Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

A Monument to Mystery: Martin Edwards’ THE LIFE OF CRIME

DB here:

In my early teens I bought murder mysteries from the legendary Claude Held of Buffalo. Lacking a checking account, I blithely sent through the mail dollar bills and even coins taped to the order. I still have S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen hardbacks from those days, but my most treasured item is a first edition of Howard Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (Appleton-Century, 1941).

Published on the hundredth anniversary of Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Haycraft’s survey of mystery fiction sought to establish the legitimacy of the genre. It became the authoritative source on the subject, and it’s still worth reading. Even then I had the habit of writing notes in the margins, and I’m ashamed of the jejeune scrawls that dare to call Haycraft to account. (“This is quite incorrect.”) Still, Haycraft confirmed my love of the subject and showed me what a serious literary history might look like. (Once more the adolescent window.)

Thirty years later came another powerful overview of the genre’s history. Julian Symons’ Bloody Murder aka Mortal Consequences (Harper & Row, 1972) was a revision and partial rejection of the standard story. Haycraft was a critic, but Symons, who reviewed mystery fiction, was also an accomplished novelist. The book is often harsh in its critical judgments, as when Symons downgrades Sayers as “pompous and boring” and classifies many of her peers as Humdrums. Symons promoted instead what he considered the strongest contemporary trend, the shift from puzzles to character-driven and socially critical writing. His subtitle sums up his argument: “From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel.”

Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

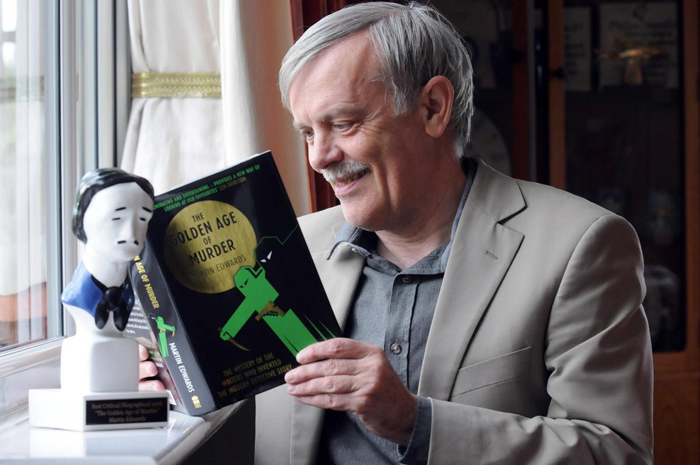

Martin Edwards’ Wikipedia entry makes your head swim: the man is a true polymath. Trained in the law and still a consulting solicitor, he’s a prolific, highly lauded mystery novelist as well. He has won virtually every literary prize in the field, not least the Diamond Dagger, the British Crime Writer’s Association highest award. His most recent novel, published on 1 September, is The Blackstone Fell.

Edwards is also recognized as the premiere historian of the genre in English, thanks to his many books, including The Golden Age of Murder (2016) and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books (2017). As if all this didn’t keep him busy enough, he writes a lively blog, “Do You Write Under Your Own Name? And he’s incapable of composing a graceless sentence.

So it’s no surprise that The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators is a monumental achievement. At 724 pages, resplendent with a burgandy string bookmark and beautiful colored end papers, it’s a triumph of modern publishing, and a stupendous bargain. (It’s currently going for $26.39 from the publisher.) The hardcover is currently ranked as #1 in Amazon’s Mystery and Detective Literary Criticism (with the audible book as #2).

The bulk and detail of The Life of Crime will incline many to treat it as a reference book. It functions superbly as that, thanks to a careful index, but it is even more. It provides a nuanced, reliable history of the genre; it offers rich insights into storytelling technique; and it teems with unforgettable stories of mystery authors. As the subtitle promises, it’s an account of both books and the people who create them.

Crime waves

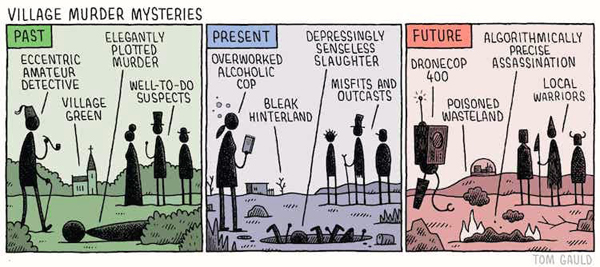

By Tom Gauld.

At the end of the 1930s, Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure could confidently sum up the standard trajectory. The detective story developed from Poe to Gaboriau to Conan Doyle, and then to the Golden Age of Christie, Sayers, Carr, Van Dine, Queen, and many others. Haycraft acknowledges the accomplishments of the 1920s British school, their US counterparts, and the emerging hardboiled trend typified by Dashiell Hammett. (Chandler was still a secondary figure when Haycraft was writing.)

Following the most self-conscious writers of the 1930s, Haycraft recognizes the need for the mystery to move closer to prestige fiction. He suggests it do so through a greater emphasis on characterization and on social commentary: the “novel of character” and the “novel of manners.” He sees the hardboiled trend as a variant of the novel of manners and warns that in its pure form it will soon wane. It “is beginning to become just a little tedious from too much repetition of its rather limited themes.”

Time would prove him wrong. The 1940s saw new variations in the hardboiled school, most evident in the spectacular popularity of Mickey Spillane. In Bloody Murder Symons faulted Haycraft’s analysis on other grounds. He failed to discern the growing power of the “crime story” as distinct from the detective tale. Thanks largely to Hammett, violence, eroticism, abnormal psychology, and official corruption moved to the center of writers’ concerns.

For Symons the apparatus of footprints, altered wills, and bodies in the library was surpassed by the rise of suspense fiction and the police procedural. Patricia Highsmith, Symons declared, is “the most important crime novelist at present in practice.” She, along with Margaret Millar, John Bingham, and Symons himself (!) typified the potential of the modern crime story, with Ross Macdonald revising the classic detective plot through the concern for “personal identity and the investigation of the past.”

Edwards holds Symons in high regard but has a more pluralistic conception of the genre’s history. The Life of Crime reaches back to the eighteenth century (William Godwin’s Caleb Williams) and ends with surveys of Nordic noir, East Asian detection, the contributions of contemporary women and minority writers, and the fashion for historical mysteries. The 55 chapters are organized around periods, trends, and exemplary figures. They survey not only crime literature, but plays, films, and television shows.

The broad picture Edwards paints shows how changes in the genre coincide with broader social dynamics. He’s especially good on the impact of World War I on an entire generation of writers and readers. Likewise, he traces how World War II spurred the rise of psychological thrillers in fiction and film, as well as the new platform of paperback originals.

Edwards’ comparative approach shows that the clash of Golden Age and hardboiled tendencies isn’t as drastic as Symons suggested. Symons saw Hammett and Chandler as in rebellion against the “rules” of the classic whodunit. Edwards shows that the hardboiled writers respected not only many Golden Age authors but also many of their conventions. For Edwards, the mystery tradition offers writers a range of creative choices not limited to a single notion of form or style.

An unabashed fan of Christie, Sayers, and their peers, Edwards is especially good at tracing the continuing influence of the Golden Age on contemporary work around the world. Who would have predicted the obsession of contemporary Japanese novelists with impossible crimes and narrative tricks, stemming from the canonical Edogawa Ranpo’s love of classic artifice? Popular examples are Shimada Soji’s Tokyo Zodiac Murders (1981) and Higashino Keigo’s The Devotion of Suspect X (2006). Edwards introduced me to a remarkable “book” by Awasaka Tsumao, The Living and the Dead, which, thanks to the Golden Age trick of sealed pages, contains a short story that disappears as you read the novel. The author, not coincidentally, is a magician.

One of the most striking assets of the book is the endnotes at the end of each chapter. Far from academic citations, these notes are often wide-roaming discussions of topics mentioned in the text. So, for instance, R. Austin Freeman’s worry that fingerprints could be fabricated gets this elaboration in an endnote:

Fingerprinting was used by Scotland Yard from 1901, but Sherlock Holmes examined for a thumbprint eleven years earlier, in The Sign of Four. In the US, fingerprint identification was central to the plot of Pudd’nhead Wilson, by Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens). But Freeman feared that reliance on uncorroborated fingerprint evidence could lead to miscarriages of justice. Hammett’s story “Slippery Fingers” reflects a similar concern, and some experts share it to this day (113, n8).

The dozens of reader-friendly endnotes offer a wealth of supplementary information, including recommendations for further reading. Any chapter’s supplements could provide scholars a host of leads for further research. These notes typify the generosity of the book, whose vastness conveys not pedantry but an eagerness to share information and excite the reader’s curiosity.

Edwards’ pluralism amounts to more than intellectual generosity. His book’s global sweep illustrates the astonishing fecundity of the genre in varying cultural contexts; it also shows how malleable its conventions are. I think he shows how fertile a tradition of popular storytelling can be–especially when it has the power to cross boundaries of time, place, and language. No reader of The Life of Crime can believe that this genre has run out of steam.

The toolbox

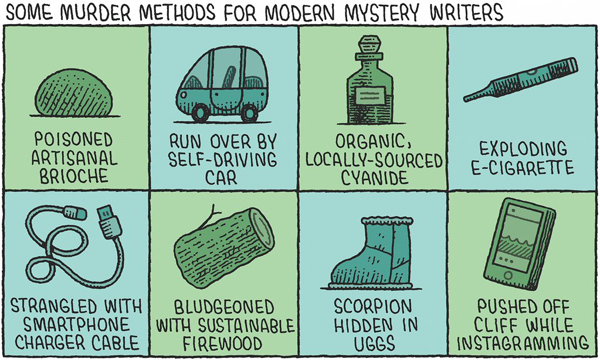

Tom Gauld, The Guardian (9 January 2016).

Most authors surveying the history of mystery discuss the narrative techniques employed by the various schools. Unlike most genres, mystery fiction’s identity depends on duplicitous manipulations of time, viewpoint, and narration. To conceal the crime and its perpetrator, the author must carefully select who knows what and when. The goal is to baffle both the investigators and the reader, with not only clues on the scene but also hints in the manner of telling. Needless to say, those clues and hints may be misleading.

Both Haycraft and Symons dutifully invoked the conventions of Golden Age bafflement. Haycraft treated them as the source of the genre’s distinctive pleasures, while Symons sometimes deplored their reliance on implausibility and coincidence. (He wasn’t, however, as demanding as Chandler, who famously remarked that “Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.”) As a writer sympathetic to Golden Age artifice, Edwards is eager to explore the whole range of devices available for mystery plotting. At this level, The Life of Crime is an encyclopedia of creative options available to the genre. Not surprisingly, Edwards’ wide compass shows that many “modern” techniques have distant historical precedents.

Aficionados recognize several ploys: false identity, faked death, slippery alibis, dying messages, equivocal clues, the absent clue (the dog that doesn’t bark in the night-time), the double bluff (X seems to have done it; wait, X is too obvious a suspect; nope, X actually did do it). Edwards goes beyond these to track how storytellers have used multiple narrators to cloud the situation and sharpen characterization. He shows the persisting power of the “inverted story,” the structure that shows the criminal committing the crime and then follows the detective’s exposure of guilt (the Columbo strategy). He devises a new term to accompany the “whodunnit” and the “howdunnit”: the whowasdunin, the plot that withholds the identity of the victim until the climax. This is a wider trend than I had realized. The same goes for the inclusion of letters and diaries in the text, which feels modern to us but actually goes back centuries.

And of course he doesn’t neglect reverse chronology, highlighted in one of those endnotes that can keep you busy for weeks:

This method of storytelling can dazzle, but only if the writers’ craftsmanship matches their courage. The possibilities are shown by Iain Pears’ novel Stone’s Fall, Jeffery Deaver’s The October List and Ragnar Jönasson’s Hulda Trilogy as well as by Simon Brett’s play Silhouette, Christopher Nolan’s film Memento, Harry and Jack Williams’ TV series Rellik, and Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith’s “Once Removed,” a witty and brilliantly economical episode of Inside No. 9 (612n19).

In all, Edwards’ sensitivity to innovations allows his book to be a stimulating source of craft practices to anyone who wants to write a mystery.

Mystery and misery

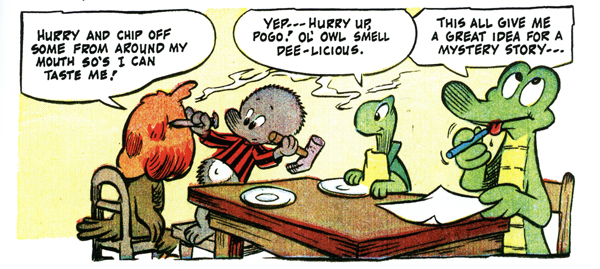

Walt Kelly, “The Big Comical Book Business” (Pogo Possum no. 5, 1951).

Sara Paretsky took up crime writing after contemplating poisoning her husband. Composer George Antheil, outraged by the attacks on his Ballet mécanique, wrote a novel in which barely disguised music critics were extravagantly murdered. Mary Roberts Rinehart refused to make one of her servants her butler, and he retaliated by trying to shoot and stab her. Patricia Highsmith smuggled her pet snails into England by hiding them in her bra, “six to ten per breast.”

At least as intriguing as the crimes in their books are the personal histories of the authors. Edward starts most chapters of The Life of Crime with an arresting account of one writer’s life. It’s often a catalogue of miseries. Alcohol damaged Poe, Hammett, Chandler, Highsmith, Craig Rice, Cornell Woolrich, and innumerable others. Drugs figured in the careers of Wilkie Collins (laudanum) and S. S. Van Dine (morphine). Suicide attempts and mental illness were distressingly common as well.

These usual artworld excesses are enhanced by mystery-mongers’ distinctive dose of weirdness. After a devastating traffic accident, Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gas Light, became obsessed with his brother Bruce. He refused to speak to Bruce’s wife and declared it was a pity that he, Patrick, wasn’t a woman; then he could have married Bruce. Bruce, a mystery writer himself, published a novel called A Case for Cain, in which one brother beats another to death with a golf club.

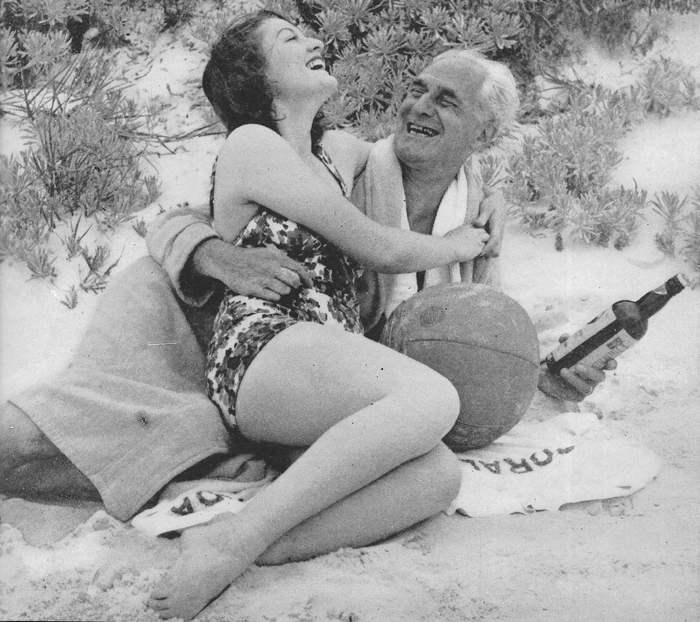

The juxtaposition of suffering and creative energy is marked. On the brink of financial ruin, morphine-addicted Willard Huntington Wright persuaded a distinguished publisher to issue three mystery novels under the pen name S. S. Van Dine. They sold in the millions and led to a long-running series. Rupert Croft-Cooke, after serving a prison term for homosexuality, fled England for Tangier and published dozens of detective novels under the name Leo Bruce. He also wrote twenty-seven volumes of autobiography called The Sensual World. Agatha Christie’s disappearance in 1926, probably due to temporary amnesia, was a response to her mother’s death and her husband’s infidelity. It didn’t hamper her immense productivity.

With his novelist’s eye, Edwards sympathizes with his subjects, but just reporting the facts still leaves you reeling. Of William Lindsay Gresham he records excessive drinking, occasional violence, and suicide attempts. When Nightmare Alley was bought for Hollywood, Gresham moved into a mansion. “He dabbled in folk-singing, and tried to ease his misery by exploring Dianetics, the precursor of Scientology, and taking an assortment of lovers. On one occasion he’d tried to hang himself on a hook, but it broke.” Years later, he killed himself with sleeping pills. “Legend has it that his pockets were stuffed with business cards bearing the inscription: No Address. No Phone. No Business. No Money. Retired.”

Edwards avoids sensationalism, but it’s good to remind us that much of the entertainment we enjoy was built on a lot of personal pain.

The Life of Crime is, then, a book in four dimensions: reference volume, historical survey, armory of literary techniques, and biographical accounts of major artists. To succeed with any one of these is remarkable; to succeed with all of them is something of a miracle. It will remain an indispensable guide to its subject.

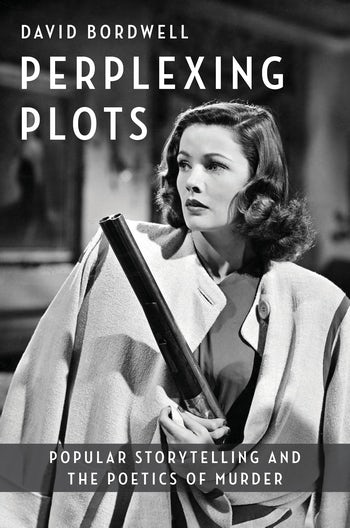

Full, if belated disclosure: I read Martin’s book in manuscript and offered some comments, for which he kindly thanks me. He has also provided an endorsement of my forthcoming Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder.

The Life of Crime is already getting splendid reviews in the press and on the Net. There’s an illuminating interview with Edwards on the American Scholar podcast.

You’ll find plenty of funny cartoons on writing, including writing mysteries, from Tom Gauld here and here.

Martin Edwards. From the Warrington Guardian.

PERPLEXING PLOTS: On the horizon

DB here:

In the Before Times, I didn’t watch much fictional TV. Our modest monitor was chiefly a delivery device for news, DVDs, and Turner Classic Movies. We followed The Simpsons, and I came to like Deadwood and Justified, but usually the time commitment demanded by long-form series put me off. I gave my curmudgeonly reasons long ago on a blog entry.

But over the last nine months, forced to stay home, I dipped my toe in the water. Streaming made it easy to catch up with shows I’d never seen and offered a plethora, or rather a glut, of original series. This still-limited experience of long-form shows confirms the presence, if not the dominance, of what Jason Mittell in his excellent book calls Complex TV.

Many shows mix timelines with abandon. Both the documentary WeWork; or, The Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn (2021) and the docudrama WeCrashed (2022) open near the end of the story action and then flash back to show what led up to it. (This crisis structure became especially common in 1940s Hollywood.) Billions, an older series I’d never followed, contains an episode (Season 2, 2016) that jumps to and fro among a funeral, scenes taking place before it, and scenes afterward, several attached to different characters. In the Hulu series Dopesick (2021) a sliding timeline graphic shifts among many periods and character viewpoints; to keep track of it all you’d need to make a spreadsheet. (It would amount to something like the whiteboard used in writers’ conference rooms to map out the unfolding series.) I can’t recall all the shows that friends have recommended as examples of daring play with narrative.

Of course all this isn’t news. For years both indie films and Hollywood blockbusters have offered complicated segmentations, broken timelines, and splintered viewpoints, with contradictory replays and unreliable narration. Still, it was good to be reminded that the problem I’m tackling in my latest book is still current—indeed, dominant. We may have to wait for the new Justified series to see a return to straightforward linear storytelling.

When and how did viewers develop the skills that lets them appreciate the New Narrative Complexity? This is at the center of Perplexing Plots: Popular Narrative and the Poetics of Murder.

Maybe we were always smart

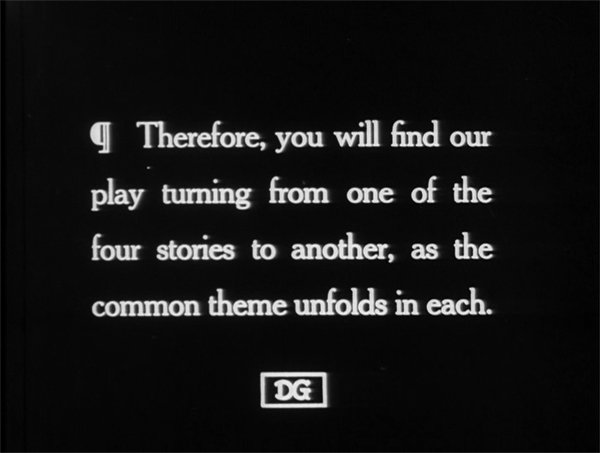

Intolerance (1916).

There’s a view, most eloquently posed by Steven Johnson in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that these comprehension skills are a fairly recent development. They stem from rising IQ levels, growing facility with video games, and other cultural phenomena after the 1970s. People are now smarter consumers of narrative than they were in the days of I Love Lucy.

I argue instead that popular narrative has been cultivating these skills across a much longer period, and they firmly took hold in mass culture at the start of the twentieth century. You can get a summary of my argument here on the Columbia University Press site.

Most broadly, a lot of (now-forgotten) mainstream plays and novels were as experimental in shifting point-of-view and juggling time frames as any we find today. For example, we celebrate backwards stories as typical of the demands of modern storytelling. The play and film Betrayal and the films Memento and Shimmer Lake are among many recent media products presenting the scenes in 3-2-1 order. But this possibility was discussed by a prominent critic in 1914, and soon a major woman actor wrote a play that used reverse chronology. There followed other examples, not least W. R. Burnett’s novel Goodbye to the Past (1934) and the Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (1934).

Some will argue that innovations of popular narrative are dumbed-down borrowings from modernist or avant-garde trends. I try to show this process as a two-way dynamic: modernism borrowing from popular forms, mainstream storytellers making modernist techniques more accessible. But we also find that popular storytelling has its own intrinsic sources of innovation, as with the reverse-chronology tale and Griffith’s application of crosscutting to different time frames in Intolerance (1916).

So it seems to me that audiences have long been capable of tracking the sort of fancy narrative devices we find now. They encountered them in many types of stories, and I devote the first part of Perplexing Plots to a quick survey of developments in novels and plays. (Yes, Stephen Sondheim is involved.) Audiences have learned to enjoy self-conscious artistry, an awareness of form and technique–what one disapproving reviewer of Wilkie Collins called “the taste of the construction.”

Such a taste was cultivated in depth in one mega-genre. That was a major training ground for giving us the skills to follow complex, sometimes deceptive storytelling.

Mystery on my mind

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Ever since my teenage years I’ve been a fan of mysteries on the page and on the screen. I’ve smuggled discussions of detective stories and crime thrillers into many of my books, and my last one, on 1940s Hollywood, did a lot with this form of storytelling–largely because it was so central to the films of that era.

Perplexing Plots in a way turns Reinventing Hollywood inside out. The earlier book put movies at the center while showing how filmmakers borrowed from mysteries in other media. The new one puts fiction, theatre, radio, and even comic books at the center, discussing how mystery conventions developed–and showed up in films as well. The two books complement each other, I guess, although the historical sweep of the new one runs from the 1910s to the present.

Mystery was essential to many classic novels, from Wuthering Heights to the tales of Henry James and Joseph Conrad. Dickens and Wilkie Collins made mystery a major attraction of “sensation fiction.” In the twentieth century, the Anglo-American whodunit, the suspense thriller, and the hardboiled detective tale–to take the three most well-known genres–trained audiences in appreciation of nonlinear plotting, misleading narration, and subterfuges of concealment.

A Western or a science-fiction tale may include a mystery, but it doesn’t have to. In mystery fiction, the suppression and misinterpretation of information is foundational to the genre itself. A mystery depends on a “hidden story,” which will often be revealed out of chronological order and refracted through the minds of several characters. At a meta-level, the genre cultivates a gamelike approach, where we expect the author to give with one hand and take away with the other. Across history, a mass audience became sophisticated consumers of complex narratives.

I trace how this happened with Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Marie Belloc Lowndes, E. C. Bentley, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Daphne du Maurier, Cornell Woolrich, and many other authors. I spend a lot of time analyzing both plot structure and the texture of the writing. If nothing else, I hope to show that this genre encourages not only great ingenuity in plotting but also subterfuges of style.

I trace this process into the 1940s, when in my view the basics of contemporary techniques crystallized and become widespread. The book then looks at some case studies of how crime novels and films have explored the various possibilities of broken timelines, disparate viewpoints, and misleading narration. I devote chapters to Erle Stanley Gardner, Rex Stout, Patricia Highsmith, Ed McBain, Donald Westlake, Quentin Tarantino, and Gillian Flynn.

I could have gone much farther. Every reader will have a long list of authors I’ve omitted. But I had to stop somewhere! And I decided to concentrate on some of my favorites. The result is, if nothing else, appreciations of the verbal artistry of some underestimated storytellers.

This isn’t to say that audiences of 1920 could have easily followed Inception (2010) or Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). Storytellers have pushed forward, revising schemas that are widely known and teaching us to recognize the tweaks they’ve introduced. Audiences have accumulated a repertory of skills, built upon their experiences of other formal experiments. Those experiences, I want to show, have been crucially shaped by the conventions of mystery narratives.

Looking back on other things I’ve written, I find that I’m repeatedly concerned with finding beauty in popular genres and modes of storytelling. My studies of Hollywood, Hong Kong cinema, Japanese films, and other forms of cinema have taught me that mass entertainment harbors not only pleasures but also precise craft and daring artistry. While I’ll never give up my love of disruptive and “difficult” work, I find that films appealing to wide audiences, from His Girl Friday and Meet Me in St. Louis to the masterworks of Ozu and Hitchcock and Lang, have a unique power. Fortunately, we don’t have to choose.We can have them all. Perplexing Plots is my effort to show that storytelling craft in its humblest forms can yield its own rapture.

Advance appraisals of the book can be found here. (Click on “Reviews.”) It’s due to be published in January 2023. In the months ahead, from time to time I hope to blog more about the ideas in the book. In the meantime, I wait for the new installment of Slow Horses.

There are too many people to thank here; my debts are recorded in the book’s Acknowledgments. But at least I want to thank John Belton for supporting the project, and Philip Leventhal and Monique Briones at Columbia University Press for their swift and efficient work on the manuscript. And love to Kristin, who took care of me while I finished the book and recuperated from surgery.

The Lady Vanishes (1938).

Once upon a time in Hollywood, again: Tarantino revises his fairy tale

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019).

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

–Quentin Tarantino

DB here:

Tarantino has often embraced print-based texts that revise or complement his films. He’s shared screenplays that differ sharply from the finished product, and written graphic novels derived from Django Unchained. Now he’s gone farther. He’s published a novelization that playfully modifies the film’s title: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, without the three-dot ellipsis.

Tarantino has often embraced print-based texts that revise or complement his films. He’s shared screenplays that differ sharply from the finished product, and written graphic novels derived from Django Unchained. Now he’s gone farther. He’s published a novelization that playfully modifies the film’s title: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, without the three-dot ellipsis.

Some will say, rightly, that the book is another instance of today’s tendency toward cross-platform narrative, what Henry Jenkins calls transmedia storytelling. As such it sells more stuff, builds fan connoisseurship, and provides academics like me more to talk about.

But I think it does more. Tarantino has long borrowed from popular literature, particularly crime fiction. (The book I just finished writing tries to trace out some of his debts.) With his novelization, he returns the favor by transferring some of his creative methods to the long-form prose format. Moreover, he realized that some conventions of two genres–the movie novelization and the Hollywood novel–could be steered in fresh directions. What he provides, I think, is not only a fresh path through the story world that will tease fans but also another of his accessible experiments with narrative form. As a bonus, the book shows the author to be a stimulating historian of American studio cinema.

Of course what follows contains spoilers for both the film and the book. But since you’ve had a good stretch of time to catch the film, and since the book currently sits at the top of the New York Times bestseller list, I’m hoping a fairly close analysis won’t scare away many readers. Even if you don’t read on, maybe the mere existence of this entry will send you to the two items in this intriguing multimedia package.

TV or not TV: What is the question?

The film weaves together the doings of actor Rick Dalton, stuntman Cliff Booth, and actor Sharon Tate, over the space of a few days. Rick has been hired to play a villain in a pilot for the TV series Lancer, and Cliff, no longer employable as a stuntman, fills his days serving as Rick’s personal assistant, maintenance man, and boon companion. Sharon, wife of Roman Polanski, lives a life of partygoing, shopping, and occasional screen performing. These characters cross paths with members of Charles Manson’s cultist “Family,” who in 1969 actually murdered Sharon and her guests in a home invasion. In the film, things turn out differently. The novelization takes up these characters and basic incidents but recasts them.

The typical novelization is published to promote a film just before its film’s release, and it sometimes serves as an enduring fan memento or a contribution to a franchise’s “canon.” The writer is often working from a screenplay or a detailed synopsis, so changes made in the later phases of production can render the finished film quite different from the book. But Tarantino’s novelization comes two years after audiences saw his film. Many readers have already seen the film, possibly several times, so they will be sensitive to deviations from the original. Tarantino exploits that knowingness in ways that are sometimes traditional, sometimes striking.

As you’d expect, a lot of the book is devoted to filling in the backstory of the three major characters. Flashbacks show how Sharon got to Hollywood and how Cliff became a stuntman (and a killer). Like other novelizations, Tarantino’s fleshes out subsidiary characters as well, providing the sort of enrichment of the story world that fans enjoy. And some scenes omitted from the finished film are dwelt on in the novel. For example, in the original pilot the Lancer half-brothers meet when they accidentally come to town on the same stagecoach. (Sorry about the punk YouTube rip.) Tarantino, always obliging, shot the scene in his own way and provides it as a bonus material on the disc.

The woman in the TV show is the patriarch’s ward, but in the novel and the film she becomes his daughter Mirabella, and thus the men’s half-sister.

Because a novel can plunge us more deeply into characters’ minds, Tarantino can share the thoughts of Cliff, Rick, and Sharon, as well as secondary figures like Squeaky Frome, Pussycat, Jay Sebring, Roman Polanski, and Manson himself. This widening of perspective alters Tarantino’s habitual storytelling method.

I’ve argued that his films rely on block construction, longish “chapters”attached to one character or set of characters. Whether offering us present-time scenes or flashbacks, they remain fairly self-contained chunks, often set off by titles. As a film, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood broke with this scheme somewhat and presented more alternation among shorter scenes, though still anchored to one of the three main characters.

The novel is even more chopped up, presenting the story in twenty-five chapters, many of them including shifts in time or viewpoint. The transitions are clearly marked, with inner monologues rendered in italics and verb tense differentiating the present-time story from flashbacks. In all, the short, sharp scenes sample a broader panorama of Hollywood life than we find in the film, yielding something more like a network narrative.

The same expansion goes for time. The film leaves Rick’s future somewhat open, but the book sketches in his career after his confrontation with the Family marauders. We learn fairly early in the book that in the 1970s he will cut down on his drinking, an important motif in the book. We also learn the career arc of Trudi Fraser, the little girl with whom Rick performs in the Lancer pilot. A more conventional novelization probably wouldn’t include this anticipatory material, because it would foreclose developments that filmmakers might want to conjure up in a sequel.

Still, Tarantino does adhere to his block aesthetic in an odd way. Big chunks of the Lancer backstory not dramatized in the TV episode are given to us in dedicated chapters, written as if they were extracts from another novel. Recounted by an omniscient narration, they treat the Lancer family history on the same fictional level as the contemporary Hollywood plot. Why? I’ll try to explain below.

Tarantino has experimented with viewpoint shifts and replays throughout his work, most notably in the repeated money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown. Now, like a writer of fan fiction, he can extend the strategy to prose. So an episode registered by one character in the film can be filtered through another in the book. The most extended viewpoint displacement involves Cliff’s visit to Spahn ranch. In the film, we’re attached to him throughout, but in the book everything that happens in that scene is restricted to what Squeaky sees and hears. Viewers are likely to remember Cliff’s fruitless conversation with George, so the replay allows Tarantino to build up a more sympathetic portrait of Squeaky than we get in the film.

Two other narrative strategies are more surprising, but both target readers’ memory of the film. First, the book begins with an office conversation between Rick and agent Marvin Schwarz that echoes the restaurant meeting that opens the film. The reader is likely to think that the book’s ending will resemble the film’s end, which shows the Manson followers attacking Rick’s house rather than Polanski’s. This is the most drastic “alternative history” in the film, like the assassination of Hitler in Inglourious Basterds.

But the reader who’s seen the film will be thrown off on page 110. In a flashforward to March 1970, Rick gets a call from director Paul Wendkos inviting him to join a project. Prompted by a teasing remark by Wendkos, the narration quickly summarizes the summer 1969 invasion and its aftermath before briskly scanning the effect on Rick’s career in the seventies. If you’ve seen the movie, now you can’t be sure what will happen at the end of the book. Will the book’s climax replay the movie’s firefight? Or will something else tie up the plot? Call it show-offish or shrewd, Tarantino’s anticipation of the film’s ending has activated the reader’s awareness of his choices about narrative structure.

Related to this replacement-ending problem is a shift in rendering the filmmaking process. The film shows two scenes of the Lancer pilot being filmed. In the first, Johnny Madrid/Lancer rides into town, shoots down a hired gunman, and discusses joining Caleb DeCoteau’s gang. In the second scene, Caleb holds Lancer’s daughter Mirabella hostage while he arranges for ransom from Scott Lancer.

But the novel version only alludes to these scenes; it doesn’t dramatize the filming of them. The meeting of Johnny and Caleb is presented as part of the inserted Lancer “novel,” while the hostage parley is merely mentioned. The only scene that the book describes being shot is one for Rosemary’s Baby.

Instead, the novel dwells on what happens before shooting. On a porch Rick and Trudi discuss acting in general, and later she urges him to scare her during the hostage scene. Tarantino suppresses the act of filming this big scene, simply indicating laconically: “And Caleb and Miranda act out the scene.” Likewise, Sharon Tate, recalling her slapstick scene in The Wrecking Crew, dwells on what happened before the camera rolled.

Why the shift from filming to preparation? I’ll suggest one possibility a bit later.

Palimpsest of a period

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a “Hollywood novel.” Typically that genre centers on the rise and fall of a fictional star (Inside Daisy Clover) or an executive (The Last Tycoon), with glimpses of production woven in. The fictional characters dominate the plot, but there are references to actual people and studios, which (libel laws being what they are) serve mostly as colorful background. Tarantino follows these guidelines, but he offers a deeper analysis of American film history than any other Hollywood novel I know.

His isn’t a dry historical approach, though, because of the flamboyance displayed by the narrator. Instead of giving us a prudent bystander’s account in first-person narration, as What Makes Sammy Run? does, the book presents an omniscient yarn-spinner addressing us through phrases like “And bear in mind,” “Now, truth be told,” and “You must remember.” At the same time, efforts at purely literary bravado mix the cheap tabloid alliteration of James Ellroy with the weirdness of Cornell Woolrich.

Still, none could really match Aldo Ray when it came to publicly played-out poignant pity.

The six powerful equines come to a gentle stop.

The diminutive Polanski sports bed head on his cranium.

Who’s speaking? This narrator is at once omniscient and lightly personified. The Lancer segments are straight Western-novel narration, except when they’re not.

With his light Texas twang, Monty sang out, “Royo del Oro, last stop!” The backlit sunshine rays filtered through the gauze-like brown dust in the way, a hundred years from now, all cinematographers of western movies would hope to duplicate.

An “I” almost never creeps in, but throughout we’re hearing the Tarantino who produces interview patter and whose screenplays insert wise-ass stage directions.

Freddy finishes his playing-possum piss (Reservoir Dogs).

Everyone is smiling except you-know-who (Pulp Fiction).

From the floor, the bloody, sweaty, and in excruciating pain (she’ll probably lose that leg) German movie star says to the two American soldiers she’s just meeting for the first time. . . . (Inglourious Basterds).

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood goes some way to confirming Tarantino’s repeated claims that when he stops making movies, he’ll turn to novels. I will read them.

Every Hollywood novel is in a sense an alternative history, I suppose, but this unpredictable prose helps prepare us for something peculiar. Start with the time frame. The first and longest stretch of the film takes place on Friday 7 January 1969 and the following day, and these chapters are tagged with time indications. The film then skips ahead to the day and night of 10 August 1969, with the attack on Rick’s home. The book adheres to the February dates but as we’ve seen it “spoils” the film’s climax by announcing the massacre fairly early on.

The central action of the book confines itself to the two days when Rick meets Schwarz and shoots the Lancer pilot, on 7-8 February, 1969. But that chronology is thrown off by another tag. After chapters presenting the day and evening of Friday the 7th, a new chapter indicates that Pusssycat’s Kreepy Krawl (another Ellroyism) takes place at 2:20 AM on that day. It’s either a flashback to an early-morning period before the previous four chapters (why?) or a scene taking place after the earlier chapters, and so is occurring at 2:20 on the 8th, not the 7th.

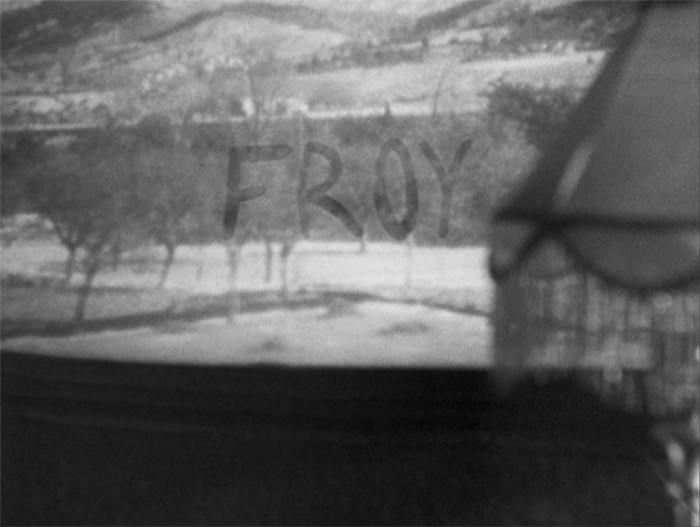

The Krawl anomaly is an early indication that a misaligned calendar governs the whole book, as it did the film. The actual Lancer pilot was shot in 1968, not 1969. Tarantino has merged events of one year (Rick’s career crisis, the Lancer shoot) with those of a later one (the actual Tate-LaBianca murders).

The typical Hollywood novel inserts made-up stories into a world of real ones, but Tarantino goes further. Your typical director would have pasted Rick on the cover of Time, but Tarantino goes for Mad. Your average movie-geek director would have had Rick reading an actual western novel, maybe Hombre in homage to Elmore Leonard. Instead, Tarantino invents a novel, Ride a Wild Bronc, by the real author Marvin H. Albert, because he wants a parallel between Rick and that book’s hero Easy Breezy. (The fact that Albert himself wrote many novelizations is a bonus.) Likewise, amid a flood of information about genuine Paul Wendkos films and stars therein, Tarantino deletes one actor (James Franciscus) from Hell Boats (1970) to cast the fictitious Rick in the part.

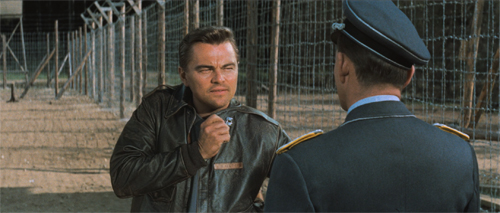

The substitution gambit is literalized in the film, when we learn the gossip that Rick supposedly just missed getting the McQueen part in The Great Escape (1963).

A comparable substitution conceit in the book is the jumble of publisher advertisements printed in the back. What could Tarantino’s book promote? Other books of the period published by Harper, of course: Oliver’s Story (1978), Serpico (1973), and Leonard’s The Switch (1978). The dates suggest that the “original” version of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was published in the late 70s, and this accords with hints in the narration and the book’s design. These period ads sit alongside one for the fake Ride a Wild Bronc and one for a purported hardcover edition of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (fake? forthcoming?).

Yet these dabs of phony history allow the book to float some genuine historical analysis. The constant references to obscure movies and TV shows might be taken as merely Tarantino’s nerdy self-indulgence. In fact, these citations fit into a fairly coherent cross-section of the period’s filmmaking and film culture, with the trends filtered through the business decisions and personal tastes of his characters. 1960s Hollywood turns out to be a palimpsest.

One layer is the fading of the studio system, reflected in agent Schwarz’s boast that he handles old royalty like Farley Granger and Joseph Cotten. Rick expresses his admiration for classic B-picture directors Wendkos and William Witney. Sharon’s backstory, when she hitched a ride to LA, reminds us of the enduring Hollywood myth of fresh-faced outsiders breaking in.

There’s also the new competition from European genres and overseas art films. Cliff, who scorns Antonioni and Resnais, is a big fan of Kurosawa and I Am Curious–Yellow. Now a European arthouse director has made a smash American hit, Rosemary’s Baby, and Rick fantasizes being tapped by Polanski. By contrast, Rick is reluctant to venture into spaghetti westerns, the new territory for a has-been US star.

“TV,” people used to say, “gets ’em on the way up or on the way down.” That’s been pretty much Rick’s career trajectory. Broadcast television has disrupted everything. B-directors like Wendkos shift between the two media, but the A-list older stars can’t sustain a series. Still, the narrator admits that some of these “sought to subvert their personas,” as Henry Fonda did in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Young talent is on the make. James Garner, James Coburn, and many other TV stars can jump to film, while Lee Marvin can shift from B-film villainy to TV heroism (M Squad) and return to films to play dark lead roles. The most shining example is Steve McQueen, who after his series Wanted–Dead or Alive became a top film star. In Tarantino’s film, he’s briefly seen commenting on Polanski’s ménage, but in the book McQueen haunts Rick’s life. The misbegotten anecdote about The Great Escape follows him everywhere.

At forty-two Rick is caught between two trends. He’s loyal to older directors and a classic genre, and he hates Eurowesterns and the counterculture. But to keep working he’s in competition with “the three Georges”–Peppard, Maharis, and Chakiris. Ten years ago he had his own series. Now he must wear a mustache and a biker wig and be the bad guy shot down by the newest “swinging dick.”

Said dick would be, in the Lancer pilot, James Stacy, to whom an entire chapter is devoted. He is the next failed McQueen, the young paladin who started memorably on Gunsmoke but now realizes that the clean-cut bad boy is on the way out. He admires Rick’s early work and envies Rick’s “fucking fly” look as Caleb. He yearns to wear a mustache.

The TV western has developed its own conventions, which Tarantino’s novel filters through the characters’ awareness. Schwarz introduces us to the antagonism between the series hero and the heavy, emphasizing that with every one-shot appearance, the guest star’s image suffers. After Rick reads the Lancer script, he admires its boldness in choosing as a protagonist Johnny, the sort of cocksure hothead who’d normally be shot down in the last act. Trudi is well aware that she is “just the ‘little tyke’ series regular.” More broadly, the book’s narrating voice realizes that westerns are based on “the man of principle pushed past his breaking point and beyond his nature. Most of Greek tragedy, half of all English theater, and three-quarters of American cinema operated from this premise.”

Men in war and at work

Men in War (1957); Aldo Ray on left.

The book spares some thoughts for women working in Hollywood. Schwarz’s secretary Miss Himmelsteen winds up becoming a talent agent who also performs fellatio on her clients. Sharon Tate, who prefers the Monkees to the Beatles, is fully aware that she’s playing the role of “sexy little me” in most social encounters. Yet she genuinely enjoys the audience laughter aroused by her klutzy scene in the not-very-good The Wrecking Crew.

Still, the book dwells far more on the men. The Mannix episode on Cliff’s TV spells it out.

These men are anxious. Both Rick Dalton and James Stacy see their futures endangered. Charlie Manson is trying to build a career in the music business, but his clumsy networking reveals him as a loser. Most strikingly, in devoting seven chapters to Cliff Booth’s life story, the narration presents a composite of trends swirling through the period.

We who’ve seen the film know Cliff’s manic, LSD-buzzed defense of Rick’s home. But who is he? This war hero who has murdered his wife and three other people is a hard case with a soft spot for foreign films. He’s a dog lover who put his pit bull Brandy through harrowing fights. He hurls Bruce Lee against a car but, out of concern for George Spahn, worries that the hippies encamped on his ranch are exploiting him. If Rick and James’ niches in the hierarchy are shifting, Cliff knows his place is near the bottom. Living in a crummy trailer eating Kraft Macaroni & Cheese, he can survive thanks to his muscle and his wits. He might be a man of principle who’s just pushed past his breaking point a bit too often.

Enter Aldo Ray, an actual actor whom Tarantino has long celebrated. Despite working with George Cukor, Anthony Mann, Raoul Walsh, and other top directors, Ray destroyed himself through alcohol and wasteful spending. He gets his own chapter near the end, brought into the story when Cliff is stunting on a runaway production in Spain. While Charles Bronson is becoming a star, Aldo is sinking into a numb despair. He is what Rick or Stacy might become.

As the book closes, this parade of masculine misery replaces the film’s Manson Family siege. After finishing the day’s Lancer shoot, Rick and Stacy head out to the Drinker’s Hall of Fame, a tribute to great Hollywood drunks. Cliff and other acquaintances join them, and they share stories of their sex lives and the productions they worked on. Rick finally manages to spell out why he hates the Great Escape rumor. He admits to his peers that he never really had any chance for the McQueen part. That clarity seems to give Rick a dose of prudence: he leaves early because he needs to learn his lines for tomorrow. For the reader, the drinking bout chimes with Aldo Ray’s plight in the prior chapter, and it suggests how Rick will survive the 1970s. His reconciliation with Stacy will lead both to keep their alcoholism under better control.

Rick’s flash of self-discipline is among the many epiphanies that pile up in the final pages. Sharon, sweet-natured throughout, now gets annoyed with Polanski’s whining bossiness and maneuvers him into holding a pool party. Schwarz calls Rick and offers him a chance for a spaghetti western. Rick runs into Steve McQueen, and his resentment of the superstar drains away in a shared memory of male camaraderie, a pool game long ago. Above all, Rick gets a call from Trudi that resets his relation to his past and his craft.

An actor prepares

Tarantino admires directors, but he adores actors. Has any film more fully portrayed the insecurities of performers? Rick sees his career going down the drain while upstarts like Stacy and the coolly competent Trudi Fraser, only eight years old, are more professional than he is. Rick is baffled by the director’s pretentious ambitions (“Be evil sexy Hamlet”) and rages in his trailer when he blows his lines. Each small error confirms Schwarz’s diagnosis that Rick can flourish only in a downmarket cinema, below even episodic TV.

One of the film’s finest sequences builds enormous tension when it shows Rick struggling to keep up with Stacy in their saloon reunion.

Tarantino could have shot this sequence in 4:3 ratio and TV style, in accord with the Bounty Law commercial that opens the movie. But the bar sequence, like the hostage scene to come later, maintains the same stylistic tenor–widescreen, long takes, rich color–that presents the story of Rick, Cliff, and Sharon. Remarkably, we don’t see any shots of the director and crew watching the performance. The production staff remain offscreen, cueing Rick’s lines. Tarantino has fused the modern camera with the TV camera, “rewriting” the TV production with shadowy modern lighting and arcing camera moves. This filming strategy puts the pilot on par with the surrounding story, just as in the book the Lancer family saga carries the same weight as the 1969 story line.

At the same time, the sequence lets us see just how difficult film acting is. (You can see Stacy trying to match his spoon’s movements to get a clean retake.) An awkward axial cut-in to the bartender delivering Johnny’s beans may be hinting that already Rick has blown a line and they had to reshoot it.

Acting is hard. Even bad acting is hard. Could you or I do what Rick has to do in this scene?

Seeing Rick’s malfunctioning performance in this scene puts more pressure on the big hostage scene, which again runs as if it’s part of the surrounding film. But now, after Rick aces the scene, we get our first crew shot and the director’s happy reaction, along with Trudi’s whispered praise.

Even more than the film, the book pays homage to the strain of actors’ working lives. By sequestering the Lancer episodes in separate chapters, Tarantino can focus elsewhere on the sheer terror of preparation for filming them. Now we see why the book stresses the performers’ leadup to each shoot. We’ve seen in the film how harrowing it is to screw up, and the book digs into the panic of preparation.

Which is why, I suggest, the book ends with one more phone call. (The back cover of the paperback hints at its imporance.) Suspecting that Rick is slacking off, Trudi calls Rick to goad him into rehearsing. As they start to run the lines, they slip into their characters. The narration cooperates.

Which is why, I suggest, the book ends with one more phone call. (The back cover of the paperback hints at its imporance.) Suspecting that Rick is slacking off, Trudi calls Rick to goad him into rehearsing. As they start to run the lines, they slip into their characters. The narration cooperates.

Caleb answers flippantly, “Greed’s what makes the world go ’round, little lady.”

The little lady says her name out loud: “Mirabella.”

“What?” Caleb asks.

The eight-year-old child repeats her name to the outlaw leader. “My name is Mirabella. If you’re gonna murder me in cold blood, I don’t want you to just think of me as Murdock Lancer’s little girl.”

Something about the way she says that registers with the outlaw. And suddenly it becomes important for Caleb to make her understand his fairness on this matter.

Through Rick’s performance the narration can plunge into Caleb’s mind. Things get even more complex when Johnny enters the scene, voiced by Trudi.

Trudi as Johnny points out, “Something happens to that money and we don’t get it, that’s our problem.”

Caleb spins toward Johnny and violently says, “Something happens to that money, that’s her problem!” With fire in his eyes, he tells Johnny Lancer, “Git it straight, boy! . . .”

Very soon Caleb will be shot dead, as enacted by Rick over the phone.

As usual, we won’t see the scene filmed, but Trudi foresees the result. “We’re going to kill this scene tomorrow.” Rick agrees. When she adds that they’re in a great line of work, Rick has his biggest epiphany. Trudi is right. The career that seemed so dismal has let him work with great actors, make love to beautiful women, enjoy luxuries most men never dream of.

He looks around at the fabulous house he owns. Paid for by doing what he used to do for free when he was a little boy: pretending to be a cowboy.

Boys will be boys, apparently forever.

Tracing three movie careers–a fading star, an aspiring starlet, and a below-the-line crew member–the film and the book provide Tarantino’s views not just of swinging-60s Hollywood (“You shoulda been there!”) but what working in The Business is like. Like most books and movies set in the film capital, these two texts show the pleasures and pains of a life that’s at once glamorous and dangerous.

But thanks to visual and verbal bravado, ingenious crosstalk between cinema and prose, and a respect for actors, Tarantino has gone beyond the usual finger-wagging chastisement of Hollywood excess. His taste for low-grade product, which has sometimes seemed an auteur provocation, is revealed as a respect for the desperate energy that animates even barely talented performers. That stubborn struggle, he suggests, is more rewarding than hippies’ hopes to mosey into nirvana.

Tarantino’s respect for those who dare to make movies, even opportunistic and down-market ones, puts him squarely in the classical Hollywood tradition of striving professionalism. His protagonist realizes, Capra style, that he has a wonderful life. Weird as it sounds to say it, Tarantino’s multimedia fairy tale might be the squarest story he ever told.

The epigraph comes from Graham Fuller, “Answers First, Questions Later,” in Quentin Tarantino: Interviews, rev. ed., ed. Gerald Peary (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2013), 37.

More homework for the Tarantino squad: Trudi Fraser in the film is Trudi Frazer in the book.

Jeff Smith’s discussions of the film, here and here, were our most popular 2019 entries. They still hold up.

Through a blunder, I missed seeing Mark Minett’s careful email reply to my question about the saloon dialogue scene. Would such an arcing shot be likely in network TV of the period? His response is very helpful:

As for lateral or arcing camera movements during shot reverse shot sequences, I think these must be pretty rare. It’s possible a show might feature one every once and awhile, but these would likely stand out as a directorial flourish. The late 1960s television I’ve seen tends to have static s/rs, with variety achieved through camera height and angle, though I did just see an episode of Hawaii Five-O where the reverse shot was a moving close-up of a pacing Jack Lord.

Typically, you’d get mobile framing as you set up the key figures and then cut into the s/rs sequence. We sort of get that in the LANCER sequence as they sit to eat, and then there’s that interesting jump cut and track back reset as the man approaches with the food (I wonder if this was supposed to signal imperfection and authenticity or what?). Or, you could get a push in on a face at a climax, usually as they move out of the scene or to a commercial, as in the “1958” Bounty Law footage, though I think the more common option was just to hold on a close-up. That arcing move around the back of Olyphant’s head in Lancer, though, would be unusual, I think.

I wonder if it’s worth distinguishing this kind of arcing movement that basically just resets the framing of the scene, from the kind of arcing movements that seem more common now, which continue across cuts and underwrite the dramatic tension of a sequence. The former seems like more of a possible – though still probably very rare – option on the menu of that era’s filmed television, while I’d be really really surprised to find the latter. These are all just somewhat informed hunches, though, and there’s definitely room for real research here. Arcing and lateral movements aside, I’m also not sure when s/rs sequences in filmed TV started to regularly incorporate the slow push-ins that develop over the course of a sequence. So much worth investigating!

Mark should know. He’s the author of an excellent book on Robert Altman’s work, with close study of his TV projects. Another scholar of televisual style, Jonah Horwitz replied as well.

I don’t really have much to add to Mark’s response except nods of agreement. I don’t have the Tarantino movie to hand but the kinds of embellishments David describes would be pretty rare. S/R/S, as Mark notes, tends to be locked down (though not usually as metronomic as on Dragnet!)

A few folks have made some very tentative arguments for directorial style in midcentury US series TV partly on the basis of camera movement—that is, based on ambitious movements being the exception rather than the rule. Some of the former live TV directors I studied tried to import their love of long takes and elaborate camera movements into telefilm production with very mixed success (often they ran into the opposition of producers who wondered why they weren’t getting through x number of setups per day). Some of Joseph H. Lewis’s ’50s TV episodes stand out—in spots—for such things.

Re. Mark’s question, in live TV drama S/R/S is typically handled using long lenses, which made precise or ambitious camera movements somewhat difficult for such sequences. I argue in my dissertation that much of the innovation in S/R/S in live TV drama came from finding ways to get more frontal angles on characters without the camera shooting the reverse-field intruding into the shot. Earlier live drama S/R/S set ups have an obliquity owing to the shooting situation. (If you imagine the prototypical S/R/S staging with a camera placed in front of each character, you can see the problem.) Later directors and cameramen mitigated this through careful planning and extremely dexterous crews. But, again, this is in 50s/early 60s live TV—far from the late 60s telefilm that Tarantino is supposedly pastiching.

I wonder if the partially anachronistic shooting style of the Lancer segment could be motivated by the dream-film aspect of the movie (or maybe given Tarantino’s tendency to flagrant stylization we don’t even need recourse to a more specific alibi).

P. S. 21 July 2021: Tarantino discusses the book in a fascinating interview with Mike Fleming, Jr. at Deadline.

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

What you see is what you guess

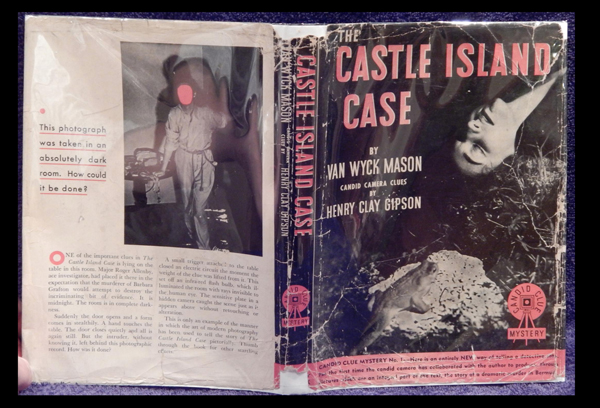

The Castle Island Case (1937).

DB here:

In the 1920s and 1930s, stories of mystery and detection became hugely popular in Anglophone countries. Britain’s “Golden Age” of whodunits, launched by Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, was rivaled by the emergence of American hardboiled detection, personified by Dashiell Hammett and other writers for the pulp Black Mask. Some of the detectives, such as Philo Vance and (alas) Ellery Queen, are largely forgotten today, but others remain towering figures of popular culture. Surprisingly, new Sherlock Holmes stories were still appearing in the 1920s. In addition, there emerged Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Charlie Chan, Sam Spade, Nick and Nora Charles, Nero Wolfe, Philip Marlowe, and Perry Mason (recently revised in a noir version for streaming). Fiction, film, comic strips, and radio all disseminated their adventures. Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys were aimed at the kids.

Amid this vast 0utput, writers needed to differentiate their work. The search for gimmicks was on, and a few were, as we’d say now, a little interactive. Since the classic detective plots centered on puzzles, publishers added games and playful ancillaries to their books.

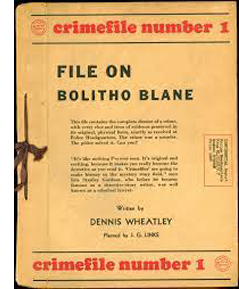

Some novels were published with the last chapters sealed, daring buyers to resist curiosity and return the book for a refund. A novel (The Long Green Gaze, 1925) might tuck clues into crossword puzzles (another 1920s fad) that the reader had to solve. Books came packaged with jigsaw puzzles (The Jig-Saw Puzzle Murder, 1933; Murder of the Only Witness, 1934). “Murder dossiers” like File on Bolitho Blane (aka Murder in Miami, 1936) assembled facsimile documents accompanied by matchsticks, strands of hair, bloodstained scraps of fabric, and other physical clues. The party game of Murder, in which guests were assigned roles of victim, culprit, witnesses, and detectives, became a craze and was, naturally, incorporated into novels (Hide in the Dark, 1929).

Some novels were published with the last chapters sealed, daring buyers to resist curiosity and return the book for a refund. A novel (The Long Green Gaze, 1925) might tuck clues into crossword puzzles (another 1920s fad) that the reader had to solve. Books came packaged with jigsaw puzzles (The Jig-Saw Puzzle Murder, 1933; Murder of the Only Witness, 1934). “Murder dossiers” like File on Bolitho Blane (aka Murder in Miami, 1936) assembled facsimile documents accompanied by matchsticks, strands of hair, bloodstained scraps of fabric, and other physical clues. The party game of Murder, in which guests were assigned roles of victim, culprit, witnesses, and detectives, became a craze and was, naturally, incorporated into novels (Hide in the Dark, 1929).

The most outrageous of these extramural activities was Cain’s Jawbone (1934). The 100-page story purports to be a mystery novel whose whose pages were accidentally printed and bound out of order. There is, the reader is assured, only one correct sequence, although “the narrator’s mind may flit occasionally backwards and forwards in the modern manner.” The publisher offered a prize to the first reader who could submit the correct ordering–and, not incidentally, name both the murderer(s) and the victim(s). Only two people hit on the answer, which still remains unknown to the public.

Even quite well-known writers joined in. The original editions of Sayers’ Five Red Herrings (1931) left a page blank so that the reader could jot down a guess at what Lord Peter asked the police to find at the murder scene. Sayers was quite proud of “this little stunt,” and floated the possibility of printing the missing passage in a sealed page at the end of the book. She also wrote a Lord Peter story that invited the reader to solve a rather recondite crossword. Q. Patrick composed a murder dossier, The File on Claudia Cragge (1938).

Less immersive but still pretty interesting was my topic of today. I think it coaxes us to think about how pictures and text can interact, and how a book can borrow film techniques. In addition, it has enough weird touches to make it a remnant of a period in desperate search of storytelling novelty. You know, like ours.

More highly seasoned than most

With The Castle Island Case (published September 1937) a fairly famous author, Van Wyck Mason, introduced what he considered “a brand-new method of telling a mystery story.” That method involved accompanying the novel with staged photographs of the characters, clues, and crime scenes. Mason insisted that he and photographer Henry Clay Gipson came up with the idea before the first murder dossier (1936) and before Look magazine’s “Photocrime” series, which began running in June of 1937.

Novels had long been illustrated; our undying conception of Holmes owes a good deal to Sidney Paget’s vivid drawings in the original stories. And comic books, which had begun telling long-form stories in the 1930s, showed that pictures (helped out by verbiage) could sustain plots. But photography changes the status of the image. Mason believed that photos could be not “mere illustrations but an essential, integral part” of the novel.

Interestingly, he doesn’t rest his case on realism, the idea that the story would seem more plausible if it contained documentary images. But surely the appearance of a photographic record gives a forensic quality to the shots of clues and corpses. At the period, tabloids and even “family” magazines like Life and Look were incorporating gory crime-scene images.

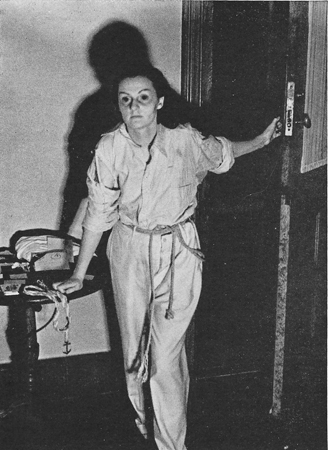

In The Castle Island Case, as befits fiction, these are more artfully composed. The shots of Allenby at an autopsy and of a topless woman washed onto the beach, we’re told, “were a very definite part of the story and were not included merely for effect.”

Still, they are a bit startling in their prim sensationalism. (One reviewer: “A thriller more highly seasoned than most.”) The book’s up-and-coming publisher, Reynald & Hitchcock, had developed a reputation for daring: it published Hitler’s Mein Kampf in a complete translation the same year as Mason’s novel. Later the firm would issue policy books from a liberal standpoint and, in 1944, the controversial Lillian Smith novel Strange Fruit.

For the shoot Reynald & Hitchcock flew the cast to Bermuda, where Mason lived. The story incorporated the exotic scenery and local life, notably a Gombey performance. Mason and Gipson accumulated about 600 stills in ten days, and they checked their results immediately, processing films far into the night. The finished book includes 180 or so shots, printed alongside text on glossy paper and bound in a large 7½ x 10-inch trim size that make them easy to study. An essential hook, trumpeted on the dust jacket, is that you can examine the pictures to find evidence that the text doesn’t mention. This was to be the first in a series of “Candid Clue Mysteries”–crime traces captured by the candid camera.

Picture this

Major Roger Allenby has flown to Bermuda to help an old friend whose daughter Judy has gone missing. She was serving as secretary to millionaire Barnard Grafton. Allenby arrives under the pretext of joining Grafton’s shady business deal with the president of Ecuador. Grafton is hosting other potential investors and several female guests. The set-up is a classic mystery situation: an isolated setting and a small group of wealthy people, some of whom will die or disappear, leaving the others as suspects. Soon Judy’s sister Patricia, who has replaced her on Grafton’s staff, is murdered.

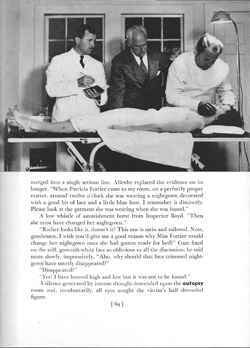

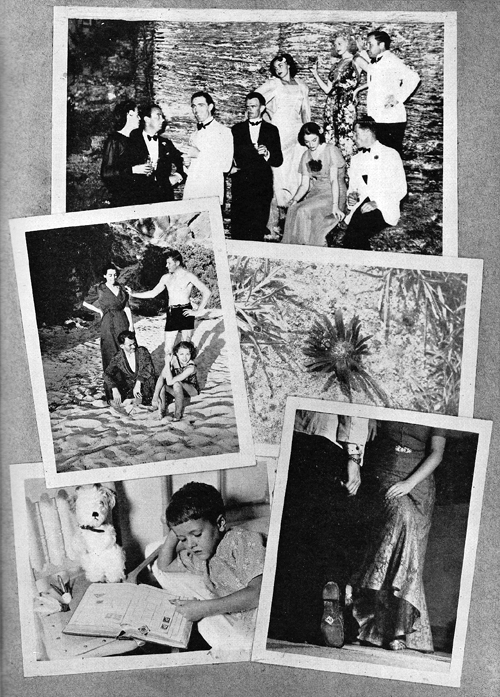

The photos are of three types. One operates as classic illustrations, showing all the characters from an impersonal perspective. So Allenby can be seen among others, as in the rather Straub/Huilletian autopsy image above. A second type of images is more “omniscient” and free-ranging, filling us in on background information.

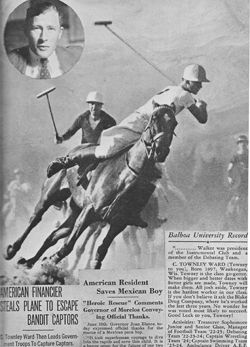

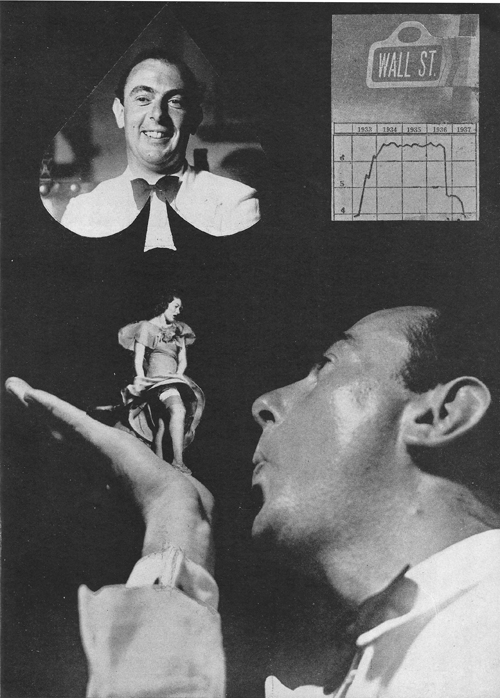

Mason declared that the photos could save time on exposition. Instead of describing the characters and settings, he could just show them. But he didn’t mention that, apart from Allenby, most major characters are introduced in abstract photomontages, not candid snapshots. The first one we see is devoted to wastrel C. Townley Ward. He’s presented in a collage of pictures and news clippings.

The page devoted to Ward could have been replaced with paragraphs of backstory. But the layout coaxes the reader into a process of scrutiny that’s probably more intense than scanning prose. Are there clues in the images or the clippings? This crammed page, coming early in the book, encourages the reader to look carefully at the pictures that follow. This attention wouldn’t necessarily be aroused by traditional drawn or painted illustrations.

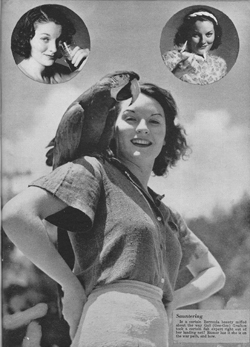

Sometimes, as in the page devoted to jaunty Kathleen Manship, the layout recalls comic-book splash pages.

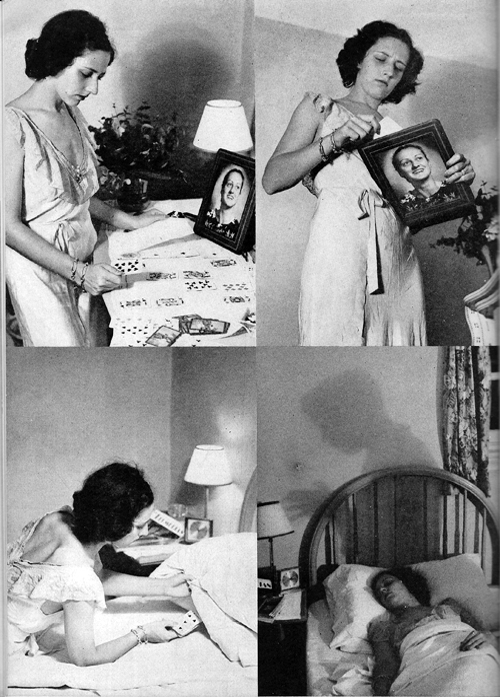

A second sort of photos accords with Allenby’s restricted viewpoint. He has brought his camera along, so some images, like the nude shot on the beach, are represented as his recording of a crime scene.

Naturally Allenby films letters and other obvious clues, and he sets traps to gain evidence. He rigs up an automatic camera device to capture an intruder, but to sustain suspense Mason shows us the negative first, then postpones revealing the person exposed (as above).

Sometimes, though, it’s Allenby’s casual snapshots that accidentally capture items whose significance is apparent later. In all, Mason tries to play fair with the reader. If you page back after the solution is revealed, you can find that indeed the clue was there (however tiny). In good mystery-mongering fashion, however, some pages are red herrings. They contain no clues, but you’re likely to study them anyhow.

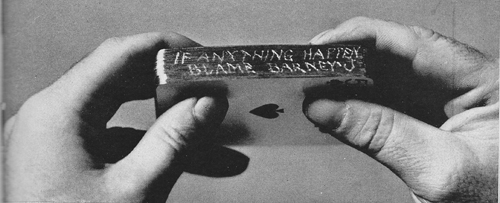

Photography also helps us grasp clues that are more vivid than a prose description could provide. My favorite is the telltale pack of playing cards left behind by Patricia after her death. Trying them out in different sequences, Allenby notices that they contain tiny nicks on their edges. Odd phrases in Judy’s purported suicide note suggest a code the sisters shared, so after cracking that and arranging the cards accordingly, Allenby finds that the nicks yield a message.

I think that the picture makes the discovery livelier than an account in the text would be.

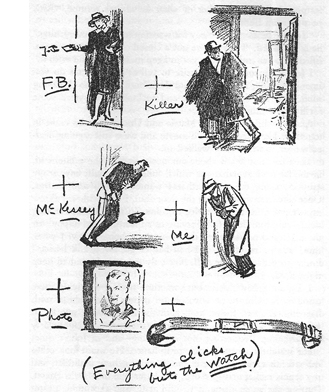

As in many detective stories, the clues are summed up before the detective reveals the solution. Here, Mason gathers up the most relevant photos Allenby has taken, challenging the reader to draw the right conclusions.

Another plot convention: the final assembly of the suspects for a public revelation of guilt. In this book, it’s done through Allenby’s setting a trap. He will take an infrared picture that will, during a crucial moment of darkness, expose the killer. The exercise neatly brings together the objective, omniscient type of photo and Allenby’s eyewitness shots. First we see the entire scene, including Allenby. Then his camera’s record is presented in radically washed-out tones, suggesting a different film stock. (The second frame below is a detail from the climactic two-page spread, to avoid a spoiler.)

Movies on the page

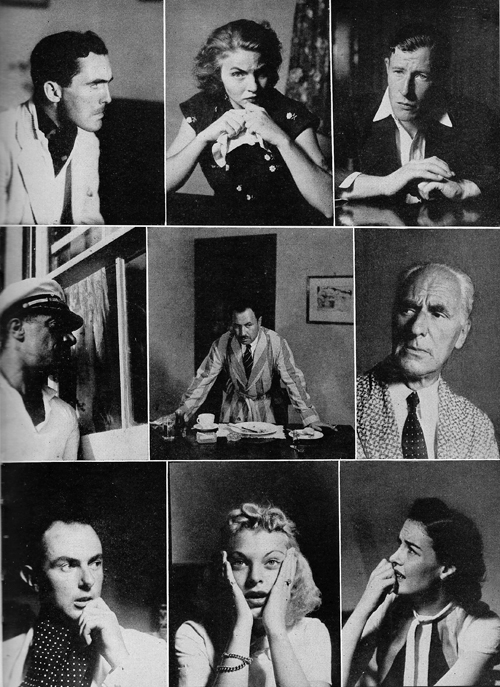

The gimmickry of The Castle Island Case is enlivened by some features that go beyond puzzle and fair play. The book breaks its own rules, sometimes in ways that recall films. For example, we get a cluster of reaction shots of the characters responding to news of Patricia’s death.

The pictorial narration running alongside the text sometimes breaks from our restriction to Allenby’s viewpoint for the sake of a cinematic effect. As he broods on the danger Patricia is in, the book “cuts away” to her in her bedroom. Four images show her sorting the playing cards, slipping the suicide note into a picture frame displaying her sister’s photo, tucking the pack of cards under her pillow, and–ultimate movie touch–sleeping while a clutching shadow hovers over her.

Still later, the book will present a pictorial flashback, complete with angle changes, to show what led to Judy’s disappearance. There’s also a photomontage illustrating Terry James’ freewheeling lifestyle that calls to mind the turbulent montage sequences of Slavko Vorkapich.

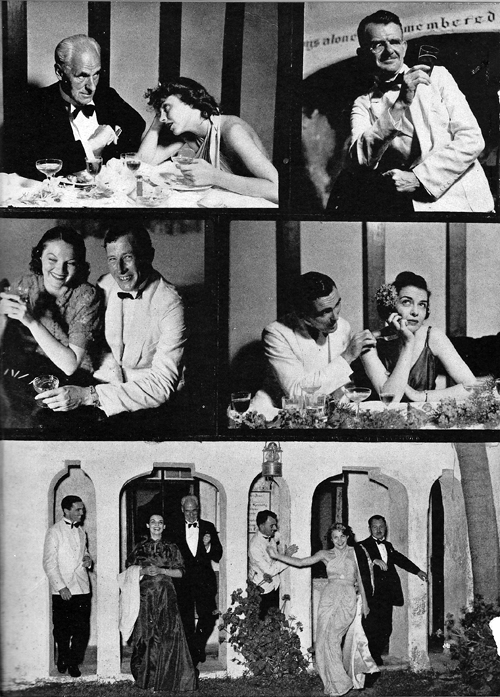

The book’s debt to cinema is perhaps most obvious in its last image, a clinch that traditionally closes a Hollywood movie. (See below.) Far stranger is the sequence devoted to the drinks-and-swims party.

One page presents the guests hanging out, with the bottom one suggesting a party snapshot not taken by Allenby, although he’s in it.

Facing this page is a curious portrait, evidently not taken by Allenby, showing a morose Grafton staring into his drink.

What’s he looking at? Inside the champagne glass is the head of an apparently drowning woman.

Is this a tipoff to the reader that Grafton killed Patricia? At the end we’ll realize what it means, but here it seems to offer a peculiar access to his mind, certainly beyond Allenby’s range of knowledge. In a film, the image might be an abrupt, enigmatic flashback to be explained later. Frozen on the page, and looking so different from the other photos we’ve seen, this hallucination turns into kitsch surrealism.

Nothing ever really goes away. Perhaps the murder dossiers transmogrified during the 1940s into the board game Clue (aka Cluedo). The Wheatley ones were reprinted in the 1980s and apparently caught on for a new generation. The Choose Your Own Adventure children’s books included mysteries that allowed some interactivity, anticipating the branching options of our investigation-driven videogames. And today’s jigsaw puzzle called Alfred Hitchcock is explained:

Alfred Hitchcock isn’t just another jigsaw puzzle – it’s a mystery waiting to be solved. First, read about a psychotic fan who’s obsessed with Hitchcock’s classic films. Next, assemble the puzzle and uncover hidden clues to solve the mystery.

Mason’s “Candid Clue Mystery No. 1” had no successors, but writers didn’t give up on trying to integrate images into mystery plots. Rex Stout tried it, with awkward results, in two Nero Wolfe stories. (One, naturally enough, appeared in Look magazine.) In Murder Draws a Line (1940), Willetta Ann Barber and R. F. Schabelitz divide the labor between a Nick-and-Nora couple. The wife writes the text and the husband, a professional artist, illustrates it with sketches and diagrams of their efforts to solve the crime.

Mason’s “Candid Clue Mystery No. 1” had no successors, but writers didn’t give up on trying to integrate images into mystery plots. Rex Stout tried it, with awkward results, in two Nero Wolfe stories. (One, naturally enough, appeared in Look magazine.) In Murder Draws a Line (1940), Willetta Ann Barber and R. F. Schabelitz divide the labor between a Nick-and-Nora couple. The wife writes the text and the husband, a professional artist, illustrates it with sketches and diagrams of their efforts to solve the crime.

The text-plus-photos books aren’t truly interactive. Nothing we do can adjust the text or create feedback. But they extend the possibilities of a narrative attitude encouraged by the mystery genre.

Classic detective novels and short stories rely on a type of close reading. We’re expected to scrutinize descriptions of locales and behavior for cleverly planted traces of what’s really going on. Agatha Christie has a genius for mentioning items that we read over, thanks to misdirection and the blandness of her prose, but even hardboiled novels bury verbal clues so as to play fair. A slip of the tongue that we probably miss leads Sam Spade to Bridgid O’Shaughnessy’s guilt.

Knowing that authors aim to mislead us through language, we read with a greater degree of suspicion than we bring to other genres. By extending this attitude to images as well as words, gimmicks like The Castle Island Case encourage us to consider how the pictures may tell the story, or sabotage our understanding of it. That’s what movies have done as well. We shouldn’t be surprised that these oddball efforts call on familiar storytelling schemas of classical cinema.

Chapter 17 of Martin Edwards’ splendid The Life of Crime: Unravelling the History of Fiction’s Favorite Genre, reviews many more of these Golden Age games. It’s due out from Collins in May of next year, but in the meantime visit Martin’s bountiful website and proceed to sample any of his vast output of novels, anthologies, and histories of detective fiction.

For background on Cain’s Jawbone, go to this account in The Guardian. It was reissued in 2019, as both a book and a set of cards (now very scarce). The publisher, appropriately called Unbound, offered a prize of £1000 for the first solution. The prize was won by a comedy writer who cracked the puzzle while housebound during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dorothy Sayers’ remark on her Five Red Herrings ploy comes from Janet Hitchman, Such a Strange Lady: A Biography of Dorothy L. Sayers (New York: Avon, 1976), 88-89. The Sayers story using a (very tough) crossword puzzle is “The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager’s Will” (1925).

My quotations from Van Wyck Mason come from “The Camera as a Literary Element,” The Writer 51, 11 (November 1938), 325-326. The review I quoted, unsigned, appeared in “The Criminal Record,” The Saturday Review (9 October 1957), 28.

The Rex Stout Nero Wolfe stories inserting photographs are Where There’s a Will (1940) and “Easter Parade” (1957), reprinted in And Four to Go (1958). I don’t talk about them here.

Thanks to Peter McDonald for introducing me to Virginia, The Shivah, Blackwell Unbound, and other mystery-driven videogames.

P.S. 25 June 2021: Alert reader and old friend Jonathan Kuntz reminded me of other interactive mystery platforms, including the Secret Cinema screenings. He also mentions non-mystery boardgames that let you replay films, as in The Thing and The Lord of the Rings.

P.P.S. 28 June: Alert reader and mystery maestro Mike Grost traces a chain of association to the champagne-glass image. Van Wyck Mason published a story called “The Enemy’s Goal” in Argosy (18 May, 1935). That story was adapted by Joseph H. Lewis for a film, The Spy Ring, released in 1938, and there a character summons up a mental image in a champagne glass. I haven’t seen the film, but Mike suggests that such subjective shots are fairly rare in Lewis films. He thanks Francis M. Nevins for finding the link, and I thank both.

The Castle Island Case (detail).