Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

The World comes to Vancouver

The Golden Era.

Kristin here:

One of the great pleasures of the Vancouver International Film Festival is the ability it provides for a quick trip around the world, especially to countries whose films are seldom seen in a non-festival setting.

In one day I was able to see an Algerian film and one from the Ivory Coast. It struck me that both of them reflected how far digital filmmaking has come in small producing countries. When digital cameras came on the scene, they were hailed as a way for people in nations with little or no filmmaking infrastructure to create movies. The results, fascinating though they might be, often betrayed visually the fact that they were made with non-professional cameras.

Perhaps we have reached a new stage in digital filmmaking in such countries. Both the Algerian film, The Rooftops (Merzak Allouache, 2013), and the Ivory Coast one, Run (Philippe Lacôte, 2014), have a polish and complexity of form and style that put them on a level with those made in larger, more established national cinemas.

The Rooftops provides a model of how to make a film with a limited budget and avoid conventionality. Allouache chose to set the film entirely on the rooftops of five districts of Algiers. It’s a gimmick of sorts, and yet it carries practical advantages. No sets had to be built, and few, if any scenes required artificial light. Presumably no streets had to be cleared, since no action is staged at ground-level.

Beyond that, each scene could be played out with the city of Algiers providing a backdrop, as when a group of young musicians practice on one of the rooftops:

With backgrounds like that, who needs sets?

The film has a strict formal logic, both spatially and temporally. It begins by introducing five rooftops, each with its own set of characters. There’s no crossover among the groups. None of them ever meet, so this isn’t what David has termed a network narrative. But the look of each rooftop is different, and simply by keeping the characters in one limited area, the filmmakers help us keep track of them fairly easily as the narrative moves among storylines.

The film starts with the first call to prayer in the darkness before dawn, and at intervals the four other calls follow (with a subtitle providing information on the name of each call and the time period within which the respective prayers are supposed to be performed.) These essentially act as chapter breaks, giving a sense of time passing. The five prayers also echo the five rooftops.

There’s no shortage of drama in each group’s story. On a lower floor of an unfinished building a mob boss has a man tortured, trying to force him to sign something. This disturbs a group of filmmakers taking shots from the roof above, with dire consequences. A landlord is murdered on another rooftop, and a suicide occurs on yet another. One gets a cumulative impression of crime and conflict being rife across these various districts of Algiers.

Allouache is considered the preeminent Algierian director, and the violence and strife depicted rather melodramatically are part of his ongoing critique of his nation’s social problems.

In contrast, Lacôte sets Run apart by adopting a classic flashback structure. The film opens with the crisis of the story: the hero, nicknamed “Run,” shoots the prime minister in a crowded auditorium and flees.

From then on, we see him in hiding as he reflects on how he became an assassin. The alternation of scenes from his youth and his current-day attempts to avoid capture are easily comprehensible. Lacôste finds ways to create visual interest and avoid conventional stagings of scenes, as in the low angle above that juxtaposes the hero with a looming, crisscrossing ceiling.

Another example comes when his friend gives him shelter and food. Rather than a simple shot/reverse-shot conversation across a table, we see a depth scene, with Run sitting on the floor to eat and his friend in the foreground twisting to talk with him:

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the notion was that people in underdeveloped countries could gain small cameras and discover their own ways of making films, free of Hollywood conventions. To some extent that happened. But with the globilization of mass media, few people, however isolated, can remain unaware of Western culture.

Presumably some filmmakers have aspired to match the technical standards of Western offerings in international film festivals. These two films show them succeeding, having thoroughly grasped the conventions of both art films and popular genres. We ‘ll discuss an example of the latter in an upcoming entry on Middle-eastern films at VIFF, and in particular the Iranian vampire film, Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Ann Hui’s quiet epic

Ann Hui’s career is usually associated with intimate films, mostly studies of character. We saw her at Ebertfest earlier this year, where she presented A Simple Life, the epitome of such films.

Now she has surprised audiences with another character study, but one set in a tumultuous period of Chinese history, the late 1930s and early 1940s. The Golden Era (2014) tells the story of female writer Xiao Hong, who died young in 1942. Not all the facts of Xiao Hong’s life are known, and the narrative sketches scenes derived from the author’s own writings. Interspersed are “documentary” shots of interviews with people (played by actors) who knew and worked with Xiao Hong.

Much of the tale consists of small-scale scenes, conversations among a few people set indoors or in the streets. Yet as the Japanese invasion begins and spreads, occasional big scenes occur, and Hui proves herself perfectly capable of suggesting creating a sense of epic events.

The war is only fleetingly present, however. We see it mainly from the viewpoint of the main characters, as when a quiet indoor conversation scenes are abruptly and startlingly cut short by bombs going off outside and shattering windows.

The film’s settings and costumes create a vivid sense of the era. There are street scenes in Hong Kong shortly before its fall to the Japanese that appear almost documentary in their realism. Throughout the images are beautiful, as the frame at the top of the entry demonstrates.

The film’s three-hour running length adds to the epic feel, tracing the heroine’s changing fortunes across momentous historical events. It makes a striking contrast with A Simple Life, and yet Hui’s concern with precision and detail in delineating characters remains constant. The pair might bring her back to the sort of prominence outside Hong Kong that she enjoyed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Indeed, The Golden Era was just presented as the gala film at the Busan Film Festival.

Another farewell from a Ghibli master

Just over a year ago Miyazaki Hayao announced that he would retire, having completed and released his final film, The Wind Rises (2013). Speculation over the fate of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio that he co-founded, followed.

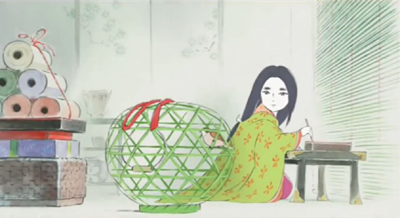

Now we have the reported final film of a second of the three original founders, Takahata Isao, whose most famous film is Grave of the Fireflies (1988). Like The Wind Rises, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2014) lets its director go out on a high note.

Based on a tenth-century fairy tale, Princess Kaguya has a distinctive style, with most scenes done in translucent watercolors in pastel shades, quite different from the solid, vivid colors of much of Miyazaki’s work. It tells its story in a leisurely fashion, running 137 minutes, which may be a bit challenging for younger children, but it is never boring.

Kaguya is not necessarily a princess. We’re not sure what she is. She appears miraculously one day as a tiny baby in a glowing bamboo shoot. She is iscovered by a bamboo-cutter who assumes she is a princess and insists on calling her that. The bamboo-cutter and his wife raise her in a forest cottage (seen below). The opening section is idyllic, with the tiny girl growing unnaturally fast, in spurts. She is befriended by neighboring children, and the group explores the surrounding countryside, reveling in the beauty of the plants and animals they observe there.

Spurred by another miraculous discovery, this time of gold nuggets inside a bamboo stalk, the bamboo-cutter decides to build a mansion in a nearby city and make Naguya into a real princess by marrying her off to royalty. There ensues the classic competition among suitors to find the most fabulous object and present it to Naguya.

Naturally Naguya longs for the countryside and finally rebels. In a remarkably stylized, exciting scene that contrasts with the rest of the film, she races toward her forest home, and the pastel settings disappear. She becomes a blur of black, white, and red flashing through a gloomy landscape with sketchily drawn trees and plants that flicker wildly past:

The Tale of Princess Taguya has been announced for an October 17 release in the USA, distributed by GKids. Unfortunately it will only be available in a dubbed version. Even dubbed, it’s worth seeing on the big screen, but with luck there will be an option for the original Japanese-language version with subtitles on the DVD/BD release.

Studio Ghibli has released another film, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a documentary about the studio by Sunada Mami. (It played at Toronto but is not here at VIFF.) Its appearance seems to hint that Ghibli really is going to cease feature production, though the official story is that it is only pausing. It has been a prolific producer of short animated films, and perhaps that side of its activities will continue. For a good summary of the situation and a description of the documentary, see here.

The Tale of Princess Taguya

Of horses, avalanches, and architecture

Of Horses and Men (2013).

DB here, with some first impressions of this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival.

We alternate days of rain and days of sunshine, but crowds still keep turning up. Some screenings are packed full, and most of those we’ve visited are solidly attended. Herewith some notes on three of the most intriguing movies I’ve seen so far.

The getting of wisdom

La Sapienza (2014).

The last Eugene Green movie I saw was The Portuguese Nun, which I discussed in a 2010 entry. His latest, La Sapienza, is more user-friendly, somewhat closer to American art-house accessibility.

A married couple in a politely disintegrating relationship takes a trip to Italy, and then their paths diverge. Alexandre, a famous architect who conducts research on the side, takes along on a field trip the young Goffredo, who wants to be an architect as well. Aliénor, a psychoanalyst, stays with Goffredo’s sister Lavinia, who suffers from fainting spells. Each character comes, by a quiet path, to a degree of peace and reconciliation. Alexandre even renews his creative energy, thanks partly to Goffredo, who insists that architecture is not only about space but what fills it: Light and people.

As ever with Green, everybody is gorgeous; the clothes are casually splendid; the backgrounds are magnificent. Threaded through La Sapienza is overwhelming architecture (Turin, San Carlino, Rome), accompanied by Alexandre’s discussion of Francesco Borromini’s career. The climax, a muted one, takes place in the Chapel of San Carlo, filmed in appropriately radiant majesty. In a way, the movie is a fine art-history class.

Crosscut with the two men’s journey are the ministrations of Aliénor to Lavinia, who comes out of her shell when shown kindly attention—and exposure to the theatre. (Le Malade imaginaire, no less.) Green is one of the few filmmakers today who makes movies in homage to the pleasures of aesthetic experience. No wonder that one of his films has the title Le Pont des Arts. But he’s not completely highfalutin. One scene makes fun of pretentious contemporary artists, chiefly to throw the purity of classic art into greater relief.

Green’s signature staging and cutting are still in force; he offers a sort of parodic simplification of analytical editing’s progression of master-shot, over-the-shoulders, and singles. Given these familiar patterns, we quickly get used to the artifice of to-camera address, sometimes in extreme close-up. Viewers who admire Wes Anderson’s style should check out Green’s more austere handling of planimetric imagery.

Most American studio pictures allot a separate shot for each character’s line, and Green does much the same, but his pace never seems as rushed. I think it’s partly because of the pauses between lines, which allow us to wait for more from the speaker, or to anticipate how the listener will react.

All in all, another piece in that cloisonné mode that Green has made his own. But La Sapienza has freshness because of its new subject matter. We get not a romance among young people but a fading love among their elders. The film harks back to a great tradition of disenchanted couples visiting alien places, from Voyage to Italy to Certified Copy. And the actors, particularly Christelle Prot as the wife, have an intelligent vivacity. Alexandre’s demeanor and expressions, robotic in the opening scenes, warm and relax across the film as he comes to enjoy visiting Borromini’s sites and learning from his young companion. The film exemplifies what Alexandre describes as one building’s integration of human bodies and rigorous patterns: “Living figures in geometrical constructions.”

A Nordic problem play

Another film about a couple’s troubles while they’re away from home is Force Majeure, a new Swedish film with the original title Turist. Tomas and Ebba seem to have a fine upper-middle-class family, with beautiful kids Vera and Harry. Seeking quality time, they arrive at a high-tone ski resort in the French alps. They have a pleasant visit at first, punctuated by the cannons that trigger controlled avalanches, until one such snow slide seems to threaten them on a patio. Tomas’ reaction puts their marriage in question, and Vera and Harry become fussy and scared. Tomas comes to see the family crisis as the collapse of his male identity.

As with the Green film, people talk a lot. In the great tradition of Nordic drama and Bergman psychodrama, what we’ve been shown must also be discussed, and the past dredged up, and bystanders dragged into intimate crises. The central scene, in which Ebba presses Tomas to explain himself in front of another couple, runs by my count over twelve minutes. Its painful but riveting drama drifts into satire when Tomas’ intellectual friend tries to find evolutionary explanations for what happened.

Unlike the Green film, Force Majeure is the opposite of austere. Even without the breathtaking scenery, the ski lodge is given a sort of ersatz grandeur itself. And the big moments swallow up speech in sumptuous visual effects, most obviously the avalanche but also an eerie scene that appears to record a flying saucer’s surveillance of the lodge. The spectacle doesn’t stop in the coda, a vertiginous bus ride that leaves issues of courage and family unity uneasily suspended.

Horse whisperers, and shouters

According to reports, John Ford once remarked that a running horse is the most beautiful thing in the world. There’s some evidence for the claim in Of Horses and Men, an Icelandic film about life in a valley among horse farmers. It’s composed of episodes of local life, sometimes trivial and sometimes life-or-death, taking place across a summer.

The locals let much of their stock roam across the valley until they herd them into a corral for the winter. The massive roundup, spiced with some sexual shenanigans, forms the film’s climax, with majestic shots of galloping horseflesh. The final crane shot celebrates the vastness of the herd against the stupendous landscape, while giving it human scale with an ambling musical score reminiscent of Morricone’s lighter tunes.

So this is not your standard hardscrabble-life-in-distant-places film. Granted, the neighbors, a scruffy lot given to passing around flasks and snuff, are attractively cranky and realistically unpretty. None would get an audition for Eugene Green. But their petty quarrels, as when one rancher keeps snipping the barbed wire that another rancher keeps stringing across a thoroughfare, become comic (though some lacerations are involved). Particularly hilarious is the scene of a rancher so devoted to drink that he goads his poor steed to swim out to meet a Russian fishing boat carrying lethally strong alcohol.

What a pleasure to meet a movie that tells its story visually! Details of behavior matter. The ritual of bridling a horse gets carried out in ways that characterize the riders, and there is one moment, in which a young woman accomplishes the apparently impossible, that is crowd-pleasing without being over the top—all presented briskly and with hardly any dialogue.

Another laconic scene takes place after the credits. A lantern-jawed rancher proudly steers his trotter to breakfast with a neighbor woman. Director Benedikt Erlingsson introduces other major characters by showing them in their yards watching the gentleman’s ride. In turn, he learns they’re watching by catching the glint of sun on their binoculars.

This bit of routine suggests what passes for entertainment among these nosy folks. It also becomes a running gag, so that in later scenes, as soon as we cut to the horizon and see the telltale flash, we know someone’s eyeing the action. This sort of pictorial economy, rare in today’s films, eliminates exposition and lets us think we’re smart.

In fact, the act of looking becomes a persistent motif, as most episodes are introduced by a screen-filling close-up of a horse’s eye, with humans or landscapes reflected there. It’s as if these beautiful beasts are quietly observing their masters’ foibles.

Kino Lorber will distribute La Sapienza in the United States, Magnolia will do the same with Force Majeure, and Music Box Films will be offering Of Horses and Men.

La Sapienza.

VIFF 2013 finale: The Bold and the Beautiful, sometimes together

Gebo and the Shadow (2012).

DB here:

I’m a little late catching up with our viewings at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year (it ended on the 11th), but I did want to signal some of the best things we didn’t squeeze into earlier entries. Kristin and I also want to pay tribute to one of the biggest moving forces behind the event.

Safe but not sorry

Like Father, Like Son (2013).

Among other goals, film festivals aim to provide a safe space for nonconformist filmmaking. Programmers need to find the next new thing—art cinema is as driven by novelty as Hollywood is—and they encourage films that push boundaries. What isn’t so often recognized is that sometimes festivals show filmmakers who were once quite artistically daring backing off a bit from their more radical impulses. Part of this is probably age and maturity; part of it reflects the fact that apart from daring novelties, festivals also showcase works that might cross over to wider audiences. And of course festivals will present recent works by the most distinguished filmmakers, almost regardless of the programmers’ hunches about their quality. Some sectors of the audience want to see the latest Hou or Kiarostami or Assayas.

Koreeda Hirokazu was thirty-three when Mabarosi (1995) won a prize at Venice. It’s an austerely beautiful work, presenting a disquieting family drama in very long, static takes. Once the action shifts to a seacoast village, distant shots render slowly-changing illumination playing over landscapes, while the tension between husband and wife is built out of small gestures. For example, we learn that the forlorn wife is waiting in the bus stop only when a little bit of her comes to light.

Lest this seem just fancy playing around, Koreeda occasionally used his long takes to build suspense. Yumiko’s new husband has been drinking. While he’s out of the room, she opens a drawer to retrieve the bike bell she keeps in memory of her first husband, killed in a traffic accident. The second husband returns unexpectedly, and drunkenly collapses on the table beside her. But when she lifts her hands out of her lap, she inadvertently lets the bell tinkle a little.

The sound rouses him and he asks what she’s holding. She raises her head at last and they begin a quarrel about each one’s motives in marrying the other.

Eventually he will shift woozily to the other side of the table and notice what has been sitting quietly in the frame all along: the still-open drawer on the far right.

In later films, from After Life (1998) to I Wish (2011), Koreeda’s visual design became less reliant on just-noticeable changes within a placid shot. The images have become less demanding, and more extroverted narrative lines carry stronger sentiment. The films remain admirable in their ingenious plotting and mixture of humor and pathos—which is to say, they are committed to that “cinema of quality” that makes movies exportable.

That commitment is firmly in place in Like Father, Like Son. Koreeda, now fifty-one, dares almost nothing stylistically or narratively. Yet every scene leaves a discernible tang of emotion, and his light touch assures that things never lapse into histrionics. If Nobody Knows (2004) and I Wish (2011) are his “children films,” this is, like Still Walking (2008), a movie about being a parent.

The plot has a fairy-tale premise: Babies switched at birth. Our viewpoint is aligned with the well-to-do parents and particularly the ambitious executive Ryota. When he finds that six-year-old Keita isn’t his birth son, he insists on swapping the boy into the household of the happy-go-lucky working-class Saiki family. In exchange, Ryota and his wife take in the boy that Saikis have raised as their own.

As the film proceeds, our view widens to create a welter of comparisons—two ways of being six years old, tough discipline versus easygoing parenting, what rich people take for granted and what poor people can’t, a solicitous mother versus one who can’t spare time for coddling. Koreeda is faultless in measuring the reactions of all involved. Ryota’s wife slips into quiet depression. Saiki is an affable father with a childish streak, but he also looks forward to suing the hospital. Saiki’s wife, a no-nonsense woman with two other kids to care for, is a mixture of toughness and maternal affection. As in a Renoir film, everyone has his reasons, and the drama depends on a process of adjustment stretching across many months. Climaxes become muted, though no less powerful for that.

A smile and a tear: the Shochiku studio formula, enunciated by Kido Shiro back in the 1920s, remains in force here. Simple motifs, such as images stored on a camera’s photo card, hark back to all those affectionate picture-taking scenes in Ozu’s classics. The whole is shot with a conventional polish—coverage through long lenses, straightforward scene dissection—that’s far from the strict, slightly chilly look of Maborosi.

It’s impossible to dislike this warm, meticulously carpentered film. Koreeda has proven himself a master of humanistic filmmaking, and I admire what he’s done (as these entries indicate). Those of us who’ve been following his career for nearly twenty years, however, may feel a little disappointed that he hasn’t tried to stretch his horizons a bit more.

Like Father, Like Son was rewarded with the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes festival. Steven Spielberg, jury president, has acquired remake rights for DreamWorks.

Action, blunt or besotted

A Touch of Sin (2013).

Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin offers a comparable adjustment to broader tastes. It’s far less forbidding than his early features Platform (2000), Unknown Pleasures (2002), and The World (2004). Somewhat like Koreeda, Jia’s earliest fiction films embraced a long-take aesthetic that tended to keep the characters’ situations framed in a broad context. (His documentaries, like the remarkable 2001 In Public, were somewhat different.) Jia proceeded to breach the boundary between documentary and fiction in Still Life (2007), Useless (2007), and 24 City (2008). With A Touch of Sin, Jia takes on a twisting, violent network narrative that is as shocking as Koreeda’s duplex story is ingratiating.

We start with a villager who fumes at the corruption in his town and carries out a vendetta against its rulers. Another story centers on a receptionist who is taken for a prostitute and abused by massage-parlor customers. A third protagonist is an uneducated young man floating among factory jobs who turns his frustration inward. Threading through these is a drifter who shoots muggers from his motorcycle and later takes up purse-snatching.

The sense of inequity and exploitation that ripples through Still Life and 24 City now explodes into rage. Rich men (one played by Jia) puff cigars while strutting through a brothel, businessmen casually exploit their mistresses and buy off politicians, and injustices are settled with fists, knives, pistols and shotguns. “I was motivated by anger,” Jia says. “These are people who feel they have no other option but violence.”

Like Koreeda, Jia has had recourse to some of the casual long-lens coverage we find in many contemporary movies, but certain shots gather weight through his signature long takes–especially shots holding on brooding characters. In all, we get a dread-filled panorama, with bursts of violence staged and filmed with an impact that reminds you how sanitized contemporary action scenes are.

For more, see Manohla Dargis’ rich Times review of the film.

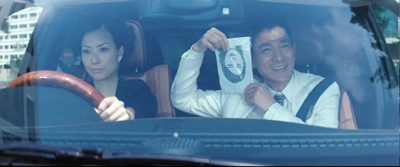

After the painstaking (and pain-giving) dynamics of Drug War (our entry is here), one of Johnnie To Kei-fung’s best recent films, it’s wholly typical that he does something outrageous. His work with Wai Ka-fai at their Milkyway company has always alternated unforgiving crime films of rarefied tenor with sweet and wacko romantic comedies that assure solid returns. But seldom have they combined the two tendencies into something as screechingly peculiar as The Blind Detective.

Initially the investigator, inexplicably named Johnston, seems to be a brother to Bun, the mad detective of To and Wai’s 2007 film. He insists on having the crime reenacted so as to intuit the perp’s identity. But since Johnston is blind, somebody else must tumble down stairs, get whacked on the head, and generally suffer severe pain in the name of the law. Ready to sacrifice herself to Johnston’s mission is officer Ho, a spry and game young woman with a crush on him.

Johnston and Ho are trying to find what happened to a schoolgirl who went missing ten years before. But this account makes the movie seem more linear than it is. Johnston makes his living from reward money, and he’s also dedicated to finding a dancing teacher he fell in love with when he had sight. So the search for Minnie is constantly deflected. Yet the digressions end up, mostly through Johnston’s inexplicable flashes of imagination, carrying them back to their main quest.

This episodic plot, or rather two plots, stretched to 130 minutes (making this the longest Milkyway release, I believe), yields something like a Hong Kong comedy of the 1980s, where slapstick, gore, and non-sequitur scenes are stitched together by the flimsiest of pretexts. The tone careens from farce (not often very funny to Westerners) to grim salaciousness. Johnston’s intuitive leaps are represented by blue-tinted fantasies that show him gliding through a scene at the moment of the murder, or assembling a gaggle of victims to declaim their stories. Characters are ever on the verge of exploding in anger or aggression, and between the big scenes Ho and Johnston dance tangos and gnaw their way through steaks, fish, and other delicacies.

Once more, the congenitally fabulous Andy Lau Tak-wah is accompanied by Sammi Cheng as his love interest, and the two ham it up as gleefully as in Love on a Diet (2001). (They were more subdued in my favorite of the cycle, Needing You…, 1999.) This is, in short, a real Hong Kong popular movie. It brought in US $2.0 million in the territory, and $33 million on the Mainland, about the same as Monsters University. If it keeps Milkyway in business, how can I object?

For a discerning take on The Blind Detective, see Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm.

JLG in your lap

Kristin and I were keenly looking forward to 3 x 3D, the portmanteau film collecting stereoscopic shorts by Peter Greenaway, Edgar Pêra, and Jean-Luc Godard. Kristin found the Greenaway episode–sort of his version of Russian Ark, taking the camera through the labyrinth of a ducal palace and showing off elaborate digital effects–fairly appealing. But for us the Godard was the main attraction, and he didn’t disappoint.

At one level, The Three Disasters reverts to his characteristic collage of found footage, film stills, scrawled overwriting, and insistent voice-over. (Is it my imagination or does the the 83-year-old filmmaker’s croak sound increasingly like that of Alpha 60?) The montage is sometimes over-explicit, as when Charlie Chaplin is juxtaposed with Hitler. There’s a funny passage of portraits of one-eyed directors (Lang, Ford, Ray), as if to reassert the primacy of classical monocular cinema. At other points, things get obscure, as when Eisenstein’s plea for Jewish causes during World War II is followed by shots from The Lady from Shanghai. But this is the Godard of Histoire(s) du cinema, piling up impressions that beg for acolytes to identify the images and find associations among them.

Frankly, this side of Godard doesn’t grab me as much as his pseudo-, quasi-, more-or-less-narrative features. But in 3D his dispersive poetic musings take on a new vitality. He doesn’t retrofit old movie clips and still photos for 3D. Instead he superimposes them, making one cloudy plane drift over another. He can also, more forcefully, present his signature numerals and intertitles in a new way–by having them pound out of the screen and hang rigidly in front of the image.

There are also some 3D shots made specifically for the film, most consisting of handheld shots that shift around a park, a medical complex, and, of course, a media studio. The very title of Godard’s film, punning on 3D as a technical disaster, as well as a throw of the dice (dés), suggests his ambivalence toward the technology. “The digital,” his voice declares, “will be a dictatorship,” but perhaps it will never abolish chance.

As usual, Godard has fun with simple equipment. He frankly shows us his camera rig, two Canon DSLRs lashed together side by side, one upside down. By shooting them in a mirror and shifting focus, he manages to make each lens pop and recede disconcertingly, as if Escher had gone 3D. This shot alone should inspire DIY filmmakers everywhere. So too should the one-slate credits. Whereas Greenaway’s segment lists scores of names in its credit roll, Godard’s lists only four, alphabetically. I can’t wait for the feature, Farewell to Language. (Trailer here.)

Brian Clark has an informative review of The Three Disasters at twitchfilm.

Looking at the fourth wall

In nineteenth-century Portugal, the elderly Gebo ekes out a living as a company accountant. His wife Doroteia and his daughter-in-law Sofia wait with him for the return of João, a rebellious ne’er-do-well. Gebo feeds Doroteia’s illusions about their son, who has likely become an outlaw. When João returns after eight years away, he throws the family into turmoil and becomes fixated on the cash that his father safeguards for the firm.

After World War II, André Bazin noticed that many filmmakers were starting to take a creative approach to adapting plays. Olivier’s Henry IV, Welles’ Macbeth and Othello, Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, Melville’s Les Enfants terribles, Hitchcock’s Rope, and Wyler’s Little Foxes and Detective Story, are far from the “photographed theatre” that some critics feared would dominate talking pictures. For decades Manoel de Oliveira has explored avenues of theatrical adaptation that have led us to some daring destinations. Gebo and the Shadow, drawn from a 1923 play by the Portuguese Raúl Brandão, is a powerful recent example, and possibly the best film I saw at VIFF this year.

After the credits show João loitering on the docks, the film confines the action almost wholly to the parlor of Gebo’s family home. Early on we see the street outside through a window, but most of the film concentrates on the characters gathered around the room’s central table. On stage, we can imagine the table at the center and the major characters assembling around it but leaving one side clear, facing the audience–in effect, accepting the convention of the invisible fourth wall that gives us access to the space.

As the still above suggests, it seems initially that Oliveira is playing up this convention, putting us into the stage space and setting the fourth wall behind us. Very soon, though, we’re inserted between the players, so that we see the other side of this lantern-lit playing space.

For the most part, the first stretch of conversations and soliloquys among Gebo, Doroteia, and Sofia are played out in this planimetric, clothesline layout. So is the late-night arrival of the vagrant João, coming to sit opposite his father and laughing wildly. This shot corresponds to the end of the play’s first act.

On the next day, when Gebo and his family receive some friends, the table is sliced in half.

The effect is to redouble the sense of proscenium space, presenting two planimetric arrays that always keep one “behind” us.

Like other chamber-plays-on-film (Dreyer’s Master of the House, Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder), Gebo varies its spatial premises slightly to incorporate other possibilities. In the stretch corresponding to the second act of the play, the angle on the table changes twice, once to present the split table-scene above, and later, to the climactic moment when João joins Sofia and contemplates breaking open the strongbox.

Sometimes we’re shown the window and other walls, usually presented when characters leave one shot and enter another. The constructive editing helps us tie together zones of the room that aren’t ever given in an all-encompassing master shot. And the camera never moves, not even to reframe characters’ gestures.

In previous films, Oliveira has played with the ambiguities of who’s looking where. (See, for instance, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Hair Girl and The Strange Case of Angelica.) After a mysterious prologue involving João, a ravishing image presents Sofia watching at the window, then moving aside to reveal Doroteia behind her (and behind us).

As often happens, the start of a film sets up an internal norm; it teaches us how to watch it. This movie starts with a lesson in optical geometry. Sofia watches the street, goes out to scan for Gebo’s arrival, then watches Doroteia from outside the window before coming back in and resuming her position at the window. As the shot develops, we can see Doroteia lighting a lamp and reflected in the window against the distant doorway.

When Sofia walks out of the shot, Oliveira’s camera lingers on the window, in which we can still see Doroteia turning her head to watch Sofia’s coming to her. This is the shot, imperfectly reproduced, that’s at the top of today’s entry. The image isn’t far from the gently insistent changes of Koreeda’s Maborosi. This film about a shadow starts with an image of a spectre.

Constructive editing often relies on a glance offscreen, so here he can play with minute differences of eye direction. Occasionally the actors look directly out at us. But when the table is halved, as above, the eyelines get very oblique, with opposite characters looking in the same direction.

In the third act, the frontal and planimetric grouping around the table returns. Gebo has searched fruitlessly for João and has returned to take the consequences of his son’s theft.

Oliveira’s adaptation omits the play’s fourth act, when the family is reunited three years later. His version leaves the family suspended in a freeze-frame, haunted by the ghostly son who has betrayed their trust. This dramatic climax is also a visual one, with sunlight for the first time spilling into the chilly, lamplit parlor and its inhabitants startled, as if they shared João’s guilt.

Perhaps more than the other films in this entry, Jebo and the Shadow shows why we need film festivals. Oliveira’s purified experiment demands a lot from the audience, but it repays our efforts. It’s at once an engrossing story and an exciting exercise in what cinema can still do. Note as well that I have managed to get through a discussion of Oliveira’s film without mentioning his age.

For more on the film, see Francisco Ferreira’s very helpful essay in Cinema Scope.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

For Kristin and me, he has been a wonderful friend and good-humored company. Alan’s deep commitment to great cinema has shown in his recruitment of colleagues, his skilful defusing of potential crises (most recently the shift to digital projection), and his genial, almost Zen, good nature. Fortunately for the festival, he will remain as a programmer. He deserves our lasting thanks.

Good news for US audiences on some of these titles: Sundance Selects will distribute Like Father, Like Son, while Kino Lorber has wisely acquired rights for A Touch of Sin. Gebo and the Shadow is available on an English-subtitled DVD from Fnac and Amazon.fr. It’s a very dark movie, and in order to make the frames readable here, I’ve had to brighten them a bit. These images don’t do justice to what I saw in the VIFF screening, or even to what the fairly decent DVD looks like.

For more on planimetric staging of the sort we find in Gebo and Maborosi, see entries here and here and here. It’s a common resource of modern cinema, and directors utilize it in a variety of ways.

Les trois désastres (2013).

Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to VIFF

Closed Curtain (2013).

Kristin here:

Two years ago David and I wrote about a group of Iranian and Israeli films that featured prominently in the 2011 VIFF program. This year’s program boasted several more, many of them by the same directors.

Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovi, 2013)

Despite still being banned from filmmaking and forbidden to leave Iran, Panahi has followed This is Not a Film with another fascinating feature that has made its way abroad. This time he co-directs with Kambuzia Partovi, who also plays one of the main characters, a screenwriter.

The writer flees to a seaside house (apparently Panahi’s) to hide his dog from a roundup of animals deemed “unclean” under Islam. Once ensconced, the writer tries to conceal his pet by sealing the many large windows with opaque curtains. Eventually their privacy is invaded by another refugee, a young woman sought by local police for participating in a nearby party.

This first section of the film seems to be a straightforward allegory for Panahi’s own situation, but well after the midpoint, Panahi himself appears and takes over as the main character. With the curtains removed, he stares at the pond behind the house, seemingly having a vision of himself amid the beauties of nature. He also gazes at the sea in front of the house, envisioning himself walking into it to commit suicide.

The opening stretches emphasize suspense, when the writer hears voices and sirens outside, and unseen officials hammer against the door. The result is an image of the creative artist forced to conceal himself from forces of authority. With Panahi’s appearance, the film becomes more subjective than allegorical, and the abrupt juxtaposition of the two parts of the film create a puzzling whole. But that whole is rigorously filmed and arouses interest throughout.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Mohammad Rasoulof, 2013)

In 2010, I posted about Rasoulof’s beautiful film, The White Meadows (2009), an overtly allegorical film about the sufferings of various sectors of Iranian society. At that point I wrote, “He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen.” Most immediately, he was given a prison sentence and banned from filmmaking. Neither condition evidently kept him from finishing the impressive Goodbye (2011), which I discussed here. More recently, upon returning to Iran from Europe, Rasoulof has had his passport seized and is unable to travel or to reunite with his family. Most observers believe that this treatment is a response to his harshly critical new film, Manuscripts Don’t Burn, which has attracted attention at several festivals.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn differs considerably from The White Meadows. There is no hint of allegory here as Rasoulof examines the state surveillance system.The plot centers around two dissident authors and their strategies for hiding their manuscripts and evading the authorities. While a ruthless, educated young official decides on two authors’ fates, two working-class men carry out the kidnapping, torture, and murders that he orders. The hitmenare seen as victims themselves, as one of them, trying to pay medical bills for a sick child, continually finds that his last job’s payment has not yet been transferred to his bank account. They endure stakeouts in chilly weather and grab takeout food on the fly. The whole film is shot in muted tones (in both Tehran and Hamburg) and conveys a sense of unrelenting grimness.

The plot is drawn from unspecified real-life events, and the film cautiously carries no credits for cast or crew. (For more information on the film’s background, see Stephen Dalton’s informative review from the film’s premiere at Cannes.)

The Past (Asghar Farhadi, 2013)

Since A Separation (2012; see our entry here) became the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film, Farhadi has become the most prominent director working in that country. This is witnessed by the fact that his new film, The Past, has been put forth as Iran’s candidate for this year’s Academy nomination.

The plot of the new film draws upon familiar strategies that created a strong, moving situation in A Separation. Again a husband and wife are on the brink of divorce. In this case, the husband, Ahmad, is Iranian, and the wife, Marie is French. Clearly they had lived together for a time in France, since when Ahmad arrives from Tehran, he knows how to get around Paris. Marie has two daughters from a previous marriage and plans to marry the small-businessman Samir, by whom she is pregnant. Samir has a morose young son who resists the idea of having Marie as a mother.

With this larger cast of characters, disagreements and obstacles pile up. Marie is extremely strict and strong-willed. Her older daughter is rebellious and stays out late. Ahmad tries to mediate between Samir’s miserable son and Marie’s scolding, while Samir tries to please Marie and still help his son adjust to the upcoming marriage.

As in A Separation, The Past builds up a mystery about an unhappy event. Samir’s wife has attempted suicide. What led her to this desperate measure? Her chronic depression? An embarrassing argument with one of Samir’s customers? Or did she know of Samir’s affair with Marie? Ahmad’s attempts to solve this mystery provide a strong, intriguing subplot alongside the shifting conflicts among the main adult characters.

With so many characters involved, the accumulation of problems and unhappiness eventually threatens to tip over into an exasperating melodrama. But I think Farhadi juggles all these motivations and events so well that we never feel that he has gone too far.

There has been some controversy over the fact that the film was shot entirely in France and therefore has little Iranian about it. Indeed, the Farsi-speaking emigrés who attended the VIFF screening to hear their native language spoken were perhaps disappointed that it was all in French. Yet in an ensemble cast, Ahmad remains the central character, helping to reconcile the others and comfort the three children (as in a rare cheerful moment when he helps the younger ones get a toy out of a tree).

If not quite as satisfying a film overall as A Separation, The Past confirms Farhadi as an Iranian director who can make appealing films for an international audience.

Trapped (Parviz Shahbazi, 2012)

Trapped is probably closer than most Iranian films shown at festivals to the sort of thing seen by popular audiences in its home country. The program notes describe it as a “moral thriller.” It revolves around Nazanin, a studious first-year medical student (see image at bottom) forced through lack of dormitory space to share a flat with party-loving Sahar, who is trying to leave Iran. Sahar has borrowed money to pay for her exit visa and, unable to pay it back, is imprisoned. Nazanin struggles selflessly to help her out, including foolishly signing a promissory note taking on Sahar’s debt and even sharing the threat of imprisonment.

The plot reminded me of the “child quest” tales that were prominent in the golden age of the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s, such as The Mirror and Where Is My Friend’s Home. (Shahbazi was the assistant director of Panahi’s The White Balloon, as well as conceiving its basic premise.) Here the heroine is distinctly older than the protagonists of those films, but she retains a naivete that makes her seem more childlike than the other characters, who manipulate and ultimately threaten her.

While Trapped doesn’t have the simplicity and charm of those earlier films, it offers an absorbing story. It paints a grim picture of Tehran and gives some insight into the realities of life there. Like many Iranian films, it raises the prospect of emigration, though in this case Nazanin’s strong desire to stay in the country and become a doctor is held up as the better choice.

A Place in Heaven (Yossi Madmony, 2013)

Two years ago I also reported on Madmony’s Restoration. A Place in Heaven is a considerably more ambitious film. It traces the life of a military hero, known only by his wildly inappropriate nickname Bambi, across much of Israeli history. The title derives from a flashback scene early on, when a cook at a military camp praises Bambi’s brave deeds and remarks that he has already earned a place in heaven. A secular Jew, Bambi scoffs at the notion and signs an impromptu contract trading that place to the cook in exchange for a daily spicy omelet.

Although Bambi dotes on his son Nimrod, the boy grows up to become a strictly religious Jew who disapproves of much that his father does. Still, when Bambi is on his deathbed, Nimrod goes in search of the cook to get back the place in heaven. As with Restoration, the plot is largely based around the father-son relationship, though there is also a touching and tragically short relationship between Bambi and his beautiful wife.

Unlike the largely urban Restoration, this film shows off the bleakly beautiful landscapes of Israel’s desert.

There were many other striking and moving films on display at VIFF this year. David and I really can’t do justice to all of them, but in a final post he will consider Koreeda’s Like Father, Like Son, Jia’s A Touch of Sin, Johnnie To’s The Blind Detective, the Godard segment of 3x3D, and Oliveira’s Gebo and the Thief. Like the items I’ve invoked here, each deserves an entry to itself, but time limits and further travels force us to be quick. Still, we hope that you can tell from our entries, VIFF 2013 yielded an extraordinarily high level of quality. As usual!

P.S. 17 October 2013: Thanks to Hamidreza Nassiri for correcting the original entry: Panahi is not, as we had said, under house arrest.

Trapped (2013).