Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Coming attractions, plus a retrospect

Invasion of the Brainiacs

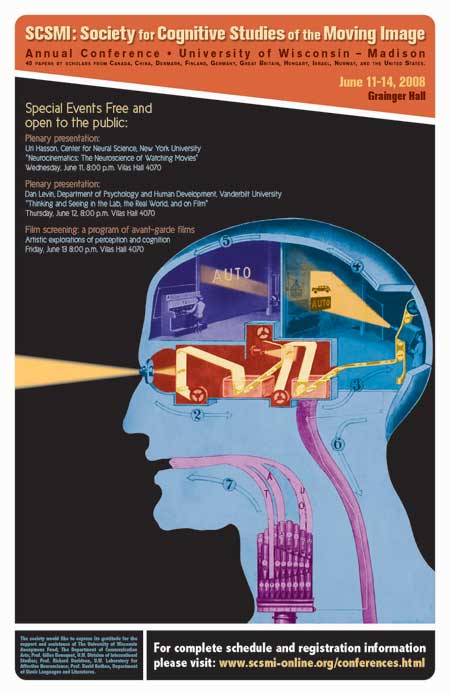

First, the event that will occupy us through next week: the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, a group founded in 1997. This year’s gathering brings researchers from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Turkey, Canada, China, and the Nordic countries, as well as many from the U. S. The meeting is here in Madison, from 11 to 14 June.

In over forty sessions, researchers will be talking about how we respond to movies, TV shows, and videogames. How has digital imagery changed our experience of cinema? How does film music enhance our emotional response to the story? How do films guide our visual attention to one part of the screen, and how much do viewers differ in this? How do we respond when movie characters behave inconsistently?

I’ve already blogged and bragged about our event here, but now I want to highlight four attractions. If you’re in or near Madison, you might want to stop by; and in any case, you might want to check the links mentioned below.

For some years Professor Uri Hasson of New York University’s Center for Neural Science has studied how the human brain responds during film viewing. Using fMRI techniques, he has discovered that Hollywood films, such as those by Hitchcock, have created remarkably similar responses across a variety of viewers. Art films, he says, may require just as much concentration, but they will elicit less convergent reactions. He’ll present the fruits of his research on June 11. You can learn more about Uri’s research here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

NB: 12 June 2008: In fact, the gorilla-suit experiment was conducted by Dan Simons, not Dan Levin. The last link takes you to Simons’ article. Both Dans work in the area of attention and “change blindness,” and they have collaborated on several projects. I apologize for the error.

There is a registration fee for the conference’s day events, but these evening lectures are free and open to the public. Each begins at 8:00 PM and will be held in 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue.

The final night of the conference is devoted to a screening of experimental and avant-garde films that provoke questions about how we respond to cinema. There will be a discussion of them afterward, which will include two of the filmmakers, Joseph Anderson and J. J. Murphy. This screening, open to the public, starts at 8:00 PM in 4070 Vilas.

During the conference, one event is devoted to a discussion of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. This book is a remarkable effort to mount a systematic philosophy of film, TV, and related media. It’s full of provocative claims (e.g., that cinematic movement isn’t an illusion) and nifty examples. Noël is a polymath, with two Ph. D.s and more books and articles than anybody, including he, can count. Four other scholars will criticize some aspect of the book’s arguments, and Noël will respond. (One of those critics, Lester Hunt, is a philosophy prof here who maintains a wide-ranging website and a blog that often touches on film.) There should be some fireworks.

There are other brainiacs coming, many of them pioneers in this area: Joe and Barb Anderson, Murray Smith, Torben Grodal, Patrick Colm Hogan, Carl Plantinga, Paisley Livingston, Sheena Rogers, Dan Barratt, and Tim Smith (aka Continuity Boy), and too many others to include here. In all, I’m proud of what our local team, with the energetic Jeff Smith as point man, has accomplished in setting up this jamboree.

As regular readers know, I think that cognitive research into cinema holds great promise. It brings together a group of scholars from different disciplines who want to understand, in an empirical way, how movies work. The field is very young, and it’s not the only way to go; but it has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media, and maybe our understanding of the mind too.

Up to now SCSMI has been quite an informal group, but now we have a more systematic organization. We have officers, bylaws, and a sense that our research is coalescing around key ideas, about which there is lively and congenial disagreement. And, because there are more people who want to get involved, we’ll start meeting every year. The 2009 gathering is slated for Copenhagen.

I hope to dash off a blog entry in medias res. We’ll also do our best to introduce our colleagues from overseas and from the Coasts to the glories of brats, cheese, beer, and of course The House on the Rock.

By the way, you might want to check on this cognitive scientist, who claims that every one of us can see into the future (but only a little bit).

Kristin and the Comic-Book Guys (100,000 or so)

Speaking of gatherings of like-minded individuals, TheOneRing.net people have invited Kristin to take part in their panel on the upcoming Hobbit project at Comic-Con in San Diego, on Friday, July 25 at 10 am. She hopes to blog from among the multitudes.

A new website and a nervous DVD

There’s a new and attractive website up and running. Sponsored by the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, NYC, Moving Image Source is a vast project packed with links, research data, and essays about films both classic and contemporary. The first posse of writers includes Michael Atkinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Sikov, Melissa Anderson, and other luminaries. The topics range from Andy Warhol and Howard Hawks to Werner Herzog (an interview). Steered by Dennis Lim, this is bound to be an essential watering hole for everybody interested in film history and criticism.

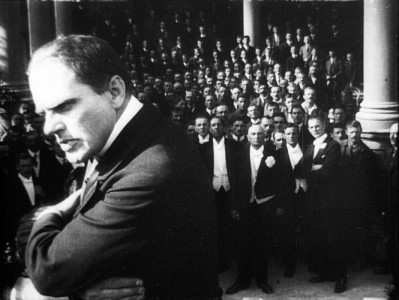

Speaking of film history, an important film is coming to DVD. Robert Reinert’s 1919 Nerven, which I wrote about in Poetics of Cinema, has been restored by Stefan Drössler and his crew at the Munich Filmmuseum. This is one of the strangest movies of the silent era. The plot, as Chris Horak points out in his accompanying essay, is steeped in Spenglerian melancholy, reminding us that Expressionism could be politically conservative as well as revolutionary. The visuals are at once monumental and unstable, like boulders teetering over a precipice. I try to analyze them in another contribution to the DVD booklet. Drössler has contributed an essay on the process of restoration.

Nerven was a box-office fiasco and never achieved the fame of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a way, it is more disturbing than that official classic because Reinert’s alternation of frenzy and somnambulism takes place in a more or less solid world, like ours. Frantic scenes of street fighting mix with brooding images of a bourgeoisie sliding into religious possession or straight-up lunacy. It is not every day that you see a movie that begins with a man throttling his wife and then lovingly refilling their parakeet’s water cup. If you’re a fan of wild deep-space imagery way before Citizen Kane (as above), this one’s for you. And yes, it will have English subtitles.

Nerven will be available later this summer from the Filmmuseum’s shop. It joins an abundance of other fine DVD titles, such as Borzage’s The River and a collection of Walter Ruttmann’s works.

Retrospect: In Europe they do things differently?

Because we see a very thin slice of foreign-language cinema, audiences underestimate the extent to which European films often imitate Hollywood. Surely the cultures of the great continent would never stoop to the crassness of our movies? A trip to any multiplex in Paris or Berlin would probably disabuse people of this notion. The current instance is the reigning French hit Bienvenue chez les ch’tis (Welcome to the Sticks), apparently a fish-out-of-water tale that would induce groans from our intelligentsia.

Kristin has already written about this phenomenon here. I found some supporting evidence last week while scrabbling through an old folder for our Film History revision. It was a 2002 pamphlet from the Filmboard of Berlin Brandenburgh GmbH, a publicly limited company coordinating German state funding. The text laid out a set of guidelines, in English, for productions that the Filmboard would support. After explaining that the judges must consider financial return as well as cultural factors, the guidelines insist that the quality of the screenplay is of paramount importance. What makes a good screenplay?

The success of a film decisively depends upon whether the audience can engage enthusiastically with the actors on the screen. An audience looks for strong central characters whose fates it can identify with. The hero or heroine should have goals and needs and should have an emotional effect on an audience. Further dramaturgical criteria:

There must be a concrete goal, which at the end of the story is either reached—or not.

There should be a risk involved for the central character in not reaching his/her goal.

The goal is perhaps difficult to reach, and the struggle to do so should bring the central character into conflict. The audience sympathizes with the story when, for example, the hero or heroine follows the wrong goal, makes mistakes, or experiences a crisis.

This sounds easy to understand. But writing screenplays is more complex.

*The central character should have subconscious needs. He/ she should lack an important human quality and only gradually experience this for him/herself.

*At the end of the story the central character should come to know his/her unconscious needs and gain a satisfactory recognition about him/herself and life in general, which can be formulated in the emotional subject matter of the film.

*The central character should undergo a process of development, as characters that do not develop are boring. Moments of decision in stories are the key for good character development.

The passage lays out a lot of what U. S. screenplay manuals have been asserting for decades (notions that Kristin and I have analyzed in various books). This is still more evidence that the Hollywood model, with its goal-oriented chain of causes and effects and its protagonist who improves through a “character arc,” holds sway far beyond our own shores. Whether it should be so widespread is another question, but for Kristin and me, this template or formula is a bit like the sonnet or the well-made play: a form that can yield results good, bad, and indifferent. The point is to take the form seriously enough to understand what makes it work.

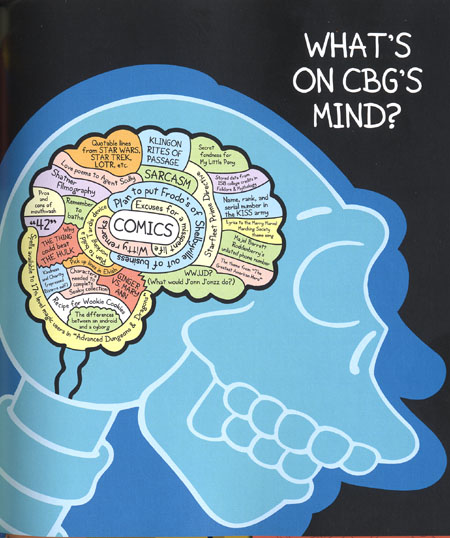

From Comic Book Guy’s Book of Pop Culture (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), n.p.

In critical condition

DB here:

A Web-prowling cinephile couldn’t escape all the talk about the decline of film criticism. First, several daily and weekly reviewers left their print publications, as Anne Thompson points out. Then one of our brightest critics, Matt Zoller Seitz, suspended writing in order to return to film production. This and the departure of another web critic, Raymond Young of Flickhead, has prompted Tim Lucas to ponder, at length and in depth, why one would maintain a film blog. Go to Moviezzz for a summing up.

I’ve been teaching film history and aesthetics since the early 1970s, but before that I wrote criticism for my college newspaper, the Albany Student Press, and then for Film Comment. When I set out for graduate school, film criticism was virtually the only sort of film writing I thought existed. Auteurism was my faith, and Andrew Sarris its true apostle (for reasons explained in an essay in Poetics of Cinema). In grad school, I learned that there were other ways of thinking about cinema. Since then, I’ve tried to steer a course among film criticism, film history, and film theory—sometimes doing one, sometimes mixing them. But criticism has remained central to my interest in cinema.

What, though, does the concept mean? I think that some of the current discussions about the souring state of movie criticism would benefit from some thoughts about what criticism is and does.

Watch your language

Consider criticism as a language-based activity. What do critics do with their words and sentences? Long ago, the philosopher Monroe Beardsley laid out four activities that constitute criticism in any art form, and his distinctions still seem accurate to me. (1) We use them in Chapter 2 of Film Art.

*Critics describe artworks. Film critics summarize plots, describe scenes, characterize performances or music or visual style. These descriptions are seldom simply neutral summaries. They’re usually perspective-driven, aiding a larger point that the critic wants to make. A description can be coldly objective or warmly partisan.

*Critics analyze artworks. For Beardsley, this means showing how parts go together to make up wholes. If you simply listed all the shots of a scene in order, that would be a description. But if you go on to show the functions that each shot performs, in relation to the others or some broader effect, you’re doing analysis. Analysis need not concentrate only on visual style. You can analyze plot construction. You can analyze an actor’s performance; how does she express an arc of emotion across a scene? You can analyze the film’s score; how do motifs recur when certain characters appear? Because films have so many different kinds of “parts,” you can analyze patterns at many levels.

*Critics interpret artworks. This activity involves making claims about the abstract or general meanings of a film. The word “interpret” is used in lots of ways, but in the sense meant here, figuring out the chronological order of scenes in Pulp Fiction wouldn’t count. If, though, you claim that Pulp Fiction is about redemption, both failed (Vincent) and successful (Jules’ decision to quit the hitman trade), you’re launching an interpretation. If I say that Cloverfield is a symbolic replay of 9/11, that counts as an interpretation too.

*Critics evaluate artworks. This seems pretty straightforward. If you declare that There Will Be Blood is a good film, you’re evaluating it. For many critics, evaluation is the core critical activity; after all, the word critic in its Greek origins means judge. Like all the other activities, however, evaluation turns out to be more complicated than it looks.

Why break the process of criticism into these activities? I think they help us clarify what we’re doing at any moment. They also offer a rough way to understand the critical formats that we usually encounter.

In paper media, on TV, or on the internet, we can distinguish three main platforms for critical discussion. A review is a brief characterization of the film, aimed at a broad audience who hasn’t seen the film. Reviews come out at fixed intervals—daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly. They track current releases, and so have a sort of news value. For this reason, they’re a type of journalism.

An academic article or book of criticism offers in-depth research into one or more films, and it presupposes that the reader has seen the film (or doesn’t mind spoilers). It isn’t tied to any fixed rhythm of publication.

A critical essay falls in between these types. It’s longer than a review, but it’s usually more opinionated and personal than an academic article. It’s often a “think piece,” drawing back from the daily rhythm of reviewing to suggest more general conclusions about a career or trend. Some examples are Pauline Kael’s “On the Future of Movies” and Philip Lopate’s “The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies.” (2) Critical essays can be found in highbrow magazines like The New Yorker and Artforum, in literary quarterlies, and in film journals like Film Comment, CinemaScope, and Cahiers du Cinéma.

Any critic can write on all three platforms. Roger Ebert is known chiefly for his reviews, but his Great Movies books consist of essays. (3) J. Hoberman usually writes reviews, but he has also published essays and academic books. And the lines between these formats aren’t absolutely rigid, as I’ll try to show later.

Reviewing reviewers

How do these forums relate to the different critical activities? It seems clear that academic criticism, the sort published in research articles or books, emphasizes description, analysis, and interpretation. Evaluation isn’t absent, but it takes a back seat. Usually the academic critic is concerned to answer a question about the films. How, for instance, is the theme of gender identity represented in Rebecca, and what ambiguities and contradictions arise from that process? In order to pursue this question, the critic needn’t declare Rebecca a great film or a failure.

Of course, the academic piece could also make a value judgment, either at the outset (I think Rebecca is excellent and want to scrutinize it) or at the end (I’m forced to conclude that Rebecca is a narrow, oppressive film). But I don’t have to pass judgment. I have written about a lot of ordinary films in my life. They became interesting because of the questions I brought to them, not because they had a lot going for them intrinsically.

The academic article has a lot of space to examine its question—several thousand words, usually—and of course a book offers still more real estate. By contrast, a review is pinched by its format. It must be brief, often a couple of hundred words. Unlike the academic critique, the review’s purpose is usually to act as a recommendation or warning. Most readers seek out reviews to get a sense of whether a movie is worth seeing or even whether they would like it.

Because evaluation is central to their task, reviewers tend to focus their descriptions on certain aspects of the film. A reviewer is expected to describe the plot situation, but without giving away too much—major twists in the action, and of course the ending. The writer also typically describes the performances, perhaps also the look and feel of the film, and chiefly its tone or tenor. Descriptions of shots, cutting patterns, music, and the like are usually neglected. And what is described will often be colored by the critic’s evaluation. You can, for instance, retell the plot in a way that makes your opinion of the film’s value pretty clear.

Reviews seldom indulge in analysis, which typically consumes a lot of space and might give away too much. Nor do reviewers usually float interpretations, but when they do, the most common tactic is reflectionism. A current film is read in relation to the mood of the moment, a current political controversy, or a broader Zeitgeist. A cynic might say that this is a handy way to make a film seem important and relevant, while offering a ready-made way to fill a column. Reviewers don’t have a monopoly on reflectionism, though. It’s present in the essayistic think-piece and in academic criticism too. (4)

The centrality of evaluation, then, dictates certain conventions of film reviewing. Those conventions obviously work well enough. But we can learn things about cinema through wide-ranging descriptions and detailed analyses and interpretations, as well. We just ought to recognize that we’re unlikely to get them in the review format.

The good, the bad, and the tasty

Let’s look at evaluation a little more closely. If I say that I think that Les Demoiselles de Rochefort is a good film, I might just be saying that I like it. But not necessarily. I can like films I don’t think are particularly good. I enjoy mid-level Hong Kong movies because I can see their ties to local history and film history, because I take delight in certain actors, because I try to spot familiar locations. But I wouldn’t argue that because I like them, they’re good. We all have guilty pleasures—a label that was coined exactly to designate films which give us enjoyment, even if by any wide criteria they aren’t especially good.

They needn’t be disastrously bad, of course. I do like Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, inordinately. It’s my favorite Demy film and a film I will watch any time, anywhere. It always lifts my spirits. I would take it to a desert island. But I’m also aware that it has its problems. It is very simple and schematic and predictable, and it probably tries too hard to be both naive and knowing. Artistically, it’s not as perfect as Play Time or as daring as Citizen Kane or as….well, you go on. It’s just that somehow, this movie speaks to me.

The point is that evaluation encompasses both judgment and taste. Taste is what gives you a buzz. There’s no accounting for it, we’re told, and a person’s tastes can be wholly unsystematic and logically inconsistent. Among my favorite movies are The Hunt for Red October, How Green Was My Valley, Choose Me, Back to the Future, Song of the South, Passing Fancy, Advise and Consent, Zorns Lemma, and Sanshiro Sugata. I’ll also watch June Allyson, Sandra Bullock, Henry Fonda, and Chishu Ryu in almost anything. I’m hard-pressed to find a logical principle here.

Taste is distinctive, part of what makes you you, but you also share some tastes with others. We teachers often say we’re trying to educate students’ tastes. True, but we should admit that we’re trying to broaden their tastes, not necessarily replace them with better ones. Elsewhere on this site I argue that tastes formed in adolescence are, fortunately, almost impossible to erase. But we shouldn’t keep our tastes locked down. The more different kinds of things we can like, the better life becomes.

The difference between taste and judgment emerges in this way: You can recognize that some films are good even if you don’t like them. You can declare Birth of a Nation or Citizen Kane or Persona an excellent film without finding it to your liking.

Why? Most people recognize some general criteria of excellence, such as originality, or thematic significance, or subtlety, or technical skill, or formal complexity, or intensity of emotional effect. There are also moral and social criteria, as when we find films full of stereotypes objectionable. All of these criteria and others can help us pick out films worthy of admiration. These aren’t fully “objective” standards, but they are intersubjective—lots of people with widely varying tastes accept them.

So critics not only have tastes; they judge. The term judgment aims to capture the comparatively impersonal quality of this sort of evaluation. A judge’s verdict is supposed to answer to principles going beyond his or her own preferences. Judges at a gymnastic contest provide scores on the basis of their expertise and in recognition of technical criteria, and we expect them to back their judgment with detailed reasons.

One more twist and I’m done with distinctions. At a higher level, your tastes may make you weigh certain criteria more heavily than others. If you most enjoy movies that wrestle with philosophical problems, you may favor the thematic-significance criterion. So you’ll love Bergman and think he’s a great director. In other words, you can have tastes in films that you also consider excellent. Presumably this is what we teachers are trying to cultivate as well: to teach people, as Plato urged, to love the good.

Of course we can disagree about relevant criteria, particularly about what criteria to apply to a particular movie. I’d argue that profundity of theme isn’t a very plausible criterion for judging Cloverfield; but formal originality, technical skill, and intensity of emotional appeal are plausible criteria to apply. Many of the best Hong Kong films don’t apply rank high on subtlety of theme or character psychology, but they do well on technical originality and intensity of visceral and emotional response. You may disagree, but now we’re arguing not about tastes but about what criteria are appropriate to a given film. To get anywhere, our conversation will appeal to both intersubjective standards and discernible things going on in the movie–not to whether you got a buzz from it and I didn’t.

There’s a reason they call that DVD series Criterion

Now back to film reviewing. Judgment certainly comes into play in a film review, because the critic may invoke criteria in evaluating a movie. Such criteria are widely accepted as picking out “good-making” features. For instance:

The plot makes no sense. Criterion: Narrative coherence helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

The acting is over the top. Criterion: Moderate performance helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

The action scenes are cut so fast that you can’t tell what’s going on. Criterion: Intelligibility of presentation helps make a film, or at least a film of this sort, good.

Most reviewers, though, can’t resist exposing their tastes as well as their judgments. This is a convention of reviewing, at least in the most high-profile venues. Readers return to reviewers with strongly expressed tastes. Some readers want to have their own tastes reinforced. If you think Hollywood pumps out shoddy product, Joe Queenan will articulate that view with a gonzo relish that gives you pleasure. Other readers want to have their tastes educated, so they seek out a strong personality with clear-cut tastes to guide them. Still other readers want to have their tastes tested, so they read critics whose tastes vary widely from theirs. I’m told that many people read Armond White for this reason. Tastes come in all flavors.

Celebrity critics—the reviewers who attract attention and controversy—are usually vigorous writers who have pushed their tastes to the forefront. Top critics like Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael are famous partly because they flaunted their tastes and championed films that they liked. (Of course they also thought that the films were good, according to widely held criteria.) It isn’t only a matter of praise, either. Every so often critics launch all-out attacks on films, directors, or other critics, and some are permanently cranky. Movie reviewer Jay Sherman (above) ranks films by analogy to diseases. Hatchet jobs assure a critic notoriety, but they also prove Valéry’s maxim that “Taste is made of a thousand distastes.”

At a certain point, celebrity critics may even give up justifying their evaluations altogether, simply asserting their preferences. They trust that their track record, their brand name, and their forceful rhetoric will continue to engage their readers. It seems to me that after decades of stressing the individuality of their tastes, many of the most influential reviewers are emitting two main messages: You see it or you don’t and Differ if you dare. I’d like to see more argument and less strutting. But then, that’s my taste.

Stuck in the middle, with us

There’s much more to say about the distinctions I’ve floated. They are rough and need refining. But they’ll do for my purpose today, which is to indicate that everything I’ve said can apply to Web writing.

For instance, it seems likely that one cause of critical burnout is that reviews dominate the Net. They’re typically highly evaluative, mixing taste and judgment. Many people will find a bombardment of such items eventually too much to take. I could imagine somebody abandoning Net criticism simply because of the cacophony of shrieking one-liners. We’re all interested in somebody else’s opinions, but we can’t be interested in everybody else’s opinions.

In addition, the distinguishing feature among these thousands of reviews won’t necessarily be wit or profundity or expertise, but style. I think that, years ago, the urge toward self-conscious critical style arose from the drudgery of daily reviewing. Faced with a dreadful new movie, you could make your task interesting only by finding a fresh way to slam it. In addition, magazines that wanted to appear smart encouraged writers to elevate attitude above ideas. In the overabundance of critical talk on the Net, saying “It’s great” or “It stinks” in a clever way will draw more attention than plainer speaking, but even that novelty will wear off eventually.

Fortunately, there are other formats available to cybercriticism. At first glance, the Web seems to favor the snack size, the 150-word sally that’s all about taste and attitude. In fact, the Net is just as hospitable to the long piece. There are in principle no space limitations, so one can launch arguments at length. (It’s too long to read scrolling down? Print it out. Maybe you have to do that with this essay.) Thanks to the indefinitely large acreage available, one of the heartening developments of Web criticism is the growth of the mid-range format I’ve mentioned: the critical essay.

Historically, that form has always been closer to the review than to the academic piece. It relies more on evaluation. That’s centrally true of the Kael and Lopate essays I mentioned above, both of which warn about disastrous changes in Hollywood moviemaking. But the tone can be positive too, most often seen in the appreciative essay, which celebrates the accomplishment of a film or filmmaker. Dwight Macdonald’s admiring piece on 8 ½ and Susan Sontag’s 1968 essay on Godard, despite their differences, seem to me milestones in this genre. (5)

The critical essay is, I think, the real showcase for a critic’s abilities. We say that good critics have to be good writers, usually meaning that their style must be engaging, but it doesn’t have to explode at the end of every paragraph. More generally, in a long essay, you are forced to use language differently than in a snippet. You need to build and delay expectations, find new ways to repeat and modify your case, and seek out synonyms.

Just as important, the long piece separates the sheep from the goats because it shows a critic’s ability to sustain a case. The short form lets you pirouette, but the extended essay—unless it’s simply a rant—obliges you to show all your stuff. In the long form, your ideas need to have heft. Stepping outside film for a moment, consider Gary Giddins on Jack Benny, or Geoffrey O’Brien on Burt Bacharach, or Robert Hughes on Goya, and in each you will see a sprightly, probing, deeply informed mind develop an argument in surprising ways. (6) Strikingly, all these writers venture into subtleties of analysis and interpretation, putting them close to the academic model. So who needs footnotes?

Above all, the critical essay can develop new depth on the Web. Given more space, the Web can ask critics to lay out their assumptions and evidence more fully. After years of “writing short,” of firing off invectives, put-downs, and passing paeans to great filmmakers unknown to most readers, critics now have an opportunity—not to rant at greater length but to go deeper. If you think a movie is interesting or important, please show us. Don’t simply assert your opinion with lots of hand-waving, but back it up with some analysis or interpretation. The Web allows analysis and interpretation, which take a lot of effort, to come into their own.

Need an example? Jim Emerson, time and again. There are plenty of other instances hosted by journals like Rouge and the extraordinary Senses of Cinema, and many solo efforts, such as a recent one from Benjamin Wright.

Some will object that this is a pretty unprofitable undertaking. Who’ll pay people to write in-depth critical studies on the movies they find compelling? Well, who’s paying for all those 100-word zingers? And who has paid those programmers who continue to help Linus Torvalds develop Linux? People do all kinds of things for love of the doing and for the benefit of strangers. Besides, no one should expect that writing Web criticism will pay the bills. If Disney can’t collect from people who have downloaded Pirates of the Caribbean 3 for free, why should you or I expect to be paid for talking about it? Maybe only idlers, hobbyists, obsessives, and retirees (count me among all four) have the leisure to write long for the Web.

I envision another way to be in the middle. If most critical essays have been akin to reviews, what about essays that lie closer to the other extreme, the academic one? I’d like to see more of what might be called “research essays.” If the critical essay of haut journalism tips toward reviewing while being more argument-driven, the research essay leans toward academic writing, while not shrinking from judgment, and even parading tastes. I’ve tried my hand at several research essays, in books as well as in pieces you’ll find on the left side of this page; and occasionally one of our blog entries moves in this direction.

This isn’t to discourage people from jotting down ideas about movies and triggering a conversation with readers. The review, professional or amateur, shouldn’t go extinct. But we also benefit from ambitious critical essays, pieces that illuminate movies through analysis and interpretation. Web critics could write less often, but longer. In an era of slow food, let’s try slow film blogging. It might encourage slow reading.

(1) Monroe K. Beardsley, Aesthetics: Problem in the Philosophy of Art Criticism (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1958), 75-78.

(2) Pauline Kael, “On the Future of Movies,” in Reeling (New York: Warner Books, 1977), 415-444; Philip Lopate, “The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies,” in Totally Tenderly Tragically: Essays and Criticism from a Lifelong Love Affair with the Movies (New York: Anchor, 1998), 259-279.

(3) In addition, Ebert often manages to build his daily pieces around a general idea, not necessarily involving cinema, so he can be read with enjoyment by people not particularly interested in film. I talk about this a little in my introduction to his collection Awake in the Dark.

(4) Reflectionist interpretation usually seems to me unpersuasive, for reasons I’ve discussed in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32. I realize that I’m tilting at windmills. Reflectionism will be with us forever.

(5) Dwight Macdonald, “8 ½: Fellini’s Obvious Masterpiece,” in On Movies (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 15-31; Susan Sontag, “Godard,” in Styles of Radical Will (New York: Delta, 1969), 147-189.

(6) Gary Giddins, “’This Guy Wouldn’t Give You the Parsley off His Fish,’” in Faces in the Crowd: Musicians, Writers, Actors, and Filmmakers (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 3-13; Geoffrey O’Brien, “The Return of Burt Bacharach,” in Sonata for Jukebox: Pop Music, Memory, and the Imagined Life (New York: Counterpoint, 2004), 5-28; and Robert Hughes, “Goya,” in Nothing If Not Critical: Selected Essays on Art and Artists (New York: Penguin, 1992), 50-64. I pay tribute to Giddins as a critic elsewhere on this site. Hughes later wrote a fine monograph on Goya.

The show goes on

DB here:

Kristin and I had hoped to blog directly from this year’s edition of Ebertfest (formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked and Forgotten Films), but our blogging software failed us. We could post text but no pictures, and where’s the fun in that? Fortunately, the event was widely covered. The schedule, with very full film notes, is here. You can get a sense of what was happening by checking Jim Emerson at scanners and Peter Sobczynski at Hollywood Bitchslap and Kim Voynar at Cinematical and Lisa Rosman at A Broad View and P. L Kerpius at Scarlett Cinema and Andrew Wells at A Penny in the Well and many others. There is some coverage at the News Gazette, although the most informative stories from the paper aren’t on the net. Then there’s Roger’s own blog, Ebertfest in Exile, which in one entry goes off on an unexpected trajectory….toward Joe vs. the Volcano.

Now that we can again illustrate our entry, we offer you an ex post facto blog, like last year’s, which makes up in bulk for its tardiness. I hope to follow soon with a picture gallery.

This year’s Ebertfest lacked an essential ingredient: Roger Ebert. But Chaz Ebert took over hosting duties superbly, aided by the terrific organizational skills of Nate Kohn and Mary Susan Britt. At every screening, one person or another paid tribute to Roger’s gifts to film culture—his writing, of course, but also his tireless championing of deserving movies that should be brought to wider audiences.

The format of Ebertfest offers something for everyone. Traditionally, the opening night is an older film screened in classic 70mm, a format that’s almost vanished. Past years have included shows of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, and My Fair Lady. 70mm looks gorgeous on the vast screen of the Virginia Theatre. This year the film was Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, at four hours the most complete version of the play ever put on film. It looked grand.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Yet another Ebertfest mainstay is a children’s show on Saturday morning, and last year’s wonderful Holes was followed by an unexpected pick—Ang Lee’s Hulk, with the director in attendance. The place was packed, Lee was his charming self, a trio serenaded him, and the audience left well-pleased.

Prime spots are reserved for less-known films, with an emphasis on independent and personal cinema. We saw Tom DiCillo’s Delirious, Sally Potter’s Yes, Joe Greco’s Canvas, and Jeff Nichols’ Shotgun Stories. A highlight for me was Eran Kolirin’s The Band’s Visit, which I’d missed elsewhere. This unassuming, warm, funny movie recalled Tati and 1960s Czech films like Intimate Lighting. Then there was The Cell by Tarsim Singh at a late-night screening, with John Turturro’s Romance and Cigarettes to wrap things up on Sunday. For kaleidoscopic commentary on all these, see the above-mentioned weblogs.

Princely contradictions

I hadn’t seen Hamlet in 70mm in its initial 1996-1997 run, and at first the idea of taking this fairly intimate piece to a wide-film format seemed counterintuitive. But on the Virginia screen the film lost none of the play’s intensity and it gained a welcome monumentality. The central set, the Danish throne room as a gigantic hall of mirrors flanked by a warren of corridors and fissured by secret passageways, is made for the wide image.

Scale of time also matters. By playing the full version, Branagh can give full weight to the father/ son parallels that riddle the play. If Olivier’s Hamlet was about a son’s love for his mother, Branagh makes the play about the strife between fathers and sons, with women caught in the middle. Hamlet Sr./ Hamlet Jr., Claudius/ Hamlet, Jr., Polonius/ Laertes, old Norway/ Fortinbras, and even the Player’s speech about the murder of Priam: the parallels are in Shakespeare’s text but played out at proper length they snap into sharp relief. Once Laertes is off to Paris, Polonius makes sure he’s spied on, just as Claudius orders Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern to watch Hamlet. In his turn, Hamlet assigns Horatio surveillance duty during the play-within-a-play (a piece of action nicely caught in the opera glasses that Branagh’s choice of period allows). Branagh’s decision to emphasize the military politics around Fortinbras’ march into Denmark helps justify the 70mm format and his decision to set the action in late nineteenth-century Europe; it also allows him to expand, through crosscutting set up early in the movie, the plot of another son at odds with his father.

Sex is important in this game. Branagh presents flashbacks to Hamlet and Ophelia in bed together, accentuating the prince’s later indifference and motivating her despair at his rejection. Not that the fathers don’t clock some mattress time too. Claudius the urbane politician becomes an infatuated newlywed, and Derek Jacobi gives to my mind a definitive performance. Even Polonius, usually treated as a pompous ass, smokes worldly little cigars and has a drab tucked into his bed, so that his advice to Laertes and Ophelia about proper conduct becomes not only patronizing but hypocritical.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

Spall, a temporizing Rosenkrantz, was present for much more of the filming and was eloquent in explaining how shooting in long, wheeling takes demanded great precision from the actors—hitting marks, using body language, and timing speeches carefully.

Branagh put the bulky 70mm camera on a dolly, then reinforced the studio floors so that no tracks or boards were necessary; the camera could glide anywhere. “Walk and talk” technique, which I’ve blogged about before, comes home to roost in a Shakespeare film; Branagh wanted continuous shots so that the audiences could follow the flow of the speeches, and it works very well.

In fact, Branagh’s editing varies in a patterned way across the play. Acts I and III are briskly cut, averaging about 5 seconds per shot. Acts II and IV rely on much longer takes, typified by the tracking-shot arabesques, and they average 10-11 seconds per shot. And Act V? Here, as you might expect, Branagh pushes the pace to suit the converging plotlines and the burst of poisonings at the climax: the average shot runs about 3 seconds. This seesawing rhythm helps sustain viewer interest across four hours, and it shows an unusually geometrical approach to a movie’s overall architecture.

In his program review, Roger points out that the play remains deeply mysterious, even in a production as lucid and buoyant as Branagh’s. Hamlet is of course one of the most fascinatingly inconsistent characters in literature. I’ve read the play probably a dozen times and seen many film versions of it, and I’m inclined to think that in Hamlet Shakespeare is experimenting with how indeterminate a character can be and still be intelligible to us. It’s not that he’s indecisive; we have to decide what he truly is, and Shakespeare makes our task very hard.

All the other characters in the play are complicated but consistent. Only Hamlet seems to reinvent himself at every entrance. He tells us that he will put on an “antic disposition,” but before he’s gotten very far with his fake madness, he tells Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern of his strategy, knowing that they are likely to report it to Claudius. This has the effect of letting Hamlet behave any way he wants, sincere or duplicitous, calculating or mad. When he’s around others, he’s always “on,” and this makes his true nature and purposes difficult to divine.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

The questions tease you right to the end. Hamlet finds Laertes’ plunge into Ophelia’s grave overdramatic, but he goes on to declare that he himself loved her with the strength of forty brothers. Before the climactic duel, Hamlet apologizes to Laertes (“I have shot my arrow o’er the house/ And hurt my brother”), but it seems almost bad faith, given all the misery he has helped cause. Is this a morally obtuse sincerity, or another masquerade? It’s this Hamlet, reliably unpredictable, that Branagh’s manic-depressive performance brings home so forcefully.

The unwitting wisdom of the suits

It’s common to say now that the 1970s was the last great era in American cinema, followed by the degradations of the blockbuster 80s, but that remains little more than PR. Putting aside the “revolution” of the 1970s, which seems to me overrated, I’ll just offer the opinion that the 1980s brought us many worthy films, some of them quite daring. For example, one of the sweetest “little movies” of the era is Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983).

It’s a comedy, at once dry and warm, about an oil executive sent to buy a small Scottish town and beachfront in preparation for the installation of a pumping rig and refinery. Forsyth’s script reverses the cliché. The townsfolk, far from clinging to their beloved tradition, are in fact anxious to sell and look forward to being rich. The young executive, Mac, doesn’t try to drive a hard bargain but settles into the rhythm of a life different from that he has known. His boss, a passionate amateur astronomer, surprises everyone with his final decision about the deal. You might call Local Hero one of the first films about the clash of global capitalism and community values, but though that’s accurate, the schematic formula doesn’t capture the understated humor and humanity of Forsyth’s treatment.

Forsyth is at Ebertfest for a screening of his no less brilliant Housekeeping; see Jim Emerson’s eloquent and poised review here. But I wanted to ask about Local Hero. The Scottish village is rendered with the affectionate good humor we find in Ealing comedies, and Forsyth mentioned that after he’d made the film he discovered an Alexander Mackendrick movie, The Maggie (1955), that prefigured his. For me, there were echoes of Jacques Tati in the long-shots and sound gags, and Forsyth confirmed that one of the formative films in his youth was M. Hulot’s Holiday, screened by an indulgent school head.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

The movie makes a running gag of the red phone booth through which Mac communicates with Houston. Forsyth remembered that he had a tail-end of a long shot of the town, with the booth standing out sharply. He had just enough footage for a fairly lengthy shot. So he decided to end the film with that image, and he simply added the sound of the phone ringing.

With this ending, the audience gets to be smart and hopeful. We realize that our displaced local hero is phoning the town he loves, and perhaps he will announce his return. This final grace note provides a lilt that the grim ending would not. Sometimes, you want to thank the suits—not for their bloody-mindedness, but for the occasions when their formulaic demands give the filmmaker a chance to rediscover fresh and felicitous possibilities in the material.

Salvation through self-punishment

Another outstanding film of the 1980s is Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), which he brought to Ebertfest in a sparkling print. Schrader is one of two American film critics who became major directors (Peter Bogdanovich is the other), and there’s little doubt that he’s the most cerebral and theoretically inclined of that group known as the Movie Brats. Even if he hadn’t written milestone screenplays (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) and made provocative films (Blue Collar, Hard Core, Affliction), he would be remembered for his critical writing. A trailblazing essay on Joseph H. Lewis, “Notes on Film Noir,” the essay on the yakuza film, and the book Transcendental Style in Film (1972) made Schrader a distinctive voice in American film culture. Fortunately you can now read his entire oeuvre online at paulschrader.org.

While the youthful Schrader expresses admiration for Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch, he’s no cheerleader for the New Hollywood. It’s bracing to watch him tear Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant limb from limb. The website displays each article in situ, on its original page of print. Since he wrote for many alternative weeklies, ads for bongs and day-glo paint lie alongside Schrader’s reflections on Bresson and Boetticher.

Although I also admire Patty Hearst, Mishima is my favorite Schrader-directed project. I think it’s one of the most artistically courageous films in American cinema. Putting the dialogue almost entirely in Japanese and focusing on a writer few Americans know, it compounds its difficulty with a daunting structure. On one axis, we get four chapters: Beauty, Art, Action, Harmony of Pen and Sword. On another axis, there are three interwoven strands: an account of the final day of Mishima’s life, when he seized control of a general’s office in order to address the garrison; a chronological biography, from his childhood to his adulthood; and stylized, efflorescent scenes taken from three Mishima novels. All these strands knot in the film’s final moments, when Mishima commits seppuku in the office and we see the culmination of the action shown in the novels’ tableaus. A “cross-hatched” structure, Schrader calls it.

The three strands are kept distinct through some technical markers: black and white for the biographical scenes, cinema-verite color for the 1970 attack on the garrison, and stylized color and setting for the extracts from the novels. Schrader explained that he had originally wanted to use video for the novel scenes, but his brilliant production designer Ishioka Eiko told him that the results might not be effective. Instead, she supplied designs of a dreamy radiance.

At the same time, both the biographical scenes and the tableaux take us through different eras of Japanese history, but in a way that sharpens comparisons among them. In the 1930s the boy Mishima glimpses a female impersonator at the kabuki theatre, but in his novel of the period, Runaway Horses, the young men formulate their plan to restore the emperor through an attack on corrupting capitalists. The sets for Kyoko’s House have, Eiko explained, ugly design because in the 1950s the Japanese were copying ugly American designs (though the results look pretty ravishing onscreen).

Schrader wanted to avoid the classic plot trajectory of a hero overcoming obstacles. He sought instead to present the way that a person’s life “becomes more and more fascinating, but you never really understand it.” The shuffling of chronology let him juxtapose different aspects of Mishima’s nature. The man wasn’t exactly contradictory, Schrader says, but rather “compartmentalized”: He could keep his aesthetics, his homosexuality, his militarism, and his childhood distinct, and the film aims to show these different facets of his career.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Schrader’s film enacts the blending of art and life in its very imagery. At the climax, in the biographical strand Mishima climbs into a jet and the black-and-white imagery gains radiant color as he stares into the sun. The shift brings the biography up to 1970, and so provides a transition to the color footage of the writer’s last day, but it also recalls the opening credits, with the sun rising, and the closing shot of the cadet Isao about to slash himself.

Schrader regrets the transition showing Isao running to the beach, because the imagery shifts from Ishioka’s stylized world to something more realistic (albeit with glowing amber rocks). So for the upcoming Criterion DVD release he has fiddled with the final shots so that the sun and sky look far more abstract. Evidently he wants the world of art and the world of life to remain stubbornly apart—denying to his film what his protagonist yearned for.

You might object that the film’s formal intricacy and specialized themes make for a fairly chilly experience. It isn’t a wildly emotional movie, that’s true; it has some of that ceremonial, contemplative quality you get from a Philip Glass opera, which provides a theatre of pictorial attitudes rather than action. (For an example, see coverage of the current Met production of Glass’s Satyagraha.) No coincidence that Glass provided the score for the film, which he wrote without seeing any footage and which Schrader cut and shuffled to provide cues. Glass obligingly rescored the film to fit the musical collage Schrader wanted.

The film provides a visceral and a sensuous experience, but it doesn’t carry you off on waves of emotion. It will never be popular on a massive scale, because it makes almost no concessions to what people like in biopics. But if you can adjust yourself to a solemn celebration of blood and beauty, Mishima offers unparalleled rewards.

More from Schrader

“Inspiration is just another word for problem-solving.”

Schrader’s intellect never lets up. What other filmmaker could produce such a thoroughly informed academic case as he does in the 2006 “Canon Fodder” (available on his site)? One on one, I peppered him with questions and he answered with seriousness and subtlety. Two themes ran through his comments: his approach to direction and his view that cinema is dead.

On his directing: Until his last project, he embraced the “well-made film.” He shoots with a single camera, and plans his takes cut to cut. (That is, not a lot of coverage from many angles that will be winnowed out during editing.) He doesn’t storyboard because he wants to develop the staging organically on site. He visits the set, tries out blocking with the actors and DP, then decides on the spot about the breakdown into shots. For the Temple of the Golden Pavilion scenes of Mishima, like the one above, he and cinematographer John Bailey played “dueling viewfinders,” pacing around the actors to test points of view and then settling on tracking shots which incorporated the best angles.

But for his latest project, Adam Resurrected (2008), Schrader switched to a rougher style. Now, he says, he uses two cameras and he likes the bouncing and swaying frame yielded by the Bungee Cam. “I’m sick of the well-made film.”

On new media: Schrader’s stylistic turnabout comes from his conviction that cinema, “the dominant art form of the twentieth century,” is coming to an end. Today’s audience demands new forms of moving-image media. Thanks to television, young people have seen every conceivable story, so narrative is “exhausted” as an expressive resource. They expect their media products to be free, available on demand, and interactive. The result is a challenge to traditional media on every front: financial, cultural, and artistic.

Schrader looks to the Internet as not just an intriguing option but film’s destiny. So while he is planning a traditional “three-act” film, he also has written a screenplay for a 75-minute Net movie. In his essay, “Canon Fodder,” he predicted the end of traditional cinema but thought that he could keep going before the revolution. Now, he says, the sun is setting faster than he expected and if he wants to make more films he has to adjust.

I’m no prophet, but I don’t share his beliefs about the imminent collapse of traditional cinema. I also think that Web-based films, with viewers tempted to browse and graze and fast-forward, will limit aesthetic options. The computer monitor is not as hospitable to contemplative cinema, which demands that the audience patiently submit to unfolding time. When I worried at a panel that an Ozu or a Bresson could not have originated in the age of YouTube, he told me, “Get over it, David!” Though we disagree, talking with him was terrifically stimulating. I left with the hunch that Schrader will continue to devise some characteristic provocations for new media, for which we should be thankful.

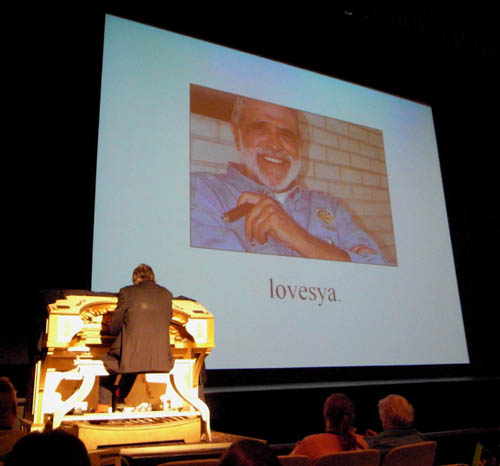

Envoi

Dusty Cohl was one of the mainstays of Ebertfest, as well as the founder of the Toronto Film Festival and a shot in the arm to world film culture. He died last fall. He was honored by several events at this year’s festival, notably the biographical film, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, by Barry Averich (The Last Mogul). On my first visit to Ebertfest, the tough, salty guy with the quick grin and the cowboy hat immediately made me feel welcome, and he did the same when Kristin came along the following year. Everyone whose life he touched was grateful for Dusty’s generosity of mind and spirit.

Minding movies

DB here:

When we watch films, our bodies and minds are engaged at a great many levels. Nobody doubts this claim. The interesting questions are: What forms does this engagement take? What gives movies the ability to seize our senses, prod our minds, and trigger emotions? How have filmmakers constructed films so as to tease us into such activities? What, to use a phrase from the philosopher Noël Carroll, creates the power of movies?

On this blogsite, I’ve touched on such questions in concrete cases—how eye movements shape our uptake of story information (here and here), how suspense can be created and sustained (here). Those are just small-scale samples of what is, to me, an exciting and promising way of studying certain aspects of cinema. That research trend is growing substantially, and an upcoming event on our home turf marks a new phase.

In June, the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image will hold a conference here in Madison. This organization was officially created in 2006. Its membership grew out of an informal group of scholars who had been meeting every couple of years since 1997. The meetings have been stimulating affairs, bringing together film historians and theorists, filmmakers, philosophers, and social scientists. Now we’re a full-fledged, incorporated association. We have annual membership dues (cheap at $25), a slate of officers, and a set of bylaws. The Society’s conferences will become annual next year, when we convene at the University of Copenhagen.

You can learn details about the organization here, and you can scan the conference schedule here. There’s also information about getting to Madison and visiting local attractions. (I recommend The House on the Rock.) The earlier incarnation of our group, The Center for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has a rather full archive here.

As president of SCSMI, I’ve had my say about the organization’s remit on the webpage. I’m using today’s blog entry to gesticulate toward some ways that the organization tries to advance our understanding of films, filmmaking, and film viewing. I’ll also shamelessly promote our event.

What is this fascinating new film theory known as cognitivism?

There are, roughly, two ways to think about doing film theory. One way is to look at a body of research or reflection in some established area (history, philosophy, psychology, etc.) and ask: What can it tell me about movies? So you might look at Freudian psychoanalysis or Gestalt perceptual psychology as a whole and then home in on ideas that seem to have relevance to cinema.

The other way to do film theory is to look closely at some filmic phenomenon and ask: What’s the best way to understand this aspect of movies? Your reading and thinking might then lead you to adjacent fields of inquiry for help. In the first instance, you start broad and move to particular cases. In the second, you start with particular cases and explore what broader ideas or information can shed light on them.

On the whole, academic film studies of the 1970s and 1980s started from the big-picture end. Several scholars decided, on various grounds, that psychoanalysis (a mixture of Freudian and Lacanian versions), provided a powerful explanatory system for virtually all human activity. The ideas of that system were then mapped onto many humanities disciplines, and then applied to particular instances of literature, the visual arts, and cinema. Many times, the big system became a doctrinal whole, a Theory of Everything, that was unquestioningly accepted.

In a 1989 essay called “A Case for Cognitivism” (available online here), I suggested that Freud did not intend his theories to become this sort of all-encompassing doctrine. And whatever Freud thought, in that essay and a later one for Post-Theory I argued that it’s more fruitful to develop film theories in a middle-level fashion, shifting from concrete problems to broader explanatory frameworks. My collaborator Noël Carroll called this focus on particular problems “piecemeal” theorizing.

It was through middle-level, piecemeal thinking that I first became interested in the cognitive sciences. During the early 1980s, I was concerned to understand how films told their stories. This process was usually called narration. From the start it seemed clear to me that filmic storytelling doesn’t work unless the spectator does certain things. We make assumptions, frame expectations, notice certain things, draw inferences, and pass judgments on what’s happening on the screen.

Film narratives are designed for just this sort of active pickup. I was interested, then, in how certain traditions of filmmaking shaped that pickup—by parceling out story information, composing shots, structuring scenes, and so on. Going beyond those particular traditions, what general capacities of spectators enabled us to understand the twists and turns of a film’s action, as presented by the movie?

During the 1960s Christian Metz had posed my question in a precise and provocative way—“We must understand how films are understood”—and had used it to found his initial version of a semiotics of cinema. But by the early 1980s, it wasn’t a question that much exercised people working in the dominant paradigm of the moment, psychoanalysis. Moreover, I was and remain skeptical of the psychoanalytic framework; I don’t think it has very solid scientific support.

So I began reading in other domains of psychology. At this point, the “cognitive sciences” were coming into their own as a result of work in linguistics, psychology, and anthropology. I didn’t have the benefit of Howard Gardner’s masterful state-of-play survey The Mind’s New Science (1985), but I saw some of the convergences he was pointing out. Perceptual psychology, social psychology, the shortcuts and shortcomings of informal reasoning, studies in classification and story comprehension–all these illuminated my central questions.

Characterizing, quick and dirty

The answers I proposed to those questions showed up in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). Nowadays we’d call it an attempt at reverse engineering. In many instances, that book argued, features of narratives in film seemed designed to solicit activities that research in the cognitive sciences has studied. Here’s one example.

The first time we encounter a character in a narrative, we tend to form an immediate, fairly fixed judgment about what sort of person she or he is. Why is this? Why don’t we suspend judgment and wait until we have more information? At least two reasons.

First is what psychologists call the primacy effect, the likelihood that the first item or few items in a series tend to form a benchmark for what will follow. Here are two multiplication exercises:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = ?

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8 = ?

Give a person just one of the problems and ask him or her not to do the math but to quickly offer a rough estimate of the size of the result. What happens? People given the first problem tend to give bigger estimates than those given by people who see the second problem. Even though the product is exactly the same, the order of presentation—starting with large or small numbers—seems to have biased people toward different results. The initial items become a rangefinding device for later judgments.

A second reason for our snap judgments about characters stems from a well-supported finding of social psychology. We tend to size up other people using a rule of thumb, or heuristic, that attributes their actions to personality rather than to circumstances. If someone acts bossy in a meeting, we’re inclined to say that the person has an aggressive nature. But if you ask the person why he or she came on so strong, the answer is likely to be “I was having a bad day,” “The responses I was getting were just so lame,” “The pressures of those meetings are intolerable,” and so on. This is called the fundamental attribution error. We tend to assign behavior to character traits rather than take into account contextual factors. We are biased toward believing that others’ misbehavior is due to their temperament while ours was forced by circumstances beyond our control.

In real life, the primacy effect and the fundamental attribution error can be quite unfair ways of coming to conclusions, and they can lead us astray. But filmmakers and other storytellers, being intuitive psychologists like the rest of us, realize how strong these heuristics are, so they design their stories so as to make use of them. Usually, when a character walks into the story world, he or she is characterized by signaling key traits right off the bat.

Consider Back to the Future (released the same year as NiFF was published). It might have begun with Marty McFly skating down the street for several minutes on the way to Doc’s laboratory. Instead, the narration introduces Marty by showing him cranking up the lab’s amplifier to overdrive. He strikes a star pose, hits a guitar chord, and is blasted off his feet. He’s shaken up but awestruck: “Whoa. . . Rock and roll.” We now assume that Marty likes to take risks, that he’s committed to his music, that he’s a bit preening, and that he can bounce back. Likewise, before Marty comes in, during the opening shots exploring the lab, we get information about Doc as well, though more indirectly. For both characters, the narration encourages us to leap to conclusions that will be confirmed again and again in the story that follows.

Sometimes, though, filmmakers thwart our propensities by either neutralizing the initial cues (we don’t know how to read the character) or offering strong ones that are later countermanded (we’ve been led to misread the character). Preminger offers wonderful examples of both possibilities in Anatomy of a Murder. Either way, the filmmaker is still exploiting the primacy effect and the fundamental attribution error, but in order to yield different experiences. Meir Sternberg’s superb book, Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978), points out such strategies and explores in detail what he called, “the rhetoric of anticipatory caution”—the ways that novelists trigger the primacy effect only to force us to reevaluate our snap judgments. Sternberg was, I think, one of the first narrative theorists to bring cognitive research to bear on storytelling strategies.

I found, in short, that experimental results in the cognitive sciences could explain, in a fairly direct way, many of the tactics that stories use to engage us. Contrary to what my Wikipedia entry implies, I’m not a cognitivist 24 hours a day; many of the research questions I tackle don’t depend on such assumptions. Still, since NiFF, I’ve revisited them a few times. Making Meaning (1988), for example, tried to show that a lot of cinematic interpretation is explainable in cognitive terms.

Most recently, some essays in Poetics of Cinema (2007) draw on psychological and anthropological research to clarify why films use certain formal strategies. For instance, what aspects of Mildred Pierce mislead us about what is happening, and how are we led to misremember those aspects? Why do actors stare at each other in a way we seldom see in life? And why don’t they blink the way we do? Another essay in the collection, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” moves to broader terrain. It argues that a great deal of our understanding of films relies not on codes particular to cinema (contra the semiotic tradition) but rather on our everyday inference-making habits and skills.

The cognitive turn

Written in 1982-83, Narration in the Fiction Film leaned heavily on what was then called “New Look” psychology, the first wave of cognitive research in psychology. The pioneers of that program, such as Jerome Bruner, R. L. Gregory, Ulrich Neisser, and others, emphasized the mind’s role in actively building up structures of meaning on the basis of incomplete or ambiguous information. So my claims that films cue us to flesh out their action, invoke schemas (knowledge structures), ask us to reorganize story order, and to fill in missing bits—all stem from that research program. The art historian E. H. Gombrich, another big influence on me, was perhaps the first person to see how New Look psychology could inform theorizing in the humanities.

In the late 1990s, cognitively inflected film theory really took off, and in directions that shaped the growth of SCSMI. The first avatar of the SCSMI was founded by Joseph and Barbara Anderson. Joe and I were graduate students together at Iowa in the early 1970s, where he wrote a dissertation on binocularity in the cinema, and later we worked together here at Madison, where Barb was a grad student. Joe taught a course in film perception that I sat in on occasionally, and it was a revelation. When NiFF came out, Joe (by then a film producer) felt encouraged to go on with his own work, and the result was The Reality of Illusion (1998). It proposed an alternative to the New Look orientation, grounded in J. J. Gibson’s theories of ecological perception. Since then, Joe and Barb have published two anthologies, with contributions from SCSMI members.

At the same period, Torben Grodal published Moving Pictures (1997) a comprehensive theory of cinema grounded in the cognitive sciences, with particular focus on brain functions. Torben was also a founding member of the SCSMI group.

Since 2000, publications in the area have increased markedly, parallel to the growth of cognitive studies in literature and other areas. I hope to discuss some of these books and articles in a later blog.

Broadly, cognitive film theory has tracked the development of the cognitive sciences. After the New Look and ecological frameworks, we’re seeing more emphasis on evolutionary psychology and neuroscience as explanatory forces. Film scholars who talk about adaptive fitness and mirror neurons are still, for the most part, doing middle-level, piecemeal theorizing—trying to explain particular processes by appeal to what scientific research has brought to light. None, I think, expects cognitivism to provide a Big Theory of Everything.

Early on, Noël, I, and others sought to show that the cognitive perspective offered better explanations for some aspects of cinema than the dominant psychoanalytic approach. We were sometimes chastised for being pugilistic and polemical. Yet interestingly, nobody responded to our arguments, let alone replied at the same level of detail. The situation reminded me of Godard’s response to people who complained that Letter to Jane (1972) mistreated Jane Fonda. His reply was: “I merely wrote her a letter, but she never answered.”

In the years since, I have yet to see a substantive critique of the cognitive research tradition in film studies. The only extended argument I know of isn’t really focused on cognitivism and is surprisingly flimsy. (My response to it is here.)

Advocates for Poststructuralist or Cultural Studies perspectives sometimes dismiss the cognitive framework as “common sense.” But common sense is in the eye of the beholder, and there’s no reason to assume that flagrantly uncommensical claims are any more likely to be accurate than those which seem intuitively right. In doing research, we just try to ascertain the evidence for any belief, commonsensical or not. The primacy effect might seem simply to rely on the old saw, “First impressions matter,” but it’s good to know that at least one commonplace is well supported. By contrast, the fundamental attribution error doesn’t on the face of it seem either common sense or not. It’s something that our folk psychology doesn’t guide us toward or away from. It’s actually a fresh discovery about some habits of our minds.

Moreover, a great deal of cognitivism flouts what some might take as common sense. Before Chomsky, most intellectuals thought that language was social through and through. He was able to show that certain features of it, including syntax, are likely to be part of our biological endowment. A lot of cognitive social psychology has been dedicated to showing how common-sense inferences are often illogical. These findings are now being popularized in books like Cordelia Fine’s A Mind of Its Own: How Your Brain Distorts and Deceives, and Thomas Kida’s Don’t Believe Everything You Think (from which my multiplication example comes). As for humanists’ suspicion of science, I address that unfounded fear in the introduction to Poetics of Cinema. If you prefer big-picture arguments about the issue, try Edward Slingerland’s new book.

Movies on the brain

The real debate on cognitivism in film studies has yet to take place. Meanwhile, the cognitivists keep plugging away. Over the years, the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image has attracted, broadly, three sorts of persons. All are represented in our upcoming conference.

*There are the film-trained academics like me, who have branched out into cognitive film theory to illuminate particular research projects. Our June gathering includes a great many such scholars, many of them pioneers in the cognitive perspective like the Andersons, Carroll, Grodal, Murray Smith, Carl Plantinga, Patrick Colm Hogan, et al.