Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Manny Farber 1: Color commentary

Manny Farber, undated photo. Courtesy of Patricia Patterson.

The original entry at this URL, published 17 March 2014, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

I explain the development of the book in this entry.

Thank you for your interest!

I am a camera, sometimes: TIM’S VERMEER

DB here:

Sometimes you sense that a film is made especially for you, and you expect to enjoy and admire it well before you see it. This happened, I guess, with millions of people and films like Star Wars, Twilight, and The Hunger Games. I didn’t share those viewers’ hopes, but I knew from advance publicity that I would be keenly interested in the new documentary, Tim’s Vermeer.

Why? It involves Penn & Teller, two demigods of mine; it’s about art and technology; and it investigates the possibility that a painter used optical devices to create glowing, mysterious images. In the process, it reawakens the controversy around David Hockney’s thesis in Secret Knowledge that many old masters were employing lenses and mirrors to render nature with unprecedented richness.

I wasn’t disappointed. It was the most intellectual fun I’ve had at the movies in the last year.

It’s hard to explain technical stuff clearly, and even harder to dramatize it so that audiences are engaged. Tim’s Vermeer teaches you a lot about art, technology, and human will and skill. The personality of the central figure makes the tale engrossing and funny, often suspenseful, and at moments a little wistful. At the same time you get to study one of the greatest paintings in the western world in a thoroughly unpretentious way.

There, I’ve made my recommendation. Stop now if you want your experience completely unsullied. But you’ve perhaps read other reviews, and nearly everything I mention in what follows is mentioned in at least one of those. Sony Pictures Classics has kindly put the screenplay online, so there really are no secrets if you’re determined to know it all. I want merely to convey some of the excitement the film gave me. It explores a fascinating problem in art history through one man’s patience, ingenuity, and determination.

Tim Jenison, a wealthy software innovator, is a polymath—musician, tinkerer, and fan of art. He is not a painter, but he works with images constantly; part of his fortune derives from Video Toaster and other postproduction software. He comes across as articulate, avuncular, and gifted with a self-deprecating sense of humor.

In 2001 Tim learned of two recently published books, Hockney’s Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters and Vermeer’s Camera, a more academic investigation by Philip Steadman. Steadman made a strong case for Vermeer’s use of a camera obscura in painting his pictures.

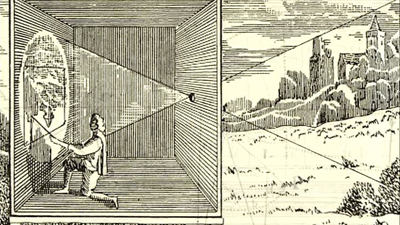

The camera obscura is a box that uses a small hole and lens to project an image of the scene outside the box. The image appears, inverted and flopped side to side, on the wall opposite the lens. Project the image onto a drawing surface, and you can trace it, although it’s difficult and requires a lot of practice.

The photographic camera is such a device, using film stock or a chip to fix the image. Amateurs used portable camera obscuras for some centuries before photography, and there’s evidence that Canaletto and other major artists employed them. A camera obscura (or “dark room”) can be any size, and it’s possible to set one up as a booth in a parlor. This is what Steadman suggested Vermeer did. Features of the paintings, such as perspective convergence and certain visual distortions, were characteristic of camera obscura images.

Hockney made bigger claims. He proposed that use of the camera obscura, along with convex mirrors and other optical gear, went far beyond Vermeer and a few other image makers. Caravaggio, for instance, seemed to him a master of staging tableaux vivants in his cellar and then copying what his array of gadgets yielded—in effect, creating a photographer’s studio.

Hockney’s proposals created a storm of controversy, with art historians, optical scientists, and cultural critics driven to fury. A common ad hominem complaint was that Hockney didn’t draw well himself and used photography to help him, so he would naturally denigrate a draftsman of genius. You can see some links to the debate in this entry’s codicil.

Steadman, a historian of architecture, used the perspective presented in the paintings to calculate the dimensions of the room and the placement of the camera obscura, and as a result he could measure the size of the projected images, which uncannily matched the size of the finished paintings. Tim took another direction.

By reflecting the camera obscura image into a hand mirror that he could position just above the picture in progress, Tim found that without training or talent he could copy a scene with astonishing accuracy. He started without a camera obscura, just using the hand mirror to paint an image from a photo of his father-in-law. The result encouraged him to go farther—much farther.

Tim’s Vermeer documents Tim’s painstaking process. He used 3D mapping to plot the space shown in The Music Lesson. He then built the room and furnished it with life-size replicas of the furniture and fittings. He ground authentic versions of the pigments and lenses used in Vermeer’s era. He even found models to stand, fixed in place by clamps, while he painted, with infinitesimal slowness, the image caught by his lens and hand mirror. By trial and error he found that adding another mirror helped even more. He was painting from a three-dimensional scene, as captured on a camera obscura.

The entire project consumed 1825 days. Documentaries always document more than they intend to, and part of the film’s attraction is its portrait of a man driven to the limit to test his hunches. His presence adds a human narrative to what could have been considered a dry academic debate. You have to wonder what Herzog would have made of this multimillionaire spending years trying to replicate a masterpiece.

Tim’s obsession yielded a remarkably exact version of the scene done entirely by hand, eye, and optical devices. The film shows Hockney and Steadman approving Tim’s picture as a valid “proof of concept,” as he calls it.

The film is carefully clear about what Tim’s demo didn’t prove. He hasn’t shown that Vermeer did it this way. We have in fact no written documents concerning how Vermeer produced his pictures, so our inferences are based wholly on the paintings and the historical circumstances. For example, Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, celebrated microscopist, lived in Delft at the same time and served as executor of Vermeer’s estate. But no documents indicate that they discussed lenses, or even knew one another.

Nor has Tim proved that he’s as good as Vermeer. Hockney insists that paintings are marks and “machines don’t make marks.” Vermeer’s touch may be inimitable and owe nothing to optics.

And Tim hasn’t supported Hockney’s suggestion that there’s no other way Vermeer could have gotten his distinctive look. Admittedly, thanks to perceptual psychologist Colin Blakemore, Tim found that Vermeer’s pictures include visual phenomena that aren’t available to our unaided eye, such as fine gradations of light on a pebbly surface. Still, perhaps Vermeer was familiar with optically generated images and imitated them, freehand, in his pictures. Perhaps he used a camera obscura simply as inspiration and a guide to visual discovery.

What Tim has shown is that a simple knowledge of how light behaves in mirrors and lenses–knowledge that was available in Vermeer’s milieu—could enable someone to produce images of extraordinary accuracy and detail, if he or she were willing to expend a hell of a lot of time and trouble.

Lawrence Gowing suggests that to Vermeer the drudgery that Tim underwent was exhilarating.

It was in the camera cabinet perhaps, behind the thick curtains, that he entered the world of ideal, undemanding relationships. There he could spend the hours watching the silent women move to and fro.

Maybe Vermeer was, as Tim suggests, an ancestor of today’s CGI geeks, toiling over his picture for days and weeks, though without the benefit of pizza and Mountain Dew. There are thousands of such people today. Were they around then too? Was Vermeer the first keyboard monkey?

The outsider’s risk

Here are some objections to the Hockney-Steadman-Jenison line of argument. I don’t think they’re insurmountable.

There are always crank theories around. But although the public discussions of Hockney’s thesis came close to calling him nuts, it’s worth listening to an artist’s conception of how another artist might work—especially when the skeptics aren’t practicing artists themselves. Hockney isn’t proposing the sort of numerological theories we get, say, in the film Room 237, or the “secret geometries” line of argument that maintains that every line and mass proves the artist was a Rosicrucian or a Freemason. Hockney’s theory may be wrong, but it’s not wacko.

Jenison is a naïve dabbler from outside the art world and lacks certified expertise. Again, it’s not a matter of who floats an idea but how valid the idea is. Why couldn’t a computer-graphics expert come up with enlightening ideas about pictures? Craftsmen in any domain often spot fine points that lay people can’t.

Besides, insiders can be mistaken. Forgers have long fooled connoisseurs. The Smiling Girl picture above was shown as a Vermeer at London’s Royal Academy in 1929, but now it’s regarded as a fake.

It’s too easy. If this were all there were to painting lifelike pictures, you might say, any kid could do it. Well, not many would have the patience. Tim spent 130 days painting the picture and he nearly gave up. It was stressful, hard on his back, and strewn with unexpected obstacles. He had to take frequent breaks. Freehand drawing is a lot easier, not to mention faster. Although Tim is no painter by training, he clearly has a careful eye and extreme fine motor control in his fingers. I, who can scarcely draw a straight line with a ruler, couldn’t do what he did.

It’s too hard. Tim’s painstaking dabbing is laborious, others might grant, but it’s donkey work. His conception of art is “difficulty of doing,” but there are lots of things that are hard to do, like building ships in a bottle, and they aren’t art. But all art requires discipline, and in those times experts labored for days over bits of the canvas that hardly anybody would notice. As a craft, painting is inherently hard, but we can scarcely imagine the amount of energy invested in the voluptuous images of Vermeer’s period. Damien Hirst can whip up high-priced paintings fast for today’s market, but conditions at that time would slow him down. He’d probably have to catch his own shark.

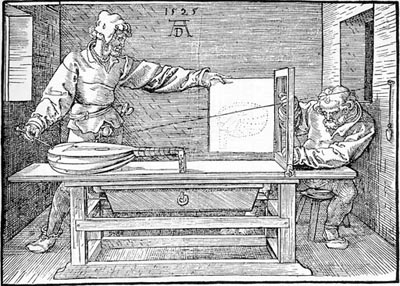

It’s too reliant on technology. But art has used mechanical devices for centuries. The best examples, very relevant to Vermeer, are all the drawing aids associated with perspective, including not just straightedges and protractors but complex gadgets like Durer’s famous converging-string setup that allowed him to draw curved volumes.

Such devices are shortcuts to deploying the geometry of the system. As Steadman says in the film, “Perspective is an algorithm.”

Later eras have given us much art dependent on technology, from tubes of oil paint to Hockney’s own Polaroid- and iPad-assisted imagery. And of course film and video art wouldn’t exist without machines. Hockney puts it well from the standpoint of the practicing painter:

[Raphael] would have wanted to make as vivid a portrait as he could. As a professional painter, he had a job to do and would have used all the tools at his disposal, including, if he thought they would help, lenses. He would not think, “I’m a great artist at the height of the Renaissance who should disdain such methods.”

Hockney and Steadman report that practicing artists they’ve encountered have been far less hostile to their ideas than art historians have been.

It insults greatness. I suppose this is what Susan Sontag meant by saying, “If David Hockney’s thesis is correct, it would be a bit like finding out that all the great lovers of history have been using Viagra.”

Actually, the copying of a camera obscura image isn’t as mechanical as one might think, but even if it were, would it be devastating? We allow photographers, with their mechanisms for intercepting light rays, the status of great artists.

The objection rests on a valid point. We do need to know something of how an artwork was made in order to understand and judge it. But in this case I don’t think that discovering that Vermeer used mechanical aids would minimize our appreciation of the pictures. It might, however, change our sense of how he relates to the traditions that followed. This change in our understanding is something Hockney and Jenison hope to bring about.

It dispells the mystery. This is the toughest argument to counter because it assumes that we want mystery in our art. It seems to me ultimately a religious way of thinking about art. I’m enough of a rationalist to hope that in any area, research can turn some mysteries into puzzles, then turn puzzles into problems, and maybe solve some of the problems.

There’ll always be a residue of questions we can’t answer. Given the feeble progress we’ve made in understanding art, no one should worry. We researchers nibble at the edges, and the Big Mysteries aren’t going away any time soon. In the meantime, we can ask whether Tim, along with Hockney, Steadman, and others, has answered some worthwhile questions about how Vermeer made his pictures.

My wish list

Here are some matters that a longer film would probably have been able to tackle. I’d love to see a version that did.

How does Vermeer fit into the broader history of art? The painting traditions in which Vermeer worked—genre scenes, portraiture, perspective–aren’t articulated in the film. In addition, the use of the camera obscura by other painters could be brought out. Perhaps the assumption is that Hockney covered that territory.

Still, to avoid certain accusations, it might have been better to grant that artists blend talent, training, and hard work with selective knowledge of what earlier artists have done, and what rivals are up to. E. H. Gombrich emphasizes the various factors involved: the tasks that artists undertake, their tools, their techniques (including inherited visual patterns, or schemas), the problems inherent in a project, and the artist’s circumstances, such as competition with other artists and the fluctuating tastes of their audience.

The exactitude of Vermeer’s interiors, for instance, is in tune with contemporary Dutch paintings of household routines (so-called genre painting) and of still-life paintings of foods glistening on a tabletop. There was a taste for meticulous presentation of everyday life at the time, and this probably impelled Vermeer toward his unique brand of realism. Was he trying to top his rivals? The film suggests that his delicacy and precision surpass what’s on display in contemporaries like Pieter de Hooch.

What counts as realism? Vermeer’s pictures look fantastically accurate, and have for some time. But he selects only certain dimensions of reality to capture. Other painters focus on movement, which is all but absent from Vermeer’s images. There’s a snapshot quality to Baroque representations of figures in action, which look scarily realistic. And many other painters render details that impress from a distance or even close up; Jan Van Eyck is probably the most famous.

What about the lenses and mirrors? Tim goes to great lengths to mimic the features of Vermeer’s room and to mix paints as he might have. The film is mostly silent, though, about his optical devices. What focal lengths were the lenses in camera obscuras? We know that different focal lengths render perspective in differing ways. Some of the distortions commentators have found in Vermeer’s picture seem to proceed from wide-angle coverage. Moreover, Tim’s hand mirror and convex mirror seem to be modern ones. Are these enough like what Vermeer would have had available?

Did Vermeer alter the perspective projection he obtained? Many painters who calculated perspective felt free to adjust it or confound it for the sake of expressive effect. Famous pictures are full of inconsistent vanishing points, often masked by figures or items of setting. Tim’s painting obeyed what his camera gave him, but perhaps Vermeer adjusted his image. Consider, below, some details from Vermeer’s picture (left) with Tim’s (right). (Ignore color differentials, since the reproductions of the original vary so much.)

Did Vermeer fiddle with what the camera showed? I’m not thinking so much of the disparities in the placement of the figures above, which are probably to be expected; we’d be shocked if Tim’s setup worked exactly the same as Vermeer’s. I’m more concerned with the way in which Vermeer seems to have cheated perspective with respect to the reflection.

It looks as if Tim tried to match the reflection, but to do that he had to have his daughter turn slightly to the right. Yet Vermeer’s young woman faces the mirror head-on, while the reflection shows her in high-angle three-quarter view. Was the mirror slightly tipped on the left edge? And did it hang out from the wall slightly more than in Tim’s chamber? I wonder if Vermeer simply wanted to have it both ways–a head turned squarely away from us, a reflected face that wouldn’t be gazing straight out but rather pensively downward. Classic pictures often contain such expressive compromises with geometrical exactness.

Do we overrate the clean image? Tim, coming from the computer-graphics world, seems to have accepted the current assumption that the most faithful and attractive image is razor-sharp. He’s fascinated by the undeniably exact textures on the fabric and the wood and plaster surfaces. He thinks that Vermeer ‘s images resemble “a video signal” and that they glow like the images on a movie screen (that is, nowadays, a digital image).

But Tim’s High-Def aesthetic plays down some of painting’s traditional resources, notably sfumato. And art historian E. H. Gombrich notes that Vermeer’s precision retains “mellowed outlines” and doesn’t seem harshly photographic. Going back to the details above, to my eye, Vermeer’s image isn’t as sharp as Tim’s. The faces are sketchier, and the shadows have softer contours.

Gombrich and others have made much of the crucial role of suggestion and incompleteness in painting, especially paintings that are seen at a distance. Our perceptual systems fill in dashes and blobs with specific features, but Tim’s algorithm may chop too fine. The difference should give comfort to the people who emphasize Vermeer’s idiosyncratic paint handling. It would be worth seeing if Tim thinks he could recalibrate his pictorial mesh to soften the image somewhat.

Problems and solutions

Tim’s Vermeer is an entertaining lesson in how rational inquiry into the arts proceeds—posing a problem and then using inference and evidence to frame possible solutions. The film also shows how a problem usually has many facets, which sometimes have to be dealt with piecemeal.

A piecemeal approach is particularly pertinent to reconstructing Vermeer’s methods. Many art historians would grant that he, like others, might have used a camera obscura to imagine or sketch out the basic composition of the piece. But the crucial later phases of painting would have been carried out by eye and hand unaided. What is characteristic of the Hockney—Steadman—Jenison line is they try to indicate how much of Vermeer’s practice can be accounted for by optical aids.

Assume that Vermeer used a booth-type camera obscura. That device could yield general contours. Steadman charted other features of the camera obscura that show up in the master’s paintings, such as variable focus, light scattering, and perspectival distortion characteristic of lenses. He went on to build a scale model of the room depicted in The Music Lesson and other pictures, and showed that Vermeer might have used a booth-type camera obscura. With the cooperation of the BBC, Steadman built a life-size model of the system he discovered.

Reading Steadman’s brilliant book when it appeared, and then visiting his website where things are spelled out a little more, pretty much convinced me of his argument. But I didn’t think much about lighting or color.

Vermeer’s “mellowed outlines” are often given by minute shadings of tonality rather than firm outlines. Yet when you’re in the booth, it’s so dark that you can’t determine color accurately. This is where Tim Jenison comes in. What sort of optical device could yield such gradations of color?

Tim discovered that a small mirror mounted on a rod over the drawing surface would allow an artist to build color patches, as well as masses and contours, by slightly shifting her gaze from the mirror’s reflection of the camera’s image to the picture being made. You’ve achieved the right tonality, Tim points out, when the edge of the mirror seems to disappear. In this image, the disc you see isn’t clear glass but rather a mirror reflecting the camera obscura’s image, which is outside the frame.

Dim light in the booth doesn’t matter because both the image and the color you match are illuminated uniformly. The result, in the film, shows a remarkable degree of similarity.

But the optical projection remains a bit pale and lacking in detail; more concentrated and focused light is needed. Teller’s film shows how Tim hit upon the idea of focusing and brightening the camera image by projecting it onto a concave mirror rather than a flat plane. A mirror is also a projecting surface, and its reflection can amplify the camera lens’s image. With this array of lenses and mirrors, you don’t need to work in darkness and you don’t need a barrier between you and the scene.

At this point, Tim’s demo has demolished the darkened chamber itself. Maybe this is what Vermeer actually used, although if he wanted to hide his methods, the booth with its wall or curtain would have been preferable.

Another lesson in rational inquiry: Controlling for variables can encourage anomalies to pop out. In drawing the harpsichord in the picture, Tim had assumed straight edges, which he outlines with a ruler. But in painting the undulating seahorse motif on the surface, he discovered that his lens rendered the motif as very slightly curved. When you check the painting, you find that Vermeer’s motif does the same thing.

The curve, which Tim dubbed “The Vermeer Smile,” is characteristic of the distortion yielded by a lens. Your eye and brain don’t see it that way, however, and painters working freehand would automatically make the seahorses prance in a straight line.

In short, just as Vermeer’s lens may have allowed him to make discoveries about the behavior of light, Tim’s lens gave him a new insight into Vermeer’s art.

Photography without film

Suppose we buy the whole package. Assume that Vermeer used Tim Jenison’s hardware. What then does his art consist of?

In Film Art: An Introduction we distinguish four areas of cinema technique: mise-en-scene, cinematography, editing, and sound. Editing and sound aren’t relevant to Vermeer (though Eisenstein might make an argument for “montage” operating within the master’s “shots”). But the other techniques are, if we imagine him making unmoving movies—that is, photographs.

Mise-en-scene involves what is photographed. Vermeer controls the setting, picks the props, and costumes, and arranges the lighting. He determines the color within the scene. He also stages the action, although there isn’t much movement. Gombrich calls his paintings “still lifes with human beings.”

Cinematography has an equivalent in Vermeer’s art too. He must select a lens for the camera obscura, and he has to focus it. Most commentators agree that painters who used the device focused on different areas of the scene as they needed to paint them. Vermeer doesn’t use film, of course, but he does have paint, and the properties of that medium have to be taken into account. In Tim’s words, as he sits brushing in tiny strokes, “I’m a piece of human photographic film.”

Vermeer also has to frame the scene, which is a bit tricky because the camera obscura doesn’t yield a rectangular image but rather a circular one. Here is Steadman’s reconstruction of the camera’s visual output, flipped to match the painting and reproduced in black and white.

Vermeer has to crop the projected image in advance, much as a cinematographer today has to visualize the image’s final shape as seen on the viewfinder or monitor.

Staging and framing in The Music Lesson yield an unusual composition. What’s the subject of the painting? The woman playing? She’s turned from us, seen from afar, and quite decentered. True, she’s reflected in the mirror. But Steadman shows that this mirror is ambiguously drawn. It also seems to be angled so as to conceal the opposite end of the room—a ploy familiar to scholars of early cinema, when such tipped mirrors hide the movie camera.

Thanks to the oddly empty space in the left half of the picture, our attention drifts often to the empty space separating window, furniture, and people. Vermeer is in effect painting the journey of light hitting various surfaces. The streaming sunlight endows a patch of the rug, the bottom of the viola, and the upholstery tacks with a glow and brightens the woman’s sleeve. Then it thins into a more diffuse illumination before hitting the jug as a brilliant pictorial climax.

Perhaps he’s painting how air looks.

Vermeer’s zones of choice and control overlap with those of a photographer or a filmmaker. Or those of an illusionist. As stage magicians, Penn and Teller know the classic putdown: “Aw, they do it with mirrors.” The film might be their answer: “Yeah, and it works.” They and Tim Jenison have created a landmark film that ponders the interplay of science, tools, and artistic creativity.

Special thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Merijoy Endrizzi-Ray of Sundance Madison. Thanks as well to Kristin Thompson, Diane Verma, and Darlene Bordwell for conversations about the film.

The controversy over Hockney’s theses can be traced in the Wikipedia entry The Hockney-Falco Thesis. My quotation from Susan Sontag comes from Wyatt Mason on ArtKrush. The camera obscura image of The Music Lesson comes from Philip Steadman, Vermeer’s Camera, p. 123, as does my Lawrence Gowing quotation (p. 165). I’m grateful to Steadman on many levels, not least because his website encouraged me, in 2002, to set up the one you’re visiting now.

For further information on the general research area, see Martin Kemp, The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. Kemp corresponded at length with Hockney, and portions of their exchanges are included in Secret Knowledge.

Gombrich’s comments on Vermeer come from Chapter 20 of The Story of Art. His classic Art and Illusion elaborates his account of inherited pictorial schemas and their revision across history.

Hockney has defended the film and explained further. Kurt Anderson has offered a valuable overview of the making of Tim’s Vermeer in Vanity Fair. Several video interviews cast light on the process as well. Here Teller, Penn, and Jenison discuss the film with Kent Jones at Lincoln Center. David Poland sits down for a 30-minute interview with Penn and Jenison. Philip Steadman discusses how Tim’s ideas build on his book in this University College London video.

Jonathan Janson’s site offers good coverage of the film’s reception, here and here.

One reviewer considers Tim’s theory “wackadoodle” but misunderstands it, saying that “Vermeer might have created his masterpieces by putting his models in a camera obscura.” Then he told them scary stories in the dark, I guess. More attentive reviews of the movie include one by Peter DeBruge in Variety and another by Todd McCarthy in The Hollywood Reporter.

You know Penn and Teller as conjurors and hosts of the show Bullshit! (My favorite episode: the animal mind-reader.) Be sure to read their books too.

Team Vermeer: Standing: Philip Steadman, Teller, Tim Jenison. Seated: David Hockney, Penn Gillette.

PS 12 March 2014: Painter Jane Jelley has proposed a way that Vermeer could have made his pictures using a camera obscura but without mirrors. She reports success replicating that method herself. Her article and some background to her experiment are available here. I thank Ms. Jelley for writing me with this information. The controversy continues, which makes me happy.

How to write: Professor Westlake is in

Donald Westlake in 2001. Photo by David Jennings.

DB here:

There can be no question of my doing justice to the writing of Donald Westlake, also known as Richard Stark, Tucker Coe, and other cover names. For background you can go to his fine site or to Wikipedia, or this warm appreciation by Michael Weinreb. Here I just want to pay brief tribute to a writer who, like Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, seemed incapable of composing a bad sentence. Elmore Leonard gets deserved recognition as a laconic master of language, but Westlake was no less skillful. In some ways he was more ambitious and audacious.

He was astoundingly versatile. He wrote straight novels, erotica, and science-fiction, but fame came to him when he worked in three registers: terse toughness, wry comedy, and straight-up farce.

As Westlake he wrote psychological thrillers. Best-known, I think, is The Ax (1997), about a downsized executive eliminating the competition for jobs that might come up. Also as Westlake, he wrote comic crime novels. Many of these center on a gang of inept working-class thieves led, if that’s the word, by the hapless John Dortmunder. As Richard Stark, Westlake wrote very hard-boiled novels about Parker (no first name), an utterly emotionless professional thief, and his sometime assistant Alan Grofield.

Westlake rang many variations, both high and low, on the heist formula, and his plotting was fastidious. He made one story do for two novels by telling it from different viewpoints (Slayground and The Blackbirder, both 1971). The plot of one Dortmunder novel, Drowned Hopes (1990), was so complicated that it left interstices for Westlake’s friend Joe Gores to fill in an intersecting novel, 32 Cadillacs (1992).

Nearly all the Stark books have a strict four-part structure. In the early books, this is used to mark segments of time and to shift point of view. Elsewhere Westlake uses this pattern to rearrange blocks of time, so that part one takes place in the present, leading to a crisis. Parts two and three flash back to what led up to the book’s first chapter. Part four finishes up the action left hanging in part one. This layout was both a trademark and a self-imposed constraint that Stark-Westlake had to overcome in every book. Today’s young fiction writers could learn construction from these trim, no-nonsense tales.

At the moment, though, our topic is style. Here is the opening of Stark’s The Mourner (1963).

When the guy with asthma finally came in from the fire escape, Parker rabbit-punched him and took his gun away. The asthmatic hit the carpet, but there’d been another one out there, and he landed on Parker’s back like a duffel bag with arms. Parker fell turning, so that the duffel bag would be on the bottom, but it didn’t quite work out that way. They landed sideways, joltingly, and the gun skittered away into the darkness.

There was no light in the room at all. The window was a paler rectangle sliced out of blackness. Parker and the duffel bag wrestled around on the floor a few minutes, neither getting an advantage because the duffel bag wouldn’t give up his first hold but just clung to Parker’s back. Then the asthmatic got his wind and balance back and joined in, trying to kick Parker’s head loose. Parker knew the room even in the dark, since he’d lived there the last week, so he rolled over to where he knew there wasn’t any furniture. The asthmatic, coming after him, fell over a chair.

The economy is remarkable. There’s no explicit indication that we’re in a hotel room, or that Parker has been waiting for the invasion. This is in medias res storytelling, a Stark specialty. (Many of the novels begin with a “When…” clause.) In a couple more paragraphs, Parker gets the advantage and knocks out both men. “The asthmatic went down, hitting furniture on the way.”

The faintly amused tone here (being caught by “a duffel bag with arms,” kicking a man’s head “loose,” falling over a chair) is stronger in the Stark novels centered on Grofield. He’s a semi-professional actor who goes in for theft to finance his small-town theatre troupe. Parker is introverted, stoic, and borderline sociopathic, while Grofield is laid-back, good-natured, and quick with backchat. The opening of The Damsel (1967), parallel to that of The Mourner, shifts toward the deadpan comedy of the Dortmunder capers.

Grofield opened his right eye, and there was a girl climbing in the window. He closed that eye, opened the left, and she was still there. Gray skirt, blue sweater, blond hair, and long tanned legs straddling the windowsill.

But this room was on the fifth floor of the hotel. There was nothing outside that window but air and a poor view of Mexico City.

Grofield’s room was in semidarkness, because he’d been taking an after-lunch snooze. The girl obviously thought the place was empty, and once she was inside she headed striaght for the door.

Grofield lifted his head and said, “If you’re my fairy godmother, I want my back scratched.”

Opening one eye, then the other: The micro-action is as vivid as Rod Steiger or Eli Wallach playing up to us in a Leone film. The tone has changed too. Words like “snooze” wouldn’t show up in a pure Parker novel, I think. And now we get some scene-setting, but that’s because the wounded Grofield, flat on his back, can’t give us a tour of the room through physical action. What replaces Parker’s tussle is sexy banter. After the woman finds a suitcase full of cash, she gets suspicious. Grofeld explains: “I wear money.”

Finally, here’s extravagant burlesque from a non-Dortmunder story, Help I Am Being Held Prisoner (1974). The plot, about a practical joker who is thrown into prison among hard cases, is preposterously enjoyable, but again it’s the style that arrests, and convulses. The protagonist is accompanying Eddie, a demented ex-officer after they’ve broken out of the joint, sneaked onto a military base, and settled down in the mess for dinner.

“Speaking of landing on mines,” he said, “that reminds me of another funny story.” And he proceeded to tell it. Soon our food came, and so did the wine, but Eddie kept on telling me his reminiscences. Friends of his had fallen under tanks, walked into airplane propellers, inadvertently bumped their elbows against the firing mechanism of thousand-pound bombs, and walked backwards off the flight deck of an aircraft carrier while backing up to take a group photograph. Other friends had misread the control directions on a robot tank and driven it through a Pennsylvania town’s two hundredth anniversary celebration square dance, had fired a bazooka while it was facing the wrong way, had massacred a USO Gilbert and Sullivan troupe rehearsing The Mikado under the mistaken impression they were peaceful Vietnamese villagers, and had ordered a nearby enlisted man to look in that mortar and see why the shell hadn’t come out.

It began after a while to seem as though Eddie’s military career had been an endless red-black vista of explosions, fires, and crumpling destruction, all intermixed with hoarse cries, anonymous thuds, and terminal screams. Eddie recounted these disasters in his normal bloodless style, with touches of that dry avuncular humor he’d displayed during our hour at the bar. I managed to eat very little of my veal parmigiana–it kept looking like a body fragment–but became increasingly sober nonetheless. A brandy later with coffee, accompanied by a Korean War story about a friend of Eddie’s trapped in a box canyon for nine days by a combination of a blizzard and a North Korean offensive, who kept himself alive by sawing off his own wounded leg and eating steaks from it, but who later died in Honolulu from gangrene of the stomach, didn’t help much.

It’s a challenge to a novelist to tell us something funny is coming up and then to make it much funnier than we expect, turning it into a crescendo of slapstick violence. It’s partly the appositional phrases, which pile up mishaps, and partly the mock-heroic word choices. Would you (or I) come up with epithets like “endless red-black vista” or “gangrene of the stomach”? Could we pull off that satiric stab of a massacre occurring “under the mistaken impression they were peaceful Vietnamese villagers”? Extra-credit assignment: Diagram the last sentence. Could we write something so complicated and impeccable?

By these standards, most of our novelists, beach-book maestros or middlebrow bestsellers or literary lions, don’t cut it.

Many films have been drawn from Westlake’s books. Made in USA (1966) and Point Blank (1967) are probably the most famous, but both are very free treatments. Closer to the brusque Stark spirit is The Outfit (1974), while the French version of The Ax (2005, by Costa-Gavras) is quite watchable. I haven’t seen the recent Parker, with Jason Statham, yet. Sad to report, the several Dortmunder movie adaptations don’t make me laugh much. But Westlake had no illusions: “A movie is not the book it came from and in almost every case it shouldn’t be the book it came from.” Westlake wrote screenplays too, notably The Stepfather (1987) and The Grifters (1990).

He died in 2008. He seems to have been the most easygoing, unpretentious writing machine you’d ever want to meet. The University of Chicago Press is republishing the Stark novels in handsome uniform editions, and there remain many other Westlakes that deserve unearthing. Read them for pleasure, for the smooth carpentry of their plots, and their cunning simplicity of style.

The top image, by David Jennings for The New York Times, is taken from the official Donald Westlake site, now maintained by his son Paul. My quotation from Westlake about adaptations comes from Albert Nussbaum, 811332-132, “An Inside Look at Donald Westlake,” Take One 4,9 (1975), 10-13. This postal interview, conducted by a prisoner at a penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, includes some insider information on Godard’s Made in USA.

The Outfit (1974), from the 1963 novel of the same name by Richard Stark.

A hobbit is chubby, but is he off-balance?

Kristin here–

I first read J. R. R. Tolkien’s work during what might be described as the second generation’s discovery of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit was very popular from its initial publication in 1937, enough so that the publisher asked for a sequel. Though Tolkien wanted LOTR to come out in a single volume, postwar austerity dictated that it be divided into three separate volumes. After their publication in 1954-55, a devoted following grew. The real explosion, however, came in 1965, when the Ballantine paperback editions appeared in the USA.

I was fifteen at the time and already an aficionado of Victorian literature (H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle). I was used to reading long books (David Copperfield, Don Quixote). Like so many other people who were in high school or college in the 1960s, I loved Tolkien from the start. Eventually I became an academic writer. At some point, I decided to write a book on the two Hobbit novels.

I had done a lot of reading and note-taking for that project by the time of the release of Peter Jackson’s film version, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. With reservations, I liked that film. What fascinated me more, though, was the incredible success of the innovative marketing and merchandising side of the LOTR franchise. I decided this film was going to be historically significant in a major way. In 2002, I decided to write a book about it.

The Tolkien study was put way back behind even the back burner. The franchise book needed to be written now, when I could (I hoped) get access to the filmmakers and to information that would not be available after the last part was released. With enormous good luck and help from many interviewees, I managed to write The Frodo Franchise (2007). My Tolkien project came forward onto the stove and is now in progress.

I’ve kept up my interest in the films, though. Editors have asked me to write short pieces on Jackson’s LOTR, and I’ve done four of those so far. I maintained my Frodo Franchise blog until it became apparent that I would not be granted access to the filmmakers for a book on The Hobbit. Now I’m on the staff of TheOneRing.net, for which I write occasionally. Naturally I’ve kept up on the progress of Jackson’s new trilogy.

Not long ago in these pages, I wrote about the fact that The Hobbit had been expanded from its originally announced two parts to a three-part film. To those who accused the filmmakers of doing this for strictly mercenary purposes, I countered that there were reasons why such an expansion could work well. Mainly these relate to the extra material in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, which provide information on two kinds of events: those taking place during the time period when The Hobbit’s action unfolds (most importantly an attack on Sauron’s [aka the Necromancer] lesser dark tower Dol Guldur) and those which took place in the past but which relate to characters and actions in the novel (e.g., Smaug’s attack on Erebor and Dale, the Dwarves Pyrrhic victory over the troops of the Orc Azog at Moria).

Having now seen The Hobbit three times, I want to suggest how successfully, if at all, the filmmakers have incorporated this material. For the most part the non-Hobbit material has been brought in well, or in some cases acceptably.

It’s a prequel now

One objection to the division of The Hobbit into three parts is that the book won’t support a narrative nearly as long as that of the filmed LOTR. Over and over, fans and critics have complained that Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Hobbit (1937) isn’t designed as Tolkien wrote it, as a children’s story, lighter in tone and shorter than LOTR. They often also object to those who refer to it as a “prequel.” The novel’s events took place years before those of LOTR. It was also published first, appearing in 1937, while LOTR came out in three volumes published in 1954-55. The implication is that Jackson should just have ignored the other film and stuck strictly to the novel, which is about a quarter the length of the LOTR tome. As literature, LOTR is a sequel to The Hobbit.

But the films are different. Even if The Hobbit were adapted page by page, speech by speech exactly as written, those of us who have seen the LOTR film or read the book could not see it as a separate tale. We know already what the Ring is and what eventually happened to it, while readers, if they started with The Hobbit, do not. We know that Elrond is a powerful leader among other powerful Elf leaders, destined eventually to leave Middle-earth for the Undying Lands. We know Gandalf is a wizard who will guide the various peoples through the War of the Ring. And so on. Only viewers who see The Hobbit without having seen LOTR first or having read the book or having read any of the extensive media coverage of both could come to the prequel unaware of such things. And while the novel The Hobbit is not a prequel, the film adaptation certainly is.

Because most of us do know about these major characters and premises, Jackson and his team could hardly avoid trying to make the new film match his version of LOTR. He had to treat events, characters, tone, and setting with some consistency, and he had to link the films as one long account of historical events in the same era of Middle-earth.

Tolkien himself tried to smooth out the disparities between The Hobbit and LOTR, both in tone and causal connections. He revised The Hobbit slightly in 1947, mainly to make the Riddles in the Dark scene work better in the light of what the Ring eventually became when he brought it back as a more crucial plot element in LOTR. In 1951, those revisions got into the second edition of The Hobbit and have remained canonical ever since. In 1960 Tolkien was again disturbed by the differences between the two books and launched into a more thoroughgoing revision of The Hobbit to make it conform exactly to the later events in LOTR. Others convinced him that this was a mistake and that it damaged the charm of the earlier book, already a classic of children’s literature. Eventually he allowed those disparities to remain. He did, however, write passages in the appendices that at least briefly described events that helped stitch the two books’ narratives together.

I don’t see that it’s a problem for the filmmakers to use those passages to try and make their films flow more smoothly from the first to the second. In a few years we will be able to watch all six parts of what will then essentially be a single narrative with a sixty-year gap in the middle. For better or worse, depending on one’s opinion, this is Jackson’s Hobbit. Unlike Tolkien, he is making it after already having made LOTR. He can include the links between the two tales, as well as extra plot material that Tolkien published in the 1950s but hadn’t conceived in the 1930s. The question is not whether those links and that material should have been included but whether they have been well handled.

In terms of the links, many of the ones in An Unexpected Journey seem effective. The notion of starting The Hobbit at a point just before Gandalf’s arrival for Bilbo’s 111th birthday party seems a good one: we see Frodo nailing up the “No Admittance” sign from the early LOTR scene and then heading off to read in the woods and await the wizard (above). There’s an immediate recognition factor. The younger Bilbo mentions Bree, a locale seen in LOTR, and he recalls Gandalf’s fireworks from his youth. A fireworks display also figures in Bilbo’s birthday party scene in LOTR. Bilbo’s initial awe upon arriving in Rivendell and his reluctance to leave it tie in with the fact that he goes to live there after leaving The Shire early in LOTR. Certainly the inclusion of Balin, made into a more prominent character than he is in the novel and played with considerable humor and charm by Ken Stott, should make the discovery of his tomb in LOTR a more meaningful and poignant scene. On the whole, the stitching together of the two films so far is quite accomplished, and I assume it will continue to be so through the other two parts.

But is it padded?

Most of these links between The Hobbit and LOTR are brief references or gestures, made in passing. They are not the reason that Jackson’s team decided, to considerable critical and fan uproar, to make The Hobbit in three parts rather than the originally announced two. In the earlier entry, I suggested that there was material in the appendices of LOTR that fills in information relevant to The Hobbit’s plot.

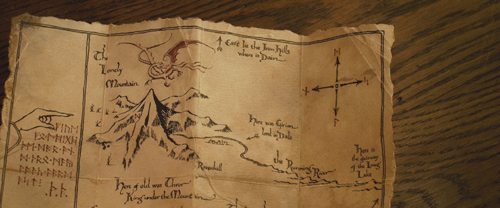

There’s the backstory of the Dwarves, involving two major events. Bilbo’s exposition at the beginning establishes their great kingdom within Erebor (the Lonely Mountain). Its king, Thror (Thorin Oakenshield’s grandfather), oversees the accumulation of a huge horde of gold and gems, and it attracts the dragon Smaug. Smaug’s destruction of the Dwarves’ home and the neighboring city of Men, Dale (portrayed briefly in a sort of Renaissance Italian style), leads to the Dwarves’ exile and hereditary king Thorin’s eventual decision to try and retake Erebor.

Second, there is the great battle fought between the Dwarves and Orcs at Moria, in which Thror is killed and Thorin earns the respect of his people by defeating the great Orc leader, Azog—chopping off his arm and leaving him, as Thorin wrongly assumes, to die.

All of this the film explains in flashbacks derived from the LOTR appendices, and this embedded material seems to me to come off well. In my opinion, most of the other scraps of text used as the inspiration for scenes not in the original Hobbit novel results in reasonably successful scenes—with one major exception, which I will deal with in the next section.

The most important extra plotline concerns the White Council (not so named in the first part of the film). Initially I speculated that the White Council scene would be a flashback to an early meeting. That’s not the case, since Gandalf meets with Elrond, Galadriel, and Saruman during the visit to Rivendell (above). In the novel, when Bilbo and Gandalf revisit Rivendell on their way back to The Shire, the Hobbit simply overhears Gandalf talking to Elrond: “It appeared that Gandalf had been to a great council of the white wizards, masters of lore and good magic; and that they had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood.”

Here, by the way, is an example of the sort of inconsistent plot points that Tolkien presumably hoped to eliminate when he struggled to revise The Hobbit in the early 1960s. By then he had written LOTR and given the Wizards their emblematic colors, so Saruman (and later Gandalf) was the only “White” wizard. The “Necromancer” would become Sauron; the “dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” gained a name, Dol Guldur. What Jackson and the other writers have done is to move that meeting of white wizards (which took place somewhere to the south, presumably either in Lothlórien and Orthanc) to Rivendell. That simplifies things.

Now the question remains, to what degree does the White Council hint that Saruman has already become treacherous? Is he dismissing Gandalf’s worries as exaggerated merely because he’s conservative and just doesn’t much respect the Grey Wizard, or is he secretly searching for the Ring himself (as Tolkien revealed in the appendices)? I hope these questions will be explored further in one or both of the upcoming parts.

Interestingly, Gandalf is already visibly frustrated by Saruman’s presence at Rivendell, and the two are at odds about the degree of danger evidenced at Dol Guldur. Saruman favors inaction, meaning that he opposes the Quest of Erebor. Gandalf sees all sorts of ramifications in the presence of the dragon and the odd goings-on at Dol Guldur. Obviously we know Gandalf is right, especially since Galadriel sides with him from the start. The explicit representation of this action within The Hobbit’s plot is, I think, off to an excellent start. I look forward to seeing how it develops.

Gandalf’s seems to regard Saruman with a mixture of frustration, annoyance, and forced friendliness and deference. How will this attitude affect our perception of Gandalf’s words about Saruman when he prepares to go and consult the White Wizard in The Fellowship of the Ring? There, as Frodo prepares to take the Ring and head to Bree, Gandalf says, “I must see the head of my order. He is both wise and powerful. Trust me, Frodo, he’ll know what to do.” In retrospect, Ian McKellen’s reading of these lines in Fellowship works in remarkably well with Gandalf’s attitude toward Saruman in the White Council scene in The Hobbit. He speaks the first two sentences quickly, without inflection, as if reciting them; we could interpret them as arising from a sense of duty rather than hope that Saruman really can or will help. The “Trust me, Frodo” sentence is accompanied by a tight smile, perhaps the sort of forced smile that Gandalf assumes as he turns to greet Saruman in the White Council scene. Given that neither director nor actor was presumably looking forward to someday adding such a scene, they turned out to be lucky that Gandalf’s speech was delivered in such a way that it could imply a lurking dislike or distrust of Saruman. (There is evidence for such distrust in the novel. In his long conversation with Frodo about the Ring, Gandalf remarks “I might perhaps have consulted Saruman the White, but something always held me back …. His knowledge is deep, but his pride has grown with it, and he takes ill any meddling.”)

One admirable thing about the Rivendell sequence is that the friendships among Elrond, Galadriel, and Gandalf are portrayed. In the book, these three have known each other for two thousand years. They are the bearers of the Three Elven Rings. Those who know only the film of LOTR are unlikely to be aware of that, since only in the penultimate scene at the Grey Havens are the three openly wearing their Rings—barely noticeable even on the big screen. Oddly, however, the licensed tie-in products for LOTR included replicas of Narya, Nenya, and Vilya, made by the Noble Collection. The three characters are able to communicate telepathically. Elrond, portrayed as rather aloof in LOTR, is a warmer figure here, embracing and teasing Gandalf, and the scene after the White Council meeting in which Galadriel reassures Gandalf and offers him her help is one of the most genuinely moving moments in the film (see top). (We never saw Galadriel and Gandalf together in the LOTR film, though they are together in some of the late book chapters that were cut in the adaptation.)

Radagast the Fool

Then there’s Radagast. The Brown Wizard appears in one scene in the novel version of LOTR, but Jackson and company eliminated him. Radagast is only mentioned in The Hobbit, but now he appears in two extended scenes and presumably will return in the later parts. Many fans object to Radagast’s being made into a comic figure, driving a sled pulled by large rabbits and hosting birds in his hair, with a resulting streak of droppings down the side of his head. Never mind that in Radagast’s one scene in LOTR, Tolkien portrays him as faintly comic, as well as timid and ineffectual. While pumping up the humorous side of the Brown Wizard, Jackson develops him into a character with considerably more gumption.

It has also been claimed that his role in the drama isn’t significant enough to warrant his presence. Did we really need all this time devoted to someone who’s there mainly to give Gandalf the Morgul blade as evidence of foul goings-on at the seemingly deserted Dol Guldur? Yet the dialogue does help motivate his importance. Gandalf declares to Bilbo, “He keeps a watchful eye over the vast forest lands to the east, and a good thing, too, for always evil will look to find a foothold in this world.” That dialogue hook leads to the first scene with Radagast, walking through the forest and finding death and decay, evidence of a mysterious force that he traces to Dol Guldur.

And the blade brought to Gandalf is definitely a significant object. When Gandalf presents it to the Council, Galadriel is very perturbed by it, and Elrond loses his initial certainty that Middle-earth is at peace. By the end of the scene, only Saruman denies the need to investigate what’s going on at Dol Guldur. Gandalf’s visit to Dol Guldur and the White Council’s subsequent actions in relation to the Necromancer’s presence there will form a crucial subplot in the upcoming parts; we’ve already glimpsed part of Gandalf’s exploration of the stronghold in the trailers.

Radagast also serves to draw the Orc band away from the Dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf. He drives his infamous bunny sled across the rolling hills, allowing the group time to find the hidden entry into Rivendell. But is the bunny sled so very ridiculous? Teanna Byerts, aka swordwhale, a member of the Message Boards at TheOneRing.net, has written an informative and amusing essay, “Radagast’s Racing Rhosgobel Rabbits: A Recreational Musher Looks at the Realities of Bunny Sledding.” It turns out that a sled would not be a bad vehicle for a woodland environment, and, allowing for the fact that this is a fantasy film, large rabbits not entirely implausible beasts for pulling them. (A Google Image search on “large rabbit” brings up some bunnies about the size of Radagast’s–and no, they’re not all Photoshopped.) The main problem is that ordinary rabbits would not pull as a team, but as Radagast says with relish, “These are Rhosgobel Rabbits!”

Although there is probably too much silliness relating to Radagast, on balance I think that he is a plus for the film and shouldn’t be dismissed as mere padding. Tolkien’s novels suggest that Radagast is a member of the White Council, one of the “white wizards” Gandalf met with down south. He lives in southern Mirkwood at Rhosgobel, a short way north of Dol Guldur. As Gandalf’s speech quoted above (not in the book) indicates, despite Radagast’s hermit-like ways and fascination with nature, he keeps an eye on things in the area. He also seems to maintain a system of bird messengers and spies for the use of the White Council. (In the novel he, not some passing moth, is responsible for the eagle Gwaihir appearing at Orthanc to rescue Gandalf.) Though Radagast never visits Dol Guldur in the book, he generally does the sorts of things that he does in the film. Although he perhaps contributes little in the first part of the film, we should withhold judgment on his importance to the plot until we see what he does in the second and perhaps the third.

The chase of the Orcs after Radagast’s sled, by the way, exemplifies one of the several lapses of causal motivation in the film. Why do the Orcs try to catch Radagast? They are specifically after Thorin, and the Orcs have no way of knowing that Radagast has any connection to the Dwarves. If they take off after every passing stranger when they are supposed to pursue a specific mission, these Orcs make very poor hunters. And while we’re on the subject, how does Radagast get all the way from southern Mirkwood, which is on the far side of the Misty Mountains, and find Gandalf so quickly?

A final note on Radagast. For those of us who were lucky enough to see Sylvestor McCoy play the Fool to Ian McKellen’s Lear during the stage tour, there is a bit of added resonance in their scene together.

Unjolly giants

The scene of the stone-giants has been criticized as well. They occupy four minutes of screen time, putting the Dwarves and Bilbo in extreme danger without having any real link to the plot. The scene’s only causal function is to give Thorin another opportunity to belittle Bilbo. The episode derives from a few brief remarks in the middle of the novel’s description of a terrible thunderstorm the group encounters in the high mountain pass:

When he [Bilbo] peeped out in the lightening-flashes, he saw that across the valley the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them down into the darkness, where they smashed among the trees far below, or splintered into little bits with a bang …. They could hear the giants guffawing and shouting all over the mountainsides.

Douglas Anderson has suggested that by “stone-giants” Tolkien meant a particular type of troll; he mentions the “Stone-trolls of the Westlands” in Appendix F. (See the second edition of The Annotated Hobbit, p. 104.) If so, they would probably only be a little larger than the three trolls in the earlier forest scene. But whatever they are, they are clearly not fighting but playing a game. Moreover, the Dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf (who does not stay behind in Rivendell in the novel) are inside a cave when all this happens. Jackson could have chosen to leave out such a brief references, but he instead turns the creatures into immense giants made of stone, and they are having a flat-out battle rather than a game. I don’t think this was part of an effort to stretch the film into three parts but results from Jackson’s tendency to add or extend action scenes.

Finally, the film considerably lengthens the Goblin-town episode and includes a great deal more combat. In the book, Gandalf quickly kills the Great Goblin and leads the Dwarves and Bilbo in a race for the entrance, with a couple of skirmishes with small groups of Goblins. Again, I don’t think the expansion was created in order to necessitate a third part to the film. This scene had almost certainly been planned and shot well before the decision to ask Warner Bros. for permission to add a third part. Extending the scene is another instance of Jackson’s penchant for big action sequences, and especially battles. I find it a bit overlong myself, but many fans probably like it.

Azog the Defiler of Plots

There is, however, a plotline that does seem to me to be padding. The placement of scenes involving its action damages the narrative rhythm of the film as a whole. The plotline centers around Azog the Defiler, the “Pale Orc” whom Thorin grievously wounded in the battle at Moria (below) and who turns out not to be dead. Instead, he and his band of Orcs, bent on revenge and mounted on wargs (giant wolves) are hunting for Thorin. Making room for this line of action evidently led the filmmakers to cut other scenes that I, and undoubtedly some others, would have preferred to see.

Critics have pointed out a pattern of rescues and respites in both The Hobbit and LOTR. At fairly regular intervals, the characters get into dangerous situations and are rescued, often by someone completely unexpected and even unknown. They then spend a peaceful time with their rescuers before going on to the next challenge. This pattern is so consistent and evident that Ursula K. Le Guin termed it the “rocking-horse gait” of the books.

Obvious examples of down-time are the interludes in Rivendell in both books and the stay in Lothlórien in LOTR. These aren’t dull stretches. They’re occasions for introducing new characters, giving exposition, and bringing a new population with a distinctive culture into the mix of peoples uniting to battle evil. They’re about character development and revelation. They’re about showing off the beauties and wonders that make Middle-earth such an attractive, fully realized fantasy world. And between the battles and chases, they give us, as well as the characters, a bit of respite. This rescue pattern is one of the most basic structures of both of Tolkien’s novels. (I’ve devoted a chapter about it for my book-in-progress.)

The Azog plotline throws off the rescue/respite pattern (which Jackson’s team respected more consistently in LOTR). Worse, it tips the dramaturgical balance of the whole film. First there is the ten-minute troll battle, and then a pause while the group explores the cave. That moment of quiet action lasts only four minutes, and then Radagast shows up. I take this to be the beginning of the next scene of fear and danger, since the Brown Wizard agitatedly launches into a tale about his visit to Dol Guldur, presented as a flashback full of menace and threat. Almost as soon as he finishes, the chase begins. The Radagast scene to the point where the Dwarves’ group hides and Elrond’s Elves drive the Orcs away lasts 9:39 minutes, roughly the same length of time as the trolls scene.

The big Azog battle, in which the Defiler shows up in person and Thorin at last realizes that he’s alive, similarly comes very soon after the end of the huge Goblin-town battle and the concurrent Riddles in the Dark scene. The Goblins/Gollum action lasts 28:37. Once it ends, there’s an all-too-brief scene while the Dwarves and Gandalf think Bilbo has lost or has deserted the group, only for him to show up and explain why he has decided to stay with them (2:53).

Then Azog and his band arrive. The rather straightforward scene in the book, with ordinary Goblins and wolves trapping the company in some fir trees (not on the edge of a cliff), becomes a full-blown battle with Thorin nearly killed and Bilbo prematurely summoning up his submerged courage to save him (11:00). After three viewings, my basic response when the final forest confrontation with Azog begins is, Oh, not again! We’ve just had nearly half an hour of suspense and violence, with considerable variety and impressive filmmaking. The Goblin/Gollum scene should be the high point of the film. To have a shorter battle immediately after it makes the Azog fighting suffer by comparison while undercutting our memory of the earlier, longer one. I don’t think the Azog scenes in general add anything except brute action. Yes, they give Thorin a new revenge motive, but it kicks in only at the end of the film, and he already has plenty of dark motives with his hatred of Smaug and the Elves, particularly Thranduil. Far better to have stuck to Tolkien’s simpler version, ending the film with the group treed by generic Goblins and wolves and then get to the eagles’ rescue as quickly as possible.

The decision to end part 1 by moving away from the group and following a thrush to the Lonely Mountain is, I think, one of the more inspired additions to the story. As the thrush cracks a snail, the sound seemingly carries through the rock and into the cavernous interior, where we see a close view of Smaug’s eye emerging from a great heap of gold and popping open. Smaug is a great villain, unlike Azog, and I suspect his first conversation with Bilbo will be the equal of the Riddles in the Dark scene.

The Azog plotline also introduces a massive coincidence. Just after Balin has told the group the tale of the Moria battle and Gandalf and Balin have exchanged glances suggesting that they do not assume Azog is dead, there’s a cut to Azog’s Orcs appearing and discovering the group. We don’t know how long it has been since the Moria battle, but has this group of hunters been combing Middle-earth for Thorin ever since, while Azog cools his heels at Weathertop waiting for them to report to him? Possibly some sort of motivation for this will be supplied in part 2, but it’s really not a good idea to leave such a flagrant coincidence unexplained within this part.

Doing the numbers

Some have complained about the slow beginning of the film, which, apart from the early flashback to the kingdom of Erebor and city of Dale and their destruction by Smaug, takes place entirely in and around Bilbo’s home, Bag End. As has been endlessly pointed out, Bilbo’s race down the Hill to catch up to the Dwarves starts fully thirty-nine minutes into the film (not counting the open series of logos). To those interested in character and plot–and faithfulness to Tolkien’s book–this makes perfect sense. To those just waiting for the big action scenes, it’s frustrating. But the long exposition has to accomplish something that never challenged Tolkien: differentiating thirteen Dwarves. In the novel, only a few members of the group get any significant amount of characterization, and they mostly remain shadowy background figures whom we don’t have to visualize as individuals. But in a film they’re all there on the screen, and Jackson has to at least give them distinctive appearances. He goes further and assigns them traits, however simple, and on the whole does a good job of it.

To me, apart from the overly coarse behavior of the Dwarves (does Kili really have to be so boorish as to scrape his muddy boots on Bilbo’s furniture?), this early part of the film consists mostly of entertaining, lovely stuff. Kudos to Jackson’s team for keeping not one but both Dwarf songs, which nicely display the contrast of comedy and determination that underlies the group’s nature. The contract-reading scene and Gandalf’s attempts to persuade Bilbo to join the Dwarves’ quest are both entertaining and nicely revealing of Bilbo’s character. I particularly like the quiet conversation between Thorin and Balin, with Balin trying to talk Thorin out of the quest and Thorin revealing his reasons for confidence and hope. (In some ways, this makes little sense, given that it is Balin who later rashly sets out to try to retake Moria and ends up getting himself and his colony of Dwarves killed, but at this point it’s a minor matter.)

Again, though, there’s a problem of balance. So much of this fascinating material is crammed into the opening, and so much of the rest of the film is taken up with dangerous action scenes. It’s notable that the Goblins/Gollum sequence and the final Azog battle add up to 39:37, almost exactly the same length as the opening of the film up to Bilbo’s departure from home. The string of action scenes that begin with the trolls proceeds with only brief letups. A major exception is the Rivendell interlude, with the crucial White Council scene.

Then there’s the Riddles in the Dark, by common consensus the best thing in the film. It’s a relatively quiet and riveting scene, though here, too, Bilbo is clearly in danger from Gollum. Amusing though some of the latter’s antics are, he frequently drops from his Smeagol to his Gollum personality and tries to attack Bilbo. The part after Bilbo puts on the Ring is extremely well done, with him gradually realizing that Gollum can’t see him, and Gollum’s feelings at the loss of the Ring slowly settling from rage to anguish as his big eyes shift and look straight through the invisible Hobbit. Letting Bilbo see Gandalf and the Dwarves escaping and yet not being able to join them because Gollum crouches in the way is a clever touch–a slight improvement on the book, perhaps, since it makes it more plausible that Bilbo can find the group so quickly once he jumps over Gollum and escapes.

A sense of imbalance isn’t just my impression of the film. Timing the individual scenes reveals a remarkable pattern. Without logos or final credits, the film runs about 158 minutes. The mid-point would be roughly 80 minutes into it. The mid-point of a film usually comes at a particularly important dramatic turning point. In this case, at 80:40 minutes, the Elves drive the attacking Orcs away, leaving the Dwarves, Gandalf, and Bilbo safe and free to follow the secret passage into Rivendell. Thus the Rivendell interlude begins the second half.

I’ve timed the individual scenes and divided them up into action (threat, flight, battle) and quiet (conversations, meals, peaceful traveling) scenes. In the first half of the film, there are roughly fifty-one minutes of quiet scenes and 31 minutes of action. In the second half, the pattern is reversed with a surprising precision. The peaceful scenes run a total of 31 minutes, and the action scenes 48 minutes. (These figures don’t exactly add up to 158 minutes, because I’ve rounded off to the nearest half minute–and it’s not easy to time these things to the second!) Moreover, since the Rivendell scene opens the second half (being in the position of the Bag End scene for the first half), there are about 46 minutes of action in the rest of the film, versus 10.5 minutes worth of peaceful scenes. Hence my sense that the film is unbalanced.

Of course we would expect an adventure film to build toward bigger action scenes near the end, but the first part of The Hobbit has come close to squeezing much of its plot-centered scenes toward its beginning and the action ones toward the end. The stone-giants, Goblins/Gollum, and Azog scenes come all in a row. Imagine the Helm’s Deep battle in The Two Towers ending and the filmmakers ramping up another scene of combat. As it is, ending that part with Gollum’s quiet, menacing plotting against Frodo and Sam is far more effective.

Throughout the second half of The Hobbit, there are precious few pauses for simple conversations when the characters are not scared stiff. One seizes upon the few moments of this type with gratitude, as when Bilbo is about to leave the Dwarves and go back to Rivendell and ultimately home. He has a brief exchange with Bofur, who sadly realizes the truth of Bilbo’s statement that the Dwarves have no place where they belong and yet still summons the friendly good nature to wish the Hobbit well. More touching moments like that are needed.

Azog’s collateral damage

My impression is that Azog has muscled his way in by crowding out material of the quiet sort. Still images on the internet and shots in the trailers show moments that should be in this part of the film but are not. McKellen and others have mentioned in interviews that there was to be a flashback to Gandalf putting off fireworks at a Hobbit party long before and meeting the very young Bilbo. A production image of that scene (below) appeared on the internet, but there’s no such moment in the film. Logically, it could only come early on, perhaps in the conversation between Gandalf and Bilbo after dinner, to show the contrast between the adventurous, eager youth and the staid, middle-aged Bilbo who is determined to resist the Tookish side of his nature.

Some of the trailers and TV spots showed Bilbo at Rivendell, walking up some stairs and coming upon the statue holding the shards of Narsil (below). That blade, which we see cutting the Ring off Sauron’s hand in the prologue battle of The Fellowship of the Ring, will be reforged for Aragorn and renamed Anduril in The Return of the King. The idea that Bilbo might see the pieces of that sword so shortly before finding the Ring itself seems a strong addition to the film.

The frame I used as the top illustration in my earlier entry is from a trailer, but it is not in the film either. It showed Bilbo on a bridge at Rivendell, looking up admiringly at the building or landscape. That might have been part of the scene with Narsil, showing Bilbo wandering around Rivendell. There was supposedly going to be a conversation between Elrond and Bilbo, perhaps also part of the same scene with Narsil, but that, too, is missing. I would much rather hear what Elrond had to say to Bilbo, whether about the sword or Rivendell or Elves in general, than sit through yet more of Azog ordering his characterless Orcs around. (The brief scene, cut into the Rivendell interlude, in which one of those Orcs reports failure to Azog and is thrown to a warg to be devoured is particularly gratuitous and unpleasant. Yes, we need to know that Azog is still alive, but that revelation could have come later.)

I hope and expect that the cut scenes and others like them will be restored to their proper places in the extended-version DVD/Blu-ray release, already announced.

All this promising material was cut, evidently to give more room to Azog. What prompted the filmmakers to add him? I have no idea. In a press junket interview about a week before the release of the film last month, Philippa Boyens was asked about scenes added to The Hobbit’s plot. She responded:

I love Azog, Azog the Defiler. Because we just loved that name and he is a character that we just loved that back story and thought we can’t have him be dead, we’re going to keep him alive. So we enjoyed that … bringing him back. And I think we do that quite powerfully, he’s got a good journey to go on.

This baffles me, since ordinarily Boyens has specific, narrative-based justifications for changes made during the adaptation process. But how can one love Azog as a character? In the book, he’s an unusually large Orc who leads the troops at Moria. He has two lines of dialogue that just establish him as nasty, which is what one would expect of any Orc (see the “Durin’s Folk” section of Appendix A of LOTR). He survives the Moria battle depicted in the film, but Tolkien killed him off in that battle in LOTR. He is referred to in passing in The Hobbit novel as Azog the Goblin. The filmmakers have added “the Defiler.” Either the filmmakers thought they needed to pump up a story that already had enough action, or they for some reason did love this bit player of an Orc and let that feeling blind them to the damage he did to their plot. If by “journey” Boyens means a character arc, so far I don’t see any sign of Azog having one. I doubt he’ll reform.

Admittedly, a lot of fans of the film seem to like the Azog scenes. Many of them are probably unfamiliar with the novels and unaware of what is being left out or distorted. But I am far from alone in my opinion. Eric Wecks of Wired has written two short but perceptive commentaries, one on the trailer before he had seen the film and one after seeing the first part. He declares the Azog plotline and particularly the final battle as “wholly unnecessary.” But overall, like me, he admires the film. Many fans aren’t keen on Azog, either. TheOneRing.net has a large cache of fan reviews (1,815 last time I checked) They include one by Sirwen, who, although he or she likes the film and gives it 4.5 out of 5 “Rings,” lists several complaints. Number one is, “I understand that they wanted to have villain since Smaug is essentially MIA until much later in the story, but Azog just seemed random. I am assuming that he will turn out to be working for Sauron, because otherwise it makes no sense why he would wait a century for revenge.” I’m not assuming that Azog will turn out to be working for Sauron, though it’s possible. But Sauron is at this point in hiding, trying to regain physical form–at least, he is in the book. The Nazgûl are also in hiding. How would Sauron know about Thorin’s quest?

The Azog plotline is the only thing in the film that strikes me as truly superfluous. The screenwriters might not see it that way, but it also happens to be the only thing added to the story that has no justification in the appendices or anywhere else in Tolkien’s writing.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the notion of filling out the plot of Tolkien’s novel with other material was a mistake. So far, the importation of Radagast, the White Council, and the Dol Guldur menace work reasonably well and presumably will continue to do so. The scenes that I’ve mentioned as having been cut probably would have worked well, too. But if in the next parts Azog keeps popping up to have yet another attempt at killing Thorin, that plotline will become even more distracting, tedious, and, yes, padded.

[January 19, 2014: To find out where my speculations about the extended edition of Journey and The Desolation of Smaug, see my follow-up entry. Warning: spoilers for both Desolation and the third part, There and Back Again, plus some criticism of what I consider flaws in the film.

LeGuin remarks on the “rocking-horse gait” of Tolkien’s novels in “The Staring Eye,” included a collection of her essays, The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, Susan Wood, ed. (1974; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1979), p. 173.