Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

Hopscotching through history

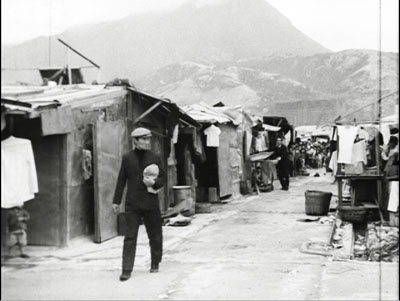

Temple Street, Hong Kong.

DB here:

Thanks to the Film Festival and screenings at the Film Archive, I’ve skipped gratefully through nearly a hundred years of local film history.

The Roast Duck legend, cooked at last?

First things, or rather first films, first. Last year local authorities declared 2009 to be the centenary of Hong Kong cinema. The long-standing claim (repeated in my Planet Hong Kong) was that To Steal a Roast Duck, aka The Trip of the Roast Duck, was made in 1909 and was the first locally produced fiction film. The controversy arose because the claim was based on later recollections of filmmakers. No fiction films from that era survived. We had no contemporary evidence that the Roast Duck was made in that year or that it was the first anything. Perhaps it wasn’t even made at all? In a blog entry last year, I summed up the arguments.

Now, thanks to the persistence of Frank Bren and Law Kar, we can come to more reliable conclusions. At a conference in December, scholars from around the world gathered at the Hong Kong Film Archive to discuss early Chinese cinema. One of the results was further revelations about the territory’s first film.

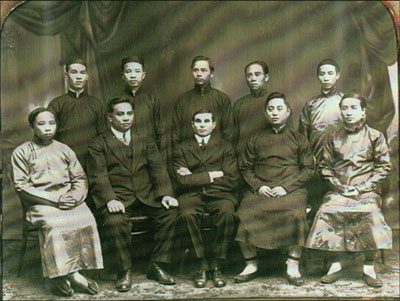

We know that at some point the Ukrainian-American entrepreneur Benjamin Brodsky came to Hong Kong and set up a film unit. (The picture above shows him surrounded by nine Chinese co-directors of the company he founded in November 1914.) An earlier Brodsky company made Roast Duck, among other films. But when?

At the conference Law Kar announced the discovery of a 1914 Moving Picture World interview with Roland Van Velzer, a photographer recruited from New York by Brodsky. During his stay in what he called “that queer land” of Hong Kong, Van Velzer shot four films in 1914.

We did a first native drama, entitled “The Defamation of Choung Chow.” With my experience and guidance the picture turned out well and when shown in public proved to be a wonderful drawing card. . . . The reason of its great popularity was because it was a Chinese piece entirely. . . . We made three other subjects during my stay there. These were: “The Haunted Pot,” The Sanpan Man’s Dream” and “The Trip of the Roast Duck,” the latter a rough “chase” picture. All of these pictures had phenomenal runs at the native theaters.

According to Van Velzer, then, the first film, made and shown in 1914, was what is now known as Chuang Tzi Tests His Wife. Roast Duck was evidently the fourth film made by the team that year.

Brodsky is significant not merely because he supported talent in producing the colony’s first fictional films. He also made long documentaries about China and Japan that played in the US. He seems to have been a colorful guy. In his barnstorming circus days, he once purged a lion with castor oil. Full details are here in an article by Bren and Kar. In the meantime, we can look forward to a more plausible centenary of Hong Kong film in 2014.

Social conscience, modern stylings

The Story of a Discharged Prisoner.

Hop ahead to the 1960s. Although the local language of Hong Kong is Cantonese, movies in Mandarin rule the market, with Shaw Brothers providing gaudily colored costume pictures, musicals, romantic dramas and comedies, and of course rather violent swordplay exercises. By contrast films made by Cantonese companies under tiny budgets look threadbare. Yet a few filmmakers tried to make Cantonese cinema more vigorous and innovative, and the most influential was Patrick Lung Kong.

Lung Kong was born in 1935, and by the time he was thirty he had performed in virtually every production role, from screenwriting and producing to publicity and distribution. Well-known as an actor since 1958, he graduated to directing in1966 with Prince of Broadcasters. His second film, The Story of a Discharged Prisoner (1967) was a landmark in local cinema, expressing sympathy for an ex-convict who tries to avoid being pulled back into crime. Lung Kong goes on to make many of the socially critical films of the period: Teddy Girls (1969), Hiroshima 28 (1974), and Mitra (1976). He ceased directing in 1981 but continued to work as an actor and distributor. He now lives in New York City, but he came back for the retrospective that the Film Archive has mounted.

I had seen some Lung Kong films in earlier visits to Hong Kong, but the retrospective will allow us to assess his career as a whole. Virtually none of his films are available on DVD, and none, as far as I know, with English subtitles. Particularly important, apart from the works I’ve mentioned, are his heavily censored film about a plague striking Hong Kong, Yesterday Today Tomorrow (1970) and the bitter domestic drama Pei Shih (1972).

When he started in the industry, he says, “I ran into these acquaintances who taunted me by saying how I was trying my hand at making Cantonese chaan pin [shabby films]. That was very insulting to the film profession in general…so I promised myself to go in and change things when the opportunity arose.” For him, change meant both modernizing Cantonese film technique and tackling social problems.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung’s film style is self-consciously 1960s modern, with zooms, calculated compositions, and handheld passages. He cuts fast, avoids dissolves, and offers fairly complex traveling shots. Looking at the cheap sets and listening to the awkward sound (including snippets of classical music and The Great Escape grabbed from LPs), one becomes aware of what a Cantonese director of the day was up against. So if the technique seems at times forced, you can at least admire Lung’s attempt to give his films a contemporary gloss.

The films were of crucial importance for local culture of the 1960s and have had continuing influence on younger directors. A very informative book of essays and interviews, produced to the usual handsome standards of the Film Archive, is in Chinese but includes a disk with a digital pdf of English translations. Two of the texts can be found here.

Jean Christophe in Macau

Another hop. I know nothing about Louis Fei, except that he was the brother of Fei Mu, whom I’ll be talking about in an upcoming entry. Romance in the Boudoir (1960) recasts the core situation of Fei Mu’s masterpiece Spring in a Small Town (1948). The situation, drawn from Romain Rolland’s novel Jean Christophe, is simple: A woman in a loveless marriage is visited by her former lover. In this version, her husband is a miserly doctor who wants the lover, Qin, to help him get a hospital post. Qin’s presence in the household rekindles the old romance and the couple hover on the edge of adultery.

Romance in the Boudoir is a bold piece of work. It opens with a prologue showing husband and wife trudging through Macau, utterly distant from each other. On the soundtrack we hear a woman singing about marriage as a prison. When Qin arrives, a parallel sequence traces him from the harbor to the household as a male vocalist sings of his weariness and broken heart. These melodic soliloquies will be evoked later in the film, when Qin and Suxuan stretch out by the fireplace and start to sing as the camera circles them.

Louis Fei makes maximal use of the house set, letting the vast staircase dominate the action on both floors. Repeated setups from the top of the stairs show the bannister cutting diagonally into the frame, pointing like an arrow to the climactic moment at the front door in the distance. Over everything hovers erotic tension, lasting several minutes during one scene when the former lovers tentatively touch one another before recoiling and then drawing toward one another again. If the doctor is somewhat caricatural, the portrayals of the wife and lover show a great subtlety, and the use of props, notably a glass of milk, is nicely modulated. This film shows how comparative large budgets enabled the Mandarin-language companies to make films of a high production standard, both in script and execution.

Dragons on fire

Now jump to 2010. Dante Lam is the hot new action director on the local scene, after the success of Beast Stalker (2008) and The Sniper (2009). Actually, like most overnight successes, he’s been at it awhile. He made an admirer of me with Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), which has one of the most graceful passages of graphic cutting (involving a red umbrella) that I’ve seen in recent Hong Kong film.

He’s back with the first big action film of the season, tagged with the barely adequate English title Fire of Conscience. The action scenes are better than the plot, which is better than the eternal impassivity of Leon Lai, a pictorial cipher in nearly every role he assumes. Still, you have to reckon with a film that includes not only a thrilling car chase, a truly scary gunfight in a restaurant, and grenades tossed around pretty casually but also a pregnant woman locked in a car slowly filling with carbon monoxide. The topper comes in the very last few shots, which provide as gruesome a flashback image as I’ve seen in quite some time and justifies the key line, “Save for revenge, what else is there?”

Visually, Fire of Conscience never surpasses the bravado of the black-and-white CGI opening, during which the camera coasts through a snapshot of action and lets clues float and scatter around the frozen characters. (It’s admittedly gimmicky, but more hypnotic than the comparable Watchmen opening.) Still, it’s exciting genre fare. What hath Ben Brodsky wrought?

Photo of Brodsky and colleagues by courtesy of Mr. Ronald Borden. The interview with R. F. Van Velzer was published in Hugh Hoffman, “Film Conditions in China,” Moving Picture World (25 July 1914), 577. Thanks to Frank Bren and Law Kar for this information, and to Tony Slide for calling attention to the article. The quotation from Lung Kong is from Clarence Tsui, “Scenes of the Crime,” South China Morning Post (22 March 2010), C1.

Patrick Lung Kong, with Sam Ho of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Her design for living

Kristin in Rome, 1997, in front of a “recent” hand from a colossal statue of Constantine. The Amarna statuary fragments she studies are twice as old.

DB here:

Kristin is in the spotlight today, and why not? She’s too modest to boast about all the good things coming her way, but I have no shame.

First, our web tsarina Meg Hamel recently installed, in the column on the left, Kristin’s 1985 book Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market 1907-1934. It was never really available in the US and went out of print fairly quickly. Vito Adriaensens of Antwerp kindly scanned it to pdf and made it available for us. So we make it available to you. More about Exporting Entertainment later.

Second, Kristin is not only a film historian but a scholar of ancient Egyptian art, specifically of the Amarna period. (These are the years of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and their highly unsuccessful experiment in monotheism.) Every year she goes to Egypt to participate in an expedition that maps and excavates the city of Amarna. In recent years she’s focused on statuary, about which she’s given papers and published articles. Now we’ve learned that she has won a Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fellowship to work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection for a month during the next academic year. So at some point then we’ll both be blogging from NYC. Think of the RKO Radio tower sending our signals to a tiny world below.

Third, she is about to turn 60, and in her honor the Communication Arts Department is sponsoring a day-long symposium. On 1 May we’ll be hosting Henry Jenkins, Charlie Keil, Janet Staiger, and Yuri Tsivian to give talks on topics related to her career interests. Kristin’s talk will survey her Egyptological work, with observations on how she has applied analytical methods she developed in her film research. You can get all the information about the event, as well as find places to stay in Madison, here.

Kristin came to Madison in 1973, a very good moment. Whatever you were interested in, from radical politics to chess to necromancy (there was a witchcraft paraphernalia shop off State Street), you could find plenty of people to obsess with you. Film was one such obsession.

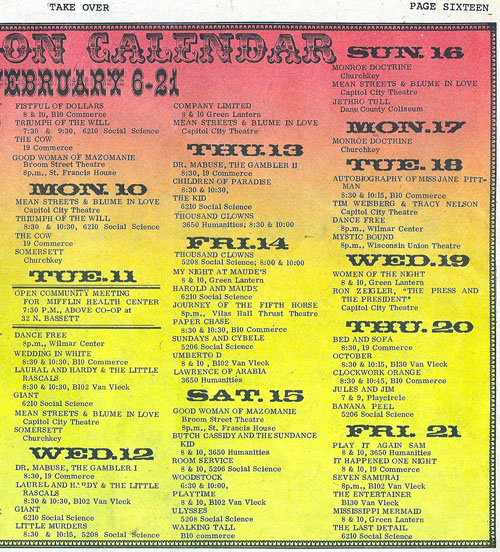

The campus boasted about twenty registered film societies, some screening several shows a week. Fertile Valley, the Green Lantern, Wisconsin Film Society, Hal 2000, and many others came and went, showing 16mm films in big classrooms in those days before home video. Without the internet, publicity was executed through posters stapled to kiosks, and the fight for space could get rough. Posters were torn down or set on fire; a charred kiosk was a common sight. Another trick was to call up distributors and cancel your rivals’ bookings. One film-club macher reported that a competitor had cut his brake-lines.

What could you see? A sample is above. What it doesn’t show is that in an earlier weekend of February of 1975, your menu included Take the Money and Run, The Lovers, Ray’s The Adversary, Page of Madness, Fritz the Cat, The Ruling Class, Dovzhenko’s Shors, Chaney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, American Graffiti, Wedding in Blood, Pat and Mike, Camille, Yojimbo, Faces, Days and Nights in the Forest, King of Hearts (a perennial), Sahara, The Fox, Day of the Jackal, Dumbo, Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, Slaughterhouse-Five, Mean Streets, A Fistful of Dollars, Triumph of the Will, and The Cow. Not counting the films we were showing in our courses.

In addition, there was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, recently endowed with thousands of prints of classic Warners, RKO, and Monogram titles. (There were also TV shows, thousands of document files, and nearly two million still photos.) When Kristin got here she immediately signed up to watch all those items she had been dying to see. She suggested that the Center needed flatbed viewers to do justice to the collection, and director Tino Balio promptly bought some. Those Steenbecks are still in use.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Above all there were the people. The department had only three film studies profs–Tino, Russell Merritt, and me–though eventually Jeanne Allen and Joe Anderson joined us. Posses of other experts were roaming the streets, running film societies, writing for The Daily Cardinal, authoring books, and editing the Light Trap. Who? Russell Campbell, John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tom Flinn, Tim Onosko, Gerry Perry, Danny Peary, Pat McGilligan, Mark Bergman, Sid Chatterjee, Richard Lippe, Harry Reed, Michael Wilmington, Joe McBride, Karyn Kay, Reid Rosefelt, Dean Kuehn, Samantha Coughlin, and Bill Banning. Most of these were undergraduates, but Maureen Turim and Diane Waldman and Douglas Gomery and Frank Scheide and Peter Lehman and Marilyn Campbell and Roxanne Glasberg and other grad students could be found hanging out with them. A great many of this crew went on to careers as writers, teachers, scholars, programmers, filmmakers, and film entrepreneurs.

Into the mix went film artists like Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, and Michelle Citron. There were film collectors too; one owned a 70mm print of 2001 and didn’t care that he could never screen it. ZAZ, aka the Zucker brothers and Jim Abrahams, were concocting Kentucky Fried Theater. Andrew Bergman had recently published We’re in the Money, and soon Werner Herzog would be in Plainfield waiting for Errol Morris to help him dig up Ed Gein’s grave. Set it all to the musical stylings of R. Cameron Monschein, who once led an orchestra the whole frenzied way through Intolerance. The 70s in Madison were more than disco and the oil embargo. (To catch up on some Mad City movie folk, go here.)

These young bravos worked with the same manic passion as today’s bloggers. The purpose wasn’t profit, but living in sin with the movies. Film society mavens drove to Chicago for 48-hour marathons mounted by distributors. Traditions and cults sprang up: Sam Fuller double features, noir weekends, hours of debates in programming committees. Why couldn’t Curtiz be seen as the equal of Hawks? Why weren’t more Siodmak Universals available for rental? Was Johnny Guitar the best movie ever made, or just one of the three best?

There was local pride as well. Nick Ray had come from Wisconsin, and so had Joseph Losey, not to mention Orson Welles (who claimed, however, that he was conceived in Buenos Aires and thus Latin American). During my job interview, Ray came to visit wearing an eye patch. It shifted from eye to eye as lighting conditions changed. When he showed a student how to set up a shot, he bent over the viewfinder and lifted the patch to peer in. Was he saving one eye just for shooting?

In the big world outside, modern film studies was emerging and incorporating theories coming from Paris and London. Partly in order to teach myself what was going on, I mounted courses centering on semiotics, structuralism, Russian Formalism, and Marxist/ feminist ideological critique.

Back in placid Iowa City, where Kristin got her MA in film studies and I my Ph.D., we grad students had seen our mission clearly. Steeped in theory, we pledged to make film studies something intellectually serious: a genuine research enterprise, not mere cinephilia. Madison was the perfect challenge. Here cinephilia was raised to the level of thermonuclear negotiation, backed with batteries of memos, scripts, and scenes from obscure B-pictures. Confronted with a maniacal film culture and a vast archive, Kristin and I realized that there was so much to know–so many films, so much historical context–that any theory might be killed by the right fact.

Watch a broad range of movies; look as closely as you can at the films and their proximate and pertinent contexts; build your generalizations with an eye on the details. Our aim became a mixture of analysis, historical research, and theories sensitively contoured to both. The noisy irreverence of Mad City, where a former SDS leader had just been elected mayor and city alders could be arrested for setting bonfires on Halloween, wouldn’t let you stay stuffy long.

Kristin’s work in film studies would be instantly recognizable to humanists studying the arts. Essentially, she tries to get to know a film as intimately as possible, in its formal dimensions–its use of plot and story, its manipulations of film technique. I suppose she’s best known for developing a perspective she called Neoformalism, an extension of ideas from the Russian Formalists. Armed with these theories, she has studied principles of narrative in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. She has probed film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and her sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. And she has examined narrative and style together in her book on Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible and the essays in Breaking the Glass Armor.

Contrary to what commonsense understanding of “formalism” implies, she has always framed her questions about form and style in a historical context. She situates classic and contemporary Hollywood within changes in the film industry–the development of early storytelling out of theatre and literature, or current trends responding to franchises and tentpole films. For her, Lubitsch’s silent work links the older-style postwar German cinema and the more innovative techniques of Hollywood. She situates Tati, Ozu, Eisenstein, and other directors in the broad context of international developments, while keeping a focus on their unique uses of the film medium.

Perhaps her most ambitious accomplishment in this vein is her contribution to Film History: An Introduction. She wrote most of the book’s first half, and though I’m aware of the faults of my sections, I find hers splendid. After twenty years of research, she produced the most nuanced account we have yet seen of the international development of artistic trends in American and European silent film.

Kristin has also illuminated the history of the international film industry. Everybody knows that Hollywood dominates world film markets. The interesting question is: How did this happen? Exporting Entertainment provides some surprising answers by situating film traffic in the context of international trade and changing business strategies. One twist: the importance of the Latin American market. The book also opened up inquiry into “Film Europe,” a 1920s international trend that tried to block Hollywood’s power. In all, Exporting Entertainment led other researchers to pursue the question of film trade, and I was gratified to see that Sir David Puttnam’s diagnosis of the European film industry, Undeclared War, made use of Kristin’s research.

More recently, Kristin has turned her attention to the contemporary industry, the main result of which has been The Frodo Franchise, a study of how a tentpole trilogy and its ancillaries were made, marketed, and consumed. Her love of Tolkien and her respect for Peter Jackson’s desire to do LotR justice led her to study this massive enterprise as an example of moviemaking in the age of winning the weekend and satisfying fans on the internet. She maintains her Frodo Franchise blog on a wing of this site.

Most readers of this blog know Kristin as a film scholar. They may be surprised to learn that she also wrote a book on P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster books. Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes; or, Le Mot Juste is a remarkable piece of literary criticism. Here she shows how Wodehouse developed his own templates for plot structure and style. Again, the analysis is grounded in research–in this case, among Wodehouse’s papers. So assiduously did she plumb Plum that she became the official archivist of the Wodehouse estate. This is also, page for page, the funniest book she has yet written.

Her Egyptological work is no joke, though, and she has become one of the world’s experts on Amarna statues. She has published articles and given talks at the British Museum and other venues. Soon she’ll trek off for her ninth season at Amarna. There, joined by her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan, she’ll study the thousands of fragments that she’s registered in the workroom seen above. It’s preparation for a hefty tome on the statuary in the ancient city.

You can learn more about Kristin’s career here, in her own words. These are mine, and extravagant as they are, they don’t do justice to her searching intelligence, her persistent effort to answer hard questions, and her patience in putting up with my follies and delusions. You’d be welcome to visit her symposium and see her, and people who admire her, in action. While you’re here, you can watch a restored print of Design for Living, by one of her favorite directors, screening at our Cinematheque. In 35mm, of course. We can’t shame our heritage.

Poster design by Heather Heckman. Check out our Facebook page too.

Sticky splices and hairy palms

Venusville (Fred Worden and Chris Langdon, 1973).

DB here:

Just as CDs gave us a taste for sterile sound, the DVD has made us prize the clean image. We like sleek, hard-edged frames that look good on computer monitors and home-theatre screens. So who would put up with a shot like the one surmounting today’s entry?

Mark Toscano, for one. He’s a film preservationist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive. Among other tasks, he searches out and preserves experimental and avant-garde cinema, particularly work from West Coast filmmakers. And he savors shots like that hairy palm.

Mark Toscano, for one. He’s a film preservationist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive. Among other tasks, he searches out and preserves experimental and avant-garde cinema, particularly work from West Coast filmmakers. And he savors shots like that hairy palm.

We normally think that someone preserving a film must at the minimum do a cleanup—remove all the specks, hairs, rips, and bad splices—before going on to more serious fixing, like correcting faded color. But what if the filmmaker left in the dirt and glue blobs deliberately? Or what if the filmmaker developed a fondness for the wear and tear that the movie accumulated over years of use? What’s a dutiful archivist to do?

The virtues of degradation

Mark is aware that archivists can have a big impact on film culture. By selecting films to save, they expand the canon and invite researchers to consider work that might otherwise be missed. “A curator’s enthusiasm can fuel new scholarship.” So part of Mark’s mission is to bring the inventiveness of lesser-known avant-garde filmmakers to new prominence.

Surprisingly, sometimes the archivist has to convince a filmmaker that work is worth saving. Robert Nelson had decided that most of his films were of little interest and in 1999 began redoing some and even destroying others. The scrapes you see on The Awful Backlash (above), a film about a tangled fishing reel, are the result of Nelson’s decision to rub out parts of the soundtrack.

Above all, a preservationist can widen the audience by programming collections like the one Mark brought to our Cinematheque last week. His Friday program was a feast of LA experimental film from the 1960s and 1970s. The menu ranged from gorgeous abstractions like Fred Worden’s Throbs (1972) and Pat O’Neill’s 7362 (1967) to exercises in dry wit like Morgan Fisher’s Turning Over (1975), about the momentous instant when a car’s odometer flips from 99,999 miles to 100,000. There was Kathy Rose’s Mirror People (1974), a sinister exercise in fairy-tale animation, headcomix-style, and Diana Wilson’s charming stop-frame still life Rose for Red (1980). One of the program’s implications was that on the Left Coast, avant-garde films were less cerebral than the official classics of the East Coast establishment. Films like David Wilson’s Stasis (1976) and Gary Beydler’s indescribable Pasadena Freeway Stills (1974) show that Structural Film could offer sheer entertainment. Mark’s notes on several of these titles can be found here.

The day before the screening, Mark gave a talk to our departmental colloquium called “Print (de)Generation.” He was paying ironic homage to our colleague J. J. Murphy’s 1974 classic, Print Generation (which Mark is restoring). But his title captures as well the problems of preserving films that don’t aim at pristine imagery.

If you assume that your job is to find the best existing form of the film and conserve that, what do you do with experimental work? Sometimes the films are designed to look messy. Sometimes they acquire a wear and tear that is like the patina on a sculpture or piece of furniture, when the signs of time’s passing become part of the texture of the piece.

Mark gave many examples of the decisions he faces in preserving the deliberate roughness of some work. Ben VanMeter (in spirit and approach, Mark feels, the most classically hippie West Coast filmmaker) corrugated the film strip of Acid Mantra; or, Rebirth of a Nation (1968). The legendary but little-seen Maltese Cross Movement (1967) by Keewatin Dewdney is a dazzling exercise in process structure, and the speckling on the images comes from creative choices. Shots were intercut with black frames—not black film frames, but frames dabbed with opaque paint. Inevitably, flakes of paint migrated across nearby footage.

Brakhage’s films call for special delicacy. Mark showed lovely photos of film strips that Brakhage had painted upon, or welded together with thick splices that look like chain mail, as in the fourth reel of 23rd Psalm Branch (1967).

The Garden of Earthly Delights (1981) incorporates bits of grass, ferns, and insect wings.

How do you preserve such a thing? Brakhage endlessly revised some of his work, and came to appreciate the flaws that reprinting shooting and editing introduced into a film. When Mark called him about eradicating a hair that had crept into Flight (1974), Brakhage replied: “That hair is the axis around which the entire film revolves.” [Please see PS at bottom of post.]

Feelthy peectures

Mark’s talk highlighted Chris Langdon, a little-known Cal Arts filmmaker who worked with John Baldessari, Robert Nelson, and Fred Worden. Worden collaborated on Venusville, (1973), a deadpan satire on Structural Film. Shots of a palm tree tremble in front of us, while we hear puzzled comments from offscreen filmmakers. The image gets grubbier as the film proceeds, as if the viewers were looping it in their search for clues.

Langdon’s work vividly displays the West Coast impulse to hold nothing sacred. You would think that the endlessly self-ironizing Warhol was beyond teasing, but Bondage Boy (1973) makes a good try. We see a fellow wrapped in plastic and chains and struggling half-heartedly while assuming some fairly un-erotic postures. The soundtrack is “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” Langdon made fifteen to twenty films per year in a great many styles, and even created trailers for some of them, including Bondage Boy. She also came up with trailers for unmade films, as in Love Hospital Trailer (1975; above).

Mark’s passion and persistence brought Langdon’s films back to notice very recently, at a Redcat retrospective curated by Mark, Steve Anker, and Bérénice Reynaud. “I guess I was just a little incredulous that anyone would remember those films, and a little wary about it, to be honest,” said Langdon, who now prefers to be known as Inga. “But after a while, I thought it was pretty cool.” Scholars will be lining up to write about her work, with its wild humor and ties to Structural and Punk cinema.

You might not expect the Academy to preserve avant-garde cinema, but it’s a great testament to the institution that it cares so much about all kinds of film. Mark generously praised his colleagues Mike Pogorzelski and Joe Lindner (both Wisconsin alums), who support his efforts. In turn, we’re grateful to people like Mark who devote themselves to recovering films in a way that respects filmmakers and their work—especially when that work seems defaced or distressed. He teaches us that imperfections aren’t always faults. Everything in the world spoils eventually. Why shouldn’t artists acknowledge that? No surprise to learn that Mark owns few CDs but hundreds of LPs. He’s a master in bringing the Vinyl Aesthetic to film.

Mark Toscano keeps a blog titled “Preservation Insanity,” with more images of despoiled imagery, here.

Film preservation and restoration have formed a running thread for Kristin and me, from our trips to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato to our reportage on visits from archivists like Grover Crisp.

Currently there’s a blogathon on preservation sweeping the Internets. You can read about it at the Self-Styled Siren and Ferdy on Film, both of whom are keeping running tally on the entries. Please consider contributing to the National Film Preservation Foundation.

You can read more about the West Coast experimental tradition in David E. James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005) and Chapter 6 of Paul Arthur’s A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

PS 19 February: Marilyn Brakhage posted this correction to the Frameworks listserv (ellipses in the original):

I’m glad to see Mark’s work getting some more, deserved attention. However, after reading the blog (which I can’t seem to respond to directly) just thought I’d mention — for the sake of historical accuracy — that the comment from David Bordwell that “Brakhage endlessly revised some of his work . . . ” is simply not true. When a work was done, it was done, and he moved on. He did not re-make/re-edit old work like some filmmakers do. . . . Perhaps Mr. Bordwell was thinking of the inevitable problems in print variation coming through the labs over the years (that the filmmaker, of necessity, had to adjust to), or the “translations” that resulted from blowing up 8 mm to 16 mm versions for distribution purposes. But I wouldn’t call that “revising” his work. (I’m sure he wanted the “translations” to be as true as possible to the original.) . . . And the hair that had “crept into Flight” was there from the beginning — accepted and used by Stan when he began to edit the film. It wasn’t something that happened over time.

I regret my misunderstanding of Mark’s remarks on the subject, and I’m grateful to Marilyn for setting the record straight.

Robert Nelson’s painted and resin-sealed cans of film. Another approach to preservation? Images courtesy Mark Toscano.

Paris fun, in at least three dimensions

What he saves films from: Serge Bromberg faces down the flames.

We’re ending the first week of three in Paris. At the invitation of Jean-Loup Bourget and Françoise Zamour, David is giving three weekly lectures at the École Normale Superieure. He’s introducing some ideas about the development of film style in the 1910s and early 1920s, updated with new material from his summer research in Denmark and Brussels. Jean-Loup and Françoise have proven excellent hosts, and the first lecture seemed to go well.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

Turns out, though, that it is still warmer than Madison, which is having highs in the single digits, as the weather forecasters say, and lows below zero. We’re better off here, though we wish we had brought our parkas.

It’s like Avatar, but much shorter

KT here:

The cold has driven us indoors, to museums and movies. As always seems to be the case, the Cinémathèque Française is hosting retrospectives of American films—in this case works by Laurel and Hardy and Gordon Douglas. There’s also a 3D series, which caught our attention right away. It’s not just your standard Kiss Me Kate and Dial M for Murder programming. In addition to such classics, there are many obscure films. We happened to arrive in time for the final two programs of the series, which ran from December 16 to January 3.

Our first full day in Paris ended with an evening of shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who in 1985 founded Lobster Films. Lobster has put out many DVDs by now, some of which we have reported on previously, here and here. In July, one of our entries on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna mentioned that Serge presented a program of Georges Méliès films, in conjunction with the French release of Lobster’s huge DVD set of the great magician’s films.

Serge is quite a showman and obviously a popular figure, since there was a large crowd, including many families with children. On Saturday he chose and introduced a set of short 3D films in his series of programs usually titled “Retour de Flamme,” or “Saved from the Flames.” To begin the evening’s entertainment, he explained how, unlike modern celluloid 35mm film, the nitrate variety used up until the early 1950s ignites and burns easily. With the help of a rightly apprehensive volunteer holding up a film-can lid, Serge showed how modern celluloid catches fire only briefly and then dies out. The few inches of nitrate, however, flared up quickly.

Serge introduced each film thereafter, playing the piano to accompany the silents. The audience had been given both anaglyph (red-green) and polarized glasses, and Serge’s introductions to the films gave us time to switch between systems.

Many of the shorts shown on the program are available on DVD or YouTube, but the 3D effect plays best on the big screen. The evening began with an unannounced item, Three Dimensional Murder, a “Metroskopics” comedy short from 1942. A nervous detective visits a mysterious house and encounters Frankenstein, creeping hands, skeletons, and other ghouls and beasties, all of which find some occasion to throw things or hurl themselves toward the camera. The humor is, as a contemporary audience member might have said, pure corn and the 3D effects repetitive, but it was certainly a rare item.

Next came one of the Fleischer brothers’ cartoon shorts, Musical Memories. It was made with a patented system that used three-dimensional models as settings against which 2D cartoon figures drawn on cels moved about. (Such models can be seen fairly often in Popeye and other Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s.) There is some sense of depth. Still, the effect is strange, since the models have shading and the flat-looking figures do not. The cartoons are not 3D in the sense we typically think of, since there are no glasses involved.

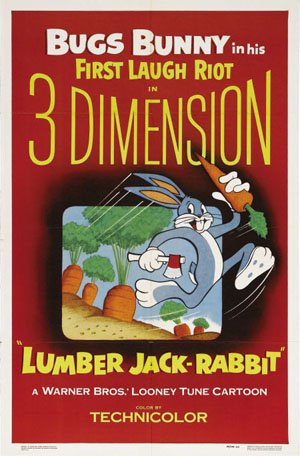

More cartoons followed, from the two main competing animation studios. Disney’s contribution was Working for Peanuts, a story set in a zoo with Chip and Dale stealing peanuts from an elephant and Donald Duck trying to foil them. Many a peanut seemed to fly out toward the spectator. Chuck Jones directed Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1954), a film that mixed size gags and spatial ones, with Bugs wandering into the domain of the gigantic Paul Bunyan. Perhaps not one of Jones’s best, but distinctly more interesting in 3D.

As Serge pointed out, most 3D technology was pioneered in the U.S. He included some exceptions, however, with a series of Soviet “Parade of Attractions” shorts shown at intervals during the evening. Experiments with underwater 3D photography and a garden of plants lacked soundtracks, but the final item, a vaudeville act with jugglers, had music and lots of bowling pins flying at the camera.

Unbelievably, there were efforts toward 3D as early as 1900. Serge showed some 3D experiments from that period by inventor Rene Bunzli. These were only about 10 seconds long and included a mildly risqué scene of a man arriving to visit his mistress and another discovering his wife in bed with her lover. The first color 3D film was shown: Motor Rhythm, made by Charley Bowers in 1940 for the Chicago Exposition and distributed by RKO. Using a combination of pixilation and 3D, the film shows a car jauntily assembling itself to a musical accompaniment, with many of the parts moving out toward the camera before attaching themselves in their proper places.

The National Film Board of Canada contributed Munro Ferguson’s Falling in Love Again, with characters wafted into the sky by road accidents and, while falling, falling in love. To watch it in high-quality 3D, go here. Pixar was represented by John Lasseter and Eben Ostby’s early digital experiment in 3D, Knick Knack, as a snowman trapped in a snow globe tries to break free to join a bathing beauty.

The evening ended with a surprise, two films that had never been meant to appear in 3D.

Méliès’s early shorts were often pirated abroad, and a lot of money was being lost in the American market in particular. After the Lubin company flooded that market with bootleg copies of a 1902 film, Méliès struck back by opening his own American distribution office. Separate negatives for the domestic and foreign markets were made by the simple expedient of placing two cameras side by side. The folks at Lobster realized that those cameras’ lenses happened to be about the same distance apart as 3D camera lenses. By taking prints from the two separate versions of a film, today’s restorers could create a simulated 3D copy!

Two 1903 titles–I think that they were The Infernal Cauldron and The Oracle of Delphi–triumphantly showed that the experiment worked. Oracle survived in both French and American copies, and the effect of 3D was delightful. For Cauldron only the second half of the American print has been preserved. Watching the film through red-and-green glasses, you initially saw nothing in your right eye, while the left one saw the image in 2D. Abruptly, though, the second print materialized, and the depth effect kicked in. The films as synchronized by Lobster looked exactly as if Méliès had designed them for 3D.

Film scholars gone wild

DB here:

William Cameron Menzies is most famous as an art director on films like The Thief of Baghdad (1924) and Gone with the Wind. He was one of the most visually daring artists to work in classic Hollywood; his eccentric framings and looming foregrounds may have influenced Orson Welles. (The Gothic distortions of Our Town and Kings Row are unlikely to be the creation of director Sam Wood.) Menzies also directed a few films, most notably the slightly nutty anti-Commie film The Whip Hand (1951).

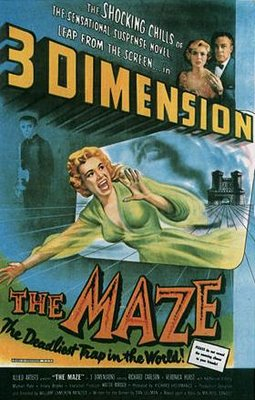

So Kristin and I had to go back to the Cinémathèque for Menzies’ rarely-seen 3D feature The Maze (1953). Alas, it was a washout. The feeble story concerns an heir returning to a castle to confront a giant frog, who may be his relative. I’d expected bravura deep-focus, with planes jutting out at me, but the film was dramatically and visually flat–no wordplay intended. The trailer, complete with fake bats on strings, is here.

We have other incidents to chronicle, but this dispatch can end with a quick list of some of the film friends we’ve encountered. We’ve already mentioned Professor Bourget, whose book on Fritz Lang came out recently (below left). We also ran into Cindi Rowell, an old friend from Pordenone and The Griffith Project, who had the excellent idea that we go to Chinatown–here hidden behind the facades of tower blocks. Cindi has vast experience in many aspects of film culture–preservation, programming, publication, web design, and the like–and is currently affiliated with the Middle East International Film Festival in Abu Dhabi.

Another old friend, Yuri Tsivian, is in Paris teaching during our visit, so we had a chance for a good dinner and lots of talk about editing in the 1910s. Below, he and Kristin pay homage to one of the shrines of Parisian cinephilia, the Studio des Ursulines movie theatre.

Left: Jean-Loup Bourget and his new book on Lang. Right: Yuri and Kristin at the Urselines.

Last night, with Kristin away in Berlin, I went to a dinner hosted by Jacques Aumont and Lyang Kim. Jacques is a major film theorist, whose many books and essays probe into the artistic qualities of cinema. His book on Eisenstein is available in English translation, as is his far-ranging study of the history and functions of images. Lyang is an outstanding photographer, whose book of haunting Christmas images Dans l’ombre de noël was just published in December. Among her pictures here are some gorgeous “fusion” images that recall our recent 3D experiences.

Then who should turn up but Marc Vernet and Rick Altman? It was an Iowa-Wisconsin reunion in the 10th. Marc is an expert on film noir, on cinematic images of absence, and on the American film company Triangle–associated with both Griffith and Ince. (Again, the 1910s.) Marc has set up a beautiful webpage full of information about early American cinema, and he blogs there frequently. Rick is known for his in-depth studies of film genre (especially the musical), film sound, and narrative theory. His most recent books, Silent Film Sound and A Theory of Narrative, are splendid contributions. Below, all four toast what turned out to be Rick’s birthday.

Today: More preparations for my lecture tomorrow, and of course at least one movie. Agora? Wiseman’s La Danse? Kinatay? The new Eugène Green, La religieuse portugaise? Or a rerelease (new print) of Minnelli’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? Or….? The usual Parisian problem, but a good problem to have.

P. S. March 2010: After this Paris trip, I wrote an essay on William Cameron Menzies for this site.

Jacques Aumont, Lyang Kim, Rick Altman, and Marc Vernet, 9 January 2010.