Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

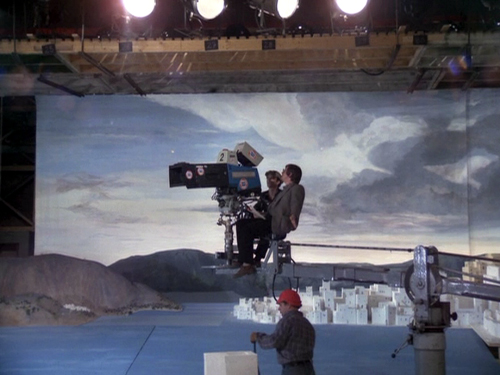

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

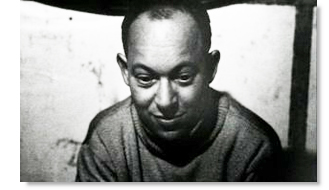

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.

Exasperating and exhilarating, Film Socialisme shows no flagging of its maker’s vision. “He’s a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher,” a friend remarked. Or perhaps he’s a filmmaker who thinks he’s a painter and composer. In any case, Film Socialisme will be remembered long after most films of 2010 have been forgotten. More intransigent than most of his other late features, and unlikely to be distributed theatrically outside France, if there, it shows why we need “little” festivals like Cinédécouvertes now more than ever.

The home page of the Cinematek is here. A complete list of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes winners is here. Last year, between research and preparing for Summer Movie Camp, I had no time to blog about the festival. But you can go to my earlier coverage for 2007 and 2008.

As one who cares about Godard’s aspect ratios, it pains me to use illustrations from online sources, which are notably wider than the version I saw projected in Brussels. When I can get my hands on a proper DVD version, I will replace these images with ones of the right proportions.

Seeing movie seeing: Display monitors in the reception area of the Cinematek.

Off to Yurrp; but first….

Photo by Marc Vernet.

DB here:

Over the last few weeks we’ve added a fair amount of material to this site. As Kristin and I pack for our annual trip to Cinema Ritrovato (Ford! Godard! Donen! Capellani! 1910!), in what we Americans know as Yurrp, I thought I’d mention them. All can be found in the left column, but I’ll link to them too.

First, more on the Danish cinema of Dreyer’s earliest days. As background to my recent essay on Dreyer’s first film, I’ve revised and updated an essay on style in Nordisk films of the 1910s. Even if you don’t want to read it, I think you’ll find it pretty to look at, and most of the (many) illustrations come from rare 35mm prints. Thanks to Dan Nissen and Lisbeth Richter Larsen, who edited the first version and gave me permission to publish this new one here. Thanks as well to archivists extraordinaire Thomas Christensen and Mikael Brae for their help during my visits to Copenhagen.

Second, I’ve added pdf extracts from two of my books. There’s the introduction to The Way Hollywood Tells It, already kindly flagged by Catherine Grant of Film Studies for Free. I’ve also added two bits from Poetics of Cinema. There’s the somewhat polemical introduction, and there’s the piece I wrote on eye behavior in film performance. Yes, I’m already known as Professor Blinky. But read before you condemn. Maybe you’ll even be enticed to read the rest of the books. I can dream, can’t I?

Most quietly, we’ve added a facile Print command so you can make hard copies of any of our entries, including our most ancient ones.

One of our many summer tasks is to go back through our early entries and clean them up, fixing photos, restoring what broken links we can, etc. Mark Minett has been diligently combing our blogs and we’ll try to shape them up….after we get done watching movies at Bologna, and then Brussels. From there I hope to file a report on my visit to the Musée Hergé, which is holding a Joost Swarte exhibition. (Swarte is one of my favorite cartoon artists.) Of course Brussels also boasts the remarkable annual festival Cinédécouvertes, which is showing many new titles, including Godard’s Film Socialisme. I am so there.

Thanks as usual to our web tsarina Meg Hamel for her efforts in putting up all this stuff, not to mention putting up with me. Next week, some observations from Bologna.

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.

DER GOLEM: Revisiting a classic

Kristin here:

In 2009, Il Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent-film festival held each year in Pordenone, Italy, launched a new series. “Il canone rivisitato/The Canon Revisited” addressed the fact that many rare and often obscure silent films are made available through restoration each year, and yet many young enthusiasts who have started attending the festival have seldom had the chance to see the classics on the big screen with musical accompaniment. The opening group of films proved highly successful, and “Il canone rivisitato 2” will be presented this year, when Il Giornate will run October 2 to 9.

Part of the point of the series is to have historians re-evaluate these classics and examine how well they live up to their status as part of the film canon. Last year I contributed a program note on Paul Wegener and Karl Boese’s 1920 German Expressionist film Der Golem. This year I’ve written about Danish director Benjamin Christensen’s 1916 thriller Hævnens Nat (Night of Revenge, released in the U.S. in 1917 as Blind Justice), which will be shown this year, and rightly so.

When I went back and reread my Golem notes to remind myself what sort of coverage is needed, I decided that the text I wrote then might be of wider interest to those who weren’t at the festival last year. Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai, one of the festival’s founders and organizers, for permission to revise my brief essay as a blog entry. I’ve changed it minimally and taken the opportunity to add illustrations. Here’s what I said at the time:

Der Golem is a classic film—doubly so.

First, it has long nestled comfortably within the list of titles that make up the German Expressionist movement of the 1920s. Teachers of survey history courses are more likely to show Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (which premiered in early 1920) but a serious enthusiast will make it a point to see Der Golem (which appeared later the same year) as well.

From the start, reviewers recognized Der Golem as Expressionist. In 1921 the New York Times’ critic wrote, “Resembling somewhat the curious constructions of THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, the settings may be called expressionistic, but to the common man they are best described as expressive, for it is their eloquence that characterizes them” (George Pratt’s Spellbound in Darkness, p. 362). In 1930, Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, the most ambitious world history of cinema in English to date, appeared. Highly influential in establishing the canon of classics, Rotha adored Weimar cinema, including Der Golem.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art obtained a large number of notable European films. The core collection of the young archive contained such prestigious titles as Caligari, Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, and Der Golem. These films soon became part of the museum’s 35mm and 16mm circulating programs. With MOMA’s sanction as historically important classics, they remained the most widely accessible older films available to researchers and students alike for many decades.

There is, however, a second, largely separate audience: monster-movie fans. Starting in the 1950s, German Expressionist films were promoted as horror fare by Forrest J. Ackerman in his magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. In 1967 Carlos Clarens included Der Golem in his An Illustrated History of the Horror Film. Really dedicated horror devotees pride themselves on their expertise across a wide variety of films, including foreign and silent ones. Der Golem became a certified horror classic.

In the 1950s and 1960s, companies offering public-domain 8mm and 16mm copies for sale enabled both film-studies departments and movie buffs to start their own film libraries. Ultimately home video made previously rare silent classics easily obtainable—including a restored Golem from the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau-Stiftung, with new tinting and a musical score, on DVD. Such a presentation reconfirms the film’s status as a classic.

But what sort of classic is it? An undying masterpiece that one must see immediately? A film one should definitely watch someday if the chance arises? On the occasion of Der Golem being presented on the big screen with live musical accompaniment, we have a chance to specify what distinguishes it from its fellow exemplars of Expressionism.

I suspect that horror-film fans won’t feel that a reevaluation is necessary. Der Golem is a forerunner of Frankenstein and hence an important early contribution to the genre. It’s a striking film to look at and obscure enough to impress one’s friends during a late-night program in the home theater.

But for film historians returning to Der Golem in the early twenty-first century, after nearly ninety years of taking it for granted, what is there to say?

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

It’s a subject susceptible to endless debate. To avoid that, it’s helpful to accept historian Jean Mitry’s simple, useful distinction between graphic expressionism, with flat, jagged sets, and plastic expressionism, with a more volumetric, architectural stylization. If Caligari introduced us to graphic Expressionism in 1920, Der Golem did the same for plastic Expressionism later that year.

For me, seeing Der Golem again doesn’t much affect its status as an historically important component of the German Expressionist movement. It’s not the most likeable or entertaining of the group. Caligari has more suspense and daring and black humor. Die Nibelungen has a stately blend of ornamental richness with a modernist austerity of overall composition, as well as a narrative that sinks gradually into nihilism in a peculiarly Weimarian way.

Moreover, Der Golem’s narrative has its problems. None of the characters is particularly sympathetic. Petty deceits and jealousies ultimately are what allow the Golem to run amok. The narrative momentum built up in the first half of  the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

But putting aside Der Golem’s minor weaknesses, it has marvelous moments that summon up what cinematic Expressionism could be: the opening shot, which instantly signals the film’s style (below); the black, jagged hinges that meander crazily across the door of the room where Löw sculpts the Golem; the juxtaposition of the Golem with a Christian statue as he stomps across the crooked little bridge returning from the palace (at top).

Hans Poelzig was perhaps the greatest architect to design Expressionist film sets. He designed only three films, and Der  Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Speaking of performances: A lot of the actors in German Expressionist films were movie or stage stars who didn’t specialize in Expressionism. There were, however, occasional roles that preserve the techniques the great actors of the Expressionist theater. There’s Fritz Kortner in Hintertreppe and Schatten. There’s Ernst Deutsch, who acted in only two Expressionist films, as the protagonist in the stylistically radical Von morgens bis Mitternacht (out this month on DVD) and as the rabbi’s assistant in Der Golem.

Just watching his eyes and brows during his scenes in this film conveys something of the experimental edge that Expressionism had when it was fresh—before its films had become canonized classics.