Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.

Many films from Hollywood’s studio era are soft, low-contrast, and grainy. Project a 1930s nitrate copy today, and though it will be gorgeous, it’s likely to look surprisingly unsharp. Things apparently didn’t improve when safety stock came along in the late 1940s; projectionists complained that those prints were even softer and harder to focus than nitrate ones. As recently as the 1970s, films were not as crisp as we’d like to think. I’ve examined the first two parts of The Godfather on IB Tech 35mm originals, and though they look sharp on a flatbed viewer, in projection the grains swarm across the screen like beetles. (I should add that many of today’s films also look mushy and grainy in the release prints I see at my local.)

But I think that DVD cultivated a taste for hard-edged images, perhaps in the way that music CDs cultivated a taste for brittle, vacuum-packed sound. It’s not surprising, then, that video aficionados are often startled when a DVD release of a classic movie looks far from clean. This is not always attributable to a film’s not being cleaned up to the fullest extent the technology allows. Some films are inherently grainy, gritty, or soft-looking. With the advent of Blu-ray and HD imagery for the home, those films’ look is often mistaken for problems with the transfer, or signs that the distributor didn’t care enough to spend the money to thoroughly make it new. “New” in this case means contemporary.

So there are compromises, according to Grover, that the studios are having to deal with:

What do do about a film that is really grainy? Do you remove the grain, reduce the grain, leave the grain alone? Everyone seems to have a different answer, and it often puts the distributor in a difficult situation. These are questions that will be answered over time, as the consumer gets used to seeing images in HD that truly represent the way a film looks.

Another compromise involves sound. “Now you’re getting to an ethical area,” Grover remarks. In restoring early sound movies, Sony removes only clicks, pops, and scratchy noises (while still keeping the original, faults and all, as a reference). Sound problems are compounded in films from the early 1950s. Many releases at that time were shot in a widescreen process but retained monaural sound. Yet avid DVD buyers want multitrack versions to feed their home theatres. “If it’s not 5.1, we get complaints.” So Grover’s engineers “upmix” mono, as well as two-channel stereo, to 5.1—though they strive to keep the 5.1 minimal and retain as much authenticity as possible. Not on every film, of course: often the original mono track is included on the DVD.

On the positive side, Sony held the original tracks for Tommy (1975), originally released in Quintaphonic. (Old-timers will remember that audiophiles were urged to upgrade to this, and some LPs were released in that format.) Grover was pleased that he could replicate the theatrical version’s 5-channel mix on the DVD. (More details here.)

Now for a hobby horse of mine. The 1950s-1960s standards for multichannel sound were not those of today’s theatres. Today’s filmmakers funnel important dialogue through the front central speaker. But in multi-track CinemaScope and other widescreen formats, dialogue was spread to the left and right speakers as well, and these were behind the screen. That meant that a character standing on screen left was heard from that spot as well. (Remember, these screens might be seventy feet across.) Long ago Kristin and I saw an original 70mm release print of Exodus (shot in Super Panavision) in a big roadshow house in Paris. The ping-pong effect of the conversations between Ralph Richardson and Eva Marie Saint was fascinating.

Today, however, it might be distracting. In a home theatre, where discrete tracks present sound from offscreen left or right, it would seem downright weird. Although Grover didn’t comment on this, it’s clear that the big-screen classics from the magnetic-track era are remixed for DVD to suit current theatrical and home-video standards. This makes it very difficult for researchers to study the aesthetics of sound design from that period. Even if you visit an archive, that institution almost certainly isn’t able to project the film in a multi-channel version. (5) Is it too late to ask DVD producers to replicate, on a second soundtrack, the original channel layout? This would be a big favor to the academic study of the history of sound, and some home-theatre enthusiasts might develop a taste for the old-fashioned sonic field.

Last questions

Q: Do Grover and his colleagues take notice of online chat about DVD releases?

A: Yes, because it’s important to know what many participants in those conversations want from a film’s release, and they may also know things (from a hardcore fan’s pespective) about a film that is useful to know. Grover’s staff members can learn about missing scenes and other variant prints. But sometimes the Net writers are working from incomplete information and can get things wrong. A fan fervently announced that one word was intelligible in the “original” version of a film but not on the DVD. Yet the theatrical release version muffled the word. It turns out that the word was audible in a remixed TV version, which the fan had used as reference. Likewise, one critic who found the color on the Man for All Seasons Special Edition DVD too vibrant was evidently using a VHS version as the reference point. (For what it’s worth, the color in the Man for All Seasons theatrical release I saw was extremely vivid.) And Grover and his colleagues never intervene in the online debates.

Q: Why do DVDs seem different from projected prints—often much sharper?

A: An original film frame, in camera negative, has more resolution than can be captured in a print. Most prints are a generation or two past the material that a DVD transfer uses, so they gain a certain softness. Granted, however, in making high-definition video masters sometimes the tools to sharpen and de-grain the image are overused.

In addition, it’s generally a good idea to get your home video display calibrated. Most home displays are way too bright, sometimes brighter than a theatre screen. If you darkened the room and had the display dialed down, DVDs would look more film-like.

Q: When will we get the Boetticher westerns?

A: It’s the most frequent question Grover gets asked. Soon, soon: A boxed set of restored titles is on the way.

Q: And what about all the Capra titles?

A: Sony plans to restore each of them. Columbia struck many prints of them, and so there is some negative wear. Some negatives no longer exist. On one title, Say It with Sables (1928), Sony has neither negative nor prints.

There’s a too-good-to-be-true backstory here. Capra had a ranch in Pomona, which upon his death was bequeathed to Pomona State University. After some years, people found in a locked stable his private collection of prints struck in 1939. The cache included Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It with You, It Happened One Night, and the best-quality print of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Grover had yet seen. There were also photographs Capra had shot of premieres and vacations. Thanks to the good offices of Frank Capra, Jr., Sony acquired the prints and used them in its restorations.

As for American Madness, Grover called it a “training film” for later Capra productions. The theme of faith in the little man, manifested in a bank run that tests a humane banker’s alliances in the community, points ahead to It’s a Wonderful Life and other films. Sony holds a complete soundtrack and a nearly complete original negative. UCLA held a complete nitrate print donated by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department; evidently the film was screened in parks as public entertainment. That print wasn’t in good condition, but it allowed Grover’s team to fill out certain scenes. The nitrate print’s footage is noticeably lighter and grainier in a few places. American Madness wasn’t a digital restoration, but if it were done today Grover would probably use CGI to blend in the alien footage.

Talkies, with a vengeance

It was fine to see the film again; its brisk inventiveness held up. The gleaming and geometrical images of the opening, which acquaint us with the daily routine of opening the bank vault, might have come out of Metropolis. One helter-skelter montage sequence, complete with canted framings and chiaroscuro lighting, looks forward to Slavko Vorkapich’s delirious contributions to Mr. Smith and Meet John Doe.

The tactics of depth composition that we find in many 1930s movies reappear here, and the illumination has dashes of noir.

I especially like the dynamic pans that carry Walter Huston and Pat O’Brien in and out of the main office; I suspect that they’re cut together faster and faster as the climax gets near. And the huge set of the bank lobby, publicized at the time as the biggest set yet built on the Columbia lot, remains not only impressive but functional. It establishes a cogent geography to which Capra adheres strictly while filming it from a great variety of angles.

But this is not a treat just for the eyes. American Madness flaunts its mastery of emerging talkie technique. The rising action is accentuated by the steady increase in volume of the growing crowd in the bank lobby. The clerks’ scattershot morning chat in the vault is captured in microphone distances and auditory textures that suggest a hollow, sealed-off space. Hawks’ rapid-fire patter in Twentieth Century (1934) has an antecedent here, and at the same studio. The actors speak at a terrific clip, scarcely pausing between lines, and sometimes the dialogue overlaps. We even get competing lines, two or more speeches rattled off at once. (And did Hawks get the idea for His Girl Friday’s variants on telephone chatter from O’Brien working the receivers at the climax?)

In films like this, American movies talk American. Consequently, I’m inclined to regard as an in-joke the glimpse we get of a marquee that’s advertising another Columbia picture: Hollywood Speaks.

Thanks to Grover and Sony Pictures Entertainment for a wonderful series and an enlightening brace of talks. American Madness is available on the DVD set The Premiere Frank Capra Collection.

(1) Chris Horak has been head archivist at George Eastman House, the Munich Film Museum, Universal, and the Hollywood Museum; he’s now Director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Mike Pogorzelski is Director of the Film Archive for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Joe Lindner is Preservation Officer there. (Both are former Badgers.) Schawn Belston is Vice President of Asset Management and Film Preservation at Twentieth Century Fox. Paolo Cherchi Usai is Director of ScreenSound Australia, the national archive, and director of the recent film Passio. Kristin interviewed Mike and Schawn for this blog entry.

(2) YCM separation masters are made by copying a color film onto three black-and-white films. Thanks to filtering, these preserve color luminance at the different values of yellow, cyan, and magenta. Since these monochrome versions are not as susceptible to fading, they can be used for archival preservation. Combined, they can recreate the original color image.

(3) This confirms my impression when I’ve seen different Technicolor prints of the same title. You sometimes get this effect with a composite print, in which the color values change from reel to reel. Anecdotally, I’ve heard that Technicolor staff in the studio days would sort reels according to their dominant color (“That’s the yellow pile over there”).

(4) See Chapter 7 of Silent Cinema: An Introduction (London: British Film Institute, 2000). This book, incidentally, is a good introduction to the sheer fun of archive work. Others communicating the same enthusiasm are Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) and Dan Nissen et al., eds., Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002).

(5) This problem renders the activities of Britain’s National Media Museum in Bradford all the more important. There you can see classic films in a great many formats and sound arrays.

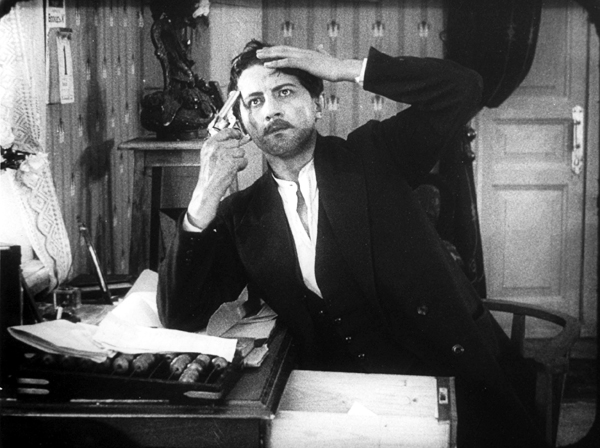

American Madness.

15 June: Thanks to Kent Jones for correcting a name slip.

19 June: Breaking News: Grover has just been promoted to Senior Vice President for asset management, film restoration, and digital mastering. Nice timing; wish we could say our blog put him over the top, butVariety explains that it was good old-fashioned talent. Congratulations to Grover!

Watching movies very, very slowly

Children of the Age (1915).

DB here:

Before DVD and consumer videotape, how could you study films closely? If you had money, you could buy 8mm or 16mm prints of the few titles available in those formats. If you belonged to a library or ran a film club, you could book 16mm prints and screen them over and over. Or you could ask to view the films at a film archive.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

At first archives found it easier to screen films for researchers in projection rooms, but eventually many let visitors watch the films on stand-alone viewers. That way the researcher could stop, go forward and back, and take notes. In researching my dissertation in the summer of 1973, I watched films at George Eastman House in 16mm projection, but a few weeks later in Paris, Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Francaise allowed me time on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse (a term I’ve admired ever since).

Over the years Kristin and I have visited archives in various countries. We’ve become particularly close to the Royal Film Archive of Brussels, partly because back in the 1980s the head, Jacques Ledoux, believed that Kristin’s research was worthwhile and allowed us to visit regularly. Without the cooperation of Ledoux and his successor Gabrielle Claes, we couldn’t have done a great deal of our research. No wonder it helped us so much: the Belgian Cinémathèque is arguably the most diverse archive in the world.

Case in point: My current visit. I came with two goals. First, I had to prepare for my lectures in Bruges later in the month. These consist of eight talks on anamorphic widescreen. So I planned to watch four early CinemaScope films, plus Oshima’s The Catch (1961) and the SuperScope version of While the City Sleeps.

I also wanted to fill in a big gap in my knowledge about a major silent filmmaker. More on him shortly.

Viewing on a visionneuse

If you’ve never watched a film on a viewer, let me explain. The classic viewer is a flatbed, or viewing table. It’s the size of an executive desk. Two platters or spindles hold a feed reel and a take-up reel. Motors drive the film through a series of sprocketed gates, past a projection device (usually a prism) and across a sound head. The film appears on a smallish screen. There’s usually a little surface space to set a notepad, along with a lamp on an articulated arm.

Before digital editing came along, such machines offered the only way filmmakers could cut sound and picture. (Now most phases of editing are done on computer, with physical editing reserved for late stages of postproduction.) Eventually flatbeds were offered in simpler versions for playback rather than editing.

The most common American-made viewer was the Moviola, which was initially not a flatbed but an upright machine. Eventually the German Steenbeck and KEM became the high-end standards for editing picture and sound. The Brussels archive relies on the Prévost, an Italian machine that is very easy to maintain. The Prévost, seen above, beams the image from the prism onto a mirror hanging over the machine, which bounces the picture onto the screen.

35mm films are mounted on 1000- or 2000-foot reels, the latter yielding about twenty minutes of film at sound speed. A feature film will consist of four or more 2000-foot reels. Even if you watch a film straight through, without stopping to make notes, it takes time to change the reels, so a two-hour movie will probably consume nearly three hours on a 35mm flatbed. And of course researchers stop a lot to take notes and move to and fro across a scene. If I’m studying a film intensively, I probably consume about an hour per 2000-foot reel. Across my life, I wouldn’t dare calculate how many months I’ve spent in visionneuse viewing.

Viewing on an individual viewer has both costs and benefits. Sometimes details you’d notice on the big screen are hard to spot on a flatbed. But with your nose fairly close to the film, you can make discoveries you might miss in projection. (Ideally, you would see the film you’re studying on both the big screen and the small one.) In addition, of course, you can stop, go back, and replay stretches. Above all, you get to touch the film. This is a wonderful experience, handling 35mm film. Hold it up to the light and you see the pictures. You can’t do that with videotape or DVD.

The scary part of any flatbed viewing, at least for me, is watching the film whiz along under your nose at ninety feet per minute. If you haven’t threaded the thing properly, or if the print has a weak splice or torn sprocket hole, you can rip the film. For this reason, archives typically don’t allow a researcher to handle films they hold in only one copy.

The average film you watch on a flatbed has an optical soundtrack, that squiggly line that is read by an optical valve. But early CinemaScope films had magnetic tracks so that they could provide stereophonic sound. In the picture below you can see that strips of magnetic tape, like those in tape cassette players, run along both edges of the film strip. For my Scope films, I was obliged to use a Prévost that could handle mag sound–and of course one that could be fitted with an anamorphic lens to unsqueeze the image to the proper proportions.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1954) was a color movie, but this print, like many from the period, has faded to bright pink. The Eastman color stock of the period was unstable, and many prints were processed carelessly. (In unsqueezing the frame, I’ve eliminated the color cast for better clarity.) Restoring color to films of this period is one of the major tasks facing film archivists. Cinema is a fragile art form.

Hours and hours of Bauers and Bauers

At the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in 1989, Yuri Tsivian’s retrospective on Russian Tsarist cinema convinced a lot of us that good filmmaking in that country didn’t start with the Bolshevik revolution. Along with that retrospective came a wonderful book, Silent Witnesses, edited by Yuri and Paolo Cherchi Usai. Unfortunately hard to find now, it’s filled with information about pre-Soviet filmmaking.

Although I enjoyed the Tsarist films, I didn’t know exactly what to watch for. It took me some years to appreciate their artistry, and some of my ideas about them showed up in On the History of Film Style (1997) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). In those places I studied 1910s “tableau” staging and used some examples from Yevgenii Bauer, by common consent the most pictorially ambitious Russian director of the period. Kristin and I also used Bauer as an example of tightly choreographed mise-en-scene in Film Art (p. 143). I thought it was time I examined his work more systematically, and I knew that the Royal Film Archive held some Bauer prints, which they acquired from Gosfilmofond of Moscow.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Although he made comedies, Bauer is most famous for his somber psychological melodramas, often centering on class exploitation. A woman becomes a rich man’s mistress; when she abandons her husband and takes their baby, he commits suicide (Children of the Age). A serving maid is seduced by her master and callously tossed aside when he marries a flirt (Silent Witnesses). Things can get pretty dark. This is the director who made films entitled After Death (1915) and Happiness of Eternal Night (1915). In Daydreams (1915), a widower sees a woman who strikingly resembles his dead wife. Like Scottie in Vertigo, he follows her and becomes increasingly obsessed. Did I mention that he keeps a ropy braid of his dead wife’s hair in a glass box?

Seeing several films again confirmed my view that Bauer knew better than most directors how to organize a shot. His contemporary Louis Feuillade favored a quiet, sober virtuosity, but Bauer developed a flashy visual style. He’s most known for his ambitious use of light (Frigid Souls, below) and big, textured sets packed with columns, trellises, drapes, brocades, embroidered pillowcases, and other elements that add abstract patterns to a scene (Children of the Age, below).

Even a hammock can be stretched and framed to create a swooping web around the innocent heroine of Children of the Age, ensnared by the demimondaine.

In particular, I admire Bauer’s constant inventiveness in moving his actors around the set in smooth ways that always direct our attention to what’s happening at the right moment. European directors of this period seldom cut up a scene into several shots of individual actors; the frame typically shows us the entire playing space. Directors were obliged to shift their actors across the frame and arrange them in depth, like chesspieces.

This master-shot, single setup approach might seem hoplelessly restrictive. Today we expect films to have lots of cutting and camera movement. How does the filmmaker sculpt the action, moment by moment within a static frame?

Blocking, as in blocking the view

I trace some principles of this approach in the books I already mentioned. I’ll mention two strategies here, and if you want to know more you can follow up in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light.

Filmmakers of the 1910s created intricate choreography by moving actors left or right, up to or away from the camera. Often they set up unbalanced compositions and then rebalanced them, creating a kind of spatial tension that parallels the drama. In the course of the action, actors close to the camera might conceal those that are farther away. The blocking of the actors, in other words, also sometimes blocks our view.

In Leon Drey (1915), Bauer tells the story of a cynical womanizer. In one scene, he’s dallying with his latest conquest when another of his lovers bursts into his apartment. The first phase of the shot is very unbalanced; most directors would have put the mistress at the door on one side of the frame and Leon and the woman in his arms at the opposite side. Immediately, though, the woman flees to the bed in the back of the shot and activates the right area of the frame.

As the mistress rushes to the woman in the rear, Leon strides to the foreground and his burly body blots out the drama between the two women. We’re forced to concentrate on his cold indifference to both of his lovers. Eventually his mistress comes to the foreground to remonstrate with him. Now, at the high point of the scene, we have a balanced frame. Note that Leon continues to conceal the first woman; the scene’s not yet about her.

The mistress leaves, angry and desperate, and Leon placidly pays her no mind. As the door closes, he hurries to lock it and summons the first woman, now visible, back from his bed. He will have little trouble convincing her to return to his arms.

The dramatic curve of the scene has been expressed in compositional asymmetry and symmetry, concealing space and then opening it up.

Most directors of the period used principles like these to turn dramatic conflict into vivid choreography. Bauer also tried more unusual tactics. He was especially good at shifting actors’ heads very slightly to open or close off channels of action behind them. Here’s an instance from Her Heroic Feat (1914).

The butler informs Lina and her mother that the scandalous ballerina Klorinda is calling on them. At first Lina’s head is solidly blocking the doorway in the rear. As the butler goes to the rear door, Lina pivots a little to clear our view of that doorway.

Klorinda sashays in, and who could miss it? She’s wearing a bright dress, she’s centrally positioned, and she’s moving toward us. The other women refuse to look at her, but their immobility assures that we keep our eye on Klorinda. When she stops to greet them, then they move, pivoting away; Lina’s head goes back to blocking the doorway. Imagine how things would have gone if her head had been there when Klorinda appeared in the background.

Of course, we should also study the performance techniques of Bauer’s actors–a subject examined in a fine book by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema. The compositional tactics employed here work to draw our attention to the actors’ expressions and body language.

Still, not everything in 1910s ensemble staging owes a debt to the theatre. The changes in Lina’s head position, or Leon Brey’s calculated blockage of the women behind him, wouldn’t work on the stage; most of the audience wouldn’t see the exact alignment we get onscreen. Live theatre depends on varying sightlines, but in cinema, we all see the action from one position, that of the camera. Bauer, Feuillade, and their contemporaries realized that they could organize the action, down to the smallest detail, around what the camera could and could not take in.

The fluent choreography developed by 1910s directors is almost unnoticeable when you’re watching in real time. You’re supposed to register the what–the point of interest in the frame–rather than the how, the slight shifting of actors that highlights this face, then that gesture. By the time you realize that something has happened, the first stages of the process have slipped away, inaccessible to memory.

So there’s a need for slow viewing. Filmmakers have thousands of secrets, many that they don’t know they know. Sometimes we have to stop the movie, go back, and trace precisely how directors achieve their effects. Really slow viewing can help us discover how deep film artistry can be. All hail the visionneuse and the archives that allow scholars to use her.

For background on Bauer, see William M. Drew’s excellent career survey. I discuss Bauer’s relation to narrative painting in another blog entry.

In production and distribution of the period, the titles and inserts (close-ups of newspapers or messages) were sometimes stored on separate reels. In many cases, only the image reels have survived.

Several other Bauer films are available on Milestone’s invaluable DVD set Early Russian Cinema.

The Celestial Multiplex

Kristin here—

The Internet is mind-bogglingly huge, and a lot of people seem to think that most of the texts and images and sound-recordings ever created are now available on it—or will be soon. In relation to music downloading, the idea got termed “The Celestial Jukebox,” and a lot of people believe in it. University libraries are noticeably emptier than they were in my graduate-school days, since students assume they can find all the research materials they need by Googling comfortably in their own rooms.

A lot depends what you’re working on. For The Frodo Franchise, studying the ongoing Lord of the Rings phenomenon would have been impossible without the Internet. A big portion of its endnotes are citations to URLs. On the other hand, my previous book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, a monograph on the stylistic and technical aspects of Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, has not a single Internet reference. Lubitsch can only be investigated in archives and libraries, where one finds the films and the old books and periodicals vital to such a project.

Vast though it is, the Internet is tiny in comparison with the real world. Only a minuscule fraction of all the books, paintings, music, photographs, etc. is online. Belief in a Celestial Jukebox usually works only because people tend to think about the types of texts and images and sounds that they know about and want access to. Yes, more is being put into digital form at a great rate, but more new stuff is being made and old stuff being discovered. There will never come a time when everything is available.

Even so, every now and then someone proclaims that in the not too distant future all the movies ever made will be downloadable for a small fee, a sort of Celestial Multiplex. A. O. Scott declared this in “The Shape of Cinema, Transformed at the Click of a Mouse” (New York Times, March 18): “It is now possible to imagine—to expect—that before too long the entire surviving history of movies will be open for browsing and sampling at the click of a mouse for a few PayPal dollars.”

Not only that, but Scott goes on, “This aspect of the online viewing experience is not, in itself, especially revolutionary.” He’s more interested in the idea that online distribution will allow filmmakers to sell their creations directly to viewers. That would be significant, no doubt, but as a film historian, I’m still gaping at that line about “the entire surviving history of movies.” Such availability would not only be “revolutionary,” it would be downright miraculous. It’s impossible. It just isn’t going to happen.

(The image above was generated to publicize the “Search inside the Music” program that is an important part of the Celestial Jukebox. Imagine movie screens with actors’ faces in those little boxes, and you’ve got the Celestial Multiplex.)

I will give Scott credit for specifying “surviving” films. Other pundits tend to say “all films,” ignoring the sad fact that great swathes of our cinematic heritage, especially in hot, humid climates like that of India, have deteriorated and are irretrievably lost.

Dave Kehr has already briefly pointed out some of the problems with Scott’s claims, mainly the overwhelming financial support that would be needed: “Tony Scott’s optimism struck me as, well, a little optimistic.” On the line about “the entire surviving history of movies,” Kehr suggests, “That’s reckoning without the cost of preparing a film for digital distribution — the same mistake made by the author of the recent vogue book ‘The Long Tail’ — which, depending on how much restoration is necessary, can run up to $50,000 a title. None of the studios is likely to pay that much money to put anything other than the most popular titles in their libraries on line.” As Kehr says, the numbers of films awaiting restoration and scanning isn’t in the hundreds, as Scott casually says. No, it’s in the tens of thousands even if we just count features. It’s more like hundreds of thousands or more likely millions if we count all the surviving shorts, instructional films, ads, porn, everything made in every country of the world. To see how elaborate the preservation of even one short medical teaching film can be, go here.

Putting aside the need for restoration, newer films present a daunting prospect. To help put the situation in perspective, let’s glance over the total number of feature films produced worldwide during some representative years from recent decades (culled from Screen Digest‘s “World Film Production/Distribution” reports, which it publishes each June): 1970, 3,512; 1980, 3710; 1990, 4,645; 2000, 3,782; and 2005, 4,603. For me the numbers conjure up the last shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark, only with just stack upon stack, row upon row of film cans.

Scott isn’t the first commentator to prophesy that all films will eventually be on the Internet. It’s an idea that crops up now and then, and it would be useful to look more closely at why it’s a wild exaggeration. It’s not just the money or the huge volume of film involved, though either of those factors would be prohibitive in itself. There are all sorts of other reasons why the advent of practical digital downloading of films will never come close to providing us with the entire history of cinema.

Coincidentally, two experts on this subject, Michael Pogorzelski, Director of the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Schawn Belston, Vice President, Film Preservation and Asset Management for Twentieth Century Fox, visited Madison this past week. Mike got his MA here in the Dept. of Communication Arts and now returns about once a year to show off the latest restored print that he has worked on. Schawn isn’t an alum, but he has also visited often enough that most students probably think he is. The two brought us the superb new print of Leave Her to Heaven that Fox and the Academy have recently collaborated on.

I figured it would be very enlightening to sit down with these two and talk about why the Internet is never going to allow us to watch just anything our hearts desire. They kindly agreed, and with my trusty recorder in tow we went for burgers—and fried cheese curds, a commodity not available in Los Angeles—at the Plaza Tavern. I’m grateful for the fascinating insights they provided into some of the less obvious obstacles to putting films on the Internet en masse.

No Coordinating Body

Before we launch in, though, one point needs to be made: there is no single leader or group or entity out there organizing some giant program to systematically put all surviving movies on the Internet. There isn’t a set of guidelines or principles. There’s no list of all surviving films. How would we even know if the goal of putting them all up had been achieved? When the last archivist to leave turned out the light, locked the door, and went looking for a new line of work?

Most of the physical prints that would be the basis for such transfers are sitting in the libraries of the studios that own them or in the collections of public and private archives (including many individuals). The studios would make films available online for profit. The archives might be non-profit organizations, but they still would need to fund their online projects in some fashion, either by government support, from private grants, or by charging a fee for downloads. Most archives are more concerned about getting the money to conserve or restore aging, unique prints than about making them widely available. Preservation is an urgent matter, and making the resulting copies universally available for public entertainment or education is decidedly a secondary consideration.

Mike works for a non-profit archive, Schawn for a studio, so together they provide a good overview of some key problems facing the creation of an ideal, comprehensive collection of movies for download.

Money

People who claim that all surviving films could simply be put on the Internet don’t go into the technology and expenses of how that could be done.

Of course, Schawn says, studios want to “digitize the library.” That phrase is highly imprecise, however. He specifies, “For the purposes of this idea of media being online, available, downloadable, streamable, whatever, that’s something that we’re dealing with now using existing video masters. So there isn’t an extra cost to quote, unquote digitize. But there is a cost to make the compression master, what we’re calling at Fox a ‘mezzanine file,’ which is basically a 50 megabit file. That’s the highest-quality ‘low’ quality version of the content from which you can derive all of the different flavors of compression for the various websites that have downloadable media.

“There’s a huge problem with this, in that Amazon, iTunes, and Google all have a slightly different technical specification of how they need the files delivered to them. If you don’t have this kind of mezzanine file, you have to make a different compressed version for each one of these, which costs something, certainly. It’s not incredibly expensive, but it’s not free.

“So why? What’s the motivation to us to compress at Fox the entire library? I don’t know. Are we going to sell enough copies of Lucky Nick Cain [a 1951 George Raft film] compressed on iTunes to cover the costs of making the compression? I don’t think so.”

Compatibility and the Onrush of Technology

Schawn’s mention of the variety of files needed by the big download services raises the problem of compatibility. It’s not just a matter of supplying the files and then forgetting about the whole thing, assuming that the film is available to anybody forever. What about new standards and formats?

Shawn: “Just as with consumer video, the standard changes, so what used to be acceptable yesterday isn’t acceptable now in terms of technical quality.” As time passes, plug-ins make access faster and cheaper, and eventually the original files don’t look good enough. He points out that currently iTunes can’t download HD. If it becomes possible later, “If you want to get 24 in HD, what Fox will have to do is go and re-deliver all the files in HD.” And presumably re-deliver again when the next big format revolution occurs.

Mike explains further, “Using the mezzanine file, you would just have to continue to reformat it to whatever the players demand. The lowest of the low quality will keep going up as people have broadband and can handle larger chunks of data faster.”

What about the film you’ve already downloaded? You acquire films using plug-ins, which change. Think how often you’re told that an update is now available. If you go ahead and keep updating, the changes accumulate. Eventually you may not be able to play the download you paid for. Quicktime will have moved way beyond what the technology was when you made your purchase.

Schawn and Mike both point out that at this stage in the history of downloading, the level of quality is still pretty bad in comparison with prints of films in theaters or on DVDs. It would be nice to think that the virtual film archive could provide sounds and images worthy of the movies themselves, but that will take a long, long time–not the “before too long” that Scott envisions.

Copyright

I raised another matter: “But what about copyright? Every time I hear something about restoration or bringing something out on DVD, it’s, ‘Well, there are rights problems.’ And some of those rights problems don’t get resolved. I assume that quite a few films that they blithely believe can be slapped up for downloading can’t be slapped up.”

Schawn: “Sure, and there are often not any kinds of provisions in the contract about Internet distribution—obviously! So you’re right, how do you deal with that?”

He pointed to Viva Zapata as a film that Fox has restored but can’t make available due to rights issues. The potential sales are not thought to warrant paying to resolve those issues. “I’m sure there are lots of titles in everybody’s libraries that you can’t just pop up on the Internet and start selling.”

The copyright barrier is worse for archives, which seldom own the exhibition or distribution rights to the films they protect. Usually—though not invariably–the studios do not object to archives owning and preserving prints. Making money through showing them or selling copies would be quite another matter.

Mike described the online presence of archival prints. “On a much smaller scale, this is being attempted in the archive world already, like on Rick Prelinger’s site [Prelinger Archives] or on the Library of Congress’s site, where they’ve put up dozens of moving-image files. True, it’s not independent cinema and it’s mostly commercials and the paper prints that have recently been restored. On Prelinger’s site it’s all the industrial films that he’s collected over the years. That has seen a good amount of traffic, but it hasn’t created new audiences for these films, I would argue. At least, not on a huge scale.”

Prelinger’s site contains only public-domain items, including the ever-popular Duck and Cover, allowing him to avoid the problem of copyright. Similarly, the Library of Congress gives access primarily to films in the pre-1915 era.

Suppose an archive and a film studio both have good-quality prints of a minor American film made in the 1940s. The archive does not have the legal right to put it online, and if the studio decides that it does not have the financial incentive to do so, that film will not be made available for downloading. A private collector might possibly create a file and make it available, but he or she would risk being threatened by the copyright-holder.

Piracy

We briefly discussed the methods used to prevent pirated copies being made from downloaded films. Like DVDs, downloads can be pirated, with people sending copies to their friends or even offering downloads for a fee in competition with the copyright holder. Copy-protection codes might make it necessary for a purchaser to keep a downloaded copy only on a hard-drive without being able to burn it onto a DVD. Another type of code could erase the file once the film had been viewed once or twice. That’s not exactly conducive to the ideal archive of world cinema, where we would hope to be able to study a film in detail if we so choose.

One might think that piracy protection mainly applies to studios, with their need to make money. Mike points out, though, that the need for such protection “even applies to the archival model, too. For films that you mention that have gone out of copyright, there’s still the same costs associated with putting a silent film that no one owns–digitizing it, creating the compressed master that goes on the Web—and they aren’t the kinds of subjects that people are going to get rich on at all, so there isn’t a lot of piracy. You don’t hear many archivists complaining, ‘Hey, you took my 1911 Lubin film, damn you! You can’t put that on your Website. That belongs on the archive’s Website.’ But that scenario becomes more of a likelihood for more popular titles. The obscure 1911 Lubin film is on one extreme, but Birth of a Nation, a well-known silent film a lot more people would like to see, is on the other. Let’s say the highest-quality copy is on the Museum of Modern Art’s Website and can be easily lifted and posted on your own site. And even if you just say, ‘Oh, I’ll charge 99 cents or I’ll charge 50 cents to stream it,’ it’s still going to be someone taking over something that the archive put all of the high-end effort and money into doing. Frankly, I think unless it’s an archive with a national mandate and a little bit higher budget to digitize and to put the contents of their archives online, there’s not going to be any motivation to make that high-end investment up front.”

Thus an archive may simply not bother to put a film on the internet because it can’t guarantee recouping the costs that would be generated.

Language and Cultural Barriers

Scott’s notion of easy access to all of surviving world cinema implicitly depends on an idea that all these films are either English-language or already subtitled or dubbed for English-speaking users.

That’s not true for a start, so there would remain a great deal of work to translate films that have never been released in English-language markets. That’s another huge, expensive task.

Then there’s the opposite side of that coin. For truly complete access, everyone in the world, whatever language they speak, would be able to download and appreciate every film. Of course, there are billions of people without computers or Internet access, and it looks unlikely that being able to go online will become universal anytime soon. (For figures on numbers of people with internet access, check here; percentages can be calculated by clicking on each country and finding the total population. In Tajikistan, for example, .07% of the population was online in 2005. One has to assume that a lot of connections in some of those countries are dial-up, so downloading films would be virtually impossible. [June 21, 2010: In 2008, Tajikistan’s online population has grown to .08%.])

So let’s just say that for the foreseeable future downloadable films would “only” need to be subtitled in the languages of countries or regions where significant numbers of people subscribe to PayPal.

In our conversation, Schawn pointed out that digital compression files mean that there can be huge numbers of versions, with different soundtracks dubbed in or different subtitles added. Technically it’s possible to do all that translation. Still, “it’s very complicated. So for worldwide distribution of anything, like you’re talking about your silent film. If you’re in Pakistan, do you get the American version of the movie or do you get the version of the movie with the intertitles appropriate to wherever it is that you’re showing it? If so, that quickly compounds the amount of stuff that’s digitized.”

I responded, “Yeah, or a 1930s Japanese film put on the Internet for downloading, subtitled in every language where there are people that can pay for it. The more you think about it, the more absurd it becomes.”

Scott must be implying as well that there is some single “original” version of a film and that that version would be the one available in this ideal collection in cyberspace. Yet any archivist or film historian knows that multiple versions of a given film are typically made, depending partly on the censorship laws of the different countries where it is originally shown. In making downloadable files available, does a studio or archive use only the original version of a film made for its country of origin and thus risk having it include material offensive to viewers in some places where it might be downloaded? Or does a whole slew of different versions, one acceptable in, say, Iran, another inoffensive to the Danes, and still another compatible with Senegalese social mores, get put online? How could one even gather all such versions and digitize them? National film archives tend to have government mandates to concentrate primarily on preserving their own countries’ films. Not every version of every film gets saved.

The Bottom Line

For all the reasons noted here and others as well, film availability for download will follow pretty much the same economic principles that have governed film sales in other media. Mike’s opinion is, “Whether they’re from an archive or a studio, I think things’ll start going online in the same pace that they came onto DVD, in an eight to ten-year cycle. And there still will be large gaps.”

Schawn interjects, “Just as there are on DVD.”

Mike concludes, “There’s stuff that will never go online. Yeah, just as on DVD.”

*

A truly celestial screening: a restored 35mm print of Bertolucci’s 1900 projected free, under the stars in the Piazza Maggiore, Bologna, summer of 2006