Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929)

DB here:

The Donovan Affair was Columbia’s first all-talking picture, and Frank Capra’s as well. We discussed it a little in an entry devoted to a Cinema Ritrovato retrospective of Capra’s films. The film lacked, and still lacks, a soundtrack, which may be lost.

The Donovan Affair is an unusually fluid early talkie, and that led me to speculate we might be seeing the silent release version. Wrong! It really does survive only as a sound film without a soundtrack; the Library of Congress print I studied last month has a leader labeled “synchronized version.”

The clunky plot didn’t improve on repeated viewing, but the film did teach me some things about those transitional years 1928-1932, when filmmakers were figuring out how to make a sound feature. I thought I’d share some of those findings with you today.

But I must warn you that there’s one big spoiler coming up. I tell you whodunit. It’s necessary to make a point, but I will warn you just before the offending paragraph, so you can skip if you wish.

Blood-spattered footlights

Murder ran wild on the Anglo-American stage of the 1920s. While melodramas of love and betrayal waned, mysteries rose in popularity. There were plays about gangsters, trials, and domestic homicide. There were comedies of lethal intrigue in spooky settings, like The Bat (1920), The Last Warning (1922), and The Cat and the Canary (1922). A little more seriously, in response the rise of the genteel British detective novel (Christie, Sayers, Allingham et al.), there emerged plays that dumped murder into society drawing rooms.

You know the format. The setting is typically a mansion, with portraits, plush salons, and an impressive library. The victim, usually a bounder, deserves killing. The suspects are both high and low: businessmen, doctors, lawyers, dowagers, flappers, playboys, ne’er-do-wells, gangsters, and servants. Into this ménage steps a police inspector, often with a bumbling assistant, who will more or less skillfully reveal the culprit. In the process, though, someone else is likely to die.

The prototype is Bayard Veiller’s play The Thirteenth Chair (1916), but by the 1920s Britain and the US produced a host of popular and well-reviewed drawing-room mysteries: The Nightcap (1920), In the Next Room (1923), The Creaking Chair (1924), Interference (1927), The Man at Six (1928), The Clutching Claw (1928), and The Canary Murder Case (1928). The most famous entry in this cycle is probably Patrick Hamilton’s Rope (1929), which stands out because it presents the crime from the killers’ viewpoint. The question isn’t “Who did it?” but “Will they get away with it?” Rope’s “inverted” structure (no pun intended; it’s a trade term) was anticipated by A. A. Milne’s The Fourth Wall (1928).

Owen Davis’s play The Donovan Affair (1926) fits snugly into this cycle. The action starts with Inspector Killian and his assistant Carney ushering the suspects into the Rankin family library. The rakish Jack Donovan has been murdered at a birthday dinner. The circumstances are odd: To demonstrate a glowing ring Donovan wears, the lights were turned out. In the darkness, he was stabbed with a carving knife.

Most of those at the table have good reason to kill Donovan. He was having affairs with married women and had an eye on Rankin’s daughter Jean, whom David hoped to marry. The first act is centered on exposition that emerges from Killian’s questioning of the guests. One, Horace Carter, comes forward to declare he knows who the killer is, because the victim’s missing ring was slipped into his pocket. Killian doubts that the ring could have been visible, and so the lights are switched off a second time as a test. Bad idea: When the lights come back on, Horace has been stabbed with the same knife. Score one for law and order. Later one character will shoot another as Killian looks on.

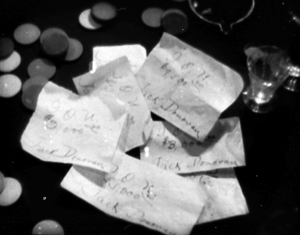

The next two acts expose more motives, lay false trails (David has brought a gun to dinner and has blood on his cuff), and string out physical clues, including a fake ring and some threatening letters to Donovan. In frustration, Killian leaves the suspects to pool their information, in hopes that they’ll discover the killer. Once more the lights are put out to allow the culprit to replace the ring and a missing letter. The killer is revealed, and there’s a struggle in semidarkness. Killian and his men burst in to seize the guilty party.

Among all this claptrap, the blackout gimmick is worked very hard. Bayard Veiller’s Thirteenth Chair had staged a stabbing in a dimly-lit séance, and Davis himself had let the electricity fail in The Haunted House (1924). The blackout-covering-a-killing would be reused in The Spider (1927). The Donovan Affair justifies the device through the luminous ring. In plot terms, it’s another red herring, but it plausibly motivates darkening the stage during the murders. The effect seems to have come off.

The audience found itself frequently strung almost to the endurance limit, and now and then a voice from the crowd would beg a relentless actor not to turn out those lights again. For it was generally in the darkness that stabbings, shootings and assorted mayhem would stalk through the play.

It must have been riveting to see the ring (a green-tinted flashlight) floating around the darkness. Capra’s film is at pains to reproduce this signature effect, but with some differences.

The screenplay subtracts some of the characters and adds a sinister caretaker and Porter, a gambler to whom Donovan owes money. The plot begins well before the crime, with an opening that establishes Porter among his cronies. A second scene shows Donovan brushing off Mary, the Rankin family maid; in the play their liaison is revealed very late. Then guests gather for the birthday dinner, and after some salon byplay they sit down to eat, with Donovan demonstrating the power of the cat’s-eye ring. In the darkness he’s murdered.

A title, “One hour later,” introduces the main stretch of the film, which corresponds more closely with the play’s action. Inspector Killian arrives and sizes up the suspects. Most of the play’s clues emerge, with suspicion scattered around freely.

Like the play, the film is built around blackouts showing off the wandering ring, but now these are motivated as reenactments of the crime. Killian puts Porter in Donovan’s seat, and in the darkness he becomes the second victim. After more intrigue, Killian demands another go-round, and this time the killer is exposed.

The film’s blackout scenes run 36 seconds, 42 seconds, and about 100 seconds for the climax. This last scene varies the treatment by showing some silhouettes.

These scenes feel surprisingly protracted: 30 seconds is a long time on the screen. Likely there would have been dialogue and sound effects, as there are in the play’s blackout intervals.

Here’s the paragraph with the spoiler. In both play and film, the butler Nelson is revealed as the murderer. (At this point in history, having hired help commit the crime wasn’t yet out of bounds.) Nelson is in love with Mary, whom Donovan has seduced. The film hints at this in a way that the play doesn’t. Mary is introduced early as Donovan’s mistress, Nelson seems to have eyes for her, and during a test to see if any woman’s handwriting matches that on a telltale letter, he lingers solicitously over Mary.

Variety praised Capra’s film as well-constructed and surprisingly funny, chiefly because of a whimsical old couple added to the ensemble. Capra claims that The Donovan Affair taught him to add doses of comedy as much as possible: “Comedy in all things.” Actually, though, Owen Davis claimed that he was teasing the genre in his original. “The Donovan Affair was, naturally, a success, although I am, I think, the only one who knows that it was as deliberate a burlesque as The Haunted House had been.”

Opening up the proscenium

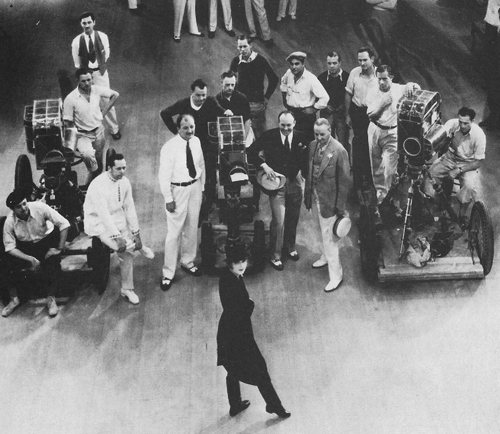

A posed shot of the multiple-camera teams for Sunny (1930).

In his autobiography Capra regarded The Donovan Affair as a turning point in his career. While complaining about the constraints on sound cameras, he regarded the film as “the beginning of a true understanding of the skills of my craft: how to make the mechanics—lighting, microphone, camera—serve and be subject to the actors.” To my way of thinking, what he did within the confines of early talkies was inject some of the pictorial fluidity and impact on display in the silent cinema. The Donovan Affair is a lot less pictorially stilted than most of the 1929 American films I’ve seen.

Like many early talkies, the film relies heavily on multiple-camera shooting of the sort still used in TV comedies and soap operas. For this film, according to Joseph McBride, five cameras were used. The range of coverage allowed for continuous sound recording while preserving the option of analytical editing. While one camera recorded a wide framing, a long lens could scoop out a closer view without moving that camera into the space.

So when Mary calls on Donovan in the second scene, we can see her arrive in a long-lens mid-shot, then we can see Donovan’s reaction in a long shot. Mary comes forward and a third camera picks them up in a two-shot.

The technique permits smooth matches on action, as when Mary turns her head in a medium shot and leaves in the background of the master shot.

But it’s also clear that multiple-camera shooting allowed for alternative takes. The mismatches we can detect across some cuts suggest this. During continuous dialogue, Lydia’s arm is up in one shot and down in the next.

Capra claims that Columbia allowed him to print only one take, but he got around this by not slating his shots. He simply let the camera run and replayed the action, sometimes several times. This allowed actors to improve their performances in a fluid process. CApra wound up with only one take number, out of which he could pick the take he wanted. This tactic might explain disparities of figure position.

Multiple-camera shooting could yield some awkwardness, especially when shot scale wasn’t adjusted. Here’s an interesting example showing Jean’s quarrel with her stepmother Lydia. As Lydia crosses in front of Jean, the match cut on my second frame below creates a little bump by not sufficiently changing the angle and figure size. The slight pan following the women accentuates the disparity.

A jerky cut like this would be very rare later in the 1930s, as it is today. As recording technology improved, Hollywood would move back to single-camera shooting for most scenes, and shot scales were more exactly planned and executed.

If multiple-camera shooting feels a bit theatrical, it’s because it surrenders a degree of freedom in camera placement. We always seem to be watching things from outside a proscenium, even when items are enlarged. I think that the early talkies’ habit of starting with a flamboyant camera movement, as in Sunny Side Up (1929) and The Broadway Melody (1929), was a way of saying, “Don’t worry, this is still cinema.” Capra follows this habit by beginning on a close view of a pile of Donovan’s IOUs and then tracking back very far to set his first scene among the gamblers.

The film’s second “act” starts with a comparable flourish. A long shot of the library shows Carney bustling toward the offscreen front door in the background. The camera tracks in and waits for him to return.

Presumably we would be hearing him greeting Inspector Killian offscreen, but the frame is empty for about fifteen seconds. Then Carney and Killian stride in, and the camera pulls back to something like the initial master framing.

Another way to add fluidity was to insert shots that don’t require lip synchronization. Cutaways to objects or reaction shots could be inserted into the dialogue-laden stretches. For example, Nelson and Mary peer into the library to watch the guests, and Ted Tetzlaff’s cameras give us two shots from positions different than we’ve seen so far.

More boldly, after Donovan is killed, Capra gives us not only a shot of Mrs. Lindsey wailing but brief close-ups of Jean’s and Lydia’s reactions.

These two shots are only 32 and 36 frames respectively, harking back to the punchy montage of silent cinema, and they stand out by contrast with the extreme long-shots around them.

Similarly, you have to think of all those subjective POV shots in 1920s silent films when we watch Killian survey the suspects. As he talks with Rankin, he scans them right to left in a series of POV shots, including one longish, zigzag pan. Here are some extracts.

The end of the pan shot shows Lydia shifting her gaze from Killian to her husband, off left. We then cut to her husband and Killian, who’s just finishing his scanning of the suspects. Her gesture cast suspicion on her; after all, she’s hiding her affair with the dead man.

Most ambitious of all is Capra’s handling of the dinner table situation. Smoothly integrating singles and two shots of characters around a table was one of the triumphs of classical Hollywood style in the late 1910s. Matching character positions and eyelines from shot to shot became part of every director’s craft. Capra adapts talking pictures to these constraints in a flow of shots that include dialogue and keep all characters’ relationships clear and consistent while picking out important details and reactions.

For example, when Donovan talks with Mrs. Lindsey, we get her husband’s glare as he watches from across the table.

Here the proscenium is broken. Instead of covering the action from outside, now the camera penetrates space and can take up a variety of angles among the characters.

This camera ubiquity can be exploited to dramatize the murder weapon. A master shot shows the dinner party, with Rankin at the head of the table and his wife Lydia at the foot, turned from us.

Mary brings the roast and the carving knife to the table. Cut in to Mary lifting the knife, which glints.

Donovan flinches as the reflection dazzles him. Cut to Lydia, from the foot of the table, saying, “Mary,” and looking down the table to where Mary would be.

We’re in a sort of triangular space—Mary-Donovan-Lydia—and the relationships are reaffirmed when a return to the earlier setup shows Mary responding to Lydia’s look.

The dialogue continues within these shots. Capra’s changing setups must have required quite a bit of effort in 1929, what with cameras in booths and the pressures to stick with continuous multi-camera takes. But, reviving silent-film table coverage, he gives us what would be one conventional way to handle such an action in the 1930s.

There are other felicities in the film, but I think I’ve said enough to indicate how it’s an enlightening transitional work. Tied to the multi-camera technique for most of its running time, Capra breaks away for significant stretches. He found a way to give camerawork and cutting some moments of the sort of fluidity that would pervade Hollywood in the 1930s.

Capra wasn’t the only major director to cut his talkie teeth on adaptations of stage thrillers. Hawks made The Criminal Code (1931) from a 1929 prison drama, while Hitchcock based Blackmail (1929) and Number Seventeen (1932) on popular plays from 1928 and 1925. Film mysteries would change in the 1930s, with sophisticated detective comedies like The Thin Man and adaptations of the adventures of Charlie Chan and Perry Mason.

Creaky though it might seem in later decades, the manor-house murder would remain a reference point. On stage its premises were given a new twist in Christie’s The Mousetrap (1952), enhanced with social criticism in J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls (1945), and parodied in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1962). You can argue that the provincial procedurals with a British accent (Wexford, Midsomer Murders, Inspector Morse, and so on) grow out of the spillikins-in-the-parlor tradition, but shifting the viewpoint to that of the detectives.

Thanks to Lynanne Schweighofer, Zoran Sinobad, and Mike Mashon of the Library of Congress and Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach of our Cinematheque for arranging my viewing of The Donovan Affair. Thanks also to Ben Brewster for discussions of the film and 1920s theatrical practice.

A fleshed-out synopsis of the film was published at the time.

Bruce Goldstein had the excellent idea of adding live performers to screenings of The Donovan Affair. He details his efforts to find the original dialogue in this TCM article.

Ray Collins fans may be interested to know that in the stage version he played the butler–described in the script as “really the only acting part in the play.”

My quotation about rapt audiences for the stage version comes from the review, “’The Donovan Affair’ Thrills in Mystery,” The New York Times (31 August 1926), 15. Quotations from Capra are from the first edition of his autobiography, The Name above the Title (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 105. Joseph McBride has written the most comprehensive and probing biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

In his autobiography Owen Davis remarks that the failure of The Haunted House, a “burlesque mystery melodrama” impelled him to write The Donovan Affair. That was a play that “could hardly be accused of not being mysterious enough, and one that actually dripped with blood and missed no trick at all of the tried and true tricks of mystery story writing from Gaboriau through Poe and Doyle and Anna Katherine Green and Mrs. Rinehart, even taking in the tricks of the present, and very skillful, crop of hard-boiled detective story writers who were at that time printing their first compositions on a slate in some primary school.” See My First Fifty Years in the Theatre (Boston: Baker, 1950), 94-95.

My exploration of theatrical thrillers has been aided by Amnon Kabatchnik’s two excellent reference books: Blood on the Stage: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire, 1900-1925 (Scarecrow, 2008) and Blood on the Stage, 1925-1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection: An Annotated Repertoire (Scarecrow, 2010).

As ever in such matters, Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website offers background information and critical discussion of authors, periods, and conventions.

On multiple-camera shooting in early sound film, see Chapter 23 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. A good primary source is Karl Struss’s article “Photographing with Multiple Cameras,” TSMPE XIII, 38 (1929), 477-478.

The Donovan Affair (1929).

Who got played? A guest post by Jeff Smith on THE PLAYER

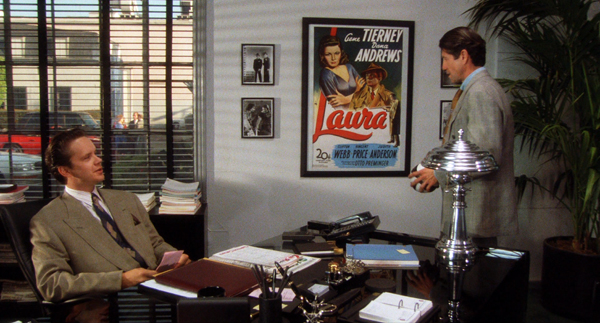

The Player (1992).

Jeff Smith, our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction just recorded an installment of our Observations on Film Art series for the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck. Here’s a supplement to that. –DB

In my installment, focusing on genre play in The Player, I discuss Robert Altman’s film in relation to two important traditions in Hollywood cinema: crime thrillers and films about filmmaking. As anyone who knows Altman’s other films would expect, The Player toys with the conventions of both genres in a number of different ways.

As I note in the video, The Player was received as something of a comeback film for Altman. It augured a resurgence in the director’s career that ultimately produced such late masterpieces as Short Cuts and Gosford Park.

Today, I sketch out some additional ideas about The Player’s use of genre conventions. I hope to shed light on some other connections to the crime thriller that I didn’t discuss in the video. I also hope to show just how unusual the film is in this context. Spoilers ahead, not only for The Player but for the novel and film of The Ax.

Will the real Griffin Mill please stand up?

In Reinventing Hollywood, David notes that there are usually four sorts of characters involved in a crime thriller plot: victims, lawbreakers, forces of justice, and more or less innocent bystanders. Filmmakers customarily organize the film’s narration around one or more of these character roles. Typically, a cascade of further choices flows from this initial decision about whose perspective forms the focal point of the story.

In The Player, much of the narration is restricted to the knowledge of the protagonist, Griffin Mill. The film includes a few scenes where Griffin is not present, like the one where the studio’s management awaits his arrival at a meeting. That, in itself, is not unusual. Many thrillers, like Chinatown or The Ghost Writer, employ similar tactics. What is slightly unusual is the fact Griffin takes on two of the typical character roles in the crime thriller as both victim and lawbreaker.

Griffin is a suit, and as a studio functionary he doesn’t immediately engender audience sympathy. Our first glimpse of Griffin shows him listening to pitch sessions. His questions to the people proposing new film projects are glib and capricious, representing the worst aspects of Hollywood commercialism.

Yet The Player does marshall some sympathy for Griffin as the victim of a stalker. Every time Griffin finds a postcard in his mail or on his car, it reminds us that he might be in mortal danger. After the stalker plants a venomous rattlesnake in Griffin’s passenger seat, we can’t believe the threats are empty.

Any sympathy that Griffin garners as a result of this psychological warfare is mollified, though, when the victim becomes victimizer. As Griffin later explains to June, his job is to tell people “no” more than a thousand times each year. Griffin believes that one of these rejections is the reason for the threatening postcards he receives. But he tragically miscalculates in targeting aspiring screenwriter David Kahane as the likely suspect.

Griffin contrives a meeting with Kahane at a Pasadena movie theater, and having bumped into him, tries to make amends. Yet Kahane recognizes that he is being pimped. This leads to a shouting match in a parking lot with Kahane threatening to ruin Griffin’s reputation. And when Kahane accidentally knocks Griffin over with his car door, Griffin reacts with rage, grabbing the screenwriter’s head and banging it repeatedly against the lot’s concrete surface. Although it seems clear that Griffin was acting on impulse, he’s nonetheless crossed a line that separates victims from perpetrators.

More importantly, Griffin’s violent action complicates the viewer’s allegiance to him. Altman establishes a dramatic context in which the motivations for Griffin’s crime seem completely understandable. Yet whatever sympathies viewers might have for Griffin are muddled by his creepy romantic interest in Kahane’s girlfriend; his cruel treatment of Bonnie, his current partner; and the general smarminess he exudes as a successful but shallow executive. Crime thrillers often ask audiences to sympathize with heels. There’s nothing that Griffin does that is inherently evil, but there’s nothing to really like. It’s less about his crime and more about his slime.

Griffin’s passage from victim to lawbreaker also alters the typical thriller plot. At the start of the film, Griffin himself functions as the investigative agent, trying desperately to figure out who is threatening him. Once Griffin becomes a suspect himself, though, that line of action halts, and the Pasadena police’s investigation of Kahane’s death springs up in its place.

This shift in the direction of the plot doesn’t really change the film’s pattern of narration. We remain as ignorant of the police’s activities as Griffin is. What does change are the stakes of the narrative. Instead of eliciting curiosity and suspense about Griffin’s stalker, we now wonder whether he’ll ever be brought to justice for Kahane’s death. Despite its strong connections and frequent allusions to crime fiction, The Player is not so much a whodunit as it is a will-he-get-away-with-it.

They smile in your face, all the time they want to take your place….

Besides blurring the boundaries between Griffin’s role as both victim and lawbreaker, The Player falls into a specific subgenre of crime fiction: the corporate thriller. Since, the corporate thriller is mostly defined by its setting, it blends pretty easily with the typical thriller plots and characters.

Like the spy thriller, the corporate thriller can focus on protagonists engaged in industrial espionage, as we see in Duplicity, Demon Lover, or Paycheck. Christopher Nolan’s Inception blends the plot mechanics of these corporate espionage thrillers with science fiction tropes to provide a narrative frame, but then embeds elements of the heist film within it.

Like the political thriller, the corporate thriller might also focus on the backroom deals and machinations that enable the protagonist to move up the company ladder. A film like Disclosure is a paradigm case. But even romantic comedies or prestige dramas can borrow elements from it. (Think Working Girl and Glengarry Glen Ross.)

More commonly, though, corporate thrillers feature elements drawn from the crime thriller. The roots of this approach to the genre stretch back a long way and can be found in both literary and cinematic antecedents. Some plots, for example, follow investigations that expose corporate malfeasance. Others focus on murders committed within a corporate environment, as in Dorothy Sayers’s novel Murder Must Advertise and Kenneth Fearing’s novel (and film) The Big Clock and in more modern instances like Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun and John Grisham’s The Firm. Other corporate crime thrillers, like Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (below) and Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer, involve serial murders in white-collar environments.

The corporate crime thriller enables writers and filmmakers to explore thematic parallels between the acts of brutality and violence committed by individuals and the cutthroat tactics employed by business institutions. The plots of many gangster films center on rival mobs battling for competitive dominance in black market trades. Such conflicts often seem like a logical extension of the laissez-faire principles that undergird capitalism. Corporate crime thrillers tread similar thematic territory. They sometimes suggest that the personality traits that make for good business executives and titans of industry are the same ones that produce sociopaths and serial killers.

The Player presents the familiar corporate-thriller rivalry, as Griffin works behind the scenes to outmaneuver Larry Levy. For example, Griffin momentarily ponders using Larry’s admission that he attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings as a way of embarrassing him within the company. Larry quickly undercuts this strategy, though, when he states that he just goes to the meetings because they are a great place to network.

Even more telling is Griffin’s efforts to saddle Larry with a loser project, Habeas Corpus. Midway through The Player, Griffin makes a deal with Andy Civella and Tom Oakley at a Los Angeles restaurant. The next day, he convinces his boss to greenlight the project with Larry as producer, knowing that Tom will likely prove difficult to work with and that his plan to use unknown actors has disaster written all over it. Larry, though, has the last laugh when we get a sneak peek of Habeas Corpus at film’s end. Not only does it have big stars in Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis. It also has the kind of happy ending that the pretentious Tom claimed was too Hollywood when he pitched the project. It turns out Tom cares more about the results of preview screenings than he does the purity of his artistic vision.

Not surprisingly, Altman doesn’t give us a wholly straightforward version of the corporate thriller. In a reflexive and ironic touch, Griffin’s successful ascent to studio boss seems to be secured by the same mysterious stalker who’d been taunting him at the start of the film. In a phone call, the stalker pitches Griffin the plot of the film we’ve just been watching, using his knowledge of Griffin’s crime to leverage his project into development. Here we see Altman slightly reframing the genre’s thesis about the relationship between crime and business. Griffin’s pact with his blackmailing stalker is simply a mildly illicit version of the sorts of quid pro quo arrangements upon which thousands of business deals are made.

If Griffin’s efforts to forestall a rival evoke the political thriller, then his killing of screenwriter David Kahane connects The Player to the corporate crime thriller. Once again, Altman deviates from some of the conventions. The crime doesn’t take place inside a corporate setting, as in Rising Sun and Murder Must Advertise. Griffin kills Kahane in the very public space of a Pasadena parking lot, with film noir overtones.

Similarly, Griffin’s victim is not a colleague, co-worker, subordinate, or client. Rather, Kahane is someone with whom Griffin has had minimal contact, a name plucked almost randomly from a directory of screenwriters in order to jog Griffin’s memory. Consequently, Griffin’s motives for confronting Kahane seem quite different from the culprits in other corporate crime thrillers. More often than not, the murderers in these other stories fear job loss or try to silence others in an effort to cover up some smaller crime or bungled action. Griffin’s actions with Kahane spring from fear about threats to his physical well-being, not from threats to his continued employment. (The latter is Larry’s role.)

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Some of The Player’s deviations from more conventional corporate crime thrillers come into relief if we compare it to Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, a purer example of the genre. The Ax tells the story of Burke Devore, a production line manager recently downsized out of his job at a paper company. Still unemployed after eighteen months, Burke creates a phony job advertisement, and then begins to kill off the seven applicants he believes have the same qualifications he does. His plan is to eliminate all of the other unemployed middle managers in the paper business so that his resumé will land at the top of the pile when a new factory opens in his area.

Like Altman, Westlake has some fun with his central conceit. Just as The Player includes faux film clips and rushes as a means of satirizing Hollywood production practices, The Ax incorporates fictional resumes that tweak jobseekers’ business-speak. What makes Westlake’s social criticism in The Ax so resonant, though, is the utter banality of Burke’s ambitions. He doesn’t aspire to the garish lifestyle we see displayed by Tony Montana or Jordan Belfort in Scarface and The Wolf of Wall Street respectively. Instead Burke just wants to return to his modest middle-class lifestyle and to the dignity that a decent job afforded him. Serial murder just seems like the simplest way to achieve that.

As this comparison suggests, one of the things that makes The Player somewhat unusual as a corporate crime thriller is its play with character motivation and point of view. Facing threats and intimidation, Griffin looks more like the target of a crime than a perpetrator. In corporate thrillers, the lawbreaker is more likely to be somewhere in the middle of the corporate ladder, like Burke, than at the top of it. Moreover, although his actions are motivated by a strange combination of both vanity and insecurity, Griffin more or less stumbles into the crime he commits rather than coolly plotting it the way Burke does.

Despite these differences, The Player and The Ax share an important feature that markedly deviates from the crime thriller as a whole. Both Griffin and Burke get away with it. The plots of most crime thrillers resolve in ways that balance the scales of justice. The bad guys are usually either arrested or killed after climactic confrontations with law enforcement. But this doesn’t always happen. Burke, Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, and Dorine in Office Killer escape punishment. Even though Jordan Belfort is arrested in The Wolf of Wall Street, he gets a slap on the wrist for his crimes.

Perhaps this aspect of the corporate crime thriller reflects the cynicism and amorality that pervades the genre. After all, if your belief is that most corporations get away with murder in a figurative sense, then it’s not hard to accept this idea when it occurs in fictional contexts in a literal sense.

Still, in the case of The Player, the Pasadena police’s failure to prove their case against Griffin Mill may reflect a meshing of both authorial and generic tendencies. When Griffin embraces June in the stylized happy ending of The Player, it quite deliberately parallels the tacked on happy ending of Habeas Corpus we’ve seen just moments earlier. The dialogue Griffin exchanges with June amplifies the similarity between these scenes. When June asks, “What took you so long?”, Griffin responds, “Traffic was a bitch.” These are the exact same lines exchanged by Julia Roberts and Bruce Willis in Habeas Corpus. By allowing Griffin to get away with it, The Player’s “up” ending sharpens Altman’s critique of Hollywood convention, and allows him to subvert the kinds of mainstream genre filmmaking he’s long detested.

Both allusive and elusive: Comparing The Player to Hollywood Story

One of the other topics I discuss in my video essay on The Player is the way the film pays homage to various aspects of Hollywood tradition. Much of this is bound up with its satire of commercial filmmaking. But it also strengthens the film’s relation to the crime thriller. Throughout The Player, Altman makes reference to Hollywood’s past in multiple ways. Celebrity cameos, film posters, and production stills populate the mise-en-scene. The characters also frequently mention older film titles in dialogue.

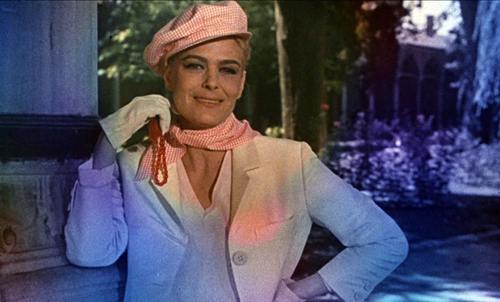

Perhaps the most interesting allusion in The Player involves a poster of Hollywood Story that hangs in Griffin’s office. The latter is a 1951 film noir directed by William Castle, who later became famous for his use of outrageous gimmicks in the production and promotion of horror films. For The Tingler, Castle supervised the installation of devices that would vibrate theater seats, anticipating today’s 4DX Theater Experience in places like Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Orlando.

Hollywood Story dramatizes the efforts of film producer Larry O’Brien to develop a project around the unsolved murder of silent film director Franklin Ferrara. O’Brien hires one of Ferrara’s old scenarists to write the script. He also develops a close relationship with Sally Rousseau, the daughter of one of Ferrara’s biggest stars. Once the project is announced, O’Brien finds himself the target of an assassin’s bullet. He surmises that his assailant is trying to prevent the case from being reopened. And as Sally reminds O’Brien, he doesn’t have an ending to his movie is he can’t determine the killer’s identity. O’Brien, thus, sets out to solve the crime, bringing closure to one of the biggest scandals in Hollywood’s history. Hollywood Story offers an even better synthesis of The Player’s mixture of industry exposé and crime film story beats. O’Brien’s lone wolf investigation is treated as being a necessary stage of project development.

If the Franklin Ferrara story sounds vaguely familiar to you, well….it should. Hollywood Story offers a fictionalized account of the unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor, who was shot to death in his bungalow in the wee hours of a February night in 1922. (David blogged about the crime here.) The subsequent investigation of Taylor’s death ensnared some of the industry’s biggest stars of the period. Mabel Normand’s reputation was tainted by her association with Taylor and by reports of drug use. She took a brief hiatus from filmmaking because of the scandal, but never completely recovered from it. Normand later died of tuberculosis in 1930 at the tender age of 37.

As a fictionalized account of a notorious unsolved crime, Hollywood Story anticipates more modern thrillers that provide speculative solutions to real-life murders. Zodiac and The Black Dahlia are prime examples, as are any number of Jack the Ripper films. Hollywood Story’s approach was not unprecedented. James M. Cain based Double Indemnity on the Ruth Snyder case that was fodder for New York tabloids in the late 1920s. That said, Taylor’s death lingered for decades in popular memory in a way that the Snyder case did not.

What are we to make of The Player’s citation of Hollywood Story? On the one hand, viewers might well notice the almost immediate parallel of our “film execs in jeopardy” storylines. Just as Griffin is stalked by an unknown assailant, so, too, is Larry the target of a shadowy aggressor. Moreover, Hollywood Story, along with Sunset Boulevard, might well be an inspiration of one of The Player’s most interesting features: its intermingling of real life stars with fictional characters. Hollywood Story includes cameos by Joel McCrea and several noted performers of the silent era, such as William Farnum, Francis X. Bushman, and Betty Blythe (below). The Player pushes this aspect of Hollywood Story to extremes, containing plentiful cameos by Cher, Jack Lemmon, Burt Reynolds, Lily Tomlin, Susan Sarandon, and other A-listers.

In several other respects, though, The Player seems like an inversion of Hollywood Story with Griffin emerging as a more venal counterpart to the latter’s crusading producer, Larry. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s investigation actually produces results. This strongly contrasts with Griffin’s guesswork, which, as the result of a tragic mistake, leads to David Kahane’s death in a Pasadena parking lot. In Hollywood Story, Larry’s blossoming romance with Sally furnishes the standard double plotline commonly found in classical cinema. In The Player, though, Griffin’s interest in June seems genuinely sleazy. It also exacerbates the Pasadena police’s doubts about Griffin’s alibi, making him their prime suspect. Finally, the revelation of screenwriter Vincent St. Clair as Franklin Ferrara’s killer provides closure both to Larry’s script and to Hollywood Story itself. In contrast, none of the crimes presented in The Player are really solved. Griffin is blackmailed into greenlighting a project during the film’s epilogue, but the audience never learns the identity of the mysterious stalker. Similarly, although the Pasadena police believe that Griffin is guilty of murder, the botched lineup ensures that he will go free and that David Kahane’s death will remain an unsolved crime. In an odd way, The Player returns to the narrative roots of Hollywood Story. The fate of Kahane, our aspiring screenwriter, seems destined to mirror that of poor William Desmond Taylor, our successful silent film director.

A thriller with no thrills

I’ve sketched out a number of different ways in which The Player relates to the basic conventions of the crime thriller, but all of this is ultimately, in the parlance of the genre, a red herring. This is because The Player is that rare bird: a crime film that engenders relatively little curiosity about its solution and even less suspense about the fate of its protagonist.

This is largely because Robert Altman mostly uses crime film conventions as scaffolding for the things that really interest him: quirky characters, digressive dialogue, and a loose, improvisatory feel to the film’s performances. At its heart, The Player is a comedy that draws upon crime film conventions in much the way Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye does.

Compare, for example, each film’s tweaking of the genre’s standard interrogation scenes. In The Long Goodbye, Detective Farmer’s tough questioning of Philip Marlowe is punctured by the latter’s goofy responses. At one point, Marlowe uses the ink from his fingerprinting procedure like it was the “eye black” used by an athlete. Later, he smears the ink all over his face and sings “Swanee” in a mocking homage to Al Jolson in blackface. Similarly, in The Player, the Pasadena police’s interrogation of Griffin is disrupted by Detective Avery’s disarming exchange with her partner about tampons, her mangled pronunciation of “Gudmundstottir,” and her dialogue with Paul about Todd Browning’s Freaks.

The Player has many ingredients characteristic of crime films: a dead body, an investigation, a shady suspect, and a campaign of stalking and extortion. Yet, by the time Altman’s film reaches its ironic and deeply reflexive conclusion, viewers might well conclude that they are the ones who just got played.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their Criterion colleagues. A list of our Observations on Film Art series is here.

For more on Robert Altman’s career, see Patrick McGilligan’s excellent biography, Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. There are also several books featuring interviews with the iconoclastic director. These include David Sterritt’s Robert Altman: Interviews, Mitchell Zuckoff’s Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, and David Thompson’s Altman on Altman.

Those interested in learning more about crime fiction should consult Martin Rubin’s Thrillers, Charles Derry’s The Suspense Thriller: Films in the Shadow of Alfred Hitchcock, John Scaggs’s Crime Fiction, Richard Bradford’s Crime Fiction: A Very Short Introduction, and Martin Priestman’s The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction.

Hollywood Story (1951).

One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories

The Underneath (1995).

DB here:

The announcement of Ocean’s Eight (premiering, when else?, on 8 June next year) reminded me of the staying power of the heist genre, also known as the big-caper film. I discuss it a bit in Reinventing Hollywood, my book on 1940s storytelling, but it developed and spread out most vigorously from the 1950s on.

In its origins it relies on masculine roles; if women are present they’re likely to be at best helpers, at worst traitors. The big job is likely to be endangered by a man telling his wife or mistress too much, and then the police or rival gangs may interfere. So the news that Ocean’s Eight will center on a female gang constitutes an intriguing wrinkle. (Will a boyfriend try to spoil the caper?) Warners’ ambitions for another trilogy seem evident: presumably the entry is Eight because Warners hopes for a Nine and a Ten. Commenters are already worried that a “feminized” version runs the risk of flopping the way Ghostbusters did last year, but I’m more hopeful. The reason is that clever storytelling is encouraged in this genre. There’s a chance that the film, produced though not directed by Steven Soderbergh, will show us that this old dog has new tricks.

Because I’m interested in the storytelling strategies of popular cinema, the heist film is a natural thing for me to consider. Refreshing the genre may involve not just adjusting the story world—giving men’s roles to women—but also considering ways of handling two other dimensions of narrative: plot structure and cinematic narration. I argue in Reinventing that Hollywood filmmaking uses a sort of variorum principle, a pressure to explore as many narrative devices as possible within the constraints of tradition. For this reason, the prospect of Ocean’s Eight prodded me to think about how convention and innovation work in the caper movie. It’s also a good excuse to go back and watch some skilful cinema.

From the fringes to the core

The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

It’s useful to think of a genre as a category having a core and a periphery. At the core are prime, “pure” instances: prototypes. Stretching out from it are less central, fuzzier cases. Prototypical musicals are Footlight Parade, Shall We Dance?, Meet Me in St. Louis, and My Fair Lady. Somewhat less central are concert films and musical biopics like Lady Sings the Blues and Coal Miner’s Daughter. At the periphery are movies with a single song or dance number. Of course the category changes across history; a critic in 1960 might have picked North by Northwest as a prototypical spy thriller, but ten years later a Bond film would have probably held that place.

The prototypical heist film, critics seem to agree, doesn’t just include a robbery. There are robberies in films about Robin Hood and gentleman thieves like Raffles and the Saint. The outlaw or bandit film like They Live by Night and Bonnie and Clyde contains a string of robberies, but they wouldn’t be at the center of the heist category.

Donald Westlake proposed a concise characterization: “We follow the crooks before, during, and after a crime, usually a robbery.” This indicates two things. First, the plot is structured around the big caper, though there might be lesser crimes enabling it, such as stealing weapons. Second, the viewpoint is organized around the criminals, not the detectives who might pursue them, as in a police procedural. By these criteria, High Sierra (1941), although allied to the bandit tradition, fits because most of the film concerns a single robbery, its preparations and aftermath.

Westlake shrewdly goes on to note that the interest of a heist plot inverts that of the traditional locked-room detective story. Instead of wondering how something difficult was done, we wonder how something difficult will be done. “The puzzle exists before the crime is committed.” To fill in the how, crooks with specific skills (safecracking, demolition, getaway driving, and so on) are recruited. Because the process matters so much, Westlake adds that heist plots focus on details of time and physical circumstance, and they draw attention to impediments such as “dogs, locks, alarms, watchmen, and complicated traps.” Most of these features are missing from High Sierra; we’re not encouraged to speculate how the job will be pulled, there’s little meticulous planning and no division of labor by expertise, and the only dog is friendly. So it’s unlikely to be a core instance of the genre as we now consider it.

Most critics consider The Asphalt Jungle (novel, 1949; film, 1950) a solid prototype. In fiction and film it’s not the very earliest instance, but it displays what we might call the “completed arc” of a heist plot. A gang of varying talents is assembled and funded to pull off a jewel robbery, which succeeds partly at first and eventually fails.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

A less famous example comes from 1934, Don Tracy’s novel Criss-Cross. Here an alienated loner finds that his long-ago girlfriend has married a local crook. To get her back, the hero agrees to be the inside man in a robbery of the armored truck he drives. The heist goes badly, with the hero shooting the gangster and getting shot himself. He’s acclaimed as a hero, but fate catches up with him when a blackmailer who knows the truth starts putting the squeeze on him. Where The Asphalt Jungle ranges across many characters’ knowledge in a fairly tight time span, Criss Cross restricts its point of view to the protagonist but traces his life over a long period. These storytelling options, ingredient to any narrative whatsoever, will shape how the heist plot is handled.

Criss-Cross and The Asphalt Jungle show that we’re dealing with an exceptionally schematic plot pattern. For convenience we can distinguish five parts.

Circumstances lead one or more characters to decide to execute a heist (robbery, hijacking, kidnapping).

The initiators recruit participants.

As a group they are briefed and prepare their plan. They study their target, rehearse their scheme, or take steps to make it easier.

The heist itself begins and concludes.

The aftermath of the heist, failed or successful, shows the fates of the participants.

There are other conventions, nicely laid out by Stuart Kaminsky in 1974 and more recently by Daryl Lee. But I’ll just concentrate on this structure and how it governs narration, because these aspects show very clearly the constant dynamic of schema and revision in the filmmaking tradition.

Four capers, mostly unhappy

Criss Cross (1948).

Four films in the period covered in my book point toward the heist genre, though only one became a core instance. The presence of a “consolidating” film might be one way genres emerge.

The earliest candidate is an unlikely one. In 1941 Laura and S. J. Perelman mounted a notably unsuccessful play called The Night Before Christmas, a farce in which crooks buy a luggage store in order to tunnel from its basement into the bank vault next door. Although Paramount was a backer of the stage show, Warners bought the rights and revamped it for Edward G. Robinson, who had had success in gangster comedies like A Slight Case of Murder (1938). The adaptation, Larceny, Inc. (1942) maintained the premise but revised the plot, multiplying the complications that face the leader Pressure and his two minions. The twist is that thanks to Pressure’s daughter, who’s unaware of the scheme, business starts booming and the crooks find themselves prosperous businessmen. Woody Allen swiped the premise for his Small-Time Crooks (2000).

Just as we don’t expect a comedy to be the initial entry in a genre mostly associated with drama, we might expect that the early entries in the genre would be the tidiest, with complex variations building on them. Actually, two precursors of The Asphalt Jungle display remarkable complexity.

The simpler one, Criss Cross (1948), starts late in the preparation phase: the night before the caper, when the gang is holding a party to distract a local cop who has his eye on them. We learn that Steve is working with Slim’s wife Anna to double-cross the gang. The next day, Steve is driving the armored car and recalling how he got into this situation. A flashback provides the circumstances for the robbery—Steve’s pursuit of Anna, her marrying Slim, and Steve’s impulsive proposal of a robbery to protect Anna from Slim’s punishment.

Next comes the planning phase. The robbers assemble and the task is reviewed by a mastermind they hire. This second flashback ends and, back in the present, we see the heist itself. The aftermath of the bloody robbery shows Steve in the hospital, honored by the community. A thug kidnaps him and takes him to Anna. Slim has survived the gun battle and finds the couple; he kills them before he is mowed down by the police.

Early as Criss Cross is in the history of the film genre, the plot components are already being scrambled. Thanks to 1940s Hollywood’s commitment to flashbacks and character subjectivity, the novel’s linear action gets fractured, compressed, and stretched. Moreover, in most films, the decision to pull the heist is made fairly early. Here and in the novel, circumstances slowly force Steve to rescue Anna from the man who mistreats her. The buildup to this decision consumes nearly fifty minutes of an 87-minute movie. Similarly, the aftermath of the heist is quite protracted, running about twenty minutes. And whereas other films (and novels) dwell on the recruitment of thieving talent, here this is elided. That’s because the other members of the gang are less significant than the central triangle of Steve, Anna, and Slim.

The Killers (1946) is even more complex because it clamps the block construction of Citizen Kane onto the heist schema. We start with one bit of the heist aftermath: the death of the gas-station attendant Ole. Like Kane, who also dies in his bed at the start of his film, Ole is the protagonist of the past-tense story. We next meet the protagonist of the present-time story, the insurance investigator Riordan, who functions like the reporter Thompson in Kane, and sometimes even gets the same silhouette treatment.

The rest of the film splits up the basic parts of the heist schema, rearranges their order, and presents them through a series of several flashback blocks, anchored in six characters’ testimony.

The heist itself is very brief, running only about two minutes, and the planning phase is only a little longer. As in Criss Cross, the leadup and the aftermath constitute the bulk of the film, but these phases are broken up into many bits, and these are often shuffled out of chronological order. We see Ole’s discovery by Big Jim years after the heist and then we see Ole, days after the heist, distressed that his lover Kitty has betrayed him. Similarly, a crucial event after the heist—Ole’s stealing the loot from the gang—precedes a scene before the heist in which he learns the gang is planning to double-cross him. We have to reconstruct the canonical sequence, from circumstance to aftermath, out of fragments revealed in testimony taken by Riordan.

Critics haven’t taken Criss Cross and The Killers as the first core instances of the heist film, perhaps because these movies complicate the classic plot template. In addition, they downplay the planning and execution phases. The heist scenes are relatively minor compared to the time devoted to other phases, particularly the circumstantial buildup. Moreover, the robber teams aren’t vividly characterized and don’t display a range of expertise. The emphasis falls on Steve and Ole, both played by Burt Lancaster, as the beautiful losers who become suckers for treacherous women and their brutal men.

By contrast, the linearity of The Asphalt Jungle throws the plot template into crisp relief. Both novel and film offer a full-blown enactment of central features picked out by Stuart Kaminsky. The gang, despite low social standing, has many skills. They’re held together by a leader who may also be a brainy planner. The robbers’ plan requires “skill, practice, training, and above all, perfect timing.” The gang’s resourcefulness is tested by accidents. The caper is partly successful but largely a failure, often through sexual weakness on the part of some players.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

W.R. Burnett’s book opens up the wide narrative possibilities of the genre, thanks to an expanded group of characters. Where Don Tracy’s novel Criss Cross confined itself to relatively few figures, Burnett innovates by developing no fewer than eighteen distinct individuals, all somehow connected to the jewel robbery. New roles are assigned that will be staples of the genre—financier, go-between, bent cop, owner of a safe house. We see policemen of all ranks, a news reporter, the master mind Dr. Riedenschneider, the fixer Cobby, the bankroller Emmerich (who has a wife, a mistress, and a hired detective), and the four men on the team, two of whom have women attached.

The novel lays out the canonical action phases with surgical efficiency. But as in the films I’ve just mentioned, the planning and the heist itself take relatively little space. Given so many characters’ contribution to the action, their gradual convergence and their dispersed fates dominate the book. Over a hundred pages are devoted to setting up the circumstances and recruiting the gang. The aftermath, tracing the outcome for all involved, runs another 140 pages.

The film adaptation retains the novel’s scope, trimming only a couple of minor characters. It moves briskly among the ensemble, attaching us to several in turn, so we know more than any one character does. The narration creates parallels among the team members and their affiliates (such as four women of different classes, with varying commitments to their men).

The result is something of a network narrative, a cross-section of several people whose lives change because of the robbery. There’s no clear-cut protagonist like Steve in Criss Cross. Dr. Riedenschneider has the most screen time, but the film begins and ends with the hooligan Dix, and the fate of both men dominates the climax. I point out in Reinventing Hollywood that a multiple-protagonist film often gives extra weight to one or two characters.

50s and 60s stylings

Violent Saturday (1955).

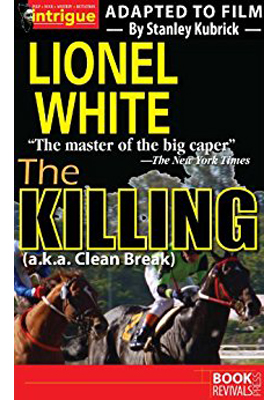

With The Asphalt Jungle as a robust prototype, writers and filmmakers developed the heist plot throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Despite his clumsy style (”He nodded with his head”), Lionel White became known as “the king of the caper novel” for his tireless variants on robberies, hijackings, and kidnappings. The other major figure was the far superior Donald Westlake, who wrote brutal heist tales as “Richard Stark” and comic ones under his own name.

In the comic register, Westlake was beaten to the post by heist films from England. The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) showed a timid clerk engineering the theft of gold bullion, which he disguises as kitschy miniature Eiffel Towers. The Lady Killers (1955) centered on a gang fooling their landlady into thinking that their planning meetings are actually string-quartet sessions. In Italy, the classic Big Deal on Madonna Street (I soliti ignoti, 1958) showed five incompetents trying to break into a pawnshop safe.

Big Deal was considered a parody of a much more serious film, one that was by then a landmark: Rififi (Du rififi chez les hommes, 1955). It did a great deal to consolidate the genre in France, along with Touchez pas au grisbi (1954) and Bob le flambeur (1956). (Both The Killers and Criss Cross had been imported in the Forties.) In England, the heist drama was seen in The Good Die Young (1954), while in the US there were 5 Against the House (1955), Violent Saturday (1955), Plunder Road (1957), The Big Caper (1957, from a White novel), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). The year 1960 saw a remarkable number of releases, with The League of Gentlemen (U.K.), The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, Seven Thieves, and most famously Ocean’s 11 (all U.S.).

Through the 1960s the genre proliferated, including a remake of The Asphalt Jungle (Cairo, 1963), Jules Dassin’s near-self-parody of Rififi (Topkapi, 1964), and a string of heist films that mixed in romantic comedy (e.g., Gambit, 1966; How to Steal a Million, 1966). The Italian Job (1964) became a cult movie, with tourists visiting the sites of shooting in Turin. The genre has remained robust throughout world cinema ever since.

The very rigidity of its format and the constraints it lays down, have allowed for ingenious innovations. I’ll sample some of those from the genre’s first dozen or so years, concentrating on three areas: the differing emphasis given to the plot phases; variants of point-of-view; and manipulations of time.

Where’s the action?

Rififi (1955).

The Asphalt Jungle offers a fairly pure geometry: the heist, lasting about eleven minutes, ends just before the film’s midpoint. On the other side of that is another big scene: a gunfight initiated by Emmerich’s henchman Brannom when Dr. Riedenschneider and Dix bring in the loot. That confrontation takes another seven minutes, so the heist and its immediate wrapup sit at the center of the running time. What led up to the heist, the circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases, consume the first forty-five minutes of the film, and the aftermath of the heist, affecting the surviving characters, will take just about as long. This balanced geometry, putting the heist snugly at the center of the plot but devoting most time to showing many lives leading up to and away from the crime, suits the extensive characterization of all involved.

This is a neat structure, but not the only possibility. Any phase of the action can be given great weight. The first half hour of Bob le flambeur is an episodic introduction to Bob’s routines and associates. It’s the circumstantial phase—he’s running out of money—presented at low pressure, emphasizing instead the fascinating milieu Bob coolly drifts through. Only when Roger points out a croupier at the Nantes casino does Bob formulate “the job of a lifetime.” Then crew assembly and planning can begin. As the plot develops, characters and relationships presented casually in the exposition become crucial to the heist and its unraveling.

Other phases can be stretched out. Ocean’s 11 dwells on the phase of gathering the talent. Before the start, Danny Ocean has already conceived the heist, but we aren’t told the plan. Instead we watch his team members converge on Las Vegas. Not until the film’s midpoint, at 53:00, is the plan revealed in a briefing. The dawdling exposition suits a film about cool guys hanging out.

The formation of the crew is exceptionally protracted in Odds Against Tomorrow, because here two members hesitate about participating. The racist Earl Slater, wracked by the shame of not providing for his wife, finally gets her to agree to let him join. Not until twenty-three minutes from the end does the African-American musician Johnny Ingram finally accept a role in the heist, which immediately becomes the film’s climax.

The source for Odds Against Tomorrow (one of the better heist novels) handles the basic pattern very differently, putting the heist just before the midpoint and devoting the second half of the book to the increasingly hopeless getaway, where the interracial tensions play out at length.

The planning phase sometimes includes a rehearsal for the heist, and that may require a subsidiary crime, such as stealing keys or a vehicle. The League of Gentlemen has an unusually long planning phase, in which the gang masquerades as soldiers in order to seize weapons from a military post. This robbery, running nearly twenty minutes, takes longer than the film’s main heist but serves to demonstrate the team’s resourcefulness and esprit de corps. The men’s precision and resourcefulness (based on their wartime experience) lead us to expect a successful main event.

Kaminsky suggests that the big-caper genre resembles the soldiers-on-a-mission movie, which centers on the details of a process executed by skillful specialists. That display of process comes to the fore in The Asphalt Jungle’s central robbery, which initiated the convention of detailing the mechanics of the heist. Other films expanded the heist sequence to larger proportions than was evident in The Killers or Criss Cross. Rififi became the model; its heist runs twenty-five minutes without any words being spoken. (That sequence is part of an even longer wordless stretch that runs over thirty minutes.) Dassin’s film meticulously breaks down the steps of a complicated robbery, allowing us to appreciate the men’s clever planning while, as usual, ratcheting up moments of suspense when it appears they might fail.

After Rififi, heist scenes got longer and more intricate. The one in Big Deal on Madonna Street runs twenty minutes, those in Seven Thieves and The Day They Robbed the Bank of England run thirty minutes, and those in Topkapi and The Italian Job approach forty minutes. To motivate these long, virtuosic passages, there need to be many obstacles, many ingenious ways around them, and many characters concentrating on their assigned duties.

Long or short, the heist can be shifted off-center. The heist can be the climax, as in The Big Caper, or it can be virtually the film’s entire second half, as in The Italian Job (which arguably doesn’t complete the heist and so never provides a proper aftermath). Topkapi’s flamboyant robbery, involving elaborate subterfuges, dominates the film’s latter stretches, leading to a quick reversal in its epilogue. The heist is finished early on in The Lady Killers, since the crucial action is the long aftermath in which, contradicting the title, the crooks dispose of one another. By contrast, the heist dominates nearly all of Larceny, Inc. Most of the film is devoted to the crooks’ slowly deepening tunnel, as the process is interrupted by breaks in the water main, a geyser of furnace oil, and their decision to abandon their plan in favor of going straight—before another crook comes along to continue the caper.

Or the heist can launch the film. In Plunder Road, after the train robbery is completed, the rest of the film is the aftermath, consisting of chases and suspense sequences. The circumstances, recruitment, and planning phases are alluded to in dialogue, as suits a low-budget production. The plot of Touchez pas au grisbi starts the morning after the caper and shows thieves trying to protect their loot from a treacherous drug dealer. It was probably inevitable that somebody would make a heist movie that keeps the heist offscreen and makes the action one long aftermath.

Steering the moving spotlight

Topkapi (1964).

Many films based on mystery rely on restricting a character’s range of knowledge, as in detective novels told in the first person. But suspense, Hitchcock and others recognized, relies on greater access to story information. If there’s a bomb under the table, Hitch advised, tell the viewer but don’t tell the characters. The heist film, as an account of how a crime is committed, depends more on suspense than mystery. So we’d expect a constant shuttling from character to character, filling us in on how the scheme is going and letting us worry about impending dangers.

This is generally what we find. Criss Cross is unusual in confining us to what Steve knows about Anna’s and Slim’s real agendas, and this confinement is what yields the surprises that pop up in the film’s final stretches. Mostly, though, heist movies and novels use omniscient narration. Employing what I call in Reinventing Hollywood the “moving spotlight” approach, the film shifts us from attachment to one character to another.

The moving spotlight permits us to understand the choreography of the crime, in which many characters play a part, and to feel suspense when matters of timing or accident intrude. Indeed, the convention of the unforeseen accident that spoils the heist relies on our breaking attachment to the crooks and getting privileged access to the off-schedule night watchman, the passing witness, or the failed piece of machinery. In Topkapi we and not the thieves learn how a stray bird will upset their getaway.

This omniscient narration (which need not tell us absolutely everything) can be deployed in a range of ways. One option is chapter titles, as in Big Deal on Madonna Street (and revived by Tarantino in Reservoir Dogs). A more common resource is the non-character narrator, present as an authoritative voice-over. In Bob le flambeur, a worldly male voice introduces us to Bob’s daily routine and comments somewhat cynically on his place in his milieu.

A similar all-knowing voice introduces us one by one to the heisters in The Good Die Young; there it eases the transition into expository flashbacks. Topkapi treats this convention, as others, with self-conscious playfulness. At the beginning the beguiling woman in the gang addresses the camera and explains that the heist aims to get the emerald she covets. She doesn’t take this narrating role again until the very end, in a brief epilogue that replays the gathering of the gang in stylized form.

Heist films must often choose whether to widen the field of view to include either the cops or civilians. Armored Car Robbery (1950), for me a peripheral instance of a heist film, alternates the gang’s activities—which do pass through the phases I’ve outlined—with the detectives’ investigation. The result is balanced between heist film and police procedural. Something similar happens in Violent Saturday (1955), which devotes most of its plot to a gang’s scheme to rob a mining town’s bank. Crosscut with the gang’s gathering and planning are scenes showing several members of the community, each with domestic problems. These scenes, typical of small-town melodrama (dissolute rich people, sexy nurse, repressed librarian, lovelorn bank manager), not only pad out the film but show us characters who will be affected by the heist. Some become witnesses and bystanders during the robbery, one is killed, and one, a local mining manager, will be forced to fight the gang at the climax.

The timing and selection of the shifts among characters can build up specific effects. For instance, in Big Deal on Madonna Street, the heist is conceived by Cosimo, a hardheaded crook doing time. A handful of would-be crooks decides to execute the robbery without him. We know, as the gang does not, that he has been released and is conspiring to interfere. The filmmakers could have made Cosimo’s return a surprise revelation, but instead our expectation that he’ll start meddling intensifies our interest.

Similarly, we know, as the Topkapi gang does not, that Arthur is a police spy. But then he confesses to them, so we know, as the Turkish police do not, that he is to be a double agent. The film milks suspense during the scenes in which Arthur relays information to the authorities, and then it makes us wonder how the gang will use their new knowledge of police surveillance. This is the sort of fine-tuned choice about “who knows what when” that heist films must make at every turn.

At a more granular level, when the spotlight is on one character, the filmmakers must choose whether to make those moments, shot by shot, highly restricted or not. In The Killers, Nick Adams’ account of Ole’s reaction to the stranger stopping for gas is more or less plausibly limited to Nick’s ken. But the precise exchange of glances between the driver and the Swede signal to us that Ole has been recognized. Nick doesn’t register this, since he’s standing at the rear of the car (barely visible in my first still, over Ole’s right shoulder).

In effect, this is a narrational aside to the audience. Nick can’t see this significant exchange of glances, and his voice-over doesn’t specify it, so we can’t assume Riordan learns of it. But this privileged moment primes us to see Big Jim as a major menace in scenes to come. This sort of deviation from what a character could plausibly know or notice is common in cinematic narration and differentiates it from literary narration, which is more tightly restricted in handling “point of view.” Classical Hollywood is biased toward unrestricted narration; radical restriction is rare. The heist genre can exploit many fine gradations between attachment to a character and more wide-ranging knowledge.

What’s our clock?

The Killing (1956).

As we’ve seen, two early instances of heist films break with a linear layout of the story. Criss Cross presents what Reinventing Hollywood calls a crisis structure, beginning just before the turning point and flashing back to show what led up to it. The Killers has a refracted narration, with all of the past events passed to the investigator Riordan and us through witnesses’ testimony. The flashbacks in Criss Cross are chronological, but those in The Killers are drastically out of order.

Time-scrambling, then, seems to be especially welcome in the heist film (as not, say, in the Western). The basic plot pattern is such a simple one that shuffling phases or parts of phases doesn’t create confusion. Yet few films of the 1950s I’ve found display the complexity of the Forties examples. Indeed, a time-juggling heist novel, The Lions at the Kill (Simon Kent, 1959) was ironed into straightforward linearity in the film version, Seven Thieves.

The Good Die Young displays a more complicated structure. It begins at a point of crisis, with four men driving in a car to the site of the caper.

The voice-over narrator introduces each man in turn, and then a long flashback explains his backstory. Deprived of information about the heist, we have to wonder how the narration will bring the men together and create their plan.

After the long section explaining each man’s circumstances, all involving women and money, the flashbacks meld. The men gradually come to know each other through frequenting the same pub. Their desperation pushes them toward accepting one man’s proposal that they rob a post office. With so much time spent on preparation and assembly, the actual planning is necessarily brief. Eventually the final flashback flows seamlessly into the present-time situation, initiating a brief replay of the dialogue in the car that opened the film. The heist (devolving into a disastrous gun battle) initiates the climax, and an airport aftermath concludes the film.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

The most ambitious 1950s recasting of the nonlinear efforts of the 1940s films is The Killing (1956). The source novel, Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955) consists of interwoven threads. A crook, his pal, a cashier, a bartender, and a crooked cop conspire to rob a racetrack. They will employ helpers to start a fistfight and shoot a racehorse. The early chapters devote short stretches to following each one, already recruited, through the circumstances phase of the heist template. The men assemble at their planning meeting, which is invaded by the snoopy wife of the weak cashier. She then tells her boyfriend about the heist, so another strand involving other characters is introduced.

On the day of the robbery, White’s narration again attaches itself seriatim to each man as he executes his role in the scheme. While the early part of the book had a few mild jumps back in time to follow each heister, the day of the job creates extreme back-and-forth shifts. We follow the bartender, for instance, going to the track on the fateful day, before the next subchapter skips back to the cashier waking up and then going to the same train. In a later section, we skip back to the previous day and attach ourselves to the sniper who will shoot the racehorse. Because of the overlapping lines of action, the shooting of the horse and the starting of the bar fight are presented twice. Everything eventually converges on Johnny Clay, the mastermind, who breaks into the money room and steals the day’s revenue.

These temporal overlaps emerge partly from the description of the action, but they’re also marked by either characters looking at clocks or watches, or by explicit mention in the prose, such as “It was exactly six forty-five when…”

The film version makes these overlapping schedules much more explicit. A detached voice-over describing police routine or criminal behavior had become a commonplace in the 1940s, in both “semidocumentary” films and in radio drama, notably Dragnet. In The Killing, apart from lending an aura of authenticity, the voice-over exaggerates the time markers of the novel by introducing scenes crisply. The first five scenes are introduced with these tags:

“At exactly 3:45…”

“About an hour earlier…”

“At seven PM that same day…”

“A half an hour earlier…”

“At 7:15 that same night…”

These lead-ins remind us of the ticking clock, set up parallels among the characters, and get us acclimated to the film’s method of tracking one character, then jumping back in time to track another. This is moving-spotlight narration on markedly parallel tracks. The same method will be applied during the heist, when ten consecutive scenes and several others will be tagged in the same way. (“Mike O’Reilly was ready at 11:15.”)

It’s not just the repetitions that exaggerate White’s jagged time scheme. When the sniper Nikki is shot after plugging the racehorse, the narrator reports drily: “Nikki was dead at 4:24.” Cut to Johnny leaving a luggage store, and the voice-over announces: “At 2:15 that afternoon Johnny Clay was still in the city.”

The time jumps more or less buried in White’s prose are made dissonant in the film. Here the juxtaposition heightens the likelihood that Johnny’s robbery won’t go according to plan.

The replays are no less sharply profiled. As the scenic blocks move from character to character and skip back in time, they include actions we’ve already seen. The most persistent is the repetition of the track announcer’s calling the start of the crucial seventh race, but we also get replays of the wrestler Maurice starting a fight, the downing of the horse, and glimpses of Johnny waiting to slip into the cash room.