Archive for the 'Festivals: Wisconsin' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Sometimes a camera movement . . . .

A Quiet Passion (2016).

DB here:

. . . . sums up what has happened and hints at what’s to come.

Seeing Terence Davies’ splendid A Quiet Passion again at our Wisconsin Film Festival brought out several subtleties I hadn’t registered on my first pass last year at Vancouver. Among the things I appreciated was a poignant 360-degree-plus tracking shot in the Dickinsons’ parlor.

This poet’s passion isn’t always so quiet. Davies’ earliest films are notably light on dialogue, but this one contains plenty of talk, both bantering and brutal. Perhaps most surprisingly, the supposedly withdrawn Emily Dickinson engages in snappy and snappish exchanges with friends, family, neighbors, and one awkwardly sincere suitor. All the more striking, then, when Davies halts the talk and gives us a suite of images accompanied by discreet sound effects, music, and voice-over portions of Dickinson verse.

Fairly early in the film, we get a spirited exchange between the censorious Aunt Elizabeth and the Dickinson family. After her indignant reply to their mock-heathen teasing, she gulps down some currant wine. Next we see the family quietly sharing an evening. That’s when we get this ripe circular camera movement.

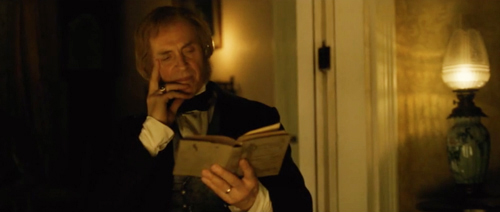

It starts framing Emily, reading by firelight. She looks left.

As the camera coasts past Emily we get a glimpse of a fond smile. The moving frame reveals Aunt Elizabeth, struggling to keep her eyes open.

In the course of this movement, over the soft crackling of the fire and a ticking clock, we hear the older Emily’s voice-over reciting.

The heart asks pleasure first,/ And then, excuse from pain;/ And then, those little anodynes/ That deaden suffering.

The poem is a famously puzzling one. Is the speaker suggesting a bargain–if not pleasure, then no pain, please? Or is it a description of the course of a life: youth seeking pleasure, old age willing to accept absence of pain, and in the end a plea for something that simply ends suffering? The juxtaposition of young Emily and aged Elizabeth suggests two phases of woman’s life: Is Emily still pledged to pleasure (of a bookish kind) while her aunt is already seeking an anodyne, like the brandy she greedily gulped and the sleep that seems to be stealing over her?

As the camera passes Aunt Elizabeth, the poem is completed.

And then, to go to sleep;/ And then, if it should be/ The will of its Inquisitor,/ The liberty to die.

Elizabeth’s drowsiness comes to prefigure the death that will haunt the rest of the film. And the poem’s grim acceptance of physical decline, lifted by the mercies of death, sketches what will be all too vivid in scenes to come.

The camera continues its leftward survey of the family circle, settling next on Emily’s father Edward. He’s thoughtfully reading. So is brother Austin, at the rear table. Sister Vinnie, though, is sewing at the same table.

This survey of the immediate family shows Emily, like the men, gone all literary, while good-hearted Vinnie does no reading, instead attending to women’s tasks. The shot identifies Emily as, if not unfeminine by the standards of the day, at least not sunk in domesticity. She may be searching for that literary spark she will so often identify with glimpses of Eternity.

The view of Edward has been accompanied by clock chimes, and under the image of Austin and Vinnie we hear the clock start to strike the hour of nine. As the camera moves leftward, we see the mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson.

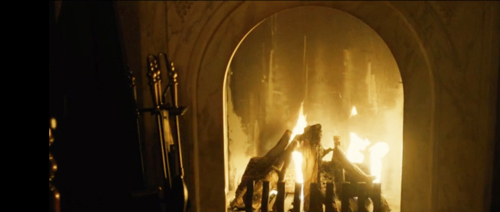

Neither reading nor tending to domestic tasks, Mrs. Dickinson is staring raptly into the fire. Everyone is in a kind of reverie, but hers is inward and melancholy. In the previous scene she has told Aunt Elizabeth “I prefer to listen and remain silent.” Later in the film we’ll learn that she has gradually withdrawn from the family, as if feeling ill-adjusted to these intellectuals, or through some private unhappiness. Later in the scene we’ll get another hint, but after briefly lingering on her, now the camera moves to the fire and then passes beyond.

The piano will be the site of a crucial conflict to come, and the wine decanter, already featured in the scene before, will later be one index of the self-righteousness of the new clergyman’s wife. This “empty” stretch becomes a caesura before we get to the simple, devastating final image of the shot.

So much for books. Emily’s plaintive look, not clearly fastened on any family member, is ambivalent. Has the camera traced her eyes around the family circle, as her sidewise smile at Aunt Elizabeth suggested earlier? If so, what has moved her? Her mother’s solitude? Her siblings’ and fathers’ obliviousness to the older woman? Or is it something more self-centered? Locked within the family circle, has she surveyed the perimeter of her life to come?

The question is partly, teasingly answered, when we hear the offscreen voice of Mrs. Dickinson. She asks Emily to play one of the old hymns. Emily rises and goes to the piano, and we get a cut to the shot surmounting today’s blog entry. After Emily starts playing, the rest of the family is forgotten, and Davies cuts to a closer view of her mother.

Still staring into the fire, she speaks of hearing the hymn sung by a young man with a beautiful voice. He was only nineteen when he died, she tells us, or maybe just herself. The softly delivered memory carries more than mere nostalgia. Are the others even noticing? We never find out.

Unlike her husband and children and Aunt Elizabeth, the mother ponders the past and its losses. We’re invited to imagine an alternative life for her, perhaps with the beautiful young man. Is he kin to the young woman in white with the parasol recalled by Bernstein in Citizen Kane, as he stands before his roaring fire? At the least, this warm parlor is now haunted by death.

Davies is too tactful to push this moment, leaving the character to keep her own counsel. But I can’t resist another probe. The Magnificent Ambersons is one of Terence’s favorite films, he told us during his visit (“better than Kane“). It’s not a stretch to let the image of Mrs. Dickinson remind us of the somber shot of Major Amberson before another fireplace. Deprived of his fortune, baffled by all around him, he ponders the origins of life as the narrator muses that even an Amberson might not get a leg up in the Hereafter.

Terence pointed out to us that the great American films are often about families, because in that setting passions are both aroused and contained. The Dickinson family, tightly bonded by love and respect, ruled by a tender but iron-willed patriarch, harboring a mother and daughter withdrawn from the world, split by failed marriages and angry reproaches, prey to death and broken pledges, is no perfect haven. Perhaps Emily’s stabbing epiphany is a realization of all of that, and what it might mean for her art. All this takes two minutes and ten seconds.

Nowadays the circling camera is a cliché; characters sitting around a table or even just standing in the street seem to be spinning on a turntable. Davies is far more discreet and precise. Step lightly on this narrow spot, a Dickinson poem advises us, and that’s what his camera has done here.

Thanks to Bianca Costello and Music Box Films, which is distributing A Quiet Passion. Its US rollout starts 14 April. Thanks as ever to the Wisconsin Film Festival and its plucky programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

And many thanks to Terence Davies for coming to town and providing fine conversation about George Butterworth, Meet Me in St. Louis, and the making of A Quiet Passion. As he told our audience: “I hope you enjoy it, and if you don’t, complain to Mr. Trump.”

Other entries in the intermittent Sometimes. . . . series are here (I Topi Grigi), here (The Mormon’s Victim), here (A Touch of Zen), here (Side Street), and here (Frisco Sally Levy).

Kristin and Terence Davies.

Wisconsin Film Festival: Retro-mania

The Gold of Naples (L’oro di Napoli, 1954).

DB here:

With the growing popularity of subscription streaming services, I suspect that film festivals will need to amp up their retrospective offerings. I was very surprised that a good film like I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, which would in earlier years have played arthouses, had no theatrical release. Despite its acclaim at Sundance, it went straight to Netflix online. True, Amazon has shown great willingness to port its high-profile titles to big screens. But by and large, as Netflix, Amazon, and other services produce and buy up new films, I suspect that festival premieres of indie titles will become more and more a display case for streaming. See it this week at our festival, and next month online!

It must be dispiriting for filmmakers hoping for theatrical play. Yet this crunch may oblige festival programmers to emphasize archival and studio restorations. These rarities are unlikely to show up on streaming any time soon, and festival screenings can build a public for them—so that they may eventually come to DVD or subscription services.

Case in point: Several restored titles at our Wisconsin Film Festival drew sellout crowds.

AMPAS comes through

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

I did manage to squeeze into another Academy restoration, Howard Hughes’ Cock of the Air (1932). The film amply showcases Hughes’ two principal concerns, aviation and the female mammary glands. (I guess technically that makes three concerns.) It’s a minor-key Lubitsch switch in which priapic flyboy Chester Morris pursues sexy Billie Dove, who’s resolved to bring his ego crashing to earth. We get lots of nuzzling, murmured double entendres, and scenes of passion quickly doused by the woman’s coquettish withdrawal. I thought the plot thin, needing a romantic rival or two, but the leering pre-Code stuff is good dirty fun. The high point comes when Billie encases herself in a suit of armor and Chester arms himself with a can opener.

The direction is credited to Tom Buckingham, a lower-tier artisan, but it seems possible that parts of the film were handled by Lewis Milestone, who contributed the original story. The first couple of reels are very flashy, with odd angles, complicated tracking shots, and bursts of rhythmic editing. They’re typical of Milestone’s showy, sometimes showoffish, style in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and The Front Page (1931; also shown at WFF).

Cock of the Air encountered heavy censorship, with the can-opener episode entirely snipped from the release version. The Hays Office even provided local censor boards with guidance for further cutting. When Heather discovered a pre-censorship print at the Academy—an exciting find—she discovered that the offending footage was there, but the soundtrack portions were lost.

Heather proceeded to hire actors to voice the parts in accord with the script and the onscreen lip movements. The results are sonically smooth, but in the spirit of fair dealing, the bits of replacement are marked with a discreet bug in the lower right corner of the frame. This is a nice piece of archival integrity. Heather also showed an informative short on the restoration of this engaging piece of naughty early sound cinema.

Of incidents and non-incidents

The Incident (1967).

Two other pieces of film history got fitted into place with the revival of Larry Peerce’s One Potato, Two Potato (1964), a classic of American social-problem cinema, and the rarer The Incident (1967). This latter glimpse of mean streets creates what screenwriter David Koepp calls a Bottle, a tightly constrained space in which the drama plays out. Here the Bottle is a subway car in which several people, a cross-section of New York life, become the playthings of two young thugs, played by Tony Musante and Martin Sheen.

Starting by gay-bashing and culminating in a charged racial confrontation, the subway conflicts sought to show how the solid citizens can’t summon the will to respond collectively—even when they take their turn under the thugs’ lash. It was intended as a response to the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese, whose screams were mostly ignored by her Queens neighbors. (A recent documentary, The Witness, revisits the case.)

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

A believer in improvisation, Peerce rehearsed different groups of actors separately, then brought them together to let some natural friction emerge. He encouraged them to add to the script and build immediate reactions—so immediate that Thelma Ritter, a veteran unused to improv methods, responded to Musante’s goadings by slapping him. All this is captured in a superheated style of fast cuts, big close-ups, and screeching sound. It’s a white-knuckle ride that retains its power. I hadn’t seen it since 1970, but the violent climax, utterly earned, is disturbingly contemporary. The film’s final moments are being replayed, in reality, all over America as you read this.

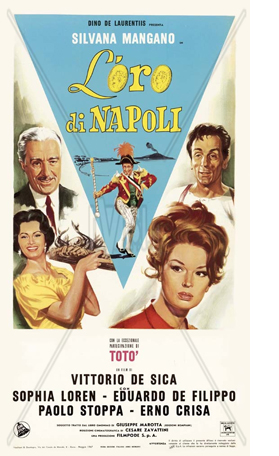

The nicest surprise of my retrospective viewing was The Gold of Naples (1954). Studded with big names (Ponti and De Laurentiis, Totó and de Sica, Silvana Mangano and Sophia Loren), it has sometimes been thought to be one of those lightweight Italian comedies that represent a quiet refusal of the Neorealist impulse. On the contrary, it proves to be a bold contribution to block construction, here in the omnibus genre. Several stories are laid end to end, exemplifying the vivacity and poignancy of life in Naples’ back alleys.

One story has a tight, shocking arc: the tale of a prostitute (Mangano) who thinks she’s marrying for love until she learns her new husband’s guilt-ridden sadomasochistic motives. The finale is a scrappy anecdote, in which The People give a local plutocrat the ultimate vocalization of disrespect.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

Above all, in an episode cut from the original American release (and missing from this poster, though at the top of today’s entry), a mother follows her son’s coffin driven through the street. She throws wrapped candies for children to pick up. That’s it. No flashbacks to life with her boy, no dialogue telling us how he died, no colorful secondary characters to provide that life-goes-on final note. It could be called “The Incident,” though nothing more unlike the fever-pitch drama of Larry Peerce’s film could be imagined.

According to screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, a Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

The lack of a dramatic peak, to which a normal scene would build, can force our attention to downshift to the minutiae of moment-by-moment action, or rather micro-action. That’s what happens in this sequence of The Gold of Naples, which Zavattini helped write. Every gesture and glance becomes potentially, but ambiguously, significant. De Sica’s patient recording of a very thin slice of life is as radiantly unpretentious a model of “pure Neorealism” as anything to come from the 1940s.

This is just a glimpse of the delights among the 150 screenings that are gracing our eight-day film festival. (We’re now the largest university-sponsored festival in the country, though probably not in budget.) Details of this magnificently programmed affair are here. We’ll blog again soon.

Thanks to the programmers Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King, along with all the institutions, wise elders, community supporters, and volunteers that make WFF fun. You can browse earlier reportage from this event here.

You can also see the restored Front Page (1931) in Criterion’s new His Girl Friday DVD release. On Cock of the Air’s censorship travails, see the AFI site. It will be screened very soon at the TCM Festival. Also set for the TCM festival is The Incident, which will screen later in April at Film Forum. Mike Mashon gives more information on Aloha Wanderwell in his LoC blog.

How wrong I was to miss booking The Gold of Naples when I ran a film club in college and good old Audio-Brandon offered it. Even without the funeral scene and the up-yours finale, it would be worth seeing. Now no version seems available in the US; WFF director Jim Healy brought a print from Italy. It would be perfect for FilmStruck.

Read…watch movie…grab food…read…watch movie…

Alexander Payne’s vividly shot reality

Election.

Kristin here:

Both David and I missed almost all of this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. I was in Egypt wearing my archaeologist’s hat and working on ancient statuary, and David was attending the Hong Kong International Film Festival. (See his reports, here and here.) Luckily we made it back just in time for Alexander Payne’s spring visit to Madison.

I first met Alexander at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna. He already knew who I was from having read Film Art: An Introduction, and we started chatting. We were in a small crowd outside the Arlecchino cinema, where a screening was running late. I asked Alexander what he had seen at the festival that he liked. He said he had come from a screening of Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm and thought it was a masterpiece. Right away I knew that this man has impeccable taste in movies. (Alexander further proved this during his recent visit, saying that his favorite three films of Il Cinema Ritrovato were Ingeborg Holm, Naruse’s Wife, Be Like a Rose, and Rossellini’s Il Generale Della Rovere.)

I first met Alexander at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna. He already knew who I was from having read Film Art: An Introduction, and we started chatting. We were in a small crowd outside the Arlecchino cinema, where a screening was running late. I asked Alexander what he had seen at the festival that he liked. He said he had come from a screening of Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm and thought it was a masterpiece. Right away I knew that this man has impeccable taste in movies. (Alexander further proved this during his recent visit, saying that his favorite three films of Il Cinema Ritrovato were Ingeborg Holm, Naruse’s Wife, Be Like a Rose, and Rossellini’s Il Generale Della Rovere.)

Alexander is a friend of Jim Healy, head programmer for the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cinematheque screening series and of the Wisconsin Film Festival. Jim seems to know half the people in the film industry as well as in the festival and archival spheres; he has already brought Tim Hunter and Joe Dante to campus. I knew he hoped to bring Alexander as well, so I put in a pitch for the idea, mentioning how enthusiastic the film students and buffs are in Madison and how he would enjoy speaking with audiences here, who would ask interesting questions. Luckily for me that turned out to be true, a mere nine months later. (Left, Alexander and Jim in a local Madison burger joint.)

Alexander Payne, cinephile

Alexander participated in a number of events here in Madison, some associated with the Wisconsin Film Festival and others with the Department of Communication Arts. The first was a session of our divisional film colloquium, which  began with David and Alexander in discussion onstage (right) and then opened for questions from the faculty and graduate students.

began with David and Alexander in discussion onstage (right) and then opened for questions from the faculty and graduate students.

The conversation began with Alexander recalling how he fell in love with movies, which he reckons happened at about the age of four. He watched mainly older movies. In those days there were rival houses in his hometown of Omaha. His father owned a restaurant in Omaha, and for some reason one of his suppliers, Kraft, gave him a regular-8mm movie projector. Alexander started collecting films, buying prints initially from the now defunct Castle company and later from the still functioning Blackhawk Films.

These included all twelve Chaplin shorts made at Mutual. Many years later, Alexander supported the restoration of the last of that set, The Adventurer. That’s what had brought him to Bologna. He introduced the film, which was shone as one of several new restorations in the Essanay/Mutual Project of the Fondazione Cineteca Di Bologna and Lobster Films. (See here for information on the project and program notes for this year’s screenings.) It was screened at one of the 10 pm programs in the Piazza Maggiore, with Sjöström’s The Outlaw and His Wife, also newly restored.

Jumping back to Alexander’s progress as a cinephile, he became an undergraduate at Stanford, studying history and Spanish. From there he moved on to UCLA for an education in filmmaking, and “thought it was heaven.” He loved it so much that he delayed starting his filmmaking career and stayed on to see more film’s in the famous Melnitz Hall screening room. In those days, 35mm prints were regularly shown, including nitrate originals. (Probably around ten years ago I saw a nitrate print of Trouble in Paradise there, being shown for a class. It definitely was heaven.)

There he recalls seeing such things as an Antonioni retrospective and Double Indemnity. When he was in his 30s, he fell in love with Italian and Japanese cinema. Now that he has reached his 50s, he has broadened his interests to study the films of Hollywood directors like Michael Curtiz and Raoul Walsh. He admires the conciseness of their films: “Film,” he says, “is a constant search for economy.”

Alexander’s love of Italian films was in evidence at one of the final events of the Wisconsin Film Festival. He had been asked to choose an older film that he could introduce and answer questions about afterward. His choice was Il Sorpasso (1961, Dino Risi). The auditorium at our local arthouse multiplex, Sundance 608, was packed with a very enthusiastic audience indeed. (Left, Alexander after being introduced by Jim Healey.)

Alexander’s love of Italian films was in evidence at one of the final events of the Wisconsin Film Festival. He had been asked to choose an older film that he could introduce and answer questions about afterward. His choice was Il Sorpasso (1961, Dino Risi). The auditorium at our local arthouse multiplex, Sundance 608, was packed with a very enthusiastic audience indeed. (Left, Alexander after being introduced by Jim Healey.)

The next evening, Alexander did the same for a screening of Nebraska at Union South. Again a full house, and again an audience eager to ask questions.

In between such events, we shared some restaurant meals. Alexander, Jim, and David sounded like some contrapuntal version of the Internet Movie Database, tossing titles, directors, and other film credits back and forth.

During these conversations, and indeed every other conversation we had with him, Alexander would pull out a small pocket notebook (though paper napkins sometimes substituted) and write down any intriguing-sounding title of a film he hadn’t seen. Not only a cinephile, but a systematic one.

Not surprisingly, during the colloquium discussion the issue of Nebraska being shot in black-and-white came up. David mentioned that Bong Joon-ho had said to him (while they were both jury members at this year’s Hong Kong Film Festival) that every director wants to make a black-and-white movie.

Given his love for older films, Alexander considers that “Our great film heritage is black and white.” Inevitably, during the press junkets for Nebraska, reporters asked him why he made the film in black and white. What he wants to know is, “Why is that the first question?”

Alexander agrees with Bong: “I don’t think a director is really a director until he or she has made a film in black and white.” He approached Paramount with the idea of making Nebraska as a black-and-white film and argued that it would be viable because it had a low budget of $12 million. He adds that directors have faced the same arguments against black and white since the 1970s, as when Peter Bogdanovich was making Paper Moon. The TV contracts specify color.

Alexander wanted to shoot Nebraska on film, but the only black-and-white stock available had an ASA of 200, which would not be effective for night shooting. He had to shoot digitally and add contrast and grain afterward to get a film look.

He definitely regrets the loss of film, which he considers superior to video: “I think flicker will always be superior to glow.”

Alexander says he is a big fan of the 1970s because he was a teenager at the time. He thinks that a lot of films made then and released into regular theaters could not be shown today outside arthouses. Films then were judged by their closeness to reality, not their distance from it. For him, “There’s just a consistently fine product being turned out between The Graduate [1967] and Raging Bull [1980].”

It was the period when a generation of filmmakers came to prominence, filmmakers who today are the grand old men of Hollywood. David pointed out that Alexander has often been mentioned as part of a later generation that included such directors as Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson. Alexander agreed that there was the “Class of 1999” that included films like Election and Fight Club (putting David Fincher in the same group). He says of these directors, “We’re friendly enough.” But he envies the Spielberg, Coppola, Scorsese, Lucas generation because they were able to help each other out in filmmaking. His generation doesn’t socialize much, though he said he had seen Soderbergh recently.

The Milos Forman of Nebraska

For anyone who had been unaware that Payne comes from the vast territory in the middle of the USA that encompasses the Midwest and Great Plains and is generally known as Flyover Territory, his latest film makes that point clear. He was born and raised in Omaha, and still lives part of the year there. As he explained in the colloquium discussion, “I’m one of those people in the arts who are interested in exploring where they’re from.” This is not to say that all of his films are set in Nebraska, but four of the six features take place there, explicitly or implicitly.

Citizen Ruth has no identifiable setting, as far as I could tell, though its milieu is clearly centered in small-town life in the country’s midsection. It was shot in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha. Election doesn’t stress the fact, but close shots of newspaper stories reveal that its story is set in Omaha. Warren Schmidt lives there as well, and his road trip to his daughter’s wedding takes him to Denver and brings him back home. Payne’s next two films were set in quite different parts of America: Sideways in San Diego and California wine country and The Descendants in Hawaii. Nebraska chronicled David Grant’s journey with his father Woody from Billings, Montana, to Lincoln, taking in several rural and small-town locations along the way.

Each story mixes humor and pathos, including both satirical swipes at locals and great affection for them. It’s hard to pin down their genres. (The Internet Movie Database classifies About Schmidt as a comedy/drama and Nebraska as an adventure/drama.) In the colloquium, Payne remarked of Nebraska, “I call it my own Czech Republic. I get to make Milos Forman films about it.”

It is a cliché to say that the settings in which a film’s action takes place become a character in the drama, but Payne’s films really do manage to keep us aware of the surroundings to surprising extent. Payne says that when he discusses a film with his cinematographer and production designer, he says he wants “Vividly shot reality.”

Vivid can simply mean beautiful, and there are many such landscapes, as in The Descendants:

But it need not mean that. The choice of framing in the opening scene of Election, with the fence in the foreground and the school crouched ominously high on the hill tend to make it look like a prison:

Emphasis on locales can be created by something as simple as a slight wide-angle lens that adds dimension to a house, making it more prominent within its surroundings, as in The Descendants, About Schmidt, and Nebraska, where the vegetation framing the building, ranging from lush to ordinary to sparse, help define the homes of the main characters:

To achieve the desired vividness, Payne often chooses to use real interiors, even if that limits the types of set-ups he can make. The result can be busy but spacious and attractive, as in The Descendants:

Or the constraint can turn to an advantage, as in the confined arrangement filmed from a television’s point of view for the “That Impala you used to have …” long take in Nebraska:

This latter scene exemplifies something else that Payne considers crucial for achieving realism: the addition of extras and small roles, often played by non-actors found in the area where location filming is occurring.

Alexander sometimes uses symmetry to make a fairly ordinary locale more vivid, as in these planimetric shots from Sideways and About Schmidt:

Vivid shots can make a thematic point, as in The Descendants. Shots of Matt and his daughters being driven through their unspoiled ancestral land lead to a view of them being driven up to the sort of elegant resort that could be built on that land if they sell it. The second shot is pretty and well composed, but the juxtaposition with the series of shots that preceded it should make us sense it as slightly menacing as well:

I’ve stuck mainly to long shots here, since that’s where the vivid realism tends to come. There are many unusually close views of characters as well, which contrast with these long shots. There we tend to get the psychological side of these films, which are basically character studies. This contrast may be what gives Alexander’s films a sense both of place and of intense concentration on characters.

Alexander Payne, storyteller

We all know that Oscar wins and nominations don’t always go to the actual best films of the year. But they do reflect something about the reputation of a filmmaker within the industry. Alexander has had two films nominated for best picture: The Descendants and Nebraska. That these nominations are not simply the result of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science’s switch to a ten-nominee best-picture category is reflected in the fact that he has been nominated for best director three times: Sideways, The Descendants, and Nebraska. He and his co-writers have also been nominated three times for best adapted screenplay: Election, Sideways, and The Descendants. The only film which Payne did not co-write, Nebraska, received an nomination for best original screenplay, by Bob Nelson. All these nominations produced two wins, for the screenplays of Sideways and The Descendants. Clearly Alexander is recognized in Hollywood as a fine storyteller.

Apart from Citizen Ruth and Nebraska, all of Alexander’s films are based on novels. In the colloquium discussion with David, he said he prefers adapting novels, which are ready-made stories. He doesn’t have the original ideas, but he can deal with them almost like a documentarian filming an imagined reality. Most of the novels have been based on the authors’ own experiences, and most of them are regional. “You can find a world and have a dialogue with it.”

His sources are generally not well-known novels. None of the Jane Austen-style prestigious literary property here. Neither Election nor Sideways had been published at the point where he decided to adapt them. The Descendants was not a well-known book. As his first project out of film school, Alexander and Jim Taylor, who would collaborate on several scripts, wrote an original one about a retired man in Omaha. When no one in Hollywood was interested, they went on and made Citizen Ruth and Election. Once Election became a critical, if not a commercial, success, they were able to move on to a more ambitious project. In the late 1990s, Louis Begley’s novel, About Schmidt, was suggested to them as a possible vehicle for Jack Nicholson. They derived some elements from it, combining them with their earlier script. It was, by the way, Alexander’s most expensive film at $32 million, half of which went for Jack Nicholson’s fee.

[Thanks to Jim Healey for clarifying About Schmidt‘s origins; this paragraph has been re-written to incorporate the information he provided.]

Clearly he values the tight unity and narrative economy that are characteristic of the studio age of Hollywood filmmaking: “You want your screenplay as streamlined as possible.” That doesn’t mean following a formula, however. He considers that the screenplay manuals that have been so influential, like those of Syd Field and Robert McKee, “destructive.” He dislikes their blanket generalizations. David pointed out that Matt’s voiceover narration in The Descendants is used to provide exposition, but then tapers off at about the midway point. Alexander responds that manuals claims that voiceover should not be used, but that if it is, it should either be used throughout or only at the beginning and end. These strictures he considers absurd. (Interestingly, many classic studios films start with a voiceover that doesn’t return at the end.)

During the colloquium discussion, Alexander remarked, “I like films which are entertaining and charming.” It’s a generalization that could apply to classical studio filmmaking, and it applies to his films as well. These are well-made films made on the whole along classical lines. Their main characters have goals, struggle toward them, meet obstacles, and usually follow an arc at the end of which they have a sudden realization.

Those goals, struggles, and growth also follow a pattern that one could point to in making a case for a thematic consistency in Alexander’s work. These are mostly films where characters struggle against some misfortune or obsessive hatred and eventually come to some sort of reconciliation with their situation.

Warren Schmidt deals with retirements, the death of his wife, and the marriage of his daughter into a family that disgusts him. He concludes that his life has been an utter waste, and yet a sudden realization that a casual act of kindness has made a difference to another person (a six-year-old orphan in Africa whom he has “adopted” through a charity) rescues him from his despair.

In Sideways, Miles cannot accept that his ex-wife has left him and is about to remarry, and he also hopes to find a publisher for his unwieldy, long novel. Only after he accepts both the failure of his marriage and the impossibility of publication can he move on to a possible new romance. In The Descendants, Matt overcomes his rage over his comatose wife’s infidelity in time to bid her a sincere, grief-filled farewell before she dies. In Nebraska, David Grant struggles to convince his father Woody that his delusions, perhaps brought on by increasing dementia, are absurd, but he finally realizes that humoring the old man is a kinder approach for all concerned.

Election, being an early work, largely avoids this pattern. Jim conceives a hatred for Tracy that he never overcomes. He manages to pull himself together after the failure of his marriage and his firing from his high-school teaching post, finding a new romance and a modest job as a guide in a New York museum. Still, his last glimpse of Tracy as an apparently successful assistant to a major politician is resentful and dismissive, as he continues to view her as he had during her candidacy for student president. Here there is no reconciliation in the main plotline.

The films also tend to follow a well-balanced structure that at least sometimes conforms to the four-part structure I have outlined in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and in this blog entry. Election, for example, has a major turning point that comes halfway through: Tracy notices that one of her posters has begun to peel off the wall (see top), and her struggle to re-attach it leads her to lose control for once and destroy her opponent’s posters. It’s a moment that Jim could legitimately use to disqualify her as a candidate, but his own incompetence and her cleverness and ruthless resistance of his accusations ultimately lead to his failure and her success. The Descendants has a well-balanced four-part structure as well.

There is also a playfulness about these films that fits Alexander’s “entertaining and charming” description of classical films. Both Election and About Schmidt, for example, contain inserts showing the protagonists’ absurd visions of themselves as wildly successful, Jim as a Marcello Mastroianni-like sophisticate and Schmidt as a business tycoon:

What about the future? Alexander revealed that after Sideways, he and Taylor embarked on an original screenplay, which now has been revived as a current project. It would be a big-budget, effects-driven film. If the project comes to fruition, he dreads the prospect of doing storyboards for the first time. His devotion to historic films remains unchanged, however. He plans to be at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, where we hope to catch a meal with him and go on throwing favorite titles back and forth.

Why do reporters start by asking why Nebraska is in black and white? Having studied press junkets for The Frodo Franchise (see the section on frequently asked questions, pp. 123-132), I suspect that the studio is behind it. Basically publicity departments plant a small number of subjects they want reporters to talk about in the press releases, EPKs, and other items they use to guide the press. Reporters batten onto these as the things their readers would be most interested in, and they ask about them and write about them ad nauseum. All this means that filmmakers have to suffer through this same limited repertory of questions dozens, perhaps hundreds of times, struggling each time to say the same thing in a different way. The price of fame.

We have long included an example from Election in Film Art, where we quoted Alexander as a way of showing that directors deliberately set up patterns of motifs.

About Schmidt.

The Maestro of Chagrin Falls

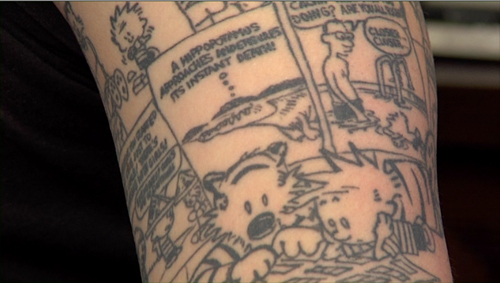

A fan’s tattoo, from Dear Mr. Watterson (2013).

DB here:

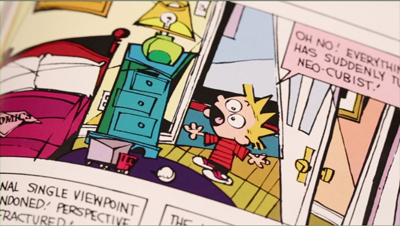

Bill Watterson, creator of Calvin and Hobbes, was probably the best cartoon draftsman since Carl Barks and Walt Kelly. His versatile line could be thick or thin, fluent or jagged. His coloring was rich, his layout experimental in the Herriman vein. His energetic picture stories provided zany humor and an unsentimental look at childhood imagination.

If Schulz treated kids as miniature adults, complete with obsessions and neuroses, Watterson saw Calvin as an adolescent in a child’s body, a rebellious teenager-to-be surrounded by adversaries and fools. Schulz’s Peanuts kids suffer in thin, wriggly lines, but Calvin’s mood swings from rage to rapture are rendered by manic exaggeration in the classic cartoon tradition. Meanwhile Hobbes, contrary to his name, exercises a gentling effect, becoming a tolerant Superego to Calvin’s Id.

Watterson was the Pynchon of cartoondom. His studio in Chagrin Falls, Ohio yielded a solitude rare for a publishing celebrity. He almost never appeared in public and seldom answered mail. In one of his rare public gestures, he criticized syndicate power, the tired old strips put on life support, and the scramble for licensing deals. Accordingly, he permitted no merchandising beyond book collections. Any Calvin and Hobbes toys or T-shirts or decals you see around you are DIY handicraft. After ten years Watterson simply halted the strip, an abnegation that drove his millions of admirers to despair. And he has remained reclusive.

Dear Mr. Watterson, which won a Golden Badger award at our Wisconsin Film Festival, sprang from Joel Schroeder’s fondness for the strip. He realized early on that interviewing Watterson wasn’t in the cards. So he set out to find ordinary readers who would testify to their love for Watterson’s creation. He found plenty of eloquent ones, but the movie is no mere fanboy indulgence. Schroeder’s travels took him to many of today’s top cartoonists, from Berkeley Breathed to Stephan Pastis, as well as critics and syndicate executives.

By outlining the shape of Watterson’s achievement in comics history, Dear Mr. Watterson mutes its admiration with regret, and not merely because Watterson quit at the height of his popularity. The film shows that, as one interviewee puts it, Calvin and Hobbes is very likely the last great comic strip.

Why? The conditions of publishing have a lot to do with it. As newspapers got thinner and smaller, the space allotted to comics shrank. Complex compositions and spacious storytelling became difficult in the slots allotted to Sunday strips, while the daily panel formats were minuscule. Only the sketchiest drawing survives the reduction.

The squeeze was starting in Schulz’s day: Peanuts was the beginning of the “minimalist” look of Cathy and Fox Trot. Watterson’s bold drawing style and appetite for scale posed problems for publishing. Ironically, as Schroeder pointed out in his Q & A, the sort of freedom and flexibility Watterson sought would become available a decade later on the Net.

Something else suffocated comics creativity. Just as tentpole films need an array of ancillaries, a successful cartoon demands the womb-to-tomb merchandising that Watterson foreswore. Children need to be hooked on the franchise before they can read. Garfield clothes and toys introduce infants to a pudgy beast that will stalk them throughout their lives, on lunchboxes and calendars and mugs and mousepads and refrigerator magnets and TV shows and “Is it Friday Yet?” placards for office cubicles. Watterson realized, I think, that being surrounded forever by leering images of cute creatures was one version of Hell.

Schroeder, a graduate of UW—Madison, has made a smart, touching movie. It deserves wide circulation and even, I should say, a PBS airing. It’s at once a tribute to a fine artist, a probe into comics history, and a revelation of how integrity can be maintained in the era of Monetization. Turning down hundreds of millions of dollars, Watterson in effect said something that almost no one imagines possible today: I don’t need that much money.

One observer comments that when Calvin and Hobbes ceased, many critics expected its fan base to dwindle, because it wouldn’t be maintained by all the spinoffs. Instead, parents pass down their Watterson paperbacks as family heirlooms. Fans have the lavish three-volume compendium of the strips, which is selling briskly on Amazon, while school libraries are replenishing their holdings of the slim anthologies. Our children are following the adventures of the hyperkinetic brat and his imaginary tiger in the best way: By reading books.

P.S. 2 May: Chris Blunk of Through a Glass Productions writes this followup:

Coincidentally, this past Sunday I met John Glynn, who works at Andrews/McMeel promoting their properties to Hollywood (such as Garfield and Over the Hedge). He was at the Free State Film Festival in Lawrence, Kansas where he showed the Sundance-boosted Small Apartments, also based on an Andrews/McMeel property. He was the first person I’d ever met who has any kind of semi-regular contact with Watterson. Though Watterson retains nearly all ancillary rights to his characters, A/M-Universal consults him on book printings, electronic distribution, etc.

While there were several tidbits that thrilled a fan like me, one item he mentioned particularly pertained to your article. He claimed that traffic at the Universal comics website (www.gocomics.com) is by and large driven by the Calvin and Hobbes classic – i.e. rerun – strips. The majority of visitors to all other comics on the site – including popular current strips like Get Fuzzy, Pearls Before Swine, Dilbert, etc, – arrive through Calvin and Hobbes.

So in addition to being propagated through handed-down book collections, as you pointed out, Calvin has managed to attract new fans and dominate comics circulation even in the new frontier of the web that grew into being long after Watterson’s retirement. And this with no new strips published in the past 20 years.

He told a couple other anecdotes that were similarly surprising. Such as a time in the early 90s when Spielberg was involved in some animation projects (Tiny Toon Adventures, Family Dog, Animaniacs, etc) and made inquiries about the rights to Calvin and Hobbes. According to Glynn, Watterson turned down a direct phone call with Spielberg himself reasoning they had nothing to discuss.

Thanks to Chris for his thoughts and information, and for reading our blog.

P.P.S. 16 July 2013: Gravitas Ventures announces that it will be releasing Dear Mr. Watterson on theatrical and VOD in November.

Dear Mr. Watterson.