discovers that they have neglected to take the incriminating surveillance tape with them. The protagonist, sixteen-year-old Golsa, is sent back for it. Having retrieved it, she hides it in a bin at the stables where she helps take care of expensive dressage horses (above).

Golsa refuses to turn over the tape, either to the group or to her parents, all of whom wish to destroy the evidence. What Golsa plans to do with the tape is unclear, but she is subjected to more and more pressure to give it up. Along the way, her stubbornness begins to harm the very working-class people, such as the store clerk, whom she hopes to help.

The rather simple story is given some depth by Golsa’s love for one of the dressage horses. It’s made clear that such horses are valuable and must be exercised without letting them run free, which would risk damage to their legs, but at one point she takes her favorite into a field to frolic about.

Ultimately the film has less of the complexity and ambiguity of a Farhadi film, but it shows promise for a younger generation of Iranian filmmakers.

As far as I can determine, Dressage does not have a North American distributor.

Caphernaüm, aka Capernaum (Nadine Labaki, 2018)

I remember that during the Cannes festival, Kore-eda’s Shoplifters and Labaki’s Capernaum were among the films most often predicted to win the Palme d’Or. In the event, Shoplifters took the top prize, and justifiably so, and Capernaum received the Jury Prize, the second highest honor. Both films center around families living in poverty, though Shoplifters moves among the members of its family and emphasizes their mutual support. Capernaum, on the other hand stays resolutely with Zain, the 12-year-old boy who is so miserable that he takes his parents to court to sue them for having brought him into a wretched existence in the Beirut slums.

Labaki, determined to expose the reasons for the sufferings of children in the poorer areas of Beirut, spent three years researching the subject. She cast actual slum-raised children rather than actors and coaxed remarkable performances from them. It seems absurd to speak of a performance from the one-year-old girl who plays Yonas, the little boy whom Zain struggles to care for when the toddler’s Ethiopian-emigré mother is arrested for lack of proper papers; still, the child seems always to be doing exactly what is natural and appropriate for the situation. The result of working with non-professionals and children was 500 hours of footage to be edited down into a two-hour film. (The production information is from an interview with Labaki in The Hollywood Reporter.)

It seems churlish to find fault with Capernaum, which certainly must be given credit for exposing a side of life that most viewers will never witness. It mixes humor and pathos with a deft hand and is undoubtedly entertaining and thought-provoking. Yet there are moments when the film’s effort to tug at our heartstrings seems a bit too obvious and overdone. Some critics have been unqualifiedly moved by the film, while others find it a bit too manipulative. I suspect that most audiences who see it in art-houses in the US will share the reaction of the Cannes audience, who gave it a 15-minute standing ovation.

The meaning of the film’s title is intriguing, and some clarification might be helpful. I have given both its original Lebanese title, Capharnaüm, and the one used in English-speaking countries, Capernaum. They are variant spellings of the same word, but with different meanings. “Capharnaüm” is French and means “a confused jumble” or “a place marked by a disorderly accumulation of objects” (Merriam-Webster). It derives from the Aramaic spelling of the Hebrew name Capernaum, the village on the Sea of Galilee where Jesus is said in the Bible to have been based during most of his ministry.

The “confused jumble” derives from the large crowds that flocked around Jesus, as in Mark: 1-2:

And again he entered into Capernaum after some days, and it was noised that he was in the house.

And straightaway many were gathered together, insomuch that there was no room to receive them, no, not so much as about the door; and he preached the word unto them.

Labaki, being a Catholic (belonging to the Lebanese Maronite Church and having been educated at St. Joseph University in Beirut), would surely have been aware of both these meanings when she made her film. The notion of a crowded jumble applies well to the environments in which the children in the film live. Certainly the children belong to the downtrodden classes to whom Jesus ministered. Possibly the reference to Jesus’ miracles, several of were reportedly performed in Capernaum, helps to justify the implausibly upbeat ending of the film.

Capernaum will be released in the US by Sony Pictures Classics on December 14.

Birds of Passage (Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018)

Birds of Passage is the first film directed by Ciro Guerra since his excellent Embrace of the Serpent, which was the first Colombian film nominated for a foreign-language Oscar. This time he co-directs with his wife and producer, Cristina Gallego.

Birds of Passage is a very different film from Embrace of the Serpent. The latter is set in the Colombian Amazon region, focuses on the decimation of indigenous peoples by the rubber trade, is shot in black and white, and cuts between two time periods decades apart involving two explorers guided by the same indigenous guide. Birds of Passages is set in a desert region of northern Colombia, deals with the early effects of drug-trafficking among the Wayuu people of the area, is shot in color, and follows a single extended family chronologically through five periods between the 1960s and 1980s, each announced by a dated title.

The result is a plot that is much easier to follow than that of Embrace of the Serpent. While the earlier film was based around the evocative, mysterious hunt through the jungle for a fictional sacred plant, Birds of Passage is very much anchored in the history of the early marijuana trade that the central family becomes involved in, growing very rich in the process.

In the film, the first American customers who draw the ambitious hero, Raphayet, to obtain a small amount of marijuana for them are some Peace Corps volunteers. Soon criminal traffickers become customers for Raphayet’s wares, and the roughly two decades of drug-running that follow balloon into a business that ends with a war within the family (see bottom).

The title refers to a motif that is introduced in the opening scene, when teenage Zaida, of the foremost family among the Wayuu, finishes her official transition to womanhood with a ritual dance based on bird mating rituals. Raphayet offers to dance with her (above), and the task of meeting her mother’s high dowry price includes him making his first small drug deal. The motif of real birds continues, but migrating “birds of passage” is also a local term for the American traffickers who fly in and out in small planes, bringing money in such large bundles that have to be weighed rather than counted.

As a film, Birds of Passage is not as challenging or evocative as Embrace of the Serpent. Its fascinating story, however, deals with the little-known history of the origins of the South American drug trade, the growing problem that has caused such upheaval in the region and is very much still with us.

The Orchard has the US rights, with no announced release date.

Returning for a moment to the Venice International Film Festival, three publications generated by the 2018 festival are now available for sale.

Two of these publications result from the festival’s 75th anniversary this year. Peter Cowie’s Happy 75º: A Brief Introduction to the History of the International Film Festival offers a succinct, chronological account of the festival’s facilities, organizers, guests, and winners year by year. Reading it enlivened the time spent in line before films for both David and me.

The festival also presented a large exhibition of photographs, again presented year by year, celebrating the films shown and the stars attending. This exhibition was mounted in the legendary Hotel des Bains, closed in recent years but formerly housing many of the festival’s glamorous guests. It is mainly connected in the minds of most moviegoers with Visconti’s Death in Venice, which was filmed there. There are plans to renovate and re-open it. A large catalog containing what appear to be all the photographs from the exhibition has also been published.

Finally, this year’s program, with extensive notes on the films, is available.

All of these can be ordered from amazon.it. The program can also be downloaded.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help during our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Birds of Passage

Vancouver 2018: Crime waves

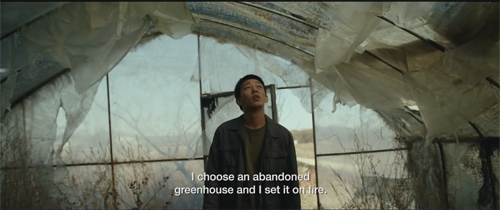

Burning (2018).

DB:

It’s striking how many stories depend on crimes. Genre movies do, of course, but so do art films (The Conformist, Blow-Up) and many of those in between (Run Lola Run, Memento, Nocturnal Animals). The crime might be in the future (as in heist films ), the ongoing present (many thrillers), or the distant past (dramas revealing buried family secrets).

Crime yields narrative dividends. It permits storytellers to probe unusual psychological states and complex moral choices (as in novels like Crime and Punishment, The Stranger). You can build curiosity about past transgressions, suspense about whether a crime will be revealed, and surprise when bad deeds surface. Crime has an affinity with another appeal: mystery. Not all mysteries involve crimes (e.g., perhaps The Turn of the Screw), and not all crime stories depend on mystery (e.g., many gangster movies). Still, crime laced with mystery creates a powerful brew, as Dickens, Wilkie Collins, John le Carré, and detective writers have shown.

We ought, then, to expect that a film festival will offer a panorama of criminal activity. Venice did last year and this, and so did the latest edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some movies were straightforward thrillers, some introduced crime obliquely. In one the question of whether a crime was committed at all led–yes–to a full-fledged murder.

Smells like teen spirit

Diary of My Mind.

Start with the package of four Swiss TV episodes from the series Shock Wave. Produced by Lionel Baier, these dramas were based on real cases–some fairly distant, others more recent, all involving teenagers. The episodes offer an anthology of options on how to trace the progress of a crime.

In Sirius a rural cult prepares for a mass suicide in expectation they’ll be resurrected on an extraterrestrial realm. The film focuses largely on Hugo, a teenager turned over to the cult by his parents. Director Frédéric Mermoud gives the group’s suicide preparations a solemnity that contrasts sharply with the food-fight that they indulge in the night before. Similarly, The Valley presents a tense account of a young car thief pursued by the police. Locking us to his consciousness and a linear time scheme, director Jean-Stéphane Bron summons up a good deal of suspense around the boy’s prospects of survival in increasingly unfriendly mountain terrain.

Sirius and The Valley give us straightforward chronology, but First Name Mathieu, Baier’s directorial contribution, offers something else. A serial killer is raping and murdering young men, but one of his victims, Mathieu, manages to escape. The film’s narration is split. Mathieu struggles to readjust to life at home and at school, while the police try to coax a firm identification from him. This action is punctuated by flashback glimpses of the traumatic crime. The result explores the parents’ uncertainty about how restore the routines of normal life, the police inspector’s unwillingness to press Mathieu too hard, and the boy’s self-consciousness and guilt as the target of the town’s morbid curiosity.

This insistence on the aftereffects of a crime dominates Diary of My Mind, Ursula Meier’s contribution to the series. This too uses flashbacks, mostly to the moments right after a high-school boy kills his mother and father. But there’s no whodunit factor; we know that Ben is guilty. The question is why. Ben’s diary seems to offer a decisive clue (“I must kill them”), but just as important, the magistrate thinks, is his creative writing under the tutelage of Madame Fontanel, played by the axiomatic Fanny Ardent. Because she encouraged her students to expose their authentic feelings, Ben’s hatred of his father had surfaced in his classroom work. Perfectly normal for a young man, she assures the magistrate. No, he asserts: a warning you ignored. The shock waves that engulf onlookers after a crime, the suggestion that art can be both therapeutic and dangerous, the question of a teacher’s duty to both her pupils and the society outside the classroom–Diary of My Mind raises these and other themes in a compact, engaging tale.

Last hurrah of (movie) chivalry

Chinese director Jia Zhangke is no stranger to criminal matters. His films have dwelt on street hustles, botched bank robberies, and hoodlums at many ranks. Ash Is Purest White is a gangster saga, tracing how a tough woman, Qiao, survives across the years 2001-2018. Initially the mistress of boss Bin, Qiao rescues him from a violent beatdown using his pistol. She takes the blame for owning a firearm. Getting out of prison, Qiao tracks down the now-weakened Bin, who has taken up with another woman.

Ash Is Purest White tackles a familiar schema, the fall of a gang leader, from the unusual perspective of the woman beside him, who turns out to be stronger than he is. Most of the film is filtered through her experience, and along with her we learn of Bin’s decline and betrayal, along with his integration into the corrupt and bureaucratic capitalism of twenty-first century China. The second half of the film shows Qiao forced to survive outside the gang’s milieu. A funny scene plays out one of her scams: picking a prosperous man at random, she announces that her sister, implicitly his mistress, is pregnant. Just as important, Qiao’s adventures allow Jia to survey current mainland fads and follies, including belief in UFO visits.

Among those follies, Bin suggests, is a trust in mass-media images. As Ozu’s crime films (Walk Cheerfully, Dragnet Girl) suggested that 1930s Japanese street punks imitated Warner Bros. gangsters, so Jia’s mainland hoods model themselves on the romantic heroes of Hong Kong cinema. They raptly watch videos of Tragic Hero (1987) and cavort to the sound of Sally Yeh’s mournful theme from The Killer (1989). They derive their sense of the jianghu--that landscape of mountains and rivers that was the backdrop of ancient chivalry–not from lore or even martial-arts novels but from the violent underworld shown on TV screens.

Bin’s decline is portrayed as abandoning those ideals of righteousness and self-sacrifice flamboyantly dramatized in the movies. But Qiao clings to the imaginary jianghu to the end. She explains to him that everything she did was for their old code, but as for him: “You’re no longer in the jianghu. You wouldn’t understand.” You can respect his pragmatism and admire her tenacity, but he’s still a feeble figure, and she’s left running a seedy mahjongg joint–one much less glamorous than the club she swanned through at the film’s start. Appropriately for someone who got her idea of heroism from videos, we last see her as a speckled figure on a CCTV monitor.

From dailiness to darkness

Burning.

Often the crime in question is presented explicitly, but two films leave it to us to imagine what shadowy doings could have led to what we see. In Manta Ray, by Phuttiphong “Pom” Aroonpheng, we get the familiar motif of swapped identity. A Thai fisherman finds a wounded man in the forest and nurses him back to health. The victim is a mute Rohinga whom the fisherman names Thongchai. They share a home and the occasional dance and swim, even a DIY disco.

But who attacked Thongchai in the forest, and why? And what is the connection to the unearthly gunman who paces through the forest, bedecked in pulsating Christmas bulbs? And what makes the foliage teem with gems glowing in the murk? Somewhere, there has been a crime.

Manta Ray accumulates its impact gradually, with the scenes of the men’s routines giving way to mystery when the fisherman vanishes and Thongchai (named by the fisherman for a Thai pop singer) is trailed by a ninja-like figure clad in a red cagoule. A disappearance and a reappearance (of the fisherman’s wife) punctuate moody scenes of trees and sea. The opacity of the action makes a political point: offscreen, Thais brutally hunt down the refugee Rohingas. But the critique of anti-immigrant brutality is intensified by the lustrous cinematography (Aroonpheng was a top DP). You can feel the texture of the planks in the cabin and the sharp edges of the gems that fingers root out of the forest floor. This is probably the most tactile movie I saw at VIFF.

Then there was Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Lee started his career strong and has stayed that way. The slowly paced, Kitanoesque gangster story Green Fish (1997) and Peppermint Candy (1999), with its reverse-order chronology, both achieved local popularity and established him as a fixture on the festival circuit. Oasis (2002), a daring romance of a disabled couple, won a special prize at Venice. Secret Sunshine (2007) brought Lee even more widespread fame. Like the episodes of Shock Waves, it dealt with the aftereffects of a horrific crime. Virtually everyone I know who saw the film remembers most vividly a particular scene: the heroine, having converted to Christianity and at last ready to forgive the perpetrator, visits him in prison. It’s one of the most nakedly blasphemous scenes I’ve ever seen, carried off with a shocking calm. Crime–this time, a gang rape–is also at the center of Poetry (2010), with another mother facing familial tragedy.

Most of these plots, particularly Poetry, are rather busy, but Burning is more stripped down (though not short). Lee Dong-su maintains the shabby family farm while his father is in jail awaiting trial. In town Dong-su meets Haemi, a former classmate now running sidewalk giveaways.

She lures him into her life by asking him to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, but before she leaves they start an affair. But he seldom breaks into a smile, favoring a puckered-lip passivity. After their coupling, we get his POV on a blank wall.

This turns out to be the first of many disquieting passages. Between bouts of tending livestock, feeding Haemi’s cat, and masturbating to her picture, Dong-su gets mysterious phone calls with no one on the line. He meets Haemi at the airport only to discover that she’s formed a friendship (or more?) with the suave Ben, whose gentle courtesy makes Dong-su feel an even bigger bumpkin. Soon the three are hanging out together, but at parties Dong-su can only stare at Ben’s yuppie friends. Dong-su, who wants to be a writer, is a fan of Faulkner, but Ben compares himself to the Great Gatsby.

After a long night of relaxing at the farm, with the men watching Haemi dance topless, she disappears. A black frame, a dream of a burning greenhouse, and Dong-su is left alone halfway through the movie. What happened to Haemi? And why does Ben say he enjoys torching greenhouses? Dong-su turns detective,

Lee is a master of pacing, and the deliberateness of the film delicately turns a romantic drama into a critique of entitled lifestyles and then into a psychological thriller. We are locked to Dong-su’s consciousness except for a couple of telltale shots of Ben calmly studying his rival from afar. We get Vertigo-like sequences of Dong-su trailing Ben and probing for clues and perhaps having more dreams. At the same time, Dong-su starts writing, as if Haemi’s disappearance has inspired him, but he finds more violent ways to release his simmering bewilderment.

After only one viewing, I didn’t find Burning as devastating a film as Secret Sunshine or Poetry, but I’d gladly watch it again and probably I’d see more in it. Lee manages to sustain over two and a half hours a plot centering on three, then two principal characters. He has earned the right to soberly take us into the mundane rhythm of a loner’s life and then shatter that through an encounter with two enigmatic figures who may be playing mind games. As with Manta Ray, we have to infer some of the action behind the scenes, but that just shows that in cinema, classic or modern, crime can pay.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Japadog, a Vancouver landmark.

Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the Rest of the World, the sequel

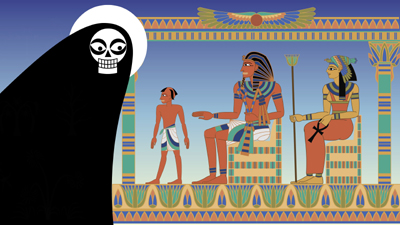

Seder-Masochism (2018)

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival is over, but we still have films to talk about. Here are four, and David and I will probably post another blog apiece. Between Venice and Vancouver, we have seen a lot of great and very good films recently. Once again, the claims of the death of cinema are robustly refuted.

Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018)

Garrone is best known outside Italy for his 2008 film Gomorrah. While that film was about gangs and organized crime in Naples, Dogman centers around a shifting relationship between a meek-mannered dog/boarder/groomer who has fallen in with a volatile, enormous local thug.

The title emphasizes the honest side of Marcello’s life, and we see some comic scenes of him with dogs. Soon, however, it is revealed that he sells cocaine on the side and sometimes acts as a getaway driver for thefts committed by the monstrous ex-boxer, Simoncino. Eventually he even takes the fall for a robbery and spends a year in jail in Simoncino’s place.

We’re clearly intended to side with this sad sack. After one house robbery, Simoncino’s partner reveals that he put a dog in the freezer to keep it quiet. Marcello sneaks back in and, a suspenseful and remarkable scene, attempts to revive the frost-covered animal. He also dotes on his daughter and seemingly pursues his criminal activities in order to be able to take her on “adventures,” including scuba-diving.

Despite this sympathetic side, however, Marcello never seems to consider giving up crime; he’s mainly interested in getting his fair share of Simoncino’s ill-gotten gains. Although the film is continually entertaining and suspenseful, its ending is somewhat disappointing. We are left knowing what Marcello’s probably fate will be, but we have little sense of his attitude toward what has happened.

Marcello Fonte, looking like a rather emaciated version of the comic Toto, won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Magnolia has the US rights and plans to release Dogman in 2019.

Seder-Masochism (Nina Paley, 2018)

Seder-Masochism is the only US film I’ll be writing about from Vancouver. (We tend to skip US films here, since we assume we can see them in the US.) Paley’s not part of the Hollywood establishment or even the mainstream indie scene. It’s not easy to see her wonderful animated films on the big screen, but their bright colors and imaginative graphics deserve to be shown that way.

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

Seder-Masochism is Paley’s second feature, after Sita Sings the Blues (2008). She does all the animation herself, holed up, as she puts it, like a hermit with her computer. She also avoids the standard distribution methods for indie films, because she’s an opponent of copyright for artworks. She provides open access to her films, initially at festivals and then online. (For more on this, see my transcript of a Q&A I helped run when Sita played at Ebertfest in 2008.)

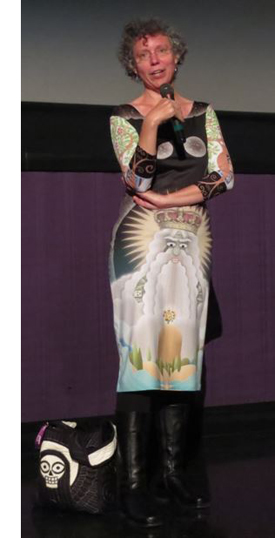

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

I should say that no one should assume from the title that this film is grim and/or anti-Jewish. On the contrary, it’s a witty exploration of the Exodus myth and its historical links to the decline of early goddess worship in favor of all-powerful male gods in monothesism. The framing situation is a conversation between Paley and her father conducted shortly before his death, with Paley as a small goat and her father as God (see top).

This conversation is a mix of humor and serious points about Judaic traditions and particularly the celebration of Passover. The story of Moses and the Exodus is rendered in much the same way she treated the tale of Sita and Rama from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana–with musical numbers. Moses is introduced with “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain, and, inevitably, there is a “Go Down, Moses” episode. Unlike Sita, where blues songs were used throughout, the musical pieces in Seder are wide-ranging, culminating in a brilliant three-minute summary of the history of the territory which is now Israel, done to “This Land is Mine,” the song written to the theme of Otto Preminger’s Exodus. (The sequence, as well as several other excerpts from Seder are available on YouTube.)

The sequences set in ancient Egypt are generally accurate. I was amused by the fact that the animal and bird hieroglyphs in the background inscriptions moved rhythmically during the musical numbers, and the Hathor heads on the sistrums sang along. Using Hathor, the cow goddess, as the golden calf was an inspiration.

Seder-Masochism got the most enthusiastic applause I heard at the festival, partly because the filmmaker was present (in her custom Seder dress). There were Sita fans in the audience, and one Jewish lady asked how she could get a copy to show her 12-year-old daughter. Paley replied that the film will continue to play festivals and probably be available on the fim’s website for download in the spring.

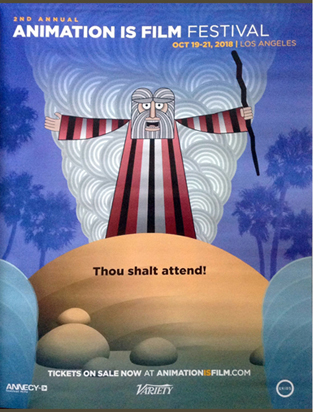

In the meantime, watch for it at festivals–or let the organizers know that you want to see it on their schedule. We were happily surprised to see a full-page ad for the Los Angeles Animation Is Film Festival (October 19-21) in the current Variety (above left) and illustrated by an image derived from the film. You may find others.

Styx (Wolfgang Fischer, 2018)

I was surprised to discover that so far Austrian director Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx has not been picked up by a North American distributor. It seems like the sort of film to appeal strongly to audiences. It’s protagonist is a strong, ultra-competent woman, it has a riveting plot full of suspenseful situations, and it deals with the immigrant crisis facing Europe.

A long portion of the film contains no real dialogue. The opening sequence occurs at the scene of a traffic accident where the heroine, Rike, is established as a doctor as she heads the team treating the victim. Cut to her provisioning her yacht for a solo trip. A lovely shot of a compass “walking” its way down a map establishes her route and distant goal: Ascension Island (see bottom). Her departure reveals that her starting point is Gibraltar (above). From that point, we watch Rike expertly dealing with her vessel, enjoying the solitude of the ocean, and reading about Darwin’s activities on Ascension.

Apart from a few overheard commands during the initial emergency scene, there is no dialogue until Rike makes radio contact with a nearby commercial vessel which warns of a serious storm approaching. A tense scene of her struggle to deal with the storm at night creates the first major suspense of the film. From her arrival in an ambulance in the opening sequence, actress Susanne Wolff is present in every scene, and as an experienced sailor she was able to handle the yacht and do without a stunt double.

Rike comes through the storm without difficulty, but a leaky vessel crowded with African immigrants striving to get to Europe is visible in the distance. Ordered by a coast-guard official not to interfere, she uneasily waits for a sign of a rescue vehicle that still has not shown up after hours of waiting. One teen-aged boy manages to swim from the derelict ship, and he complicates her situation considerably. The dilemma remains: try and take the rest of the refugees on board her small yacht or wait for the promised rescue.

The remainder of the film generates unrelieved suspense as Rike debates what to do and Kingsley begs her to rescue his sister, still abroad the sinking boat. A non-actor discovered in a school in Nairobi, Gedion Oduor Weseka is convincing and touching as the desperate boy.

Nearly all of Styx was shot at sea, with Fischer’s small crew mounting their camera hanging off the sides of the boat and scrambling to keep out of sight during filming. No special effects were used for the storm and other ocean scenes. At intervals some impressive extreme long shots from overhead, presumably taken by drones, emphasize the yacht’s isolation in the vastness of the sea.

The film is riveting from beginning to end. I recommend it, though at least for North America, festival screenings are probably the main places where it can be seen. Perhaps it will eventually be available on streaming services. In some European countries, it will probably be released theatrically.

Transit (Christian Petzold, 2018)

The central premise of Transit resembles that of Casablanca. A group of émigrés are desperately awaiting the letters of transit that will allow them to flee fascist Europe for North America. In this case they’re in Marseille rather than Casablanca, and the plot focuses on one rather ordinary, non-heroic man–or so he seems. Our protagonist is Georg, a Jew lingering in Paris as the authorities arrest fugitives. The authorities are working for a fascist regime, though Nazis are never mentioned specifically.

Moreover, the settings and costumes are mainly modern. Early on Georg flees a round-up through allies covered with spray-painted graffiti (below), and the vehicles in the streets are all contemporary models. Petzold’s avoidance of period mise-en-scene sets up a strange, somewhat surrealist world, but it also invites us to consider the parallel with current social problems.

By chance Georg gains possession of the manuscripts and papers of Weidel, a well-known author who has met a bloody end in a cheap hotel room. Fleeing to Marseilles with a wounded fellow Jew who dies along the way, Georg visits the Mexican consulate and is mistaken for Weidel, whose transit papers for him and his estranged wife have been approved. Naturally Georg accepts the error. While waiting for the papers to come through, he befriends his dead friend’s widow and her son, immigrants to Europe from the Maghreb, and by chance encounters and falls in love with Weidel’s wife (who does not realize her husband is dead), hoping to use the two letters of transit to escape to a new life with her.

Between the inexplicable modern settings and costumes and the extraordinary coincidence of this meeting, the film is far from being realistic. It reminded me of the late films of Manoel de Oliveira (see our earlier reports on Doomed Love, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow), with touches of Bresson in the situation and the acting, particularly of Franz Rogowski as Georg. But Petzold is not simply imitating these and other directors. Transit is a remarkable, original film, one of the best we saw at Vancouver.

Transit has been acquired for US distribution by Music Box for an early 2019 release. Definitely keep an eye open for a screening near you, most likely in festivals and large-city art houses and perhaps eventually on streaming..

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Styx (2018).