Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Retro-mania

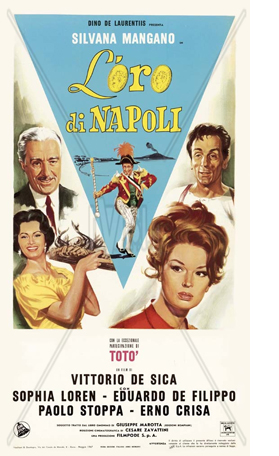

The Gold of Naples (L’oro di Napoli, 1954).

DB here:

With the growing popularity of subscription streaming services, I suspect that film festivals will need to amp up their retrospective offerings. I was very surprised that a good film like I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, which would in earlier years have played arthouses, had no theatrical release. Despite its acclaim at Sundance, it went straight to Netflix online. True, Amazon has shown great willingness to port its high-profile titles to big screens. But by and large, as Netflix, Amazon, and other services produce and buy up new films, I suspect that festival premieres of indie titles will become more and more a display case for streaming. See it this week at our festival, and next month online!

It must be dispiriting for filmmakers hoping for theatrical play. Yet this crunch may oblige festival programmers to emphasize archival and studio restorations. These rarities are unlikely to show up on streaming any time soon, and festival screenings can build a public for them—so that they may eventually come to DVD or subscription services.

Case in point: Several restored titles at our Wisconsin Film Festival drew sellout crowds.

AMPAS comes through

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

I did manage to squeeze into another Academy restoration, Howard Hughes’ Cock of the Air (1932). The film amply showcases Hughes’ two principal concerns, aviation and the female mammary glands. (I guess technically that makes three concerns.) It’s a minor-key Lubitsch switch in which priapic flyboy Chester Morris pursues sexy Billie Dove, who’s resolved to bring his ego crashing to earth. We get lots of nuzzling, murmured double entendres, and scenes of passion quickly doused by the woman’s coquettish withdrawal. I thought the plot thin, needing a romantic rival or two, but the leering pre-Code stuff is good dirty fun. The high point comes when Billie encases herself in a suit of armor and Chester arms himself with a can opener.

The direction is credited to Tom Buckingham, a lower-tier artisan, but it seems possible that parts of the film were handled by Lewis Milestone, who contributed the original story. The first couple of reels are very flashy, with odd angles, complicated tracking shots, and bursts of rhythmic editing. They’re typical of Milestone’s showy, sometimes showoffish, style in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and The Front Page (1931; also shown at WFF).

Cock of the Air encountered heavy censorship, with the can-opener episode entirely snipped from the release version. The Hays Office even provided local censor boards with guidance for further cutting. When Heather discovered a pre-censorship print at the Academy—an exciting find—she discovered that the offending footage was there, but the soundtrack portions were lost.

Heather proceeded to hire actors to voice the parts in accord with the script and the onscreen lip movements. The results are sonically smooth, but in the spirit of fair dealing, the bits of replacement are marked with a discreet bug in the lower right corner of the frame. This is a nice piece of archival integrity. Heather also showed an informative short on the restoration of this engaging piece of naughty early sound cinema.

Of incidents and non-incidents

The Incident (1967).

Two other pieces of film history got fitted into place with the revival of Larry Peerce’s One Potato, Two Potato (1964), a classic of American social-problem cinema, and the rarer The Incident (1967). This latter glimpse of mean streets creates what screenwriter David Koepp calls a Bottle, a tightly constrained space in which the drama plays out. Here the Bottle is a subway car in which several people, a cross-section of New York life, become the playthings of two young thugs, played by Tony Musante and Martin Sheen.

Starting by gay-bashing and culminating in a charged racial confrontation, the subway conflicts sought to show how the solid citizens can’t summon the will to respond collectively—even when they take their turn under the thugs’ lash. It was intended as a response to the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese, whose screams were mostly ignored by her Queens neighbors. (A recent documentary, The Witness, revisits the case.)

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

A believer in improvisation, Peerce rehearsed different groups of actors separately, then brought them together to let some natural friction emerge. He encouraged them to add to the script and build immediate reactions—so immediate that Thelma Ritter, a veteran unused to improv methods, responded to Musante’s goadings by slapping him. All this is captured in a superheated style of fast cuts, big close-ups, and screeching sound. It’s a white-knuckle ride that retains its power. I hadn’t seen it since 1970, but the violent climax, utterly earned, is disturbingly contemporary. The film’s final moments are being replayed, in reality, all over America as you read this.

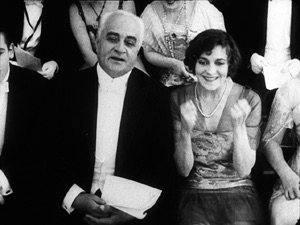

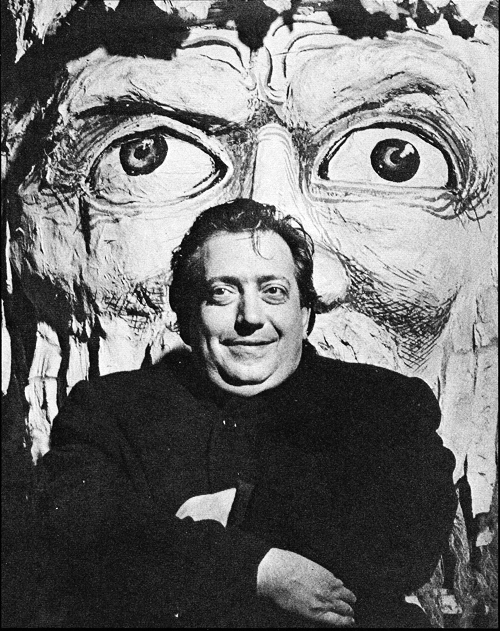

The nicest surprise of my retrospective viewing was The Gold of Naples (1954). Studded with big names (Ponti and De Laurentiis, Totó and de Sica, Silvana Mangano and Sophia Loren), it has sometimes been thought to be one of those lightweight Italian comedies that represent a quiet refusal of the Neorealist impulse. On the contrary, it proves to be a bold contribution to block construction, here in the omnibus genre. Several stories are laid end to end, exemplifying the vivacity and poignancy of life in Naples’ back alleys.

One story has a tight, shocking arc: the tale of a prostitute (Mangano) who thinks she’s marrying for love until she learns her new husband’s guilt-ridden sadomasochistic motives. The finale is a scrappy anecdote, in which The People give a local plutocrat the ultimate vocalization of disrespect.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

Above all, in an episode cut from the original American release (and missing from this poster, though at the top of today’s entry), a mother follows her son’s coffin driven through the street. She throws wrapped candies for children to pick up. That’s it. No flashbacks to life with her boy, no dialogue telling us how he died, no colorful secondary characters to provide that life-goes-on final note. It could be called “The Incident,” though nothing more unlike the fever-pitch drama of Larry Peerce’s film could be imagined.

According to screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, a Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

The lack of a dramatic peak, to which a normal scene would build, can force our attention to downshift to the minutiae of moment-by-moment action, or rather micro-action. That’s what happens in this sequence of The Gold of Naples, which Zavattini helped write. Every gesture and glance becomes potentially, but ambiguously, significant. De Sica’s patient recording of a very thin slice of life is as radiantly unpretentious a model of “pure Neorealism” as anything to come from the 1940s.

This is just a glimpse of the delights among the 150 screenings that are gracing our eight-day film festival. (We’re now the largest university-sponsored festival in the country, though probably not in budget.) Details of this magnificently programmed affair are here. We’ll blog again soon.

Thanks to the programmers Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King, along with all the institutions, wise elders, community supporters, and volunteers that make WFF fun. You can browse earlier reportage from this event here.

You can also see the restored Front Page (1931) in Criterion’s new His Girl Friday DVD release. On Cock of the Air’s censorship travails, see the AFI site. It will be screened very soon at the TCM Festival. Also set for the TCM festival is The Incident, which will screen later in April at Film Forum. Mike Mashon gives more information on Aloha Wanderwell in his LoC blog.

How wrong I was to miss booking The Gold of Naples when I ran a film club in college and good old Audio-Brandon offered it. Even without the funeral scene and the up-yours finale, it would be worth seeing. Now no version seems available in the US; WFF director Jim Healy brought a print from Italy. It would be perfect for FilmStruck.

Read…watch movie…grab food…read…watch movie…

Movies in the mountain, and on the machine

DB here:

I’m back in Madison from 2 1/2 months in Washington, DC. under the auspices of the John M. Kluge Center, where I was this year’s Chair of Modern Culture. This kind appointment allowed me to pursue my research into 1910s American film style, than which nothing could be more fun. Along with that were some extramural activities. The most spectacular one was our Kluge field trip into the most overwhelming media archive in the world–the bulging-biceps caped crusader of film, TV, and sound preservation.

Treasures under Mount Pony

Dr. Strangelove could have come up with the idea. If the Russians attack the US, better have a deep underground vault for storing a few billion dollars to replenish currency supplies on the East Coast. So in the Culpeper, Virginia countryside build a gigantic secret bunker. Include facilities for housing 500 or so personnel to keep the government, or what was left of it, running for a month. Add amenities like a pistol range and refrigeration units to cool cadavers that couldn’t be buried outside. Getting assigned here in nuclear winter would definitely count as subterranean homesick blues.

This super-secret complex was completed in 1969. It boasted foot-thick concrete walls and was surrounded by barbed wire and machine-gun nests. By 1992, the bombs had failed to fall, so the complex was decommissioned and eventually offered for sale. After a major grant to the Library from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, a long-time friend of American film history, the building was transferred to the Packard Humanities Institute . The facility was renovated thanks to over $260 million of Packard and Congressional funding. A lot, yes, but in 2017 dollars that comes to about $402 million, and Beauty and the Beast has scared up about twice that over the last couple weeks.

The renovation turned this vast bank vault/bomb shelter into the world’s most colossal and up-to-date media storage and preservation facility. Opened in 2007, the National Audio-Visual Center is also known as the Packard Campus. Its collection of films, videos, and audio records, along with posters and documents, come to over six million items sitting on ninety miles of shelving. With 80 per cent of it sunk below ground, it was designed to be an exemplary green building, with a vast gardened roof.

Thanks to the energy of Kluge Center director Ted Widmer and his colleagues, we had a chance to visit the place. Greg Lukow, Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus, and Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image section, led us in a labyrinthine, carefully organized three-hour tour of the dazzling facility.

I can’t convey all that we learned about conservation of film, TV, sound recordings, and digital media. Rest assured that the hundred-plus people working away here in state-of-the-art conditions are striving mightily to save media artifacts for you and me and our heirs. Here are some high points.

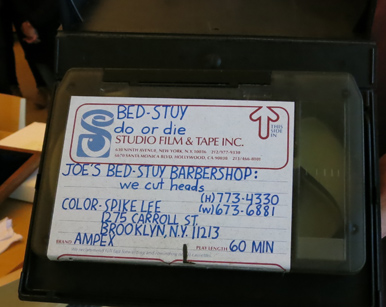

Mike introduced the visitors to the moving-image formats of the media conserved at the facility, everything from film and videotape to Digital Cinema Packages. Spike Lee’s first film, as a copyright deposit, is there too, on Ampex tape.

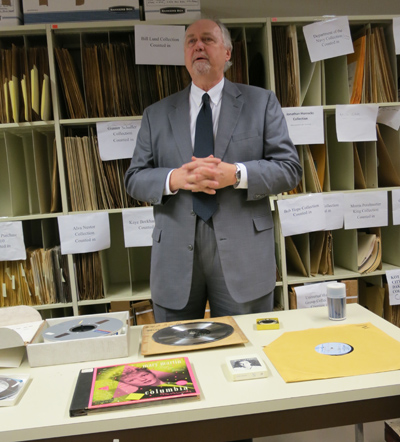

Sound isn’t neglected, as Greg offered a comparable overview of all the audio formats, including cylinder and wire recording. Yes, 8-tracks are also involved. On the right you see the Scully Lathe, a gleaming bad boy that cut disks. Used from the 1930s into the 70s it’s being brought back with the new interest in vinyl records.

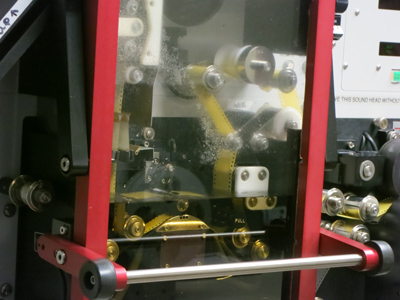

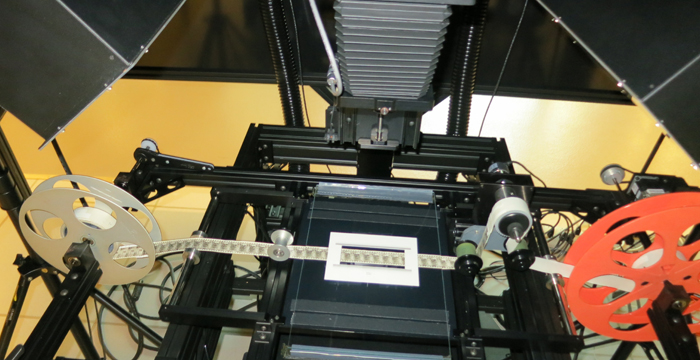

We visited several lab and restoration rooms, including one for wet-gate printing and another for migrating VHS tapes to digital files. Since the latter has to be done in real time, robots are recruited for the job, busily gliding up and down ranks of cassettes.

Of course we had to stop by film vaults, kept a chilly 39 degrees. On the left we see some of the holiest of holies, nitrate vaults. It looks like a Spanish Civil War prison, rows and rows of heavy doors. The vault on the right contains master safety film elements, on both acetate and polyester stock.

What’s a trip to an archive without despoiled artifacts? On the left, a flaking glass-based 16-inch lacquer instantaneous disc from the NBC radio collection. “Instantaneous” means that it was a recording of a live broadcast, and so was probably unique. On the right, we have decomposed nitrate film.

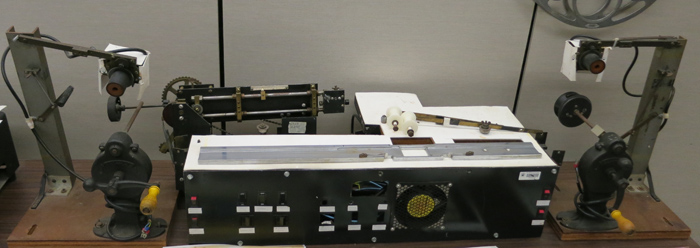

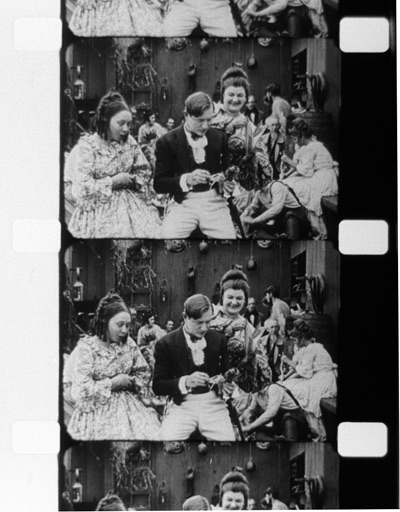

Of enduring interest to cinephiles is the famous paper print collection. Film companies of the earliest years submitted to the Library movies on rolls of paper, to be copyrighted in the manner of still photographs.To be preserved and screened, those had to be turned back into films. During the 1950s that task was fulfilled by Kemp R. Niver in a home-made rig.

He transferred some 3,000 titles to 16mm–not the ideal format, but better than nothing. Some results were fuzzy and jumpy, but many came out okay. I watched several during my stay, including The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914).

Since then, some excellent 35mm prints have been made from the paper prints, and still more success has been found with digital remastering, which can correct for misaligned frames on the original paper copies.

It was good to learn that film copies of new releases are still being submitted for copyright deposit. An impeccable print of Get Out arrived while I was there, and of course 35mm advocate Christopher Nolan wouldn’t miss a chance to save Inception and other of his works.

But I was dismayed to learn that a great many companies, taking advantage of a loose requirement about what counts as a deposit copy, are submitting DVDs, Blu-rays, and even DVD-R versions of their films. If they can’t submit a print, they should at least provide an unencrypted DCP. Otherwise, scholars and audiences of the future will encounter the digital equivalent of the crawling, scraped deterioration we see with film.

101 movies

Fortunately for me, 1910s films are still available on film. Viewing prints of films stored at Culpeper are shipped to the James Madison Building in the District. There, in the Moving Image Research Center, they may be viewed on my old friend, the flatbed machine known as a Steenbeck. Every day a Steenbeck patiently awaited my depredations.

The staff of the Reading Room were just superb in helping me order titles and dig up information about them. Above you see the team I worked with: Dorinda Hartmann, Rosemary Hanes, Josie Walters-Johnston, and Zoran Sinobad.

I learned an enormous amount from them, and I enjoyed talking movies with them during our breaks. Others who helped me greatly were Karen Fishman, Research Center Supervisor, MBRS Division; Alan Gevinson, curator of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting; and David Pierce, Assistant Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus.

My mission was to see as many American fiction features from the 1910s as I could. This was the period when a five-reel film (ca. 60-70 min.) became a dominant format, though shorts and longer films were also being made. I’ve spent about a decade watching largely European films of the period in various archives and in Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, with results I’ve occasionally discussed on this blog. A visit to the LoC nicely complemented my Continental and Nordic explorations. Although several American films from the period are available on DVD, I’ve tried to see even those in film copies. (Why? Tell you later.)

For a time I was joined by James Cutting, perceptual psychologist extraordinaire, who enthusiastically wanted to watch these old movies. His presence helped me a lot, sharpening my attention to things in the images. Here’s James, skewed, during our nighttime trip to Chinatown for food and Get Out.

In all, across 42 business days (had to take days off for holidays and inauguration), I saw 101 films, 98 from my period and three others for other projects.

Not all the films survive complete. Some lacked one or more reels. That’s a great pity in the case of Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s False Colours (1914), Sunshine Molly (1915), and Idle Wives (1916); William deMille’s The Sowers (1916); William Desmond Taylor’s Ben Blair (1916); and many other stunning projects I got a glimpse of. But a little is better than nothing, as I’ve tried to show in an earlier entry and hope to show in later ones.

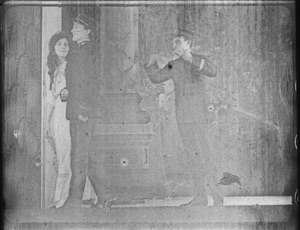

A few portions that remained were plagued by deterioration. Usually, that consists of ameba-like creatures swarming over the image. Some decadents wallow in these miasmas, especially on tinted prints. (See Lyrical Nitrate and Decasia.) Me, I can’t romanticize turning a 1910s drama or comedy into a 1960s abstract film. I want to see the story and the style, dammit.

Another form of deterioration yields a ghostly, scraped-off image. Sometimes the decay changes from shot to shot, presumably because at some points the shots were segregated for tinting and toning. Here’s The Caprices of Kitty (Smalley, 1915), with Elsie Janis watching a play. In a gag on celebrity, she’s also an actor on stage (and in drag). After the nice shot of her and her father in the audience, the stage shot makes you shudder.

A first effort to clean it up with Photoshop helps, but still…Makes you remember why all that effort on the Packard Campus is necessary.

Of course a great many copies I watched were gorgeous. Orthochromatic film, with a ton of light dumped on the sets, yields images with incredibly rich gray scales. (My Ilford photochemical black and white couldn’t capture that range.) When we saw this parlor shot from By Right of Purchase, a 1918 Norma Talmadge melodrama, James blurted out, “Clutter!” A connoisseur of dense images, James later ran it through his algorithms and found that it had a spectacular degree of clutter.

Filigreed clutter is another big reason to like the 1910s, and archives like the LoC team are keeping it visible for us.

Deterioration isn’t the only insult these movies suffer. There’s the degradation of them in oft-copied versions. Compare this shot, from Reginald Barker’s splendid William S. Hart film The Bargain (1914), with the image you get if you buy the bootleg DVD.

Shot scale changes because of video cropping, facial expressions become unreadable, the eyes go dark, and that mounted trophy in the back just disappears. Of course things go a lot better with a video version of a film restored by the Culpeper crew (Moving Image Curator Rob Stone in particular). Olive Films has just released Wagon Tracks (1919), a fine William S. Hart film, on a very pretty Blu-ray derived from a tinted Library of Congress restoration.

So it can be done well, though I still prefer to study a 35 print, preferably untinted. Call me cranky.

The Packard Campus visit brought home to me how much effort is spent saving our film heritage. That heritage includes films that are little-known, but deserve better recognition. Watching with me, astonished by the technical ingenuity and wide-ranging experimentation rushing past us, James was reminded of the Cambrian Explosion, that period of origin and rapid diversification among earthly organisms.

It’s an intriguing analogy. A mere dozen years yielded “our cinema,” as I’ve argued in this video lecture–the sturdy prototypes of moviemaking today. Yet along with enduring models of story and style came a cascade of ingenious novelties that weren’t taken up much. The 1920s, for all their innovations, tended to prune away some of the more eccentric but intriguing tendencies that burst out in the 1910s. In my next entry on the subject, I’ll offer some examples.

I owe a tremendous debt to the John W. Kluge Center for supporting my stay at the Library of Congress. Thanks especially to Ted Widmer, Director of the Center, and his colleagues Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello. Also I enjoyed enlightening conversations with Peter Brooks, in residency at the Center, and the other Kluge Chairs Timothy Breen, Jose Casanova, and Wayne Wiegand, all embarked on fascinating projects.

Thanks also to all the staff at the Packard Campus, who enthusiastically shared information about their work habits. We’re grateful to Greg and Mike for spending so much time with us.

The digital spoor on the Packard Campus leads far and wide; a Google search will yield you many nifty items. The 2007 plans for the facility are reviewed in this information-packed presentation by Greg Lukow. For something more recent, try the Wired visit by Brian Gardiner. On the digitizing side, see Boing Boing’s extensive coverage, including an interview with Greg. There’s a good half-hour C-span documentary tour led by Mike Mashon. Mike’s blog Now See Hear! offers updates on current Campus events.

Tony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait (McFarland, 2000) remains the essential source on U.S. film preservation. It has some good anecdotes about Kemp Niver, including one involving a pistol and Raymond Rohauer. Criterion has a nifty little film on wet-gate restoration of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935).

If you’re interested in film research, you need to read James Cutting’s sweeping big-data studies on film. A good summing up of part of it is “Narrative Theory and the Dynamics of Popular Movies.” There’s interesting commentary on it here from a psychologist and here from a screenwriter (who clings to the three-act model). James’s book on the formation of the canon of Impressionist painting has been invoked in Derek Thompson’s book Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction (Penguin, 2017), 23-26.

For more on visual clutter, see this paper on clutter and visual search, of which Tim Smith, master of eye movements, is a co-author; and two papers specifically on movies, by James, one with Kacie Armstrong: here and here.

DB makes Lillian bashful in The Lily and the Rose (1915).

Silent frame rates and DCP: A guest essay by Nicola Mazzanti

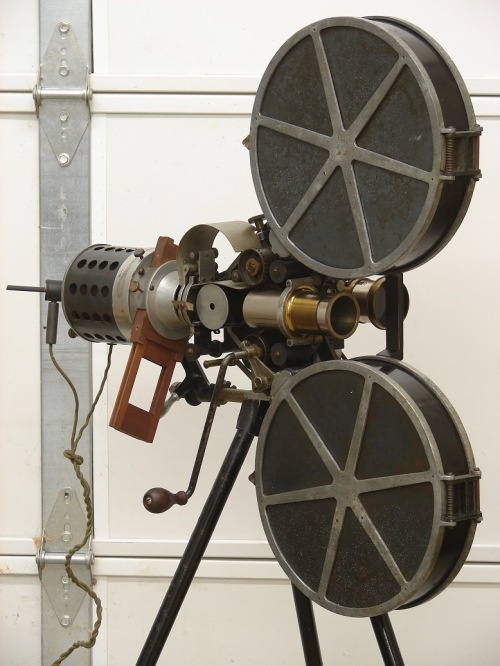

1914 Kinetoscope Victor Model I Silent Film Projector by the Victor Animatograph Co. From Pinterest, identified by Robert Van Dusen.

DB here:

The first thing you learn about silent movies is that they weren’t shown silent. The second thing is that they weren’t shown as fast as we often see them. Screened at 24 frames per second (“sound speed”), many films look rushed and silly. Those were shot at slower frame rates, like 16 fps or 18 fps. By the end of the 1920s, though, some were shot faster than sound, up to 30 fps.

Most archives and some cinémathèques and repertory theatres owned adjustable-rate film projectors, so they could provide a smooth flow of motion for most silent films. But what happened when film projectors were junked and replaced by digital projectors? How could the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), that set of files containing the movie and a host of encryption devices, offer the various “silent speeds”?

I wrote a little about this problem in Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies, but afterwards I continued to wonder how archives were coping with the matter once digital conversion was universal. The main problem is that digital projectors don’t currently provide options slower than 24 fps. Both the Hollywood studios that established the digital standard and the manufacturers that implement it simply ignored the history of cinema. Where does that leave archives, which restore, circulate, and show silent films on digital equipment?

So I asked our friend Nicola Mazzanti, Curator of the Cinematek in Brussels, about this problem. Nicola is one of the founders of the Bologna Cinema Ritrovato festival and a major consultant about digital cinema and the preservation of films in the new age. Here’s his typical provocative, pro-active answer.

Why can’t we ever make it simple?

Nicola Mazzanti, Brussels summer 2011. The plaque reads: “Mr. Bill Clinton, President of the United States of America sat at this table on 9 January 1994. He drank coffee and chatted an hour with all present.”

When they try to sell you some new product there is always the sweet thrill that now, finally, all the unpleasantness and the drawbacks, the little things that bothered you in the past, will be gone forever. Then, you realize that the car you bought was a Volkswagen diesel.

With Digital Cinema we were all told that life would be happier once we jumped onto the bandwagon. Distribution of independent films would be easier. All sorts of catalogue titles would flow joyously from the archives to the multiplex. “Alternative content,” including slightly unsharp TV programs and opera with awful close-ups and great sound, would make theatre owners rich.

Many believed the PR. Some of this became true—the usual 10% of it.

Granted, it is easier and cheaper to produce and manage a DCP than a 35mm print. And some classics did find their way to independent or repertoire theatres (the few who survived the digital switch, that is). Several archives, ours included, are enjoying these benefits of the digital switchover. And advertising an 8K or 20K or whatever-K restoration can bring in audiences. But many of us also have tons of perfectly fine 35mm of classics, and they cannot be shown any more. Why not?

*35mm projectors are basically gone.

*Some catalogue owners permit screening only their “restored DCP” (and strictly with English or French subtitles – so much for cultural diversity!).

At the end of the day the number of available classic titles went down, not up.

We could talk about this situation a long time, but let’s home in on one effect of the digital transition. The story I want to tell today is one about those “technical details” that we seem never able to get right. Only the Gods of Cinema know why.

We could talk about screen ratios in this connection, but not today. Today we talk about frame rates.

Toward a standard

Unlike video files but like a strip of film, a DCP consists of a bunch of individual frames that play nicely one after the other. The number of frames that are played back per second is defined by a simple line of code in an XML file. From the point of view of the technology in the server and the DCP format, there is no reason why we cannot play a film at any rate we like, say, 17fps. (Granted, we can’t really run it at 100fps, because of bandwidth, but you see my point.)

This is not the whole story. First of all, there is a need for a highly standardized system, or we would have the problem of a DCP playing well in one theater and at the wrong speed in the next. Then there are other issues, like the frequency of the projector or the link between the server and the projector. I will not bore you with the details. In sum, technical problems make it impossible to build what I had proposed in the first place: a hand-cranked digital projector. (I was serious.)

Yet all these technical problems could be solved, if we took a rather pragmatic approach. (Here, “pragmatic” is the PC term for “compromise.”) That’s what we archivists did, a few years ago.

At the time of publication, the Digital Cinema Initiative specs described something that did not really exist yet. The technology was only almost there. In the hurry to produce a standard that could work, it was perfectly sensible to start with only two frame rates: 24 and 48 (for 3D).

Some time later though, the issue of expanding the frame rates options came back with a vengeance. The strongest push was coming from European broadcasters who wanted to sneak their boring stuff to the cinema screens and thus called loudly for a 25fps frame rate. Then some filmmakers like Peter Jackson and James Cameron fell in love with the idea of higher rates, like 30fps and 60 for 3D (regardless of how this would balloon production budgets).

Soon the issue became geopolitical, with the Europeans pushing hard for 25fps, mostly because they considered it a victory to impose another standard on the Americans—even though they had lost the digital war as a whole. At the end, the Pandora’s box of frame rates had to be reopened, enthusiastically by some, reluctantly by others.

The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) set up a workgroup where all strong views in favor or against were represented. For the historians among you, it was first called “DC28-10 Ad-hoc Group on Additional Frame Rates” and later “21DC.10 AHG Additional Frame Rates.” We archivists, following our typical model of guerrilla resistance, sneaked onto the panel.

Technically, the archival force was the Technical Commission of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). Actually, it was Torkell Sætervadet and I who were volunteered for this “mission impossible.” Torkell is the world’s greatest expert on projection. He wrote the indispensable handbook for film projection, The Advanced Projection Manual (2006). His FIAF Digital Projection Guide, another must-read, was published in December 2012, the year film projection disappeared.

Torkell and I worked on the frame-rate problem for a couple of years. We mostly revised documents and conducted conference calls late at night (thanks to European time zones). We received some support from the more corporate members of the Workgroup. Many had never heard of lower frame rates, and the concept actually fascinated them. We also benefited from the support of Kommer Kleijn from IMAGO (the European version of the ASC), Paul Collard (then Ascent Media, now Deluxe, a profoundly competent person in the business), and Peter Wilson of High Definition and Digital Cinema Ltd.

The result: We succeeded to a great extent. We convinced the workgroup that silent rates had to be part of digital projection. True, the new standard allows only four other rates: 16, 18, 20, or 22. (To be extra-precise, due to technical issues, 18fps is in fact 18.18181818 and 22 is really 21.8181818.) But four options are quite a lot, and we decided that four were better than none.

So what we called the Archive Frame Rates standard (technically ST 428-21:2011) became part of the SMPTE standards for Digital Cinema. It can be found here. More or less in parallel, other frame rates were allowed: 25, 30, and 60fps. An announcement of this development, with commentary, can be found here.

Hurray! But don’t celebrate yet.

The Archival Frame Rates standard is not a mandatory one. The manufacturers of Digital Cinema projectors never implemented this particular standard in their machines. And archives all over the world never requested it before purchasing a projector. That, today, is the roadblock to proper screening of silent films on adjustable digital projection.

Home-made silent speed

Well, what are the alternatives?

One can produce, for example, a normal DCP at 24fps, and then use a simple piece of software (such as EasyDCP) that allows for different speeds if the DCP is played back from a computer. That feeds directly into the projector, bypassing the projector’s server. It works fine, although you have to try out several frame rates until you find the one that does sit well with the refresh rate of your projector. Otherwise, you might have some artifacts onscreen.

Alternatively, if your film’s chosen silent speed is 16fps you can easily triplicate each frame and create a 48fps DCP which would play in most theatres. 20fps would fit into 60fps, when available. For 18 and 22, however, this is no solution; they are tough frame rates anyway.

The problem with these as hoc solutions is that they are not universal. If an archive ships a DCP to another archive, someone acquainted with that file must be in the booth with a computer. Or you can just send the DCP and hope it works. Either of the two digital solutions can be used safely only in your own theatre, basically.

Hence my interest in pushing for a standardized solution. This is, I’m convinced, the best one for bringing silent films to broader public.

So I haven’t given up hope that one of the manufacturers might realize that the Archival Frame Rates standard would be a nice addition to their option package. Particularly if archives and other potential buyers start asking for it.

Does one speed fit all?

The silent frame rates are more complicated than what I’ve just outlined. Let’s go a little deeper, because it’s interesting.

When we refer to frame rates, we tend to use discrete numbers (16, 18…). But like all things analog, frame rates lay along a continuum. That ranged from 16 (sometimes lower) to 24 (sometimes higher). Anybody who worked as a projectionist knows that even with a modern projector equipped with speed variators, the actual speed can change according to the day of the week and the time of the day, depending on fluctuations on the grid.

The same variations occurred, naturally, with hand-cranked projectors and cameras. And early motor-driven machines used in the silent era also suffered unpredictable variations from moment to moment.

As a result, silent films were shot and screened at different speeds. Even the same film would have fluctuations in frame rates from scene to scene or shot to shot.

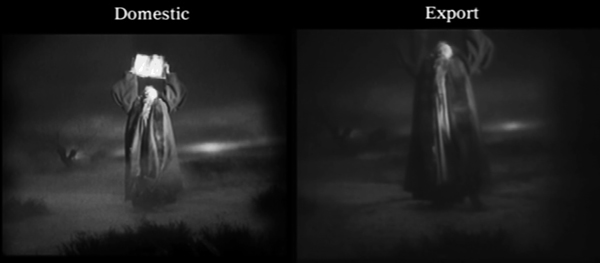

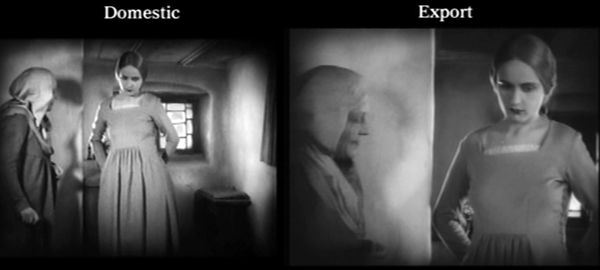

The best example I know personally is Murnau’s Faust (1926). When Luciano Berriatua and I were analyzing the existing negatives of the film, we were puzzled when we compared the two negatives from the original production. Each negative was shot with a different camera. As was common in silent film, the filmmakers provided one negative for domestic circulation and one for international distribution. In production the cameras yielded different angles on the scene–sometimes quite similar, sometimes different.

Nevertheless, the action each one captured was identical. The problem is that the two negatives were different in length!

Why? The cameras were operated by two different cameramen, each hand-cranking at a different speed. The assistant cameraman, undoubtedly younger and more enthusiastic, was cranking faster!

Such a disparity was not uncommon. On the contrary, any archivist confronted with the decision about “suggested frame rate” for a given film is confronted with a choice among many different frame rates. What one writes on the cans is always a speed that fits better on average, not necessarily on each individual shot or scene.

And the reality in archives, cinemathques and everywhere else, is this. Most silent film screenings, if not virtually all, are today executed at one speed throughout the whole picture,

There is strong, albeit anecdotal, evidence that projectionists in the silent era were encouraged to crank different sections of a movie at different speeds. Cues in some musical scores suggest that sequences may have been slowed or speeded up. Projectionists may also have chosen to accelerate chases and battles or slow down love scenes. But there’s no way to know to what extent this manipulation was a common practice.

Personally, I think that we are inevitably looking at a silent film with modern eyes. For one thing, we have a completely different approach to continuity. We ask that a restored silent film be perfectly graded, that its tinting and toning be consistent from shot to shot and scene to scene. But when we examine an original print, particularly from the ‘teens, we realize that our modern concept of pictorial continuity did not apply. It seems to have come into play in the late Twenties or later. Our assumptions about continuity make us consider narrative or visual discontinuity a technical error, or at least a trace of a more cavalier attitude towards continuity. I think that discontinuity of technique was often voluntary and sometimes deliberate.

Fun with frame rates

This point applies to frame rates as well. I am convinced that audiences in the silent era were much more relaxed towards something that we now consider so important. Otherwise, it’s difficult to understand why there so many variations in speed within one picture, and between different versions of the same film.

We should remember as well that we cannot really discuss anything “silent” without taking into consideration that it was a long and complex period of fast evolution and change. A film from the early ‘teens and one made ten years later are two different beasts, and different considerations should apply.

So, to return to our main theme: Are frame rates impossible to vary with a DCP? No—in theory.

If you decide to create your DCP at 24 fps, you can easily slow down each scene at a different rate, if you so choose. Alternatively, if the Archive Frame Rates standard were in use, you could apply your four fixed speeds (16. 18. 20. 22) to different sections of the DCP by simply creating separate “reels” and a correct playlist. This would be a bit like a DCP in which certain parts, such as the restoration credits, are actually a separate file to be played before or after the main body of the film.

Have I tried this? No. Could it work? Yes. Is it worth trying? I am not sure. Again, I am afraid we are looking for a precision that was not really part of a film screening in the silent era.

I remain strongly convinced that “old stuff,” including silent film, has an appeal for the public, and not just for few cinephiles. I also strongly believe that an archive like ours in Brussels should offer a wide range of films on DCP for screenings around the world.

In order to show a silent film in the present environment I have to do some nasty things to the images. I have to slow them down by means of software, even if some solutions work well enough to fool some archivists and historians.

If the alternative is never to show Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910) to anybody, I’d rather use some tricks to make the screening possible in a modern DCP environment. That’s better than making the film invisible. I am also old enough to remember how horrible it was in the 35mm days when there was really no way to show silent films outside a cinematheque. While we wait for archives and manufacturers to implement the fuller range of options, we must keep our films alive.

So when today a nice audience shows up to see Maudite with a pianist in a multiplex in the middle of Flanders (or Ohio or Nebraska), I admit that I’d be unhappy that I had to trick the speed to 18 fps. Yet I still consider it a victory.

For discussion of silent-film frame rates the standard point of departure is Kevin Brownlow’s 1980 article, “Silent Films: What Was the Right Speed?” Brownlow suggests that many American silent films were intended to be screened at a higher rate than the cameraman had used during filming. See also James Card, Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film (Knopf, 1994), 52-56, and Jon Marquis, “The Speed of Silence” (2011). On the revival of interest in high frame rates, see this 2011 article and Pandora’s Digital Box.

Nicola has written about other aspects of film preservation in the digital age. See his recent contribution to“The Last Picture Show,” a symposium in Artforum (October 2015), 288-291.Tacita Dean and Amy Taubin contribute to this as well.

The magnificent Masters of Cinema DVD set of Faust includes both the domestic German version and the export version, along with a lengthy comparison of them, from which I’ve drawn my illustrations.

Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910).

An auteur, three archives, and the archivist as auteur

City of Sadness (1989).

DB here:

The books have been piling up again, and so I pass along some recommendations. This time the volumes are unusually handsome. Apart from what they say, these publications display how sumptuous a serious film book can be.

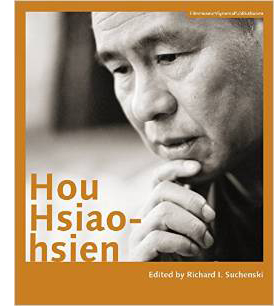

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Some of our top critics and scholars have contributed essays. From Japan comes Hasumi Shigehiko on Flowers of Shanghai; from France, Jean-Michel Frodon on Hou’s collaboration with Chu Tien-wen; from Canada, James Quandt, eloquent as ever on Three Times. American scholars are here too. We have Jean Ma on The Puppetmaster, Abe Mark Nornes on calligraphy and frame space, Kent Jones on time in Hou, and James Udden on Dust in the Wind. Jim is author of the first English-language book on Hou and a contributor to this website. To these essays are added the unique perspectives offered by Taiwanese observers Peggy Chiao on City of Sadness and Wen Tien-hsiang on unmarried women in Hou. A wide-ranging introduction by Richard brings out virtually all the artistic, political, and cultural issues that have been raised by Hou’s body of work.

Unabashedly auteurist—and what’s wrong with that?—the collection adds even more value by including an interview with Hou and Chu, who supply precious information about the work-in-progress The Assassin. There are also statements by three distinguished directors: Olivier Assayas, Jia Zhang-ke, and Koreeda Hirokazu. Koreeda notes: “Life’s details (like eating) should be respected.”

We learn as well about the craft behind the artistry. We get a cascade of information from artistic collaborators, including cinematographers, sound designers, actors and others. For example, Tu Duu-chih, sound expert, says: “What [Hou] wants is a natural form of expression and he always manages the atmosphere to meet his needs. If he shoots a drinking scene, for example, he will select real dishes and alcohol and they must be delicious.” Delicious is a good word for this book too, an absolute necessity for every serious cinephile.

Birthday greetings to Vienna and Brussels

Speaking of the Austrian Filmmuseum, it celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year. To celebrate, it has issued a heavyweight, unorthodox boxed set, The Austrian Film Museum at Fifty. Director Alexander Horwath has done a monumental job in bringing a great deal of material together, creating not only a history of the Filmmuseum but a real contribution to international film culture.

In volume one, Aufbrechen (Setting Out), Eszter Kondor provides a history of the institution, with emphasis on its emergence the 1960s and 1970s. Volume two pays homage to Béla Balázs with the title Das sichbare Kino (The Visible Cinema). This is a plump anthology of texts, pictures, and documents from the museum’s history. Given the fact that Peter Kubelka was curator for many years, you’re not surprised to find a letter from Michael Snow and an email from Ken Jacobs. But I didn’t expect an interview with Groucho Marx (letter appended) and correspondence from Don Siegel. This volume also includes a complete record of programs at the museum.

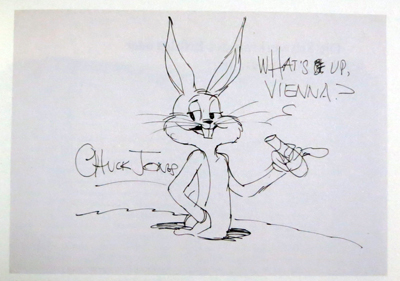

Volume three, Kollection, is a visual treat. It gives us a short history of film in fifty items. The survey includes The Unfinished Letter, a 22mm Edison film ca. 1911-1913, outtakes from Murnau’s Tabu, Morgan Fisher’s site-specific Screening Room (1968), Kurt Kren’s leather jacket, Chuck Jones’ What’s Up, Vienna? (1983), and frames from Norbert Pfaffenbichler’s dizzying Notes on Film 03: Mosaik Mécanique (2007).

The texts in all of the books are in German, but there are so many posters, photos, sketches, diagrams, and storyboards (one by Vertov) that you learn merely by browsing. These volumes are a must for research libraries with a focus on film.

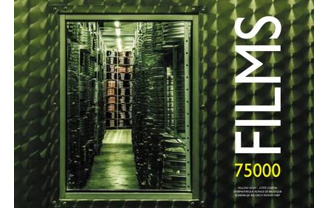

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

Film archiving is already changing and in a few years will be very different from what it is now. New skills, new machines, new people. As no book like this one exists about film archiving we wanted to make sure that at least one is published before the picture changes completely.

What will change? Chiefly, the sheer tactility of the work.

Inspecting a film to check its conditions and its history is all about a physical relation with the material. While winding through a reel of film your fingers run along the edges to feel imperfections and damages. One bends a piece of film to assess its brittleness, caresses a splice to check its resistance. . . .

In other words, it is a precise, careful, dedicated and highly specialized work that often is as tedious as rewinding hundreds and thousand of reels (by hand, as electric motors are often dangerous to the film). An uneventful process until you stumble upon a lost film or a camera negative or perhaps just a beautiful copy in which the colours are perfectly preserved. And the beauty of those images takes your breath away, the thrill of the discovery repays you for all the hours of boring inspections.

To capture both the routine and the exhilaration, Nicola let three photographers document, without constraint, what they saw behind the scenes of the Cinematek. Xavier Harck, Jimmy Kets, and Marie-Françoise Plissart took their cameras into the vaults, the work spaces, the projection rooms, even the loading docks. The images are gorgeous and radiate the touch and heft of reel after reel, can upon can, in profusion that evokes Resnais’ Toute la mémoire du monde.

Along with the photos are three essays about film archives. They are personal reflections on cinematheques and their place in film culture. Dominique Païni writes (in French) about how access to films changed during his years as director of the Cinematheque Francaise. Erich de Kuyper, filmmaker and novelist, reflects in Flemish on guiding the Amsterdam Film Museum and creating the programs there. I contributed a piece in English that tries to fit my personal research work into broader trends of film archiving. My essay is elsewhere on this site.

The age of impresarios

Langlois is the dragon who guards our treasures.

–Jean Cocteau

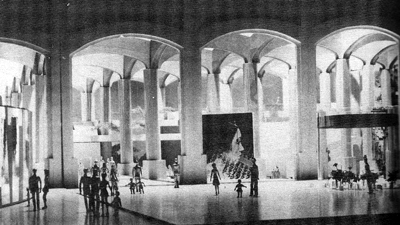

In spring of 1973 the New York Times announced that a city board had approved the leasing of a building that would house the City Center Cinematheque. This was to be the American counterpart of the Cinémathèque Française, and Henri Langlois was to be its director.

Langlois’ project was as vast and flamboyant as the man himself. An old storage building under the Queensboro Bridge, on First Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, would be converted into a cathedral of cinema. I. M. Pei would design the new building. (One sketch is above.) There would be three auditoriums, a staff screening room, an exhibition space, a restaurant, a bookstore, and a flower market. Programs would draw upon Langlois’ archive of 60,000 titles, and there would be screenings from morning to midnight, offering as many as fourteen films a day. Langlois predicted that attendance would surpass a million a year.

My own encounters with Langlois, brief though they were, came at just this moment. I needed to see several French silent films for my dissertation work, and in 1972-1973 I wrote to Langlois asking for permission to visit his archive. Thanks to Sallie Blumenthal, we made contact and he gave me permission. In July, during the summer of Watergate, I arrived at the Cinémathèque. An expansive Langlois welcomed me and gave me a tour of the Musée du cinema, which had been somewhat prematurely opened. Jean-Louis Barrault’s costume from Les Enfants du Paradis was draped on a coat hanger nailed to a wall. During my two months in Paris, thanks to Langlois and Mary Meerson, I saw several rare films on Marie Epstein’s viewing table.

I have sometimes wondered if my stay there was an accident of timing. Perhaps as a young American I benefited from Langlois’ high hopes for his transatlantic alliance. Pressed by money problems in Paris, he could imagine that the American branch of the Cinémathèque would vindicate his vision of a motion picture museum without walls: films circulating everywhere, films shown all the time, no film too minor to merit attention. Had the City Center venue come to fruition, it would have overshadowed the Museum of Modern Art, Manhattan’s temple of cinema history. But the project collapsed fairly soon. It required private financing, and during the recession and the oil crisis money was hard to come by.

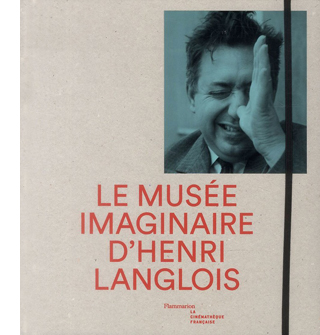

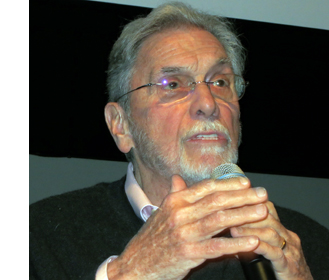

Langlois’ American adventure is just one episode in the tapestry presented in another archive-related anniversary volume: Le Musée imaginaire d’Henri Langlois. Edited by Dominique Païni, this de luxe production accompanied the Cinémathèque’s massive exposition from April to August. If Langlois were still living, he’d be 100 this year, and the sumptuousness of this catalogue is in part a testimony to what he accomplished. He helped make cinema equal to the other arts in cultural significance. But the enterprise is not too serious: Païni has made the volume’s emblem the famous shot, taken by an unknown hand, of Langlois in the kiss-my-ass salute.

The menu is familiar. There are informative essays by various hands, interspersed with illustrations and documents. But the execution is extraordinary. Reminiscent of 1920s publications, on rough paper and with decentered blocks of type, this square volume seduces you into sustained browsing. Moreover, it contains reproductions of artworks related to Langlois and his institution. We have works by Beuys, Chagall, Duchamp, Fischinger, Léger, Matisse, Miró, Picabia, Richter, Severini, and Survage—all connected, somehow to Langlois and cinema. There are frames from Le Métro, a 1934 film by Langlois and Franju., There are guest-book signatures, catalogue covers, correspondence, and much more.

The catalogue of the exposition is accompanied by a slender but no less ingratiating biographical chronology, festooned with still more images. Mais qui est ce Monsieur Langlois? opens with a striking portrait by Henri Cartier-Bresson and ends with the telegram sent by Jean Renoir after Langlois’ death in 1977. “We have lost our guide, and now we feel alone in the forest.”

I met Langlois in the days of rivalry among archives, a good deal of it triggered by him. If you were welcomed to Archive X, and word got to Archive Y, that venue would shun you. Surveying these books, I was struck by their quiet assumption that archives must collaborate on projects and share their treasures. After Langlois, archiving became more cooperative, more routinized, more professional, and–Langlois and his allies would say–more boring. We may not need dragons now. Perhaps, though, we had to go through the turmoil of the Age of Impresarios in order to appreciate why collecting films was so important.

For some ideas on Hou’s visual style, see Chapter 5 of my Figures Traced in Light, this entry, and a discussion of the early films on this site.

Henri Langlois. Photo by Pierre Boulat.