Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

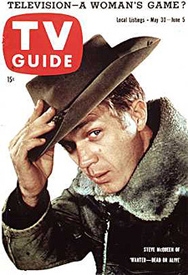

Take it from a boomer: TV will break your heart

DB here:

Every so often someone will ask Kristin and me: “Why don’t you write about television?” This is usually followed by something like:

”You’re interested in narrative. The most exciting narrative experiments are going on in TV, not film.”

”You’re interested in visual experimentation. The most exciting developments in visuals are in TV.”

”TV is where the audience is.” Or “TV is where the culture is.”

”Film is borrowing a lot from TV, and producers and directors are crossing over.”

We might answer by saying we don’t watch any TV, but that would be a fib. Like everybody, we watch some TV. For us, it’s cable news commentary, The Simpsons, and Turner Classic Movies.

Truth be told, we have caught up with some programs on DVD. We watched the British and the US versions of The Office and enjoyed both (though the American version, no surprise, makes the characters more lovable). Kristin watched The Sopranos’ first season for a particular project. For similar purposes I watched and enjoyed Moonlighting and some Michael Mann TV material. Intrigued by the formal premise of 24, I dipped into the first season, but I found it visually so wretched I couldn’t continue. I got through four seasons of The Wire on DVD, largely because of the Pelecanos connection, but I found it over-hyped. It seemed to me a sturdy policeman’s-lot procedural, but rather fragmented and uninspiringly shot.

That’s it for the last three decades. No real-time monitoring of episodic TV (we haven’t seen Lost or Mad Men or the latest HBO sensations) and none of the reality shows or the music shows or even comedy like Colbert or Jon Stewart.

So we aren’t plugged in to the TV flow. Americans currently log over four and a half hours a day in front of the tube, so clearly we’re derelict in our duty. As Clay Shirky points out in Cognitive Surplus, TV viewing is Americans’ unpaid second job.

But why don’t I start following episodic TV? The answer is simple. I’ve been there. I was a TV kid before I was a film wonk. And I can assure you that watching TV leads to painful places—frustration, anger, sorrow. All you’re left with is nostalgia.

Commitment problems

I see the difference between films and TV shows this way. A movie demands little of you, a TV series demands a lot. Film asks only for casual interest, TV demands commitment. To follow a show week after week, even on a DVR, is to invest a large part of your life. Going to a movie demands three or four hours (travel time included).

Whether a movie is good or bad, at least it’s over pretty soon. If a TV show hooks you, prepare for many long-term ups and downs—weak episodes, strong ones, mediocre ones. Favorite actors leave or die, and replacements are seldom as good as the originals. A new character may be charming or annoying. An intriguing hero may accumulate distracting sidekicks. Plots take weird turns, sometimes dillydallying for months. All this can drag on for years.

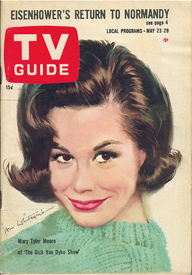

Of course TV-philes enjoy this slow samba. They point out, rightly, that living through the years along with the characters, watching them change in something like real time, brings them closer to us. Who doesn’t appreciate the way Mary Tyler Moore evolved into something like a feminist before America’s eyes? As early as 1952, the sagacious media critic Gilbert Seldes pointed out that intellectuals who thought that TV was plot-dependent were wrong.

It is natural that the actual plot of a single self-contained episode should be comparatively unimportant. . . . The very limitations of the style leads its creators to develop characters of considerable depth, to create dramatic conflict out of the interaction of people rather than out of an artificial juxtaposition of events. As television is a prime medium for transmitting character, this is all to the good (Writing for Television, pp. 115-116)

We get to know TV characters with an informal intimacy that is quite different from the way we relate to the somewhat outsize personalities that fill the movie screen. We learn TV characters’ pasts, their hobbies, their relations with kin, and all the other things that movies strip away unless they’re related to the plot’s through-line.

Having been lured by intriguing people more or less like us, you keep watching. Once you’re committed, however, there is trouble on the horizon. There are two possible outcomes. The series keeps up its quality and maintains your loyalty and offers you years of enjoyment. Then it is canceled. This is outrageous. You have lost some friends. Alternatively, the series declines in quality, and this makes you unhappy. You may drift away. Either way, your devotion has been spit upon.

It’s true that there is a third possibility. You might die before the series ends. How comforting is that?

With film you’re in and you’re out and you go on with your life. TV is like a long relationship that ends abruptly or wistfully. One way or another, TV will break your heart.

TV brat

Trust me, I’ve been there. Unlike most film nerds, I wasn’t a heavy moviegoer as a child. Living on a farm, I could get to movies only rarely. But my parents bought a TV quite early. So I grew up, if that’s the right phrase, on the box.

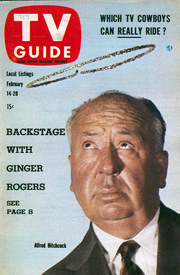

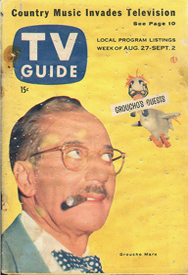

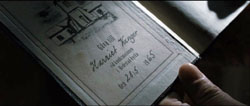

Childhood was spent with Howdy Doody (1947-1960) and Captain Video (1949-1955) and Your Hit Parade (1950-1959) and Jack Benny (1950-1965) and Burns and Allen (1950-1958) and Groucho (You Bet Your Life, 1950-1961) and Dragnet (1951-1959) and Disneyland (1954-2008) and The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1959). With adolescence came Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965) and Maverick (1957-1962) and Ernie Kovacs (in syndication) and Naked City (1958-1963) and Hennesey (1959-1962) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) and Route 66 (1960-1964) and The Defenders (1961-1965) and East Side, West Side (1963-1964).

Some of the last few titles I’ve mentioned evoke particularly fond feelings in me. At a crucial phase of my life, they presented models of what the adult world might be.

For one thing, adults had an easy eloquence. Some of these shows seem overwritten by today’s standards, but actually they brought to television a sensitivity to language that seems rare in popular media now. Bret Maverick had a smooth line of patter, and even racketeers on Naked City could find the words. Dragnet‘s dialogue is remembered as absurdly laconic, but actually it showed that very short speeches could carry a thrill. At the other extreme were the soliloquys in Route 66. One that sticks in my mind came from a daughter, torn between love and exasperation, saying how touched she was when her father called one of her simpleton boyfriends “uncomplicated.” (The line was modeled on something said by Faulkner, I think.) I don’t recall characters insulting one another as much as they do nowadays, and of course obscenity and body humor were yet to come. At that point, TV relied so much on language that it might be considered illustrated radio.

Second, these shows made heroes of adults who were reflective and idealistic. They mused on social problems and thought their positions through. The father-son lawyers of The Defenders often disagreed about the moral choices their clients had made, and as a result you saw the different ways in which legal cases shaped people’s lives and public policy. Even a cop show like Naked City was less about fights and chases than it was about the causes, and costs, of crime.

Third, adults were empathic. This was partly, I suppose, because I was drawn to liberal TV; but I think it’s striking that my favorite dramatic shows showed professionals committed not to billable hours but to helping other people.

El segundo pueblo

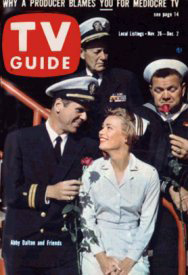

These qualities were epitomized in Hennesey. The continuing cast was small. Chick Hennesey (Jackie Cooper) is a navy doctor in his mid-thirties. His irascible superior Captain Shafer, is played by Roscoe Karns, bringer of dirty fun in 1930s and 1940s movies (“Shapely’s my name, shapely’s my game”). Nurse Martha Hale (Abby Dalton) serves as a romantic interest for Hennesey, and Max Bronski (Henry Kulky) is a dispensary assistant; both are vivid characters in their own right. A few others pop in occasionally, notably the rich eccentric dentist Harvey Spencer Blair III (played with eerie passivity by James Komack).

The series began as a situation comedy, but soon it became an early instance of the “dramedy”—the TV equivalent of sentimental comedy. In this classic genre, moderately grave problems cannot shake the essential concord of human relations. The tonal mixture makes a laugh track distracting; Hennesey‘s was eventually phased out.

The series was created and largely written by Don McGuire, who modeled his protagonist on a doctor he admired. Hennesey is l’homme moyen sensual, a man of no great ambitions or grand passions. He smokes cigarettes (Kent was a sponsor) but, surprisingly, doesn’t drink alcohol. He served in the army when very young (at Guadalcanal), went to UCLA medical school, and was drafted into the navy. Neither a career officer nor an ordinary doctor, he is more at home with enlisted men than the brass.

Hennesey isn’t a dramatic blank, but his virtues are quiet ones. He simply wants to help people get over the daily bumps in the road. He stammers when bullied by someone more aggressive, but sooner or later he quietly stands his ground. When he has a chance to do something decisive, he does it without fanfare. In the pilot episode, he has to override Shafer in order to extricate a man’s arm from a flywheel. But afterward he is likely to wonder whether he did the right thing. He often confesses his fears and weaknesses. Hennesey is a prototype, far in advance, of the caring, sharing male. He is, as Martha sometimes tells him, nice; but that sounds too soft. He is simply decent.

The plot often calls on him to confront people far more harsh and self-centered than he is. Often Captain Shafer, playing the narrative role of Arbitrary Lawgiver, assigns Henessey to unpleasant duties, like dealing with a lady psychologist who wants to find out why men join the navy. Often Henessey has to help men and women adjust to navy life, or to tell them that they are too unhealthy to continue. Sometimes he reminds arrogant doctors why they took up the calling. He also encounters civilians with problems that impinge on his own life. Going home to meet the doctor who inspired his career choice, he finds a bitter widower. In other episodes he simply observes someone else rising to the occasion. A bumbling helicopter pilot is a figure of fun until, behind the scenes, he risks his life to save a girl with appendicitis.

Everything about the series is modest: the level of the performances (only Shafer raises his voice), the accidents and digressions that deflect the plot, the cheap sets and recycled exterior shots, the jaunty hornpipe score that becomes an earworm on first hearing. But all these things enhance that TV-specific sense of a comfortable world with its familiar routines and unspoken bonds of teasing affection.

The show illustrates one of the virtues of TV of the time: talk. Characters emit single lines or even single words at a pace recalling that of the 1930s screwball comedies. Nurse Hale is the fastest, Shafer comes next, and Hennesey is left to play catch-up. In one episode, Shafer has just learned he’s going to be a grandfather, and he leaves the office euphoric. But Martha is a beat ahead.

Hennesey: I betcha this has him in a good mood for weeks.

Martha: For what?

Hennesey: For days.

Martha: Do you want to bet that within thirty seconds he’ll be in a bad mood?

Hennesey: No, that’s ridiculous.

Martha: Is it?

Hennesey: Of course. What could possibly get him upset in—?

Shafer returns, frowning.

Shafer: I just thought of something.

Martha: His first grandchild will be born overseas.

Shafer: Right.

Martha (to Chick): Think you’re playing with kids, huh?

The exchange, including blocking, takes nineteen seconds. It’s conventional, I suppose, but its brisk conviction modeled for one thirteen-year-old the possibility that adults are alert to each moment and enjoy rapid-fire sparring with their friends.

Harvey Spencer Blair III has more highfalutin rhetoric. In a 1961 episode, he declares his plan to run for mayor of San Diego.

Harvey: My election will see the rise of little people to positions of consequence, the molding of our future cultures, the era of a new world. Join with me, my dear, in crossing the New Frontier.

Martha: Leave the petition with me, Dr. Kennedy.

Harvey: I revel in the comparison.

Here even the double takes are modest. Characters react with a frown or a tilted chin or a widening of the eyes or a slight shake of the head. There can be verbal double-takes as well, mixed in with overlapping lines in the His Girl Friday/ Moonlighting manner. At the start of a 1961 episode, Martha enters the infirmary. Henessey is at the desk and Max is filing folders.

Without looking up, Chick says what he thinks Nurse Hale should say.

Hennesey: Morning, Max. Morning, doctor. Sorry I’m late.

Martha: I am not.

Hennesey (looking up): You’re not? It’s ten minutes after eight–

Martha (overlapping): I mean I’m not sorry. I have a very good excuse.

Hennesey: You had a run in your mascara?

Martha: I had to stop and talk to the senior nurse.

Max: Did you get it?

Martha: Yes.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: Good, I’m glad.

Martha: Thank you, Max.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: I bet it’ll be nice up there.

Martha: I hope so—

Hennesey (overlapping): Up where?

Max: If it isn’t too cold.

Hennesey: Oh, no, it can’t be too cold, it’s only cold up there in August—that is, if the winds from the equator don’t –Look, you two, don’t you think it’s only fair that if you discuss something in front of a third party, you might just—

Martha: A run in my mascara?

Nobody I knew talked like this, but why not talk like this? It would make life more lively. Backchat, I’ve learned over the years, can get you in trouble; life isn’t a TV show. But I still think that repartee, especially featuring stichomythia, is one of the pleasures of being a grownup. So too are the catchphrases we weave into our chitchat. The Hennesey tag I enjoyed was “El segundo pueblo,” uttered oracularly at a moment of crisis, and always translated with a different, incorrect meaning. My own life would feature motifs like “A meatloaf as big as the Ritz” (undergrad days), “Kitchen hot enough for you yet?” (grad school), and “If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it” (professorial years).

Being a film wonk, I can’t rewatch episodes without noting that those directed by McGuire have some flair. His staging fits the characters’ unassuming demeanor, providing a deft simplicity we don’t find in modern movies. This is doorknob cinema; scenes start when somebody enters a room. And people in the foreground respond to others coming in behind them.

The faster the gab, the slower the cutting, but extended takes can refresh the image by moving actors around. In one scene, Harvey, still planning to run for mayor, is slated for a court-martial. He enters to get the news. His somewhat zombified gait contrasts with Hennesey’s peppy, arm-swinging stride, usually on exhibit during the opening credits. (I learned things about grown-up walking styles too.)

As the shot goes on, Harvey gets the news he’s headed for the brig. Shafer and Hennesey gloat, but in the foreground, Martha suspects that Harvey’s got an ace up his sleeve.

When Harvey says he can’t attend his hearing, Martha lifts her cup: “Here comes the voodoo.”

Harvey reminds his colleagues that he’s due to be discharged from the service before the hearing date. The ensemble responds by regrouping, with Martha and Shafer trading places in the foreground and Hennesey slinking off.

When everybody has assumed a new position, Harvey volunteers to re-up, causing Shafer to shudder.

As Martha sits and Hennesey comes forward, Harvey produces some tickets for his campaign rally, at which Clifton Webb (yes, go figure) will be speaking. Interestingly, Jackie Cooper stays a bit out of sight, preparing for a later stage of the shot.

Harvey leaves, and Shafer’s attention turns to Hennesey as the person to be blamed.

Soon we are seeing characters moving in depth again as Martha gives a typical head-shake in the foreground.

The shot exploits principles of 1940s Hollywood depth staging, as did many of the filmed programs of the period. (The Defenders is particularly rich in this regard.) Simple and sharp, McGuire’s scene is more skilful than anything I saw yesterday in The Expendables.

Chick and Martha got married in the last episode of the series, in May of 1962. I would never see these people again, except in re-runs and syndication. In fact, all my favorite programs were cancelled during my high-school years. I set out for college in summer 1965, disabused of my love for TV. Ahead lay cinema, which would never betray me.

Of course watching a TV series on DVD changes the dynamic of week-in, week-out absorption; but the rhythm of real-time viewing seems to me one of TV’s artistic resources. Besides, wading through a whole series on DVD is still a hell of a commitment.

Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television is an original and imaginative study of conventions that still hold sway. He’s especially astute on how the differences in conditions of reception (film, public; TV, domestic) shape creative choices. Another entry on this site discusses Seldes as a critic of modern media.

On the idea that we are especially susceptible to popular culture in our early teens, see our earlier entry here.

Extensive collections of some of my favorite shows, like Reginald Rose’s The Defenders and David Susskind’s East Side, West Side are available for study in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Nat Hiken, a Milwaukee boy, also generously left us a cache of Bilkos and Car 54s.

Hennesey, once rerun on cable channels, has evidently never been published on DVD. Gray-market discs offer a few fugitive episodes, recycled from VHS, kept alive by others with an affection for the program. The most complete information I’ve found on the series is in David C. Tucker’s Lost Laughs of ’50s and ’60s Television: Thirty Sitcoms that Faded Off the Screen (McFarland, 2010), pp. 47-53. A list of episodes and broadcast dates is here.

For more on one staging technique that McGuire uses, you can visit our post on The Cross. See also Jim Emerson’s outstanding analysis of composition and cutting in Mad Men at scanners; the sequence he studies is reminiscent of mine. The best guide to analyzing TV technique is Jeremy Butler’s landmark Television Style.

George C. Scott in East Side, West Side. Stephen Bowie’s Classic TV History site provides a detailed study of this series.

PS 10 September 2010: Believe it or not, I hadn’t read A. O. Scott’s praise of current TV before I wrote this, but his thoughts develop the sort of ideas I mention at the start of this entry.

PPS 10 September 2010, later: Jason Mittell completely understood this entry. If you think that I’m saying TV isn’t worth studying , please read Jason’s careful piece. (In fact, you could count my discussion of Hennesey as an argument for studying TV!)

PPPS 11 September 2010: In my roll-call of TV that Kristin and I watched, how could I have forgotten our devotion to Twin Peaks (1990-1991)? I think I neglected to mention it because we didn’t consider of a piece with ordinary TV. We wanted to follow David Lynch’s career, and we considered the show an extension of his movies. Besides, the series showed the symptoms I diagnosed I mentioned above: episodes fluctuated in quality, and although I liked the later part of the second season better than many people did, its finale was a letdown for me too. For Kristin’s thoughts on Twin Peaks as TV’s equivalent to “art cinema,” see her Storytelling in Film and Television.

PPPPS 5 May 2011: Jackie Cooper died yesterday. The Times obituary glancingly mentions Hennesey, but ignores its real achievements.

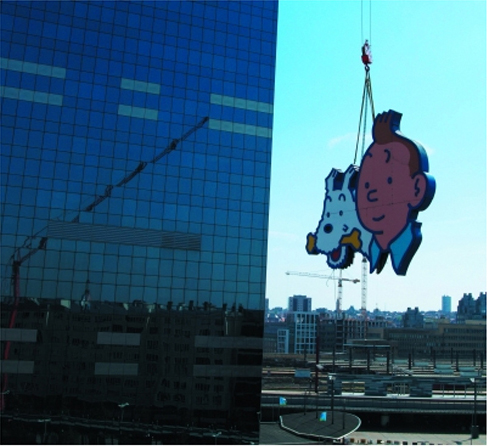

Tintinopolis

Photo by David Bordwell, July 2009. Tous droits réservés.

DB here:

He’s the world’s most famous fictional Belgian, miles ahead of Hercule Poirot. But I ignored him for about sixty years. Tintin wasn’t part of my childhood, and I didn’t get interested in his adventures until recently. Now, though, the scales have fallen from my eyes and I realize that Hergé is a great comics artist. And naturally I see him doing some things that shed light on cinema.

I came to the work obliquely. Since the 1980s Kristin and I have admired the Dutch cartoonist Joost Swarte. When we started to collect his books, lithographs, and CDs back in the 1980s, he was becoming known in the US through Art Spiegelman and Francois Mouly’s Raw. We were much taken with Swarte’s exact drawing style and mordant wit. I then got interested in the crisply drawn “clear line” tradition of French, Belgian, and Dutch cartoon artists stemming from Hergé—Chaland, Floc’h, Goffin, Ted Benoît, etc.—but I still didn’t pay much attention to the master himself.

This spring I gave a talk on La Ligne Claire to Kristin’s reading group, which explores fantasy (especially Tolkien), science fiction, comics, movies, and almost everything else. In preparing that, naturally I had to go back and read Hergé. Now I’m a believer. Some day I may polish that presentation and put it up as a web essay, but for now I just offer some notes, sojourning as I was recently in Tintin’s home town.

His own museum

Photograph copyright Nicholas Borel; Christian de Portzamparc, architect.

Brussels has its own superb museum of comic art, the Belgian Comic Strip Centre in Rue des Sables. Last year, however, the Musée Hergé opened in Louvain-La-Neuve.

Louvain-La-Neuve is itself an unusual place: a town created more or less from scratch when the Catholic University of Louvain split off from the Dutch-speaking University of Leuven. Originally designed for students, the town now has a population of about 30,000, with many citizens commuting to jobs in Brussels. This planned city has been hailed as a model of urban design; parking and car traffic, for instance, are underground.

Go through the square to a wooded park and soon you’re in the Musée Hergé. It is one those buildings that aim to awe you. There are few right angles, and huge spaces are dominated by pyramids, cylinders, and other three-dimensional solids, all in muted colors and bearing the sorts of squiggles Herge might use for foliage.

Photograph copyright Nicholas Borel; Christian de Portzamparc, architect.

Architect Christian de Portzamparc‘s statement of principles is here.

The first floor consists of the lobby, rest rooms, a restaurant, and a space for temporary exhibitions. As luck would have it, a tribute to Joost Swarte’s 40-year career was on display, and it was jammed with material. I could easily have spent the whole day here, even though I’d seen much of the material before. Swarte was also the “scenographer” of the Musée, offering ideas on interior design and decoration. The witty museum logo, as well as details like the signage, seem to be Swarte’s creations.

The first floor consists of the lobby, rest rooms, a restaurant, and a space for temporary exhibitions. As luck would have it, a tribute to Joost Swarte’s 40-year career was on display, and it was jammed with material. I could easily have spent the whole day here, even though I’d seen much of the material before. Swarte was also the “scenographer” of the Musée, offering ideas on interior design and decoration. The witty museum logo, as well as details like the signage, seem to be Swarte’s creations.

According to the guidebook, 80 % of Herge’s working material survives. This mountain of sketches, layouts, inked pages, color pages, and the like gives the curators a huge amount to pick from. Although the exhibition halls don’t feel stuffed, you quickly realize that you are in for total immersion.

You start at the third floor, and the first room supplies a survey of Hergé’s career. The information on the walls is pretty skimpy; the details are offloaded onto the headset commentary, I suspect. Charles Trenet’s ditty “Boum!” is playing over and over in this room, presumably not as an homage to Toto le héros but as a broad gesture to the interwar period. There are some intriguing Hergé illustrations here, including a 1939 political cartoon showing a Belgian shaking his fist at German planes flying over Brussels and shouting, “Dirty Boches!” before running to hide in his basement.

Another room is devoted to Hergé’s commercial art–posters, magazine advertisements, and book covers (including one for Christ, King of Business, 1929). Also on display are some striking images from less-known Hergé comic series, such as Quick and Flupke, Tom and Millie, and especially Jo, Zette, and Jocko. From here you move to a room devoted to the characters. Each one (except Tintin) gets a vitrine full of imagery. The final room on the floor is devoted to the cinema. The displays trace many of the situations and characters that Hergé borrowed from films of the 1920s and the 1930s. There’s also a filmed biography of Hergé screening on a loop.

The second floor was what held my interest most intently. One room includes a huge display of research materials for each book–not only notes and photos, but artifacts too. There’s also a case showing early Tintin games, toys, apparel, and other merchandise. The next hall gets to the root of my interest, Hergé’s creative process. Several displays trace the progress of a single page from rough layout to final coloring and printing. He was quite explicit about his aesthetic: Color is applied uniformly, with no shading, which yields “une grande lisibilité.” As I’ll suggest below, story legibility is central.

In this display room as well you can see how Hergé designed pages for periodical publication in landscape mode, then redesigned them for the vertical book format. That entailed cutting out panels, drawing new ones, and even changing gags. The books would then sometimes be recast for later editions. All these multiple versions have kept Hergé scholars busy for decades.

At about age 40 Hergé began to take on collaborators, and he eventually created a team of scenarists, lettering specialists, inkers, painters, and the like. In the next display room, you can see a TV documentary touring the studio and interviewing staff. This room also includes some gorgeous black-and-white ink drawings of pages and one-off projects, like Christmas cards. Your tour of the Museé ends with a room devoted to Hergé’s fame, starting with the famous wishes sent by Alain Saint-Ogan, creator of the breakthrough French comic strip Zig et Puce. In here you find praise from Balthus, Philip Pullman, Andy Warhol, and Alain Resnais: “Belgium belongs to the realm of fantasy. I found this out through reading Tintin.”

All in all, an exhilarating place to visit. It is unabashedly a tribute to Hergé and makes no effort to invoke the controversies around the man. I could find no reference to his wartime career and the political controversies that followed, to his divorce, or to the spiritual quest of his later years. This is the modern art museum in wholly celebratory mode. Still, few exhibitions of comic art I’ve seen make such a persuasive case for the enduring quality of an artist’s achievement.

Cinema on the page

I have taken from the current cinema its devices of découpage: once a character becomes important, you show what he’s doing, you vary the shots, you show the same scene from far off and then quite close.

Hergé, 1939

I’m a man of order, you see, even in drawing. I draw orderly things so one can read what I am drawing.

Herge, 1975

All comic strips and books remind us of cinema in one way or another, and many researchers have analyzed the affinities. The panels can simulate cutting, or panning camera movements, or even the fixed frame in which actions unfold over time. (Blondie is a classic example.) Artists have provided unusual angles and dynamic compositions that have a filmic feel. And like films, comics are usually narratives, stories told in pictures, so we can study how different comics artists use point-of-view, plot structures, suspense, and the like. (I did this last year with a recent twist in the Archie series.)

Most commentators on Hergé mention that he was a film fan and drew many situations from movies of the 1920s and 1930s. Like Hollywood studio cinema, his tales put striking technique in the service of fluent storytelling. Pause to study the narrative and you’ll find a surprising richness to the imagery; start by looking at the pictures as pictures, and you’ll see how composition, color, and detail smoothly advance the action. Hergé was well aware that his polished imagery could stand scrutiny in its own right, but he saw it as serving a larger narrative dynamic. He noted (my emphasis added):

I don’t try only to tell a story, but rather I try above all to tell a story. There’s a slight difference.

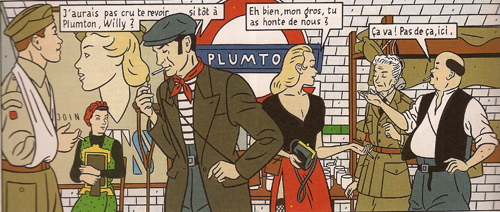

We can get a sense of this approach by contrasting it with one of the best Clear Line followers. Jean-Claude Floc’h’s albums are retro studies of a cozy, more or less imaginary England of the 1920s through the 1950s. He has provided his main characters, Francis Albany and Olivia Sturgess, with fake biographies that tie them to real artistic circles of the period. A series of books set in wartime (Blitz, 1983; Underground, 1996; Black Out, 2010) presents gorgeous tableaux. Here are two panels from facing pages of Underground. Londoners are huddling during a Nazi bombing run.

The images are designed to be compared in detail; we’re to note the slight changes in figures’ position. The story halts while you study the panels (and admire the artist’s finesse). This is technique calculated to dazzle.

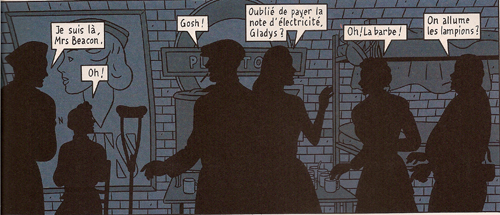

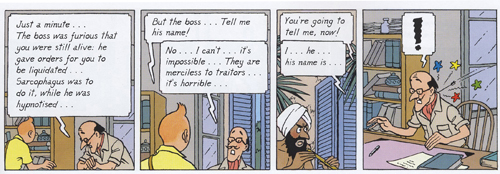

Hergé’s pages warrant the same sort of scrutiny, but you aren’t invited to dwell on them through a flagrantly overdesigned layout. The echoes and rhymes in this passage of the final English-language version of The Secret of the Unicorn are at least as intricate as Floch’s, but they’re at the service of symmetrical gags nestled in a broader comic buildup. Thompson and Thomson have had their pockets picked in a street market.

Hergé erases the background detail to allow us to concentrate on the graphic play of the black-suited figures (“spotting blacks,” as it’s called in the trade). The second panel reverses Thom(p)son’s attitude in the first, and both find a neat mate in the next-to-last panel. The third panel on top is rhymed with the last panel on the bottom. In between, the interplay of the two detectives is given in slightly varied compositions, with the extra walking sticks shifting around in their own patterns. The gag is a variant of the basic premise of Thompson and Thomson’s existence: they are mirror-images in all they do and say.

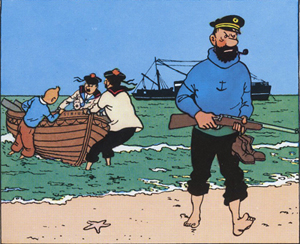

Given this play of variations, how does Hergé achieve narrative flow? One factor is the width of the panels, expanded or pinched according to the information in each and coordinated rhythmically across the page. Hergé also avoids gesture lines. Instead, one panel presents a point of motion as if captured by snapshot, and then the next panel provides the next phase of the movement. We might notice as well how the left-to-right propulsion of his drawings lays out narrative elements concisely. He declared this panel, from Red Rackham’s Treasure, one of two images that gave him most satisfaction:

Solely through the drawing, which shows the captain striding onto the beach with naked feet while his companions haul their boat onto shore, the viewer-reader [spectateur lecteur] mentally reconstructs everything that has already happened: The Sirius was put at anchor, the rowboat was lowered, Tintin and his companions set out; they have rowed to arrive at the island, where the captain climbed out. . . Everything that preceded the action shown in the drawing is expressed by a single composition.

Here’s another subtle technique Hergé used to make his stories flow. Psychologists speak of the “priming” effect. You’ll notice something faster if it chimes with something you’ve recently encountered. The classic experiment uses a string of words. If you’re first shown the word yellow, you’ll identify the word banana faster than if the trigger word is red.

Priming is a basic filmmaking resource. What the screenwriter calls “planting”–the pistol on the mantelpiece in Act I–is a type of longer-range priming. On a smaller scale, one purpose of an establishing shot is to prime certain areas of a locale for future action. Here’s a simple example from Norman Taurog’s The Caddy (1953). Jerry Lewis is fleeing from a pair of German Shepherds and he takes refuge in a men’s changing room.

A new shot shows him closing the door, and it makes prominent the coat rack nearby. Eventually Jerry notices it and expresses happiness as only Jerry can.

Using the robe and beret hanging there, he tries to disguise himself.

A close look at my first frame shows that the coat rack was (subliminally?) primed in that shot too; you can glimpse it when Jerry opens the door. This reminds us that the filmmaker can prime our response by including a little something at the end of one shot that ties it to the next. Both Spielberg and Johnnie To are skilful at this; see earlier blog entries (here and here) for examples.

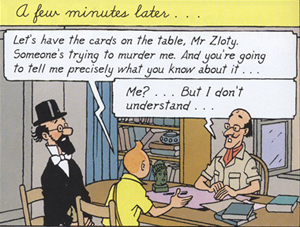

It seems to me that Hergé makes use of fine-grained priming in the flow of his panels. Here’s an example from the final English-language version of Cigars of the Pharaoh. The “establishing shot” shows Tintin and Sarcophagus consulting Zloty. The composition is simple and balanced, with Tintin as the fulcrum. The window behind Zloty is unobtrusively primed.

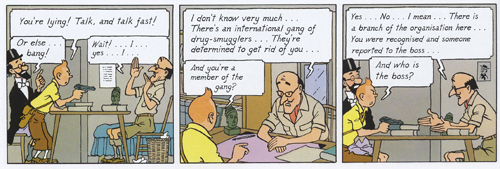

The next stretch of panels breaks this overall layout down into two sorts of shots: a profile view and an over-the-shoulder view of Zloty.

The first and the third panels are variants, with the framing getting closer as we proceed. Hergé often propels his story through these tighter framings, as if to ratchet up the tension in a filmic way. The more compressed array of figures at the end of the series also allows for more spacious speech balloons, always a major consideration in the Tintin saga. Hergé didn’t reiterate the window in every framing; only the middle panel re-primes it through our angled view of Zloty.

Now the framing will get even tighter on Tintin and Zloty, losing Sarcophagus altogether, and the window will become more salient, even though it’s still a minor element of each design.

The massive balloon at the top of the first frame in this series obliges Hergé to push his figures quite low, but he compensates by letting them lean on the bottom edge as if it were the desktop. (Hergé likewise often makes his characters stand directly on the frameline.) The first panel retains the window frame. The second, another over-the-shoulder shot but even tighter than the first, introduces the shutters in a prominent position behind Zloty. These shutters prime the third frame. They now anchor a crucial action: the Fakir is lurking outside those shutters.

The final panel provides the payoff. The open window frame that seemed at first just a realistic detail becomes necessary to understanding the action. It could have been established in a wider shot, but in keeping with his urge for economy Hergé has primed it in the most compact way possible–as a peripheral element, in the background or on the frame edge. (Compare Taurog’s thrusting the coat rack under our noses.) You have to wonder if such economy of expression will be on display in the Spielberg-Jackson Tintin movie project.

I know, I know: David, it’s just a window. Or: David, it’s just a comic strip. But as film students we ought to be interested in how images shape our experience, and we can learn from any craftsmanship as precise and engaging as Hergé’s.

For more on the Clear Line style, see the series of articles at Paul Gravett’s excellent site.

The official Tintin website is available in an English version here. Since photography is not permitted in the Musée, for illustrative purposes I have drawn on the official images on the building’s website, with copyright and credit as noted in the captions. Bart Beaty, expert on Eurocomics, provides a carefully considered report on his trip through the galleries. The Musée’s catalogue is a trilingual survey of major items on display, although it neglects to illustrate changes in layouts across different editions.

On the aesthetics of comics and cinema, see Manuel Kolp, Le Langage cinématographique en bande dessinée (Brussels, 1992). Principles of page composition, including spotting blacks, are explained in Gary Spencer Millidge, Comic Book Design: The Essential Guide to Designing Great Comics and Graphic Novels.

The best general introductions to Hergé’s artistry seem to me to be Benoît Peeters’ Tintin and the World of Hergé and Michael Farr’s Tintin: The Complete Companion. Both offer occasional comparisons of different editions of the books. See as well Philippe Goddin’s multi-volume set of primary materials. Goddin supplies a shorter sampling of the artist’s creative process in his charming but now rare Comment naît une bande dessinée: Par-dessus l’épaule d’Hergé. For an example of in-depth inquiry into the various changes that a tale underwent from one edition to another, see Étienne Pollet, Dossier Tintin: L’Isle noir: Les Tribulations d’une aventure.

My first and fourth Hergé quotations come from Bob Garcia’s Hergé et le 7ème art, pp. 6 and 9. My second quotation is taken from the English edition of the Musée Hergé guidebook (Moulinsart, 2009), p. 48; I don’t find it to be available for purchase online. My third quotation comes from Numa Sadoul’s Entretiens avec Hergé: Tintin et moi, p. 46. According to Harry Thompson in another good introduction, Tintin: Hergé and His Creation, the young Hergé wanted to be a film director (p. 26).

A very extensive web resource on Floc’h is here. As for Archie’s wedding: It did turn out to be one of those parallel-universe stories. It has developed over seven issues since last September in a “mini-series.” Abrams will be publishing a special collector’s edition, according to the press release, “for the Archie fan in all of us.”

This is probably as good a place as any to mention that Intellect Press has just launched a new journal, Studies in Comics. Details, as well as downloadable essays from the first issue, are here.

PS 24 January 2011: This essay was named one of the best pieces of online comics criticism of 2010 in an exercise conducted by The Hooded Utilitarian of The Comics Journal. What an honor! Thanks to the judges, and congratulations to the other writers who earned places on the list.

Les dessins, textes et symboles extraits de l’oeuvre de Hergé cités dans ce essai sont la propriété exclusive de © Moulinsart S. A. ou © Hergé ou © Casterman et sont montrés à titre de référence et d’exemple.

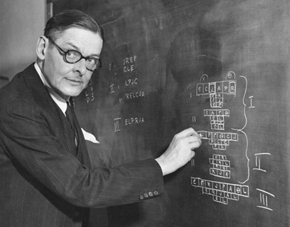

Photo, uncredited, from this site.

Glancing backward, mostly at critics

DB bere:

As Freud’s mom says in Huston’s film, “Memory plays queer tricks, Siggy.” Herewith, some journeys into the past, launched on a lazy June afternoon.

Ten-best lists are nothing new. The New York Times ran them in the 1930s. Here’s one for 1940 (NYT 29 Dec 1940, p. X5).

The Grapes of Wrath, The Baker’s Wife, Rebecca, Our Town, The Mortal Storm, Pride and Prejudice, The Great McGinty, The Long Voyage Home, The Great Dictator, and Fantasia.

The author’s runner-up titles include Of Mice and Men and The Philadelphia Story. Pretty tasteful by today’s standards, no? Who came up with a list including Hitchcock, Borzage, Sturges, Pagnol, Chaplin, Disney, Milestone, Cukor, and Ford twice?

None other than Bosley Crowther, long-serving Times reviewer who became the emblem of middlebrow taste in endless polemics (including some I’ve mounted). Who knew he was a closet auteurist?

Winchester ’73 (1950).

Now try this one.

The movies live on children from the ages of ten to nineteen, who go steadily and frequently and almost automatically to the pictures; from the age of twenty to twenty-five people still go, but less often; after thirty, the audience begins to vanish from the movie houses. Checks made by different researchers at different times and places turn up minor variations in percentages; but it works out that between the ages of thirty and fifty, more than half of the men and women in the Unites States, steady patrons of the movies in their earlier years, do not bother to see more than one picture a month; after fifty, more than half see virtually no pictures at all.

This is the ultimate, essential, overriding fact about the movies. . . .

Yes, another oldie, this time from Gilbert Seldes’ book The Great Audience (1950). What we’ve been told for years was characteristic of our Now—the infantilization of the audience—has been in force for at least sixty years.

By the way, here are some US features released in 1950: Father of the Bride, Gun Crazy, House by the River, In a Lonely Place, Julius Caesar, Mystery Street, Night and the City, Panic in the Streets, Rio Grande, Shakedown, Stage Fright, Stars in My Crown, Summer Stock, Sunset Blvd., The Asphalt Jungle, The Baron of Arizona, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, The Gunfighter, The Third Man, Twelve O’Clock High, Union Station, Wagon Master, Where the Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool, Winchester ’73, and probably some other good movies I haven’t seen.

Perhaps not a luminous year, but I’d settle. Especially compared with 2010. Did kids just have better taste then?

Beyond reviewing

Most people conceive a film critic as a film reviewer. The review is a well-established genre, and we all have its conventions in our bones. At a minimum, you synopsize the plot, comment on the acting, mention the pacing or the cinematography, throw in some wisecracks, and recommend or condemn the film. Good reviewers do these things well, but the genre remains a limited one.

Crowther was a reviewer; Seldes was something more. But how to define that extra something? Two long-lived heavyweights can help us.

In the 1935 essay “The Literary Worker’s Polonius: A Brief Guide for Authors and Editors,” Edmund Wilson spells out what he takes to be the duties and genres of literary labor. At the time, the “New Criticism” in the universities had barely gotten started, so most literary criticism Wilson encountered was journalistic and belletristic—that is, reviewing.

Accordingly, Wilson distinguishes different types of reviewers. There the people who simply need work. There are literary columnists who pump out observations on the latest books. There are people who want to write about something else; that’s when you use the book under review as a pretext to ride your hobby horse. There are the reviewer experts, as when a philosopher is called in to review a book of philosophy. Then there’s the rarest, the “reviewer critics.” Here is why such creatures are rare.

Such a reviewer should be more or less familiar, or ready to familiarize himself, with the past work of every important writer he deals with and be able to write about an author’s new book in the light of his general development and intention. He should also be able to see the author in relation to the national literature as a whole and the national literature in relation to other literatures. But this means a great deal of work, and it presupposes a certain amount of training.

In sum, the best critic has to be very, very knowledgeable. But is knowledge enough?

T. S. Eliot, it’s often said, believed that the only qualification of a critic is to be very intelligent. (One example of this claim is here.) What Eliot actually wrote is more interesting. His 1920 essay “The Perfect Critic” is considering Aristotle as a theorist of literature. Of The Poetics he notes:

In his short and broken treatise he provides an eternal example—not of laws, or even of method, for there is no method except to be very intelligent, but of intelligence itself swiftly operating the analysis of sensation to the point of principle and definition.

The final clause is a good description of what I take “poetics” to be as applied to film. We analyze effect (“sensation”) so to discover not laws but principles (governing a genre, a trend, a style, whatever) that we in turn articulate (“definition”). In this analysis, we don’t use a method—that is, I take it, a prior commitment to a system of thought that blocks our seeing the object in its own terms.

Contrary to the common modern view that our personal feelings and ideas color everything we think about, Eliot seems to advocate a more objective way of thinking. Aristotle the theorist is praised because “in every sphere he looked solely and steadfastly at the object.” His search for the principles underlying tragedy, comedy, and epic is contrasted with the dogmas of Horace, the “lazy critic” who offers us precepts, tips from the top about laws to be obeyed. (Sound familiar from screenplay manuals?)

Aristotle, Eliot thinks, was endowed with “universal intelligence”: “He could apply his intelligence to anything.” Such a gift overrides the sort of specialized inquiry that yields “methods.” I read “The Perfect Critic” as recommending that critics try to combine their sensitivity to nuance with Aristotelian intelligence:

Aristotle had what is called the scientific mind—a mind which, as it is rarely found among scientists except in fragments, might better be called the intelligent mind. For there is no other intelligence than this, and in so far as artists and men of letters are intelligent (we may doubt whether the level of intelligence among men of letters is as high as among men of science) their intelligence is of this kind.

This is what it is to be “intelligent” in Eliot’s sense: to be wide-ranging, rigorous, and committed to understanding the artwork both as unique object and embodiment of principle. He finally spells it out in his praise for the Symbolist Remy de Gourmont:

Of all modern critics, perhaps Remy de Gourmont had most of the general intelligence of Aristotle. An amateur, though an excessively able amateur, in physiology, he combines to a remarkable degree sensitiveness, erudition, sense of fact and sense of history, and generalizing power.

So Wilsonian erudition and historical knowledge aren’t enough. You need sensitivity, “a sense of fact,” and “generalizing power”—the ability to see larger implications and principles at work in what you’re writing about. In short, the best critics don’t shy away from probing ideas.

The general go

Where do the ruminations of Wilson and Eliot leave us with writers who go beyond reviewing? Let’s go back to Seldes.

He became one of our best American critics, in fact one of our first media critics, thanks to his “generalizing power.” The 7 Lively Arts (1924) was a trailblazing defense of Tin Pan Alley, comic strips, vaudeville, jazz, and films. Reacting against “genteel” taste, Seldes believed that the bursts of exaltation to be found in the “minor” arts were as profound as anything to be found elsewhere. “Our experience of perfection is so limited that even when it occurs in a secondary field we hail its coming.” Such perfection is to be found, he says, in an instant in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, when Cesare seizes Jane and the bed curtains snag her gown. He starts with what Eliot called “sensation,” the piercing arousal.

A moment comes when everything is exactly right, and you have an occurrence—it may be something exquisite or something unnamably gross; there is in it an ecstasy which sets it apart from everything else.

But Seldes goes beyond noting moments that give him a buzz. He tries to explain how and why the vulgar arts can arouse us. It’s hard for us now to realize that what we take for granted as vital popular culture was scorned by the much of the intelligentsia. In 1924 Seldes set out on a crusade to convince his readers that the Keystone Kops, Flo Ziegfeld, Irving Berlin, ragtime, and Fanny Brice offered more of genuine artistry than the Bogus Arts (we’d say middlebrow) that were then ruling high culture. In 1924, this was a thunderbolt:

The daily comic strip of George Herriman (Krazy Kat) is easily the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.

If the best critics offer not only opinions but information and ideas to back them up, The 7 Lively Arts had both in abundance. Seldes begins the book with the suggestion that the consolidation of the film industry, and particularly the establishment of Triangle, Kay-Bee, and Keystone, was the turning-point in the history of American film. But instead of the usual litany of praise for Griffith’s and Ince’s discovery of “cinematic” storytelling, Seldes condemns them as too quickly seduced by extravagant spectacle. The journeyman Mack Sennett stuck to making “the most despised, and by all odds the most interesting, films produced in America. . . . He is the Keystone the builders rejected.” Far more than the work of Griffith and Ince, Sennett’s comedies exploit what cinema is best suited for: chases, crashes, explosions, “locomotives running wild, yet never destroying the cars they so miraculously send spinning before them. . . . And all of this is done with the camera, through action presented to the eye.”

Seldes wrote about radio, dancing, and other pastimes, but films were his special love. An Hour with the Movies and the Talkies (1929) and The Movies Come from America (1937) combine historical knowledge with subtle appreciation of the forces operating on studio picturemaking. These books thrum with ideas. For instance, Seldes defends the director as the key creative artist in cinema. One reason is that only the director can control pacing.

The director is responsible for the general go of a picture, for making it run off neatly, for controlling the speed of its various parts, for seeing that a romantic episode does not race along while a melodramatic conversation lags. He is, or ought to be, responsible for the interruptions of the main action of the picture so that a comic interlude is not placed too near to the climax of a tragic one, but only near enough to give more intensity to the emotion.

What about the camera? Hollywood movies, he says, have developed a rapid-turnover tradition that favors conciseness and novelty in the flow of images.

When Van Dyke in 1934 [in The Thin Man] wished to show a familiar event in the life of any man who walks a dog—an event which, although familiar, might not be passed by the censors—he merely showed the leash tightening and the hand of the man being jerked back; then the man stood still and a little later the same operation was repeated. . . . The part not only takes the place of the whole, but is more effective because the imagination of the spectator supplies what is missing.

Seldes might have added that once we’ve supplied that missing piece, we laugh at Asta’s ability to puncture Nick Charles’ serious disquisition on murder.

Seldes became a tamer thinker later in life. By the 1950s he was part of the media establishment, producing television shows on culture. He grew disappointed with the film industry, leading to his critiques in The Great Audience. Still, his critical skills persisted. His next major book, The Public Arts (1956), pins his hopes on television but also offers a balanced account of Hollywood’s widescreen revolution. Confronted with CinemaScope and its kindred systems, he worried, again, about pacing.

Wherever the movie touches time, it as mysterious and primordial as the beating of the heart. Absorbed in new techniques, directors may neglect essentials as they did a generation ago when they immobilized the camera to favor the microphone; but, as they recovered mobility then, so I am confident that they will recover the art of using and manipulating time in the substructure of their pictures.

Although he’s seldom discussed in film circles now, Seldes stands out as a worthy critic not because of one-off reviews but in virtue of his pointed, sometimes daring ideas, his knowledge, and the zest they arouse in the reader. These are the payoffs, I think, when a critic leaves reviewing, even the 10-best lists and other fun parts, behind.

My quotations from Seldes come from The Great Audience (New York: Viking Press, 1950), 12; The 7 Lively Arts (Mineoloa, NY: Dover, 2001), 204, 309, and 5; Movies for the Millions (London: Batsford, 1937), 75; The Public Arts (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 55-56. For more on Seldes and his milieu, see Michael Kammen’s excellent intellectual biography, The Lively Arts: Gilbert Seldes and the Transformation of Cultural Criticism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

My quotation from “The Literary Worker’s Polonius,” comes from Edmund Wilson, Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s and 1930s (New York: Library of America, 2007), 490.

Although the terminology is different, Eliot seems to be advancing something similar to Kristin’s arguments about film analysis in the first chapter of Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

The Thin Man (1934). Seldes forgot that it was Nora, not Nick, who senses Asta’s response to the call of nature.

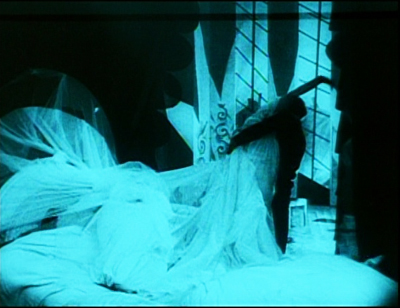

Watching a movie, page by page

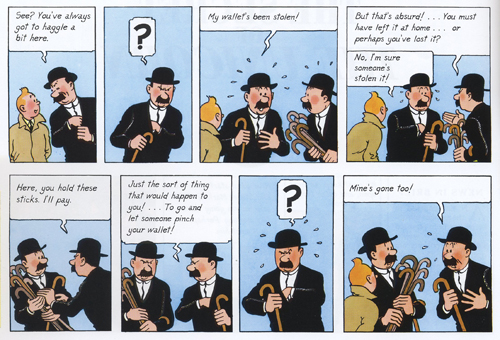

The Ghost Writer (above); The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (below).

DB here:

Aristotle said, quite reasonably, that every plot has a beginning, a middle, and an end. But that doesn’t mean that every plot consists of three acts. Aristotle doesn’t mention act divisions in the Poetics for the good reason that classical Greek plays didn’t have them. The three-act play is just one convention that emerged in the history of storytelling.

As early as 20 BCE Horace was suggesting, “Let no play be either shorter or longer than five acts.” Influenced by this edict, Renaissance editors and playwrights adhered to five acts for many years. We have, of course, plays in two acts (Alan Ayckbourn’s Norman Conquest cycle) and four acts (Pygmalion, The Admirable Crichton, many of Chekhov’s). TV dramas are routinely divided into a teaser and four acts, broken up by commercials. All of those plots have beginnings, middles, and ends, so it’s silly to think that only the three-act structure can fulfill Aristotle’s dictum.

As early as the seventeenth century, the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega recommended three acts as best. In Europe, the format came into its own during the nineteenth century, evidently dislodging the five-act one. One reason may have been that three parts are architecturally simple, sturdy, and easily visualized. Around 1820 Hegel remarked: “Three such acts for every kind of drama is the number that will adapt itself most readily to intelligible theory.” What such a theory might look like was sketched by Lope, who anticipates modern advice manuals.

In the first act set forth the case. In the second weave together the events, in such wise that until the middle of the third act one may hardly guess the outcome. Always trick expectancy.

So proponents of the three-act screenplay formula should revise their pedigree. They’re actually pushing the Lope-Hegel tradition—which admittedly sounds less impressive than dropping the name of Aristotle.

Three acts, more or less

Despite the historical misunderstandings, there’s some reason to think that Hollywood screenwriters, and now filmmakers across the world, have followed a rough three-“act” scheme. Where they got this idea and when it started is still hard to say, but it’s been at the core of nearly every screenplay manual since the 1980s. Kristin and I have looked at this format from an academic perspective, and our views are outlined briefly on this site here and here and here. For more detailed arguments you can read her Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

In those places we’ve argued that Hollywood feature films tend to fall into chunks of 20-30 minutes. As a result a movie may display three parts, or four, or more (if the film is very long) or even two (if it’s unusually short). When the film has four parts, it tends to split the long second act that the manuals recommend into two.

A four-parter usually goes like this. A Setup lays down the circumstances and establishes the primary characters’ goals. The Complicating Action is a sort of counter-setup, modifying the original goals or creating new ones. At about the midpoint, there emerges a Development section characterized by delays, subplots, and backstory. There follows the Climax, which resolves the action by decisively achieving or failing to achieve the protagonist’s goals. The film typically ends with a brief Epilogue that establishes a settled state, happy or unhappy. Each of these sections is demarcated by a turning point—a moment of crisis, usually involving an unforeseen twist or a major decision by the protagonist.

Two recent films, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, offer good examples of how the four-part template governs plot structure. I won’t walk through each one here, but both seem to me to adhere quite closely to this model. Today I’m more curious about the original novels. We know that books are routinely reshaped for movie treatment. Is there a sense in which the plot structure of the originals fits the film formula?

Fiction as film

I ask because some fiction writers have come to believe in the enduring power of the three-act structure for all narratives. In The Weekend Novelist (1994), Robert J. Ray recommends that aspiring writers use it (although he breaks Act II into two parts around the midpoint). He finds the pattern enacted in his book’s primary model, the novel The Accidental Tourist. “We’re working with the structure of [Anne] Tyler’s Tourist because it is classical, three acts” (142). This, Ray claims, follows “Aristotle’s dictum of beginning, middle, and end” (141). Ray makes a comparable suggestion in The Weekend Novelist Writes a Mystery (1998), naming the three parts Setup, Complication, and Resolution; a midpoint again splits “Act II.1” from “Act II.2.”

Ray’s are the earliest instances I’ve found of explicitly applying screenwriting structure to prose fiction. Later ones would include Stephen Greenleaf’s 1996 article “A Mystery in Three Acts” and James Scott Bell’s 2004 book Plot and Structure. Bell argues somewhat grimly that life itself has three acts: childhood, “the middle where we spend most of our time,” and “a last act that wraps everything up” (23). Ridley Pearson, in the 2007 article “Getting Your Act(s) Together,” tells us that the “three-act structure, handed down to us from the ancient Greeks [!], is one that’s proven successful for thousands of years” (67). “Name a film or book you think rises above others, and chances are, if you go back and study it, the story line will fit into this form” (85). Brenda Janowitz recommends plotting a Harlequin romance as if it were a movie like Mean Girls.

But screenwriting adepts will notice one thing that these advisors neglect: the lengths of the parts. The book that popularized the three-act structure in film circles was Syd Field’s Screenplay of 1979. Not only did he lay out the template, but he indicated running times for each section. Act 1 should last about thirty minutes, Act 2 sixty minutes, and act three about thirty. Assuming that one minute of screen time equals a page of the screenplay, that means that a two-hour movie should run about 120 pages. Field’s metric proved very influential, with script readers, producers, and writers all striving to find plot points at twenty-five minutes and ninety minutes.

To be strictly parallel, then, a “three-act novel” should be divisible into parts having a page ratio of 1:2:1. The only manual I know that is willing to bite this bullet is Writing Fiction for Dummies (2009). (The title has a catchy ambiguity, no?) According to the authors, Act 1 takes up the first quarter of the book, Act 2 the middle half, and Act 3 the last quarter (p. 147).

In the film versions of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, the segments and timings fit the four-part model fairly neatly. (Try it yourself, in the theatre or when the films come out on DVD.) But what happens when we look at published books? Will we find what Ray found in The Accidental Tourist—conformity to the formula? Are practicing novelists using the template? Are the timings, or rather the page-counts, of the books congruent with the film model?

First I’ll consider Robert Harris’ novel The Ghost, the source of The Ghost Writer. The next section looks at Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. If you want to avoid spoilers, skim and skip accordingly.

Ghost writers in the sky

The opening chapters of The Ghost introduce the unnamed narrator, a professional writer who is on the verge of breaking up with his girlfriend. Hired to ghost-write ex-Prime Minister Adam Lang’s memoirs, he is replacing Lang’s aide McAra, who drowned under mysterious circumstances. The Ghost takes the job just as news media are floating the charge that Lang helped the US ship British citizens to black sites to be tortured. The Ghost travels to join Lang, who is staying in America with his secretary Amelia and his wife Ruth. At his hotel, the Ghost encounters a surly British man who asks him pointed questions about Lang. This setup lays out the affair between Amelia and Lang, Ruth’s sexual jealousy, and the mounting political pressure on Lang, along with the sinister Brit in the bar. The section ends on p. 83 of the 335-page Gallery paperback edition, almost exactly one-quarter of the book.

The complicating action arrives when the Ghost’s first sit-down with Lang the next day is interrupted by the announcement that Rycart, former Foreign Secretary in Lang’s government, has asked the Hague to investigate the PM for war crimes. Under pressure from protestors, Lang decides to go to Washington for appearances’ sake. In the meantime, the Ghost discovers a set of clues McAra has left behind: photos of Adam in his Cambridge days, records and news reports of his party activities, and a mysterious phone number that turns out to be Rycart’s. All this creates a counter-setup. There is something foul afoot.

The Ghost ruminates constantly on McAra, a writer who has become something of a ghost haunting his successor. Soon the digital file of McAra’s draft of the memoir vanishes from the Ghost’s email. Most fundamentally, he discovers that in the first interview Lang has lied to him about how he got into politics.

That was when I realized I had a fundamental problem with our former prime minister. He was not a psychologically credible character. In the flesh, or on the screen, playing the part of a statesman, he seemed to have a strong personality. But somehow, when one sat down to think about him, he vanished. This made it impossible for me to do my job. . . . I simply couldn’t make him up (162).

At this point the protagonist decides on a new goal: to investigate on his own. This transforms his official assignment, and it happens on p. 163—quite close to the midpont of the book.

The development section is filled out with the usual delays, false leads, counter-maneuvers, and backstory. The Ghost’s investigation brings him to an interrogation of an old man who suspects foul play in McAra’s death, a sexual encounter with Ruth, a meeting with a professor with apparent CIA connections, and a suspicious vehicle in the vicinity. The turning point comes with another decision. “The more I considered it, the more obvious it seemed that there was only one course of action open to me.” The Ghost phones Rycart and flies to New York to meet him. This passage concludes on p. 256.

The climax sporadically unravels the clues McAra has left behind. In their meeting Rycart and the Ghost conclude that Lang was recruited by Professor Emmett during their Cambridge days and became a US puppet. Rycart has taped his exchange with the Ghost and uses that to force him to return to confront Lang. On Lang’s private plane, the Ghost accuses him but Lang’s denials are disconcertingly sincere. On disembarking, he is killed by a suicide bomber—the crusty Brit who blames Lang for the death of his son in Iraq. Although he’s haunted by dreams of a drowning McAra (“You go on without me. . .”), the Ghost plows ahead with Lang’s now-posthumous memoirs. All seems to have been settled until the book launch, when the Ghost discovers another way to interpret the evidence. He returns home to check McAra’s manuscript, where he finds a coded message identifying Ruth as the one recruited by Emmett; she was the mole. This revelation that the first solution was wrong, a detective-story device going back at least to Trent’s Last Case of 1913, arrives on p. 330.

An epilogue of only five pages reports that the Ghost is on the run. If anything happens to him, his former girlfriend will publish his story. “Am I supposed to be pleased that you are reading this, or not? Pleased, of course, to speak at last in my own voice. Disappointed, obviously, that it probably means I’m dead.”

The result conforms fairly strongly to the triple ratio: Act 1 runs 83 pages, Act 2 runs 173 pages, Act 3 runs 79 pages. Using the four-part template, we get 83/80/93/74, with a five-page epilogue.

Not perfect symmetry, but that’s hardly to be expected. Novelists stretch or compress as needed, and they can make scene boundaries a little fuzzier than what we find in films. For such reasons, other analysts might shift my breakpoints a few pages fore or aft. In addition, many films make the climax section somewhat shorter than the others, so we won’t always get perfect symmetry in novels either. Still, The Ghost offers a reasonably close approximation to the sort of plot template that we find in many commercial movies.

Double duty

Stieg Larsson’s The Girl Who Played with Fire provides a somewhat different sort of plot. We have two protagonists and three lines of action—two mysteries plus a search for revenge—or rather four, if you count the prospect of a romance between the protagonists. The book is also much longer than The Ghost, running 644 pages in the Vintage paperback edition I have. You might therefore expect more large-scale parts. But . . . .

The setup lays out the three major lines of action. Journalist Mikael Blomkvist, misled by an informant, publishes a false news story about the dealings of the businessman Wennerström. After Blomkvist is sentenced to prison, the second line of action kicks in: Henrik Vanger asks him to find what happened to his brother’s granddaughter Harriet. Meanwhile the neopunk hacker Lisbeth Salander is introduced as a security analyst researching Blomkvist for Vanger. By p. 138 Blomkvist has decided to accept the Vanger assignment. This section is not far from being a quarter of the text, and it corresponds to a major break, the end of Part 1 (“Incentive”).

The next large-scale section complicates things on two levels. It plunges Blomkvist into the details of Vanger family history and Harriet’s disappearance, and it brings Lisbeth Salander’s life to a point of crisis. We learn her past as an orphan and a denizen of the streets and hacker subculture, living under the thumb of her guardian Bjurman. This section is rather long, about 150 pages, because it has to establish Lisbeth as a dual protagonist and show her stratagems for escaping Bjurman’s sexual exploitation. Blomkvist must also serve his short prison time in this segment.

I’d argue that the plot’s midpoint occurs on page 323, halfway through the book. Chapter 16 begins:

After six months of fruitless cogitation, the case of Harriet Vanger cracked open. In the first week of June, Blomkvist uncovered three totally new pieces of the puzzle. Two of them he found himself. The third he had help with.

These revelations propel Blomkvist into a lengthy investigation of serial murders, which requires him to hire Lisbeth as his research assistant. While the two follow up clues, they start an affair.

On p. 477, it seems to me, the climax begins. The investigation has cast suspicion on Martin Vanger, Harriet’s brother. Blomkvist hears Martin returning home. “That somehow brought matters to a head.” Blomkvist goes out to confront him. Two pages later Martin shows him into the basement. “Blomkvist had opened the door to hell.” Now scenes of Lisbeth’s research and return to the village alternate with scenes showing Blomkvist at the mercy of Martin in his torture chamber.

Because the central plot involves two mysteries, the climax is extended. I’d argue that the two mysteries, the serial killings and Harriet’s disappearance, are solved by page 560 or so. But there remains the matter of Blomkvist’s revenge on the plutocrat Wennerström, who had tricked him into printing a phony story.

That dangling plotline is tied up in the next chunk (pp. 562-628), which forms in effect a second climax. Thanks to Lisbeth’s research, Blomkvist and his partners prepare to publish an expose of Wennerström’s crimes in Millennium. The evening that Blomkvist goes on TV, public opinion shifts decisively in his favor, and as the translation has it, “Blomkvist’s appearance marked a turning point.” He has won, and so has Lisbeth, who has drained money from Wennerström’s offshore accounts.

The sixteen-page epilogue tells us that Wennerström, facing disgrace and jail, kills himself. By now the two protagonists have struggled up from below. Blomkvist redeems his reputation and becomes the toast of journalism. Lisbeth, poor and victimized by men, becomes independent and enjoys her stolen fortune. There remains only the question: Will the two unite romantically? A final scene replies with a very old plot devices that’s one of Larsson’s favorites: a chance encounter that triggers a misunderstanding.

So I’m proposing a 138-page setup, a 150-page Complicating Action, and a 154-page Development. If you consider my two climaxes a single stretch, you have a 149-page climax section. That makes the big parts roughly equal, with a tailpiece of 16 pages. Even though The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has nearly twice the page-count of The Ghost and crams in two protagonists and several plotlines, it displays the symmetry we find in the more compact book. The chief difference is between a comparatively short climax and a protracted one—the same difference we often find in classically constructed films. For these novels, and I suspect many others, the three-act/ four-part template provides a solid architecture for the plot.

Miracles, critical fantasies, or just tradition?

I won’t try to align the parts articulated in the novels with those we find in the finished films. The congruences are fairly close, once you grant that both films compress scenes and lop off characters and plotlines that are developed in the novels. Instead, I want to close by asking some questions.

Would novelists admit to consciously adopting this structure? If they don’t, or if we think it’s implausible that they would, we’re confronted with the charge that we’re simply projecting this structure onto the books. Are we and the writers of manuals shoehorning these plots into the three-act/ four-part format? Could we come up with equally persuasive patterns if we set out looking for seven or seventeen or seventy “acts”?

To take the last question first: Probably not. I think my analyses carve the films and books at the joints, more or less. One reason I like Kristin’s analytical method is that it hinges on characters’ goals and their pivotal decisions or reactions. These tend to be emphatic, well-articulated moments in the plot; a lot, as we say, depends on them.

True, there is some room to argue about which ones might be most far-reaching. You can propose alternatives, and I can change my mind. But the rival candidates for goals and decisions and major turning points aren’t likely to be radically different. We agree on most structural conventions, and our differences tend to be fine-grained, not gross.

Still, this sort of analysis arouses skepticism, and rightly so. How can writers and filmmakers achieve this neat structure without conscious planning? Can you follow the rules without doing so deliberately? Kristin offers an explanation that emphasizes the intuitive search for proportion in the creative process. She invokes Vivaldi concerti, medieval altarpieces, daily comic strips, and even the Great Pyramid at Giza as examples of balance among parts in both high and popular arts.

The evident use of proportions in many narrative films provides one more indication of the enduring classicism of the mainstream Hollywood system. Presumably what practitioners have intuitively assumed to be the optimum range of lengths for each part was discovered early on. It has been passed down the generations of filmmakers as a result of the simple fact that most practitioners gain their basic skills by watching a great number of movies (Storytelling in the New Hollywood, 44).

I think that there’s still a lot to learn about these templates. How are they disseminated among filmmakers? Why are we unaware of these parts while watching the film? They don’t stand out like chapter divisions in a novel. Or do we sense them subliminally? And how widespread are they? Do we find them in classic studio cinema of the 1920s through the 1950s? (Kristin thinks so, as do most writers of screenplay manuals.) Do we find them in films from other cultures and periods? If so, perhaps filmmakers elsewhere have found them to be reliable ways to engage viewers. Possibly these models were spread with the circulation of American movies.

I’ll provide my own epilogue by noting that the novelists’ borrowing of screenplay structures is a recent instance of a long-term process: the “cinefication” of other media. Today we call successful novels “tentpoles” or “blockbusters” or “locomotives,” and we say they’re “released” rather than “published.” What used to be called a series of novels is now likely to be called a franchise. It may be that many novelists have absorbed the lessons of screenplay manuals. If you wanted your book to be bought by a producer, why not make it like a film beforehand?

More abstractly, we have artistic transfer and technical influence. For a long time critics have argued that literary modernists like Faulkner and Hemingway, along with more popular genre writers, have tried for “cinematic” styles and have sought to imitate the “camera eye” in their narration. Today perhaps we see a structural influence as well: rules of film plotting mapped onto prose fiction. The next page-turner you read may have been engineered to flow across your eyes at the brisk pace of a Hollywood movie.

Several of my references to classical theorizing about act divisions are taken from Oscar Lee Brownstein and Darlene M. Daubert, eds., Analytical Sourcebook of Concepts in Dramatic Theory (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1981). For more on classical Greek drama’s structure, go here. You can read a brief summary of the history of act divisions in western drama here.

On the three-act screenplay structure as applied to independent films, see J. J. Murphy’s You and Me and Memento and Fargo. See also J. J.’s independent cinema blog.

Stephen Greenleaf’s “A Mystery in Three Acts” appeared in The Writer 109, 4 (April 1996). Ridley Pearson’s article “Getting Your Act(s) Together” appeared in Writer’s Digest 87, 2 (April 2007), 67-69, 85. For another application of three-act structure to the novel, go here. The author claims that “movies rather than books are easier to analyze in that the main plot points are visual.”

On The Ghost Writer, a useful interview with Robert Harris is here. An entry on Creative Loafing points out ambiguities and vague spots in the movie’s plot. A January 2008 draft of the script, which incorporates voice-over narration, is available here.

The most influential account of how American novelists adapted cinematic techniques is Claude-Edmonde Magny’s Age of the American Novel: The Film Aesthetic of Fiction between the Two Wars. See also Keith Cohen’s Film and Fiction: The Dynamics of Exchange.

The Ghost Writer.