Archive for the 'Festivals: Wisconsin' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival 2022: A return to the theaters

Hit the Road (2021).

KT here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival ended last week. This was the first in-person festival after one cancelled (2020) and one presented through streaming (2021). Given David’s health situation, I was not able to attend many films, but here are some of the highlights that I caught.

Wisconsinite David Koepp visited the festival, bringing two films he scripted, Kimi (Steven Soderbergh, 2022) and Death Becomes Her (Robert Zemeckis, 1992), as well as one that inspired the former, Sorry, Wrong Number (Anatole Litvak, 1948). David and I had already seen Kimi on streaming, but I jumped at the chance to see it on the big screen. The sell-out crowd was utterly enthralled throughout, and David K. charmed them during an all-too-short Q&A session. I won’t say anything more about it, since David B. has blogged about it. I did enjoy two Middle Eastern films and the new Claire Denis. (Not the one about to be in competition at Cannes. The woman is certainly cranking them out.

Amira (2021)

In 2017, the Wisconsin Film Festival showed Mohamed Diab’s extraordinary Clash (2016), an epic restaging of the 2013 riots that brought down the Muslim Brotherhood government, all observed by a group of prisoners in a police paddy-wagon. I was excited to see that this year’s festival included Diab’s next film, Amira.

The new film is quite different from Clash. While that showed a cross-section of Cairo participants in the riots or simply bystanders swept up by the police, Amira centers on a personal drama of an extended family living in an unidentified occupied Palestinian area of Israel. (The film was shot in Jordan, so local landmarks would be no help in figuring out exactly where the family lives.) Amira’s parents have never consummated their marriage, since the husband, Nawar, is imprisoned for life, and his wife Warda became pregnant through semen smuggled out of the prison. Amira is officially the daughter of Nawar’s brother, but she is fiercely devoted to Nawar, going through elaborate security procedures to visit him in prison.

The plot gets going when it is revealed that Nawar has a genetic abnormality that rendered him sterile from birth. The close-knit family descends into vicious arguments and accusations, with Warda being suspected of infidelity, the men on both sides of the family indignantly refusing to take DNA tests, and Amira concocting wild schemes to protect both her parents and ultimately take revenge on the person deemed guilty of bringing disgrace on the family.

Despite the impressive shot of Amira and her boyfriend against the city (above, a cropped image from the widescreen film), the film opts for crowded interiors most of the time–though not as limited as the paddy-wagon of Clash. Small apartments, narrow alleyways, and above all the visits to the prison create a claustrophobic atmosphere where nature and the bustle of society in the city are largely eliminated.

The prison scenes involve extended shot/reverse-shot conversations between Nawar and his family members through a glass barrier.

Shot with telephoto lenses, the scenes use shallow focus to concentrate our attention on the central characters. At the same time, though, reflections and planes of action out of focus create a sense of cramped space and similar conversations going on in a cramped room. Here Nawar suggests that he and Warda have a second child, since an opportunity to smuggle out some of his semen again. Amira’s delight at the idea and Warda’s doubtful expression set up the disastrous revelation to come: that Nawar cannot in fact be Amira’s father.

Checking Diab’s filmography on IMDb, I was surprised to learn that he is the main director on the current Marvel streaming series, Moon Knight. I had been completely ignoring this show, since I have little to no interest in the MCU. I did notice some comments by Egyptological friends on Facebook that the hieroglyphic texts were authentic (an important chapter from the so-called Book of the Dead), as attested by actual Egyptologists. One reviewer commented, “Hollywood has had a problem with how Egypt is represented in both film and TV. ‘Moon Knight’ has done a superb job with episode three, showing Egypt as an actual modern civilization as opposed to a barren wasteland of only sand with a yellow tinted filter over it.” He does not seem to have noticed that this might be due to the fact that an actual Egyptian director was chosen.

I suppose this is not terribly surprising, since for years there has been a trend toward Hollywood producers suddenly elevating talented foreign and indie directors into the ranks of makers of big franchise films. Taika Waititi went from What We Do in the Shadows and Boy to Thor: Ragnarok and Chloe Zhao from Nomadland to Eternals. (I list a considerable number of similar leaps from the festival scene to the world of blockbusters in my entry on Waititi’s rise to international fame.) Still, Diab seems a strange choice. Maybe Clash was sufficient demonstration that he could do epic scenes of violence. I suppose I shall have to give Moon Knight a look.

Hit the Road (2021)

For years now we’ve been blogging about Panahi films (click on Directors: Panahi in the Categories at the right). Now we have another, but it’s not by Jafar. Panah Panahi is his son, and this is his feature debut. Panah began by making shorts, worked as a set photographer, and later as an editor, most notably on his father’s latest feature, Three Faces.

Hit the Road (the Farsi title is more literally translated as “Dirt Road”) reminded me more of the films of Abbas Kiarostami than of the elder Panahi. Jafar worked as an assistant director on Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees (1994). Panah was only ten years old at that point, having been born in 1984, the year of Kiarostami’s early feature documentary, First Graders. The New Iranian Cinema came to world prominence later in the 1980s and into the 1990s. Jafar moved into directing features in 1995 with The White Balloon.

Growing up, Panah must have become familiar with the now-classic films of Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, as well as those of his father in the years before the latter’s arrest in 2010.

Hit the Road is reminiscent of the “child quest” films of the early years of the movement. In this case, though, the child in question is not the center of the plot, even though the rambunctious kid steals every scene he’s in. He’s accompanying his parents and older son on a road trip that occupies the entire length of the film. The older son is as quiet as his brother is noisy, but it gradually comes out that he is heading for a spot where he will join others being smuggled out of the country in search of better lives. The parents keep this a secret from the little boy, fearing that he will blurt out something that will draw attention to their goal.

The film is a skillful blend of suspense on that account, of a poignant if quarrelsome love among the family, and a good deal of comedy supplied by the little boy. Amid all the raucous exchanges there are quiet moments, as when during a rest stop the unnamed mother nags her older son about smoking too much while sharing a cigarette with him and asking what his favorite movie is. By this point we suspect that she fears that she will never see him again once they reach the border. (Richard Brody’s insightful review captures this mixture of tones.)

Unlike Amira, Hit the Road is shot entirely out of doors, and often in beautiful, bleak Iranian landscapes (top of entry and below).

At times the family’s SUV climbs hills in shots that recall those of Kiarostami’s films,especially And Life Goes On and The Taste of Cherries, as in the frame at the top of this section. (The literal translation of the Farsi title, Jaddah Khaki, is “Dirt Road.”)

The film has been critically acclaimed and successful on the festival circuit, winner Best Film at the London and Mar del Plata festivals. It seems likely that we will now have two Panahis to report on from future festivals.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire, 2022)

I found Denis’s latest a frustrating and puzzling film for almost its entire length. It reminded me of a similar experience I had with Pablo Larraín’s Ema at the 2019 Venice International Film Festival. I described my initial reaction to that film at the time: “While watching it, I could not discern much of a plot or even a coherent character study.”

Denis’s film, shown outside France under the rather baffling title Fire, starts out innocently enough with a scene of lovers, played by Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon, enjoying a blissful, solitary, wordless swim in the ocean. This sets up the “amour” part of the original title. Surprisingly enough, this idyllic sequence, the most visually attractive of the film (above and at the bottom of the entry) was shot during the pandemic on a phone with just the two actors, the director, and the cinematographer present.

Sara and Jean are long-time lovers, and their happiness together continues as they return to their Parisian flat. Soon, however, Sara’s previous lover, François, re-enters their life. He has asked Jean, who has in the past been in prison for some unspecified crime, probably financial, to join him in a athletic scouting agency. Coincidentally, Sara has spotted François in the street, an encounter that seemingly stirs up her old passion for him. She mentions the encounter to Jean, but treats it as a minor thing, expressing pleasure that Jean has been given an opportunity to go into business with his old friend.

From that point the film becomes largely a series of increasingly fraught arguments, as Sara seems to pledge her devotion to both men while resenting the jealousy that they both increasingly feel. All three are revealed to be unpleasant characters acting unwisely, and I, at least, wondered what the point of it all was. The plot seemed to be the classic love triangle, with the question being which man Sara should end up with and whether she will make the right decision–and the issue seeming not to make a great deal of difference for the viewer.

I don’t want to say any more about the plot, since the point of it is to figure out at the very end what Denis had been up to all along. I realized that she was undercutting our expecations about the very clichés that she had presented to us. Apparently I was right. In an interview with Denis, Joseph Cronk mentions that “In an interview in the press notes for the film, you mentioned that the film’s simplicity was ‘a way of foiling clichés.'” Indeed. I’m not sure that many people in the audience with whom I saw the film got the point. I heard some grumbling among the spectators as we left the theater.

It is rather odd to make a film where the audience can “enjoy” it only in retrospect.

I should add that the title Fire does not help a bit.I don’t know who came up with it, but it’s misleading. As Denis has pointed out in interviews, there is no equivalent word to acharnement in English. In the interview mentioned above, Cronk suggests that “With Love and Fury” might be a better title. Denis responds:

No, archarnement doesn’t mean fury. There’s no direct translation, but it means something–from our body, something from your flesh. A sort of tension in the flesh. Fury is something different than acharnement. When I tried translating Avec amour et acharnement, I found no English word I liked that could convey what acharnement means. But Stuart [Staples, the composer] had written the song “Both Sides of the Blade,” and I thought this would be the perfect English title.”

Actually I don’t think “Both Sides of the Blade” would give the spectator much of a clue as to what’s going on in the film. Keeping in mind Denis’s explanation of the French title, however, would.

The quotations from Joseph Cronk’s interview appear in the latest issue of cinema scope, #90 (July 31, 2022), “Not on the Lips: Claire Denis on Avec amour et acharnement.”

Thanks as always to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and all the staff and volunteers of the Wisconsin Film Festival.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire).

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Here and there

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020).

Kristin here:

Last time I wrote about three Middle Eastern films. Now I’m writing about three films that are all over the map and presented in no particular order. Such are the pleasures of film festivals, including the Wisconsin Film Festival, which wraps up Thursday, May 20. At 11:59 pm, all the films will be taken offline and we can all look forward to next year’s festival–with luck, back on the big screens of Madison.

The Village House (2019, India)

Achal Mishra’s first feature is a slow, entrancing, nostalgic love letter to his parents’ sprawling villa. The film is broken into three parts, set in 1998, 2010, and 2019. There is no real storyline, apart from the inevitable dissolution of the large extended family that inhabits the house in the first part. There is little dramatic conflict, either. Instead Mishra films everyday activities: men playing card games and teasing each other, women perpetually cooking or caring for a new baby, boys lured away from a game of hide-and-seek to go pick mangoes. It’s the sort of ideal of capturing the quiet poetry of life that the Neorealists never quite achieved.

Mishra admits to being strongly influenced by Ozu and Hou Hsiao-hsien (in his podcast discussion with programmer Jim Healy), and it shows, though there is never overt imitation. The camera never moves, and there are nearly as many shots of empty locales as those with people present. Idle conversations are lingered over in long takes.

Mishra also mentions Wes Anderson, and there certainly are quite a few planimetric shots in the film (above). The three time periods are also set off from each other by different aspect ratios: nearly square for 1998 (also above), widescreen for 2010 (second frame below), and full anamorphic widescreen for 2019. The purpose of these contrasting framings are quite different from Anderson’s in The Grand Budapest Hotel, where the the shots imitate the film ratios of the historic periods that the story moves among.

The narrow rectangle of the 1998 scenes suggests the crowded bustle of the house. From side to side it’s full of food (yet again above) and people in many shots.

We don’t get much of a sense of the geography of the house, just that it’s full of rooms where ordinary things are going on. We also probably have some trouble figuring out who all the characters are (especially since the jumps forward in time have different people playing them). Still, there’s always something to look at and listen to.

By 2010, the house is aging and the village offers fewer opportunities. One of the sons can’t find a job and wants to sell a plot of land to get money to start a pharmacy. Perhaps the biggest drama in the film comes when an older man tries to talk him out of it. The mundane is still present, though, as one brief scene consists of one character telling another, “The toilet door needs repair, and the kitchen door is jammed.” This casual-sounded remark turns out to be a hint of things to come.

The village still offers traditional festivals, but the sense of community has become less idyllic.

Slowly, however, the family members leave, culminating in the wordless departure of the old grandmother at the end of the 2010 scene.

The final third opens into full widescreen, with more extensive views of the house, empty or nearly so. These don’t give us a much better sense of its geography, but definitely a sense of its desertion by all by an elderly caretaker and some intrusive goats.

The renovation of the house starts at this point, though we are not shown what it eventually came to look like.

The Village House is available to stream anywhere in the USA until the end of the festival.

Calamity: A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary (2020, France)

Rémi Chayé’s film won the Cristal for a Feature Film (top feature) at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival for 2020, and it’s easy to see why. Done with hand-drawn images, it has a look all its own. The unblended areas of color create a simple but beautiful set of images (top and above).

The story is aimed primarily at children. It tells an imagined tale of the childhood of Calamity Jane (about which very little biographical information survives), who gains skills and self-confidence when her widowed father is injured during a wagon-train journey west. It’s a woke story for the modern age, as young Marsha endures bullying from the guide’s son and ridicule over her tomboyish clothes and behavior.

Some of her achievements are bit over-the-top, but there’s a tall-tale aspect to the narrative–as is emphasized by scenes in which characters boast of their own acts of bravery around the campfire. It’s entertaining enough, but adults will probably be more impressed by the visuals.

The film is in French with subtitles. I would say that any child not old enough to read subtitles would probably be scared by some of the bullying, violence, and near disasters that occur, though older kids could probably handle them pretty well, given that all ends happily.

Calamity is also available nationwide for the duration of the festival.

Fear (2020, Bulgaria)

I went into Ivaylo Hristov’s Fear knowing little about it except that it deals with a middle-aged Bulgarian widow who captures a lone African refugee. At first she is afraid and suspicious of him but gradually, of course, comes to feel sympathy and even friendship for him. Something of a cliché in this day and age, I thought.

It turned out to be far more complex than a warmhearted tale of a bigot changing her ways. For a start, it’s a throwback to the more cynical of the black comedies of the Czech New Wave, with a similar kind of humor directed against the local authorities, primarily the border patrol and the mayor. They are required by law to feed and house refugees coming across the border before sending them onto the next facility. Most people crossing the Bulgarian border are on their way to Germany. Bamba, whose family have been killed in an unnamed African country, is going there, as are a small, hapless group of Afghans rounded up by the border patrol.

That patrol is mocked, as in the absurd line-up by height in the image at the bottom. They are completely unprepared to accommodate the Afghans, herding them first into the closed local school and later into the open-sided apartments in an abandoned construction site. These are not, however, the bumbling but largely harmless officers of The Firemen’s Ball. Underneath the gags, they are racist, ignorant bullies, roughing up the completely passive Afghans during the round-up. A chillingly funny interview of the officer in charge by a local TV reporter goes on in the foreground, with her repeatedly asking if the Afghans are armed and violent. When he replies that he’s never caught one with weapons or met any resistance, she begs for an anecdote of a time when the patrol was threatened. Again he says there wasn’t one, and she turns to the camera, triumphantly announcing that her audience has witnessed the dangers of letting refugees across the border.

The main story starts quietly by characterizing our heroine, Svetlana, as fearful. She has just lost her teaching job, and we learn that she goes regularly to the cemetery to talk with her dead husband. She lives alone in the country and sleeps with a hunting knife under her pillow. Jobless and not having received her last pay, she goes hunting and runs across Bamba on a forest path. Terrified, she marches him at gunpoint to the border-patrol office, which is deserted because of the mission to capture the Afghans. She tries the Mayor (above), but is told to deal with him herself.

On the first night she ties him up in the yard but eventually allows him to sleep in a locked room on an air mattress. Gradually she becomes more hospitable, to the point where the villagers begin to gossip about her, doing the things that people shocked by interracial couples do–killing Svetlana’s dog and tossing rocks through the window.

In between such episodes Svetlana and Bamba talk to each other, he in perfect British-accented English and she in Bulgarian. We learn a lot about both, but they learn little about each other and can only convey ideas like “I want to wash your clothes” with hand gestures. Nevertheless gradually trust and even warmth are established.

One could argue that Bamba is a bit too close to being a Magic Negro. Not only does he speak perfect English, but he’s a medical doctor. He’s patient and polite and does his share of the chores around the house once Svetlana lets him in. Still, it’s hard to imagine a plausible plot in which a less respectable-looking, working-class black man could win her over in the same way. Plus he is an engaging character, and he makes the dour Svetlana turn into one, so we are unlikely to complain.

The film is shot in impressive black-and-white anamorphic widescreen. There is one spectacular shot that’s quite breathtaking. It’s a drone image, starting on a simple sea view, moving backward through an open-sided room in the building under construction, and continuing on and on to reveal an immense, rambling, unfinished complex.

Did some entrepreneur envision turning the town into a seaside resort and lose funding partway through? We never know, but it provides an odd contrast with the poverty of many of the residents of a seemingly failing town. The only connection to the plot is that the Afghans spend a miserable time trying to live there until the border patrol gives up and trucks them further into the country in search of a place that can deal with them.

Fear turned out to be one of my favorite films of the festival, alongside Sun Children. It’s available for streaming only in Wisconsin through tomorrow.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q&A sessions for many of the films.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Fear (2020)

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021 visits the Middle East

Sun Children (2020)

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival, online this year, continues through this coming Thursday. Films for which audience members buy tickets are all available to watch until 11:59 that night. So far our experiences have been that the streaming system works quite smoothly, with easy access to your chosen titles. Despite geo-blocking (dictated by distributors) in some cases, many films can be watched from outside Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Now, let’s visit the Middle East.

Iran: Sun Children and There Is No Evil

Despite the tragic death of Abbas Kiarostami and the exile into relative obscurity of the Makhmalbaf family, the Iranian cinema continues to produce important films by a small number of auteurs, most prominently Oscar-winner Asghar Farhadi (whose A Hero was recently acquired by Amazon for release later this year), Majid Majidi, the irrepressible Jafar Panahi, and his equally irrepressible colleague Mohammad Rasoulof.

The latter’s There Is No Evil (2020), which won last year’s Golden Bear as best film at the Berlin Film Festival, is on the current WFF program. I wrote about it last year from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Also on the program is Majidi’s latest, Sun Children, which we saw for the first time. Those who think of Iranian festival-oriented films as developing slowly and subtly will be surprised by this one. It is jam-packed with a multi-strand dramatic plot, suspense, fast cutting, and many characters, all handled very skillfully by Majidi.

The film begins with a dedication to the “the 152 million children forced into child labor and those who fight for their rights.” That child labor, as the exciting opening scene emphasizes, often involves small crimes. Four boys set out to steal a tire from a car in the parking garage of a luxurious, multi-storied shopping mall. The suspense begins right away as a guard confronts them. Two of them flee in a classic chase scene, going up through the levels of the mall, past high-end shops that they could never dream of entering. They escape, and it is revealed that the four friends work at a large repair shop, full of stacks of tires, presumably acquired in the same fashion.

Soon Ali emerges as our point-of-view character, desperate to rescue his mother from a mental-health facility. There she lies strapped to a bed after a presumed suicide attempt. Eventually it emerges that the family home recently burned, killing Ali’s sister, whose death drove his mother mad. His father is an addict, and Ali has become the breadwinner. A small-time crime boss sets him a task: enroll in a local school and explore the basement and tunnels under it (above), where a treasure is hidden.

Much of the rest of the film generates more suspense, as Ali diligently makes his way around various obstacles and crawls through branching tunnels day after day, always risking expulsion from the school if he is discovered. His three friends help him at first, but eventually he is left to traverse the seemingly endless tunnels (which are in fact the city’s storm drains).

This part of the film introduces another major plotline, since the school, dependent on private donations, is located in the slums of Tehran. Its aim is to teach young, desperate, potentially criminal boys skills that they can use to get honest jobs. The school is far behind on its rent and in danger of being closed. This adds further suspense as the school officials, particularly a sympathetic vice principal, struggle to find donors. The schools debts lead to one of the film’s big action scenes, as, finding the gates locked one morning, the principal urges the boys to scale the fence. They do this with a determination that reveals their realization that their only hope for a decent life lies in the education they have been receiving.

They eagerly participate in a festival and pageant put on for potential donors (top).

In an interview, Majidi said that the “Sun School” that gives the film its name is based on an actual school in the Tehran slums, the “Sobhe Rooyesh” (“Morning of Growth”). The non-professional child actors, whose performances are all completely natural and affecting, were recruited from the school and surrounding slums. Roolholloh Zammi, who plays Ali, won the Marcello Mastrioanni Award at Venice last year. (I wish we could have been there to see him win!) Only the adults are played by [professional actors.

Israel: Here We Are (2020)

Given the current situation in Israel, it is just as well that Nir Bergman’s gentle psychological study Here We Are (a sadly unmemorable title) has no reference at all to politics, the military, or ethnic tensions. It’s a simple story of a man who has given up his career to care for his severely autistic son and is having difficulties facing the fact that the boy is nearly a man.

The early scenes set up Uri’s disabilities, as well as his obsessions (including pet goldfish–above–and dogs) and phobias (snails). They also establish Aharon’s utter devotion and patience as he cooks yet again Uri’s favorite pasta stars and uses an obviously well-established imitation game to coax his son past imagined snails on a biking route.

The plot action kicks in when Ahron’s estranged wife Tamara shows up, determined to arrange Uri’s transfer to a group home for young people with disabilities. Ahron angrily resists, claiming that Uri is happy at home and that he can care for his son himself.

We seem to be set up to view Ahron as the noble, self-sacrificing father and his wife as the shrewish woman who wants to dictate her son’s life. Eventually, however, Tamara obtains the legal papers requiring Ahron to bring Uri to his new home. Ahron sets out, but along the way he decides to go on the run with Uri, despite having little money.

Along the way there are growing hints that Ahron is stifling both Uri and himself. Twice he simply ignores Uri’s budding sexuality during encounters with young women.

The two seek shelter with an old friend of Ahron’s, Effi, an art teacher who reveals that Ahron had had a prominent and lucrative career as an artist and designer, which he had given up to care for Uri. Her attitude toward Ahron suggests her openness to a romantic relationship with him. Eventually we begin to doubt that he is acting in the best interests of himself and Uri, especially during a scene in which they are forced to dine on ice-cream sandwiches in a bus-station waiting-room.

Here We Are is a film that unfolds gradually and overturns your expectations slowly but thoroughly.

France-Lebanon: Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Chloe Mazlo is a French animator and artist who has previously made shorts (including The Little Stones, which won the 2015 César for Best Animated Short). Inspired by her grandparents’ life in Lebanon (he was Lebanese, she Swedish) during the lengthy civil war, she has made a feature that combines occasional animation with live action.

The film starts out in a stylized, fantastical world that inevitably has led critics to compare Skies of Lebanon to Amélie (2001). Alice, the heroine, is alienated from her parents and her home country, Switzerland, and take a job as a nanny in Beirut. The city as it was in the 1950s is represented by matte shots of actors presumably filmed against a green-screen, with backgrounds filled in by blow-ups of tinted postcards of the period. Such shots have a charming effect.

Alice meets cute with a handsome physicist whose goal is to invent a rocket to put the first Lebanese astronaut into space. Their romance develops in a fantasy landscape of patently artificial rocks and stars (bottom). They settle down together, raise children, and pursue their careers, with Alice becoming a watercolorist.

The fantasy strain in the film is most obvious in the brief animated scenes, as when a split-screen telephone conversation juxtaposes the real Alice with puppets representing her angry parents, who demand that she return home (top of section).

About a third of the way into the film, the tone switches abruptly as the Lebanese civil war breaks out. The animations and postcard background disappear. As characters flee and disappear mysteriously, a shot of a wall with “have you seen” photos pasted up emphasizes the danger that Alice is trying to ignore.

Even during the lengthy wartime portion of the film, there remains a faint underlying humor. Yet the abrupt shift of tone when the war starts is unsettling, given that we had settled down for a whimsical romance and end up with a war story. Presumably the idea is to emphasize how war breaks into the calm of ordinary life and banishes it. Whether audiences will take it that way is another matter. On the whole, however, the film is an imaginative and promising first feature.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

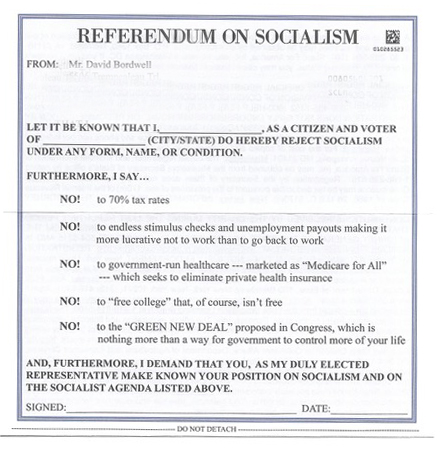

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

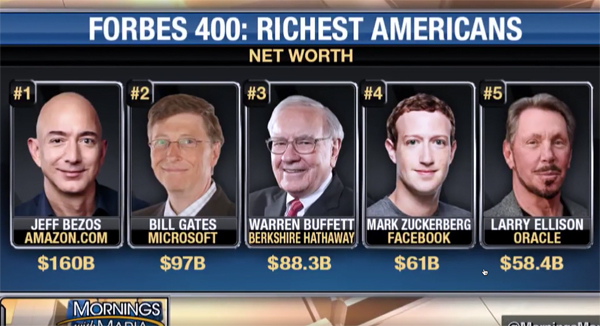

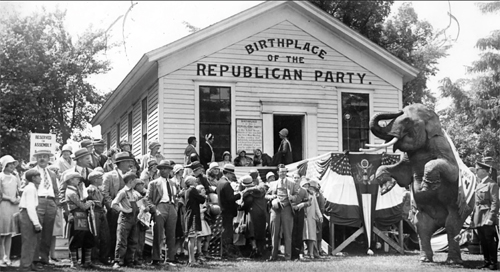

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

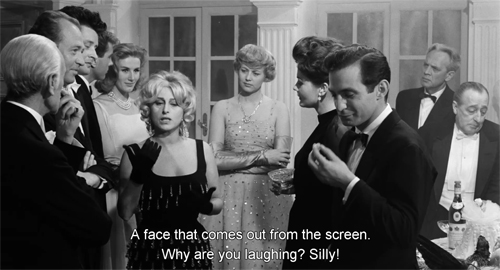

The Passionate Thief (1960).

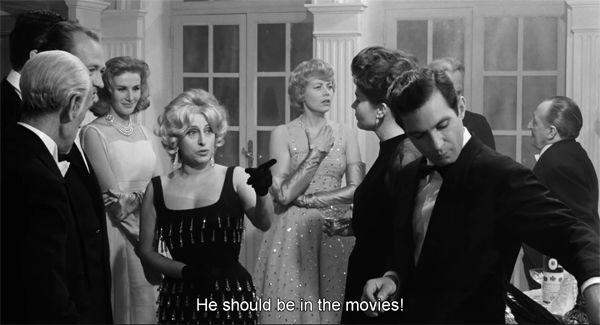

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

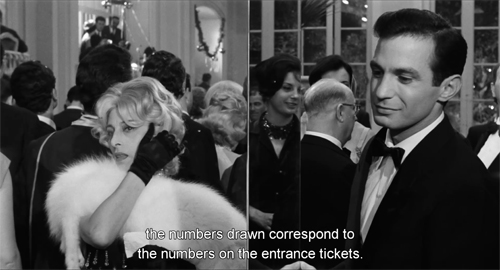

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).