Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

Class of 1960

DB here:

By now most people accept the idea that 1939 was a kind of Golden Year of cinema. You know, Rules of the Game, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, that movie about the Civil War, etc. TCM has even made a movie about 1939. On this site Kristin and I have talked about earlier wonder years, like 1913 and 1917. So in planning this year’s Bruges week-long Zomerfilmcollege (aka Cinephile Summer Camp), Stef Franck and I discussed building my lectures around a single year. I proposed 1941, but he countered with 1960.

1960 was a logical choice in providing spread for the whole program. At Bruges we intertwine several threads of lectures and screenings, and this year we had silent films (The Cat and the Canary, The Wind), Hollywood’s cinema of emigration (Florey, Siodmak, Ophuls, etc.), and contemporary Korean film. All in 35mm, of course. So picking 1960 filled in another area.

As so often happens, a contingent choice came to seem a necessary one. By the time I opened my mouth to introduce The Bad Sleep Well, I had convinced myself that 1960 was another watershed year. Consider these releases:

Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti), La Dolce Vita (Fellini), L’Avventura (Antonioni), Le Testament d’Orphée (Cocteau), Plein Soleil (Clement), À bout de souffle (Godard), Les Bonnes femmes (Chabrol), La Verité (Clouzot), The Bridge (Wicki), Wild Strawberries (Bergman), The Devil’s Eye (Bergman), Lady with the Little Dog (Heifetz), The Letter that Wasn’t Sent (Kalatozov), The Steamroller and the Violin (Tarkovsky short), The Teutonic Knights (Alexander Ford), Innocent Sorcerors (Wajda), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Reisz), Tunes of Glory (Neame), Sergeant Rutledge (John Ford), Psycho (Hitchcock), Spartacus (Kubrick), Elmer Gantry (Brooks), 101 Dalmatians (Disney/ Reitherman), The Magnificent Seven (Sturges), Exodus (Preminger), Home from the Hill (Minnelli), Comanche Station (Boetticher), Verboten! (Fuller), The Bellboy (Lewis), The Young One (Buñuel), TheYoung Ones (Alcoriza), The Shadow of the Caudillo (Bracho), Devi (Ray), The Cloud-Capped Star (Ghatak), This Country Where the Ganges Flows (Karmakar), Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin), The Back Door (Li Han-hsiang), Enchanting Shadow (Li Han-hsiang), The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin), Desperado Outpost (Okamoto), Spring Dreams (Kinoshita), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Naruse), Daughter, Wives, and Mother (Naruse), Cruel Story of Youth (Oshima), The Sun’s Burial (Oshima), Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima), The Island (Shindo), Pigs and Battleships (Imamura), Sleep of the Beast (Suzuki), and Fighting Delinquents (Suzuki).

We didn’t show any of them.

Several factors constrained our choices, including the availability of good prints with Dutch subtitles, or at least English ones. We also didn’t want to run too many official classics. And we fudged a little for pedagogy’s sake. We had to include a Godard, but instead of À bout de souffle, we picked Le Petit soldat—made in 1960 but not released until 1963. The World of Apu was released in 1959 in India, though it made its world impact in the following year. Lola was finished in 1960 but released in early 1961. A dodge, but I wanted a Nouvelle Vague counterpoint to Godard, and it fit well with the Ophuls thread, and—well, it’s Demy. In any case, we wound up with a list of outstanding movies.

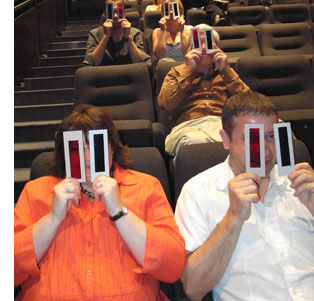

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

All in all, quite a week. My sessions ran from 9:00 AM to 12:30 or 1:00 PM, with the film embedded. After lunch, there were more talks and screenings, usually winding up at about 1:00 AM. Other speakers included Kevin Brownlow, Tom Paulus, Steven Jacobs, Muriel Andrin, Egbert Barten, and Christophe Verbiest (linking his talks on contemporary Korean film to the absolutely nuts 1960 Kim Ki-yong melodrama The Maid). The locals’ lectures were in Dutch, but these worthies are fluent in English, so sharing meals with them allowed me to catch up with their ideas.

Pegging a batch of movies to a single year can seem gimmicky, so I treated the films as exemplifying different trends, many of which started before 1960 and have continued since. I concentrated on trends within world film culture, though in several cases those were tied to still broader social and political developments. Above all, the 1960 frame allowed me to do the sort of comparative work I enjoy.

Generations

My first grouping was “Twilight of the Masters.” This allowed me to develop the idea that, remarkably, people who had started making films in the 1910s and 1920s were still active in the 1960s—and often making films that recalled their youthful efforts. Renoir revisited La Grande illusion in The Elusive Corporal, and Dreyer returned to his origins in tableau cinema through the staging of Gertrud.

In this connection, Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, his final movie, revisits his Mabuse cycle in the way his previous films for Artur Brauner revise the “sensation-films” he wrote for Joe May (especially The Indian Tomb). Drawing on some ideas in my online essay, “The Hook,” we studied Lang’s crisp transitions between scenes. From this angle, 1000 Eyes is a sort of encyclopedia of ways you can connect scenes (visual link, auditory link, association of ideas, etc.). The transitions whip up a breathless pace and steer past some plot holes, and sometimes they generate a level of mistrust, implying story possibilities that don’t turn out to be valid.

Testament’s motif of eyes and vision became expanded to television surveillance in 1000 Eyes. There might even be an oblique connection between the Hotel Luxor’s panopticon and the rise of television ownership in Europe at the period. Here, as ever, cinema doesn’t have good things to say about TV.

Twilight of another, not quite so old master: Late Autumn by Ozu. I reviewed some features of Ozu’s style and then analyzed the film as a multiple-character drama. Ozu and his collaborator Noda Kogo split up the plot in order to present different characters’ attitudes to the central situation: the question of a daughter’s marriage. The plot ingeniously withholds information about the attitude of Akiko, the mother, by deleting certain scenes that would clarify it. Here too, the old master recalls earlier films by having characters discuss their college flirtations, which invoke scenes from Days of Youth and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?

Both Billy Wilder and Akira Kurosawa furnished me with a second generational cohort. I know, probably nobody in his right mind would see common features between these two directors. But desperation can fuel audacity. Both emerged during the late 1930s, began directing in the 1940s, and enjoyed a string of great successes in the 1950s; but both fell on harder times in the 1960s. Both became accusatory living legends, haunting local industries that had kept them from working.

Leading up to The Apartment, I considered Wilder’s contribution to two trends. First, the industry had hit the doldrums. In Europe television and new leisure lifestyles were not yet the threat they would become, but in America, the industry needed to pull its audience away from the TV set and the barbecue. Wilder proved skilful in using Hollywood’s turn to sex as the basis for his cynical comedies. The Lubitsch touch, a worldly appreciation of the oblique approach to matters of sex, was replaced by something harsher. In Wilder’s world, there are mostly sharks and shnooks, those who take and those who are taken.

Second, I situated Wilder as a leading figure in the emergence of the writer-turned-director in the 1940s (Sturges, Huston, Brooks, Fuller, Mankiewicz, etc.). This encouraged me to probe his dramaturgy, and so we analyzed the taut structure of The Apartment’s plot. It has rightly been recognized as a model screenplay, making us sympathize with a careerist covering up his bosses’ infidelities, all the while whetting our interest by shifting the range of knowledge away from the protagonist at key moments. It also displays a nice interweaving of motifs that function both dramatically and metaphorically (especially Miss Kubelik’s hand mirror). Of course at the end I had to run a clip showing the influence of The Apartment on the opening of Jerry Maguire.

By the mid-1960s, however, Wilder was pushing his luck, especially with Kiss Me Stupid. In The Apartment he wanted to make “a movie about fucking,” and he predicted that some day people would do the deed onscreen. But having glimpsed the promised land of the 1970s, he was unable to enter. Despite some worthy efforts, notably The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, he haunted Hollywood as a major director who had outlived his moment.

Human, all too human

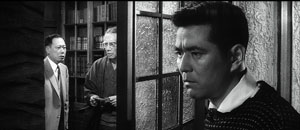

Kurosawa’s international fame came largely through the growth of the film festival as a prime institution of international movie culture. This situation let me sketch in the importance of festivals in bringing directors like him to world recognition. (By the way, Richard Porton has just brought out an informative collection of thoughts on film festivals.) With The Bad Sleep Well, I was able to talk a bit about something that is often forgotten—Kurosawa’s efforts in social, even political cinema. From Sugata Sanshiro, a tribute to Japanese martial arts, and The Most Beautiful, the loveliest movie you’ll ever see about girls making lenses for gunsights, up through Occupation projects like No Regrets for Our Youth and Scandal, Kurosawa engaged with political subject matter. Ikiru and I Live in Fear made this side of his work even more salient in the 1950s.

The Bad Sleep Well’s attack on corporate corruption sits well with this tendency. It considers the “iron triangle” of Japanese politics, the collusion of bureaucrats, politicians, and private industry—particularly the building industry, whose livelihood depends on bids for government projects. Still, it’s hard to believe that while Kurosawa made the film, and while Ozu made the serene Late Autumn, students were fighting police in the streets over the US-Japan security treaty. That turmoil surfaced in Oshima Nagisa’s demanding and formally daring Night and Fog in Japan.

The movie is shot with Kurosawa’s usual muscularity, including virtuoso compositions in what he called, following Toland, “pan-focus.”

The film’s twists also seemed to me worth examining. The protagonist is a minor presence in the first scenes, and his reticence in the beginning is mirrored in the finale, when he simply vanishes and his pal has to tell us what happened to him. Such a daring structure, reminiscent of the abrupt midway break in Ikiru, gives the film an almost Brechtian discomfiture, as well as highlighting the secondary characters’ rather perverse reaction to the hero’s fate.

Kurosawa was widely called a “humanist” director, and this concept sheds light on what we might call the “international film ideology” pervading festivals in the 1950s. In various areas of social and philosophical thought, a notion of humanism emerged out of disillusionment with the “age of ideology” that had engulfed the world in war. Several thinkers declared that the age of religious dogma and social collectivism, either Nazi or Communist, was over. Now what mattered were the features that drew people of all societies together, and the prospect of enlightened social action based on those commonalities—tolerance, respect, and a belief that people ultimately took individual responsibility for their communities. Catholics, Communists, and people of all stripes scrambled to call themselves humanists. As Dwight Macdonald, former Trotskyite, put it, “The root is man.”

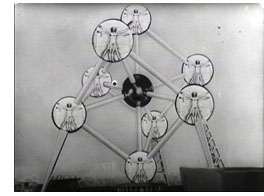

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

Film festivals embraced this universalism, pointing to the great films of Italy’s Neorealist trend as proof of cross-cultural communication. Although these films often scored specifically Italian political points, they could also be seen as human documents speaking to audiences anywhere. Who could not empathize with Ricci and his son in Bicycle Thieves (named at the 1958 Expo as the third-greatest film ever made)?

The turn to humanism helps answer a puzzling question: Why Satyajit Ray? Virtually no Europeans had ever seen a film from India. What enabled a director from this country to achieve worldwide renown? And why not other Indian directors of his era, such as Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak? All of these had to wait many years for discovery by European tastemakers.

For one thing, Ray was highly westernized himself. He was a child of the Bengali Renaissance, a virtuoso in many fields (he composed music, drew with facility, wrote detective stories and children’s books), and an admirer of European cinema. A stint assisting Jean Renoir exposed him to one of the greatest of Western filmmakers. A viewing of The Bicycle Thieves determined him to make films. He was skeptical of imitating Hollywood, which had been a prime inspiration for Hindu cinema. He criticized Bollywood’s reliance on schematic romance and musical numbers. If any Indian director was to make the move to the festival circuit, it would be him. (You can argue that other non-European filmmakers who made it into the fold were the most “western”—Kurosawa, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, etc.).

Just as important, Ray’s stories suited the humanist program. Whereas Ghatak and Sen made politically charged films, Ray concentrated on the individual. In The World of Apu, social conditions are shown, but as a background to the development of personality and psychological tensions. At the film’s start, students are holding a street march demanding political rights, but they are offscreen, a backdrop to Apu’s meeting with his old professor as he gets his letter of recommendation. What follows is a drama of artistic failure, blossoming love, and a young man’s confused growth to maturity and responsibility.

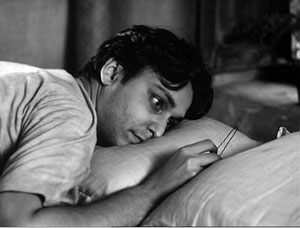

It’s a simple story, rendered lyrical through constantly developing imagery: Apu stretched out prone, the famous grimy window curtain, and a cluster of visual motifs I hadn’t noticed on previous viewing. Ray’s concise direction links the torn curtain in Apu’s room to the famous (Langian?) transition from a movie screen to a carriage window, the cluster unified by associating Apurna with male children. Thanks to Andrew Robinson’s book on Ray, we know that in the carriage scene she is already thinking of the son she will bear.

It’s easy to romanticize this handsome, happy-go-lucky hero. I think the College participants thought I was a little hard on Apu, since I treated him as far from the “conscientious and diligent” young man his professor wrote of. Surely his idealistic-novelist persona is sympathetic. But if he is to grow as the film suggests, he must have failings, and Ray shows them to us—dreamy indolence, self-centeredness, even poutiness. The film is a character study, a sort of Bildungsroman tracing how Apu learns his place in his world. Our discussion after this film was particularly rich, with one participant suggesting that in accepting his son he isn’t abandoning his art entirely, but giving it human significance: He promises to tell Kajal stories.

Ray came to directing in middle age, a somewhat rare option. So too did Gillo Pontecorvo, but the latter made many fewer films. Although Kapò, isn’t as strong a movie as our other entries, it did allow us to talk a bit about coproduction, about European cinema’s relation to World War II, and about what came to be known as the morality of technique.

European coproductions are another fundamental part of the 1960 landscape, and they illustrate how economic considerations penetrate artistic choices. (Why are American and Italian actors in the “German” film 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse? Why do we find Anouk Aimée in 8 ½ and Jeanne Moreau in La Notte? Follow the money.) For the Italian production Kapò, the primary roles are taken by an American (Susan Strasberg, playing the heroine Edith) and two French actors—the concentration camp translator played by Emmanuelle Riva and the heroic Soviet soldier played by Laurent Terzieff. The film was shot in Yugoslavia.

The story centers on a young Jewish girl who, in order to survive Nazi internment, passes herself off as a Gentile and becomes a camp commandant, whipping other prisoners into line. Other Italian films of the period, notably Rossellini’s Generale Della Rovere, were dealing with issues of conscience during the war, but Kapò was apparently the first fictional feature in Western Europe to confront the Holocaust since Alessandrini’s Wandering Jew of 1947. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossod and stood trial the following year, and after Kapò came a few other films addressing the camps, notably Wajda’s Samson (1961) and Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965). So the film had a strong contemporary resonance; after its US release, it would be nominated for an Oscar.

One reason Stef and I picked Kapò was the controversy around Jacques Rivette’s accusation in Cahiers du cinéma that for a particular tracking shot Pontecorvo deserved “the most profound contempt.” The film, as Rivette indicates, is dominated by an already compromised conception of realism: grimed faces, make-up that hollows cheeks, somewhat ragged clothes, moderately shabby bunks. The shot shows the body of Theresa hurled against the electrified barbed wire, with the camera coasting slowly toward it. Her silhouette is almost classically composed, with the hands artfully pivoted and standing out against the sky. For Rivette this pictorial conceit is virtually obscene.

It seems to me that Rivette’s essay sought in part to reply to those who thought that Cahiers’ policy amounted to pure formalism. In calling for an ethics of technique, Rivette argues that artistic choices which might seem to be in the service of correct politics can betray a deeper immorality: using a historical cataclysm as an occasion for a safe realism and self-congratulatory flourishes. Similar complaints could be lodged against Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg and Stone’s World Trade Center. And because for the Cahiers team artistic cinema was an expression of a creator’s vision, the morally maladroit traveling shot brands the director as a man of bad faith.

Rivette isn’t saying that film artists shouldn’t try to represent historical trauma. He simply argues that other paths could be taken. For instance, Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour acknowledge that some events cannot be encompassed by normal understanding, and the form of each film enacts an effort to understand, not a fixed conclusion. What we see in Night and Fog is “a lucid consciousness, somewhat impersonal, that is unable to accept or understand or admit this phenomenon.” For Rivette, Pontecorvo seems convinced that romantic love and self-sacrifice can overcome Nazism, albeit with some help from the Red Army. He tries to explain, even prettify, an event that cannot be understood within the usual humanistic categories.

New Wave, still new

Lola.

Godard’s Le Petit soldat is far more preoccupied with uncertainties, even confusions, than Kapò is. 1960 saw an extraordinary number of former colonies, especially in Africa, gain independence, and during that year the Algerian war of resistance was spreading to Europe. Godard’s central character Bruno is working with the OAS vigilantes dedicated to killing Algerian terrorists, but when he meets the lovely Veronica Dreyer he decides to leave politics behind and flee with her to Brazil. Perhaps “decides” is the wrong word, since his actions are impulsive: he abruptly shies away from committing a political assassination, and he abruptly abandons his colleagues. But he’s captured by FLN terrorists and, in the film’s most famous sequences, tortured. At the end, he commits the assassination, not knowing that Veronica, herself in league with the Algerians, has been captured by his pals and killed. But his final voice-over is almost a shrug, and his act of murder takes on the flavor of an existentialist acte gratuite.

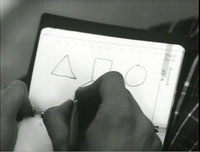

Le Petit soldat doesn’t offer heroic figures, as Kapò does in Theresa and the Soviet soldier. Nor does it allow us to sympathize much with the egotistical, capricious Bruno. The texture is more disjunctive, littered with the usual digressions and citations. Since the film was shot in Geneva, there’s a persistent motif of Swissness, with citations of Paul Klee. A sneaky one I never noticed before: the seduction game Bruno plays is modeled on the three fundamental shapes in the Bauhaus basic course, which Klee taught.

Having experimented with discontinuous imagery in À bout de souffle, Godard in his second feature turns his attention to the soundtrack, creating one of the most minimalist ones I know. If Bresson whittles down his soundtrack to a spare but recognizable realism, Le Petit soldat goes a step further, scrubbing out nearly every noise until we’re almost watching a silent film. Traffic scenes lack traffic noises, with only a car horn or a bit of dialogue breaking in. One passage on a train could almost be a sound loop.

The strategy of suppressed sound is carried to a paroxysm in the torture scenes, with the clink of handcuffs and the soft tapping of typewriter keys highlighted and bits of music played spasmodically…but no sounds of pain. Only during the rushed and almost throwaway climax, is something like a plausible city ambience heard. In a dichotomy that will be familiar throughout Godard’s work, there’s a split between image (Bruno is a photographer, and in the early part of the film he takes snapshots of Veronica in her apartment) and sound (the political factions rely on telephones and tape recorders, and the OAS thugs trick their way into Veronica’s apartment through sound recording).

In all, Le Petit soldat isn’t exactly fun but it’s exhilarating in its bursts and unexpected frictions. Next time somebody tells me that Godard’s technical innovations have all become commonplace, I’ll point to this film of 1960, which would be daring and demanding if released tomorrow.

Fun, albeit grave, is what Lola is all about. It takes formal artifice far beyond realism, creating a sort of non-musical musical. (It has one number, and even that is a sketchy rehearsal.) As geometrical as a minuet, its plot plays out in a hall of mirrors, where characters share names, pasts, and sentiments. The sailor Frankie and the wandering Michel, both in love with Lola, are blonde giants. Lola is actually named Cécile, and the little girl of the same name seems in some ways an early version of her, while Cécile’s mother has a dash of Lola in her past.

Roland starts out as the protagonist, but as he warms and cools and warms to Lola, the story momentum shifts to others. There’s Lola of course, and young Cécile who strikes up a friendship with Frankie, and Cécile’s mother who yearns a bit for Roland, and Michel, who left Nantes years ago and has lived in another movie, specifically, Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1952). Here the structure of the plot unfolds the network of relationships among people, linked mostly by casual encounters across a few days. The last section accordingly consists of a series of farewells, as if the story can end only by breaking ties of affection.

In surveying these films, I was struck by how much most of them owed to the growth of postwar institutions of film culture, and how strong those institutions remain. Coproductions and subsidies were feeding a massive buildup of European cinema. Contrary to what you might expect, as attendance cratered from the late 1950s onward, the number of European films produced went up. The EU countries still overproduce, releasing nearly 1200 theatrical features in 2008.

Film festivals were promoting not only universal humanism; they were also packaging films under rubrics of authorship or the New XXX Cinema and the Young ZZZ Cinema. 1940s Neorealism, aka “New Realism in Italian Cinema,” seems to have been, once more, the prototype. Festivals must make discoveries and emphasize novelties. At the same period film schools taught professional standards, and film archives showed classics and gave postwar filmmakers a more secure sense of the medium’s history. Lang, Ozu, and Wilder weren’t dependent on such institutions, but younger filmmakers were. And still are.

1960 is an arbitrary data point, but it stands out as an extraordinary year for quality. In addition, picking it as a benchmark allowed me to think about some important trends of the period. What probably didn’t show through my lumbering PowerPoints, with their charts, diagrams, and frame enlargements, was how much I learned from my Bruges stay. One of the deep satisfactions of teaching is remembering, no matter how confidently you declare your claims, how much more there is to know. Of things cinematic there is no end.

We also asked participants to read Serge Daney’s essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò.” Daney’s elaborate exercise in autobiography, irony, and moral reflection could not be plumbed in the time at my disposal, there or here. But it did help me understand Rivette’s argument. In preparing my lectures, I also owed a debt to some excellent books, notably Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity; Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye; Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism; and Richard Brody, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As ever, the invaluable documentation provided by the print editions of Screen Digest over the years enabled me to compile my tables of attendance, releases, and the like.

Late Autumn.

P.S. 3 Aug: Stef has posted snapshots from our Zomerfilmcollege here.

P.P.S. 3 Aug: This helpful correction from Roland-François Lack on Le Petit Soldat:

One small point: the organisation Bruno works for cannot be the O.A.S., which wasn’t active until the end of 1960.

He is working, rather, for ‘La main rouge’, a government sponsored counter-terrorist agency run by a Colonel Mercier (hence the name of Bruno’s associate).

Nice! Thanks.

Back in Bologna

The newly restored version of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly on the Piazza Maggiore.

Kristin here-

This year, the main complaint about Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival held by the Cineteca Bologna, is that there’s too much to see. With three venues playing films against each other, plus the 10 pm screenings each evening in the Piazza Maggiore, there’s no way to see everything. Some people complain that the conflicts are becoming worse-but I remember these same complaints about the over-abundance of films coming in previous years as well. Yes, it’s frustrating at times, but being offered more films than one can watch is a problem a lot of people would love to have. Basically one either chooses a couple of threads to follow through or just goes to whatever appeals in any given time slot.

According to the 2009 festival’s newsletter, there were 810 attendees, including 557 from outside Italy.

This year there have been several main focuses: a retrospective of Frank Capra’s silent and early sound films; a portion of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse’s program of Jewish-themed Russian and Soviet cinema from the 1910s to the late 1940s; a selection of color films from the early years of the twentieth century to the 1960s; a survey of the work of Vittorio Cottafavi; the annual “100 years” program, this time from 1909; the sea films of Jean Epstein; the silent Maciste films; and many other items.

Even between the two of us, we could not take in nearly all of the riches on offer, so here’s some of what I managed to see, with David’s report to follow.

An annual hundredth birthday

Each year the festival has a thread of programs of films from one hundred years earlier. This tradition started in 2003, when Tom Gunning was asked to put together groups of films from 1903. Thereafter Mariann Lewinsky took over as programmer for these threads. In recent years, her choices have been supplemented by small groups of films chosen by individual national film archives. This year Tom programmed the 1909 Griffiths and a group of other U. S. titles.

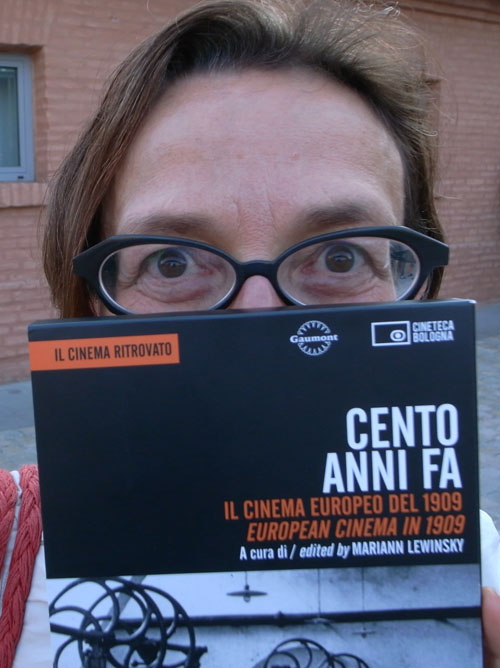

Maybe it’s just my impression, but the hundred-year packages seem to gain in prominence and popularity each year. Presumably in response to such popularity, the festival has just released a DVD with a selection of 22 shorts from this year’s 1909 program: Cento anni fa: Il cinema Europeo del 1909/European cinema in 1909 (running two hours and twenty minutes and presented below by Mariann). It contains only about a fifth of the roughly 100 films screened, but many of the others are available in online archives. DVDs of previous years’ programs are in the works, with 1907 soon to come. The DVD and other publications of the festival are available here.

I managed to see most of the 1909 programs but obviously can mention only a sampling. Undoubtedly the highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

French director Alfred Machin contributed two excellent dramatic films, both involving windmills: Le Moulin maudit (also on the DVD) and, in the program of early color films, L’Ame des moulins. Comedy stars were represented by two Cretinetti films and a strange Max Linder film in which he becomes Amoreux de la femme à barbe (“Infatuated with the Bearded Lady”).

There were a great many documentaries giving glimpses into the world of 1909. Airplanes were much in  evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

Mariann watched a great number of 1909 films in order to make her selection. Her experience convinced her of what many of us feel, that this was a turning point for the development of film art, though perhaps not as dramatic a one as 1913. Apart from L’Assommoir, Griffith’s The Country Doctor could be pointed to as evidence that the year saw films of a greater complexity and beauty than had previously been released. Griffith may no longer be quite the lone giant of the pre-1920 era that film historians have portrayed. Still, there are touches in The Country Doctor that no other director could have conceived, such as the early shot of the central family strolling through a field of tall grass that hides everything except the doctor’s top hat floating above the stalks.

Reaching 1909 raises the question as to how long these 100-year anniversary programs can continue and what form they should take. With fiction films getting longer in years to come, particularly in Europe, there emerges a problem of including enough of them to give a sense of a single year without having the programs expand even more. Perhaps non-fiction films will figure as an increasing proportion of this thread-with more Lewinsky dogs inadvertently captured for posterity.

A garland of color films

Two programs of early color films demonstrated the various processes: hand-coloring with stencils, tinting, toning, and attempts at photographic color. The only really successful of the latter were two 1912 shorts using the Gaumont system, which provided images in sharp, reasonably true color.

I caught only a few of the features in the color thread. Victor Schertzinger’s Redskin (1929), in two-strip Technicolor, was a beautiful print. Despite its implausibly happy ending, this story was a sophisticated look not only at racial tensions between whites and Indians but also at equally divisive tensions among Indian tribes. Like the other occasional films of the early decades that show the action from the Indians’ standpoint (Griffith’s The Red Man’s View figured in the 1909 program) are remarkably sympathetic to their culture. The color portrays not only the beautiful desert landscapes of the American Southwest but also Navaho blankets and Pueblo sand paintings.

Toward the end of the week, when people asked me what my favorites had been so far, I forgot to mention Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, which had played way back on the opening Saturday. It has a reputation as a bizarre film, and I wasn’t expecting much beyond some glowing color images of two beautiful stars, Ava Gardner and James Mason. But I was pleasantly surprised by its well-handled fantasy tale of the Flying Dutchman visiting a contemporary Spanish seaside resort and finding his true love. In particular a lengthy flashback to the Dutchman’s original crime has a degree of stylization and intensity that allow it to avoid seeming absurd. The tale has an other-worldly quality that recalls some of Powell and Pressburger’s films-enhanced by the presence of cinematographer Jack Cardiff handling the Technicolor.

Unfortunately Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954) failed to similarly avoid a sense of the absurd in its overheated Tennessee William pastiche set on an isolated farm in the West. Lumbering dialogue lays out explicitly all the tensions among the members of the central family, exacerbated by the depredations of an elusive puma and a visit by the younger brother’s potential fiancée. The reason for its presence in the festival, though, was its color scheme. Wellman set out to make a “black and white film in color,” as the program describes it. Both the snowy landscapes and the interiors are dominated by white, black, and flesh tones, with the sole exception-the Robert Mitchum character’s bright red coat-disappearing from the action partway through.

Not only silents need restoring

Martin Scorsese’s influence hovers over the festival and the Cineteca Bologna. One of the two screening rooms in the Cineteca’s building is the Scorsese (the other being the Mastroianni). In recent years, films from the institution that Scorsese founded, the World Film Foundation, have been screened here. The WFF is dedicated to restoring and preserving films from countries whose archives might lack the resources to handle such major projects. This year’s presentations were Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (The Wave, 1936), Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia (known in English as The Night of Counting the Years, 1969), and Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The foundation also aided in the editing of Ingmar Bergman’s home movies into Images from the Playground (Stig Borkman, 2009).

I had seen The Night of Counting the Years in one of the faded 16mm copies that have long been the only form in which this Egyptian classic was available. The new copy is a vast improvement, finally revealing why this is considered perhaps the great Egyptian film. It is based around a true story from 1881, when a powerful tribe on the west bank at Luxor discovered a cave containing a huge cache of royal mummies and funerary goods that had been hidden away by ancient priests to preserve them after the extensive robbing of their original tombs. The tribe started selling items gradually on the illicit antiquities market, but one of its members revealed the location of the cache to the authorities, allowing them to salvage most of the mummies and their grave goods. The film was beautifully shot on location in the desert and temples of the west bank and provides a meditation on why the young man might have acted against the apparent best interests of himself and his family.

A 1991 Edward Yang film might not seem an obvious candidate for restoration, yet the complete version of A Brighter Summer Day was barely rescued from oblivion. The original negative does not exist, and the print materials on the shorter version were discovered to be moldy. Rescuing these and combining footage from both versions has resulted in a pristine new print of Yang’s greatest achievement. An in-depth look at Taiwanese society a decade after Chiang Kai-chek took over the island, it follows a middle-class boy drawn gradually into gang violence. The new version, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, looked great on the big screen in the Arlecchino.

This and that

A brief tribute to Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast included Laughter, the director’s first sound film. A romantic comedy, it stars Frederick March as a witty young composer aspiring to marry a wealthy society woman against her father’s wishes. The film has touches of Holiday and Design for Living, both films yet to be made. Laughter confirms d’Abbadie Arrast’s reputation as a good but lesser filmmaker in the Lubitsch mold.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

Demonstrating that history repeats itself, Belgian film scholar Eric De Kuyper programmed a selection of titles dealing with financial speculation and crisis. These included perhaps the best of several items from Louis Feuillade shown during the week, Le Trust ou les batailles de l’argent (1911). It stars René Navarre, who would soon play Fantômas, as an unscrupulous detective, and the action is more in the thriller mode than a serious depiction of French finances. Also included was a 1916 German feature, Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange”), with a fine performance by Asta Nielsen as a woman more successful in finance than in love.

More to come from David, on Capra, DVD awards, and personalities glimpsed by a roving camera.

For our previous Cinema Ritrovato entries, see here for 2008 and here, here, and here for 2007. For a thorough discussion of dogs in early film, with comments by Mariann Lewinsky, see Luke McKernan‘s authoritative entry here. On the occasion of Edward Yang’s death in 2007, David offered an homage to him and A Brighter Summer Day here.

The postman has rung more than twice

Optical Vacuum.

DB here:

While I try to whip up seven lectures for the Bruges Summer Film College and a couple more for the University of Copenhagen and our June Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image confab, I offer some quick notes on notable DVDs and books lugged to our door by our mailman.

When machines film better than they know

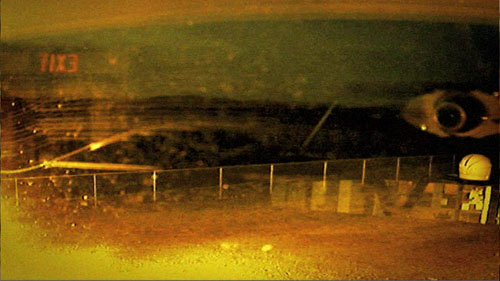

Snow blankets a terrace and the furniture on it. A bottle jerks back and forth on a pavement. Christmas lights blink on and off. Everything looks desolate. What people we see scuttle across washed-out landscapes, play mahjongg in stammering gestures, and toil in computer labs under glaring fluorescent lights. What planet are we on?

These images are available to any of us. For two years Dariusz Kowalski trawled through sites like www.opentopia.com for surveillance-camera footage. He chose only material from hidden cameras. He added nothing except some slow motion (“otherwise it would be too fast”) and a voice-over commentary from artist Stephen Mathewson reading passages from a year’s diary. The result was a fifty-five minute assemblage film called Optical Vacuum (2008), which I saw and admired in Hong Kong back in April.

Sometimes the diary account intersects with what we see: Mathewson talks of washing his laundry/ shots of a Laundromat. More often, the voice drifts off on its own. Optical Vacuum isn’t an effort to make a film essay or to create a complex audiovisual dynamic. Mathewson’s diary provides an intimacy that the footage lacks, but I think the film would stand up strongly without it.

As a flow of impersonal views, usually from a distant perch, the footage creates a bleak beauty.

Occasionally a human operator has commanded the camera to focus on something, usually a woman.

But most often the camera is just mindlessly recording.

In the process, the surveillance camera reinvents avant-garde film—not just the barely inflected fields of Structural cinema, but also the time compression and melting glimpses, the reflections and superimpositions, the transient ghosts and brutal geometry we find in silent experimental work by Richter, Vertov, and others. These stupid cameras can’t help turning reality into something else. They don’t know any better.

Optical Vacuum, along with other pieces by Kowalski, can be found on a PAL uncoded DVD from the extraordinary Austrian collective sixpack. The handsomely mounted Index release is available here, and elsewhere on the Net.

Dragons and tigers in the Udine sun

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Alas, I’ve never been. In its earliest years it overlapped with the Hong Kong film festival; more recently, my commitments elsewhere, such as Ebertfest, have kept me away. But I have followed this celebration of Asian cinema at a distance through its remarkable publications.

The Udine event concentrates on popular cinema, mostly recent releases that are unlikely to come to US theatres or video stores. You can see films from Japan, Korea, and China but also from Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. This year’s highlights include regional hits like Cape no. 7, Beast Stalker, Departures, and Ip Man as well as obscure and delirious items like Love Exposure and The Forbidden Legend: Sex and Chopsticks. Many screenings are European premieres.

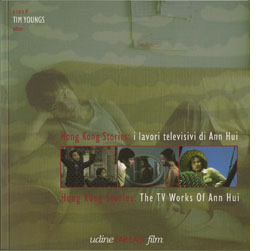

The programmers also mount adventurous retrospectives of rare items. One year it was a survey of the work of Patrick Tam, still too little known among Asian aficionados. This year the retrospective was devoted to Ann Hui’s TV films, which are among her best work. These films, shot in 16mm and broadcast in the 1970s, were strong meat for a culture unused to social criticism in its popular media. Hui’s dramas showed police corruption, the sex trade, abandoned children, and drug addiction. The episodes were researched and scripted under great time pressure, and Hui was allotted two weeks for shooting and post-production. “We were experts at shooting in the streets on the sly.” The stories’ concern for ordinary people and their problems has resurfaced again in The Way We Are (2008) and Night and Fog (2009).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

As if this weren’t enough, the Udine event publishes a mammoth catalogue called Nickelodeon. Each year it’s a treasure chest of enthusiastically presented information. This time around, surveys of 2008 developments in all the major countries are accompanied by Roger Garcia‘s special section on the history of Thai action cinema. A vast section of reviews of the films to be shown rounds out this gift to the Asian cinephile. (A little of this material is available at the Udine site.) There is no coordinated effort to sell the books to the public, but if you want to purchase them, try writing to the festival directors at cec@cecudine.org.

So a tip of the hat to the dedicated Udine team, headed by Sabrina Baracetti, and a signal to you that if you have the time and the money to go, you would surely have a hell of a week. (Note that professors and students are offered lodging for some nights.) Who knows? A director might show up to put the audience in a movie, as Johnnie To once did. Even if you can’t make the trip, the quality of the publications makes them indispensible for research and enjoyable reading.

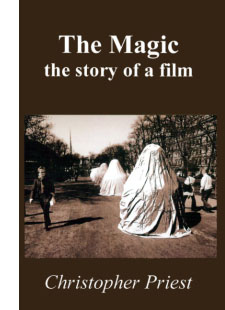

Rabbits from a hat

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

Priest is a lively writer, and he is frank about the ups and downs of the process. Initially he is happy that Nolan acquired the rights because the novel, a cunningly designed piece of misdirection, seems ideal for the director of Memento. But he confesses disappointment when the Prestige project is sidetracked by Batman Begins (“overlong, simplistic, and dull”). When the production gets under way, there are more swerves in the road. Given an early script, Priest admires the craftsmanship of Jonathan Nolan. But then he’s baffled that Christopher Nolan is saying two inconsistent things: that the film is completely different from the book, and that reading the book will spoil the film. Then again, during a press preview in Leicester Square, Priest succumbs to the film’s intricacies. “It has one of the most complicated and sophisticated narrative structures ever seen in an entertainment film.”

The story of the production ends here, but Priest goes on for about fifty pages to analyze the film in considerable detail. He dwells on the opening, which has no equivalent in his novel, and praises it for its fluent shifts among different points in story time. He appraises various aspects of the film, and he doesn’t stint criticisms. He notes that the Nolans stripped off his contemporary story, crucially altered the roles of the women, and turned his elusive mysteries into plot-driven secrets. Yet he concludes:

There is hardly a line of dialogue or moment of action in the film that can be traced back word-for-word, yet the whole thing is faithful to the novel in spirit, in story and in effect. I have differences with the screenplay in places, but none of those detracts from my general impression that it is a classic film adaptation of an existing novel, one which intending screenwriters would do well to study alongside the novel. (157).

Priest is a former movie critic (for the sturdy old British Film Institute publication Film) and an astute observer of what happens in a shot and on a soundtrack. He contacted me after my March blog entry discussing micro-repetitions in The Prestige and told me of The Magic. I ordered a copy pronto, and I’m glad I did. If you want to give your mail carrier a bit more job security, go to this page and click on GrimGrin Studio.

Take my film, please

Kristin here–

As I mentioned in our main entry about Ebertfest, Nina Paley’s animated feature, Sita Sings the Blues, was one of the highlights of the festival. Afterward I had the privilege of moderating the onstage discussion with the director and University of Illinois film professor Richard Leskovsky, who has a special interest in animation.

Sita has not had a regular theatrical release, though Nina has made it available to theaters, festivals, and everyone with access to a high-speed internet link-up. She gives it for free to anyone who wants it, believing that people who see it will pass the word along and that as the film becomes more well-known, it will become more valuable as well. Income should flow in. Nina is confident, some might say cocky about this. The thing is, she may be right. Sita is a terrific film, and I can well imagine a ground-swell of interest gradually building. Indeed, it’s happening already. Here I am, blogging about it, and others are as well. Non-bloggers are emailing their friends. Festivals have booked it up to the end of this year and beyond.

Roger Ebert found Sita early on, and his program notes were also his online review, which begins:

I got a DVD in the mail, an animated film titled “Sita Sings the Blues.” It was a version of the epic Indian tale of Ramayana set to the 1920’s jazz vocals of Annette Hanshaw. Uh, huh. I carefully filed it with other movies I will watch when they introduce the 8-day week. Then I was told I must see it.

I began. I was enchanted. I was swept away. I was smiling from one end of the film to the other. It is astonishingly original. It brings together four entirely separate elements and combines them into a great whimsical chord.

The four elements are: a sketchily animated account of the breakup of Nina’s marriage; the tale of Rama and Sita from the Indian epic, the Ramayana; musical numbers that all borrow recordings of Ms Hanshaw; and three shadow-puppet narrators who try, not always successfully, to recall the details of the Ramayana and its background history. As Roger says, somehow all this achieves complete unity.

The timing of the Ebertfest screening was fortuitous. Within the next few weeks, the DVD release is due. Of course, you can already watch it online and/or burn your own DVD. But for those who can’t or don’t want to, you can buy the DVD package, complete with what is described on the film’s website as a predownloaded copy of the film.

As Roger’s review says, Nina is a hometown girl. She started out doing comic strips and then made some  animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

Here’s a transcript of our conversation (that’s Nina at the far left, Richard, and me). Applause, laughter, and a fast-talking film director at times defeated my efforts to catch every word of my recording, so some details have been lost.

KT: I know you want to talk about how you’ve been getting the film out to the public, but I’d like to start off by talking about the film itself, which is fascinating. I think we can start with the computer animation. A lot of people think that you were pushing a lot of buttons and somehow the computer was generating the images. But obviously you were generating them yourself by painting and collage and so forth. Could you just start with the process of what you did before you put this material into the computer and then what you did afterwards?

NP: Well, there are a whole bunch of different styles and techniques used in the film. The style of the musical numbers, actually I drew that in Flash using a lot of really simple tools, so the perfect circles have a smoothness that you don’t get by hand. By the way, I want to mention that what you saw was not 35mm. You saw HD-cam, and there are actually 35mm prints of this, and seeing it here was very strange. It was unusually solid, rock solid, a little bit troublingly solid, although that is the ideal that film technology has been striving for. But 35mm prints have all these scratches and splices, and grain and a kind of warmth that moves around, which is almost like a kind of very desirable filter that really warms up the film. So watching it in 35mm is different. I was noticing how computery it looked on the HD projection at this particular size, because I was looking for imperfections that simply weren’t there.

But anyway, yeah, I did some paintings on parchment paper. To me, some things were simple, because I only had me working on the animation, and I used as many computer shortcuts as I possibly could. Most of the technique was what’s called “cut-outs,” so I made pieces of things, moved them around, and the computer does what’s called “tweening.” [i.e., in-betweening, filling in the frames between key points] There’s a little bit of full animation in there. It would take a long time to say everything that I did.

KT: Yeah, but every bit of that visual material was something that you put into the computer in some fashion, so that-

NP: The computer didn’t draw it, that’s for sure. I drew it, whether I started with paper or drawing on a little [digital] graphics tablet or eventually I got what’s called a Cintiq, which is a monitor you can draw on. You can draw straight into a program through the monitor, and so what’s on the monitor-it tricks you into thinking you’re actually drawing on the screen, but it went through both my hand and the computer.

KT: Is this the kind of thing you teach? Do your students learn how to do this kind of animation?

NP: No. I’d love to teach this. A lot of the students are just not [inaudible]. So right now I’m teaching visual storytelling, which is a much more basic class, and I taught something called “classic film and video” for a while at Parsons [School of Design]. I actually really like to teach artists. I’m teaching people who already know what they want to say and already have a voice and just need a little bit of technical-it’s slightly faster if they ask me rather than reading a manual. I learned by reading manuals.

RL: It struck me that you’re a woman artist making an animated feature, and actually one of the very first animated features, done ten years before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, was Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Ahmed, which also deals with Eastern myths. You actually did a little bit of the cut-out animation there, too, with the shadow-puppets. That brings a nice circularity-

NP: Well, hopefully this isn’t the last one!

KT: Was that the silent film that you referred to in your film?

NP: I still haven’t seen that film. First of all, everything has influenced me, because everything influences everything else. Culture [inaudible] language, so there’s a language of cell phones, a language of animation that comes from every piece of animation that’s been shared ever. So even if I haven’t been directly influenced by something, I haven’t seen the actual film, I will have been indirectly influenced by it simply keeping my eyes open.

RL: All the Annette Hanshaw songs are accompanied with the Flash animation, but it looked like there was a couple of different styles of Indian art represented there, from different periods. Tell us a little bit about what the choice was.

NP: The Ramayana is thousands of years old, and it also covers an enormous chunk of geography. It’s very popular not just in India but also in Cambodia, Thailand, Polynesia, Indonesia, this huge swath of South and Southeast Asia-parts of China. So there’s just this enormous range of art styles that have come up around it, and the styles I used in the film were influenced by just a tiny, tiny sample of that. Obviously shadow puppets. The designs were derived from puppets from Indonesia, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, and also India. There’s a whole slew of paintings. There’s lots of Ramayana paintings that were actually commissioned by Muslim [inaudible] who had money. There were collages of these traditional arts. Everything went into the hopper, all going into my head Everything goes in there, grinds up, and comes out.

KT: Traditionally in animation the entire soundtrack is done first, which is not the way it’s done in regular live-action filmmaking, but of course it’s virtually impossible to synchronize cartoons if you have someone doing the voices after the animation is done. So could you tell us a little about the soundtrack and how much of it you had ready by the time you started the visuals?

NP: Well, I should say, the whole production, it’s not like I had everything ready when I started the visuals. The way you’re supposed to make a film, first you’re supposed to write a treatment, and then you’re supposed to write a script, and then you’re supposed to, if it’s animation, have everything designed and do breakdowns and storyboards and this and that, and then at the very end you animate it.

I didn’t have to do that, because it was just me working and it was with a computer. So I came up with things as I was going along. The whole structure of the story was there, because the Ramayana is this very well-established story that’s been told billions of times. I knew that story. I also had the songs, so the first thing that I synchronized and edited was the songs. As I was working on those, I was figuring out how the rest of the film was going to come together. The [inaudible] part of the film was the three narrators, who were just friends of mine who I convinced to go into a recording studio, and I asked some questions about the Ramayana. They were all very busy and went, “Oh, I should have read more before.” The conversation that they had was actually quite typical, because I had so many conversations with so many Indians, who-it was just uncanny, they really captured the twenty-first century zeitgeist of Ramayana, I guess.

RL: That intermission was a bit daring.

NP: I should mention that the 35mm print, depending on where you see it, it has surround sound and the HD only has stereo. If you see it on 35mm, depending on what speaker you’re near, you’ll hear different complete conversations coming out of each. Some of those conversations are extremely funny. I recommend the left rear speaker. There will be Will Franken, who’s a distribution executive, talking about unsellable the film is. And there are people on the front right speaking Hindi. I think they’re saying, “I thought this was a children’s film.”

So, yes, intermission. Old American musicals had intermissions. I was watching some of them while I was working on the film, and sure enough, two-thirds of the way through, intermission comes up. Bollywood films still have intermissions-a three- or four-hour-long Bollywood film has a little gap. So it was a tribute to both old American musical films and all Bollywood films. When I showed the film in Livingston, New Jersey to an audience of primarily Indian-Americans, during intermission they just left for 15 minutes. And they missed my favorite part of the film, which is the part that comes a minute after the intermission.

Nina’s favorite part, shortly after the intermission

KT: I can second that statement about the 35mm, because I was lucky enough to see this film three weeks ago in 35mm at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it’s a different experience. I’ve enjoyed both of them, but I think there are definite advantages to 35.

It’s actually much easier for most people to see this film on a computer screen or television, because you chose a very unusual way to disseminate the film to the public. Can you talk a little about that?

NP: Why, yes, I can! You can see this film for free online if you go to sitasingstheblues.com and follow a variety of links and get the film. You can get everything from a streaming version from New York Public Television to a 200 gigabyte file from which you can make your own 35mm print if you have $30,000 to download it. Briefly, every file I have for the film is either online now or it’s going to go online. It’s a completely decentralized distribution model. People have compared it to Radiohead’s [inaudible] English model [for their “In Rainbows” album, 2007], but that’s different, because that relied on a single, central location where you got the audio, and it was tracked. It was simply what you decided to pay.

Mine is totally decentralized. I shouldn’t even call it “mine” anymore. It’s yours. This film belongs to you and everybody else in the world. The audience, you and the rest of the world is actually the distributor of the film. So I’m not maintaining a server or host or anything like that. Everyone else is. We put it on archive.org, a fabulous website, and encourage people to BitTorrent it and share it. That’s what’s happening, and we hope people do it more. There’s also broadcast versions, which you can download. If anyone here is from a television station, you can broadcast this for free.

Which begs the question, why is Nina Paley giving her work away for free? Doesn’t she want to get money? The answer is yes, I want to get money, and I believe that I will get money. I think I am getting money from this, because the more people share the film, the more valuable the film becomes. I have told people after screenings that they can get the film for free online, but I have some DVDs which I sell for twenty bucks, and here for twenty-five bucks-the Virginia is still remodeling, so this is for the Virginia.

I should also mention regarding DVDs that we, my mom-Oh, I should mention my mom! Sorry, I[inaudible] my parents, of course, who gave me the gift of life and all that, but my mom, who gave Sita Sings the Blues the gift of being its festival-relations manager, which is a huge, huge job. For those who don’t know, my mom was the main administrator of the math department of the University of Illinois and is a spreadsheet master and business-communications master and stuff like that and has been just essential to the film having such a successful festival life. So, thank you, mom! [Applause]

Anyway, I have made thousands of festival screeners so that festivals will have something to preview, and we’re down to the last 35, or at least we were this morning, and we handed them to the people in the Virginia, and that’s it for DVDs until a few weeks from now I’ll have the new purchasable DVD edition available.

RL: Will there be special features?

NP: Because the film is free, people can subtitle it freely, and the new one will have some subtitles. There’s gonna be more subtitles online. It’s been translated into French and Hebrew and Spanish and Italian and pirate. [applause and laugher covers a stretch of speech] The thing is, the film is now half-way. It will just continue growing, so whatever the DVD is, it’s just snatched off the stuff we have as of this week. So it’ll be the film, it’ll be a bonus feature called Fetch, a film I made, it’ll be some subtitles, I think there’ll be a couple different audio options.

It’ll be a very nice package, because basically what I’m selling is packaging for the film. If you have a computer, you’ve got your own packaging. You just download it. But many people just the same want an actual printed package. There’ll be two editions. There’s the artist’s edition, a limited edition of 4,999 DVDs, because for every five thousand DVDs I sell, I have to pay the licensers more money. You may think that’s too bad, and it’s OK if the other DVD distributors pay the licensers more money, but I [inaudible] paid $5,000 in order to decriminalize the film, so that I wouldn’t go to jail.

Jean Paley from the audience: Fifty thousand!

NP: Fifty thousand, yeah. Fifty thousand dollars is enough.

KT: Which is for the song rights.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

We were so relieved that Roger agreed that what copyright law has become is really not serving culture or people. These copyright extensions have really gotten way out of control. [applause] They [inaudible] me so much that I actually question copyright fundamentally, but even those who don’t agree, I think, that retroactively assigning copyrights is not actually acting as an incentive for dead artists to create more art.

Whereas these songs. It’s a scandal, these beautiful songs! Many people have never heard of them until seeing my film. That’s just a crime. She was a huge seller in the twenties. Huge! Why is it that we can’t hear her music? It’s because all the rights are controlled by corporations, and anybody who dares to share Annette Hanshaw’s music is risking a lawsuit or jail. As I did. As I decided I was willing to do. I didn’t realize I was doing civil disobedience at the time. I didn’t realize how severe the possible punishments were for doing this kind of thing, but even had I know I would have done it anyway. I have no regrets. Now, I’m turning into a full-time free-culture activist. [applause]

Some of you may know my dad is a retired math professor here. But I grew up in this science and engineering culture. In all these books about copyright, people always talk about scientists and how scientists share information. How it’s really important, this really strong ethic of sharing information. Scientists seek to discover some really great information to share it with the community, and that actually benefits the contributing scientist.

As an artist, it’s actually exactly the same. My status vastly increases as I share this film. But I think it’s quite possible that the way I was growing up here formed me that way, to see it this way. A lot of artists don’t see it this way. People see it as property. I just wanted to share what I’ve been thinking about a lot. [applause]

RL: Has your film prompted an Annette Hanshaw revival?

NP: Not an official one. I should mention that the only reason that these songs exist in a form in which we can hear them at all is because of the efforts of underground record collectors, because the corporations that have the official rights to control this music hadn’t done it. They actually scrapped the masters. There’s no surviving masters of Annette Hanshaw’s recordings, because they were so very valuable that in the forties they were sent for scrap metal. And yet somehow it would be theft if somebody in America released her recordings today.

But yeah, there’s this wonderful network of record collectors who just preserved her stuff on lacquer, and that’s how I originally heard her songs. I was staying in the home of a record collector, and he actually had Annette Hanshaw on 78s. And this is the tip of the iceberg. There’s so much amazing culture that we’ve forgotten all about and can’t get at. There’s this wealth of films that’s just sitting there, that nobody can restore, because if you restore a film you don’t have the rights to, you can get sued for showing it! And it’s very expensive to restore films, so the result is, nobody wants to touch it. Everyone is scared, and our cinematic history is disintegrating. It doesn’t last. Records actually last longer than film.

KT: We should point out that you have a very informative website, ninapaley.com.

NP: Yeah, it’s now blog.ninapaley.com, and there’s also sitasingstheblues.com, and I’m also artist-in-residence at QuestionCopyright.org.

KT: Most of the ways to get the film out to people that you’ve talked about would be DVDs or downloaded copies, but your film is still being shown in a lot of festivals, well into the future.

NP: Yeah, festivals and also cinemas. Hurray for independent cinemas! I support them, and they support me. [applause] There’s some great cinemas programming it. It’s going to be in Chicago at the Gene Siskel Film Center, very soon. And it’s going to be in Vancouver. It’s going to be in some other cities. And there’s no real time limit. There’s no advertising for this film, no paid advertising. The audience is also the public-relations department, so it’s gone completely by word of mouth, word of web, word of blog. There’s absolutely no end time. It can be screened anytime. There are some prints circulating right now, and hopefully any cinema that has a little off time and wants to give it a shot, can program it.

KT: Your mother was telling me that the film will be probably in two hundred festivals.

NP: Not two hundred. I think it’s been in a hundred.

KT: Well, there’s a long list on your website that goes into 2010, I think, so [to audience] you want to tell your friends who live in those various cities, see it on the big screen!

[Note: the list of screenings and festivals on the film’s website numbered exactly 200 as of May 4.]

NP: When I decided to give it away free online, what finally made me realize this was viable was when I realized that this didn’t mean it wouldn’t be seen on the big screen, that the internet is not a replacement for a theater. It’s a complement. Many people will see it online and go, “Wow, I wish I could see this on the big screen!” And so they can, and some people like to see it more than once. Another thing is, you see it online, and that increases the demand for the DVDs. So it’s the opposite of what the record and movie industries say. Actually, the more shared something is, the more demand there is for it. [applause]

RL: Are you doing this for your short films, too?

NP: I would like it for the short films. It’s simply a matter of time. I want to do it with my comic strips. I’m still seeking a volunteer, although someone contacted me from the U[niversity] of I[llinois], I think from the library, whom I need to call. Maybe everything will be scanned and uploaded right here from Urbana, which would be awesome. But yeah, I want to go back. Just as Congress is retroactively extending copyrights, I’m retroactively de-copyrighting all of my stuff and sharing it, because that will make it more valuable. Imagine some original comic strip that everybody knows. That’s much more valuable to people than a comic strip that no one’s ever seen. Andy Warhol, for example. Some Warhol print just fetched some huge price at auction. There was a photo of it up in the newspaper. We all know what Andy Warhol’s prints look like, even though most of us have never seen them in the flesh. We all know that they’re worth a lot, ‘cause they’re famous. They’re famous because people reproduce images of them.

[People do indeed. Here’s another of Nina’s:]