Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Professor sees more parallels between things, other things

An Onion report brought to my attention by Stew Fyfe celebrates the comparative method (“Professor Sees Parallels between Things, Other Things”). I confess myself an admirer of this approach. We can learn a lot by setting two things alongside one another. It’s even better if we have a reason to do so.

I thought about this when Kristin and I visited the Auckland Art Gallery in May. Their modern wing was hosting an intriguing Triennial show called Turbulence, an array of contemporary work, but I was more drawn to the Museum’s traditional collection. I saw a very nice Brueghel (he’s one of my favorites) and an arresting Adoration of the infant Jesus, painted by the rather minor Francisco Antolinez y Sarabia (1644-1700).

Though indifferently painted, it reminds me of El Greco in its tipped, piled-up figures. I enjoyed the acrobatic Madonna: Is she crouching, leaping, or tripping? It recalls Eisenstein’s point that much classic art creates impossible contortions which suggest various stages of movement, a point I discussed in a blog last year.

To get to those parallels: We wandered through the Gallery’s sturdy collection of British art and I was once again captivated by narrative painting of the late nineteenth century. Paintings have long been assigned the task of telling stories, but usually those stories were already well-known to the viewers, drawn as they were from history or mythology. In what’s come to be called “narrative painting,” the stories seem to be taken from life, although they’re really invoking our knowledge of prototypical situations.

Without the advantage of easily recognized religious or mythological tales, such pictures usually rely on a title to coax us fill in the story. The title specifies the context for the concrete action we see. For example, two prosperous young women are sitting in a garden. One is reading from a sheet of paper. What’s going on?

The title, Her First Love Letter, helps us zero in on specific aspects of the action and fill in the situation. The girl on the left, bathed in light, leaning forward eagerly and wearing the pale frilly dress, can be seen as the more inexperienced of the pair, caught up in the anticipation of the young man’s ardor. The more worldly woman sits relaxed, perhaps a little skeptical but also tolerant of the ways of young love. You can’t see it in reproduction, but the flower in the darker woman’s bosom is a mere spatter of paint, the brightest bit of red in the picture. The painting is by Marcus Stone and dates from 1889.

Narrative paintings like this are evidently one source of early cinema’s approach to staging and composition. This “full shot” somewhat recalls the sort of thing we see throughout European filmmaking of the first twenty years. Staging the action on more or less the same plane, viewing from a distance characters grouped around a table, is very common at the time.

Another picture can teach us a bit about acting.

Here the body language and facial expressions yield hints. The man sits casually, the woman more rigid, and his arm is not quite brushing hers. Absorbed in his book, he seems unaware she’s there. She sits stiffly, with downcast eyes and an expression that seems stoic. You can even take her slight unfolding of the colorful shawl as an invitation to the touch that he doesn’t offer.

This painting, by Walter Sadler, is called Married (undated but presumably turn of the century). Once the title tells us that the couple are husband and wife, we can infer that their passion has subsided, largely through the husband’s self-absorbed inattention. Did he really need to take three books into the garden? The single-word title also lets us see certain elements as iconographic clues. The woman’s white dress and bouquet recall the wedding, and the fallen badminton birdie and racket suggest an earlier time when they played together. Kristin sees sexual symbolism in the flowers in her lap and the books in his. The gallery’s caption suggests that the turtle is going off to hibernate and that the blocked-off back garden suggests no future for the relationship.

Putting aside the symbolic connotations, though, the strong cues supplied by the figures’ postures and expressions point us toward the sort of slight changes in body language provided by acting in early cinema. Some viewers think that early film acting was expansive and overblown, but that’s not always the case. Here is an instance from Evgenii Bauer’s Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913), in which Vera starts to confess an indiscretion to her admirer Prince Bol’skii. She raises her hands , an obvious indication of her anxiety, but more subtle is what’s going on below. At first her legs are turned toward him, but as she lifts her hands they shift a bit further away from him. Her small adjustment of her torso is a kind of accompaniment of the hand gesture, like a harmonic change accompanying a melody.

Both Her First Love Letter and Married lay their figures out along a line perpendicular to the viewer, a common strategy in early film. I discuss this in Figures Traced in Light; for other examples, see figs. 2A.7-11 here. The alternative is to arrange figures in depth, and one of the jewels of the Auckland collection illustrates this nicely. The title is more allusive than our others: For of Such Is the Kingdom of Heaven (1891), a reference to Jesus’s admonition to let children come to him (Matthew 19:14). The painter is Frank Bramley.

We are watching the funeral of a child, with the family carrying the almost weightless casket, swathed in flowers. In the picture’s suggestion of solemn movement, we might be tempted to say, we find early cinema before cinema. More to my point, though, is the way in which a diagonal layout creates a play between strong composition and rich ancillary effects.

The picture is composed along two lines, with the adult mourners grouped at the point where the procession intersects with the horizon. That horizon is given a widening sliver of light, a rolling wave that accentuates the heads of the two women right of center. The central bright patch of grays, whites and pastels is set off against the earth tones of the docks and the robust but respectful working-class onlookers. At the peak of the picture, the crowning moment of the angle formed by horizon and pier, is the bowed black head of the father.

The depth composition also guides our visual search, allowing us to discover a great variety of postures and facial views. The little girls in the center stride and sing from their hymnals dutifully, while the girl in the straw boater, bearing a huge bouquet, is staring at us—a disturbing effect, since her face is unhealthily gray. Will she be another victim?

In the years after 1908 or so, many filmmakers adopted the diagonal layout as a dynamic way to play out scenes. Here’s an instance from Bauer’s Twilight of a Woman’s Soul. Vera is calling on a men’s club where they practice fencing and pistol shooting. They put on a show for her.

The diagonal draws our attention to the target, but Vera’s contrasting bright costume and her tilted face are further accented by putting her at the opposite end of the vector. All these factors make sure we note that her eye is on the handsome marksman, Prince Bol’skii. Receding compositions like this offered 1910s filmmakers a way to guide visual search in ways similar to Bramley’s painting.

Even more intriguing to me in For of Such Is the Kingdom of Heaven is the figure who’s evidently the dead child’s mother. She is bowed and tucked away to the right of the husband and behind two pallbearers. Bramley has taken advantage of the diagonal view to mask her off, as if viewing her grief would be too great for us to bear. This device has a parallel in cinema too.

A film scene unfolds in time, unlike a painting’s action. So filmmakers can block certain parts of the action and then, at the proper moment, reveal it. If Bramley were working in film, he could arrange his cortege so that the mother’s face came gradually into view as the group advanced, creating both a dramatic and pictorial climax. This blocking-and-revealing tactic is common in the choreographed staging we find in 1910s films, and again Bauer’s Twilight of a Woman’s Soul offers a nice illustration.

Vera, now ill, is visited by her suitor Prince Dol’skii. Her parents object, but she begs her father to let him in, and he reluctantly agrees. As the action starts, she clutches her father as the doctor looks on. The men’s bodies mask a doorway in the background, and as a servant comes through it, they pivot, revealing him.

I’d argue that the servant’s entrance primes this area of the shot for the dramatically important entrance, that of Dol’skii. The father, the doctor, and the servant withdraw toward the back wall. After a pause, the Prince enters and advances.

Vera greets him warmly as he takes the father’s place in the shot.

I’m not arguing that these particular paintings influenced filmmakers, only that the principles that the painters employed were picked up by directors. The more general point is that in understanding film aesthetics, we can usefully compare movies to other movies, and movies to other arts. By doing this, we sharpen our sense of what various media can do. The professor in the Onion story wisely notes, “It’s not just similarities that are important, though—the differences between things are also worth exploring at length.”

All paintings shown here are in the permanent collection of the Auckland Art Gallery. Bauer’s film is available on a Milestone DVD. I hope to blog more about his work later this summer.

Simplicity, clarity, balance: A tribute to Rudolf Arnheim

DB here:

On Monday, at age 102, Rudolf Arnheim died. You can read his obituary here, and this is a lovely website devoted to his work. He was one of the most important theorists of the visual arts of the last century, and he had enormous impact on how people, including Kristin and me, think about film.

A good Gestalt

In parallel with E. H. Gombrich, who died in 2001, Arnheim brought modern psychological concepts into the study of visual art. His most famous work, Art and Visual Perception (1954, new version 1974) has the sort of magisterial presence that very few books in any era achieve. Arnheim delighted in the fact when, visiting a painter’s studio, he would find a spattered copy on the workbench. Of the revised edition, entirely rewritten, he noted:

All in all, I can only hope that the blue book with Arp’s black eye on the cover will continue to lie dog-eared, annotated, and stained with pigment and plaster on the tables and desks of those actively concerned with the theory and practice of the arts, and that even in its tidier garb it will continue to be admitted to the kind of shoptalk the visual arts need in order to do their silent work (new ed., x).

He aimed at theory that actively participates in the way artists do their job. The chapter titles of Art and Visual Perception deal with the nuts and bolts of picture-making: Balance, Shape, Form, Growth, Space, Light, Color, Movement, Dynamics, and Expression. No puns, slashes, dashes, or parentheses. What academic theorist today would so boldly announce their concern with the craft of creating images?

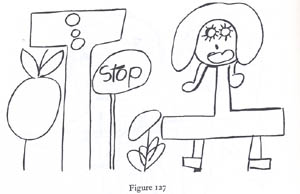

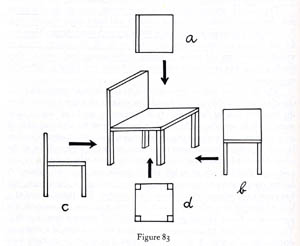

The book is subtitled, A Psychology of the Creative Eye, and the chapters’ subsection titles explain why. The hidden structure of a square . . . Vision as active exploration . . . Perceptual concepts . . . What good does overlapping do? . . . Why do children draw that way? . . . Gradients create depth . . . Visible motor forces . . . The priority of expression. Arnheim’s principal achievement in art theory was to integrate the Gestalt theory of perception with the traditional concerns of picture-making. He sought to show how perceptual laws discovered in the psychological laboratories of Berlin were intuitively applied by classic and modern artists.

As he put it, he was at the university at around age twenty:

My teachers Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler were laying the theoretical and practical foundations of gestalt theory at the Psychological Institute of the University of Berlin, and I found myself fastening on to what may be called a Kantian turn of the new doctrine, according to which even the most elementary processes of vision do not produce mechanical recordings of the outer world but organize the sensory raw material according to principles of simplicity, regularity, and balance, which govern the receptor mechanism.

This discovery of the gestalt school fitted the notion that the work of art, too, is not simply an imitation or selective duplication of reality but a translation of observed characteristics into the forms of a given medium (Film as Art, 3).

The Gestalters thought that these principles–figure/ground, completeness, good continuation, and the like–were fundamental to all human perception, across times and cultures. Art and Visual Perception makes a powerful case for this view. Today this position is so unfashionable that Arnheim’s calm confidence in it is quite stunning. For many scholars today, all that matters is what divides and differentiates us. But for eighty-plus years Arnheim emphasized ways in which we share a common experience of the world and of art.

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

Arnheim saw the same form-giving activity at work in “primitive” art, the art of children, and even the art of the mentally ill. It turns out that the “universalism” of Gestalt theory underwrites diversity no less vigorously than the most ardent postmodernism.

Flexible striving

Arnheim made another contribution to our thinking about art, one that I think is rarely recognized. In a bold stroke, he extended the Gestalt conception of form beyond its concern with geometrical qualities and argued that form was inherently expressive. A triangle resting on its base wasn’t just balanced; it was weighty. We see the weeping willow as not just curved but sad; a skyscraper isn’t just tall, it’s aggressively thrusting upward. Every shape or movement we apprehend has a distinctive flavor and feeling. Indeed, he writes, “expression can be described as the primary content of vision”!

We have been trained to think of perception as the recording of shapes, distances, hues, motions. The awareness of these measurable characteristics is really a fairly late accomplishment of the human mind. Even in the Western man of the twentieth century it presupposes special conditions. It is the attitude of the scientist and the engineer or of the salesman who estimates the size of a customer’s waist, the shade of a lipstick, the weight of a suitcase. But if I sit in front of a fireplace and watch the flames, I do not normally register certain shades of red, various degrees of brightness, geometrically defined shapes moving at such and such a speed. I see the graceful play of aggressive tongues, flexible striving, lively color. The face of a person is more readily perceived and remembered as being alert, tense, concentrated rather than being triangularly shaped, having slanted eyebrows, straight lips, and so on (Art and Visual Perception, first ed., 430).

Arnheim found feeling in his forms.

Moving pictures

Arnheim wrote about many artforms, including mass media in his 1936 monograph on radio. His book on cinema, Film als Kunst (1932), was quickly translated into English as Film (1933). Always in search of greater clarity and point, Arnheim rewrote it in 1957. Oddly, he didn’t update it: You’ll search in vain for examples from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s. The touchstones remain Chaplin, Keaton, von Sternberg, and the Soviets. Arnheim held that cinema was essentially a pictorial art (see my earlier blog on this question) and that synchronized sound added very little; in fact, it might even inhibit visual experimentation. It was so easy to convey a story point with dialogue that lazy filmmakers would simply create photographed stage plays.

As a result, Arnheim is usually taken to be the summation of a certain strain of 1920s film theory. Like many earlier thinkers, Arnheim emphasized how film technique reshapes what is filmed. Close-ups, shot design, camera angles, and cutting make cinema no simple medium of reproduction. Film form transforms the world that is photographed. This position, commonplace today, was a real advance in the silent era and gave cinema artistic respectability, a subject that Arnheim reflected on thoughtfully in the 1933 edition of Film.

Again, Arnheim did more than synthesize current ideas. Theorists’ hunches that film stylized reality could now be grounded in Gestalt ideas about medium and form. In effect, Arnheim rewrote Film in the light of Art and Visual Perception, and the result was Film as Art. Here is the most famous passage:

Not until film began to become an art was the interest moved from mere subject matter to aspects of form. What had hitherto been merely the urge to record certain actual events, now became the aim to represent objects by special means exclusive to film. These means obtrude themselves, show themselves able to do more than simple reproduce the required object; they sharpen it, impose a style upon it, point out special features, make it vivid and decorative. Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object (Film as Art, 57).

This, you might say, is Arnheim’s reply to Walter Benjamin’s theory of cinema as mechanical reproduction: no less than other artists, filmmakers use their medium, a photographic one, to create perceptually vivid effects akin to those in other arts.

Still, Arnheim held that film, like photography, has more limits than other arts. Tied to recording, film and photography can never achieve the range of expressive form we find in painting. I don’t believe this for a moment, but Arnheim clung to this opinion, I suspect, because of his deep love for creative freedom he found in other visual arts. And I sometimes think that for him, a painting harbored enough pushes, pulls, twists and torques. Movies just made explicit what was tactfully implied in still images.

Envoi

Kristin and I first saw Arnheim when we were graduate students at the University of Iowa, March 1972. He gave a lecture that stuck to his principles of 1933:

*Every art medium has a ceiling, beyond which it cannot effectively pass. The ceiling is somewhat low for the reproductive arts. Photography is more limited in what it can do than painting, and so is film.

*Films should be in black and white, the better to stylize reality. Are there no worthwhile color films? Pause. Red Desert, perhaps.

*Do you see many contemporary films? No.

Around 1980, I lined him up for a visiting lecture at UW. But he had to cancel; he had slipped on ice and broken his hip. He was then about seventy-five.

Later in the 1980s I visited Ann Arbor and had lunch with him. It was wonderful. By then I had read enough to ask him about Gombrich–an old friend and courtly opponent of his. (Read one of his reviews of Gombrich’s books to see what genuinely respectful disagreement looks like.) He saw pretty quickly that I was a Gombrichian and he gave a shrewd analysis of the dividing line: Gestalt psychology vs. ‘New Look’ cognitivism, illusions vs. expressive percepts, brain fields vs. schemas. He asked me to send me copies of my publications, which I did on and off during the decade. I never heard what he thought about my favorite fancy-pants sentence in Narration in the Fiction Film, when I contrasted J. J. Gibson’s theory of optical realism with Arnheim’s idea of expressiveness: “Gibson likes likeness, Arnheim loves liveliness.”

I thought of him often as I read more perceptual psychology. Gestalt work had once seemed to me a dead-end, but with David Marr’s theory of visual perception, a prototype of computational perceptual psychology, Gestaltism came roaring back. The “3D model representation” that Marr claimed operated in early vision uncannily echoes Arnheim’s discussion of our perception’s reliance on “characteristic aspects.” (Arnheim illustrates the idea with the various views of the chair, above. Which one is instantly recognizable as a chair?) And with contemporary interest in the relation between emotion and cognition, Arnheim’s theory of the expressive side of perception is creeping back too. Nothing worthwhile is forgotten, nothing goes away.

When we ran a book series at the University of Wisconsin Press, we were eager to publish an anthology of Arnheim’s film criticism, a collection originally published in German in 1977. Brenda Benthien, a close friend of Arnheim and his wife Mary, executed a lively translation and Arnheim supplied a touching introduction. A refugee of the Hitler years, an émigré across Europe and America, Arnheim summoned up the failure of the Weimar republic:

Even now I keep as a sort of talisman a bullet which in the days of the 1918 revolution, when I was fourteen, flew over the neighboring houses, bored a little hole through the windowpane, and fell inert on the carpet before my bed. Thus it began (Film Essays and Criticism, 3).

In the same introduction, Arnheim deplores the current state of cinema (“my basic objection to the talking film as a mongrel seems to me just as valid today as then”) and he warns against the cheapening of our vision:

Without the flourishing of visual expression no culture can function productively (5).

Aspiring film critics, and especially bloggers, should go back and read Arnheim on Keaton, Eisenstein, Gance, Pudovkin, Chaplin, von Sternberg, and other greats, as well as the essays “Style and monotony in film,” “Epic and dramatic film,” and especially “The Film Critic of Tomorrow.”

Scarcely a month goes by when I don’t have some idea that can be traced, however circuitously, to my reading of Arnheim. For instance, my blog on funny framings, posted a couple months ago, starts with his discussion of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. Arnheim’s theory of expression goes a long way toward explaining how composition can trigger laughter. I doubt that I’d be so alert to the possibilities of two-dimensional design in film shots if I hadn’t been tutored by Film as Art, Art and Visual Perception, The Power of the Center (1982, rev. 1988), his 1962 monograph on Picasso’s creative process in painting Guernica, and the essays in Toward a Psychology of Art (1966)–one of which is a skeptical review of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion. In preparing this entry, I found that my pleas that we probe the norms that guide filmmakers’ craft practices is just a clumsier restatement of this, which I discovered marked in Art and Visual Perception, the New Version:

Good art theory must smell of the studio, although its language should differ from the household talk of painters and sculptors (4).

Three years ago, after the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image convention in Grand Rapids, several of us from Madison–Ben Singer, Jen Chung, and Jonathan Frome–detoured back by way of Ann Arbor in order to call on Arnheim. He had just turned 100. He resided in an assisted-living facility, and his room was bright and clean, packed with books, remarkable drawings and paintings (Feininger, Köllwitz), a microfilm reader, and a worktable with a gigantic magnifying lens on an articulated arm. Conversation was difficult for him, but he seemed to understand everything we were saying. His smile was quick and his eyes were bright. When I showed him the first German edition of Film als Kunst I’d brought along, he turned it over in his hands as if he hadn’t seen one in years. He signed it, then shook his head apologetically at the shaky writing.

Now that Benjamin and Kracauer have become the prototypical Weimar intellectuals, it’s a pity that so many media students and professors are unaware of the importance of Arnheim’s work. His Leonardo-like interest in merging art and science is discouraged in a climate that posits the cultural construction of everything. He also writes with a grace and clarity that’s all too rare. In an unfashionable way, he exemplifies the passion, rigor, and dignity that interwar German intellectuals brought to the study of the arts. A lot of what he believed remains–what’s the word I want? Oh, yes–true.

Rudolf Arnheim, with Jonathan Frome, July 2004.

Line illustrations come from Art and Visual Perception.

Once more on New Line, Peter Jackson, and The Hobbit

Gandalf introduces Bilbo to Beorn. Illustration by Michael Hague

Kristin here–

After several months of raised and dashed hopes, the question of who will direct the film of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit remains open. I first weighed in on the question back on October 2 of last year, when this blog was in its infancy. MGM had just announced that they would be making The Hobbit and hoped that Peter Jackson would direct. At that point I was trying to sort out Peter Jackson’s large number of film projects and to explain how his schedule might include time to direct The Hobbit.

Subsequently there was a clarification. MGM, which owns the distribution rights to any film version of the novel, would co-produce with New Line, which produced The Lord of the Rings and owns the filmmaking rights for The Hobbit.

Then, early this year, New Line founder and co-president Bob Shaye declared in an interview that Jackson would never direct The Hobbit while he is in charge of the company. The obstacle was a lawsuit that Jackson had filed against New Line; he wanted an accounting of earnings on the DVDs of The Fellowship of the Ring and various licensed products. See my January 13 attempt to explain all that.

As before, no doubt negotiations are going on behind the scenes. To reiterate my disclaimer from the earlier entries, I have no inside information, given that my contact with Jackson and the other filmmakers was back in 2003 and 2004, during the research for The Frodo Franchise. As someone who has followed the situation very closely since undertaking my book back in 2002, however, I can make what I hope are some enlightening comments on the scraps of news that have appeared since January.

A faint hint that Shaye might possibly be backing away from his absolute rejection of Jackson as director for The Hobbit came in a brief interview in the April issue of Wired (also online). As far as I could tell, this went largely unremarked at the time. The first two questions related to The Last Mimzy, the children’s fantasy directed by Shaye, which was then being released to what proved to be disappointing box-office results. Inevitably, though, the interviewer switched to the Hobbit situation:

You recently said Peter Jackson would never touch The Hobbit while you were at New Line.

You know, we’re being sued right now, so I can’t comment on ongoing litigation. But I said some things publicly, and I’m sorry that I’ve lost a colleague and a friend.

Is The Hobbit still a viable project?

I can only say we’re going to do the best we can with it. I respect the fans a lot.

Shaye’s statements might be seen by some as implying that he regretted his rejection of Jackson as a director. Given that the vast majority of fans want Jackson to direct, the last sentence seems to offer hope that Shaye might relent and bow to their wishes.

A greater stir was caused by Entertainment Weekly’s April 16 announcement that Sam Raimi had expressed interest in directing The Hobbit—a possibility that had been circulating widely as a rumor since shortly after Shaye’s January pronouncement. As I suggested in my previous entry, however, most directors would shrink from upsetting Jackson and his fans by simply taking the job. Raimi made it clear what circumstances would be necessary: “First and foremost, those are Peter Jackson and Bob Shaye’s films. If Peter didn’t want to do it and Bob wanted me to do it—and they were both okay with me picking up the reins—that would be great. I love the book.” (Raimi presumably refers to films in the plural because MGM had suggested in September that it was considering a two-part adaptation.)

Raimi risked riling not only Rings fans but Spider-Man afficionados, who were upset at the idea that he might bow out of a presumed fourth entry in his own franchise. In the nearly two months since Raimi’s statement, there has been no public indication that he is being seriously courted to accept the job directing The Hobbit.

Jackson, however, has been busy. The projects on his plate have changed considerably since early October. Only a few weeks after my summary, Universal and Twentieth Century Fox, which had been on board to finance the video-game-to-film adaptation of Halo for co-production by Jackson and Microsoft, bowed out. The project is now on hold, with the assumption that the release of the Halo 3 game, announced for September 27, will regenerate studios’ interest.

The remake of The Dam Busters is moving forward, but it is being directed by Christian Rivers rather than Jackson, who serves as producer. The acquisition of Naomi Novik’s “Temeraire” series by Jackson and partner Fran Walsh, announced September 12, apparently has not resulted in a specific project. The pair presumably have the option of making it into a film at some future date or letting their option lapse.

The project that has made great progress is Jackson and Walsh’s adaptation of Alice Sebold’s bestseller The Lovely Bones. Their script was up for bids this spring, and on May 4, Variety announced its sale to Dreamworks. Reportedly the film will be delivered by the fourth quarter of 2008. It might be possible to commence pre-production work on a Hobbit film while The Lovely Bones is in progress.

Less than two weeks later, Variety revealed that Steven Spielberg is teaming with Jackson to produce three feature films based on the classic Belgian comic books starring Tintin. Each plans to direct one of the features, with a third director undertaking the other.

In October I suggested that most of Jackson’s projects were flexible in their timing, and that left the possibility that he could shift them around to fit in The Hobbit. Given that no timing has been announced for the Tintin films, Jackson’s only apparent project with a deadline is The Lovely Bones.

Finally, at the Cannes Film Festival, Shaye and co-president of New Line Michael Lynne spoke to Variety’s editor-in-chief, Peter Bart, about the Hobbit project. Their remarks might give Rings fans cause for hope.

Shaye maintained his stance, declaring that New Line had paid Jackson and Walsh $250 million in profit participation. “The clash happened because ‘one of us has gotten poor counsel,’ Shaye said, without elaborating.”

The story continues: “Co-chief Michael Lynne struck a more upbeat note. ‘We do want to settle our dispute and I think we will.’” Neither would comment on the rumors that Raimi was being wooed for the Hobbit adaptation. When asked about Raimi, Lynne replied, “There’s never been any announcement.” Shaye added, “Like a lot of people, he might.”

I think there are two major factors underlying this feud between Jackson and Shaye that haven’t been pointed out and need to be. First, lawsuits of the type Jackson brought are pretty common in Hollywood. Second, Shaye is perhaps forgetting the amount of personal investment and financial risk Jackson took to get Rings made—investments that cost New Line nothing but which brought in a hugely successful film on a surprisingly low budget. (I explain how in the first chapter of The Frodo Franchise.)

Jackson’s isn’t even the first suit against New Line by someone central to the film’s making. Independent producer Saul Zaentz sold the adaptation rights to Miramax back in 1997, and that company in turn sold them to New Line in 1998. As part of these deals, Zaentz was to receive 5% of gross international receipts. He sued, claiming that the $168 million paid to him was calculated on net receipts, leaving a balance of $20 million owed him. The suit was to come to court on July 19, 2005, but New Line settled for an undisclosed amount shortly before that. The same thing could happen in Jackson’s case, and the settlement could come at any time.

Zaentz isn’t the only other person claiming to have been shortchanged by New Line. On May 30 of this year, a group of fifteen Kiwi actors filed a suit claiming that they had not been paid the 5% of net merchandising revenues for products bearing their likenesses. (The group includes Sarah McLeod, who played Rosie Cotton, Craig Parker, who played Haldir, and Bruce Hopkins, who played Gamling.) The suit isn’t likely to reach court soon, if ever, but Jackson isn’t alone in his doubts about New Line’s accounting practices.

Moreover, Jackson and Walsh spent an enormous amount of their own money upgrading the filmmaking firms in Wellington to make them sophisticated enough to handle all phases of Rings’s production. Weta’s two halves, Digital and Workshop, of which the couple owns a third, were vastly enlarged. Jackson and Walsh bought the country’s only post-production facility, The Film Unit, when it was for sale and under threat to be moved out of New Zealand. They went into debt to do that, and it, too, was enlarged and moved into a huge facility full of highly sophisticated equipment. Much of this expansion was paid for with the money Jackson received for making Rings.

The result was a trio of films that grossed nearly $3 billion internationally, as well as untold additional revenues for the DVDs, video games, and other ancillaries. New Line went from a small subsidiary of Time Warner known mainly for its Nightmare on Elm Street series to a well-respected company making prestige films like Terence Malick’s The New World and the upcoming The Golden Compass, an adaptation of the first novel of Phillip Pullman’s award-winning trilogy. Oh, and there’s the matter of the seventeen Oscars Rings won. Previously New Line, founded in 1967, had won two.

In the wake of Rings, Jackson was faced with having to keep Weta, The Film Unit (now renamed Park Road Post), the Stone Street Studios, and his WingNut production firm going. Beyond the physical facilities, which no doubt involve enormous overhead costs, there are the many hundreds of employees to be paid. New Line did not invest in these facilities. Jackson and Walsh, along with their partners Richard Taylor and Jamie Selkirk, did.

When I first visited Wellington, there was a question as to whether there would be enough business to keep the facilities going and the employees in work. King Kong helped in the short run, but would other big films follow? Since then, Weta Workshop has diversified and is thriving. Weta Digital gets regular work doing the CGI for large numbers of shots in such films as X-Men 3: The Last Stand and Eragon. James Cameron’s decision to make Avatar in Jackson’s facilities seems the final seal of approval. Weta Digital is now widely considered one of the top digital effects houses in the world, alongside such firms as ILM, Sony’s Imageworks, and Rhythm & Hues.

Now the Wellington facilities all seem to be doing well. Nevertheless, in the era before Rings’s release and huge success, Jackson took as big a risk as Shaye did. Maybe bigger. Shaye might ponder that as he decides what to do about the Hobbit project. He owes the Kiwi filmmaker gratitude for more than simply directing a runaway hit.

Beyond that, unless New Line has short-changed Jackson very badly through its accounting procedures (and all that would presumably come out eventually when the suit finishes up), the added value provided by the director’s name on a Hobbit film would surely be at least as great as the money owed. Unless there is some major unknown factor influencing Shaye’s decision, he would do well to tamp his resentment, make peace, and initiate a project that is as close to a guaranteed mega-hit as anything can be these days. He could settle out of court, as he did with Zaentz, and just get on with it.

[Added July 21: For my update on the Hobbit film, go here.]

[Added August 6: For my earlier comments on the Hobbit film, go here and here.]

Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.

DB:

You’ve heard it before. Facing a summer packed with sequels, a journalist gets fed up. This time it’s Patrick Goldstein in the Los Angeles Times, and his lament strikes familiar chords. Sequels prove that Hollywood lacks imagination and is interested only in profits. Sequel films are boring and repetitious. They rarely match the original in quality. And when good directors sign on to do sequels, they get a big payday but they also compromise their talents.

Me, I want more original and plausible ideas. So, I expect, do you. Time to call in the Badger squad, the ensemble of email pals drawn from various generations of UW-Madison grad students and faculty. I asked them if we can’t understand sequels in a more thoughtful and sophisticated way—historically, artistically, in relation to other media. The result is another virtual roundtable, like the one on B-films held here a few months ago.

There were enough ideas for several blogs, and I’ve regretfully had to drop a whole thread devoted to comics and videogames. Maybe I’ll compile those remarks into a sequel. For now, the participants are: Stew Fyfe; Doug Gomery; Jason Mittell (of JustTV); Michael Newman (of Zigzigger and Fraktastic); Paul Ramaeker; and Jim Udden. I throw in some ideas as well.

Are all sequels in the arts automatically second-rate?

DB: The Odyssey is a sequel to the Iliad, and the second, better part of Don Quixote is a sequel to the first. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is explicitly a followup to The Hobbit. After killing off Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Final Problem,” Conan Doyle resurrected him for more exploits. The Merry Wives of Windsor brings back Sir John Falstaff after his death in Henry IV Part II, because, supposedly, Queen Elizabeth wanted to see him again, this time in a romance plot.

Michael Newman: Sequels exist in all narrative forms–novels, plays, movies, television, videogames, comics, operas. What is the Bible but a series of sequels? Didn’t Shakespeare follow up Henry IV with a part II? What of Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Updike’s Rabbit novels? Many novelists of high reputation have written sequels, including Thackeray, Trollope, Faulkner, and Roth. There is nothing intrinsically unimaginative about continuing a story from one text to another. Because narratives draw their basic materials from life, they can always go on, just as the world goes on. Endings are always, to an extent, arbitrary. Sequels exploit the affordance of narrative to continue.

What about film sequels? What’s their track record?

DB: Goldstein grants the excellence of Godfather II, but what about Aliens, The Empire Strikes Back, Toy Story 2, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (arguably the best entry in the franchise)? We have arthouse examples too, provided by Satyajit Ray (Aparajito and The World of Apu), Bergman (Saraband as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage), and Truffaut (the Antoine Doinel films). If we allow avant-garde sequels, we have James Benning‘s One-Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later. As for documentaries, what about Michael Moore’s Pets or Meat?, the pendant to Roger and Me?

The world of film would be a poorer place if critics had by fiat banned all the fine Hong Kong sequels, notably those spawned by Police Story, A Better Tomorrow, Drunken Master, Once Upon a Time in China, Swordsman, and so on up to Johnnie To’s Election 2 and Andrew Lau’s Infernal Affairs 2. And arthouse fave Wong Kar-wai hasn’t been shy about making sequels.

Stew Fyfe: Other sequels of quality: The Bride of Frankenstein, Mad Max II (The Road Warrior), Spider-Man 2, X-Men 2, Dawn of the Dead, Sanjuro, Quatermass and the Pit. Personally, I’d also add Blade 2, Babe 2 and The Devil’s Rejects, but I’m sure those are arguable. Would The Limey be a sequel to Poor Cow? Del Toro speaks of Pan’s Labyrinth as a companion piece or “sister-film” to The Devil’s Backbone. If you want to include docs, there’s always the Up series.

Why are there film sequels in the first place?

DB: Most film industries need to both standardize and differentiate their products. Audiences expect a new take on some familiar forms and materials. Sequels offer the possibility of recognizable repetition with controlled, sometimes intriguing, variation. This logic can be found in sequels in other media, which often respond to popular demand for the same again, but different. Remember Conan Doyle reluctantly bringing back Holmes, and Queen Elizabeth asking to see Sir John in love.

Doug Gomery: Sequels happen because the studio owners have never figured out any business model to predict success. If #1 is popular, perhaps #2 will be almost as popular. Until recently, producers seldom expected the followup’s revenues to equal the first. The basics were keep costs low, keep risks low, and make a profit. Maybe not a large as the breakthrough initial film—but at least a profit.

But they’re not a contemporary development. As part of the Hollywood studio system, they have existed in all eras—the Coming of Sound, the Classical Era, and the Lew Wasserman era. They surely seem to be surviving Wasserman as well. Indeed, as much as I admire Wasserman, who can defend Jaws 2 and its successors?

In the classic era, it may seem that there were fewer sequels as such, but there was a variant called rewrites in another genre. Years ago as I did my first book, a study of High Sierra, I watched Colorado Territory with something close to awe. It’s a gangster film turned western almost line by line. After all, Warners owned the literary rights: why not recycle it?

Given the mercenary impulse behind sequels, does a director’s willingness to make one mean that he or she has sold out?

Goldstein: “Look at the great talent who’s on the sequel beat: Steven Soderbergh has done two Ocean’s sequels. Bryan Singer, the wunderkind behind The Usual Suspects, has done X-Men 2 and is at work on a sequel to Superman Returns. Christopher Nolan has left behind the raw originality of Memento to do Batman movies. Robert Rodriguez, who burst on the scene with El Mariachi, has done two sequels for Spy Kids, with a Sin City sequel on its way. After making Darkman and A Simple Plan, Sam Raimi seemed poised to be our generation’s dark prince of meaty thrillers but has turned himself into an impersonal Spider-Man ringmaster instead.”

Paul Ramaeker: To assume that the Spider-Man films must necessarily be less personal than Darkman or A Simple Plan (both of which are heavily indebted to the strictures of their genres) is to perpetuate a culturally snobbish perspective on comic books. I’ve not seen S-M3, but Raimi is a genuine fan of the character, a character with a long and complex narrative history, and given the way S-M2 continues and develops threads from the first film, I see no reason to assume he didn’t have some artistic investment in presenting his interpretation of the character over 3 films (or however many) to present a larger “story” about the character. Why should this not be seen as “personal” filmmaking to the same extent as any other kind of adaptation?

Moreover, speaking as a Soderbergh fan: I may not like Ocean’s 12 as much as Ocean’s 11, but it seems like an experiment made in good faith to me. It is a stranger movie than you would think from the way it gets picked up in articles like Goldstein’s. In fact, the way it plays with audience expectations is both dependent upon familiarity with the first film, and radically divergent from it- in many ways, it does the exact opposite of what sequels are supposed to do, which is to provide a “cozy” (Goldstein’s word) repetition of familiar pleasures. Perhaps it failed (again, I remain sort of fond of the film, which I think was best described as being like an issue of Us Weekly as put together by the editors of Cahiers du cinéma), but even so I think you’d have to call it a failed experiment rather than a rehashing.

Stew Fyfe: At a guess, I’d say that audiences or critics might evaluate the worthiness/mercenary nature of sequels by asking three questions:

(1) Has the sequel been made because there’s more story to tell?

(2) Has the sequel been made because the characters are great and people want to see them again?

(3) Has the sequel been made because there’s more money to be made?

Obviously, any combination of all three can be answered in the affirmative for any sequel and presumably the sequel wouldn’t get made if the answer to (3) was No. But with something like The Two Towers, (1) gets priority, while with Pirates 2 + 3, (3) nudges out (2). Even with (3), money, as the primary motivation, one could still make a good film. The suspicion of milking the franchise just makes the movie an easier target for critics.

Do sequels automatically equal predictability?

Jason Mittell: The line that most interests me in Goldstein’s piece is the last: “When it comes to entertainment, I’ll take excitement and unpredictability over familiarity every time.” This sets up a false dichotomy between the known and the unknown. As David and I both blogged about a few months ago, knowing a story doesn’t preclude suspense and excitement (and for some viewers, it might actually enhance it). And arguably knowing a storyworld actually allows for greater opportunities for excitement and unpredictability – a film/episode/entry in any series that doesn’t need to spend much time introducing already-established settings, characters, conflicts, etc. can literally cut to the chase. Think of the second Bourne film as a good example, or Spider-man 2 as a chance to deepen character once basic exposition is accounted for.

Paul Ramaeker: I have a theory. In the contemporary comic-book blockbuster, the sequels will always be better than the first entries. Spider-Man 2 is better than Spider-Man, X-Men 2 is better than X-Men, and I will bet that The Dark Knight will be better than Batman Begins, just as Batman Returns was better than Batman. The pattern seems to me to be that the first film in the series is relatively impersonal—the franchise must be established as a franchise, meaning that few boats will be rocked, and the director must prove that they can handle both a film on that scale, and can be trusted with the property with all the investment it represents.

But once they’ve done so, in the above cases where the first films enjoyed significant economic (and critical) success, the directors are given a bit more leeway, are allowed to drive the family car a little further and a little faster. In each case, the second film in the series by the same director has been significantly more idiosyncratic. Batman Returns has much more of Burton‘s sense of humor and interest in the grotesque; X-Men 2 is a much more serious and ambitious film narratively and thematically, more obviously the product of a prestige filmmaker (Singer’s never been an auteur by any stretch, so that will have to do). Spider-Man seemed sort of anonymous in terms of style, but Spider-Man 2 had a much more extensive and playful use of classic Raimi techniques: short, fast zooms; canted angles; rapid camera movements; whimsical motivations for techniques, like the mechanical-tentacle POV shot (virtually a repeat of his flying-eyeball POV from Evil Dead 2).

Who knows what The Dark Knight will be like, but I’m prepared to put money on the claim that it will have something to do with how people construct elaborate narratives around themselves to explain, justify, or obscure their actions and motives.

Are sequels part of a larger trend toward serial narrative?

DB: We can continue a story in another text within the same medium, but we can also spread the storyline across many platforms—novels, films, comic books, videogames. Henry Jenkins has called this process transmedia storytelling.

Michael Newman: Compared with literary fiction, there seems to be a strong propensity toward the never-ending story in genre storytelling like sci-fi and fantasy and superhero comics and spy novels and soap operas. Much of the cinematic sequel storytelling today might be considered as this kind of serialized genre storytelling. Such serials tend to have a low aesthetic reputation in comparison to more respectable genres. (The cinematic comparison would be summer blockbusters vs. fall Oscar bait.) Serial forms have historically been associated with children (e.g., comic books) and women (e.g., soaps). In other words, there is cultural distinction, a system of social hierarchy, at play.

Stew Fyfe: Yes, the longer-standing comics universes have made regular use of serial continuity to forge after-the-fact connections. It’s a form of what fans call retcon or “retroactive continuity.”

Sci-fi writer Phillip Jose Farmer used a similar concept, the “Wold Newton family” to link various mystery, pulp, crime, sci fi, adventure and spy fiction characters (so that Sherlock Holmes, Doc Savage, Sam Spade, The Shadow, Captain Blood and James Bond, among others, all become linked). Alan Moore did something similar with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and Warren Ellis in Planetary. More limited filmic examples of this might be Zatoichi vs. Yojimbo, or Enemy of the State (which more or less sticks The Conversation‘s Harry Caul into a Bruckheimer film). There’s Freddy vs. Jason, which very adroitly observes and incorporates the continuities of two long-standing, mostly dormant franchises. In television, there’s that whole, rather insane St. Elsewhere continuity thing.

In the current crop of movie sequels featuring superheroes, one thing that has been noticeable is the casting of minor characters who might serve as springboards for later storylines. We’ve seen Dylan Baker play Dr. Connors in two Spidey films, for example, so if they decide to go with The Lizard as a villain in one of the later films, they’ve already set him within the film series’ continuity. Aaron Eckhart’s casting as Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight could similarly be used to set up Two Face as a villain for film 3.

This is similar to the idea of leaving a film “open for a sequel,” but it seems more closely integrated into the planning and execution of the film. It also points to a middle ground between the “We’re going into this making three unified films” model (Lord of the Rings) and the “We can make more money, so let’s see what plot elements we can build off of” (Pirates of the Caribbean). This is more of a “We’re probably going to make more films, let’s give ourselves something to work with” model.

It also raises the question, I guess, if you want to start speaking of dangling causes extending past the end of a film, or in the case of Pirates, the conversion of plot elements into something like dangling causes. In Pirates 1, we hear of Bootstrap Bill Turner getting chained to a cannonball and shot out into the ocean, but wasn’t it after he was made immortal by the curse of the Aztec gold? I guess you could call this a retroactive cause. Or, noting the similarity to “retcon,” a “retcause.” Never mind, that sounds lame.

Michael Newman: In the contemporary era of media convergence, serialized storytelling is becoming a mainstay across media and genres. Serial narratives supposedly facilitate spreading franchises out across multiple platforms. The media franchise demands long-format storytelling that can be spun off in multiple iterations. The rise of sequels is a much larger issue than a bunch of directors trying to make lots of money or audiences having unadventurous tastes–sequel/serial franchises are a central business model in the media industry today, supported and encouraged by the structure of conglomeration and horizontal integration.

The real point of the LAT article is that Hollywood is all commerce and no art, and sequels are a symptom. But this is such old news. And to connect it to a Squeeze summer tour is really stretching.

Jason Mittell: I think Michael’s cross-media point is crucial – continuity of a narrative world is a core part of nearly every storytelling form, but the language of “sequel” is applied predominantly to film. “Series” seems a more respectable term, as it suggests an organic continuity rather than a reactive stance of “Hey, let’s do that again!”

Are some serial/ sequel forms better suited to different media?

Jason Mittell: I think the LAT article is ultimately trying to valorize cinema’s potential to introduce something new, in reaction to the presumed rise of legitimate and praised series narratives on television (The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, Lost, etc.). And perhaps he has a point. Maybe film should stick to presenting compelling stand-alone short stories, since television has emerged as the leader in narrating persistent worlds? Or maybe I’m just saying that to pick a fight…

Jim Udden: I disagree that films should stick with one-off feature-length productions and leave ongoing series work to TV. Television has long had its Made for TV Movies, so why shouldn’t cinema think more in terms of series than it does? After all, if these are truly hard times for the film industry, as we’re always told, doesn’t it make more economic sense to adapt, just as TV has done in the last couple of decades?

True, there are things that cannot be matched on either side. I cannot imagine any film ever matching the daunting complexity of Deadwood or The Wire. Then again, some things work best as a stand-alone concern. Try to imagine a sequel to Pan’s Labyrinth or Children of Men, or try to imagine either film being made only for TV, for that matter. Moreover, some sequels should never be made. (Remember 2010?) On the other hand, some films would have been better off had they been pitched as an HBO series. (Syriana comes to mind.)

Yet film has proven its ability to take on a series format even when it is not called that. In a sense the oeuvres of most of the great art cinema auteurs are series of sorts. Aren’t Tati’s films a series with the ongoing presence of Hulot (or Hulots, if we include the false ones in Play Time)? And does anybody castigate Wong Kar-wai for following up Chungking Express with Fallen Angels, or In the Mood for Love with 2046, which are not series, but mere (gasp!) sequels? Clearly these examples were based not just on aesthetic visions, but on banking on previous success. Why do we give them a pass, but not more mainstream fare?

I think the more closely we look, the more we might find there are series and sequels even if they are not tagged by those names. It does happen in documentary, and not just in the 7 Up series. For example, American Dream does seem to me to a continuation of Harlan County USA, if not an outright sequel. Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 combined make for a more complex argument about the relation of the defense industry to class issues than each one does on its own.

In other words, none of these formats has any value on its own. Everything depends on the type of stories to be told and the talent and economic wherewithal to find the best format for that story (or argument). The most appropriate format could be just a two-hour film, or it could be a television series going on for years. Or it could be something in between, such as the first two Infernal Affairs films, which got clumsily condensed into one film in The Departed. Both television and film can equally participate in such in-between formats.

DB: I don’t agree with all of these arguments and opinions, and I don’t expect you to either. The point is that compared to journalists’ rote dismissal of sequels, these writers offer more stimulating and more probing arguments. These guys are researchers and teachers, and they offer detailed evidence for their claim. They also write clearly, a point to remember when people say that film academics always talk in jargon and pontificate about gaseous theories.

To end on an upbeat note, I note that some journalists avoid the conventional wisdom. Consider Manohla Dargis’ recent and welcome defense of the blockbuster. Her case doesn’t seem to me spanking new: the artistic possibilities of the format have been defended for several years by film historians, as well in Tom Shone’s lively 2004 book Blockbuster. (1) Still, in the pages of the good, gray Times, Dargis’s piece remains something of a breakthrough. Maybe some day the paper will host a defense of sequels as well. If so, consider this communal blog a prequel.

(1) A sample, with Shone responding to the charge that the ’70s blockbuster drove out ambitious American filmmaking: “Any revolution that left it difficult for Robert Redford to make a movie as self-importantly glum as Ordinary People can be no bad thing” (Blockbuster, 312).

PS 30 June: Jason Mittell continues the conversation by contesting another journo’s claim that the public is tiring of sequels this summer.