Archive for the 'FILM ART (the book)' Category

Movies still matter

Kristin here—

I don’t know whether I should be grateful or not when I read the film trade journals or major newspapers and run across columns bemoaning the decline of the cinema. On the one hand, these give me plenty of fodder for blogging. On the other, they promote a false impression that the movie industry and the art form in general are in far worse shape than they really are.

One recent case in point is Neil Gabler’s “The movie magic is gone,” from February 25, where he says that movies have lost their previous importance in American society and are less and less relevant to our lives.

Gabler makes some sweeping claims. Movie attendance is down because movies have lost the importance they once had in our culture. Our obsession with stars and celebrities has replaced our interest in the movies that create them. Niche marketing has replaced the old “communal appeal” of movies. The internet intensifies that division of audiences into tiny groups and fosters a growing narcissism among consumers of popular culture. Audiences have become less passive, creating their own movies for outlets like YouTube. In videogames, people’s avatars make them stars in their own right, and the narratives of games replace those of movies.

Films will survive, Gabler concludes, but they face “a challenge to the basic psychological satisfactions that the movies have traditionally provided. Where the movies once supplied plots, there are alternative plots everywhere.” This epochal challenge, he says, “may be a matter of metaphysics.”

All this is news to me, and I think I have been paying fairly close attention to what has been going on in the moviemaking sphere over the past ten years—the period over which Gabler claims all this has been happening. Evidence suggests that all of his points are invalid.

1. Gabler states that “the American film industry has been in a slow downward spiral.” Based on figures from Exhibitors Relations, a box-office tracking firm, attendance at theaters fell from 2005 (a particularly down year) to 2006. A Zogby survey found that 45% of Americans had decreased their movie-going over the past five years, especially including the key 18-24-year-old audience. “Foreign receipts have been down, too, and even DVD sales are plateauing.” Such a broad decline “suggests that something has fundamentally changed in our relationship to the movies.”

Turning to a March 6 Variety article by Ian Mohr, “Box office, admissions rise in 2006,” we read a very different account of recent trends. According to the Motion Picture Association of America, admissions rose, “with 1.45 billion tickets sold in 2006—ending a three-year downward trend.” Foreign markets improved as well, “where international box office set a record of $16.33 billion as it jumped 14% from the 2005 total.” Within the U.S., grosses rose 5.5% over 2005.

We should keep in mind that part of the perception of a recent decline comes from the fact that 2002 was a huge year for box-office totals, mainly stemming from the coincidence of releases of entries in what were then the four biggest franchises going: Spider-man, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Star Wars. There was almost bound to be a decline after that. Such films make so much money that the fluctuations in annual box-office receipts in part reflect the number of mega-blockbusters that appear in a given year.

Looking at the longer terms, though, the biggest decline in U.S. movie-going was in the 1950s, as television and other competing leisure activities chipped away at audiences. Even so, the movies survived and from 1960 onward annual attendance hovered at just under a billion people. From 1992 on, a slow rise occurred, until by 1998 it reached roughly 1.5 billion and has hovered around that figure ever since, with a peak in 2002 at 1.63 billion. Variety’s figure of 1.45 billion for 2006 fits the pattern perfectly. In short, there has been no significant fall-off since the 1950s. (See the appendix in David’s The Way Hollywood Tells It for a year-by-year breakdown.) The article also states that industry observers expect 2007 to be especially high, given the Harry Potter, Spider-man, and Pirates of the Caribbean entries due out this year. About a year from now, expect pundits to be seeking reasons within the culture why movie-going is up. I suspect they will find that we are looking for escapism. Safe enough. When aren’t we?

Apart from theatrical attendance figures, let’s not forget that more people are watching the same movies on DVDs and on bootleg copies that don’t get into the official statistics.

2. Gabler claims that movies are no longer “the democratic art” that they were in the 20th Century. During that century, even faced with the introduction of TV, “the movies still managed to occupy the center of American life….A Pauline Kael review in the New Yorker could once ignite an intellectual firestorm … People don’t talk about movies the way they once did.”

Maybe the occasional Kael review created debate, as when she claimed that Last Tango in Paris was the “Rite of Spring” of the cinema. I think we all know by now that she was wrong. A lot of us even knew it at the time, and it’s no wonder that people argued with her. I doubt that attempts to refute her claims there or in other reviews reflected much about the health of the general population’s enthusiasm for movies.

More crucially, however, people do still talk about the movies, and lively debates go on. It’s just that now much of the discussion happens on the internet, on blogs and specialized movie sites, and in Yahoo! groups. (Who would have thought that David’s entry on Sátántango would be popular, and yet there turn out to be quite a few people out there passionately interested in Tarr’s film.)

Some would see the health of movie fandom on the internet as a sign that the cinema has become more democratic than ever. Now it’s not just casual water-cooler talk or a group of critics arguing among themselves. Anyone can get involved. The results range from vapid to insightful, but there’s an immense amount of discussion going on.

3. Interest in movies has eroded in part due to what Gabler has termed “knowingness.” By this he means the delight people take in knowing the latest gossip about celebrities. Movies have declined in importance because they exist now in part to feed tabloids and entertainment magazines.

“Knowingness” is basically a taste for infotainment. Infotainment had been around in a small way since before World War I in the form of fan magazines and gossip columns. It really took off beginning in the 1970s, with the rise of cable and the growth of big media companies that could promote their products—like movies—across multiple platforms. (I trace the rise of infotainment in Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise.) It’s not clear why one should assume that a greater consumption of infotainment leads to less interest in going to movies.

People in the film industry seem to assume the opposite. Studio publicity departments and stars’ personal publicity managers feed the gossip outlets, in part to control what sorts of information get out but mainly because those outlets provide great swathes of free publicity. With the rise of new media, there are more infotainment outlets appearing all the time. Naturally this trend is obvious even to those of us who don’t care about Britney’s latest escapade. But I doubt that watching Britney coverage actually makes people less inclined to go to, say, The Devil Wears Prada, one of the mid-range surprise successes that helped boost 2006’s box-office figures.

4. Movies have lost their “communal appeal” in part because the public has splintered into smaller groups, and the industry targets more specialized niche markets. According to Gabler, “the conservative impulse of our politics that has promoted the individual rather than the community has helped undermine movies’ communitarian appeal.”

Let’s put aside the idea that conservative politics erode the desire for community. The extreme right wing has certainly put enough stress on community and has banded together all too effectively to promote their own mutual interests lately. But is the industry truly marketing primarily to niche audiences?

Of course there are genre films. There always have been. Some appeal to limited audiences, as with the teen-oriented slasher movie. Yet despite the continued production of low-budget horror films, comedies, romances, and so on, Hollywood makes movies aimed at the “family” market because so many moviegoers fit into that category. Most of the successful blockbusters of recent years have consistently been rated PG or PG-13. According to Variety, 85% of the top 20 films of 2006 carried these ratings. Pirates of the Caribbean, Spider-man, Harry Potter—these are not niche pictures, though distributors typically devise a series of marketing strategies for each film, with some appealing to teen-age girls, others to older couples, and so on.

(An important essay by Peter Krämer discusses blockbusters with broad appeal: “Would you take your child to see this film? The cultural and social work of the family-adventure movie,” in Steve Neale and Murray Smith’s anthology, Contemporary Hollywood Cinema, published by Routledge in 1998.)

The result is that, despite the fact that niche-oriented films appear and draw in a limited demographic, there are certain “event” pictures every year that nearly everyone who goes to movies at all will see—more so than was probably the case in the classic studio era. Those films saturate our culture, however briefly, and surely they “enter the nation’s conversation,” as Gabler claims “older” films like The Godfather, Titanic, and The Lord of the Rings did. By the way, the last installment of The Lord of the Rings came out only a little over three years ago. Surely the vast cultural upheaval that the author posits can’t have happened that quickly.

5. The internet exacerbates this niche effect by dividing users into tiny groups and creates a “narcissism” that “undermines the movies.”

See number 2 above. I don’t know why participating in small group discussions on the internet should breed narcissism any more than would a bunch of people standing around an office talking about the same thing. In fact, there are thousands of people on the internet spending a lot of their own time and effort, many of them not getting paid for it, providing information and striving to interest others in the movies they admire.

The internet allows likeminded people to find each other with blinding speed. Often fans will stress the fact that what they form are communities. They delight in knowing that many share their taste and want to interact with them. Some of these people no doubt have big egos and are showing off to whomever will pay attention. Narcissism, however, implies a solitary self-absorption that seems rare in online communities.

A great many of these communities form around interest in movies. In this way, the internet has made movies more important in these people’s lives, not less.

6. Audiences have become active, creating their own entertainment for outlets like YouTube, and are hence less interested in passive movie viewing. These are situations “in which the user is effectively made into a star and in which content is democratized.”

No doubt more people are writing, composing, filming, and otherwise being creative because of the internet. Some of this creativity and the consumption of it by internet users takes up time they could be using watching movies.

Yet anyone who visits YouTube knows that a huge number of the clips and shorts posted there are movie scenes, trailers, music videos based on movie scenes, little films re-edited out of shots taken from existing movies, and so on. In some cases the makers of these films have pored over the original and lovingly re-crafted it in very clever ways. A lot of the creativity Gabler notes actually is inspired by movies. Some people post their films on YouTube because they are aspiring movie-makers hoping to get noticed. The movie industry as a whole is not at odds with YouTube and other sites of fan activity, despite the occasional removal of items deemed to constitute piracy.

7. New media allow these active, narcissistic spectators to star in their own “alternative lives.” “Who needs Brad Pitt if you can be your own hero on a video game, make your own video on YouTube or feature yourself on Facebook?”

In discussing videogames, Gabler perpetuates the myth that “video games generate more income than movies.” This is far from being true, and hence his claim that videogames are superseding movies is shaky. (I debunk this myth in Chapter 8 of The Frodo Franchise.)

Even the spread of videogames does not necessarily mean that fans are deserting movies. On the contrary, there is evidence that people who consume new media also consume the old medium of cinema. Mohr’s Variety article reports on a recent study by Nielsen Entertainment/NRG: “Somewhat surprisingly, the same study revealed that the more home entertainment technology an American owns, the higher his rate of theater attendance outside the home. People with households containing four or more high-tech components or entertainment delivery systems—from DVD players to Netflix subscriptions, digital cable, videogame systems or high-def TV—see an average of three more films per year in theaters than people with less technology available in their homes.”

Apart from the shaky factual basis of the column, what does the end-of-cinema genre tell us about how trends get interpreted by commentators?

As I pointed out in my March 9 entry, some commentators explain perceived trends in film by generalizing about the content of the movies themselves. “As soon as some trend or apparent trend is spotted, the commentator turns to the content of the films to explain the change. If foreign or indie films dominate the awards season, it must be because blockbusters have finally outworn their welcome. If foreign or indie films decline, it must be because audiences want to retreat from reality into fantasy. It’s an easy way to generate copy that sounds like it’s saying something and will be easily comprehensible to the general reader.”

Gabler is arguing for something different—something that, if it were true would be more depressing for those who love movies. He’s not positing that movies have failed to cater to the national psyche. He’s claiming that other forces, largely involving new media, have changed that national psyche in a way which moviemakers could never really cope with. Cinema as an art form cannot provide what these other media can, and spectators caught up in the options those media offer will never go back to loving movies, no matter what stories or stars Hollywood comes up with. By his lights, the movies are apparently doomed to a long, irreversible decline.

Hollywood has what I think is a more sensible view of new media. Games, cell phones, websites, and all the platforms to come are ways of selling variants of the same material. Film plots are valuable not just as the basis for movies but because they are intellectual property that can be sold on DVD, pay-per-view, and soon, over the internet. They can be adapted into video games, music videos, and even old media products like graphic novels and board games.

Not only Hollywood but the new media industries have already analyzed the changing situation and come up with new approaches to dealing it. Check out IBM’s new Navigating the media divide: Innovating and enabling new business models. Those models include “Walled communities,” “Traditional media,” “New platform aggregation,” and “Content hyper-syndication,” which, the authors predict, “will likely coexist for the mid term.”

In other words, traditional media like the cinema aren’t dying out. No art form that has been devised across the history of humanity has disappeared. Movies didn’t kill theater, and TV didn’t kill movies. It’s highly significant that the main components of new media—computers, gaming consoles, and the internet—have all added features that allow us to watch movies on them.

The big movies still get more press coverage than the big videogames partly because they usually are the source of the whole string of products. If a movie doesn’t sell well, it’s likely that its videogame and its DVD and all its other ancillaries won’t either. That is a key word, for many of the new media that Gabler mentions produce the ancillaries revolving around a movie. So far, very few movies are themselves ancillary to anything generated with new media. If you doubt that, check out Box Office Mojo’s chart of films based on videogames, which contains all of 22 entries made since 1989.

One final point. Film festivals are springing up like weeds around the world. Enthusiasts travel long distances to attend them. That’s devotion to movies. From last year’s Wisconsin Film Festival, add 26,000 tickets sold to that 1.5 billion attendance figure.

Movies still matter enormously to many people. New media have given them new ways to reach us, and us new ways to explore why they matter.

This is your brain on movies, maybe

United 93.

From DB:

Normally we say that suspense demands an uncertainty about how things will turn out. Watching Hitchcock’s Notorious for the first time, you feel suspense at certain points–when the champagne is running out during the cocktail party, or when Devlin escorts the drugged Alicia out of Sebastian’s house. That’s because, we usually say, you don’t know if the spying couple will succeed in their mission.

But later you watch Notorious a second time. Strangely, you feel suspense, moment by moment, all over again. You know perfectly well how things will turn out, so how can there be uncertainty? How can you feel suspense on the second, or twenty-second viewing?

I was reminded of this problem watching United 93, which presents a slightly different case of the same phenomenon. Although I was watching it for the first time, I knew the outcomes of the 9/11 events it portrays. I knew in advance that the passengers were going to struggle with the hijackers and deflect the plane from its target, at the cost of all their lives. Yet I felt what seemed to me to be authentic suspense at key moments. It was as if some part of me were hoping against hope, as the saying goes, that disaster might be avoided. And perhaps the film’s many admirers will feel something like that suspense on repeated viewings as well.

Psychologist Richard Gerrig in his book Experiencing Narrative Worlds calls this anomalous suspense: feeling suspense when reading or viewing, although you know the outcome.

Anomalous suspense: Some theories

Anomalous suspense has been fairly important in the history of film. One of the most famous instances in the early years of feature film is the assassination of President Lincoln in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith prolongs the event with crosscutting and detail shots in a way that promotes suspense, even though we know that Booth will murder Lincoln. Anomalous suspense, of course, isn’t specific to movies; we can feel this way reading a familiar book or watching a TV docudrama about historical events. Young children listening to the story of Little Red Riding Hood seem to be no less wrought up on the umpteenth version than on the first.

This is very odd. How can it happen?

One answer is simple: What you’re feeling in a repeat viewing, or a viewing of dramatized historical events, isn’t suspense at all. Robert Yanal has explained this position here. He suggests that you’re responding to other aspects of the story. Maybe in rewatching Notorious you’re enjoying the unfolding romance, and you attribute your interest to suspense. And there are feelings akin to suspense that don’t rely on uncertainty–dread, for instance, in facing likely doom. (This is my example, not Yanal’s, but I think it’s plausible.) Another possibility Yanal floats is that on repeat viewings, you have actually forgotten what happens next, or how the story ends.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Richard Gerrig, the psychologist who gave anomalous suspense its name, offers a different solution. He posits that in general, when we reread a novel or rewatch a film, our cognitive system doesn’t apply its prior knowledge of what will happen. Why? Because our minds evolved to deal with the real world, and there you never know exactly what will happen next. Every situation is unique, and no course of events is literally identical to an earlier one. “Our moment-by-moment processes evolved in response to the brute fact of nonrepetition” (Experiencing Narrative Worlds, 171). Somehow, this assumption that every act is unique became our default for understanding events, even fictional ones we’ve encountered before.

I think that Gerrig leaves this account somewhat vague, and its conception of a “unique” event has been criticized by Yanal, in the article above. But I think that Gerrig’s invocation of our evolutionary history is relevant, for reasons I’ll mention shortly.

Suspense as morality, probability, and imagination

The most influential current theory of suspense in narrative is put forth by Noël Carroll. The original statement of it can be found in “Toward a Theory of Film Suspense” in his book Theorizing the Moving Image. Carroll proposes that suspense depends on our forming tacit questions about the story as it unfolds. Among other things, we ask how plausible certain outcomes are and how morally worthy they are. For Carroll, the reader or viewer feels suspense as a result of estimating, more or less intuitively, that the situation presents a morally undesirable outcome that is strongly probable.

When the plot indicates that an evil character will probably fail to achieve his or her end, there isn’t much suspense. Likewise, when a good character is likely to succeed, there isn’t much suspense. But we do feel suspense when it seems that an evil character is likely to succeed, or that a good character is likely to fail. Given the premises of the situation, the likelihood is very great that Alicia and Devlin will be caught by Sebastian and the Nazis, so we feel suspense.

What of anomalous suspense? Carroll would seem to have a problem here. If we know the outcome of a situation because we’ve seen the movie before, wouldn’t our assessments of probability shift? On the second viewing of Notorious, we can confidently say that Alicia and Devlin’s stratagems have a 100% chance of success. So then we ought not to feel any suspense.

Carroll’s answer is that we can feel emotions in response to thoughts as well as beliefs. Standing at a viewing station on a mountaintop, safe behind the railing, I can look down and feel fear. I don’t really believe I’ll fall. If I did, I would back away fast. I imagine I’m going to fall; perhaps I even picture myself plunging into the void and, a la Björk, slamming against the rocks at the bottom. Just the thought of it makes my palms clammy on the rail.

Carroll points out that imagining things can arouse intense emotions, and his book The Philosophy of Horror uses this point to explain the appeal of horrific fictions. The same thing goes, more or less, for suspense. If the uncertainty at the root of suspense involves beliefs, then there ought to be a problem with repeat viewings. But if you merely entertain the thought that the story situation is uncertain, then you can feel suspense just as easily as if you entertained the thought that you were falling off the mountain top.

In other words, the relation between morality and probability in a suspenseful situation is offered not to your beliefs but to your imagination. When you judge that in this story the good is unlikely to be rewarded, you react appropriately–regardless of what you know or believe about what happens next. Carroll outlines this view in his book Beyond Aesthetics.

How are we encouraged to entertain such thoughts in our imagination? Carroll indicates that the film or piece of literature needs to focus our attention on the suspenseful factors at work, thus guiding us to the appropriate thoughts about the situation. There might, though, be more than attention at work here.

The firewall

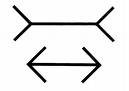

In Consciousness and the Computational Mind (1987), psychologist Ray Jackendoff asked why music doesn’t wear out. When composers write tricky chord progressions or players execute startling rhythmic changes, why do those surprise or thrill us on rehearing? Similarly, you’ve seen the Müller-Lyer optical illusion many times, and you know that the two horizontal lines are of equal length. You can measure them.

Yet your eyes tell you that the lines are of different lengths and no knowledge can make you see them any other way. This illusion, in Jerry Fodor‘s phrase, is cognitively impenetrable.

We can reexperience familiar music or fall prey to optical illusions because, in essence, our lower-level perceptual activities are modular. They are fast and split up into many parallel processes working at once. They’re also fairly dumb, quite impervious to knowledge. Jackendoff suggests that our musical perception, like our faculties for language and vision, relies on

a number of autonomous units, each working in its own limited domain, with limited access to memory. For under this conception, expectation, suspense, satisfaction, and surprise can occur within the processor: in effect, the processor is always hearing the piece for the first time (245).

The modularity of “early vision”–the earliest stages of visual processing–is exhaustively discussed by Zenon W. Pylyshyn in Seeing and Visualizing: It’s Not What You Think (2006).

As students of cinema, we’re familiar with the fact that vision can be cognitively impenetrable. We know that movies consist of single frames, but we can’t see them in projection; we see a moving image.

Early vision works fast and under very basic, hard-wired assumptions about how the world is. That’s because our visual system evolved to detect regularities in a certain kind of environment. That environment didn’t include movies or cunningly designed optical illusions. So there might be a kind of firewall between parts of our perception and our knowledge or memory about the real world.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

So here’s my hunch: A great deal of what contributes to suspense in films derives from low-level, modular processes. They are cognitively impenetrable, and that creates a firewall between them and what we remember from previous viewings.

A suspense film often contains several very gross cues to our perceptual uptake. We get tension-filled music and ominous sound effects, such as low-bass throbbing. We get rapid cutting and swift camera movements. Often the shots are close-ups, as in Notorious‘s wine-cellar scene and during the characters’ final descent of the staircase. Close-ups concentrate our vision on one salient item, creating the attentional focus Carroll emphasizes. The shots are often cut together so fast that we barely have time to register the information in each one.

This isn’t to say that the action itself has to be fast. The action in the Hitchcock scenes isn’t rapid, but its stylistic treatment is. In typical suspense scenes, our “early vision” and “early audition,” biased toward quick pickup, are given rapid-fire bursts of information while our slower, deliberative processes are put on hold. This is happening in the Birth of a Nation assassination scene, as well as in the frantic second half of United 93.

Further, what is shown can push our processing as well. Seeing people’s facial expressions touches off empathy and emotional contagion, perhaps through mirror neurons.

This tendency may explain why we can, momentarily, feel a wisp of empathy for unsympathetic characters. When their expressions show fear, we detect and resonate to that even if we aren’t rooting for them to succeed.

We may also be responding to some very basic scenarios for suspenseful action. Imagine dangling at a great height; “hanging” is the root of the word suspense. Or imagine hurtling toward an obstruction, or being stalked by an animal, or being advanced upon by a looming figure. As prototypes of impending danger, these events may in themselves trigger a minimal feeling of suspense. And such situations are part of filmic storytelling from its earliest years.

Maybe we’re predisposed to find facial expressions and dangerous situations salient because of our evolutionary history, or maybe they’re learned from a very young age. Either way, such responses don’t require much deliberate thinking. They just trigger rapid responses that we can reflect upon later.

Stylistic emphasis and prototype situations surely help the attention-focusing that Carroll discusses. But I’m suggesting something stronger: Many of these cues don’t merely guide our attention to the critical suspense-creating factors in the scene. These cues are arresting and arousing in themselves. They trigger responses that, in the right narrative situation, can generate suspense, regardless of whether we’ve seen the movie before.

Beyond these cues, of course we have to understand the story to some degree. Probably some of the aspects of storytelling that Carroll, Gerrig, and others (including me) have highlighted come into play. As Hitchcock famously pointed out, suspense sometimes depends on telling the viewer more than the character knows. We have to see the bomb under the table that the character doesn’t know about. Suspense is also conjured up by Carroll’s ratio of morality to probability, our real-world understanding of deadlines, and other higher-order aspects of comprehension. In addition, our knowledge of how stories are typically told probably shapes our uptake. We expect suspense to be a part of a film, and so we’re alert for cues that facilitate it.

Involuntary suspense

So I’m hypothesizing that part of the suspense we feel in rewatching a film depends on fast, mandatory, data-driven pickup. That activity responds to the salient information without regard to what we already know.

According to this argument, the sight of Eve Kendall dangling from Mount Rushmore will elicit some degree of suspense no matter how many times you’ve seen North by Northwest, and that feeling will be amplified by the cutting, the close-ups, the music, and so on. Your sensory system can’t help but respond, just as it can’t help seeing equal-length lines in the pictorial illusion. For some part of you, every viewing of a movie is the first viewing.

This tendency may hold good for other emotions than suspense. In the psychological jargon I adopted in Narration in the Fiction Film, experiencing a narrative is likely to be both a bottom-up process and a top-down process. Suspense and other emotional effects in film may depend not only on conceptual judgments about uncertainty, likelihood, and so on. They may also depend on quick and dirty processes of perception that don’t have much access to memory or deliberative thinking.

Film works on our embodied minds, and the “embodied” part includes a wondrous number of fast, involuntary brain activities. This process gives filmmakers enormous power, along with enormous responsibilities.

PS: 9 March. Jason Mittell writes a comment, based on his recent research on TV fans’ attitudes toward spoilers, at his site here. More later, I hope, when I have a chance to assimilate his argument.

Bs in their bonnets: A three-day conversation well worth the reading

From DB:

The Film faculty and graduate students at the University of Wisconsin—Madison are a close-knit bunch. Keeping in touch via email, we exchange ideas about teaching and research, as well as passing along gossip and peculiar things that appear on the Internets. Our community includes grad students and alumni from several generations. The youngest are taking courses now; the most senior were here in the early 1970s, and they still have all their marbles.

Over three days earlier this month, there was a lightning round of exchanges on B films. With the permission of the participants, I’m posting highlights of the correspondence here because it exemplifies one way in which the Web can advance film studies.

Most film writing on the web comments on current films or video releases. Nothing wrong with that. But if you’re a researcher into film, you also want to talk about history. It’s rare to find an online debate about historical evidence and alternative interpretations of that evidence.

So to scratch my academic itch, I give you mildly edited extracts from our UW cyber-dialogue. You’ll see some hard-working professors practicing imaginative pedagogy, and you’ll find ideas for research and teaching. You’ll also see, I hope, that film studies can make progress by asking precise questions and refining them through inquiry and critical discussion.

Note to film scholars: Blogs are seldom cited in academic writing, but if you intend to use this material in your own research, it would be courteous to mention these esteemed sources, as they mention others.

To be a B, or not to be a B

First, a little background. Today sometimes we call low-budget films or just poor quality movies “B movies.” But across the history of Hollywood the term had a more specific meaning. You can find a primer at GreenCine, but here’s a little more industrial context.

During the heyday of the studio system, most theatres ran double bills—two movies for a single ticket (along with trailers, news shorts, cartoons, and the like). Very often the main feature, or A picture, was a high-budget item with major stars from a significant studio. The B film was low-budget, ran to only 60-80 minutes, and showcased lesser-known players. A B tended to be distributed for a flat fee rather than a percentage of the box office.

(I’ve just distinguished Bs in terms of its level of production; as you’ll see from the dialogue, we can think of them in other ways too.)

MGM, Warner Bros., Twentieth Century-Fox, and other major companies made B pictures as well as As. Often the B film was part of a series. Fox had Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan, MGM had Andy Hardy and Dr. Kildare. Since the most powerful studios owned theatres as well, the B film filled out the double bill with company product. Moreover, the Bs allowed studios to make maximum use of the physical plant. Sets built for an A picture could be used for a B, and actors idling between big projects could take small parts in Bs. Bs could also serve as training ground for stars, crews, and directors who might move up.

Other companies concentrated wholly on making B pictures. The most famous of these so-called Poverty Row studios are Monogram, Republic, Mascot, and Producers Releasing Corp. Besides turning out stand-alone Bs, the Poverty Row studios specialized in serials, like Don Winslow of the Navy and Hurricane Express (1932, Mascot, with John Wayne, right).

Other companies concentrated wholly on making B pictures. The most famous of these so-called Poverty Row studios are Monogram, Republic, Mascot, and Producers Releasing Corp. Besides turning out stand-alone Bs, the Poverty Row studios specialized in serials, like Don Winslow of the Navy and Hurricane Express (1932, Mascot, with John Wayne, right).

Still other studios, the so-called Little Three, hovered between A and B status. Universal, Columbia, and RKO were smaller companies, and some of their A pictures might have been considered really B’s, in terms of budget and resources. This is one theme of the conversation that follows.

As the major studios cut back production after the war, many B pictures were made as independent productions. Double bills in the US persisted into the 1960s, and Roger Corman and other producers turned out B-films for drive-ins, declining picture palaces, and rural theatres. Still, the prime years of B films were the 1930s-early 1950s. They have always been an object of admiration for cultists; recall that Godard dedicated Breathless to Monogram. Important directors like Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher started in B production. Several Bs, notably noirs and horror films, are staples of cable and home video.

Want to know more? Here’s some essential reading: Tino Balio’s The American Film Industry, rev. ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985); Douglas Gomery, The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2005); Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, eds., Kings of the Bs: Working within the Hollywood System (New York: Dutton, 1975).

Now to the question of the day.

Day 1: What do I teach?

It all began on 6 February. (Cue harp music and dissolve here.) Paul Ramaeker of the University of Otago asked an innocent question….

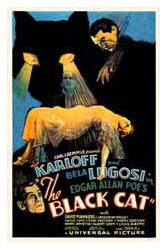

OK, so I am running a grad seminar (or, more precisely, our closest equivalent- a 4th year Honours course) on Classical Hollywood Cinema. I want to spend time on the industry, obviously, which raises questions about what to screen for those weeks. I thought an A pic and a B pic. For the A, I was thinking about Robin Hood. For the B, I’m not sure, but I had for other purposes been considering a double bill of The Black Cat and I Walked with a Zombie. Now, the latter, I know, is a B pic; but is The Black Cat a B? It’s about an hour, which suggests a B and it’s not got a lot of sets. But it’s got Lugosi and Karloff, who surely were two of Universal’s bigger stars at the time, right? So which is it?

Any other good B pic recommendations are welcome.

The replies came fast. First, from Jane Greene of Denison University:

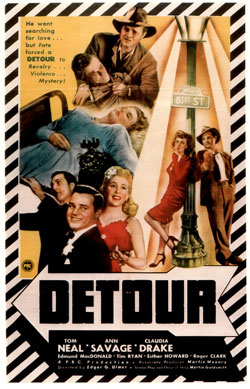

I do the same thing in my history class and I’ve found that Casablanca and Detour work well. It helps that most students have heard of Casablanca and a surprising number have seen it. You can point out how this “timeless classic” was very much a product of collaboration, how the star system, budget and schedule determined the look of many scenes, and it also allows you to discuss censorship… I mean self-regulation. (See Richard Maltby’s “Dick and Jane Go to 3.5 Seconds of the Classical Hollywood Cinema” in a little-known book called Post-Theory.)

Aljean Harmetz’s The Making of Casablanca is coffee-table-y, but she did consult tons of production and publicity material and there are reproductions of production documents (script pages, even a Daily Production Report!).

And, if yer willing to go Poverty Row for yer B Film, Detour just rocks. It’s so obviously re-using 2-3 sets and locations, has the foggiest scene ever shot, and long voiceovers that sound deep and poetic and take up half the film. The kids love it. And it could ease you gently into the waters of film noir, should you wish to go that way (and I bet you do).

And, if yer willing to go Poverty Row for yer B Film, Detour just rocks. It’s so obviously re-using 2-3 sets and locations, has the foggiest scene ever shot, and long voiceovers that sound deep and poetic and take up half the film. The kids love it. And it could ease you gently into the waters of film noir, should you wish to go that way (and I bet you do).

Leslie Midkiff DeBauche of UW—Stevens Point also shared a teaching technique.

I teach the 1930s with a colleague in the History Department and we like to create a whole program: News Parade of 1934 from Hearst Metronome News; Three Little Pigs (1933), followed by the first half of a documentary called “Encore on Woodward” about the Fox Theater opening in Detroit. It opens in 1929 and is wonderful–it has clips of late silents like Seventh Heaven, sound comes, and we end it after a woman remembers how her boyfriend proposed to her, in the balcony, during Robin Hood. We usually show the 1936 (I think, it could be 1934) year-in-review newsreel that is on the Treasures of the Archive

I set of DVDs and the feature we use is It Happened One Night. What the students like best though is the popcorn and the give-a-ways between the parts of the program: Nancy Drew and Superman, a bag of groceries with food items from 1930s–turns out to be current student food–Bisquick, Snickers, Jiffy peanut butter,Ritz crackers. The grand prize bank night equivalent is an A on the final exam. They freak! It is like they won big money.

From Notre Dame comes Chris Sieving on RKO:

In researching Lewton last year I found a few sources that argue vehemently that the Lewton-Tourneur-Wise-Robson horror films were not B films, but more like nervous As: budgets were decent, prestige factor was high, occasional name stars (like Karloff).

Another veddy interesting and perhaps more “authentic” B film, besides Detour, is Stranger on the Third Floor (1940). It contains some very bizarre and magical Peter Lorre acting, plus some people call it the “first” film noir. (Speaking of film history myths that need debunking…)

Lea Jacobs, doyenne of Film Studies here in Madison interjects:

I would think The Black Cat is a B, not only because of running time but because of genre. When I was researching the distribution of B’s at RKO I was surprised by the way the horror films made by Val Lewton’s unit at RKO (many justly celebrated today) were treated as the lowest of the low–opening alongside films with titles like Boy Slaves at the small Rivoli or Rialto theaters in New York for very short runs, and later booked in and out of theaters nationally on an ad hoc basis. See my article, “The B Film and the Problem of Cultural Distinction,” Screen 33, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 1-13. I also think that Universal simply wasn’t making many A films in 1934, even with their recognizable stars.

I would think The Black Cat is a B, not only because of running time but because of genre. When I was researching the distribution of B’s at RKO I was surprised by the way the horror films made by Val Lewton’s unit at RKO (many justly celebrated today) were treated as the lowest of the low–opening alongside films with titles like Boy Slaves at the small Rivoli or Rialto theaters in New York for very short runs, and later booked in and out of theaters nationally on an ad hoc basis. See my article, “The B Film and the Problem of Cultural Distinction,” Screen 33, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 1-13. I also think that Universal simply wasn’t making many A films in 1934, even with their recognizable stars.

When I teach the B film I like to show Detour and Moon Over Harlem (now out on DVD). The latter has two really amazing scenes in a movie made for less than $10,000. But maybe that is too Ulmer heavy. Anyway you can’t go wrong with I Walked with a Zombie.

Kevin Heffernan of Southern Methodist University weighs in.

Great movies, Paul! “Cries of pleasure will be torn from” your students (as they were from our hero in S/Z).

Great movies, Paul! “Cries of pleasure will be torn from” your students (as they were from our hero in S/Z).

The Black Cat is an A picture, I think. All of the Universal horror movies ran between 65-71 mins, so this is just under their average. Also, names above the title usually point to an A, and I’m virtually certain the movie would have played a percentage (rather than a flat fee) in its initial engagement. I would imagine that a Universal horror picture sold well in subsequent run as a component in double bills, so they would be sort of de facto B pics in some situations.

And it is worth mentioning to your students, as Elder Goodman [Douglas] Gomery pointed out years ago, that the Deanna Durbin musicals were much more financially successful for Laemmle et cie than the horror movies. They’re all out on video now. Ghastly, unwatchable, wretched.

Lea Jacobs replies:

Universal is one of the little three in 1934, and, unlike today, when horror films command high budgets and garner big returns, in the 1930s horror films and sci fi were the stuff of serials and the bottom half of the double bill. I would have to see a contract before I believe it played for a percentage. One way, apart from that, to decide, is to look at where it opened in New York, how long it played and where it played subsequently in the key cities.

Doug Gomery, Resident Scholar at the University of Maryland, is succinct on I Walked with a Zombie:

RKO in the 1940s was a low budget studio and Floyd Odlum owned it. Odlum went cheap after his experiment with the likes of Citizen Kane. So it was B pure and simple.

Then Hughes bought it after the war and dabbled with his strange way of doing things.

It’s now 5:30 on the same day, but are our eager scholars tired? You have to ask?

Lea Jacobs follows up:

It is pretty safe to assume that most Universals in the 1930s were in the B range–their films were shown on the bottom of the double bills in theaters owned by the Majors. Even in the 1920s one reads Variety complaining about the cheapness of Universal’s product. A far cry from when it was taken over by Doug’s favorite Lew Wasserman.

Jim Udden of Gettysburg College jumps in, invoking the founder of film-industry studies at UW, Tino Balio:

Tino does discuss this issue in Grand Design. According to him, Frankenstein and Dracula are clearly A pics, part of Universal’s strategy to break into the first-run market, since, as we all know, they had very few theaters of their own. But Black Cat is only one third the budget of Frankenstein, according to the figures in IMDB.com. Does that make it a B pic? Perhaps. Yet it seems to me that this film could still have been marketed and released like the initial Universal Horror films, riding on their coat tails, so to speak, but with less actual money invested in the production.

Tino does discuss this issue in Grand Design. According to him, Frankenstein and Dracula are clearly A pics, part of Universal’s strategy to break into the first-run market, since, as we all know, they had very few theaters of their own. But Black Cat is only one third the budget of Frankenstein, according to the figures in IMDB.com. Does that make it a B pic? Perhaps. Yet it seems to me that this film could still have been marketed and released like the initial Universal Horror films, riding on their coat tails, so to speak, but with less actual money invested in the production.

So was Black Cat more often one of these “featured” features, or was it usually the bottom half of the double bill, as Lea says? Maybe this is an AB pic?

This to me, sound like a researchable topic! (I myself have not time for this, unfortunately…)

Lea Jacobs replies:

Yes, Jim, I agree, a researchable question that I don’t have time for either. But a distinction that can be made, without research (or prior to it) is one between A/B at the level of production planning and budget and A/B at the level of distribution. Sometimes relatively “cheap” films were marketed as As (Variety usually complains about this its reviews!). Thus, to be really certain of how a film lines up, you have to look at both the budget ranges at the studio at the time of the films’ production, and the distribution pattern, including, of course, whether it was distributed for a percentage or flat fee.

Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University, comes rolling in at 10:30 pm.

* The trouble with some of the great B’s, like The Black Cat, Detour, and I Walked with a Zombie is that they’re so good that they don’t give a sense of the real purpose of the “B,” which was to hold down half of a double bill, and amortize overhead at the studios over a larger number of opportunities for revenue – that is, individual films. A comparison of scenes from an A film and a B film using the same standing sets does this nicely; I use the RKO New York street set, visible in Citizen Kane and Stranger on the Third Floor, as an example. (A great visual example I’d like to make would be Lewton’s Ghost Ship, which is said to be a script written for an existing ocean liner set, but I haven’t seen that set in another RKO film as yet.)

*I’ve often done a clip show that involves:

A. Clips from films like the Lewtons, or the Schary-Rapf films at MGM (like Pilot #5 and Joe Smith, American), or one of the series films, like a Maisie film. These films show that the resources of a big studio, such as talent, standing sets, skilled cinematography and editing departments, etc, could generate a film that, while it might have been double feature fodder, still maintains a sense of `quality’ that, perhaps, studios wanted to maintain for purposes of brand equity.

B. Clips from fairly awful B’s, like the Dick Tracys or Tim Holt Westerns at RKO, which show what could happen when questions of production value were not attended to quite so scrupulously, simply because, given the films’ titles, they were likely to draw from a market which did not make attendance decisions in the same way as patrons of, say, Pilot #5.

C. Clips from minor studio “B” westerns, ala Buck Jones. REALLY gets the point across about the relationship between production expenses and expected grosses; clearly, these films were made on a precise calculus. As films, of course, they’re nowhere near as interesting as the Lewtons or RKO “B’ noirs like The Devil Thumbs a Ride, but they work, particularly when students can’t really tell the difference between a Buck Jones, a Tom Mix, or a Three Mesquiteers – that’s sort of the point. Peter Stanfield’s work on “B” Westerns, however, shows how the signifying practices of the B Westerns, production values aside, could be truly divergent from anything in the A film canon, and worth studying. But in defense of my students, being trapped in a screening room with a true B Western at full length can be a grueling experience.

*A handout listing the films produced in a single given year by one studio, grouped by genre, and with A or B indicated in each case. 1939 is a good year to do this with, as it contains some of the few studio films students have even ever heard of. They can see how certain studios specialized in certain genres, and how B’s supported A’s in the production calendar.

*Finally, by way of an outro, of course, talking about modern equivalents of B films, and even arguing whether such equivalents exist in the film or cable marketplaces. (Jim Naremore’s chapter on direct to video “erotic thrillers” in his wonderful book on noir, More than Night, can be very helpful here.)

Our researchers retire from the field. But not for too long.

Day 2: Diving for Dollars

Brad Schauer, Ph.D. candidate at UW-Madison fires this off at 9:33 CST on 7 February:

Wow, what a digest I received this morning! With all this B movie talk, I couldn’t resist adding my $.02.

The Black Cat is a tricky case – it was worth flipping through some of the secondary sources to investigate (Senn 1996; Weaver, Brunas, and Brunas 1990, Soister 1999). In a sense, it’s a clear B. The budget was about $90K and was scheduled for a two-week shoot. Compare this to next year’s Bride of Frankenstein, which cost $400K and took Whale about six weeks to film. Plus, Black Cat has all the wonderful hallmarks of a quintessential B: lurid storyline, short running time, sometimes incomprehensible narrative (due in this instance to censorship), etc.

And it was devalued by the critics because of its genre and the concomitant transgressive material (the flaying scene is still shocking).

However, the film was also a big hit for Universal, its top moneymaker for 1934. Looks like it brought in rentals around $250K – which isn’t a lot, but it suggests a percentage release, at least in its initial run. Variety also said it had “box office attraction” because of the current popularity of Lugosi & Karloff, teamed for the first time. Someone would have to investigate its distribution patterns to be sure, but it kinda looks like a B picture that was sold as an A, as Lea suggested. Maybe Universal knew it could throw a cheap movie out there and it would succeed based on the popularity of the genre and the stars. It’s a kind of precursor to all those low-budget, highly-profitable horror films like Halloween and Saw. So for me it’s about 4/5th B, 1/5th A.

Would I show it as an example of a B? As Kevin Hagopian mentioned, it’s really much too good to be a truly representative example, but students will probably like it more than a Dr. Kildare movie or something. If you really want to sock it to them, dig into the Sam Katzman filmography. Try one of the Jungle Jims or the Lugosi Poverty Rows.

David already mentioned the real gems of the studio Bs, the Motos. The Chans are great too. (I can even watch the Monogram Chans, although the Karloff Mr. Wongs can be a real slog.) As far as other mystery series go, the Universal Holmes films are extremely well done, the Dick Tracys, Perry Masons, and Torchy Blaines are a lot of fun, and I have a soft spot for the Falcon films due to AMC early morning reruns in my childhood. The Kitty O’Day mysteries are on my “to watch” pile, but I’m not optimistic. Follow Me Quietly (1949) also comes to mind as a great B-noir.

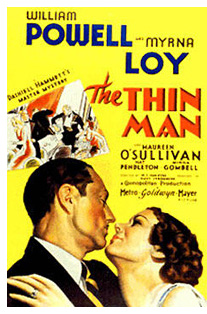

And also, the Thin Man movies weren’t really Bs. Not responding to anyone – just needed to get that out there. Closer to Bs would be MGM’s Sloan mystery knockoffs, which are fun too (especially Fast and Furious, which is fortunate enough to have Rosalind Russell).

Whew, thanks for reading if you made it this far.

As a new day dawns on Texas, Kevin Heffernan has more thoughts.

Thanks for the info, Brad. Yes, Black Cat is a curious hybrid case. For a “truer” example of a Karloff/Lugosi B from Universal, see The Raven from the following year–most notably in its use of fairly minimal, obviously left-over sets (nothing like the very bold production design of Black Cat). And, although I recall that Kristin is a Lew Landers fan (didn’t she call him “lightly likeable at least” in Breaking the Glass Armor?), his name was somewhat synonymous with quotidian program pictures in the 30s and 40s.

Thanks for the info, Brad. Yes, Black Cat is a curious hybrid case. For a “truer” example of a Karloff/Lugosi B from Universal, see The Raven from the following year–most notably in its use of fairly minimal, obviously left-over sets (nothing like the very bold production design of Black Cat). And, although I recall that Kristin is a Lew Landers fan (didn’t she call him “lightly likeable at least” in Breaking the Glass Armor?), his name was somewhat synonymous with quotidian program pictures in the 30s and 40s.

My assertion that Black Cat was an A referred to my understanding of the terms of its first-run distribution . But I actually had little evidence, I have discovered, as I looked over my notes on the movie from Tino’s seminar a few years back.

Lea and Doug’s observations about Universal’s “Little Three” status and the general role its horror pictures played in the larger patterns of distribution seem spot on to me and of course became more prevalent (inflexible, even) in the post-Laemmle years. The only exception to this that I can think of was Son of Frankenstein, which was U’s entry in the superproduction cycle of 1938-39 (stars on loan from other studios, spectacular production design, initial plans to shoot in Technicolor, etc), but that movie was really the last gasp of the A horror pic at the studio, I think.

And at 10:10 AM CST Lea Jacobs is back at the keyboard.

I guess Brad has the last word on The Black Cat. Nothing like doing the research.

Now about the Thin Man series. In the essay on film budgets at MGM that appeared a few years back, I recall that these films were in the “B” range for MGM (about $250,000). (See H. Mark Glancy, “MGM Film Grosses—1934-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, 2, 1992: 127-144.) This is a lot of money relative to what other studios were spending on B films, of course, but all of MGM budget ranges were high relative to the other majors (the average MGM A was between $700,000 and $1 mil as I recall). So I agree that the Thin Man films are elegant and well dressed and don’t fit anyone’s conception of a B, but at least when considered from the perspective of film budget categories at MGM, wouldn’t these count as Bs? Or, put another way, what would you count as an MGM B?

Now about the Thin Man series. In the essay on film budgets at MGM that appeared a few years back, I recall that these films were in the “B” range for MGM (about $250,000). (See H. Mark Glancy, “MGM Film Grosses—1934-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, 2, 1992: 127-144.) This is a lot of money relative to what other studios were spending on B films, of course, but all of MGM budget ranges were high relative to the other majors (the average MGM A was between $700,000 and $1 mil as I recall). So I agree that the Thin Man films are elegant and well dressed and don’t fit anyone’s conception of a B, but at least when considered from the perspective of film budget categories at MGM, wouldn’t these count as Bs? Or, put another way, what would you count as an MGM B?

Doug Gomery adds in re MGM B-pictures:

Nicholas Schenck was no great man, but he ran Loew’s/MGM from 1927 to 1954. To him the Thin Man series were Bs from his studio. Remember block booking? These simply made MGM a more attractive package. The question of A v. B is at its heart a budget decision and then a release one. The New York-based men, like Schenck, made those decisions.

Day 3: B Mania Subsides; some answers, more questions

8 February: Brad Schauer revisits Nick and Nora:

Real quick about the Thin Mans before I run to lecture: I know I was being a bit contentious when I said they weren’t Bs. Lea and Prof. Gomery are absolutely right that if you go by budget, they’re Bs…at least initially. But by the time we get to Another Thin Man (1939), the budget is up to $1.1 mil, only a couple of Gs less than Ninotchka. 1944’s Thin Man Goes Home is budgeted at $1.4 mil, only about $500K less than Meet Me in St. Louis (!).

Real quick about the Thin Mans before I run to lecture: I know I was being a bit contentious when I said they weren’t Bs. Lea and Prof. Gomery are absolutely right that if you go by budget, they’re Bs…at least initially. But by the time we get to Another Thin Man (1939), the budget is up to $1.1 mil, only a couple of Gs less than Ninotchka. 1944’s Thin Man Goes Home is budgeted at $1.4 mil, only about $500K less than Meet Me in St. Louis (!).

Another reason they don’t seem like Bs to me is that they were consistently among the top grossers for MGM in the ’30s. But so were the Andy Hardys, you might argue, and they’re clearly Bs.

Except…from what I could tell from analyzing the distribution patterns of the ’35-’36 season (not done this morning, don’t worry), After the Thin Man played in major first run theaters, and hardly ever with a second feature until it hit the nabes (neighborhood theatres). It was distributed like a big deal A, and you can sense the exhibs’ excitement in the trade press that another Thin Man installment was coming out.

Finally, we can look at the running times. MGM’s Bs were sometimes longer than other studios, but the first sequel After the Thin Man is nearly two hours long. Compare that to MGM’s Sloan mysteries (Thin Man knock-offs), which clock in at 75 minutes each.

So, like The Black Cat, the Thin Man films seem an unusual case. The first installments may have been budgeted as Bs, but as the series caught on, it was treated like an A property, both in terms of production and distribution – compared to the Andy Hardy films, for instance, whose budgets remained quite low for the entire series.

Although I think the Hardy films were often exhibited as the top of a double feature, but that’s another story.

I kinda feel like lecturing on this stuff this morning instead of the continuity system, although I’m not sure the students will want to hear about distribution patterns at 8:30 a.m.

Lea Jacobs’ fingers fly over the keyboard a few moments later:

Lea Jacobs’ fingers fly over the keyboard a few moments later:

This is very interesting, Brad. I wonder if any of this could be correlated with William Powell and Myrna Loy’s salaries? That is, maybe the series made them stars (I am pretty certain that they were not prior to the first of the series). Higher budgets for later Thin Man films might have been a function, not only of more expensive settings and shooting practices, but also of MGM raising the stars’ pay.

Anyway, it might be worth looking at the publicity attached to the two stars over the course of the series and see if it increased and if it changed. I don’t know of any source that would tell you what they were paid (at least any source that can be trusted) although contracts might exist at AMPAS.

And then, of course, there is the question of whether or not the cutting rate went down over the course of the series…

This last remark refers to an email entry of my own, sent about the same time:

I have another idea about how to spot a B. It isn’t infallible, but it might serve as an index. I’m thinking Average Shot Length.

Oho, you think, here we go again. But hear me out.

Last night I watched THE DEVIL THUMBS A RIDE, a 62-minute RKO item from 1952, directed by Felix Feist. Laurence Tierney is the most recognizable name in it, and if you know him only from RESERVOIR DOGS, you might not recognize him. Good suspense, very few sets (lots of car driving with background process plates), familiar character actors wandering in to do a bit part (including Harry Shannon, aka Charles Foster Kane’s father). A surprisingly violent twist at one point. Even the title tells you you’re watching a B.

Last night I watched THE DEVIL THUMBS A RIDE, a 62-minute RKO item from 1952, directed by Felix Feist. Laurence Tierney is the most recognizable name in it, and if you know him only from RESERVOIR DOGS, you might not recognize him. Good suspense, very few sets (lots of car driving with background process plates), familiar character actors wandering in to do a bit part (including Harry Shannon, aka Charles Foster Kane’s father). A surprisingly violent twist at one point. Even the title tells you you’re watching a B.

And 6.0 second ASL.

We found in our Hollywood book [The Classical Hollywood Cinema], and pretty reliably since, that during the 1930s-1950s the Hwood norms ranged from 8-11 seconds per shot. But those samples were drawn, I increasingly realize, from mostly A pix, because in the vast initial filmography we compiled, what we found in archives tended to be A pix. Only William K. Everson had a substantial collection of B titles on our first list, more even than the Library of Congress.

So maybe Bs tend to be cut faster? Here are some other ASLs from the 1930s, from B or B+ items: Murder by an Aristocrat, 6.3 seconds; Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase, 6.8; Indianapolis Speedway, 5 seconds; Tarzan the Ape Man, 6.6 seconds; Tarzan Finds a Son, 3.6 seconds!

From the 1940s: Parole Fixer, 6.6 seconds; Chain Lightning, 6.3; Framed, 6.3.

Now this mini-sample has skewing problems of its own–lots of mystery and action pictures. We’d need to test it with other genres. Can there be fast-cut musicals? (Actually, yes; Footlight Parade.) Comedies? (Yeah, Duck Soup.) Melodramas? (Yep, Mr. Skeffington.) Still, I don’t have enough from any genres to say much of substance. As for our two big horror examples, The Black Cat falls in the A-picture range (8.5 seconds), while The Raven is much faster cut (5.7 seconds).

And what about the real Bs–the Westerns from Monogram et al? Plenty of them play on TCM and we have tons sitting in the Wisconsin Center for Theater Research, but I confess to having watched only a handful and never counted shots. Also, films with lots of stock footage (travel, racetracks, jungle animals, etc.) tend to be cut faster…and we know that Bs use lots of stock footage.

Interestingly, of major directors I’ve sampled, Hitchcock’s ASLs come closest to the ‘B’ touch. Selznick famously told Hitchcock to slow down the pace because his British films were too “cutty”; was there an unspoken belief that fast cutting was a little downmarket if you were making A pictures? Hitchcock sometimes cut fairly fast (until Rope and Under Capricorn, of course): 6.4 seconds for Lifeboat (on right), 7.3 for The Paradine Case, 6.8 for Notorious.

Interestingly, of major directors I’ve sampled, Hitchcock’s ASLs come closest to the ‘B’ touch. Selznick famously told Hitchcock to slow down the pace because his British films were too “cutty”; was there an unspoken belief that fast cutting was a little downmarket if you were making A pictures? Hitchcock sometimes cut fairly fast (until Rope and Under Capricorn, of course): 6.4 seconds for Lifeboat (on right), 7.3 for The Paradine Case, 6.8 for Notorious.

ASL can’t be an infallible detector because there are some Bs with ordinary ASLs, and a few with longish ones. Detour clocks in with an unusually lengthy 14.3 second ASL. Joseph H. Lewis’ The Big Combo (1954), made for Allied Artists (the revamped Monogram), boasts an ASL of 14.6 seconds and has many single-shot sequences (though given its cast and technical credits, it’s arguably a B+). Still, most marathon ASLs seem to come in A pix by Minnelli, Preminger, Wilder, and their peers.

What makes this stuff interesting is a long-standing assumption that because of short shooting schedules, B films couldn’t afford many camera setups. I think there’s an unspoken belief that directors used longer takes to get more footage per day. The shot length averages suggest the opposite: B films can use lots of shots, and a surprising variety of setups.

This may also suggest a difference between A studios making B pictures and Poverty Row studios making only B pictures. Again, my sample is slanted toward the former. Nevertheless, although faster than normal cutting isn’t a necessary condition of a studio-era B picture, it may be a symptom of one. If other indicators point toward a B, and you’ve got an ASL of less than 7 seconds, that could strengthen the case.

Scott Higgins of Wesleyan University raises a new question about my ASLs:

Fascinating. Are shot scales different as well? Might editing compensate for cheaper mise-en-scene? In any case, this is good evidence that staging takes time!

Coming full circle

On 8 February, at 8:00 CST, Paul Ramaeker, who started it all two days earlier, writes:

Wow! Thanks to everyone for their input on this; now I just have to sort through everyone’s arguments and make a judgment call (given the degree of controversy over the question). I have to say, though I have now been convinced to use Detour as one of my screenings for that week, so as to have an example of Poverty Row, it would seem that either Black Cat or Zombie would work (as well as a Moto, which I hadn’t thought of at first), not least because there is some element of ambiguity in both cases that would be fodder for discussion.

Wow! Thanks to everyone for their input on this; now I just have to sort through everyone’s arguments and make a judgment call (given the degree of controversy over the question). I have to say, though I have now been convinced to use Detour as one of my screenings for that week, so as to have an example of Poverty Row, it would seem that either Black Cat or Zombie would work (as well as a Moto, which I hadn’t thought of at first), not least because there is some element of ambiguity in both cases that would be fodder for discussion.

I have to say, though, I think the reminders about the status of the Little 3, as well as the budgetary info, are kinda persuasive in the case of The Black Cat. And while I’d hate to lose Zombie, I can see some value in screening two films at different production levels by the same director, Ulmer in this case. There may well be such a thing as too much Ulmer, but if anyone could possibly object to a Black Cat/Detour double bill, they’d have to be kicked out of the class.

Cheers to all!

Weekly colloquium meeting of the Film area, UW–Madison

Walk the talk

The Magnificent Ambersons.

“It’s only history,” Jack Valenti is reported to have said when allowing scholars access to MPAA files. (1) After studying Hollywood for over thirty years, I should be used to the ways in which trade journalists (and some critics) forget or ignore historical precedents in moviemaking. But I still get bug-eyed when I encounter something like the Variety piece on TV director Tommy Schlamme (Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip).

The subhead tells us that this DGA nominee is known for his “hallway shots.” That gets my interest.

I lose interest fast. The writer tells us that Schlamme

developed the “walk and talk” on Sports Night and then mastered it on The West Wing.

The shot—which features two or more actors moving from one location to another on the set, often from one office to another via a hallway—has become a Schlamme signature.

The first sentence could be read as saying that Schlamme invented the walk-and-talk. Since I spent a little time studying this technique in The Way Hollywood Tells It, my inner film historian cries out, Aarrgh. Long before Sports Night (aired 1998-2000) and The West Wing (1999-2006), movies were developing such bravura shots.

The oblique view

In the prototypical walk-and-talk, two or more characters advance, and the camera tracks along, keeping them centered as they move through the environment. Such shots are quite uncommon in the silent cinema, but they emerge in 1930s films from many countries.

They were truly “signature shots” for Max Ophuls and the lesser-known Erik Charell. In Charell’s captivating The Congress Dances (1931) Lillian Harvey sings while a carriage takes her through an entire town and into the country, all in flowing tracking shots. Call it a ride-and-sing.

If that’s not as pure an instance as you’d like, we can find nice ones during a street scene of The Thin Man (1934). A more somber example occurs in Mizoguchi Kenji’s Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), with the camera in a river bed angled upward at the couple it follows.

Usually such traveling shots from the 1930s and 1940s are shot obliquely to the actors. That is, the performers are seen in a ¾ view, and they walk along a diagonal path with respect to the frame edges; the camera moves on a similar trajectory. Sound cameras were mounted on dollies that usually ran on tracks. Framing the actors head-on raised problems with this gear. Performers couldn’t walk smoothly if they were stepping within rails, and there was a risk that the rails in the distance might appear in the frame. It was simpler to set the camera at an oblique angle so that actors could walk unimpeded and the tracks wouldn’t be seen. Directors continued to use this framing into the 1950s, as in Welles’ Othello (1952) and Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957). Both are unusually long takes; in the second, poor Gene Barry seems to be panting to keep up with the other men.

Back off

Today’s walk-and-talk is more likely to be a head-on framing, with the camera retreating from the actors. (More rarely, it dogs them from behind.) With a retreating Steadicam, you don’t have to worry about glimpsing the ground or floor behind the actors, in the distance, since there are no track rails to be exposed. Again, though, we have some precedents, most famously the splendid camera movements, evidently executed with a crane, in the ball sequences of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), when George and Lucy stroll through the party.

When location shooting became more common in the 1940s and 1950s, cameras could be supported on more versatile dollies that didn’t require track rails, and these reverse-tracking shots become a bit more common. Kubrick, highly influenced by Welles and Ophuls, captured his officers striding through the trenches of Paths of Glory (1957). Vincent LoBrutto’s information-packed book (2) tells us that Kubrick’s dolly rolled backward on the planks that the actors walked on (authentic details, as boards were indeed used in the muddy trenches). Godard’s long traveling through the office lobby in Breathless (1960) was shot from a wheelchair.

Such head-on (and tails-on) shots can be found in several films well into the 1970s, as in Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1970). In fact, hospitals, police stations, and other sprawling institutional spaces seem to invite this approach.

By the 1980s, these shots proliferate in American films largely because the Steadicam makes them easy. One famous example is De Palma’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), which follows the drunken Peter Fallow through a hotel as he picks up and drops off many other characters.

Today such shots are very common in both high- and low-budget films. Schlamme’s “signature” device seems to be in pretty wide circulation. At best it’s a convention, at worst a cliché.

They’re called actors; let them perform action

I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that walk-and-talk is one of two principal staging techniques of contemporary Hollywood. The other, usually called stand-and-deliver, plants the characters facing one another and simply cuts from one to the other. The scene is built primarily out of singles (shots of only one actor) or over-the-shoulder framings. Here’s a typically static dialogue scene from The Matrix Revolutions (2003).

Both stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk began in the studio era, decades ago, but then there were other options as well. Directors cultivated smooth, unobtrusive blocking tactics that moved characters in ways that reflected the developing scene. The actors had to perform with their whole bodies, and bits of business motivated them to circulate through the setting and turn toward or away from the camera. One example given earlier on this blog is from Mildred Pierce; here’s another, from the program picture Homicide (1949).

Detective Michael Landers has a hunch that the purported suicide of a former sailor is really murder. He has to persuade Captain Mooney to let him pursue some leads out of his jurisdiction. Today this might be played out in a stand-and-deliver session, with both men seated and shot/ reverse-shot cutting carrying the scene. But the director Felix Jacoves decides to let his actors earn their money through ensemble staging, not merely line readings. Here are just three shots from the middle of the scene that illustrate my point.

Landers stands at Mooney’s desk and gets a refusal. As he turns away to the left, Mooney walks to the rear files to put the papers away.

As they’re retreating to the opposite ends of the screen, Landers’ partner Boylan, who’s been offscreen for this phase of the scene, strides into the center and pauses at the door. The result of this choreography is both a balanced three-point composition and a chance to let us observe Boylan’s skeptical reaction to Landers’ next plea.

The camera tracks in as Landers approaches Mooney. Boylan shifts closer as well. What seems somewhat stagy as we analyze it doesn’t look obtrusive on the screen, because we’re following Landers’ arguments and watching the older men’s reactions. The closer framing and the position of the men, now face to face rather than separated by a desk, raises the dramatic pressure. As Landers pauses, Mooney folds his arms—a simple piece of body language that lets us know he’s still resisting.

Now a cut to Mooney, in an OTS framing, stresses his continued resistance as he tells Landers off, and a reverse shot gives Landers’ angry reaction.

Interrupting the sustained take, the shot/ reverse shot cuts have gained more emphasis than if they were part of a string of OTS shots. Jacoves has saved his cuts and closer views for a moment that raises the stakes visually as well as dramatically.

I’m not claiming that this is a brilliant stretch of cinema. (But you have to like a plot in which the hero defeats the killer by denying him access to insulin.) It’s just that the sequence activates, in a way that directors once took for granted, aspects of film art that we don’t find too often nowadays. Once you didn’t have to choose between Steadicam logistics and static dialogue; there is a very wide middle ground if you’re willing to move actors around the set and give them some body language and prop work. No need for a walk-and-talk here.

Schema and revision