Archive for the 'Festivals: Venice' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch

DB here:

All artists rely on predecessors in one way or another. True, at any moment the artist may confront a dizzying array of options; there are a lot of models out there. And sometimes artists work against received traditions rather than building on them. (Usually, though, those assaults on tradition borrow from other traditions, often minor ones.)

Anyhow, it’s a good first move to assume that any artwork we encounter owes something to forebears. If we want to understand continuity and change in film history, then, we can try to know something about genes, styles, received habits, work routines, and other ongoing pressures on moviemakers.

Schema and revision

Favorites of the Moon (Iosseliani, 1984).

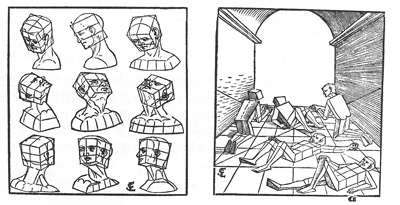

Among the strategies for making sense of a given film or filmmakers, one I’ve found useful I’ve swiped from E. H. Gombrich. In Art and Illusion, he wrote of schema and revision as one way of thinking about an artist’s ties to tradition. A schema is a pattern that has proven reliable for art-making in the past. His examples are the geometrical templates that became part of the training of Western European artists.

Gombrich suggests that artists adapt the schemas to the purposes at hand–new tasks, or the urge to capture aspects of reality that their predecessors missed.

Once a hack has learned how to make the image of a tolerably convincing head, he may be tempted to use this standard formula for the rest of his days, merely adding just such distinguishing features as will mark the admiral or the court beauty. But obviously once he is in possession of a standard head, he can also use it as a starting point for corrections, to measure all individual deviations against it. He may first draw it on his canvas or in his mind, not in order to complete it, but to match it against the sitter’s head and enter the differences onto his schema.

Hence the Gombrichian slogan: Making precedes matching. You render a version of visual reality in and through the forms bequeathed to you by tradition, adjusting them as you may need.

In film, I suggested in On the History of Film Style, we have several stylistic schemas. A prototype would be shot/ reverse-shot staging and cutting. You can replicate the schema, just running it again, as most filmmakers do. (All those damn shoulders.) You can revise it, as Ozu, Bresson, and other filmmakers did. You can adapt it to the long take, as Hitchcock and Iñarritu did. Or you can reject it, as Tati and Iosseliani did with their extreme long-shots. Iosseliani: “As soon as I see a film that begins with a series of shots and reverse shots, with lots of dialogue and well-known actors, I leave the room immediately. That’s not the work of a film artist.”

Stylistic schemas are perhaps the easiest to spot; when they cluster, we get something like a style in a general sense, such as continuity editing, or more recently what I’ve called “intensified continuity.” Even minor genres, like long-take lipdubs, have their own schemas. And revisions are ongoing. In mother! Darren Aronofsky fills the “free-camera,” run-and-gun handheld style, which usually favors medium shots, with extreme close-ups that put menacing, barely identifiable action in out-of-focus backgrounds. The result can be seen as a revision of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reframings on display in the Bourne films.

There are schemas for narrative too. At the broadest level, the sacred Three-Act Structure can be thought of as a macro-schema; so too the more fleshed-out Four-Part Structure Kristin has proposed. In my new book Reinventing Hollywood, I invoke the schema/revision idea to talk about more specific narrative strategies of the 1940s. Examples are the flashback plot, with a shuttling between present and past, and the network narrative, which brings friends, kinfolk, and strangers together in a limited time or space.

Watching Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) again at the Venice Film Festival reminded me that the schema/revision process can take place not just between the filmmaker and tradition but within the work of a director. Once a director develops a “signature style,” that too can be reworked, refined, stretched, or even repudiated. Griffith recast his characteristic last-minute-rescue crosscutting pattern, once by making the rescue too late (Death’s Marathon), and once by multiplying it by four (Intolerance). Ozu not only revised Hollywood continuity principles, but then tweaked and played games with his customized version. Arguably, Hitchcock did the same with his refined point-of-view structures and man-on-the-run plot patterns.

In the Lubitsch case I’m considering, we have a very tiny piece of schema revision, but one that shows him to be a fastidious creator. Having sculpted a small moment one way, he extracted its principles and remade it, for other purposes in another film.

The grapes

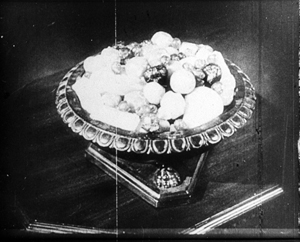

The street singer Rosita is in the palace waiting for the king. At first she’s awed by the scale of the room, but then she spies a bowl of candied fruit on a little table. As often happens in Lubitsch’s American silents., this plays out through eyeline cutting.

Rosita heads out of her shot and a frame-edge cut brings her to the table. She drifts past the fruit, eyeing it, and now the sequence’s rhythm is established.

When Rosita leaves the frame, the camera holds on the table and the fruit bowl.

After a beat, she strolls into the frame moving right, pointedly ignoring the fruit. She goes out of frame and Lubitsch holds on the bowl.

Then Rosita comes in from offscreen right and plucks a grape as she passes through the frame. Lubitsch holds the empty shot.

Rosita comes in again from the left, snags another grape, and walks out frame right.

After another beat, she thrusts back into the frame and starts to dig into the fruit.

She’s hungry but afraid of being caught, so she swipes the food as casually as she can. Once she thinks she’s not being watched, she can take what she wants.

Instead of cutting the action up, Lubitsch holds the shot and makes a sort of contract with the viewer. The gag depends on simple spatial continuity; we know where Rosita is when she’s out of frame, so we can anticipate her coming back in and wonder what she’ll do on the next pass. By holding on the table, the camera “knows” she’s coming back and waits for her; the bowl draws her like a magnet. We enjoy the game of expectation Lubitsch has set up.

Simple as it is, this passage shows the patterned nature of a stylistic schema. You could plug different things into that pattern—a bed rather than a table, a gun on a counter, a detective casually looking for clues—but as long as you set up the pause holding on the “empty” frame as the actor passed through to and fro, we’d have a recognizable schema. It’s one that other filmmakers could use.

Or one that Lubitsch himself could cleverly revise. If the Rosita version builds a mild sort of suspense, what if we added a dose of surprise? That’s what happens in Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

The drawer

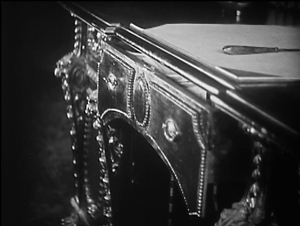

Lord Darlington, hoping to drive a wedge between Lady Windermere and her husband, suggests that she look for a check Lord W wrote to the mysterious Mrs. Erlynne. Lady W walks into the study and pauses at her husband’s desk, then goes to sit in a chair nearby.

Like Rosita studying the fruitbowl, she eyes the desk drawer holding the check.

She rises and, thanks to another frame-edge cut, walks to the desk. But thinking the better of it, she leaves the frame, going out left.

The camera stays on the desk. Pause.

Suddenly Lady W bursts into the frame, but from the right side.

Lubitsch, who understood the rules of continuity better than almost anybody, knew perfectly well that she should have come back in from the left. The actor had to go around behind the camera in order to come in from this “impossible” angle. We’d be startled to some extent if Lady W had suddenly burst in from the left, but now the effect is amplified by the unpredictable entrance from the right. To spatial suspense, holding on the desk, Lubitsch has added spatial surprise.

Interestingly, there’s another anomaly here: the early POV shot of the drawer. It represents what Lady W sees, but from the opposite angle, from the “other side” of the desk. A shot respecting her vantage point would have looked like this.

Since this is a silent film, even if Lubitsch had made a mistake during filming, the shot could have been flipped in postproduction to look correct. It’s just possible that this “wrong” POV shot is another schema revision–one that anticipates Lady W’s “wrong” reentry into the desk shot. This possibility is strengthened soon afterward when Lady W tries to open the drawer, in a framing that shows the “correct” angle.

And soon afterward, when Lord Windermere joins his wife, he will look at the drawer from the “correct” angle as well.

A spare take of his POV shot could have replaced Lady W’s mismatched one. (Though the fastidious Lubitsch gives us a slightly different angle from Lady W’s, one corresponding to the position of Lord W). It seems likely, then, that Lubitsch simply wanted Lady W’s odd POV shot. Perhaps he saw it as a cryptic hint that something important was about to happen on the other side of the desk, where Lady W will pop in.

With Lubitsch, we’re always getting into such pictorial niceties. In any case, having tried out the “waiting camera” schema in Rosita, garnished it with predictable frame entrances and exits, Lubitsch revised the schema to create a different effect. He knew that audiences would expect Lady W to reenter the way Rosita did, and he exploited our expectations to yield a bump of surprise–one that increases the expressive effect of her pouncing on her husband’s secret.

More generally, the concept of schema/revision seems to me a useful tool for studying a filmmaker’s ties to tradition, as well as his or her developing personal style. This is not to mention the role of rivalry, another important pressure for continuity and change in film craft. Once a schema is out there, people can compete for ways to revise it. But that’s a topic for another day.

My frames from Rosita are from the standard, rather bad surviving print. It has recently been restored by the Museum of Modern Art under the auspices of Dave Kehr, and the new version looks very fine. More information here.

The illustration of heads comes from Erhard Schön’s manual of 1538, reproduced in Gombrich’s Art and Illusion (Princeton University Press, 1960), p. 159; my quotation comes from p. 172.

The quotation from Iosseliani comes from “Iosseliani on Iosseliani,” in The 24th Hong Kong International Film Festival Catalogue (Hong Kong: Urban Council, 2000), p. 138.

Kristin provides close analysis of Lubitsch’s silent film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American Film after World War I, available online here. I discuss this sequence from Lady Windermere in more detail in Chapter 9 of Narration in the Fiction Film. But when I wrote that, I hadn’t seen Rosita. I consider how Ozu varied his bespoke version of continuity editing in Chapters 5 and 6 of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online here.

Fruitbowl, Mary Pickford, Ernst Lubitsch, and Holbrook Blinn on the set of Rosita.

Venice 2017: Crimes, no misdemeanors

Outrage Coda (2017).

DB here:

The period from 1985-1995 was a sterling era for world cinema. Whatever you think of Hollywood of that time (it wasn’t as bad as they say), American independent film was flourishing then. On the global stage, things were even better, as witness the rising careers of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang Dechang, Jackie Chan, Tsui Hark, Abbas Kiarostami, and Wong Kar-wai. It was exhilarating to watch these and other directors turn out splendid work like City of Sadness, A Brighter Summer Day, Police Story, Project A Part II, Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, The Blade, Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Through the Olive Trees, Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express, and more.

That’s not all. In Hong Kong, John Woo was redefining the urban action film with the flamboyant, romantic A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989), and Hard-Boiled (1992). In Japan, a standup comedian known as “Beat” Takeshi Kitano took over the helming of a crime thriller, Violent Cop (1989), and decided to continue directing, turning out not only the bored-hitman saga Sonatine (1993) but also the lyrical A Scene at the Sea (1991). Another Japanese filmmaker, Kore-eda Hirokazu, launched his career with the meditative, Hou-ish Maborosi (1995).

I loved these films, and still do. Woo and Kitano belong to an older generation (mine, actually), while Kore-eda is younger. None has gone away. All came to Venice 74 with murder on their minds.

Confessed, but to what?

The Third Murder (2017).

The Third Murder (Sandome no satsujin) is Kore-eda’s first venture into the crime genre, and he brings to it the same steady humanism we find in all his work. I’ve elsewhere recorded my uneasiness with his current visual style. Unlike the grave, long-take Maborosi, his films of the last decade or so are pictorially conventional, even academic, with their big close-ups, needlessly sidling camera moves, and other features of intensified continuity. But he continues to take narrative risks, and his almost Renoirian willingness to see many moral and psychological points of view make every film fairly gripping.

The Third Murder begins abruptly. An unseen victim is bludgeoned and the body is burned. The killer is the man we’ll come to know as Misumi. He’s captured. Like 99% of people charged with crimes in Japan, he readily confesses. His lawyers face only the question of sentencing: Should they try to get him life imprisonment rather than execution? When one attorney, Shigemori, decides to investigate more closely, he peels back layers of uncertainty about the circumstances, the victim, and the motive(s). Like many a victim in crime fiction, this businessman needed killing.

Following conventions of the investigative procedural, the plot relies on secrets, viewpoint shifts that drop hints, twists that frustrate simple understanding, and flashbacks that make us question what we thought we knew. Shooting in anamorphic widescreen, Kore-eda produces some extreme framings reminiscent of Kurosawa’s High and Low, one of the films he studied while preparing the project. Despite occasionally flashy moments, it’s a soberly told tale, emphasizing characterization and social critique. By the end, Misumi acquires a weary, radiant dignity, while entrepreneurial capitalism and the justice system are revealed as compromised. (In this respect it recalls I Just Didn’t Do It, 2007, by another 80s-90s director, Suo Masayuki.) In moving to the sordid terrain of the crime story, The Third Murder shows that Kore-eda hasn’t given up his sympathetic probing of human nature and his praise for un-grandiose self-sacrifice.

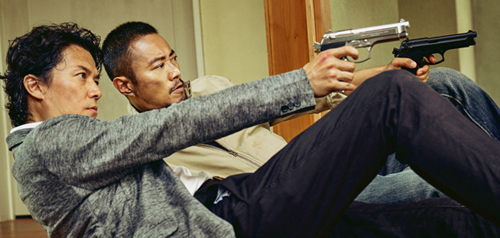

Bullets to the head and elsewhere

Manhunt (2017).

Sober and un-grandiose don’t apply to Manhunt (Zhuibu), John Woo’s return to bloody brotherhood and outsize ordnance. After prestige Hollywood efforts like Windtalkers (2002), the nationalistic costume picture Red Cliff (2008-2009), and the ensemble-disaster movie The Crossing (2014-2015), Woo is back with what he does best: showing many people firing many guns, dodging bullets (bad guys have bad aim), diving for cover in slow-motion, floating through hazes of cordite, and instantly recovering from wounds that would finish off you and me. These characters also run endlessly, hop into the path of trains, overturn vehicles, and set loose unconscionable numbers of pigeons.

1990s Hong Kong directors could make cheap pictures look expensive; given bigger budgets, they made expensive pictures look cheap. Here that cheapness shows most in some video-generated shots that recall the bad old days of edge enhancement. But who has time to study such problems when you’re smacked by a fusillade of 3000-plus shots in 105 minutes? Resistance is futile, and the pace doesn’t relent. When the fights and pursuits pause, the dialogue scenes flash by in a flurry of cuts and unfortunate lapses into English. (Much of the soundtrack recalls the eerily dubbed voices on US videos of The Killer.)

You’ve got no time to worry much about all this after an opening that drops us straight into an ambush. Ultra-cool Du Qiu drifts into a bar and quotes yakuza movies before leaving the hostesses to slaughter the gangsters dining there. It does get your attention, and it encourages you to sit through the exposition showing Du as the trusted lawyer for a corrupt pharmaceutical company. He proceeds to be framed for murder and goes on the run. Meanwhile stalwart detective Yamura, charged with bringing Du in, begins to suspect that there’s a bigger scheme afoot. Of course he is right.

This is all completely preposterous and continually enjoyable, with constantly startling action choreography and an overheated soundtrack that at one point breaks into Turandot. Here those damn pigeons don’t just soar into the sky; thanks to CGI, they flap annoyingly into the middle of fight scenes, spoiling a punch or a gunman’s aim. We have, besides our twinned heroes, one corrupt cop, one psychopathic son, one fairly mad scientist, two expert hitwomen (one played by Woo’s daughter), a fleet of black-suited motorcycle assassins, and two docile women who acquire some non-negligible lethality. In the press conference, Woo emphasized his eagerness to create women warriors, and he hasn’t stinted. There are hallucinatory images of a bloody wedding dress to enhance the feminine mystique.

Manhunt is a kind of palimpsest of Asian action movies. It’s a remake of a 1978 Takakura Ken movie released to great popularity in China during the 1980s. Woo, in Hong Kong, had already succumbed to that actor’s spell. What Alain Delon was to The Killer, Takakura is to this, and the steelly self-possession of Zhang Hanyu gives the film a solemnity amid all the flamboyance.

Woo has turned the Japanese original into a real Hong Kong movie, vintage 1992. It lacks the mournful homoeroticism of his prime-period work; these two men don’t gaze moistly at each other, but fire quips and complaints in the Lethal Weapon manner. (The bonding is strongest between the duo of female killers.) Still, it’s very welcome, with its proudly retro air and fanboy in-jokes. It earns the right to begin with a reference to a Japanese classic and conclude with a wink to A Better Tomorrow, as if that movie were the next link in a grand tradition. “Old movies always end this way,” says one of the survivors of the carnage. I wish more new movies did the same.

Hitmen in cars getting shot

Outrage Coda (2017).

Compared to Woo, Kitano is brutally laconic. In Outrage Coda, except for one Wooish slow-mo massacre, violence is brusque, shocking, and over fast. In a film full of bland pans following yakuza cars here and there, the end of one panning movement bursts into shooting before you realize it’s happening, and it ends just as suddenly. Kitano likes his confrontations, for sure, and sometimes there’s a buildup, but mostly the blood just erupts, punctuating long scenes of gangster intrigue.

Here that intrigue involves three rival gangs, each with bosses capable of remarkable lip contortions: the Hanabishi yakuza family, its once-powerful subsidiary the Sanno group, and a gang of fixers operating in Japan and Korea under the auspices of boss Chang. Add in two cops, one ready to knuckle to corrupt superiors, the other raging against them, and you have the world through which Otomo (Kitano) and his sidekick Ichikawa move. Normal life, as it’s commonly known, has no place here.

The action bristles with schemes, shifting alliances, double-crosses, faked deaths, and power grabs.”Your methods,” remarks one boss to a co-conspirator, “are increasingly more intricate.” Remarkably, after an introduction humiliating the not-so-bright Hanaba during a sexcapade, Otomo isn’t seen that much. Two-thirds of the running time are devoted to the machinations of the gangs and the cops. Otomo and Ichikawa swing into action rather late, their task being to chop through the knots of plot and counterplot.

The opening few minutes spread out the key motifs. A fishing scene displaying Kitano’s characteristic love for boyish pastimes is interrupted by the discovery of a pistol. The credits sequence announces the importance of cars with gorgeous shots of Otomo being driven through neon-lit streets, his ride seen from straight down as lights play over it. Throughout, deals are struck or broken in cars, and one memorable execution makes creative use of a Toyota. Even that banal filler, shots of cars pulling up and disgorging their riders, gets played for variations: distant thunder when bosses arrive for a conference, abstract configurations when rival forces meet on a rooftop.

During the 1990s Kitano was one of those directors working with what I’ve called planimetric staging and compass-point editing. (Wes Anderson, Terence Davies, and others worked the same territory.) Characters face the camera in medium shot, and shots change along the lens axis or at 90 degrees to it. It’s as if we were in between the characters. When I asked Kitano about the technique back then, he claimed that it was his effort at realism, capturing how people faced one another in conversation. He added that he didn’t know how to direct a scene, and this was the easiest way.

I thought that his images’ paper-doll simplicity suggested a naivete suited to Kitano’s childish hitmen. Moreover, this rigorous, geometrical technique takes on special impact when presenting mobster shootouts. Instead of ducking for cover as Woo’s heroes do, Kitano’s stand up and keep blasting, firing straight out at the viewer in tit-for-tate exchanges. His unflinching framing, refusing Woo’s camera arabesques, gives these encounters a ceremonial gravity, turning them into rituals of professional righteousness. Last man standing, indeed.

The face-to-face shootouts in Outrage Coda adhere to this style, and early in the film so do the conversations. Here is Otomo discovering Hanada in his masochistic rig.

But for many dialogue scenes Kitano has gone with more orthodox staging and shooting. We get over-the-shoulder shots for conversation, tight close-ups to emphasize character reactions, and even that commonplace of modern cinematography, the arcing movement around a speaker to pick up a listener in the background. These choices allow Kitano to expose the ripe performances of the two conspiratorial dons Nishino (Nishida Toshiyuki) and Nakata (Shiomi Sansei); their leathery skin, slip-sliding jaws, and shouted outbursts gain a lot from this treatment. Not that I’m really complaining. In a slightly longer film than Manhunt, Kitano gives us around 700 shots, less than a quarter of Woo’s outlay. Each image carries a lot of weight.

Outrage Coda concludes a trilogy, and at the press conference Kitano said that he conceived this and Outrage Beyond (2012) as one continuous phase of the story. He wanted the series to finish. The ending of this installment will fuel much speculation about his next move, and he hinted that he might adapt a forthcoming novel, one that’s a love story. He’s done one before in A Scene at the Sea, and arguably in Kikujiro (1999). His fans, who mobbed him at the panel, are certainly ready for whatever he comes up with.

Thanks as ever to all those at the Venice Film Festival who made our stay so enjoyable. Special thanks to Peter Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michela Nazzarin, Jasna Zoranovich, and our colleagues at the Biennale College Cinema endeavor.

For more on John Woo’s style of action cinema, see my book Planet Hong Kong. I discuss planimetric staging and compass-point editing in On the History of Film Style and several blog entries, notably the persistently popular Shot-consciousness (which has side notes on Kitano) as well as entries on Wes Anderson.

John Woo and Kitano Takeshi satisfy their fans.

Venice 2017: Martel’s drama of expectations

Kristin here:

Lucrecia Martel’s Zama (pronounced “sama”) happened to be only the third film we saw at the Venice International Film Festival, on the evening of its first day. As the credits faded, David asked, “Have we just seen a masterpiece?” Neither of us doubted that we had, and we suspected that we had also watched the best film we would see during the entire festival. Of course, we haven’t seen every title on offer here, but having just come back from my twenty-fourth and final film, I don’t doubt that it is.

It is also a challenging film, which we watched a second time to try and grasp the basics of what plot there is. Those of us who admired Martel’s earlier work, particularly The Headless Woman (which we also felt compelled to watch twice, this time at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2009 and wrote about here), had looked forward to her follow-up film. It was eight years in coming, and it is quite different from her earlier films in several ways.

First, while the three earlier features are set set in modern middle-class milieus, Zama is a period piece. The others had original screenplays, written or co-written by Martel, but Zama is based on a 1956 novel by Antonio Di Benedetto (translated into English in 2016). Martel was also working with a higher budget here, one which required patching together many sources of financing. The result is a co-production involving, Argentina, Spain, France, the Netherlands, the USA, Brazil, Mexico, Portugal, Lebanon, and Switzerland and a patchwork of sixteen companies. At the press conference (below) Martel said that the long gap between films was not occupied with making all these arrangements and with shooting the film, which was actually a reasonably short process. She did make a few short films during this time and was ill enough to cease working for a while.

The result of the film’s elaborate production situation is not a typical historical epic. There are impressive landscape shots in some scenes, but no uniformed crowds and grand buildings. No vast battles take place; instead there are a few small skirmishes. The bulk of the action takes place in a ramshackle group of buildings thrown up to house the Spanish colonial government of the provincial town of Asunción, already in decline by the 1790s. The money clearly was spent on creating authentic costumes and furnishings, as well as transporting the cast and crew to locations in Paraguay.

Frustrations of a colonial bureaucrat

Lola Dueñas (Luciana), Lucretia Martel, and Daniel Giménez Cacho (Zama).

We quickly learn the story’s basic premise, that Don Diego de Zama is an official stationed in this backwater town and that he fervently longs to be transferred to a more important city–ideally where his wife and children live. He is not in charge of this outpost but serves under a governor whose request to the Spanish crown is necessary for such a transfer.

We are certainly not invited to like Zama when we first meet him. The first shot shows him standing and looking down the river (see top). We later learn that he was probably watching for the boat carrying mail, which he hopes will include a letter from his wife or some official news concerning his situation. He spies on some naked indigenous women smearing themselves with mud, and when they taunt and chase him, he turns on one and slaps her viciously. In the second scene he presides over the torture of a young man who refuses to divulge some unspecified information the governor needs.

As the action proceeds, however, we witness the countless little frustrations, embarrassments, bafflements, slights, and misfortunes that Zama seems to experience constantly. A brandy merchant who arrives with his wares, seemingly one of Zama’s few friends (below), dies suddenly of the plague. Luciana, a wealthy local beauty, teases him with suggestive conversation but ultimately takes a younger man as a lover. A new governor’s arrival hints that Zama is back to square one as far as his hopes for a transfer are concerned. The man takes over Zama’s modest home and office, leaving him to haul his sparse furnishings to a barely habitable inn. When no letter from his wife arrives, Zama imagines a conversation with her in which they lament the long delay in their reunion, though we must suspect that her failure to correspond means that she has given up on him. Through all this we come to sympathize with him. We never learn how long he has been in this posting, but when someone asks he replies glumly, “a long time,” and we believe him.

Zama might seem at first to be the epitome of a goal-oriented protagonist, but he is hardly the striving, active Hollywood-style hero. There is nothing he can do to better his current situation or to further his desire for escape. Instead, the action consists of one new, often bizarre challenge after another, creating situations that simply play out, usually to no conclusion. None of these situations furthers Zama’s cause. Gradually we become aware that he is actually losing ground, as when the new governor reveals that he must write not one but two letters to the king, a process that could take a year or two. The final portion of the film takes him in a radically new direction as he tries one desperate bid to gain stature and perhaps his long-delayed transfer, a bid that only leads to worse troubles for him.

There is little sense of how much times passes in the course of this accretion of frustrating incidents. During the press conference (above), the cinematographer Rui Poças and Martel said that they sought a visual way to convey a sense of Zama’s agonizing wait, a way to give “the sensation of time that has stopped,” as Martel put it. They deliberately avoided some of the conventions of historical films. One of these was to eliminate fires and candles. Martel added, “In order to be able to think, you must be deprived of things.” This rule was strictly obeyed, with one shot that turned out to contain a candle flame in the background being eliminated. When one thinks about it, lamps, candles, and fireplaces tend to figure quite prominently in suggesting the past in films, which became particularly evident, for example, when a great deal of fuss was made about the new ability to shoot dark scenes only by candlelight in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975).

Thinking, being deprived of things

As Martel also pointed out, the original novel was told in the first person by Zama, with few descriptions of locales or nature. The film opens the tale out with the occasional landscape views in the early portions and a move into a savanna setting for its last stretch of action (see bottom). For much of the film, however, Martel uses the style I described in The Headless Woman, ” shooting largely in tight shots filmed with highly selective focus.” We stay almost exclusively with Diego, scanning his face for his reactions, so that the film becomes a psychological study, though the title character is a man who manages to carry on by keeping his thoughts and emotions well hidden.

Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho gives a remarkable performance as Zama. We soon realize that the character has very little understanding of the bizarre things that happen around him and of the attitudes that other people have toward him. At times he adopts the faintest of smiles, ready in case what is being said to him is supposed to be amusing. More often he looks mildly worried, as if expecting another mocking remark or revelation of some new indignity to be offered. In his court his face could be taken to convey an appropriate dignity and wisdom (below), but it might just as well be puzzlement over the case before him. With Luciana he seems passive, but his face conveys hints of lust, hope, and an anticipation of ultimate rejection. In a meeting with a superior official, he struggles to ignore the ludicrous presence of a llama (which we had seen outside when he arrived) wandering around the office behind him as he pleads his case.

All in all, despite the fact that Cacho’s craggy, earnest face seems to suggest competence, we emerge from the film with no real sense of whether Zama is in fact competent and unfairly treated or simply a man out of his depth who deservedly remains stuck where he is.

One extraordinary moment which I cannot resist mentioning comes late in the film when a horse in the foreground of a scene turns and looks directly into the lens (top of this section). Its stare is even more enigmatic than Zama’s face, just another little mystery that Martel provides.

It is not surprising that Zama was the first in a series of three novels that have come to be called Di Benedetto’s “Trilogy of Expectations.” The second, El silenciero (1964), and third, Los suidicas (1969), share no plot elements with Zama but are thematically linked to it. It is also not surprising to learn that the novelist first read Kafka in 1954, just before writing Zama.

Guy Lodge, in his enthusiastic review for Variety, refers to Zama‘s “unjust placement in a non-competition slot at Venice.” It has garnered quite a few reviews as laudatory as Lodge’s, as well as a few which dismissed it as cryptic and not engaging. A good summary of the coverage, regularly updated, is provided by David Hudson. The film deserves to gain a higher profile in its upcoming screenings at the Toronto and New York festivals. Perhaps it will also pick up a North American distributor. Somehow it should be made available on home video (Criterion, perhaps?), since this is going to be considered a classic.

The most detailed account of Di Benedetto’s life and work available online is an essay by the translator of the English-language version, Esther Allen.

Again, we are grateful to the Mostra and those who serve it, particularly Alberto Barbera and Michela Nazzarin. Thanks as well to Peter Cowie and David’s colleagues on the Biennale College Cinema panel, who have all been good company.

[October 1, 2017: Argentina has chosen Zama as its nomination for best-foreign-language Oscar. I doubt it will make it into the final five, given how challenging it is. Still, maybe it will, and in any case, it’s good to see Martel getting respect in her home country.]

[October 16, 2017: Strand Releasing picked up the North American distribution rights for Zama last month, shortly before its American premiere at the New York Film Festival. It plans a theatrical release in early 2018.]