Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Charlie, meet Kentaro

DB here:

Echoing an earlier virtual roundtable on this blog, I want to write about my two favorite B film series, now available in handsome DVD boxed sets. Both series were mounted at 20th Century-Fox, both were adapted from genre fiction, and both seem very much of their time: lots of exotic Orientalia, and probably too many middle-aged men in tiny mustaches and broad fedoras. But to my mind these films offer brisk, unpretentious entertainment, solidly crafted and surprisingly subtle. They also allow us to trace some changes in the ways movies were made across the 1930s.

There’s another reason for this blog. Tim Onosko, a friend of Kristin’s and mine, recently died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Tim was an extraordinary figure, as you can find here. He was central to Madison film culture for forty years, and in his various creative activities, he shaped everything from The Velvet Light Trap to Tokyo Disneyland. He and his wife Beth also made a documentary, Lost Vegas: The Lounge Era. Tim and I enjoyed talking about the two series I’ll be mentioning. He loved these films, as he loved all films and popular culture generally, with a sharp-eyed dedication. So this is a small effort at an homage to Tim.

The Hawaiian and the Japanese

Charlie Chan, a Hawaiian police inspector of Chinese ancestry, became famous in a series of six novels by Earl Derr Biggers, from The House without a Key (1925) to The Keeper of the Keys (1932). Chan novels were brought to the screen at the end of the 1920s by Pathé and Universal, but for Behind That Curtain (1929) Fox took over the franchise. Warner Oland, a Swedish-born actor who had often played Asians, settled into the lead role in Charlie Chan Carries On (1931). He played Chan up through Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo (1937), then fled Hollywood under peculiar circumstances and went to Sweden, where he died soon afterward.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Each series echoed its mate. Tim claimed that in an early Chan, a character is reading a Moto story in the Saturday Evening Post, though I’ve never found that scene. When Charlie’s Number One Son turns up to help Moto in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938) it’s revealed that Charlie and Moto are old friends. There’s a more elegiac moment in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) when a theatre displays a poster for the Chan series—perhaps as well serving as an homage to the recently deceased Warner Oland. Despite Oland’s death, the Chan series continued until 1949, with Sidney Toler in the role, but with Lorre’s departure the Moto films ceased.

Having a Caucasian actor play an Asian protagonist was common at the time. Today, it seems condescending or worse, but we should recognize that the films featured Asian actors as well, often in significant roles. The most visible example is Keye Luke as Charlie’s highly Americanized son. Forever blurting out “Gosh, Pop!” Luke is a lively and likable presence.

Just as important, the portrayal of the detectives is remarkably free of racism. Charlie and Moto are clearly the quickest-witted characters, and both prove resourceful in all kinds of ways. Moto’s judo subdues thugs twice his size, and Charlie is up-to-date in the new technologies of detection.

The scripts go out of their way to show both men skilfully handling the prejudice they encounter. In Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936), a blatantly racist cop (William Demarest) who calls Charlie “Chop Suey” is mocked incessantly by everyone, most gently by Charlie. Moto excels at pretending to be the stereotypical Asian (“Ah, so!” “Suiting you?”). And both our protagonists are sympathetic to others who are in minorities. Charlie is notably unwilling to participate in guying black servants as the whites do, and Charlie Chan at the Circus (1936) shows his keen sympathy with the “freaks,” treating them with quiet courtesy. The Moto series presents a Japanese who doesn’t seem to share his country’s goal of ruling Asia. In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he enjoys a respectful friendship with a Chinese family of declining fortunes.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

Looks and looking

We can learn a lot by studying the two main actors’ performance styles. The plump Oland plays Chan as stolid but not ponderous. He floats across a room and gravely circulates among suspects, giving the films their deliberate pacing. Oland’s drawn-out delivery and pauses were due, people say, to his acute alcoholism, but he never seems to be struggling to find his lines. Charlie is at pains to be unobtrusive, modest, and tactful; his characteristic gesture is a simple one, letting the fingertips of one hand grasp one finger of the other.

He is a loving father, doting on his many children (all in tow in Charlie Chan at the Circus). Although Number One Son may exasperate him, you would go far in films to find as warm a portrayal of a father’s affectionate efforts to curb an impulsive boy. See Charlie Chan at the Olympics (1937) for the casual byplay between Charlie and Lee, now an art major and a member of the swimming team. Lee’s bubbling energy gives Charlie’s imperturbability even greater gravitas.

The short and slim Lorre plays Moto as a suave man-about-Asia, hand thrust casually into his trouser pocket. Moto is an art connoisseur, a graduate of Stanford (class of ‘21), and a master of many languages. Lorre, so easily caricatured at the time and now, hit on a brilliant idea: He didn’t give Moto stereotyped tricks of pronunciation. Unlike Oland, he didn’t usually drop articles or compress syntax.(2) Lorre just played the part in his lightly accented English, as he would in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. He added a soft-spoken delivery, a modest smile, and a trick he may have picked up from Marlene Dietrich–ending his sentences with a slight upward inflection, turning every statement into a polite question.

Reaction shots of suspects are a convention of these movies, but after several cuts show us everybody looking shifty, the reverse shots of our heroes show us that they miss none of this byplay. (3) Charlie is alert, but he hides his penetrating view behind a bland courtesy. As Moto, Lorre presents a more aggressive intelligence. Peering through round spectacles, those bug eyes, panic-stricken in M, can now become pensive or bore into a suspect. Charlie needs the force of law, but Moto, who usually acts alone, is dangerous by himself, and Lorre’s horror-show pedigree serves him well in giving his hero’s stare a sinister edge.

Listening and looking

You can argue that Oland and Lorre, coming to their parts only a few years after sound had arrived, helped Hollywood develop a wider array of acting styles. We historians of Hollywood have rightly praised gabby comedies like Twentieth Century (1934) and It Happened One Night (1934) for finding a performance technique suited to sound films, particularly in the wake of technical improvements in acoustic recording. If movies had to talk, we think, they should really talk, fast and hard and heedlessly. In this church our Book of Revelations is His Girl Friday (1940).

Lorre and Oland, like Karloff and Lugosi, remind us of the virtues of being gentle, spacious, and deliberate. This isn’t a reversion to those hesitant, strangled mumblings of the earliest talkies. Rather, the movies’ plots surround our Asians with rapid-fire duels of cops and reporters, snapping out “Say!” and “Hiya, sister!” and “Watch it, wise guy!” and “Don’t be a sap!” Against clattering percussion Moto and Charlie deliver a melodic purr.

Some people still believe that in Citizen Kane Welles and Gregg Toland introduced American film to steep low angles, tight depth compositions, and noirish lighting. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I’ve argued that the Gothic, somewhat cartoonish look of Kane synthesized and amplified trends that were emerging during the 1930s. The Chan and Moto films are wonderful places to study these visual schemas.

E

E

In Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935, above), cinematographer Charles G. Clarke (whom Kristin and I interviewed for the Hollywood book) offers flashy depth and silhouette effects, and nearly all the Chan films have moments of clever staging. Charlie Chan at the Opera, above, is particularly engrossing, with its huge set (recycled from the A-picture Café Metropole, 1937). The same film, incidentally, contains scenes of a fictitious opera, Carnival, composed by Oscar Levant. This was an ambitious gesture for a B film and looks forward to Bernard Herrman’s Salammbo sequences of Kane.

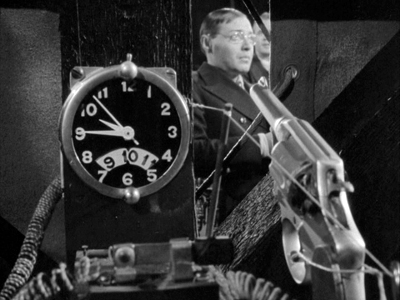

The Motos are even more remarkable. You want wild angles? Venetian-blind shadows? Telltale reflections in eyeglasses? Swishing bead curtains? Twisted expressionist décor? You’ve come to the right place.

Some late thirties Fox sets seem to have been stored in Caligari’s Cabinet. Watching these films, it becomes clear that Kane applied the moody technique of crime and horror films to ambitious drama. One bold setup in Mr. Moto’s Gamble looks like a dry run for a Toland big-foreground composition (done here, as often in Kane, through special-effects). I like this shot so much I used it in Figures Traced in Light.

Yet all this creativity took place within severe constaints. These were B pictures, running under seventy minutes and shot in a month or so. Three or four would be released each year. They shamelessly used stock footage, leftover sets, and the same players in different roles from film to film. (Watch for Ray Milland, Ward Bond, and others on the way up.) The boys in the Fox cutting room seem to have enforced a remarkable uniformity: most of the Chans in these DVD sets, regardless of director, contain between 600 and 660 shots, while the faster-paced Motos average between four and six seconds per shot. The actors created hurdles too. Oland sank even further into drinking while the high-strung Lorre was addicted to morphine and periodically retired to sanitariums to recover. Those were the days; rehab wasn’t yet a matter for infotainment.

The Fox DVD boxes are model releases. The prints are well-restored (better on the second sets than the first) and filled with astute, informative supplements. We get a lot of detail about production matters, including why Oland left Hollywood. There is welcome biographical background on master minds like Sol Wurtzel and Norman Foster. I still want to know more about James Tinling, though; his direction of Mr. Moto’s Gamble and Charlie Chan in Shanghai (1935) belies his reputation as a hack.

“The cinema is not dangerous,” Moto reassures the Siamese tribesmen about to be filmed in Mr. Moto Takes a Chance (1938). Immediately, the woman who’s being filmed dies. The adventure begins. Who can resist movies like these? They have kept me happy since my childhood, when I watched them on Sunday afternoon TV. They can keep your children, and you, happy too.

For some good reading, see John Tuska, The Detective in Hollywood (Doubleday, 1978); Charles Mitchell, A Guide to Charlie Chan Films (Greenwood, 1999); Howard M. Berlin, The Complete Mr. Moto Film Phile: A Casebook (Wildside, 2005); and Stephen Youngkin, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre (University Press of Kentucky, 2005).

For more on Charlie, click here. Charles Mitchell has a nice wrapup on Kentaro here.

(1) The involvement of an innocent romantic couple was a convention of slick-magazine fiction of the day (both the Chan and Moto novels were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post), and it recurs throughout mainstream detective fiction of the 1930s. Most writers of the period wrestled with the problem of how to make the couple interesting. See Carter Dickson/ John Dickson Carr’s short story, “The House in Goblin Wood,” for a brilliant handling of the device.

(2) As many commentators have noted, Charlie doesn’t speak pidgin English; he seems to be mentally translating. Interestingly, the generation gap is apparent here too, since Number One Son speaks peppy and perfect American slang.

(3) One hyperclever moment in Mr. Moto’s Gamble gives us the usual rapid-fire array of single shots of discomfited suspects but neglects to show us the real culprit.

This is your brain on movies, maybe

United 93.

From DB:

Normally we say that suspense demands an uncertainty about how things will turn out. Watching Hitchcock’s Notorious for the first time, you feel suspense at certain points–when the champagne is running out during the cocktail party, or when Devlin escorts the drugged Alicia out of Sebastian’s house. That’s because, we usually say, you don’t know if the spying couple will succeed in their mission.

But later you watch Notorious a second time. Strangely, you feel suspense, moment by moment, all over again. You know perfectly well how things will turn out, so how can there be uncertainty? How can you feel suspense on the second, or twenty-second viewing?

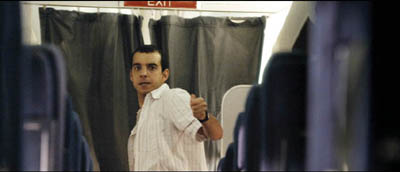

I was reminded of this problem watching United 93, which presents a slightly different case of the same phenomenon. Although I was watching it for the first time, I knew the outcomes of the 9/11 events it portrays. I knew in advance that the passengers were going to struggle with the hijackers and deflect the plane from its target, at the cost of all their lives. Yet I felt what seemed to me to be authentic suspense at key moments. It was as if some part of me were hoping against hope, as the saying goes, that disaster might be avoided. And perhaps the film’s many admirers will feel something like that suspense on repeated viewings as well.

Psychologist Richard Gerrig in his book Experiencing Narrative Worlds calls this anomalous suspense: feeling suspense when reading or viewing, although you know the outcome.

Anomalous suspense: Some theories

Anomalous suspense has been fairly important in the history of film. One of the most famous instances in the early years of feature film is the assassination of President Lincoln in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith prolongs the event with crosscutting and detail shots in a way that promotes suspense, even though we know that Booth will murder Lincoln. Anomalous suspense, of course, isn’t specific to movies; we can feel this way reading a familiar book or watching a TV docudrama about historical events. Young children listening to the story of Little Red Riding Hood seem to be no less wrought up on the umpteenth version than on the first.

This is very odd. How can it happen?

One answer is simple: What you’re feeling in a repeat viewing, or a viewing of dramatized historical events, isn’t suspense at all. Robert Yanal has explained this position here. He suggests that you’re responding to other aspects of the story. Maybe in rewatching Notorious you’re enjoying the unfolding romance, and you attribute your interest to suspense. And there are feelings akin to suspense that don’t rely on uncertainty–dread, for instance, in facing likely doom. (This is my example, not Yanal’s, but I think it’s plausible.) Another possibility Yanal floats is that on repeat viewings, you have actually forgotten what happens next, or how the story ends.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Richard Gerrig, the psychologist who gave anomalous suspense its name, offers a different solution. He posits that in general, when we reread a novel or rewatch a film, our cognitive system doesn’t apply its prior knowledge of what will happen. Why? Because our minds evolved to deal with the real world, and there you never know exactly what will happen next. Every situation is unique, and no course of events is literally identical to an earlier one. “Our moment-by-moment processes evolved in response to the brute fact of nonrepetition” (Experiencing Narrative Worlds, 171). Somehow, this assumption that every act is unique became our default for understanding events, even fictional ones we’ve encountered before.

I think that Gerrig leaves this account somewhat vague, and its conception of a “unique” event has been criticized by Yanal, in the article above. But I think that Gerrig’s invocation of our evolutionary history is relevant, for reasons I’ll mention shortly.

Suspense as morality, probability, and imagination

The most influential current theory of suspense in narrative is put forth by Noël Carroll. The original statement of it can be found in “Toward a Theory of Film Suspense” in his book Theorizing the Moving Image. Carroll proposes that suspense depends on our forming tacit questions about the story as it unfolds. Among other things, we ask how plausible certain outcomes are and how morally worthy they are. For Carroll, the reader or viewer feels suspense as a result of estimating, more or less intuitively, that the situation presents a morally undesirable outcome that is strongly probable.

When the plot indicates that an evil character will probably fail to achieve his or her end, there isn’t much suspense. Likewise, when a good character is likely to succeed, there isn’t much suspense. But we do feel suspense when it seems that an evil character is likely to succeed, or that a good character is likely to fail. Given the premises of the situation, the likelihood is very great that Alicia and Devlin will be caught by Sebastian and the Nazis, so we feel suspense.

What of anomalous suspense? Carroll would seem to have a problem here. If we know the outcome of a situation because we’ve seen the movie before, wouldn’t our assessments of probability shift? On the second viewing of Notorious, we can confidently say that Alicia and Devlin’s stratagems have a 100% chance of success. So then we ought not to feel any suspense.

Carroll’s answer is that we can feel emotions in response to thoughts as well as beliefs. Standing at a viewing station on a mountaintop, safe behind the railing, I can look down and feel fear. I don’t really believe I’ll fall. If I did, I would back away fast. I imagine I’m going to fall; perhaps I even picture myself plunging into the void and, a la Björk, slamming against the rocks at the bottom. Just the thought of it makes my palms clammy on the rail.

Carroll points out that imagining things can arouse intense emotions, and his book The Philosophy of Horror uses this point to explain the appeal of horrific fictions. The same thing goes, more or less, for suspense. If the uncertainty at the root of suspense involves beliefs, then there ought to be a problem with repeat viewings. But if you merely entertain the thought that the story situation is uncertain, then you can feel suspense just as easily as if you entertained the thought that you were falling off the mountain top.

In other words, the relation between morality and probability in a suspenseful situation is offered not to your beliefs but to your imagination. When you judge that in this story the good is unlikely to be rewarded, you react appropriately–regardless of what you know or believe about what happens next. Carroll outlines this view in his book Beyond Aesthetics.

How are we encouraged to entertain such thoughts in our imagination? Carroll indicates that the film or piece of literature needs to focus our attention on the suspenseful factors at work, thus guiding us to the appropriate thoughts about the situation. There might, though, be more than attention at work here.

The firewall

In Consciousness and the Computational Mind (1987), psychologist Ray Jackendoff asked why music doesn’t wear out. When composers write tricky chord progressions or players execute startling rhythmic changes, why do those surprise or thrill us on rehearing? Similarly, you’ve seen the Müller-Lyer optical illusion many times, and you know that the two horizontal lines are of equal length. You can measure them.

Yet your eyes tell you that the lines are of different lengths and no knowledge can make you see them any other way. This illusion, in Jerry Fodor‘s phrase, is cognitively impenetrable.

We can reexperience familiar music or fall prey to optical illusions because, in essence, our lower-level perceptual activities are modular. They are fast and split up into many parallel processes working at once. They’re also fairly dumb, quite impervious to knowledge. Jackendoff suggests that our musical perception, like our faculties for language and vision, relies on

a number of autonomous units, each working in its own limited domain, with limited access to memory. For under this conception, expectation, suspense, satisfaction, and surprise can occur within the processor: in effect, the processor is always hearing the piece for the first time (245).

The modularity of “early vision”–the earliest stages of visual processing–is exhaustively discussed by Zenon W. Pylyshyn in Seeing and Visualizing: It’s Not What You Think (2006).

As students of cinema, we’re familiar with the fact that vision can be cognitively impenetrable. We know that movies consist of single frames, but we can’t see them in projection; we see a moving image.

Early vision works fast and under very basic, hard-wired assumptions about how the world is. That’s because our visual system evolved to detect regularities in a certain kind of environment. That environment didn’t include movies or cunningly designed optical illusions. So there might be a kind of firewall between parts of our perception and our knowledge or memory about the real world.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

So here’s my hunch: A great deal of what contributes to suspense in films derives from low-level, modular processes. They are cognitively impenetrable, and that creates a firewall between them and what we remember from previous viewings.

A suspense film often contains several very gross cues to our perceptual uptake. We get tension-filled music and ominous sound effects, such as low-bass throbbing. We get rapid cutting and swift camera movements. Often the shots are close-ups, as in Notorious‘s wine-cellar scene and during the characters’ final descent of the staircase. Close-ups concentrate our vision on one salient item, creating the attentional focus Carroll emphasizes. The shots are often cut together so fast that we barely have time to register the information in each one.

This isn’t to say that the action itself has to be fast. The action in the Hitchcock scenes isn’t rapid, but its stylistic treatment is. In typical suspense scenes, our “early vision” and “early audition,” biased toward quick pickup, are given rapid-fire bursts of information while our slower, deliberative processes are put on hold. This is happening in the Birth of a Nation assassination scene, as well as in the frantic second half of United 93.

Further, what is shown can push our processing as well. Seeing people’s facial expressions touches off empathy and emotional contagion, perhaps through mirror neurons.

This tendency may explain why we can, momentarily, feel a wisp of empathy for unsympathetic characters. When their expressions show fear, we detect and resonate to that even if we aren’t rooting for them to succeed.

We may also be responding to some very basic scenarios for suspenseful action. Imagine dangling at a great height; “hanging” is the root of the word suspense. Or imagine hurtling toward an obstruction, or being stalked by an animal, or being advanced upon by a looming figure. As prototypes of impending danger, these events may in themselves trigger a minimal feeling of suspense. And such situations are part of filmic storytelling from its earliest years.

Maybe we’re predisposed to find facial expressions and dangerous situations salient because of our evolutionary history, or maybe they’re learned from a very young age. Either way, such responses don’t require much deliberate thinking. They just trigger rapid responses that we can reflect upon later.

Stylistic emphasis and prototype situations surely help the attention-focusing that Carroll discusses. But I’m suggesting something stronger: Many of these cues don’t merely guide our attention to the critical suspense-creating factors in the scene. These cues are arresting and arousing in themselves. They trigger responses that, in the right narrative situation, can generate suspense, regardless of whether we’ve seen the movie before.

Beyond these cues, of course we have to understand the story to some degree. Probably some of the aspects of storytelling that Carroll, Gerrig, and others (including me) have highlighted come into play. As Hitchcock famously pointed out, suspense sometimes depends on telling the viewer more than the character knows. We have to see the bomb under the table that the character doesn’t know about. Suspense is also conjured up by Carroll’s ratio of morality to probability, our real-world understanding of deadlines, and other higher-order aspects of comprehension. In addition, our knowledge of how stories are typically told probably shapes our uptake. We expect suspense to be a part of a film, and so we’re alert for cues that facilitate it.

Involuntary suspense

So I’m hypothesizing that part of the suspense we feel in rewatching a film depends on fast, mandatory, data-driven pickup. That activity responds to the salient information without regard to what we already know.

According to this argument, the sight of Eve Kendall dangling from Mount Rushmore will elicit some degree of suspense no matter how many times you’ve seen North by Northwest, and that feeling will be amplified by the cutting, the close-ups, the music, and so on. Your sensory system can’t help but respond, just as it can’t help seeing equal-length lines in the pictorial illusion. For some part of you, every viewing of a movie is the first viewing.

This tendency may hold good for other emotions than suspense. In the psychological jargon I adopted in Narration in the Fiction Film, experiencing a narrative is likely to be both a bottom-up process and a top-down process. Suspense and other emotional effects in film may depend not only on conceptual judgments about uncertainty, likelihood, and so on. They may also depend on quick and dirty processes of perception that don’t have much access to memory or deliberative thinking.

Film works on our embodied minds, and the “embodied” part includes a wondrous number of fast, involuntary brain activities. This process gives filmmakers enormous power, along with enormous responsibilities.

PS: 9 March. Jason Mittell writes a comment, based on his recent research on TV fans’ attitudes toward spoilers, at his site here. More later, I hope, when I have a chance to assimilate his argument.

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

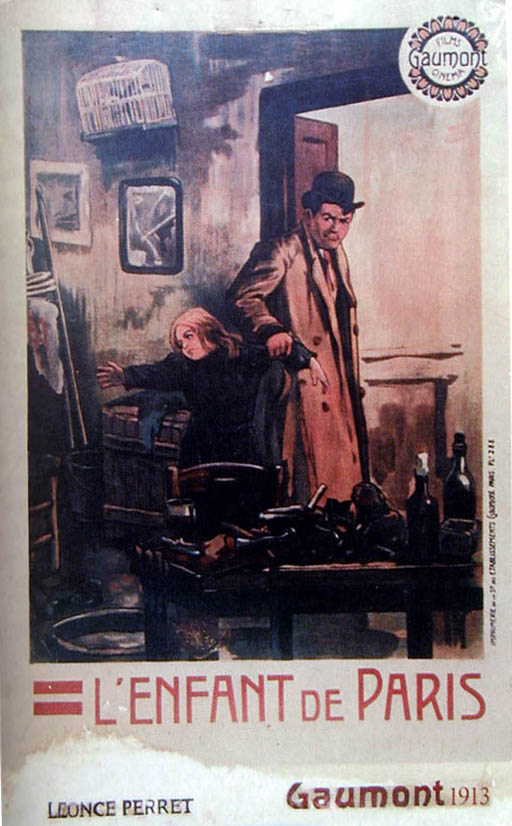

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.

3 notions about CREMASTER 2

DB here:

The week before last brought Matthew Ryle to the UW–Madison campus for a talk and a panel discussion. As Ryle pointed out, it’s hard to decide exactly what he should be called. He has the title of Chief Fabricator at Matthew Barney’s studio, and in Barney’s Cremaster film cycle he serves as Production Designer. He’s been called a Set Designer too, and he assists in the making of sculpture pieces that Barney exhibits in museums. Ryle is an important artifact-maker in his own right, having built the tallest sign in North America.

Nobody could have been more unpretentious than Matt Ryle, in olive sweatshirt and blue jeans, explaining the whys and wherefores of Barney’s enigmatic art. He gave a concise introduction to Cremaster 2, pointing up its reliance on Mailer’s nonfiction novel about Gary Gilmore, The Executioner’s Song. After the film, Ryle talked about the film’s Mormon and Masonic symbolism and the connections that Barney finds among killer Gilmore, Houdini, and the 1893 International Exposition, which Barney relocates from Chicago to Alberta, Canada.

Nobody could have been more unpretentious than Matt Ryle, in olive sweatshirt and blue jeans, explaining the whys and wherefores of Barney’s enigmatic art. He gave a concise introduction to Cremaster 2, pointing up its reliance on Mailer’s nonfiction novel about Gary Gilmore, The Executioner’s Song. After the film, Ryle talked about the film’s Mormon and Masonic symbolism and the connections that Barney finds among killer Gilmore, Houdini, and the 1893 International Exposition, which Barney relocates from Chicago to Alberta, Canada.

Ryle discussed some of Barney’s filming procedures too. Barney shoots plenty of coverage, with many angles to permit inserts and matches on action. He favors delicate and lustrous lighting, both in the exteriors and the interiors, many of which are studio sets. Cremaster 2 cost about $1.7 million, and it looks it. There is ambitious CGI work in the Mormon Tabernacle, and the imagery is often spectacularly beautiful, showing off the landscapes of the Bonneville Salt Flats and Canadian glaciers and enticing props like the glittering mirrored saddle and the shapely furniture that surrounds the players.

The films

For those who haven’t yet heard, Cremaster is a series of five films made between 1994 and 2002. Each one suggests a narrative, but it doesn’t give us a traditional plot. Rich in surreal details, the action presents humans and fantastic creatures, most in fairly static postures or caught in repetitive actions. They exist in vacant spaces, either colossal ones, like a blimp or the Utah landscape, or cramped chambers. Their actions and circumstances work out Barney’s private mythology, which is based on the descent of the testes during the embryo’s development in the womb. (The cremaster is the muscle that controls the contractions of the testes.) As in the paintings of Salvador Dalí (another artist interested in bodily penetration and drippy fluids), the actions we see symbolize public and historical events, but at one remove and filtered through esoteric symbolism.

Cremaster 2, which we saw last week, is one of the most accessible installments, but it’s still very opaque. It begins with imagery of stupendous horizons, some tipped vertically. We’re introduced to several figures who’ll recur: an astonishingly wasp-waisted woman, a young man and woman who seem to be consulting her for advice, Harry Houdini being trussed up for an escape, and a desperate man parked at a gas station. There are also some isolated actions, most memorably a man and woman in coitus, with her pinched waist encased in a plastic girdle. There are bees, honey, saddles, cowpokes, and petroleum jelly. The film interweaves these materials around certain emblematic actions. Crucially, the young man in his Mustang (which is coupled by fabric to another Mustang) shoots the station attendant and eventually is executed by means of a rodeo bull-ride.

Cremaster 2, which we saw last week, is one of the most accessible installments, but it’s still very opaque. It begins with imagery of stupendous horizons, some tipped vertically. We’re introduced to several figures who’ll recur: an astonishingly wasp-waisted woman, a young man and woman who seem to be consulting her for advice, Harry Houdini being trussed up for an escape, and a desperate man parked at a gas station. There are also some isolated actions, most memorably a man and woman in coitus, with her pinched waist encased in a plastic girdle. There are bees, honey, saddles, cowpokes, and petroleum jelly. The film interweaves these materials around certain emblematic actions. Crucially, the young man in his Mustang (which is coupled by fabric to another Mustang) shoots the station attendant and eventually is executed by means of a rodeo bull-ride.

I saw the Cremaster cycle at the end of summer 2003, when it ran at one of Madison’s art cinemas, the Orpheum. It was a pretty strange venue for this work, since in its heyday the old picture palace once ran Fred and Ginger movies. The Sunday I went, the entire cycle was screened in numerical order. I thought that some installments were very engaging, especially no. 5, a sort of operatic music video set in Budapest. Most of the others offered quite arresting imagery but seemed to me protracted and overbearing in their symbolism. By the end of the day my own cremaster was protesting.

Watching Cremaster 2 last Thursday, I was again absorbed by its imagery and, alas, still resisting the clanking machinery through which every figure, gesture, setting, and surreal juxtaposition called out for some Meaning, however elusive. In a tradition that runs back at least to Ulysses, Barney cooks up an interpretive feast for critics. The monstrous book treating the films and the kindred photographs and objects is, like the movies, at once luxuriant and fearsome. It starts with a ninety-page essay by Nancy Spector that explicates the films’ symbolic dimensions. Here’s a sample, from a discussion of Cremaster 4:

machinery through which every figure, gesture, setting, and surreal juxtaposition called out for some Meaning, however elusive. In a tradition that runs back at least to Ulysses, Barney cooks up an interpretive feast for critics. The monstrous book treating the films and the kindred photographs and objects is, like the movies, at once luxuriant and fearsome. It starts with a ninety-page essay by Nancy Spector that explicates the films’ symbolic dimensions. Here’s a sample, from a discussion of Cremaster 4:

The Loughton Ram, with wool dyed red and all four horns decked in ribbons of yellow and blue Manx tartan, stands at this junction—a symbol for the total integration of opposites, the urge for unity that fuels this triple race. But before the three entities—Candidate, Ascending Hack, and Descending Hack—converge, the screen goes white and silent. This blankness bespeaks the annulment of desire. (63)

Just what I’d feared: every little movement has a meaning all its own. In addition, the essay’s prose style is forbidding in its rodomontade.

With his simple diagram of the field emblem Barney libidinizes architectural space and the surrounding environs, which come to represent the externalization or materialization of inner drives (8).

Surrounding environs, as opposed to non-surrounding ones? Inner drives? What would outer drives be? As for the sentence’s meaning, couldn’t one simply say that “The emblem makes erotic drives manifest”?

Three Thoughts

Anyhow, I just wanted to use today’s blog to externalize, or materialize, or maybe even libidinize, three hypotheses about Cremaster 2.

1. It is Big Art, All-Enveloping Art. It wants to meld many systems of meaning: religion (Mormonism, Judaism), science (fetal development, geological change), history (the Columbian exposition, Gilmore’s killing spree), literature (Mailer’s novel), and more. In this it belongs to a tradition of omnivorous artworks, from Ulysses and Finnegans Wake down to Pynchon, Syberberg, and Greenaway. The artist as demiurge, creating a master-scheme whose correspondences radiate out to many cultural systems: Eisenstein may have been the first filmmaker (in his unmade Moscow project) to attempt something on this scale, but he wasn’t the last.

At the same time, Postmodernist art characteristically absorbs these vast systems in an oblique way, through roundabout citation. I think of Robert Wilson’s Theatre of Images and his collaboration with Philip Glass on Einstein on the Beach. In a rarefied arena, obscure or trivial actions are played out, mysteriously referring to historical events or other artworks. If you don’t know the role of trains or violins in Einstein’s life and thought, you’re arrested by the pure juxtaposition. If you catch the cites, or more likely do your outside reading, you’ll discover an associative logic binding the tableau together. The same strategy of obscure allusion is on view in Glass’s theatre piece about Muybridge, The Photographer.

Something similar happens with Cremaster. As Matt Riley pointed out, Barney’s tableaus can tease you into doing research to find connections, however tenuous, among Gary Gilmore and Harry Houdini, or the Mormons and a Sinclair gas station. But to his grand synthesis, Barney has added autobiography. As in the work of Dalí, Cocteau, and Joseph Beuys, veiled references to public history are mixed with wisps from the artist’s life—in this case, an athletic career and modeling in New York. Beuys’ animal fat (recalling his purported plane crash during World War II) finds its equivalent in Barney’s petroleum jelly, used to keep his shoulder pads flexible during a football game.

Something similar happens with Cremaster. As Matt Riley pointed out, Barney’s tableaus can tease you into doing research to find connections, however tenuous, among Gary Gilmore and Harry Houdini, or the Mormons and a Sinclair gas station. But to his grand synthesis, Barney has added autobiography. As in the work of Dalí, Cocteau, and Joseph Beuys, veiled references to public history are mixed with wisps from the artist’s life—in this case, an athletic career and modeling in New York. Beuys’ animal fat (recalling his purported plane crash during World War II) finds its equivalent in Barney’s petroleum jelly, used to keep his shoulder pads flexible during a football game.

These films assign you homework. Fortunately we have cheat sheets. Like Joyce and Greenaway, Barney has explicated his work’s public and private mythology. The bare bones are laid out on the cycle’s official website. Since free-associative interpretation is the modus operandi of most academic criticism, highly associative art like this has the effect of playing to commentators’ strengths. The Cremaster book includes not only Spector’s blow-by-blow explication but also an imposing glossary, with entries running from anus-island to zombie, illuminated by snippets from fiction and literary theory. Barney will keep critics very busy for a long time: Some Cremaster scenes are as iconographically dense as a mannerist Annunciation.

2. Stylistically the films go down like milkshakes. There may be less here than meets the eye, but what meets the eye is pretty gorgeous. The installments have the smooth cutting and meticulous compositions of Cocteau’s Orphée. Their limpid camera movements, swooping helicopter shots, and luscious color design could pass muster in a Hollywood production. The films flaunt their production values, and you could argue that this can make them attractive to young people who might find rougher-edged or lower-budget experiments by Ernie Gehr or Lewis Klahr harder to take. Though the shots run moderately long (averaging 9-10 seconds in the films I clocked), the insistence on close-ups, arcing camera, and slow zooms recalls that cluster of current Hollywood techniques I’ve called “intensified continuity,” and this helps contemporary audiences concentrate on the tableaus.

Another user-friendly aspect, touched on in the panel discussion: The echoes of the horror film. We’re on edge from the start of Cremaster 2, with Jonathan Bepler’s rumbling score rising dissonantly as the bleeding logo hurtles out at us, looking like a thorny torture device. The dripping nose and bolted mouth of Baby Fay la Foe, the bees swarming over the thrash-rock musician as he makes a call, and the bloody body of the gas station attendant offer us some fairly pure horror-movie iconography. It could just as easily be called Creepmaster.

Another user-friendly aspect, touched on in the panel discussion: The echoes of the horror film. We’re on edge from the start of Cremaster 2, with Jonathan Bepler’s rumbling score rising dissonantly as the bleeding logo hurtles out at us, looking like a thorny torture device. The dripping nose and bolted mouth of Baby Fay la Foe, the bees swarming over the thrash-rock musician as he makes a call, and the bloody body of the gas station attendant offer us some fairly pure horror-movie iconography. It could just as easily be called Creepmaster.

3. Might not this be the Artworld’s parallel to a Hollywood blockbuster franchise? The Cremaster films are designed chronologically, like sequels are. They have spawned fan videos and fan music. They spin off ancillaries, such as the souvenir volume I’ve already mentioned, along with T-shirts, baseball caps, and coffee mugs. Since this is the Artworld, though, the real ancillaries are the photographs, drawings, and sculptures that tour on exhibit. In early 2004 one photo triptych from Cremaster 2 fetched over $186,000. The film has become a precious object in itself. Only ten institutions, we’re told, can acquire prints, and the series won’t be released on DVD.

Those who think that many contemporary museum shows are really about the shop will find strong evidence here. In today’s art market, Cremaster might be the gallery scene’s equivalent of the summer megapicture, the project that by virtue of its monumental scale and production values generates income at many levels indefinitely. Again, the showmanship of that adroit impresario Dalí comes to mind.

From this perspective, Barney becomes the equivalent of an A-list movie producer or director, overseeing a platoon of artisans like Matt Ryle who bring his vision to life. Cremaster reminds us of the ambiguities in the word studio, applied both to moviemaking and the fine arts. For hundreds of years successful painters have in their studios divided the labor of artmaking, planning the overall design and assigning juniors to fill in bits before the supervisor added his distinctive touch. Warhol revived this in ironic mode with his Factory, often by denying he had a touch by leaving all the work to others. But Warhol’s films struck observers as crude and offhand, while Barney has produced something bold, polished, and overwhelming. If Warhol was the Roger Corman of the Artworld, Matthew Barney may be its Jerry Bruckheimer.

PS: In correspondence Professor Jim Kreul has called my attention to an article that anticipates my third point: Alexandra Keller and Frazer Ward, “Matthew Barney and the Paradox of the Neo-Avant-Garde Blockbuster,” Cinema Journal 45, 2 (2006), 3-16. It considers in detail the relationship of Barney to performance art as well.