Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO

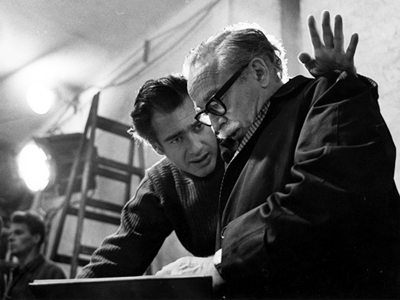

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo; John Frankenheimer and Dalton Trumbo.

DB here:

Who better to comment on the historical implications of Jay Roach’s Trumbo than our friend and collaborator on Film Art, Jeff Smith? He’s not only an expert on film sound, as he showed in his guest post on Brave, but he has written a book on the Hollywood blacklist. Jeff offers these observations on the film.

Last week, I was delighted to see that Bryan Cranston received an Oscar nomination as the star of Trumbo. Throughout the month of November, I was “johnny-on-the-spot” for local media interested in covering the new biopic about Dalton Trumbo. The story had a local angle. In 1962, Trumbo donated a large collection of scripts, notes, contracts, photos, and business correspondence to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Since then, scholars interested in the Hollywood blacklist have been making pilgrimages to Madison to probe Trumbo’s collection as well as the papers of five other members of the Hollywood Ten (Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner Jr., Herbert Biberman, Samuel Ornitz, and Alvah Bessie.)

I had done a lot of work with the collection, so I could do interviews with WMTV, WISC, The Wisconsin State Journal, and University Publications. Unfortunately I had not yet seen Trumbo, the Jay Roach film based upon Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography. I could talk about Trumbo’s life and career and the buzz I’d heard about the movie, but until it played Madison, I had to stay mum about the movie itself.

After a couple of weeks in distribution in limited release, Trumbo went wide just before Thanksgiving. Now that I’ve seen it, I am delighted to report that Trumbo merits every bit of the hype that surrounded it. To my mind, it is the best fictional film about the blacklist that Hollywood has yet produced.

Buoyed by a standout performance by Cranston, Trumbo is fast-paced and funny, and rather nimbly summarizes many of the political and industrial issues that led to the institution of the blacklist in 1947. It also showcases the effect that “unemployable” writers working on the black market had in undermining the rhetoric of the blacklist throughout the Cold War period. It became hard to say with a straight face that you were protecting American screens from the taint of Red propaganda when films secretly written by Communists were winning awards and topping the box office.

I was struck by some of the choices made by Roach and screenwriter John McNamara in bringing Trumbo’s story to the big screen. Although Trumbo’s career has been well documented by film scholars, Roach and McNamara faced the same challenges in adapting Cook’s biography that any filmmaker does in transforming a literary property into a classical narrative structure. How do you make Trumbo an active, goal-oriented protagonist despite the fact that he was the victim of historical circumstance? How do you deal with the welter of historical actors and subplots that populate Cook’s biography? How do you boil down a complex historical situation into a clear, transmissible narrative?

Witnesses, friendly and otherwise

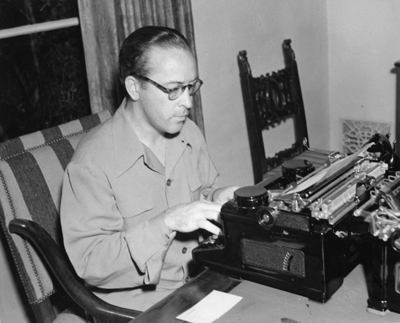

Dalton Trumbo at work.

Like many contemporary Hollywood biopics, Trumbo doesn’t try to convey the full sweep of its subject’s quite colorful life. It omits reference to young Dalton’s Christian Scientist upbringing, his early toils in the Davis Perfection Bakery, or even the publication of his first story in 1933. Indeed, the film also makes only offhand references to Trumbo’s early achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. These are briefly acknowledged near the film’s start through a series of shots in Trumbo’s office at the Lazy-T Ranch that reveal his award for Johnny Got His Gun and his Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle.

Instead the film focuses on the period of Trumbo’s career during which the screenwriter became one of Hollywood’s sacrificial lambs at the altar of HUAC’s anti-Communism. When the film begins in the mid-forties, Trumbo was the most highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood, earning $75,000 per script. In today’s currency, that amounts to about $800,000 per picture, a remarkable sum for someone under studio contract.

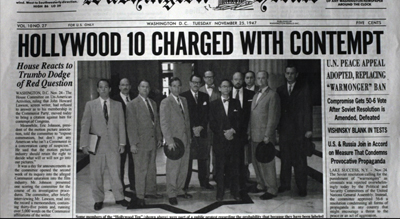

Just a few years later, Trumbo would appear as an “unfriendly witness” during hearings conducted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in October of 1947. As a result, he’d eventually be convicted of Contempt of Congress charges and sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky.

Although HUAC was concerned about the potential subversion of American screen content, it was not, in fact, illegal to be a member of the Communist Party. It was, however, a criminal offense to advocate for the overthrow of the American government according to the provisions of the Alien Registration Act (aka the Smith Act) passed in 1940.

About six months after HUAC concluded their hearings on Hollywood, a dozen Communist Party leaders were indicted for Smith Act violations. Defendants insisted that political change in America could be accomplished through democratic process and constitutional principle. But prosecutors claimed these statements couldn’t be trusted since Communists employed “Aesopian language” and therefore did not really mean what they said. The attack proved successful and effectively criminalized membership in the Communist Party as a result. Since any individual’s denial of revolutionary rhetoric would be viewed with suspicion, you were likely seen as guilty of the Smith Act if you simply owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto.

Even before the Foley Square trials, as they came to be known, many of the Communist Party’s rank and file, including the Hollywood Ten, also feared that they would be prosecuted on similar grounds if they admitted their membership. This proved to be one factor that favored the Ten’s failed “first amendment” defense. True, they risked getting cited for Contempt of Congress. But that had the prospect of looking more dignified than simply being hauled off in cuffs on Smith Act charges.

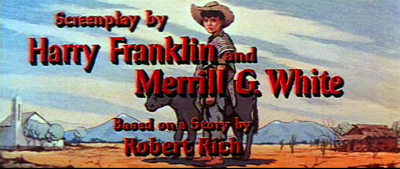

When he returned from prison, Trumbo encountered an industry that wanted him, but not his name on the credits. Producers recognized his talent, and he continued to write through the circuitous network of fronts and pseudonyms. Trumbo would win two Oscars for his work as a black market screenwriter: one for the Gregory Peck/Audrey Hepburn classic, Roman Holiday (below) and another for a Disneyesque “boy and bull” story, The Brave One.

By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s name would once again grace movie screens as the credited screenwriter on Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and on Otto Preminger’s Exodus. This moment essentially ended what remained of the Hollywood blacklist. In moving from the limelight to the shadows and back again, Trumbo’s life had the kind of plot arc that Hollywood loves. It’s a story of redemption in which the hero overcomes overwhelming odds to regain the professional respect and recognition he’d been denied.

Although all of this suggests that Trumbo is a pretty conventional biopic, it’s quite unconventional in its treatment of the blacklist. As the late Jeanne Hall noted years ago, Hollywood’s representation of this dark chapter of its past was surprisingly evasive, getting on the right side of history but for all the wrong reasons.

Bad Faith in Appleton

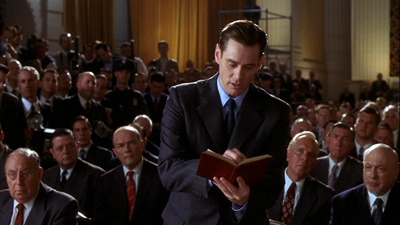

The Majestic (1999).

In titles like The Way We Were, The Front, and Guilty by Suspicion, filmmakers pulled a “bait and switch.” They substituted obvious cases of injustice for the much messier questions posed about HUAC’s abrogation of basic civil rights protections. The Hollywood Ten tried to defend themselves on First Amendment grounds, questioning whether HUAC itself had the right to invade their privacy or to limit their freedom of assembly. But in most of these earlier films about the blacklist, HUAC’s inquiry eventually entangles someone who was never a member of the Communist Party. In The Way We Were, the WASP-y Hubbell comes under suspicion for his relationship with the Jewish radical, Katie. In The Front, Howard comes under suspicion after selling black market scripts by Communist writers under his own name. Both of these instances present obvious cases of individuals wrongfully accused. They recruit our sympathies for characters that suffer as a result of HUAC’s tactics, but gloss over more fundamental questions about whether someone should be denied employment on the basis of their political beliefs.

No film, however, displays the equivocation evident in previous representations of the blacklist as vividly as Frank Darabont’s The Majestic. The protagonist, Peter Appleton, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has just been named by the committee. Distraught, he takes a drive out of Hollywood, but has an accident en route. Suffering from amnesia, Appleton finds himself in the small town of Lawson, California where is mistaken for Luke Trimble, a soldier killed in action some nine years earlier. Appleton becomes immersed in the Lawson community, helping his “father,” Harry, restore the small town theater that gives the film its title. Prompted by a combat film shown in the Majestic, Appleton regains his memory, and confides the truth of his situation to his new girlfriend. After his car is discovered, federal agents give Appleton a summons to testify about his Communist affiliations.

During the climax, Appleton appears before HUAC with the aim of clearing himself. Congressman Elvin Clyde confronts Appleton with evidence that he attended a meeting of the “Bread Instead of Bullets” club. Appleton pleads innocence, saying he only went because he was a “horny, young man” seeking to impress his date, Lucille Angstrom. Just as he is about to deliver his prepared statement purging himself of Communist associations, Appleton changes his mind. Instead he gives an impassioned speech that cites his First Amendment rights and denounces the investigation as a betrayal of America’s real ideals. Appleton saunters out of the hearing to the loud applause of onlookers. Yet Appleton’s lawyer later tells him that Angstrom is currently a CBS producer on Studio One, and his reference to her as a member of the Communist front organization is viewed as cooperation with the Committee.

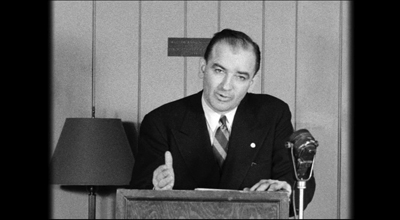

In The Majestic’s civic fantasy, the committee hearing revives the “wrongly accused” trope seen in earlier blacklist films. Worse, it shows its hero successfully using the First Amendment legal defense that had spectacularly failed when the Hollywood Ten used it during the 1947 hearings. Moreover, because Appleton is a political naïf, his inadvertent naming of names redounds to his benefit. Given the film’s hopelessly confused politics, perhaps there is unintentional irony in the fact that Appleton is also the name of the Wisconsin hometown of Senator Joseph McCarthy (below), the man synonymous with the Cold War’s anti-Communist campaign.

Trumbo, in contrast, doesn’t pull any punches. The film condemns HUAC’s activities not because it was prone to wild, unproven accusations like those of McCarthy, but rather because the very nature and essence of its inquiry was itself an abuse of power. The movie does nothing to deny Trumbo’s guilt. Indeed, the real-life Trumbo freely admitted it. In the 1976 documentary Hollywood on Trial, Trumbo described his reaction to his trial thusly: “As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since.”

Yet, while not excusing Trumbo’s actions, the film dramatizes the debilitating effects of being blacklisted, both in his professional and personal life. The burden of Trumbo’s black market work put a strain on his marriage and his family, all of whom were enlisted to perform services he himself could not do publicly.

The blacklist: More than Red-baiting

Besides providing a more accurate picture of Red-baiting and its effects, Trumbo also proves remarkable in making passing reference to some of the important secondary causes that eventually led to the blacklist. An early scene, for example, shows Trumbo (above) on a picket line during the vituperative Congress of Studio Union strikes that took place in 1945. Film historian Jon Lewis argues that one reason for the studio’s cooperation with HUAC’s investigation was that it served their interests in their long-term relationship with Hollywood’s craft guilds. Once Communists within the film industry’s labor unions became targets of government scrutiny, only the more moderate factions remained. Whether or not HUAC’s investigation was a direct cause, Hollywood did not experience another strike until more than four decades later.

Trumbo refers to another cause of the blacklist: anti-Semitism. Although it was something of a stereotype, Communists were popularly associated with European Jews. In fact, when Warner Bros. released I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, several moviegoers wrote studio head Jack Warner complaining that the film repeated the lie that all Jews were Communists. Said one Julius Newman of Roxbury, Massachusetts: “I demand that this dangerous, rotten, and libelous bit of propaganda be withdrawn immediately before some Jewish mother somewhere, gets her son’s skull cracked for Mother’s Day.”

The perception that anti-Semitism was an underlying cause of the blacklist was aided by the fact that three of the Committee were members of the Ku Klux Klan at the time of the 1947 hearings, including the Chair, J. Parnell Thomas. Moreover, in a speech before the House of Representatives, another HUAC member, Mississippi Democrat John Rankin, attacked members of the Committee for the First Amendment, who had lobbied on behalf of the Hollywood Ten. Rankin claimed that certain performers were suspect because their Anglicized names hid their actual Jewish origins:

One of the names is June Havoc. We found that her real name is June Hovick… Another one is Eddie Cantor, whose real name is Edward Iskowitz. There is one who calls himself Edward Robinson. His real name is Emanuel Goldenberg. There is another here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg.

Screenwriter John McNamara wrote a similar speech for Trumbo, but placed it in the mouth of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. When MGM boss Louis B. Mayer reminds Hopper that the legal situation was complicated by the fact that several of the Hollywood Ten had contracts, she responds:

Then how about I make crystal clear to my thirty-five million readers who runs Hollywood and won’t fire these traitors? How about I name names, real names? Like yours, Lazar Meir; or Jack Warner, Jacob Varner; Sam Goldwyn, Schmuel Gelbfisz.

The presence of Hedda Hopper in Trumbo hints at a third underlying cause of the blacklist: the role of the trade press and gossip columnists, who prosecuted and enforced it. Hopper was not alone in this endeavor. Publishers like Billy Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter and columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan “cheered” HUAC’s efforts from the sidelines. They also helped the enforcement of the blacklist once it was instituted, calling public attention to the surreptitious presence of banned writers on the black market.

All of these elements in Trumbo’s script make it a richer, more sophisticated depiction of the Hollywood blacklist than that offered by its predecessors. They also remind us that its operations were about more than just politics. Once the blacklist was established, studio bosses gained the upper hand in their dealings with labor, gossipmongers used rumor and accusation to fill column inches and sell papers, and anti-Semites exploited the common association of Communism and Jewish intellectuals to thwart activism among progressives, including those in the Civil Rights movement.

In sum, Trumbo offers a more nuanced sense of the various factors at play at the time of the blacklist than virtually all of its cinematic predecessors. This makes it all the more surprising then that the film nonetheless rewrites history in other ways. In an effort to both streamline and personalize its protagonist’s story, Trumbo invents new characters, revises the order of historical events, and shorts the achievements of other black market screenwriters who also contributed to the blacklist’s ultimate demise.

The eleventh member of the Hollywood ten

Although most film audiences expect that movies will generally portray historical events with some degree of accuracy, Hollywood cinema rewrites history all the time. Despite the fact that this is common practice, some films that take such liberties are hurt by negative publicity, especially around awards time. Recall the controversy surrounding Selma’s depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as an opponent of Martin Luther King’s famous march rather than as a “behind the scenes” ally. Some believe that the loud complaints coming from the LBJ camp cost director Ava DuVernay an Oscar nod.

Trumbo is no exception to this principle, even though it has been unusually forthright about the changes made to the historical record. My spidey senses were alerted to this during the movie when they introduced Louis CK’s character as “Arlen Hird.” I’d never heard of Arlen Hird.

Both in interviews and in an article in the New York Times, screenwriter John McNamara has acknowledged that Hird is a composite character, whose traits and experiences are based on five other members of the Hollywood Ten. Louis CK, for example, physically resembles the real-life Alvah Bessie, who, like the character, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish civil war.

Moreover, when Hird is in prison, he hears a radio broadcast of Edward G. Robinson’s “friendly” testimony. Robinson calls him “the top fellow who they say is the, uh, commissar out there,” a swipe that blacklist historians would immediately associate with John Howard Lawson. And sadly, like Samuel Ornitz, Hird dies after battling cancer, having never seen the blacklist come to its ignoble end.

As Nicolas Rapold observes in the Times, Hird is meant to stand in for other Communist screenwriters whose attitudes were more doctrinaire than Trumbo’s. Yet I believe the real purpose of using a composite character is to simplify the historical record to make it more digestible for the viewer. Rather than tracing out Trumbo’s relation to all of the eighteen other “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed by HUAC, McNamara opts to consolidate them into a single character. Such a decision makes some intuitive sense, since viewers would be hard pressed to keep tabs on a parade of many characters. By creating Hird as a composite, Trumbo’s interactions with him gain vividness and salience.

Still, McNamara’s narrative technique is merely one approach among a larger menu of options, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. He could have treated the Hollywood Ten as a group protagonist, who all share the same goal in legally challenging HUAC’s authority. Such a gambit, though, would have displaced Trumbo from the center of the story early on. That decision would have weakened the causal motivation behind his later emergence as a black market crusader.

Alternatively, McNamara could have dramatized Trumbo’s individual interactions with Bessie, Lawson, and Ornitz, et.al., using a superimposed title to identify each one. The gain in accuracy, though, would likely mean a loss of dramatic clarity and a mildly more self-conscious style of narration. More important perhaps, it also would make for a less emotionally engaging story. The film shows Hird confiding in Trumbo at the Lazy-T ranch, participating in the Ten’s legal strategy, serving his prison term, and undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The accumulation of these details provide for a more fully fleshed out character. There’s also the opportunity to feel empathy for Hird’s children at his funeral, an effect that couldn’t have been as focused if Hird’s problems were scattered among separate individuals.

None of this is meant to suggest that McNamara absolutely made the right choice in deciding to treat so many members of the Ten as a composite. Rather, it is simply the recognition that such a technique is the result of a deliberate choice and further that one creative decision can lead to a cascade of others. Had McNamara stayed doggedly faithful to the historical record, Trumbo would have been a different film, but perhaps not a better one.

Perhaps we should recognize that screenwriters often must adapt historical narratives in the same way that they adapt literature. And the same sorts of questions about fidelity will bedevil us as when films change details of our favorite novels and stories. Rather than being dogmatic in expecting that historical films stick close to the facts, maybe we simply should ask whether the film is faithful to the spirit of the historical record, especially when its creators are so open and honest about the changes they made. Such a stance would at least recognize the difficulties faced by screenwriters in balancing the weight of classical narrative conventions against the strict measure of historical accuracy. If, as many screenwriters argue, films differ from literature in their emphasis on conflict and action, then the decision in Selma to treat LBJ as an obstacle to Martin Luther King’s goal makes a certain dramatic sense. Here again, one can debate the merits of that creative choice. But at least we do so with a fuller understanding of why such choices are made in the first place.

Get me rewrite!

Besides creating composite characters, McNamara rewrites history in other ways. Perhaps the most obvious is when he creates a scene in prison between Trumbo and HUAC chair, J. Parnell Thomas, which never actually happened. True, Thomas was convicted on corruption charges and was sent to federal prison. But he served his term in Danbury, Connecticut rather than Ashland, Kentucky where Trumbo was incarcerated.

In this case, the real-life story proves more entertaining than what appears in the film. While at Danbury, Thomas encountered two other members of the Hollywood Ten – Lester Cole and Ring Lardner, Jr. — serving their time on Contempt of Congress charges. Upon seeing Thomas working in the prison yard, Cole made a wisecrack that led the former HUAC chair to respond, “I see that you are still spouting radical nonsense.” Cole’s sharp retort: “And I see you are still shoveling chicken shit.”

In other cases, McNamara revises the chronology of events. In the film, Trumbo first meets with the King Brothers, Frank and Hymie, just after he is released from prison. In reality, Trumbo started working for the King Brothers just weeks after his HUAC testimony. Almost immediately after being suspended by MGM, Trumbo did black market work on the screenplay for the King Brothers’ cult classic, Gun Crazy, using fellow writer Millard Kaufman as a front. With Kaufman serving as intermediary, the Kings likely did not know of Trumbo’s involvement. But the brothers began working directly with Trumbo shortly thereafter. In fact, Frank King personally visited the Lazy-T ranch just prior to the Trumbo’s departure for prison, offering to pay him $8,000 to write the script for Carnival Story.

Trumbo coyly acknowledges the screenwriter’s contribution to Gun Crazy by featuring posters of the film in several shots. But by revising the historical circumstances of Trumbo’s first involvement with the Kings, the film more or less denies him actual credit attribution, ironically engaging in the same sort of opportunism displayed by the producers who surreptitiously hired him.

McNamara’s most significant changes to blacklist history, though, involve omissions. Trumbo’s Oscar victory for The Brave One is well documented and the episode – both in the film and in real-life – neatly captures his role as industry gadfly. But the same year that the mysterious “Robert Rich” won the Academy Award for Best Original Story, Michael Wilson also was nominated for a project for which he was publicly denied screen credit.

Wilson had completed a first draft of Friendly Persuasion for director Frank Capra in 1946, but no film was made from the script until producer/director William Wyler took over the project in 1955. When it came time to determine the screenwriter credit, Wyler suggested that it go to Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West for their extensive revisions, including many rewrites completed on set during shooting. When Wilson became aware of this, he immediately protested Wyler’s decision and forced arbitration by the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild ruled in Wilson’s favor, but also reminded the film’s distributor, Allied Artists, that they could legally deny credit to any screenwriter who had failed to clear himself before HUAC. When Friendly Persuasion was released in 1956, its only writing credits read “From the Book by Jessamyn West.”

Despite a good deal of press coverage of the dispute, the incident might have been a mere blip on the cultural radar if not for the 1957 Oscar nominations. When they were announced, a film with no credited screenwriter unexpectedly received a nomination for a screenwriting award. And with public acknowledgement of Wilson’s contribution to Friendly Persuasion more or less verboten, the text of the nomination simply said the writer was ineligible under Academy rules.

Worried that a public victory by a blacklisted writer would give the industry a big ol’ black eye, the Academy reportedly instructed Price Waterhouse to excise the nomination from the Oscar ballots that were sent to voters. Yet, even though the Academy essentially rigged the vote against Wilson, Groucho Marx offered an incisive quip about Wilson’s situation at the Writer’s Guild Awards banquet held about two weeks before the Oscars. Said Groucho, “The Ten Commandments. Original story by Moses. The producers were forced to keep Moses’s name off the credits because they found out he had once crossed the Red Sea.” Given all the effort that went into preventing Wilson from receiving the award, Trumbo’s Oscar win as “Robert Rich” must have tasted even sweeter. The award was given in absentia by Deborah Kerr, and Jesse Lasky, Jr. accepted it.

Moreover, the Rich incident was hardly the last humiliation that the Academy would suffer. The very next year novelist Pierre Boulle received a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination for The Bridge on the River Kwai, which was based on his book. But Boulle had been a front for Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, who had taken the assignment as black market work for producer Sam Spiegel. When Boulle’s name was announced as the winner, the novelist was nowhere to be found. Instead, Kim Novak accepted the award on his behalf. But insiders knew exactly why Boulle was absent. As someone who wrote and spoke in French rather than English, his stumbling acceptance speech would have exposed the hypocrisy by which Foreman and Wilson were denied an award that they merited. (Sadly, neither Foreman nor Wilson would live to see their work duly recognized. In 1984, the Academy posthumously recognized them as the true authors of Kwai’s screenplay.)

Nathan E. Douglas = ?

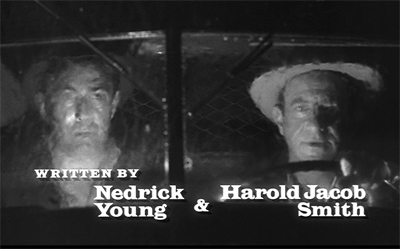

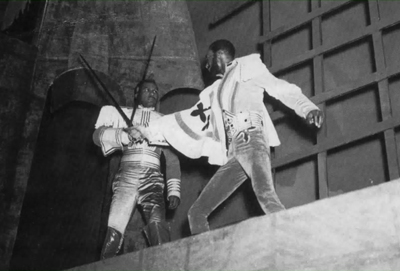

The original credits sequence of The Defiant Ones (1958) listed Nedrick Young as a coauthor under his pseudonym Nathan E. Douglas. He appeared in a bit part coinciding with his credit listing, along with coauthor Smith, in the cab of the truck. Video versions such as this have restored his name.

Things didn’t end there. The Oscar nominations in 1959 saw yet another brewing controversy regarding eligibility of a black market scribe. The writing team of Harold Jacob Smith and Nathan E. Douglas earned a nod for Best Original Screenplay for The Defiant Ones, even though the latter was a pseudonym for blacklisted writer Nedrick Young. If anything, Young’s participation in the making of The Defiant Ones was signaled by producer-director Stanley Kramer’s giving him a notable cameo in the film. During the opening credits, Young and Smith are both seen as prison guards riding in the front seat of a truck used to transport convicts. In a rather coy gesture, when the film’s writing credits are shown, Young’s pseudonym “Nathan E. Douglas” is superimposed over the man himself. Even though the general public didn’t know Young from Adam, his cameo made his participation an open secret in Hollywood.

During awards season, Young as “Nathan Douglas” collected a lot of hardware, including awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Writer’s Guild of America. With the nominations imminent, leadership within the Academy recognized that a third straight public relations disaster was in the offing. Just before Christmas in 1958, former Academy president George Seaton approached Young and Smith seeking assistance in overturning the Academy bylaw prohibiting blacklisted personnel from eligibility for awards. For his part, Trumbo himself stayed abreast of the situation and even rescheduled a media interview order to avoid fanning any flames of opposition from within the Academy.

On January 15, 1959, Seaton, Young, and Trumbo all got their wish as the hated bylaw was officially rescinded, passed by the Academy’s Board of Governors with near unanimous support. Two days later, Trumbo confirmed to newsman Bill Stout that he was, indeed, Robert Rich. On Oscar night a few months later, Young enjoyed the spotlight in a way that had been denied his predecessors. And when The Defiant Ones won the Oscar for the Best Story and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, Young strode to the podium along with Smith and offered a humble thank you. Ward Bond, one of John Wayne’s allies in the Motion Picture Alliance for American Ideals, observed: “They’re all working now, all these Fifth-Amendment Communists. We’ve just lost the fight. It’s as simple as that.”

Where does all of this backstory fit into the story told in Trumbo? As it turns out, nowhere. In choosing to concentrate on Trumbo’s story, the movie keeps all of this rich contextual material offscreen. As is often the case, the historical realities surrounding the end of the Hollywood blacklist were much denser, messier, and more complex than what can easily fit into a standard two-hour film. Classical Hollywood narrative, with its emphasis on goal-orientation and clearly motivated, causally linked events, tends to nudge screenwriters away from the sprawl more often found in novels or television miniseries. In the case of Trumbo, screenwriter John McNamara likely opted for the virtues of clarity and concision. He concentrated only on those incidents that directly involved the titular character, eliminating or minimizing anything that would detract from that narrative focus.

That being said, the creative choices of McNamara and director Jay Roach are, above all, choices. The screenplay for Bridge of Spies, for example, manages to convey something of the complex bilateral negotiations that linked the downing of U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers with the seemingly unrelated espionage case of KGB officer Rudolf Abel. One could imagine Roach and McNamara devising very brief scenes of Wilson, Foreman, and Young in their Academy imbroglios. Or alternatively, the film might have included Trumbo’s voiceover reading the text of his actual letters to Wilson, many of which commented on the perpetually changing conditions of the black market. As before, the inclusion of such material wouldn’t necessarily make Trumbo a better film. But it would make it a different one.

Although Dalton Trumbo led the fight against the blacklist, often using the industry’s greed, hypocrisy, and mendacity against itself in the process, my brief synopses of these other screenwriters’ Academy Award travails show that he was not alone. Many individuals taking small incremental actions led to the blacklist’s end. It wasn’t smashed; it crumbled through erosion. The fact that one of Hollywood’s “untouchables” was able to openly accept a major industry award made open screen credit a logical next step. Dalton Trumbo happened to be the lucky individual to regain his name without having to bow and scrape before HUAC. But even he knew it could just as easily have been Nedrick Young. Or Michael Wilson. Or Albert Maltz.

Come Oscar night on February 28th, if Bryan Cranston is lucky enough to hoist the Best Actor prize above his head, it will be a fitting tribute to a man whose struggles with this same institution helped to define him and his era. Yet an Oscar victory would also pay tribute to all those whose stories have not reached the screen, but whose grit and determination made Trumbo’s triumph possible. And Mr. Cranston, if you get to deliver that acceptance speech, be sure to remember all those unsung heroes that joined Trumbo in the fight.

Trumbo is based on Bruce Cook’s biography, which was first published in 1977. Readers should also check out Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo’s massive, exhaustively researched new biography, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical. Ceplair is also the co-author, with Steven Englund, of the standard work on the Hollywood blacklist itself, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics and the Film Community, 1930-1960. My book, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds, also considers Trumbo’s contribution to Spartacus.

Trumbo’s collection of correspondence, speeches, business papers, scripts, and photographs is held at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. A rich sampling of material from it is available here. Several of the photos in this entry come from the WCFTR collection. Go here to listen to excerpts from his HUAC testimony.

Excerpts from John Rankin’s infamous speech about Jewish actors in Hollywood can be found in Gordon Kahn’s Hollywood on Trial: The Story of the Ten Who Were Indicted. Trumbo himself commented on the role of anti-Semitism in HUAC’S investigations in The Time of the Toad: A Study in Inquisition in America.

Franklin Leonard interviewed John McNamara last November about his work on Trumbo for his Black List Table Reads podcast. Nicolas Rapold offers a useful guide to the individuals profiled in Trumbo, including its composite characters. If you’re interested, you can see actual footage of the announcements of various screenwriting awards at the Oscar ceremonies of 1957, 1958, and 1959.

For more on how adaptation works, see the thirteenth chapter of the new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming next week. That chapter is available for courses as an add-on to both the printed edition and the McGraw-Hill electronic edition.

Trumbo.

Deadlier than the male (novelist)

DB here:

It’s about time! Sarah Weinman, editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives (already praised in these precincts) has brought out a two-volume set devoted to women crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s.

It’s not that these authors are utterly unknown. Popular in their day, some retained a following for a few decades, and Patricia Highsmith has become an enduring figure. Yet the never-ending frenzy for male-oriented noir in books and movies has led us to neglect what these writers and their peers accomplished. In the online essay “Murder Culture” I argued that we’ve probably overemphasized the hardboiled detectives and brutalized losers, and we’ve not paid enough attention to the accomplishments of other writers. The rise of the psychological thriller was central to 1940s popular culture.

Granted, it wasn’t only gynocentric. The thriller assumed exciting shapes in the hands of talented men like Patrick Hamilton, Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin. But the 1940s saw the emergence of a powerful cadre of women writers, many of whom started writing “pure” stories of detection but decided that suspense would be their forte. Surely they were encouraged by the success of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, the best-selling mystery novel before Mickey Spillane came on the scene. But these suspense-mongers avoided mimicking Mignon Eberhart and other predecessors in the innocent-girl-in-a-spooky-house tradition. These new talents saw menace crouching behind the windows of drab houses and apartment blocks. Out of several tendencies I tried to sketch in that essay, they forged a tradition of what Weinman calls “domestic suspense.”

The Library of America volumes give us a fine occasion for appreciating what they accomplished.

Artisans of suspense

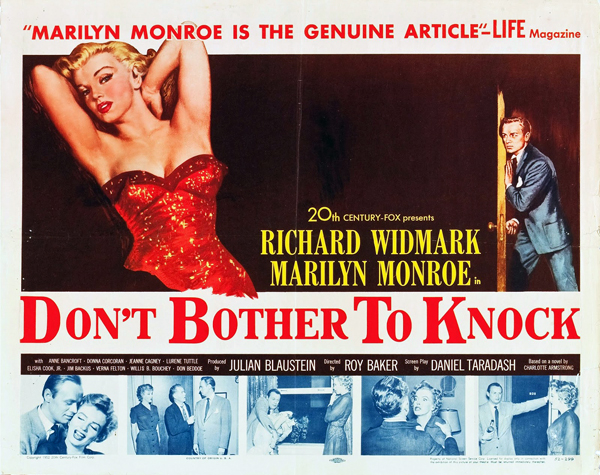

You might say that Double Indemnity and Out of the Past are quintessentially 1940s-1950s films, and I’d agree. But other important films were derived from works by women writers. The list of Highsmith adaptations, starting with Strangers on a Train (1951), is too long to recite here, but let’s remember that Charlotte Armstrong provided source novels for The Unsuspected (1947) and Don’t Bother to Knock (1952, from Mischief), as well as for Chabrol’s La Rupture (1970) and Merci pour le Chocolat (2000). Filmmakers produced now-classic versions of the Dorothy B. Hughes novels The Fallen Sparrow (1942), Ride the Pink Horse (1946), and In a Lonely Place (1950). The prolific but less famous Elizabeth Sanxay Holding gave us The Blank Wall (1947), adapted twice (The Reckless Moment, 1949, and The Deep End, 2001). Dolores Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold (1958) yielded the implausible basis for Godard’s Band à part (1964). Helen Eustis’s The Fool Killer (1954) became a 1965 film. And of course Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) became a monument of studio moviemaking.

The thriller, you could argue, makes more engaging cinema than the straight detective story. Much as I admire cinematic sleuths like Sherlock Holmes, Nick Charles, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and particularly Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, pure mystery plots need a lot of bells and whistles to keep from being simply a matter of following the detective as he moves from place to place asking questions and dodging blows on the head. The 1940s tales of espionage, women in peril, serial killings, household anxieties, warped husbands and crazy wives and guileless governesses and all the rest have left a stronger legacy today. We live in the Age of the Thriller, as a glance at any bestseller list will indicate. The recent death of Ruth Rendell, arguably Highsmith’s only top-flight competitor, can only remind us of how the genre has flourished for decades.

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

The Library of America collection has rounded up several contemporary purveyors of suspense to write brief online appreciations of the titles in the collection. These are well worth reading. On each page further links take you to fresh material. There’s also a succinct introduction by Weinman. The print editions include her judicious career summaries, as well as notes on allusions and citations in each novel.

For readers interested in how women’s cultural roles are represented in fiction, these books provide a field day. Several of the professional commentaries suggest that the authors injected social criticism into their works. These writers are far more willing to get inside men’s heads than the hard-boiled boys are to think like a woman, so you can see the macho attitude in a new light. Here’s how Dorothy B. Hughes in The Candy Kid (1950, not in this collection) describes her hero:

Just as he was thinking that he’d better go in and buy a pack, wait for Beach in the air-cooled coffee shop, the girl came around the corner. She was tall, almost as tall as he, but he took a quick look at the pavement and saw that she was propped on heels. That made him feel more male.

Very often these writers take certain stereotypes, both male and female, and submit them to pressure through their craft. Others seem to accept those stereotypes and employ them for their own storytelling ends. Those ends are very much worth our attention.

We know that several of these writers were self-conscious artisans. Hughes and Armstrong wrote articles reflecting on mystery and suspense, while Hughes also wrote a sharp biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. Hughes also conducted a course on mystery writing at UCLA in the 1960s; she invited Vera Caspary in for a guest lecture, and Caspary’s advice makes for fascinating reading. Highsmith’s notebooks, preserved at the Archives littéraires in Switzerland, are filled with meditations on story problems, and she wrote as well a book-length manual, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966, 1981). I don’t think that any hard-boiled writers of the era have left such systematic reflections on the nuts and bolts of their work.

Once we pay attention to technique, we can see how these writers rework topics and concerns of the day. For example, we could talk a long time about how social roles induce women to assume a split identity: one face for friends and family, another that resists the masquerade. But these, after all, are mysteries, so that divided identity has to be dramatized—or better yet, played with and teased out for the sake of suspense and surprise. It’s remarkable that two of the books in the collection exploit the syndrome of Multiple Personality Disorder, which becomes part of the final surprise. Another, Laura, makes an enigma of the woman’s inner life by virtue of dispersed viewpoints.

If we want to learn about storytelling, we can usefully look at how writers manage traditional demands of craft. These books “say what they say” in and through technique—narrative form, literary style. The experience that results can be an enduring achievement.

Pronoun trouble

No use asking if the crime writer has anything of the criminal in him. He perpetuates little hoaxes, lies and crimes every time he writes a book.

Patricia Highsmith

Start with style—important in all storytelling, but posing some fascinating issues in the domestic thriller.

One problem faced by all these writers was: How to avoid the sentimental style of romantic suspense writers? Here’s a typical passage from Mignon G. Eberhart’s Another Woman’s House (1946).

She said, blindly choosing trite and inadequate words, “You cannot change your own sense of loyalty, of your own creed and code. It’s bred in your bone; it’s part of your body.”

He understood all the argument below it. He understood too that it was a fundamental argument in his own heart. His eyes deepened, searching her own. He said suddenly, “Myra, you must see this sensibly; you must be realistic and . . .”

“Oh, Richard, Richard!” She cried despairing, and put her head against his shoulder.

There’s some of this novelettishness in Armstrong, as in this bit from Mischief:

When a fresh scream rose up, out there in the other room in another world, Ruth’s fingertips did not leave off stroking into shape the little mouth that the wicked gag had left so queer and crooked.

Hughes and Hitchens, I think, leaned toward the hardboiled laconicism of Hammett and Cain, though without the slanginess. In The Horizontal Man, Eustis tries for a brittle, satiric tenor and some Hollywoodish banter between a reporter and a college woman. Highsmith was adamant in refusing what she called a “pulp” style. Hence her flat, spare simplicity. (Funny, though, since she started out writing comic books for the company that would become Marvel.)

Stylistic options can lie very far down. For years I’ve been curious about what fiction writers call their characters on first entrance. It’s a fundamental creative choice, and it’s absolutely forced: you have to call them something. And what you call them matters.

Here’s the beginning of Armstrong’s Mischief:

A Mr. Peter O. Jones, the editor and publisher of the Brennerton Star-Gazette, was standing in a bathroom in a hotel in New York City, scrubbing his nails. Through the open door, his wife, Ruth, saw his naked neck stiffen….

Cozy, our relation to this Mr. and Mrs. Jones: Mischief gives their first and last names. So far, no reason to be apprehensive. But here’s the start of Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold:

The first time they drove by the house Eddie was so scared he ducked his head down. Skip laughed at him.

Here a relationship is defined through laconic action: we’re on a first-name basis with the pair. It’s as if we’re riding in the back seat.  Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

The man in the dark blue slacks and a forest green sportshirt waited impatiently in the line.

The girl in the ticket booth was stupid, he thought, never had been able to make change fast.

Highsmith is more ominous: No names, just a man as if seen from across the sidewalk. Yet we can’t say the presentation is “objective” because we’re given his annoyed thoughts about the ticket girl. So we are forced to ask: If I’m in his head, why don’t I know who he is? And why is he in a hurry?

And finally, the opening lines of Eustis’ The Horizontal Man:

The firelight played over all the decent, familiar objects of his everyday life; he viewed them desperately, looking for some symbol of succor. The firelight played on his rolling eyeballs, the careless tendrils of his black hair. “Oh now,” he said, “Oh now, I say, look here…” trying to summon a tone of commonplace to breast the tide of nightmare that was rising in that room.

Eustis dispenses with everything but he in describing something terrible going on. Not only do we not know who’s suffering, but we won’t know for some time. This, like the Highsmith, might be called “pronominal mystery”: not knowing anything about who’s in danger, we sense the danger as a pure force swallowing up trivialities of identity.

Most manuals of fiction-writing start by reviewing the bigger choices, like first- or third-person narration, but note that even within third-person storytelling, these passages bristle with different implications. Each of these openings puts us in a different relation to the characters picked out.

The storyteller makes a choice about how to name the actors in the scene, and that choice leads to others: the scene is built out the premises of what have launched it. Ruth, who studies her husband Peter at the mirror, will become one conduit of information within Mischief. Skip, who laughs at Eddie as they size up the home they’ll invade, will bully his partner throughout Fools’ Gold. The man in the slacks and sportshirt will drop out of The Blunderer for several chapters. So no need to name him yet; magnify the mystery. And the opening scene of The Horizontal Man will continue with personal but untagged pronouns—a she will be picked out too—as the full awfulness of the action emerges.

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

Fussy as these details are, they’re what I mean by craft. The verbal texture of any piece of fiction depends on dozens of such minute judgments. Just as in film every cut, camera movement, and actor’s glance matters, so does every word in a prose narrative. These writers understood that what we learn, syllable by syllable, can be a potent source of uncertainty and suspense.

Who sees and who knows?

The whole intricate question of method, in the craft of fiction, I take to be governed by the question of the point of view—the question of the relation in which the narrator stands to the story.

Percy Lubbock, The Craft of Fiction

In mystery fiction, management of point of view is critical. Not only will it weave the moment-by-moment verbal tissue, but it provides the large-scale parts that present the overall action. Where the Had-I-But-Known romance tends to be restricted to a single character, often through first-person narration, domestic suspense employs other options. It’s significant that of these eight novels, only one, Laura, employs first-person narration, and that in a distinctive way I’ll consider further along.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

How to complicate this basic situation? Armstrong recruits a device—call it a narrative meme if you want—that emerges at the period: the eyewitness, typically in an urban setting, who glimpses possibly criminal doings and gets involved. This device finds its supreme filmic expression in Rear Window (1954), but it’s established in earlier films like Lady on a Train (1945), Shock (1946), and The Window (1949), and in the radio drama The Thing in the Window (1945), by Lucille Fletcher (another thriller queen, but of the airwaves). In Mischief, people in a building across the street from the hotel intervene in the doings of the babysitter, and the plot “intercuts” all their trajectories in order to create tension.

Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold similarly jumps from character to character, even within a single scene. This tale of a heist that is way above the skill sets of the thieves—a sort of humorless anticipation of an Elmore Leonard or Donald Westlake situation—uses unrestricted narration to build sympathy for the characters who are gulled into participating.

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Skip listened, at first with indifference. He’d heard already from Eddie of Karen’s reaction to the money, her frightened excitement about it. It took a moment to realize that this wasn’t more of the same, the reaction of an inexperienced girl, but that a bad break had really occurred.

Throughout the chapter, this rather nineteenth-century version of omniscience will toggle between Karen and Skip, heightening the disparity between her lack of awareness and his harshness. “He was just having fun though she didn’t know it.” Arguably, a heist plot needs a certain wide-ranging narration (see The Asphalt Jungle), but Hitchens uses it to take us into the minds of all the characters, major and minor, and suggest both vulnerability and menace.

In a classic detective story, the identity of the culprit is concealed until the end. One Golden Age “rule” is that in the course of the action we must never be given the viewpoint of the killer. The rule was broken on occasion, notably in a certain novel by Agatha Christie, but it remained rather firm. In the thriller, by contrast, we can be in the killer’s mind, knowing full well that he or she is indeed the killer. A prototype is Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square (1941). Two books in this collection walk a line between detective story and thriller in this respect.

In Eustis’ The Horizontal Man, a popular professor has been murdered. The effects of his death ripple out across the campus, and the narration shifts among his colleagues, some students, and a reporter investigating the crime. In the midst of a corrosive satire of the academic life, we suspect that someone whose mind we have entered will turn out to be the culprit. So we have to probe the inner lives of the characters we encounter for psychological clues, not physical ones. The author must conceal the killer’s identity and “play fair,” in that what we learn at the end unexpectedly fits the characters’ stream-of-consciousness musings.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

It is a pity that this edition didn’t include Millar’s 1983 Introduction and Afterward. The latter explains the origin of the book’s device, while the Introduction reports the effects the book had:

I was threatened with a libel suit, informed by a patient in a mental institution that at last she had found someone who really understood her, invited to join a coven of witches, asked to address a meeting of psychiatric social workers, and presented with the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe award for best mystery of the year.

At the other extreme, two of these novels focus on extremely restricted viewpoints. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place is wholly locked within the mind of a hypermasculine ex-Air Force pilot who trails and murders women. Hughes gives us the pronominal tease: it’s he for the first five pages until, when he places a phone call, we learn he’s called Dix Steele. In a cat-and-mouse game reminiscent of films like Woman in the Window and Where the Sidewalk Ends, the killer gets close to the murder investigation. Dix’s army buddy is the chief cop on the case, so Dix can monitor things and even drop in on crime scenes. Strikingly, Hughes puts the killings “off-page.” This admirably eliminates any Spillane-ish sensationalism while keeping the focus wholly on the way Dix loses control of his masquerade. He’s worn away in a series of confrontations with two women who see, as no man can, something deeply wrong in him.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

As you’d expect, Highsmith tries something more intricate in The Blunderer. Here we have two protagonists, each man given his own viewpoint. But after an opening introducing us to one man’s crime (in a scene that spares no violent detail), he drops out of the action for a hundred pages. We concentrate instead on the polished professional lawyer whose life unravels when his domestic skirmishes—nearly all petty and drab—come to a head. As with most Highsmith men, he is tempted to do something very trivial and very stupid, almost out of intellectual curiosity. Highsmith policemen take a dim view of such enacted thought experiments.

As the two protagonists’ worlds converge, we get the characteristic Highsmith themes of self-possessed men losing their nerve, the traps of respectable life, the risk of impulsive action, the ways in which friends turn away from you when they suspect you of lying. The lawyer is called by his first name, Walter, while his counterpart is known to us by his last name, Kimmel. In such subtle ways does an author align us a little more closely with one character than another. Both, though, are blunderers.

I should add that all the markers of 1940s fiction and film—dreams, hallucinations, false fronts, unstable families, untrustworthy lovers, socially adroit psychopaths—are woven into these novels with great skill. What more could you ask?

A frenzy of recapitulation

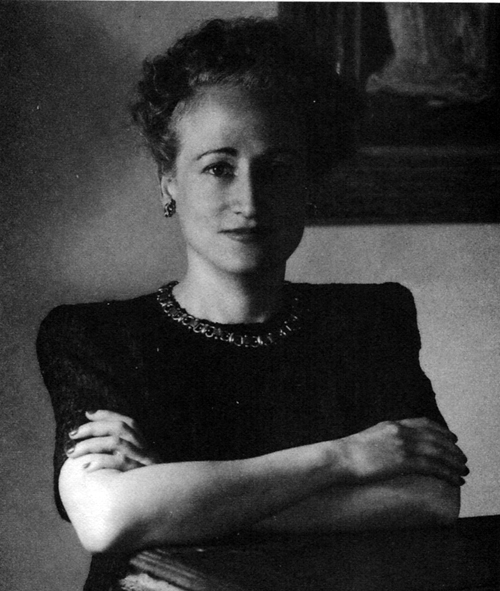

Vera Caspary, 1946.

The earliest novel in Weinman’s collection is also one of the most remarkable of the period. Vera Caspary was a woman to be reckoned with—Greenwich Village free-love practitioner, Communist party member, occasional screenwriter, boundlessly energetic purveyor of suspense fiction, passionate paramour of a married man, and advocate for women in prison. Our State Historical Society holds her personal collection, which includes fascinating notes on projects both realized and unrealized. Turning the pages of her files, you meet a crisp, professional artisan.

So let’s look at Laura the novel. If you know the film, as you probably do, nothing I say will spoil the book for you.

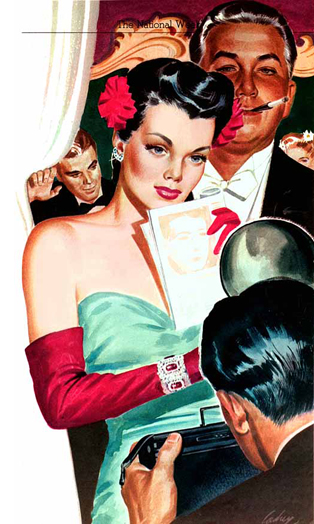

In 1942 Collier’s (“The National Weekly”) offered Caspary $10,000 for the serial rights to Ring Twice for Laura. That sum, equal to $150,000 today, didn’t include book publishing rights, movie rights, and any other ancillaries. The price tag tells us quite a bit about the robust slick-magazine market of the period and about Vera Caspary’s standing. After writing novels, plays, short stories, and screenplays, she was no novice, but her new manuscript set her on a path toward fame. Published as Laura in 1943, it found acclaim as “something quite different from the run-of-the-mill detective story.” The publisher called it a “psychothriller.”

Laura is both a mystery story and a romance. A woman is found murdered in her apartment. Although a shotgun blast has disfigured her face, she’s initially identified as ad executive Laura Hunt. After the funeral, while detective Lieutenant Mark McPherson is poking around her apartment, Laura returns from a trip and it’s revealed that the victim was actually Diane Redfern, a model to whom Laura had loaned the apartment.

The misidentified-victim convention triggers an investigation into the usual sort of suppressed backstory: How did Diane wind up in Laura’s place? Was she alone? Was she the target all along, or was she mistaken by the killer for Laura? Along the way, the cop—already half in love with Laura dead—begins to both woo and browbeat her.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

What was striking about the book was its point-of-view structure. “Four persons tell this story and play the leading parts in it,” noted the New York Times reviewer. “McPherson questions all three, and all three tell him lies.” In presentation Caspary revived what has been called the casebook method of composition: a series of testimonies, written or transcribed from speech, that recount the mystery. Sometimes those are accompanied by police reports, newspaper coverage, and other documents.

The method is identified with Wilkie Collins’ two great novels The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868), and was taken up occasionally by others, particularly within a trial situation (e.g., The Bellamy Trial, 1929). Before Laura, probably the most famous instance of a mystery collation is Dorothy Sayers and Robert Eustace’s Documents in the Case (1930). The technique also has affinities with multiple-viewpoint assembly in “straight” fiction influenced by Dos Passos; Kenneth Fearing had tried it in his experimental novels The Hospital (1939) and Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) as well as in his crime stories Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946).

To take us through the eight days of the investigation, Caspary’s casebook assigns each character a block of narration. Each block, told in first person, has its own distinctive tenor, representing a particular subgenre of mystery fiction.

If you didn’t know the Laura mystique already, you might suspect that the opening chunk, told from Waldo’s perspective, would announce him as the brilliant amateur detective who will solve the case and surpass the plodding McPherson. Waldo is a celebrity columnist, a connoisseur of murder and lethal banter. Like 1920s detective Philo Vance, he collects art and lords it over others through aggressive erudition. Waldo writes in periodic sentences of eloquent self-congratulation:

My grief in her sudden and violent death found consolation in the thought that my friend, had she lived to a ripe old age, would have passed into oblivion, whereas the violence of her passing and the genius of her admirer gave her a fair chance at immortality.

There are even the sort of fake footnotes that we find in S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen novels of the 1930s, attesting to the scholarly bona fides of this dilettante sleuth.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

That is my omniscient role. As narrator and interpreter, I shall describe scenes which I never saw and record dialogues which I did not hear. For this impudence I offer no excuse. I am an artist, and it is my business to re-create movement precisely as I create mood. I know these people, their voices ring in my ears, and I need only close my eyes and see characteristic gestures. My written dialogue will have more clarity, compactness, and essence of character than their spoken lines, for I am able to edit while I write, whereas they carried on their conversation in a loose and pointless fashion with no sense of form or crisis in the building of their scenes.

This is an extraordinary passage. It opens the very-‘40s possibility that what follows may be Waldo’s fantasy. Only near the end of his text does Waldo assert that his knowledge of McPherson’s investigation is derived from what Mark later told him one night at dinner. We will soon learn that Waldo’s opening section was written directly after that dinner, but he actually didn’t know one key fact. His omniscience is an illusion.

McPherson takes up the tale in the second part. He has read Waldo’s account and treats it as a separate piece of evidence. As we follow McPherson’s investigation, we’re in the realm of the police procedural. The register shifts too. If Waldo’s style is showoffish, McPherson’s is laconic. Whereas Waldo celebrates how his prose will immortalize Laura, McPherson admits that his version of things “won’t have the smooth professional touch.”

Actually, though, it does. It reads hard-boiled.

As we stepped out of the restaurant, the heat hit us like a blast from a furnace. The air was dead. Not a shirt-tail moved on the washlines of McDougal Street. The town smelled like rotten eggs. A thunderstorm was rolling in.

Caspary gives us the voice of the tough but vulnerable cop, the voice we would later learn to call noir. There’s an echo of James M. Cain when McPherson signals that in retrospect he was wrong to trust this femme fatale: he sourly describes himself in the third person.

She offered her hand.

The sucker took it and believed her.

McPherson’s eventual victory over Waldo is prefigured in the cop’s reflections on writing up crime. When Waldo learned Laura was still alive, McPherson says, “The prose style was knocked right out of him.” So much for Wimseyish fops set down in a Manhattan murder.

Shelby gets his voice in as well. A brief third section consists of a police transcript of McPherson’s questioning. Aided by his attorney, Shelby withdraws some lies, dodges uncomfortable areas, and generally remains the most obvious suspect—as well as Mark’s rival for Laura. At this point in the book Caspary begins to play an intricate game of knowledge, in which we get, piecemeal, information that tests the string of deceptions and evasions confronting McPherson.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

It’s always when I start on a long journey or meet an exciting man or take a new job that I must sit for hours in a frenzy of recapitulation.

Now the action is that of the woman in peril, the figure familiar from Eberhart and Rinehart and Sanxay Holding. And so the stylistic register is “feminine,” tracking fluctuations of feeling and noting costume details and shades of color. Laura’s narration is also suspenseful and contemplative, dwelling on moments that seem to radiate danger—McPherson’s trick questions, Waldo’s sinister manipulations, and Shelby’s pretense that he’s protecting her rather than himself.

The emphasis is less on external behavior than Laura’s growing realization of why she has clung to two failed men. She will gradually realize that McPherson, despite his coldness, is the best match for her. Waldo is “an old lady” and Shelby is an overgrown baby. Caspary the left-winger gives these portraits the taint of class corruption. Waldo and Shelby are ghoulish creatures of the high life, while Aunt Susie is the faded, self-indulgent beauty Laura might become.

Laura’s recognition of her entrapment is rendered in a choppy, spasmodic fashion. Waldo’s, McPherson’s, and Shelby’s accounts have all been linear. Laura’s is not. It skips around in time, replays scenes we’ve seen from other viewpoints, and incorporates dreams that seem as well to be flashbacks.

This is no way to write the story. I should be simple and coherent, fact after fact, giving order to the chaos of my mind. . . . But tonight writing thickens the dust. Now that Shelby has turned against me and Mark shown the nature of his trickery, I am afraid of facts in orderly sequence.

In a narrative dynamic we find throughout 1940s fiction and film, the strong career woman is thrown off balance and succumbs to confusion. The most notorious example is of course Lady in the Dark, the 1941 play that appeared on film in 1944, the same year as the film version of Laura.

The lady returned from the dead will need a real man to rescue her. That rescue is enacted, again, in prose when McPherson reassumes control of the narrative. The book’s fifth part consists of two sections: the classic summing up and denunciation of the culprit (Waldo) and the rescue of Laura from Waldo’s second attempt to kill her. McPherson’s hard-boiled diction has won out. As Waldo is taken away in the ambulance, however, he earns a degree of purely verbal revenge. McPherson’s narration quotes Waldo’s mumbled phrases as, dying, he fills in plot points. In the process, his style gets inserted, like an alien bacterium, into McPherson’s curt passages.

McPherson, who can afford to be gallant, gives Waldo the last convoluted word. It comes in a quotation from the manuscript found by McPherson at the climax, a passage that confirmed Waldo’s guilt. In Waldo’s unfinished account, Laura is an essence of womanhood, a modern Eve; but one who continually reminded him that he could never be Adam.

During production of the film version of Laura, the makers considered mimicking the novel’s block construction. Citizen Kane had made multiple-viewpoint narration more thinkable in the 1940s. In the end, though, only Waldo’s voice-over was retained, with results that have provoked several critical comments.

The film made many other changes, large and small, but during this reading of the novel two improvements stood out for me. Making Waldo a radio commentator as well as a columnist allows a rich play of sound that comes to a climax at the film’s dénouement. Secondly, Waldo drops out of the book for many stretches, largely because Caspary is concerned to throw suspicion on Shelby and Laura. But the film keeps Waldo onscreen a lot, even permitting him (against all plausibility) to tag along with McPherson on the investigation. His waspish interjections, delivered by a suave Clifton Webb, add a nice tang, while sustaining Caspary’s theme of class snobbery. The film adds several kinks, such as introducing Waldo writing in his bathtub. The situation includes one of those how-did-they-get-away-with-it? moments when, as Waldo climbs out of the water, Mark glances scornfully offscreen at Waldo’s privates.

Caspary would go on to other successes, notably the screenplays for A Letter to Three Wives (1948) and Les Girls (1957) and several other novels that play with block construction and shifting viewpoints. But Laura would remain her prime achievement. It’s a striking novel that became a landmark film and an enduring example of how female crime novelists could stretch and deepen the conventions of popular literature.

A useful and spoiler-free biographical survey of many of these writers is Jeffrey Marks’ Atomic Renaissance: Women Mystery Writers of the 1940s and 1950s (Delphi, 2003). See Mike Grost’s inevitably encyclopedic coverage as well.

Highsmith’s disdain for pulpish style is discussed in Andrew Wilson, Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith (Bloomsbury, 2003), p. 124; my quotation above comes from p. 256. I’m grateful to Ms. Stéphanie Cudré-Mauroux of the Archives littéraires suisses for other information about Highsmith.

Some craft advice from these authors can be found in Dorothy B. Hughes, “The Challenge of Mystery Fiction,” The Writer 60, 5 (May 1947), 177-179; Charlotte Armstrong, “Razzle Dazzle,” The Writer 66, 1 (January 1953), 3-5; and Patricia Highsmith, “Suspense in Fiction,” The Writer 67, 12 (December 1954), 403-406. Millar’s discussion of Beast in View is in the International Polygonics edition of the novel, 1983, pp. 1-2, 249.

Vera Caspary’s autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979), is a captivating read that introduces us to a fascinating personality. (“Under the ready smiles were witches’ grimaces, beneath the padded bra a calcified heart.”) In Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011) A. B. Emrys offers an excellent study of Caspary’s work in relation to mystery traditions. Caspary’s “official” response to Preminger’s film comes in “My Laura and Otto’s,” Saturday Review (26 June 1971), 36-37.

Hammett was no slouch at juggling proper names and pronouns either. I marvel that he could call Ned Beaumont “Ned Beaumont” all the way through The Glass Key. All the other characters are tagged with their first or last name, but this option maintains an unsettling middle distance on his psychologically opaque protagonist.

I discuss Waldo’s narration in the film version of Laura in more detail in this entry.

Pesky brats, adventurous ducks, and jiving swamp critters

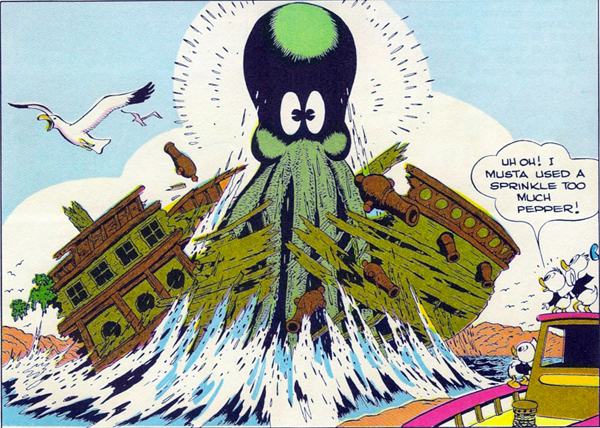

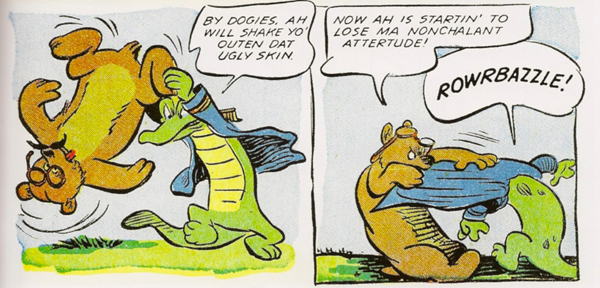

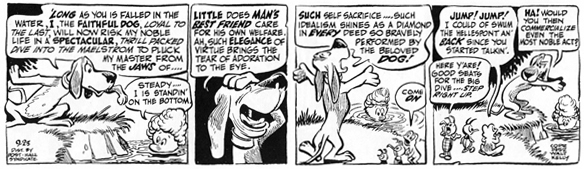

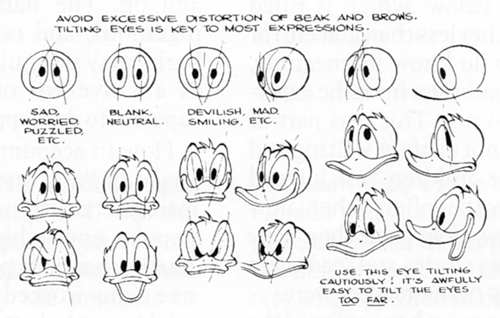

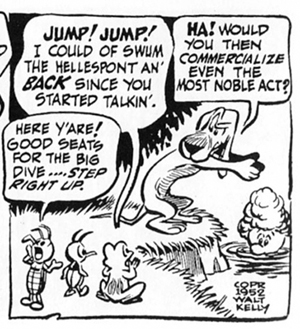

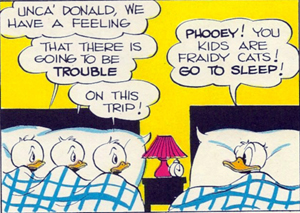

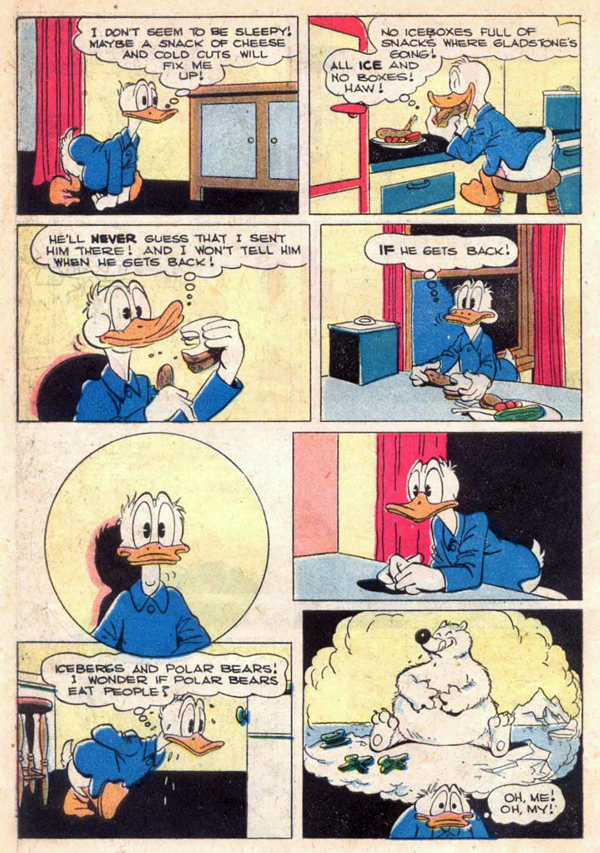

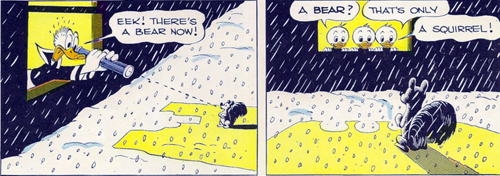

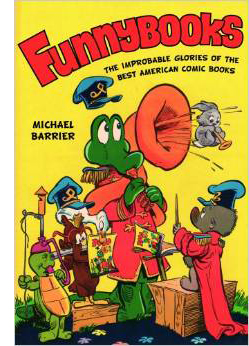

Carl Barks, Ghost of the Grotto (1947).

DB here:

We never need an excuse to write about comic strips or comic books. We’re fans and, just as important, we think of them as having important connections to film. We’re particularly fond of classic funny-animal comics, from Krazy Kat (the greatest) onward. So I got a double dose of pleasure reading Mike Barrier’s Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books. It taught me a lot about the history of some favorites, and it set me thinking about some overlaps and divergences between film and graphic art.

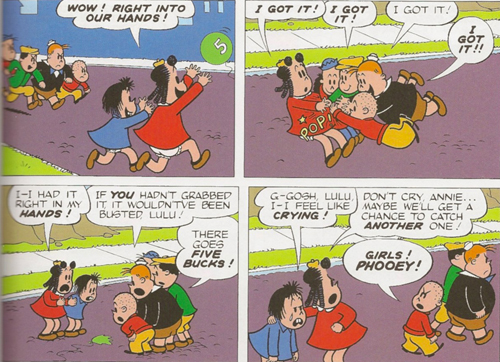

No Girls Allowed

Like Mike’s Disney book The Animated Man, Funnybooks is at one level a scrupulously researched business history. It explains how publisher Western Printing and Lithography (of Racine, WI) became the center of a thriving industry. Before the mid-1930s the company’s juvenile line came out chiefly under the Whitman imprint. Its illustrated storybooks licensed characters from Disney and comic strips like Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie. But Hal Horne and Oskar Lebeck pushed toward creating comic books proper, those inviting items that could compete with the superhero titles that were emerging. Their instincts were sound: Western’s comics, distributed by the Dell company, sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

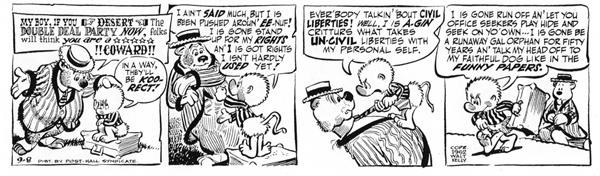

After several tries at compiling daily comic strips into a single volume, Lebeck turned to original content. In the early 1940s he hired Walt Kelly, Carl Barks, and John Stanley. All had worked in film animation (Kelly and Barks for Disney, Stanley for Max Fleischer), but they adjusted to the demands of more static cartoon art. Into the rise and fall of Western and Dell, Barrier weaves the personal stories of the three creators and their less famous peers. Funnybooks is at once industrial history and a collective biography.