Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

Getting real

Art is not reality; one of the damned things is enough.

Attributed to Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and others.

DB here, with another followup to Ebertfest:

Ebertfest, once known as the Overlooked Film Festival, has always been keen to support American independent filmmaking. In previous incarnations, Roger spotlighted Junebug, Tarnation, and other movies that flew below the multiplex radar. This year’s crop was especially ripe. Besides The Fall and Sita Sings the Blues, there were important documentaries like Begging Naked and Trouble the Water. In particular, two fiction features set me thinking about types of independent storytelling and how they might be considered realistic.

The river is wide

Roger noted that when he first saw Frozen River, he wanted to bring it to his festival, but then it became the very opposite of an overlooked movie. It has grossed $4.3 million worldwide, a very healthy amount for a small-budget film without big stars. It won eleven national awards and was nominated for fourteen others, including a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. By now, you’ve probably seen it. I had been away during its Madison run, so I was happy to catch up with it.

“You have five minutes to show the audience you’re in charge,” commented director Courtney Hunt in the Q & A, and her film follows that advice. Seconds into Frozen River, we hit a crisis. Ray finds that her no-good husband has grabbed their savings and taken off to gamble, even as she waits for the delivery of their new prefab home. What begins as a drama of pursuit, with Ray trying to track down her husband, turns into a blocked situation. He’s gone and she has to not only pay off their mortgage but also keep her two sons going, counting on their school lunches to offset their domestic meals of popcorn and Tang.

Drama is about choices, and good drama is about bad choices. Ray has clearly made her share of mistakes—addictive mate, kids she can’t support, a bigscreen TV she can’t afford—and the plot shows her making the biggest of all. To scrape together money she agrees to transport illegal immigrants from Canada to upstate New York, driving across the frozen St. Lawrence. She casts her lot with Lila Littlewolf, a Native American with her own bad choices, and their common fate creates a series of parallels about motherhood that are resolved through Ray’s final sacrifice. The film also activates some current concerns about immigration, racism, and the problems shared by poor whites and ethnic minorities.

Resolutely unHollywood in its setting, theme, and characters—deglamorized women, especially—Frozen River still adheres to classical script structure. We have characters with goals, encountering obstacles and entering into conflicts, and the turning points come at the standard junctures. The ending is a resolution, although not an entirely happy one. In the course of the plot, suspense is built up at many points. Will Ray and Lila be caught by the state troopers who grimly monitor their comings and goings? What will become of that abandoned baby? The film is a sturdy example of how classic principles of construction can be applied to subject matter that is worlds away from our prototype of Hollywood filmmaking.

Neo-neo and all that

Ramin Bahrani’s Chop Shop, which I was also just catching up with, offers another flavor of independent dramaturgy. Roger has been a staunch supporter of Ramin’s films since Man Push Cart, and he has declared him “the new great American director.”

Bahrani has mastered a somewhat different narrative tradition than the crisis-driven plotting of Frozen River. “Neo-neorealism,” A. O. Scott has called it, linking Goodbye Solo to Wendy and Lucy, Treeless Mountain, Old Joy, and other films that offer us an “escape from escapism.” Now, Scott suggests, American cinema is having its delayed Neorealist moment. Richard Brody offers some useful, sometimes scornful, qualifications of Scott’s conjecture, reminding us of the urban dramas of the 1940s and the rise of Method acting. Scott has replied, claiming that their dispute essentially depends on their differing tastes in movies.

Here’s my $.02. “Neorealism” isn’t a cinematic essence floating from place to place and settling in when times demand it. The term, like the films it labels, emerged under particular circumstances, and it’s hard to transfer the label to other conditions. Moreover, there are many problems just with applying the term to Italian cinema, since it tends to cover not only the purest cases, like Bicycle Thieves, but also more mixed ones like the historical drama The Mill on the Po.

Still, because postwar Italian cinema had a big influence on other national cinemas, we have a prototype of The Italian Neorealist Movie. The filmmaker focuses on the lives of working people. He emphasizes their daily routines and travails. The film will be shot on location (at least in the exteriors) and may use nonactors in some or all roles. Bazin pointed out that we’re likely to find an elliptical or unresolved plot. It’s also very likely that we’ll see washlines and women in slips.

Why not just call this an Italian variant of that broad tradition of naturalism or verismo or “working-class realism” that we find in many national cinemas? In France there was the work of Andre Antoine (e.g., La Terre, 1921) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidele (1923) and his lyrical barge romance La Belle Nivernaise (1923). More famous are Renoir’s Toni (1935) and The Lower Depths (1936). (Recall that Visconti was Renoir’s assistant on A Day in the Country, 1936.) In Italy, there were harbingers too, not only the famous ones like Four Steps in the Clouds (1942) but also the charming Treno Popolare (1933). And Japan gave us many instances in the 1930s, notably Ozu’s Inn in Tokyo (1935) and The Only Son (1936).

Realer than real

On an Ebertfest panel Ramin Bahrani argued for a realist aesthetic. “Most people in movies never seem to pay rent or keep track of how often they can eat out . . . [Ordinary people] have day-to-day struggles; they ask how to survive.” That’s to say that a realistic work is distinguished primarily by its subject matter, the social milieu it presents. Bahrani also mentioned that some plot devices are unrealistic. Criticizing Slumdog Millionaire, he remarked: “My world doesn’t end in a Hollywood fantasy.” He didn’t deny the need for a dramatic structure, but he did insist on avoiding “obvious plot points like ‘He crossed the door and can’t go back.’”

This leads me to another $.02 contribution. I’m reluctant to contrast realism with something like artifice or formula. To me, realism comes in many varieties, but none escapes artifice. All realisms I know rely on conventions shaped by tradition.

For example, Chop Shop shows us a slice of life that most of us don’t know, the world of garages and salvage yards clustered around Shea Stadium. Such a low-end milieu is a convention of literary naturalism (Zola, Gorki). In this tradition, an artwork acknowledging the lives of the poor gains a dose of realism that, say, a novel by P. G. Wodehouse or a play by Noël Coward will lack. Some critics complained that when Rossellini’s Europa 51 and Voyage to Italy presented upper-class life, he left Neorealism behind.

There seem to me other conventions at work in Chop Shop. In one garage we find a boy, Alejandro, who has two goals. He wants to set up a food van that will sell meals to the men working in the neighborhood, and he wants to keep his sister Isamar safe from bad companions. Goal-driven plotting is central to Hollywood dramaturgy, as it is to much literary realism (e.g., An American Tragedy). It’s true that in real life people often form goals, but many do not, and those who do seldom come to a state of heightened awareness in the time frame typical of a movie’s plot. Alejandro fails to achieve one goal but partially achieves another, so we have an open, somewhat ambivalent ending—another convention of realist storytelling and modern cinema (especially after Neorealism). Life goes on, as we, and many movies, often say.

Instead of following a crisis structure, as Frozen River does, Chop Shop presents what we might call “threads of routine.” Most scenes consist of ordinary activities: the work of the garage, Alejandro’s sales of candy and DVDs, opening and closing the shop, Alejandro watching from the window of his room. But these vignettes aren’t sheer repetitions. They vary as Alejandro encounters progress or setbacks with respect to his goals. Most of the routines establish a backdrop against which moments of change and conflict will stand out.

Building a movie out of routines can also make convenient coincidences seem plausible. For instance, dramas have always relied on accidental discoveries of key information—the overheard conversation, the token that betrays what’s really happening. In Chop Shop, Ale and his pal Carlos discover that Isamar has become one of the hookers who service men in the cab of a tractor-trailer. They might have discovered this, as in life, by simply wandering by the spot on a single occasion. Instead, Bahrani’s script motivates their discovery by explaining that they habitually spy on the truck assignations. “Let’s go to the truck stop and see some whores.” Planting information in scenes of everyday activities seems more natural than giving it special emphasis at a moment of crisis. In two later scenes, the truck-stop becomes an arena for conflict, so Ale’s initial discovery motivates his later actions.

As for plot points, Chop Shop has them. (At about 15 minutes, the zone of the Inciting Incident, Ale declares his intention to buy the van. At about 30 minutes he discovers that Isamar is turning to prostitution.) Likewise, the threaded routines yield poetic motifs, such as the pigeons that are carefully established early in the film. Bahrani’s plotting is meticulous, and it highlights the paradox of realism: It takes effort and calculation to “capture reality.” De Sica was said to have endlessly rehearsed the boy in Bicycle Thieves.

What gives the film a more episodic organization than Frozen River, I think, and what gives it a greater sense of “dailiness,” is that it lacks deadlines. There’s relatively little time pressure on the action, except for Ale’s sense that he’s getting close to having enough money for the van. Chop Shop’s refusal of Hollywood’s ticking clock seems to me to confirm the observation, made by Geoff Andrew and J. J. Murphy, that in some respects American indie film is located midway between classical narrative cinema and “art cinema.”

The threads-of-routine pattern can be harnessed to character-driven drama, as in Chop Shop, but it can also be more opaque or minimalist. During at least half of Elia Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance, we watch anonymous characters go through routines, but instead of revealing their psychological drives, the scenes show the people overwhelmed by their surroundings. Narrative development is charted through changes in the spaces that the figures inhabit and vacate. The result is a “surreal realism” that evokes the anxieties of Magritte or de Chirico.

To say that realist traditions rely on conventions doesn’t make them less worthwhile. Chop Shops seems to me quite a good film. Nor would I deny that realist conventions do capture some aspects of real life. Both the crisis structure and the threads-of-routines structure can be taken as realistic. Sometimes our lives are in crisis, and at other times we do just plod along. But more stylized narrative forms can capture important aspects of reality too. The Searchers, a work of high artifice, renders a portrait of a self-destructive racist that many of us recognize in the world outside the movie house. Has any film better caught the adolescent yearning for romantic love and family stability than Meet Me in St. Louis?

The problem comes when we think that only one variant of realism can lay claim to validity, let alone beauty. Sometimes fidelity takes a back seat to vivacity. In Roy Andersson’s films, everyday nuisances like checking in to a plane flight or waiting in a clinic are inflated to grotesque, gargantuan proportions, becoming torments in a vision of hell. Like all caricatures, the exaggeration captures something true.

Comparing Wilkie Collins and Dickens, T. S. Eliot notes that both writers give us vivid characters. Collins’ characters are “painstakingly coherent and life-like,” terms of praise that we could assign to Bahrani’s films as well. But, Eliot adds, “Dickens’ characters are real because there is no one like them.”

What was Neorealism? Some of André Bazin’s invaluable essays on the subject can be found in What Is Cinema? vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). Kristin and I offer a survey of some historical factors in Chapter 16 of Film History: An Introduction. (Go here for a little bibliography.) For more on art cinema and its commitments to realism and open endings, see my essay, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 151-169. On American indies’ borrowing of art-cinema conventions, see Geoff King, American Independent Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005) and J. J. Murphy, Me and You and Memento and Fargo (New York: Continuum, 2007). J.J. also has a blog entry on Chop Shop here. The quotations from T. S. Eliot come from “Wilkie Collins and Dickens,” Selected Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1950), 410-411.

Songs from the Second Floor (Roy Andersson, 2000).

Virginia Theatre on our minds

Left to right: Kristin, unidentified ardent moviegoer, Erik Gunneson, and Meg Hamel.

Kristin here–

A year ago, those of us attending Roger Ebert‘s Film Festival were forced to do without the presence of the moving force at the center of this lively annual event. Still in therapy from his health crisis of 2005, Roger fell and broke his hip. Characteristically, he struggled to convince his doctors that he could take an ambulance to Champaign/Urbana, but their caution prevailed.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Roger went onstage at intervals during the festival, and he made his first appearance to introduce the opening night’s film, the director’s cut of Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace and Music (1970). Thanks to dedicated software, Roger tapped out messages on a laptop and pushed a button. A voice with a British accent conveyed his words of welcome to us and to director Michael Wadleigh. Then Roger retired to the back of the theater, where a comfy chair is reserved throughout the festival for him.

Michael Wadleigh, Jocko Marcellino, and Dale Bell discuss Woodstock.

From the perspective of nearly forty years, Woodstock has become both a record of remarkable musicians in their prime and a valuable document of the youth culture of the late 1960s. I was a junior at the University of Iowa at the time of the concert, only about five months away from taking my first film course and changing the direction of my education from tech theater to cinema studies. Working on props and make-up for productions every night, I was only dimly aware of the concert or the film that followed.

I also admit I don’t know much about pop music. I kept asking David “Who’s that?” Jefferson Airplane, The Who, Joe Cocker, and others were just names to me, not people whose appearance or music I recognized. But I could appreciate the remarkable way in which the filmmakers were able to capture live performances: the fluidity of multiple, 16mm cameras filming onstage only feet from the performers, the maintenance of focus even when events were recorded at night in less than ideal lighting conditions, and the excellent sound recording.

The screening heralds the release of the new version on DVD on June 9. Amazon has it on pre-order in 3-disc Blu-ray and DVD boxes, as well as a 2-disc set. The third disc has some making-of featurettes and about two hours of additional concert footage left out of even this extended version. I can’t imagine anyone who wants a compilation of performances by this remarkable group of musical talent settling for the smaller set.

Von Sternberg and Jannings, round one

The Alloy Orchestra has become a fixture at Ebertfest. This year’s silent film was Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command. I hadn’t seen it in thirty years or more, and it’s better than I remembered it being. Of course, seeing a gorgeous print on the big Virginia screen with an excellent musical accompaniment does it more justice than an old 16mm copy. Von Sternberg’s images were luminous, and his depiction of silent filmmaking as accurate as anything you’ll see on the screen.

In von Sternberg’s autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, he spends most of the six pages devoted to The Last Command badmouthing star Emil Jannings, with a brief sidetrack to badmouth William Powell. Presumably he’s talking about their behavior on the set, since their performances are both impressive, with Jannings emoting away and Powell as stone-faced as Buster Keaton. Von Sternberg reports that he and Jannings vowed never to work together again. Maybe winning the first Academy Award as best actor changed Jannings’ mind, for a few years later he invited von Sternberg to direct him and Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. The rest, as they say, is history.

Drawing on their usual range of odd percussive objects, including a bedpan, the Alloy group provided a lively score. With Chicago Tribune critic Michael Phillips as moderator, Guy Maddin and I joined the orchestra members for a discussion afterwards. One of them hinted to me backstage that a score for Docks of New York might be in the offing, which would round off the von Sternberg series perfectly.

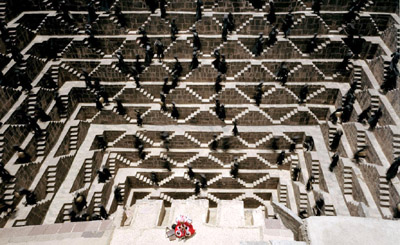

Saturday matinee

Last year the festival presented Tarsem Singh’s The Cell, with its delirious production design by Eiko. Tarsem’s 2008 follow-up, The Fall, got less attention in theatres, not having a star like Jennifer Lopez to carry it with audiences. It’s a complex fantasy set in a hospital during the silent-cinema era. There a suicidal, injured stuntman telling the tale of a band of mythical heroes bent on revenge to a seven-year-old girl with an arm cast. Her visions of the narrated events, set in spectacular landscapes and exotic buildings, mutate as she insists on changes in the story. The Fall was distinctly a crowd-pleaser, at least for the indefatigably enthusiastic audience in the Virginia Theater. Its Romanian child star, Catinca Untaru, is now twelve, and she proved an articulate charmer as she answered questions after the screening.

Ramin Bahrani with Catinca Untaru and her family.

The next film was Sita Sings the Blues, a marvelously imaginative animated feature by Nina Paley. I had seen the film two weeks earlier at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it was a treat to see it on the big screen again. It’s available for download in various formats here. I had the pleasure of moderating the discussion afterward, and I like the film so much that I’ll be blogging on it separately, including a transcript of the Q&A.

Tattling and bullying

DB here:

A Belgian friend, the late Michel Apers, admired American films above all others. One of the reasons, he explained, was that our films analyzed our political system with uncommon clarity. No other national cinema, he claimed, focused so insistently on the mechanisms and purposes of government, on the duties of citizenship, and on the dilemmas of public life. Not wanting to seem too chauvinistic, I said that we often failed to fulfill our nation’s ideals. “Of course,” he said. “But at least you have ideals. And your films show that it is not easy to live up to them.”

Michel’s remarks reminded me that we do have a tradition of politically critical films: 1930s films opposing lynching and hate groups, 1940s films about political corruption, still later movies like Twelve Angry Men and The Best Man and The Manchurian Candidate. Directors who contributed to this tradition include John Ford (Young Mr. Lincoln, The Last Hurrah), Otto Preminger (Advise and Consent especially), and Alan J. Pakula (All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, Rollover, The Pelican Brief).

Rod Lurie’s favorite film is All the President’s Men, which ought to tell you where his heart is. He made The Contender (2000), a subtle drama about a woman nominated for Vice-President. It has the trappings of a political thriller (the conspiracy at its heart echoes Chappaquiddock, as well as Blow-Out), but that’s just the bait for its serious questions. Graced by a warm but steely performance by Joan Allen, The Contender asks whether a woman in politics is held to a higher standard of sexual conduct than a man would be.

I thought of Michel Apers’ remarks when I watched Lurie’s Nothing But the Truth (2008) at this year’s Ebertfest. The plot revolves around a reporter, Rachel Armstrong (Kate Beckinsale), who outs covert CIA agent Eric van Doren (Vera Farmiga, her of the admirably crooked smile). Rachel refuses to divulge her source and goes to jail. Again, there’s a mystery to draw us through the plot: Who is the source? But more important is the problem of whether a reporter should be forced to name sources in a case that breaches national security. It’s the sort of issue that Preminger or Pakula would have loved to tackle.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

While the debate plays out, Rachel languishes in jail, her family and career dissolving. The case has some analogies to the Valerie Plame incident, but Lurie stressed that the film takes on a similar situation but not comparable characters. He was inspired as much by Susan McDougal’s tenacious loyalty to Bill Clinton.

The film’s secret about Rachel’s source is no mere Macguffin. It provides a powerful supplementary reason for Rachel’s silence, yet it doesn’t wholly excuse it. The film’s last scene leaves you wondering whether Rachel exploited her source. The film’s last shot suggests that she’s wondering too. That shot also wraps up a visual motif that hangs Rachel’s face on one extreme edge of the 2.40 frame, making her look precarious and vulnerable.

All in all, Nothing But the Truth is a sober, unsensational, gripping film about the press’s rights and obligations. It’s not surprising that Lurie was a professional journalist. During the Q & A, the questions were probing and he responded with rapid-fire, well-shaped sentences. There was good humor as well. After Lurie promised to tell us who slept with whom on the shoot, he paused and said: “All I’ll say is that Alan Alda was a complete slut.”

The opportunity for ordinary moviegoers to talk with such gifted and committed filmmakers makes Ebertfest one of the great film festivals on this continent. Roger’s urge to communicate with as many people as possible naturally inclines him toward creating communities, and the folks who gather annually in the Virginia Theatre form one of the most genial and generous group of movie lovers I’ve ever encountered.

Hong Kong wrapup: Places and faces

DB here, just back:

The numbers are pretty staggering. The Hong Kong International Film Festival ran 22 days (the first four incorporating Filmart, the Asian market). In 510 screenings, 279 films from 50 countries were shown. There were 19 world premieres, 17 international premieres, and 33 Asian premieres. Attendance figures are yet to be determined, but so far things look to match the nearly 600,000 tickets sold last year. (*Correction 1 May 2009: The figure of 600,000 refers to an estimate of total attendance at all events, including free screenings, panels, seminars, etc. Total tickets are currently estimated at 100,000. Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for the correction.)

Having stayed for the whole event, I felt some festival fatigue. But the final days of the fest were full of fine movies. I left feeling that all my time was well-spent—not least in seeing old friends and visiting some of the outstanding spots in this adrenaline-fueled city.

Ken Smith and Joanna Lee are forces of nature in the cultural life of Asia. Working mostly in musical performance, they arrange for performers’ tours, consult with cultural agencies, translate, write, and do damn near everything else as well. Call them global impresarios. They helped coordinate the YouTube Symphony Orchestra, and they played central roles in the creation of the opera The Bonesetter’s Daughter, a collaboration between Amy Tan and Stewart Wallace. This resulted in a 2008 production by the San Francisco Opera. The September premiere was broadcast in Hong Kong last Easter Sunday, and will be available at the RTHK website for playback for the following 365 days. Give it a listen here.

Ken’s engrossing book, Fate! Luck! Chance!, documents the making of the opera and includes a libretto. You can read background on Ken’s book here.

Above, Ken and Joanna take in pudding at a historic hole-in-the-wall eatery. The pudding comes in two varieties, milk and eggyolk-based. Mighty sweet, and as if by chance (or fate, or luck), the stools mimic the main attractions.

Old friends Linda Lai Chiu-han and Hector Rodriguez teach in the digital media and arts program at the City University of Hong Kong.

Linda has just had a film accepted for Oberhausen. She’s on a roll: It’s her second screening in this, the major festival for short films.

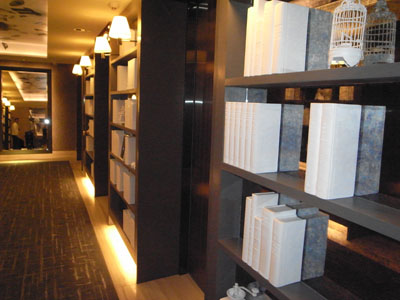

The W Hotel, where the Festival was headquartered, was posh to the max. Every time I went in, I expected someone to figure out that I wasn’t well-dressed enough to be there. If you ever wondered what George Segal’s ghostly sculptures would read, you could check out these pale volumes fastened to the shelves along the elevators.

My own hotel was somewhat different. The B. P. in B. P. International House stands for Baden-Powell, and the place was teeming with Boy and Girl Scouts nearly every day. In the modern atrium hangs a reverent portrait of the man himself.

It was pleasant to stay beside Kowloon Park. Headed for the Cultural Centre or the ferry, I could avoid the crowds on Nathan Road by ambling through the park.

While I was in town, developers put the finishing touches on a neo-retro-colonialist complex at the south end of Canton Road.

You must admit that Hong Kong sorely needs another shopping mall.

Back to the faces: Gary Bettinson (University of Lancaster), Emilie Yeh (Hong Kong Baptist University), and Darrell William Davis (Lingnan University).

Gary writes on contemporary Hong Kong cinema, particularly Wong Kar-wai; most recently, he has an essay on 2046 in Warren Buckland’s anthology on puzzle films. Emilie researches Chinese film, as does her husband Darrell, who started his career working on Japan. I’ve already mentioned their book on Asian media industries in an earlier blog, but also have a look at their fine Taiwanese Film Directors: A Treasure Island. I gave a talk for Emilie and Darrell at HK Baptist, and we had a good discussion among their students and colleagues.

More intellect: This year the festival paid tribute to Ingmar Bergman. A friend of his, Marie Nyreröd, brought her enlightening documentary, Bergman’s Island. Here she’s seen with another Bergman expert, my amigo Paisley Livingston, philosopher and film critic-theorist teaching at Lingnan University.

For over forty years, Erika and Ulrich Gregor have been colossal figures in world film culture–as critics, archivists, and festival programmers. They served on two juries during their stay here.

Scan earlier years of my Hong Kong visits and you’ll find these three regulars: King Wei-Chu (FantAsia programmer), Peter Rist (Film prof at Concordia of Montreal), and Yvonne Teh, Hong Kong journalist. After a screening at the Science Museum, it’s wonderful to sit out in a cafe.

Here are Johnnie To and his right-hand man Shan Ding at To’s magnificent office in Milkyway Headquarters.

The Milkyway team is busy. To’s Vengeance, starring Johnny Hallyday, will open in Paris on 20 May. Mr. To and Shan continue to work with their collaborators on a remake of Melville’s The Red Circle, and they’re preparing a New Year’s comedy as well. Here’s Cheang Soi, one of the most ambitious of the younger HK directors (Love Battlefield, Dog Bite Dog). Soi is finishing Accident, which looks to premiere at the end of the summer.

John Shum (aka Sham) is a legendary figure–a comedian since the 1980s, a producer, and an energetic advocate for local democracy.

Wong Ain-ling has been a critic and festival administrator. Currently she works as Senior Researcher at the Hong Kong Film Archive. She played a crucial role in the restoration of Fei Mu’s Confucius.

Derek Kwok (director of The Pye-Dog) is again collaborating with legendary actor-singer Teddy Robin Kwan.

In all, another wonderful year of food (and food for thought), talk, and above all movies. You won’t find a festival anywhere more dedicated to the power of film in all its variety. So once more my tagline: See you here next year?

At the Film Workshop party: Lau Siuming, John Woo, Johnnie To, Tsui Hark, and Benny Chan. Thanks to Alvin Tse for the photo.

Passion, mortality, and everyday life

DB, flying back from Hong Kong:

Some of the most important films playing at the Hong Kong International Film Festival were already familiar to me—Still Walking, Il Divo, Gomorrah, Ashes of Time Redux—and some of my discoveries in Hong Kong have been covered in more recent entries.

What remains? Accentuating the positive, I’ll not talk about the disappointing items, some with strong reputations. I hope to blog about others in the months to come, when I’ve had a chance to study DVDs.

In the meantime, Kristin has already touched on Beaches of Agnès, a real charmer. Varda can be whimsical without turning fey; even dressed as a potato she doesn’t seem to be trying to grab attention. The film is a digressive, passionate memoir. The background on her early life is captivating, and her career as a photographer, shooting snaps of Pierre Vilar and Gerard Philippe, furnishes a stab of pathos. A montage of beautiful boys and girls: gone. Soon we get Varda’s straightforward acknowledgment of Demy’s death from AIDS. “All the dead lead me back to Jacques.”

Götz Spielmann’s Revanche, which I’d passed up at other fests, was a very solid psychological thriller. It’s built around two contrasting worlds, the sex trade of Vienna and the placid, churchgoing lifestyle of a village. From the first comes Alex, a man-of-all-work in a brothel. He falls in love with a Ukrainian hooker, and between bouts of cocaine he vows to help her escape the business. In the village live the policeman Robert and his wife Susanne, trying to have a child. Their life is secure and cozy, though Robert is wound a bit tight. The two worlds intersect during a bank robbery, and the rest of the drama plays out in the countryside, with Alex taking refuge on his grandfather’s farm. Alex and Robert become two variants of masculine anxiety, each defined by his way with a pistol, and their decisive confrontation is deftly postponed until the very last moments of the film.

I admire the way that Spielmann uses a spare long-take technique to increase suspense. Each scene usually consists of a single shot, taken from a judiciously chosen angle that unfolds the drama smoothly. There are barely 200 shots in nearly two hours, but the scenes don’t seem stiff because the framing and staging are quietly varied. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is reserved for two turning points, one in the middle and one at the end. It’s nice to see a movie with no filler material, no passages of people driving in cars or going into the buildings, none of those time-wasting aerial shots of cities.

Some nice sound work too! No Country for Old Men has been rightly praised for its use of offscreen noise, but the Coens look rather showoffish compared to what Spielmann has accomplished here. A shot of Robert and Susanne on their patio is accompanied by the faintest rustle on the right channel: Alex, spying on domestic happiness like a character out of Highsmith or Ruth Rendell, has slipped away.

Similarly elegant in its staging and sound work is Claire Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum. The teasing exposition—a man watches commuter trains, a young woman rides one—dares us to imagine scenarios that could involve both. Our speculations turn out to be too wild, since their relationship is the most uncomplicated to be imagined. Based frankly on Ozu’s Late Spring, 35 Shots builds up its drama through daily routines, following its principals and their neighbors in everyday situations until, quite unexpectedly, a quiet crisis blossoms. Soon one scene ends: “We could be like this forever.” Next scene: everything has been overturned, and characters must change their lives. Visually the film is a marvel, with glowing scenes of semidarkness and discreetly out-of-focus details. As in her masterful Beau Travail, Denis supplies a powerful last shot, this time of an object we’ve nearly forgotten.

Two more thoughts: In my discussion of Revanche and 35 Shots, I’ve had to be coy in explaining basic plot situations and character relationships. That’s because these films work elliptically, holding back the sort of expository information that would be given in a concentrated dose early in most classical narratives. This narrational strategy poses no problem for an academic analysis, which tends to assume that the reader has seen the film. But it’s more difficult to handle when you’re writing a review. You don’t want to spoil the viewer’s surprise by explaining a core situation that the filmmaker has chosen to unfold gradually. If reviewers of Hollywood movies can’t give away the ending, the reviewer of an art film probably shouldn’t give away the beginning, or at least the information that it keeps in suspension for some time.

In other respects, though, there isn’t a clear dividing line between the “psychological” drama of international festival cinema and the more “externally driven” action of mainstream entertainment. Popular cinema relies on physical props like clues, souvenirs, messages, and gifts to help drive the plot. So, less obviously, do art films. The two photographs in Revanche deepen the character drama while triggering a major realization. The accidentally discovered letter (a convention of melodrama akin to the overheard conversation) in 35 Shots not only explains past actions but primes us to expect some conflict to come. As Aristotle knew, stories seem to need tokens to drive character revelation and plot reversals. A narrative universal?

Japanorama

Naked of Defenses.

Many of the movies I most enjoyed were Japanese. No surprise there. I know I’m prejudiced in favor, but objectively speaking the Japanese industry has long combined high output with great diversity and depth. I’m inclined to think that across film history, the three most consistently excellent filmmaking nations have been America, France, and Japan.

During Filmart, Yoshizaki Masahiro gave a swift but informative report on the current state of Japan’s “content industry.” It is the currently the world’s second-largest national film market , but it will sooner or later be replaced by China. Currently Japanese films are reclaiming the local audience, sometimes grabbing over half the annual box office. Unfortunately, that audience isn’t growing, and with a plunging birthrate, it’s unlikely to do so. Moreover, Japanese cinema has always been difficult to export, even in Asia. The great exception, of course, is anime, but even that is starting to slump. Anime is largely a television/ video format, yielding about twice in those platforms what it yields in theatrical income. But as advertising dollars have withered in the recession, anime has been cut back.

Despite all this, Japanese companies manage to release a staggering 400 or so films per year. (What counts as a release—theatrical? direct to video?—we leave for another day.) And the variety remains remarkable, judging by what I saw during my stay in Hong Kong. Put another way: Japan makes movies that are sweet, touching, funny, silly, and peculiar to the point of perversity. Not necessarily perversion, but that’s there too. And yes, schoolgirls’ panties are involved.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

The film maintains its infectious pacing, adorning the action with minor-key gags like the airport’s “Somkin Room” for smokers. I also liked the moments of teamwork. When the stewardesses need a cake, they concoct one out of various packaged snacks. A young mechanic, constantly berated by his boss, thinks he’s dropped a wrench into the plane’s engine, and the whole ground crew searches the hangar for it. As with Airplane!, the final credits resolve several plotlines and add a few gags. If you like Waterboys and Swing Girls, also directed by Yaguchi Shinobu, you’d probably enjoy this.

Just as light, but a lot more intricate is Nakamura Yoshihiro’s Fish Story. Another network narrative, this one traces how Japan’s purported first punk song changed the course of history. The plot skips among periods from 1953 to 2012, when a comet is about to incinerate the earth. With many pop-culture in-jokes, from Beatles albums to The Karate Kid, this breezy, off-kilter item gets by on sheer adrenaline and on a cascade of puzzles. Why does the Fish Story song make no sense? Why does it contain a one-minute passage of silence? How are all these stories connected? And how can a song save the world? The narration cleverly withholds the basic relationships among the characters until a dizzying montage at the end wraps everything up.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

A more straightforward Japanese entry in the Asian Digital competition was Ichii Masahide’s Naked of Defenses (the most awkwardly titled film I saw). Two women work at a factory making plastic parts. Ritsuko, a plain but dogged supervisor, is becoming alienated from her husband after her miscarriage. She envies the pregnant and insouciant new hire Chinatsu, whose marriage is overcoming its problems. Plain and sincere in its technique, Naked of Defenses ends with an astonishing sequence. By all the evidence onscreen, Ichii got a pregnant woman to play Chikatsu and filmed her giving birth. Balancing this powerful ending is the striking performance of Moriya Ayako as a woman sinking into depression but who may be saved by friendship and maternal love.

I took the occasion to catch Departures at a local theatre, since I had missed it at earlier festivals. And I’m happy to report that it’s distributed in the US by Regent Entertainment, run by Wisconsin graduate and old friend Steven Jarchow.

By now you’ve probably seen Departures too. At one level, it’s a good old-fashioned Shochiku movie, mixing tears and good-natured humor. Some decry it as middlebrow sentiment, but I found it a touching, fluent tale. For me, the central attraction is the repertory of gestures. Our two professionals handle the recently deceased tenderly, but that doesn’t preclude a crisp efficiency in flaring out a sleeve. I don’t think I’ll forget the way the undertaker grasps the dead person’s clasped hands and then executes a circular snap. Precise manipulation becomes a sign of respect.

And it isn’t all sunniness. Handling dead bodies is hazardous cultural territory in Japan. It is traditionally a task for the burakumin, a minority group long looked down upon. Although discrimination against the group has apparently diminished, the fact that a big star like Motoki Masahiro could play the role of a corpse-preparer could help dispel a lingering social stigma.

You could almost mount a Japanese film festival about mortality. Some musts would be Ozu’s Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family and Tokyo Story, Kurosawa’s To Live, and Kore-eda’s After Life. Another required item would be Dying at a Hospital (1993), a rarely seen Ichikawa Jun film screened as part of a tribute to the recently deceased director. It consists of staged episodes showing a few cancer patients in their last months. An elderly husband and wife both have cancer, but must separate and be treated in different hospitals. A widow laments her rotten luck. A lively young man can’t accept the fact that he won’t see his children grow up. A homeless man is brought in, filthy and disoriented, and as he becomes aware of his plight, he still apologizes for accidentally turning up his pocket radio.

These and other cases are accompanied by voice-over narration from the doctor and nurse who treat them. Interspersed with these scenes are rapid documentary montages of people enjoying life—eating, drinking, viewing cherry blossoms, celebrating festivals, just walking down the street. The intimate facial reactions we’re denied in the hospital scenes are supplied in these vérité passages.

Dying at a Hospital is gentle and sympathetic, but its manner of shooting gives it special resonance. The hospital scenes are shot in planimetric fashion, with the camera rigidly facing a row of three beds, or a pair of beds, or only a single one. Everything is played in long shot, with no close-ups or camera movements to enlarge the faces.

Patients, visitors, and hospital staff move through these blocks of space. The lighting effects are particularly subtle, accentuated by very gradual fade-ins and fade-outs, as if dawn were breaking or night were coming on. As the film goes on, Ichikawa introduces variations in scale and new cutting patterns, creating what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film a sparse version of parametric narration. For instance, the spaces become more compact as terminal patients are shifted from a shared room to a private one, which permits nuanced effects of distant depth.

Ichikawa’s dry, physically detached treatment lets the poignancy of each situation emerge without any directorial boosting. The glimpses of daily life outside the hospital, zestful and shot on the fly, generate a powerful contrast: the preciousness of ordinary pleasures, and the dignity that must be accorded everyone about to leave them behind.

For a brief but sensitive appreciation of 35 Shots, see Ryland Walker Knight’s comments here–perhaps best read, for reasons mentioned above, after you’ve seen the film.

Departures.