Archive for the 'Festivals: Wisconsin' Category

Spring comes, bringing movies for Badgers

Good Bye (Mohammad Rasoulof).

DB here:

The thirteen years of our Wisconsin Film Festival have furnished plenty of high-definition moments. I’ll never forget Roger Ebert facing a crowd of a couple of thousand in the Orpheum Theatre to introduce A Hard Day’s Night, or Michael Snow explaining Corpus Callosum to a couple of hundred of the devout in our Cinematheque. We sponsored the first retrospective of Hong Sang-soo’s work—after he had made only three films—and he came along. Hundreds of young filmmakers have visited Madison with their independent works, while we’ve also sponsored some wonderful restorations of classics. Somehow spring always arrives right on time as people line up, chatting, to pass from sunshine into the darkness of our local movie houses, or to the many coffeehouses and pubs near the venues.

Some years the festival has clashed with the Hong Kong International Film Festival, and it’s always been awkward for me to leave Madison for the Fragrant Harbor. But this year, number 14, I can happily stay at home and let the festival come to me.

Roger Ebert and Meg Hamel, Wisconsin Film Festival 2006.

You can see what’s on offer here. Our programming team has gone the full distance for us.

This year’s guests include the distinguished experimentalist Phil Solomon (three programs, one curated by him) and Dan Levin, cognitive scientist and part-time filmmaker , who’s paying tribute to Joel Gersmann in a movie called Filthy Theater. We also have James Schamus of Focus Features. You know him as the award-winning screenwriter of many Ang Lee films and a founder of the Good Machine company, a bastion of bold independent cinema in the 1990s. His New York Times profile is here. James is giving a talk, “My Wife Is a Terrorist” on Thursday at 7:30, and it should be quite something: a narrative analysis of his wife’s Homeland Security file, including, he promises, meditations on redactions.

I thought I’d use today’s entry to signal to Madisonians, and anybody else who’s interested, some of the films that we’re showing that I’ve found worthwhile. In some cases, I supply links to write-ups on this site.

Monsieur Lazhar is a warm drama given astringency by its sudden bits of realism. The mysterious title character takes a teaching post in a primary school and must negotiate between corridor politics and students’ personal problems. Just enough sweetness, just enough toughness, and just enough of an uncertain ending to put it squarely in the Tradition of Quality. That isn’t meant as a complaint.

For me The Devil, Probably is second-tier Bresson, which means first-rate anybody else. People tend to forget that this spiritual director, his eyes supposedly lifted to the clouds and mists of holiness, was also resolutely secular. He was fascinated by young people and their way of being in the world, from the boyish Country Priest to the hapless Mouchette. Moving with the times, he gave us this reflection on post-’68 disenchantment with where things were going. I should see it again. Everybody should.

Good Bye (aka Goodbye) has a bit of Bresson about it. It’s an austere film concentrating on a woman lawyer forced out of her profession and up against a plethora of problems. Her past and present unfold gradually: Every scene has two levels, usually a mundane action that gradually yields hints about her husband, her unborn child, and her plans to leave Iran. A scathing portrait of a culture of bureaucracy, bribery, and surveillancer (the film was smuggled out of the country), Good Bye will stay with you. Kristin talks about it here.

Current, in my view wholly justified, admiration for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy should bring people to The Deadly Affair, Sidney Lumet’s intelligent version of A Call for the Dead. All have had their say about Guinness vs. Oldman as spymaster George Smiley, but what about a 57-year-old James Mason in the role? This time around the sexual jealousies underlying the recent Tinker Tailor are brought to the fore (the title is a pun), with Harriet Andersson as a ravishing Ann Smiley.

Another Brit retrospective item is Alberto Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well? Kristin spent a whole blog on this surprisingly grim study in complacency overcome by offhand heroism.

One of the very best films we saw at Vancouver last fall was Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (above), which we discuss a little bit here. Somber and mesmerizing, it coaxes you to pay attention. My kind of movie.

Speaking of Hong Kong, there’s one of Johnnie To’s latest, Life without Principle. This story of intersecting destinies during the European financial crisis spurred me to comment at some length here. To is, in my immodest opinion, one of the best directors working anywhere today, and a chance to see his recent work is really splendid. We have a 35mm print, and I’m tempted to go back and see it a third time.

Klown’s outrageous bad manners are perhaps a little too calculated, but this Danish dramedy from Lars von Trier’s company does catch you up. Laced with jokes about pedophilia and manly touching rituals, it seems at first glance a rough-edged bromance. Two pals and a nephew go on a canoeing trip aiming to end at an upscale brothel. After a string of slapstick disasters, the thing looks ominously like it might end in hugs and cheerful tears, but the biggest sting comes in the last few seconds. With a funny, offhand performance by musician Bent Fabric and a walk-on by Jørgen Leth (himself no stranger to outlaw sexytime).

Testosterone to the bursting point is no less on display in Policeman, a bristling, brutal examination of male bonding among Israeli cops. Although it builds to an incendiary action sequence, it’s mostly a study of how people of all classes and political cultures acquire an appetite for violence. Kristin wrote about it here.

Ben Rivers’ Two Years at Sea is a low-key, haunting piece. A portrait documentary? Semi-autobiographical fiction? Experimental film? All three, I guess. And in glorious black-and-white 16mm, which Rivers processes himself. Kristin gives it thumbs up here.

Finally: No film can portray the state of a country at a moment in history, but you’ll be thinking a lot about how today’s Russia might work after you see Elena. A character study of a woman whose ruthlessness is made reasonable and even sympathetic, a thriller centered on how to keep your enemies close, and a sociological study of the haves and have-nots in rapacious capitalism.

Because these are outstanding movies, several are listed as sold out. But some seats have been kept aside, and inevitably some who bought tickets won’t show up. The festival staff tell me that there will be a wait line for each show, and they’ll try to get everybody in. Me, I hope to watch at least a dozen programs, and I’ll try to blog about some in the afterglow. See you there?

Sleepless Night (Nuit blanche; Frédéric Jardin).

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.

Yes, we like it here at the Wisconsin Film Festival

Kristin here-

David has gone halfway around the world to attend a film festival and will be reporting more on what he sees in Hong Kong. But in Madison we have the Wisconsin Film Festival going on now, and there’s plenty to watch here as well, even if it’s only for four days rather than two weeks.

So far I have seen four films in two days and plan to see five more before the festival ends tomorrow night. That means that so far I’ve sat through the short festival prologue film that announces its sponsors four times. Each year we have a different little prologue film. This year director Meg Hamel and her team found a snappy promotional film for Wisconsin that looks like it was made in the late 1950s or early 1960s. Its slogan is “We like it here!” and it features not only our famous dairy and other farm products but also things which are fast disappearing from local industry–like cars and tractors. I’m not sure how I’ll feel about this little film after watching it nine times, but so far it’s amusing.

And our Wisconsin products have followed David to Hong Kong. Shopping for breakfast items in a local grocery store, he found some familiar fare:

We’ve served many a Johnsonville brat during our annual Labor Day cook-out. They look pretty good compared with the pale Chinese version juxtaposed in the photo. And a product from even closer to home, Bagels Forever bagels, which set up shop here in Madison a few years after we did:

Of course, we have Hong Kong imports here as well. I’ve got a ticket to see Johnnie To’s Sparrow tonight.

So far I’ve seen some excellent films. Agnès Varda’s The Beaches of Agnès was a salubrious way to start. It’s an autobiography of sorts, built around visits to the various seaside locales that have played a big part in her life, from childhood visits to the resorts of Belgium to an escape to Corsica to the fishing village that featured in her first film, the 1954 short feature La Pointe-courte to Venice in Los Angeles. Not that her tale is told chronologically. There are numerous diversions, such as meetings with the children who appeared in that first film, now grown old. There are clips from her films and encounters with friends. Varda even managed to get the notoriously camera-shy Chris Marker to participate, though he appears only as a large cat cut-out, and his voice has been altered. (See below.)

Naturally there are passages concerning Varda’s late husband, Jacques Demy, including some candid on-set photos and footage of a very young Catherine Deneuve in costume. We see Varda strolling around an exhibition of her photographs of French movie stars and mourning their deaths, having at 80 outlived most of them. It’s a rambling film and yet somehow all hangs together, with self-deprecating humor, nostalgia, wacky juxtapositions, and moving moments as the director visits old haunts and friends. It was a real crowd-pleaser at the screening I attended, and deservedly so.

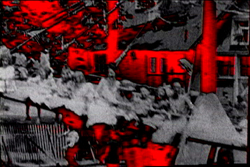

Ken Jacobs’ 2006 experimental feature, Razzle Dazzle: The Lost World was a must. Like Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son, Jacobs’ most famous film, this one takes an early Edison short and plays with it. Parts of the image get  enlarged, frozen, played in slow motion, and colored. Here Jacobs is working not on an optical printer but on a computer, using a single shot that is a view of a large rotating swing full of merrymakers. The result is a movement back and forth between abstract images, representational ones, and combinations where we must struggle to see glimpses of bodies, signs, and walls. I found this theme-and-variations portion of the film to be a bit overlong, with some computer graphics seemingly used simply because they were possible. But there are extraordinary moments. The scene of the swing takes place in daytime, but in the middle section suddenly blackness, superimposed rain, and the sound of thunder transform the scene into a frightening nighttime storm through which the giant swing is dimly visible,continuing to carry its occupants on swoops and glides through the dark. Another passage, illustrated here, manages to suggest a flickering nitrate fire–another frightening moment in a different way.

enlarged, frozen, played in slow motion, and colored. Here Jacobs is working not on an optical printer but on a computer, using a single shot that is a view of a large rotating swing full of merrymakers. The result is a movement back and forth between abstract images, representational ones, and combinations where we must struggle to see glimpses of bodies, signs, and walls. I found this theme-and-variations portion of the film to be a bit overlong, with some computer graphics seemingly used simply because they were possible. But there are extraordinary moments. The scene of the swing takes place in daytime, but in the middle section suddenly blackness, superimposed rain, and the sound of thunder transform the scene into a frightening nighttime storm through which the giant swing is dimly visible,continuing to carry its occupants on swoops and glides through the dark. Another passage, illustrated here, manages to suggest a flickering nitrate fire–another frightening moment in a different way.

The more interesting parts of the film for me were manipulations of stereoscope-card images. By quickly alternating the right and left photos on the cards, Jacobs creates some remarkable effects of apparent motion. (David discussed a similar effect last year in his comments on Capitalism: Child Labor.) Even with only two camera positions represented on the cards, at times an illusion of continuous movement is created, especially in a dramatic shot of ocean waves. There are portions of the image where the water seems to be flowing right to left in an unstopping stream. In other shots the camera seems to be gliding in an arc around the subjects. Jacobs has been doing a lot of experimentation with creating an appearance of 3D using only regular film equipment and still photos, and I for one would have liked to see more of the stereoscope cards and a little less of the play with the Edison shot. But that’s just a quibble. It’s a fascinating film, well worth seeing.

A late addition to the program was the foreign-language Oscar winner Departures. Steve Jarchow, one of the heads of Regent Entertainment, is a Madison native, and he appeared after the film for a lively question-and-answer session. Regent has other forthcoming films in the festival’s schedule, including Tokyo Sonata, which we blogged about from the Palm Springs International Film Festival.

David will probably have something to say about Departures, which he saw last week in a theater in Hong Kong. (He warned us all to bring our tissues, since it’s a good, old-fashioned Shochiku tear-jerker, albeit with many amusing touches.) Steve’s answers to questions put to him by Emeritus Professor Tino Balio and the audience were equally interesting. At a time when Hollywood studios are closing down their art-film niche divisions and foreign-language cinema seems an endangered species, Steve’s company is providing a healthy counter-force. A relatively small firm, it can thrive on titles that bring in a few million dollars–chicken feed by studio standards. Apart from foreign-language titles, Regent is catering to the gay and lesbian market, both for films and television programming. Steve also re-confirmed something that we know well: that Madison is a great town for art cinema, one of the best outside the big metropolitan areas.

From Steven’s Q&A I went off to see Goodbye Solo, Ramin Bahrani’s fifth film, and his third since coming to  wider public attention with Man Push Cart. Roger Ebert has been a champion of Bahrani’s work, and we’ll be seeing his previous feature, Chop Shop, at Ebertfest in a few weeks.

wider public attention with Man Push Cart. Roger Ebert has been a champion of Bahrani’s work, and we’ll be seeing his previous feature, Chop Shop, at Ebertfest in a few weeks.

Goodbye Solo is set in Bahrani’s hometown, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. It deals with a genial Senegalese cab-driver who decides to befriend a prickly white man who he suspects intends to commit suicide. Beautifully shot, the film is to Winston-Salem what Collateral is to Los Angeles, and the final scene in the autumnal Great Smoky Mountains is gorgeous. It’s a moving tale, and one which manages to be emotionally uplifting without falling into the trap of solving all its characters’ problems and becoming a feel-good film.

For those in the Madison area, the festival continues today and tomorrow.

13 days without movies? Not desirable, but possible

DB yet again:

Our road trip started back on the twelfth of September. We drove to Iowa City and ate at our grad school hangout, Hamburg Inn no. 2. (We even remember Hamburg Inn no. 1, long since vanished.) We pressed on through Nebraska to Denver, for a meeting of the Amarna Research Foundation, which helps support the Egyptian expedition on which Kristin works. She gave a presentation about the unique composite statuary of the Amarna era containing a new hypothesis that Barry Kemp, head of the expedition, found promising. After enjoying the hospitality of ARF president Bill Petty and his wife Nancy, we visited the Rocky Mountain National Park.

After a long day’s drive west, we overnighted in Elko, Nevada, where we learned that Barack Obama was scheduled to give a stump speech the next morning. We hung around and joined an enthusiastic group from all over northern Nevada to hear what he had to say.

After shaking hands with Barack, we moved on, rolling through Utah and into Oregon and Crater Lake National Park. Then up the coast highway to Seattle, where our nephew Sanjeev works for Microsoft and lives with his wife Maggie. We did some nifty touristic things in Seattle, and then with Sanjeev and Maggie we pressed on to Vancouver for its annual film festival.

During our westward passage through Grand Island (neither grand nor apparently an island), Craig, Elko, Klamath Falls, Coos Bay, Tillamook, and Tumwater, we saw many intriguing things. There was, for instance, the perfect rainbow in the bleakly beautiful northwestern Nevada desert.

In a little Colorado town, we found the toilet seat with fishing lures embalmed within.

In Snoqualmie Falls, Washington, while we downed burgers and malts at the Candy Factory & Café, four red-hot mamas came in and spontaneously started singing 1940s swing, Andrews-sisters style.

Yet such roadside attractions can’t compensate for our trip’s biggest drawback. We didn’t see a single complete film, not even on the free HBO available in motels. We used our late evenings to wolf down Subway subs and scan the Internets for news of lipstick, pigs, and less important things like the free fall of the U. S. economy.

Still, even without watching movies we did run across many traces of cinema. So don’t worry: This isn’t a travel entry, but rather an offhand effort to note the ways film keeps crossing our path, sometimes in surprising ways.

Movies everywhere

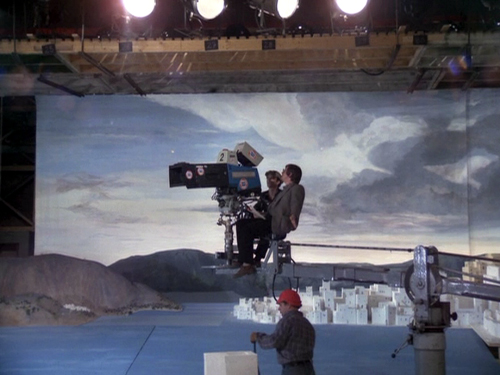

For instance, Bill Petty, an ardent Egyptomane, has created a home theatre unlike any other. The Pharaohs surely look with envy on this screening room.

In this venue, Bill showed us his home-made mashup of the Lon Chaney Phantom of the Opera with the Andrew Lloyd Webber score. That was the closest we got to movie viewing on the trip.

Also in Denver, we ate breakfast with Diane Waldman, old friend and film prof at University of Denver, and her husband Neil. We of course wound up in a restaurant with movie posters.

Passing through Vernal, Colorado, we spotted the most austere multiplex we’d ever seen.

Then there was Donna Kupp’s Books in Reedsport, Oregon. Donna has an excellent collection of classic paperbacks and magazines.

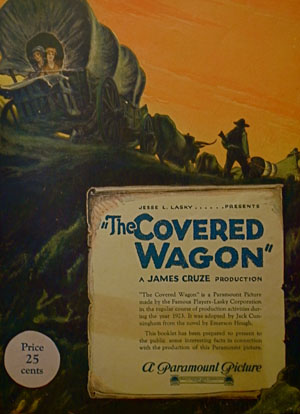

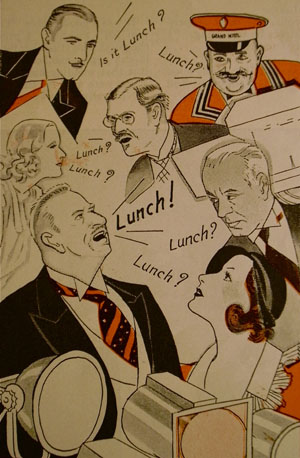

The high points of our purchases were an original souvenir program for The Covered Wagon and a pretty issue of Photoplay from 1932, which featured a gossipy story about the making of Grand Hotel.

The ladies’ big-band quartet wasn’t our reason for stopping in Snoqualmie, of course. You know why. The town was the shooting location of Twin Peaks. Hence this inevitable snapshot.

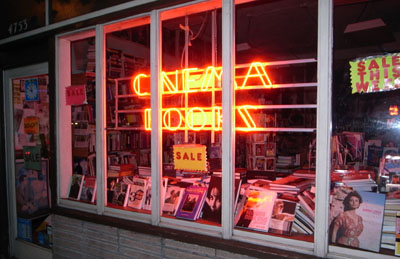

In Seattle, we discovered Stephanie Ogle’s outstanding Cinema Books on Roosevelt Way, N. E. This store is stuffed to the rafters with film items old and new–books, magazines, posters, and stills. Kristin even autographed some copies of her books.

We picked up several items there. Earlier that day, we visited Paul Allen’s lively Science-Fiction Museum. Sumptuous exhibits, but we weren’t allowed to photograph them. We did, however, get a chance to study a clone of the alien from The Day the Earth Stood Still.

As usual, a trip to an art museum provokes me to think of cinema. You don’t need much nudging to see this Rubens prototype for a Last Supper ceiling as a steep low-angle Welles or Hitchcock shot.

Less obviously, Abraham Janssens’ Origin of the Cornucopia (c. 1619) suggests a wide-angle lens at work. The three dryads stuffing the cornucopia are monumental, and monumentally skewed.

The stretched arm of the dryad on the left and the tipped knee of the one on the right seem to bulge right out of the picture plane. Check the hands, which thrust out of the picture and loom larger than the ladies’ heads. In particular, though you can’t see this in reproduction, the thumbnail of the figure on the right is a little blob of paint sitting on the painting’s surface, accentuating the sense that this hand is pointing right at us. Such images remind us that 2-D and 3-D are not so easy to keep distinct.

Our road trip confirms that movies are everywhere, waiting in the corners of our lives, ready to be activated with barely any prompting. Nonetheless, these are all merely teases, snacks making us eager for the banquet to come in Vancouver.

For Jim Emerson: Barbara Stanwyck, from Photoplay (Oct 1932).