Archive for the 'Festivals: Wisconsin' Category

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

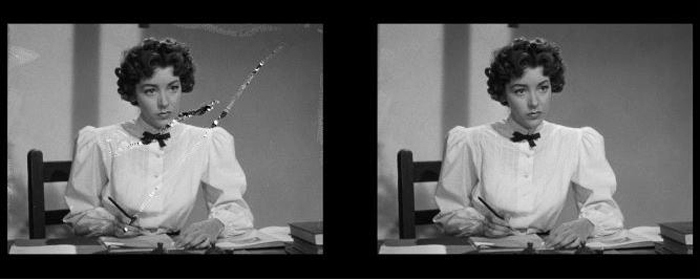

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

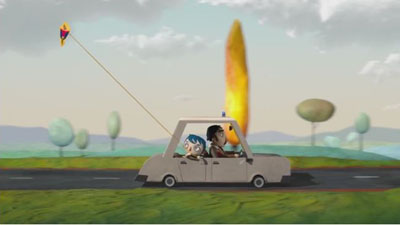

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Confined to quarters

12 Days (2017).

DB here:

I try to watch any film at two levels. First, I want to engage with it, opening myself up to the experience it offers. Second, I try to think about how the film is made, why it’s made this way, and what those practices and principles can teach me about the possibilities of the medium. That second level of response, not easy to sustain in the thick of projection, comes from my research interests, something spelled out as the “poetics of cinema.”

Most critics, particularly those reviewing films on a daily basis, don’t have the time or inclination to reflect on that second level. I’m lucky to have the leisure to mull over what this or that film can suggest about film in general. When a new release points me toward something I think is intriguing, I’ll go back and watch it again. I saw Zama three times last year, and Dunkirk five times. After three viewings and getting the Blu-ray, I think I’m ready to write about Phantom Thread fairly soon.

Several films at the festival set me thinking. Vanishing Point (1971), which I hadn’t seen in a long time, confirmed my idea in Reinventing Hollywood that 1940s narrative strategies resurfaced in the 1970s. (Whew.) We get a crisis structure motivating a flashback, which itself embeds further flashbacks, everything tricked out with plenty of road rage.

Philippe Garrel’s Lover for a Day (L’Amant d’un jour, 2017) reminded me of how important coincidence is in narrative, particularly the accidental discovery of an important item of narrative information. You know, like coming home just as somebody’s about to commit suicide. Or discovering on your way to the WC that your lover’s having sex with someone else. I began to wonder if the episodic nature of art films, which are built more on routines than on sharply articulated goals, gets away with such handy accidents by suggesting that with so many characters drifting around, they’re bound to intersect occasionally. Realism once more becomes an alibi for artifice.

And I was happy to see American Animals (2018), an amateur-heist movie that uses my friend the flashback in a way that cunningly misleads us. I will say no more, except to refer you to other reflections on caper movies, and to express my hope that Ocean’s 8 will offer some fresh twists too.

All of these films employ what we might call omniscient point of view. The film’s narration shifts us among many characters in many places and times. Herewith, though, some thoughts on two films that tie us down.

Elbow room

The Guilty (2018).

One of cinema’s great powers is its ability to shift locales in the blink of an eye. Unlike proscenium theatre, bound to drawing rooms or perspective streets, a film can carry us from place to place instantly. Novels can do this too, of course, and so can certain theatre traditions, such as Shakespeare’s wooden O. But cinematic crosscutting swiftly from one line of action to another and back again is such a powerful tool that many theorists identified it as part of the inherent language of cinema. The medium seemed wired for camera ubiquity.

At certain periods, though, filmmakers kept to single spaces. Early cinema’s one-shot films locked us to a single view, and in the 1910s, long scenes would play out in salons and parlors. Even after the arrival of crosscutting and other editing strategies, some filmmakers embraced the kammerspiel, or “chamber play” aesthetic popularized in Germany. Lupu Pick’s Sylvester (1924), Dreyer’s Master of the House (1925), and other silent films built drama out of micro-actions in tight spaces. Later Hitchcock took this premise to an extreme in Lifeboat (1944), Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954), and to some extent in Dial M for Murder (1954). Rossellini’s Human Voice (1948) is another instance which, like Rope and Dial M, was based on a play.

The confined-space option reemerges every few years. Put aside Warhol’s psychodramas, so well analyzed by J. J. Murphy in his book The Black Hole of the Camera. Most of Tape (2001), Panic Room (2002), Phone Booth (2002), Locke (2013), and Room (2015) follow this formal option. Two striking films from our festival show that this strategy still holds a fascination for directors. They know that spatial concentration can shape the audience’s experience in unique ways.

In The Guilty director Director Gustav Möller ties us to Asger, a Danish policeman assigned to answering calls on an emergency line. A woman caller tells him she’s been kidnapped, and he tries to locate her while also giving her advice on how to protect herself. In the meantime, he summons police units to track the car she’s in and to investigate the household she’s left behind. In the course of this, we come to understand that he’s grappling with his own problems. He’s about to go before a judge for an action he committed on duty, and his partner is going to testify about it. The whole action takes place in more or less real duration, in eighty-some minutes of one night.

The Slender Thread (1965) similarly includes longish stretches confined to a suicide-hotline agency, but it supplies flashbacks that take us into the caller’s past. Here, we stay in place with Asger. By confining us to what he hears, and what little he sees on his GPS screen, the narration obliges us to make inferences that seem reasonable but that turn out to be invalid. I can’t say more without giving away the twists, but it’s worth mentioning how keeping major action offscreen enables the film to summon up the Big Three: curiosity (about the past), suspense (about the future), and surprise (about our mistaken assumptions).

The Guilty is a sturdy thriller, and it certainly works on its own terms. While restricting us to a character, it doesn’t plunge–as many films would have been tempted to do–into his mind, by means of flashbacks or fantasies. These would have “opened out” the film, but lost the laconic objectivity of the action we get.

The film coaxed me to reflect on how the reliance on the conversational situation allowed for a certain looseness at the level of pictorial style. Once we’re tethered to Asger at his workstation, not a lot hangs on choices about camera placement or shot scale. As long as his face, gestures, and body behavior are apparent, niceties of framing count for less. His reaction can be signaled adequately from many angles. He’s so stone-faced that even a 3/4 view from the rear suffices.

In other words, I can’t see that the situation is submitted to a stylistic pattern that would add another dose of rigor to the filmic texture. The style, I think, works to adjust our attention in the moment, in the manner of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” rather than building longer arcs of pictorial interest. While the plot constraints are strict, the visual style seems less so.

What would be a way to make pictorial style more active? Well, the obvious cases are Hitchcock’s long takes in Rope and optical point-of-view in Rear Window. (And, I’d suggest, his use of 3D in Dial M.) Dreyer did something similar in The Master of the House, in which editing patterns activate a range of props and bits of setting. Films like these benefit from including several characters onscreen, providing details of setting and building up spatial “rules” that channel our vision. Or think of Kiarostami’s auto trips (I almost said “car-merspiel”), which limit camera setups pretty stringently. Ditto Panahi’s ways of stretching the notion of “house arrest” in This Is Not a Film (2011), Closed Curtain (2013), and Taxi (2015)–films that tantalize us with the possibility of glimpsing the world outside.

Möller chose, with good reason, to rivet our attention on two basic elements: the calls and Asger’s responses. The cop’s interactions with others in the office are minimal, and there’s almost no play with props or setting, apart from a moment when Asger decisively snaps down the windowblinds. Our attachment breaks off only at the end, at the conventional moment when the protagonist turns from the camera and walks away.

The tight concentration enhances both plot action and character revelation, and we’re obliged to listen more closely than we do in most movies. Along the way, blinks and eye-shifts and finger-tapping become major events. Still, The Guilty reminded me that every choice cuts off others, forces new choices, sets up constraints–and new opportunities. Film art is full of trade-offs.

12 Day wonder

12 Days (2017).

A more “dialectical” approach to confined space is on display in Raymond Depardon’s documentary 12 Days (2017), probably the most emotionally wrenching film I saw at our fest. The situation is a similar to that in his Délits flagrants (1994), which recorded police interrogations of suspects. The official procedure captured here is a hearing, mandated within twelve days of a patient’s being involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. A judge reviews the case to determine whether the patient should be set free.

Sessions with ten patients take us along a spectrum of disturbance, from a woman believing herself persecuted in her office to a man whose inner voices commanded him to stab a stranger. The last petitioner, a woman sufficiently aware of her illness to admit that she can’t care for her baby, makes a lucid case for being allowed to visit the child occasionally.

All these encounters are shot in a simple but strict fashion. In three reverse-shot setups, we see the petitioner, the judge, and a wider view of the petitioner and the lawyer who states the case.

This neutral approach, far less free-ranging and nerve-wracking than the shots in The Guilty, doesn’t try to amp up the suspense with cut-ins or zooms or pans. It throws all the emphasis on the interchange. Call it Premingerian, if you must.

Sandwiched in between these inquiries are shots of the hospital itself. We’re still confined, in that we never leave the grounds, but these let us breathe a little. Sometimes these interludes are simply quiet tracking shots down empty corridors; sometimes we hear wails and cries behind locked doors; sometimes we see the patients in a rest area, smoking or pacing or simply staring.

By respectfully observing the surroundings, Depardon lets us into a bit of the texture of the patients’ lives and makes us understand that this hospital, while apparently not very oppressive, is still far away from freedom.

Confronting 12 Days we on the outside are forced to balance compassion with prudence. Should a calm, polite man who believes he beatified his father by killing him be allowed free access to our world? Most of the patients we see are remanded for further treatment, but one leaves the judge ambivalent, to the point that we aren’t told of the final decision. We’re left to reflect that to become wholly human, we must confront madness in our midst. As the opening quotation from Foucault has it: “The path from man to true man passes through the madman.”

Thanks as usual to our Wisconsin Film Festival programmers: Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Matt St John, and Ella Quainton. Thanks as well to Tim Hunter for giving us access to Vanishing Point. In all, it was a swell event. See you there next year?

12 Days reminded me that one of the less-known examples of early Direct Cinema was Mario Rispoli’s Regard sur la folie (1962), which presents afflicted patients and their caregivers with a surprising lack of sensationalism.

We’ve written a fair amount about site-specific narratives. I discuss the crystallization of the trend in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, and I consider its recent revival in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. On the blog, we’ve discussed Panic Room, Dial M for Murder, The Master of the House, This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, and the Kammerspielfilm. And on coincidence, you can drop by here.

12 Days.

Wisconsin Film Festival: Footage fetishism

The Green Fog (2017).

DB here:

Kristin and I have been unusually busy during this year’s fest, its twentieth, so I got to see only ten of the vast array of offerings. Herewith a first report on what our intrepid team–Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Matt St John, and Ella Quainton–programmed and put before adoring crowds. Today we look at movies about movies.

JLG par Not JLG

The title of Michel Hazanavicius’s Le redoubtable has been Francoanglicized as Godard mon amour, not a bad way of signaling it’s a French movie. (The same tactic turned Nikita into La Femme Nikita.) The title also lets us know it centered on the most important living director. And the possessive pronoun correctly puts us in the place of the heroine, the late Anne Wiazemsky, whose memoir-novel chronicled her few years with Godard. How could the film not take her side? On my limited exposure to the man, “difficult” doesn’t begin to describe his temperament.

The film omits Anne’s role in Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar, which Godard admired extravagantly, and takes us briefly through the shooting of La Chinoise (1967). Soon we’re plunged into ’68 debates about making commercial films, making political films, and “making films politically.” We’re firmly attached to Anne, to the point that Godard’s activities at the Cannes festival are kept obstinately offscreen while we see her sunbathing at a villa. There are unattributed voice-overs from an older male, but mostly we’re in Anne’s consciousness as she struggles to live with the torn, cruel, more or less ridiculous man who brought her into the film industry.

As a satire, the film goes for straightforward targets, such as the moments when people come up to our filmmaker and ask why he doesn’t make movies like Contempt any more. That seems to be Hazanavicius’s question as well. He makes no effort to match his film’s style to Godard’s work in the years when the story takes place. It would have been bold, though probably off-putting, to mimic La Chinoise or Le Gai Savoir (1969), one of his most daring experiments, a sort of Child’s Garden of Semiology. Instead we get snatches of pre-1967 scores, chapter titles, compositions, and iconography, with special emphasis on Une Femme mariée (1964), perhaps a sly reference to Anne’s role.

While pastiching the early work, Hazavanicius softens its edges. One of Godard’s minor innovations, for instance, was inserting a chapter title partway through a new section, rather than planting it at the outset. That not only blurs the boundary between segments and usefully jars the viewer, but it also lets the title give a sharper commentary on the images around it. Tarantino embraced this technique, but Hazanavicius is tidier in his chaptering. Similarly, his shoutouts to planimetric framing don’t really exploit their disruptive possibilities.

His film reminds us that Early Godard has become virtually a period style. Hence, perhaps, Godard’s own flight from it over the last forty years, in the process making films of exceptional beauty and abrasiveness. Still, we tend to forget how unsettling the early films remain. (At the Venice International Film Festival last year, Kristin attended the packed 400-seat screening of the restored Two or Three Things I Know about Her and reported that perhaps a third of the audience had walked out by the end.) Despite all his influence, the original Godard will never become “normalized,” just as Schoenberg will never become elevator music.

Godard mon amour goes down easy and doesn’t, to my way of thinking, have a brain in its pretty head. Godard emerges as a wacky celebrity, politically confused and emotionally bullying. There’s no attempt to show how his personality surfaces in his art, or even why his art is important. Still, Godard mon amour usefully calls attention to a director who, in his 88th year, has another feature coming to Cannes. It’s called Livre de l’image, and it promises to be in five chapters, like the fingers of a hand.

Fog over Frisco

Made on commission from the San Francisco International Film Festival, The Green Fog is a collage exercise in associational mode, with echoes of Craig Baldwin’s work. In their own gonzo filmfreak way, Guy Maddin and Evan and Galen Johnson have created an homage to the city and its ultimate film, Vertigo.

It can please on many levels. First, there’s the spot-the-clip quiz in the manner of Marclay’s The Clock. Some bits I found fairly easy to identify, but others are drawn from obscure movies and TV programs. All showcase San Francisco. Second, there’s the looping and twisting motifs of male-female tension, surveillance (films projected, phone lines tapped), and class identity: we’re forced to notice how tony restaurants set the stage for 80s big-hair melodrama.

Then there’s the pleasure of watching how cutting can suggest expanding narrative trajectories through eyelines. The Green Fog is an extended exercise in the Kuleshov effect. Sometimes the whole process gets embedded: people watch screens showing people watching people. Or they’re watching a scene from another movie: McMillan, without wife, sees a tree that was 68 years old when Jesus was born.

These linkages are accentuated by the habit of omitting lines of dialogue, so that characters seldom speak but, in shots plagued by visual hiccups, emphatically react to one another, sometimes just by smacking their lips or gulping.

Not least, The Green Fog is a free fantasia on incidents and images from Vertigo. Although only one Vertigo shot is shown, the canonical moments are evoked by their mates in films both earlier and later: people scrambling up buildings and plummeting, couples embracing in horse stables, men pulling women out of the bay, and–thanks to the invading green miasma–a woman stepping out of a doorway to confront her lover. Scotty’s vision of Judy’s aura is made into a city-wide contagion of obsessive love.

The film takes our memories of bits of Hitchcock’s film and spirals out from them, creating a hallucinatory whirlpool of variations on clichés. Going beyond Vertigo, the film evokes its own vertigo, a media phantasmagoria. I was reminded of Geoffrey O’Brien’s book The Phantom Empire.

How did you wander into this maze, anyway, and how would you get out? Do you in fact want to, or do you prefer to sink deeper into it, savoring its manifold ramifications and outlying distortions?

The teeming image-clusters of The Green Fog, made even more eerie and lyrical by Jacob Garchik’s score, capture the delirium of cinephilia, reminding us of how much a masterpiece owes to anonymous, banal visions pulsing through popular culture.

Right here in River City

William Brinton and his wife Indiana were a colorful couple. They were nudists and kept a mummy in their living room. More to our point, around 1900 they ran an Iowa theatre and traveled throughout the midwest showing films and lantern slides. Brinton died in 1919, Indiana in 1955, and the executor of her estate in 1981.

The Brinton collection passed to Michael Zahs–junior-high history teacher and confessed “saver” of things. Three truckloads of boxes came to Zahs labeled “Brinton crap.” They contained over 130 films, 700 magic-lantern slides, many sound recordings, and a host of vintage equipment.

Zahs was told to bury the nitrate materials and dispose of the rest. Instead he hung on to everything, and eventually the American Film Institute and the Library of Congress selected several reels for preservation. Since 1997 16mm copies of Brinton titles have been shown in festivities at the Graham Opera House in Washington, Iowa–a site recently declared by the Guinness Book of World Records to be the world’s oldest surviving film venue. The University of Iowa Library has committed to keeping safety copies of the entire collection.

This fascinating story is brought to light by Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherbourne of Northland Films. Saving Brinton is, like Bill Morrison’s Dalton City: Frozen Time (reviewed by Kristin here), a heroic tale of cinema lost and refound. Morrison’s film centers on 1910s and early 1920s features, but the Brinton legacy takes us back to earlier times. There are “actualities” (newsreels) and gag reels and even–watch Serge Bromberg’s eyes light up–a lost Méliès. Many items are in superb condition, with well-preserved hand-coloring. There are films from Lumière, Edison, and other major companies. In one, a powerful panning shot shows Teddy Roosevelt parading down Market Street in San Francisco (without green fog) just before the earthquake. And then there are the projectors and paper, including a Pathé catalogue.

Saving Brinton is as much a portrait documentary as an account of film rescue. The Brintons stand out, not least for William’s fascination with airships, but the star of the present-day show is Michael Zahs. With his Darwinian beard and jovial presence, he comes across as one of those impresarios who knows a lot about everything, from chemistry to grave marker symbolism. For four years the filmmakers followed his efforts to preserve and show the Brinton legacy, while also tracing his personal life. We get scenes of his devotion to his ailing mother, who died during filming, and interplay with his wife, a smiling woman who doesn’t mind sharing her household with combustible materials. At the same time, this packed documentary evokes the community that welcomed Zahs’ cheerful obsession. As a graduate of the University of Iowa, I had to beam at the sheer niceness radiating from these people and their town and the earth they steward.

On 23 April the University Library in Iowa City will be screening the whole collection, with seven projectors running the films on loops. You can sample them online, in pretty copies. And Saving Brinton will continue to tour festivals; you can track its progress here. This charming documentary is a must-see for everybody who loves old movies, not to mention flyover Americana.

My quotation from Geoffrey O’Brien’s The Phantom Empire: Movies in the Mind of the 20th Century (New York: Norton, 1993) comes from p. 28.

The Saving Brinton website gives more information on the film. Diana Nollen’s story in The Gazette supplies helpful background. Watch the trailer and glimpse our old friend Rick Altman, emeritus at the University of Iowa.

The Language of Flowers (n.d.).

Wisconsin Fim Festival: An unexpected gem, a Zucchini, and a farewell

Clash (2016)

Kristin here:

Three more films from this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival.

Clash (Eshtebak, 2016)

David and I were intrigued by the festival’s program notes describing Egyptian director Mohamed Diab’s second feature, Clash, as taking place with the camera entirely confined to the interior of a police paddy-wagon. This kind of limitation can be a fruitful device, as it was in the Israeli film Lebanon; there the action took place inside a military tank. Clash turned out to be a real discovery, the best film I saw at the Festival (putting aside A Quiet Passion, which we had already seen at the Vancouver International Film Festival.).

Diab’s paddy-wagon has the advantage of rows of barred windows and a door, so that we can frequently see what’s happening outside. The film is set in the summer of 2013, when there were protests, often turning violent, in the wake of the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi and his replacement by the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The truck moves through Cairo, encountering waves of such protests, and it gradually fills with a collection of people with various religions, beliefs, and cultures–supporters of Morsi’s party, the Muslim Brotherhood; others who oppose him; Christians; a homeless man; a nurse; and two journalists–with arguments and violence erupting inside the vehicle as well as outside.

Diab had to tread a fine line in his depiction of these people, since his basic theme is that they all must learn to cooperate to some extent if they hope to survive the baking heat, tear gas, gunfire, police bullying, and the anger of the mobs outside the truck. Officially the Muslim Brotherhood is considered a terrorist organization in Egypt, though Diab manages a fairly even-handed treatment of its members and supporters. Remarkably the censors did not require any changes to the film.

Just as remarkably, Diab was able to stage huge, convincingly terrifying riots in Cairo’s streets and highways (above). In a brief interview at Cannes last year, where Clash was shown in the Un Certain Regard section, he was asked if the shoot was difficult.

Very. You are risking your life because people might mistake the shoot for a protest, or might mistake you for the police. And there are haters of both, who can shoot you. It took us months of preparation. Egyptians to whom I’ve shown the film are blown away because they know that what we did is almost impossible.

He makes similar remarks in a question-and-answer session at the London Film Festival; his discussion of the film’s techniques comes from about 9:30 to 13:50.

The characters in the truck are constantly in danger, both from each other and from the rioters, and the action is absolutely riveting. There are a few lulls to vary the pace and to allow the prisoners to deal with their wounds and try to work out a strategy to protect themselves, but otherwise the suspense is maintained at a high level. A climactic scene in which rioters attack the truck, flashing laser pointers into it and trying to tip it over is handled, as Variety‘s review put it, with “brilliantly choreographed pandemonium.”

Clash was a huge success in Egypt. It was released in France in September and is already out on region 2 DVD (French subtitles only) there. Its festival life seems to be drawing to a close. It’s due for theatrical release in the UK and Ireland on April 21 and presumably will come out on Blu-ray and/or DVD. You can get a good sense of the film from the online trailers, the European one and especially the Egyptian one, though the film is not nearly so fast-cut.

My Life as a Zucchini (Ma vie de courgette, 2016)

2016 was a good year for animation. Kubo and the Two Strings, The Red Turtle, Moana, and Finding Dory were excellent as well. (I thought Zootopia was overrated.) Add My Life as a Zucchini to that list. This being Madison and the Wisconsin Film Festival being a university-sponsored event, we saw it with French subtitles rather than dubbed.

The style of the film, with its bright colors and cute, big-headed characters (above and at the bottom), makes it seem aimed at children, and the story is presented almost entirely through the viewpoints of Zucchini and the other children he meets. Yet children younger than teenagers would probably find parts of it incomprehensible or disturbing. The boys indulge in naïve but somewhat explicit speculation about sex. Zucchini’s beer-swilling mother apparently dies in an accident that he inadvertently causes, though this happens offscreen. He is taken by a sympathetic policeman to a small home for young children in the countryside. Not all are orphans, as it is made clear that one girl was taken away from her sexually abusive father and some of the others come from homes ruined by addiction or violence. Zucchini gets bullied and teased before finally being accepted.

All this makes for a strain of melancholy running through the film, but there is considerable humor to counter it, and the ending is happy.

Like Kubo, My Life as a Zucchini is puppet animation. Clearly it was done on a much lower budget, without the laser-printed changeable faces that make Laika’s characters so expressive. Charmingly, if distractingly, the clothes of the puppets occasionally shift positions, betraying the handling by the animators between frames–as when the red star on Zucchini’s T-shirt inadvertently takes on a life of its own. But on the whole, the filmmakers have used simple means to give their figures considerable expressivity.

The nomination of My Life as a Zucchini for the Best Animated Feature Oscar came as something of a surprise. Foreign films do show up in that category, but this one had its widest American release in a mere 53 theaters. It came out on February 24 and is still in 22 theaters, having grossed $286,154 as of April 6. (Presumably that does not count the two WFF screenings; the one we went to was sold out.) The DVD and Blu-ray versions are available for pre-orders on Amazon. The description says that both the original French-language soundtrack and the English-dubbed one are included.

Afterimage (Powidoki, 2016)

Afterimage premiered at the Toronto Film Festical almost exactly a month before the death of director Andrzej Wajda. It deals with the co-founder of Polish Constructivism, Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who helped create the Blok group in Warsaw in 1923. The plot covers only Strzeminski’s last years, but we get a strong sense of his entire career through gallery scenes displaying his work.

Socialist Realism was imposed upon Polish artists after the country came under the sway of the USSR in the wake of World War II. The film’s action starts with Strzeminski’s being fired in 1950 by the Ministry of Culture and Art because he refused to adhere to the doctrine. We see his stubborn resistance and the attempts by his adoring students to help him find respect and other work. Up to his death in 1952, he is oppressed by intransigent officials bent on denying him even the most demeaning jobs.

Reviewers have treated Afterimage with the respect due a veteran auteur late in a six-decade-plus career, but they deem it to lack the energy and appeal of his earlier work. Certainly compared with Wajda’s films of the 1950s and 1960s (we’ve commented briefly on two from the 1960s), Afterimage is a fairly conventional film. It’s beautifully made, as Wajda clearly had a considerable budget to recreate the historical look of Soviet-era buildings and streets of the early 1950s. To anyone unfamiliar with the impact that Socialist Realism could have on the avant-garde artists in the USSR and elsewhere starting in the 1930s, the film provides a vivid example. The film also contains an excellent performance by Boguslaw Linda, perhaps best known as the lead in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance.

Strzeminski, being the victim of persecution from almost the beginning, automatically becomes a sympathetic character. He also lost an arm and a leg in 1916 during World War I. (The budget is on display again in the fact that undetectable special effects removed Linda’s own arm and leg.) It is hinted that if he had been grievously injured in World War II, some allowances might be made, but having it happen during the Tsarist war of the pre-revolutionary era earns him no credit with the officials.

Yet Strzeminski loses some of our sympathy through his treatment of his teenage daughter Nika. She is interested in his art, closely examining the “Neoplastic Room” he helped create in the Lodz Museum–just before it is dismantled and put into storage as part of Strzeminski’s punishement. Nika also tries to help her father, cooking for him and trying to get him to cut back on smoking, but his ingracious rejection of her efforts helps drive her to live in a girls’ dormitory near her school. He remarks matter-of-factly after Nika leaves, “She will have a hard life.”

Our thanks to Graham Swindoll of Kino Lorber for help with this entry. As well, of course we owe a debt of gratitude to the WFF programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

My Life as a Zucchini (2016)