Archive for the 'FILM ART (the book)' Category

Watching movies very, very slowly

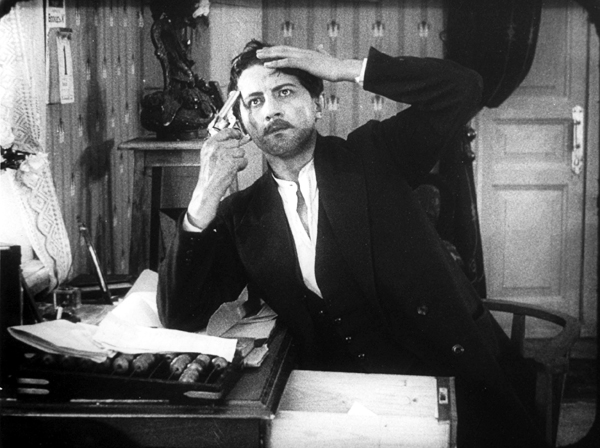

Children of the Age (1915).

DB here:

Before DVD and consumer videotape, how could you study films closely? If you had money, you could buy 8mm or 16mm prints of the few titles available in those formats. If you belonged to a library or ran a film club, you could book 16mm prints and screen them over and over. Or you could ask to view the films at a film archive.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

At first archives found it easier to screen films for researchers in projection rooms, but eventually many let visitors watch the films on stand-alone viewers. That way the researcher could stop, go forward and back, and take notes. In researching my dissertation in the summer of 1973, I watched films at George Eastman House in 16mm projection, but a few weeks later in Paris, Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Francaise allowed me time on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse (a term I’ve admired ever since).

Over the years Kristin and I have visited archives in various countries. We’ve become particularly close to the Royal Film Archive of Brussels, partly because back in the 1980s the head, Jacques Ledoux, believed that Kristin’s research was worthwhile and allowed us to visit regularly. Without the cooperation of Ledoux and his successor Gabrielle Claes, we couldn’t have done a great deal of our research. No wonder it helped us so much: the Belgian Cinémathèque is arguably the most diverse archive in the world.

Case in point: My current visit. I came with two goals. First, I had to prepare for my lectures in Bruges later in the month. These consist of eight talks on anamorphic widescreen. So I planned to watch four early CinemaScope films, plus Oshima’s The Catch (1961) and the SuperScope version of While the City Sleeps.

I also wanted to fill in a big gap in my knowledge about a major silent filmmaker. More on him shortly.

Viewing on a visionneuse

If you’ve never watched a film on a viewer, let me explain. The classic viewer is a flatbed, or viewing table. It’s the size of an executive desk. Two platters or spindles hold a feed reel and a take-up reel. Motors drive the film through a series of sprocketed gates, past a projection device (usually a prism) and across a sound head. The film appears on a smallish screen. There’s usually a little surface space to set a notepad, along with a lamp on an articulated arm.

Before digital editing came along, such machines offered the only way filmmakers could cut sound and picture. (Now most phases of editing are done on computer, with physical editing reserved for late stages of postproduction.) Eventually flatbeds were offered in simpler versions for playback rather than editing.

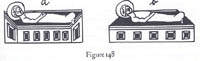

The most common American-made viewer was the Moviola, which was initially not a flatbed but an upright machine. Eventually the German Steenbeck and KEM became the high-end standards for editing picture and sound. The Brussels archive relies on the Prévost, an Italian machine that is very easy to maintain. The Prévost, seen above, beams the image from the prism onto a mirror hanging over the machine, which bounces the picture onto the screen.

35mm films are mounted on 1000- or 2000-foot reels, the latter yielding about twenty minutes of film at sound speed. A feature film will consist of four or more 2000-foot reels. Even if you watch a film straight through, without stopping to make notes, it takes time to change the reels, so a two-hour movie will probably consume nearly three hours on a 35mm flatbed. And of course researchers stop a lot to take notes and move to and fro across a scene. If I’m studying a film intensively, I probably consume about an hour per 2000-foot reel. Across my life, I wouldn’t dare calculate how many months I’ve spent in visionneuse viewing.

Viewing on an individual viewer has both costs and benefits. Sometimes details you’d notice on the big screen are hard to spot on a flatbed. But with your nose fairly close to the film, you can make discoveries you might miss in projection. (Ideally, you would see the film you’re studying on both the big screen and the small one.) In addition, of course, you can stop, go back, and replay stretches. Above all, you get to touch the film. This is a wonderful experience, handling 35mm film. Hold it up to the light and you see the pictures. You can’t do that with videotape or DVD.

The scary part of any flatbed viewing, at least for me, is watching the film whiz along under your nose at ninety feet per minute. If you haven’t threaded the thing properly, or if the print has a weak splice or torn sprocket hole, you can rip the film. For this reason, archives typically don’t allow a researcher to handle films they hold in only one copy.

The average film you watch on a flatbed has an optical soundtrack, that squiggly line that is read by an optical valve. But early CinemaScope films had magnetic tracks so that they could provide stereophonic sound. In the picture below you can see that strips of magnetic tape, like those in tape cassette players, run along both edges of the film strip. For my Scope films, I was obliged to use a Prévost that could handle mag sound–and of course one that could be fitted with an anamorphic lens to unsqueeze the image to the proper proportions.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1954) was a color movie, but this print, like many from the period, has faded to bright pink. The Eastman color stock of the period was unstable, and many prints were processed carelessly. (In unsqueezing the frame, I’ve eliminated the color cast for better clarity.) Restoring color to films of this period is one of the major tasks facing film archivists. Cinema is a fragile art form.

Hours and hours of Bauers and Bauers

At the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in 1989, Yuri Tsivian’s retrospective on Russian Tsarist cinema convinced a lot of us that good filmmaking in that country didn’t start with the Bolshevik revolution. Along with that retrospective came a wonderful book, Silent Witnesses, edited by Yuri and Paolo Cherchi Usai. Unfortunately hard to find now, it’s filled with information about pre-Soviet filmmaking.

Although I enjoyed the Tsarist films, I didn’t know exactly what to watch for. It took me some years to appreciate their artistry, and some of my ideas about them showed up in On the History of Film Style (1997) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). In those places I studied 1910s “tableau” staging and used some examples from Yevgenii Bauer, by common consent the most pictorially ambitious Russian director of the period. Kristin and I also used Bauer as an example of tightly choreographed mise-en-scene in Film Art (p. 143). I thought it was time I examined his work more systematically, and I knew that the Royal Film Archive held some Bauer prints, which they acquired from Gosfilmofond of Moscow.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Although he made comedies, Bauer is most famous for his somber psychological melodramas, often centering on class exploitation. A woman becomes a rich man’s mistress; when she abandons her husband and takes their baby, he commits suicide (Children of the Age). A serving maid is seduced by her master and callously tossed aside when he marries a flirt (Silent Witnesses). Things can get pretty dark. This is the director who made films entitled After Death (1915) and Happiness of Eternal Night (1915). In Daydreams (1915), a widower sees a woman who strikingly resembles his dead wife. Like Scottie in Vertigo, he follows her and becomes increasingly obsessed. Did I mention that he keeps a ropy braid of his dead wife’s hair in a glass box?

Seeing several films again confirmed my view that Bauer knew better than most directors how to organize a shot. His contemporary Louis Feuillade favored a quiet, sober virtuosity, but Bauer developed a flashy visual style. He’s most known for his ambitious use of light (Frigid Souls, below) and big, textured sets packed with columns, trellises, drapes, brocades, embroidered pillowcases, and other elements that add abstract patterns to a scene (Children of the Age, below).

Even a hammock can be stretched and framed to create a swooping web around the innocent heroine of Children of the Age, ensnared by the demimondaine.

In particular, I admire Bauer’s constant inventiveness in moving his actors around the set in smooth ways that always direct our attention to what’s happening at the right moment. European directors of this period seldom cut up a scene into several shots of individual actors; the frame typically shows us the entire playing space. Directors were obliged to shift their actors across the frame and arrange them in depth, like chesspieces.

This master-shot, single setup approach might seem hoplelessly restrictive. Today we expect films to have lots of cutting and camera movement. How does the filmmaker sculpt the action, moment by moment within a static frame?

Blocking, as in blocking the view

I trace some principles of this approach in the books I already mentioned. I’ll mention two strategies here, and if you want to know more you can follow up in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light.

Filmmakers of the 1910s created intricate choreography by moving actors left or right, up to or away from the camera. Often they set up unbalanced compositions and then rebalanced them, creating a kind of spatial tension that parallels the drama. In the course of the action, actors close to the camera might conceal those that are farther away. The blocking of the actors, in other words, also sometimes blocks our view.

In Leon Drey (1915), Bauer tells the story of a cynical womanizer. In one scene, he’s dallying with his latest conquest when another of his lovers bursts into his apartment. The first phase of the shot is very unbalanced; most directors would have put the mistress at the door on one side of the frame and Leon and the woman in his arms at the opposite side. Immediately, though, the woman flees to the bed in the back of the shot and activates the right area of the frame.

As the mistress rushes to the woman in the rear, Leon strides to the foreground and his burly body blots out the drama between the two women. We’re forced to concentrate on his cold indifference to both of his lovers. Eventually his mistress comes to the foreground to remonstrate with him. Now, at the high point of the scene, we have a balanced frame. Note that Leon continues to conceal the first woman; the scene’s not yet about her.

The mistress leaves, angry and desperate, and Leon placidly pays her no mind. As the door closes, he hurries to lock it and summons the first woman, now visible, back from his bed. He will have little trouble convincing her to return to his arms.

The dramatic curve of the scene has been expressed in compositional asymmetry and symmetry, concealing space and then opening it up.

Most directors of the period used principles like these to turn dramatic conflict into vivid choreography. Bauer also tried more unusual tactics. He was especially good at shifting actors’ heads very slightly to open or close off channels of action behind them. Here’s an instance from Her Heroic Feat (1914).

The butler informs Lina and her mother that the scandalous ballerina Klorinda is calling on them. At first Lina’s head is solidly blocking the doorway in the rear. As the butler goes to the rear door, Lina pivots a little to clear our view of that doorway.

Klorinda sashays in, and who could miss it? She’s wearing a bright dress, she’s centrally positioned, and she’s moving toward us. The other women refuse to look at her, but their immobility assures that we keep our eye on Klorinda. When she stops to greet them, then they move, pivoting away; Lina’s head goes back to blocking the doorway. Imagine how things would have gone if her head had been there when Klorinda appeared in the background.

Of course, we should also study the performance techniques of Bauer’s actors–a subject examined in a fine book by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema. The compositional tactics employed here work to draw our attention to the actors’ expressions and body language.

Still, not everything in 1910s ensemble staging owes a debt to the theatre. The changes in Lina’s head position, or Leon Brey’s calculated blockage of the women behind him, wouldn’t work on the stage; most of the audience wouldn’t see the exact alignment we get onscreen. Live theatre depends on varying sightlines, but in cinema, we all see the action from one position, that of the camera. Bauer, Feuillade, and their contemporaries realized that they could organize the action, down to the smallest detail, around what the camera could and could not take in.

The fluent choreography developed by 1910s directors is almost unnoticeable when you’re watching in real time. You’re supposed to register the what–the point of interest in the frame–rather than the how, the slight shifting of actors that highlights this face, then that gesture. By the time you realize that something has happened, the first stages of the process have slipped away, inaccessible to memory.

So there’s a need for slow viewing. Filmmakers have thousands of secrets, many that they don’t know they know. Sometimes we have to stop the movie, go back, and trace precisely how directors achieve their effects. Really slow viewing can help us discover how deep film artistry can be. All hail the visionneuse and the archives that allow scholars to use her.

For background on Bauer, see William M. Drew’s excellent career survey. I discuss Bauer’s relation to narrative painting in another blog entry.

In production and distribution of the period, the titles and inserts (close-ups of newspapers or messages) were sometimes stored on separate reels. In many cases, only the image reels have survived.

Several other Bauer films are available on Milestone’s invaluable DVD set Early Russian Cinema.

Christian Bale picks up a rail

DB here:

In James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma, some law officers are taking the captured killer Ben Wade (Russell Crowe) to the farmhouse of Dan Evans (Christian Bale). When the stagecoach sinks into a rut, Evans limps out of his house, snatches up a fence rail, and uses it to pry the wheel free.

Not an earth-shattering moment, but one I got to know pretty well last week when I visited the mixing session as the director’s guest. About a year ago, Jim sent me an email expressing his liking for my book The Way Hollywood Tells It. We kept corresponding through the planning and production of Yuma, and last month he asked me if I wanted to see the picture-locked film and visit a sound mixing session.

As we say in Wisconsin: You bet.

Watch their eyes

Mangold has been prolific, turning out seven films in about twelve years. Heavy, CopLand, Girl, Interrupted, Kate and Leopold, Identity, and Walk the Line nicely illustrate the difference between convention and cliché. While embracing each genre’s conventions, Mangold always tries to enlarge, enrich, and explore them. Where other directors try for brute impact, he seeks out implication and understated lyricism. Above all there are the nuanced performances, female ones in particular. (Remember those Oscars for Angelina Jolie and Reese Witherspoon.) If anybody can bring the psychological nuances of that elusive “indie sensibility” to mainstream filmmaking, James Mangold is a likely candidate.

As a writer-director, he balances concern for story and character with a carefully wrought visual style. The opening of Heavy makes a shabby tavern beautiful through precise compositions and geometrical cutting that recall Ozu, whom Mangold has acknowledged as an influence.

At the same time, he has understood one of the great strengths of the Hollywood tradition—letting the actors’ faces tell as much of the story as possible. He believes that the script should include not only dialogue but also “pieces of silent acting.” John Ford remarked of actors: “Watch their eyes.” Mangold’s version of this precept can be found on the DVD commentary of Girl, Interrupted: “Actors dance with their looks and glances.”

In fact, his commentary tracks are gold. Anybody who wants to know more about the craft of writing and directing should simply sit down and listen. Mangold is not one of those I-do-what-I-feel guys; he channels the story’s feeling into precise, writable and filmable moments, and his commentary tracks explain how he does it.

Delmer Daves’ original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) is one of Mangold’s favorite films, as he explained several years ago in the interview with Tod Lippy that prefaces the published screenplays of Heavy and CopLand. He’s been bold enough to remake it, in an era in which Westerns are supposed to be unpopular. I was keen to see what a director renowned chiefly for intimate psychological dramas would do with a Western. Yet maybe the gap isn’t so great after all. Mangold points out in the Lippy interview that most classic Westerns aren’t action pictures but character studies.

In the shadow of John Ford

The Yuma production has been chronicled elsewhere on the internets, so I won’t rehearse it here. I came in on the third day of mixing. The session was held on the Twentieth Century Fox lot, at the John Ford theater (a lucky spot, surely). Mangold, his editor Mike McCusker, and half a dozen sound specialists had already been working through the morning. The team included the lauded sound rerecording mixer Paul Massey, winner of three BAFTAs and recipient of five Oscar nominations. His work includes Nixon, Clueless, Gattaca, Jerry Maguire, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, the second and third Pirates of the Caribbean films, and not least, the wonderful SCTV parody The Last Polka.

For me, it was an intensive four-hour seminar. Once I start to focus on a movie soundtrack, I have to marvel at the level of precision you can find. As we tell our students: It’s hard to really watch a movie, but even harder to really listen to it.

When Jim asked if I’d sat in on a mix before, I had to confess that I’d visited only one—a session in which Walter Murch was blending rustling foliage and mosquito noises for a scene in Apocalypse Now. (Must blog about that some day.) Things had changed a lot since the 1970s. No longer was a scratchy black-and-white print run and rerun; now we get a 4K image on a large screen, crisp and bright and frozen on a frame for as long as you like. Now there are several mixing stations, each one with a glowing Mac monitor alongside.

The standard division of labor endures, but it’s much more refined. Music is filed on many tracks and with a few mouseclicks can be reworked in tempo, timbre, and orchestration. The dialogue tracks consist of thousands of stored line readings, ready to be pulled up in moments. As for sound effects, at this point Yuma had 96 effects tracks, each of them already premixed from many sources. I usually notice the impact that the digital revolution has had on camerawork and editing, but this session really drove home to me the ways in which the computer has made the art of the soundtrack more exact and exacting.

Details, details

Most of the session was devoted to effects. The first problem was that the track seemed to Mangold too “absent,” too thin and empty. Mike remarked that he didn’t feel the atmosphere, the air between the more discrete noises. “There’s nothing of any character that’s holding it all together,” Mike said. The difficulty, though, as Jim pointed out, is that if you simply add in more sounds, you can confuse things. “If we hear just one moo, that becomes an event.” How to thicken the acoustic atmosphere without muddying it or creating competing noises?

Step by step, the team filled in the ambience. They added tiny air currents, always seeking to avoid what Mangold called “radio wind.” We got very soft and distant moos, shifting horse hooves, even low “horse vocals.” After it was all blended, I found the ambience full and modest, but Jim and the others felt that it was still too bright. They would go back later and mute it a bit.

Now that the ambience was fleshed out, the rest of the session was devoted to specific effects and a few lines. Jim asked for a heaving sound as the stagecoach burst out of the rut, more jingling on the coach reins, a little clinking on Russell Crowe’s handcuffs, a gun-cock. When Crowe’s henchman (Ben Foster), watching from the ridge, urges his horse to move, he makes a smootchy tsk-tsk; Mangold wanted to give it a slightly mocking edge, suggesting the killer’s disdain for the guards’ efforts to protect Wade.

During the 1990s I’d noticed the greater detailing of movie soundtracks. I heard garments brushing against sofas and flakes of tobacco crackling when someone lit a cigarette. Now I was seeing and hearing how skilled artisans orchestrated thousands of such sonic micro-events. They clarified a muffled line. They inserted the sound of stagecoach springs shifting. The words “Good luck” were shifted eight frames. At one point Jim asked for a new line to be put in. “We need a ‘Let’s go.'” “Should I steal it?” “Steal it.” How much of this would be heard in the typical multiplex, or even in fancy home theatres? These guys were going all the way down, creating something of great finesse.

Jim reminded me that sound can create a sense of visual momentum too. The coach drives off in two shots, a long shot and an extreme long shot, and Mangold thought it seemed to go a bit faster in the second. So he added noise that gave an accelerating launch to the first shot.

Then there were Mr. Bale’s steps and the rail he picks up, which gave me an acoustic hallucination.

David is hearing things

As Dan Evans limps out of the cabin (he was wounded in the war), Jim found his footsteps too thudding. He wanted to hear that they were “grounded,” that there was some loose earth underfoot. The team worked to add the textures of pebbles and grit as Evans makes his way to the coach. The action was replayed many times. As the texture thickened, the fence rail that Evans grabs started to sound different to me. At first it was a soft but distinct scrape against the ground; at the end of the mix, it had a faintly twangy timbre. I congratulated the team on giving the rail its own little moment.

They looked at me. They hadn’t done a thing to the rail.

Two explanations arise, maybe both correct. (1) The sound team said that constantly replaying a clip can create such little mirages. Faced with so much repetition, maybe the mind needs to project some variation into it. (2) Changing the texture of the whole scene can alter our sense of the individual, unchanged elements. If there was a little twang to the rail, perhaps it came from overtones or other emergent qualities of the mix.

Maybe too, in my third hour of concentrating on minutiae of the track, I was getting oversensitive to sound.

Realism and convention

After the stagecoach drives off, Wade and the men guarding him trudge into Evans’ cabin. There’s a short scene with Wade and his wife, and that too needed its ambient filling in. I noticed that the banker, first glimpsed inside the cabin, is somewhat closer to the couple a few shots later. Jim noticed it too. In a jiffy three or four very soft bootsteps and slightly creaking boards were added, so that subliminally we were prepared to see the banker on the porch.

Night falls and two of the men guarding Wade are lingering on the cabin porch. It was simple dialogue, filled out with the atmospheric sound. The sound mixers had to redo one actor’s line reading, yanking an alternative out of the files. Jim still wasn’t satisfied and thought they might reloop the line later. Most interesting was Jim’s idea to add some softly clinking dishes to the tail of the scene, preparing us for the cut inside to Evans’ family at dinner with Wade. In these ways, barely perceptible sound smooths over cuts and shifts of point-of-view.

In the course of all this, as Paul and Mike and the others were fixing things, Jim came back to talk with me. He answered my questions and we chatted about directors, mostly Spielberg. Close Encounters is a favorite of his, and he pointed out ways in which it’s been influential on a range of other movies. He also showed how aware he is that realism in sound goes only so far and that pure conventions often kick in. In a movie, when somebody hangs up a phone abruptly, the person on the other end hears a dial tone. Does that ever happen in life? You just get silence. But the dial tone conveys a stronger sense that the line has been broken.

In the course of all this, as Paul and Mike and the others were fixing things, Jim came back to talk with me. He answered my questions and we chatted about directors, mostly Spielberg. Close Encounters is a favorite of his, and he pointed out ways in which it’s been influential on a range of other movies. He also showed how aware he is that realism in sound goes only so far and that pure conventions often kick in. In a movie, when somebody hangs up a phone abruptly, the person on the other end hears a dial tone. Does that ever happen in life? You just get silence. But the dial tone conveys a stronger sense that the line has been broken.

Jim halted the session as the family dinner scene began. The team would continue to polish it, and he’d be back tomorrow to keep going. I snapped a picture of him just before he left. Later, I caught up with Mike McCusker, who also edited Walk the Line. He has an enormous respect for Mangold, saying that his success with female performers was reminiscent of Cukor’s accomplishments.

Next day, watching the premix version of the whole movie, I saw Christian Bale limp thuddingly to the coach. Almost no moos or jingles, and definitely no clinking crockery. No twang when he picked up the rail. You almost never get a chance to notice this sort of before-and-after differences on soundtracks, and it brought home to me how much skill and effort would go into reworking every scene. Making movies is really, really hard work. And I remembered another reason I like movies: They sharpen your senses.

Coming attractions

I plan to write more on 3:10 to Yuma in a few days. In the meantime, Kristin may be posting her experience at another mixing session–that one in Wellington, New Zealand in May. Over the next week we’ll also be filing reports from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. Sign up for a feed if you want to keep abreast of developments.

Simplicity, clarity, balance: A tribute to Rudolf Arnheim

DB here:

On Monday, at age 102, Rudolf Arnheim died. You can read his obituary here, and this is a lovely website devoted to his work. He was one of the most important theorists of the visual arts of the last century, and he had enormous impact on how people, including Kristin and me, think about film.

A good Gestalt

In parallel with E. H. Gombrich, who died in 2001, Arnheim brought modern psychological concepts into the study of visual art. His most famous work, Art and Visual Perception (1954, new version 1974) has the sort of magisterial presence that very few books in any era achieve. Arnheim delighted in the fact when, visiting a painter’s studio, he would find a spattered copy on the workbench. Of the revised edition, entirely rewritten, he noted:

All in all, I can only hope that the blue book with Arp’s black eye on the cover will continue to lie dog-eared, annotated, and stained with pigment and plaster on the tables and desks of those actively concerned with the theory and practice of the arts, and that even in its tidier garb it will continue to be admitted to the kind of shoptalk the visual arts need in order to do their silent work (new ed., x).

He aimed at theory that actively participates in the way artists do their job. The chapter titles of Art and Visual Perception deal with the nuts and bolts of picture-making: Balance, Shape, Form, Growth, Space, Light, Color, Movement, Dynamics, and Expression. No puns, slashes, dashes, or parentheses. What academic theorist today would so boldly announce their concern with the craft of creating images?

The book is subtitled, A Psychology of the Creative Eye, and the chapters’ subsection titles explain why. The hidden structure of a square . . . Vision as active exploration . . . Perceptual concepts . . . What good does overlapping do? . . . Why do children draw that way? . . . Gradients create depth . . . Visible motor forces . . . The priority of expression. Arnheim’s principal achievement in art theory was to integrate the Gestalt theory of perception with the traditional concerns of picture-making. He sought to show how perceptual laws discovered in the psychological laboratories of Berlin were intuitively applied by classic and modern artists.

As he put it, he was at the university at around age twenty:

My teachers Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler were laying the theoretical and practical foundations of gestalt theory at the Psychological Institute of the University of Berlin, and I found myself fastening on to what may be called a Kantian turn of the new doctrine, according to which even the most elementary processes of vision do not produce mechanical recordings of the outer world but organize the sensory raw material according to principles of simplicity, regularity, and balance, which govern the receptor mechanism.

This discovery of the gestalt school fitted the notion that the work of art, too, is not simply an imitation or selective duplication of reality but a translation of observed characteristics into the forms of a given medium (Film as Art, 3).

The Gestalters thought that these principles–figure/ground, completeness, good continuation, and the like–were fundamental to all human perception, across times and cultures. Art and Visual Perception makes a powerful case for this view. Today this position is so unfashionable that Arnheim’s calm confidence in it is quite stunning. For many scholars today, all that matters is what divides and differentiates us. But for eighty-plus years Arnheim emphasized ways in which we share a common experience of the world and of art.

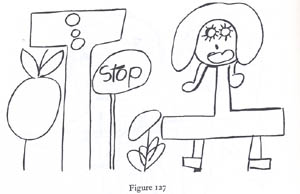

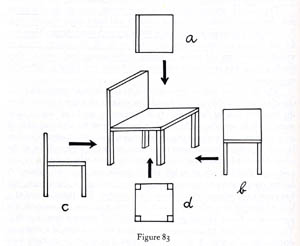

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

Arnheim saw the same form-giving activity at work in “primitive” art, the art of children, and even the art of the mentally ill. It turns out that the “universalism” of Gestalt theory underwrites diversity no less vigorously than the most ardent postmodernism.

Flexible striving

Arnheim made another contribution to our thinking about art, one that I think is rarely recognized. In a bold stroke, he extended the Gestalt conception of form beyond its concern with geometrical qualities and argued that form was inherently expressive. A triangle resting on its base wasn’t just balanced; it was weighty. We see the weeping willow as not just curved but sad; a skyscraper isn’t just tall, it’s aggressively thrusting upward. Every shape or movement we apprehend has a distinctive flavor and feeling. Indeed, he writes, “expression can be described as the primary content of vision”!

We have been trained to think of perception as the recording of shapes, distances, hues, motions. The awareness of these measurable characteristics is really a fairly late accomplishment of the human mind. Even in the Western man of the twentieth century it presupposes special conditions. It is the attitude of the scientist and the engineer or of the salesman who estimates the size of a customer’s waist, the shade of a lipstick, the weight of a suitcase. But if I sit in front of a fireplace and watch the flames, I do not normally register certain shades of red, various degrees of brightness, geometrically defined shapes moving at such and such a speed. I see the graceful play of aggressive tongues, flexible striving, lively color. The face of a person is more readily perceived and remembered as being alert, tense, concentrated rather than being triangularly shaped, having slanted eyebrows, straight lips, and so on (Art and Visual Perception, first ed., 430).

Arnheim found feeling in his forms.

Moving pictures

Arnheim wrote about many artforms, including mass media in his 1936 monograph on radio. His book on cinema, Film als Kunst (1932), was quickly translated into English as Film (1933). Always in search of greater clarity and point, Arnheim rewrote it in 1957. Oddly, he didn’t update it: You’ll search in vain for examples from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s. The touchstones remain Chaplin, Keaton, von Sternberg, and the Soviets. Arnheim held that cinema was essentially a pictorial art (see my earlier blog on this question) and that synchronized sound added very little; in fact, it might even inhibit visual experimentation. It was so easy to convey a story point with dialogue that lazy filmmakers would simply create photographed stage plays.

As a result, Arnheim is usually taken to be the summation of a certain strain of 1920s film theory. Like many earlier thinkers, Arnheim emphasized how film technique reshapes what is filmed. Close-ups, shot design, camera angles, and cutting make cinema no simple medium of reproduction. Film form transforms the world that is photographed. This position, commonplace today, was a real advance in the silent era and gave cinema artistic respectability, a subject that Arnheim reflected on thoughtfully in the 1933 edition of Film.

Again, Arnheim did more than synthesize current ideas. Theorists’ hunches that film stylized reality could now be grounded in Gestalt ideas about medium and form. In effect, Arnheim rewrote Film in the light of Art and Visual Perception, and the result was Film as Art. Here is the most famous passage:

Not until film began to become an art was the interest moved from mere subject matter to aspects of form. What had hitherto been merely the urge to record certain actual events, now became the aim to represent objects by special means exclusive to film. These means obtrude themselves, show themselves able to do more than simple reproduce the required object; they sharpen it, impose a style upon it, point out special features, make it vivid and decorative. Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object (Film as Art, 57).

This, you might say, is Arnheim’s reply to Walter Benjamin’s theory of cinema as mechanical reproduction: no less than other artists, filmmakers use their medium, a photographic one, to create perceptually vivid effects akin to those in other arts.

Still, Arnheim held that film, like photography, has more limits than other arts. Tied to recording, film and photography can never achieve the range of expressive form we find in painting. I don’t believe this for a moment, but Arnheim clung to this opinion, I suspect, because of his deep love for creative freedom he found in other visual arts. And I sometimes think that for him, a painting harbored enough pushes, pulls, twists and torques. Movies just made explicit what was tactfully implied in still images.

Envoi

Kristin and I first saw Arnheim when we were graduate students at the University of Iowa, March 1972. He gave a lecture that stuck to his principles of 1933:

*Every art medium has a ceiling, beyond which it cannot effectively pass. The ceiling is somewhat low for the reproductive arts. Photography is more limited in what it can do than painting, and so is film.

*Films should be in black and white, the better to stylize reality. Are there no worthwhile color films? Pause. Red Desert, perhaps.

*Do you see many contemporary films? No.

Around 1980, I lined him up for a visiting lecture at UW. But he had to cancel; he had slipped on ice and broken his hip. He was then about seventy-five.

Later in the 1980s I visited Ann Arbor and had lunch with him. It was wonderful. By then I had read enough to ask him about Gombrich–an old friend and courtly opponent of his. (Read one of his reviews of Gombrich’s books to see what genuinely respectful disagreement looks like.) He saw pretty quickly that I was a Gombrichian and he gave a shrewd analysis of the dividing line: Gestalt psychology vs. ‘New Look’ cognitivism, illusions vs. expressive percepts, brain fields vs. schemas. He asked me to send me copies of my publications, which I did on and off during the decade. I never heard what he thought about my favorite fancy-pants sentence in Narration in the Fiction Film, when I contrasted J. J. Gibson’s theory of optical realism with Arnheim’s idea of expressiveness: “Gibson likes likeness, Arnheim loves liveliness.”

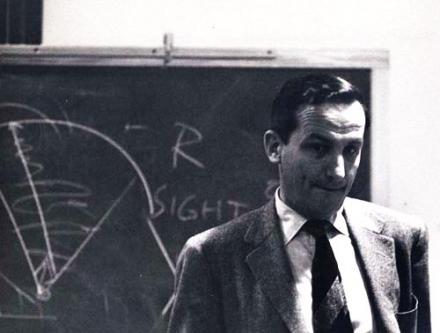

I thought of him often as I read more perceptual psychology. Gestalt work had once seemed to me a dead-end, but with David Marr’s theory of visual perception, a prototype of computational perceptual psychology, Gestaltism came roaring back. The “3D model representation” that Marr claimed operated in early vision uncannily echoes Arnheim’s discussion of our perception’s reliance on “characteristic aspects.” (Arnheim illustrates the idea with the various views of the chair, above. Which one is instantly recognizable as a chair?) And with contemporary interest in the relation between emotion and cognition, Arnheim’s theory of the expressive side of perception is creeping back too. Nothing worthwhile is forgotten, nothing goes away.

When we ran a book series at the University of Wisconsin Press, we were eager to publish an anthology of Arnheim’s film criticism, a collection originally published in German in 1977. Brenda Benthien, a close friend of Arnheim and his wife Mary, executed a lively translation and Arnheim supplied a touching introduction. A refugee of the Hitler years, an émigré across Europe and America, Arnheim summoned up the failure of the Weimar republic:

Even now I keep as a sort of talisman a bullet which in the days of the 1918 revolution, when I was fourteen, flew over the neighboring houses, bored a little hole through the windowpane, and fell inert on the carpet before my bed. Thus it began (Film Essays and Criticism, 3).

In the same introduction, Arnheim deplores the current state of cinema (“my basic objection to the talking film as a mongrel seems to me just as valid today as then”) and he warns against the cheapening of our vision:

Without the flourishing of visual expression no culture can function productively (5).

Aspiring film critics, and especially bloggers, should go back and read Arnheim on Keaton, Eisenstein, Gance, Pudovkin, Chaplin, von Sternberg, and other greats, as well as the essays “Style and monotony in film,” “Epic and dramatic film,” and especially “The Film Critic of Tomorrow.”

Scarcely a month goes by when I don’t have some idea that can be traced, however circuitously, to my reading of Arnheim. For instance, my blog on funny framings, posted a couple months ago, starts with his discussion of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. Arnheim’s theory of expression goes a long way toward explaining how composition can trigger laughter. I doubt that I’d be so alert to the possibilities of two-dimensional design in film shots if I hadn’t been tutored by Film as Art, Art and Visual Perception, The Power of the Center (1982, rev. 1988), his 1962 monograph on Picasso’s creative process in painting Guernica, and the essays in Toward a Psychology of Art (1966)–one of which is a skeptical review of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion. In preparing this entry, I found that my pleas that we probe the norms that guide filmmakers’ craft practices is just a clumsier restatement of this, which I discovered marked in Art and Visual Perception, the New Version:

Good art theory must smell of the studio, although its language should differ from the household talk of painters and sculptors (4).

Three years ago, after the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image convention in Grand Rapids, several of us from Madison–Ben Singer, Jen Chung, and Jonathan Frome–detoured back by way of Ann Arbor in order to call on Arnheim. He had just turned 100. He resided in an assisted-living facility, and his room was bright and clean, packed with books, remarkable drawings and paintings (Feininger, Köllwitz), a microfilm reader, and a worktable with a gigantic magnifying lens on an articulated arm. Conversation was difficult for him, but he seemed to understand everything we were saying. His smile was quick and his eyes were bright. When I showed him the first German edition of Film als Kunst I’d brought along, he turned it over in his hands as if he hadn’t seen one in years. He signed it, then shook his head apologetically at the shaky writing.

Now that Benjamin and Kracauer have become the prototypical Weimar intellectuals, it’s a pity that so many media students and professors are unaware of the importance of Arnheim’s work. His Leonardo-like interest in merging art and science is discouraged in a climate that posits the cultural construction of everything. He also writes with a grace and clarity that’s all too rare. In an unfashionable way, he exemplifies the passion, rigor, and dignity that interwar German intellectuals brought to the study of the arts. A lot of what he believed remains–what’s the word I want? Oh, yes–true.

Rudolf Arnheim, with Jonathan Frome, July 2004.

Line illustrations come from Art and Visual Perception.

Movies on the radio

DB here:

There’s no shortage of podcast film reviews, but I confess that I’ve listened to only a few. I’m just not that interested in following a movie review at the pace of a speaking voice; I prefer skimming print to pluck out the good parts. And I’m on the lookout for ideas and information, not only opinions. I want to learn new stuff. So my iPod favors shows that center on interviews with directors, writers, and moguls. The two programs that I like best are produced by the extraordinary KCRW in Santa Monica and are also available from iTunes.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

One is The Business, hosted by Claude Brodesser-Akner (above top). Armed with solid research and snappy patter, he comes across as sharp and a little insolent, a quality always welcome in an interviewer. After a disrespectful roundup called The Hollywood News Caravan, Brodesser-Akner devotes most of the rest of a show to a major topic. You can survey several programs here.

A recent installment focused on the latest cycle of teenage horror, with input from Eli Roth, director of the Hostel films, and Oren Koules, producer of the Saw series. They talk about marketing directly to the fan sites and avoiding the expensive TV ads that studios bombard the public with. Putting banners and flashing ads on the horror sites, Roth says, attracts the same eyeballs as an ad on Lost, but for a fraction of the price. Koules:

Playing [an ad] on a Friends rerun doesn’t help anyone.

Likewise for budgets overall. Roth:

The scare is the star. . . .Nobody wants to see a $50 million version of Saw II. . . . People aren’t paying for big special effects. They’re paying to be scared.

In one of the most interesting stretches of the interview, Roth and Koules explain how they negotiate with the MPAA ratings board. According to the filmmakers, the board completely understands what they want to give the audience and the board is willing to cooperate. Koules:

We’re very respectful of the process. . . . And they know that we kind of know the market.

The fact that the films are designed for an R rating makes the task easier, of course, but sexual violence remains the most sensitive area. Roth:

They’re reflecting what the parents of America are going to say. . . . Just look at the culture. We have violence on television, people watch it—no problem. The stuff that I did in Hostel 1 is now on 24. [But] Janet Jackson shows her nipple and Congress is in session meeting about it and there’re all sorts of fines. So [the raters] really are just reflecting the temperature of the culture.

More proof that the MPAA and the ratings board find it easier to accept the excesses of genre filmmaking than to support the naughty indie material Kirby Dick surveys in This Film Is Not Yet Rated. Why should bathing in blood rate an R while boinking, boffing, and the Wild Mambo get threatened with an NC-17?

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

I’ve been following The Business for a year or so, but in May while traveling in New Zealand I started listening to The Treatment, hosted by Elvis Mitchell (above, bottom). For all the superstar press he gets, he comes across as soft-spoken, thoughtful, and probing. It’s very unusual for a journalist-critic to pose questions about film craft and aesthetics, but Mitchell wades right in.

He asks Robert Rodriguez, for instance, how music shapes a film’s editing rhythms. After acknowledging that he plays music for actors on the set (as Wong Kar-wai does), Rodriguez adds:

I’ll be doing music all the way through the process of making a movie. And then I’ll usually just start editing first. Then I’ll put the edit into my music system, write the music for it, and if I like how the music is driving the scene and if the edits don’t match, I’ll go and adjust the edits. So I tell other composers—they’re probably very jealous—that I’m the composer who can tell the editor to go back and make the picture fit the music.

Another example: A while back, I posted a blog entry on how framing and the choice of lenses can create comic effects. I illustrated with an instance from Shaun of the Dead. Serendipitously, last week I discovered Mitchell’s recent interview with Shaun‘s director Edgar Wright, who acknowledged that the idea was central to his filmmaking.

The thing I’ve been trying to do in Spaced and Shaun and Hot Fuzz is the camera almost becomes a personality. Not only is the script funny and the performances are funny, but the compositions are funny—the framing of the shots is funny. . . . I remember seeing Raising Arizona and thinking, “Oh, why isn’t all comedy shot like this? It’s amazing.” . . . You get the actors to think of the camera as another performer that they’re blocking with.

The entire conversation seems to me mandatory for students of film. Coaxed by Mitchell, Wright supplies specifics about planning a shoot, varying camera setups, and the “epileptic” style of the contemporary action films that Hot Fuzz is satirizing. Wright even seems to like Domino, which shows that he can see virtues in extravagance.

So I recommend both The Business and The Treatment to anyone who wants to get filmmakers’ thoughts about current trends in movie tradecraft.