Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Auteurist on the sound stage

River’s Edge (1987).

DB here:

Last November, Joe Dante brought his brand of manic legerdemain to Madison. This year, his pal and contemporary Tim Hunter visited. Tim talked with us about directing, watched an abundance of movies (from 1930s Wellman classics to Hong Kong gunfests), and oversaw a screening of his 1987 classic River’s Edge. A genial presence and 110% cinephile, Tim was continually stimulating. A blog was a necessity.

Grinding it out

Hunter has made several theatrical features, most famously River’s Edge and The Saint of Fort Washington (1993), but for many years he has also been a free-lance director for top television series, mostly on premium cable. Unlike Dante, whose forte is grotesque comedy and satire, Hunter brings a strong sense of dramatic realism to both movies and television. Over twenty years and more than sixty episodes, he has directed major installments of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Dexter, Deadwood, Law & Order, Cold Case, and Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Apart from efficient craft, he brings to these projects a baby-boomer cinephilia. “I’m an old-school movie brat.” Born in 1947 (about a month before me), he grew up watching classic films. His father was a screenwriter, and in his application interview for Harvard, he won entrance, he thinks, with a rapid-fire analysis of Psycho. As an undergraduate, he ran film societies and made student films. He attended the AFI directors program in 1970 and began teaching film studies at UC-Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, he was writing screenplays. Over the Edge (1979), written with Charlie Haas, was sold to Orion and directed by Jonathan Kaplan. Soon Hunter was able to get backing for Tex (1982), his first directed feature.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a classic Sarrisian cinephile, he understands that today’s television production resembles the old studio system—particularly its B-level. When he takes a job, he joins a series with an established look and feel, its own formulas and conventions. He’s given a fifty-page script to prepare in a week and to shoot in seven to eight days, with each day lasting twelve hours. On the set he must get through at least seven pages a day to come up with 42-44 minutes of engrossing drama.

As a result, the key question—where to put the camera?—has to be settled swiftly. “You need an efficient plan.” Hunter likes to walk the set a day or two before production begins, in order to figure out his setups and actor blocking. The big decision is whether to used a fixed camera or a “moving master,” a tracking shot that reveals the players and the setting, but one that can be interrupted by closer views. He argues that performers prefer sustained shots. “The longer you can play it, the better for the actors.”

To sustain the shots, most dialogue scenes are covered by at least two cameras. That way the scene can be played out in something like real time, with each camera yielding a continuous take centered on one actor or another. The two camera takes can then be cut together into shot/ reverse-shot patterns.

You can see the efficiency of this. The “Perception” episode of Revenge (2012) contains about 780 shots in 42 minutes; of these, at least 350 are shots that repeat setups. A similar proportion can be seen in Hunter’s first episode of Twin Peaks from 1990; about half of the shots repeat earlier camera setups. Because of the time pressure, the director must stage the scenes with adequate coverage from two or more angles.

This can lead to a routine, zero-degree style: Little complex staging, more reliance on actors sitting or standing. Shoot master shot, reverse angles, and singles for reaction shots. Why not use long-held two-shots or fuller framings, as we find in classical Hollywood studio films? Breaking up the camera takes permits the editor to control when we see facial reactions, to tighten the rhythm, and to eliminate fluffed lines. Quick intercutting also supplies that pepped-up pace that, TV practitioners believe, keep viewers glued to the screen.

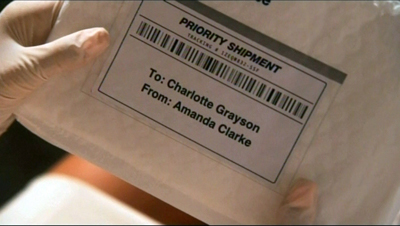

Hunter looks for ways to inject something different, often based on his tastes in classical cinema. For instance, he admires the melodramas of Minnelli and Sirk, so you aren’t surprised to see sudden high or low angles in moments of confrontation. In the “Perception” episode of Revenge, the script gave him a chance for “a Marnie moment.” The heroine Emily has prepared a video that reveals the wealthy Charlotte Grayson’s real parentage. She’s gratified when she sees the maid set the envelope at the foot of the staircase for Charlotte to notice.

Later, overhearing an emotional scene between Charlotte and her father, Emily repents her scheme and tries to retrieve the envelope before Charlotte can find it. Hunter points out that the scene gained suspense when he broke it up into “inserts and moving point-of-view shots.”

The result is a somewhat Hitchcockian byplay, as Emily, startled by the vengeful matriarch Victoria, drops the envelope and tries to keep her from identifying it.

Neatly, Victoria’s face slips into the low-angle view at the very end of the shot, preparing us for her sudden entrance when Emily turns around. And the envelope falling addressee-side down sustains the suspense.

Consciously arty

However much you inject your own emphases, Hunter explained, the director has to assess the visual style of each show and maintain it, so you “tailor your style to the show.” Homicide was 100% handheld, and for that you need a cinematographer who is master of that look. By contrast, Mad Men is more “pictorially precise” and harks back to the studio movies of the 1950s. (Jim Emerson has painstakingly analyzed the felicities of the Mad Men look in several blog entries and video essays.)

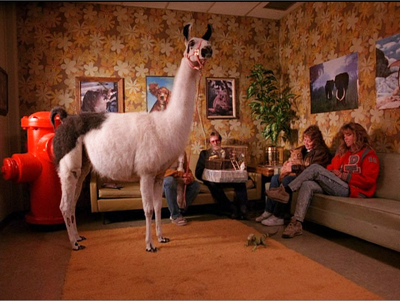

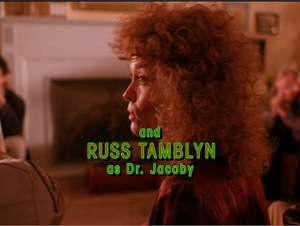

Another pictorially precise show was Twin Peaks, and Hunter’s contribution to the first season (episode four) was one of the most memorable. In that episode we meet Killer Bob’s intimate friend who’s introduced in a shot at once chilling and funny. “Keep your hands where I can see ’em,” snaps Sheriff Harry Truman, and we get this.

At other moments, in an echo of 1940s deep-focus, Hunter uses split-focus diopters to keep foreground and background plane crisp.

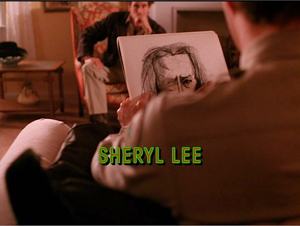

The opening displays the sort of calm assurance that Hunter could bring to a show that was, as he put it, “consciously arty.” A moving master takes us from a photo of the dead Laura to Deputy Andy sketching Killer Bob to Sarah Palmer giving her description; it ends on a framing of Donna, taking it all in uneasily. Donna won’t move or say anything in the scene, but this shot’s ending prepares for both the final shot and her expanding role in the episode’s plot.

In the course of the scene, Hunter supplies closer views anchored by a fixed master setup of the parlor.

When Leland Palmer comes in to say that his wife has had another vision, and when Sarah rises to describe it, we get a long-lens framing, presumably from the B camera aligned with the camera that supplied the master framing.

Sarah’s last gesture in the shot involves extending her palm and recounting her vision of a hand taking out a necklace from under a rock. This strikes Donna with particular force, because she and James have hidden Laura’s necklace the night before. The scene ends with a cut from Sarah to a framing of Donna like that at the end of the first shot. We track in on Donna as she turns away, and the scene ends.

Hunter has talked about getting ideas for this episode from watching Preminger’s Fallen Angel, which handles action in rather confined sets. The wild wall that puts Hunter’s camera behind the sofa allows him to emphasize the proximity of all the characters. Moreover, in this final framing, we can see one virtue of staging the scene for both the static establishing shot and the moving master. In the final moments, Sarah’s gesture can be seen, out of focus, behind Donna and on the frame edge. The surface action of the scene—Truman’s investigation, Sarah’s visions—is counterweighted by the covert action, Donna’s determination to solve the mystery herself.

Stylistic Peaks

Talking with a class in media production, Hunter remarked that story premises—the arresting or puzzling first few scenes—are fairly easy to invent. “Endings are hard.” He stressed that a good story needs a strong climax and resolution. Novels and short stories tolerate diminuendos and offhand closings, but movies need gripping wrapups. Adapting a piece of fiction, Hunter pointed out, may require you to “amp up dramatic tension for a climax.”

As he spoke, I thought about another of his contributions to Twin Peaks, the crucial episode (number 16) in which Leland Palmer, inhabited by Killer Bob, is seized and flung into a holding cell. There Bob-in-Leland rages, seethes, chatters, and laughs demonically. But once Bob abandons him, Leland collapses in agony as he confronts the fact that he has killed his daughter. As if this weren’t dramatic enough, it takes place during a deluge from the building’s fire sprinklers, set off by a cigarette in another room.

Hunter’s direction shows how stark imagery can enhance the actors’ performances. A kind of cleansing spray pours down on Palmer as he confesses, sobbing. Agent Cooper, the Dream Detective, holds him as if cradling a child. There are only four primary setups over about four minutes.

Instead of cutting quickly, Hunter lets the shots play out to emphasize the dialogue and especially the performances: Ray Wise as Leland, terrified that he may be damned, and Kyle MacLachlan as Cooper, whose daffy mysticism finds its reason for being as he guides the dying murderer “toward the light” and a reunion with his dead Laura (top of this section). The scene’s intensity is shaded by the perverse erotic overtones of Leland/Bob’s unholy passion for young girls and the moment when Leland, recalling being seduced by Bob, moans, “He came inside me.”

Minnelli, who set the climax of Some Came Running in a luminous carnival and in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse gave us the image of a man gripping his father in a soaking thunderstorm (above), might well have admired Hunter’s handling. It’s at once tactful (letting the actors act) and flamboyant (the shadows, the torrent of water). In Hunter’s hands Twin Peaks’ New Age quirkiness is cast off and the climax plunges us into pure, traumatic melodrama.

Meaning in the madness

Hunter shot River’s Edge in thirty days at a cost of $1.7 million. Built around Crispin Glover (suddenly hot after Back to the Future) and featuring the young Keanu Reeves and Ione Skye Leitch, it had early buzz. But it alienated the industry. Variety‘s 1986 Montreal festival review called it “an unusually downbeat and depressing youth pic.” By odd coincidence, that review ran alongside a review of Blue Velvet (“a must for buffs and seekers of the latest hot thing”), and both films were shot by Frederick Elmes.

“None of my features made any money,” Hunter says today. But River’s Edge has become a classic of 1980s independent cinema, an anti-John-Hughes teenpic and a sobering look at how kids really live.

Its unglamorized treatment of high-school sex and drugs goes along with a bleak but nonjudgmental account of a moral blank at the center of kids’ lives. A young man has strangled his girlfriend Jamie, and he takes his pals out to see the body, twice. At first none of them reports the crime, and one, the perpetually hyper Layne, urges everyone to keep quiet. Two in the posse have qualms. Clarissa considers calling the police, and Matt in fact does. In the course of a day, a night, and the following day–a sort of grunge-and-amphetamine American Graffiti time frame—the kids circulate through their neighborhoods settling scores and responding to the threat of an investigation. The one adult in sync with the kids is Feck, a former biker and now drug dealer, who claims to have killed a woman years before.

At first glance the film looks wholly moralizing, with a 60s-era teacher trying to stir his class to political consciousness and a hardened cop squeezing Matt to admit something, anything about the crime. The stoned indifference of the kids to the murder of one of their friends–they don’t cry at her funeral–would seem to indict them as hopeless. But the adults driven to exasperation are hardly role models. The teacher is self-righteous, the cop bullying. Matt’s mother and her live-in boyfriend seem as concerned for their own lives, and their cache of weed, as they are for the kids. And the future? Tim, Matt’s little brother, is the first to spot the body but shrugs it off, and he wantonly drowns his sister’s doll. Eventually Tim will try to kill Matt.

Again, Feck sort of understands. His own drug-driven mania enables him to identify with the kids to whom he gives pot for free. But even he is startled by the hollowness of their lives. He confesses a despairing love for the woman he killed, but he sees no depth in the boy Samson, who strangled Jamie “because she was talking shit.” Feck’s madness is born of passion, Samson’s of annoyance and indifference (“She was all right”). Most of the men treat women, whom Layne calls “evil,” as disposable, and the motif of the dead girl–Jamie, the sister’s doll, and Feck’s inflatable sex doll–brings out the parallels between three generations. This is as bleak a vision of American life as we’ve had in contemporary cinema, and the kids’ amorality, festering in an old foothill community, can’t even be blamed on suburbia.

My friend JJ Murphy has written a superb analysis of River’s Edge, with attention to the craft of Neal Jimenez’s script. Here I want just to show how Hunter, working with more elbow room than in the TV projects, enriches his plot with a tightly shaped, classical style. Two scenes–not climaxes–will help me.

Matt’s brother Tim is playing a video game in the Stop-Go, and the clerk is dimly visible at the counter behind him. Then Samson enters in the background. This concise framing is the scene’s establishing shot, introducing all three of the scene’s characters.

One maxim of filmmaking is: Who is the scene’s anchoring character? Through whose awareness is the viewer experiencing the action? Here, it’s Tim. As Samson goes to the cooler and snaps out a can of beer, Tim watches as he lumbers down the aisle to the front counter.

Samson confronts the clerk, who asks for his identification. He refuses to give it and a quarrel starts, observed by Tim.

Now Hunter uses another classical technique. Like Hitchcock, he gives us something to listen to and something different to watch. As the quarrel at the counter grows more heated offscreen, we see Tim slip to the cooler and swipe two beers.

Actually, Hunter doesn’t show us a close-up of the beers, as we might expect. We see only Tim fumbling and his coat getting baggier. But we know he’s stealing, partly because he checks the security mirror.

Tim makes his way to the front of the store and steps out while the quarrel continues. This introduces a level of suspense, while also characterizing Tim as already a practiced shoplifter.

After a tug-of-war over the beer can, Samson angrily relents and makes his way out. In the parking lot Tim disappears and then reappears, perched on the hood of Samson’s car. The initial front-counter framing has “primed” Samson’s car as an innocuous part of the background in the earlier shot, so that it can be used now. Deep-space staging allows you to quietly set up elements to be activated later in the scene.

Samson leaves the shop scowling and goes to the driver’s seat, where he bends down as if seeing something.

Tidiness: Now we know that Tim’s momentary absence took place because he slipped the beers into Samson’s car. Hunter could have cut in a close view of two beer cans left on the seat, but instead he sustains the shot and lets us see Samson bring one into view, open it, and take a big swig. The beer swiping becomes no big deal, nothing out of the ordinary (as a close-up would have hinted). This sort of swift, small-scale flow of information keeps us waiting for more developments. Those come when Tim peers into the window and says, “Don’t mention it.” He adds, “I saw you this morning.” Samson: “Yeah?” Pause. Tim: “Got any dope?”

The whole scene establishes the tribal amorality and cohesion of the young crew. Tim takes the murder in stride. He swipes the beer not just to do a good turn to his brother’s friend but also in hope of scoring weed.

Samson is at first unresponsive but then, as if to acknowledge he owes the kid, tells him to get in. Tim loads his bike into the back seat. They will go see Feck.

This is the first time we’ve seen the exterior of the Stop-Go. Another film would have given us the conventional establishing gesture, a shot of the front, sign and all, as John pulled up. But in the interests of economy and forging an attachment to Tim, I think, the film starts the scene inside and gives us the exterior only when we need to see it, along with the physical action of loading the bike. Later, we’ll see the Stop-Go from comparable angles and we’ll be able to reorient ourselves.

The use of depth, the careful timing of character movements through the frame, and the overall economy of the sequence stand in contrast to the more heavily cut string of singles we get in “Perception” and even in the Twin Peaks episodes. Comparatively few setups are repeated. There’s no standard shot/ reverse-shot, and no over-the-shoulders. (Imagine how a conventional TV director would have cut up the confrontation with the clerk.) Hunter has constructed his eleven shots so that each one presents a compact body of information, and the shots interlock neatly.

The same conciseness and flexible use of depth can be seen when we return to the Stop-Go during the night scenes. Again, there’s no exterior establishing shot. Matt has come to buy beer at the shop, and there Samson and Feck find him. Hunter could have used the earlier counter setup to save time in shooting, but he recalibrates. A judicious over-the-shoulder framing kicks off this four-shot scene.

Matt is trying to buy a six-pack after hours, and the same blue-vested clerk forbids him. A reverse angle shows Samson coming in, followed by Feck with his sex doll Ellie.

After telling Matt to take the beer, Samson pulls Feck’s revolver. Matt is stunned. In the background, out of focus, Feck is making his way to the cooler.

At Samson’s insistence, Matt grabs the beer (and pays for it). As he edges out of the shot, rack focus to Feck turning to ask the clerk: “Do you have Bud in bottles?” End of scene.

Same setting as the first scene above, and something like the same trigger for conflict: the kids want beer, against the rules. And we have the same geography/ geometry, with the scene organized around the beer cooler, the counter, and the aisle between them. But Hunter has activated the space in a significantly different way. With a close shot he stresses Samson at the moment when he pulls the revolver, and he pays the scene off on a semi-comic note that doesn’t underplay Samson’s casual sociopathy.

The long lenses, the marked rack-focus, and other techniques are more characteristic of post-1960 filmmaking than of the studio years. But the demand for concise visual storytelling, layered with echoes of earlier character gestures, recasting previous dialogues and conflicts through new angles and cutting patterns–these are time-honored strategies. Hunter, like many another movie brat, learned the lessons of classical Hollywood moviemaking. Even in scenes of fairly low dramatic pressure like these, he shows the flexibility and richness of that tradition when it’s put to new uses.

Thanks to Tim Hunter for coming to Madison, Jim Healy for arranging the visit, Eric Hoyt for letting me sit in on his class, and Roch Gersbach for all his assistance.

The Mad Men mystique is engagingly chronicled in Matt Zoller Seitz’s columns in New York Magazine.

The best accounts of television aesthetics are those by Jeremy Butler: Television Style (Routledge, 2010) and Television: Critical Methods and Applications (4th ed., Routledge, 2012).

The review of River’s Edge can be found in Variety (3 Sept. 1986), p. 16. For a little anticipatory buzz, see “Sanford-Pillsbury Readying Pic on Teen Murder for Fall Release,” Variety (2 July 1986), p. 27. Roger Ebert’s review captures the wider response to the film at the time, adding: “This is the best analytical film about a crime since The Onion Field and In Cold Blood.”

Why don’t I write about television more often? The answer is here. For more on how post-1960 directors continued the classic studio tradition, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Dennis Hopper as Feck in River’s Edge.

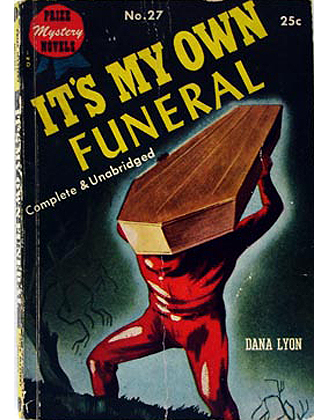

I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading

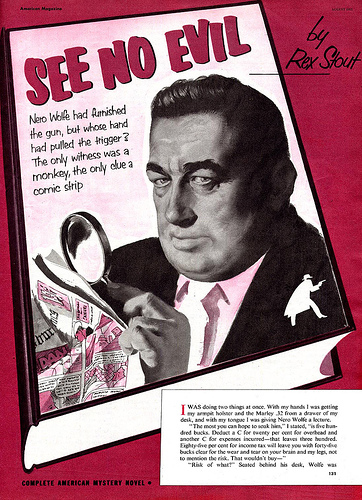

Thornton Utz illustration for Rex Stout novella from American Magazine, 1951. Obtained from the excellent site Today’s Inspiration.

DB here:

Over the next few months, I’ll be traveling with a talk on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. The ideas I’ll propose are destined for a book about narrative norms during that period. Mystery fiction is important to that lecture, but I don’t have room there to supply much background about the relevant conventions. So I’m sketching in this background here, for people who might hear the talk somewhere or who might just be curious. Consider this as another experiment on the blog, using the web to supplement a lecture.

Although the lecture is mostly about cinema, this entry is mostly about novels and plays. But I’ll mention film here and there, and you’ll notice that some of the books and plays I mention were adapted for the screen.

A mega-genre

The first half of the twentieth century saw an explosive expansion in genres built around mystery and suspense. The most obvious genre is the detective story. In the wake of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, a great many writers developed and elaborated on the idea of the master sleuth, the genius of observation and reason. Central to this tradition was the puzzle that could be solved by careful noting of clues and meticulous reasoning about them, supplemented by a good knowledge of human nature or local customs. The author needs to keep us in the dark about both the crime and the detective’s chain of reasoning; hence point-of-view figures like Watson, who can be appropriately confounded, relay the detective’s cryptic hints, and marvel at the final revelations.

Readers quickly learned the conventions, so writers had to innovate constantly. Sometimes a writer was original on more than one front. For example, R. Austin Freeman created a revamped Holmes surrogate in a scientific criminologist, Dr. Thorndyke, while also creating a new narrative structure: that of the “inverted” tale. The first section of the story follows the criminal who commits the crime; the second part details how Thorndyke, using evidence and inference, solves it.

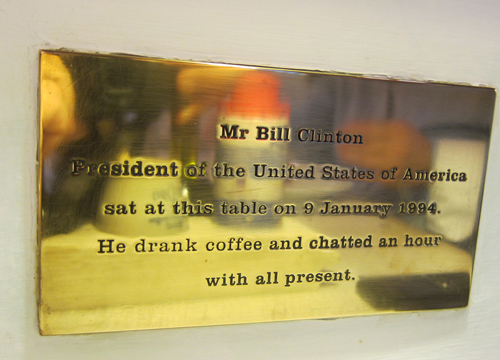

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

It’s hard for us to conceive today how massively popular these puzzle books were. Van Dine’s first novels were bestsellers comparable to Jonathan Kellerman’s books today. Just as important, the detective story was granted quasi-literary status. Magazines and newspapers that wouldn’t dream of reviewing romance or adventure fiction devoted space to detective stories, sometimes even setting up separate columns or sections for reviews. It was believed, rightly or wrongly, that whodunits had a more intellectual readership than Westerns or science fiction.

At about the same time, according to the standard account, a counter-current was swelling. In the pulp magazines of the 1920s, the “hard-boiled” detective emerged as an alternative to the master sleuth. The prototype is Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op in stories through the late 1920s, to be followed by Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930). Strikingly, Hammett and other hard-boiled writers don’t wholly abandon the basic idea of solving a mystery through some sort of reasoning. The differences have to do with realism. The crimes, however, aren’t usually fantastical ones like the Locked-Room problem; the killings tend to be mundane. If the white-glove detective’s only real opponent is a master criminal like Professor Moriarty, the hard-boiled detective faces off against organized crime, or at least people who commit murder outside upper-crust parlors and remote country houses. Clues are less likely to be physical, and more psychological, depending on bits of behavior or flashes of temperament. Raymond Chandler and others took the hard-boiled initiative into the 1940s, and the brute detective, who solves crimes with boldness, insolence, and a pair of fists, occasionally supplemented by torture, found bestseller status in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1947) and subsequent novels.

I’d argue that some writers could blend the master-mind detective and the tough guy. Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason was one such hybrid, though leaning closer to the hard-boiled model. Rex Stout solved the problem neatly by creating two detectives: the insolent legman Archie Goodwin serves as a hard-boiled Watson to sedentary Nero Wolfe. But on the whole, historians tend to assume that the Holmesian superman and the puzzle-dominated plot were swept aside by the rise of the tough-guy detective solving mysteries that were grittier and more “realistic” than what had preoccupied Golden Age writers.

Two other major developments are typically highlighted by historians. There was the police procedural, perhaps initiated by Lawrence Treat’s V as in Victim (1945), and explored with great ingenuity in the novels of Ed McBain. There was also what Julian Symons has called the “crime novel,” the story of psychological suspense, with Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950) serving as a good example. Both of these genres have proven popular to this day (CSI as a procedural, the films of De Palma as psychological thrillers).

A tree and its branches

Like most histories hovering fairly far above the ground, the standard account traces some main contours of the landscape but misses some interesting byways. By taking Doyle as the prototype, this account tends to identify mystery fiction with detective plots in the Holmes mold. But mysteries come up in other forms.

The standard account has trouble accommodating the development of the spy genre, which often involves solving a crime, but less through abstract reasoning than by putting the hero through hairbreadth adventures. Think for instance of The 39 Steps, both the 1915 novel and the 1935 film.

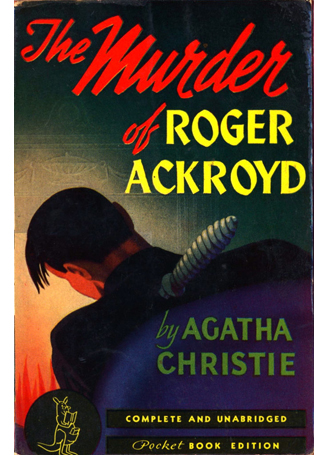

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

Jane Eyre is an obvious source for Rinehart and her successors, and perhaps the association with women’s writing in general made historians and practitioners of the Golden Age mock the revived Gothic as too feminine, too far removed from the bluff masculine camaraderie of 221 B Baker Street. The Gothicists had their revenge: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) outsold every other mystery novel of its time and sustained a cycle of new sensation novels by Mabel Seeley (The Chuckling Fingers, 1941), Charlotte Armstrong (The Chocolate Cobweb, 1948), and Hilda Lawrence (The Pavilion, 1946). The genre is maintained today by Mary Higgins Clark, Nicci French, and many other writers.

So mystery and detection formed a broader tradition than literary historians sometimes acknowledge. Another marginal form was the suspense thriller. Again, we can point to a woman: Marie Belloc Lowndes, author of The Lodger (1913). An early instance of the serial-killer plot, it’s also a tour de force of point-of-view; unlike the film versions, it restricts itself quite rigorously to what certain secondary characters know. Choices about narration and viewpoint are no less crucial to the thriller than to the Great Detective tradition.

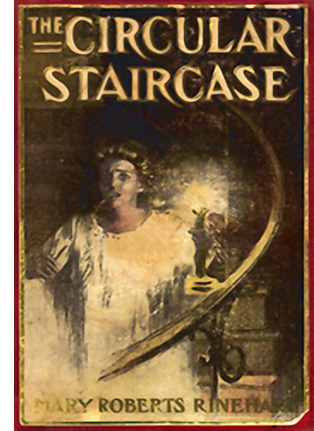

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

I personally am convinced that the days of the old crime puzzle pure and simple, relying entirely upon plot, and without any added attractions of character, style, or even humour, are, if not numbered, at any rate in the hands of the auditors. . . The puzzle element will no doubt remain, but it will become a puzzle of character rather than apuzzle of time, place, motive, and opportunity. The question will be not “Who killed the old man in the bathroom?” but “What on earth induced X, of all people, to kill the old man in the bathroom?”

Cox went on to test his premises in Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932). Both trace the schemes of wife-killers, but the first novel is told from the husband’s standpoint and the second from the wife’s. The latter book opens:

Some women give birth to murderers, some go to bed with them, and some marry them. Lina Aysgarth had lived with her husband for nearly eight years before she realized that she was married to a murderer.

There followed other domestic-crime psychological novels, notably Richard Hull’s The Murder of My Aunt (1934).

Sometimes suspense thrillers have a solid mystery at their center; this is common when the protagonist is a potential victim. Other thriller plots in effect present the first half of a Freeman “inverted” story, concentrating on the criminal’s execution of a crime and the resulting efforts to escape punishment. Both possibilities were on display in British stage plays of the 1920s and 1930s. In a sense Cox was beaten to the punch by Rope (1929), Blackmail (1929), and Payment Deferred (1931). Later examples are Night Must Fall (1935) and the woman-in-peril dramas Kind Lady (1935) and Gaslight (1938). Many of these plays were made into films.

The novel of suspense really came into its own in the 1940s, when it started to incorporate abnormal psychology. Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gaslight, provided an influential novel as well, Hangover Square (1941). Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis, who mined this nightmarish vein, achieved posthumous cult status because, again, of the spell of film noir. Other suspenseful students of mania were Dorothy B. Hughes (In a Lonely Place, 1947), Charlotte Armstrong (The Unsuspected, 1945; Mischief, 1951, filmed as Don’t Bother to Knock), and Elizabeth Sanxay Holding (The Blank Wall, 1947, source of The Reckless Moment). Chandler called Sanxay Holding “the top suspense writer of them all.” We shouldn’t ignore the influence of Simenon’s romans durs, which were being translated and respectfully reviewed throughout the war years.

Yet another new wrinkle on the mystery thriller was the genre of courtroom novels. The Bellamy Trial (1927), which begins when the trial does and restricts itself almost completely to what transpires in the courtroom, popularized the pattern. Stage plays of the 1920s adopted the pattern too. The format proved irresistible for early talkies, as in adaptations of The Bellamy Trial (1929) and Thru Different Eyes (1929) and the radio-inspired Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932). Cox, who seemed to try his hand at every current trend, gave his own twist to the juridical mystery in Trial and Error (1937).

Most of these novels focused on the trial proceedings from the perspective of the defendant, but a few concentrated on those sitting in judgment. The Jury (1935), by Gerald William Bullett, characterizes the jurors singly before they gather and then shows the trial from their standpoints before taking us into the jury room to hear the arguments. Bullett’s novel finds an equally engrossing complement in Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve (1940). There were also Eden Philpotts’ The Jury (1927) and George Goodchild and C. E. Bechhofer Roberts’ The Jury Disagree (1934). We can immediately recognize the teleplay and film Twelve Angry Men as an updating of this minor line.

Merging and markets

The family tree of mystery, then, grew many branches in the 1920s and 1930s—the pure puzzle, the hard-boiled investigation, the spy story, the revised Gothic or sensation novel, and the suspense thriller, often of a psychological cast. Unsurprisingly, the genres began to mingle. Cox was perhaps the writer most interested in hybrids, but John Dickson Carr tried his hand at the thriller as well (The Burning Court, 1937), as did Agatha Christie in And Then There Were None (aka Ten Little Indians, 1940).

The process sped up during the 1940s, when writers began blending crime-solving with psychological suspense. We can get a sense of how the protagonist-in-peril side of the thriller melded smoothly with the enigma-based investigation by looking at the jacket copy of a fairly ordinary entry, Alarum and Excursion (1944):

Bit by bit, a gesture here, a sound there, Nick Matheny pieced together the awesome puzzle of the accident that had sent him to a sanitarium with traumatic amnesia. One by one he reconstructs, he probes the cirumstances of the explosion in his factory, the disappearance of his weak but beloved son, his wife’s strange attitude toward the new management of the business, and the status of the new synthetic fuel formula, which was so urgently needed.

As the dreadful picture unfolds itself, Nick escapes from the sanitarium to ferret out the sinister changes that have disrupted his business and brought his active life to an abrupt close.

Virginia Perdue, author of He Fell Down Dead, skillfully handles the difficult flash backs in this unusual psychological drama. There are many scenes where the tricks of thought, the tenseness of apprehension, the visions through the deserted streets of blacked-out memory poignantly work their stealth upon the mind of the reader.

Alarum and Excursion wasn’t adapted into a film, but reading this spoiler-filled jacket copy you can easily imagine the movie.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

As mystery genres proliferated, their popularity soared. Contrary to what historians imply, the puzzle novel with a brilliant sleuth was far from defunct. Christie’s Poirot and Sayers’ Wimsey retained their fame into the 1940s, significantly outselling Hammett and Chandler. Ellery Queen’s novels are not read much today, so it’s hard to imagine a time when over a million copies of them were in print. More generally, the public’s appetite for mystery novels and radio plays was intense. In 1940, 40 % of all titles published were mysteries, and in 1945, an average four radio shows devoted to mystery were broadcast every day, each drawing about ten million listeners.

Small wonder, then, that Hollywood came calling. Curiously, the master detectives popular with the reading public wound up in B-film series (Charlie Chan, Ellery Queen) or remained unexploited in the 40s (Nero Wolfe, Perry Mason). What came to the fore, as being more suitable for the dynamic medium of film, were the hard-boiled heroes of Hammett and Chandler. Because the rise of hard-boiled adaptations fed clearly into film noir, they have attracted the most attention. But mutating alongside them, and becoming at least as lucrative, were the films shaped by the updated Gothic and the psychological thriller. Variety noticed the trend in fall of 1944.

Plain murder as a film frightener is passé. Been done too long in the same old way. Theatregoers actually can yawn in the face of manslaughter as it’s been perpetrated for the whodunits during the past year or more. . . . The newer type of horror pictures, invested with psychological implications, deal with mental states rather than melodramatic events. . . . The typical tale in the new genre crawls with living horror, is eerie with something impending, and socks its suspense thrill well along toward the middle of the story instead of doing the crime victim in at the beginning and then building a whodunit and a detective quiz as the element of suspense.

The piece doesn’t respect today’s genre distinctions. Apart from using the term “horror” in a way we wouldn’t, the author lumps together suspense thrillers like The Lodger, Hangover Square, The Uninvited, and The Suspect; the Gothic Gaslight (“a perfect example of the new approach”); and spy thrillers The Mask of Dimitrios and The Ministry of Fear. Even Jane Eyre is included, without irony. (Surprisingly, Double Indemnity from spring 1944 isn’t mentioned.) Still, the article acknowledges that mystery had strong audience appeal and that while the classic whodunit had had its day on the movie screen, films could be given new energy by other literary trends.

Mystery as artifice

Mystery is the only genre I know that makes narrative strategies as such central to its identity. A musical, a Western, or a science-fiction saga can be presented in linear fashion, telling us everything step by step, and still retain a genre identity. But a mystery plot can’t be presented straightforwardly. The writer must manipulate plot structure and narration to some degree.

A mysterious situation or plot action is one whose causes are to some degree unknown. In the detective formula, both refined and hard-boiled: A person has been murdered; what led up to it? In the Gothic: There are sinister goings-on in the house; what’s causing them? In the suspense thriller: Someone wants to harm me; who and why? (And will I escape?) To generate mysteries, the plot-maker must suppress key information. That can be done by opening late in the story (say, after the crime has been committed), by employing flashbacks (often launched from a climactic moment), or by restricting the range of knowledge (via a Watson or a string of eyewitnesses). More subtle options involve ellipses, such as those in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and the diary portion of The Beast Must Die (1938).

At the level of prose style, clues can be buried in descriptions or offhand remarks. The narration can creatively mislead us from the start, in the title (The Murder of My Aunt, The Murderer Is a Fox) or the diabolical opening sentence of Carr’s “The House in Goblin Wood.” And sometimes you get pure showing off. The first chapter of The Rynox Murder Mystery (1931) is entitled “Epilogue,” and the last chapter is entitled “The Prologue.” In addition, the book is broken not into parts and chapters but “reels” and “sequences,” a device creating a small meta-mystery (gratuitously, so far as I can tell.)

Given the proliferation and mixing of genres and the constant demand for innovation (echoed in Variety’s crack about things “being done too long in the same old way”), 1940s mystery writers were pressed to find new storytelling gimmicks. Everything had not been done, at least not yet. Historians of the detective story routinely praise the ingenuity of Christie and company in the 1930s, but the 1940s saw a positively baroque expansion of options. A dead detective pursues the investigation as a ghost. Another wakes up trapped in a coffin and starts telling us how he got there. Pat McGerr distinguished her work by replacing the question Whodunit? with others, such as: We know who’s guilty, but who’s been murdered?

Given the proliferation and mixing of genres and the constant demand for innovation (echoed in Variety’s crack about things “being done too long in the same old way”), 1940s mystery writers were pressed to find new storytelling gimmicks. Everything had not been done, at least not yet. Historians of the detective story routinely praise the ingenuity of Christie and company in the 1930s, but the 1940s saw a positively baroque expansion of options. A dead detective pursues the investigation as a ghost. Another wakes up trapped in a coffin and starts telling us how he got there. Pat McGerr distinguished her work by replacing the question Whodunit? with others, such as: We know who’s guilty, but who’s been murdered?

In the suspense mode as well, we find efforts to create novelty at the level of narration. With the emerging interest in psychoanalysis, the thriller began to probe the protagonist’s inner life and hidden traumas, producing not only the hallucinatory visions of Woolrich and Goodis but the crazy-lady divagations seen in The Snake Pit (1947), Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948), and Patricia Highsmith’s early short story, “The Heroine” (1945). As in the purer tale of detection, a great deal depended on feints and fake-outs at the level of the prose. The cleverly misleading narration of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) turns on the use of a pronoun.

Hollywood filmmakers borrowed plentifully from the new genres, particularly the psychological thrillers that could appeal to women. Significantly, Rinehart’s pioneering 1908 novel was remade as The Spiral Staircase (1945), and Warner Brothers redid Collins’ classic Woman in White in 1948. Moreover, I think, filmmakers tried to find cinematic counterparts for the genre’s restricted narration, dream and fantasy passages, misleading exposition, and shrewd ellipses (e.g., Possessed, 1947; Mildred Pierce, 1945; Fallen Angel, 1945). The diversity of mystery fiction inspired Hollywood writers and directors to create a Golden Age of the mystery film, and the innovations of the period left a legacy for filmmakers ever since.

These genres had a wider impact too. That’s what I’ll concentrate on in my presentation, “I Love a Mystery: Narrative Innovation in 1940s Hollywood.”

The two major histories of mystery fiction are Howard Haycraft, Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (1941) and Julian Symons, Mortal Consequences: A History from the Detective Story to the Crime Novel (1972). Both are very much worth reading, as is Leroy Lad Panek’s idiosyncratic An Introduction to the Detective Story. The best study of the 1920s-1930s puzzle tradition is Panek’s Watteau’s Shepherds: The Detective Novel in Britain 1914-1940. On A. B. Cox, see Malcolm J. Turnbull, Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox.

The Variety article I quote bears the misleading title, “New Trend in Horror Pix; Laugh with the Horror.” It’s in the issue of 16 October 1944, p. 143.

Unlike The Rynox Murder Mystery, Cameron McCabe’s Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) blends moviemaking and murder in a thoroughgoing, albeit wacko, fashion.

Other entries on this blog have dealt with some of my mystery favorites, especially Ellery Queen and Rex Stout.

P. S. 11 June: Mystery expert Mike Grost has kindly reminded me of his encyclopedic site, A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection. By discussing authors both famous and forgotten, he displays the great diversity of this mega-genre.

TINKER TAILOR once more: Tradecraft

DB here:

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy has to be counted a success ($64 million worldwide so far), and it may have brought new attention to John le Carré’s writing. The fact that some websites and Twitter feeds lured readers to my entry on the film (and thanks to all) suggests that people can enjoy a film even though major aspects of the plot escape them. Everybody loves a mystery, right?

Regular readers won’t be surprised to learn that I had originally written something longer about le Carré’s narrative strategies generally. Out of common human decency I cut the entry in half and focused on the film. But seeing the interest in what I’d posted, I thought that there might be enough hard-core readers who’d want to go down the rabbit hole again.

So one more post, which reflects a little more on the film, while arguing that le Carré’s development as a novelist offers a fascinating example of a writer trying out various methods of storytelling. Ideally, you should read this after reading my first post. The next three sections don’t spill any secrets, but if you want to avoid spoilers, stop at the section called “Burrowing.”

Going to ground

During the 1970s le Carré seems to me to have reinvented the dense, almost digressive plotting we associate with the nineteenth century British novel. A little narrative theory helps us understand his ongoing exploration of storytelling technique.

We’re used to thinking that a plot presents one or two major characters moving through the world. That movement yields adventures in the broadest sense: encounters with others, experiences that illuminate some aspect of life, conflicts both inner and outer. Our mental prototype of a plot, certainly in mainstream films, features a protagonist (or a couple) accompanied by lesser figures who become allies, helpers, lovers, rivals, and enemies.

Le Carré’s first novels accord with our prototype, with the addition of those old standbys Mystery And Intrigue. Call for the Dead (1961) and A Murder of Quality (1962) are mostly straightforward detective stories. Although George Smiley is a secret agent, he’s forced to investigate crimes. Accordingly, he goes from place to place, suspect to suspect, and hears out their explanations and alibis. With The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963), le Carré moves closer to an adventure plot, as we follow a protagonist in a linear succession of encounters. As is common in the genre, concealed information is sprung on us at various points, forcing us to recast what we thought we knew.

It takes a mind as odd as that of Viktor Shklovsky, the great literary theorist, to point out that we can think of any longish narrative as the intersection among many stories. He believed that as a form the novel developed out of assemblies of shorter tales. He pointed to The 1001 Arabian Nights and The Decameron as examples of this sort of compilation—long works built out of collected stories, enclosed within a bigger storytelling situation.

When the novel became a distinct genre, Shklovsky thought, it continued this tradition. In essence, each novel makes a long story out of several shorter stories. But unlike what happens in the compilation format, the stories become connected to one another. Character A figures not only in her own plot, but in Character B’s. This tends to hide the fact that separate stories are nestled within the overall architecture.

Besides connecting all the sub-stories, the ordinary novel makes some of them very minor. Our simpler prototype relies on suppressing or compressing all the other story lines except the one involving the protagonist. Our protagonist meets lots of people, but some are given no background, others a bit, and still others a fair amount, but nobody’s story can override the hero’s.

Shklovsky asks us to rethink our idea of the standard novel. It becomes not a straight-line path but a tangle of virtual tales that has been radically chopped down and ironed out. All the latent stories might be intriguing enough to sustain a plot in themselves, but for immediate purposes they must be subordinated to the fate of those creatures we call protagonists. In effect, Shklovsky suggests that every narrative can be thought of as an undernourished network narrative.

In a tale of mystery and detection of course, hidden backstories of some of the characters come to light gradually. But severe selectivity still reigns, because the backstories bear on the protagonist’s main goal: solving the mystery. When Smiley cracks a murder case or agent Leamas realizes that he has been deceived by his superiors, we understand other characters’ lives in a new way, but they don’t steal the stage from our hero.

Still, Shklovsky notes, some storytellers have realized that secondary characters can claim the spotlight as well. At the limit, they can furnish new narratives, as in Wicked and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Henry Jenkins’ idea of transmedia storytelling exemplifies this idea: the ally in one tale can become the hero of another, perhaps on another media platform. But of course nineteenth-century novelists aimed to do the same thing within a single tale, building elaborate plots that would give us an ample sense of how the lives of many characters converge through chance or common purpose. Our Mutual Friend, Pot-Bouille, and War and Peace try to accommodate a great many stories within their wide compass.

I think that with the novel Tinker, Tailor le Carré decided to try this option, to give the spy novel—typically the province of the teasing linear plot exemplified in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold—the sense of a panorama surveying many characters’ lives and perspectives and, still more broadly, the institutions that they serve.

Backchanneling

But there’s a problem here: How to expand your plot to do justice to many characters’ backstories and sidestories? Again Shklovsky provides useful hints, and le Carré tried many of the options he proposes.

Shklovsky suggests that stories can be integrated in two basic ways. One is through framing. You the writer set a self-contained tale, or several tales, inside a bigger one. This is exemplified by The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales, as in the films that Pasolini made from these classic works. We can see this option at work in a movie like Dead of Night (1945), in which guests at a country house party swap stories of the morbid and bizarre. Actually, le Carré tried this. The Secret Pilgrim (1990), is virtually a collection of short stories framed by an aged spy listening to Smiley lecture at MI6’s training school.

Another option is what Shklovsky calls “threading,” the principle that traces the consecutive adventures of a protagonist. This is the prototype I’ve already mentioned. But Shklovsky suggests that by keeping the protagonist thread you can still expand the framed tales. In Don Quixote, the adventures of the Knight and Sancho Panza hold their own interest, but they surround a string of embedded tales told by the people they meet. And sometimes those embedded tales are pretty long.

It seems to me that le Carré sought ways in which he could expand his embedded tales without losing the main thread. For example, his novel following The Spy…, The Looking Glass War (1965), splits the protagonist function up into three characters, their parallelism stressed by the section titles: “Taylor’s Run,” “Avery’s Run,” and “Leiser’s Run.” There is an overarching rhythm to the action, but we have three distinct protagonists. It’s as if the author is rehearsing, on a smaller scale, the shifting viewpoints that he will exploit in his longer fictions. The tripled protagonist also allows le Carré to present different standpoints on that center of spying operations MI 6, known as the Circus.

The following book, A Small Town in Germany (1968), is a return to a single protagonist and a straight detective plot, but now the mystery focuses on the bureaucracy behind espionage. Alan Turner, an embittered spy in the Leamas mold, is searching not only for a staff member missing from the British embassy in Bonn but also for some damaging files that have vanished. The drab routines of sorting, checking, and managing information become the object of scrutiny, and Her Majesty’s civil servants are prime suspects. Le Carré had found a way to put burrowing at the center of his plot.

After these efforts, in which Smiley barely appears, le Carré might well have felt ready to test his talents on a broader canvas. First came The Naïve and Sentimental Lover (1971), a satiric psychological novel about a businessman who becomes entranced by a novelist and his wife. The book, which runs over 400 pages, shows le Carré’s eagerness to stretch out. Just as important, I suspect, is its value as a laboratory for narrative experiments. Descriptions swell, and inner states are reported in detail. Instead of a roaming point of view, there are deep plunges into the main character’s mind and senses through stream of consciousness, free indirect discourse, and a curiously omniscient voice, sometimes pitying and sometimes jocular. Compare the driving scenes in the opening lines of two books.

“Why don’t you get out and walk? I would if I were your age. Quicker than sitting with this scum.”

“I’ll be all right,” said Cork, the Albino coding clerk, and looked anxiously at the older man in the driving seat beside him.

(A Small Town in Germany)

Cassidy drove contentedly through the evening sunlight, his face as close to the windshield as the safety belt allowed, his foot alternating diffidently between accelerator and brake as he scanned the narrow lane for unseen hazards. Beside him on the passenger seat, carefully folded into a plastic envelope, lay an Ordnance Survey map of central Somerset. . . . For the attention of Mr. Aldo Cassidy ran the deferential inscription; for Aldo was his first name. He drove, as always, with the greatest concentration, and now and then he hummed to himself with that furtive sincerity common to the tone-deaf.

(The Naïve and Sentimental Lover)

The style seems to me unsure, but clearly the writer is moving beyond terseness toward something more enveloping and commentative.

Returning to the espionage genre, le Carré hit upon another way to fill a big canvas. He resurrected that old formula, the supreme master-mind criminal pitted against our beleagured hero. The master spy isn’t Mabuse or Fu Manchu but the Russian Karla, snug in Kremlin Centre, and George Smiley’s efforts to flush him out are chronicled in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), and Smiley’s People (1979). The mass-market omnibus edition of these runs to nearly a thousand densely packed pages. How did our author manage plots on this new scale?

Wrangling

Chekhov says that if a story tells us that there is a gun on the wall, then subsequently that gun ought to shoot. . . In a mystery novel, however, the gun that hangs on the wall does not fire. Another gun shoots instead.

Viktor Shklovsky

Some expansions are pretty evident. The Quest for Karla trilogy introduces many new characters, mostly people who staff the Circus or who are involved with the institution of espionage: from secretaries and “scalphunters,” the lonely and low-down agents assigned to menial bits of spying, to the very top, such as the Minister who oversees MI6 and Lacon the pliant civil servant overseeing the Circus. Some of these characters are in turn given private lives, with friends and lovers. The connections ramify.

In addition, there are the civilians whose lives are touched by the Cold War chessgame. In The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, that demographic was represented by Liz Gold, Leamas’ lover. But in the Karla trilogy we get a panoply of more or less innocent figures who are pulled into webs of plot and counterplot. And here le Carré does something quite shrewd.

He tends to start the novel with these characters, people at the very edge of the web. Smiley’s People opens with an unassuming Russian émigrée living in Paris. She’s confronted by a Soviet agent telling her she might be permitted to see her long-lost daughter. What does that have to do with Smiley’s cleaning the Circus stables after the mole scandal, or Smiley’s loss of power after the Jerry Westerby misadventure? Positing enigmas at two or three degrees of separation, working inward across the web, le Carré lets the reader gradually sense the lines of force that lead inexorably to the principals.

So le Carré grows his book not merely by expanding his cast. He finds a new balance between thread structure and framed stories. In Smiley’s People, perhaps the most orthodox entry in the trilogy, Smiley investigates the death of an émigré Soviet general, and this entails a fairly standard detective plot. The novelty comes in the fact that the participants Smiley questions are former agents whom he ran, or colleagues retired from the Circus—his people. And what they tell him isn’t rendered in compressed dialogue or summary. Their recollections spread out luxuriantly, claiming considerable interest in their own right, sometimes with only slight points of contact with the main plot, sometimes burying clues that Smiley must dig out.

More intricate is The Honourable Schoolboy, the longest entry in the Karla trilogy. It has two main threads: Jerry Westerby’s efforts to trace money flowing from Moscow to Hong Kong, and Smiley’s struggle to rebuild the Circus. The plot encapsulates the two main types of spy fiction—indeed, the two types that le Carré had already mastered in his earlier books. While Jerry’s plot is suspenseful adventure stuff, Smiley’s plot is inquiry-oriented, like that in Ambler’s classic Mask of Dimitrios (1939). To stretch the canvas on a still bigger frame, le Carré makes Smiley pass investigative assignments to other Circus personnel, like Connie Sachs and Doc di Salis (who get characterized in detail). Indeed, both main lines of action are filled out with rich and lengthy sub-stories. We can study the tradecraft of old Craw, majestic spy-journalist; the puzzling past of Lizzie Worthington, Drake Ko’s mistress; and the enigmas around her lover Ricardo, either dead or flying heedlessly through an Asia in flames.

The Honourable Schoolboy also has a more layered narration than its predecessors. It switches point of view constantly, in the process virtually promoting Peter Guillam to the rank of Smiley’s Watson. Most striking is the plot’s ultimate narrating framework, a sort of institutional memory serving as recording angel. Instead of the all-knowing, somewhat condescending voice of The Naïve and Sentimental Lover, this narration is brisk and brusque. It defends Smiley against those in the intelligence community who, through shortsightedness or malice, misjudged his decisions.

It has been laid at Smiley’s door more than once since the curtain was rung down on the Dolphin case that now was the moment when George should have gone back to Sam Collins and hit him hard and straight just where it hurt. George could have cut a lot of corners that way, say the knowing; he could have saved vital time.

They are talking simplistic nonsense.

This opinionated, godlike narrating agency is never identified. It’s one of the many signs that in the Karla books le Carré is reviving conventions of the triple-decker novel. And so he did; he bid to become our Dickens. (The larger-than-life father-son duo of A Perfect Spy is perhaps his most extravagant exercise in this vein.)

He echoes Wilkie Collins too. For mystery, never far from Dickens’ concern, is central to Collins and le Carré. Sustaining the reader’s interest through mystery seems not as important for our highbrow novelists now; it’s the province of “genre fiction.” But many of the canonical works of fiction and drama turn on secrets that are hinted at, then dramatically exposed (not only Oedipus and Hamlet but works by Henry James, Ibsen, Conrad, O’Neill, Faulkner). On the first page of Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov thinks, “Why am I going there now? Am I capable of that? Is that serious?” The question of that that keeps us reading. You can argue that the modernist novel, with its fascination with time-juggling and stream of consciousness, found a sort of equivalent for the secrets, deceptions, and puzzles that drive classic tales. In any event, during the first decade of le Carré’s career, he began to explore the ways in which embedded stories can blossom into mysteries.

Burrowing

In my original entry, I didn’t straighten out the plot of Tinker Tailor, but now, as the film nears the end of its theatrical run, I’ll tell the novel’s tale straight. Skip if you don’t want it all ironed out.

Bill Haydon, working for British intelligence, is in the pay of Moscow Centre and its head, Karla. He has been passing information to the Russians for years, but Control, the head of the Circus, is starting to get suspicious. He believes that one of his five top men is a mole. Karla entices Control into sending an agent, Jim Prideaux, to meet a Czech general supposedly going to defect. This leads to a spectacular failure—Prideaux is shot and captured—and allows Karla to install an ambitious dunce, Percy Alleline, in Control’s position.

Haydon is the best and the brightest, the flower of English manhood. Suave, easygoing, with an Oxbridge artistic flair, he is as debonair as Smiley is brooding and inscrutable. Haydon has strained his friendship with Smiley by conducting a brief affair with Smiley’s wife Ann, but that episode was initiated by Karla to make Smiley reluctant to suspect Bill of bigger crimes. Haydon has already tempted Percy with the promise of a double agent, a cultural attaché in London called Polyakov. Through Polyakov Karla feeds the Circus trivia, mixed with bits of good information, to the gratification of Alleline’s inner circle—Haydon, Roy Bland, and Toby Esterhase—as well as Oliver Lacon and the Minister overseeing the bureaucracy. And the Americans approve.

Upon Control’s forced retirement, his team is abandoned and he dies a short time later. A permanently damaged Jim Prideaux is brought back to a new life as French teacher at a minor boy’s school. Smiley retires, while his wife Ann leaves to take up a string of love affairs.

But when a raffish field agent, Ricki Tarr, reports on good authority that there is a mole at the very top of the Circus, Lacon asks Smiley to investigate sub rosa. Smiley installs himself in a shabby hotel and with the help of a youngish colleague, Peter Guillam, and an old friend, Inspector Mendel, he starts patiently scouring the records. Following in Control’s footsteps, Smiley discovers disparities, missing documents, and incompatible testimony. Eventually he is able to pressure Toby into revealing the location of the safe house where Alleline’s cadre meets Polyakov.

By inducing Tarr to send a message galvanizing the Circus’ top brass, Smiley forces the traitor to hurry to meet Polyakov at their usual place. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mendel record Bill Haydon’s incriminating conversation and play it back to the embarrassment of the inner circle. There remains a long epilogue, in which Bill, in detention, confides in Smiley and seems to have no regrets about sending his closest friend Jim Prideaux into a trap and months of torture. Jim has discovered the treachery of his dearest friend and, sneaking into the compound, kills Haydon. While Smiley, now occupying Control’s seat of power, goes to the countryside for a possible reunion with Ann, Jim returns to his school, the object of the boys’ adoration but also a morose, haunted man.

I’ve tried to synopsize the action as a thread, in Shklovsky’s sense, but I can’t do justice to the novel’s exfoliating plotlines. We’ve seen that a detective story basically presents the sleuth going from person to person, asking questions and getting information. Since Smiley is the protagonist, much of what I’ve traced has to be discovered through testimony or flashbacks. As Shklovsky remarks, any mystery in a plot involves some play with time, either ellipsis (what happens in the gap?) or rearranged order (hiding crucial causes) or a late point of attack (so that we must go back to reconstruct why things are as they are).

But your straight-line Q & A investigation can be pretty plodding. Check for yourself by trying to read one of the “classic” detective stories by S. S. Van Dine. Forced to present official reports and characters’ recollections, le Carré skillfully expands those into robust, extensive stories of their own, filled out with characterization, detail, and atmosphere. The recording-angel narrator moves easily from reporting the interrogations to summarizing past action and then to full-blown scenes rendered from the viewpoint of the witnesses.

As in the later books of the trilogy, le Carré’s point of entry is oblique. Instead of starting with Smiley, principal investigator, it starts with Jim Prideaux’s enigmatic arrival at the boys’ school, and even that is presented at one remove, through the vantage point of Bill Roach, aka Jumbo, a hapless “new boy” at the school. Only after that do we meet Smiley, hailed by the obnoxious gossip Roddy Martindale (a convenient expository device) who chats about the usurpation at the Circus. Soon Smiley is summoned to Lacon’s home, where he and Peter learn Ricki Tarr’s story of spying in Hong Kong and falling in love with Irina, the wife of a KGB spy. It’s she that tells him of the mole in the Circus.

Tarr’s tale is the first embedded story, running four chapters. Once Smiley takes the assignment, relatively little happens in the present. His investigation carries him to his old Russia expert, Connie Sachs, and she recounts another block of information, about how her suspicions of Polyakov led her to be sacked from the Circus. Once Smiley is back at his hotel, he starts his reading, and for five chapters we get a big chunk of the past, including Smiley’s discovery of Bill’s affair with Ann. Smiley’s homework is interrupted by a suspenseful string of scenes involving Peter’s smuggling crucial files out of the Circus.

Another embedded story soon follows: Over dinner Smiley tells Peter of his only meeting with Karla, many years before. Then, pursuing yet another clue, Smiley questions Sam Collins, the man on Circus duty the night Jim was ambushed. As in any good detective story, Bill Haydon seems to have an alibi (he heard the news at his club) and acts resolutely un-guilty, bursting into the Circus to take command and demand the return of his old pal Jim. Sam’s embedded story to Smiley is followed by others, from the man who drove Jim into Czechoslovakia and from Jerry Westerby, who heard rumors that the military were waiting for Prideaux. Getting ever closer to the fateful incident that set the whole shuddering machine into motion, Smiley finally hears Jim’s own version of what happened to him that night and in the months afterward.

After so many extended stories—recounted by witnesses, filtered through hearsay, written up in bureaucratic files, commented upon by the recording angel—the plot launches into forward motion. Smiley and his colleagues set their trap, and there’s a suspenseful set-piece spanning two chapters. Le Carré alternates among Tarr in Paris, Mendel watching affairs at the Circus, and Smiley waiting in the safe house to trap the traitor. There follows an equally crosscut epilogue, with Bill and Smiley’s confrontations alternating with vignettes of other characters—including a young woman, introduced for the first time, who seems to have borne a child by Bill. The book concludes with Smiley, waiting to meet Ann and meditating on what drove Bill.

Scalphunter

In adapting a novel for the screen there is a natural temptation to dramatize the information supplied by narrative description in the original text by turning it into dialogue, but this is generally to be resisted. Where possible it should be translated into action, gesture, imagery. Much of it can be dispensed with altogether.

David Lodge

Imagine trying to adapt this monster! Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of flashbacks, long tales framed by Smiley’s investigation. The seven-installment BBC series, scripted by Arthur Hopwood, took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, in Jim’s embedded story told to Smiley. The series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia; Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the plot for nearly 23 minutes. Yet this construction does obliquely retain the portmanteau quality of the novel’s concept, in which sustained blocks of action are allowed to stretch and breathe.

Soon, as in the novel, the TV series gives us Ricki Tarr’s story of his affair with Irina, presented as a discrete flashback. Then Smiley’s trawl through the files is supplemented by his visits to Connie and others. Sometimes their recollections are dramatized in flashbacks, other times we simply watch them tell Smiley of them. Fortunately for the viewer, there are also scenes of Smiley bringing Peter up to date, and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. Because the BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, this sort of backtracking was necessary. And since Hopcraft had several hours to fill, the plotting could be somewhat spacious. Nonetheless, the book’s oscillating time scheme was somewhat flattened out, and the block construction—main thread interrupted by inset stories—was compressed. The inset tales didn’t expand to their novelistic dimensions.

The Tinker Tailor film, of course, had to be much more squeezed down. I mentioned in the earlier entry that the screenwriters compared their structure to a mosaic, and I followed this out in my discussion of how the narration was elliptical and fragmentary, leaving out redundancies that are usually required in popular film. Many scenes are both spacious and laconic. The rhythm is slow, and we’re given time to see and hear everything; but that “everything” might be only a voice dimly overheard, or a doorbell, or an image that gives one piece of information.

Take an instance I didn’t pick out in the original post. In order to steal a file, Peter Guillam has arranged for Mendel to call him, pretending to be a garage mechanic.

The call provides a pretext for Guillam’s retrieving his bag from the security officer, so he can slip the file inside.

George Formby’s music-hall tune “Mr. Wu’s a Window Cleaner Now” is playing on the garage radio. It’s carried down the phone line to the call-screener at the Circus, who murmurs along with it as the call is recorded.

After the tense meeting with the Circus cadre, Guillam has apparently sneaked the file out. But on the staircase an offscreen voice softly sings “Mr. Wu” before we see the source, not Guillam but Roy Bland. He descends slightly ahead of Guillam.

Guillam follows right behind, pausing and looking off nervously as Bland passes through the foreground.

The empty stretch of the staircase shot allows us to think that it’s Guillam offscreen, humming the tune he heard on the line, so it’s a surprise when Bland appears. We realize that he must have heard the call, or the recording.

Another film would have cut away during Guillam’s maneuver to show Bland and his colleagues listening to Peter’s fake conversation. That would have dialed up the suspense: Will they detect the trick? Instead, showing the lady on the phone lets us know that the call is being recorded. Only retrospectively—and by a single piece of information that slips by—do we realize that Bland has heard the conversation. Guillam is being watched closely. There’s a meta-message here too: By humming the tune, Bland lets Guillam know he’s overheard the call. Bland’s casual feint fits with the intimidation of Guillam that began when he was called into Percy’s meeting.

In all, the moment’s oblique, ricocheting transmission of story information could easily be missed. (In the book, it’s Bill who waylays Guillam and asks if he’s seeing Smiley. “Guillam’s world, which was showing signs till then of steadying to a sensible pace, plunged violently.”) The film’s script and direction have followed David Lodge’s suggestion of translating Peter’s sudden panic into images and sounds, but more laconic ones than we usually find.

More broadly, the film’s stinginess about supplying information extends to its protagonist. As I suggested in the first post, Smiley doesn’t just solve mysteries—he is one. What does he want? Oldman’s dry, impassive performance bottles the shrewdness, sternness, and pain that Guinness let leak out in the series. It still seems to me that the film’s Smiley is playing a waiting game; even the “Aha!” moment near the climax, when he seems to have hit upon something, proves to be obscure.

After the montage parades the suspects and shows the shifting train tracks outside Smiley’s dingy hotel, the narration doesn’t present the classic giveaway clue or blinding insight. Immediately we see Smiley, by force of will, bullying his superiors and Toby into giving him the information he needs to trap the mole . . . whose identity isn’t pinned down until the ambush. Smiley’s emotion bursts forth only once more, in his confrontation in Haydon’s cell. After a slight confirmatory smile (Prideaux, Smiley surmises, “knew deep down it was you all along”), Smiley asks if Karla ever considered letting Bill take over Control’s post.

Bill, angry: “I’m not his bloody office boy!”

Smiley, almost roaring, but with expression unchanged: “What are you then, Bill?”

Bill, after a pause, in a subdued, strangled voice: “I’m someone who has made his mark.”

Smiley exhales, the burst of energy gone, and turns slightly aside.

Smiley’s outburst here is his most vehement utterance in the movie. By the epilogue, Smiley, still unsmiling, has assumed his place as Control’s successor.

Mole-hunters