Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

Where movies live and breathe

Thanks to web tsarina Meg Hamel, I’ve just posted a new essay (you also see it on the left column). It’s a historical and personal discussion of film archives. It could also be titled, “How I Spent Nearly 40 Summer Vacations.”

It originally appeared in Nicola Mazzanti’s book, 75000 Films. More on that book and related topics soon! After I get done arm-wrestling Adieu au langage, the latest work of the world’s youngest 83-year-old filmmaker.

What’s left to discover today? Plenty.

Der Tunnel (William Wauer, 1915).

DB here:

Being a cinephile is partly about making discoveries. True, one person’s discovery is another’s war horse. But nobody has seen everything, so you can always hope to find something fresh. There’s also the inviting prospect of introducing a little-known film to a wider community–students in a course, an audience at a festival, readers of a blog.

A festival like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato (we covered this year’s edition here and here and here) offers what you might call curated discoveries. Expert programmers dig out treasures they want to give wider exposure. Such festivals are both efficient–you’re likely to find many new things in a short span–and contagiously exciting, because other movie lovers are alongside you to talk about what you’re seeing.

A year-round regimen of curated discoveries is a large part of the mission of the world’s cinematheques. This is why places like MoMA, LACMA, MoMI, BAM, TIFF, ICA, and other acronymically identified showcases are precious shrines to serious moviegoing.

But other discoveries are made in a more solitary way. Film researchers, for instance, ask questions, and some of those can really only be answered by visiting film archives. Sometimes we need to look at fairly obscure movies. And despite the rise of home video, there are plenty of obscure movies that can be seen only in archives. It’s here that the programmers of Ritrovato and Pordenone’s Giornate del Cinema Muto come to select their featured programs.

Archive discoveries aren’t predictable, and many are likely to be of interest only to specialists. Such was the case, mostly, with our archive visits this summer. But as in years past (tagged here), all our archive adventures yielded pure happiness.

This time I concentrated on films from the 1910s-early 1920s films because I hope to make more video lectures about this, the most crucial phase of film history. (One lecture is already here.) In our archive-hopping, we saw films I was completely unfamiliar with. I re-watched some films I’d seen before and found new things in them. I detected some things of interest in films I hadn’t known. Most exciting was our viewing of a major film that has gone unnoticed in standard film histories.

In the steps of Jakobson and Mukarovský

Love Is Torment ( Vladimír Slavínský, Přemysl Pražský, 1920); production still.

First stop was Prague, where I was invited to give two talks. At the NFA we saw two films on a flatbed: a portion of Feuillade’s Le Fils du Filibustier (1922) and a cut-down version of Volkoff’s La Maison du mystere (1922), the latter a big gap in our viewing. The expurgated Maison came off as rather drab, lacking nearly all the big moments much discussed in reports like James Quandt’s from a decade ago. So we search on for the full version. . . .

As for the Feuillade: Le Fils du Filibustier was his last “ciné-roman.” Our two-reel segment, which seemed fairly complete, confirmed his late-life switch to fairly fast, Hollywood-style editing, with surprisingly varied angles.Again, though, we yearn to see the entirety of this pirate saga.

On another day the archive kindly screened several 1910s-early 1920s Czech films for us. Our hosts Lucie Česálková and Radomir Kokes translated the titles and provided contexts. Among the choices were Devil Girl (Certisko, 1918), with a protagonist who’s more of a tomboy than a possessed soul; and the full-bore melodrama Love Is Torment (Láska je utrpením, 1919). The plot, outlined here, involves scaling and jumping off a tower, twice. Once it’s a stunt for a film within the film, the second time (below) it’s the real thing.

Radomir explained to us that one of the co-directors, Vladimír Slavínský, seemed in his 1920s films to specialize in building two reels (often the third and fourth) in a “classical” fashion before letting the other three become more episodic. And indeed, most of the late 1910s-early 1920s films we saw were up to speed with other European filmmaking, in their staging, cutting, and use of intertitles.

We look forward to viewing more Czech films as the opportunity arises. A culture that gave us Prague Structuralism is definitely worth getting to know better. In the meantime, the journal Illuminace, edited by Lucie, is injecting a great deal of energy into local film studies, and the archive is entering a fresh phase with its new director, Michal Bregant.

3D excavations

Der Hund von Baskerville (1914).

In Munich, we reconnected with our old friends Andreas Rost, now retired from administering the city’s cultural affairs, and Stefan Drössler, director of the Munich Filmmuseum. We also reunited with the stalwart archivists Klaus Volkmer, Gerhard Ullmann, and Christoph Michel. Talking with them, we realized we hadn’t been back for over ten years. Klaus and Gerhard were warm and helpful during our earlier visits.

One rainy afternoon, Stefan shared his research on the history of 3D. He presented a spectacular PowerPoint, with rare images and some truly startling revelations. He has given this talk at intervals over the years, but it grows and deepens as he discovers more. Accompanying it, he screened some Soviet 3D films, including the 1946 Robinzon Cruzo. This mind-bending item was made with diptych images, so that the projected image turned out to be slightly vertical. The soundtrack runs down the middle.

The director, Aleksandr Andriyevsky, made excellent use of 3D to evoke the stringy vines and protruding leaves of Crusoe’s island. Amid all the talk today about glasses-free 3D, it’s interesting to learn that Soviet researchers prepared such a system. Stefan’s archaeology of 3D, for me at least, was a pretty big discovery.

At Munich we also saw three silent German titles. Two were associated that resourceful self-promoter Richard Oswald. Sein eigner Morder was a 1914 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde, directed by Max Mack from Oswald’s screenplay. Shot in big sets, it spared time for the occasional huge close-up. The other film was Oswald’s semi-comic adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles (Der Hund von Baskerville, dir. Rudolf Meinert, 1914), which he had already turned into a play. The sleuth isn’t exactly our idea of Holmes (see above), and he isn’t as quick-witted, I thought, but it was an enjoyable item. Dr. Watson has a sort of tablet which picks up messages; Holmes’ orders are spelled out in lights on a grid. Stefan rightly called it a 1914 laptop.

As for the third film: More about that coming up.

The shadow of Hollywood

Les Deux gamines (1921).

At Brussels, thanks to the cooperation of the Cinematek, I was able to see several items for the first time, and two held considerable interest. The short The Meeting (1917), by John Robertson, showed a real flexibility in laying out the space of a cabin both in front of the camera and behind it. Most interior scenes in 1900-1915 cinema bring characters in from a doorway in the rear of the set (as Feuillade does in his 1910s films) or straight in from the sides, perpendicular to the camera (as Griffith tends to do). The Meeting shows that the diagonal screen exits and entrances that we see in exteriors were coming into use in interior sets as well.

Another 1917 film, Frank Lloyd’s A Tale of Two Cities, was further support for the idea that American continuity filmmaking was well-established and already being refined at the period. Dickens’ classic tale is handled with dispatch–rapid exposition, smooth crosscutting to set up the plot lines–and the film makes dynamic use of crowds surging through well-composed, starkly lit frames. There are also some remarkably expressive close-ups, evidently made with wide-angle lenses.

To clinch a plot point, the resemblance of aristocrat Charles Darnay to British solicitor Sydney Carton, the star William Farnum plays both characters. Not much of a problem if you keep the characters in separate shots; the good old Kuleshov effect (aka known as constructive editing) makes it easy. At this period, though, filmmakers were perfecting ways to show one actor in two roles within a single shot. The most famous examples involve Paul Wegener in The Student of Prague (1913) and Mary Pickford in Stella Maris (1918).

Cinematographer George Schneiderman contrives some really convincing multiple-exposures showing Farnum as both Darnay and Carton. There are some standard trick compositions putting Farnum on each side of the screen, but several images take the next step and let the actor cross the invisible line separating the two halves. At another point, we get a flashy passage showing the two facing one another in court, followed by a “Wellesian” angle of the two characters’ heads in the same frame.

Hollywood’s pride in photorealistic special effects, so overwhelmingly apparent today, has deep roots.

Part of my Brussels visit involved checking and fleshing out notes on certain films I saw many years ago. Some were wonderful William S. Hart movies like Keno Bates, Liar (1915; surely one of the best film titles ever). There was, inevitably, Feuillade as well. The influence of Hollywood was powerful in the ciné-roman Les Deux gamines (1921). This baby, released in 12 parts originally, runs nearly 27,000 feet. At 20 frames per second, it would take six hours to screen. What with changing reels, making notes, counting shots, pausing to study things, and taking stills, Kristin and I took about ten hours to watch it.

Was it worth it? An adaptation of a popular stage melodrama, it can’t count as one of Feuillade’s major achievements. Two girls are left alone when their mother is reported dead. They are adopted by their gloomy grandpa and tormented by his overbearing housekeeper. They become the target of kidnapping by gangster pals of their father, who has divorced their mother and turned to a life of petty crime. Their allies are their young cousins, a wealthy benefactor, and their godfather and music-hall star Chambertin. Everything ends happily, if you count the father’s redemptive sacrifice on behalf of a pregnant woman.

Les Deux Gamines is determined to delay its ending by any means necessary. Form here definitely follows format; Feuillade fills out the serial structure with plots big and small. (Shklovsky would love it.) There are incessant abductions, escapes, rescues, coincidental meetings, and timely reformations, plus at least three cases of people wrongly assumed to be dead. All of this is accompanied by an endless exchange of telegrams and letters. People are forever piling into and out of carriages, train cars, and taxis. Such material serves as makeweight for some genuinely big moments, including a cliff-hanging scene and a stunning climax in a smuggler’s warehouse stuffed with gigantic bales of used clothing.

Like Le Fils du Filibustier, this film shows Feuillade trying to change with the times. The supple long-take staging of Fantômas and Les Vampires and Tih-Minh mostly goes away, to be replaced by rapid editing. Feuillade employs standard continuity devices, as when the grandfather discovers that the kids have sneaked out at night and are trying to return by scaling the gate.

Feuillade varies his angles and lighting to accentuate the moment of visual discovery. Elsewhere, some appeals to “offscreen sound” (cutaways to doorbells and telephones) built up to a surprise effect.

But by the energetic standards of, say, Robertson or Lloyd several years earlier, Les Deux gamines is fairly timid. Feuillade doesn’t explore editing resources very much here, not even as much as in Le Fils du Filibustier. The fairly quick cutting pace stems partly from the stratagem of having dialogue titles interrupt static two-shots of characters talking to one another. This sort of proto-talkie-technique yields efficient storytelling but not much visual momentum. Feuillade tried flashier things in other films of the period (see here).

Hours and hours of nothing but Bauers

The Alarm (1917).

Yevgeni Bauer, one of the master directors of the 1910s, remains lamentably unknown. About two dozen of his over seventy films survive, but many of the ones we have lack intertitles. A few of his films are available on DVD (most obviously here; less obviously here). He died of penumonia in 1917, between the February revolution and the Soviets’ coup d’état in October. He was only 52.

My first archive-report entry back in 2007 recorded my interest in Bauer, and I’ve returned to his films over the years. Now here I was watching some again, confirming things I found of interest then, and discovering (that word again) new felicities. I hope to say more in those short video lectures on the 1910s, but I can’t leave without giving you a taste of his qualities.

Two of the films I saw this time were from 1917. The Alarm (Nabat) came out in May 1917, just before Bauer’s death in June. Originally running eight reels, it was cut down after the initial release, and that’s evidently the version we have. For Luck (Za Schast’em, September 1917) was directed by Bauer from his sickbed. Both films are fairly hard to follow. The Alarm lacks intertitles, and For Luck has many fewer than it had originally.

The two films are of exceptional interest, though. For one thing, there’s the involvement of Lev Kuleshow, who at the age of eighteen served as art director for the earlier film and, apparently reluctantly, as an actor in the later one. More important, the films remain as beautifully designed, staged, and acted as ever.

The Alarm is a wide-ranging drama set before the February upheaval. The drama involves romantic intrigues among the upper class, interwoven with a workers’ rebellion against a master capitalist. The millionaire Zeleznov holds court in a vast office with chairs bearing ominous spires and spiky arches; the windows open onto a view of his factory. A long-shot view is above; here’s a sample of how Bauer shows off his decor in something akin to shot/ reverse-shot.

The idea of capitalism as an overreaching religious striving is evoked by turning Zeleznov’s headquarters into a Symbolist cathedral. And looking at the second shot, you wonder whether Kuleshov’s inclination to stage his own scenes against pure black backgrounds has its source in his work for the man he called “my favorite director and teacher.”

As ever, Bauer makes fluid use of depth. He choreographs meetings of Zeleznov’s brain trust in ever-changing arrangements, and he eases a man out of a boudoir through a mirror reflection over a woman’s fur-draped shoulder.

Compared to the scale of The Alarm, For Luck is decidedly low-key–a bourgeois melodrama that extends barely beyond an anecdote. Zoya has been a widow for ten years, and she hopes to marry the loyal family friend Dmitri. But Zoya’s daughter Lee hasn’t yet reconciled to losing her father. The couple hope that Lee has worked out her grief during her dalliance with a young painter (played by Kuleshov), but she reveals that all along she has hoped to marry Dmitri.

The Alarm used some extravagant sets, both for interior and exterior scenes, but a good deal of For Luck takes place in parks and terraces. The sincere Enrico sketches Lee in front of swans, and they steal some moments in a bower.

Still, there are some interiors boasting Bauer’s famous pillars and columns, which create massive, encapsulated spaces. Here Zoya looks off, in depth, at the ailing Lee, in bed on the far right.

Sharp-eyed Bauerians will notice the mirror set into the left wall, reflecting Zoya. Kuleshov, who did art direction on this as well as The Alarm, worried more about the trumpet-blowing Cupid floating between the pillars on the left. (“It turned out bad on the screen–incomprehensible and inexpressive.”) He did think that the tonalities of the set worked well: “As an experiment, I put up a set painted in shades of white that were ever so slightly different from one another.”

“Ever so slightly different” isn’t a bad evocation of the tiny variations of shape and shade, light and texture, that characterize Bauer’s ripe, sometimes overripe, imagery. This is a social class on the way out, but it leaves behind a great glow.

Tunnel: Vision

The Tunnel (1915).

In 1913, the popular novelist Bernhard Kellermann published Der Tunnel. It’s not quite science-fiction, more a prophetic fiction or realist fantasy in the vein of Things to Come. The book became a best-seller and the basis of a 1915 film directed by William Wauer.

The plot would gladden the heart of Ayn Rand. A visionary engineer persuades investors to fund building an undersea railway connecting France to the United States (specifically, New Jersey). No meddling government gets in the way of this titanic effort of will. Max Allan buys land for the stations, hires diggers from around the world, and risks everything he has. The obstacles are many. An explosion scares off workers; there is a strike; impatient stockholders raid and burn the company headquarters.

Max Allan moves forward undeterred, though he hesitates when his wife and child are stoned to death by a mob. After twenty-six years, the railway is opened. Max, along with his new wife (the daughter of his chief backer), proves it’s safe by taking the first transatlantic train. The event is covered by television, projected on big screens around the world (above). In the original novel, a film company was commissioned to document every stage of work.

The book skimps on characterization, and the film is even less concerned with psychology. Once the character relations are sketched, Wauer goes for shock and awe. The Tunnel‘s thrilling crowd scenes of work, fire, devastation, riots, and panic look completely modern. Bird’s-eye views of stock-market frenzy anticipate Pudovkin’s End of St. Petersburg, and Wauer creates an Eisensteinian percussion of light and rushing movement as workers flee the tunnel collapse.

For the sequences showing the tunnel construction, Wauer supplies violent alternations of bright and dark as men, stripped and sweaty, attack the rock face. The variety of camera positions and illumination is really impressive.

Comparisons with The Big Film of 1915 are inevitable. The intimate scenes of The Tunnel are far less delicately realized than the romance and family life of The Birth of a Nation, and the battle scenes in Birth have a greater scope than what Wauer summons up. But Wauer’s handling of crowds is more vigorous than Griffith’s riots at the climax of Birth, and his pictorial sense is in some ways more refined, even “modern.” There’s little in Birth as daringly composed as the static long shot surmounting today’s entry.

Wauer can handle small-scale action very crisply. The opening scene in an opera house creates low-angled depth compositions more arresting than Griffith’s depiction of Ford’s Theatre. Max’s wife, in one box, is watching his efforts to attract funding from the millionaire Lloyd. Wauer constantly varies his camera setups to highlight Max’s wife in the background studying Lloyd’s daughter, sensing in her a rival for her husband. Whether the angle is high or low, the wife’s presence in her distant box is signaled at the top of the frame.

The second and third shots above present similar but not identical setups, adjusted to reset the depth composition.

It was at Munich’s Filmmuseum a decade ago that I first encountered the brooding power of Robert Reinert’s Opium (1919) and Nerven (1919), the latter now available on DVD. I was convinced that Nerven was as important, and in some ways more innovative, than the venerated Caligari. Now the conviction grows on me that in The Tunnel we have another galvanizing, outlandish masterwork of the 1910s. I hope it will somehow get circulated so that wider audiences can discover it. Yeah, that’s the word I want: discover.

Without archivists, no archives. We’re grateful to Michal Bregant, head of the Czech Republic’s archive, for access to films and for his companionship during our visit. Thanks as well to Lucie Česálková, our host; her knowledgable colleague Radomir Kokes (who kindly corrected the initial version of this post); Petra Dominkova, our Czech translator; and Vaclav Kofron, editor of the Czech versions of our books. Lucie supplied the frame enlargement from Love Is Torment. As well: Good luck to the Kino Světozor!

In Munich, we owe a huge debt to archive chief Stefan Drössler, for his generous sharing of information and his and Klaus Volkmer’s rehabilitation of The Tunnel. Stefan also provided the images from Robinson Crusoe and The Hound of the Baskervilles. Coming up is his work for the annual Bonn International Silent Film Festival, 7-17 August. Thanks as well to Gerhard Ullmann and Christoph Michel.

In Brussels, as ever, the Cinematek has made us welcome, and we thank archive director and long-time friend Nicola Mazzanti and vault supervisor Francis Malfliet. Over the last thirty years, a great deal of our research has depended upon the cooperation the Cinematek leadership: Jacques Ledoux, Gabrielle Claes, and now Nicola.

My quotations from Kuleshov come from Silent Witnesses: Early Russian Films, 1908-1919, ed. Yuri Tsivian and Paolo Cherchi Usai (Pordenone: Giornate del Cinema Muto, 1990), 388-390.

There’s a chapter on Feuillade in my Figures Traced in Light, where Bauer is discussed as well. My essay on Robert Reinert is in Poetics of Cinema.

Thanks to Antti Alanen for correction of a misspelled title. Speaking of discoveries, you’ll find plenty on his wonderful Film Diary site. During his recent trip to Paris, he’s writing about art exhibitions, Dominique Paini’s Langlois exposition at the Cinémathèque, and Godard’s Adieu au langage.

Screening at the Czech Republic’s National Film Archive. From left: Michal Večeřa, Tomáš Lebeda, Radomir Kokes, Lucie Česálková, and Kristin.

Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book

Gipsy Anne (1920).

Kristin here:

A stack of new DVDs/BDs and books has been gradually building up on the floor in a corner of my study. I’ve been meaning to blog about them, but first I had to catch up with viewing and reading. Or did I? With this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato starting next week, I suddenly realized that the DVDs at the bottom of the pile were ones I bought there last year! Clearly, I would never catch up.

So this entry aims to notify you of releases, many obscure, that you may so far have missed. Mostly the DVDs and BDs come from the dedicated archives and independent home-video companies that release historical rarities and restorations.

Early Scandinavian films

I don’t think I had ever seen a Norwegian silent film, apart from the one Carl Dreyer made there, Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1925). Though produced between Master of the House and the wonderful La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, The Bride of Glomdal is unquestionably one of Dreyer’s lesser works.

In the sales room at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, one stand was selling four new releases of Norwegian and Swedish silent and early sound films. All were issued by the Norsk FilmInstitutt.

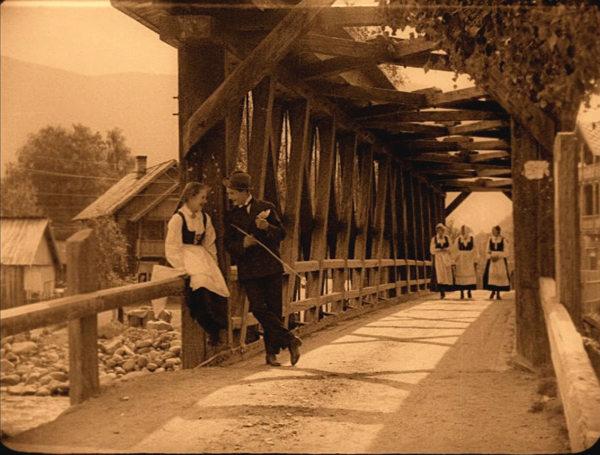

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

This is the only one of these Norwegian films that I have so far watched, and it’s a remarkable one. Clearly Breistein and his cinematographer Gunnar Nilsen-Vig were influenced by the great Swedish films of Sjöström and Stiller, and though Gipsy Ann is not up to the best work of those two, it shares the same feeling for landscape for for allowing a melodramatic situation to develop slowly and in unexpected ways.

It tells the story of a foundling child, Anne taken in by a widow who owns a large farm and who raises the girl alongside her son, Haldor. Haldor is a timid boy, constantly led astray by the adventurous Anne. Once they grow up, the two fall in love, but Haldor’s mother pushes her son into an engagement with a young woman from a well-to-do family. In the meantime, Jon, a humble tenant farmer working for the widow, falls in love with Anne, who snubs him.

Gipsy Anne has none of the clumsiness in lighting and staging that one so often sees in European films of the period around 1920. The cinematography is beautiful, as the frame at the top shows. Breistein has mastered shot/reverse shot and other aspects of analytical editing. The lighting is impressive, with some interiors using a strong backlight through windows and a soft fill that gives a sense of realism (left).

The film also sets up neat visual parallels. In a scene in Anne’s childhood (below left), she hides by an old farm building and curiously spies on some local lovers. Much later, she lurks heartbroken by Haldor’s lavish new house as he shows it to his fiancée:

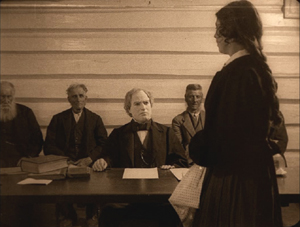

There are even some planimetric shots that yield dramatic compositions, one when Jon comforts the young Anne when she learns that she was adopted, and another, much later, when Anne is in court testifying about the fire that burned down Haldor’s new house:

Again there is a parallel, since Anne is hiding her own guilt in starting the fire, and Jon is about to falsely confess to the crime to protect her. (There’s also a hint at influence from Dreyer in that courtroom shot.)

Of the four releases, Fante-Anne is the only one put out in a Blu-ray version, packaged along with a DVD and an informative booklet in Norwegian and English. The print, with toning and a pleasantly rustic-sounding score, has English subtitles. Oddly enough, the Norsk Filminstitutt does not have an online shop. The film is available from at least two Norwegian online dealers in Scandinavian videos, Nordicdvd and Dvdhuset. It can also be ordered from an American source, Blu-ray.com.

Markens Grøde (The Growth of the Soil) was made only a year later, in 1921; it was directed by Gunnar Sommerfeldt and is another rural melodrama, adapted from a Nobel Prize-winning novel of the same title. This release is 89 minutes long and includes subtitles in English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian. It, too, can be ordered from Nordicdvd and DVDhuset.

The third release is an epic film, Brudeferden i Hardanger (The Bridal Party in Hardanger, 1926). Its two parts run 104 and 74 minutes; it was also directed by Rasmus Breistein, with cinematography by Gunnar Nilsen-Vig. DVDhuset carries it, but not Nordicdvd. It is, however, available from Amazon.uk. It has English subtitles.

Finally there is “Bjørnson på film,” a compilation of three early films based on the pastoral writings of Nobel Prize-winning author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and was issued in 2010, the centenary year of the author’s death. Two of these are Swedish productions: Synnøve Solbakken (1919, director John W. Brunius) and Et Farlig Frieri (A Dangerous Proposal, 1919, director Rune Carlsten). Lars Hansen stars in both, and Karin Molander co-stars in Synnøve Solbakken. The third is an early Norwegian talkie, En Glad Gutt (A Happy Boy, 1932, director John W. Brunius).

After considerable searching, I can find no online source for this 2-DVD set. Perhaps it will become available. Otherwise you’ll have to come to Il Cinema Ritrovato and see if it’s on sale again. If not, at least you will have a great time!

All these releases are PAL, though Fante-Anne is also Blu-ray region B; they would all need to be played on a multi-standard machine.

(Mostly) American treasures

The well-known and invaluable “Treasures” series from the National Film Preservation Foundation has become somewhat difficult to keep track of. It started with “Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films.” That was followed by “More Treasures from American Film Archives: 1894-1931.” After that volume numbers appeared, and the references to archives were dropped in favor of thematic collections: “Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934” and “American Treasures IV: Avant Garde 1947-1986.” Then Roman numerals disappeared with “Treasures 5: The West 1898-1938.”(The ones linked are still in print.)

Now we have an unnumbered entry, but it’s still part of the series: “Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive.” Most readers will recall that in 2010 it was announced that about 75 films had been found in the New Zealand Film Archive. News coverage mostly centered on John Ford’s 1927 feature Upstream, which had up to that point been lost. That film forms the central attraction for this new release.

It also includes, however, an incomplete print of a distinctly non-American film, The White Shadow (1924). It was directed by Graham Cutts, but it is mainly of interest now as a film on which the young Alfred Hitchcock worked in several capacities. He wrote the script, based on a novel, and was assistant director, editor, and art director. Despite the enthusiastic tone of the program notes in the booklet accompanying this set, there is little detectable of the later Hitch. The story is ludicrously far-fetched, depending on the old good twin/bad twin contrast, with Betty Compson in both roles (above). At various points the twins pretend to be each other, much to the confusion of the bad twin’s fiancé, played by Clive Brook. The convoluted plot becomes even more so when a series of titles tries to convey the action of the missing final three reels.

The film has its moments. Cutts, who was a decent if not outstanding director, manages some lovely compositions, as with the backlighting in the night interior below left. As with many of Hitchcock’s sets for the film, this one is pretty standard-issue. He obviously had some fun with the set for the tavern called The Cat Who Laughs. It looks a bit jumbled, but it’s actually full of little areas that Cutts uses effectively for picking out pieces of action amid the chaos:

So the Treasures series moves on, as does the Foundation. Not all of the discovered prints made it onto the DVD set. Several more have been preserved since and generously made available for free online viewing at the Foundation’s website; more will be added as the restorations are completed.

Blu-ray USA

American classics continue to make their way onto BD.

Flicker Alley has teamed with the Blackhawk Films Collection to release The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, director Wallace Worsley). No original 35mm negative or print is known to survive, so this release was mastered from a 16mm tinted copy struck at some point from the original negative. Some restrained digital restoration was done to clean it up a bit. The extras include an essay and audio commentary by Michael F. Blake and a 1915 film, Alas and Alack, with Chaney in his pre-movie star days playing a hunchback.

The film is available at Flicker Alley’s website, where you can also pre-order their three upcoming releases: a set of all Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies (1916-17); the first volume of The Mack Sennett Collection, including 50 films; and We’re in the Movies, which collects some early local films made by itinerant moviemakers, as well as Steve Schaller’s 1983 documentary, When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, about the first film made in Wisconsin. There’s also a documentary about a small local theater in Los Angeles that showed silent films in the sound age.

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation will celebrate its centennial next year, and now it’s also out on Blu-ray, from both Kino Classics in the USA and Eureka! in the UK. Both have the same new restoration from 35mm elements accompanied by the same score. The extras also appear to be identical–most notably seven Biograph shorts by Griffith about the Civil War. The main difference is that Kino throws in David Shepard’s 1993 restoration, with different musical accompaniment and a 24-minute documentary on the making of the film. Again, the Eureka! version is BD region B.

Last month Eureka! also released a BD of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951, BD region B) in their “Masters of Cinema” program. The release also contains a DVD version. You can check it out, along with other recent releases and upcoming ones here.

Edition-Filmmuseum

This German series works with an impressive array of archives, mostly German but also Swiss and Luxembourgian. The titles that result include modern films (Straub and Huillet figure in their catalogue, as does Werner Schroeter), television, experimental cinema (they’ve done several James Benning films), documentaries, and older films. (No Blu-ray as of now. Perhaps too expensive or perhaps just the sort of restraint that dictates the white backgrounds on their covers.)

Recently Edition-Filmmuseum released a set with two films by Gerhard Lamprecht, a little-known and but in the 1920s an important director of socially conscience films set among the working class. The two-disc release includes Menschen untereinander (1926) and Unter der Laterne (1928), each with two musical tracks to choose from. The German intertitles are subtitled in English and French, and the enclosed booklet is likewise trilingual. Like all the DVDs from this company, there is no region coding.

Similarly, another new release is devoted to the early films of Michail Kalatozov, a Georgian director better known for his Soviet films of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba). One of the films here is Salt for Svanetia (1930), one of those vaguely familiar but rare titles from the history books on Soviet montage cinema. The other is Nail in the Boot (1932).

Salt for Svanetia is indeed a classic that anyone interested in silent cinema and the Soviet Montage movement should see. Set in an extremely isolated, primitive area of the Caucasus, Svanetia obviously needs a dose of Soviet modernizing. The peasants can barely subsist, and a lack of salt makes their cows and goats unable to produce milk. It’s basically an attempt to combine an ethnographic documentary with large doses of Montage-style rapid editing, canted cameras, heroic framings of people against the sky. At one point a man cutting another’s hair is framed against one of the local feudal era towers in a low angle that makes it look like something out of Alexander Nevsky (above). The film is a fascinating peep into a little-known culture.

Kalatozov stages some sketchy scenes using the locals: an avalanche which kills some men, a resulting funeral, a woman giving birth alone in the countryside. There’s no over-arching plot, though, and the director wisely sticks with showing off local customs. Naturally at the end the Soviets are building a long road to reach the area, and there’s a promise of good things to come.

Nail in the Boot is impressive for about two-thirds of its length. It stages some large battle scenes between what I take to by the Red and White Armies during the Civil War. The Whites are attacking an armored train, and a lot of explosions result. The soldiers aboard the train fire machine-guns, and Kalatozov conveys the sound by alternating single-frame shots of the muzzle of the gun with single-frame shots of the man firing it. Sound familiar? It happens two or three more times in the course of this film. Both of these films are definitely part of the Montage movement, but the director has come along so late in it that he seems to feel all the good ideas have been used, and they’re worth using again. So we get another quotation from October in a canted shot of a cannon’s wheel, and Kalatozov even steals the idea of our hero looking and feeling very small and his prosecutor becoming a looming giant, as in Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Overcoat:

We are some time into the film before we meet the hero, and I was thinking that this might be one of those Montage films with no single central figure. But well into it, the ammunition on the train is running out, and a messenger is sent to run and get help. Much of the film simply shows him running along, becoming increasingly lame as a bullet in his boot digs into his foot. Ultimately he does not reach his goal, though he tries hard. Once he is put on trial for treason, he blames the shoddy workmanship of the cobblers who made his boot badly. This seems a strange anti-climax after the exciting battle scenes earlier on, but the film actually turns out to be about Soviet workers paying attention to what they’re doing and not putting out a bad product. All the workers looking on at the trial look shame-faced at the hero’s accusation, suggesting that if a hundred percent of the workers are doing a bad job, there’s not much hope of rectifying the situation.

Both films are fascinating because they come so late in the Montage movement, which lasted from 1925 to 1933, and they are particularly valuable because it’s harder to see the films from this late period than those from the 1920s.

Both films have optional English subtitles.

By the way, Edition Filmmuseum also sells Flicker Alley films, and those in Europe and elsewhere might find them easier to order on its website.

You’re gonna need a bigger shelf

There are three notable new releases of French films. Before I get to the two epic, brick-like sets, let me mention the new Eureka! Blu-ray of Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du Nord (1981) in the “Masters of Cinema” series. Admirably, the film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. The supplements consist mainly of a thick booklet with some new essays, an interview with Rivette, and so on. You can read more about the booklet’s contents and buy the film here. Note that it is coded BD region B.

Now to the bricks.

At long last the French Impressionist director Jean Epstein is well represented on DVD. Although a few of his most famous films have appeared on video from time to time, these eight discs are a cornucopia of his work (plus a 68-minute documentary on his work by James June Schneider). They come from what are probably the best possible prints, since the set is issued by La Cinémathèque Française. Marie Epstein, who had made films herself in the late 1920s and 1930s, worked at the Cinémathèque for decades and helped preserve her brother’s work. A major retrospective of Epstein’s work ran at the Cinémathèque in April and May; the restorations in preparation for the series made possible to this DVD set. (This page links to further resources on Epstein.)

Epstein started out working for some of the large French film companies, though he mixed somewhat experimental films with more standard ones. His second surviving feature film, Cœur fidèle, is one of his most famous, and perhaps his masterpiece. A beautiful print of it is already available on a Eureka! DBD/BD combo (BD region B). There’s also a French DVD. I wrote a little about it when it made our top-ten films of 1923 list.

The big outer box of the set comes with three inner fold-out disc holders that reflect the phases of his career. The first is “Jean Epstein chez Albatros.” In 1924 Epstein joined the Russian-emigré company Albatros. Three of the four films he directed there are grouped together: Le Lion des Mogols (1924), starring Ivan Mosjoukine and Nathalie Lissenko; Le double amour (1925); and Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925). The big gap here, and indeed in the entire set, is the absence of the fourth, L’Affiche (1924), which I think is one of his best. It does survive, so I hope it will eventually appear on disc. Apart from L’Affiche, these are all big-budget productions, and Robert Macaire is a serial running 200 minutes. This set has no overlap with the Albatros set from Flicker Alley that I wrote about last year and indeed is an excellent supplement to it.

Beginning in 1926, having been successful with his big Albatros films, Epstein produced his own work under the name “Les Film Jean Epstein.” Again, there were four films, the surviving three of which are on the discs in the second folder, “Jean Epstein: Première Vague”: Mauprat (1926), La glace à trois faces (1927), and La chute de la maison Usher (1928). (The lost film is Au pays de George Sand, 1926.) La chute de la maison Usher was for a long time the only Epstein film available on 16mm prints, which didn’t really do justice to its eerie German Expressionist-influenced sets.

Gradually, however, the reputation of La glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”) has grown, and it is another highlight of Epstein’s career. It introduced a trope of modernism into the cinema, the notion of using point of view to create ambiguity. The story shows scenes concerning one man as seen through the eyes of his three lovers–each, of course, making him seem a very different person.

The other films deserve discovery as well. Le Lion des Mogols has a clever story (written by Mosjoukine) which starts out in a fictional Tibetan city where the hero, a nobleman (Mosjoukine) incurs the sultan’s wrath and flees. A cut to a ship suddenly reveals that we are in a modern world, and the film becomes a fish-out-of-water story as the hero blunders onto the set of a movie location shoot on deck (above). Intrigued, the female star of the film helps him adjust and brings him in as a leading actor. Thus our hero jumps from one genre, the fantasy Far-Eastern melodrama (familiar from various German films of the time, including the Chinese sequence from Lang’s Der müde Tod) to a modern romance. The film has the advantage of scenes in and around Albatros’s own studio:

Les Film Jean Epstein produced some major work, but it didn’t make money, and in 1928 Epstein changed course, He made 28 more films, up until his death in 1953, most of which are virtually unknown. The exceptions are some films modest, lyrical films he shot in Breton. Seven of these are presented as “Jean Epstein: Poèmes Bretons”: Finis Terrae (1928, Epstein’s last silent film), Mor’vran (1930), Les Berceaux (1931) L’Or des mers (1933), Chanson d’Ar-mor (1935), Le tempestaire (1947), and Les feux de la mer (1948). These range from 6 minutes to 82 minutes long. Most have simple plots and involve the sea.

The set has been put together so that the supplements for each film are on the end of its disc, not lumped together on a separate disc. There is also a 158-page book, not booklet, with program notes and many images: posters, designs, publicity stills, and frames. (It also has the smallest page numbers I have ever seen.) I can find no indication that the set is region-coded, but the Amazon.fr page says it’s PAL region 2. (I cannot find any reference to the set on the Cinémathèque’s own site, so I can’t confirm either way.) It does have optional English subtitles.

Since the beginning of film history, France has produced one of the world’s great national cinemas, and Jacques Tati is one of its greatest directors. On Facebook, Ingrid Hoeben, one of Tati’s devoted fans, runs a page called “I’d like to be part of the Monsieur Hulot universe, if only as a cardboard cut-out”, and I think she speaks for many of us. (She also runs a FB page on PlayTime–as she spells it. Many writers use Playtime, and I prefer Play Time.)

For those who love Tati, there is finally a new set of his complete works, restored and available in separate DVD and Blu-ray sets. The imposing big black box contains seven discs, each in its own cardboard fold-over holder, one for each of the features and one for the shorts. There are extras on each disc. The small book included with the set has a brief bio of Tati, information on the restoration of the films, and program notes.

There are various versions of some Tati films. The Mon Oncle disc includes both the French and English-dubbed versions. The Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot disc has the 1953 version and the 1978 restoration. Jour de fête, which Tati tried to make in color, has three versions: the 1949 release print, the 1964 one with selective color added, and the 1994 restoration of the color version Tati had had to abandon.

The print of Play Time, though visually beautiful, is altered by some tampering by the restorers. It originally contained passages of music over a dark screen at beginning and end. I described these moments in my essay, “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception” (published in 1988 in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis). Of the beginning I wrote:

The film begins with pre-credits music involving percussion; at a seemingly arbitrary point in this music, the bright credits shot of clouds fades suddenly in from the darkness. Already we encounter the sound track as a separate level from the image track–as something to which we should pay cloe attention in its own right. (Unfortunately, most of this music seems to have been edited out of the re-release print.) (p. 253)

(The darkness and music actually last about 10 seconds before the cloud shot.)

And the ending, which in the original has several minutes of music played over a black screen:

Play Time structures even our transference, at the end, of aesthetic perception to everyday existence, by continuing its theme music for several minutes after the images stop–so long that we are forced to get up and move about to this music. The film’s sound track becomes an accompaniment for our own actions, inviting us to perceive our surroundings as we have perceived the film. (p. 261)

(The actual timing is about one minute, though it seems longer when you’re sitting in a darkened theater and are used to leaving immediately at film’s end.)

This new disc includes the dark footage at the end and the music, but the credits for the restoration and video are superimposed throughout–quite a different experience than music accompanying darkness. The music over darkness is shortened at the beginning to about 3 seconds, with the logo of Les Films de Mon Oncle’s logo and a dedication to Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s daughter.

All these superimposed credits alters Tati’s intentions considerably. He clearly meant for that concluding music to make us almost actors in his film and to carry over its defamiliarization of the fictional world into the real world. Without it, this cannot be considered the definitive version of Play Time. It may seem a small matter, but the original decision was completely reflected Tati’s distinctive style.

Fortunately the Criterion collection’s version retains the music over black at the end, as well as a different set of supplements. Completists will need to have both.

For many, Tati’s last feature, Parade, will be new. It’s not a M. Hulot film or even really a fiction film. It was made in Sweden and consists of a variety performance by musicians, singers, a magician, and so on, all MCed by Tati in propria persona. Between other acts, Tati performs some of his most famous pantomime bits, including a remarkable scene where, as a tennis player, he mimes part of the action as if caught by a slow-motion news camera. Tati also devised some little scenes to take place among the audience, which contains some of the same sort of cardboard cut-outs that first appeared in Play Time:

Parade was shot on video during live performances, but the acts were also staged in a studio in 35mm (see bottom). That’s the source of the inconsistent visual style, though it’s less apparent on video than when projected in 35mm on a large screen.

It’s a strange but enjoyable and even complex film, if one goes into it without expecting it to be like Tati’s others.

Very few will have seen all of Tati’s shorts. These fall into three periods.

Three of them are from the mid-1930s, brief comedies ranging from 16 to 24 minutes: On demande une brute, Gai Dimanche, and Soigne ton gauche. Tati was a young music-hall performer at the time, specializing in sports pantomimes.

Second, there is L’École des facteurs (1946), a 16-minute version of of the same story that he expanded into Jour de fête a few years later. L’École des facteurs was his directorial debut, the earlier shorts having been directed by others.

And third, Tati made some shorts late in his career: Cours du soir (directed by Nicolas Ribowski), Degustation maison, and Forza Bastia (the latter two directed by Tati’s daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, who used the original family name).

The set has optional English subtitles and is BD Region B.

On early Soviet cinema and much more

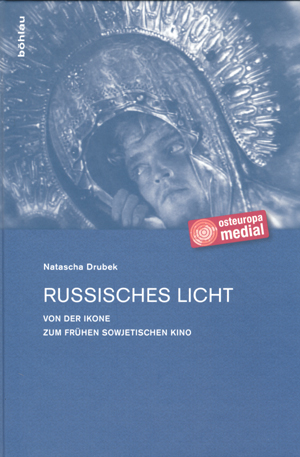

The title of Natascha Drubek’s new book, Russisches Licht: Von der Ikone zum frühen Sowjetischen Kino might seem to imply a narrow field of study. Actually, though, it ranges far, examining the introduction of electric lighting into Russia and examining what a wide range of Russian commentators wrote about light at the time. This includes, of course, the cinema, an art form both composed of light and using light during the filming.

The introductory section covers theoretical approaches to cinema, including the work of the Russian Formalists. Drubek goes on to consider factors in the early history of media in Russian and Soviet cinema, including writings on theaters and film censorship.

She then goes back to the roots of thought on light and media further back in Russian history, dealing with icons and the church, as well as the influence of icons on the Russian avant-garde of the pre-Revolutionary period. Finally she deals with cinema and in particular with the films of Evgenii Bauer.

I cannot claim to have read the book, for with my shaky knowledge of German it would be slow going. But it is an impressive achievement, and anyone interested in Russian/Soviet cinema and especially Bauer should have it. It is available online directly from the publisher.

Tati’s classic fishing routine in Parade.

You can go home again, and maybe find an old movie

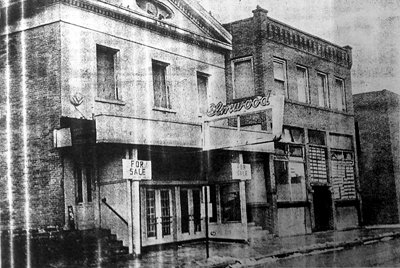

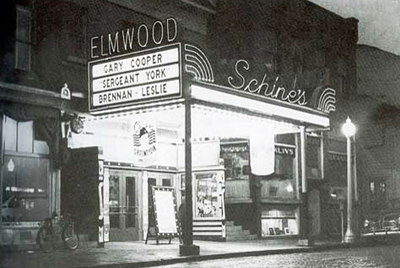

Schine’s Elmwood Theatre, Penn Yan, New York, late 1954-early 1955. Photo courtesy Yates County History Center.

DB here:

Nowadays when a theatre closes or goes digital, it says farewell by screening The Last Picture Show. That hadn’t yet become a tradition when the Elmwood Theatre of Penn Yan, New York presented Bogdanovich’s movie on its final day in November 1972.

Six people showed up.

The Elmwood had been going downhill for years. “I think the theatre building is an eyesore,” declared the chairman of the town’s Urban Renewal Agency. Once part of the powerful Schine circuit, the theatre had been acquired in the mid-1960s by the Rochester-based Panther chain, later renamed Countrywide. That firm seems to have specialized in low-budget genres and X-rated fare. In Penn Yan, the UR officer declared, most of the Elmwood’s programs were rated “restricted,” adding: “Yet it is claimed by some that it is a recreational facility for our children.” Disney films were screened at the Elmwood during those years, but local moviegoer Robert Brainard noted: “They were getting all the junk and nobody was going, not even the kids.”

When the theatre was finally closed, it stood vacant. Vandals broke the windows, and pigeons roosted inside. It had come a long way from the 1940s.

In 1974, two businessmen paid $11,000 for the building and turned it into a racquet club. That business operated for some years, but in 2003 the entire structure was demolished and a new village hall was built on the site.

By then a small three-screen mall cinema had set up business elsewhere in town. I report on a visit here.

In January, I was back in Penn Yan and naturally I sniffed around. Thanks to John H. Potter and Lisa M. Harper of the Yates County History Center, and my sisters Diane and Darlene, I came away with some precious information about the theatre I attended for the first eighteen years of my life.

I also came away with an extremely rare film.

Broadway Melodies and Cherry Blossom Queens

Captain Harry Morse ran steamboat trips on Lake Keuka. He was a legendary figure. Some said that as a boy he had caught a lake trout on his nose. (I know: How could you do that? Supposedly he bent over the side of a boat and a trout leaped up and glommed on.) More prosaically, Morse invested in Penn Yan movie houses, and in 1920 he bought the Shearman House Hotel, a popular stopover for visiting vaudevillians. Morse turned the Shearman House into a theatre.

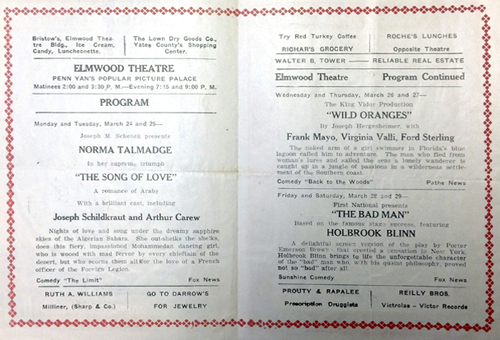

The Elmwood Theatre opened in 1921. It held at least 700 people. That’s pretty big for a town of 4500 people, but as the county seat and a business center, Penn Yan brought in farm families. Many shows were accompanied by printed programs listing coming attractions and carrying advertisements for local businesses. This one, for Song of Love, is from 1923.

Admission was typically 11 cents for matinees and 17 cents for evenings. “Specials” like Chaplin’s The Kid boosted ticket prices to 17 and 28 cents. In 1936 the Schine chain acquired the house.

The Elmwood benefited from the projection expertise of Nathaniel P. “Nat” Sackett. Nat had begun his film career in 1908 at another local movie house, vocalizing with the song slides shown between reels. He became a projectionist before joining the Elmwood in 1923. He stayed on for several decades. According to Nat, The Broadway Melody was the first sound film the Elmwood played. During World War II, he worried that too many theatres were running triple features. If the fad continued, production couldn’t keep up. For Penn Yan, one feature was good enough—especially if it was something like How Green Was My Valley or Captains of the Clouds.

A small-town movie house often became a community center. Elmwood patrons remember talent shows and holiday parties, with gifts and contests before the screenings. In 1940 a housewife attending I Love You Again could join an hour-long cooking class (with prizes) just before the show. Young women would be named Apple Blossom Queen or Cherry Blossom Queen. Halloween screenings included costume contests and of course sudden blackouts and scary sound effects. During the war, with no television or Internet, people flocked to the theatre for newsreels. Customers were steered in and out by ushers; the Elmwood employed them well into the 1950s.

“Today,” remembered Nancy Gillette, “most people cannot imagine a theatre as large as the Elmwood, which included a large balcony, being full most of the time.” By the 1930s, admission prices had come down a bit for children. Ten cents admitted Nancy to the Saturday marathon matinees: “Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Charlie Chan, the newsreel and one or two cartoons—WOW!” Lines of kids stretched down the block. In the 1950s, Diane and I were among them, watching the same cowboy heroes, along with Tarzan and Martin and Lewis.

Romances and marriages were forged at the Elmwood. In 1933, a young man taking tickets let a young woman slip out to retrieve the keys she left in her car. Over the next few days he began to drive by her house. Her cousin knew the young man and said, “Margaret, I am taking you out when Sam comes along, and I’ll stop his car and introduce you to him.” After two years of dating, Margaret and Sam married and eventually had three children. The Elmwood manager gave Sam’s mother and Margaret free passes.

Local kids like Sam found good work at the theatre. Being an usher got you free movies and a chance to flirt with the concession girls and those who came “solo.” After movies there was pizza at the Den below the theatre. But among the ushers’ tasks was the very onerous one of changing the marquee. Jerry Nissen remembered:

First you had to do layout on paper what the marquee was to say. Then, working from the last letter in the last row, fill a heavy wooden box until you get to the first letter of the first row. The solid metal letters were stored in the basement and you hauled them up to the street. Now imagine, if you will, climbing a rickety old step ladder in the rain or snow and taking down the old message and then letter by letter placing the new message on the two-sided marquee. Brrrr, it used to get very cold. Also on occasion we were the targets of some nice vocal comments and snowballs coming from the T & C Tavern across the street.

DIY movies, 1915

Wheat and Tares (Penn Yan Film Corporation, 1915).

Penn Yan had theatres before the Elmwood went up. In the ‘00s and ‘10s Nat Sackett sang at Theatorum and another theatre, both owned by the Wickham brothers. For a time Nat took over ownership of them. Before Captain Morse built the Elmwood, he was showing movies at the old Sampson legitimate theatre, as well as in the Cornwell, located above a department store. The town apparently had four screens in 1911.

With so many films playing within a couple of blocks, it’s perhaps not surprising that a local businessman decided to make one of his own.

Edward R. Ramsey owned a local paper mill and a factory that manufactured electrical cable. The story goes that when Ramsey observed that Hollywood, California was buying a great deal of his cable, he decided to try moviemaking. Ramsey sold his cable plant and started the Penn Yan Film Corporation.

After making some shorts, Ramsey tied his first feature production to a fund-raising effort by Keuka College. The college’s aim was to provide advanced education to rural students who couldn’t to go to a big university. Ramsey’s film would demonstrate the virtues of going to college. All the talent was local, including the cameraman, who was Ramsey’s brother. From outside, Broadway actor and occasional film director George E. LeSoir was recruited to direct the show.

Shot in the summer of 1915, Wheat and Tares traces the story of two young men. Both Jim Watson and Will Beggs read dime novels, but Jim is encouraged by Alice Corwin, daughter of a Penn Yan businessman, to improve himself. Uplifted by literature, Jim leaves the farm for Keuka College. There he learns enough to become an auto salesman. At the same time, Will (who stuck to pulp fiction) falls in with a gang of layabouts and petty crooks. Their fates converge when Jim discovers oil. A crooked realtor hires Will to put Jim out of action long enough for the site option to expire. But Alice renews the option, and Jim’s family becomes rich. Meanwhile, Will’s life of crime catches up with him, and he is sentenced to a prison road gang. Jim and Alice, now married and with a child, stop when they see Will on the road. Jim vows to help his old friend go straight.

Despite its opening-night success at the Sampson playhouse, Wheat and Tares didn’t have legs. Keuka College closed in fall 1915 and didn’t reopen until 1921. Ed Ramsey died in an auto accident in June 1916. The film may have gotten no distribution outside the region. Stored in the Ramsey home, it was discovered decades later when the house was prepared for demolition. The film was transferred to safety stock and eventually to DVD. That’s the version I have seen.

In the moralizing manner of its day, the full title, Wheat and Tares: A Story of Two Boys who Tackle Life on Diverging Lines, contrasts the life paths of its two protagonists. A tare is a form of weed that infects a field of healthy wheat. Tares in their early stages look very much like wheat, so the metaphor implies that one must wait to see if a young man will turn out well or not. (The Biblical reference is a parable by Jesus, at Matthew 13: 34-35.)

The surviving copy of Wheat and Tares has lost its opening reel. What remains is a fairly ordinary 1915 film. The parallel stories of Jim and Will aren’t developed in tandem; we lose Will for most of the film. A great deal of the second reel is occupied with rich boys hazing Jim at college, which does teach him the manly art of self-defense, but to no special point: he doesn’t get to use his boxing skills later. Another undeveloped plot line involves a movie company filming in the vicinity.

Theme and plot don’t match very well. If you are trying to convince people that going to college will better them, why show your hero succeeding by stumbling onto an oil gusher? Jim would have been just as likely to find oil if he had stayed a sodbuster. The climax is particularly feeble: While Jim is recovering from the beating given him by Will and another thug, it’s Alice who saves the day. She does this not through extraordinary courage or sacrifice, but simply by having her father write a check that renews the option. The realtor, a very passive villain, does nothing, underhanded or otherwise, to block her maneuver.

Stylistically, you can hardly expect The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, or Regeneration from this tiny Finger Lakes company. In most respects, the film resembles standard films of the period. Some filmmakers were exploiting the sort of crosscutting popularized by Griffith, but Ramsey and Le Soir take almost no advantage of it. There’s no fast cutting to pick up the pace. Most scenes are played in single shots, with close-ups used only to emphasize details, such as a deck of cards, that can’t be easily seen in the master framing. The closest shots of the principals occur during a phone conversation–again, a convention of the period.

Nor does the film exploit the sort of complicated staging we find in tableau cinema. There is one rather well-handled crowd shot, as well as a smooth track-in and-out when Will recruits a one-eyed thug to help him ambush Jim. Simple camera movements like this were by 1915 considered a fairly normal option.

There is an ambitious matte effect when Jim and his college chum Phil visit the movies, but even this fairly common device is somewhat bungled when the boys’ bodies become ghostly by crossing into the matte area.

Although Wheat and Tares exemplifies ordinary cinema of that day, like most films of the first great era of cinema it’s a pleasure to watch. Shooting on location yields spontaneous beauties. At one point Jim rides home on the trolley. In a film utterly lacking in calculated lighting effects, we get a lovely image. Not only do we see the town and wagons pass through windows, but after Will and his partner jump aboard, accidents of backlighting turn them into sinister shapes.

Trolley shots are among the glories of 1910s cinema; I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bad one.

Penn Yan must have been gorgeous then, with the main streets lined with elms.

The trees were felled by Dutch elm disease and other factors, I’m told.

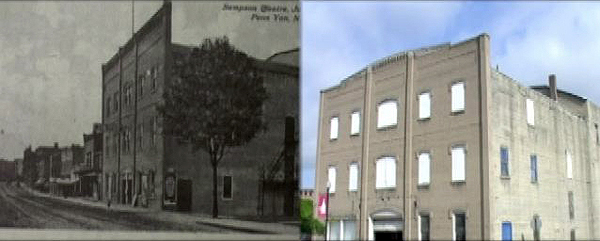

As with any film shot in surroundings that you know, part of the fun comes in spotting familiar locales. John Creamer’s introduction juxtaposes some town landmarks. Here’s the Sampson Theatre, then and now.

Two locations that my sisters discovered pop up late in the film. For a chase, the camera was set up just around the corner from Ramsey’s house.

Ramsey’s house was demolished to add a building and a parking lot to the local hospital, but from that vantage point, we found the source of another shot. The camera was apparently set up in front of Ramsey’s home to frame Jim and Alice and their child in their chauffeur-driven Maxwell. The sidewalk in the foreground is gone, but the background area, including the fire hydrant, has stayed surprisingly constant.

And whatever the faults of Wheat and Tares, watching it gives you a glimpse of the entrance to Captain Morse’s Sampson Theatre (below). In the summer of 1915, Charlie Chaplin had sauntered into my home town. The show starts on the sidewalk, as they used to say.

I’m grateful to John and Lisa of the Yates County History Center for all their suggestions, for access to their files, and for the exterior photo up top and the shot of the Elmwood interior. You can read the local newspaper’s announcement of the Wheat and Tares premiere, with a teaser synopsis, here. Thanks also, of course, to Darlene and Diane. The picture of Penn Yan’s town hall was supplied by Darlene, whose photography site is here.

A DVD copy of Wheat and Tares is available for $15 from the Yates County History Center. You can email Lisa M. Harper, ycghs at yatespastdotorg, or call (315) 536-7318. Credit cards accepted.

The indispensable guide to the theatres in this region is Norman O. Keim’s Our Movie Houses: A History of Film and Cinematic Innovation in Central New York (University of Syracuse Press, 2008). You can read about the Schine chain there, or here.

Wheat and Tares is a prime example of an orphan film. Dan Streible of NYU is a moving force behind retrieving and restoring these elusive items, and a new Orphan Film Symposium is coming up in Amsterdam.

Wheat and Tares (1915). The sign on Charlie’s crotch reads” “Meet Me at the Sampson Program.”