Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

The ROW strikes again

The Time that Remains.

Kristin here:

Last year I remarked on how festivals like Vancouver are increasingly showing films from countries that have barely contributed to world cinema until recently. Not surprisingly, the trend continues. Yesterday I saw The Search (dir. Pema Tseden), the second feature to by made in Tibet by a team of Tibetans. (The first was also by Tseden.) It’s strongly reminiscent of Kiarostami’s best-known films, with a small film team traveling through the countryside trying to cast a movie based on a classic indigenous opera.

So far, however, most of the films I’ve seen have been from more established filmmaking regions.

Latin America

Latin American cinema continues to grow beyond Mexico, Brazil, and Peru, largely thanks to European co-productions and occasionally co-productions between countries within the region. For me, the first day of the festival concentrated on Latin America.

The first stop was Peru, with the surprise winner of this year’s Golden Bear at Berlin, Claudia Llosa’s The Milk of Sorrow. The plot concerns Fausta, a young woman whose mother, pregnant with her, was raped and tortured during era of the government’s war against the Shining Path insurgents (1980s-1990s).

Haunted by a fear of being raped herself, Fausta imitates a trick that a woman supposedly employed to fend off attackers. She places a potato in her vagina, hoping that the protruding shoots will repel a would-be rapist. Her terror of leaving home alone limits her freedom, though she manages to take a job as a maid to an eccentric female pianist. Her plight is ironically emphasized by the fact that her uncle is a wedding coordinator, and there are several scenes involving outgoing young women who are attuned to modern life and eager to marry.

The Milk of Sorrow is beautifully shot, with a minimal plot that proceeds at a languorous pace. It fits very much into the art cinema destined primarily for festival and big-city screenings.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Stylistically there’s nothing of great interest. As with so many films these days, it was shot in real locales, mostly the interior of one large house, and so consists mostly of medium shots and lots of panning. It’s essentially an actor’s film, though, and I could easily imagine it being remade in English as a vehicle for someone like Meryl Streep. It effortlessly balances drama and humor and is continually entertaining. It also features the only unequivocally upbeat ending among the films I’m discussing here, which no doubt says something either about the state of the world or about what filmmakers assume festival programmers look for.

Equally skillful but miles away in tone is the Mexican feature Backyard, by Carlos Carrera. Focusing on the astonishingly frequent rape, torture, and murder of women in Juàrez, the film follows a lone female detective in a police force which refuses to arrest or prosecute any of the perpetrators. (Above, she is confronted with hundreds of photos of the dead and missing.) The reasons behind both the numerous murders and official indifference turns out to be a combination of circumstances: at least one serial killer with the means to pay off the police, the executive of a Japanese factory that doesn’t want bad publicity, and random abusive husbands and young punks who take advantage of the situation to dump their victims in the desert with impunity.

The story is handled in taut classical fashion, intercutting between the detective’s investigations and the story of one young factory girl factory who eventually becomes a victim. This is the stuff of CSI and other crime shows, but all based on a horrific real-life situation that goes beyond what any mainstream drama would dare to show and that continues to this day right, as the title emphasizes, in America’s backyard.

One of the best films we’ve seen so far is Lucrecia Martel’s third feature, The Headless Woman. Although I had admired her visually gorgeous La ciénaga (2001), I found it a bit obvious in its use of the central swamp metaphor to characterize the upper-middle class. The Headless Woman, though, is the epitome of subtlety, with the plot being a puzzle with easily missed clues doled out sparingly. (The Variety review considerably mis-describes what happens, and I suspect others do as well.)

The opening is simple enough, with some boys playing in a dry concrete canal. Nearby, Veró, the woman of the title, helps her sister Josefina shoo a group of noisy kids into one car, while Veró takes off alone in the other. In a remarkable long take, she drives until the car lurches, causing her to bump her head on the windshield. Rather than cutting to what Veró hit, the camera stays with her as she sits, dazed. After a long pause she drives on, and a new framing allows us to briefly glimpse a large dead dog on the road in the distance. Soon the heroine stops and gets out of the car, walking out of focus as we stay in the car and the first heavy drops of a storm strike the windshield (below). One hint: even the exact moment when the rain starts becomes a clue to unraveling the action to come.

The rest of the film stays with Veró, who is present onscreen or off in every scene. We watch her uncertainty, caused by a concussion, but those around her barely notice, attributing her memory loss to tiredness or illness. Eventually Veró tells her husband that she thinks she has killed someone on the road. It would be unfair to reveal more, since experiencing the twists and implications of the plot should be up to the viewer.

Stylistically the film develops on Martel’s characteristic technique of shooting largely in tight shots filmed with highly selective focus. Often one must search for the one significant character. At other times, the camera lingers on Veró’s face, glancing vaguely around with a slight, defensive smile, pretending that nothing is wrong, as more significant actions by the other characters occur out of focus in the background. Often children swarm around, placing the thin thread of the central drama in the context of insignificant gestures of everyday life but making the clues all the harder to notice.

So well hidden is the plot that many viewers will mistakenly decide that it’s a film where nothing much happens. Those who engage with it will discover quite the opposite. But be warned, only a very alert viewer could figure out the plot correctly on a single viewing. I’ll admit I missed a crucial remark on the first pass.

(See also Jim Emerson’s take on The Headless Woman.)

The Middle East

Ahmad Abdalla behind the camera shooting Heliopolis.

David and I both saw Heliopolis, he because it’s a network narrative and I because it’s an interesting district of Cairo that I know only slightly. Egypt may in the past have been the main supplier of mainstream entertainment movies for the Middle East, but Heliopolis is very much an indie, made by first-time director Ahmad Abdalla with a tiny crew shooting on location for a mere two weeks.

In a rare move for this kind of narrative, the characters from the various plotlines barely intersect. Instead, Heliopolis itself is the focus. It’s a suburb near the airport that tourists drive through on their way to the central city but seldom visit. Once an enclave of foreigners, it is now is one of the main districts for middle- and upper-middle-class Egyptians. The beauty of the old buildings, some now shells and threatened with demolition, contrasts with an increasingly westernized youth culture on the streets. Similarly the characters, all with their own aspirations, suffer disappointments in the end, creating a bittersweet tone that becomes generalized to the district.

Lebanon, the Israeli film that won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival, tells a compressed story set during the first day of the Israeli-Lebanon war. It centers on a four-man team in a tank, all going into real combat for the first time. Director Samuel Maoz confines his camera to the interior of the tank for nearly all of the action, limiting our knowledge to the characters’ viewpoints (above). What we see of the war appears through the crosshairs of the mens’ scopes, though the director does not cue us to identify consistently with any of the individual team members.

The increasingly fetid interior of the tank becomes tangibly apparent as the men’s stubbly faces gleam with sweat and grime. At intervals Maoz cuts to grotesquely lyrical details of the tank’s surfaces, with oil oozing into dials or down the walls and filthy liquid on the floor rippling with the machine’s vibrations.

Many of the conventions of the men-at-war film are present, including the young man being killed just as his message assuring his parents of his safety is delivered and the novice gunner who fails to fire when he should but then kills an innocent passerby. But such conventions are renewed through the claustrophobia of the setting and the refusal to hold back in showing the confusion, terror, and savagery of war. Only the opening and closing shots, whether consciously or not an echo of Dovzhenko, offer a hint of peace.

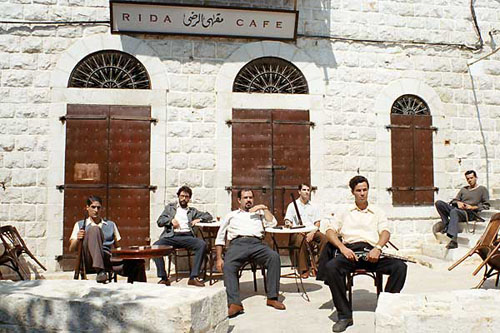

As an admirer of Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention, I anticipated most seeing his new film, The Time that Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee. It did not disappoint, though it is less ingratiating than the earlier film. Where Divine Intervention is largely based on subtle, ironic comedy played out primarily in Tati-esque long shots, The Time that Remains mixes long stretches of pure drama with the irony. I’ve read tepid reviews that reflect a lack of patience in figuring out what Suleiman was up to this time.

There are no Arrafat-face balloons flying over Jerusalem or fantasy ninja-revenge scenes here. Instead, apparently working with a larger budget, Suleiman ambitiously sets parts of his film in 1948 and other key years of the struggle between Palestinians and Israelis. His father appears as a constant participant in that struggle (seen in dark trousers in the frame at the top). The child Elia shows up partway through and becomes a silent witness to much of this. (As in Divine Intervention, the director plays himself but never speaks.) He acts more as a sympathizer than as an active participant in the conflict, going into exile as a young man and, as we know returning at intervals to make films that comment on the political situation. Hence the “present absentee” of the title.

The older scenes include staged skirmishes and chases, with genuine suspense, before the film settles into the modern era and the humorous, sometimes blackly humorous, life of Suleiman’s aging family and neighbors. As the earlier film dealt with his father’s final illness, the new one lingers over his mother’s.

Despite the drama, there are some characteristically hilarious moments. An unarmed Palestinian man takes out his garbage and paces during a cellphone conversation, ignoring all the while an enormous tank whose gun-turret swivels to cover his every move from a few feet away. Young Palestinians dance to loud music, seen through the glass walls of a discotheque. An Israeli jeep stops outside, vainly trying to make a curfew warning heard over the din, and the soldiers inside unwittingly start bobbing their heads slightly in time to the music.

We’re off to another day of film-viewing and will post again soon.

The Headless Woman.

Revenge of the ROW

Sun Spots.

DB here:

Watching Congress on C-SPAN makes you realize that the dead outnumber the living. Likewise, going to a film festival like Vancouver’s drives home to you how many movies there are out there. The world produces about 5000 features per year. No more than fifteen per cent of those come from the United States. That leaves about 4300 from what Hollywood execs apparently, and disparagingly, call ROW—the Rest Of the World. And hundreds of those 4300 are fighting for spots at the film festivals that have sprung up around the globe. Hence the rise of the programmer, today’s art-film gatekeeper and tastemaker.

To be a programmer you must be knowledgeable, traveled, and well-networked. You have to be steeped in contemporary film, you have to make your way to obscure places, and you have to know the right people—filmmakers, producers, sales agents, critics you can trust. Hence the power of a festival like Vancouver’s. It has superb programmers like Tony Rayns, Shelly Kraicer, Mark Peranson, Terry McEvoy, Stephanie Damgaard, Tom Charity, Sandy Gow, Tammy Bannister, and their colleagues.

You could mount a perfectly respectable event by cherry-picking other festivals’ lineups, but Vancouver mixes current international hits with genuine discoveries. Vancouver’s recognized specialties, like new Asian film, documentary, and Canadian features, nicely counterbalance their obligation to bring to the community the latest in top-drawer films of all sorts. A user-friendly festival in an exceptionally welcoming and picturesque city, Vancouver remains a magnet for us and hundreds of other cinephiles. This is my fifth visit, and Kristin and I commented online in 2006 (start here), 2007 (start here), and 2008 (start here).

This year’s Vancouver doesn’t lack big-name attractions. Keeping up their dedication to Manoel de Oliveira (a ripe 100-plus years old), the programmers have brought us Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, a sixty-minute package of pure pleasure. At first it seems a redo of Obscure Object of Desire. A man on a train recounts his frustrated efforts to marry a gorgeous young woman he glimpses at a window. But it turns out that this is an adaptation of a short story by Eça de Quieró, and things develop in very different directions than in Buñuel’s film. Oliveira’s characteristically chaste framings and sumptuous décor are enlivened by some errant formal devices that it would be a shame to divulge.

Okay, I’ll mention one because it kicks in from the start. On the train, Ricardo decides to tell his story to the woman sitting next to him. But while listening she usually looks straight into the camera. And every time she replies to his remarks, instead of turning to look at him, she delivers her lines directly to us. Ricardo looks at her, or sometimes just glances around as speakers do, but during her lines, the camera acts as a relay between her and him. You never quite get used to this strange displacement of dialogue, and it helps make Ricardo’s tale of archaic courtly love as subtly unnerving as the revelation that seals the couples’ fate. Whippersnapper directors a third Oliveira’s age would not dare so much.

Another much-awaited title was Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, and the hopes I expressed in the previous entry weren’t disappointed. A mentally handicapped boy is accused of murder, and his mother leaps into action to find the killer. As in Bong’s earlier Memories of Murder, a mystery intrigue ramifies into the lives of disparate characters, so that we’re skittering between physical clues (a golf club, inscribed golf balls, a strangely positioned corpse) and psychological ones, with bits of behavior serving to suggest multiple motives. Each character continues to surprise us—in particular, the sneering wastrel who takes advantage of the son. Driving the plot and passing through a spectrum of emotional changes, of course, is the title character. There’s no shortage of movies called Mother (though we’re told this one should properly be translated as Mother/Murder), but veteran actress Kim Hye-ja as the indefatigable guardian of her boy is as memorable as Pudovkin’s and Naruse’s protagonists.

Bong’s compact compositions are always at the service of his storytelling. I couldn’t see any fat on the scenes. His fluent pacing squeezes suspense and surprise out of each plot convolution. While the mother talks to her boy in jail, the lawyer stands at a distance from them, and, slightly out of focus, checks his watch. Instantly we know that he’s uninterested in the case. But Bong also knows how to linger. One of the most memorable slow dissolves I’ve seen in recent years counterposes mother and son, sleeping alongside each other off-center, against a horrific discovery tucked against the other edge of the anamorphic frame.

Mother has plot to spare; it could loan some to Sun Spots. What hath Hou wrought? I thought during the first few minutes of this exercise in Asian minimalism. This relentlessly dedramatized tale of a fugitive triad who meets a sulky girl in the countryside is determined to deny us any significant action, intense emotion, or old-fashioned enjoyment. Long shots, some very distant; thirty-one single-take scenes; impassive actors smoking, staring, turning from the camera, and generally hanging out: We have been here before. After twenty years of masterpieces by Hou, Kore-eda (Maboroshi), and Jia Zhangke (Platform), this style risks mannerism.

Eventually, though, I shifted gears and came to respect the movie. First, the landscapes are ravishing, worthy of a James Benning film. (8 ½ x 11, in which narrative gestures are swallowed up in immense spaces, wouldn’t be an irrelevant comparison.) Second, many compositions develop in unpredictable ways, and you’re given enough time to scan the frame for clues to what has happened before we join the scene. You’re obliged to notice handbags, cellphones, fishing poles, and cigarette butts strewn across the visual field. Third, director Yang Heng has exploited one powerful advantage of HD video: razor-sharp depth of field. This allows him to integrate distant hills and streams into the action. You see everything sharp and fresh, even actions hundreds of yards away. The final nine-minute shot forms a kind of climax of spatial acuity. A couple, trailed by a solitary figure, drift away from us into a grove of trees, and they remain visible as patches of white and black for an achingly long time before finally disappearing. Here “vanishing point” takes on its full meaning. Unthinkable on DVD, Sun Spots lives fully on the big screen, and one has to respect Yang’s single-minded commitment to making an anecdotal plot into something austere and sensuous.

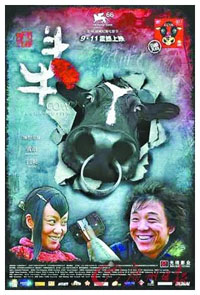

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Kristin and I have already seen plenty of other films we want to commend to you, but hitting four screenings a day hasn’t left us a lot of time to blog. Still, we’re determined to bring you more comments on this wondrous festival’s offerings.

Cow.

A welcome INFLUENZA

DB here:

Kristin and I are en route to the Vancouver International Film Festival, after a few days in Seattle visiting Sanjeev and Megan, nephew and niece-in-law. We were completely awestruck by the vast holdings of Scarecrow Video, where even the Warner Archives special-order DVDs can be rented. We also had a good long talk over JaK steaks with Jim Emerson, impresario of the superb website Scanners. Not to mention catching a screening of the lively Walt & El Grupo at the Seattle International Film Festival theatre. As a big fan of Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros, I was thrilled to learn the background story, as well as to watch gorgeous 16mm Kodachrome footage.

Last year’s trip to Vancouver put us on the road for thirteen days, encountering movie-related stuff (and Obama) in surprising places. This time we took the plane—faster but less relaxing. To get a better look at the landscape, we’ll be taking a train up to Vancouver.

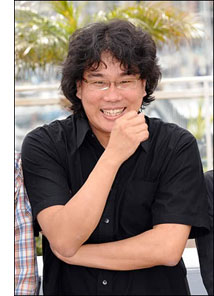

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

Even before meeting him, I had followed Bong’s career with keen interest. I think he’s one of the best Korean directors, though he probably doesn’t get as much attention as some others. Like the Japanese Kore-eda Hirokazu, Bong is the sort of quiet genre-hopper who’s hard to pin down. His first feature, Barking Dogs Never Bite, is a charming romantic comedy that also offers a portrait of neighborhood life. The mordant Memories of Murder (2003) quietly bends the conventions of the city-cop-in-a-village movie, mixing comedy into a serial-killer tale. Bong’s biggest commercial success came with The Host (2006), a monster movie in the grand tradition that manages to be at once scary, funny, and socially critical. Seeing it again this summer, I was struck by its compact elegance. Bong makes complex narrative and stylistic twists look easy.

Bong has also made some acute short films; he seems to understand that they require the snappy impact of a well-wrought short story. Probably his best-known short is the “Shaking Tokyo” segment of the omnibus movie Tokyo (2008). It focuses on a hikikomori, a young man who has withdrawn from social contact and lives wholly through the TV monitor and the computer screen. Bong’s hero tidily stacks empty pizza boxes along his walls like installation art. Only an encounter with a delivery woman makes him question his robotic seclusion. The ending, which lures our hero outside, provides a Twilight-Zoneish twist.

More single-minded, though, is a short I’ve just seen, the little-known Influenza (2004). There are several movies based on surveillance-camera footage; one of the most lyrical, Optical Vacuum, I reviewed here. Bong went instead for narrative. He staged a story in locales covered by surveillance cameras, and then retrieved the footage from the hours of material. Cut together, the shots follow Mr. Cho, a failed salesman who turns to petty theft and violent crime.

We discover Mr. Cho in men’s rooms, car parks, and ATM stations. The scenes, each shot in a single take, run through various spycam techniques: fixed high angle, black and white imagery, stuttering motion, mechanical scanning of the scene (sometimes leaving the main action behind). We see wide-angles, telephoto shots, barely legible long-shots, and split-screen imagery picking out opposite points of view.

Everything we see is staged, I think. Unrehearsed events seldom look this cogent and poised. Yet sometimes, especially during the climactic crowd scene, some of the action seems to have been left to luck.

Short but not sweet—mostly sour—Influenza shows what an ingenious filmmaker can do by setting himself a single, precise problem. Crossing the border between commercial fiction and avant-garde experimentation, the film deserves wider circulation.

As for Mother, Derek Elley’s Variety review promises the trademark Bong blend of gentle comedy and unsettling drama. And Vancouverites have an extra bit of luck: A program of shorts by Bong and his colleagues from the Korean Academy of Film Arts graces the festival this year. Bong’s next planned project, about the wretched survivors of a new Ice Age, shows him to be as unpredictable and unclassifiable as ever.

Thanks to Bong Joon-ho for his help in preparing this entry. The trailer for Walt & El Grupo is here. And there’s a poignant story of the founding and near-demise of Scarecrow Video here.

The Host.

Picks from the pile

Or rather, two piles. One stack of consumer durables that I brought home from seven weeks in what we Americans call Yurrp, and another stack of things that came while I was gone.

DVDs of course stand out. Apart from items scooped up in Bologna, here are a few highlights. Some are quite old, some very recent, but all were new to me.

The Magnificent Ambersons, on a Region 2 disc from Montparnasse, in cooperation with Cahiers du cinéma. The squarish box houses a slim booklet, a remastered copy, and bonus documents: interviews with Bill Krohn and Jean Douchet, and a 51-minute conversation between Welles and Bogdanovich. Plus the original trailer.

Engineer Prite’s Project, Kuleshov’s first film from 1918. It’s from Absolut Medien in collaboration with Hyperkino, which we wrote about last year. German subtitles only. Comes with a 54-minute documentary by Semyon Raitburt on the Kuleshov effect.

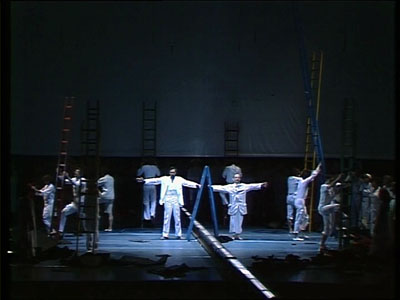

Another German release, but with English subs: Finally, the 1983 Stuttgart production of Philip Glass and Constance de Jong’s gorgeous Satyagraha. For once PoMo staging enhances the story. In the hammering opening of the second act, the mocking laughter of the South African whites comes from a vast row of beer swillers. The pre-HD imagery is a little soft, but my ancient Beta off-air copy can finally be laid to rest. From Arthaus Musik.

Absolut Medien also gives us The New Babylon, one of the greatest but least-known Soviet Montage films. The original Shostakovich score has been used, and the German reconstruction has English subtitles. Apparently a UK edition is on the way. The film is hard to cope with digitally: Lots of fog, smoke, and steam; diffuse photography; shots with significant action in out-of-focus planes. Still, it’s a big improvement on the bargain French edition in circulation. Tom Paulus, a real gentleman, surrendered the last copy in Bruges to me.

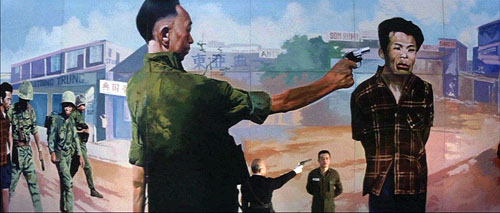

The venturesome French company Carlotta has launched an Oshima collection, though it doesn’t seem to appear on the Carlotta website! I found three must-have items at Fnac: A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs, Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, and best of all Three Resurrected Drunkards. The last is a bizarre masterpiece mixing a boy band up with the Vietnam war and Japanese discrimination against Koreans. About 40 minutes in, Oshima provides the most anxiety-provoking reel change in cinema. All Region 2.

Now for some books and journals:

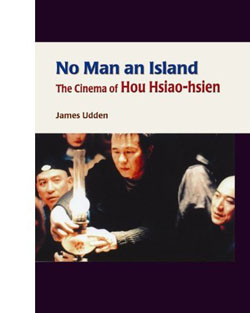

James Udden, one of my last dissertators before I retired, has written the first book-length study of Hou Hsiao-hsien in English. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien puts Hou firmly in the context of Taiwanese film history and culture. It offers some provocative suggestions, particularly in arguing that it’s misleading to consider Hou an essentially Chinese director. Jim, who lived in Taiwan and speaks Mandarin, spent many years watching Chinese films from all eras, and he balances this breadth with close study of each Hou film. From Hong Kong University Press.

James Udden, one of my last dissertators before I retired, has written the first book-length study of Hou Hsiao-hsien in English. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien puts Hou firmly in the context of Taiwanese film history and culture. It offers some provocative suggestions, particularly in arguing that it’s misleading to consider Hou an essentially Chinese director. Jim, who lived in Taiwan and speaks Mandarin, spent many years watching Chinese films from all eras, and he balances this breadth with close study of each Hou film. From Hong Kong University Press.

Eva Laass has just published a wide-ranging study of current narrative strategies in Broken Taboos, Subjective Truths: Forms and Functions of Unreliable Narration in Contemporary American Cinema. She examines Forrest Gump, Thank You for Smoking, Natural Born Killers, Fight Club, and other works in the light of several questions. What different forms of narrative unreliability can be distinguished? Why have unreliably narrated films become so popular in recent years? Which needs do they meet in American culture? Although available from Amazon.de, the book is in English.

I met Steven Jacobs, a brilliant young art historian with wide-ranging expertise, at the Bruges Zomerfilmcollege some years ago. This year he gave me a copy of his 2007 book, The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. Drawing on research in production documents, it’s a careful and imaginative analysis of the master’s use of interior spaces, including discussion of his “staircase complex.” Steven has even reconstructed floor plans for some movies. He is interviewed about the book, in Dutch, here.

For Paolo Gioli admirers, the forty-fifth Pesaro festival catalogue should be welcome. A retrospective of Gioli films is accompanied by essays, an extensive interview with Giacomo Daniele Fragapane, and a detailed, annotated filmography. Everything is bilingual Italian/ English. You can download the catalogue as a pdf here. I hope to post my contribution, with some extra frames, on this site in the next month or so.

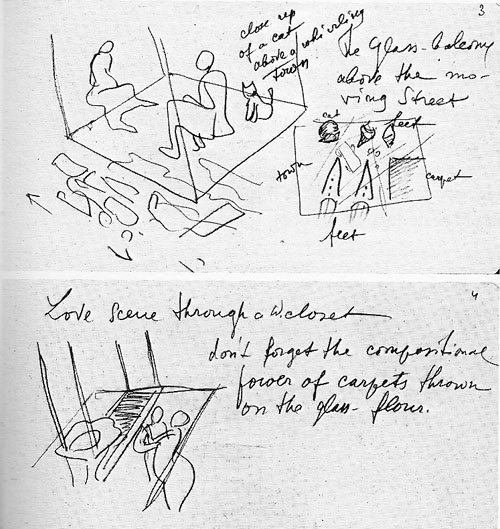

One of Eisenstein’s most ambitious projects was The Glass House (1927-1930). Inspired by skyscrapers, he envisaged a movie set in a high-rise apartment building of the future, with transparent walls and ceilings. He savored the idea of juxtaposing action in different layers (akin to the sequence in M. Giffard’s apartment in Tati’s Play Time). Some of the results can be seen surmounting this entry: a cat curled above a moving street, intertwined lovers seen through a bathroom floor. Another sketch shows a dying woman in the foreground and elevators carrying oblivious people past her.

The bold project is documented in a lovely French volume edited by Alexandre Laumonier and translated by Valérie Pozner and Michail Maiatsky. Glass House contains diary extracts, working notes, and sketches, all thoroughly annotated by François Albera. In a synoptic essay, Albera discusses the role of architecture in Eisenstein’s thinking.

Everyone seems to be talking about the roles of film festivals these days, and a current roundup of opinion can be found in the Cologne-based magazine Schnitt. The magazine is published in German, but for the festival symposium in issue 54, the editors provide English versions of essays by Marco Müller (Venice), Cameron Bailey (Toronto), and many other festmachers. Some radical ideas floating around here, including the suggestion by Lars Henrik Gass (Oberhausen) that subsidies for national film industries, and their festivals, may have to end. (His essay is available in English here.)

Everyone seems to be talking about the roles of film festivals these days, and a current roundup of opinion can be found in the Cologne-based magazine Schnitt. The magazine is published in German, but for the festival symposium in issue 54, the editors provide English versions of essays by Marco Müller (Venice), Cameron Bailey (Toronto), and many other festmachers. Some radical ideas floating around here, including the suggestion by Lars Henrik Gass (Oberhausen) that subsidies for national film industries, and their festivals, may have to end. (His essay is available in English here.)

In the wake of my homage to the Geneva Theatre/ Smith Opera House, Karen Colizzi Noonan kindly sent me some issues of Marquee, the journal of the Theatre Historical Society of America. Marquee is going strong after forty years, and it remains a lavish production, with big stills and in-depth research. The Society, which is currently updating the standard source book Great American Movie Theaters, holds an annual meeting that includes theatre tours. If you’re at all interested in American film history, you should visit the Society’s website.

There were other items on the two piles, but I have to go. My eyes and ears have some work to do. I’ll leave you with the most unexpected development, film-book-wise, I have encountered upon my return.

Three Resurrected Drunkards.