Archive for the 'FILM ART (the book)' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2019

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries cite Film Art, but most of them are relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Readers who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we have posted well over 900 entries, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Last year for the first time I included recommendations for potentially useful videos in our series “Observations on Film Art” (a sort of extension of this blog) on the FilmStruck streaming service. Every month Jeff Smith (also our collaborator on Film Art), David, and I had contributed a visual essay that applied concepts from Film Art: An Introduction to a film (or films) streaming on FilmStruck, which began in November of 2016 and ended in November of 2018.

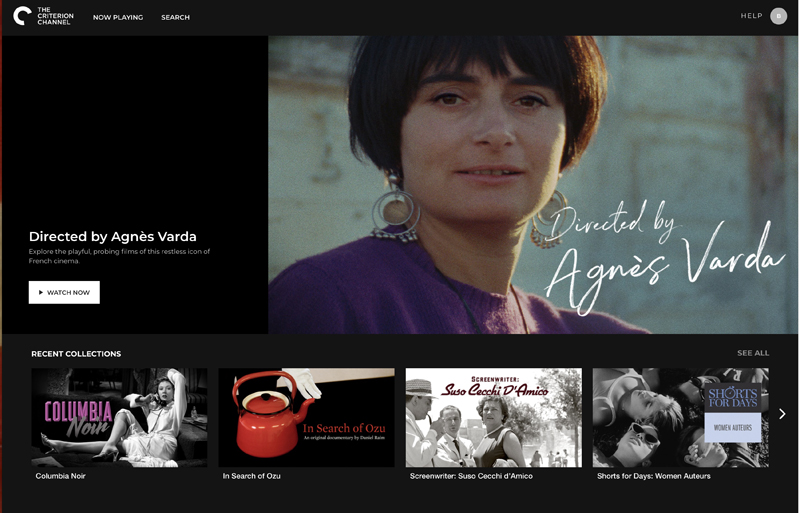

Fortunately in April, 2019, that platform was replaced by The Criterion Channel, which had been a major attraction as part of FilmStruck. The essays that we had contributed to FilmStruck have all been reposted on the new service, and we have continued to contribute monthly essays. As of now there are 29 essays online. See last year’s “Is there a blog in this class? 2018” for the earlier videos. (For information on the changeover of services, see here.)

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

I’ve written an occasional series on the progress of 3D in modern cinema. In an entry concentrating on exhibition rather than the technology or the movies, I talk about the decline in the number of 3D screenings as they lose popularity: “3D in 2019: RealDivided?”

In Chapter 1 we briefly deal with the concept of the author or auteur of a film. David provides an example of how one characterizes an auteur’s work in “Terence Davies: sunset songs.” Is Michael Curtiz as clearly an auteur as Orson Welles is? This entry considers some evidence.

No year on the blog is complete, it seems, without something on Hitchcock. This time David considered Notorious, preparing the way for a video essay for the Criterion release of this masterpiece.

At greater length, our updated e-book on Christopher Nolan is a study of him as an auteur with a “formal project.” David discusses the changes in “Christopher Nolan: Back into the Labyrinth.” A later entry considers (unconvincing) critical attacks on Nolan’s work.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

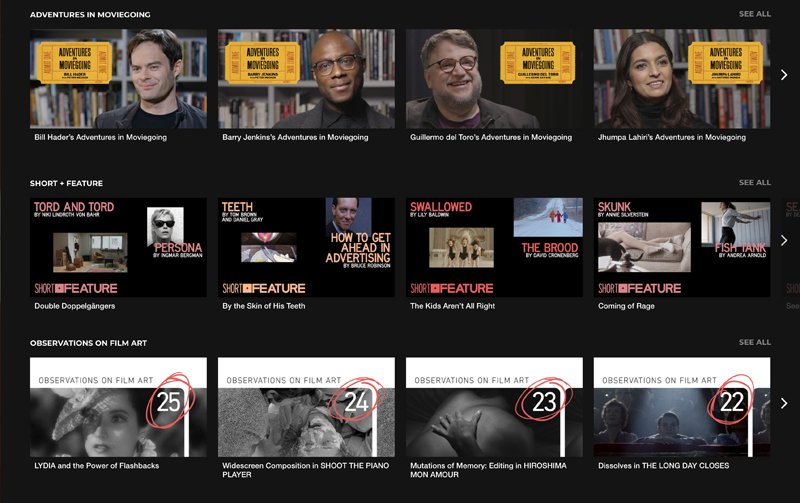

In The Criterion Channel video essay, #25, “Lydia and the power of flashbacks,” David discusses the somewhat experimental ways in which flashbacks are used in Julien Duvivier’s 1941 romance. He extends his analysis in “Lovelorn LYDIA: A new installment on The Criterion Channel.”

I analyze one aspect of narrative form in The Favourite: “Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE.”

Narrative options both old (the 1940s) and new (Happy Death Day 2U) are considered in an entry on how incidents can be repeated and varied, within a film and from film to film.

This chapter of Film Art discusses narration in terms of depth, how much of characters’ knowledge and thoughts are revealed to us. In “Observations on Film Art” #26 on The Criterion Channel, Jeff examines technique that allow us access to the protagonist’s mind in “Memories of Underdevelopment.” He expands on that analysis in “Politics and Subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on The Criterion Channel.”

Can the tools of narrative analysis shed light on The Narrative of contemporary US politics? David tries in the entry “Reliable narrators? Telling tales on Trump.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

#27 in our “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel, David examines the intricate mise-en-scene of Kenji Mizoguchi: “Games of Vision in STREET OF SHAME.” He elaborates on the blog with “How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on The Criterion Channel.”

David analyzes the staging of a scene in Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Voto (The Mask and the Face, 1919) in “Sometimes an actor’s back …” Those of you teaching Film History: An Introduction might find this entry useful in relation to the discussion of tableau staging in Chapter 2.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinemagraphy

In The Criterion Channel’s #24 in the “Observations on Film Art” series, Jeff Smith analyzes “Widescreen Composition in Shoot the Piano Player.” He offers additional commentary on the subject in a blog entry, “On The Criterion Channel: Jeff Smith on SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER.”

Chapter 6 The Relationship of Shot to Shot: Editing

In The Criterion Channel’s #23 video, “Mutations of Memory–Editing in Hiroshima Mon Amour,” David discusses the film’s complex, innovative use of editing to create flashbacks. He expands on that analysis in the blog entry, “On The Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters.”

Dissolves provide a way to join shot to shot. They’re usually used sparingly and in conventional ways (flashbacks, ellipses). In “Observations on Film Art” #22 on The Criterion Channel, “Dissolves in The Long Days Closes,” I discuss how dissolves become a prominent formal device in Terence Davies’ film.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Guest blogger Jeff Smith analyzes the music in True Stories: “From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES.”

Jeff takes an informative look at the five songs from 2018 films nominated for Oscars in “Oscar’s siren song: The return: a guest post by Jeff Smith.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes cutting and framing in one scene in the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs in “The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master-class.”

The great critic André Bazin decisively shaped our sense of how to understand film form and style. David explores some of his ideas in “André Bazin, man of the cinema” and an essay, “Lessons with Bazin.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David on film noir: “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: much ado about noir things.”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

Reporting from the Vancouver festival, David discusses two documentaries that might be useful to show if you program films by either of these directors for your class: The Eyes of Orson Welles and Bergman: A Year in the Life. See his “Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors.”

David on three documentaries shown at our hometown film festival this year, in “Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas but docus as dramas.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We were lucky enough to return to the Venice International Film Festival last year, again offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premiere of Damien Chazelle’s First Man and is based on a single viewing. The second discussed Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Mike Leigh’s Peterloo.The third offered David’s thoughts on the posthumous release version of Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind. In a fourth, I dealt with five films from the Middle East, including Amos Gitai’s A Tramway in Jerusalem. David considers variants of wrong-doing in films from around the world, including Zhang Yimou’s Shadow and Erroll Morris’ American Dharma. Sixth and last was my longer analysis of László Nemes’s brilliant but challenging second feature, Sunset. We plan to carry on this tradition of comments on new films when we attend the Venice International Film Festival next month.

Our annual visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival yielded more brief analyses of new films. In “Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined,” David looks at some recent Asian films, including Kore-edge Hirozaku’s Shoplifters. In “Vancouver 2018: A panorama of the rest of the world,” I comment on three films by important international directors: Nuri Bilge Ceylon’s Turkish The Wild Pear Tree, Benedikt Erlingsson’s Icelandic Woman at War, and Pavel Pavlikowski’s Polish Cold War.

I followed up with more international films in “Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the rest of the world, the sequel“: Matteo Garrone’s Italian Dogman, Nina Paley’s American Sedar-Masochism, Wolfgang Fischer’s Austrian Styx, and Christian Petzold’s German Transit. David wrote about crime films (and a TV show) in “Vancouver 2018: Crime waves.” These notably included Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Our wrap-up, “Vancouver 2018: A few final films,” again had an international flavor, commenting on Jafar Panahi’s Iranian 3 Faces (his defiant fourth feature since the government banned him from filmmaking for twenty years), Nadine Labaki’s Lebanese Capernaum, and Ciro Guerra and Cristina Gallego’s Colombian Birds of Passage.

Looking back on these two festivals makes it clear that 2018 was an extraordinary year for the cinema!

David analyzes True Stories on the occasion of its release on Blu-ray: “Pockets of Utopia: TRUE STORIES.”

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

Teaching film history? My annual choice of the ten best films from 90 years ago offers some familiar and not-so-familiar titles: “The ten best films of … 1928.” I also consider two releases of major German silent films.

Many of our entries from Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna consider older films, especially those from 1919 in “German and Scandinavian classics.” I discuss some major African films in “Who put the pan in Pan-African cinema?”

I discussed a Blu-ray release of two rare films by Mary Pickford in “Pickford times two.”

A more recent trend in film history, that of the improvised independent American film, is considered in our review of J. J. Murphy’s book Rewriting Indie Cinema.

Finally, for Film Art: An Introduction users, an account of how Jeff Smith, David, and I revised our textbook for its twelfth edition.

After forty years, we’re still grateful to teachers and students who have found Film Art: An Introduction useful in their study of cinema.

Frisky at forty: FILM ART, 12th edition

DB here:

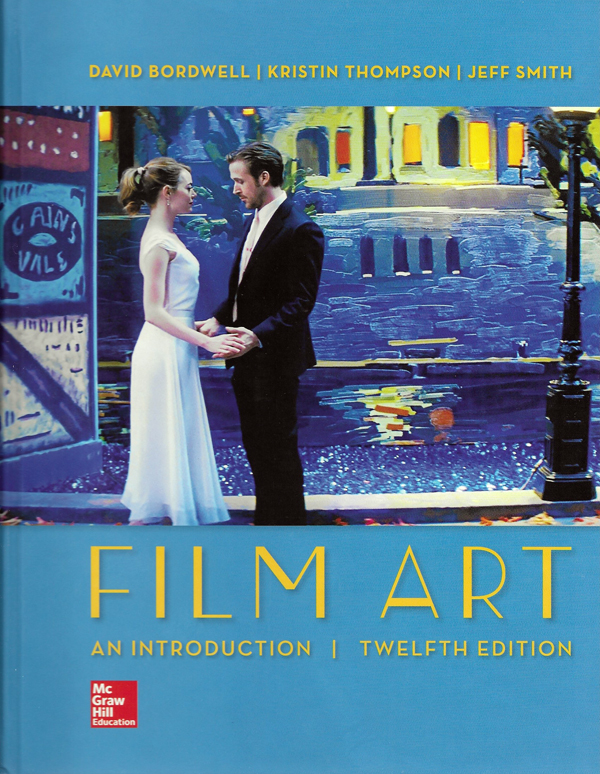

The first edition of Film Art: An Introduction rolled into an unsuspecting world in 1979. Its butterscotch jacket enclosed 339 pages of text and black-and-white illustrations. It was, I think, the first film studies textbook to use frame enlargements instead of production stills. It was definitely the first to argue for a systematic aesthetic of cinema integrating principles of form (narrative/nonnarrative) with style (techniques of the medium). Our goal, of course, was to enhance the readers’ appreciation of the range and power of film as an art form.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

The core of our efforts remain the ideas and information we explore in the text. That material, happy to say, has found support among teachers, scholars, and writers of other textbooks. Through their suggestions and criticisms, we’ve had four decades to refine what Kristin and I initially set out, and on the eleventh edition Jeff Smith joined us to make things even better.

What’s new about this twelfth edition? Of course, we’ve updated it. We incorporate examples from Get Out, Son of Saul, mother!, Moonlight, Guardians of the Galaxy, Tiny Furniture, Inside Man, Wonderstruck, Dunkirk, Fences, Manchester by the Sea, Baby Driver, The Big Sick, Hell or High Water, Hostiles, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Blind Side, Opéra Mouffe, My Life as a Zucchini, Kubo and the Two Strings, Lady Bird, Birdman, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Tangerine, A Ghost Story, Snowpiercer, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and other recent titles.

One of the biggest changes involves the addition of an analysis of social and political ideology in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. This detailed look at Fassbinder’s melodrama of prejudice replaces our study of masculinity and violence in Raging Bull. That earlier piece will be posted for free access on this site, joining analyses from earlier editions on this page.

The most evident difference, signaled on the cover you see above, is a new case study of how a film gets made.

Production: The hows and whys

The book’s opening chapter,”Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business,” matters a lot to us. We try to provide concrete, systematically organized information about how people work with technology and within institutions to implement the techniques we’ll survey in later chapters. At the same time, our discussion of production, distribution, and exhibition tries to show how filmmaking institutions shape creative choices about form and style. Perhaps because we try to make those choices down-to-earth, we’ve been pleased to find that Film Art is used in film production courses.

For several editions, Michael Mann’s Collateral served us well as a model of how decision-making in the production process shaped the final film. We thought, however, it was time to refresh that chapter, and La La Land provided us rich opportunities. We had already written blog entries (here and here) about aspects of the film, but we wanted learn more about how it had been created.

Made by a director not much older than our students, La La Land was perfect for a book that tries to be both up-to-date and sensitive to film history. From the burst of ensemble energy in the opening traffic jam to the parallel-reality ballet at the end, Damien Chazelle’s film was both contemporary and classical, what Kristin calls “a modern, old-fashioned musical.” We thought it would help students see that a young filmmaker can draw on tradition while staying firmly in our moment.

The film’s production decisions were well-documented, so we were able to trace four areas of creative choice. By considering the film’s mise-en-scene, camerawork, editing, and sound, we could set up the major stylistic categories to come in later chapters. For example, Jeff could point out unique features of Justin Hurwitz’s score.

We were lucky to get guidance from Damien himself. He reviewed our analysis, and then went far beyond the call of duty. He came to Madison to talk with our students (chronicled here). He sat for interviews with the Criterion Channel on Jean Rouch and Maurice Pialat. He did three Q & A’s. He even took snapshots with his fans.

And Damien energetically helped us secure rights to the cover image, a process that all writers of film books approach with fear and trembling. In short, he proved a total mensch. The fact that he had already read our work when we first contacted him encouraged us in the belief that we might be helping young filmmakers find their way.

Film Art wherever you go

Film Art is now available in a variety of formats and prices. The print edition is now a looseleaf, unbound one. Bound copies still circulate for rental. Students may also rent or buy the e-book edition, which comes packaged as a digital resource called Connect. It’s possible to merge some of these alternatives. The various options for getting the book are charted here.

The Connect package includes teaching aids for the instructor (self-tests, quizzes) and access to thirty-six film extracts, courtesy of the Criterion and Janus companies. There are also four fine videos on production practice by our colleague Erik Gunneson.

As I discussed at exhausting length when I previewed our new edition of Film History: An Introduction, the variety of formats for the book reflects not only changes in technology and the publishing market but also changes in consumer preferences.

However it’s accessed, Film Art: An Introduction still makes us happy. We’ve tried our hardest to help readers understand a bit more about the techniques and effects of cinema. As we point out in the book, thanks to smartphones everybody is a filmmaker now. We think that students’ hands-on experience prepares them for our efforts to understand the creative choices filmmakers have faced from the very beginning.

Thanks as ever to the staff at McGraw-Hill: our editor Sarah Remington and the team consisting of Danielle Clement, Sue Culbertson, Maryellen Curley, Joni Fraser, Ann Marie Jannett, and Elizabeth Murphy. Thanks as well to Kaitlin Fyfe and Erik Gunneson here at the Department of Communication Arts, UW–Madison. And of course thanks to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, and their colleagues at Criterion.

Instructors who want to learn more about this edition can find a McGraw-Hill representative here.

Jeff Smith, who wrote the analysis of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul for our book, also provided an incisive discussion of staging in the film for our series on the Criterion Channel.

There’s a fuller account of how we came to write Film Art in our announcement of the previous edition.

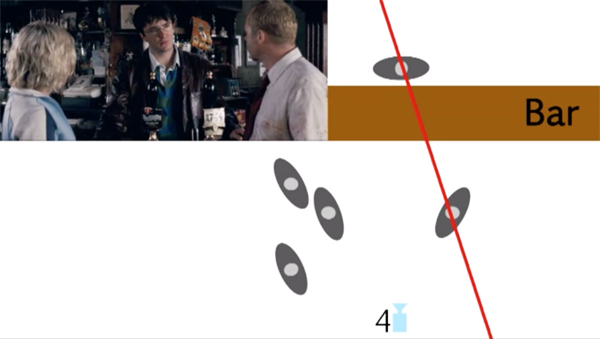

Video supplement: Shifting the Axis of Action in Shaun of the Dead.

The Criterion Channel: The best news for film culture you will hear today (and probably all year)

DB here:

The Criterion Channel is up and streaming in the US and Canada as of today. You can browse the offerings here. Some basic questions are answered here. For help activating your account, try here.

Using Apple TV, I found it very easy to get access. I was immediately and flawlessly playing The Big Heat, Taipei Story, La Pointe Courte, and Le Amiche, that unjustly ignored Antonioni masterpiece.

For background and news on forthcoming options, check out this interview with Peter Becker. For those who miss the Hollywood side of FilmStruck, the Channel will be streaming studio-era classics as well as silent, foreign-language, and independent titles.

And all the extra features from FilmStruck–Adventures in Moviegoing, Ten Minutes or Less, Split Screen, Short + Feature, plus the supplements and interviews and bonus felicities you’ve come to expect from Criterion–will continue and accumulate in an archive. The menu includes our Observations on Film Art series, re-launching this month with me talking about flashbacks in Lydia. (It was up briefly in the waning days of FilmStruck. There’s a blog entry about it too.)

At some point, a vast array items from the Criterion/Janus library will be accessible as well. That’s the iceberg underneath the surface. How many films? Wait and see, and be astonished.

This is truly a momentous event in our film culture. We want to thank the Criterion team, all of them devoted film lovers, for working so hard to make this ever-expanding treasure-house available.

Under our Criterion Channel category, you can find all the blog entries devoted to our installments there, including those from the FilmStruck days.

Is there a blog in this class? 2017

Kristin here–

As each fall semester looms, we provide you with a rundown of entries on our blog that might be useful to teachers and students. They also can be handy for other readers who want to check whether they have missed some entries that might interest them.

We started this blog nearly eleven years ago partly with the idea of providing supplementary material that might be of use to teachers who assign our Film Art: An Introduction textbook. But we don’t make any attempt to tie our entries to the textbook. Each year, however, we naturally deal with film techniques, formal strategies, stylistic choices, norms and transformations of them, and genre conventions, and some of these could be useful in teaching or preparing lectures for specific chapters of Film Art.

We haven’t listed every post, but you can find more by using the very efficient search engine or the many categories listed on the right-hand side. You can also see previous entries in this series here: 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

Multiple chapters

“DUNKIRK Part 1: Straight to the good stuff” and “DUNKIRK Part 2: The art film as event movie.” These two entries discuss aspects of Christopher Nolan’s film. The first talks about Dunkirk’s minimal exposition, which would be relevant to Chapter 3 (Narrative Form), and the color scheme, which would relate to chapters 4 and 5, on Mise-en-Scene and Cinematography. The second part deals with its genre, as a mixture of the war film and thriller (Chapter 9); it also looks at the film’s temporal scrambling, which relates to Chapters 3 and 6 (Editing).

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

“Replay it again, Clint: Sully and the simulations” considers some ways of creating complex story-plot relationships, particularly through flashbacks that replayt events. It concentrates on recent Clint Eastwood films and especially Sully.

In “ARRIVAL: When is now?” David looks at that rare phenomenon, the flashforward. He concentrates on Denis Villeneuve’s science-fiction film and its challenges to the viewer.

We have a sneaking suspicion that many teachers will be teaching La La Land. It would work as an accompaniment to several of our chapters in Film Art (narrative, sound, genre, etc.). We’ve blogged about it three times this year. In “How LA LA LAND is made,” we analyze the narrative structure and how the songs fit into it (as well as following the classic template of the Broadway musical).

“Fantasy, flashbacks, and what-ifs: 2016 pays off the past” offers a study of depth of narration, particularly in films where our knowledge of the action is largely restricted to that of a single character’s. In some cases there is presentation of the character’s subjective thoughts and memories. Lots of recent films furnish examples.

“Anybody but Griffith.” This post also deals with staging, but specifically with a type of staging, often quite elaborate, that was used largely in the period from 1908 to 1920. It depended on sustained takes rather than editing and on the actors’ precise gestures and shiftings of position. David has written quite a lot about it as the “tableau” style. Useful for advanced students or if you’re teaching or studying silent cinema.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

“My girl Friday, and his, and yours” is about His Girl Friday. The first section examines the historical sources of the title phrase, while the second part deals at some length with subtleties of staging, both in depth and across the frame.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

“Wisconsin Film Festival: Sometimes a camera movement …” offers a close study of a single long-take 360-degree panning movement in Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion.

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

“Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel” examines the “axial cut.” It’s an editing technique that cuts closer and closer to (or, rarely, further away from) its subject straight along the axis of the lens, without a change of angle. It may sound obscure, but it’s actually commoner than you might think. Even The Simpsons uses it occasionally.

“Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it” examines crosscutting in some recent films.

“Camera connections: RED on FilmStruck: A guest post by Jeff Smith” looks at cinematographic style in Krszystof Kieslowski’s Three Colors: Red.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

“Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT” analyzes how the musical score of Hitchcock’s film fits into the film’s narrative progression.

“Oscar’s Siren song 3: a guest post by Jeff Smith” examines the wide variety of approaches used in the musical scores of the 2016 Oscar nominees for best score.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

“Going inside by staying outside: L’AVVENTURA on the Criterion Channel” examines stylistic changes in Michelangelo Antonioni’s films, particularly relating to staging.

Chapter 9 Film Genres

“LA LA LAND: singin’ in the sun” has three guest experts on musicals discussing the conventions and innovations of La La Land.

For those who teach film noir (and quite a few of you do) might want to look at “Film noir, a hundred years ago.” It gives numerous examples of “film noir” lighting in films of the 1910s. This could also be used for low-key lighting in Chapter 4.

“Thrill me!” discusses the recent prevalence of the thriller movie, even among art-cinema directors.

“MONSIEUR VERDOUX: lethal lothario” treats Chaplin’s film as belonging to the serial-killer genre.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

“Murnau before NOSFERATU” could be useful in teaching the silent-German section of this chapter or if you show any early Murnau film. There’s nothing on Expressionism but quite a few examples from major German films of the late 1910s and early 1920s, primarily the restored Der Gang in der Nacht (1921).

“The ten best films of … 1926” is the latest in our annual attempt to call attention to the classics of the silent era, both famous and obscure. This year’s list covers several countries’ films, including Japan for the first time.

Miscellaneous

If you supervise dissertations or are writing a book yourself, you might be interested in seeing how David went about researching his forthcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood. Complete with exciting photos of boxes of file folders. See his “Oof! Out!”

Every now and then we post a wrap-up of recent DVDs and Blu-rays. “Silents nights: Stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings, the sequel” concentrates on two releases, one a beautiful restoration of a well-known classic and one a rediscovery of a Native-American feature.

“OBSERVATIONS goes all FILMSTRUCK.” For those of you using the rich foreign and indie offerings of streaming service FilmStruck for teaching, class preparation, or personal pleasure, we have an introduction to our contribution to the supplements thereon. Our series of introductions to films, “Observations on Film Art” is, as its name suggests, a sort of extension of this blog. We do close analysis of a specific topic in one or two films, complete with more clips than we could possibly use in our entries here.

Finally, if readers, teachers, and students are curious about how Film Art came to be written, that comes up in our SCMS interview with Charlie Keil, linked in this blog entry.

Arrival