Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

Pandora’s digital box: At the festival

Of the thirty-three titles I saw at the Toronto International Film Festival this year, only nine were projected on 35mm film. The rest were shown on HDCam or Digital Cinema Package. At the first TIFF I attended in 2002, I saw a comparable number of films and all were projected on 35mm or 16mm film.

Jim Healy, Director of Programming, University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque

DB here:

Do you complain about ads before movies? In the Digital Age you can expect more of them because there will be ads for the theatre’s projector and server and even the financing agent that supplied them.

The most aggressive preshow attraction, which I saw before every digital screening at this year’s Vancouver Film Festival, is the one promoting Dolby servers. Play when ready.

A dirty film countdown leader explodes into sleek digitalia, alchemizing cinema into the four elements. Photochemical imagery can’t bear trial by fire and is annihilated Terminator-style. But the flames are extinguished by earth (flowers), air (blue vapor) and icy water. McLuhan said film was a hot medium, but does that automatically make digital cool?

Take the clip as a victory dance. By September, when I saw the Dolby Armageddon trailer, things had already tipped. Digital projection, the immediate future for multiplexes and for small-town houses, has become a festival mainstay too. But the problems are more marked on the fest scene than in commercial venues. If you visit a festival and there’s a hiccup during a screening, count to ten before hollering. The staff, already overstretched, is facing something far less tranquil than the concluding frames of the Dolby ad–something more like the hellfire frames you see at the start.

Screener savers

Screener for Target (Alexander Zeldovich. 2011).

Films get into festivals two ways: By being invited or being submitted blind. A programmer might invite a film solely on the filmmaker’s reputation. For instance, every festival wants the next Wong Kar-wai film (assuming he ever finishes it), and you would probably accept it sight unseen. More often the programmer catches the film at another festival, or in a private screening, or in a privately circulated video copy. That first viewing might be on any format. If the filmmaker submits the work, it will typically show up on a DVD copy, called a “screener.” Some festivals prefer the film to be uploaded to the site Withoutabox. The selection committee watches the submission to make an initial decision about the work.

Members of the press who attend a festival can usually get a look at some of the films via screeners. Often local critics watch screeners, especially if they have to write a review in advance of the festival and they’ve missed a press screening. Visiting programmers also borrow screeners from the festival because they usually can’t see all the films they might want to.

The problem is that screeners tend to be of wretched quality. Burned to DVD-R, sometimes from a VHS tape, and often in the wrong ratio or anamorphically squeezed, they are usually garnished with a more or less prominent watermark, either a “property of” one or simply a timecode readout chattering away. I can’t imagine claiming to have seen the movie after watching the typical screener. Kristin and I have used them to pull frames for our blog entries when we visit festivals, but only after we watch the films in projection.

Screeners look shabby by design. Anything approaching the finished film in image quality will be pirated, and the watermark announces that the dub you bought from the blanket on the street is stolen. I have seen a screener assigned to a particular person, his name as a caption throughout, so the distributor will know whom to pursue if it’s leaked.

Screeners made it much easier for filmmakers to afford to submit work to many festivals; imagine what costs were like in the days before videotape, when films were sent out on prints. But the emergence of screeners, I think, cheapened the film. VHS tape and many commercial DVDs make movies look ugly, but DVD screeners are far worse. Nonetheless, they are a fixture of the festival scene. As with so much about digital video, we can’t go back.

Digitalis

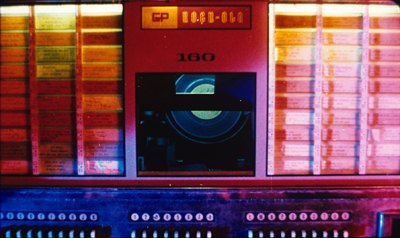

Sony HDW-D1800 HDCam deck. List price: $45,045.

Screeners are watched mostly behind the scene, treated as tools for programmers and critics. What about the things the audience sees?

For commercial projection in your local ‘plex, Hollywood companies realized that a proliferation of digital standards was bad for business. So they set up the Digital Cinema Initiative, which established specifications for the Digital Cinema Package—the ensemble of files packed onto that matte silver brick that is replacing traditional film rolled up on reels. The DCP files are encrypted and opened up with passkeys that are supplied separately. The DCP plays 2K or 4K digital video on the two standard projection systems, the DLP one established by Texas Instruments and the SXRD one established by Sony. It’s Microsoft vs. Apple all over again: the DLP format is licensed to several projector manufacturers (Christie, NEC, Barco) but the Sony format is used only on Sony machines.

Besides the DCP, there are many other digital formats for displaying moving images. Erik Gunneson, a filmmaker and teacher here at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, ran through some of the most common ones with me. They’re distinguished by many factors, but two common measures are resolution and compression. The more lines, the higher the resolution; the less compression, the better the image (although some compression is inevitable in any digital video projection.) Many of these are capture formats—that is, means of recording—that are also used for playback.

The earliest to emerge were the DV formats, all consumer/ prosumer platforms. They use “standard definition” video codecs, as opposed to High Definition ones. There’s a bewildering number of DV cameras and playback devices, because Sony and Panasonic developed different improvements on the basic standards (720 x 480 resolution). The most common versions, Mini DV and DV Cam, use tape for capture. They are fading out in independent filmmaking, but some festivals still screen in these formats.

Home viewers are probably most familiar with the DVD, which in the NTSC standard uses MPEG-2 video compression at 720 x 480 resolution. On a large screen, your typical DVD is unsightly. Blu-ray discs, of course, look better, partly because of their higher definition (as high as 1920 x 1080 resolution).

At the professional level, you have several options, mostly provided by Sony: Betacam SP, an analog format, and Digital Betacam, known as DigiBeta. They use tape, not hard drives, to record image and sound. But they’re falling into disuse now because of the rise of HDCam. It can use either tape or optical drives as recording media. HDCam playback can through up-sampling yield standard HD images of 1920 x 1080 pixels, and this makes it a popular option for independent filmmakers. PBS documentaries are often shot on HDCam.

There’s also HDCam SR, which yields, as they say, “native” 1920 x 1080 resolution and audio features. The SR format was initially designed for high-end special effects (bluescreen/ greenscreen) and became allied with Panavision in the creation of the Genesis camera. SR is sometimes used for television series. As you’d expect from a studio-based format, it’s expensive. According to Sony, an HDCam SR system runs about $230,000, and a 124-minute blank cassette (the same engineering as the old Sony Beta cassette) costs about $424.

Many of these formats come in various flavors: PAL or NTSC, anamorphic or unsqueezed, progressive or interlaced, recent upgrade or older specs, settings for various frame rates, and on and on. And there are still other recording and playback formats, such as HDV, DVCPro, and D5 HD . When talkies came in, maybe there were as many competing sound systems floating around alongside the two studio standards. But back then, there weren’t film festivals.

Format flare-ups

Sony J30SDI Compact Betacam Player; plays Betacam, Digital Betacam, Beta SP et al. Price: $21,000.

You the programmer have accepted a digital film for your festival. When it arrives to be shown, what format will it be on? Viewers used to home formats may expect that they’ll watch it on DVD or Blu-ray. But DVD isn’t usually suitable for projection to large audiences. Professionally produced Blu-ray discs are feasible for some public showings, but home-made Blu-rays burned by filmmakers on their own computers are notoriously unreliable. They’re likely to freeze up during projection. (This is one reason that many festivals insist that filmmakers not submit work on Blu-ray; DVD remains less unstable.) And good as Blu-ray looks on your home monitor, it’s inferior to the best professional projection formats.

So a higher-end playback is needed for most festival exhibition. Usually filmmakers say that they’d like the film screened on the format it was shot on, but this isn’t always possible. Remember that festivals move into existing venues, either multiplexes or arthouse theatres. What you can show will be constrained by what equipment is already in the booths, or what can be rented or purchased, then squeezed in for the occasion.

To keep things manageable, festivals have to restrict what exhibition formats they will use. Here are the formats listed in the submission requirements of some major festivals:

Telluride: Only 35mm or DigiBeta.

Seattle: 35mm, 16mm, or HDCam.

Toronto: 35mm, DCP, or HDCam.

Sundance (as of 2010): 35mm, 16mm, HDCam (NTSC 2), or HDCam (PAL 3).

Ann Arbor: 35mm, 16mm, Mini DV, or Beta SP.

Los Angeles: 35mm, 16mm, DCP, HDCam, DigiBeta anamorphic.

Rotterdam: 35mm, 16mm, Betacam SP (PAL), DigiBeta (PAL), or DVCam.

Filmmakers who want to submit a digital movie to lots of festivals will sooner or later have to convert the original files to another format. This process is expensive, and low-budget filmmakers may be tempted to try it at home, with dire results. If the filmmaker’s conversion turns out to be unplayable, the festival may have to try converting the movie itself or revert to the film’s original platform, which means bringing in other playback equipment.

Alexandra Cantin, Print Traffic Manager of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, notes:

Festivals have always been the bridge from the traditional to the latest, greatest technology and everything in between. Whatever the filmmaker could afford to finish on is what we have to work with. At times I have managed as many as 13 formats.

Worse, for any specific screening there may be several formats in play. The festival trailer-and-sponsor reel is unlikely to be on film these days, more likely on Blu-ray or HDCam. The feature may be accompanied by a short, which can be on any number of formats. A program of short films presents its own problems, since they may come in a bevy of formats.

Moreover, recall the central situation of festival screenings—many different movies played in a few venues continually. Let’s say that a given screen is used for five movies in a day, at 10 AM, 1 PM, 4 PM, 7 PM, and 10 PM. The schedule leaves very little time, at most half an hour, to test how a given film will play before its show starts. Of course, the film can be previewed days or weeks ahead of the screening—if it arrives in plenty of time. (Most don’t.) So projectionists, programmers, and technical staff are constantly juggling time slots, formats, and different auditoriums. Can we play this HDCam copy of Dark Bohemian Days on Screen 1? No, because the HDCam deck is only in Theatre 2 and Theatre 4. But Bohemian Days is over two hours long, and all the other long films are in 2 and 4 so we don’t have a slot available. We could move Dad Was a Transvestite, which is on DigiBeta, to a smaller screen, but we expect a big crowd for that, and we’d shut people out, and anyhow Screen 1 won’t have DigiBeta playback . . . .

Moreover, most festivals want to be flexible—adding screenings of popular titles, or substituting a film when another doesn’t arrive in time. Multiple formats make on-the-fly adjustments more difficult.

When you reflect on all the permutations of schedule, equipment, venues, formats, and staff assignments, it’s rather miraculous that most festival screenings start on time and are well-projected.

Then there’s DCP.

DCP = Damn Cinephile Problems?

The Digital Cinema Package and its shipping case.

2011 has been the first big testing period for digital cinema at the major festivals. Several screenings have been delayed (by hours) or canceled. Occasionally digital copies were replaced by DVDs or 35mm prints (coming to be known as “analog backups”). In correspondence with several programmers and consultants, I’ve garnered a sample of eye-opening reasons for the breakdowns. Most have to do with the Digital Cinema Package.

The DCP, that gleaming brick drive seen above, is part of a larger digital environment. There’s the projector. There’s the server in the booth that stores the film, along with trailers and other material, and allows the operator to build playlists for the show. There’s the Theatre Management System, an umbrella device that coordinates all the servers and projectors, along with lighting, curtains, and other aspects of presentation that can be automated. But all this hardware and software is inert without the Key Delivery Message, or KDM. (Get ready: We are living in the Age of Acronyms.)

The Key Delivery Message is a security device. It’s a very long alphanumeric string, usually sent to the exhibitor by email, that opens the DCP’s files. It will work for only one movie on one server for a specified time period. If you want to play the same movie on a different server or projector, you need a second KDM. The KDM is tailored to the projector or server’s media block, and it won’t work if it can’t “talk to” that block. The arrangement keeps the DCP from playing on equipment that isn’t certified as compliant with the standards of the Digital Cinema Initiative created by the Hollywood studios. The KDM also detects any tampering; if someone has tried to access the files impermissibly, the DCP won’t play.

Clearly the KDM, like the DCP, is optimized for commercial theatres playing the same movie on the same screen for many days or weeks. In a festival, it creates headaches because the staff are cycling many titles through a single screen, or shifting one title from screen to screen.

Nonetheless, festivals must accept some DCPs. Today’s big-name “commercial arthouse” films supported by major overseas companies and US distributors are likely to show up on DCP–films like Melancholia, Certified Copy, and similar high-end titles. These titles are the backbone of festival ticket sales.

What could possibly go wrong?

Projector problems: At one festival, the only DCP-capable projector broke down and had to be replaced by one that was flown in. An entirely new set of KDMs had to be generated.

Server/ projector mismatches: Vancouver International Film Festival Director Alan Franey explains what happened last year.

Christie Digital provided us with their best new projectors and Dolby provided us with their best new servers. Both Christie (in Ontario) and Dolby (in California) are sponsors of VIFF and give full attention to quality control and technical support. The problem was that the stuff was so new and improved that it didn’t work, and no one knew why. . . . Since these two pieces of equipment had never interfaced before, there was unanticipated software incommunicability.

Alan indicates that once the software was amended, projector and server could communicate, but “it took expert technicians 48 hours (without much sleep) to figure that out.”

DCP damage: Like all computer files, a DCP can be corrupted. Often a duplicate DCP is sent as a backup. But sometimes not, or sometimes that’s corrupted too.

Ingestion digestion: A booth’s server has only a certain capacity, say seven hours. Alan Franey: “Assayas’ Carlos barely fit.”

Under festival conditions DCPs are constantly being loaded into the server (“ingested”) and extracted from it (“dumped”). For a feature-length movie, this can take an hour or more. Alexandra:

Ingesting, dumping, and reingesting are common. We are showing so many titles that server space becomes an issue.

KDM time intervals: The permissible play period may be too confining. Shelly Kraicer, a Chinese cinema expert who has programmed at many festivals, points out:

A screening could be aborted because of time-zone issues. A KDM has a start and stop date. If it too closely fits the screening dates (and that seems like what’s been happening), then a twelve-hour time zone offset (say, Asia to East Coast USA) can put the KDM off by one day, and it could refuse to play.

KDM/ DCP matchups: Even multiplexes are finding problems getting the KDM to open the DCP, with projectionists having to phone companies to walk through the security steps. The problems are exacerbated with foreign titles on DCP. Alexandra again:

What if the hard drive is coming from Poland and the KDM is being issued from a French lab that is closed for two weeks over Christmas? And the filmmaker is on location in the Philippines? This is a current real scenario.

Inflexibility of programming: Obviously DCP titles can only be screened in houses equipped with compliant projectors. Most booths in most festivals don’t have such projectors and may not be getting them soon. Whereas 35mm prints can be lugged from spot to spot, a given DCP with its attendant KDM is locked to one house.

Shelly notes that switching venues or adding showings is difficult:

If you need to move a DCP film from Screen A to Screen B tomorrow, you need to urgently request from the distributor that a new KDM be generated and sent and tested in time. This often doesn’t work. (Try doing it over a weekend.)

Alexandra agrees:

If one wants to change venues in response to audience demand, that is usually not possible unless the DCP is unencrypted, there’s sufficient time for ingestion, and if there’s a KDM that allows for it.

You can argue that these are teething pains. Venues will acquire servers and projectors, staff will become adroit at handling DCPs and KDMs, software will get standardized and hardware will get more reliable. Then things will run smoothly. And of course, 35mm was never free of snafus—bad splices, wrong aspect ratios, reels run out of order.

Still, the new problems are of a different kind. 35mm was stable as a standardized format, however bollixed it could become in execution. Since about 1930, you bought a projector and you threaded the film into it and set your sound and ran your show. Now we’re in an environment in which nothing is stable in a long-range time scheme. Alan Franey suggests why:

Everything we know about the constant rapid evolution of computers seems to suggest that we’re in for rapid obsolescence, constant upgrades, and at showcases like VIFF, a lot of on-site beta testing. . . . We have every reason to fear a five-year replacement cycle. Robust, no; expensive, yes.

Doubtless festival directors and their teams will come up with something. Perhaps a less stringently secured format could replace DCP for festivals and arthouses, or films could be stored in the cloud. For non-DCP programs, perhaps filmmakers can project straight from their laptops. In all cases, accessible backups need to be available as well. In the meantime, Pandora’s box has opened wide for the festival circuit.

Long live the analog backup

Can a festival simply go its own way—refusing arcane digital formats, avoiding DCP, and showing good old 35mm? No. The big festivals will have to follow the lead of Cannes, which screened 60% of its titles last year in DCP. The midsize and small festivals are already disadvantaged. Distributors and producers want their films to premiere at the highest-tier festivals, and the few 35mm prints that exist are reserved for the bigger events.

As a result, programmers who want desirable titles are being nudged—or shoved—to digital. Peter Porter, professor and Director of the Spokane International Film Festival, observes:

While we will always hear “We can’t premiere with you,” more often have I been hearing, “If you will screen non-35, you can have the title.” In any case, if I insisted on 35mm prints, I would have no film festival. Of the forty or so features that we will screen, my guess is that fewer than ten will even be available on 35mm.

At Vancouver this year, Kristin and I looked forward to seeing Kore-eda Hirokazu’s I Wish. But when we learned from the catalog that it was screening digitally, snobby purists that we are, we thought we’d wait for a chance to see a 35mm copy elsewhere. Yet our friends who went to the show came back delighted: A 35mm print was shown instead, with electronic subtitles. Fortunately, Kristin and I were able to catch the second screening, the same very pretty 35mm print.

If the VIFF team had had to switch formats at the last minute, it was surely tough; but the smooth-running screening of I Wish made me think: This could be the only time I’ll ever see it on film.

For the same reason, I went to our Cinematheque screening of Play Time in mid-December. This film has been central to the way I think about cinema since my first encounter with it in the summer of 1973. It’s an old friend. Maybe some day that well-traveled Janus print will serve as a backup for a digital screening. I might attend, with fingers crossed that the old reliable will be pressed back into service.

This entry is one in a series about the conversion of film to digital-based systems. Earlier entries are here and here.

Thanks very much to Alexandra Cantin, Alan Franey, Erik Gunneson, Jim Healy, Shelly Kraicer, and Pete Porter for sharing their knowledge with me. Thanks to Alissa Simon, programmer of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, as well. I’m also grateful to James Bond of Full Aperture Systems for a fact-filled lunch.

PS 5 January: Mark Peranson, Programming Associate at the Vancouver International Film Festival, writes to say that both DigiBeta and 35mm were options for I Wish. The staff were hopeful of getting a film print, but they were prepared to show digitally if the 35 didn’t come through. Thanks to Mark for correcting the first version of the entry, which claimed erroneously that a DCP had failed. Serves me right for believing gossip.

PPS 7 January: Thanks to Antti Alanen for reminding me to mention 4K as another format played in DCP. By the way, his Film Diary is always worth visiting; the latest entry surveys programs currently playing at major film archives.

PPPS 31 January: David Dinnell, Program Director of the Ann Arbor Film Festival writes:

I thought it might be of interest to you that the Ann Arbor Film Festival hasn’t exhibited any works on tape for the past four years. We have moved to a digital file playback system, which has been able to accommodate the various SD, HD and compression codecs independent filmmakers use. I think we are one of the first festivals to go this route.

Thanks to David for the information.

PPPPS 1 February 2012: Thanks to Sven Jense of Rotterdam for pointing out that I should stress that the DCP is the collection of files on the hard drive, not the hard drive itself. In practice, people speak of both as the DCP, the way that speaking of a package of anything refers both to the contents and the container.

Jacques Tati explains Play Time in a prologue included with the film during its New York release in 1973. From a 35mm print, scanned at 2000dpi.

Down in front! Notes from the Raccoon Lodge

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

There is one hypothesis that I find interesting because it is so minimal, yet sufficient. This is that nobody cares where he sits, as long as it’s not in the very front.

—Thomas Schelling, 1978

DB here:

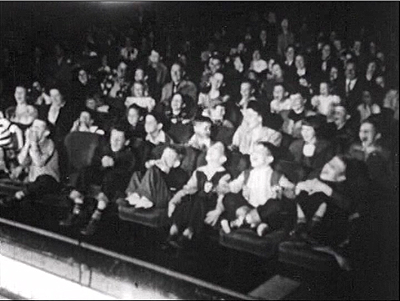

Where do you like to sit in a movie theatre? If you’re like most people, you sit fairly far back, maybe all the way in the back row.

Sitting in the rear is the default for public gatherings, it seems. Thomas Schelling famously offered seven hypotheses about why people don’t fill up the front of an auditorium as fast as they fill up the back. His reflections were occasioned by his giving a lecture to 800 people, none of whom would sit in the first dozen rows. I know the feeling, though on a smaller scale. Seeing all your audience huddled so far away, you suspect you have cooties.

Schelling didn’t, so far as I can tell, offer a definitive answer, and his charitable reflections on people’s motives don’t keep me from finding the migration to the rear disquieting. In lectures, those distant auditors send off an air of foreboding. They seem poised to flee at the moment the talk reveals its fully catastrophic dimensions.

There’s a debate about whether students who sit in the rear get worse grades than those who sit close. (See below.) Speaking from experience, I’d be inclined to say that professors tend to give better grades to students sitting close because those distant, blurred ranks tend to give off an aura of desperate yearning to be anywhere but there. The folks up front at least seem to be trying to be part of things. The back-row brigade have not learned the great lesson of social life: Feign interest.

As this lead-in suggests, I’m a front-zone sitter. But that predilection comes at a cost.

Rebel without a Cause.

For lectures I always try to get a front-row seat, close to the speaker if possible, or centered if there’s to be a big visual presentation. This vantage point is great. If there’s flop sweat, you see it. If not, you get to enjoy consummate performance up close. I’ve sat in the front row for fine speakers like Chomsky, Pinker, and Bruner (to stay just with the Boston brain trust).

When a filmmaker does a Q & A, the front row is a must: you get a good chance at an autograph. The only time I regretted my prime front seat for a live event was for a concert—a John Zorn one. Within five minutes I expected my eardrums to bleed. After that overture I don’t think I heard anything else.

I saw back-row bias in the movies demonstrated dramatically in Madrid, where Tom Gunning and I went to a movie together. I forget the name of the theatre, but the film was Welcome to Veraz (1991), a Euroduction featuring, inevitably, Richard Bohringer and, less predictably, Kirk Douglas. Once we got inside, we found that our tickets were for specific seats. The cashier had assigned us, and all other patrons, to the same row—in the back, naturally. The absurdity of a dozen of us sitting side by side in a vast theatre was lost on the staff. Tom and I moved to the front, but everybody else piously stayed in the same pew.

You can study a less extreme case in graphic form in those remaining venues, mostly European and Asian, that still ask you to choose your seat on a chart. A glance shows you that everyone has piled into retreat mode, leaving lots of nice seats for you. Problem is, those overhead diagrams of the venue aren’t to scale, and so you don’t really know how close you are to the screen when you’re picking your seat.

When you were little, you didn’t mind sitting up by the screen. You sometimes fought to do it. But as we age, we seem to gravitate toward the rear. We’re even told that we should sit a prescribed distance back, usually the dead center of the auditorium. A distance of 2-3 times the screen height is a common recommendation. But Kristin and I are front-zone people. Speaking for myself, I like scanning the frame in great saccadic sweeps and even sometimes turning my head to follow the action. CinemaScope and Cinerama give your eyeballs a real workout.

I know that most people find this sheer madness. When the picture comes looming up, you do feel a little disconcerted and overwhelmed. But I find that I adapt in a minute or two. Even the keystoned angle isn’t a problem, partly because of our old friend perceptual constancy.

Note that I said front-zone. Not every theatre favors front-row sitting. Kristin and I once went to a screening of An Autumn Afternoon in a tiny Parisian house, one of those that seem to have been carved out of a loading dock. We sat in the front row, but that was a mistake. We could put our feet up against the wall housing the screen, and we reckon we watched the movie at something like a 45-degree angle.

Something a little more peculiar happened when we went to a Fan Preview of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Firmly ensconced front and center, we were packed in by comic geeks, nerds, dorks, wonks and other damned souls, all determined to enjoy this movie. So we had the strange experience of hearing a line of dialogue and then, because its eloquence had a rich bouquet, hearing yelps of appreciation rolling back behind us, as row after row (a) heard it, (b) laughed, and (c) did an instant commentary on it. I can’t judge this movie objectively to this day.

So sometimes the front row isn’t ideal. Through experience, we know our local venues and favorite festival sites. In some theatres, such as most of our local Sundance screens, we sit 2-5 rows back, with C being a common choice. Still, the ticket seller usually does a double take and reminds us where the screen is. Then we get a shrug and something on the order of “Well, you won’t be crowded down there.”

Bologna Cinema Ritrovato 2008: Olaf Möller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, Kristin Thompson.

But in many venues the front row is perfect. Sitting there is hard-core moviegoing. I started aiming for it about forty years ago, when I began taking notes on every film I saw. If you sit too far back, how can you see your pad? You can’t be one of those idiots brandishing a lightbulb pen (even though I have some of those). The screen casts a little light that makes scribbling easier.

But even those who don’t write notes see the advantage of the front row. Nobody’s head looms in front of you. You’re less disturbed by latecomers. You have more leg room, and it’s easier to stretch out for a snooze. And should you wish to leave, the front row is the only one that lets you sneak out easily from any seat.

That last advantage, I should mention, can lead to trouble. Once at VIFF I was firmly planted in the front row, nose in book, as the auditorium filled. But I began to realize that these didn’t seem to be my tribe. There were more beards, nicer clothes, better hygiene, more sensitive faces. The place filled, and someone came forward to thank the sponsors for bringing a film about the efforts to save remote wetlands. I was in the wrong auditorium. To glares and mocking comments I slunk out in search of some obscure art movie I’ve forgotten.

Like everything else you do, front-row sitting sends a message. What message? For one thing, that signal of interest I mentioned in my classroom example. Somehow the front-row sitter seems to be more engaged, more eager to be swept up in the magic. You probably know the urban legend that the Cahiers du cinéma writers sat devoutly in the front row at Langlois’ Cinémathèque. We belong to a noble tradition, and we flaunt it. Chevaliers of cinéphilie, we risk eyestrain, neckache, back pain, and leg cramps for the art of cinema, or so we like to think.

Speaking of the Cinémathèque, back in 1970 I went to the Chaillot venue for a screening of Liebelei, to be attended by Luise Ullrich, one of the principal players. The place was full, but I had nabbed a nice spot up front. Before the film started, though, a Cinémathèque functionary started going along the front row asking every patron there a question. Everyone asked said no. I couldn’t hear the question at a distance, and perhaps might not have understood it if I had. So when the staff member came to me, I scarcely let him finish before declining. If non was good enough for other front-row denizens, it was good enough for me.

After the lights came down, Henri Langlois stepped onstage with Mme Ulrich. After a brief introduction, they descended. Only then did two people on the aisle surrender their seats for them. Then I realized all the French guys sharing the front row with me wouldn’t give up their seats even for the guest and the boss of it all. You see why I say front-row people are hard-core?

Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

I must report, however, that front-row sitting sends other signals too. Theatres in film archives have their regulars, and these folks, like me, believe that there’s only one good seat in any theatre, and they must occupy it. Fortunately, they mostly don’t agree on what that seat is. I’m always befuddled when the first person in the queue makes a dive for a seat far back and in the corner.

Alas, though, so many regulars have aimed at my target that every cinematheque has a coterie of front-row fans. And they’re perceived as, well, strange. I remember going to London’s National Film Theatre during a visit and getting in early enough to nab a prime front seat. Many regulars shuffled in to join me, and one seemed a bit miffed after the rank had filled. My neighbor told me apologetically that I was sitting in his friend’s seat. Of course I moved. Local loyalists have privileges. On another occasion a BFI staff member said that she worried that one of her friends might become “one of those sad front-row people at the NFT.” They didn’t seem unusually unhappy to me, but then they wouldn’t, for I am one of them.

My strangest contretemps with a front-row devotee came during a visit to the Munich archive. They were running Get Carter and I was the first entrant. I secured my front-row center post and settled down to read. (Front-row people show up early enough to finish substantial portions of Dostoevsky novels before the lights go down.) Suddenly an aged German lady, fortunately not Luise Ullrich, stood before me.

Seeing I was reading a book in English, she said, “Pardon me, you’re in my seat.”

I looked around and saw that we were the only people in the theatre.

“I always sit here,” she said. “I come every night.”

Nerdesse oblige. I relocated to the seat behind her. Moved by my gallantry, she twisted around to talk with me. I asked if she really came every night.

“Well, not every night. Not if they’re showing a Jap movie.” She looked severe. “I don’t like Japs.”

Comments about disloyalty to old friends leaped to my tongue, but I kept quiet.

Soon Get Carter started. The old bat immediately fell asleep.

She slept through the whole movie. I wanted to knock her upside the head. When I left, she was still out, snoring in my seat.

There are other drawbacks to the avant-garde spot in the movie theatre. Most people are bothered by handheld shots and 3D if they sit close, but I don’t find myself affected. Granted, I probably miss some of the surround-sound effects, which are apparently designed for a sweet spot far behind my territory. If it’s any compensation, the left/ right channels are really vivid for me.

The biggest drawback, though, is that you don’t have eyes in the back of your head. During Q & A sessions, you can’t track the conversation without twisting around in your seat. So I sit there as if I were listening to the radio. Worse, sitting close can render you oblivious to things going on behind you. If a fistfight broke out in that heavily populated rear section, you’d be in a poor position to watch it. Occasionally being in the front row makes me miss an outburst that was probably pretty entertaining but leaves me feeling like the guy in Pompeii who wondered why everybody was running past him just before a couple of tons of ash buried him.

A Drunkard’s Reformation (1909).

On the obliviousness scale, my most memorable front-row experience came during another overseas festival. A visiting actress of consequence had directed some feature-length films, and the festival had arranged a screening of one. This entailed setting up a video projector and preparing, far in advance, electronic subtitles in the local language. When the director saw me planted in the pole position she said, “You shouldn’t sit so close. This movie is like Dancer in the Dark.”

No problem, I assured her; I’d seen that from the front row too.

No one joined me in the front. But there was a sizeable audience. Once people had settled down, her introduction explained five things, each one adding to a litany of doom.

(1) She played the protagonist.

(2) The film was improvised.

(3) It was shot handheld.

(4) The actors were her friends.

(5) It was a satire on the superficiality of Los Angeles life.

She wished us a good screening and said she’d see us afterward for a discussion.

The film was as dire as I’d feared. When the lights came up I noticed that nobody was setting up the microphone on stage. I turned around. The technicians were putting away the projection equipment. I was the only viewer who’d hung on to the end. Needless to say, there was no auteur and no Q & A.

Despite all the drawbacks of front-zone sitting, I feel vindicated by a recent revelation. A review quotes James Wolcott’s acount of Pauline Kael’s preferred viewing station.

We take up mortar position in the back row. Pauline nearly always sits in the back, often right beneath the projectionist’s portholes, flanked by fellow critics on her squad. . . . (The auteurists — those ardent members of Andrew Sarris’s Raccoon Lodge — tended to huddle closer to the screen, as if to meld mind and image into a blissful, shimmering mirage of Kim Novak with her lips parted.)

I rest my case.

Thomas Schelling’s reflections on lecture-hall seating open his classic Micromotives and Macrobehavior. Among his more entertaining speculations on why people sit in the back is this one:

A fourth possibility is that everybody likes to watch the audience come in, as people do at weddings.

For some research on whether students sitting up front get higher grades, go here (abstracts only) and here. Jonathan Cohen provides a nice analysis of the research on perceptual constancy here. 3D has rekindled debates about where to sit; for one exchange among cinematographers, go here.

Le Pied qui étreint is discussed in more detail here.

Joe Dante at University of Wisconsin–Madison, November 2011. Photo by Jeff Kuykendall. For more on Dante’s visit, go to this earlier entry and to Jeff’s coverage here.

PS 23 January 2012: Please note that another couple likes to sit in the front row (from here).

PLANET HONG KONG: One more visit

Hong Kong, Central, April 2008.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans and then by a photo gallery of directors. Today’s installment is the last. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D, which will appear later this week.

Since the 1980s, the film festival circuit has become the only distribution system to rival Hollywood’s global reach. A big-name festival publicizes a film, some high-end critics at the festival write reviews, then once the film opens in a region or country, critics at large review it. As smaller festivals pick up films from the bigger ones, until eventually films make their way to small cities around the world. This process is parallel to the one that the studios orchestrate, though they have more centralized control. Video distribution, the circulation of DVD screeners, and Internet reviewing complicate this picture, but I don’t think they change the essential role of the festival network.

Just as film scholars have started to pay attention to fandom (see this post), they’ve started to ask research questions about festivals. As very few films from overseas find their way to U. S. screens, scholars keen on current cinema have realized that they need to visit festivals. It’s like scholars of painting traveling to exhibitions and gallery shows, or opera aficionados attending premieres at Bayreuth and La Scala. And film scholars of certain genres or periods have realized that they can do on-the-fly research by visiting historically oriented festivals like Pordenone and Bologna.

These days I see more of my colleagues at various festivals. In particular there’s the peripatetic Bérénice Reynaud, an early example of the multitasker (critic, programmer, professor, fan). On the same circuit I meet Virginia Wright Wexman, Peter Rist, Mike Walsh, Jim Udden, Gary Bettinson, and many other profs. So I’m starting to think that festivals are giving academic film studies a fresh charge of energy. Reciprocally, the events at Pordenone and Bologna, which began as cinephile events, have invited academic researchers to help program them and write for their publications. In sum, festivals are now a vigorous workspace for not just screenings and critical write-ups but discussions about ideas that would normally haunt the groves (or is it grooves?) of academe.

Saturation booking

Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. Hong Kong, 2000.

I had dropped in at screenings at the New York and London film festivals in the 1970s and 1980s, and I had steadily attended the summer Cinédécouvertes series in Brussels. But I had never “done” a festival intensively until I went to Hong Kong in the spring of 1995. There I saw films that still stay with me: Through the Olive Trees, Postman, In the Heat of the Sun, A Borrowed Life, Smoking/ No Smoking, Quiet Days of the Firemen, Taebek Mountains, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Whispering Pages, and Clean, Shaven. (My one big miss was Sátántangó; I had to wait years to catch up with that.) Who says the 1990s were a meager decade? Can any festival today come up with a menu like this?

I had gone, as I explain in the Preface to Planet Hong Kong, mainly to check on local cinema. The “Hong Kong Panorama” surveying 1994 releases yielded a bumper crop, including some titles I’d seen only on laserdisc (Chungking Express, Ashes of Time) and others that were revelations. Above all, there was a retrospective—an entire festival in itself, really—dedicated to early Chinese and Hong Kong cinema. They swept over me in a heaving wave: Love and Duty (1932), The Eight Hundred Heroes (1938), Boundless Future (1941), and many others, along with postwar Hong Kong classics like Where Is My Darling? (1947), Song of a Songstress (1948), The Kid (1950), with Bruce Lee, and on and on. The series was capped by stunning restored Technicolor prints of The Orphan (1960), also with Bruce, and General Kwan Seduced by Due Sim under Moonlight (1956). Some of these had circulated on poor VHS copies, but most were, and still are, unknown in the West.

I had picked the perfect year to come to the festival. Looking back at the notes I scribbled in the dark, I realize that over three weeks I got a crash course in Chinese film history. In any given day I was given more to think about, and certainly more to feel about, than I got from almost any academic conference.

For those of us interested in non-Hollywood cinema, festival programmers and critics are central gatekeepers. They scout the ridge and scan the horizon, and around the campfire they teach us film lore. They’ve built up fingertip knowledge about movies, moviemakers, distribution patterns, sales agents, theatre circuits—in sum, the workings of world film culture. The best of these gatekeepers are intellectuals, ready to search out something stimulating in even the most marginal film. They have honed their senses to detect qualities that could provoke an audience or yield a lively Q & A or a piquant catalogue entry or a solid review. Out of pure selfishness, I wish I could download the neural storage files of Alissa Simon, Richard Peña, Tony Rayns, Cameron Bailey, and their peers. Alas, there is no app for that.

In Hong Kong I met Li Cheuk-to, Jacob Wong, Freddie Wong, and many other programmers, along with Athena Tsui and Shu Kei. What made my experience that spring of 1995 so thrilling were their months of patient planning and sleepless nights behind the scenes—finding the prints, arranging for them, writing catalogue copy and, not least, assembling a massive reference work like Early Images of Hong Kong & China, one of the precious books the festival managed to turn out every year to document the local cinema.

Many programmers are also critics, and such was the case in Hong Kong. When I arrived, Cheuk-to and his colleagues had just formed the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, and I was invited to their first awards ceremony. They were mostly young, and after the awards were handed out I was invited out to dinner with several of them. It was then I realized that here was a local film culture in which criticism mattered. Hong Kong was small enough for critics to band together to debate their cinema. Soon another critics’ group was founded, and the debates spread. I started to understand that if one were to study a film culture, one would have to grasp the dynamics of taste among schools of critics and between critics and their audiences. I made an effort to describe this dynamic in the second chapter of Planet Hong Kong.

It’s not just that that book had its origins in that first visit. And it’s not just that the newest edition is the result of my attending the festival for the last fifteen years. More important, my ideas about film and about the world changed when I met critics, programmers, and other academics in Hong Kong. Immersion in one of the world’s most fascinating cities had something to do with it too.

Favorites, for now

As Tears Go By (1988).

In my first entry in this hurriedly posted series, I listed around 25 Hong Kong films that most aficionados consider of major importance—historical, artistic, cultural, or all three. In the days since, I’ve mentioned several other films that you can check into. Here, as an envoi to this yakathon, are a few more movies that I’ve repeatedly enjoyed, and that I’ve sometimes talked about in PHK 2. They’re grouped in very loose categories.

Lesser-known items from major directors. Once a Thief is a good example. Sandwiched between Woo’s official classics is this good-natured, somewhat silly action comedy about art thieves, romance, and parenthood. Lifeline is one of my favorite Johnnie To Kei-fung films—not as formally audacious as his later masterpieces, but containing one of cinema’s great action sequences involving a fire that seems as unstoppable as a waterfall, with the bonus of a throat-catching epilogue. Ann Hui On-wah’s Summer Snow, about a busy career woman who must treat her Alzheimer’s-affected father, glows with the intimate realism and understated sentiment that inform her more recent The Way We Are.

Everybody knows some works by Wong Kar-wai, but I think his later accomplishments have overshadowed his debut, As Tears Go By, a prototype of the arty gangster movie. Drenched in romanticism, it has one of the great music montages in Hong Kong film and a finale that you feel lifting from genre formula to pictorial poetry. With Johnnie To as well, even offbeat items like Throw Down are getting well-known, but I’d like to make a pitch for the New Year’s mahjong comedy Fat Choi Spirit. It has some of the 1980s nuttiness; the laughs start at the DVD menu.

Tsui Hark has produced so many films that have been fan favorites–Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, and Swordsman III: The East Is Red–that you can’t expect anything worthy to be overlooked. And yet not enough people have seen the bouncy Shanghai Blues, with moments of musical rapture, and The Chinese Feast, with all his faults and virtues bundled into a celebration of cooking and eating. There’s also The Blade, a convulsive revenge saga that seems to me one of the best movies made anywhere in the 1990s. After it’s over, you’re not sure what hit you.

Drama, comedy, dramedy. Any reader of PHK knows my fondness for the gender-bending romance Peter Chan Ho-sun’s He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, a lovely integration of musical, coming-of-age story, and satire of sex roles. But my favorite Michael Hui film, Chicken and Duck Talk didn’t feature in the first edition because I couldn’t get my hands on a print to illustrate it. Tracing the rivalry between a scruffy duck restaurant and a Japanese knockoff of Colonel Sanders, it yields many hilarious sequences, perhaps most notably Hui’s efforts to conceal a plague of rats from health inspectors.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

My associates sigh when I mention Wong Jing. What can I say? I find some of his films funny. Try Boys Are Easy, Tricky Master, and, probably my favorite, Whatever You Want. If you don’t like them, write my suggestion off as David in his Dotage. Speaking of silliness, I’m not over-fond of Stephen Chow, but All for the Winner, Flirting Scholar, From Beijing with Love, and A Chinese Odyssey are ingratiating enough. Square that I am, I like Shaolin Soccer too.

I’d add the medical melodrama C’est la Vie, Mon Cherie, the unpredictable cop stakeout movie Bullets over Summer, and the poignant Juliet in Love, about a triad’s attraction to a woman recovering from a mastectomy. Sylvia Chang Ai-chia’s quiet romantic dramas Tempting Heart and 20 30 40 are also rewarding. Patrick Tam Kar-ming’s films are still unjustly neglected, so anything might be considered obscure, but I was delighted when a passable DVD of My Heart Is that Eternal Rose was released. Here Tam lyricized the gangster movie; Wong Kar-wai took the next step.

For grotesque comedy, try You Shoot I Shoot, about a contract killer who adds value by having an aspiring director film the hits (complete with slo-mo) for the delectation of the client. Unclassifiable is The Inspector Wears Skirts II, a cop-training story that pits women recruits against dimwitted men. It includes a dance sequence displaying minimal skill and maximal cheerfulness.

Fight club: Of Chang Cheh’s vast output of martial-arts movies, I have a special affection for New One-Armed Swordsman, a spectacularly mounted action picture, and Crippled Avengers, in which “disabled” really does mean “differently abled.” For Lau Kar-leung, I especially admire Legendary Weapons of China, one of the strangest of his forays into the arcana of martial arts lore and Chinese history; Shaolin Challenges Ninja (aka Heroes of the East), a sort of Taming of the Shrew, but with throwing stars; and the harrowing Eight-Diagram Pole Fighter, something of a valedictory for the Shaolin tradition at Shaw Brothers. Both these directors made so many worthwhile films that you can spend a lot of agreeable time exploring their output.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

In the crime vein consider Kirk Wong’s hard-driving and pitiless Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop and Danny Lee’s Law with Two Phases (not a typo). Ringo Lam’s films are notably tougher and more tactile than those of his contemporaries; see his deromanticized classic City on Fire, the effort to out-Woo Woo that is Full Contact, and the lesser-known Full Alert. Eddie Fong Ling-Ching isn’t known for policiers, but Private Eye Blues was one of the films I enjoyed in the 1995 Panorama. His historical drama Kawashima Yoshiko is even more remarkable.

Connoisseurs know The Outlaw Brothers; one glimpse of the climax, in which a gunfight is interrupted by a hailstorm of poultry, usually convinces any viewer to take a closer look. I must add the below-the-radar ensembler Task Force, by John Woo protégé Patrick Leung Pak-kin. Gratifyingly untidy in skipping among the personal lives of a cop squad, it eventually focuses on the need to settle conflicts without violence—after, of course, supplying some snappy fight scenes of its own.

Post-handover take-outs. Most of the films I’ve mentioned are from the 1970s through the 1990s. But many worthy films have emerged in the 2000s. If they don’t always carry the effervescence of the earlier ones, many are solidly crafted. Some are discussed in Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and many more have received commentary on other websites (e.g., LoveHKFilm), so I’ll just mention a few that seem to me of more than transitory appeal.

Patrick Tam’s After This Our Exile is an unsentimental look at how an aggressive, heedless father must come to terms with his little boy. Needing You is a better-than-average office comedy, while Hooked on You is poignant in the gruff Hong Kong way, with a touching finale about the changes since 1997. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s action pictures usually deliver sturdy value in the old style. Try Connected, a remake of Cellular; New Police Story, with Jackie Chan as a cop coming to terms with age and failure in the face of nihilistic youth; and Invisible Target, which boasts an old-fashioned Hard Boiled demolition derby, with a police station ground zero this time. Horror fans already know how uneven HK films in that genre can be, but surely Fruit Chan Goh’s Dumplings is an admirably creepy achievement, and Soi Cheang Pou-soi did good work in the genre as well (Diamond Hill, Horror Hotline) before moving to the suspenseful Love Battlefield and the harsh action picture Dog Bite Dog.

Whew! After seven sword-like days, I’m running out of time, and I haven’t achieved a final victory. Want more dangerous encounters? Go to PHK or the Hong Kong Critics Society Award winnerss and start looking for your better tomorrow.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

Kristin and I discuss film festivals as an aspect of global film culture in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For detailed research into the festival scene, see Richard Porton, ed., Dekalog 3: On Film Festivals and several publications from St. Andrews University. The most recent volume, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, focuses on East Asian events.

P.S. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for a title correction, and Tim Youngs for a geographical one!

Photo: Joanna C. Lee, courtesy Ken Smith.

Vancouver: Final freeze-frames

DB here:

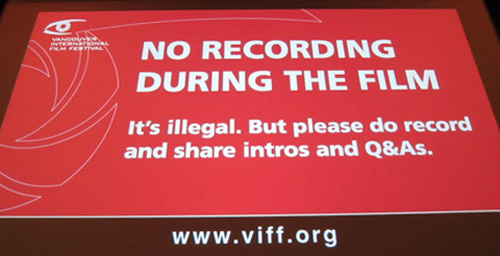

This slide, which appeared briefly before every screening at the Vancouver International Film Festival, epitomizes one of the event’s virtues: quiet sanity. Of course we must discourage people from recording the movie. But just as surely, we want people to photograph the filmmakers and record their comments and get the word out. Spreading the news benefits everybody, particularly the filmmakers.

Indeed, the whole VIFF clambake is run as efficiently as anyone can imagine. Want to get into a film? Very likely you will. A movie is getting buzz? Likely as not, extra screenings will be mounted. Annoyed by mobile devices in the throngs around you? House managers firmly ask people to shut them off. Now. Yet there’s nothing aggressive here. This is a city in which the buses preface the flashing notice “Out of Service” with an apologetic “Sorry.” A Manhattan bus would say, “You’re outta luck, pal.”

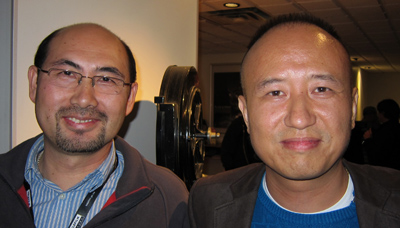

Now that Kristin and I are back, we know whom to thank: the organizers, the programmers, the office staff, and the inexhaustibly cheerful volunteers (700 strong). Below are Alan Franey, Festival Director, and PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager and Senior Programmer.

Come down for breakfast and you’re likely to run into Foreign Guest Coordinator Theresa Ho and Hospitality Suite Manager Eunhee Cha Brown. Dreyfus is usually not far away.

Then there’s the multi-talented Lillooet Fox, Food and Beverage Coordinator, waffle wrangler, and music supervisor for Amazon Falls, playing in the festival.

Ever notice how film people are always “on,” always subtly copping stances and looks from movies? Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers programmer, does his dressed-down version of Lars von Trier.

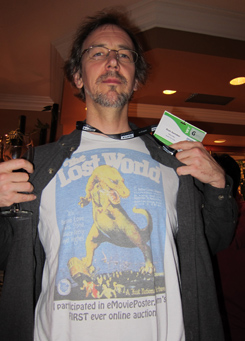

Speaking of T-shirts, nothing beats telling a story with your thorax. Consider Sean Axmaker (Parallax View) and Robert Koehler (Anaheim International Film Festival) and Raymond Phathanavirangoon (Hong Kong International Film Festival).

At happy hour, the waffles vanish and adult beverages come into their own. VIFF programmer and editor of Cinema Scope Mark Peranson hoists one with Variety critic (and University of Wisconsin alum) Rob Nelson.

Of course everyone mingles with filmmakers. Freddie Wong, director of The Drunkard, is reunited with Bérénice Reynaud, Cal Arts professor and author of a book on City of Sadness.

Tony Rayns, veteran Dragons and Tigers programmer, is flanked by Bong Joon-ho on the left, Denis Côté (Curling) across the table, and Mark Peranson on the right. Geoff Gardner and Jack Vermee are in the distance. Again, the cinephiles pay homage to a shot, in this case from Hong Sangsoo’s Oki’s Movie.

Jim Udden, another Badger and Professor at Gettysburg College (and author of a book on Hou Hsiao-hsien), talks Taiwanese film with director David Verbeek (R U There?).

Trustworthy translator Alex Fu and director Zhu Wen (Thomas Mao).

Takahashi Nazuki and Abe Saori celebrate after their screening of Icarus Under the Sun.

Meanwhile, Geoff Gardner (watch for his VIFF coverage in Urban Cinefile) finds that a rival venue has conjured up a star from another era.

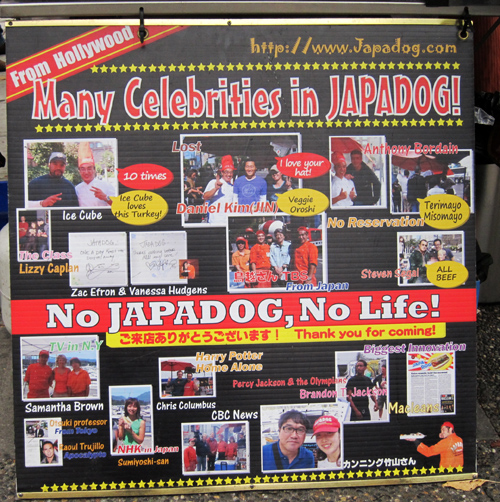

And although we left Vancouver all too soon, we’ll always have Japadog. Not everything in Vancouver is quiet sanity, but even the nuttiness is quite easygoing.

I recommend no. 4, Spicy Cheese Terimayo.