Archive for the 'Festivals: Venice' Category

Venice, virtually

Careless Crime (2020)

Every September over the last three years, we’ve immensely enjoyed visiting the Venice International Film Festival. There David has participated in the Biennale College Cinema discussions with stimulating colleagues.

This year, alas, the coronavirus kept us home. But the festival did make available a selection of fourteen films online. Each could be viewed for five days at the very fair price of $6 per film. (Here is the array of choices. A few are still available, so hurry.)

We took advantage of this opportunity and watched several titles. Here are our thoughts about three of them. (The first section is by David, the second by Kristin.) We hope that if you get a chance to see them on the big screen or at home you’ll investigate.

GOFAC is back! Actually, it never went away

The Art of Return (2020).

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I tried to analyze the conventions governing a certain approach to moviemaking, the one that’s come to be called “art cinema.” My examples were films by Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, the French New Wave, and many of their contemporaries.

In the years afterward, I revisited the ideas and asked: Are these conventions still in force? My conclusion in an updated version of the essay in Poetics of Cinema (2008) was: yes. From Fassbinder to Wong Kar-wai, from Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) to Maborosi (1995) and beyond, we can find art-cinema principles of storytelling and style. In that book, the extended example was Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985), while other chapters traced how this tradition mobilized new options like forking-path narratives (e.g., Run Lola Run, 1998) and network narratives (e.g., Les Passagers, 1999). There’s a pirated pdf of the updated essay here.

Since then, it’s been fascinating to watch a younger generation of filmmakers take up this tradition. Every festival I visit furnishes examples, as you can see from our entries on this site. I had the same sense when watching Pedro Collantes’ The Art of Return (El Arte de Volver) and Christos Nikous’ Apples (Mila). Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema is still with us.

The Art of Return is centered on Noemi, who returns to Madrid after six years in New York. She has come home to audition for a role in a telenovela, and in the course of twenty-four hours she encounters several people from her past. The film consists of a series of duologues, as Noemi visits her dying grandfather, quarrels mildly with her sister, reconnects with her actor friend Carlos, and learns through another friend what became of Alberto, her ex.

What makes The Art of Return a prototypical art film is the way sheer chronology replaces a strongly causal plot. Apart from attending her audition, Noemi doesn’t have a strong goal; she drifts from one encounter to another. Most of these long scenes are devoted to discussions of her past, with hints about why she left Spain, as well as reactions of others to her personality. The task for a filmmaker using this episodic structure is to create patterns of revelation for us and for the character.

We need backstory about Noemi, and Collantes shrewdly avoids supplying flashbacks that would supply that. Instead, her past is refracted through the reactions of characters who are reconnecting with her, after much that has happened in their own lives. Gradually we assemble a fragmentary sense of what impelled her to go to New York. This revelation of the past is in effect the “under-plot” of the action.

Along with this pattern of revelation for us there are revelations for Noemi herself. She learns about her friend Ana’s floundering artistic ambitions, about her ex Alberto, about Carlos’ judgments of her. In an art film, the keenest revelation for the protagonist comes through an epiphany, a moment in which the character–sometimes mysteriously–gains self-awareness.

The crucial epiphany in The Art of Return, I think, occurs in a quiet scene in the park, among the trees that Noemi feels have been sculpted by a mystical force. By chance–again–she sees something that gives her the strength to make a decision. Yet in a typical art-cinema move, the outcome of that decision is withheld from us, suspended in a shot reminiscent of The 400 Blows (1959).

Collantes skillfully creates a firm pattern, with the opening scene symmetrically balanced by the final audition. In between, as in La Dolce Vita (1960) and Angela Schanelec’s Passing Summer (2000), the protagonist’s encounters provide a sampling and survey of life in the city, from the bohemian artists to the Romanian migrant community. A College selection, The Art of Return has already been acquired for theatrical distribution in Spain and other territories.

Apples (2020).

Because the art-cinema tradition minimizes a goal-directed plot, it often creates patterning through routine actions that are modified across the film. The changes in the routines reveal changes in a character or a situation. A vivid example is given in the Greek film Apples. After we’ve seen our protagonist regularly buy and eat apples (lots of ’em), he learns from a grocer that apples sharpen memory. He immediately switches to oranges. What psychology can justify this strange piece of behavior?

We understand it completely, because what has gone before has created a compelling context. The era is vaguely pre-digital, though there are some anachronisms. In the midst of an epidemic of amnesia, the poker-faced Aris is taken to a clinic for memory recovery. His doctors have created an experimental technique to give him a new life by reenacting routines of childhood, adolescence, and young manhood. As he rides a bike, fishes in a stream, visits a costume party, and goes to a dance club, he records his actions on Polaroids. These will fill an album and serve as replacement memories.

So Aris has a goal, albeit a diffuse one. We haven’t been told his overall program, so we are left to slowly figure out the rationale behind his dressing up as an astronaut or getting a lap dance. The film’s narration is almost as laconic as its protagonist, although a couple of scenes with his doctors show some sardonic humor. They eat his cooking and ignore the pathos of his situation while also, probably, misdiagnosing him.

Crucially, his retraining regimen intersects with that of another amnesiac, a woman further along in the program. Their relationship gives the film a romantic subplot, as well as its two most exuberant scenes: a dance to “Let’s Twist Again,” in which Siri seems to suddenly recover muscle memory, and a drive that spurs him to sing along with “Sealed with a Kiss.” (Hints about the under-plot give these scenes a dose of mystery and ambiguity–two more appeals of art-cinema storytelling.) All of this takes place before the apples-to-oranges shift, which in this context becomes as dramatic a twist as one would find in a thriller.

Shot and paced with extraordinary rigor in the 4:3 format, Apples is a perfect example of how GOFAC can create a distinct blend of curiosity, surprise, humor, and suspense. The film’s revelations in the final stretch are carried out as unemphatically as everything else, lending the character’s secrets an austere dignity. Apples has been eagerly acquired for many territories, and the director, who worked with Yorgos Lanthimos on Dogtooth, is preparing an English-language project. It will be, he hopes, “more accessible/mainstream.” Not entirely, I hope.

A carefully artful Iranian film

Careless Crime (2020).

Back in 2014, we were introduced to the strange world of Iranian director Shahram Mokri with his second feature, Fish and Cat. It’s a 139-minute single-take movie with a twisty plot in which the camera runs into separate groups of people in a rural lake area, with events starting to repeat from different points of view as the camera circles back on its route. We saw it in Vancouver, but it had premiered in the Orrizonti program at the Venice International Film Festival in 2013; it won a special prize “For Innovative Content.”

This year Mokri was back in the Horizonti thread with his third feature, Careless Crime. This time Mokri didn’t win a Festival prize, but the film received a FIPRESCI award for Best Screenplay.

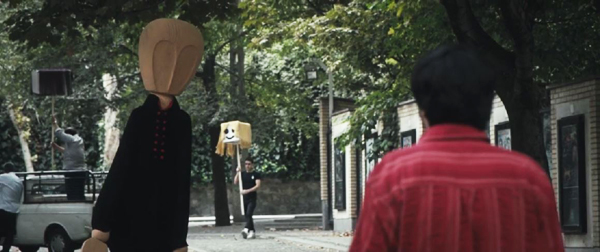

Careless Crime is even trickier than Fish and Cat. It’s one of those puzzling films that requires the spectator to figure out the time frames of the different plot threads–and indeed how many times frames there are–and keep track of many characters. It’s a bit like Lazlo Nemes’ Sunset in the way it demands that the viewer constantly keep on the alert for the most fleeting or oblique clues as to what’s going on. (It’s interesting that Nemes and Mokri both have a penchant for lengthy tracking shots following a character closely from behind, as in the frame above.) Apples is another film that provides only a few subtle clues abut a major plot premise that eventually provides a twist at the end

There are two major plotlines. A group of four scruffy men plan to set fire to a crowded cinema as a political protest. Their actions recall an actual event that was the inspiration for the story. In 1978 a group of four arsonists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan, causing the deaths of over 400 people because the exits were blocked.The event is credited with having launched the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

We follow the four men as they carry out inept preparations for their attack on the cinema. The group includes Faraj, a sad-sack who spends much of the early part of the film trying to get the nerve pills to which he is addicted. He tracks down a dealer who happens to be an employee at the local cinema museum and who is dressed in a large puppet costume, from the depths of which he digs out the precious bottle for Faraj.

The second plot involves a small, equally inept group of soldiers who have been sent to deal with an apparently unexploded missile deep in the countryside (see top). Contradictory information suggests that the missile landed some time ago and has been defused or that it landed the day before and needs urgent attention. Instead the men wander up into a local tourist area where two college girls are setting up an outdoor screening of the classic 1974 Iranian film, The Deer. This happens to be the film that had been screening at the Cinema Rex when the 1978 arson attack occurred. But the soldiers neglect their duty to solve the missile problem and spend their time waiting to see the young women’s film to find out if they are up to something nefarious. Thus two “careless crimes” may be involved. The the relationship between the two plotlines only becomes apparent late in the film.

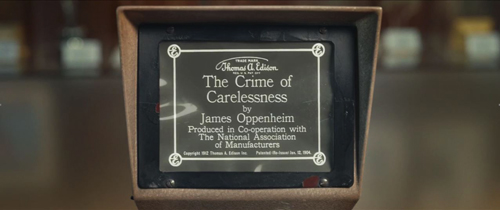

An obsession with cinema runs through both plots. The cinema targeted by the terrorists is apparently attached to the nearby museum and shows mostly art films, as is suggested by the posters for classic films that decorate the lobby. Young patrons and supporters of the cinema who hang around waiting for the show to start mention repeatedly that a friend has written an essay on The Deer, and we glimpse a poster for Kiarostami’s Close-Up. At one point Faraj, seeking the drug-dealer at the museum, sees a vintage film playing on an editing table.

It’s a 1912 Edison film, The Crime of Carelessness, in which poor safety conditions and a carelessly dropped cigarette led to a disastrous mill fire. At the end, a title in Farsi comes up, describing not the action of the silent film just shown but the 1978 Cinema Rex fire.

As all this suggests, there’s a good deal of magical realism in Careless Crime. At one point a single long take meanders around the open-air setting for the girls’ screening, picking up the same actions and dialogue repeated from different angles. During Faraj’s search for the drug-dealer, a museum employee guides him through the museum and its basement, again all in a single moving take. The seemingly endless basement is shot entirely against a black background, though at one point images of the two seemingly accompany them in the background.

Despite the grim subject matter, as in Fish and Cat, there is a good deal of self-conscious humor in Careless Crime. Little jokes are made about movies, and especially arty ones, as when a minor couple in the targeted cinema waits for the film to start. The woman looks at the screen (perhaps at a trailer?) and remarks, “I hate any film that has this laurel sign on it.” The reference is to one of the primary institutions of the international art cinema:

Is Mokri twitting the festival for not having chosen to show his films? As is now clear, his film’s repeat presence at Venice turned out to be an advantage in the long run. Although Careless Crime did not win a prize in the Horizonti competition, outside the official festival it received the FIPRESCI award for the best screenplay. Perhaps, when it finally becomes possible to return to the VIFF in person, we will see the next Mokri film and struggle not to be puzzled.

Thanks, as ever, to Alberto Barbera, Paolo Lughi, Savina Neirotti, Peter Cowie, and Michela Lazzarin for their assistance this year and in the past.

You can watch an extract of the Biennale press conference for Apples. The director discusses it in this Variety interview.

Our earlier entries on the Venice festival are here.

Apples (2020).

Beach blanket ballads: SUN & SEA (MARINA)

Sun & Sea (Marina) (Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė, 2019).

DB here:

Excitement, shock, tension, maudlin sentiment–these and other emotional qualities are pretty common in artworks. But how often do we get what I’m forced to call anxious languor? That seems to me the dominant expressive quality of the remarkable Lithuanian opera Sun & Sea (Marina), which won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at the Venice Biennale.

It’s not a film, but having read about it before going to the Mostra, I was keen to see it. Kristin and I were not disappointed. It’s the work of director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, writer Vaiva Grainytė, and composer Lina Lapelytė. You can watch extracts here and here and here.

Video clips, or indeed a full-length record, can’t capture this unique spectacle. And of course it set me thinking about film.

Duet in the sun

Sun & Sea: Marina portrays a group of people at the beach. Instead of being mounted on a stage, the action, such as it is, takes place on a ground floor of a warehouse. You view the ensemble from catwalks above. On the sand below are pastel beach blankets, personal belongings, and some litter. Thirteen singers and some civilians lie reading or snoozing or listening to cellphones. A woman deals out Tarot cards. There’s a little boy playing in the sand, dudes tossing a frisbee or playing badminton, and occasionally a couple’s dog needs walking. The dog barks from time to time.

The piece lasts about seventy minutes, recycled so you can enter at any point. At the Biennale, it was initially open only one day a week, but later you could attend on either Wednesday or Saturday. The queue wasn’t impossible; I think we waited about half an hour.

The looped nature of the presentation works against there being a plot, and there’s scarcely any characterization. The libretto identifies the Wealthy Mommy, the Volcano Couple, the Workaholic, the 3D Sisters (twins), and others, but when you’re watching it, you’re much more aware that this is about particular bodies in a specific space.

The music, in the lyrical minimalist vein, consists mostly of arias, characters’ soliloquies backed up choral passages. There’s an organ ostinato recalling Philip Glass and tunes that reminded me of the lilting faux-naīveté of Meredith Monk. The rhythm is alternately solemn and bouncy, the phrases are brief, and the mood of the whole score seems summed up in the soaring Chanson of Too Much Sun:

My eyelids are heavy,/ My head is dizzy,/ Light and empty body./ There’s no water left in the bottle.

Some of the arias, like this one, report thoughts caught in the moment. The first and last songs are Sunscreen Bossa Novas, sung by a middle-aged woman worrying about protecting her skin. Another woman complains about dogshit and spilled beer in the sand. One of the most moving passages is the Chanson of Admiration, a breathy soprano solo:

What a sky, just look, so clear!/ Not a single cloud,/ What is there?–seagulls or terns?/ I can never tell./ O la vida/ La vida…

Other characters provide dramatic monologues. The Workaholic sings the Song of Exhaustion, an admission that even relaxing, he can’t slow down. (“My colleagues will look down on me. . . . I’ll become a loser in my own eyes.”) Still others tell stories. A woman recalls her husband’s death while swimming with his girlfriend. A house guest learns that his host has a brain tumor. A couple talks about catching an early-morning flight. Most abstractly, the Philosopher thinks about globalization: how strange to play chess (a game of Indian origin) on the beach while eating dates from Iran and wearing a swimsuit made in China.

Other characters provide dramatic monologues. The Workaholic sings the Song of Exhaustion, an admission that even relaxing, he can’t slow down. (“My colleagues will look down on me. . . . I’ll become a loser in my own eyes.”) Still others tell stories. A woman recalls her husband’s death while swimming with his girlfriend. A house guest learns that his host has a brain tumor. A couple talks about catching an early-morning flight. Most abstractly, the Philosopher thinks about globalization: how strange to play chess (a game of Indian origin) on the beach while eating dates from Iran and wearing a swimsuit made in China.

Sun & Sea (Marina) has been considered a commentary about our poisoning the planet, and the booklet included with the LP of the score includes essays about climate change. But the opera as staged invokes the crisis obliquely and poetically. One passage notes that the seasons are out of joint at Grandma’s farmhouse, with frost and snow in May and Easter weather during Christmas. It’s presented not as a warning but as a puzzling development. A recurring line in the songs is “Not a single climatologist predicted/ A scenario like this,” and it’s applied to love affairs as well as volcanic eruptions. The crises of the Anthropocene era are refracted through personal relationships.

Environmental degradation is registered through the sensibility of drowsy vacationers. The twin sisters are distressed to learn that coral and fish will perish, but they console themselves that a 3D printer will produce enduring copies of everything, including the girls themselves. (“3D Me lives forever.”) Even pollution right under your nose is filtered through the dazzling torpor of a day at the beach. One of the loveliest songs invites us to imagine that the sea is acquiring new beauty.

Rose-colored dresses flutter;/ Jellyfish dance along in pairs–/ With emerald-colored bags,/ Bottles and red bottle-caps./ O the sea never had so much color!

In all, though you might register some perturbations in the ecosystem, you come away from lolling on the sand feeling pretty good.

After vacation,/ Your hair shines,/ Your eyes glitter,/ Everything is fine.

Eisenstein on the beach

What about cinema? Seeing something so resolutely presentational makes you think about what film can’t do. The online videos only hint at the decentered, dispersed quality of the opera. Some of the action takes place directly under the catwalks, so you can’t take in the ensemble at a single glance. We had to move around to get a sense of what had been happening underneath us.

Just as important, nobody in the audience is significantly closer to the stage than anybody else. Cinema of course has what Noël Carroll has called variable framing, the ability to change the scale of the material in the image (through cutting, camera movement, zooming, optical effects, digital postproduction). Even in proscenium theatre, the people in the orchestra see more details than those in the balcony. But Sun & Sea (Marina) keeps everybody pretty much at the same distance from the spectacle. We can fixate on some figures rather than others, and we can enlarge them artificially via the zoom on our cellphones, but the naked eye has to take in the whole thing at once, all the time. And even that’s not really the whole thing.

The sense of dispersed action is strengthened by the surround-sound speakers. They delocalize each voice. You have to search the array of bodies to find the soloist, and when a song is tossed from singer to singer it scrambles your attention. This might remind a cinéphile of Jacques Tati’s compositional strategies, particularly in Play Time, where long shots coax us to scan the image to find a sound’s source. But at least Tati had a more restrictive frame. Sun & Sea (Marina) plants us in a three-dimensional field with only partial access to the entire scene.

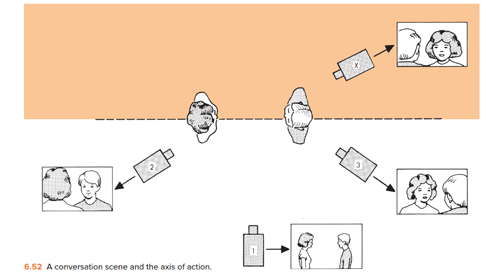

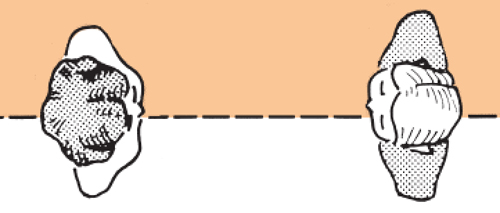

That access is, of course, a very unusual one. When I was first studying classic continuity editing, with the 180-degree rule and matches on action and all the rest, I wondered: Would that system work if the camera were pointing straight down at the actors? That is, what if we constructed a whole story from variants of the bird’s-eye view we use to diagram spatial layouts? Instead of this:

We’d have movies with shots like this.

We’d apparently lose the eyeline match, at least! We’d also have to distinguish characters in unusual ways, by hats and hairstyles and maybe boutonnieres. But I was assuming a drama in which people moved around on foot and had face-to-face encounters. Sun & Sea (Marina) suggests that another way to build a vertically viewed spectacle is to show people sprawled out on belly, back, or side–postures motivated by the beach setting.

Then perhaps we could, through editing, create “reverse angles” from straight down. Or couldn’t we?

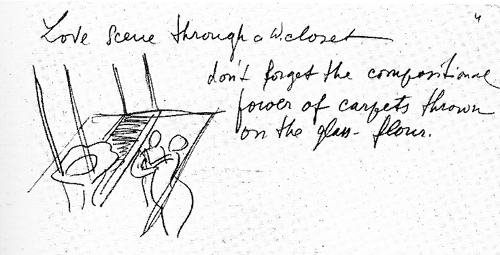

Actually, as usual, Eisenstein was there ahead of us, in his plans for The Glass House, a film set in a skyscraper made of glass. The transparent walls would let us see what’s happening next door, while the floors would create a stacked space, presenting actions from more or less straight down. Naughty as he was, he even conceived a “Love scene through a water closet.”

In one note, he called the film’s view “A Hovering Space”–not a bad description of what we see in Sun & Sea (Marina).

I’m still thinking about this remarkable piece of work, about the anxious languor it projects and its ways of building a scattered scene out of microactions. But I’m also enjoying remembering the sheer sensuous pleasure of it. I hope that somehow I get to see it again. I hope you can too.

Our visit to the Biennale was made possible by the generous invitation of Peter Cowie, Savina Neirotti, Paolo Baratta, and Alberto Barbera. As ever, we appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich. Michael Philips of the Chicago Tribune and Keith Simanton, Senior Film Editor and Content Manager of IMDB, accompanied us to the show and proved fine company.

There’s a very informative interview with the artists (who have been friends since childhood) here at BarbART. It includes footage from their earlier collaboration, Have a Good Day! Background on the artists can be found at Neon Realism. The score is available as an LP. It includes a custom code for downloading an mp3 file. Beware: Many earworms wriggle within.

Of course Sun & Sea (Marina) reminds you of another Tati masterpiece, M. Hulot’s Holiday. Kristin long ago wrote a careful analysis of that film with a title I might have borrowed for this: “Boredom at the Beach.” It’s in her collection Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. Also on Tati: Watch for Malcolm Turvey’s excellent forthcoming study Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism.

The diagram of the 180-degree editing system comes from Film Art: An Introduction. Photos in this entry by DB.

P.S. 15 September 2021: Sun & Sea (Marina) is coming to the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019).

Venice 2019: Political dramas, allegorical and real-life

Waiting for the Barbarians (2019).

Kristin here:

The 76th Venice International Film Festival is over, but I have two films yet to blog about. This will be our final entry. Soon we’re both off to the other VIFF, the Vancouver International Film Festival, from which we will of course be blogging.

Waiting for the Barbarians

I was particularly looking forward to this film, since I admire Ciro Guerra’s two previous features, Embrace of the Serpent (2015) and Birds of Passage (2018). It was rather surprising that Guerra should have a new film premiering only a year after Birds of Passage, especially since both are in their own ways epics in relation to most other art films. The fact that it stars the great stage and screen actor Mark Rylance was another factor in its favor.

Oddly enough, the morning press screenings and evening red-carpet screening of Waiting for the Barbarians were relegated to the penultimate day of the festival, Friday, September 6. It was the last of the films in competition to be shown, with The Burnt Orange Heresy (in the festival’s Fuori Concorso thread) the closing film on Saturday. By that point, quite a few of the foreign-press members had departed for Toronto or elsewhere. The Friday afternoon press conference, despite including Johnny Depp on the panel (above), was SRO, but there was no immense queue to get and and very few standing at the sides or sitting on the central stairs, as usually happens when big stars are present.

Overall the film has received lukewarm reviews, with a few more praising pieces mixed in. Both David and I, however, found it riveting. It deals with the unnamed Magistrate (Rylance), who rules a fort community on the border of a desert landscape inhabited by nomadic tribes. The Magistrate controls the place with a loose rein, meting out mild punishments for what he perceives as minor infractions by the local population. He seems content, excavating for ancient wooden rods inscribed with undeciphered texts and apparently has a relationship with a sympathetic local prostitute. He seems friendly with the people under his care and has taken the trouble to learn their language.

The countries which this border area separate are never identified and are clearly fictional places serving to portray the horrors of colonial domination by western nations. Clearly the white officials and soldiers in the film are not intended to be British. The flags on display bear no resemblance to the Union Jack and the costumes are not British. The local nomads speak Mongolian, and the main female character, referred to only as “the Girl,” is played by Gana Bayarsaiknan, a Mongolian performer.

The conflict is set moving by the arrival of Colonel Joll, an ominous figure in black, sporting bizarre dark glasses with frames of twisted wire (in the background of the frame at the top). His suggestion that he will use “pressure” to force the locals to confess their crimes turns out to be a considerable understatement. Joll ventures a little way into the the territory of those he calls “the barbarians.” He claims to turn up evidence that the local people are plotting to attack the colonial forces along the border. He has discovered this evidence though torture.

Much more description would provide too many spoilers. In general, the Magistrate tries to reason Joll and his confederates out of their plans. He also frees prisoners and nurses the native girl, who has also been tortured, back to a semblance of health. Eventually he finds himself driven to rebellion.

The film, with exteriors shot in Morocco, creates a vivid sense of a fortress community isolated from the world, and the cinematography as the Magistrate leads a small group to try and return the Girl to her people is austerely beautiful.

So far all the release dates for Waiting for the Barbarians are for festivals, including the London Film Festival. Whether it will be released in the US, as Guerra’s two previous films were, is unknown. I would suggest giving it a chance, despite some lackluster reviews. It’s another film that would lose much of its effect when streamed on a small screen.

Adults in the Room

Each year a small number of celebrities receive special awards, essentially salutes to long and fruitful careers. This year the main honors went to Pedro Almodóvar, Julie Andrews, and Costa-Gavras. We didn’t catch the awards ceremonies themselves, and the Amodóvar and Andrews ceremonies were followed by classic films of their past (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Victor Victoria respectively). Costa-Gavras’ career started as an assistant director to René Clair, René Clément, Henri Verneuil, Jacques Demy, Marcel Ophüls, Jean Giono, and Jean Becker before beginning to direct on his own. Apart from his numerous features, perhaps most notably Z (1969), he has been president of the Cinémathèque Française since 2007.

Now, at age 86, he brought with him a new feature, Adults in the Room, a dramatization of the tensions and strategies of the politicians and diplomats struggling to find a solution to the Greek financial crisis.

As in most such films, the actors have been chosen for their resemblance to the historical figures. In the upper of the two images below, for example, Josiane Pinson plays Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, and Daan Schuurmans is Jeroen Dijsselbloemm, president of the Eurogroup.

The film begins with the unlikely election of a leftist government in Greece (the Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza) in January of 2015. The film sticks largely to the point of view of Yanis Varaufakis, the fiercely dogged Finance Minister. His memoirs of the struggle to refinance Greece’s overwhelming debt and to keep Greece from being expelled from the European Union were the basis for the script by Costa-Gavras.

Remarkably, Costa-Gavras follows the events through an almost unbroken series of conversation scenes. These center on clashes between Varaufakis and Greece’s Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, and on stormy meetings involving representatives of the Eurogroup and the infamous “Troika” (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund). The Troika faction, which had bailed out the Greeks and insisted on disastrous austerity measures, absolutely refuses Greece’s demand that the loans stop and that the debt be devalued to a viable level.

This does not begin to convey the complexity of the Greek crisis, but Costa-Gavras manages to create suspense, whether or not we can actually follow exactly what is going on. There are moments when Varaufakis’ negotiation strategies are withheld from us, and we are as puzzled as the officials watching them from across the room, as in this glance-POV cut:

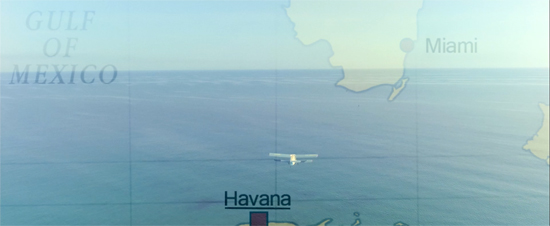

These meetings are linked primarily by shots establishing the various cities in which these complex and fruitless meetings take place. Often superimposed titles reveal the locations, as when the Greek Prime Minister arrives in Brussels for one such meeting (see bottom).

By the end we are not left with a thorough grasp of the intricacies of these events, which would hardly be possible for a crisis that started around 2009 and is still going on. Still, we gain a somewhat better understanding than we are likely to have on the basis of news stories stretched sporadically over over so many years. We are also left indignant at the determination of the Troika to persist in the very policies that drove Greece deeper and deeper into debt. Some have found the film tedious in its intense focus on meetings and strategies. Others I talked to after the press screenings found it fascinating. Certainly the film and its source book have chosen the brief period of the crisis (about six months) that shows most clearly and dramatically what Greece faced from the rest of the EU and why its crisis still has not ended.

For one final time this year, thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Adults in the Room (2019).

Telling the big story: Network narratives at Venice 2019

The Laundromat (2019).

DB here:

Every now and then I wonder whether network narratives, to revert to the term I coined a while back, have faded from the scene. Although there are some examples earlier in film history, that storytelling model had a sustained burst after Altman popularized it in Nashville (1975). Other filmmakers took it up, especially in the 1990s (Before the Rain, Exotica, Go, Pulp Fiction, etc.) and the 2000s (Babel, Dog Days, Love Actually). I don’t seem to see so many nowadays, and the almost universal loathing greeting Life Itself (2018) might seem to indicate that a tale relying on remote connections and unexpected convergences had run its course.

Surprising, then, to see three items at Venice that rely to a degree on the network narrative format. Each is based on a nonfiction book aiming to reveal the dynamics of a large-scale process. In each film, process becomes a framework for personal stories and converging fates.

Wasps in the Caribbean

Olivier Assayas’s Wasp Network isn’t as far-reaching as the title implies. It concentrates on two couples and one individual caught up in 1990s spying. When René Gonzales, a pilot, defects to Florida, he seems to be seeking freedom and a new life working with Cuban exiles to destabilize Castro’s regime. Branded a traitor, he leaves behind a wife and daughter who must bear social opprobrium. Actually, he is a Cuban agent, part of the “Wasp Network” that will infiltrate the anti-Castro forces.

Another exile, Juan Pablo Roque, works with the Network, but he is also leading a double life–one quite different from René’s. Just as René’s sacrifice wrecks his relation with his family, the headstrong Juan Pablo jeopardizes his relation to his lover Ana Margarita. Both men are linked to Gerardo Hernandez, who coordinates the Network.

As in most spy stories, we’re led to discover double agents and surprise alliances, as well as the conventional emphasis on the personal cost of espionage. As the film goes along, that emphasis becomes stronger; scenes tracing the tactics of the anti-Castro forces (such as invading Cuban airspace to drop leaflets) give way to long confrontations between couples and the efforts of Rene’s wife Olga to unite with him in the US.

Because network plots need to fan out across many characters, filmmakers often break up the linearity of time. In Wasp Network, the reunion of the two major defectors, Juan Pablo and René, is followed by a passionate scene of Olga being defeated by Cuban bureaucracy. Abruptly the plot skips back four years to introduce Gerardo, and his career as a double agent is summarized. A montage, complete with a narrator’s voice-over, links the three men in the years 1990-1992. Then, back in the present, Gerardo meets with Olga to reveal that René is a patriot, not a traitor.

Visually, the film is surprisingly ordinary, I thought, sort of standard TV. If you like over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot, there’s plenty here for you.

Assayas garnishes his reverse angles with alternating push-ins, a technique that has become a bit hackneyed since John McTiernan’s skillful use of it.

The film compels some interest by virtue of its origins. Based on the FBI case against the “Cuban Five” and the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, it employs vintage broadcast news coverage cut in for expository purposes. I had known almost nothing of this historical episode, and thanks to the cooperation of Cuban authorities Assayas benefits from showing a story we Americans seldom see. Still, by concentrating on only a few characters and having them played by Édgar Ramírez, Penélope Cruz, and Gael García Bernal, whose presence demands extensive scenes, the larger dynamic of the Wasp Network fades into the background. Despite its title, maybe it’s only a borderline case of a network narrative.

Coke ZeroZeroZero

ZeroZeroZero is also based on journalistic reportage, in this case Roberto Saviano’s book of the same title. (An earlier Saviano true-crime investigation is the source of the 2008 film Gomorrah, another network narrative.) The subtitle of his book–Look at Cocaine and All You See Is Powder. Look Through Cocaine and You See the World–suggests the vast ambition of his project. From the book Sky, CanalPlus, and Amazon Prime have developed an eight-part series to be broadcast and streamed in 2020.

Since I’m not the world’s biggest TV consumer, I wasn’t interested until I read the presskit, which promises something sweeping.

The series follows the journey of a cocaine shipment from the moment a powerful cartel of Italian criminals decides to buy it until the cargo is delivered and paid for. Through its characters’ stories, the series explains the mechanisms by which the illegal economy becomes part of the legal economy and how both are linked to a ruthless logic of power and control affecting people’s lives and relationships.

The prospect of following a coke-packed container as it passes through various hands appealed to me. I enjoy circulating-object plots like Winchester 73 and The Red Violin, as well as those 1920s Soviet Constructivist “biographies of things” (such as Ilya Ehrenberg’s Life of the Automobile).

ZeroZeroZero, though, isn’t quite that sort of thing. Judging by the first and second episodes, the only ones screened at Venice, this will be more conventional. The plot shifts among dramas within groups of stakeholders in the shipment. We see the power struggle in an Italian crime family, with a son aiming to usurp his grandfather. There’s another family drama in New Orleans, where a ruthless shipping-company owner insists, against his son’s and daughter’s resistance, on booking the cargo. In Mexico, a corrupt special forces sergeant works behind the scenes to assure that the shipment will not be disturbed.

The narration cuts among these storylines until, at the end of episode 2, the cargo embarks on the seas. Doubtless the remaining episodes will ramify into other story lines, but I’d expect at least the Italian and American ones to be on tap throughout–if only to maintain the interest of streamers’ European and US audiences.

The film was directed and co-written by Stefano Sollima, who has done several TV dramas as well as the feature film Sicario–Day of the Soldado. ZeroZeroZero certainly had a higher-gloss look than Wasp Network, with dramatic lighting and elaborate action scenes. One of these, a police attack on the big meeting of the stakeholders, is replayed from different character viewpoints in the two episodes. Like Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero amplifies its expanding network through time-shifting, and this attack is revealed to be a node, a point of convergence among the three main groups of characters. Given current TV’s fascination with scrambled time schemes, I’d expect other nodes and replays to emerge in the course of the series.

Capitals of capital

Eisenstein planned to make a film of Marx’s Capital. He would have used his montage editing methods to survey an economic system–without benefit of individualized protagonists. In The Laundromat Stephen Soderbergh has tried to do something akin to this, but like most filmmakers he’s obliged to personalize his drama (as he did in Traffic and Contagion). Soderbergh has compared the film to Dr. Strangelove, largely because of the need to make a devastating situation entertaining. But I think his film recalls Strangelove as well in its emphasis on villains who get caught up in the insanely complicated system they create.

Mossack Fonseca was a law firm in Panama that specialized in tax evasion. It registered over 300,000 companies, many of which were shell entities that enabled money laundering and fraud. The firm had subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Hong Kong, Switzerland, and other countries. In 2016, German investigative journalists published 11.5 million internal documents known as the Panama Papers, mostly centering on Mossack Fonseca. As the journalists explain:

Clients can buy an anonymous company for as little as USD 1,000. However, at this price it is just an empty shell. For an extra fee, Mossack Fonseca provides a sham director and, if desired, conceals the company’s true shareholder. The result is an offshore company whose true purpose and ownership structure is indecipherable from the outside.

Despite its vast scale, the firm represented at most ten percent of the global market of offshore finagling.

Tax havens and shell companies are more or less legal. What brought down the company was the breach of confidentiality. In addition, the possibility of fraud hovered over the big names revealed as beneficiaries. Politicians throughout Europe and China were named, as were filmmakers Jackie Chan and Pedro Almodóvar. International villains associated with Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin moved money through Mossack Fonseca; a Russian cellist had holdings of $2 billion. After the leaks, the rich couldn’t trust Mossack Fonseca to keep their secrets.

Building on Jake Bernstein’s book Secrecy World, Soderbergh and screenwriter Scott Z. Burns have concocted a sweeping tale of how the rich are very, very, very different from you and me. But in scale, the network they’re surveying dwarfs the Wasps and the voyage of a coke shipment. How do you convey the vastness of an alternative financial system?

The film’s pop-Brechtian mode of presentation will earn comparisons to The Big Short, but here instead of one-off celebrity tutors (Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain) we get the chattering rogues themselves, Jürgen Mossack (Gary Oldman) and Ramón Fonseca (Antonio Banderas). Their to-camera accounts of “fairy tales that actually happened” settle into a block construction, five chapters “based on actual secrets.”

The first chapter title, “The Meek Are Screwed,” provides an emblematic case of how the little people are connected with this network of virtual money. Chief among those Meek is Ellen Martin (Meryl Streep), whose husband Joe is drowned when a tour boat capsizes.

Hoping to have her grief assuaged by an insurance settlement, she learns that one isn’t forthcoming because the boat company bought a worthless policy from a shell company. The film’s first two chapters follow her efforts to find someone responsible. She finally tracks down a fraudster named Boncamper, a Mossack Fonseca figurehead who has grown rich (and accumulated two families) simply by signing thousands of documents.

Having shown how the shell-company shuffle affects ordinary folks, the film moves on to the high and mighty. One chapter traces the backstory of the company, another shows how an extraordinarily rich family uses the system to one-up each other, and a final chapter depicts murder among the Chinese plutocracy. The fourth block, illustrating the lesson of “Bribery 101,” is especially juicy in showing a father using bearer bonds to force his daughter to keep silent about his extramarital affair. As Marx and Eisenstein would expect, economic relations seep into personal ones. Bribery is all in the family.

The Laundromat’s breezy, self-righteous impresarios cast a comic tone over everything. Even the murder doesn’t seem awful, considering the victim’s own corruption. Only at the end does indignation emerge in a twist. Ellen, almost forgotten for the last half-hour, reappears in a new guise and takes over the narration from the villains. An agitprop ending reminds us that the capital of money laundering may well be the US, where Nevada, Wyoming, and above all Delaware play a role comparable to the Caribbean. Soderbergh and Burns (who confess to having offshore stashes themselves) end by firmly snagging their American audience in the colossal spiderwebs of global capital.

Nearly every narrative involves a social network of some size, even if it’s only a family. The most thoroughgoing network plots provide us roughly equal attachments to many viewpoints. The film demotes individual protagonists, in favor of revealing x degrees of separation among several individuals. Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero, and The Laundromat don’t have the complexity of the network narratives of earlier years, but they serve to remind us that the network schema can be tweaked to suit the needs of particular creative projects.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

For more on network narratives, see Chapter 7, “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema. Jeff Smith considers Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood as a network narrative, and earlier entries (such as here and here) develop the idea as well.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

ZeroZeroZero (2020).