Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

New media and old storytelling

DB asks: To what extent has the DVD changed viewing habits and movie storytelling?

As everybody knows, a DVD offers more interactivity than a movie you watch in a multiplex. In a theatre, the movie rolls on, unaffected by anything you may do. But with a DVD you can pause the film, run fast forward, skip to a particular second, shuffle chapters, even play the thing in reverse.

Most minimally, the DVD offers greater convenience. You can halt the film so you can answer a phone call or zip back to replay a bit you might have missed. But some of us wonder if this new interactivity harbors more radical implications. Does the new flexibility of use allow us to experience the film in new ways?

In a mystery film, say there’s a clue at the half-hour mark. In a theatrical screening, we’re pressed forward with no time to ponder it. Watching the film on DVD lets us halt the film, ponder the clue as long as we like, and maybe track patiently back to earlier scenes to test our suspicions about what that clue means. Or suppose you decide to sample the film, browsing through the opening bits of several chapters? More radically, suppose we decide to watch the DVD in reverse? Nothing stops us, and we’d have an experience of the story very different from that of someone who watched the film in the normal order. Doesn’t this all suggest that it’s hard to generalize about what the “ordinary” viewer’s experience of a movie might be nowadays?

Now consider the craft of fictional filmmaking. The movie’s creators make choices about what story information to impart, when to impart it, and how to impart it. They assume that the viewer follows the story in the order mandated by theatrical projection, scene 1, then 2, 3 and onward. Likewise, the pace of uptake is set by the film—no slowing down or speeding up at the viewer’s will. But given the new conditions of digital consumption, these assumptions may be wrong. So shouldn’t the filmmakers take those conditions into account? And more specifically, haven’t some filmmakers already taken them into account? In other words, hasn’t the DVD transformed cinematic storytelling?

This question is important to me. I’ve long argued, along with Kristin, that mainstream US filmmaking, dubbed long ago “classical Hollywood cinema,” has cultivated a sturdy and pervasive tradition of storytelling. (1) That tradition depends on clearly defined characters pursuing well-defined goals. This commitment in turn creates a plot that displays linear cause and effect: In pursuing goals, the protagonist makes one thing happen, and that makes something else happen, which in turn triggers something else. Moreover, the mainstream tradition lays these actions and reactions along a fairly rigid structural layout. And this tradition depends on a system of narration that constantly reiterates the characters’ traits, their goals, important motifs, and the overall circumstances of the action. This is a fairly abstract description, I know; go to my analysis of Mission: Impossible III for a specific example of how the system can work.

But now home video allows our consumption to be highly nonlinear. By skipping or skimming DVD chapters, we may not register the plot or narration as the makers intended. Doesn’t this make hash of goal-directed action, character arcs, and all the other features of classical storytelling? Might we not be moving toward a “post-classical” cinema?

Movie as book

Let’s tackle the question first from the standpoint of the viewer. I think we can get help by recognizing this basic point: The DVD made a movie more like a book.

This sounds odd, because we think of digital media as replacing print. Yet consider the similarities. You can read a book any way you please, skimming or skipping, forward or backward. You can read the chapters, or even the sentences, in any order you choose. You can dwell on a particular page, paragraph, or phrase for as long as you like. You can go back and reread passages you’ve read before, and you can jump ahead to the ending. You can put the book down at a particular point and return to it an hour or a year later; the bookmark is the ultimate pause command.

We tacitly acknowledge the resemblance between the DVD and the book when we call the segments on a DVD its chapters, the list of chapters an index, and the process of composing the DVD its authoring.

With these similarities in mind, we can ask: How many people, on first contact, would sit down to watch a film in a nonlinear way?

My hunch: Just about as many who would buy or borrow a book and then proceed to read it in a nonlinear way. Now we can grant that if you have a nonfiction book in hand, you might pick out certain chapters as more interesting than others and move straight to those. Similarly, with a DVD documentary on penguins, some viewers might want to move straight to the chapter labeled Mating Habits.

With a fictional film, though, we’re much less inclined to graze and browse, just as with a novel. True, we might sample the novel before buying or borrowing it, but I’d bet the portion we’re most likely to sample is the opening chapter. With a fiction film on DVD, some viewers might skip to a chapter opening or two, but I expect that soon they’d settle down to watching the show at the order and pace of a theatrical screening. This is more or less what happens with literary fiction. The person who starts a novel will proceed in linear order in order to follow the story. It’s a revealing phrase: we’re following a path laid down for us, not racing ahead or falling back.

This isn’t to say that all consumers of fiction move at the same pace or read the same way. I’m just indicating that following the mandated order, page by page or shot by shot, is the default that people adhere to in the overwhelming majority of cases.

This suggests that pausing is the most common way we play an interactive role. When reading a book you might call out to your friend and reread a particularly striking description or funny dialogue exchange. When watching a film, you might stop and replay some images to enjoy them again. Another common act is probably quickly “paging back”—rereading or re-viewing a bit that just preceded the pause to remind ourselves of what’s going on at the moment.

Our purpose in starting a book or film at the beginning is to get into the story world and start to think and feel in relation to the information we get about it. But we don’t have to take that as our primary purpose. More extreme acts of “creative” spectatorship are tied to different purposes than learning about the story world. I suppose that teenage boys might well rent 300 when it comes out on DVD and fast-forward looking only for the scenes showing carnage or naked ladies….the same way that my high-school contemporaries rummaged through Terry Southern’s Candy digging out the good parts. (2) But this doesn’t seem to be a radically new way of using any medium, because the purpose—scanning a text for immediate gratification rather than narrative involvement—was common well before DVD.

Of course we students of cinema use the DVD commands in order to study a film, spooling back and forth to analyze it. But that usage isn’t a radical reworking of consumption either. Typically before we start to analyze a movie, we’ve already experienced it in the ordinary beginning-to-end way. Students of literature execute the same sort of back-and-forth moves studying a text that they’ve read before.

Finally, I’d suggest that a highly unorthodox mode of consumption, like setting out to watch a film in reverse at 8x speed, would become quite boring fast. As with so many things in life, just because you can do something doesn’t mean you’d enjoy it.

Speculation 1: The actual uses that people make of DVD interactivity are limited; traditional beginning-to-end consumption is the default.

Speculation 2: Pausing, paging back, and scanning for the good bits suggest that the most frequent DVD interactivity is familiar from other media, particularly books.

Guided interactivity

Let’s now consider things from the side of the creators. Knowing that films are seen on DVD, don’t filmmakers adjust their art and craft to this new medium? Of course they can provide revised versions, or directors’ cuts, along with alternative endings, deleted scenes, and other material that shed light on the film and the production process. But does the DVD format change the very act of conceiving and executing the story presented by the film?

Yes, in certain respects. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that the possibility of rewatching a film with little fuss encourages ambitious filmmakers to “load every rift with ore,” to pack in details that might not be noticed on a single viewing. One of my examples is the 8/2 motif in Magnolia. Likewise, the looping plotlines of Donnie Darko and the reverse-order one of Memento are amenable to being picked apart after several viewings. But before home video, you as a viewer could scrutinize such movies by just going back to the theatre and watching the film over and over, very attentively.

Clumsy as it seems, film nerds of my generation did this. I remember my thrill as a junior in college when I discovered, after rerunning a 16mm print of Citizen Kane on my apartment wall, the snowstorm paperweight that Kane clutches on his deathbed sitting on Susan’s vanity table the night he first meets her. Welles had, as it were, planted this clue for attentive viewers to spot. When we were lucky, we might get a film on a flatbed viewer and go through it reel by reel. Granted, the random-access aspect of DVD allows this sort of micro-analysis to be done much more easily, but it’s not different in kind from rolling up your sleeves and threading up a Films Incorporated print one more time.

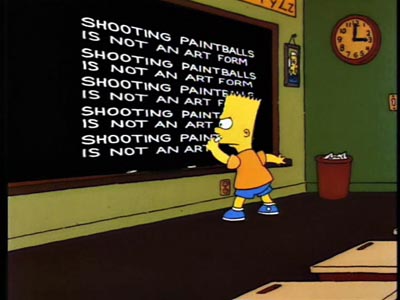

I’d add that this sort of scrutiny enriches the film in a very traditional way. Films that sustain this sort of attention, from Buster Keaton silent movies to Hiroshima mon amour and The Silence of the Lambs, long predate the arrival of DVD. Throughout Play Time Tati sprinkled details and gags that reward many viewings. When Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan bury details in their films, or when The Simpsons flashes a jokey sign past us, they’re practicing a time-honored strategy of teasing the viewer to return to the work to get something more out of it. Having the DVD at your disposal makes it easier to find half-hidden motifs, jokes, ironies, and the like, but all of these are traditional elements of films both classical and non-classical.

There are, though, more radical cases. The experimental novelist Michel Butor pointed out that the fact that the book is an object to be manipulated at will harbored the possibilities of innovative storytelling. He pursued those in works like La Modification (1957) and Degrés (1960) and theorized about them in an essay, “The Book as Object.” (3) Along the same lines, once a film becomes a booklike object, it can be composed to encourage multiple replays not merely to appreciate little touches but just to make bare sense of what’s going on in it.

Memento and Primer would seem to be instances. Their makers seem to have designed the films to encourage admirers’ extensive, not to say obsessive, re-viewings. (For analyses of Primer, go here and here.) Again, however, the DVD serves not as a unique format for the film but as a tool that makes analyzing the plots a lot easier than would several visits to the theatre. (4)

There are other possibilities tied to the format itself. The DVD of Max Allan Collins’ Real Time: Siege at Lucas Street Market was designed to permit the viewer some choice of camera angle in certain scenes. At a few points we’re permitted to enlarge the monitors of different surveillance cameras in order to follow one or another strand of action. (Actually, I couldn’t get this feature to work on my players.) Still, in Real Time, the plot action is clear and redundant in the classical manner, so even if you don’t enlarge the screens, maybe you won’t miss much.

Butor suggested that since a book is an object, all in hand at once, a plot could be composed to permit many, equally valid points of entry and exit. Such seems to have been achieved by the DVD version of Greg Marcks’ 11:14. The film is a network narrative, following five characters in a small town as their lives intertwine. The plot is broken into five segments, each one following a character up to the critical moment given in the title. It’s a clever and enjoyable piece of work. In carrying it to DVD, Marcks chaptered it so that you could skip among storylines at will. He explains in an email to me:

It’s a feature on the DVD that I called “character jump,” which allows you to jump to what another character is doing at that same moment in time. Theoretically you could watch the film in an endless circuitous loop because the end is simultaneous with the beginning.

During some scenes of 11:14, a JUMP icon appears and if you press Enter, the scene switches to another character’s storyline—either earlier or later in the theatrical version’s running time. Once in that story, the icon stays on for a bit so that you can return to your point of departure if you want. (4) Presumably for reasons of engineering and disc space, the number of JUMP options remains fairly limited. Still, it’s a fascinating prospect, and it does seem to offer the possibility of your restructuring the plot in fresh ways.

Even in 11:14, however, the story possibilities are closed. As in a Choose Your Own Adventure book, you’re hopping among trajectories that are already designed. The opening remains the opening for every option; no Butor-style starting in the middle. Furthermore, the trajectories themselves are linear, running along a cause-effect pattern very familiar to us from classically constructed stories. (5) We find this often in branching or multiple-draft narratives. I argue in The Way that even the reverse-order disjunctions of Memento sort out along lines to be found in film noir.

Let’s also recall a simple point. Even though the book format offers the sort of mind-bending manipulations Butor celebrates, most literary fiction remains traditionally plotted and narrated. Likewise, we should expect that the arrival of the DVD permits filmmakers who want to tell orthodox stories in orthodox ways keep on doing so. The line of least resistance is straightforward linear presentation.

Speculation 3: The ease of DVD replay can encourage filmmakers to pack their films with more details that repay rewatching. The result might be films that are more “hyperclassical,” to use a term I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It –films that are even more tightly woven than we tend to find in the studio years.

Speculation 4: Some filmmakers have made their storylines harder to follow on a single viewing, encouraging DVD replays so we can figure out what’s going on. This strategy makes the films less classical in construction, to a greater or lesser extent.

Speculation 5: A few filmmakers have utilized DVD features to allow greater interactivity than a theatrical screening would grant. In most cases, however, this interactivity rests upon classical guidelines—protagonists with goals, confronting obstacles, conflicting with others, and arriving at a definite conclusion along a linear path.

A stubborn structure

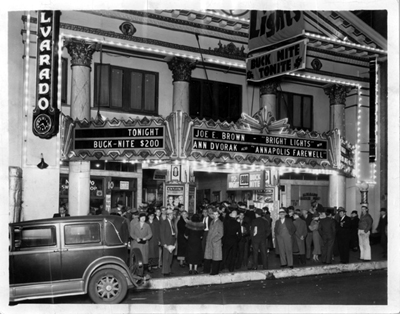

Once upon a time, roughly between the 1920s and the 1960s, movie theatres had a policy of continuous admissions. Metropolitan theatres were sometimes very crowded and patrons had to wait in line outside for seats to be freed up. (Hence the need for ushers to find vacant seats during the screening.) As a result, you might enter in the middle of the movie and watch the film through to the end, sit through shorts and perhaps another feature, and then stay for the opening of the initial film. Hence the expression “This is where we came in.” Doubtless many people planned to see films from beginning to end, but a lot also arrived in medias res.

Someone might speculate that this manner of viewing would encourage filmmakers to indulge in slack plotting. After all, if viewers can come in at any point, a vaudeville-like cascade of acts and incidents—what people are now calling a “cinema of attractions”—would be best. In fact, however, Hollywood feature filmmakers told complex, linear stories of the sort I’ve already mentioned. They didn’t seem to care if viewers were entering midway.

But they really had no choice. If the filmmakers wanted to tell a fairly coherent story, how could they cater to a viewer who might enter at any moment? The only feasible plan, then and now, is just to go ahead and present a story in the linear way, but make sure that it’s presented so clearly that even a viewer entering in the middle can pick up what’s happening. That was, and still is, the default practice. The redundancy of Hollywood storytelling, bent on clear and cogent presentation of the action, is the most effective response to fragmentary viewing.

Hollywood films have been shown in picture palaces, rural playhouses, college classrooms, churches, military bases, and submarines. They’ve appeared on TV, in drive-in theatres, on airline screens, on computer monitors, and now on iPods. In design and execution, the films have stayed remarkably stable. They have relied on our understanding of general principles of storytelling and more specific ones typical of Hollywood. In most cases, this default will stay in place. It works very well, and there’s no alternative that can anticipate all the different ways in which viewers can consume the movie.

Speculation 6: Odd as it sounds, fragmented viewing conditions can encourage coherent storytelling.

Speculation 7: We can’t easily draw conclusions about how films are constructed on the basis of how they’re presented and consumed. Changes in viewing practices don’t automatically entail changes in storytelling.

I’d just add that even in the age of digital media, spectators enjoy greatest freedom not in the way that they manipulate films but in the ways they can interpret them. But even an epic blog has to stop somewhere, so I’ll leave that matter for another time. (6)

(1) You can find the details of our case in Film Art, in Narration in the Fiction Film, in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, in Storytelling in Film and Television, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, and in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema. Also, see Kristin’s “contrarian” blog entry here.

(2) In high school I loaned Candy to a friend and it made its way among my peers with remarkable speed. When I got it back, the pages were falling out. Somehow, our principal Mr. Brown learned that I was the culprit. He gave me a starchy lecture and announced over the homeroom PA system that I was being reprimanded for “bringing a certain book” to school. Mr. Brown was unmoved by my defense that Candy had gotten fairly good reviews.

(3) Translated in his English-language collection Inventory (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), pp 39-56. The essay doesn’t seem to be available on the Net. So off to the library with you!

(4) Thanks to Colin Burnett, who tested the 11:14 DVD for me while I’ve been away.

(5) Marcks’ DVD version has allowed us to create a Griffith-style crosscutting of plot strands. Interestingly, network narratives are constructed in two main ways: crosscutting the storylines (as in SHORT CUTS) or presenting them in blocks that we must synchronize in our heads (as in PULP FICTION and GO). Marks’ theatrical version gives us the block version of 11:14, while the DVD reveals one possibility of an intercut one.

(6) I’ve discussed film interpretation in a book (Making Meaning) and in chunks of a forthcoming collection (Poetics of Cinema),

PS, 16 May (New Zealand time): Jason Mittell has a fascinating commentary on this topic at his site, Just TV (which isn’t actually just about TV). Jason argues that television narrative has become more complex in recent years and that videotape and DVD technologies have affected that in some unexpected ways. A must-read!

But what kind of art?

2046.

From DB:

We don’t have to think of film as an art form. A historian can treat a movie as a document of its time and place. A war buff could scrutinize Eastwood’s Iwo Jima movies for their accuracy, and a chess expert could sieve through Looking for Bobby Fischer to discover, move by move, what matches were dramatized. But most of the time we assume that cinema is an art of some sort.

Not necessarily high art. Cinema is often a popular art, or in Noël Carroll’s phrase, a mass art. From this angle, there’s no split between art and entertainment. Popular songs are undeniably music, and best-selling novels are instances of literature. Similarly, megaplex movies are as much a part of the art of film as are the most esoteric experiments. Whether those movies, or the experiments, are good cinema is another story, but cinema they remain.

So, at least, is our position in Film Art: An Introduction. We draw our examples from documentaries, animated films, avant-garde films, mainstream entertainment vehicles, and films aimed at narrower audiences. In other writing, Kristin has done research on high-art movements like German Expressionism and Soviet Montage (she wrote her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible), but she’s also written about popular cinema from Doug Fairbanks to The Lord of the Rings. I’ve indulged my admiration for Hou and Dreyer but also I’ve tried to tease out the aesthetics of Hong Kong action pictures and contemporary Hollywood blockbusters. Ozu gives us the best of both worlds: one of cinema’s most accomplished artists, he was also a popular commercial filmmaker.

Still, people who look upon cinema as an art don’t necessarily share the same conceptions of what kind of art it is. We have different conceptions of cinema’s artistic dimensions, and we won’t find unanimity of opinion among filmmakers, critics, academics, or audiences.

When we study film theory, this sort of question comes to the fore, and so today’s blog will be a bit more theoretical than most. Don’t let that scare you off, though; I’m trying for clarity, not murk.

Dimensions

People have tended to think of cinema as an art by means of rough analogies to the other arts. After all, film came along at a point when virtually all the other arts had been around for milennia. It’s commonly said that film is the only artform whose historical origins we can determine. So it’s been natural for people to compare this new medium with older arts.

Here are the dimensions that come to my mind:

*Film is a photographic art.

*Film is a narrative art.

*Film is a performing art.

*Film is a pictorial art.

*Film is an audiovisual art.

Let me say off the bat that I think that film is a synthetic medium, in the sense that all these features and more can be found in it. It’s like opera, which is at once narrative, performative, musical, and even pictorial. I mark out these dimensions simply to show some emphases in people’s thinking about cinema. As we’ll see, these ideas can be mixed together in various ways.

Film as a photographic art.

La petite fille et son chat (1900).

For many early filmmakers, such as the Lumière brothers (above), cinema was a means of capturing reality, documenting the visible world. Movies were moving photographs. Naturally, this conception of cinema leads us to treat documentary as the central mode of filmmaking.

It’s an appealing idea. G.W. Bush reading “My Pet Goat” wouldn’t be as revelatory presented as a painting or a theatre performance. On film we can see the event as it occurred and judge it as if we were in the same room. Even in fictional cinema, you can argue, the physicality of the actors, the tangibility of the setting, and the details–a train’s pistons, wind rustling through grass–could not be rendered, or even imagined, so powerfully in a non-photographic medium. In addition, consider Jackie Chan. His stunts are astonishing partly because we know he really did them and the camera photographed them. In an animated film, or a CGI-based one, a character’s acrobatics or brushes with death aren’t so thrilling.

The great film theorist André Bazin claimed that cinema’s photographic basis made it very different from the more traditional arts. By recording the world in all its immediacy, giving us slices of actual space and true duration, film puts us in a position to discover our link to primordial experience. Other arts rely on conventions, Bazin thought, but cinema goes beyond convention to reacquaint us with the concrete reality that surrounds us but that we seldom notice.

I think that Bazin’s idea lies behind our sense that long takes and a static camera are putting us in touch with reality and inviting us to notice details that we usually overlook in everyday life. (I try out this line of argument in relation to the tactility of Sátántangó here.) Moreover, you can argue that in treating cinema as a photographic art the filmmaker surrenders a degree of control over what we see and how we see it. Bazin made this claim about the Italian neorealists and Jean Renoir: creation becomes a matter of an existential collaboration between humans and the concrete world around us.

An example I used in my book Figures Traced in Light pertains to a moment in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Summer at Grandfather’s, when a tiny toy fan falls between railroad tracks as a locomotive roars past. The fan’s blades stop, then spin in the opposite direction as the train thunders over it. The blades reverse again when the train has gone. (This detail might not be visible on video.) Did Hou know how the fan would behave? Isn’t it just as likely he simply discovered it after the fact, making his shot a kind of experiment in the behavior of things? Conceived as a species of photography, cinema can yield visual discoveries that no other art can.

Interestingly, cinema didn’t have to be photographic. Many early experiments with moving images were made with strips of drawings, such as the Belgian Émile Reynaud’s Praxinoscope. You can argue that recording glimpses of the world photographically simply proved to be the easiest way to obtain a long string of slightly different images that could generate the illusion of movement. Some filmmakers, such as George Lucas, hold that filmmakers are no longer tied to photography, and that the digital revolution will allow cinema to finally realize itself as a painterly art. More on that below.

Film as a narrative art.

Rope.

This is at the core of Hollywood’s explicit concerns. Producers, directors, crew, and of course screenwriters will agree that Without a good story, the movie fails. Our Indie and Indiewood filmmakers say they’re trying to find fresh stories, the ones that “haven’t been told yet.” Overseas filmmakers dominated by Hollywood tell us, “We have our own stories to tell.” Even the most celebrated arthouse filmmakers often say they’re interested in character as revealed through action. Resnais, Rivette, Fassbinder, Haneke, and all the rest may have told unusual stories, but still they told ’em.

Likewise, many viewers will say that they go to the movies to experience a story. Reviewers online and in the popular press, if they do nothing else, are obliged to sketch out the film’s plot, though they mustn’t give away the ending. Even in academia, most discussions of films focus on what happens in the narrative.

When we consider film genres, we’re usually concentrating on the narrative aspects of them. Most genres display typical characters and plot patterns. The backstage musical features aging stars and young hopefuls, caught up in the process of putting on a show. The horror film typically centers on a monster’s attack on humans, who must fight back. One type of science fiction shows us an overweening scientist striving to go beyond “what is proper for humans to know.” Both fans and scholars discuss other aspects of genre films, but narrative is often central to their concerns.

Historians have traced in great detail how filmmakers employed cinema as a narrative art, but we’re making more discoveries all the time. How, for instance, have films signaled flashbacks? How do they let us know we’re in a character’s mind, or attached to his or her optical point of view? How have they structured their plots? Can we pick out distinct approaches to narrative–in various periods, or genres, or national cinemas? How have narrative conventions changed over the years? Some of the answers Kristin and I have proposed can be found elsewhere on this site, and in our books and articles.

Film as a performing art.

The Marrying Kind.

In the West, since Plato and Aristotle we’ve distinguished between verbal storytelling and dramatic presentation, or performance. Films may be stories, but they’re not exactly told: they’re enacted. At Oscar time, we’re especially conscious of this analogy, for the Actor/ Actress nominees usually garner the most public attention.

Hollywood acknowledged cinema as a performing art in the 1910s, when it created the star system. The Star reminds us that film acting isn’t exactly the same as theatre acting, since an elusive charisma puts the performance across. John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Keanu Reeves, and many other “axioms of the cinema” aren’t good actors by stagebound standards, but once they show up on screen, you can’t take your eyes off them. This notion intersects with the photographic premise: we say that the camera seems to love them.

You can argue that Andy Warhol revamped this idea. His superstars weren’t photogenic by ordinary standards but their almost clinical narcissism and exhibitionism, captured by the camera, made them as mesmerizing as any matinee idols. Warhol films like Paul Swann create rather disturbing emotions by putting us in the presence of an awkward performer.

Reviewers place a premium on a movie’s performance dimension. After they’ve told us a bit of the plot , they appraise the job the actors did. Some ambitious critics have written wonderful appreciative essays on acting, as in Andrew Sarris’s “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet” and the collection OK You Mugs. See also the two collections of articles by Gary Giddins, which I discuss in an earlier blog.

Academic film studies has been slow to study acting systematically, partly because of a bias against considering cinema as a theatrical art, and partly because acting is very hard to analyze. But Charles Affron, Jim Naremore, Roberta Pearson, and Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have greatly helped us understand performance practices. They show, among other things, that it isn’t just a matter of the face or the voice: a fluttered hand or a willowy stance can be as powerful as a frown or a line reading.

Film as a pictorial art.

Ohayu (Good Morning).

Progressive opinion in the silent era tended to deny that film was a performing art, since that would make it a form of theatre. No, film had unique capacities. Cinema was essentially moving pictures.

It was a visual art that unfolded in time, so a movie was neither quite the same as a painting (frozen in time) or as a stage play (not pictures but three-dimensional reality). The coming of sound somewhat reduced the appeal of this line of argument, but to a very great extent, students of film technique still emphasize cinema as a visual art.

Theorists argued that the film frame was a pictorial field, not a proscenium stage. Action unfolded in the frame in ways that dynamized space. The choice of angle, camera distance, camera movement, and the like created a visual fluidity that had no equivalent on stage or in other graphic arts. Even cinematic staging was quite different from blocking in a theatrical space. Add to this the ability to join one strip of pictures to another via editing, and we have a unique pictorial artform.

The theorists of the silent era, like Rudolf Arnheim and the Russian montagists, gave us a vocabulary and an orientation to studying visual style, but their legacy hasn’t been fully developed. Journalistic reviewers typically don’t pay that much attention to the way movies look. Nor, surprisingly, do academics. Film studies departments seldom pursue research into visual style and structure.

Here the professors are out of sync with the people whose work they study. Manuals and film schools teach composition, lighting, cutting, camera placement and the like. Professional filmmakers all over the world often think in pictures; they prepare shot lists and storyboards and care very much about the color values and editing patterns of the finished work. We can see their interest in visuals in DVD commentaries and supplements, and as viewers start to absorb bonus materials, perhaps their interest will be whetted too.

Needless to say, a number of avant-garde filmmakers, from Viking Eggeling and Walter Ruttmann to Deren, Brakhage, Ernie Gehr, James Benning, and Nathaniel Dorsky, have also thought of cinema as having the power to refresh, even redeem, our vision. But many of the most important directors aiming at broader audiences are also renowned for their visual styles. To mention just a few: Griffith, Feuillade, Sjostrom, Keaton, De Mille, Murnau, Lang, Dreyer, Lubitsch, and Dovzhenko; Ford, Hitchcock, and von Sternberg; Renoir, Ozu (above), Mizoguchi, and Ophuls; early Bergman, Antonioni, Jancsó, Resnais, Angelopoulos, Tarr, Tarkovsky, Kieślowski, Kiarostami, and Makhmalbaf; Scorsese, Spielberg, Michael Mann, and Tim Burton. Some, like Oshima, Sokurov, and Johnnie To, have been polystylistic, exploring many different visual pathways.

Film as an audiovisual art.

In the 1920s, many theorists feared the coming of synchronized sound, since that would thrust film back toward theatre. The “talkies” would sacrifice visual artistry to Broadway dialogue. This worry was mistaken, but I can sympathize. Probably the mandatory silence of early film pushed filmmakers to find means of visual expression. Would we have Chaplin and the other clowns if they could have spoken at the start?

Yet a great deal of sound cinema wasn’t canned theatre. Film became a synthetic medium blending imagery, the spoken word, sound effects, and music into something that was neither painting nor theatre nor illustrated radio.

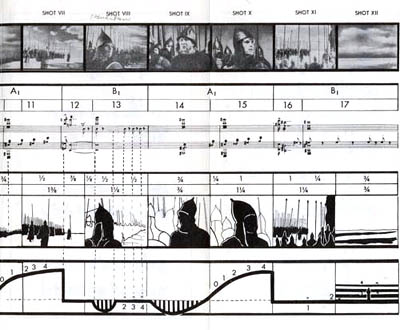

Though he’s thought of as the premiere theorist of editing, Eisenstein actually developed this idea of audio-visual synthesis. He was fascinated by the ways in which images and music worked together, creating an idea or feeling that couldn’t be expressed by either one. If shot A followed by shot B gave us something that wasn’t present in either one, then why couldn’t shot A and sound B yield the same results? He believed that Disney’s 1930s films were the strongest efforts in this direction, as when a peacock fanned out his tail to a rippling melody. Eisenstein called it “synchronization of senses.”

Eisenstein sometimes pushed this idea pretty far. His remarkable analysis of one sequence in Alexander Nevsky (sample above) tried to show how the movement of the viewer’s eye across a suite of shots actually mimicked the movement of the music. He made the case tough for himself because the shots contain almost no movement within them: Eisenstein claimed that we read the compositions from left to right, in time with the musical chords!

Not only Disney but many filmmakers of the 1930s experimented with audiovisual fusion–Kozintsev and Trauberg in Alone, Pudovkin in Deserter, Mamoulian in Love Me Tonight, Renoir in the final danse macabre of Rules of the Game, and Busby Berkeley’s Warners and MGM musicals. Welles made Citizen Kane a feast of audio-visual echoes, as when the wobbly descent of Susan’s singing voice is matched by the flickering of a stage light that finally goes out.

With magnetic and multichannel recording in the 1940s and 1950s, filmmakers could compose very complex sound mixes, and later improvements offered still more possibilities. After Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, we expected a movie to be an immersive audiovisual experience, like the light show at a rock concert. Scorsese, especially in Raging Bull and Goodfellas, created powerful mergers of music, sound effects, camera movement, and character movement. So did the Hong Kong kung-fu films of the 1970s and early 1980s. The spellbinding languor of Wong Kar-wai’s films stems largely, I think, from their synchronization of color, slow motion, drifting camerawork, and evocative music.

The avant-garde has pursued more elusive synchronizations of sense modes.The idea of synthesis was floated in the silent era, when experimenters like Oskar Fischinger used musical pieces to anchor their abstract imagery. This tendency has resurfaced in music videos, some of which (Michel Gondry’s in particular) have clear links to the experimental tradition. So too do the shorts and features of Peter Greenaway, especially in his collaborations with composer Michael Nyman. In a film like Prospero’s Books, Greenaway seems to follow Eisenstein in imagining a Wagnerian synthesis of writing, image, and sound.

By contrast, Godard explores all manner of unpredictable junctures between image and sound, with the tracks teasing us but always avoiding a complete coordination. Somewhat similar are the disjunctive image/sound juxtapositions in Peter Kubelka’s Unsere Afrikareise and Bruce Connor’s Report, or the inverse and retrograde organizations of Structural Film soundtracks like Michael Snow’s Wavelength and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation.

Film academics have begun to analyze image/ sound juxtapositions, studying the development of early talkies and more recent Dolby technology. Arguably, film researchers now pay more attention to music than they pay to imagery. By contrast, most journalistic critics ignore a film’s soundtrack, except occasionally to comment on line readings and pop tunes. As for ordinary audiences, perhaps DVD and home theatre technology have made people more aware of how movies can saturate our senses with audiovisual correspondences.

Three waivers

1. Once I floated these distinctions in a seminar discussion, and a participant mentioned that cinema was also an emotional art. I’d agree that a lot of cinema aims at arousing feelings, but this idea can be found in all the dimensions I traced. Each conception of film favors different means of stirring up emotion.

For example, the photographic approach holds that recording and revealing the world is the most effective way to move spectators, while the narrative approach favors stories as the means to that end. The performance-based approach trusts that we’ll react empathetically to the emotional states displayed by our fellow humans, but the visual-art approach says that cinema can arouse feeling by manipulating pictures in time and space, perhaps even pictures that don’t show any people at all. Eisenstein argued that synchronization of senses was the most powerful form of emotional stimulation, creating in the viewer an “ecstasy” comparable to religious fervor. Beyond these general considerations, it would be worthwhile to tease out the different sorts of emotion that each perspective tends to emphasize.

2. Someone else might ask: What about other analogies? Filmmakers and critics have sometimes compared cinema to music or poetry. Shouldn’t those arts be added to the list?

I think that these comparisons show up principally within the broad idea of film as a pictorial art. The French Impressionist directors of the silent era thought that they were making “visual music,” and Brakhage and Deren’s conceptions of the “film lyric” were mainly pictorial. (See girishshambu for thoughts on the latter.) I’d suggest that filmmakers in the pictorial-art camp have looked to these adjacent arts for models of patterning (meter, rhythm, motif development) and imagery (metaphor and subjective states in lyric verse). Filmmakers are also attracted to the idea that music and poetry tend to be suggestive rather than explicit, conveying powerful feelings in elusive and open-ended ways.

Polemically, filmmakers often conjure up these musical and literary analogies to counter the mainstream cinema’s emphasis on narrative and performance. If we think of film as lyric or rhapsody, story seems less important. The same thing goes, I think, for thinking of film as moving architecture or kinetic sculpture; the analogy again targets film’s pictorial dimension and its non-narrative potential.

3. To think of film as having an affinity with another art form isn’t to say that they’re identical. Thinking of cinema as a performance-based art, for example, doesn’t commit you to saying that film acting is the same as theatrical acting. Instead, thinking along these lines seems to create a first approximation, an initial comparison that lets you move on to notice differences. Once you consider film as a pictorial art, you can then ask in what ways it differs from other pictorial arts, or in what ways this particular movie transforms or reworks the techniques of painting. Ballet Mécanique, which we analyze in Film Art (pp. 358-366), owes a lot to cubism, but its imagery isn’t identical to what Picasso, Braque, and Gris came up with on canvas. All of these analogies seem to work best as frameworks for sensitizing us to both similarities and differences between film and other arts.

And . . . so?

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Each conception of film art harbors a good portion of truth. Each may fail to cover all of cinema, but for certain types of film, or particular movies, some are likely to be more helpful than others.

For example, it’s useful to consider David Lynch as making audiovisual works, in which blinking lights or grooves in pine planks seem uncannily synchronized with throbs and hums and Julee Cruise vibrato. Very often story and acting seem to precipitate out of an enveloping pictorial/auditory atmosphere. This isn’t to say that you couldn’t study narrative or performance in Lynch films; it’s just that taking up the audiovisual-mix perspective will throw certain aspects into sharper relief.

You could also argue that the Hollywood studio era blended many of these appeals into a single strong tradition. Story was important, but so was performance. Visual style was often striking, but so too was an expressive soundtrack that went beyond simply recording the dialogue. Sound effects, musical scores, and verbal hooks between scenes created imaginative resonances with the image track. Contrariwise, we can see some avant-garde traditions as taking a purist tack. In several of his films, Brakhage reduces narrative, purges performance, and bans sound: we have to engage wholly and solely with a pictorial experience.

Just as we can distinguish film traditions along these dimensions, we can contrast writers and thinkers. Some critics are very good in pinning down performance qualities, others excel at plot dissection or visual analysis. Arnheim is sensitive to pictorial values but he has little to contribute to understanding storytelling.

Bazin and Eisenstein are attuned to several of the dimensions I’ve traced out. Bazin’s interest in cinema’s photographic basis also alerted him to pictorial possibilities, like deep-focus and camera movement. Eisenstein, famous for his ideas on cinema’s visual dimension, was as I’ve said interested in sound as well. He was no less concerned with film performance, which he conceived as expressive movement (to be synchronized with properties of the image and the soundtrack). But he voiced almost no interest in narrative or photography.

I warned you that this blog would be theoretical, but I hope the takeaway message is clear. Cinema is teeming with artistic possibilities, and each of these frameworks can illuminate certain areas of choice and control. We don’t need to pick a single creed to live by, but we deepen our understanding of film by being sensitive to as many as we can manage.

The Celestial Multiplex

Kristin here—

The Internet is mind-bogglingly huge, and a lot of people seem to think that most of the texts and images and sound-recordings ever created are now available on it—or will be soon. In relation to music downloading, the idea got termed “The Celestial Jukebox,” and a lot of people believe in it. University libraries are noticeably emptier than they were in my graduate-school days, since students assume they can find all the research materials they need by Googling comfortably in their own rooms.

A lot depends what you’re working on. For The Frodo Franchise, studying the ongoing Lord of the Rings phenomenon would have been impossible without the Internet. A big portion of its endnotes are citations to URLs. On the other hand, my previous book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, a monograph on the stylistic and technical aspects of Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, has not a single Internet reference. Lubitsch can only be investigated in archives and libraries, where one finds the films and the old books and periodicals vital to such a project.

Vast though it is, the Internet is tiny in comparison with the real world. Only a minuscule fraction of all the books, paintings, music, photographs, etc. is online. Belief in a Celestial Jukebox usually works only because people tend to think about the types of texts and images and sounds that they know about and want access to. Yes, more is being put into digital form at a great rate, but more new stuff is being made and old stuff being discovered. There will never come a time when everything is available.

Even so, every now and then someone proclaims that in the not too distant future all the movies ever made will be downloadable for a small fee, a sort of Celestial Multiplex. A. O. Scott declared this in “The Shape of Cinema, Transformed at the Click of a Mouse” (New York Times, March 18): “It is now possible to imagine—to expect—that before too long the entire surviving history of movies will be open for browsing and sampling at the click of a mouse for a few PayPal dollars.”

Not only that, but Scott goes on, “This aspect of the online viewing experience is not, in itself, especially revolutionary.” He’s more interested in the idea that online distribution will allow filmmakers to sell their creations directly to viewers. That would be significant, no doubt, but as a film historian, I’m still gaping at that line about “the entire surviving history of movies.” Such availability would not only be “revolutionary,” it would be downright miraculous. It’s impossible. It just isn’t going to happen.

(The image above was generated to publicize the “Search inside the Music” program that is an important part of the Celestial Jukebox. Imagine movie screens with actors’ faces in those little boxes, and you’ve got the Celestial Multiplex.)

I will give Scott credit for specifying “surviving” films. Other pundits tend to say “all films,” ignoring the sad fact that great swathes of our cinematic heritage, especially in hot, humid climates like that of India, have deteriorated and are irretrievably lost.

Dave Kehr has already briefly pointed out some of the problems with Scott’s claims, mainly the overwhelming financial support that would be needed: “Tony Scott’s optimism struck me as, well, a little optimistic.” On the line about “the entire surviving history of movies,” Kehr suggests, “That’s reckoning without the cost of preparing a film for digital distribution — the same mistake made by the author of the recent vogue book ‘The Long Tail’ — which, depending on how much restoration is necessary, can run up to $50,000 a title. None of the studios is likely to pay that much money to put anything other than the most popular titles in their libraries on line.” As Kehr says, the numbers of films awaiting restoration and scanning isn’t in the hundreds, as Scott casually says. No, it’s in the tens of thousands even if we just count features. It’s more like hundreds of thousands or more likely millions if we count all the surviving shorts, instructional films, ads, porn, everything made in every country of the world. To see how elaborate the preservation of even one short medical teaching film can be, go here.

Putting aside the need for restoration, newer films present a daunting prospect. To help put the situation in perspective, let’s glance over the total number of feature films produced worldwide during some representative years from recent decades (culled from Screen Digest‘s “World Film Production/Distribution” reports, which it publishes each June): 1970, 3,512; 1980, 3710; 1990, 4,645; 2000, 3,782; and 2005, 4,603. For me the numbers conjure up the last shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark, only with just stack upon stack, row upon row of film cans.

Scott isn’t the first commentator to prophesy that all films will eventually be on the Internet. It’s an idea that crops up now and then, and it would be useful to look more closely at why it’s a wild exaggeration. It’s not just the money or the huge volume of film involved, though either of those factors would be prohibitive in itself. There are all sorts of other reasons why the advent of practical digital downloading of films will never come close to providing us with the entire history of cinema.

Coincidentally, two experts on this subject, Michael Pogorzelski, Director of the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Schawn Belston, Vice President, Film Preservation and Asset Management for Twentieth Century Fox, visited Madison this past week. Mike got his MA here in the Dept. of Communication Arts and now returns about once a year to show off the latest restored print that he has worked on. Schawn isn’t an alum, but he has also visited often enough that most students probably think he is. The two brought us the superb new print of Leave Her to Heaven that Fox and the Academy have recently collaborated on.

I figured it would be very enlightening to sit down with these two and talk about why the Internet is never going to allow us to watch just anything our hearts desire. They kindly agreed, and with my trusty recorder in tow we went for burgers—and fried cheese curds, a commodity not available in Los Angeles—at the Plaza Tavern. I’m grateful for the fascinating insights they provided into some of the less obvious obstacles to putting films on the Internet en masse.

No Coordinating Body

Before we launch in, though, one point needs to be made: there is no single leader or group or entity out there organizing some giant program to systematically put all surviving movies on the Internet. There isn’t a set of guidelines or principles. There’s no list of all surviving films. How would we even know if the goal of putting them all up had been achieved? When the last archivist to leave turned out the light, locked the door, and went looking for a new line of work?

Most of the physical prints that would be the basis for such transfers are sitting in the libraries of the studios that own them or in the collections of public and private archives (including many individuals). The studios would make films available online for profit. The archives might be non-profit organizations, but they still would need to fund their online projects in some fashion, either by government support, from private grants, or by charging a fee for downloads. Most archives are more concerned about getting the money to conserve or restore aging, unique prints than about making them widely available. Preservation is an urgent matter, and making the resulting copies universally available for public entertainment or education is decidedly a secondary consideration.

Mike works for a non-profit archive, Schawn for a studio, so together they provide a good overview of some key problems facing the creation of an ideal, comprehensive collection of movies for download.

Money

People who claim that all surviving films could simply be put on the Internet don’t go into the technology and expenses of how that could be done.

Of course, Schawn says, studios want to “digitize the library.” That phrase is highly imprecise, however. He specifies, “For the purposes of this idea of media being online, available, downloadable, streamable, whatever, that’s something that we’re dealing with now using existing video masters. So there isn’t an extra cost to quote, unquote digitize. But there is a cost to make the compression master, what we’re calling at Fox a ‘mezzanine file,’ which is basically a 50 megabit file. That’s the highest-quality ‘low’ quality version of the content from which you can derive all of the different flavors of compression for the various websites that have downloadable media.

“There’s a huge problem with this, in that Amazon, iTunes, and Google all have a slightly different technical specification of how they need the files delivered to them. If you don’t have this kind of mezzanine file, you have to make a different compressed version for each one of these, which costs something, certainly. It’s not incredibly expensive, but it’s not free.

“So why? What’s the motivation to us to compress at Fox the entire library? I don’t know. Are we going to sell enough copies of Lucky Nick Cain [a 1951 George Raft film] compressed on iTunes to cover the costs of making the compression? I don’t think so.”

Compatibility and the Onrush of Technology

Schawn’s mention of the variety of files needed by the big download services raises the problem of compatibility. It’s not just a matter of supplying the files and then forgetting about the whole thing, assuming that the film is available to anybody forever. What about new standards and formats?

Shawn: “Just as with consumer video, the standard changes, so what used to be acceptable yesterday isn’t acceptable now in terms of technical quality.” As time passes, plug-ins make access faster and cheaper, and eventually the original files don’t look good enough. He points out that currently iTunes can’t download HD. If it becomes possible later, “If you want to get 24 in HD, what Fox will have to do is go and re-deliver all the files in HD.” And presumably re-deliver again when the next big format revolution occurs.

Mike explains further, “Using the mezzanine file, you would just have to continue to reformat it to whatever the players demand. The lowest of the low quality will keep going up as people have broadband and can handle larger chunks of data faster.”

What about the film you’ve already downloaded? You acquire films using plug-ins, which change. Think how often you’re told that an update is now available. If you go ahead and keep updating, the changes accumulate. Eventually you may not be able to play the download you paid for. Quicktime will have moved way beyond what the technology was when you made your purchase.

Schawn and Mike both point out that at this stage in the history of downloading, the level of quality is still pretty bad in comparison with prints of films in theaters or on DVDs. It would be nice to think that the virtual film archive could provide sounds and images worthy of the movies themselves, but that will take a long, long time–not the “before too long” that Scott envisions.

Copyright

I raised another matter: “But what about copyright? Every time I hear something about restoration or bringing something out on DVD, it’s, ‘Well, there are rights problems.’ And some of those rights problems don’t get resolved. I assume that quite a few films that they blithely believe can be slapped up for downloading can’t be slapped up.”

Schawn: “Sure, and there are often not any kinds of provisions in the contract about Internet distribution—obviously! So you’re right, how do you deal with that?”

He pointed to Viva Zapata as a film that Fox has restored but can’t make available due to rights issues. The potential sales are not thought to warrant paying to resolve those issues. “I’m sure there are lots of titles in everybody’s libraries that you can’t just pop up on the Internet and start selling.”

The copyright barrier is worse for archives, which seldom own the exhibition or distribution rights to the films they protect. Usually—though not invariably–the studios do not object to archives owning and preserving prints. Making money through showing them or selling copies would be quite another matter.

Mike described the online presence of archival prints. “On a much smaller scale, this is being attempted in the archive world already, like on Rick Prelinger’s site [Prelinger Archives] or on the Library of Congress’s site, where they’ve put up dozens of moving-image files. True, it’s not independent cinema and it’s mostly commercials and the paper prints that have recently been restored. On Prelinger’s site it’s all the industrial films that he’s collected over the years. That has seen a good amount of traffic, but it hasn’t created new audiences for these films, I would argue. At least, not on a huge scale.”

Prelinger’s site contains only public-domain items, including the ever-popular Duck and Cover, allowing him to avoid the problem of copyright. Similarly, the Library of Congress gives access primarily to films in the pre-1915 era.

Suppose an archive and a film studio both have good-quality prints of a minor American film made in the 1940s. The archive does not have the legal right to put it online, and if the studio decides that it does not have the financial incentive to do so, that film will not be made available for downloading. A private collector might possibly create a file and make it available, but he or she would risk being threatened by the copyright-holder.

Piracy

We briefly discussed the methods used to prevent pirated copies being made from downloaded films. Like DVDs, downloads can be pirated, with people sending copies to their friends or even offering downloads for a fee in competition with the copyright holder. Copy-protection codes might make it necessary for a purchaser to keep a downloaded copy only on a hard-drive without being able to burn it onto a DVD. Another type of code could erase the file once the film had been viewed once or twice. That’s not exactly conducive to the ideal archive of world cinema, where we would hope to be able to study a film in detail if we so choose.

One might think that piracy protection mainly applies to studios, with their need to make money. Mike points out, though, that the need for such protection “even applies to the archival model, too. For films that you mention that have gone out of copyright, there’s still the same costs associated with putting a silent film that no one owns–digitizing it, creating the compressed master that goes on the Web—and they aren’t the kinds of subjects that people are going to get rich on at all, so there isn’t a lot of piracy. You don’t hear many archivists complaining, ‘Hey, you took my 1911 Lubin film, damn you! You can’t put that on your Website. That belongs on the archive’s Website.’ But that scenario becomes more of a likelihood for more popular titles. The obscure 1911 Lubin film is on one extreme, but Birth of a Nation, a well-known silent film a lot more people would like to see, is on the other. Let’s say the highest-quality copy is on the Museum of Modern Art’s Website and can be easily lifted and posted on your own site. And even if you just say, ‘Oh, I’ll charge 99 cents or I’ll charge 50 cents to stream it,’ it’s still going to be someone taking over something that the archive put all of the high-end effort and money into doing. Frankly, I think unless it’s an archive with a national mandate and a little bit higher budget to digitize and to put the contents of their archives online, there’s not going to be any motivation to make that high-end investment up front.”

Thus an archive may simply not bother to put a film on the internet because it can’t guarantee recouping the costs that would be generated.

Language and Cultural Barriers

Scott’s notion of easy access to all of surviving world cinema implicitly depends on an idea that all these films are either English-language or already subtitled or dubbed for English-speaking users.

That’s not true for a start, so there would remain a great deal of work to translate films that have never been released in English-language markets. That’s another huge, expensive task.

Then there’s the opposite side of that coin. For truly complete access, everyone in the world, whatever language they speak, would be able to download and appreciate every film. Of course, there are billions of people without computers or Internet access, and it looks unlikely that being able to go online will become universal anytime soon. (For figures on numbers of people with internet access, check here; percentages can be calculated by clicking on each country and finding the total population. In Tajikistan, for example, .07% of the population was online in 2005. One has to assume that a lot of connections in some of those countries are dial-up, so downloading films would be virtually impossible. [June 21, 2010: In 2008, Tajikistan’s online population has grown to .08%.])

So let’s just say that for the foreseeable future downloadable films would “only” need to be subtitled in the languages of countries or regions where significant numbers of people subscribe to PayPal.

In our conversation, Schawn pointed out that digital compression files mean that there can be huge numbers of versions, with different soundtracks dubbed in or different subtitles added. Technically it’s possible to do all that translation. Still, “it’s very complicated. So for worldwide distribution of anything, like you’re talking about your silent film. If you’re in Pakistan, do you get the American version of the movie or do you get the version of the movie with the intertitles appropriate to wherever it is that you’re showing it? If so, that quickly compounds the amount of stuff that’s digitized.”

I responded, “Yeah, or a 1930s Japanese film put on the Internet for downloading, subtitled in every language where there are people that can pay for it. The more you think about it, the more absurd it becomes.”

Scott must be implying as well that there is some single “original” version of a film and that that version would be the one available in this ideal collection in cyberspace. Yet any archivist or film historian knows that multiple versions of a given film are typically made, depending partly on the censorship laws of the different countries where it is originally shown. In making downloadable files available, does a studio or archive use only the original version of a film made for its country of origin and thus risk having it include material offensive to viewers in some places where it might be downloaded? Or does a whole slew of different versions, one acceptable in, say, Iran, another inoffensive to the Danes, and still another compatible with Senegalese social mores, get put online? How could one even gather all such versions and digitize them? National film archives tend to have government mandates to concentrate primarily on preserving their own countries’ films. Not every version of every film gets saved.

The Bottom Line

For all the reasons noted here and others as well, film availability for download will follow pretty much the same economic principles that have governed film sales in other media. Mike’s opinion is, “Whether they’re from an archive or a studio, I think things’ll start going online in the same pace that they came onto DVD, in an eight to ten-year cycle. And there still will be large gaps.”

Schawn interjects, “Just as there are on DVD.”

Mike concludes, “There’s stuff that will never go online. Yeah, just as on DVD.”

*

A truly celestial screening: a restored 35mm print of Bertolucci’s 1900 projected free, under the stars in the Piazza Maggiore, Bologna, summer of 2006

Film forgery

DB here:

In early July 1947, about two weeks before I was born, an alien spacecraft crashed near Roswell, New Mexico. Local ranchers found scattered debris, and soon the US government had cordoned off the area. At the crash site was a flying saucer.

Around it lay several alien creatures. They were small and slender, with large heads, dark slanted eyes, and only four fingers. They were clutching small, flat control boxes. One creature was still alive, and it was taken to an Air Force base in Texas, where it lived for a few more years. The dead bodies were autopsied, and at least one autopsy was filmed.

The US government tried to keep the Roswell incident a secret, but dogged researchers have brought to light eyewitness testimony, official documents, and leaks. There is but one conclusion to draw. We have encountered beings from another planet.

Everything I have just said is almost certainly untrue, except for that part about my being born.

Artistic crimes

Although I’ve been interested in UFOs since I was a kid, what triggered this blog was the recent scandal around pianist Joyce Hatto. Her husband has confessed that her many CD performances of classical pieces were actually digital copies of other pianists’ releases. Critics who praised her virtuosity now have red faces. Denis Dutton, a philosopher of art specializing in what he calls “artistic crimes,” has written a lively essay about the mess.

Summing up what is now a pretty well-established position in aesthetics, Dutton writes that our full understanding of an artwork depends on a general sense of how the work came to be what it is. We may say that all that matters are the words on the page or the paint on the canvas or the sounds in our ear. But our understanding of those sensory features depends upon assumptions about the origins and authenticity of the work.

Here’s Dutton:

The Joyce Hatto episode is a stern reminder of the importance of framing and background in criticism. Music isn’t just about sound; it is about achievement in a larger human sense. If you think an interpretation is by a 74-year-old pianist at the end of her life, it won’t sound quite the same to you as if you think it’s by a 24-year-old piano-competition winner who is just starting out. Beyond all the pretty notes, we want creative engagement and communication from music; we want music to be a bridge to another personality. Otherwise, we might as well feed Chopin scores into a computer.

Dutton has written many subtle and enjoyable pieces on what he calls aesthetic crimes—plagiarism, forgery, and the like. (See his website for many of these, along with continuing updates on his Hatto comments.)

Both plagiarism and forgery present a false history of how a work came into being. You commit plagiarism when you claim as your own something that somebody else created. The Hatto case is plagiarism, just as much as if one college student submits a paper that her roommate has already submitted for another course. A forgery is in a way the reverse: You make the artwork but claim that it was actually created by somebody else, typically somebody famous.

It’s interesting to speculate about what a plagiarized film would be. You can plagiarize somebody’s script by passing it off as your own. Periodically there are lawsuits from aspiring screenwriters claiming that producers ripped off spec scripts. But can you plagiarize a movie itself?

I suppose you can try, but it would be very hard to pull off. I might swipe a finished film’s negative from the lab and then make new credit sequences that replace the director’s name with mine. But I could hardly expect to get away with it, since nearly everybody involved would notice. Perhaps I could find an old forgotten film and then stick my name in there somewhere. Again, though, I’d have to explain how I could have been around to make that 1930s Monogram musical or 1960s Taiwanese kung-fu film. As Dutton points out, I’d have to tell a plausible story about how the work came to be.

What if I just swipe bits? Recall that a plagiarism can be partial or total. Even if you pluck just a paragraph or two from your roommate’s term paper and write the rest of yours unaided, that still counts as plagiarism. But if your roommate makes a film, and you lift a sequence from it for your own, the case for plagiarism seems to me less clear—especially if she gives you the same sort of permission she might grant for a paper.

Does Bruce Conner’s use of stock footage in A Movie constitute plagiarism? We assume that he didn’t shoot all this material, yet he doesn’t give credit to any of his sources. Indeed, as he once wrote to Kristin and me, “Only the splices are mine.”

We’d now be inclined to say that Conner appropriated the shots, something a great deal of contemporary art does. Rappers, samplers, and electronic artists like Moby are clearly seizing work without acknowledgment. Perhaps entertainment companies are in effect complaining that YouTube downloads and Web mashups are plagiarism. Yet there’s no intent to deceive the viewer about the source, so plagiarism doesn’t seem the right concept for these instances.

What about cases in which one director replaces another on a film project and assimilates material that the first one shot? Did Richard Lester plagiarize Richard Donner’s footage for Superman II? It sounds weird to say that; Lester just used parts of what Donner left.

Literary plagiarism can involve stealing not only exact wording but also original ideas. This is a fuzzy area, obviously, since ideas can’t be copyrighted. But it’s even fuzzier in filmmaking, where such swiping is pretty common. All those copies and unauthorized remakes of Hollywood films, like Hong Kong Pretty Woman and Kaante, the Bollywood version of Reservoir Dogs, might count as plagiarism. (The producer of Kaante calls it an homage.) Still, my inclination is to say that plagiarism is a difficult concept to transfer to the visual/moving image arts; its core application may be literary and, as the Hatto case reveals, musical performance.

Anyhow, today I’m interested in the other major aesthetic crime, forgery. The question is: Can you forge a film?

Forgery and pastiche

Nowadays, especially after Forrest Gump, we’re accustomed to seeing simulated documentary footage in fictional films. The earliest example I can recall is Citizen Kane, in which the newsreel fakes old footage showing Kane campaigning with Teddy Roosevelt or standing beside Hitler.

Such shots don’t claim to be factual. No matter how realistic the shot looks, the presence of the protagonist tells us that it’s functioning within a fictional tale. There is, in other words, no question of deceit. It’s a case of artistic license, somewhat like dressing contemporary actors in period costume. Had Welles claimed that he had discovered old newsreel clips containing a mysterious man who resembled him, that would be a different story.

I’d suggest that such frank efforts to mimic the look and feel of older footage fall into the category of pastiche. Pastiche is the acknowledged copying of techniques of recognized art styles. In Stravinsky’s neoclassical period, he composed Pulcinella, an overt pastiche of Pergolesi.

It’s a separate but interesting question about how accurate a filmic pastiche is. The Good German, I suggested in previous posts, tries to be a pastiche, but it isn’t very skilful. Indeed, most aren’t. Bergman’s TV film The Last Scream (1995) includes a pastiche of the great 1910s filmmaker Georg af Klercker, but it’s not faithful to af Klercker’s style. (The mock silent film in Prison and Persona is somewhat better.) Welles’ pastiche of old footage in Kane‘s “News on the March” segment is more carefully done, especially for its time. The movement is convincingly jerky for silent film shown at sound speed, and Welles cleverly scratched and mis-exposed some of the staged footage, anticipating a technique often used today.

The most convincing film pastiche I know since Kane comes in the Japanese film To Sleep so as to Dream (Yume miruyoni nemuritai, 1986). The plot involves two detectives trying to find a lost silent film, and at intervals we see clips of it, a swordplay movie (chambara). The shooting style is very close to the flashy technique we see in films from the era; obviously the director Hayashi Kaizo studied surviving chambara carefully. In one scene, a swordfighter pauses in a doorway, and we see him over the shoulder of his adversary (first image below). As the fighter makes a hurling movement, we cut in a bit closer. Suddenly the foreground figure’s arm jerks up, revealing a dagger jabbed into his wrist (second image below).

Hayashi has also faded and flared the imagery, as if our print had degraded through duping and ill use.

Pastiches aren’t forgeries because there’s no intent to deceive. Just as important, the history of their production tells us that they aren’t genuine. As Dutton points out, it’s not enough for a forgery to look like an old artwork; to succeed, it needs a provenance, a false history of creation and subsequent ownership. I can think of two well-known films that can be considered forgeries to some degree.

With typical Scottish pragmatism

Peter Jackson and Costa Botes’ Forgotten Silver (1995) tells the story of the neglected New Zealand filmmaker Colin McKenzie. McKenzie started making films around the turn of the century, and in the course of his career he built his own camera, manufactured his own film stock, invented talking pictures and color cinematography, shot the first close-up, and erected a gigantic set in the New Zealand bush. Many experts, including Leonard Maltin and various archivists, attest to McKenzie as a visionary filmmaker on a par with D. W. Griffith.

Of course he never existed. But in the straight-faced manner of This is Spinal Tap, Forgotten Silver pretends that he did. The result is a brilliant parody of the filmmaker documentary as practiced above all by Kevin Brownlow. We get the talking-heads experts, the search for lost footage and locations, the pan-and-zoom coverage of old stills, and the terse journalistic voice-over. (“With typical Scottish pragmatism he built his farm the hard way.”) The film makes fun of nationalistic film history (we did it before the others) and the biographical convention that treats the artist as a rebellious, suffering soul.

The silliness of the enterprise is pretty apparent. The resourceful McKenzie is a one-man film industry. He devises a projector driven by steam power, he manufactures film emulsion from eggs, he builds his Salome city single-handed, and a Russian woman named Alexandra Nevsky tells us about Stalin’s interest in our hero. To anybody who knows Harvey Weinstein’s tendency to slice up the films he distributes, his remark about taking an hour out of McKenzie’s masterwork gives the whole game away.

There are clips as well. The passages from McKenzie’s Griffithian feature Salome are fair approximations of 1920s international style, a bit à la Guy Maddin, while the oldest shots look remarkably accurate.

But Jackson and Botes decided to go Spinal Tap one better. Before Forgotten Silver aired on Kiwi television, they let a journalist publish a story suggesting that McKenzie really existed. The mockumentary was taken for truth, and McKenzie immediately became a new national hero. Startled, the filmmakers quickly confessed their chicanery. Some people enjoyed the laugh, but others felt cheated and muttered about artists who fool around at the taxpayers’ expense. The fullest account I know is in Brian Sibley’s biography Peter Jackson: A Film-Maker’s Journey (Hammersmith: HarperCollins, 2006), 280-302. On the web, have a look here.

Because of the Jackson/Botes hoax concerning the “rediscovered” footage, the faked McKenzie scenes became forgeries, at least for a little while. When the mischief was discovered, the clips stood revealed as parodies or pastiches of silent film. If we have reason to believe that the footage is authentic, we think of McKenzie as a pioneer filmmaker. If we’re told it’s all faked, we congratulate our adept contemporaries.

In the spirit of Forgotten Silver are other nonexistent but rediscovered filmmakers. Most recently we have J. X. Williams, conjured up by Craig Baldwin and Noel Lawrence. Williams’ Peep Show was presented as an authentic 1965 movie, although many had their doubts when they saw footage lifted from The Man with the Golden Arm and other pictures. Lawrence insists that Williams existed and has set up a website dedicated to him, but one has to believe that it’s less an effort to deceive than a PoMo performance exercise.

The Gray’s anatomy

The grandest film forgery I know is Alien Autopsy. This has been a favorite of mine since I saw the Fox TV program, Alien Autopsy: Fact or Fiction?, broadcast in the summer of 1995. Kristin and I were especially pleased to see our old friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, then of Eastman House, as a talking head in it. I got the movie on laserdisc, hoping to use it in a film theory class. I never did, but now I get a chance to blog about it! The show is available on DVD, including the full “original” footage. A useful Wikipedia overview is here.

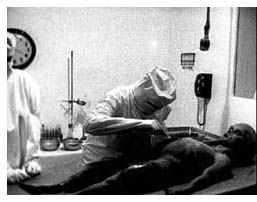

The film shows an autopsy performed on one of the saucer creatures, known in UFO parlance as a Gray. The grainy black-and-white footage presented to the public runs about 16 minutes, but it’s supposedly drawn from much more material. There seem to me three central issues in establishing its authenticity: what we are shown, how we are shown it, and when it was made.

What we see is a sterile white room with a stiff Gray stretched out on a lab table. Two figures in decontamination suits move around the table, cut into the body, and remove various organs. A third, rather creepy figure can occasionally be glimpsed in a window watching. The furnishings are pretty sparse, but you can see a clock, a wall phone, a microphone, and an instrument tray.

What we see is a sterile white room with a stiff Gray stretched out on a lab table. Two figures in decontamination suits move around the table, cut into the body, and remove various organs. A third, rather creepy figure can occasionally be glimpsed in a window watching. The furnishings are pretty sparse, but you can see a clock, a wall phone, a microphone, and an instrument tray.