Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

More from VIFF 2016

The Death of Louis XIV (Albert Serra, 2016).

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended yesterday, but the films and the pleasures they yielded linger on. Our first two entries are by Kristin, the last two by David.

Smog over Tehran

Iranian film and television director Behnam Behzadi is not well-known outside his native country. Inversion, which was shown in the Un Certain Regard section of Cannes this year, suggests that he deserves to have more international exposure for his work.

The title refers to the meteorological phenomenon that can cause dense pollution to form at ground level. The film opens with shots of Tehran streets seen dimly through a thick haze. The pollution has a causal role to play, since the heroine’s elderly mother ends up in a hospital as a result of breathing problems. More metaphorically, however, the title refers to a sudden reversal in Niloofar’s situation.

Initially she seems to be in a relatively strong position for a Iranian woman. Still unmarried in her 30s, she runs a small, prosperous garments factory and begins to date an amiable man whom she clearly likes. Her mother’s sudden health crisis, however, leads a doctor to insist that she be moved to the healthier northern part of the country, where Niloofar’s sister and brother-in-law happen to own a small villa. Niloofar, with no spouse or children, is pushed by the couple and her brother into agreeing to go along and take care of her mother. She hopes to keep the factory going, but the brother selfishly rents out the premises to pay off his own debts. Niloofar resists going with her mother, but as her siblings ignore her wishes and she discovers that the man she may be considering marrying has kept an unpleasant secret from her, she realizes how little power she has over her own life.

As in Farhadi’s films, a seemingly ordinary situation suddenly deteriorates from a simple cause. But Farhadi tends to gain complexity by avoiding making his characters into villains. In his films, as in Renoir’s, “everyone has his reasons.” In Inversion, however, the brother is straightforwardly in the wrong, refusing to consider Niloofar’s desires and even threatening her with violence during one argument. Overall the film is entertaining, with Niloofar an engaging figure who gives an insight into the situation of women in contemporary Iran.

Mistakes were made

Asghar Farhadi is best known for A Separation (2011), the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film. His earlier masterpieces, About Elly (2009) and my own favorite, Fireworks Wednesday (2006), are slowly coming to be known in the West, largely via home video. After the slightly disappointing The Past (2013), Farhadi is back on track with The Salesman.

The film opens with a tense, dramatic scene in which a Tehran apartment building threatens to collapse and its inhabitants frantically struggle to evacuate. The result is that the central characters, Emad and his wife Rana, must quickly find a temporary apartment (see bottom) while they also prepare to star in a production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

They seem to be coping until Rana mistakenly opens the door of their new apartment, assuming that her husband has come home. The shot holds on the door, standing ajar, as Rana moves off to take a shower and the scene ends. Later we learn that an unknown assailant has entered the apartment. Whether he raped Rana or simply startled her so that she fell and cut herself on broken glass is never revealed, but she is traumatized and unable to proceed, either with her everyday life or her role as Linda Loman in the play. Emad tries to be supportive, but he becomes obsessed with tracking down the intruder.

The mystery gradually unravels as the shady background of the apartment’s former tenant emerges, and revelation of the identity of the intruder undermines the question of revenge. As in Farhadi’s other films, characters’ mistakes, honest or otherwise, compound each other. Ultimately, absolute blame is hard to assign.

The Salesman won two prizes at Cannes: best screenplay for Farhadi and best actor for Shahab Hosseini as Emad. Amazon Studios and Cohen Media will release it in the US on 9 December.

The King is (nearly) dead

Early on in Roberto Rossellini’s Taking of Power by Louis XIV (1966), we find Cardinal Mazarin on his deathbed. Mazarin’s doctors decide to bleed him; a priest advises him on the disposal of his wealth; finance minister Colbert briefs him on intrigues at the king’s court. The shots are lengthy, following the men around the chamber.

This remarkably deliberate sequence was considered quite striking at the time. In a story centered on Louis XIV, Rossellini devotes thirteen minutes to Mazarin. His impending death creates exposition about the ensuing power struggles and initiates a somber pace rather different from that of the standard historical film. The scene also reminds us that historical events have a tangibly material side, as when doctors confer gravely over the stools in His Eminence’s chamber pot.

Rossellini, who’s interested in the tactics by which Louis tames the nobility, doesn’t show us the King’s final hours. That morbid task is taken up by Albert Serra’s The Death of Louis XIV. Unlike Rossellini’s film, which is filmed in radiant high-key and shows sumptuous detail of fabrics and flooring, Serra’s treatment relies on chiaroscuro, with shadow areas broken by trembling candlelight. And while Rossellini’s PanCinor lens swivels and zooms around these apartments, Serra cuts among close views of faces, hands, and a steadily blackening gangrenous royal foot.

In the process Serra expands the physicality of the Mazarin sequence to the length of an entire film. Louis seems to linger for days, but we’re given no distinct sense of how much time passes; in only two shots do we glimpse the outdoors, in bleary light that might be dawn, drab afternoon, or dusk. The time is filled out by court rituals, such as the King’s doffing his hat to his entourage, and by the steady decline of his powers. He can’t swallow food and can barely take water or wine. Through it all, Louis feebly issues his final orders about matters of state and the disposition of his body. A long scene of the last rites is punctuated by a barely discernible fart. This is a movie centrally about a degenerating body.

Even more than Rossellini did, Serra probes the shaky state of medical science of the time. (Louis died in 1715, just as the Enlightenment was beginning.) When Louis’s leg contracts gangrene, the learned doctors debate whether to amputate it. A quack shows up with an elixir made of bull sperm and other recherché ingredients. At the end, the principal physician takes the blame for the king’s death and makes a remarkable apology directly to the camera. Before that, though, Serra has given us a three-minute shot of His Highness reproachfully staring at us (up top) while we hear a Kyrie Eleison somewhere offscreen. Another echo of film history: Louis is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who looked out apprehensively at us many years ago, in the seashore ending of The 400 Blows. It’s glib to say that cinema films death at work, but here the cliché gains some meaning.

Master of the weepie

Is any filmmaker more unfairly taken for granted than Pedro Almodóvar? For over thirty years, he has created sparkling, handsome entertainments that combine cinematic intelligence with outrageous eroticism and insidious emotional punch. His films revel in plot complications and edgy humor. Along the way he effortlessly deploys the techniques that make modern cinema modern, from flashbacks and voice-overs to subjective sequences and abrupt replays that fill in gaps.

He makes it all look easy, and gorgeous. After the drab grays and browns of Hollywood fare, what a pleasure to see a film packed with saturated primaries and bold designs. He proves that you can go as dark as you like in plotting and still make things look delightful.

His characters are clothes horses, I grant you, but not the least of his debts to Old Hollywood is the belief that we want to see presentable people in pretty costumes and settings. The world is ugly enough, he seems to say; why add to it? Seeing The Girl on the Train reminded me how glum American movies are determined to look. An Almodóvar apple looks good enough to eat, and a housekeeper’s roseate apron seems the height of chic. In this world, even refrigerator magnets evoke a Calder mobile.

These elegantly voluptuous tales make unabashed appeal to Hollywood genres: the screwball comedy (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, I’m So Excited), the illicit romance (Law of Desire, The Flower of My Secret), the twisty thriller (Live Flesh, The Skin I Live In), even the ghost story (Volver), and above all the melodrama—medical (Talk to Her) and maternal (High Heels, All about My Mother). He rolls Lubitsch, Sirk, and Siodmak into a nifty package, tied up with a ribbon bow of pansexuality.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

It’s all about guilt, passed from husband to wife and mistress and then to daughter and even daughter’s pal, with the obligatory recriminations and tearful confessions. The plot is continually surprising, yet every scene snicks into place. Neat parallels among couples develop quietly, and tiny hints planted in the beginning pay off. As usual with Almodóvar, the opening credits guarantee that you’re in assured hands. They also tease us with motifs. Here the film’s dual structure (two phases of life, two actresses) is suggested through lemon-yellow letters sliding into alignment.

The two women on my left started crying halfway through the movie. I tell you, this director is a credit to the species.

Special thanks to Michael Barker and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Classics. Sony will release Julieta in the US on 21 December.

We have earlier entries on Farhadi’s About Elly, on A Separation, and on The Past. We discuss Serra’s ingratiating Birdsong here, and Almodóvar’s cunning The Skin I Live In here.

The Salesman.

Refutations of the death of cinema, courtesy the VIFF

Maliglutit (Searchers)

Kristin here:

About three weeks ago David pointed out that the “death of cinema” being bewailed by many critics and pundits was based largely on the disappointments of the summer of Hollywood blockbusters. Taking a larger perspective, the cinema looks to be thriving. Herewith some further evidence as we continue to enjoy the rich schedule of screenings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some of these films are good, some very good, some perhaps great and destined to be watched for decades to come.

Maliglutit (Searchers)

In 2001 the first Inuit-made feature film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner won the Golden Camera at Cannes. Admirers of it, among whom we count ourselves, have wondered whether there would ever be a follow-up. Since Antanarjuat, director Zacharias Kunuk has had an active career in documentaries. Now, however, he has returned with a second fiction feature, Maliglutit (Searchers).

The title proclaims the film’s inspiration: John Ford’s The Searchers. Kunuk wanted to make a western, but one “made entirely the Inuit way.”

From the start, I resolved to anchor the production in my home community of Igloolik. It was important to get the faces right. I brought on Natar Ungalaaq, who played the lead in “Atanarjuat – The Fast Runner,” as co‐director to work with the actors preparing their performances and to mentor a new generation of Inuit filmmakers. Our cast and crew included regular collaborators, but also a number of new people in training.

Igloolik is a small island in the Northwestern Passages, far to the north in Canada. It’s population is about 2000. An extraordinary place for such important films to come from.

Maliglutit can hardly be said to be a remake of Ford’s film. Its borrowing from The Searchers is solely the kidnap plot. The hero is Kuanana, whose wife and daughter are carried off on dogsleds by four members of a neighboring tribe, led by Kupak. Kuanana and his son give chase. Unlike in The Searchers, there is no conflict between the older and younger men. Unlike Ethan Edwards, who is revealed to be hunting down the tribe who kidnapped Debbie in order to perform a sort of honor-killing, Kuanana simply wants the women back. The psychological complexities of The Searchers are replaced by a focus on the details of Inuit life in 1913 (an era in which firearms were starting to replace traditional weapons, above) and the frightening beauty of the bleak late-winter landscapes through which the chase progresses. The two women resist and seek to escape during the entire chase, and they play an active role in the climactic rescue.

Although virtually all of the crew were also local Inuits, producer and cinematographer Jonathan Frantz, was a crucial figure. He created epic images of the harsh, snowy landscapes during the chase (see top), often shot in the early morning light of March.

Maliglutit seems to have no distributor. Watch for it in other festivals and eventually on home video–though the scale of the compositions really demands a big, big screen.

From a textbook to an upheaval

If women directors are still struggling to establish themselves in Hollywood, they are much in evidence here at Vancouver. Films from a wide variety of countries were helmed by women, including Mia Hansen-Løve (or Mia Hansen Love as she is billed here), who won the Silver Bear award for best director at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Bucharest International Film Festival. (See here for an interview with the director shortly after the Berlin premiere.)

Her Things to Come (L’avenir) well demonstrates her mastery of traditional, skillful filmmaking. Her camera is locked down rather than restlessly roaming, with simple reframes to follow actors’ movements. The compositions are impeccable, the editing clearly planned in advance, and the story told in an unobtrusive, clear fashion.

I found the film appealing partly because it presents that rare thing, a plausible depiction of the life of an academic. The heroine, Nathalie, played in another star turn by Isabelle Huppert, teaches philosophy in a Parisian high school. Her students are obviously sophisticated kids, and she finds fulfillment in her work. Her husband is an intellectual, and they have two children. Her life seems ideal and her future certain. In the course of the film, however, she suffers a series of setbacks.

Amusingly, these are initially signaled by a meeting with editors at the publishing house that has brought out her textbook and will be publishing a collection of essays aimed at classroom use. The editors cheerfully show her some garish designs intended to boost sales. Her husband announces that he’s leaving her for another woman, her mother needs to be institutionalized, and she loses her job.

The future is suddenly turned upside down, and the film depicts Nathalie’s efforts to maintain her usual cool, in-control demeanor while seeking a new path in life. Although the film is quite sympathetic to her, there is considerable humor as well. Entertaining, thought-provoking, and visually lovely.

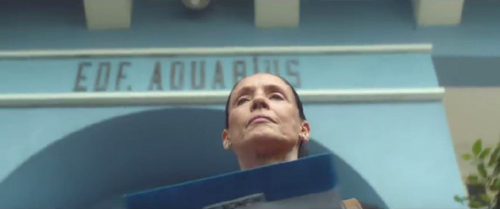

The aging of Aquarius

I was very impressed by Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds, shown at the 2012 VIFF. I have been hoping to see another of his films, and this year the festival presented Aquarius. I can’t say that it was quite as exciting as the earlier film, but it is an admirable and entertaining achievement nonetheless.

Again Filho sets his story in his native city of Recife and again the story revolves around predatory real-estate developers building high-rise residences by buying up and bulldozing beautiful old neighborhoods. The earlier film wove together stories of several families living in such a neighborhood, threatened both by criminals and by the encroachment of modern, soulless towers. Aquarius focuses instead on one wealthy dweller in an otherwise empty apartment building, Aquarius.

The one holdout is Clara, a beautiful, wealthy retired music critic in her 60s, who endures various attempts to drive her to sell her apartment. The unscrupulous developers stage a “party” in the empty apartment above her–an orgy and apparent porn shoot. They burn the resulting filthy mattresses in the communal courtyard. They try to catch her in a legal technicality when she has the façade of the building painted, and things only escalate from there.

The film’s effectiveness depends to a considerable extent upon the riveting central performance by Sonia Braga, best known to English-speaking audiences from her lead role in Dona Flore and Her Two Husbands and Kiss of the Spider Woman. A cancer survivor (as demonstrated by Braga when she bares an apparently real mastectomy scar), Clara commands complete sympathy as she fearlessly stands up to her devious persecutors. Despite her wealth, she is friends with her housekeeper and well aware that a short way down the beach across from her apartment, there is a poor neighborhood even more threatened by the developers than hers is.

As in Neighboring Sounds, Filho includes shots of the nearby high-rise blocks looming over the beautiful older buildings. In my earlier entry, linked above, I quoted an interview where the director said, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.” Here the “wrong” architecture is bland, and the older buildings are photogenic.

Aquarius will begin a New York theatrical run on October 21. (Thanks to Erik Luers for the link!)

A poet for, if not of, the people

Another Latin American film shown at the 2012 VIFF that I wrote about favorably was Pablo Larrain’s No. Now he follows up with Neruda. Here we have another film about a poet, in this case the Nobel-prize-winning Chilean author Pablo Neruda. The film follows the dramatic events in 1948 when Neruda’s Communist activities led to a warrant being issued for his arrest. After living in hiding for some months he fled through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake (above) into Argentina and from there to France.

Not surprisingly, many scenes center around Neruda, played powerfully by Luis Gnecco, an actor more typically associated with comedies. (He played the Ricky Gervais/Steve Carrell role in the Chilean version of The Office.) Equally prominent, however, is the police detective who relentlessly pursues Neruda, Óscar Peluchonneau (Gael García Bernal).

Peluchonneau is at once a real detective, a figure fascinated by his quarry, and perhaps a figment of Neruda’s imagination. In a crucial scene, Peluchonnaeau interrogates Neruda’s endless patient and faithful wife (marvelously portrayed by Mercedes Morán; see bottom), and she informs him that he is a mere supporting character invented by her husband. This seems improbable, since Peluchonneau has important causal effects in the narrative, and indeed, his narrating voice continues throughout the film, filtering much of the story information to us. Still, he plays out his supporting role until the end.

I was startled to discover that he and Neruda are parallel protagonists. My Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) took Amadeus, Desperately Seeking Susan, and The Hunt for Red October as examples of this fairly rare category. Parallel protagonists largely play out their roles independently, but they are aware of each other and fascinated with each other. One may feel inferior and yearn to be like the other. In Neruda, Peluchonneau is clearly fascinated by Neruda and wishes to be like him. He is, however, far less clever and talented. (Jay Weissberg’s Variety review compares him to Inspector Clouseau.) The ending leaves his status as a character quite ambiguous. It’s nice to know that this unusual option is used in art cinema as well as Hollywood films.

There is a distinct touch of magical realism about Neruda, one that fits in well with the art cinema’s departure from mainstream commercial cinema. It does leave you puzzled in a satisfying way.

Quarrels and cabbage rolls

Don’t ask me what the title Sieranevada means. I have no idea what it has to do with anything that happens in Cristi Puiu’s latest feature. If I had to choose a single favorite from the films I’ve seen so far at the festival, it would be a hard choice between Sieranevada and A Quiet Passion. I have to say, though, that Sieranevada is much funnier, though it took me longer than it should have to figure out that it’s a comedy. Watching the lengthy opening shot, which largely involves the main character’s car being double parked and blocking a DHL truck, I did quickly realize that I was seeing a terrific film.

It is something of a network narrative, based on the familiar situation of a family gathering that exposes long-simmering problems and tensions. (Other examples are Altman’s The Wedding and Vinterberg’s The Celebration.) If we had to pick a central character, it would probably be the medical professional Lary, because we enter and leave the central space when he does, we learn the most about him, and we react much as he does to the amusing twists of action. Still, other family members carry a good deal of the film’s running time, and by the end we observe him with a cooler detachment when his own secrets are revealed.

The main locale is the apartment where Lary’s large family is commemorating his father’s recent death. The apartment has several rooms, all of which are fairly small for the number of people milling about. It’s evidently a set, but one which conveys an entirely convincing sense of seeing an actual cramped apartment.

The party is planned to culminate in a substantial dinner. We see the women of the family cooking, setting the long table, inexplicably taking away the unused dishes and utensils, and assembling plates of food wrapped in plastic (above), to be distributed to the neighbors. Few films have made food look so unappetizing. Mainly, though, these people bicker. The party portion of this 173-minute film occupies about 150 minutes, shot in nearly continuous time.

Puiu handles the whole thing in a virtuoso staging of multiple actions going on in different rooms, with the camera often only glimpsing what one group is doing before a door is closed and the camera moves on to catch another group in a another space. Often the camera pans with one character only to change direction as it catches sight of another, as if it continuously seeks out the most interesting bits of action in this densely populated space. Characters air their obsessions: one cousin is a 9/11 conspiracy believer, and an old lady in a white fur hat upsets the others by touting the accomplishments of the Communist past. We hear grievances too, as when the widow’s sister accuses her husband of carrying on an affair with a neighbor.

Scripting the dialogue for this dense weaves of conversations was a considerable accomplishment. Puiu extracts further comedy by putting so much emphasis on the food and then delaying the actual meal for almost the entire duration of the party. First a priest who must perform a memorial ceremony fails to show up, and then a suit which will feature in another ceremony needs emergency alteration when it turns out to be several sizes too large for the hapless young man who must wear it.

In all, despite its three-hour length, Sieranevada is continually entertaining and an extraordinarily assured piece of filmmaking.

U. S. releases: IFC and Sundance Selects have announced Things to Come for 2 December, while Neruda is scheduled to be released for December 16 from The Orchard.

Aquarius was originally expected to be Brazil’s nomination for the best foreign film Oscar, but political controversy has scotched that. There seems to be no prospect of an American theatrical release. Look for it at other festivals and on streaming. So far, Sieranevada seems not to have secured U. S. distribution, but if it does materialize, seek it out in any way you can. It is Romania’s candidate for this year’s foreign-language Academy Award. It would be a well-deserved miracle if it even made it onto the final list of five.

More recent American examples of parallel-protagonist film are Julie & Julia, discussed here, and Public Enemies and Inglourious Basterds, considered here. The first entry also considers an older example, Enchantment (1948).

Neruda (2016).

Poets’ summer: PATERSON, A QUIET PASSION

A Quiet Passion (Terence Davies, 2016).

So I write—Poets—All—

Their Summer—lasts a Solid Year—

They can afford a Sun

The East—would deem extravagant—

Emily Dickinson, “I Reckon–when I count it all,” no. 569

DB here:

From the Vancouver International Film Festival, I write on two new films you should see as soon as you can.

How to make a film respecting the power of poetry? More basically: What is that power? Does it lie in the fact that poetry can be a part of ordinary life? This seems to me the angle taken in Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson. Or does poetry’s power arise as an alternative to mundane intercourse, a realm in which we test thoughts and feelings beyond the flow of daily life? I think this is the angle taken in Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion.

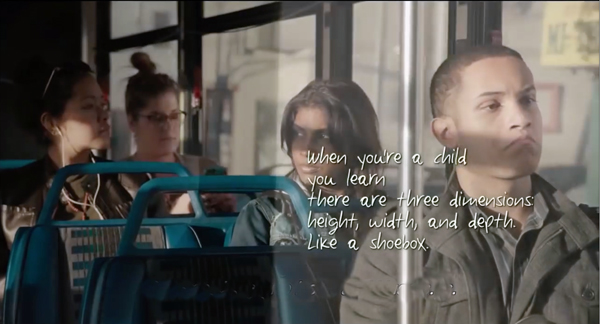

The secret notebook

Paterson drives a bus in Paterson. The bus’s destination display bears not a street name but rather the word “Paterson.” Such playful quirks, long a part of the American indie game, is as inoffensive as the film’s title (Paterson, of course). The milieu looks prosaic enough, with quasi-documentary shots of streets and the Great Falls. But Paterson owns a bungalow on a bus-driver’s salary, catches a 1930s horror film at a local theatre, and drops in at a saloon where a barkeep named Doc plays chess with himself. The town has more than its share of twins too.

In this slightly off-track version of a city, the protagonist’s Iranian-American wife Laura paints fabrics, bakes designer cupcakes, and wants to be a country singer. Meanwhile, Paterson has creative impulses of his own. He writes poetry.

Paterson is a quiet, genial fellow to whom you’d happily entrust your morning commute. His poems (written by New York School poet Ron Padgett) are conversational; the first one we hear begins: “We have plenty of matches in our house.” The poems are given their force by their homely details and the repetition of simple declarative phrases.

Repetition is built into the film’s block construction: A Week in the Life. Waking up, having breakfast, walking to the bus terminal, jotting down some verse before beginning his routes, lunch and more jotting, walking home, eating dinner, and visiting the bar—Paterson ‘s routines create a rhythmic matrix that we quickly learn. That the film’s structure is built around work routines makes sense. In America, a poet might be your bus driver, your doctor (William Carlos Williams), your insurance executive (Wallace Stevens), the farmer down the road (Robert Frost), or your teacher in business school (Marianne Moore).

As for poetic texture, the routines get treated in small-scale variations. Take the opening bed shot, an overhead view of the couple that announces a new day. One morning Laura isn’t there. Sometimes we don’t get a shot of Paterson checking his wristwatch. The weekend mornings lack the daily written title that the workdays get. A poetic principle of verse and refrain gets built into the film’s structure.

Finer-grain texture comes in the recitation of the verses as Paterson writes them into his scruffy notebook. We see the lines form on the surface of the screen, in freehand script, while montages of driving surge underneath them–as if these were coming to life in the course of the day. The fate of the secret notebook is probably the biggest dramatic twist in the film, but even that becomes part of a larger pattern after a melancholy Sunday walk.

And drama? There are moments of tension. Paterson is unenthusiastic about Laura’s buying a guitar, and an habitué of the bar seems to create a life-or-death crisis. Yet these and other problems slide away quickly. When Saturday night comes around, a kind of climax occurs. It tails off, subsumed in the playing out of motifs that were installed early on—rhymes, we might say.

As you’d expect in a film living under the aegis of Williams (author, of course, of Paterson the book of verse), it’s all about the discrimination of detail. “No ideas but in things” is the motto. The emblem becomes the Ohio Blue Tip Matches described in Padgett’s poem and shown to us in close-up. Laura reveals her poetic acumen when she asks if Paterson’s verse mentions the megaphone skew of the label’s lettering.

Paterson may write alongside a waterfall like a classic poet inspired by nature’s sublimity. But in tuning his ear to his passengers’ conversations and by finding epiphanies in mass-manufactured objects, he’s in the American grain.

Night thoughts

Paterson is so unassuming in his creativity that his film might have been called A Quiet Passion. That, though, is the title of Terence Davies’ tribute to Emily Dickinson. But not much about her is presented as quiet. The film starts with the tart young Emily declining to accept a place in Mt. Holyoke’s pious “ark of safety.” She prefers the soaring rapture of Bellini’s “Come per me sereno,” a bride’s thank-you to guests at her wedding. While her family listens politely in their concert-theatre box, she sways in sympathy with the singer. The scene seals her pledge to art.

Any biopic of the Belle of Amherst faces the problem of characterizing her through talk and action. One option is to make her meek and introspective. Another is to make her conversation as diffuse, oblique, and staccato as her verse. Davies has boldly tried another tack. He has made her one of a trio of eloquent women who swap epigrams as swiftly as if they were in an opera or an Oscar Wilde play. Davies seems to be suggesting that worldly (and wordy) banter with her kindly sister Lavinia and racier friend Miss Buffam gave Emily a sense of the blunt force of language.

Paterson is laconic and ruminative, like his verses, but Emily is a parlor dialectician. She hammers fierce comebacks at her father, at her brother (especially when he takes a mistress), and even at the devoted Vinnie. What authority she gains in her closed society emerges mostly from her wit and tongue. (Though she can calmly smash a plate too.) At the same time, Emily knows her words can wound. She’s miserable after snapping at the family servants, and after a volatile exchange with Vinnie she despairs of ever being a good person.

Here is a woman who feels the power and pain of language. Once we understand that, we’re better prepared to understand the inward turn of her verse. Unlike her dueling conversations, her poems are skewed and slanted, with unexpected jumps at every line, or dash. They twist nursery-rhyme cadences and simple vocabulary into Donne-like knots of phrasing. The film’s voice-over recitations make the verse even more elusive than on the page, but I don’t know how else Davies could have handled them. Even showing the lines as they emerge, as Paterson does with superimposed writing, wouldn’t fully satisfy. We need time to ponder the impacted syntax on display. I suspect that instead of trying to translate the perplexing force of Dickinson’s verse, Davies’ film exists as a parallel text, a supplement urging viewers to return to the poems after witnessing Emily’s socializing and suffering.

Familiar Davies themes emerge. Fiery spirituality clashes with hypocritical churchifying; family ties are fulfilling but also suffocating; a single room can enclose peace or stabbing pain. There’s the power of women’s friendships, alliances against a world bent on cutting them down. Davies reminds us that “women’s art” often involves handicraft. Emily is not only writer but book-maker, trimming and stitching little pages together into secular devotionals. These mini-books recall and mock those pious guides for meditation that could be tucked into purses and waistcoats.

Paterson writes in the daytime, while waiting to pull the bus out of the garage or on his lunch hour or even while driving. Emily, once her father gives his permission, writes from 3 AM into the morning. Accordingly, the bus driver’s poems, like those of Williams, have the evenly-lit clarity, if not the compression, of a haiku, while Emily’s verses, haltingly phrased, move in a hallucinatory blur. Jarmusch’s no-fuss staging and editing suit the unassertive texture of the verse and the driver’s days, while Davies, himself something of a chamber artist and a master of the musicalized image, scans his parlor tableaux with lush gravity.

Two films, each one both light and grave, adroit and solemn, though in different registers. Whatever cinematic poetry is, they aspire to it.

Michael Koresky has a superb discussion of Paterson at Reverse Shot, the Museum of the Moving Image site.

Note for the theoretically inclined: Paterson‘s structured routines and substitution-slots interestingly conform to Roman Jakobson’s dictum that the poetic function consists of the projection of the paradigmatic axis of language (alternative lexical items) onto the syntagmatic axis (the linear flow) of a text. See his “Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics.”

Another entry on this site considers Davies’ Sunset Song and his other films. As Moonrise Kingdom is one of our blog’s favorite recent films, it’s a pleasure to glimpse Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward as kids bringing anarchy to Paterson, N. J.

Paterson (Jim Jarmusch, 2016).

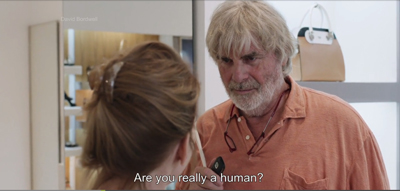

TONI ERDMANN, GRADUATION: Mediums, well-done

Graduation (Cristian Mungiu, 2016).

DB here:

More from this year’s Vancouver Film Fest, abundant as ever (over 200 features, over 300 films in all).

Comedy, Chaplin supposedly said, is life in long-shot, while tragedy is life in close-up. This is questionable on its face, but put that aside. What about medium shots? Maybe they’re either comic or tragic? Or maybe just neutral? Any shot framing the body from, say, the waist up to the head is the workhorse of most film traditions, and it’s ready to be recruited for almost any purpose.

I was led to think about this handy tool when watching two strong and enjoyable films, Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation and Maren Ade’s Tony Erdmann. Both directors made some similar artistic choices, such as that slightly swaying handheld framing that seems de rigueur in many films nowadays–the “free camera,” as the Danes call it. But the two films show different ways of exploiting the medium-shot of people talking. The differences, I think, depend on both genre factors and one crucially diverging choice.

Screwball comedy with a German accent

Toni Erdmann updates screwball comedy: a mischievous madcap disrupts the staid life of an uptight character s/he loves. In classic Hollywood the madcap might be a wild woman (Bringing Up Baby) or a free-spirited man (Holiday), with romantic union the result. The variation here is that the madcap is a father. Winfried tries through pranks and impersonation to loosen up his rigid daughter Ines, who’s striving to be a cool corporate barracuda.

The plot is a series of encounters in Ines’ high-stress professional life. Her rounds of meetings and cocktail parties are constantly invaded by the bulky Winfried. Sometimes he’s his unkempt self (often adorned with splayed monster teeth), sometimes he’s a fake businessman/diplomat named Toni Erdmann. When father shows up, she’s mortified. She resorts to the classic strategies of the screwball target: flight, pretending not to know him, and desperately going along with the masquerade in hope that it will pass. Finally Winfried breaks down her defenses, and we get the obligatory scenes when the by-the-book character finally lets loose (here, through a heartfelt song and later by a creative effort at party hostessing).

The premise of screwball is a bit of a Jonsonian power trip. We’re asked to sympathize with people who have enough leisure and money to punk everyone around them. The cruelty of the put-on, with trusting characters gulled by free spirits, is built into the genre. In Toni Erdmann we have to be ready to accept not only the deflation of a CEO, which is always fun, but also the terrorization of working stiffs like delivery men and mechanics. To the film’s credit, there is a moment when Winfried learns the price that others must pay for a retiree’s cute mischief. Along the way is some sharp satire on corporate predation and its fashions in “coaching” and “team-building.”

All this is played out in good old medium shots. And those in turn are embedded in good old shot/ reverse-shot.

Toni Erdmann relies on shot/reverse-shot technique primarily, I think, because of the need to show reaction shots. A good part of comedy is reaction, and camera ubiquity allows us to watch the gag and the payoff in a tick-tock editing rhythm. Ade can time people’s responses to Winfried’s sinister leer in ways that maximize the laugh.

Shot/ reverse-shot has of course long been a mainstay of classical Hollywood continuity style, partly because it mimics the flow of turn-taking in conversation. Like side-participants in a real-life situation, we shift our attention from speaker to speaker, thanks to the cuts.

Over-the-shoulder framings help anchor us in the space of the scene, so we always know where we are.

Assisting that sense of stability is the so-called 180-degree system of staging, shooting, and cutting. This keeps all the eyelines, postures, and backgrounds fairly consistent. At several points, though, Ade’s reverse angles “break the line,” shifting us across the axis of action. This creates what’s been called “200-degree-plus” staging and shooting.

Fortunately, our pragmatic sense of who’s talking to (or looking at) whom overrides the slight jump. The shift can be smoothed if there’s a strong cue–as here, when Winfried turns his head from the courier on his doorstep.

When you have several characters present, and you’re willing to break the 180-degree line in your reverse shots, you can cheat positions from shot to shot in remarkable ways. A cut can magically delete a character for the sake of emphasizing another one’s reaction.

For example, at a fancy party, Winfried-as-Toni approaches a woman and claims he works at the German embassy. The first shot favors the woman, her friend, and a nervous Ines, who tries to pull Toni away.

But when we cut to a reverse of Toni, Ines is no longer beside the blonde woman.

She has been shifted to the left–in fact, moved completely offscreen–in order to supply a clear view of Toni. His sharp glance to the left confirms her position.

Cheating shot/ reverse-shot positions is a common tactic of classic continuity filmmaking, and Ade uses it freely. The more characters who crowd in, the more chance to cheat them. In some shots during the big party, Ines is close beside her boyfriend as her boss greets Toni. But in the 180-degree reverse angles the couple gets spread out, with the man pushed offscreen entirely, before a new setup brings them back–and deletes the boss.

It’s remarkable how little we notice these shot-to-shot disparities as long as positions are grossly consistent, and as long as we’re given other things to pay attention to. (Dan Levin has studied filmic “change blindness” experimentally.)

Throughout, Ade’s cutting and camera placement help us enjoy, moment by moment, the shocked, bewildered, and bemused responses to Winfried/Toni’s campaign to humanize Ines.

The case of the missing reverse shot

Change the genre from comedy to drama, though, and minimize editing, and you get something else. You get, for instance, Graduation (Bacalaureat).

Mungiu traces a few tense days in the life of Romeo, a provincial doctor living in a bleak housing flat. His daughter is promised a scholarship if she does brilliant exams, but before she can take the first test she’s assaulted and the trauma threatens to wreck her performance. To protect her, Romeo uses his network of friends to arrange for favorable grades. The scheme precipitates crises with the daughter, her boyfriend, Romeo’s wife, his mistress, and a mysterious attacker.

The film is essentially a set of two-handed dialogues, tracing how the pressure on Romeo builds from day to day and hour to hour. These encounters are filmed mostly in medium shots, as in Toni Erdmann, but with one essential difference. The shots are long takes, and they’re kept fairly stationary—that is, no circling or panning of the camera. Handling some scenes in just a single shot, Mungiu often avoids the shot/reverse-shot cutting we see in Ade’s film.

This choice might seem akin to the virtuoso long takes of Iñárritu in Birdman. But as I tried to show back when, Iñárritu’s long takes actually mimic the patterns and effects of shot/reverse-shot editing. In Birdman, we’re denied nothing because the moving camera always picks up the reaction that would normally be captured in a reverse-angle cut. By contrast, Mungiu doesn’t give us the long-take equivalent of continuity editing; he denies us reaction shots quite stringently.

In The Graduation, characters tend to interact in in lengthy profiled two-shots, not 3/4 reverse angles.

This framing gives us some access to the characters’ emotions. It’s worth mentioning, though, that profile shots aren’t strongly informative about a person’s facial expression. A frown or a smile is more “readable” in the 3/4 framing favored by reverse-angle cuts.

More remarkable, though, are those passages in which Mungiu simply denies us access to Romeo’s facial expressions by pivoting him away from us and denying a reverse shot.

Actors have turned their backs to the audience for a long time in both theatre and film, usually to enhance a gesture, to call attention to another actor, or to delay the revelation of the face. But since the reverse-angle cut is such an ingrained convention, we count on camera ubiquity; we expect to see everything. When characters have their backs to the camera, and the director doesn’t cut to an angle that reveals their reactions, this choice can have powerful narrative effects. It can make the character’s psychology more opaque and mysterious. It can also build suspense as we wait for some clues (in words or gestures) to the character’s response.

The withheld reverse angle, within longish takes, was a prominent tactic in Antonioni’s 1960s style, as in L’Avventura.

Mungiu isn’t quite so flagrant, favoring 3/4 rear view like the over-the-shoulder view of orthodox shot/reverse shots. This will do duty for orthodox POV cutting: We see what Romeo sees but not exactly through his eyes.

The result is to attach us to the protagonist but not in a deeply subjective way, as Hitchcock might with intense optical POV shots. These shots might suggest a perceptual subjectivity–we see what Romeo sees, more or less–we don’t know how he’s reacting. Sometimes, as when he and a colleague inspect an X-ray, we get almost no sense of the reaction, or what they’re reacting to.

In addition, Romeo is a fairly phlegmatic man anyhow; he’s hard to read even facing front.

His failed ambitions and troubled relation to his wife, as well as the mess he’s making of the exam scheme, seem to have given him a fixed, furrowed anxiety. I doubt that even Toni Erdmann could make him smile.

Still, most directors would probably have filmed Romeo driving his daughter to school, from an angle in front of the car, shooting through the windshield. And most directors would have revealed something of his response when, as his scheme unravels, the school principal orders him not to contact him again or come near his house.

Even more striking, at a climactic moment, he’s questioned by two policemen. I don’t have an illustration for you, but we’re perched over his shoulder and watch the two cops–not unsympathetic–explain to him at length the punishment likely headed toward him. We get no chance to see whether his facade cracks even a little. But observing him so often as a solid lump in the foreground or on the edge of the shot gives him, I think, a sort of obdurate resistance that suggests he will resist what’s coming. In these grim circumstances, stubborn stolidity gains a heroic quality.

Other characters, notably his wife and daughter, get framed in ways that allow us to track their emotions. It seems somewhat ironic that the sunniest, most straightforward and untroubled faces we see are those of the class lined up for the graduation picture.

No surprises here. The head-and-shoulders shot gets a lot of its impact from its coordination with other stylistic choices: the decision to cut (or not to cut), the selection of the angle (frontal, or from behind), and the overall tone of the film (grim or light-hearted). There are no general rules. Contra Chaplin, the close-up can be comic, as in Harold Lloyd. The long-shot can be tragic, as in Hou Hsiao-hsien or Edward Yang or Theo Angelopoulos. As with these shot scales, the workhorse medium shot is coordinated with other techniques to achieve its results in different contexts.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Entertainment for their generous help in preparing this entry. Toni Erdmann is scheduled for U. S. release by Sony for 25 December. Graduation is distributed by IFC in the Sundance Selects collection; no U. S. release date yet announced.

I discuss the blend of cinematic convention and social intelligence elicited by shot/reverse-shot techniques in the essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” in Poetics of Cinema, 57-82. On the quick information pickup involved in certain facial views, see Vicki Bruce, Tim Valentine, and Alan Baddeley, “The Basis of the 3/4 View Advantage in Face Recognition,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 109–10; and Robert H. Logie, Alan D. Baddeley, and Muriel M. Woodhead, “Face Recognition, Pose, and Ecological Validity,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 53–69.

On the 200-degree-plus style in modern film and television, see The Way Hollywood Tells It, 177-179. On change blindness, an earlier blog entry is here. Another entry bearing on the matter, also VIFF-inspired, is “Where did the two-shot go? Here.”

The laconic rear-view shot became a common tactic of modernist cinema. For other examples, you can see this entry on Béla Tarr. But Mizoguchi got there quite a bit earlier.

Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016).