Archive for the 'FILM ART (the book)' Category

Subtitles 101

Rome, Open City.

Kristin here–

David and I just saw Pan’s Labyrinth at our local multiplex. It was an unusual experience. Subtitled films don’t often make it out of the art-houses and into the more popularly oriented theaters. It happened in 2000 with the surprise success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which made $128 million domestically on a $17 million budget. That’s a huge crossover, and it had people who had never seen a foreign film reading subtitles for the first time in their lives.

Many of those subtitle novices said that after a short time they got used to reading the dialogue and weren’t bothered by them. At the time it seemed as though Crouching Tiger might have broken down a barrier, and other foreign-language films would find similarly large audiences. Alas, it did not happen.

True, directors nowadays feel able to use sub-titles occasionally. Steven Soderbergh made Traffic with Spanish-language scenes, and Alejandro Gonzáles Iñárritu uses the appropriate languages for the various settings of his network narrative, Babel. Clint Eastwood, who doesn’t even speak Japanese, managed to make a whole film in that language—one that became a hit at the Japanese box office.

A new distributor specializing in art films, Picturehouse (a division of New Line) acquired Pan’s Labyrinth for U.S. distribution fully a year ago. (The film has played in most other countries before being coming out here.) Picturehouse has successfully marketed it to the large Hispanic-American audience and to fantasy fans. It also timed the release to position the film prominently for Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences voters just as nominations voting was underway. The result was six Oscar nominations: Cinematography, Art Direction, Musical Score, Makeup, Original Screenplay, and Foreign Language Film (from Mexico).

Pan’s Labyrinth is a wonderful film, with highly imaginative fantasy scenes and two major characters with whom the audience comes to strongly identify. It’s absorbing and not at all the pretentious art film of popular stereotyping. It’s a pity that anyone would miss seeing it because they believe that reading subtitles is a chore and a significant distraction.

(I ask myself, can a generation used to learning elaborate strategies for videogames and reading the various icons that appear during their fast action really be so unable to deal with some words on a movie screen?)

“Observations on film art and Film Art” has come to have a gratifyingly broad readership during its short existence, and many people who visit us no doubt regard subtitles as a familiar and painless part of filmgoing. Still, seeing Pan’s Labyrinth reminded me that we are now at the beginning of the spring semester in many colleges and universities. Almost any professor teaching introductory film courses is no doubt hearing some familiar complaints. Why do we have to watch films with subtitles? Why do we have to watch black-and-white films? Why do we have to watch silent films?

We discuss such issues in Film Art, mainly in relation to subtitles versus dubbing. Substituting different actors’ voices for the original ones destroys an important part of the original film’s style and appeal. And as everyone knows, even the best dubbing job fails to make the words we hear synchronize convincingly with the lips movements we see. Is reading subtitles really more distracting than listening to dialogue that’s clearly not coming from the people on the screen?

What we don’t discuss much in the book is the more important reason for watching films with subtitles, shot in black-and-white, and made in the era before sound was introduced. It’s simple. Avoid those films, and you deny yourself access to a vast potential for exciting movie-going experiences. The approach we took to choosing examples for Film Art reflects that fact. We mentioned as many types of films as we could, drawing on a wide range of national cinemas and periods.

I suspect that a lot of students come into their first film course thinking they know a lot about the cinema. This was certainly the case for me. During the 1960s, when I was in high school, I had lived in Miami, so there were a number of art-houses that I could get to on my own, thanks to my new driver’s license.

I saw a lot of films that I suspect my classmates would have thought of as esoteric. One repertory house ran 1950s and 1960s Alec Guinness and Peter Sellers comedies. Another had more recent imports: Georgy Girl, The Knack, and Darling from swinging England, Zorba the Greek (which, though from Greece, was in English), and Marriage Italian Style, with actual subtitles.

I was also naive enough to think that the Oscars really went to the best films of the year. (I’ll be posting on that topic next week.) I tried to see as many of them as I could, which meant that if I wanted to see the older ones in those pre-home-video days, I had to catch them on TV. I also saw The Pawnbroker, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, A Man for All Seasons, Bonnie and Clyde, and other prestigious films when they first came out, and I thought myself very sophisticated for doing so. The only auteur whose name I recognized was Hitchcock, so I saw Torn Curtain in first run. I couldn’t figure out what all the fuss was about, and it wasn’t until I started taking film classes that I found out.

I don’t recall that reading subtitles ever caused me any problems in those days. They never bother me, except of course when they’re printed white-on-white—or when they’re in French, which I can’t read quickly enough to keep up.

So when I went off to the University of Iowa in 1967 to study theater design, I had seen black-and-white films and subtitled films. I had never seen silent ones, except for maybe a few Chaplin shorts run at sound speed on TV. There weren’t all that many silent films around in those days. The great revival in the study of silent cinema was just starting, and it really got rolling in the 1970s. So vague was my knowledge of film history that I thought The Birth of a Nation was the first film ever made.

I took my first film course in the spring semester of 1970s. It was an introductory film history class, taught by Dudley Andrew. (The University of Iowa had been offering a Ph.D in cinema for only a few years, and Dudley himself was a graduate student at the time. Three years later I was his teaching assistant for that same course.) I took it because I had a busy schedule working on theater productions, and it was literally the only course in the whole department (film and theater were in the same department in those days) that didn’t conflict with my other commitments.

I had kept going to films at art-houses during my undergraduate career, and as the semester began I still thought that I knew quite a bit about the cinema.

Early that semester two things happened that changed that belief. First, someone from the Library of Congress came and gave a talk, which I attended. He showed some recent restorations: a very early French comedy with hand-stenciled color and George Méliès’s 1905 film Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en 2 heures (which for years I thought of as From Paris to Monte Carlo). In the latter, the miraculous car that made the journey in an impossible two hours was hand-painted red. It wasn’t the neat hand-painting that used stencils, though. It was blobs of paint daubed onto each frame in the general area of the car, with the rest of the image left in black and white.

The result was a wavering red patch that moved about in the general vicinity of the car, overlapping its outlines, as if the car were on fire. It was quite unlike anything I had ever seen. The film itself is quite funny, but the alien color utterly charmed me. I began to suspect that the cinema held treasures that I had never dreamed of.

A short time later, Dudley showed Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari for the film-history class. It’s a 1920 German Expressionist film, a classic that shows up on the screening schedule for many courses. This time I was bowled over. Again, it was totally different from anything I had encountered before, and I gave up my idea that I knew anything significant about the cinema. From that point, I cut way back on my theater-production activities and took film classes, going on to graduate school in that subject. I had embarked on a lifelong project of learning about the cornucopia that was the cinema, past and present, American and foreign. It has been a wonderful journey, and it is still going on.

Obviously not everyone going into a film class will have this sort of life-changing experience. Still, it could be an experience that has a lasting impact by broadening and enriching the experience of filmgoing.

This is why students should welcome the chance to watch subtitled films, black-and-white films, and silent films. After all, what is the point of taking a film course, especially if it’s an elective class, if we reject unfamiliar sorts of movies? If professors taught only recent English-language color films, they would only be doing half the job. Yes, students could learn all the formal principles and cinematic techniques we lay out in Film Art, and they would probably go away with an enhanced ability to watch a film. They still wouldn’t have any idea of all that the cinema, as it has existed from the 1890s on, has to offer.

I believe that some of the reluctance to experience new sorts of films comes from two faulty perceptions. First, people still tend to think of the cinema as a lesser art form than classical music or painting or theater or literature. Second, people often think that because they’ve been watching movies all their lives, they know more about them than they do about classical music or painting or theater or literature.

Neither is true. The cinema has produced films that are great works of art. One can’t just look at modern blockbusters and conclude that the cinema is doomed to be puerile entertainment. A disturbing number of educated people who do know something about classical music and painting and theater and literature have never heard of Jean Renoir and Sergei Eisenstein, let alone Yasujiro Ozu and Jacques Tati.

Would the same students who don’t like the idea of watching black-and-white films go to the professor in a course on art history and complain about being shown engravings by Rembrandt rather than his paintings? Would they listen to an opera in a music class and complain because it’s in Italian? Would they read a Shakespeare play and complain that the language is just too weird? I suppose a few would, but students going into such classes usually understand that they are going to be confronted with artworks of a type they’re not familiar with.

And for those who feel they know a lot about films, they would do well to adopt a little of the humility that I felt after seeing that strange little red car and the bizarre style of Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. I realized that going to a lot of current American movies barely scratches the surface.

My name is David and I’m a frame-counter

DB here:

Elsewhere on this site and in Figures Traced in Light (Chapter 1) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (second essay), I sometimes say rude things about the rapid editing in today’s films. But I’m actually a fan of fast cutting–when it’s precise, functional, and thoughtful. Most directors today don’t think about their cuts. Godard: “The only great problem of cinema seems to be more and more, with each film, when and why to start a shot and when and why to end it.”

My interest in fast cutting goes back to the 1960s, when I was first reading Eisenstein and seeing fims by Godard, Truffaut, Hitchcock, and, yes, Richard Lester. At first I would wind sequences backward and forward on a 16mm projector, stopping to pull the film off the reels to hold up to the light. For my dissertation on French cinema of the 1920s, I had a chance to examine films by Abel Gance, Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac, et cie on editing tables or rewinds. In quickly-cut passages, the patterns of shot-length showed how a director could control the visual pace.

Over the years, when I studied 35mm film prints regularly, I periodically returned to my love of rhythmically cut passages. I studied Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the work of the Soviet Montage directors, and Asian action movies, from 1920s Japanese swordplay items to 1990s Hong Kong martial-arts sagas. Somewhat surprisingly, I found that Ozu, as in everything else, was there too; a lot of his intermediate spaces (landscapes, objects in rooms) are cut arithmetically.

By examining 16mm and 35mm prints, I could measure shot lengths in frames. In a sound film, a 24-frame shot would last a second on the screen. Things were trickier in gauging the cutting of silent films, since they were shown at rates between 16 and 24 frames per second. But at least the number of frames per shot gave me a sense of rhythmic relationships. A sequence in Jean Epstein’s Chute de la Maison Usher (1928) displays an arithmetical unfolding that would yield a distinct tempo at any projection speed of the era.

Directors have been counting frames for a long time. Experimental filmmakers like Brakhage did. Ozu had a special stopwatch built to register feet and frames during filming. Hitchcock cared about frame counting too. In Film Art‘s chapter on editing (pp. 224-225 of the new edition), we show how the gas station fire in The Birds gains impact from its steadily shorter shot lengths. The first shot lasts 20 frames, the second 18, the third 16, and so on down to 8 frames.

In sum, frame counting is one valuable way to find how a director can govern the pace of our pickup. When shots come this fast, our involvement can quicken as well.

When 35mm plays us false

For silent films, counting frames can be a problem if you have a “stretch-printed” copy. Since silent films often ran at something less than 24 frames per second (sound speed), some later film versions have been printed to repeat frames at certain intervals, to stretch out the print to 24 fps. That makes it easier to add a synchronized score to the print.

In the 1970s the Soviets were big fans of this procedure, rereleasing many classics by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and others in stretch-printed 35mm and 16mm copies. The Soviet Montage filmmakers definitely counted frames, calculating the shots to play off each other rhythmically, so adding extra frames spoiled things. Worse, the stretch-printed versions often played sluggishly at sound speed, making the action spasmodic and blurring the figures. The result completely wrecked the rhythmic effects the directors were after. Even today, stretch-printed copies of Eisenstein’s Strike are in circulation.

Videotape and the 3:2 pulldown

Videotape arrived. The first Betavision players measured something–a little tally counter clicked away–but you couldn’t be sure what was being counted. Then came digital displays that measured hours, minutes, and seconds. But what about frames? When I tried to count frames on videotape, I found that the figures didn’t match those I got from film frames.

To see why, we have to remember that television developed its own frame rates. The technical details can get pretty daunting; see here for one account. I also recommend Jim Taylor’s DVD Demystified and Kallenberger and Cvjetnicanin’s Film into Video. Still, we non-engineers can get a general sense of what’s at stake.

There are two primary television standards, NTSC and PAL. NTSC (for National Television System Committee) is used primarily in North America and Japan. PAL (Phase Alternating Line) is common throughout Europe and Asia. Because NTSC video operates at a 60-Hertz refresh rate, the rate for individual frames is close to 30 per second. (Actually, it’s 29.97 fps.) The problem is this: Do you run 24-frame movies at 30 frames per second on television? This would make them look speeded up. Or do you pad out a second of film to fit a second of TV? American engineers took the second solution and created the so-called 3:2 pulldown.

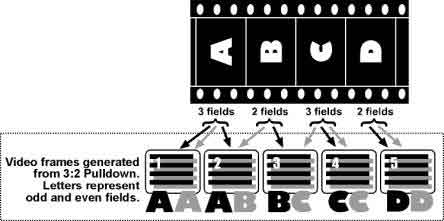

In interlaced video, each “frame” is really two venetian-blind image fields presented as one image on your screen.(1) In the 3:2 pulldown, some film frames are selectively repeated to fill out the video playback format. The film is converted to video by making two fields from one film frame and then three from the next frame. Here is a useful diagram from a site on video transfer.

The 3:2 pulldown preserves three of the original four film frames (video frames AA, CC, and DD above).

But you don’t see this exactly this result when you jog/shuttle through a videotape frame by frame because the VCR has been engineered to display the 3:2 pulldown slightly differently. Stepping through a videotape, we find that some frames will show phases of movement and some repeat a phase. Depending on your playback machine and the tape itself, you may get varying patterns. Usually I see four video freeze-frames decomposing a movement, then they’re followed by an extra frame in which nothing changes.(2) That process turns 4 film frames into 5 display frames. Adding 6 repeated frames to the original 24 frames yields 30 video frames a second. I find that you can get a rough sense of the number of frames in the original shot by ignoring the repeated frames in the video display, but the video frames showing decomposed movement may or may not correspond to the actual film frames.

Laserdiscs and the frame count

Those heavy, rainbow-flashing 12″ discs: Cinephiles loved ’em. They gave us a sharper picture, properly letterboxed, along with terrific sound. Aficionados today still prefer the rich digital sound of laserdiscs to the compression of many DVDs.

Most laserdiscs used the CLV (Constant Linear Velocity) format, which preserved and even exaggerated the effects of the 3:2 pulldown. Counting frames meant stepping through the stills and ignoring the repeated ones, as with videotape, but often the coupled frames (AB and BC above) shivered wildly. But in the high-end CAV (Constant Angular Velocity) format, laserdiscs were able to make each stored frame pristine. This is why people thought that laserdiscs would be used archivally, for storing paintings, photographs, manuscript pages.

A bonus of the CAV format was that in transferring motion pictures to disc, one film frame could be matched to a single video frame. In fact, each film frame was assigned its own number, so the counter display spit out digits with blinding speed. During normal playback, the 3:2 repeated frames were added in, but in STEP mode, CAV laserdiscs gave you the original film frames one by one–steady, crisp, and bright. Frame-counting gained a new piece of hardware.

DVD and frame counting

Laserdiscs used optical analog technology for the image track. But consumers wanted something easier to handle, on the model of the music CD, so in came digital image technology via MPEG-2 and the DVD.

Despite all the differences between digital video and film (color, resolution, artifacts, etc.), DVDs in the NTSC format gained one advantage over tape. Like CAV laserdiscs, they could preserve the 24-frames-per-second rate of film. Essentially MPEG-2 technology encodes the film frame by frame. Flags on the DVD instruct the player to regenerate extra frames during playback. For a more detailed explanation, go to Dan Ramer’s article here.

The result is that during freeze-frame viewing, a DVD can yield the original film frames. Watch the Universal DVD of The Birds, and the frame-counts correspond to the 20-18-etc. layout we discovered on a 16mm print. Your remote’s STEP button moves through the original frames, hiding the repeated ones that were shown during normal playback.

But not always. DVDs can sometimes play us false.

Before the DVD was a gleam in Warren Lieberfarb‘s eye, I studied King Hu’s wonderful A Touch of Zen on an editing table. There is a lot of frame arithmetic in the editing. During one swordfight, the mysterious stranger leaps away from the blows of Miss Yang and lands in a medium shot. He steps back, tipping up his face to reveal that she’s bloodied his head. He stares in astonishment. The shot lasts only 20 frames.

Yang stands still, holding her sword at the ready. The shot lasts a mere 9 frames, which dynamizes her stillness.

The stranger turns and runs out of frame in another twenty-frame shot. The static shot of Miss Yang now becomes an abrupt punctuation, and the stranger’s panic registers on us more sharply by being caught up in a repetitive rhythmic pattern.

Yang plunges after him, in a twelve-frame shot.

All four shots add up to less than three seconds of screen time, but they’re completely legible. It seems to me that the shots accentuate a pause in the fight by inserting a striking micro-rhythm, and then they dissolve that by letting the fighters continue the combat. Would that today’s filmmakers thought out their cuts so precisely! (If you want to learn more about King Hu’s editing style, see my Planet Hong Kong and the essay on him in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.)

But if you examine these shots on the US DVD of A Touch of Zen, you’ll find that the number of frames is way off from the film. The first and third shots run 25 frames each, not 20 frames; the second shot runs 11 frames (instead of 9), and the fourth 15 (instead of 12). Why? Inspection reveals our old friend, the 3:2 pulldown, at work. Improper authoring has left in the frames that should be jettisoned in step playback.

An even more severe instance: The sequence from Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher that I admired in my dissertation days. It has become hash on the US DVD. When I try to count frames, I find that apparently the silent original has been stretch-printed and subjected to the 3:2 pulldown. When I click through the frames on a DVD player, I find that many frames are repeated, and some shots have doubled in length.

The lesson: Not all DVDs are created equal, or equally accurate in their correspondence with the original film.

What about PAL?

NTSC interlaced video has a 60-Hertz refresh rate. But PAL has a 50-Hertz one. That means not 30 video frames per second but 25. What do you do in transferring a film? The obvious answer: You speed it up.

Films shot at 24 frames per second tend to run at 25 in PAL videos, both tapes and DVDs. As a result, many films on European video run shorter than they did in the theatre, or on American DVDs. For example, Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends runs 94:41 on the Fox DVD, but the same film, known as Mark Dixon Detective, runs 90:49 on the French DVD release. That’s a difference of nearly four minutes. PAL video playback of a 24 fps movie runs about 4% shorter than the original. For this reason, some European films are shot at 25 frames per second, to facilitate transfer to PAL.

So counting frames on a PAL videotape or DVD won’t necessarily mislead you on the number of frames, since none is repeated. That’s the case with our Touch of Zen example. Both the UK and the French DVDs of King Hu’s film yield the correct frame-counts for the shots in question. We just need to remember that each frame is onscreen for a tiny bit less time. In other words, each shot will contain the right number of frames, but that shot will be briefer in screen duration .

Note to Sátántangó fans: Yes, that means a much shorter movie. The PAL DVD available from England’s Artificial Eye claims to run 419 minutes; if you disregard opening and closing credits, the film runs a shade under 400 minutes. But the 35mm version I clocked here runs 434 minutes sans credits. So if you want to add 34 minutes to your life, watch the import DVD.

Note to Asian cinema fans: For reasons I don’t understand, many Hong Kong DVDs yield very blurred and vibrating still-frame images, not corresponding to the frames of the original film. These discs may be using a downmarket authoring process, or there may be problems converting to and fro between PAL and NTSC.

Progressive scan

This all applies to interlaced video, the original television broadcast format. Now we have progressive-scan video, for plasma and LCD displays and computer monitors. A progressive display, still adhering to the 60-Herz standard, is rigged to preserve the right number of film frames without repeating any.

But it does so by in effect combining two film frames together, and the step function may skip over several frames, or create a blurred composite that isn’t there on any frame. This is especially apparent on media-player computer software.

When I run my Touch of Zen shots on my computer, I get wildly abbreviated frame-counts in Step mode. In WinDVD, for instance, the first shot of the UK DVD registers as 8 frames, not 20; the second as 3 frames, not 9; the third as 9 frames, not 20; and the fourth as 6, not 12. Same thing for Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher. On a tabletop DVD player there are more frames than in the original film; on my player’s software, there are fewer.

For this reason, I’d avoid trying to count frames on a computer’s media player.

So…..

Frame-counting is a nifty tool for discovering some secrets of filmmaking, but when we work from a video copy, we need to keep in mind the constraints of the various formats. And whenever possible, check the film!

(1) To complicate things, the scanning of alternate raster lines never yields a single complete frame. Before the image is fully completed at the bottom, it’s being refreshed at the top! To this extent, the video frame doesn’t have the stable, singular identity of a film frame. It can be encoded to correspond to a film frame, but as an image display, even a frozen frame is always in the process of being filled in. It’s just that our eyes, not designed to track such small-scale processes, are fooled.

(2) A quick sampling of my old VHS tapes shows that occasionally a tape doesn’t exhibit effects of the 3:2 pulldown. My Facets VHS copy of Where Is the Friend’s Home? plays back on two machines without any repeated frames. Perhaps this comes from making the transfer from a PAL master tape?

From Hollywood to Atlanta to us

DB here:

Some day Ph. D. students will be writing dissertations on the contribution of Turner Classic Movies to US culture. I’d argue that Ted’s baby is as important to our collective sense of cinema history as the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art Film Department was.

As a movie fan, I’m overwhelmed by the chance to see so many of my favorites for the cost of monthly cable. As a film researcher, I find myself feeling as if a film archive dumped a dozen movies on my front lawn every morning. In 1990, my colleagues and I would’ve killed for the opportunity to see this stuff, and now it’s whizzed to us at home. “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers again?” some of us sigh. We are so spoiled.

To refresh his core MGM-RKO-WB titles, Turner showcases items from Columbia, Paramount, Goldwyn, and other studios. The channel has become an eternal college course in cinema, with no exams or papers and all viewers happy to earn a perpetual Incomplete.

To refresh his core MGM-RKO-WB titles, Turner showcases items from Columbia, Paramount, Goldwyn, and other studios. The channel has become an eternal college course in cinema, with no exams or papers and all viewers happy to earn a perpetual Incomplete.

Why mention TCM now? Because I’m especially wrought up by what’s on offer over the waning days of January. Every day boasts many classics, so I’ll mostly skip mentioning all the fine standbys that they’re running. Here are more offbeat things I’m up for, most of which I haven’t seen.

Overturning centuries of Western tradition, TCM defines a new day as starting at 6:00 AM. Sounds reasonable to me. But check for local playing times.

Jan 21: Stolen Moments (1920): I don’t get Rudolph Valentino’s appeal, but any film from this era demands a look.

Munchhausen (1943) A textbook classic from the Nazi cinema.

Jan. 22: The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968): Trashy premise + Kim Novak + Robert Aldrich = must-see.

Jan. 23: A cornucopia. I’ll just keep the recorder going all day for:

The Black Book (1949): As oddball a film as Anthony Mann ever made, with John Alton’s pitch-black scenes turning the French Revolution into a noir nightmare. Forget the commercial DVD, evidently ripped from a 16mm print; the TCM version should look better.

Gangster Story (1959): Walter Matthau starred and directed this NYC low-budgeter.

The Guilty Generation (1931): From Rowland V. Lee, endless supplier of B’s.

The Criminal Code (1931): Excellent Hawks with Karloff. Bogdanovich paid tribute to this in Targets.

A string of Boston Blackie films, from 1941-1942: I remember this popular B series from TV syndication in my childhood. Fast-paced and punchy, with direction by Robert Florey, Edward Dmytryk, Michael Gordon, and the prolific Lew Landers.

Angels over Broadway (1940; on right): Mostly shot in one nightclub set (in the Astoria studio?), a murky drama signed by Ben Hecht and Lee Garmes. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Thomas Mitchell, and a young Rita Hayworth fill out sober long takes.

Angels over Broadway (1940; on right): Mostly shot in one nightclub set (in the Astoria studio?), a murky drama signed by Ben Hecht and Lee Garmes. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Thomas Mitchell, and a young Rita Hayworth fill out sober long takes.

The King Steps Out (1936): Hard-to-see von Sternberg.

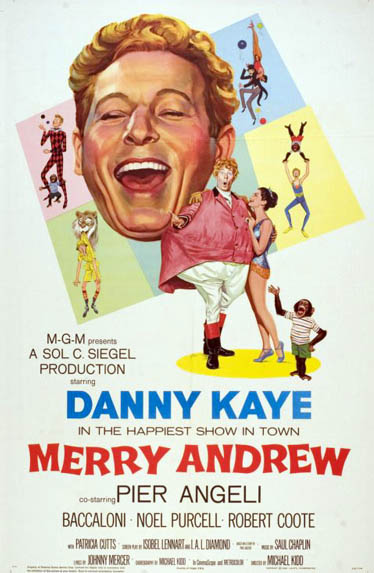

Jan. 24: Of course you’ll watch La Strada, Detective Story, The Big Carnival, etc. if you haven’t seen them. Me, I’m poised to record Merry Andrew (1958), a CinemaScope vehicle featuring Danny Kaye as an Oxbridge archaeologist. The film contains another unexorcizable ghost from my childhood, the song “Everything is Tickety-Boo.” What’s tickety-boo? Canadians know.

Jan. 25: Lots of prime stuff, including Experiment in Terror, Anatomy of a Murder, Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round, The Caddy, and several classic MGM musicals.

Jan. 26: A day devoted mostly Paul Newman and Paris, but there’s also:

The Killer Is Loose (1956): Boetticher. Say no more.

To Paris with Love (1955): Robert Hamer, director of the Ealing classic Kind Hearts and Coronets, gave us this, starring Alec Guinness, one of cinema’s finest and most modest actors.

A drive-in horror double bill courtesy William Beaudine: Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966) and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966).

Jan. 27: Of course you’ll see, if you haven’t, Gunga Din, The Yearling, The Naked Spur, The Manchurian Candidate (kinda overrated, methinks), The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (kinda underrated), The Quiet American, etc. But there’s also:

The Last of the Mohicans (1935): This, rather close to Michael Mann’s later version, I remember as being pretty solid.

A Bullet for Joey (1955): Edward G and George Raft in their sunset years; can it be bad? Okay, it can, but I’m still going to check it out.

Jan. 28: Among much good stuff, including the still poignant Umbrellas of Cherbourg, I’ll be targeting Dragnet (1954), a nifty, seldom seen feature by that unique genius Jack Webb. How often do we get an ashtray’s-eye-view of a scene? Does this cablecast portend a DVD release?

Jan. 28: Among much good stuff, including the still poignant Umbrellas of Cherbourg, I’ll be targeting Dragnet (1954), a nifty, seldom seen feature by that unique genius Jack Webb. How often do we get an ashtray’s-eye-view of a scene? Does this cablecast portend a DVD release?

Jan. 29: It’s teen dance music till prime time: Bop Girl, Rock around the Clock, Don’t Knock the Rock, Don’t Knock the Twist, Don’t Rock the Twist, Don’t Twist My Rock, etc. Might just as well keep the recorder rolling… and rocking!

Today’s outstanding piece of esoterica is The Show (1927). Every year or so I’ve been writing TCM to ask them to play this strange item from the agreeably warped Tod Browning. Let’s just say that John Gilbert plays Cock Robin and Renee Adoree plays Salome, with Lionel Barrymore chewing the scenery as the villain. Other attractions include cuckoldry, decapitation, and murderous iguanas. With a new score from TCM’s highly laudable Young Composers competition.

Jan. 30: Of course you’ve seen Ford’s stunning Arrowsmith, Pressburger’s Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, This Happy Breed, Shane, His Girl Friday, etc. But don’t forget:

The Clairvoyant (1935): the relentlessly prolific Maurice Elvey, doyen of Brit good taste, directs Claude Rains (ditto) and Fay Wray.

Strike Me Pink (1936): Eddie Cantor isn’t for all tastes, but I want to give this one a chance.

Raffles (1939): I’m a sucker for gentleman-thief stories, and with Gregg Toland as cinematographer, Sam Wood may indulge his Gothic streak, so memorable in Our Town and Kings Row.

Jan. 31: Not as strong a day as yesterday, but I’ll be checking on This Could Be the Night (1957), helmed, as they say, by Robert Wise and starring the radiant Jean Simmons (another adolescent fascination of mine), and Mitchell Liesen’s The Mating Season (1950), written by Charles Brackett and starring the fascinatingly blank Gene Tierney.

February, devoted to Oscar pictures, doesn’t contain so many marginal items, but still it’s a cornucopia of outstanding movies.

Controversial as he is, Ted Turner has proven a generous mogul, both politically and cinematically. Forget colorization! That was a bogus issue, and anyhow, for every colorized title a spanking fine-grain positive was made for archival preservation. Turner has done more than any single person to sustain and publicize the American film heritage, and he’s made it available to everyone within reach of cable. You can read more about Ted in Ken Auletta’s brisk and chatty biography.

Dorothy’s rainbow comes to earth at TCM. Watch regularly. Check the website for extra stuff, and browse the 150,000 film database. Buy the monthly program guide; it’s only twelve bucks. While you soak up the pleasure, pause to pity the cinephiles overseas. Their version of TCM, hedged by rights holder restrictions, offers mere crumbs from our bursting banquet table.

PS: Since I first posted this, film historian Doug Gomery has pointed out that Turner hasn’t controlled TCM in 12 years, but both Time-Warner bosses Gerry Levin and Dick Parsons have kept it going. We owe them thanks for refusing to ‘AMC’ it with commercial breaks and dopey gimmicks. Fortunately it makes money for TW. Long may TCM prosper.

PPS as of 23 Jan.: Lee Tsiantis of the Turner Entertainment Group adds that credit also belongs to Jeff Bewkes, who among other duties oversees the channel. So a big thanks to him as well.

Shot-consciousness

Most professional critics seem uninterested in the film shot as a shot. They might notice when the images call flagrant attention to themselves, as in Zhang Yimou’s recent films, or in those protracted walk-and-talk Steadicam takes. On the whole, though, reviewers prefer to talk about plot and acting.

Granted, it’s hard to be aware of shots, especially if you get engrossed in the story. But if we want to be fully alert to how movies work on us, we should keep our eyes open. Back in 1968, I read The Moving Image by Robert Gessner, one of the first teachers of cinema studies in the US. There Gessner offered a sturdy piece of advice: Be shot-conscious.

About twenty years later, trying to be shot-conscious and all, I started to notice a certain type of image becoming more common, especially in European and Asian films. Then it started to appear in US films as well, especially indie items. Now it’s very common everywhere, though it’s still not the predominant sort of shot.

Here’s a fairly early example, from R. W. Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969).

How to characterize it? The camera stands perpendicular to a rear surface, usually a wall. The characters are strung across the frame like clothes on a line. Sometimes they’re facing us, so the image looks like people in a police lineup. Sometimes the figures are in profile, usually for the sake of conversation, but just as often they talk while facing front.

Sometimes the shots are taken from fairly close, at other times the characters are dwarfed by the surroundings. In either case, this sort of framing avoids lining them up along receding diagonals. When there is a vanishing point, it tends to be in the center. If the characters are set up in depth, they tend to occupy parallel rows.

Linda Linda Linda (2005)

No one to my knowledge had noticed this sort of shot, let alone named it. I started to call it mug-shot framing, but I found that art historian Heinrich Wölfflin had called it planar or planimetric composition. I went with “planimetric” because that term suggests the rectangular geometry so often seen in these shots.

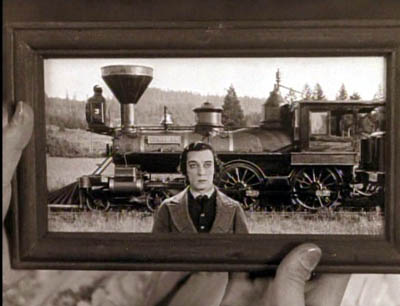

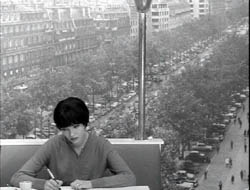

What’s striking is that such imagery is quite rare before, say, 1960. We can find some examples, principally in silent comedy and especially the films of Buster Keaton (himself a pretty geometrical director). But in the 1960s, we find Antonioni and Godard using planimetric shots fairly often.

Vivre sa vie (1962)

This image design became more popular from the 1970s onward. Why? In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I tried to trace out some sources and functions of it. Briefly, I think that the planimetric shot emerged from filmmakers’ growing reliance on long lenses, which tend to create a flatter-looking, more cardboardy space than wide-angle lenses do. A telephoto shot makes an image seem less voluminous. It seems to be made of slices of space lined up one behind another.

Filmmakers began using long lenses for many purposes, often because of the demands of filming on location. And some directors realized that long-lens optics offered fresh resources for staging and composition.

For instance, the planimetric scheme is well-suited to a “painterly” or strongly pictorial approach to cinema. In Figures, I discuss two directors who made planimetric shots central to their style. Hou Hsiao-hsien saw very deeply into the possibilities of these shots; I think he learned it from his early skill at shooting on the street with long lenses. You can find more about that here. By contrast, Angelopoulos used the planimetric image in conjunction with architecture and landscape to create a sort of de-dramatized spectacle, a spare grandeur reminiscent of icon painting.

The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991)

The functions of the planimetric image can vary a lot. Often it’s used to suggest stasis and passivity, as in the Katzelmacher instance. Kitano Takeshi picks up on this sense of torpor in certain shots of Sonatine, which suggests that being a gangster means having a lot of time to kill just hanging out.

Kitano’s use of the image also suggests a kind of childish simplicity or naïve cinema. Unlike Hou and Angelopoulos, Kitano uses the planimetric schema as if it were just the most basic way to film anything. Line up your characters and shoot ’em, as if they were figures in South Park or Cathy.

Kitano has compared himself to the kamishibai man, the street performer who narrates stories for children by flipping through illustrated cards, and Kitano’s paintings are more sophisticated, often planimetric versions of those drawings.

The planimetric schema can suggest something more oppressive too. That’s one purpose, I think, of certain shots in Terence Davies’ remarkable Distant Voices, Still Lives. The film’s stylistic system is quite rigorous in its use of straight-on compositions, and it’s worth more attention than I can give it here. For now I’ll just mention that the first part presents tableaux of unhappiness that suggest bleak family portraits.

Here and more generally, the planimetric image often carries the connotations of a posed photograph. Possibly the dry, rectilinear imagery of Walker Evans and the wide-eyed attitudes of Diane Arbus’s portraits have contributed to the sense of stiff ceremony such shots sometimes have.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham (1936)

Asian filmmakers combined the planimetric image with very long takes. In Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Maborosi, Yumiko’s husband comes home drunk, a slip from his usual reliable habits. She has just been remembering her previous husband, dead in a bike accident. The rocklike stability of the shot, aided by the grid backing the characters, throws every gesture into relief, particularly when Yumiko’s face lifts slightly into and out of shadow in the course of the action.

In the 1990s US indie filmmakers adapted this staging strategy. In Safe, Todd Haynes uses it to suggest the hard-edged sterility of the wife’s suburban life, which surrounds her with cubical furniture.

Wes Anderson used the image schema occasionally in Bottle Rocket but came to rely on it more and more. (He tended to use wide-angle rather than longer lenses, though; note the bulging effect in the Life Aquatic shot below.)

For Anderson, as for Keaton and Kitano, the static, geometrical frame can evoke a deadpan comic quality. This comes out as well in Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite.

Initially, this scheme also helped filmmakers distinguish their work from Hollywood. Mainstream American films tend to film players in 3/4 views, except for certain situations, such as a theatrical performance or a scene showing a mammoth image display.

V for Vendetta (2005)

Some American directors seem to have used the planimetric shot decoratively, as a nifty one-off touch, as here in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

Many overseas directors who rely on this schema adjust their cutting accordingly. In Figures I called it compass-point editing. The usual tactic is to follow one planimetric shot with a reverse shot that’s also planimetric. In the first four shots of Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea, the camera angle switches either 180 degrees or zero degrees.

When I asked Kitano why he cut this way, he gestured toward me, then at himself. “When we are speaking, this is the way we look toward each other. It’s the most natural way to show a conversation.” Apparently this is why over-the-shoulder shots are pretty rare in Kitano’s films.

Planimetric shot/ reverse shot is seldom used in Hollywood films, and it seems to be reserved for certain confrontational situations, or institutional scenes (e.g., doctor/ patient conversations). It can sometimes suggest an unnerving or unnatural encounter, as in I, Robot. The detective Spooner is calling on his old friend Dr. Lanning, and their dialogue is shot in to-camera medium-shots.

At the climax of the conversation, the camera takes up a 3/4 position and arcs around Lanning, revealing him to be only a hologram, presenting his dying message to Spooner. The planimetric image is motivated as suitable for a flat, virtual presence.

Proyas has cleverly prepared us for this subterfuge by ending the previous scene with an unremarkable planimetric framing on Spooner as elevator doors close on him.

This shot leads directly to the initial shot of Dr. Lanning above, apparently addressing us, in a sort of shot/ reverse shot cut across two scenes.

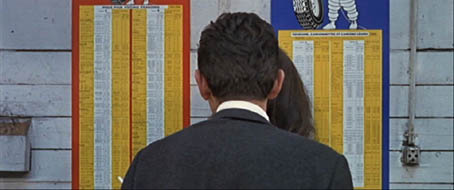

As we might expect, Godard, who helped disseminate the schema, is all up for upsetting it, in Vivre sa vie and Made in USA. The first shot below teases us to read the flat background as a high-angle vista; the second carries the idea of a conversation in a planimetric frame to a beautiful absurdity.

My quick survey doesn’t exhaust the various forms and uses of this strategy. I just wanted to show how shot-consciousness can lead us to notice when filmmakers take up new pictorial tools and modify them for particular purposes.