Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

A decade at the Vancouver International Film Festival

The Red Turtle (2016).

Kristin here:

Recently this blog passed its tenth anniversary. Our first modest entry, on Christine Vachon’s book A Killer Life, was posted on September 26, 2006. The second was “A film festival for all seasons,” the first of David’s five reports on that year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, where he was a judge in the Dragons and Tigers competition for young Asian directors. Since then we both have come to VIFF nearly every year. Its organizers and staff are always welcoming and we can see lots of films in a relatively relaxed atmosphere free from the red carpets, the markets, and the celebrities that make some of the bigger festivals difficult to navigate. We’re delighted to be back in Vancouver now, reporting on its rich array of offerings for a tenth time.

The Rehearsal

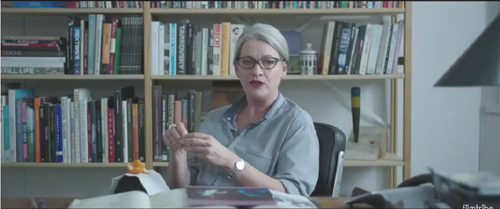

Canadian-born, New Zealand-bred, New York-dwelling director Alison Maclean gives us The Rehearsal (2016), her first feature since her best-known film, Jesus’ Son (1998). In between she has been primarily working in television, including episodes of Sex and the City and The Tudors.

The film begins with an image of an Asian woman in a blonde wig and ultra-high-heel shoes facing directly into the camera and miming a tennis game (see bottom). Such an arresting opening is a wise move, since the film’s early portions are mostly expository. The opening introduces Stanley, a young Maori man who gains acceptance to a high-pressure, prestigious drama school, despite his apparent lack of the necessary talent and drive. Overcoming his initial listlessness, Stanley gradually bonds with his classmates. He also blossoms somewhat under the tough-love approach, sometimes verging on cruelty, that is the policy of Hannah, the demanding head of the school (Kerry Fox, above, best known for playing Janet Frame in An Angel at My Table).

The opening image turns out to be a flashforward to a rehearsal of an original playlet that Stanley and a group of teammates must put on at the end of the school year. For their story they seize upon a current local scandal in which a tennis coach has had an affair with an underage pupil. Stanley has begun dating the girl’s sister Isolde, which gives him knowledge about the situation that the group incorporate into their play. The main suspense arises from Stanley’s failure to tell Isolde what his team is up to, despite the fact that inevitably she will find out. More drama arises from the effects of Hannah’s harsh methods on the students, particularly Stanley’s vulnerable roommate.

The Rehearsal currently has no American distributor but will play on October 5 at the New York Film Festival.

The Confessions (Le Confessioni)

Early in The Confessions a spectacular drone shot follows a moving car from above the treetops. Eventually the car arrives at a driveway crowded with news photographers, and the camera leaves it to reveal a huge modern hotel and then move beyond it over ta body of water. Though not as flashy, the rest of the film has the sort of lush cinematography (above) and rich musical score that are familiar from such other recent prestigious Italian productions as The Great Beauty.

The plot involves a sort of bitter parody of a G8 meeting, with eight representatives of major countries meeting under the guidance of the head of the International Monetary Fund. They are preparing to execute some sinister plan, under the guise of “creative destruction,” that will solve a current international financial crisis in a way that will benefit rich countries at the expense of the poorest ones. Daniel Roché, the head of the IMF, has also invited an Italian monk, Roberto Salus (played by Tony Servillo, so memorable in The Great Beauty and especially Il Divo), to attend.

The reason for Salus’ presence is not clear, though Roché requests him to hear his first confession in twenty years. Roché is soon found dead. It’s apparently a suicide, but some of the finance ministers attending the meeting seemingly try to eliminate Salus by casting him under suspicion of murder. The film turns into a cat-and-mouse game, with each seeking out Salus for devious conversations, punctuated with tantalizing flashbacks that gradually reveal what Roché had revealed during the confession scene.

Although on the surface the film seems to be developing into a thriller, it is too playful to be taken entirely seriously, and the wise, reserved Salus always delivers the final sardonic comic topper in his exchanges with each of the villains. There is even a suggestion of a sort of magical realism at a few points. Ultimately The Confessions is a somewhat uneasy mixture of genres but a highly entertaining one.

The Red Turtle

In the early days of the blog (December 10, 2006), I wrote an entry claiming that in contemporary cinema, animated films are on average more likely to be stylistically superior to live-action ones. Animated films have to be intensively pre-planned, including recording soundtracks in advance. Such careful preparation, which eliminates the easy reliance on “coverage” and limits changes in post-production, imparts a rigor and care that are too often missing in live-action features. Two experiences with animated films here at Vancouver reinforce my point.

David and I agree that The Red Turtle is a standout among the films we’ve seen so far. It’s an animated feature by Michael Dudok de Wit, the Dutch animator who won the animated-short-film Oscar in 2000 for Father and Daughter. The Red Turtle won a Special Jury Prize at Cannes this year. It also has Studio Ghibli’s name attached, which might lead to some raised eyebrows.

Studio Ghibli’s three legendary animators all retired in recent years: Hayao Miyazaki, after The Wind Rises (2013); Isao Takahata, after The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013); and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, after When Marnie Was There (2014). Rumors that the studio would shut down fortunately proved false, despite the fact that its crew of animators was disbanded. The Red Turtle is the first film to bear the Studio Ghibli name since Marnie. The studio, not Dudok de Wit, initiated the project, and perhaps it will henceforth support occasional hand-picked productions like this one.

Though The Red Turtle uses traditional cell animation, it does not particularly imitate the studio’s familiar style Nevertheless, the film is far from being a radical departure from its previous output. For one thing, The Red Turtle is vitally concerned with the depiction of nature. It opens with a storm that drives a single survivor from a shipwreck onto the beach of a small island, uninhabited by humans. His first contact with living things there comes when a curious sand-crab crawls up his pant-leg, and a group of these crabs provides touches of comic relief throughout.

Three times the unnamed man tries to escape aboard bamboo rafts (above), but each time a large red sea turtle destroys his craft (see top) and forces him back to the island. In the story’s first fantastical event, the turtle transforms into a woman, and the two soon fall in love, Adam and Eve in a sparse Garden of Eden. They gain a son, a tsunami introduces a note of threat into the idyllic depiction of nature, and ultimately they face mortality. The simplicity and fantastical elements of the story would be perfectly convincing as a rendition of an existing myth, but the story is completely Dudok de Wit’s invention.

The three human figures are drawn very simply and look like they were rotoscoped, though I can find no confirmation of that online. The depiction of the natural landscape and the creatures that inhabit it are, however, stunningly beautiful. Without attempting a photorealistic look, Dudok de Wit’s team have captured the look and movement of sunlit seawater, the rhythmic rustling of leaves, and even the differences in color between the exposed and the submerged surfaces of woolsack blocks of granite at the ocean’s edge. It is almost as if they have managed to rotoscope all of nature.

The classic films by the main directors at Studio Ghibli are more elaborate and complex than The Red Turtle, but the new film suggests that the studio will maintain its high standards in its future productions.

The Red Turtle was bought by Sony Pictures Classics and is scheduled for a mid-December American release.

Window Horses (The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming)

While The Red Turtle is a high-profile animated film, Window Horses originated as an Indiegogo project. Its success in that campaign led Sandra Oh to back the film, signing signed on as a producer and providing the voice of the film’s heroine. The project gained additional support, including by the National Film Board of Canada. Still, it is likely to remain largely a festival item (it premiered at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival), with only a limited theatrical release in Canada early next year. (Information on that release is not yet available online, but news will presumably be posted on the film’s website.) It exhibits a lively imagination and stylistic sophistication that deserve a wider audience, which with luck it will achieve via streaming.

The story centers on Rosie Ming. With her Chinese mother dead and her father having apparently abandoned his family to return to Iran, she lives in Vancouver with her maternal grandparents. A self-published book of her verses leads to an invitation to a poetry festival in Shiraz. Donning a full chador in the hopes of fitting in, she finds herself surrounded by women wearing simple scarves and vibrant clothing.

The animation itself is colorful, with stylized faces that are vaguely reminiscent of Picasso (as in the tour-bus scene, above). Rosie stands out in her utter simplicity, rendered as a black-clothed stick figure with a round, white face sketched in only by eyes and, when she speaks, a mouth. Recitations of poems are accompanied by scenes of animation is a variety of styles, contributed by such animators as Kevin Langdale, Janet Perlman, Bahram Javaheri, and Jody Kramer.

Overall, it is an engaging and entertaining film, showing how much an independent filmmaker can do with limited means. In that it reminds me of Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues.

Films that have particularly impressed us so far include Pablo Larrain’s Neruda (playing again on October 9), Cristian Mungui’s Graduation (playing again October 5 and 11), and above all Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion (playing again on October 9). We’ll be blogging about these and others over the next several days.

The Rehearsal (2016).

Adieu to Vancouver 2014

Jauja.

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended this past Friday. I had hoped to post a wrap-up entry over the weekend, but illness intervened. Herewith a summary of several films I enjoyed this year.

Too clever by half

Some films are obviously and thoroughly pretentious. This year Field of Dogs (Lech Majewski, 2014) fell into that category. I had had high hopes for it, since I very much liked Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross at the 2011 festival. Unfortunately, it’s a completely different film, overcomplicated and, for me, nearly unwatchable.

Two film, however, suffered from a different problem. They had absorbing stories and interesting stylistic approaches. I enjoyed both very much–except for unwise additions, in each case unnecessary and annoying.

Stations of the Cross (Dietrich Bruggemann, Germany, 2014) revolves around Maria, an adolescent girl raised in a household where a strict, old-fashioned version of Catholicism is practiced. Bruggemann takes the not uncommon approach of filming each scene in one lengthy, and in most cases static, take. In the opening scene, a priest instructs a small class of children about to take First Communion. The camera is placed in a planimetric framing, a technique used in several shots in the film:

As the lesson continues, Maria, seated to the priest’s right, gradually emerges as the student most versed in the topics under discussion. She stays after the others leave and hints to the priest that she wants to sacrifice herself to earn a miracle for her four-year-old brother, who has never spoken. Her belief that she must deny herself virtually all pleasures, comforts, and even necessities, as well as her guilt over the slightest perceived infraction, become increasingly apparent across the narrative. Her arguments with her harsh and inconsistent mother, who dominates the family, reveal her suffering. Despite the static shots, the story is never boring, and a scathing indictment of this brand of religious extremism builds up.

The problem is that Bruggemann inserts chapter titles before each scene/shot, numbered and with the descriptions of the fourteen Stations of the Cross. This inevitably connects Maria’s sufferings to those of Jesus. Each scene contains some parallel, however tenuous, to the station that it is supposed to illustrate. I found this distracting and occasionally ludicrous, as when the title describing Christ’s being stripped of his clothing cuts to a shot of a partially undressed Maria seated on a doctor’s examining table. (Jay Weissberg’s review for Variety sees deliberate humor in the film, but as far as I could see, Bruggemann takes all this as deadly serious.) This could have been an excellent film without the insistence on allegory, but as it is, one must try to ignore the interruptions to focus on the story.

Something rather similar happens in Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, Argentina, 2014). Again there is an absorbing story, though a very different one. In nineteenth-century Patagonia, a Danish engineer is doing surveying work to help a military group determined to wipe out the indigenous population. When his daughter runs off into the forbidding desert with a young soldier, the engineer follows on his own and experiences a series of increasingly disturbing and mystifying incidents, including some that could be classed as magical realism.

This is fascinating stuff, and in the print we saw, the beautifully composed landscape shots (almost the entire film takes place out of doors) were presented in a masked format reminiscent of old lantern slides or stereoscope images (see top, the opening one-shot, long-take scene). Most of the images from this film on the internet are in a more conventional 1:66 ratio, but the masked version seems far superior. One can only hope that the video release preserves it.

It’s a lovely, evocative, disturbing film, but just as we see a shot of the protagonist disappearing into a valley in a bleak landscape of black volcanic rocks, there is a cut to an epilogue set in a beautiful Danish castle. The daughter wakes up and goes for a walk with some dogs. End of film. How this is supposed to relate to the preceding story is a mystery, and one which thoroughly undercuts the tension slowly built up over the course of the Patagonian-set story. The scene of the hero disappearing would have made a fitting ending, leaving the solution to the tale’s mysteries open-ended.

I note from a recent story in Variety that Alonso has been chosen as the second filmmaker to be hosted in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s new “Filmmaker in Residence” program. That’s good news, I think, but I hope Alonso will trust more in his story-telling ability and less in flashy tactics like this pointless epilogue.

Brief notices

One director who displays such trust is Alejandro Fernández Almendras, whose Chilean revenge tale To Kill a Man (2014) is both entertaining and morally and psychologically complex. We are almost entirely confined to the presence and knowledge of Jorge, a forest ranger who has grown accustomed to the casual violence in the neighborhood where he lives. He tries to avoid trouble, but his family is increasingly harassed by Kalule, a loathsome petty gang leader. As Jorge is mugged, his son is shot and then wrongfully imprisoned, and his house pelted with stones and threatening messages, he doggedly insists on going through the police, while his wife becomes increasingly frustrated with their lack of response.

Finally, after Jorge’s daughter is assaulted and nearly raped, he decides to act and sets out to eliminate Kalule. The film then follows his patient, careful planning, culminating in an understated but riveting long take of the truck in which Jorge has his victim trapped as he systematically sets up the mechanics of the killing. The death itself is not shown:

Hitchcock has said that in making Torn Curtain‘s big fight scene in the farmhouse, he wanted to show just how physically difficult it is to kill someone–as opposed to the seemingly effortless killings that fill American genre films. Almendras’ film is almost entirely about how difficult it is in all ways. Jorge takes a long time making his fateful decision, in executing it, in dealing with the body and evidence, and in living with what he has done. Most spectators, attuned to more conventional revenge plots and frustrated by Jorge’s initial resignation in the face of intolerable injustice, are probably cheering him on from an early point in the plot. But, as Almendras thoroughly shows us, it just isn’t that easy.

Charlie’s Country (Rolf De Heer, 2013) also centers very tightly on a protagonist beset by difficulties, but it sets a very different tone. It’s another Australian film focusing on aborigines and their problems under the rule of the white majority. Charlie is a genial elderly man living in impoverished circumstances in a village set aside for aborigines and run by local police. Their laws mystify him. His gun is taken because he cannot afford a license, and when he fashions a spear for hunting for food, it is taken away and destroyed as a dangerous weapon.

His health declines so far that the authorities send him to a hospital in a city far from his home, an apparent signal that he is dying. Instead, he escapes, lives with some street people, and finally makes his way home.

The film is entertaining enough, though it deals with familiar subject matter. It exists, though, primarily as a love letter to David Gulpilil, the most successful Australian aboriginal actor. His first film is also one of his best-known outside Australia, Walkabout, which I saw when it first came out, just after I had gotten my BA and was about to commence film-studies as a graduate student. (It’s a bit disconcerting to watch him playing an old man here and realizing that he is three years younger than me!) Gulpilil turns in an endearing performance that pretty much carries the movie.

I enjoyed and was impressed by Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsky’s Leviathan (2014), though I’m not sure it quite lives up to all the hype following its debut in competition at Cannes, where it won best screenplay. The story centers around the owner of a sprawling, dilapidated garage in a declining fishing port on Russia’s northwestern coast. He struggles to prevent a corrupt local mayor from appropriating his property illegally. (The hypocritical official wants to use the land to build a church to further his own reputation.) At the same time, the protagonist has remarried, and he must deal with his teenage son’s reluctance to accept a young stepmother.

The depiction of modern Russian society in the provinces is a grim one, albeit one displayed in sweeping landscape shots that suggest the waste of this stunning region. Many scenes involve the characters putting away great quantities of vodka. These include a hilarious set-piece in which the family and friends drive into the countryside for a drunken picnic complete with a shooting competition using portraits of historical Soviet leaders as targets.

Leviathan will be released in the USA by Sony Pictures Classics on December 31.

Papusza (Joanna Kos-Kralize and Krzysztof Kralize, 2013) is the second new black-and-white Polish film I’ve seen this year. The first was the much-heralded Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2013), an austere tale of a young woman in the 1960s, about to take her vows as a nun when she learns that she comes from a Jewish family persecuted during World War I. Papusza is a more easily engaging film, with a relatively fast-moving historical drama set among Poland’s Roma (“gypsy”) population.

Papusza centers around Bronislawa Wajs, the first Roma woman to learn to read and write; she became a well-known poet nicknamed Papusza. The film adeptly balances sympathy for the Roma group at the center of the story, the victims of racial prejudice, with a clear-eyed depiction of the less savory aspects of Roma culture. Girls, kept ignorant and oppressed, are married off at a young age. The Roma society practices its own prejudices, rejecting any interactions with people outside their clan and treating non-Roma as fair game to be fleeced at any opportunity.

The lively culture of the Roma and their closeness to nature are shown in impressive landscape scenes, as in shots of the caravans on the move through bucolic countrysides or when the band sets up a camp and market outside a traditional church (below).

As of now there is no indication that the film will receive an American release. The only DVD available seems to be the Polish one, with no optional subtitles. Various small streaming services claim to be offering it, but again, possibly without subtitles and in some cases with timings that don’t correspond to the original 131 minutes.

And so another year at Vancouver has ended. As usual, we are left with the feeling that this event is one of the most pleasant ways to catch up with a huge amount of what is happening in world cinema.

Papusza

Middle-Eastern fare at VIFF

Winter Sleep.

Kristin here:

Iranian cinema moves on

Maybe it’s just the particular selection of Iranian films at this year’s festival, but I sensed a shift from the ones we’ve seen in previous years. Last year I titled one of my entries “Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to Viff.” This year familiar names are missing, including Kiarostami, Panahi, Rasoulof, and Farhadi. (Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s new feature, The President, was at Venice but not here at VIFF.) Moreover, all three of the Iranian fiction features this year depart from some conventions we’ve grown used to in the New Iranian Cinema of the past decades.

Whether A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) is actually an Iranian film is debatable, though it is listed as such in the program. Its director, Ana Lily Amirpour, was raised in England and subsequently moved to the USA, where she studied filmmaking at UCLA. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is her first feature and has American backing (including Elijah Wood as one of several executive directors) and was shot in California. Amirpour is of Iranian descent, and the film is in Farsi, which may be enough to have it considered Iranian.

It’s hard to imagine, however, such a film being made in Iran. It’s a vampire film, taking place in an imaginary town called Bad City, perhaps located in Iran but perhaps not. Its setting look distinctly like the less picturesque parts of the American West:

Amirpour has fashioned a remarkably good pastiche of an American widescreen, black-and-white genre film of the late 1950s or early 1960s, as this image and the one at the bottom of this entry demonstrate. As the Variety review points out, the look is also informed by graphic novels, notably Sin City. Indeed, this summer Amirpour has published a brief graphic novel with the same title as her film; it’s apparently a prequel to the movie’s story. Given that it is labeled #1, the artist presumably envisions a series.

The genre is the vampire film, though this one is hardly conventional. The vampire is the Girl of the title, and the director has taken amusing advantage of the resemblance between her triangular black hijab and the classic floor-length cloak worn by screen vampires, such as that of Bela Lugosi in the 1931 Dracula:

The heroine moves eerily through the streets of the town (see bottom), picking as her victims men who have exploited women. A romance develops between her and a more sensitive young man, clearly modeled on James Dean.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night played at Sundance and has been picked up for American Distribution by Kino Lorber, apparently with an October release planned.

The two other Iranian films are what David has dubbed “network narratives.” One is straightforwardly so, the other far less so.

Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014) in some ways develops on the classic quest narrative of so many Iranian classics since the 1980s, where hero or heroine (often a child) doggedly set out to accomplish something, with the struggle laid out in detail. In Tales the questing characters are multiplied, with their paths crossing and sometime re-crossing.

Unlike in most of the earlier films, these quests don’t always yield results, and hence closure. The characters are mostly involved in seeking help of some sort, sometimes from other people, sometimes from a government institution. The cumulative effect is to suggest a society that has lost the ability or the will to respond, even to desperate pleas.

The film begins with a filmmaker riding in a friend’s cab, shooting the passing cityscape. He immediately drops out of the story, though he will return. Ironically, the story’s action begins with a failed attempt to help someone. The cab driver is hailed by a prostitute with a sick child. Recognizing her as an old friend of his family’s, he buys medicine and a toy for the child, only to find that the woman has disappeared into the night.

Arriving home, he tells his mother of this encounter. We then follow her in a scene in an office building, where she tries to fill out a form complaining about not having received her pension. A gentleman in the corridor helps her, and we follow him into a meeting with a petty bureaucrat who takes calls from his wife and mistress, ignoring what the man is trying to tell him.

A central scene returns to the mother, now on a bus of protestors. The same filmmaker whom we saw at the opening is making a film about their personal plights. We watch through the viewfinder as the mother pleads for help. It’s not clear whom the film is aimed at or who will eventually see it. Later in Tales, the filmmaker remarks that all films eventually get seen, but this seems far too vague to hold out much hope for those caught in a maze of bureaucratic red tape and neglect.

The network structure reportedly resulted from the fact that under the Ahmadinejad regime Bani-Etemad could only get a license to make a series of shorts. Subsequently she was able to weave these together into a feature.

Bani-Etemad, who also produced Tales, is considered Iran’s top female director. Here she brings back some characters from her earlier films, including Dr. Dabiri, from Gilaneh (2005), and Sarah, from Nargess (1992). The VIFF program quotes her as saying, “Tales returns to the characters of my previous films under today’s circumstances.”

Finally there is Fish and Cat (2013), which elicited mostly praising reviews when it debuted in Venice. (For an example, see our friend Alissa Simon’s take on it for Variety.)

Despite running a lengthy 134 minutes, director Shahram Mokri shot the entirety as one lengthy take, without benefit of CGI. A sinister mood is set up immediately when a title hints that it will concern some restaurant owners in a remote district who may have used human flesh in their meat dishes. Two owners of the restaurant are introduced in the opening scene, and we follow them as they set out on a path through the nearby woods, carrying weapons, tools, and a bag soaked in what looks like blood:

The pair chat until their path crosses that of Kazim, a young man participating in an annual kite-flying event to take place by a nearby lake; he’s trying to ditch his clinging father. We follow him to the lake, then leave him to latch onto Parviz, who is trying to organize the young people arriving for the event. And so it goes, until eventually the brief scenes between the people who meet and part begin to repeat, but from a different vantage point. Much of the action involves the camera tracking with the characters from behind, as in the frame above, resulting in an occasional difficulty in identifying whom we’re watching.

The tone remains ominous throughout, with the two thugs and a third accomplice intruding at intervals, perhaps with murderous intentions. There’s also plenty of dark humor as well, and despite the slow unrolling of the action, the film remains absorbing throughout. Some viewers will be tempted to see the film on DVD/BD again, trying to work out the complicated looping chronology of the plot–possibly diagramming it, as the filmmakers presumably had to.

Those who can’t do

We wrote about Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s first feature, Policeman, in our 2011 VIFF report. This year he is back with his second, The Kindergarten Teacher (2014).

The film is a psychological study of young woman, Nira, who is an apparently ordinary and devoted kindergarten teacher. She learns that one of her small charges, Yoav, a shy, uncommunicative five-year-old boy, has an odd habit. Occasionally he begins to pace back and forth, declaring “I have a poem” and then reciting a short poem that would do credit to an adult author.

Nira’s reaction to this apparent prodigy is shifting, occasionally ambiguous, and increasingly disturbing. We are confined almost entirely to what she observes and does, so we get no other view of Yoav except when his nanny and father talk with Nira.

Initially she seems inclined to take advantage of Yoav. We witness her reciting one of his poems as her own at a poetry-writing group that she attends. This premise is soon dropped, however, when Nira takes Yoav under her wing. She favors him over his classmates and encouraging his artistic impulses. Eventually she tries to take control of him, clearly picturing herself as gaining reflected glory from being a mentor to a great artist.

Given the limited point of view, we are encouraged to speculate as to how Yoav comes up with his poems and how far Nira will go in crafting the triumphant public career that she clearly wants for the boy. When she discovers that his boorish, business-minded father has no use for poetry, she increasingly tries to control Yoav, taking him to a public poetry-reading and getting him to recite onstage:

Cumulatively the film traces a slow and disturbing path toward her greater obsession. A subtly presented clue suggests the nature of Yoav’s recitations–to us, that is, if we catch it. Nira misses it, or chooses to ignore it.

Once again in Anatolia

Three years ago we wrote about Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once upon a Time in Anatolia as one of our favorite films of the 2011 VIFF. Now Ceylan is back with another long film, Winter Sleep (2014), and again it stood out among the films we saw this year.

The film was shot in the Cappadocia region of Anatolia in central Turkey. The area is a major tourist attraction, with caves, “fairy chimneys” and other spectacular stone formations, rock-cut chapels, and structures from antiquity.

The protagonist, Aydin, is an ex-theater actor now retired and running a hotel made up partly of rooms cut into the picturesque rock formations. It’s the winter season, with only a Japanese couple and a motorcycle devotee staying at the hotel, and Aydin has plenty of time to write columns for the local paper and bicker with his young wife Nihal and embittered, recently divorced sister Necla:

This time there is no crime investigation or mystery around which the plot centers. Instead the narrative is a character study, played out partly in long conversations between Aydin and the two women. There are also scenes in which Aydin reacts with indifference to the sufferings of his impoverished tenants.

The early part of the film is given over to Aydin, who at first seem mildly sympathetic, brilliant and creative. But as he converses with Necla in a lengthy central scene in his study, his remorselessly sardonic sister picks apart his flaws in a verbal duel between two equally witty characters. Later, Nihal feels beaten down by Aydin’s opposition to her charitable work, the only activity that gives her satisfaction in this isolated life, and she finishes the job of exposing Aydin’s selfishness.

The program notes compare the film to the plays of Chekhov, and there is a definite similarity, both in the conversations and in the contrasts between the wealthy family and the working-class people who resent being dependent upon them. Despite the fact that much of the film consists of long conversation scenes–and runs for 196 minutes–the large, sold-out audience with whom we watched the film were dead silent, clearly captivated by the story. Unlike Chekhov, in the end the film offers a glimmer of hope for the characters.

Ceylan has said that he shot in the distinctive landscapes of Cappadocia only reluctantly:

I actually didn’t want to use it, but I had to. I originally wanted a very simple, plain place, but the film had to be set in a tourist area, and I needed a hotel that is a little isolated, outside of town. Cappadocia was the only place I could find that in the winter time still had tourists.

I was afraid of shooting in Cappadocia because it might have been too beautiful, too interesting. But I didn’t show it too much, I hope.

Ceylan succeeded, I think. There are enough shots of the rock formations to impress us, but they are used sparingly. One might interpret the landscapes as reflections of the characters’ inner turmoil, in much the way that Maurice Stiller and especially Victor Sjöström used Scandinavian landscapes in their classic films of the 1910s and 1920s. (See top, where Aydin pauses to think near some rocky outcroppings.)

It certainly shows enough that Winter Sleep might cause a rise in tourism among art-cinema audiences. One hotel’s blog has already mentioned the film as a way of luring customers.

Winter Sleep won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year and will receive an “awards-season” release in the USA by Adopt Films.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Here be dragons, and tigers

Revivre.

DB here:

My first visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival back in 2005 was at the invitation of Tony Rayns, programmer of the Dragons and Tigers series. That series included both new films by established directors and a batch of first or second features by beginners. Tony asked me to be on the jury for the young D & T award.

I enjoyed working on that jury, which consisted of old friend Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong Film Festival and new friend Gerwin Tamsma of the Rotterdam fest. We gave the prize to Liu Jialin’s Oxhide, and it’s been gratifying to track her career since. In the course of my stay I realized what an excellent festival Vancouver had, not least because of the warmth and enthusiasm of its staff.

My Vancouver experience helped launch this blog, which really got under way during my second visit, in several entries in 2006. That was also the year I met Bong Joon-ho, who was at VIFF with The Host. I kept going back, and Kristin began joining me, so every year we’ve been writing about this admirable event.

During that 2006 festival Tony decided to rearrange his commitment to Dragons and Tigers. He turned the curating of Chinese-language films over to expert programmer Shelly Kraicer, who was living on the mainland and had excellent contacts within China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Now things have changed again. This year the festival accepted fewer beginners’ features and folded them into a broader international competition. One of the Asian films in the collection, Rekorder by Mikhail Red, tied with a French entry, Miss and the Doctors, for the award. In the old days, the winner received a cash prize; alas, that benefit has not been retained, but maybe some far-sighted patron will step forward to give the award a little more heft.

There were fewer D & T titles overall this year, but I still found several of great interest. Herewith some notes on them.

Time, and time again

Revivre.

If your movie is going to include flashbacks, you have a choice among several standard ways of motivating them. You can use the very old device of presenting an investigation or trial, in which the film translates testimony into dramatized scenes. Or you might frame the flashbacks with a scene of a character who thinks back on events in the past. Three of the Dragons and Tigers films used some other common flashback setups, but treated them in fresh ways.

Im Kwon-taek’s Revivre (Hwajang, his 102nd film!) starts with another canonical flashback situation. In fairly washed-out footage a funeral procession crosses the screen. A man at the head of the group looks back and sees a beautiful young woman looking gravely at him. Immediately the film triggers questions: Whose funeral is this? Why is the young woman important?

The rest of the film fills us in via flashbacks,. The protagonist, Oh Sang-moo, is a manager of the advertising section of a cosmetics company. His wife is stricken with a brain tumor and he cares for her as best he can during her years of surgery and recovery. At the same time, he develops a restrained affection for Ms. Choo, an employee in his division. Eventually Oh’s wife dies and there is the lingering possibility of his starting his life afresh with Ms. Choo, whose phantom face we’ve seen in the procession. Threaded through this are the pressures of a business deadline, his need to keep his staff on track, his occasionally fraught relations with his daughter, and his wife’s adamant insistence that after she dies he keep none of her things, not even her beloved dog.

The film scrambles the order of Oh’s experiences. After the funeral, within about five minutes we get a scene of Oh’s wife dying in the hospital, then a scene of his own medical problems, and then the moment that Oh’s wife collapsed in the garden, yielding the first sign of a tumor. The rest of the film gives us incidents from all phases of their last years together, with emphasis on his careful attention to her bodily functions. Although his daughter finds the task repellent, Oh changes his wife’s diapers and cleans her private parts with the same calm professionalism that he brings to the meetings in his company. In all, the non-chronological flashbacks work effectively to show Oh juggling the pressures of business with the demands of his family situation.

What makes Im’s treatment a little unusual is that the flashbacks aren’t presented as Oh’s memories. They are rearranged by the narrational authority of the film itself, rather than by situations that provoke Oh to recall this or that incident. We’re restricted to Oh’s range of knowledge throughout, but that doesn’t draw us closer to him. We have to read his mind through his expressions and his gestures, and these are often severely controlled. A master of the poker face, this executive keeps a polite distance from everyone, including the viewer. Is he one of nature’s stoics? Or is he emotionally detached, attending to his dying wife more out of duty than love?

These questions are partly answered by some brief fantasy scenes in which Oh visualizes Ms. Choo as a romantic partner. She seems to intuit his interest, and responds through small signals. When she starts to reciprocate more explicitly, Revivre returns to its mood of impassive sadness for its final scenes.

Time and freedom

Hong Sangsoo has been playing with time from the start of his career. He has tried replays from different viewpoints (The Power of Kangwon Province, 1998), replays that differ in details (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), odd déjà-vu experiences (Turning Gate, 2002), and all manner of theme-and-variations plotting (as noted on this blog here and here and here). So it’s a bit surprising to find him exhuming the old reliable setup of letters recounting events in the past. Yet here as ever he has a couple of tricks up his sleeve.

Like Im, Hong has scrambled the flashbacks in Hill of Freedom, but he offers a comically exact motivation. Kwon, a young language teacher in Seoul, returns to find a sheaf of letters written to her by a Japanese admirer, Mori. He taught with her at the school two years earlier. He has come to Seoul to reunite with her, and he has left her a letter every day. She starts to read them in the school lobby, and Mori’s voice-over narration establishes the beginning of his story. He tells how he found lodging, left a note at Kwon’s apartment, and paid his first visit to the “Hill of Freedom” café.

So far, 1-2-3 preparation. But when Kwon starts to leave the language institute, she staggers on the staircase, as if stricken, and scatters the letters on the steps. She gathers them back up in random order. This sets up the scrambled timeline of the flashbacks to come. (Hong mischievously zooms in on a letter she fails to retrieve, hinting at a gap in the story that will follow.)

What Kwon learns, in mixed-up order, is that Mori’s search for her leads him to meet and hang out with his landlady’s nephew, while also becoming romantically involved with Youngsun, the café owner. In the grip of a possessive lover, Youngsun attaches herself to the fairly passive Mori. Their affair plays out in Hong’s usual mix of drinking bouts and pillow talk.

By the time we’re used to this pattern, Hong sets up a new game. As he keeps cutting back to Kwon reading through the letters, accompanied by Mori’s voice-over, Hong gradually reveals that she is reading them in the Hill of Freedom café—the very place Mori hoped to meet with her (but never did).

Eventually, Kwon steps outside for a cigarette, and we suddenly get her voice-over remarking that the last letter was postmarked a week ago. Has Mori then already left and stopped writing? At this point Kwon encounters Youngsun coming in, and they greet each other as friendly acquaintances. The next scene finds Kwon visiting Mori’s guest house.

What happens there shifts the ground under our feet. After talking with friends, I think that we can’t be sure about what’s actually taking place. A mysteriously bruised cheek, a surprise reunion, and the return of Mori’s voice-over fill the penultimate scene. The coda is even more of a puzzler, at least to me. (I wonder if it’s the scene described in the letter that Kwon didn’t retrieve.) In any event, Hong’s usual themes of the foolish arrogance of Korean men and the comedy of male-female interactions are given new expression in this lightweight but enjoyable movie. The fact that Hill of Freedom is mostly in English, which Mori must employ to communicate with the Korean characters, adds to the fun.

Video virus

Yet another trigger for a flashback can be provided by a crisis situation. It might be rather near the story’s climax, so that we are left hanging and the plot takes us back to the origins of the problem. This is what we get in movies like The Big Clock (1947), which starts with our hero hiding out from the police and wondering how he got in this pickle. Or the crisis situation may come earlier in the story, with the flashback again filling in what led up to it before continuing the situation presented in the frame.

This latter option is followed in Mikhail Red’s Rekorder. After a brief prologue showing violent acts captured by CCTV cameras, we are in a police van with stern cops chatting about killing a dog before we’re introduced to the shaggy, wasted protagonist Maven riding with them.

From this framing situation we flash back to the reason Maven is in the van. Once a cinematographer in the glory days of Filipino cinema, he’s now a loner using his ancient camcorder to film movies in theatres and sell them to a friend who bootlegs DVDs.

Maven is a compulsive recorder. As the director puts it, he is “a ghost in the city observing everything through his lens.” So naturally he’s filming when a street gang kills a young man in front of a crowd who simply watch. Maven doesn’t volunteer his footage, since it includes part of a movie he was pirating. But now he’s been nabbed and is riding to headquarters with the cops, who are very curious about what’s on his tape.

Much of the rest of the film involves Maven’s attempt to keep the cops from examining his footage, while he agonizes about his passive acceptance of street violence. There are still more flashbacks, appropriately presented through old video footage of his wife and daughter. Not until the end of the film do we witness–again, on CCTV footage–the trauma that has turned him into the burnt-out case he is.

Mikhail Red commented that he was inspired to make Rekorder by a viral video in which a youth was shot in the street by thugs and a big crowd didn’t intervene but instead filmed the murder. He staged his own CCTV-style video to supply the denouement, and was shocked to find that it was appropriated in documentaries about street crime. Through a multimedia format, Rekorder updates the sort of social criticism that Raymond Red, Mikhail’s father, brought to Filipino cinema of the 1980s. That era as well is evoked through another sort of flashback, the clips from classic movies that Maven films. “I wanted,” Red says, “to pay homage to the pioneers.”

Straight time

You don’t need to play time tricks to create an uneasy movie. Ow (Maru) presents a typical family squeezed by Japan’s economic stagnation. Dad pretends to have a job, when he actually sets out each day for the unemployment office. Mom and grandma putter about. Grown but spacy Tetsuo lounges about his room talking baby talk. One day, when his girlfriend has just snuggled into bed with him, they are transfixed by a big gray-brown sphere that drifts into his room.

Transfixed, literally. They freeze upon seeing it. So does Dad, and so do the cops who are called. Director Suzuki Yohei introduces us to the big ball with a shot of it slowly spinning, held long enough for us to get slightly hypnotized too. There follows some comic suspense in which people enter the bedroom and may or may not leave. The biggest tease is the reporter who, after learning of a death during the sphere’s arrival, researches the case and then lunges into the room, ranting about a police cover-up.

The tension–will others fall under the spell or the sphere?–is accentuated by shrewd camera setups. When the cops arrive, we get a low-angle shot behind Yuriko and Tetso, showing the frozen cops and a new one not yet transfixed. He pushes one stiff colleague over, revealing the ball, still hovering there, and we wait for him to be the new victim.

Much later, when the reporter first visits the room, the sphere has vanished. But a rhyming angle forces us to remember its presence, and to let the reporter–the source of the plot’s momentum for the rest of the movie–take the place of the hapless cop.

Finally, for another exercise in unkinked time, there is the Korean action picture Haemoo. Produced by Bong Joonho, it centers on the desperate captain of a fish-trawler who agrees to bring illegal immigrants into Korea. Everything that could go wrong does: storm, fog, Coast Guard patrols, a horny crew, and an idealistic novice seaman who tries to protect a woman. Everything, including the accident that creates a horrifying midway turning-point, is carefully prepared in the film’s opening scenes. The film’s second half locks us into the relentless consequences of covering up a huge crime.

The pace is so snappy that I expected lots of cutting, but I counted only about eight hundred shots in 106 minutes. (The Equalizer, only twenty minutes longer, has three times that number.) I attribute this cutting rate to neatly functional direction, with no fuss or waste. The ship’s engine room is a cramped set, hazy with steam and dust, and the shots there are finely calibrated to build the drama through depth, fluid camera movement, and our old friend The Cross. The randy engineer’s business of checking the equipment carries him from one side of the shot to the other, while the young seaman shifts around him–first on frame right, then on frame left, then in the center.

The plot has that satisfying neatness that is characteristic of Bong’s work, and its forward thrust has no need of flashbacks. We can’t ask for backstory when the upcoming twists are as fast-paced and exciting as they are here. Dragons and Tigers has always showcased not only the experimental films like Ow and Hill of Freedom but also the crowd-pleasers, and Haemoo (which translates as “Sea Fog”) solidly fulfills that mission. Long live linearity!

Hill of Freedom has sharply divided critical opinion. Richard Brody considers it a masterpiece; others consider it fluff. At Fandor David Hudson painstakingly surveys the cut and thrust of the controversy.

Hill of Freedom.