Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

16, still super

From Lost & Found Film Club.

DB back:

While I was semi-snowbound in Evanston, IL, messages kept rolling in. Many of them were responding to my account of surrendering my 16mm movies and gear. That post’s whiff of nostalgia was caught by Gary Meyer, co-director of the Telluride Film Festival.

Don’t get me started on 16mm memories. I started showing movies in 8mm at about ten years old and by thirteen I had two for changeovers on silent classics rented from Cooper Films in Chicago. For about $2 I got a full feature and short including postage. Using my parents’ record collection I could score the films. . . .

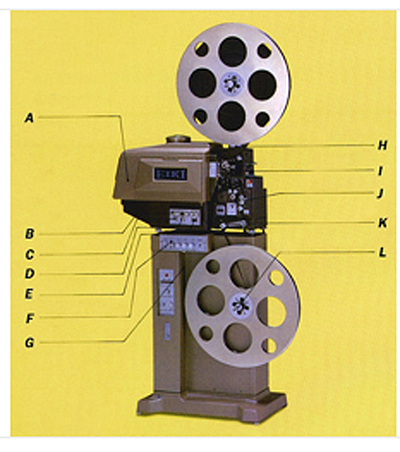

Graduated to 16mm in high school when a local church and the library each offered use of their projectors and I started collecting prints seriously. In college I got a job in the media center showing films, cleaning prints and projectors. When the department decided to buy Bell & Howell Auto-Shreds, they sold off the old projectors for $50. I knew each machine intimately and selected the quietest, gentlest RCA 400 which I still have in a booth in my basement. One of my favorite projectors.

With 16mm projectors I have shown movies on garage doors from my apartment, in a barn, an orchard or two, and most famously on clouds, which resulted in the police department getting many phone calls about aliens.

Gary reports that his former venue, the Balboa Theatre, has given its theatrical Eiki projector to the San Francisco State University film department, but it can be borrowed back if ever needed. A more acute sense of the passing of an era was reported by program curator and Czech arts consultant Irena Kovarova:

One of the sad moments in my film history was being invited to the Czech Embassy in Washington, DC to visit a room of 16mm film piles. I was asked to pick and choose which ones should be saved and which would be chucked away (the majority). It was a collection of films that the Embassy inherited from the Communist-era offices when the staff was shipped films for their entertainment (Czech popular comedies) and of course tons of “travel” and “propaganda” stuff. It was impossible to know what was really there and a lot was mediocre, but still such a sad thing that no one could really dig in and explore.

Secrets of the Incas, and non-Incas

Projection booth, Cleveland Cinematheque.

But there was good news too. In the course of that entry, I said that 16 was “nearly dead” as an exhibition format. Trust this blog’s alert readers to give a more upbeat emphasis and offer some weighty counterexamples. Don’t hesitate to use the hyperlinks!

I was confirmed in my belief that archives will keep the format going. I hear from our old friend Antti Alanen of the National Audiovisual Archive of Finland, that 16 flourishes in Helsinki.

We still keep screening 16mm regularly at Cinema Orion, and for the moment print access is still good. We recently showed three programs of Stan Brakhage movies (from Canyon Cinema) and one programme of Rose Lowder movies (from Light Cone of Paris), all in the original format of 16mm, all prints and colours perfect.

I haven’t seen Brakhage on DVD, but those who have remarked that it is not the same thing. There is something about the special sensuality of 16mm which is essential to the Stan Brakhage experience. All of those films fill up the senses.

Besides Canyon Cinema and Light Cone, LUX in London still seems to be well-stocked with good 16mm prints in commercial distribution.

Bracing news. Antti mentions as well that he used to be able to access 16mm films made for the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, but now the agency has realized that the prints are irreplaceable and provide digibeta copies instead. The loss for showing is a gain for preservation.

I indicated as well that colleges, universities, and museums will probably maintain 16mm prints and showings. My correspondents have confirmed it, and offer some ripe local detail. Tracy Stephenson of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells me that they have shown films since the 1930s and may be the only venue in Houston that still screens 16. They have a program of jazz shorts coming up in June.

Here’s John Ewing of Cleveland:

I still show 16mm on occasion (and two-projector 16mm at that) at both of my venues: the Cleveland Cinematheque and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In fact, I just ran the 16mm program from the 50th Ann arbor Film Festival tour last Thursday night at the Cinematheque. Last time I showed 16 at the art museum was in December when we screened an IB Tech print of Secret of the Incas, from the Academy Film Archive.

From the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Brian Hearn writes:

We are pretty serious about 16mm and maintain a modest collection of about 500 prints, ranging from Lumiere Brothers shorts to studio features to avant-garde to educational films to 70s exploitation trailers. As the film medium dematerializes it makes me appreciate our collection even more, vinegar and pink fading prints included!

Calling a collection of 500 titles modest makes me grin (in envy). On the university side, Jon Vickers supplies other breathtaking information:

Indiana University Cinema programs from the University’s 16mm collection on a regular basis, with 16mm screenings at least once each month. In the IU Libraries Film Archives, there are over 80,000 items, the majority being 16mm. Within that collection is Lilly Library’s David Bradley Collection, spanning the history of cinema in the US and Europe, including classic, obscure, and some unique titles. We dedicate a series each semester to the holdings within the Bradley Collection (programmed by Film and Media Studies grad students), as well as program from the educational/non-theatrical collections and holdings.

We can’t imagine a day when we will stop screening 16mm.

With that treasure house, I can see why! Pablo Kjolseth of the University of Colorado at Boulder also defends the format resolutely. Pablo has written one of the most fiery and persuasive polemics on digital cinema. Not only does his program have an extensive library, but they are still actively collecting in 16. Moreover, as home to the annual Brakhage Center for Media Arts symposium on experimental film (coming up next week), Boulder’s campus relies constantly on 16.

Hipsters, nostalgics, and toddlers

Eiki EX-9100 Professional 16mm Sound Optical/Magnetic projector with 2000-watt lamp. Currently available on eBay for $8,500.

Perhaps the most cheering news comes from those enterprising programmers of films for public venues, both for-profit and not-. Barak Epstein of the Texas Theater uses Kodak Pageants (of my fond memory) with manual changeovers and a manual audio fader. Pittsburgh Filmmmakers, writes Gary Kaboly, uses its Kinoton and Eiki machines every couple of months. He adds:

Throwing around the idea of a “classic 16mm experimental” series in the fall. Young Hipsters see attending a 16mm show as an “event.” Old Hipsters always describe what an Art House was “back in the day.”

The Cinefamily venue of LA has established itself as home to what the local paper called “pathologically idiosyncratic programming,” and 16 adds sharp spice to the mix. Here’s Hadrian Belove, the Head Programmer, on his personal quest and the formation of the Lost & Found Film Club:

I’m definitely of an age that would be post-16mm collecting, but still got hooked. One of the great appeals of 16mm for me is it feels like the final frontier for discovering true rarities. . . . It’s kind of the ultimate format for a “digger.” Finding Christian experimental films, industrial films, student films, and copies of TV movies, episodes, and even theatrical features that simply never made it to any form of video is de rigueur.

Nothing gives me more pleasure as an explorer than trolling eBay for 16mm.

I began showing things I would buy after hours to the staff here at Cinefamily, and hadn’t even considered it as a public show. Over time, some of the “kids” on the staff started buying their own 16mm ephemera, and finally proposed taking our private show public. I thought what the hell, cost is low, and we were doing it anyway. I gave them a terrible time slot I wasn’t using (10:30 on a Wednesday).

They launched this:

https://www.facebook.com/LostFoundFilmClub

Anyway, the first show had 100 people, even at 10:30 on a Wed night. Maybe it’s those grilled cheese sandwiches!

Finally, I had noted that FOOFs (Fans of Old Films) had a noble tradition of gathering in annual conventions. Jessica Rosner, film scout extraordinaire, writes of screenings at the upcoming Syracuse Cinefest: “The majority of films will STILL be in 16mm and they will be films that are rarely available to be seen any other way.”

A further note from Pablo Kjolseth brings things back to Gary Meyer’s childhood and the FOOF in us all. Pablo hosts summer screenings in his back yard.

My Eiki Xenon projector shoots through a guest-room window to the screen in the backyard – transforming the guest room into a “projection booth” of sorts. The next [picture] is a nice ominous shot of Darth under stormy skies. . . . Although I’ve played around with some digital screenings, everyone prefers the 16mm shows. And this even though I don’t do reel-changes or employ a take-up tower – thus having small intermissions between each reel change. These intermissions are quite popular, as it allows folks time to refill their drinks, go to the bathroom, and comment on what they’ve seen so far.

As many as 60 people might show up for any screening. As the children in the neighborhood are always entranced by the projector, I try to make sure to have a couple family-friendly screenings every summer. My neighbors are great: they’ve even tolerated backyard screenings of such titles as DAWN OF THE DEAD and THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE – admittedly poor choices, given that in the summer heat most people sleep with their windows open and late at night they might not appreciate all the screaming and, well, chainsaws. But, so far, no complaints!

None from my end, either. Is it just me, or does Darth look more menacing here than in any other setting?

After reading these communiqués, two thoughts. First, a great many programmers are working very hard to track down and screen unusual items for their audiences. These folks and their peers are committed to exploring cinema along routes that bypass the multiplex. Who wouldn’t rather watch Secret of the Incas than, say, The Last Exorcism Part II?

My second thought comes with a pang. Was I wise to clear out my 16 collection? Our department and other collectors benefit, but still… A basement will dry out, but films that are gone are gone.

Thanks to all who wrote me, and to the Art House Convergence list serve for its stimulating conversations.

Once more, Mad City movies

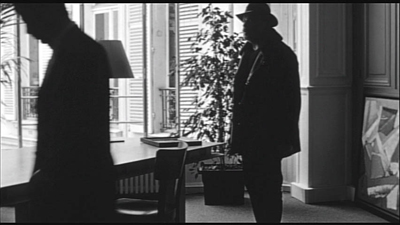

Night and the City.

DB here:

It’s been a busy time in Madison, at least for me. KT is in Egypt, peering at shards of statues and documenting earlier Armana excavations. I’m at home, having missed the Hong Kong International Film Festival (doctor’s orders) and wistfully wishing I’d been there for the tribute to Peter Chan Ho-sun (check out Fred Ambroisine’s interview at Twitchfilm) and a chance to see—Don’t say whoa!—Keanu Reeves, who was there with Side by Side, his new film on digital cinema (snif).

Instead of traveling, I’ve been doing other stuff. There were, and still are, last-minute checks and fixups on the new edition of Film Art. I went to some movies–Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, The Hunger Games, The Raid: Redemption, Carnage, 21 Jump Street—as well as screenings at our Cinematheque. Late at night I’ve been watching 1940s films for a long-range project. Most frantically, I’ve been working on a little e-book to be finished, I hope, in three weeks. It will be available on this site, ludicrously cheap, you will want one for sure, I bet, well, why not? More about it later.

In the meantime, Madison has hosted some remarkable visits. I’ve already mentioned Lynda Barry’s delightful presentation of Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. I must also mention two other dignitaries that illuminated our lives this spring.

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

More recently, we were visited by Schawn Belston, an old friend who’s Senior Vice-President of Library and Technical Services at Twentieth Century Fox. Our Cinematheque is running a string of Fox restorations, and Schawn brought along a stunning print of the lustrous noir classic Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950).

There’s a nifty story behind that print. Schawn and archivist (and Badger) Mike Pogorzelski discovered an original camera negative in the Movietone News vault in Ogdensburg, Utah. When they struck our print (directly from the neg) and showed it to Dassin a few years ago, he wept with pleasure.

Schawn found another version of unknown provenance. On the basis of the first reel, which he screened for us, this seems to be a British version, with a different voice-over narrator, varying footage and cutting patterns, and a lighter, more romantic score. As Schawn pointed out, this plays more slowly and is more of a melodrama than a thriller; it also makes the Richard Widmark character a little more sympathetic, I thought. Nobody has yet discovered why this version was made.

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

*Lots of filmmakers are still finishing on film, but the plan is to make no prints available to US theatres after 2012. About 300 prints of current titles will still be made for the world market.

*Both Fuji and Kodak are still making film stock, even new emulsions, but the decline in usage will raise prices. A 35mm print now costs $4000, a 70mm print runs $35,000 and up.

*Storage problems are immense. The studio wants to save all the raw footage; in the case of Titanic, that comes to 2.5 million feet. Which version of the film has priority for the shelf? Typically, the longest cut, often the first preview print.

*All studios are still making 35mm negatives for preservation, typically from 4K scans. Ironically, their soundtracks, usually magnetic, can’t match the uncompressed sound of the files on a Digital Cinema Package (DCP).

*”Film is the most stable medium, but the preservation practices for it are the most vulnerable.”

*Nearly all film restoration is digital now, so the best way to show the results is probably digitally. That also makes for standardized presentation and less wear and tear on physical copies.

*Most classic films in a studio library are not available on DCP. If an archive or cinematheque or theatre wants one, there are ways to make on-demand DCPs. But it’s not cheap. A 2K scan runs $40,000; a 4K scan, somewhat more. Schawn opts for 4K because a digital version should be the best possible. It might be the last chance to make one!

*Films stored on digital files must be migrated frequently. Sometimes that’s done through “robotic tape recycling.” But there are problems with the constantly changing formats and standards. The Movietone News library was originally digitized to ID-1, a high-end broadcast tape format from the mid-1990s, so that material will need to be copied to something more current.

*Schawn believes that objective criteria about color, contrast, and other properties need to be balanced with concern for the audience’s experience. By today’s standards, original copies of Gone with the Wind and The Gang’s All Here look surprisingly muted. But to audiences of the time, they probably looked splashy, because viewers saw so few color movies. Restorers and modern viewers have to recognize that perception of a film’s look is comparative, and the terms of the comparison can change.

Schawn’s point was made after his visit with our Cinematheque show of the restored copy of Chad Hanna (Henry King, 1940). For a Technicolor film, it had a surprising amount of solid black, and not just in night scenes. We’re used to “seeing into the dark” via today’s film stocks and digital video formats, and we probably identify Technicolor with the candy-box palette of MGM musicals on DVD. We sometimes forget that chiaroscuro was no less a resource of color film of the 1940s than of black-and-white shooting of the period. A leisurely, charmingly unfocused story with a radiant Linda Darnell (she lights up the dark) and Fonda at his most homespun, Chad Hanna was good in itself and an education in color style circa 1940.

Schawn’s visit, like Tony’s, was informative and plenty of fun. We want to see both again soon.

Up next, as Robert Osborne would say: Some picks for the Wisconsin Film Festival, which launches Wednesday.

Thanks to Jim Healy, Cinematheque programmer, for arranging Schawn’s visit and the Fox retrospective.

Chad Hanna. Not, emphatically not, from 35mm; from Fox Movie Channel.

Pandora’s digital box: From films to files

“Up ahead was Pandora. You grew up hearing about it, but I never figured I’d be going there.”

DB here:

Actually it wasn’t originally a box but a jug. And it might not have been filled with all the world’s misfortunes; it might have housed all the virtues. In Greek mythology, the gods create her as the first woman, sort of the ancient Eve. We get our standard idea of her story not from the ancient world, however, but from Erasmus. In 1508 he wrote of her as the most favored maiden, granted beauty, intelligence, and eloquence. Hence one interpretation of her name: “all-gifted.” But to Prometheus she brought a box carrying, Erasmus said, “every kind of calamity.” Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus accepted the box, and either he or Pandora opened it, “so that all the evils flew out.” All that remained inside was Hope. (Don’t think there isn’t a lot of dispute about why hope was cooped up with all those evils.)

The idea of Pandora’s box spread throughout Western culture to denote any imprudent unleashing of a multitude of unhappy consequences. It’s long been associated with an image of an attractive but destructive woman, and we don’t lack examples in films from Pabst to Lewin. But there’s another interpretation of the maiden’s name: not “all-gifted” but “all-giver.” According to this line, Pandora is a kind of earth goddess. In one Greek text she is called “the earth, because she bestows all things necessary for life.”

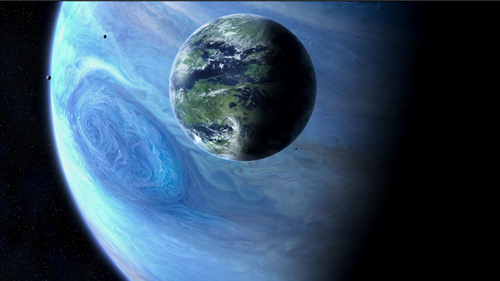

The less-known interpretation seems to dominate in Avatar. Pandora, a moon of the huge planet Polyphemus, is a lush ecosystem in which the humanoid Na’vi live in harmony with the vegetation and the lower animals they tame or hunt. Nourished by a massive tree (they are the ultimate tree-huggers), they have a balanced tribal-clan economy. Their spiritual harmony is encapsulated in the beautiful huntress Neytiri. As the mate for the first Sky-Person-turned-Na’vi, Avatar Jake, she’s also an interplanetary Eve. And by joining the Na’vi on Pandora, Jake does find hope.

The irony of a super-sophisticated technology carrying a modern man to a primal state goes back at least as far as Wells’ Time Machine. But the motif has a special punch in the context of the Great Digital Changeover. Digital projection promises to carry the essence of cinema to us: the movie freed from its material confines. Dirty, scratched, and faded film coiled onto warped reels, varying unpredictably from show to show (new dust, new splices) is now shucked off like a husk. Now images and sounds supposedly bloom in all their purity. The movie emerges butterfly-like, leaving the marks of dirty machines and human toil behind. As Jake returns to Eden, so does cinema.

Avatar or atavism?

Kristin suggested the title for this series of blog entries, and I liked its punning side. For one thing, Avatar was a turning point in digital projection. 3D, as we now know, was the Trojan Horse that gave exhibitors a rationale to convert to digital. Avatar, an overwhelming merger of digital filmmaking (halfway between cartoon and live-action) and 3D digital projection, fulfilled the promise of the mid-2000s hits that had hinted at the rewards of this format.

With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, Avatar convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. True, theatre chains also benefited from JP Morgan’s timely infusion of about half a billion dollars in financing in November 2009, a month before the film’s release. Still, this movie that criticized technology’s war on nature accelerated the appearance of a new technology.

Throughout this series, I’ve tried to bring historical analysis to bear on the nature of the change. I’ve also tried not to prejudge what I found, and I’ve presented things as neutrally as I could. But I find it hard to deny that the digital changeover has hurt many things I care about.

The more obvious side of my title’s pun was to suggest that digital projection released a lot of problems, which I’ve traced in earlier entries. From multiplexes to art houses, from festivals to archives, the new technical standards and business policies threaten film culture as we’ve known it. Hollywood distribution companies have gained more power, local exhibitors have lost some control, and the range of films that find theatrical screening is likely to shrink. Movies, whether made on film or digital platforms, have fewer chances of surviving for future viewers. In our transition from packaged-media technology to pay-for-service technology, parts of our film heritage that are already peripheral—current foreign-language films, experimental cinema, topical and personal documentaries, classic cinema that can’t be packaged as an Event—may move even further to the margins.

Moreover, as many as eight thousand of America’s forty thousand screens may close. Their owners will not be able to afford the conversion to digital. Creative destruction, some will call it, playing down the intangible assets that community cinemas offer. But there’s also the obsolescence issue. Equipment installed today and paid for tomorrow may well turn moribund the day after tomorrow. Only the permanently well-funded can keep up with the digital churn. Perhaps unit prices will fall, or satellite and internet transmission will streamline things, but those too will cost money. In any event, there’s no reason to think that the major distributors and the internet service providers will be feeling generous to small venues.

Did this Pandora’s box leave any reason to be optimistic? I haven’t any tidy conclusions to offer. Some criticisms of digital projection seem to me mistaken, just as some praise of it seems to me hype or wishful thinking. In surrendering argument to scattered observations, this final entry in our series is just a series of notes on my thinking right now.

What you mean, celluloid?

First, let’s go fussbudget. It’s not digital projection vs. celluloid projection. 35mm motion picture release prints haven’t had a celluloid base for about fifteen years. Release prints are on mylar, a polyester-based medium.

Mylar was originally used for audio tape and other plastic products. For release prints of movies, it’s thinner than acetate but it’s a lot tougher. If it gets jammed up in a projector, it’s more likely to break the equipment than be torn up. It’s also more heat-resistant, and so able to take the intensity of the Xenon lamps that became common in multiplexes. (Many changes in projection technology were driven by the rise of multiplexes, which demanded that one operator, or even unskilled staff, could handle several screens.)

Projectionists sometimes complain that mylar images aren’t as good as acetate ones. In the 1940s and 1950s, they complained about acetate too, saying that nitrate was sharper and easier to focus. In the 2000s they complained about digital intermediates too. Mostly, I tend to trust projectionists’ complaints.

But acetate-based film stock is still used in shooting films, so I suppose digital vs. celluloid captures the difference if you’re talking about production. Even then, though, there’s a more radical difference. A strip of film stock creates a tangible thing, which exists like other objects in our world. “Digital,” at first referring to another sort of thing (images and sounds on tape or disk), now refers to a non-thing, an abstract configuration of ones and zeroes existing in that intangible entity we call, for simple analogy, a file.

George Dyson: “A Pixar movie is just a very large number, sitting idle on a disc.”

Big and gregarious

Sometimes discussion of the digital revolution gets entangled in irrelevant worries.

First pseudo-worry: “Movies should be seen BIG.” True, scale matters a lot. But (a) many people sit too far back to enjoy the big picture; and (b) in many theatres, 35mm film is projected on a very small screen. Conversely, nothing prevents digital projection from being big, especially once 4K becomes common. Indeed, one thing that delayed the finalizing of a standard was the insistence that so-called 1.3K wasn’t good enough for big-screen theatrical presentation. (At least in Europe and North America: 1.3K took hold in China, India, and elsewhere, as well as on smaller or more specialized screens here.)

Second pseudo-worry: “Movies are a social experience.” For some (not me), the communal experience is valuable. But nothing prevents digital screenings from being rapturous spiritual transfigurations or frenzied bacchanals. More likely, they will be just the sort of communal experiences they are now, with the usual chatting, texting, horseplay, etc.

Of course, image quality and the historical sources and consequences of digital projection are something else again.

Irresolution

It’s a good thing the pros kept pushing. Had filmmakers and cinephiles welcomed the earliest digital systems, we might have something worse. Here’s George Lucas in 2005, talking less about photographic quality than the idea of the sanitary image.

The quality [of digital projection] is so much better. . . . You don’t get weave, you don’t get scratchy prints, you don’t get faded prints, you don’t get tears. . . The technology is definitely there and we projected it. I think it is very hard to tell a film that is projected digitally from a film that is projected on film.

And he’s referring to the 1280-line format in which Star Wars Episode I was projected in 1999.

Probably the widespread skepticism from directors and cinematographers helped push the standard to 2K. (So did the adoption of the Digital Intermediate.) Optimistic observers in the mid-2000s expected the major studios to make 4K the standard right away. Given the constraints of storage at that time, the 2K decision might be justified. But like the 24 frames-per-second frame rate of sound cinema, it was a concession to the just-good-enough camp.

At the same time, George seems to grant that progress will be needed in the area of resolution.

You’ve got to think of this [our current situation] as the movie business in 1901. Go back and look at the films made in 1901, and say, “Gee, they had a long way to go in terms of resolution. . . .”

Actually, in films preserved in good state from 1901, the resolution looks just fine—better than most of what we see at the multiplex today, on film or on digital.

The invisible revolution

Speaking of sound cinema: Is the changeover to talkies the best analogy for what we’re seeing now? Mostly yes, because of the sweeping nature of the transformation. No technological development since 1930 has demanded such a top-to-bottom overhaul of theatres. Assuming a modest $75,000 cost for upgrading a single auditorium, the digital conversion of US screens has cost $1.5 billion.

In an important respect, though, the analogy to sound doesn’t hold good. When people went to talkies, they knew that something new had been added. The same thing happened with color and widescreen. And surely many customers noticed multi-track sound systems. But what moviegoers notice that a theatre is digital rather than analog? Many probably assume that movies come on DVDs or, as one ordinary viewer put it to me, “film tapes.” Anyhow, why should they care?

There was a debate during the 2000s that audiences would pay more for a ticket to a digital screen. But that notion was abandoned. People aren’t that easy to sucker. So we’re back with 3D as the killer app, the justification for an upcharge. Whether 3D survives, dominates, or vanishes isn’t really the point. It’s served its purpose as the wedge into digital installation.

By the way, according to one industry leader, 2D ticket prices are likely to go up this year while 3D prices drop. Is this flattening of the price differential a strategy to get more people to support a fading format?

Mommy, when a pixel dies, does it go to heaven?

Digital was sold to the creative community in part by claiming that at last the filmmaker’s vision would be respected. Every screening would present the film in all its purity, just as the director, cinematographer et al. wanted it to be seen.

Last week I went to see Chronicle with my pal Jim Healy. The projector wasn’t perpendicular to the screen, so there was noticeable keystoning. The masking was set wrong, blocking off about a seventh of the picture area. And two little pink pixels were glowing in the middle of the northwest quadrant throughout the movie. I’m assuming that Chronicle’s director didn’t mandate these variants on his “vision.”

Jim went out to notify the staff, and two cadets came down to fiddle with the masking. The movie had already been playing in that house for several days. Maybe the masking hadn’t been changed for months? And of course the projector couldn’t be realigned on the fly. As for those pixels: There’s nothing to be done except buy a new piece of gear. Chapin Cutler of Boston Light & Sound tells me that replacing the projector’s light engine runs around $12,000. At that price, there may be a lot of dead pixels hanging around a theatre near you.

Video to the max

Not so long ago, the difference was pitched as film versus video. That was the era of movies like The Celebration and Chuck and Buck. Then came high-definition video, which was still video but looking somewhat better (though not like film). But somehow, as if by magic, very-high-definition video, with some ability to mimic photochemical imagery, became digital cinema, or simply digital.

We have to follow that usage if we want to pinpoint what we’re talking about at this point in history. But damn it, let’s remember: We are still talking about video.

The Film Look

Ever since the days of “film vs. video,” we’ve been talking about the “film look.” What is it?

I’m far from offering a good definition. There are many film looks. You have orthochromatic and panchromatic black-and-white, nitrate vs. acetate vs. mylar, two-color and three-color Technicolor, Eastman vs. Fuji, and so on. But let’s stick just with projection. Is there a general quality of film projection that differentiates it from digital displays?

Some argue that flicker and the slight weaving of film in the projector are characteristic of the medium. Others point to qualities specific to photochemistry. Film has a greater color range than digital: billions of color shades rather than millions. Resolution is also different, although there’s a lot of disagreement about how different. A 35mm color negative film is said to approximate about 7000 lines of resolution, but by the time a color print is made, the display yields about 5000 lines—still a bit ahead of 4K digital. But each format has some blind spots. There’s a story that the 70mm camera negative of The Sound of Music recorded a wayward hair sticking straight out on the top of Julie Andrew’s head. It wasn’t visible in release prints of the day, but a 4K scan of the negative revealed it.

Film fans point to the characteristic film shimmer, the sense that even static objects have a little bit of life to them. Roger Ebert writes:

Film carries more color and tone gradations than the eye can perceive. It has characteristics such as a nearly imperceptible jiggle that I suspect makes deep areas of my brain more active in interpreting it. Those characteristics somehow make the movie seem to be going on instead of simply existing.

Watch fluffy clouds or a distant forest in a digital display, and you’ll see them hang there, dead as a postcard vista. In a film, clouds and trees pulsate and shift a little. Partly the film is capturing very slight movements of them in air, or the movement of light and air around them. In addition, the film itself endows them with that “nearly imperceptible jiggle” that our visual system detects.

How? Brian McKernan points out that the fixed array of pixels in a digital camera or projector creates a stable grid of image sites. But the image sites on a film frame are the sub-microscopic crystals embedded in the emulsion and activated by exposure to light. Those crystals are scattered densely throughout the film strip at random, and their arrangement varies from frame to frame. So the finest patterns of light registration tremble ever so slightly in the course of time, creating a soft pictorial vibrato.

Another source of the film look was suggested to me by Jeff Roth, Senior Vice-President of Post-Production at Focus Features. Jeff notes that a video chip is a flat surface, with the pixels activated by light patterns across the grid. (We forget that in the earliest stages, “digital” image capture is “analog”—that is, photographic—before it gets quantized and then digitized.) But a film strip has volume. It seems very thin to us, but light waves find a lot to explore in there. Light penetrates different layers of the emulsion: blue on top, then a yellow filter, then green, then red. The light rays leave traces of their passage through the layers. Joao S. de Oliveira puts it more laconically:

There is a certain aura in film that cannot exist in a digital image. . . . From the capture of a latent image, the micro-imperfections created by light on a perfect crystalline structure—a very three-dimensional process—to its conversion into a visible and permanent artefact, the latitude and resolution of film are incomparable to any other process available today to register moving images.

For example, shadows and highlights are captured “deeply.” Bright areas move into shadow gracefully. Similarly, film is far more tolerant of overexposure than digital recording is; even blown-out areas of the negative can be recovered. (In still photography, darkroom technique allows you to “burn in” an overexposed area.) The blown-out elements are still there, but in digital they’re gone forever.

Film shown on a projector maintains the film look captured on the stock: You’re just shining a light through it. We’ve all heard stories, however, of those DVD transfers that buff the image to enamel brightness and then use a software program to add grain. One archivist tells me of an early digital transfer of Sunset Blvd. that looked like it had been shot for HDTV.

But today carefully done digital transfers can preserve some of the film look. When my local theatres were transitioning, I saw Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy first on film, then on digital, and then again on film. Although the digital looked a little harder, I was surprised how much graininess it preserved. So it seems to me that some qualities of the film look can be retained in digital transfers.

Marching orders

George Lucas, at the 2005 annual convention and trade show of the National Association of Theatre Owners: “I’m sort of the digital penny that shows up every year to say, ‘Why haven’t you got these digital theatres yet?'” (Variety 17 March 2005).

“His point to theater owners was that 3D, which can bring in new audiences and justify higher ticket prices, is only possible after they make the switch to digital projection” (Hollywood Reporter 10 February 2012).

Premonitions

In summer of 1999, Godfrey Cheshire published a two-part article, “The Death of Film/ The Decay of Cinema.” It’s proven remarkably far-sighted.

He predicted that within a decade your multiplex theatre would contain “a glorified version of a home video projection system.” He predicted that the rate of adoption would be held back by costs. He predicted that the changeover would mostly benefit the major distributors, and that exhibitors would have to raise ticket and concession prices to cover investments. He predicted what is now called “alternative content”—sports, concerts, highbrow drama, live events—and correctly identified it as television outside the home. He predicted the preshow attractions that advertise not only products but TV shows and pop music. He predicted what is being seriously discussed in industry circles now: letting viewers snap open their “second screen” and call, text, check email, and surf the net during the show. And he predicted that distractions and bad manners in movie theatres would drive away viewers who want to pay attention.

People who want to watch serious movies that require concentration will do so at home, or perhaps in small, specialty theatres. People who want to hoot, holler, flip the bird and otherwise have a fun communal experience . . . will head down to the local enormoplex.

Godfrey goes on to make provocative points about the effects of digital technology on how movies are made as well. His essay should be prime reading for everyone involved in film culture—e.g., you.

WYSIWYG

I’ve mentioned the postcard effect that makes static objects just hang there. In less-than-2K digital displays, I see other artifacts, most of which I don’t know the terms for. Film has artifacts too, notably graininess, but I find the digital ones more off-putting. There’s a waterfall effect, when ripples rush down uniform surfaces. Sometimes I see diagonal striping from one corner to its opposite, an effect common on home and bar monitors. (I’m told it comes from interference from phones and the like.) On cheap DVDs, or commercial ones played on region-free machines, you can detect a weird pop-out effect, where the surfaces of different planes, usually marked by dark edge contours, detach themselves. The surfaces float up, wobbling out of alignment with their surroundings.

I am not hallucinating these things. When I point them out, others see them, and then, like me, they can’t ignore them. So I’ve stopped pointing them out, especially when a friend wants to show me his (always his) fancy home theatre. Why spoil their pleasure?

Same difference

Various positions on the split between film and digital (for want of a better term): I’ve held nearly all of them at various points, and sometimes simultaneously. I’ll confine myself, as usual, just to film-based projection and digital projection, and assuming minimal competence of staff in each domain. (Just because something’s shown in 35mm, that doesn’t mean it’s shown well.)

1. They’re not the same, just two different media. They’re like oil painting and etching. Both can coexist as vehicles for artists’ work.

2. They’re not the same, and digital is significantly worse than film. This was common in the pre-DCI era.

3. They’re not the same, and digital is significantly better than film. Expressed most vehemently by Robert Rodriguez and with some insistence by Michael Mann.

4. They’re not the same, and digital is mostly worse, but it’s good enough for certain purposes. Espoused by low-budget filmmakers the world over. Also embraced by exhibitors in developing countries, where even 1.3K is considered an improvement over what people have been getting.

5. They’re the same. This is the view held by most audiences. But just because viewers can’t detect differences doesn’t mean that the two platforms are equally good. Digital boosters maintain that we now have very savvy moviegoers who appreciate quality in image and sound. In my experience, people don’t notice when the picture is out of focus, when the lamp is too dim, when the surround channels aren’t turned on, when speakers are broken, and when spill light from EXIT signs washes out edges of the picture. (See Chronicle anecdote above.) As long as they can hear the dialogue and can make out the image, I believe, most viewers are happy.

‘Plex operators are notoriously indifferent to such niceties. In most houses, good enough is good enough. Teenage labor can maintain only so much.

Film/video

“The picture was nice and crisp.” “So much better than film.” “We showed a Blu-ray and it looked fine.”

I don’t trust people’s responses to such things unless the judgment is comparative. Show film and the digital program side by side and then judge. Or even show rival manufacturers’ DCI-compliant projectors side by side. I think you will see differences.

As they develop, new reproductive media improve in some dimensions but degrade on others. As the engineers tell us, there’s always a trade-off.

CD is more convenient than vinyl, but its clean, dry sound isn’t as “warm.” Mp3, even more convenient and portable, packs a sonic punch but is inferior in dynamics and detail to CDs. Similarly, back in the 1990s, laserdiscs had to be handled more carefully than tape cassettes, and in playback they required interruptions as sides were flipped. But aficionados accepted these drawbacks because we believed that our optical discs looked and sounded much better than VHS. One well-known professor urged that classroom screenings could now dispense with film.

Now those laserdisc images would be laughed out of the room. Have a look at an image from the 1995 restoration of Disney’s Pinocchio. It’s taken from a transfer of the laserdisc to DVD-R. (You can’t grab a frame directly from a laserdisc.) In this and the others, I haven’t adjusted the raw image.

Actually, on a decent monitor, it looks better than this. Since you can’t grab a frame directly from a laserdisc, LD couldn’t stand up to home theatre projection today. The 2009 DVD and Blu-ray (below) are sharper.

Now compare the DVD with a dye-transfer Technicolor image from a 1950s 35mm print. There have been some gains and some losses in color range, shadow, and detail. For example, Stromboli’s trousers and the footlight area go very black, presumably because of the silver “key image” used for greater definition in the dye-transfer process. IB Tech restorations routinely bring out “hidden” color in such areas.

Which is best? You can take your pick, but you’re better able to choose when you’re not seeing one image in isolation.

Live/ Memorex

Of course side-by-side comparisons can fail when most viewers don’t notice even gross differences. In a course, I once showed a 16mm print of Night of the Living Dead, and a faculty friend came to the screening. (Yes, history profs can be horror fans.) In my followup lecture, I showed clips on VHS, dubbed from a VHS master. My friend came to the class for my talk. Afterward he swore that he couldn’t tell any difference between the film and the second-generation VHS tape.

This raises the fascinating question of changing perceptual frames of reference. My friend knew the film very well, and he’d watched it many times on VHS. Did he somehow see the 16 screening as just a bigger tape replay? Did none of its superiority register? Maybe not.

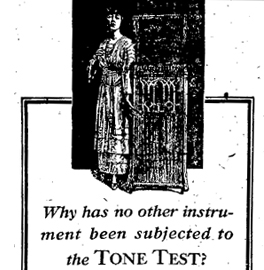

From 1915 to 1925, Thomas Edison demonstrated his Diamond Disc Phonograph by inviting audiences to compare live performances with recordings. His publicists came up with the celebrated Tone Tests. A singer on stage would stand by while the disc began to play. Abruptly the disc would be turned down and the singer would continue without missing a note. Then the singer would stop and the disc, now turned up, would pick up the thread of melody. Greg Milner writes of the first demonstration:

From 1915 to 1925, Thomas Edison demonstrated his Diamond Disc Phonograph by inviting audiences to compare live performances with recordings. His publicists came up with the celebrated Tone Tests. A singer on stage would stand by while the disc began to play. Abruptly the disc would be turned down and the singer would continue without missing a note. Then the singer would stop and the disc, now turned up, would pick up the thread of melody. Greg Milner writes of the first demonstration:

The record continued playing, with [the contralto Christine] Miller onstage dipping in and out of it like a DJ. The audience cheered every time she stopped moving her lips and let the record sing for her.

At one point the lights went out, but the music continued. The audience could not tell when Miller stopped and the playback started.

The Tone Tests toured the world. According the publicity machine run by the Wizard of Menlo Park, millions of people witnessed them and no one could unerringly distinguish the performers from their recording.

Edison’s sound recording was acoustic, not electrical, and so it sounds hopelessly unrealistic to us today. (You can sample some tunes here.) And there’s some evidence, as Milner points out, that singers learned to imitate the squeezed quality of the recordings. But if the audiences were fairly regularly fooled, it suggests that our sense of what sounds, or looks, right, is both untrustworthy and changeable over history.

To some extent, what’s registered in such instances aren’t perceptions but preferences. Wholly inferior recording mechanisms can be favored because of taste. How else to explain the fact that young people prefer mp3 recordings to CDs, let alone vinyl records? It’s not just the convenience; the researcher, Jonathan Berger of Stanford University, hypothesizes that they like the “sizzle” of mp3.

To some extent, we should expect that people who’ve watched DVDs from babyhood onward take the scrubbed, hard-edge imagery of video as the way that movies are supposed to look. Or perhaps still younger people prefer the rawer images they see on Web videos. Do they then see an Imax 70mm screening as just blown-up YouTube?

The epiphanic frame

Godard’s Éloge de l’amour: DVD framing vs. original 35mm framing.

Digital projection is already making distributors reluctant to rent films from their libraries, and film archives are likely to restrict circulation of their prints. When 35mm prints are unavailable, it will be difficult for us to perform certain kinds of film analysis. In order to discover things about staging, lighting, color, and cutting in films that originated on film, scholars have in the past worked directly with prints.

For example, I count frames to determine editing rhythms, and working from a digital copy isn’t reliable for such matters. True, fewer than a dozen people in the world probably care about counting frames, so this seems like a trivial problem. But analysts also need to freeze a scene on an exact frame. For live-action film, that’s a record of an actual instant during shooting, a slice of time that really existed and serves to encapsulate something about a character, the situation, or the spatial dynamics of the scene. (Many examples here.) This is why my books, including the recent edition of Planet Hong Kong, rely almost entirely on frame grabs from 35mm prints.

Paolo Cherchi Usai suggests that for every shot there is an “epiphanic frame,” an instant that encapsulates the expressive force of that shot. Working with a film print, you can find it. On video, not necessarily.

Just as important, for films originating in 35mm, we can’t assume that a video copy will respect the color values or aspect ratio of the original. Often the only version available for study will be a DVD with adjusted color (see Pinocchio above) and in a different ratio. I’ve written enough about variations in aspect ratios in Godard and Lang (here and here) to suggest that we need to be able to go back to 35mm for study purposes, at least for photographically-generated films. For digitally-originated films, researchers ought to be able to go back to the DCP as released, but that will be nearly impossible.

The analog cocoon

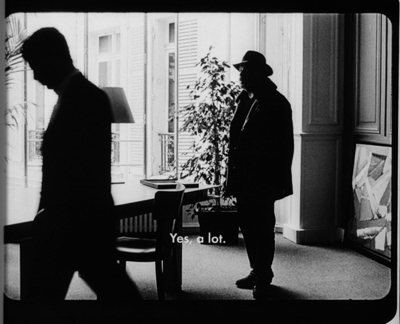

I began this series after realizing that in Madison I was living in a hothouse. As of this fall, apart from festival projections on DigiBeta or HDCam, I hadn’t seen more than a dozen digital commercial screenings in my life, and I think nearly all were 3D. Between film festivals, our Cinematheque, and screenings in our local movie houses, I was watching 35mm throughout 2011, the year of the big shift.

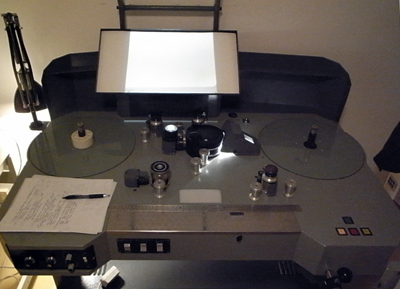

There are six noncommercial 35mm film venues within walking distance of my office at the corner of University Avenue and Park Street. And two of those venues still use carbon-arc lamps! Go here for a fuller identification of these houses. Moreover, in my office sit two Steenbeck viewing machines, poised to be threaded up with 16mm or 35mm film. (“Ingestion” is not an option.)

But now I’ve woken up. We all conduct our educations in public, I suppose, but preparing this series has taught me a lot. I still don’t know as much as I’d like to, but at least, I now appreciate the riches around me.

I’m very lucky. It’s not over, either. The good news is that the future can’t really be predicted. Like everybody else, I need to adjust to what our digital Pandora has turned loose. But we can still hold on to hope.

This is the final entry in a series on digital film distribution and exhibition.

On the Pandora perplex, see Dora and Erwin Panofsky, Pandora’s Box: The Changing Aspects of a Mythical Symbol (Princeton University Press, 1956). The Wikipedia article on the lady is also admirably detailed.

Godfrey Cheshire’s prophetic essay is apparently lost in the digital labyrinths of the New York Press. Godfrey tells me that he’s exploring ways to post it, so do continue to search for it. Another must-read assessment is on the TCM site. Pablo Kjolseth, Director of the International Film Series at the University of Colorado—Boulder, writes on “The End.” See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensible take on the announcement that Panavision has ceased manufacturing cameras. Some wide-ranging reflections are offered in Gerda Cammaer’s “Film: Another Death, Another Life.”

Brian McKernan’s Digital Cinema: The Revolution in Cinematography, Postproduction, and Distribution (MGraw-Hill, 2005) is the source of two of my quotations from George Lucas (pp. 31, 33) and some ideas about the film look (p. 67). My quotation from Greg Milner on the Tone Test comes from his Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music (Faber, 2009), 5.

NPR recently broadcast a discussion of the differences, both acoustic and perceptual, among consumer audio formats. The show includes A/B comparisons. Thanks to Jeff Smith for the tip.

Thanks to Chapin Cutler, Jeff Roth, and Andrea Comiskey, who prepared the projector map of downtown Madison and the east end of the campus.

6 February 2012: This series has aroused some valuable commentary around the Net, just as more journalists are picking up on the broad story of how the conversion is working. Leah Churner has published a useful piece in the Village Voice on digital projection, and Lincoln Spector has posted three essays at his blogsite, the last entry offering some suggestions about how to preserve both film-based and digital-originated material.

“You get soft, Pandora will shit you out dead, with zero warning.”

Pandora’s digital box: Pix and pixels

Peter Rotsaert and Vico De Vocht examine a digital version of a silent film at the Brussels Cinematek.

DB here:

Today Dawson City, in the Yukon Territory of Canada, has fewer than two thousand people, but in the 1890s tens of thousands passed through in search of gold. Movies came along too, but the remoteness of the place made it the end of the line for most prints. Many were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library. In 1929, an enterprising bank worker shifted them to an abandoned swimming pool. The stacks of films were covered with planks, and they were in turn covered by earth, so the films were buried in the permafrost. The surface became an ice hockey rink.

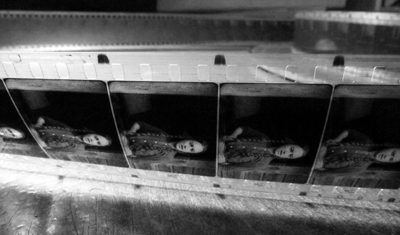

In 1978, builders discovered the film cache. Sam Kula, then an archivist at the National Archives of Canada, stored the films temporarily in an ice house. The painstaking process of checking each reel began. Eventually the US Library of Congress was brought in because most of the 507 reels discovered were American. Among the finds were a Harold Lloyd short, a great deal of news footage, and a rich array of serials starring heroines of the 1910s.

Wellington, New Zealand, was another terminus for American movies during the old days. In 2009, a film preservationist from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences learned that the New Zealand Film Archive held a lode of Hollywood films. The collection, reviewed here, includes many Westerns and Christie comedies, along with John Ford’s supposedly lost Upstream (1927). The restored Upstream played in festivals and special screenings during 2010 and 2011. Five American archives have been involved in restoring the seventy-five titles selected for repatriation.

Whatever the merits of the films revealed—literally unearthed, in the Dawson instance—discoveries like these are signs of hope. Who knows how much more of our film heritage remains to be rediscovered? For this reason, George Eastman House archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai prefers to list a film not as “lost” but rather as “not yet found.”

Given such discoveries, the archivists will set to work creating usable and enduring versions. But today such a task is much harder. Soon most of the films we make and show will not exist on photochemical stock. They’ll be digital files, and they need to be kept securely. But how?

Will today’s typhoon of ones and zeroes rip away our analog past? Will there ever be a digital Dawson City, a stockpile of files of lost movies? It seems likely that digital projection has, in unintended and unexpected ways, put the history of film in jeopardy.

Digital restoration: A success story

Nitrate decomposition; from Bill Morrison’s Decasia: The State of Decay (2004).

Of the tens of thousands of feature films produced worldwide in the silent era, approximately ten per cent survive.

Jan-Christopher Horak, Director, UCLA Film and Television Archive

The archives I’m speaking of are either public ones, like the Library of Congress, or privately supported ones like Eastman House and the Museum of Modern Art. These and hundreds of smaller archives are nonprofit institutions charged with protecting images and sounds we’ve deemed of cultural value. By contrast, a studio-based archive aims to maintain the firm’s investment in its property. Often studios deposit films of historical importance at nonprofit archives; some countries require by law that copies of films circulated there be deposited in the national archive. Both sorts of archives have done excellent work, but I’ll be talking largely of the nonprofit ones, which often receive films by donation, deposit, purchase, or accident.

Archivists distinguish between conserving and preserving. You conserve a film by taking it into the archive and storing it safely in temperature-and-humidity controlled vaults. You preserve it by cleaning and patching it, and if necessary transferring it to a more stable medium. Restoration, which is the archival task most visible to the film-loving public, goes further. It involves working to bring the film back to something like its original state.

Before the 1970s, archives conserved and preserved, but seldom restored. Archivists at public institutions balanced two duties: keeping films safe for the future and screening them for the public and researchers. Like art museums, archives guarded treasures while putting some of them on display.

Most often, archives preserved their material by making the best possible copies. A big part of the job was migrating films from one format to another. For example, some early American film companies copyrighted their product by submitting rolls of paper on which each frame of film had been printed. These “paper prints” had to be transferred, frame by frame, to motion-picture film. Likewise, films surviving only in rare formats, like 9.5mm, 22mm, and 28mm, had to be transferred to 35mm so they could be run on standard equipment. Tinted films on nitrate were reprinted on black and white safety film. 16mm films might be blown up to 35mm, and 35mm might be reduced to 16mm for circulation to schools, libraries, and film clubs.

Most famously, thousands of films in archive collections exist on nitrate stock. That was the professional standard before 1950 or so, when the industry abandoned it. Not only did nitrate film have a habit of exploding or catching fire, but it tended to decompose. Experimental filmmakers have found a sinister beauty in ruined footage, but archivists organized for funding to help transfer their collections to acetate. Then archivists learned that some acetate prints degenerated into a vinegary, contagious vapor. So migration to a new, polyester-based stock became necessary.

Most famously, thousands of films in archive collections exist on nitrate stock. That was the professional standard before 1950 or so, when the industry abandoned it. Not only did nitrate film have a habit of exploding or catching fire, but it tended to decompose. Experimental filmmakers have found a sinister beauty in ruined footage, but archivists organized for funding to help transfer their collections to acetate. Then archivists learned that some acetate prints degenerated into a vinegary, contagious vapor. So migration to a new, polyester-based stock became necessary.

Preservation, simply keeping films alive in long-lasting formats, remained central to archives. In the 1970s a number of archivists also began restoring films. For example, most silent feature films were released in tinted and toned prints, but many copies survived only in black-and white. Restorers, guided by surviving paper records, aimed to create prints that approximated the original color schemes.

Restorers naturally faced decisions about what would count as an original. In 1989 there were six different versions of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, running from 119 minutes to 132 minutes. In uncertain cases, records of running times and postproduction work helped identify what was missing. If the footage couldn’t be found, still photos or even a blank screen might cover the gaps, as in restorations of Greed and the 1954 A Star Is Born. A musical score helped researchers measure how much footage from the original Metropolis remained to be found.

With the rise of cable television and home video, studios’ film libraries became more valuable. Ted Turner, owner of the MGM, Warner, and RKO libraries, was blamed for “colorizing” some classics for his cable channels, but at the same time he invested in restoring a great many of them. Other firms followed suit. Gone with the Wind and Disney perennials were reworked for cable and VHS release.

The 1980s and 1990s became the great age of restorations. Audiences were reintroduced to Napoleon, Becky Sharp, Lawrence of Arabia, and Vertigo. Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, working with Thames Television, reissued silent classics, with new scores by Carl Davis. Most of the era’s restorations wound up on video platforms. Today Turner Classic Movies is our great display case for studio and off-Hollywood restorations; it’s the closest thing we have to a Citizen’s Film Library.

At first, restoration was a photochemical affair. Every major archive employed experts in rephotography and lab work who knew how to optimize the look of a print. Archivists like Noël Desmet collected information about properties of old film stocks and tinting dyes. Faded films could be reprinted through filters that might bring back some of the old snap. The look of old films was much improved by wet-gate printing, which bathed the frames in a liquid that masked scratches on the base or emulsion.

But not much could be done about the blotchy nitrate decay that might invade a scene, or the dirt and dust that earlier copies of the film bequeathed to the current one. And those films for which no original negative could be found, including Citizen Kane and Singin’ in the Rain, would always be seen as the shadow of a shadow—new copies pulled from earlier, perhaps shabby ones.

The upside was that as long as you kept your source prints and your restorations on 35mm film stock in a cool, dry place, you had material that would last over 100 years. Some day you might find better tools for improving what you had.

That day came fairly soon. The Disney company had a steady income from theatrical and video re-releases of its animation classics, and a 1990 reissue of Fantasia employed some video-paint work to correct flaws in the frames. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was then given high-resolution treatment. Dust-busting and color adjustments were made frame by frame. Re-released in 1993, Snow White was the first feature to be restored digitally.

Since then, digital fixups have become a standard method for archival restoration. Footage is scanned into a file at 2K or 4K resolution. Either manually or automatically, the software can correct for jumpy or shaky imagery, do dust-busting, erase scratches, and balance exposure, contrast, and other factors. It can interpolate image areas in order to correct damages in the frame, and it can add tinting or toning. The finished files may then be saved as files or scanned back onto film, as Snow White was. You can see an example from the newly restored Marcel Carné film, Children of Paradise (Les Enfants du paradis).

Soon most restorations are likely to be finished and screened on digital formats, with virtually no 35mm prints circulating.

Born-digital, born-again digital?

Decay of digital imagery, from Creative Applications.

The preservation of born-digital films is going to be the greatest challenge ever to face archivists.

Margaret Bodde, Executive Director of the Film Foundation

The new magical software has sometimes led to over-restoration. Grain has too often been polished out, creating a plastic sheen. Still, today no archivist can avoid using the new toolkit. The sadder story involves not restoration but conservation and preservation. A civilian might think: That’s simple. Just save film on film and digital on digital. But things are more complicated than that.

Let’s start with a movie like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, which was shot with digital capture. After production and post-production, it was made available to theatres as both a Digital Cinema Package (that batch of files on a hard drive) and some 35mm prints. But there are several digital versions of the movie.

Digital source material. The original sound and image “content” may be captured in specific formats, either tape-based or file-based. Those formats can vary a lot among themselves. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, for example, was shot with the Red One camera on the company’s proprietary format R3D. Other cameras don’t use that format. So the footage was converted to other sorts of files for viewing and postproduction work.

Any major film nowadays is likely to use many digital video and audio formats. All these assets are usually stored in the distributor’s vaults.

The Digital Source Master (DSM or DCM). This is the master copy of the finished film, somewhat comparable to a 35mm film negative. It can be in any format selected by the filmmakers. It’s the basis of the distribution master, the home video master, and a master version for archival storage.

The Digital Cinema Distribution Master (DCDM), in formats determined by the Digital Cinema Initiatives. This is the finished film unencrypted and uncompressed, providing “content” at 2K and/or 4K resolution. Roughly speaking, this is the digital counterpart of a 35mm release print.

The Digital Cinema Package (DCP). This is the film compressed and encrypted for theatrical playback. It’s roughly comparable to the delivery of a 35mm print on shipping reels.

The Digital Cinema Distribution Master as played (DCDM*) Once the DCP files are opened and decompressed, they yield image and sound identical to what’s encoded on the DCDM. The DCDM*’s place in the system is somewhat parallel to the projection of a 35mm print from platters.

Eventually, The Girl will show up on the optical disc formats DVD and Blu-ray, not to mention streaming video, cable transmission, and web-based platforms. (Actually, it’s probably already available for Darknet download.)

Many studio films are housed in nonprofit archives too, and until recently those movies have been deposited and stored as analogue copies. But what will those institutions now keep? There are only three minimally acceptable formats: the uncompressed and unencrypted DCDM, the DCP, and a 35mm print. Suppose your film archive is lucky enough to receive both a DCP and a 35mm print of The Girl.

First, how do you access the DCP files? A DCP is typically encrypted to block piracy. When The Girl played theatres digitally, each exhibitor was provided an alphanumeric password that would open the files for loading into the theatre’s server. By the time you the archivist get the files, that key may have expired or been lost. Without the key, the DCP is useless.

Then there’s the matter of storage. The 35 print of The Girl can simply be passively conserved, following the motto, “Store and ignore.” But all digital material, no matter how minor, requires proactive preservation. The future for digital storage is constant migration.

Archivists estimate the life of any digital platform to be less than ten years, sometimes less than five. All hard drives fail sooner or later, and they need to be run periodically to lubricate themselves. Tape degradation can be quite quick; one expert found that 40 % of tapes from digital intermediate houses had missing frames or corrupted data. Most of the tapes were only nine months old.

Moreover, hardware and software are constantly changing. One archivist estimates that over one hundred video playback systems have come and gone over the last sixty years. Archives currently recognize over two dozen video formats and over a dozen audio ones.

Periodically, then, the DCP files of The Girl will have to be checked for corruption and transferred to another tape or hard drive and eventually to another digital format. Such maintenance takes time; shifting a terabyte of data from one system to another may need at least three or four hours. Ideally, you’d want several copies for backup, and you’d want to store them in different locations.

There are hundreds of other films like The Girl awaiting processing at major archives. About 600-900 feature films are produced in the US each year. Currently the world is producing about 5500 features per year. At some point, they will all originate in digital capture.

Besides access and storage there’s the matter of cost. Storing 4K digital masters costs about 11 times as much as storing a film master. You can store the digital master for about $12,000 per year, while the film master averages about $1,100.

How do the overall costs of digitizing mount up? Look at the situation in Europe. The EU countries produce about 1100 features and 1400 shorts per year. An EU archival commission, the Digital Agenda for European Film Heritage, estimates that to conserve one year’s output would require 5.8 PB (petabytes) of storage. In 2015, the costs of archiving that year’s output (without restoration) are projected to be between 1.5 million and 3 million euros. Beyond initial conservation, long-term preservation of that year’s output would consume, though migration and backing up, about 1900 PB and cost about 290 million euros.

The access problem is soluble. Your archive could be given an unencrypted DCP of The Girl and then create its own key to prevent copying. Or the DCP could be assigned a generic key, perhaps for a specified time period, that will open the files in a secure milieu. They could then be migrated to a format under archive control. On the matter of software, archivists are working on establishing standard preservation file formats and codecs. To deal with the other problems, you’d have to press for increased budgets and personnel to cover the new duties that digital archiving creates. But the costs, including training personnel on ever-changing platforms, are of tidal-wave proportions.

Photochemical Armageddon?

The methods we have for securely storing comprehensible digital data are highly labour-intensive. Humans are too slow and they cost too much.

Bruce Sterling, science-fiction writer

So why don’t you preserve The Girl’s files on film? Film is universally recognized as the most stable platform for moving-image material. Properly stored, a film print can last a hundred years or more. Maintaining a print, as we’ve seen, is cheaper than maintaining digital files. It’s significant that the archives of most of the major studios continue to transfer all their current features to film via color separations on polyester stock.

Apart from the costs of making file-to-film transfer, which can amount to tens of thousands of dollars, the long-range problem is technology. The same forces that shoved out 35mm projection have made 35mm preservation much harder. The equipment for outputting digital files onto film will eventually cease to be available. With the rise of digital projection, demand for film stock plummeted. Eastman Kodak’s recent bankruptcy filing reflects the declining market for raw film, and even though Fuji promises to continue to make 35mm stock, it is likely to get more expensive. As David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest points out, the cost of silver, a necessary component of raw stock, is rising steeply after being low for many years.

Sensing a niche market, Kodak has announced that it will provide a new emulsion favorable to archival preservation. But at the moment, laboratories that can process and print any film stock are closing. Not for nothing does Nicola Mazzanti, Director of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, suggest that an archive should consider buying a lab, which is likely to be available at a low price.

If preserving on film is increasingly unlikely, how about preserving on digital formats? Perverse as it sounds, can you take your 35mm print of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and store it as tape or files? Yes. This is called “digital reformatting.” Once film has been scanned, archives can make DCPs at low cost. But the initial scanning is costly, and high-end 35mm scanners, though still in use to make Digital Intermediates for 35mm releases, are likely to be costly for nonprofit archives. In any event, saving film digitally puts us back to the problems of digital conservation and preservation: cost, storage, maintenance, and access. (Surely the rights holders will want the archive to encrypt its home-made DCPs.)

Preserving on film may simply postpone Armageddon. As the most recent European report of the Digital Agenda for European Film Heritage concludes:

As a solution [digital migration to film] will only be viable as long as the analogue film ‘ecosystem’ (equipment, film stock, laboratories) exists. Instead of being a long-term solution, the risk is that it becomes a very short term one. In the long term it will make problems worse as it will increase the number of works that need to be digitised in the future. . . . At 25,000 euros to 100,000 euros per feature film, the going-back-to-film solution appears to be 20 to 80 times more expensive than digital preservation.

It’s hard to get your mind around the scale of the problem. Here is Ken Weissman of the Library of Congress:

Speaking very broadly, with 4K scans of color films you wind up in the neighborhood of 128 MB per frame. . . . Figure that a typical motion picture has about 160,000 frames, and you wind up with around 24 TB per film. And that’s just the raw data. Now you process it to do things like removing dust, tears, and other digital restoration work. Each of those develops additional data streams and data files. We’ve decided, based upon our previous experience, that it is best to save the initial scans as well as the final processed files for the long term. Now we are up to 48 TB per film. In our nitrate collection alone, we have well over 30,000 titles. 48 TB x 30,000 = 1,440,000 TB or 1.44 EB (exabytes) of data.

Weissman adds with a trace of grim humor: “And of course you want to have a backup copy.”

The girl with the photochemical tattoo

I think that film-on-film projection will ultimately become the sole purview of archives and museums.

Michael Pogorzelski, Director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive

Once you’ve found a way to conserve-preserve The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, what if you want to show it tomorrow? Or ten years from now? Or fifty?

If you have a DCP in good shape, and a projector that will show 2K/4K according to the Digital Cinema Initiative standard, you’re good to go. For now. But maybe not tomorrow.

Once the projector/ server market has saturated and everybody has DCI-compliant equipment, equipment manufacturers and software designers have to keep innovating to sell new machines. Many observers expect the D-cinema standard to be recast in the next ten to fifteen years, and projectors may be redesigned sooner than that. Mazzanti anticipates that there will be 8K resolution, greater bit depths, faster frame rates, laser projection, new sound formats, and other advances. Already innovations are leapfrogging DCI standards: last month, a new generation of projectors was showcased. If you program your digital version of The Girl for its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2036, you will probably have to reformat it for whatever your projector can then play.

So instead you hold on to your 35mm print. That will give you cachet, because within a decade all commercial cinemas will be digital, and, as Mike Pogorzelski mentions, only archives will show 35. But cachet takes cash. Archives, at least the major ones, will have to retain their 35mm inspection and projection gear, even though that will probably cease to be made and parts will be cannibalized. You’ll need vigilant, resourceful staff who know how to fix old machines.

Moreover, with the scarcity of raw stock and the shuttering of laboratories, archives will be less likely to make screening copies of their holdings. Virtually every 35mm copy you the archivist hold, from Red Desert to a Bowery Boys movie, becomes irreplaceable, what Mazzanti calls a “unique master.” Then film archives will truly become film museums, custodians of extremely rare artifacts.

At some point no one may risk running analog film, as the damage would be irreparable. In that worst-case scenario, archives will show digital copies, either derived from prints or supplied by whatever sources they can find (including, yes, Blu-ray or whatever comes after). One consequence may be the freezing of the canon. We’ll get more and better versions of old standbys like Metropolis and Napoleon, but less effort to retrieve lost or ignored items from scratch. New discoveries may simply be too expensive to maintain, especially if they lack the crowd-pleasing appeal of the most famous classics.

I biased the case by taking as typical a major studio production like The Girl. What about the hundreds of independently made shorts and features? I’m thinking of documentaries, DIY features, animated shorts, and experimental works. Each was made on whatever video or film format the filmmaker could find or could afford, and it was finished with almost no thought of how it would be preserved. The Science and Technology Council of the Academy recently published its second comprehensive study of “the digital dilemma” and were surprised that most of the filmmakers they interviewed were unaware of how perishable their work was. Says Milt Shefter, an author of the report:

They were concentrating on the benefits of the digital workflow, but weren’t thinking about what happens to their [digital] masters. They’re structured to make their movie, get it in front of an audience, and then move onto the next one.

Still more unaware, I imagine, are all the people making amateur footage.

Lumière’s La Petite fille et son chat was made in 1900 and is still around to charm us. The YouTube adventures of Maru, a LOLcat superstar, aren’t likely to last so long.

Envoi