Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

Vancouver 2018: A Panorama of the Rest of the World

The Wild Pear Tree (2018).

Kristin here:

Venice, Telluride, and Toronto get a great deal of attention, since obsessive, year-round Oscar-predicting has become a way of life for some reviewers and industry commentators. In contrast, Vancouver has few premieres, but it quietly gathers up a huge international range of films, most of which have already played other festivals. It offers a chance to see fine films, many of which will never enter the radar of those who search only for Oscar bait. Venice and Vancouver, the two VIFFs, offer a perfect combination to keep us up-to-date.

There are several major threads in the program, including documentaries, socially impactful films of all sorts, Canadian films, and so on. I tend to favor the Panorama: Contemporary World Cinema thread, since it’s the one that basically breaks down the ROW (the Rest of the World) by country, and I try to see a wide range of world cinema. It’s also where familiar auteurs that I follow tend to show up.

This entry covers three films by directors whose work I have seen and admired, representing Iceland, Turkey, and Poland. More ROW films to come.

Woman at War (Benedikt Erlingsson, 2018)

Four years ago David reported on Icelandic director Erlingsson’s first feature, Of Horses and Men. This year we enjoyed his second, Woman at War. It tackles the difficult task of making a heroine who is basically a terrorist, though one might more tactfully call her an rather extreme environmental activist.

We first see her taking out the local power grid by firing a wire via bow-and-arrow over power lines in a remote rural area (above). She’s resisting a large Chinese investment in Iceland’s infrastructure, and she seems to be succeeding. The Chinese have postponed the deal, but she carries on her nearly one-woman crusade, aided only by a government official who is getting cold feet as the search for the “Mountain Woman” saboteur escalates, and an “alleged cousin,” a gruff farmer who rescues her more than once.

David praised how visually Erlingsson told his tale in Or Horses and Men. The same is true for the long scenes of Halla’s forays into the countryside for her subversive errands, as well as her preparations. She is clearly a highly adept and well-equipped saboteur, and she’s bold and skilled enough to outfox the military pursuers who send helicopters and drones after her.

Despite the serious theme, Woman at War is a lighthearted film. As Variety reviewer Jay Weissberg put it, “Is there anything rarer than an intelligent feel-good film that knows how to tackle urgent global issues with humor as well as a satisfying sense of justice?” One could called Halla a terrorist, but the audience we saw it with was clearly on her side, hoping for her to escape at each narrow brush with the law.

The whole thing is funny enough to be termed a comedy, or at least a dramedy. Halldóra Geirharðsdötter makes Halla an irresistably likeable character, and Erlingsson gives her emphatically ladylike activities in her life outside her clandestine campaign: she conducts a local choir and is in the process of adopting a Ukrainian orphan.

One daring move that Erlingssohn makes is to put the musicians playing the accompanying musical track onscreen, both a chamber group of three male instrumentalists who crop up nearly everywhere Halla goes, and a trio of female singers in Ukrainian dress who appear in scenes relating to the adoption. At first this seems like a joke simply repeating the one early in Blazing Saddles where the hero rides past Count Basie’s Orchestra playing the apparently nondiegetic sound track in the middle of a desert. Here the musicians appear through most of the film. They help avoid having Halla alone onscreen for long stretches of time, they appear sympathetic to her changing situations and hence cue us to sympathize with her, and they provide part of the film’s comedy. They took some getting used to, but I think the “onscreen nondiegetic music” device worked overall.

Shortly after its premiere in the Critics Week thread at Cannes, Woman at War was picked up for North America by Magnolia Pictures. Audiences should give it a look, since it’s a real crowd-pleaser.

The Wild Pear Tree (Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2018)

My entire knowledge and admiration of Turkish director Ceylan’s work come thanks to VIFF. In 2011 we wrote about Once upon a Time in Anatolia and in 2014 about Winter Sleep. This year The Wild Pear Tree is being shown.

It’s a very fine film, though I doubt audiences will embrace it to the extent that they did Once upon a Time in Anatolia or even the less popular Winter Sleep. The former may have qualified as slow cinema, but it had the advantage of being a mystery centered around a murder and a lengthy search for the missing body. In the process it became a character study and a quiet satire on the police. Winter Sleep was more talky, but it featured arguments between two witty people, a crotchety ex-actor and his acerbic sister.

In The Wild Pear Tree, Ceylan tackles the challenge of another film with long conversations. But this time the plot centers around Sinan, an opinionated, bitter, argumentative recent college graduate returning to his hometown. He is, in short, an obnoxious protagonist, and we’re attached to him in nearly every scene. He argues with his father, a teacher with a serious gambling addiction that has impoverished the family, with his mother, whom he blames for putting up with his father’s problems, and with essentially with anyone else he encounters.

Sinan’s stated goals are simple: to publish a book of his own poetry and fiction and to become a teacher in the eastern part of Turkey, as his father had early in his career. He also reluctantly faces performing his required military service. Yet he doesn’t study for the teaching exam, perhaps out of laziness or perhaps because he fears following in his father’s footsteps.

The result is a film that I found more admirable than likeable. Certainly its portrait of Sinan captures a certain recognizable type of self-assured, stubborn character, and there is a certain humor in that portrayal.. The highlight for me was a lengthy conversation between Sinan and Mr. Süleyman, a successful local novelist whom he spots at work in a local bookshop. Receiving permission to ask a single question of the man, he sits down and proceeds to question him at length, in the process managing to imply that he knows more about writing than Süleyman does. Sinan even pursues him out of the store and down the street, arguing, until Süleyman finally loses his patience and berates the young man. Any professor will recognize this spot-on depiction of a tiresomely persistent, argumentative student.

I found the ending a bit too pat and easy. Sinan’s military service, rendered in one relatively brief shot, apparently purges him of much of his anger with his life, and the final reconciliation with his father seems to come far too easily.

The film is beautifully photographed (see top), as always, by Gökhan Tiryaki, this time using a Red 6K digital camera.

Cinema Guild plans an early 2019 release for the film in North America.

Cold War (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2018)

Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski’s first feature film since the award-winning Ida (2013) is quite a departure from that film’s austerity, despite again being beautifully filmed in black-and-white film with an Academy aspect ratio. It follows the tempestuous relationship between a young singer and the composer-pianist who mentors her and becomes her lover. The backdrop is the era from 1949 to the mid-1960s, set mostly in Poland but moving among the European cities that the pair visit, alone or together.

Cold War establishes an immediate appeal by showing a man, Wiktor, and his partner Irena (professional and perhaps personal) making ethnographic recordings of untutored peasants singing and playing traditional folk songs. The pair join the faculty of a state school for young singers, instrumentalists, and dancers. One auditioning singer, Lula, attracts Wiktor, and the two are soon involved in an affair that lasts, on and off, until the end of the era.

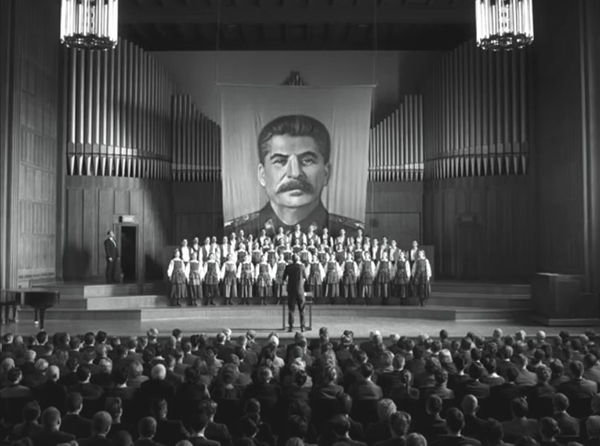

The film’s first half is fascinating, with its presentation of Polish folk-songs and dancing. The troupe formed by the school’s students becomes a success by presenting more professionally rendered versions of the folks songs and dances that had been collected. It soon attracts the attention of Communist authorities who pressure the Wiktor, Irena, and the manager, Kaczmarek, to add pro-Stalinist numbers to their program, and soon the group is singing “The Stalin Cantata” to equal success (see bottom).

Scenes fade to black at intervals, with the new scene appearing with a title giving the time and place of its action. These temporal jumps forward become more frequent as Wiktor becomes disgusted with the government’s control over the group’s program and flees to Paris. Thereafter the original troupe is left behind, and we see a series of scenes in which Lula’s path crosses Wiktor’s.

The result is that the second half of the film seems sketchier and less interesting. The action repeats, with variations, and the music that the pair perform is more familiar.

The highlight of this late part of Cold War is a scene which breaks loose briefly from the lovers’ travails. Lula and Wiktor at in a bar, and she, thoroughly drunk, initially begins to dance by herself to “Rock around the Clock.” In a remarkable long take, the camera moves among the wildly dancing couples as Lula passes from one partner to another and other couples pass by in the foreground and background (above). The moment must have been carefully choreographed, with the camera always capturing key moments of Lula’s enjoyment of the music, while simultaneously suggesting spontaneity and the crowd’s utter abandon to the music.

Cold War‘s music has been singled out by reviewers as a crucial ingredient. The film begins with craggy peasants performing genuine folk music in a muddy street and eventually takes us to Lula tarted up in a black wig and sequined dress singing a bizarre Polish version of “Baio Bongo,” a popular South American import deemed safe for audiences in the Soviet sphere. In between there are folk songs and dances, Stalinist choral propaganda, jazz, torch-song versions of the folk songs heard earlier, and rock-and-roll.

The film provides almost no background information about the two main characters or what they do in the several temporal gaps, some years long, covered by those fades. This makes it difficult to sympathize deeply with Wiktor and Lula’s long, ill-fated romance.

Pawlikowski in fact concocted some backgrounds for them, which he discusses in the film’s pressbook (posted in its entirety on Antti Alanen’s blog) .It draws upon extensive quotations from the director. There is considerable information about the historical, political context, including the fact that Wiktor and Lula are based on his parents. There is also discussion of the music, cinematography, and casting.

Pawlikowski speaks of the frequent ellipses as the film jumps forward in time:

Very often films, especially biopics, are weighed down by the need to feed information and explain; and the narrative is often reduced to causes and effects. But in life there are so many hidden causes and unpredictable effects – so much ambiguity and mystery that it’s hard to convey it as conventional cause and effect drama. It’s better to just show the strong and significant moments in the story and let the audience fill in the gaps with their own imagination and experience of life.

Reading the pressbook, I found myself wishing that at least some of the information therein could have been included in the film. There certainly would be time, since Cold War runs about 80 minutes sans its credits.

Amazon acquired Cold War for North America last year after its premiere at the Berlin Film Festival. It has announced a December 21 limited theatrical release.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Cold War (2018).

Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors

The Eyes of Orson Welles (2018).

DB here:

If you want to make a biographical documentary, you face problems of structure. Do you go chronological—start with birth, go through youth, maturity, and death? Or do you start in medias res, at the peak of fame or the depths of failure, and flash back to origins and development? Or do you do something else altogether? These are essentially the same problems of narrative that face the fiction filmmaker, but of course the documentarist also confronts gaps in the record, incompatible information, and the prospect that the story has been told before and may benefit from a fresh perspective.

Two documentaries at Vancouver tackled these problems in instructively different ways.

How to become famous: Work very, very hard

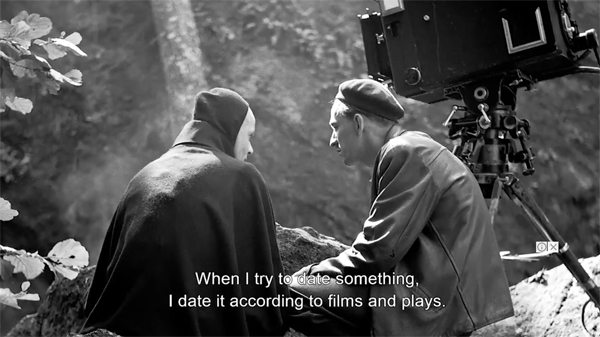

True to its title, Jane Magnusson’s Bergman: A Year in the Life picks Ingmar Bergman’s breakthrough in 1957 as its through-line. It was indeed quite a year: The Seventh Seal opened in January, Wild Strawberries in December, and Brink of Life was filmed in between (to open in early 1958). Very soon, Bergman won acclaim as one of cinema’s greatest artists. In the same annus mirabilis Bergman directed a TV drama and four theatre productions, including a monumentally successful five-hour version of Peer Gynt. All this he accomplished while suffering intense stomach pain; for part of the year he was in the hospital.

To survey only the events of January through December would leave us in the dark about the director’s full accomplishment, so the calendar format becomes a sort of clothesline on which incidents from all across his life are pinned. Since Bergman’s published memoirs are notoriously unreliable, Magnusson says that the films are more faithful records of his life and obsessions. But she also opens up many documents that fill in or correct his account, and the result becomes a fairly chronological survey.

For example, early in the documentary we learn of Bergman’s real relation to his father, his youthful admiration for Hitler during his stay in Germany (“I shouted like the others. I raised my hand like them”), and his first lover Karin Land, a spy for Finnish intelligence. As the film proceeds through 1957, it surveys his prior career and points ahead as well. Through associational links, motifs in The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, along with a survey of his childhood and his sexual partners, in effect provide flashforwards to Persona, Fanny and Alexander, and other later works.

The wellsprings of Bergman’s astonishing 1957 output are only hinted at. He was obviously a workaholic, as several commenters point out. One observer reminds us that Fassbinder had years that were as brutally productive, but he owed his stamina to drugs; for Bergman, the fuel was Swedish yogurt, Marie Biscuits, and sex.

Still, I wonder whether advancing through the Swedish film business, a rather industrially strict one, may have accustomed him to a killing pace. He started as a screenwriter at age 26, and he took up film directing two years later (not an uncommon age to begin). From 1948 on, he often signed two films a year as director and a third as a writer. You could make a case that his first breakthrough was really 1953, with the remarkable duo Summer with Monika and Sawdust and Tinsel. From the start, he was directing plays as well; in that same 1953 he mounted five. 1957 seems a landmark because the two films of that year became official international classics, winning festival prizes and wide distribution, but the man’s volcanic drive seems to have been there for a decade before.

In any case, the year-in-the-life format provides a handy point of entry into an astonishing, lengthy career. Magnusson has excavated many valuable documents and collected striking testimony, not least from coworkers whom the great man energetically humiliated. I learned a lot, not least that you can free up your documentary from the constraints of sheer chronology.

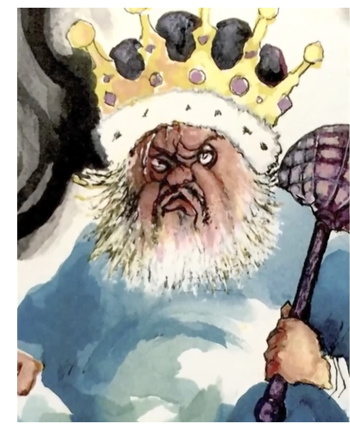

The Great Man draws

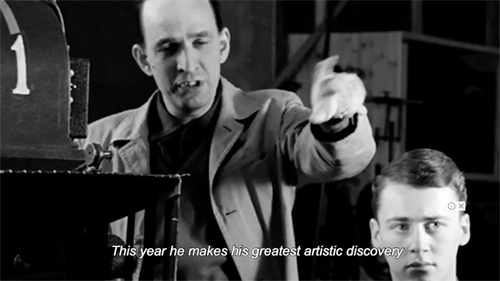

The same lesson issues more strikingly from Mark Cousins’ essayistic The Eyes of Orson Welles. Welles was of course another workaholic, moving across media freely. His energy was no less titanic than Bergman’s. For years we’ve known Welles the stage director, Welles the radio impresario, Welles the actor, and Welles the moviemaker. Now Cousins shows us Welles the graphic artist, and it’s a captivating, revelatory angle.

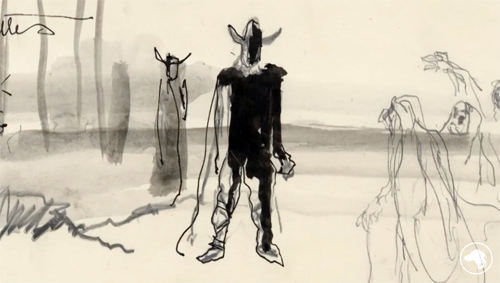

Welles started drawing as a child, and he later declared that painting was more important to him than filmmaking. Cousins examines hundreds of pictures archived at the University of Michigan and held by Welles’ daughter Beatrice. His film argues, with shrewd penetration, that a pictorial sensibility was central to Welles’ creative project. “You thought with lines and shapes. Your films are a sketchbook.”

How to structure this exploration? The film appears to offer trim boxes within boxes. Framing it all is a letter written and spoken by Cousins to the departed Welles. That apostrophe is in turn broken into numbered parts, some of which are in turn chopped into short topical segments. But these are engagingly digressive and untidy. For instance, part 3, devoted to Welles’s loves, skips from love of places, to love of vision itself (and Dolores Del Rio in Bird of Paradise), to love of chivalry, to omnivorous love (male friends), and finally to guilt over the death of love. A bit of Borges, a dash of Chris Marker: the swarming categories rub together in a cubistic way that Welles himself would probably have enjoyed.

In this porous, expanding design, Cousins takes us through familiar biographical terrain. The idea of Welles the graphic artist functions like 1957 in Magnusson’s film, a convenient wedge to open up episodes from family life and professional career. But Cousins brings out the pictorial side of well-covered material, such as the stage designs for the Harlem Macbeth. And he gains a lot from the frankly personal perspective. By writing a letter, he can ask rhetorical questions, mull over associations, imagine how Welles would view the modern world, and freely speculate on hidden autobiographical elements. “You wanted to be Falstaff, but you were Prince Hal.”

I came to Cousins’ film expecting a treatise on Welles’ cinematic style, and we get doses of that, but in unexpected ways. It turns out that most of his drawings don’t look a lot like his shots. Cousins floats the idea that Welles’ stay in Chicago, city of skyscrapers, may have tutored him in the low angles we see in his movies, but this seemed to me a stretch. Sketches of faces do, however, remind us of his fascination with actors, and of course his plans for sets, both on stage and on film, are very revealing.

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

The obvious comparison is with the drawings of Eisenstein, perhaps more skillful than Welles’s, but equally suggestive of the filmmakers’ obsessions. Like Eisenstein as well, Welles shows a rueful humor in his sketches. Cousins acknowledges this streak in yet another section, a hypothetical posthumous reply from Welles to Cousins’ letter. Welles chastises his biographer for playing down the lighter side of his films and pictures. This is nicely illustrated by charming drawings for Christmas cards Welles sent his children. But Cousins shows the fun running down. Over the years Santa’s face droops and wobbles, the eyes grow hollow and the mouth goes slack. Santa as another ageing Welles tyrant? A teasing juxtaposition like this offers another reason to let The Eyes of Orson Welles train ours.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

For more on Bergman and Welles, see our categories devoted to the directors, on the right. A list of Bergman’s productions in film and other media is here.

Bergman: A Year in the Life (2018).

Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined

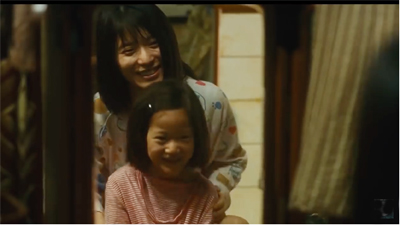

Shoplifters (Kore-eda, 2018).

DB here:

We’ve been attending the Vancouver International Film Festival since 2004. (The entries are tagged here.) It’s provided us many of our happiest viewing experiences, and this year is proving just as exciting. In particular, the festival’s long commitment to new films from Asia hasn’t flagged. Thanks to programmers Shelly Kraicer and Maggie Lee there has been plenty to showcase trends in Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, South Korea, and other lands. We won’t, unfortunately, be here for Hong Sangsoo’s Grass, but here are interim reflections on four items that we’ve seen in our first days.

Families, fraught and fragile

Shoplifters.

Girls Always Happy is a quiet but ingratiating first feature from Yang Ming Ming. Mother and daughter are both writers, and they struggle to live together in harmony while hoping for a legacy from Grandfather and for some resolution in their love lives. Yang says that she based the film on her own life, which rings true when you consider the range of emotions that well up. The two women tease each other, insult each other, ravenously devour meals together, shop partly to annoy sales staff, and sometimes burst out in screams. Reconciliations may be temporary but are still heartfelt.

With the two of them jammed together in a hutong, a neighborhood of cramped old ground-floor apartments, their jousts take on an intensity captured by Yang’s exceptionally tight framings and rapid cutting. Yang storyboarded the entire film, which allowed her quite precise control of composition and focus.

The relentless close-ups allow both psychological intimacy and subtle performances, as well as comparison of eating styles. Trips outside—Wu on her scooter or in her lover’s modern apartment, the mother at a hair salon—provide a respite from what’s essentially a series of escalating two-handed combats. The final shot is a lengthy take that carries our heroines forward into their city. Yang explained in the Q & A that after a film full of fast cutting and lots of talk she decided to end with the sort of long take Chinese filmmakers favor. In this context, with a canny use of a bus’s rearview mirror, the shot becomes an exhilarating, floating passage into the Beijing night.

Girls Always Happy came to VIFF garlanded with awards, including prizes from both the Berlinale and the Hong Kong Film Festival. Even more honored was the latest by Kore-eda Hirozaku, The Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It’s another of his family dramas (we’ve discussed Still Walking, I Wish, Like Father, Like Son, Our Little Sister, and After the Storm), but here the notion of family is given an uncanny twist at the end.

Each member, as per Kore-eda’s habit, is given a specific, respectful delineation. There’s the happy-go-lucky Osamu, a day laborer who both coddles the boy Shota and leads him into petty crime. There’s the maternal Nobuyo who works at a dry-cleaning facility and pilfers what she finds in pockets. Twentysomething Aki works at a sex club flashing her breasts and bottom at men crouched behind one-way mirrors. Grandma keeps the group going with her pension, her pachinko-playing, and some secret sources of income. Into this household comes Yuri, an abused child brought home like an abandoned cat.

Like Tsai Ming-liang’s more somber Rain Dogs, this is a film about people on the margins. The kids don’t go to school; Shota teaches Yuri the tricks of shoplifting, while Aki warms to a sex-club client. As in Girls Always Happy, interiors are sharply distinguished from exteriors, but not by close framings and shifting focus. Instead, master shots fill the frame with the detritus of seven people jammed in together. (See shot above.)

In a film so concentrated on characterization, we naturally get the sort of privileged moments that Kore-eda excels in. Osamu pauses in his construction work to stand looking around an unfinished apartment—a modest one, but a home he can never have. The young kids collect cicadas. Aki cradles a lonely punter in her lap. Nobuyo consoles Yuri by comparing the girl’s scars to burns Nobuyo has accumulated from ironing clothes. Grandma, watching her charges play on the beach, pours sand to cover the age spots on her legs. The ensemble comes together in moments of shared joy at the seaside or watching the fireworks at the Sumida River festival.

But these moments don’t prepare us for the unsettling revelations about the characters’ pasts that we get in the last half hour. Even here, though, the details of behavior remain indelible. One astonishing shot turns a cinematic staple—a woman trying to wipe away tears—into a tour de force of facial performance by Ando Sakura.

The Shoplifters reminded me of Ozu’s Passing Fancy and Inn in Tokyo, obliquely but sharply condemning the economic conditions that push people into wayward lives. It’s a gently subversive film about people flung together resourcefully trying to survive and find happiness by flouting the comfortable norms of middle-class morality.

Time out of mind

A Land Imagined.

Lush Reeds, by Yang Yishu, has plenty of the long takes that Girls Always Happy avoids. In nearly abstract framings, newspaper reporter Xiayin moves through minimalist offices and country lanes, bleak apartments and dense foliage.

As in many postwar films, drama sometimes becomes subordinate to the walks taken by the protagonist into an overwhelming, mysterious environment.

Against the wishes of her politically cautious editor Xiayin inquires into complaints of rural pollution. At the same time, she’s pregnant and is growing distant from her fairly cold husband. Her visit to the countryside becomes a threatening experience that brings to light parallels between the death of a villager and the apparent suicide of a fellow reporter.

The film is less linear than I suggest. Yang breaks up the story into midsize chunks and sets them out of order, so that some images–a little girl who meets Xiayin in the village, a shoe on a riverbank, the rescue of a suitcase from a rubbish depot–could fit into one time frame or another. Yang is even so bold as to run the title credit again midway through the film, suggesting that what follows might be backstory, or imagination, or an alternative film, or something in between.

A similar ambiguity pervades A Land Imagined (2018), another prize-winner (Golden Leopard, Locarno). It centers on a migrant worker Wang working at a Singapore site devoted to extending the coastline with sand dredged up or brought from other countries. Wang has disappeared, and the investigating cop Lok soon learns that Wang’s Bengali friend Ajit has vanished as well. A flashback takes us into the backstory, showing Wang spendiing his nights at a cybercafé and getting harassed by a troll who invades his videogame screen. Wang also begins a chaste affair with the tough gamine Mindy who oversees the game parlor. Eventually the flashback turns into a parallel, dreamlike narrative, with Ajit by turns dead and alive and Lok reenacting scenes involving Wang.

Director Yeo Siew Hua has given this noirish tale an appropriately lustrous treatment, with saturated long shots of black derricks looming against a red sky or sunk in sickly orange murk. Lyrical slow-motion musical interludes enhance the dreamlike ambience, and there’s a post-Wong-Kar-wai freedom of camera placement in the candy-colored cybercafé.

In his comments after the screening, Yeo spoke of trying to provide a counter-image to “the postcard, Crazy Rich Asians” depiction of Singapore. The shifting time frames and uncertain stretches of subjectivity are connected, for Yeo, with a sleeplessness suffered not only by the main characters but also by the population at large. The “land imagined” isn’t only the sand that expands the contours of the shoreline but also the hallucination of a hypermodern city state built on the labor of workers who can conveniently go missing.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Girls Always Happy.

Dragons, tigers, and two programmers

Yellowing (Chan Tze Woon, 2016).

DB here:

It was Asian film that brought me to the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2006, when Tony Rayns asked me to serve on the Dragons and Tigers awards jury. Ever since, Kristin and I have been returning; Tony made VIFF North America’s prime venue for cutting-edge Asian film. Name a major director from the region, and you’ll find that Tony scouted his or her early work for Vancouver.

For some years now, Tony’s co-programmer has been Chinese cinema expert Shelly Kraicer, who has been no less energetic in seeking out exciting new films. You can survey their track record by scanning our VIFF blog entries across the years.

Out of the many films in this year’s D & T retrospective, here are five that I especially admire.

Genres redux

Godspeed.

Across his career, Kore-eda Hirokazu has been a genre pluralist, but in recent years he seems to have settled into the shomin-geki, the bittersweet tale of lower-middle-class life. On the heels of Our Little Sister comes another family dramedy, After the Storm.

Once a prize-winning novelist, Ryota (the lanky, lantern-jawed Abe Hiroshi) is now a racetrack addict and a cheap detective not averse to shaking down high-school kids. After his father dies, and under the jaundiced eyes of his mother, he makes feeble efforts to reunite with his divorced wife and his baseball-playing son.

As usual with Kore-eda, everything flows in simple, unforced fashion, with every shot trimly composed and expertly timed. The emphasis falls on the actors, particularly as they’re captured in mundane activities. Ryota’s mother and sister are first seen writing thank-you notes to people who came to the funeral; he swills in fast food and throws away money on lottery tickets.

Ryota is one of Kore-eda’s most objectionable protagonists. He uses his admittedly minimal surveillance skills to spy on his wife, and he tries to swipe a family scroll to pawn. In an American film, this unlikable loser would pass through an arc that makes him caring, sharing, and on the road to rehab. Instead, as in many Japanese films, the unhappy character relapses into childhood—here, curling up with his son inside a playground octopus during a typhoon. It’s his effort to mimic a bonding moment with his father, but does it succeed now? Kore-eda isn’t betting on it.

Altogether less tranquil is Godspeed, from the Taiwanese director Chung Mong-hung. Chung has given us the horror film Soul (2013), the well-received Fourth Portrait (2010), and the lively Parking (2008), which I reviewed at an earlier VIFF session.

Godspeed is a Tarantinoish excursion into the underworld. It alternates violent scenes of betrayal and reprisals with comic interludes involving a drug courier and the taxi driver he’s hired to carry him to meet the bosses. The film is made with great panache, but for me what makes it noteworthy is that the driver is played by the great Michael Hui, dean of sour Hong Kong social satire.

Hui made his name as a television star before switching to films like The Private Eyes (1976), Security Unlimited (1981), and our favorite, Chicken and Duck Talk (1988). Godspeed revives Hui’s comic persona, the tight-fisted, corner-cutting bargainer who isn’t as clever as he thinks. As Old Xu, he reminisces about Hong Kong traffic and marital woes while trying to wangle a high fare from the phlegmatic, not overbright drug mule. Their misadventures—stumbling into a funeral, being stuffed into a car boot—serve as a counterpoint to the drug war escalating around them. No masterpiece, Godspeed is a beguiling exercise and a welcome return to a legendary and apparently ageless figure of Chinese cinema.

Mysterious, and fun

Another year, another stroll through Hong Sangsoo’s garden of forking paths.

With compositions that are about as banal as they can be, the films don’t aim to dazzle us pictorially. (Nice lighting, though.) The basics are really basic: Straight-on angles, fixed long take two-shots, simple come-and-go pans, an occasional and inexplicable zoom. These are his tools.

Dialogue and performance drive the action, which consists mostly of chance encounters and conversations in cafés, bars, restaurants, and bedrooms. His characters are students, artists, and film directors (usually fairly pretentious ones). Romantic hookups emerge, only to dissolve or play themselves out in parallel worlds, the whole presented in a “stacked” arrangement of modular scenes.

These scenic blocks display an obsessive, almost never mechanical, recourse to split viewpoints, recursive time schemes, mirror inversions, and whimsically varied replays. I’ve argued earlier that these permutations often test our faulty memory for exactly what transpired in a scene many minutes before, but it should be noted that sometimes, as in the last stretch of Oki’s Movie (2010), he’ll set the variations side by side.

Or maybe just side by side in your head. If the auteur theory didn’t exist, it would have to be invented to account for the effect of Yourself and Yours. In any other movie, when a man recognizes a young woman in a café, and she says he’s mistaken her for her twin, we might be inclined to take it as a brush-off. In a Hong movie, the scene makes us think back through all his other plots that have relied on doubling. So maybe this time he’s found a new variation? Has he got an actual pair of twins who will circulate through the scenes, constantly being taken for one another?

Suffice it to say that the young woman (women?), repeatedly encountering three men who are attracted to her (them?), becomes (become?) the pretext for the usual Hong mockery of male vanity and insecurity. The lackadaisical painter Youngsoo is worried about his girlfriend Minjung, who drinks more than he’d like. Moreover, his friend reports that she’s been seen with other men. Quickly enough, we spot her sharing drinks with an older man and a film director—who discover that they are old classmates. “This is mysterious,” the director remarks, “and fun.” None of the would-be Romeos notice that the lady in question is reading Kafka’s The Metamorphosis.

Hong always has another card up his sleeve, and Yourself and Yours, while not as ingenious as his previous entry Right Now, Wrong Then (2015), is satisfyingly teasing. It also yields one of the most flagrantly self-indulgent trailers I know: faithful to the movie, but frustrating in just the right ways.

Taking it to the streets

When college students en masse join a movement for social change, their positions tend to be vindicated in the long run. In the United States, students were right to support movements against nuclear proliferation, against racial discrimination, against American involvement in Vietnam, for women’s liberation and LGBT rights, against the invasion of Iraq, and, right here in Wisconsin, against Republican union-busting and voter suppression. The same pattern can be observed around the world, in student protests in Europe, South America, and Asia. Elders deride students as naïve, but more often than not, student activists critical of the status quo get principled politics right.

Why? I suspect several causes, including the fact that many (not all) students are reading, thinking, and learning while the general populace trudges through the dull compulsion of everyday labor. College flings together students from many backgrounds and may open eyes about how other people live. (Right-wingers worry too much about liberal professors indoctrinating students. In my experience, students are more influenced by their peers than by the likes of me.) And of course the flexible scheduling of college days allows motivated students the time to engage in political action.

Whatever the causes, it’s no surprise that in Hong Kong, the street protests running from September through December of 2014 were launched by young people. In August the mainland’s Communist Party decreed that instead of direct election of the territory’s Chief Executive, candidates would be chosen by a nominating committee comprised of businessmen and politicians sympathetic to Beijing. In effect, this guaranteed a puppet leader of the type all too familiar in the territory. Students responded by organizing actions similar to the Occupy movement in America. With surprising speed, civil disobedience and sit-down occupation spread through downtown areas of Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula.

Hong Kongers were long considered indifferent to politics, only concerned with scrambling to get ahead and make money. But the world had to notice when tens of thousands of students and ordinary men and women built vast encampments in the streets in front of chic shops and noodle restaurants. Wearing yellow ribbons and hard-hats, and armed with umbrellas to protect them against sun, rain, and tear gas, they were apparently ready for a long stay.

This epochal event in Hong Kong history is documented in Yellowing, a new film by Chan Tse Woon. It was made under the auspices of Ying e chi, a filmmaking collective that has been working since the propitious year 1997, when the British turned the territory over to the People’s Republic. Although framed as a diary, it’s basically a cinéma vérité account of moments and vignettes of the Umbrella Revolution. The voice-over narration is keenly personal, beginning with home-movie footage of Chan’s childhood and youth, interrupted by his memory of repeated promises that democracy would soon arrive.

Loosely organized, Yellowing offers no systematic chronology of events à la a PBS program. It’s defiantly local, a snapshot album for Hong Kongers who will recognize each phase of the movement. At the start, some gorgeous nighttime cityscapes are shattered by confrontations with police (“Police, retreat,” the students chant) and conversations with student organizers in their down time. In the two hours that follow, we spend a lot of that time with young people like the ceaselessly beaming Rachel, who’s now considering becoming a civil rights lawyer. We see one boy passing out wristbands reading, They can’t kill us all.

Students set up tents, squat in pounding rain, organize English classes, and run supply chains across the vast areas of occupation. There are clashes with police and civilians. (“Your flesh and blood belongs to your family,” a man charges.) Chan’s camera captures, helter-skelter, assaults from cops and street gangs. There are camera duels, with police filming demonstrators while demonstrators film police. Chan’s voice-over says that he thought his camera would protect him, but he still gets punched in the face. The occupiers practice tactical evasion and passive resistance, but there’s no effort to heroicize them. Many are crying as police lead them away.

Despite the almost casual presentation, you realize how much these kids are risking. Many are poor, some are trying to hang onto a job, and nearly all realize that this will change their lives. “Even if we lose this fight, we’ll lose together.” As for the angry citizens wearing blue ribbons declaring support for authorities, the students are sympathetic: “Don’t you think they need democracy too?”

The film circles back to the opening, with Daddy-cam shots of children. We hear Rachel writing in reply to a professor who had urged the students to give way for the sake of “security,” and to stop being tools of “foreign subversion.” The film lingers on her cheerful, polite suggestion that Mainland domination has replaced British colonialism, and that the children of the future deserve better.

Most of our politicians and all of our plutocrats will never know the sort of courage that these young people displayed with modest, good-humored tenacity. Unarmed—unlike the Y’all Queda fraidycats who occupied our Oregon wildlife refuge—these unprepossessing kids stood a very good chance of being brutalized by a government not known for recognizing the niceties of due process. You feel proud of the young people of Hong Kong while watching this heartbreaking, hopeful film. As often happens, the students were both righteous and right.

Not hope, fear

Ying e chi has often worked with theatres to show independent films, but Yellowing has been denied a theatrical release. Instead, Variety reports, producer Vincent Chui has arranged for guerrilla screenings. Five ticketed shows were held at the Hong Kong Film Archive, in order to qualify for this year’s Hong Kong Film Awards.

The resistance to Yellowing doubtless owes a lot to the controversy surrounding another film, Ten Years (2015). It won astonishing success in local theatres. According to Maggie Lee in Variety, it cost only US$65,000 but earned nearly $800,000 before Beijing realized how subversive it was and blasted it as a “thought virus.” Ten Years was nominated for a Hong Kong Film Award, which made the PRC cancel television coverage of the ceremony. When the film won the Best Picture prize, shock waves went through the film community, and it was denounced by producers and executives. It was soon cast out of theatres, but screenings continued in community centers, churches, and outdoor venues. It’s slated for a DVD release soon.

Ten Years consists of five shorts linked by the premise of local life in 2025. In its dystopian portrayal of Mainland domination of Hong Kong, it’s a fairly direct outgrowth of the Umbrella Revolution. But if Yellowing documents the movement’s hope, this film exposes, as many commentators have noted, fear.

One episode, “Extras,” dramatizes behind-the-scenes scenes political machinations as a sort of noir comedy. Two hapless thugs are hired to stage an assassination attempt that will arouse public support for a new security law. While the men rehearse their gun choreography, the puppeteers debate whether killing or wounding the targets would play better in the media.

Other episodes are more concerned with the cultural impact of Beijing’s dominance of local life. “Season of the End” presents scientists searching rubble for signs of now-vanished Hong Kong life, shot in ominously clinical detail. “Dialect” presumes that Mandarin is becoming the official language of the territory, and we see a taxi driver struggling to cast off his Cantonese. “Local Egg” also centers on language. Here a shopkeeper is forbidden to use the word “local” because it suggests those political factions struggling to keep Hong Kong distinct, or maybe pushing it to become independent. In an echo of the Cultural Revolution, this episode shows schoolkids in uniform arriving with iPads to check shops’ compliance with the list of forbidden words and retail items.

The most emotionally wrenching episode, “Self-Immolator,” is a pseudo-documentary. Startling scorch-marks on the sidewalk are the traces of someone who burned to death in protest of government oppression. Through talking heads, a collage of demonstration footage, and some investigation, the film traces how a young man’s hunger strike led to the mysterious self-immolation. Several candidates for the self-sacrifice are canvassed before, in a break with the documentary frame, the protest suicide is shown. In the conclusion, an umbrella is seen aflame, perhaps forming a requiem for the 2014 protests.

Ten Years is a good example of how a film can have social importance because of the moment at which it emerges. Along with Yellowing, it will be a lasting memorial to the struggles of Hong Kong people to introduce democracy to China.

Thanks to Tony and Shelly for all their work in setting up these screenings. In addition, Kristin and I are grateful to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and Jennie Lee Craig and their colleagues for making our VIFF visit so enjoyable and enlightening. Special thanks to Tallulah for cheerfulness and Lillooet for the waffles.

Thanks to our regular attendance at VIFF, we’ve discussed many of Hong Sangsoo’s films; see the director category.

The development of the Umbrella Revolution is traced in this long New York Times story. Last August, accused student leaders got surprisingly light sentences. Some of the “localists” and Occupiers won places in the Legco elections and are expected to make waves.

Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer.