Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Eep, omigosh, urk, smerp, and other Archie epithets

DB here:

Not all cinephiles are comics fans, but quite a few are. I guess it’s partly a matter of the Adolescent Window, and partly an intuition that both are forms of what Will Eisner calls “sequential art.”

For my part, a Boomer childhood spent with Nancy and Little Lulu and Scrooge McDuck was followed by a boyhood fastened on Superman and Batman. Then came the cutoff. I went to college as the Marvel Universe was populating, and I never got into Underground Comix. Only Krazy Kat stayed with me through my college years.

In the 80s Kristin and I followed young talents like Matt Groening, Berke Breathed, and Lynda Barry, while becoming fans of McCay. When I encountered Eurocomics, particularly the Clear Line style and its heirs, I perked up. Joost Swarte (and here) was a special favorite of ours. At about the same time I revisited the old stuff, like Cliff Sterritt. During the 90s and 00s, I tracked the emergence of Ware, Clowes, and other independents.

In the 80s Kristin and I followed young talents like Matt Groening, Berke Breathed, and Lynda Barry, while becoming fans of McCay. When I encountered Eurocomics, particularly the Clear Line style and its heirs, I perked up. Joost Swarte (and here) was a special favorite of ours. At about the same time I revisited the old stuff, like Cliff Sterritt. During the 90s and 00s, I tracked the emergence of Ware, Clowes, and other independents.

Somewhere in all this, Archie abides. I can’t remember when I started reading him, or when I stopped, but he was for me, as for many others, simply and permanently there. Only when I accidentally learned in 2009 that he was to marry Veronica did I go back to him. Finding an interesting variant of the three-roads motif of folklore, I whipped up a blog entry. I added some thoughts about the skillful graphic design of Bob Montana’s 40s work, but in the process I was too dismissive of the later decades chronicling life at Riverdale High.

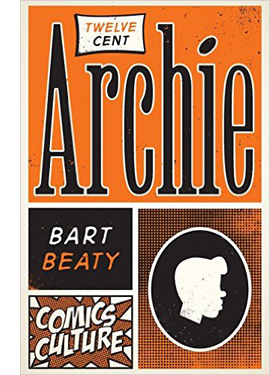

I realize my error now thanks to Bart Beaty’s wonderful Twelve Cent Archie. It’s a critical and historical study of Archie’s world from December 1961 to July 1969, a period when the comics sold for a princely $.12. That’s also the period, Beaty maintains, when the books’ most skilful writers and artists were at work: Stan Lucey (the Archie titles), Dan DeCarlo (Betty and Veronica), and Samm Schwartz (Jughead). Beaty read every book in the nineteen series, over 900 volumes in all. This admirable undertaking yields funny and enlightening results. It’s one of the best books of comics criticism I’ve ever read.

The Archie Machine

For many of us, Archie is surpassed only by Nancy in the Bland Storytelling Sweepstakes. Archie is a freckle-faced guy on the make, rich girl Veronica alternately two-times him and flies into jealous rages, and Betty pines for Arch from afar. Archie’s rival Reggie tries to gum everything up, while Jughead watches with a mix of scorn and indifference. The plots are filled with deception, misunderstandings, horrible coincidences, and slapstick. Needless to say, the adults—teacher Miss Grundy, principal Mr. Weatherbee, Coach Kleats, Archie’s parents, Veronica’s dad Mr. Lodge—don’t have a clue.

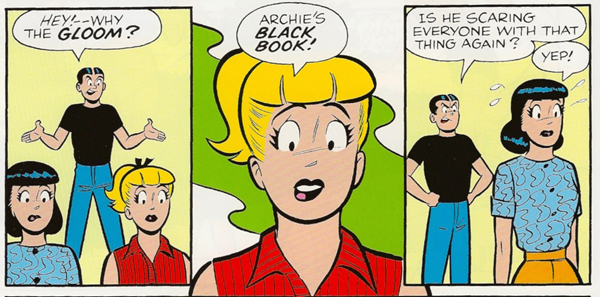

The saga is so cut-and-dried that the makers could publish a story called “How to Write Comics” (1965), in which the moves are laid out with daunting clarity.

These tips remain good advice for plot-making. Had Beaty done no more than unearth this tale, we’d owe him a lot. As ever in popular culture, though, things aren’t so simple. Beaty shows us why.

At one level he embraces the sheer repetitiveness of it all—what he calls the Archie Machine. Oddly, as he points out, Arch is, narratively speaking, null. He can be a good student or a poor one, a clever manipulator or a klutz. Only a few traits, such as his need for money and his innocent lust for vertiginous kisses, persist. Reacting to situations rather than creating them, neither hero nor antihero, he’s more of an unhero, “a blank space on which stories are written.” As a result, there’s little continuity in the stories. If the plot demands Archie to be good in French, he will be, even if previous stories have shown him to be linguistically inept. Besides, as Beaty asks, “Does Riverdale High even have a French teacher?”

The same goes for Riverdale, which despite its name, seems serenely indifferent to its river, which hardly ever appears. There are four seasons, but the topography is fluid, provided with mountains, beaches, forests, and farm fields as needed. This Borgesian landscape reminds you of the Simpsons’ Springfield, but that municipality has landmarks for ready reckoning. Homer always lives next door to Ned, Moe’s bar is always beside King Toot’s Music Store. Beaty points out that in Riverdale, we can’t say whether Veronica’s house is on Archie’s way to school: sometimes it is, sometimes not. “It depends on the needs of the story.” And unlike Springfield, Riverdale is forbiddingly WASP: “a wish-dream of white privilege and normative sexualities.”

Given this mixture of relentless monotony and casual vagueness, the challenge for the writers and artists was to make something interesting. Here’s where Beaty’s book pulls me in: Artists need to solve problems. He shows that his three main artisans created fun and cleverness out of nearly nothing.

I dimly remember thinking, as a kid, that there was more going on in those books than I could understand, but finally, sixty years later, I get a glimpse of it.

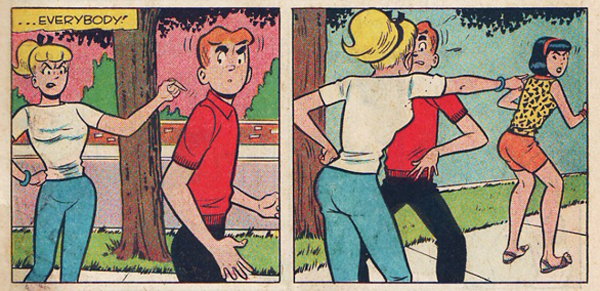

Take Betty. Betty isn’t just the lovelorn also-ran. She plots against “best friend” Veronica, pulls pranks to fool the hapless Arch, and generally acts, as Beaty notes, like a stalker. As for Veronica, she can be quite the schemer too. Pictorially, though, they might be twin sisters. “Betty = Veronica,” one of Beaty’s 100 (!) chapters, asks: “Why does Archie struggle to choose between Betty and Veronica when, for all intents and purposes, they are exactly the same person?” Okay, Betty has a ponytail (to which Beaty devotes another chapter), but you take his point. Even when the girls decide to change hairstyles, they wind up looking cloned.

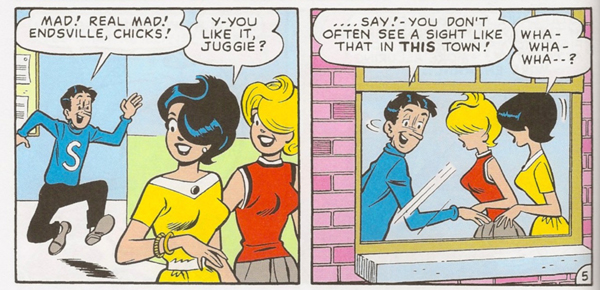

In scenes like this, you have to believe that the creators were having fun with the standard-issue look of our two heroines. Their cookie-cutter similarity allows for ingenious changes in posture, costume, and expression (see below), and can be a source of gags, as here–when their peekaboo hair styles keep them from seeing a pop star’s passing below them.

Silly dialogue that made me snicker still does. Reggie strolls along singing, “I love me, I think I’m grand. When I’m with me I hold my hand.” In the summer I graduated from high school, I don’t think I read the following exchange, but I would have mostly understood it.

Archie, at Betty’s door: “Howdy! I’m a mild mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper!”

Betty: “Come in, mild-mannered reporter! Do something super!”

Archie: “I’ll try!” (Kisses Betty off her feet)

Betty (staggered): “Whew! That’s what I call SUPER, man!”

Betty (recovered, ushering Archie to the door): “Let’s go! I’m not a good first violinist, but I can play second fiddle with the best!”

Archie (serious): “You wound me!”

You wound me?! Denying he’s grabbing Betty on the rebound is an act of supreme callousness. No Superman, Arch. Beaty credits some of the best lines to writer Frank Doyle, source of “I never snapped a whipper in my life.” I wonder if Doyle wrote the oft-reprinted Tiger (1961) with its memorable “A boiling, bubbling volcano flames behind this mild-mannered facade.”

Fun lovin’

Beaty offers so many ideas and observations that I can pause only on the major thing he convinced me of: the fine comic draftsmanship of Harry Lucey. Beaty waxes eloquent on Mr. Lodge’s anatomical twists and turns across a single page. That called my attention to the fact that Lucey drew funny, especially in scenes of manic action. It’s all in the legs and toes, kids.

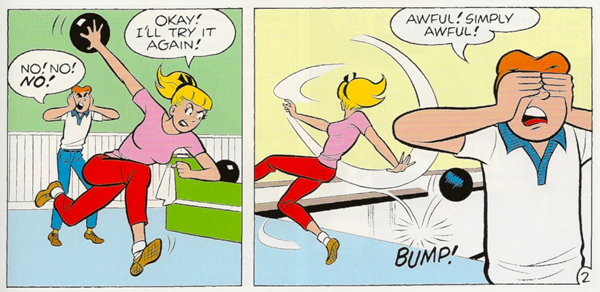

Who expects contrapposto in an Archie comic? But we get it when Betty goes bowling.

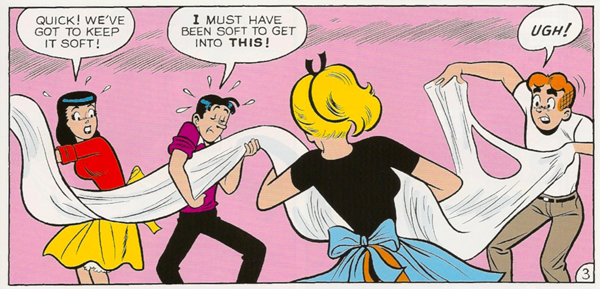

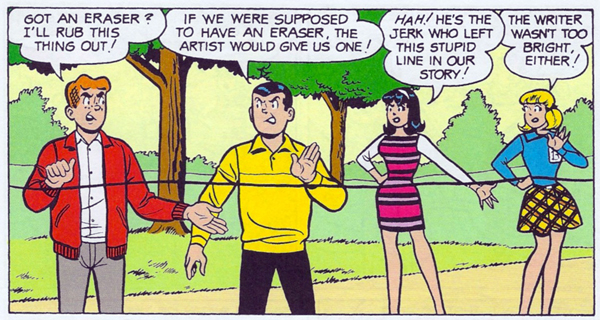

At times we get the classic comic multiple-image stuff that not only cartoonists but animators like Disney and Bob Clampett used in movies. Archie has been spotted carrying his mother’s purse.

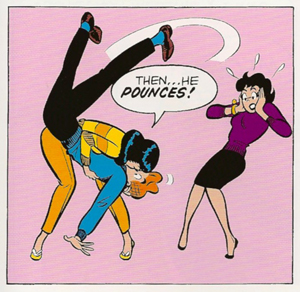

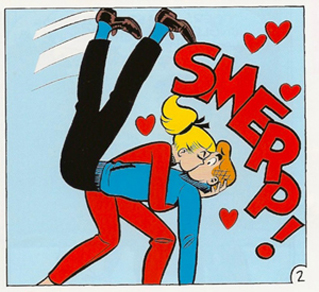

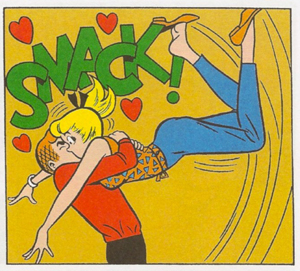

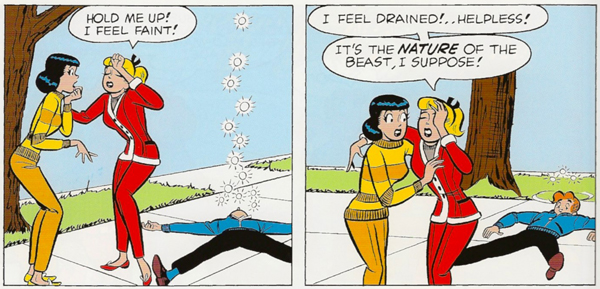

As Beaty shows, Lucey excelled at calisthenic clinches and tornado-intensity smooches. When a character, even a dog, kisses another character, he/she/it sweeps the kissee off his/her feet, literally.

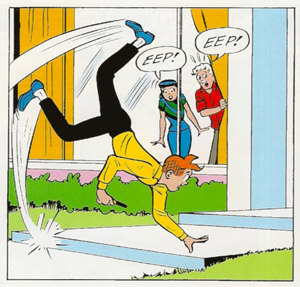

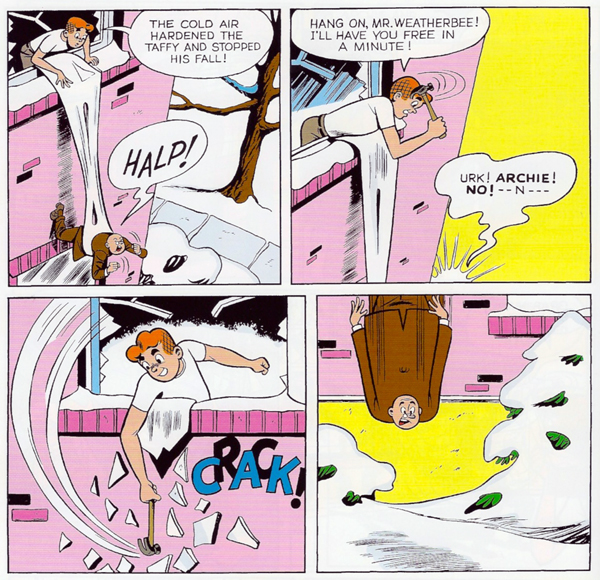

Perhaps because the action is often so violent, Lucey can spare a panel that’s a virtual freeze-frame. Any other artist would have wrapped Mr. Weatherbee, plummeting out of his taffy shroud, in a flurry of speed lines, as above. The near-absence of those lines makes the poor man seem suspended forever before his fall.

Actually there are speed lines, but they’re so slight and striated they might be creases in the brown suit. Only the sharpest eye will catch the ones around Mr. Weatherbee’s left wrist.

Thanks to Lucey’s technique, in the same panel the hapless Riverdale principal both falls and hangs suspended.

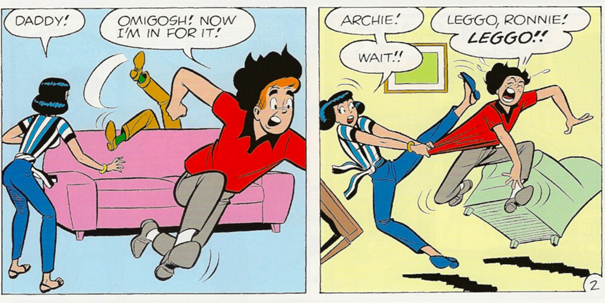

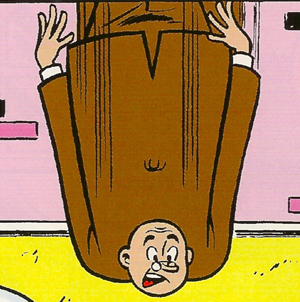

Hergé likeds to keep his scene’s space clear and consistent, modifying it slightly with “cut-ins” and “pans.” Lucey, like other American comics artists, freely changes angle and even character arrangement to create variety and to point up dialogue. In one pair of panels, the change of angle is bold, slicing off half of Archie’s face to give greater emphasis to Betty’s angry arm-thrust and Ronnie’s reaction on the far right.

A slight change of angle can accentuate background action–below, a flattened Archie raising his head. But Ronnie and Betty have already slid toward the foreground as well.

Characters are freely shifted around the frame, usually in obedience to a left-to-right reading of the balloons. But across a page these spatial reorientations can create a vivacious pattern. Against the mild purple chair, for example, Betty’s scandalous polka-dot dress pops out in each panel while dominating the layout as a whole.

Lucey could do detail too. In any given panel or set of panels, there are little touches that distinguish Betty from Veronica—typically, the lips. Here Betty’s mouth in the second panel seems to catch Veronica’s sideways twist in the first. By the third, Veronica’s mouth has straightened out a little.

Like Archie comics or despise them, but don’t talk about Cathy or Dilbert in the same breath. If you’re a cartoonist, you should be able to draw. If you can infuse your drawing with vivacity, so much the better.

I’ve followed Beaty’s work since his magisterial series, “Eurocomics for Beginners” ran in The Comics Journal in the 1990s. His many books are major contributions to comics scholarship. For sheer pleasure, though, nothing of his I’ve read surpasses Twelve-Cent Archie. It’s at once personal–he recalls his childhood encounter with a cache of Archie books on summer vacation–and analytical in a sympathetic way. Like a lot of good criticism, it opens your eyes while making you smile.

Bart Beaty provides background on Twelve Cent Archie in this interview. A worthwhile review is in The Atlantic Monthly. Beaty talks with indefatigable media analyst and blogger Henry Jenkins at Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell of 20th Century Books and Bruce Ayers of Capital City Comics for help in finding some Archie stories. Thanks as well to Jim Danky for many long lunches about comics, film, and less important things.

The Archie-marries-Veronica issue I wrote about in 2009 was but the beginning of a long parallel-universe cycle. For a list of the many other revisions in the Archie-verse, see this article. Then there are the Betty and Veronica reboots. The horror cycle, Afterlife with Archie, went in another direction. (And you thought the original kids were zombified.) It’s been a big success. Urk!

In timely fashion, Mad City Movie Guy Gerald Peary has come out with his own contribution, a documentary called Archie’s Betty. He too has reviewed Beaty’s book for The Arts Fuse.

P. S. 23 January 2017: Here’s some fascinating backstory on the “reimagining” or “rebooting” or “reinvention” of the Archie saga. Turns out Forking-Path Archie, which got my attention, was a turning point for the company as well as its protagonist.

Poets’ summer: PATERSON, A QUIET PASSION

A Quiet Passion (Terence Davies, 2016).

So I write—Poets—All—

Their Summer—lasts a Solid Year—

They can afford a Sun

The East—would deem extravagant—

Emily Dickinson, “I Reckon–when I count it all,” no. 569

DB here:

From the Vancouver International Film Festival, I write on two new films you should see as soon as you can.

How to make a film respecting the power of poetry? More basically: What is that power? Does it lie in the fact that poetry can be a part of ordinary life? This seems to me the angle taken in Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson. Or does poetry’s power arise as an alternative to mundane intercourse, a realm in which we test thoughts and feelings beyond the flow of daily life? I think this is the angle taken in Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion.

The secret notebook

Paterson drives a bus in Paterson. The bus’s destination display bears not a street name but rather the word “Paterson.” Such playful quirks, long a part of the American indie game, is as inoffensive as the film’s title (Paterson, of course). The milieu looks prosaic enough, with quasi-documentary shots of streets and the Great Falls. But Paterson owns a bungalow on a bus-driver’s salary, catches a 1930s horror film at a local theatre, and drops in at a saloon where a barkeep named Doc plays chess with himself. The town has more than its share of twins too.

In this slightly off-track version of a city, the protagonist’s Iranian-American wife Laura paints fabrics, bakes designer cupcakes, and wants to be a country singer. Meanwhile, Paterson has creative impulses of his own. He writes poetry.

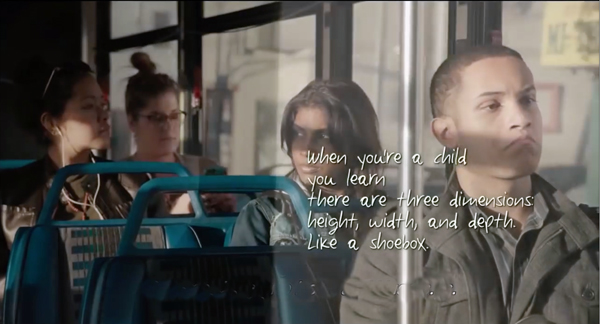

Paterson is a quiet, genial fellow to whom you’d happily entrust your morning commute. His poems (written by New York School poet Ron Padgett) are conversational; the first one we hear begins: “We have plenty of matches in our house.” The poems are given their force by their homely details and the repetition of simple declarative phrases.

Repetition is built into the film’s block construction: A Week in the Life. Waking up, having breakfast, walking to the bus terminal, jotting down some verse before beginning his routes, lunch and more jotting, walking home, eating dinner, and visiting the bar—Paterson ‘s routines create a rhythmic matrix that we quickly learn. That the film’s structure is built around work routines makes sense. In America, a poet might be your bus driver, your doctor (William Carlos Williams), your insurance executive (Wallace Stevens), the farmer down the road (Robert Frost), or your teacher in business school (Marianne Moore).

As for poetic texture, the routines get treated in small-scale variations. Take the opening bed shot, an overhead view of the couple that announces a new day. One morning Laura isn’t there. Sometimes we don’t get a shot of Paterson checking his wristwatch. The weekend mornings lack the daily written title that the workdays get. A poetic principle of verse and refrain gets built into the film’s structure.

Finer-grain texture comes in the recitation of the verses as Paterson writes them into his scruffy notebook. We see the lines form on the surface of the screen, in freehand script, while montages of driving surge underneath them–as if these were coming to life in the course of the day. The fate of the secret notebook is probably the biggest dramatic twist in the film, but even that becomes part of a larger pattern after a melancholy Sunday walk.

And drama? There are moments of tension. Paterson is unenthusiastic about Laura’s buying a guitar, and an habitué of the bar seems to create a life-or-death crisis. Yet these and other problems slide away quickly. When Saturday night comes around, a kind of climax occurs. It tails off, subsumed in the playing out of motifs that were installed early on—rhymes, we might say.

As you’d expect in a film living under the aegis of Williams (author, of course, of Paterson the book of verse), it’s all about the discrimination of detail. “No ideas but in things” is the motto. The emblem becomes the Ohio Blue Tip Matches described in Padgett’s poem and shown to us in close-up. Laura reveals her poetic acumen when she asks if Paterson’s verse mentions the megaphone skew of the label’s lettering.

Paterson may write alongside a waterfall like a classic poet inspired by nature’s sublimity. But in tuning his ear to his passengers’ conversations and by finding epiphanies in mass-manufactured objects, he’s in the American grain.

Night thoughts

Paterson is so unassuming in his creativity that his film might have been called A Quiet Passion. That, though, is the title of Terence Davies’ tribute to Emily Dickinson. But not much about her is presented as quiet. The film starts with the tart young Emily declining to accept a place in Mt. Holyoke’s pious “ark of safety.” She prefers the soaring rapture of Bellini’s “Come per me sereno,” a bride’s thank-you to guests at her wedding. While her family listens politely in their concert-theatre box, she sways in sympathy with the singer. The scene seals her pledge to art.

Any biopic of the Belle of Amherst faces the problem of characterizing her through talk and action. One option is to make her meek and introspective. Another is to make her conversation as diffuse, oblique, and staccato as her verse. Davies has boldly tried another tack. He has made her one of a trio of eloquent women who swap epigrams as swiftly as if they were in an opera or an Oscar Wilde play. Davies seems to be suggesting that worldly (and wordy) banter with her kindly sister Lavinia and racier friend Miss Buffam gave Emily a sense of the blunt force of language.

Paterson is laconic and ruminative, like his verses, but Emily is a parlor dialectician. She hammers fierce comebacks at her father, at her brother (especially when he takes a mistress), and even at the devoted Vinnie. What authority she gains in her closed society emerges mostly from her wit and tongue. (Though she can calmly smash a plate too.) At the same time, Emily knows her words can wound. She’s miserable after snapping at the family servants, and after a volatile exchange with Vinnie she despairs of ever being a good person.

Here is a woman who feels the power and pain of language. Once we understand that, we’re better prepared to understand the inward turn of her verse. Unlike her dueling conversations, her poems are skewed and slanted, with unexpected jumps at every line, or dash. They twist nursery-rhyme cadences and simple vocabulary into Donne-like knots of phrasing. The film’s voice-over recitations make the verse even more elusive than on the page, but I don’t know how else Davies could have handled them. Even showing the lines as they emerge, as Paterson does with superimposed writing, wouldn’t fully satisfy. We need time to ponder the impacted syntax on display. I suspect that instead of trying to translate the perplexing force of Dickinson’s verse, Davies’ film exists as a parallel text, a supplement urging viewers to return to the poems after witnessing Emily’s socializing and suffering.

Familiar Davies themes emerge. Fiery spirituality clashes with hypocritical churchifying; family ties are fulfilling but also suffocating; a single room can enclose peace or stabbing pain. There’s the power of women’s friendships, alliances against a world bent on cutting them down. Davies reminds us that “women’s art” often involves handicraft. Emily is not only writer but book-maker, trimming and stitching little pages together into secular devotionals. These mini-books recall and mock those pious guides for meditation that could be tucked into purses and waistcoats.

Paterson writes in the daytime, while waiting to pull the bus out of the garage or on his lunch hour or even while driving. Emily, once her father gives his permission, writes from 3 AM into the morning. Accordingly, the bus driver’s poems, like those of Williams, have the evenly-lit clarity, if not the compression, of a haiku, while Emily’s verses, haltingly phrased, move in a hallucinatory blur. Jarmusch’s no-fuss staging and editing suit the unassertive texture of the verse and the driver’s days, while Davies, himself something of a chamber artist and a master of the musicalized image, scans his parlor tableaux with lush gravity.

Two films, each one both light and grave, adroit and solemn, though in different registers. Whatever cinematic poetry is, they aspire to it.

Michael Koresky has a superb discussion of Paterson at Reverse Shot, the Museum of the Moving Image site.

Note for the theoretically inclined: Paterson‘s structured routines and substitution-slots interestingly conform to Roman Jakobson’s dictum that the poetic function consists of the projection of the paradigmatic axis of language (alternative lexical items) onto the syntagmatic axis (the linear flow) of a text. See his “Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics.”

Another entry on this site considers Davies’ Sunset Song and his other films. As Moonrise Kingdom is one of our blog’s favorite recent films, it’s a pleasure to glimpse Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward as kids bringing anarchy to Paterson, N. J.

Paterson (Jim Jarmusch, 2016).

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.

The Walk combines narrative and genre in an unusual way. The first part is a romantic comedy, the second a suspense film, and the third a lyrical piece. We suggest why in Talking THE WALK.

The way a film tells its story can vary considerably depending on whether it has a single protagonist, a dual protagonist, or a multiple protagonist (as in The Big Short, bottom). We examine some of the differences in Pick your protagonist(s).

Looking back over our blog as we passed 700 entries early this year, it occurred to us that several entries discussing principles of storytelling could be arranged to create a pretty good class in classical narrative strategy. We made up an imaginary syllabus in Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101. No tuition charged.

With the very end of the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise–the release of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third Hobbit film–we discuss the strengths of the film and the plot gaps left unfilled in A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

To celebrate Orson Welles’s 101st birthday, we examined some of the sources for some of the techniques used in Citizen Kane, a film we analyze in detail in Chapters 3 and 8. See Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts.

In Hollywood it is a common assumption that the protagonist(s) of a film must have a “character arc.” Filmmaker Rory Kelly, who teaches in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, wrote a guest entry for our site. Rory analyzes the character arc in The Apartment, with examples from Casablanca, Jaws, and About a Boy as supplements. See Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly.

James Schamus’ Indignation, an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, draws on novelistic narrative devices not in the original. In INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film, we suggest that those devices first became standard in cinema during the 1940s.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

Teachers and students always want to us add more about acting to our book. It’s a hard subject to pin down. We introduce the great stage actor Mark Rylance, who was largely unknown outside the United Kingdom before he won an Oscar for Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, and discuss how he achieves his expressively reserved performances in that film and the series Wolf Hall. See Mark Rylance, man of mystery. (Above at left, on set with Tom Hanks and Spielberg.)

In an era when most staging of actors in movies follows a few simple conventions, we examine the more imaginative ways of playing a scene on display in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950) in Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers young and old.

Continuing with the theme of acting and staging, our friends and colleagues, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have put a revised version of their in-depth study of silent-cinema acting online for free. Learn about it and the enhancements that internet publishing has allowed in Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

We look at the visual style of Anthony Mann’s Side Street (1949) and show how a simple, seemingly minor technique like a reframing can create a strong reaction in the spectator. See Sometimes a reframing …

Framing a composition is one of the most basic aspects of cinematography. We discuss centered framing, decentered framing, balanced framing, framing in widescreen movies, and particularly framing in Mad Max: Fury Road (above) in Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom.

In a follow-up entry, we discuss framing in the classic Academy ratio, 4:3, with emphasis on action at the edges of the frame: Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

For the new edition of Film Art, we had to eliminate our main example of sound technique, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige. But we put that section of the earlier editions online. THE PRESTIGE, one way or another takes you to it.

For those who have been looking for examples of internal diegetic sound, we take a close look (listen) at a sneaky one in Nightmare Alley: Do we hear what he hears?

The fact that the protagonist narrates The Walk in an impossible situation, standing on the torch of the Statue of Liberty and talking to the camera, bothered a lot of critics. We suggest some justifications for this decision in Talking THE WALK.

We offer brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated music from 2015 films in Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Many different filmic techniques can serve similar functions. Filmmakers of the 1940s had a broad range to choose from when they portrayed dead people, or Afterlifers, on the screen. We look at how their choices affected the impact of the scenes (as in Curse of the Cat People, above) in They see dead people.

Style and form in three films of Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and especially his most recent work, Sunset Song. See Terence Davies: Sunset Songs.

Style and form in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, on the occasion of its magnificent release by The Criterion Collection, in A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

Leo Hurwitz’s little-known documentary, Strange Victory (1948) has recently come out on Milestone’s DVD/Blu-ray. Released shortly after the end of World War II, it suggests that the Nazi atrocities were only an extreme instance of the cruelty of racism. We discuss the film and its relevance to the current political situation in Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948).

Experimental filmmaker Paolo Gioli makes films without cameras, or at least, he cobbles together pinhole cameras of his own from simple materials. The results are remarkable. We describe his work and link to a recent release of his work on DVD in Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

The eleventh edition of Film Art contains a new sample analysis of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. We discuss some additional aspects of the film in Wesworld.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

At the end of each year we avoid doing a standard ten-best list by choosing the ten best films of ninety years ago. For 2015, we dealt with The ten best films of … 1925 (including Frank Borzage’s Lazybones, above). It was a very good year.

A rare French Impressionist film, Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine, has been released on DVD/Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. We discuss the film and its background in L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema.

Film Adaptations

Our eleventh edition offers an optional chapter on film adaptations from a wide variety of art forms and even objects.

For thoughts on popular female novelists whose books were adapted into films during the 1940s and 1940s (and who sometimes became screenwriters), see Deadlier than the male (novelist).

Adaptations can be made from nonfiction as well fictional books. We look at how Dalton Trumbo’s life was made into a biopic in Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO.

In a series of entries, we have commented on the adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit into a three-part film. For an analysis of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third part, see A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump? (Links in that entry lead to earlier posts on this subject.)

As always, we have blogged about some recent books and DVDs/Blu-rays. See here (Vertov, sound technology, 3D), here, (Kelley Conway’s new book on Agnès Varda), here (experimental films, the first Sherlock Holmes, the Little Tramp), here (Tony Rayns on In the Mood for Love), and here (on some older foreign classics that have finally made it to home video in the USA, primarily those of Hou Hsioa-hsien). The publication of the eleventh edition of Film Art led us to look back on how it was written and some of the ideas that went into it. We took the occasion to introduce our new co-author, Jeff Smith. See FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

We were also profiled in Madison’s local free paper, Isthmus, by Laura Jones, reporter and filmmaker. She read Film Art as a student.

The Big Short (2015).

INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film

Indignation (2016).

DB here:

As I finish my book on 1940s Hollywood storytelling, I see that period’s influence all over the place. (Actually, that’s part of the book’s point.) One thing that filmmakers did back then, I think, is make cinema more “novelistic.” It’s not just that they took stories from novels, though they certainly did. They also made much greater use of storytelling devices that had become common in literature both high and low.

Many of these techniques I’ve talked about in other entries. There were, of course, flashbacks—not new to the Forties, but now much more frequent than in the Thirties. There was also the rise of voice-over commentary, like the narrating voice of fiction. It might be the voice of an objective narrator, as in Naked City (1947). Or it might be the voice of a character, either telling the tale to another character, or recalling events purely in his or her mind.

Other types of subjectivity came forward too, such as dreams, daydreams, and hallucinations. Filmmakers of the 1930s were inclined to tell their stories objectively, through concrete behavior. But thanks to imported and revised literary strategies, many Forties films gain a greater density and interiority. Compare, for example, the 1931 Waterloo Bridge with the 1940 one.

One thesis of my book is that filmmakers of the Forties consolidated these strategies in a way that became central to modern movie storytelling. That seemed to me to be confirmed when I saw James Schamus’s directorial debut, Indignation, now or soon playing at a theatre near you. Because of his skill as a screenwriter, I expected an intelligent adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, but I also hoped to learn more about the expressive resources of contemporary cinema. I wasn’t disappointed.

Indignation’s core story involves Marcus Messner, studious son of a New Jersey butcher who goes off to a Midwestern college. Stuffed with ideas and ambitions, Marcus is intellectually worldly but socially and sexually naïve. If he weren’t in college, he’d be drafted to fight in the Korean War. Instead of fitting smoothly into academic life, he finds himself confused by Olivia Hutton’s calculated sexuality. In addition he struggles with an overprotective father and the puritanical, hamfistedly Christian, regimen of 1951 campus life.

To talk about what I find exciting and instructive in the film, I have to presume you’ve seen it. So what follows is filled with spoilers.

Sticking to one causal line

Like the book, the film is an exercise in restricted point of view. That involves not simply the voice-over commentary that weaves in and out. (In a film, that technique doesn’t guarantee restriction the way first-person narration would in a novel. Movies can be more promiscuous in breaking with what one character thinks and knows.) And the restriction isn’t wholly a matter of a subjective plunge either, though we do get Marcus’s dreams and fantasies and some fragmentary flashbacks.

No, what makes Indignation intriguingly “novelistic” is a matter of attachment. We’re simply with Marcus through almost the entirety of the movie. We know only as much as he knows. This means that we learn about certain things when he does. His father’s breakdown back home is conveyed through phone calls. At the climax, his mother’s visit to him in the hospital reveals that she’s considering divorce. An alternative narrative strategy would be to shift from scenes with Marcus to scenes elsewhere, say back home in New Jersey or in Olivia’s dorm. This “omniscient” option is more common throughout American film history; we see it in the crosscutting between CIA malefactors and poor David Webb in Jason Bourne.

Restricted narration isn’t the only way to generate mystery, but it’s a reliable one. By attaching us to Marcus’ range of knowledge, Indignation creates mysteries, chiefly around Olivia. What has made her behave as she does? She never offers a full explanation, but in some scenes she tells more about her parents and in a crucial confession she confesses her alcoholism, a suicide attempt, and a period in treatment.

During this confession, Schamus finesses the showing/ telling problem in an intriguing way. There are good reasons, I’ve suggested before, to let such monologues play out in the space and time of the scene. Telling is sometimes more vivid than showing. But Schamus has chosen to show as well as tell, by providing quick flashback illustrations of what Olivia recounts to Marcus.

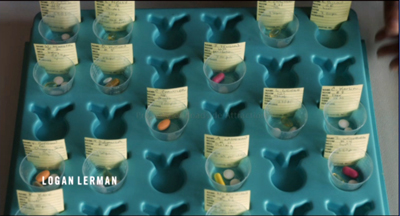

What interests me is that these images from the past have an in-between status. They’re neither straightforward and neutral, nor Olivia’s own viewpoint, nor exactly Marcus’s imagined version of what she’s telling him. For instance, the straight-down, somewhat diagrammatic and clinical framing of some of them calls to mind the film’s first shot, also associated with Olivia’s health: the pill case in the care facility.

Likewise, the shot of Olivia in a straitjacket, framed off-center in a way few other isolated long shots in the film are, has an abstract quality that suggests an image lying somewhere between her memory and Marcus’s imagining of her situation—without making it wholly subjective. (In the early 1950s, it’s plausible she was indeed treated this way.)

At the climax, we get even less information about Olivia’s situation. Before Marcus can break off with her, she simply vanishes. Marcus will never find out what became of her. For him, if not for us, the mystery is permanent.

Not that he doesn’t try to communicate. This is one role of the voice-over in which he muses on his past and, more ambitiously, on the role of cause and effect in life. As a follower of Bertrand Russell, he’s evidently pondering Russell’s idea of “causal lines.” Ironically, though, Russell’s inferential model of causality doesn’t help Marcus figure out what happened to Olivia.

But from where is Marcus speaking? Quite likely, from the Afterlife.

Dead narrators drift through 1940s cinema. Philip Roth was ten when The Human Comedy (1943) featured a deceased father returning to his small-town family, and eleven when The Seventh Cross (1944) gave us an executed prison-camp escapee who shadows one of his mates. So Indignation, set in the year after Sunset Boulevard (1950), seems perfectly in keeping with this trend. But these other films announce the voice-over’s posthumous status right away. Schamus does something a bit different.

In the source novel, Roth lets Marcus suggest that he’s dead about a quarter of the way through. Schamus’s screenplay drops hints that are, I think, fully noticeable only in retrospect. He creates a surprise that in turn motivates one of the two frames that surround the 1951 story action.

The front end of the inner frame is a brief combat skirmish in South Korea. A GI is pursued into a dark, nondescript building by a North Korean soldier. The action is difficult to discern, but we can see that the Korean is shot. Did the GI escape? The combat scene will be partially replayed near the film’s end, closing the frame the first one opened. The GI will be revealed as Marcus, who is dying from a bayonet thrust.

This isn’t merely a trick. In the 1940s filmmakers realized that some stories, if told chronologically, begin in rather slow and uninvolving fashion. But starting at a crisis late in the story’s causal chain, and then flashing back to what led up to it, can arrest our attention. Think of what The Big Clock (1948) would be like if we started not with the hero dodging around corridors trying to elude the police, but with his mundane office routine earlier that morning. So instead of starting with Greenberg’s funeral, Indignation grabs us with a brief and enigmatic piece of life-or-death action.

1940s frames are more explicit about the framing situation than the combat incident in Indignation. Yet Schamus evidently didn’t want to show Marcus lying there dying and reflecting on his life and leading into the film as a whole: too on-the-nose, and perhaps too obviously fatalistic. The shift to the Jonah Greenberg funeral frees the story action from what Henry James once called “weak specificity.”

There’s also the possibility that Marcus survives; we don’t see him die, even in the finale of the skirmish. The fact that the film can equivocate about whether our narrator is alive or dead emerges as a fresh treatment of the Afterlifer convention.

By raising the possibility of a dead narrator early on, Roth may make us view Marcus’s actions with more detachment, sub specie aeternitatis. The film version, I think, gets us more emotionally invested in Marcus, and this makes the eventual possibility (for me, the likelihood) that he has died more wrenching.

More than Marcus

Even in the enframed 1951 story action, our attachment to Marcus’s range of knowledge isn’t complete. For one thing, there are ellipses—most notably, the crucial scene in which he asks Olivia on their first date. There are also moments in which we run ahead of his awareness. When his mother meets Olivia, Schamus has controlled his actors’ eyelines so that even in a two-shot we’re not looking at the hero but rather at Mrs. Messner, who spots the girl’s wrist scar.

This is sharp visual storytelling. Marcus is unaware of his mother’s observation, but we’re prepared for her later admonition that he’s getting involved with a woman who will bring him misery. (Marcus: “She slit one wrist.” Mrs. M.: “One is enough. We have only two, and one is too much.”)

We’re also a beat ahead of Marcus in one neat shot that shows him stepping onto the quad as he’s facing expulsion. We see his future before he does; the marching ROTC students in the background catch our notice before a rack-focus brings him up to speed.

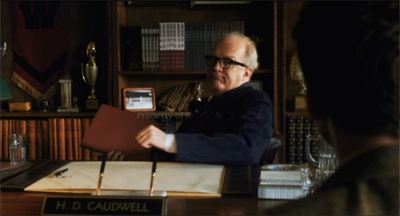

We’re also invited to see parallels that pry us a bit away from Marcus’s immediate experience. At two crucial moments, the adults trying to intimidate him—Dean Caudwell and his mother—come around behind him to keep wheedling.

The know-it-all debater has a chance when fighting face to face, but he crumbles when authority steers from behind.

Above all, our attachment to Marcus is qualified by a second frame, the one that wraps the whole fiction. This is wholly Schamus’s invention—a nested structure of the sort characteristic of 1940s films. At the very beginning and end of Indignation, we see an elderly Olivia in a care facility staring at the wallpaper dotted with a pattern of flowers in a water carafe. The image (also on a skirt she wears in the college portion) harks back to her impromptu bouquet for Marcus in the hospital.

But of course we’re inclined to ask: How likely is it that such a pattern would be used on wallpaper, and would it so neatly coincide with an item in Olivia’s past? We could then ask whether the pattern is in her imagination. (There is a sort of blurring and refocusing on the pattern, suggesting her optical viewpoint.) And since her scenes in the facility bookend the entire film—the Korean War frame, which in turn encloses the Winesburg College days—we might ask whether everything we’ve seen isn’t a product of her fantasy.

I’m not inclined to say that she has made up the whole movie. Indeed, if the wallpaper pattern is her projection, it would have to be so not just in her optical POV but also in the wider shot of her, the first image we get of her as an old woman.

Maybe this room, Caligari-like, is a total projection of her memory? More likely, it’s objectively there but triggers her recollection of Marcus. I’m still uncertain, but it does seem that giving Olivia the ultimate framing for the tale via their shared moment with the flowers suggests that Marcus, who at the end of his last monologue is calling out to her, has somehow finally made contact.

In any event, a purely formal cadence, completing the ABCBA structure and revisiting an ambivalent motif in the film, can balance, in aesthetic terms, the absence of answers to questions posed in the story world. This appeal to geometrical architecture and symmetrical construction is, since Henry James, another novelistic convention: art’s order can frame, if not completely account for, the disorder of life as it’s lived.

Goliath wins

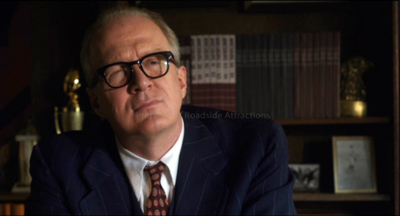

The sequence that has everybody talking is the sixteen-minute two-hander between Marcus and Dean Caudwell. It’s in the book, but Schamus and his players have brought to life the clash between idealism and suave, well-practiced bullying.

Straddling the film’s midpoint, this scene enacts the old proverb. “Old age and treachery trumps youth and skill.” It starts with a simple bureaucratic issue: Marcus’s transfer out of the dorm to a shabby, solitary room. This incident leads Dean Caudwell to charge him with stubbornness, lack of compromise, secrecy about his Jewish identity, friction with his family, intellectual arrogance, and cowardice. The whole cascade is punctuated by the Dean’s intermittent requests to stop calling him “sir.” It’s a verbal boxing match with Marcus gamely fighting on after quite a few low blows. Nobody who read Why I Am Not a Christian in their youth (as I did) can fail to be roused to self-righteous fury by Caudwell’s calm, close-minded innuendo.

Still, in such duels dialogue and performance need to be orchestrated with framing and cutting. Steve McQueen’s solution in Hunger (2008) is the use of a sixteen-minute profile long-shot, followed by a cut in to Bobby Sands’ hand picking up his cigarettes, and then a very tight close-up of his face as he continues speaking.

The interruption of the long take gives special prominence to a shift in the conversation, when Sands recalls his childhood. Later shots revert to shorter shot/ reverse-shot exchanges.

So framing and cutting can articulate phases of the drama. This Schamus does very carefully in the Indignation scene. To abbreviate:

Phase 1: More or less businesslike and polite: Why couldn’t Marcus compromise with his roommate? 180-degree cuts, with framing favoring Dean Caudwell–centered and dominating Marcus.

Phase 2: Caudwell gets personal. Why didn’t Marcus identify his father as a kosher butcher? Eventually he’ll accuse Marcus of intolerance. Here a fairly lengthy profile shot reminiscent of Hunger gives way to shot/ reverse-shot.

Phase 3: More personal probing: How does Marcus get along with his family? What about his sex life? And religion? After more shot/reverse shot, Marcus, sweating and feeling sick, rises to defend himself in close-up. That calls forth the closest shot yet of Caudwell.

Phase 5: Caudwell says Marcus’ sophistry will make him a fine lawyer. He comes to stand behind Marcus, putting his hands on his shoulders. Then he sits beside him, to drill in still more. Marcus, shaky, asks to leave.

Phase 6: At the door: Marcus is feeling sick. The dean asks if he’d like to play baseball. Finally Markus collapses and starts vomiting.

Schamus has saved shot/ reverse shot for when the scene heats up, and saved his close-ups for when things reach a pitch. This reminds us, as the Hunger scene does, that if you’re going to use a standard technique, hold off until it will do the most good. Ditto for the low angle on Marcus throwing up; that comes with more force if we haven’t already had low angles before. Schamus has let his cutting and shot scales amp up the drama without the crushing emphasis supplied by so many directors. Yes, I’m thinking of the barrage of close-ups in every dialogue scene of Jason Bourne. (Thanks to Paul Greengrass, Tommy Lee Jones’s facial contours qualify for Federal Drought Relief funds.)

I think that Indignation will be studied for years as an intelligent adaptation of Roth’s novel, but it ought also to be admired as a well-crafted work in its own right. It finds fresh ways of molding fiction techniques to the demands of cinema in general and Hollywood tradition in particular. And the film reminds us—or me, at least—how much contemporary filmmaking owes to the consolidation of “novelistic cinema” seventy years ago.

Thanks to James Schamus, Gustavo Rosa, and Lauren Hynnek for information and assistance, . For more on James’s career, see our entry.

Students of literature might find another novelistic analogy in Olivia’s explanation of her suicide attempt. It somewhat resembles the technique of free indirect discourse, when the third-person authorial voice adopts the language and syntax of the character’s thought. Roth employs this in the third-person tailpiece of his novel. Instead of “If only I hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for me at chapel!” we get “If only he hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for him at chapel!” Is it possible to have a cinematic equivalent: an objective vision that is pervaded by the character’s state of mind? Pasolini thought so, and suggested Red Desert, Before the Revolution, and Godard’s films as examples of it. Perhaps this flashback sequence counts as a case of Pasolini’s “free indirect subjective.”

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I briefly discuss the resurgence of 1940s storytelling strategies in recent studio cinema (pp. 72, 83). A general discussion of my interest in 1940s narrative is here. Elsewhere I make the case for Tarantino reviving 40s formats; for the importance of Afterlifers in the Forties; for nested narratives like that of Indignation; for replays that provide new information; and for the blurring of subjective and objective in Nightmare Alley.

For more on novelistic strategies in film, see “Watching a movie, page by page” and Kristin’s entries on the Hobbit films, all linked here.

Indignation.