Archive for the 'FILM ART (the book)' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2015

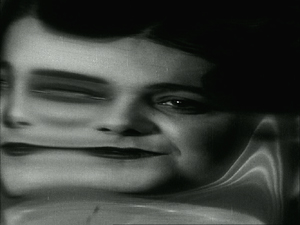

Michael (Carl Dreyer, 1924)

Kristin here:

We don’t write our entries for this blog with with the thought that they will necessarily be used in teaching. Still, some of them might be might prove helpful in preparing lectures or assigning readings in courses assigning Film Art: An Introduction. Or indeed, other courses. As usual, at a time of year when teachers are preparing their syllabi, we offer a run-down on what we’ve posted over the past year.

Entries for previous years are available here: 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. These and the current one don’t include all the 701 (!) entries on this blog, but quite a few are listed here. For those new to Observations on Film Art, they might provide a handy way of exploring the site.

Here are some suggestions, chapter by chapter. Sometimes one entry will be relevant to several chapters, so we’ve noted such overlaps.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

At the end of Chapter 1, we have long included a section warning students against watching widescreen films shown on television in pan-and-scan formats. Widescreen televisions, as well as letterboxing and windowboxing on home video, may seem to have solved that problem. Yet alterations in film images, often eliminating key parts of shots, persist. We discuss how in Filling the box: The Never-Ending Pan & Scan Story.

Throughout Film Art, we emphasize that filmmaking involves many decisions and much problem-solving. We examine some specific examples from the works of William Wyler and others, in Problems, problems: Wyler’s workaround.

Chapter 1 discusses the various roles in filmmaking. An important contemporary screenwriter, David Koepp (Jurassic Park, The Da Vinci Code, War of the Worlds) and director (Ghost Town, Premium Rush) visited our department this year. We pass along some of what we learned in The compleat screenwriter: David Koepp gives notes.

Bill Forsyth, director of the admirable Local Hero, shares his experiences working on both experimental and mainstream films in Watch those hands.

We also refer to the auteur theory, suggesting that the director is often the major artist who organizes a film. François Truffaut’s book of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock has been a huge factor in making Hollywood genre directors more respected. It has also influenced many directors and critics. Our friend Kent Jones has made a revealing film about the background of the interviews and the books. We discuss both the book and Kent’s film in TRUFFAUT/HITCHCOCK, HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT, and the big reveal.

Chapter 2 The Significance of Film Form

Here we lay out the various types of meaning in films, including symptomatic meaning. Looking at how films supposedly reflect social trends, however, has become an easy way of generating journalistic prose. We point out the problems with this approach in Zip, zero, Zeitgeist.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

Chimes at Midnight.

Michael Neelsen, a filmmaker and consultant based here in Madison. has a site called ReelFanatics. In our entry Cinematic storytelling: A podcast on narrative, we preview Michael’s interview with David about his ideas on filmic storytelling.

The narrative of Gone Girl plays with the spectator’s expectations. We discuss how it links to Hollywood’s historical treatment of the thriller genre in Gone Grrrl.

Chapter 3 has a “Closer Look” box, “Playing Games with Story Time,” which examines the recent popularity of “what if” films that employ forking-path premises. We discuss a much earlier example of this technique from 1934 in What-if movies: Forking paths in the drawing-room.

Another intriguing way of structuring stories is the “network-narrative” technique, which weaves together the lives of several seemingly unconnected characters. As a storytelling choice it persists in films like The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. The format was popularized in the 1930s with the “Grand Hotel” cycle of films. We survey this narrative option in 1932: MGM invents the future (Part 2). For Part 1, see below under Chapter 7.

If you’re teaching Citizen Kane or any other film by Orson Welles (right, very young), your students might be interested in learning some background on the director. See our Local Boy Makes Very, Very Good: Welles comes home.

If you’re teaching Citizen Kane or any other film by Orson Welles (right, very young), your students might be interested in learning some background on the director. See our Local Boy Makes Very, Very Good: Welles comes home.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

The Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien is a great master of staging, setting, and lighting. Hou Hsiao-hsien: A new video lecture! links you to a presentation that David posted on Vimeo. See also our guest entry, Jim Udden’s first impressions of Hou’s latest, The Assassin.

In 2014, Richard Linklater’s Boyhood focused much attention on acting and casting by dealing with twelve years in a boy’s life. The shooting was done across twelve years using the same actor as he grew up. Despite the acclaim for the film, something similar has been done in other films. We compare the effects of actors growing up before our eyes with a comparison to the Harry Potter series in Harry Potter and the Twelve-Year Boyhood.

Like other aspects of mise-en-scene, actors’ performances can be analyzed. Watch Those Hands considers Burt Lancaster’s performance style in The Killers, Brute Force, and other film noir classics. Two clips illustrate Burt’s control of eyes and hands.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Some students may be convinced that CGI (computer-generated imagery) is the best way to make a big action movie. We look at Mad Max: Fury Road (above) and The Lord of the Rings as films that are more original and entertaining because they emphasize practical effects and resort to CGI only when necessary. See The waning thrills of CGI.

Jean-Luc Godard’s late films offer fascinating examples of unusual framings. Sometimes his camera positions block our easy understanding of the story action. We consider an example in Watch those hands.

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot

In BIRDMAN: Following Riggan’s Orders, we argue that although much of the film is presented as a single shot, we can see changes of camera angle and distance that fit the patterns of traditional editing. The film in effect absorbs the principles of continuity editing into its long-take approach.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

The origins of cinematic voice-over in the 1930s can be traced with surprising precision, as we indicate in 1932: MGM invents the future (Part 1). The entry includes several video clips from rare films of the period.

Guest blogger Jeff Smith applies his expertise in music to analyzing the songs and scores from 2014 nominated for Oscars in The sirens’ song for Oscar.

Film Art occasionally uses telephone calls to show the range of choices filmmakers have with respect to sound. In Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics, phone calls illustrate the interplay of editing, dialogue, and music to build suspense. Our biggest example, which includes a video clip, comes from Humoresque (below).

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Current 3D cinemag has become quite ambitious, and no film exemplifies this better than the provocative, sometimes abrasive, often beautiful Adieu au langage (Goodbye to Language) of Jean-Luc Godard. We devoted two entries on this extraordinary film. Adieu au langage: 2 + 2 x 3D analyzes the relation between the film’s 3D design and its overall form. The other, Say hello to Goodbye to Language, proposes some follow-up ideas.

Film Art tends to use fairly straightforward examples of film technique and style, aimed at students new to the subject. But less noticeable examples can be fascinating, as we suggest in the Micro-stylistics entry.

Film is self-evidently a primarily visual art. Yet the flow of images depends on sound, genre conventions, and other elements. See our Visual storytelling: Is that all?

Chapter 9 Film Genres

Gone Grrrl, as mentioned above, is a good example of the thriller. The Hitchcock/Truffaut entry compares how each director uses conventions of the same genre.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

The conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image was the occasion for meeting experimental filmmakers John Smith. His films are described in An evening with Mr. Smith.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

Our entry on Birdman, mentioned above, constitutes a fairly detailed analysis of the film as a whole. In addition, David’s website hosts several additional analyses cut from earlier editions of Film Art. Feel free to mix and match.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

The Last Laugh.

At the end of each year, we offer our own version of a ten-best list, going back 90 years in order to call attention to both classics and little-known gems of the day. This past year it was The ten best films of … 1924. (See directly above and top of this entry for two of our choices.)

Both Michael and The Last Laugh are among the many classics of the German silent cinema. But a trip to an archive can reveal lesser-known films of interest. See Homunculus and his friends for some examples.

Resources

Every now and then we write about new book, DVD, and Blu-ray releases. Find out about little-known films and recent restorations in DVDs and Blu-rays for your letter to Santa.

Our colleague Lea Jacobs has recently published a major study of how the ways in which music, voice, and effects created rhythm in combination with images in the first decades of sound cinema: Film Rhythm after Sound: Technology, Music, and Performance. See The getting of rhythm: Room at the bottom.

Adieu au langage.

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

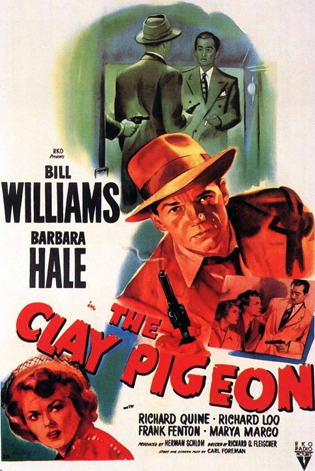

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).

Is there a blog in this class? 2014

Kristin here:

Once again the fall semester approaches, and educators are pondering their film-class syllabi. As always, we have prepared a guide to our blog entries from the past year, with suggestions about how some of them might usefully be assigned alongside chapters of Film Art: An Introduction. Readers who aren’t teaching could use this guide to alert them to entries they may have missed.

For the entries from past years, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013.

David is at work on a book on 1940s Hollywood cinema, which he finds a strange and innovative era. Several of his entries for this past year reflect that focus.

Chapter by chapter

Chapter 1: Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Last year several of our entries dealt with the conversion of exhibition from film to digital copies. That conversion has progressed until 35mm houses are now relatively rare. We take a look at a theater still showing movies on film in “Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.”

Chapter 3: Narrative Form

Sometimes producers force scriptwriters to change their scripts. These changes aren’t always bad. They can lead filmmakers to find ingenious solutions that actually enhance the result. We look at some examples from the 1940s in “Innovation by accident.” (As in Kitty Foyle, above.)

Two professors have already told me they were going to teach Gravity this coming semester, assigning our two entries on the film. These could be used for a variety of chapters: the first one, “GRAVITY, Part 1: Two characters adrift in an experimental film” is on the narrative of the film and could most obviously assist in teaching Chapter 3. It might also be a helpful reference, however, for Chapter 10, in discussing the boundaries between experimental and mainstream cinema.

The differences between suspense and surprise is a common topic in discussing narratives. We look at Hitchcock’s famous distinction between them and where he got it in “Hitchcock, Lessing, and the bomb under the table” and “Hitchcock Again: 3.9 Steps to Suspense.”

For advanced students, you might consider assigning an essay David has posted on his website proper, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” He elaborates on this essay with examples from Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street in “Understanding film narrative: The trailer.”

Modernism involves playing with plots, sometimes in challenging ways. In another entry for advanced students, we examine such playfulness: “Pulverizing plots: Into the woods with Sondheim, Shklovsky, and David O. Russell.”

During the 1940s, filmmakers sometimes explicitly broke their films down into chapters. That tradition has not disappeared–especially in the films of Quentin Tarantino. We explore some connections in “The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks.”

Chapter 4: The Shot: Mise-en-scene

Staging is an important aspect of acting. We give some historical notes about how characters have been set up to face each other in a two-shot composition in “Where did the two-shot go? Here.”

Few directors combine staging, setting, composition and acting as brilliantly as Kenji Mizoguchi. We explore his extraordinary mise-en-scene in “Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image.” (Above)

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

In anticipation of Gravity‘s release, we wrote about long takes in Alfonso Cuarón’s earlier films and in particular Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in “Harry Potter treated with gravity.”

Our second entry on Gravity, “GRAVITY, Part 2: Thinking inside the Box,” could be taught in connection with the entry on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in discussing long takes. It also, however, exemplifies cutting-edge techniques in digital cinematography, special effects, and 3D.

Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel wonderfully exemplifies variations on aspect ratios. Its style is also based on framing perpendicularly to the backs of sets (earlier explored in “Shot-consciousness”). See “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL: West Anderson takes the 4:3 challenge.” (Above)

Chapter 6: The Relation of Shot to Shot: “Editing”

At the Vancouver International Film Festival, we caught Walter Murch’s lecture on the industry’s transition to digital editing. Here’s our write-up: “Film-industry pros share secrets in Vancouver.”

Our two Wes Anderson blogs (here and here) discuss his customized variant of classical continuity editing.

Chapter 8: Summary: Style as a Formal System

Nebraska

Teaching about auteurism and style? Kristin met Alexander Payne last year at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Then he came and visited Madison this past spring. We blogged about that visit and his films in “Alexander Payne’s vividly shot reality.” He was still talking to us at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year, so he must have liked the entry!

Chapter 10: Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

We wrote an entry on a major recent documentary film, “I am a camera, sometimes: Tim’s Vermeer.” Also quite teachable.

Chapter 11: Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

If you show Tokyo Story, or any other Ozu film, your students might be interested in Ozu’s influence up to the present day. Our entry “Look well! Look again! Look! (For Ozu)” explores this subject.

Apart from the entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel linked above, we’ve written an analysis of his previous film in “Moonrise Kingdom: Wes in Wonderland.” His recent films, starting with Fantastic Mr. Fox, strike us as very teachable.

David has written several entries on some major American critics of the 1930s and 1940s–Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Parker Tyler, and Manny Farber–and their approaches to analysis and evaluation. These would be suitable for students interested in writing film criticism themselves.

“Otis Ferguson and the Way of the Camera”

“The Rhapsodes: Agee, Farber, Tyler, and Us”

“Agee & Co.: A Newer Criticism”

“James Agee: All there and primed to go off”

“Manner Farber 1: Color commentary”

“Parker Tyler: A suave and wary guest”

and finally “The Rhapsodes: Afterlives”

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

If you are looking for silent films to show as illustrations of German Expressionism, French Impressionism, silent classical Hollywood, or very early experimental cinema, try the latest entry in our surprisingly popular annual summary, “The ten best films of …1923.” Not all the films are available on DVD at this point, but the ones that are are well worth seeking out.

Examples of early film and the transition to more classical storytelling can be found in our summer entry, “What’s Left to Discover Today? Plenty.”

An update to the Hong Kong section of the chapter can be found in our entry on Wong Kar-wai’s latest film: “THE GRANDMASTER: Moving forward, turning back.”

Further resources

For information on some recent DVD and Blu-ray releases, see “Recovered, discovered, and restored DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book.”

We’ve put up an ebook on Christopher Nolan, based on updated versions of our blog entries, for $1.99. It includes some brief extracts from Nolan films, though you can opt for a version without the clips. For a description, see “Our new e-book on Christopher Nolan!

Don’t forget that we also have videos available for you to show or assign. For Chapter 3, on narrative, there’s “Twice Told Tales: Mildred Pierce,” including an imbedded Vimeo comparison of scenes repeating a crucial action. Chapter 6’s discussion of editing is supplemented by our most popular video, “Constructive Editing: Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959).”

For the history chapter (Chapter 12), there are two video lectures: an entry on “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies 1908-1920” and one on “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” (which could also be used in connection with the Cinematography chapter).

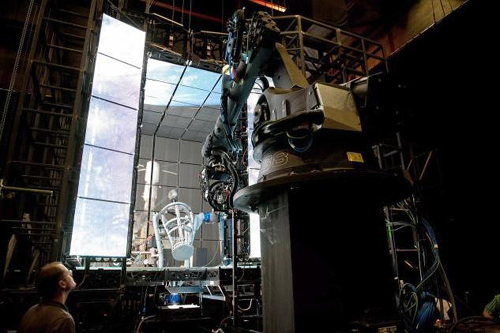

Gravity, production photograph

Is there a blog in this class? 2013

Rebel without a Cause (1955).

KT here:

It’s time for our annual scan of the past year’s entries, pointing particularly to ones that might be useful to teachers and students using Film Art: An Introduction. For occasional readers of the blog, this post might be useful in catching up on items you might have missed.

This year we’ve added four video essays and lectures to our site. These have entailed a lot of effort, but David has enjoyed making them as free complements to the briefer, walled-garden video essays accompanying our latest edition of Film Art.

We’re also delighted to include some entries based around encounters we have had with filmmakers (some of whom we met as a result of our blog) and two contributions from guest experts. Looking back, we are as usual surprised at how much material has accumulated in one year. The summer’s new movies may on the whole have disappointed, but obviously there are a lot of other interesting topics to explore outside the multiplex.

For earlier blog-roundups, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012.

I’ll go through Film Art chapter by chapter, suggesting relevant entries for each, and end with a couple of entries on new DVDs that teachers might want to add to their personal or departmental libraries.

Chapter 1 Film Art and Filmmaking

Last year, David’s “Pandora’s Digital Box” series dealt with the transition from film-based to digital-based production and distribution. (That series was revised and expanded into a book.) The original series is updated in “Pandora’s Digital Box: End times.”

This year, David looked back on some historical formats. In “The wayward charms of Cinerama,” he reviewed Flicker Alley’s DVD release of This is Cinerama and took the occasion to analyze the peculiar perspective relations created by the triple-camera system. How the West Was Won and The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm receive some stylistic scrutiny.

Super 16mm is still a significant gauge for independent filmmaking, but regular 16mm as has largely been replaced by DVD and Blu-ray for classroom and film-buff viewing. David waxes nostalgic concerning the charms of 16mm and its importance in our own film-watching careers in “Sweet 16” and “16, still super.” For those too young to have seen 16mm on a screen, these recollections might make it a bit more vivid.

Nothing conveys the tangible work of film production like a visit to a working set. Our colleague James Udden, expert on Taiwanese cinema, had an opportunity to watch a major contemporary director in action and reports for us in “Master shots: On the set of Hou Hsiaeo-hsien’s THE ASSASSIN.”

Publicity is a big part of the distribution of a modern blockbuster. In “Jack and the Bean-counters,” I examine the missteps in the campaign for Jack the Giant-Slayer and talk about how the studios avoid cooperating with fans eager to provide valuable free online publicity for their favorite films.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

Films often use repetition in an obvious way to help us easily follow a story. But what about filmmakers who introduce more subtle similarities that challenge our memories? We examine two such films made in South Korea, In Another Country and Romance Joe, in “Memories are unmade by this.”

Repetition is also central to Mildred Pierce, where a murder that happens at the beginning of the film is seen again, with different shots and timings, near the end. We look at how the film fools us without our noticing it. The sequences are here:

“Twice-told tales: MILDRED PIERCE” analyzes the different functions and effects of the two sequences.

Art films and classics are not the only films with intriguing storytelling. “Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone” is an analysis of David Koepp’s Premium Rush as a short film that packs a lot of action and clever narrative tactics into its running time. That entry led to a meeting with Koepp and a follow-up entry on his approach as screenwriter and director. See the Chapter 8 section.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Seeing some recent Asian films at the 2012 Vancouver International Film Festival led to “Stretching the shot,” some thoughts on functions for the long take.

A lot of the films we see in theaters today are made in anamorphic widescreen processes, and by now letterboxing for home-video is familiar to all. David has often lectured on the history and aesthetics of the first successful anamorphic process, CinemaScope. Now that PowerPoint lecture is available on his Vimeo site. See “Scoping things out: A new video lecture” for an introduction and link. (It’s about 53 minutes long, so perhaps something to assign your students to watch on their own.)

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to shot: Editing

“News! A video essay on constructive editing” introduces the additionof an analysis of editing in Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket to Vimeo. It’s about 12 minutes long, suitable for classroom use or assignment for students to watch outside of class. Our thanks to our friends at the Criterion Collection for their permission to use the excerpts from Pickpocket.

How much can a single cut reveal about the power of editing? “Sometimes two shots …” takes a close look at a brief passage from August Blom’s The Mormon’s Victim, a 1911 Danish one-reel film and finds a lot going on in it.

Some students might have trouble recognizing jump cuts. “Sometimes a jump cut …” looks at some examples from the martial-arts action scenes from two of King Hu’s masterpieces, A Touch of Zen and Dragon Gate Inn. These are quite different in look and function from the Breathless examples given in Film Art–and you can clearly see the splices.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Faced with innovations in sound technology, we turned to our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. His “Atmos all around” is an excellent introduction to the new system. Unlike most surveys of technology, his piece analyzes in considerable detail how artists use it–here, in Pixar’s Brave.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Alfred Hitchcock is undoubtedly one of the most frequently taught filmmakers, since his work is not only stylistically elegant, but it’s easy for students to pick up on. One reason for this is that he is fond of flashy set pieces, scenes that are skillfully composed to be the high points of a film. We examine his skill in this regard in “Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH.”

On the other hand, Hitchcock is equally good at subtle touches. Some might consider his 3-D film, Dial M for Murder, to be a bit theatrical, since much of its action is confined to a single set. Yet as we argue in “DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room,” the director finds many small, creative ways to frame and edit his shots in ways that are purely cinematic.

As we emphasize in Film Art, filmmaking is based on a huge number of creative decisions. During this past year, encounters with two practitioners gave us a chance to learn how they went about making some of these choices. Tim Hunter, director of River’s Edge (1987) and numerous episodes of television series like Twin Peaks and Breaking Bad, visited Madison. “Auteurist on the sound stage” discusses how Hunter plans ahead where he will place his camera, since the fast pace of television production allows little time for such decisions on the set. He also talks about tailoring his style to that of the specific television series he is working on.

In June David visited screenwriter and director David Koepp in his New York office. Koepp is best known for his work with Steven Spielberg, including the scripts for Jurassic Park and War of the Worlds, but he has also directed films. “David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized” discusses how Koepp finds the “Gizmo,” or basic premise, for big blockbusters and how he compresses the plots of best-sellers for the screen. He also talks about narrowing down the many choices available to a filmmaker, creating constraints that will allow him to find the best choices for a given situation–with camera placement again being a basic consideration.

This past year two major contemporary directors died: Tony Scott, director of flashy, violent Hollywood action films, and Theo Angelopoulos, maker of austere, stately dramas about Greek history and politics. We find some surprising stylistic parallels between their work, despite their obvious differences, in “Tony and Theo.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

Since The Blair Witch Project appeared in 1999, there has developed a sub-genre of horror films masquerading as found-footage documentaries. “Return to Paranormalcy” focuses on the successful series of films that began in 2007 with Paranormal Activity and explores how each successive film has managed to vary the point-of-view conventions in order to maintain audience interest.

This chapter of Film Art contains a “Closer Look” box examining “Creative Decisions in a Contemporary Genre: The Crime Thriller as Subgenre.” Our entry “SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past” looks at two more recent examples of this genre, focusing on how their conventions revive and vary conventions that had been introduced in 1940s Hollywood films in this same genre. Here’s a good example of genre conventions coming and going in cycles.

For most people, the name “Kurosawa” conjures up only the venerated Akira Kurosawa, director of classics like Seven Samurai and Red Beard. But there is a younger Kurosawa, Kiyoshi, a contemporary filmmaker. While in Brussels in July, David had a chance to attend a screening of his Shokuzai. In “The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI,” David puts Kiyoshi Kurosawa in his historical context and analyzes the film as a combination horror film and crime thriller, as well as including some stylistic analysis.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

Shirley Clarke was a major director of experimental and documentary films. Portrait of Jason, her feature-length recording of the recollections and comments of a gay black man was re-released in a restored version last year. “I’ll never tell: JASON reborn” discusses its avant-garde approach to recording its subject’s account of what may or may not be the truth. The entry also details the restoration process, which involved material Clarke deposited at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s archive, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

Of the five animated features from 2012 nominated for Oscars this year, three were made using the traditional stop-motion technique with puppets: Frankenweenie, The Pirates! Band of Misfits, and Paranorman. “Annies to Oscars: this year’s animated features” discusses them, as well as the computer-generated features, Brave and Wreck-It Ralph.

Chapter 11 Critical Analysis of Films

During the past year we’ve written quite a lot about film analysis. These entries might give some encouragement and suggestions to students embarking on their own critical studies of films.

In June the new online film journal, The Cine-Files, interviewed Kristin about her approach to film analysis. The editors kindly allowed us to post the interview, “Good, old-fashioned love (i.e., close analysis” of film” on our site as well. The interview includes discussions as such topics as, “Please tell us about something that couldn’t be understood without a frame-by-frame attention to detail.” It also discusses our recent forays into online video and PowerPoint analysis.

A lot of interpretation of films gets done, by professional critics and students, by fans, and by anyone who gets an idea about a film and offers it to the world. In Film Art, we suggest that valid interpretations of films tend to be based on close analysis of all aspects of the film. Needless to say, not every interpreter does the work of analysis before expounding their ideas. The feature documentary about amateur interpretations of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining gave us an opportunity to discuss this tendency in “All play and no work? ROOM 237.” Surprisingly, some ideas offered by the subjects of the documentary aren’t necessarily that different from those propounded by professionals.

Christopher Nolan is one of the most admired filmmakers in contemporary Hollywood. What sets him apart? We discuss some of his innovatory tactics in “Nolan vs. Nolan.” The focus is on Insomnia, but with mentions of Magic Mike, Memento, Inception, and The Prestige. The latter is our primary example in Film Art‘s chapter on sound, and this entry might offer useful background material for teachers who show The Prestige to their classes.

For many students, non-Hollywood films can be intimidating to watch and even more so to analyze. “How to watch an art movie, reel 1” offers hints for understanding and discussing art films. The film in question is Jaime Rosales’ Spanish film Sueño y silencio (2013). It hasn’t been widely seen, but one need not have seen the film to understand the analysis of its first twenty minutes. This entry discusses conventions of the art film that might help students in writing their own essays.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

One section of this chapter deals with “The Development of the Classical Hollywood Cinema (1908-1927).” In another new video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies 1908-1920,” we deal with the same period on an international level. The lecture traces many of the basic techniques of cinematic storytelling in use in modern cinema back to their origins in this crucial early period. For an introduction to the video, see “What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah …”

Of the three major European stylistic movements of the 1920s discussed in Chapter 12, French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage, Impressionism has traditionally been the most difficult to teach, due largely to a scarcity of prints of films from the movement. Now a group of major Impressionist films have become available on DVD, those made by the Soviet-emigré Albatros production company. In “Albatros soars,” we describe the films and their release in a prize-winning box set from Flicker Alley. We think students would find La brasier ardent intriguing, if puzzling.

David is at work on a book on 1940s Hollywood cinema. Left-over ideas from that project end up as blog entries now and then. These could fit in with the section, “The Classical Hollywood Cinema after the Coming of Sound, 1930s -1940s.” One such entry, “A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick,” looks at the hands-on approach of David O. Selznick, arguably the most important independent producer of the era. His guidance affected the style of Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, Spellbound, Duel in the Sun, and other classics of the Hollywood system. Another entry considers in-jokes planted in 1940s films.

David has also posted a related essay in the main section of his website, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense,” dealing with the influence of mystery and detective fiction on films of the 1940s. For an introduction and link to this essay and to several other blog entries on filmmaking of the decade, see “The 1940s, mon amour.”

The final section of Chapter 12 deals with “Hong Kong Cinema, 1980s-1990s.” The recent death of Lau Kar-leung, one of the major martial-arts choreographers and directors of the 1970s and 1980s, led us to post an appreciation of his style and films in “Lion, dancing: Lau Kar-leung.” The final section provides many bibliographical sources and other information on Hong Kong cinema, as well as links to earlier entries on the subject.

Johnnie To is one of the few directors still successfully maintaining the tradition of Hong Kong action films. The latest of our entries on him deals with a recent release: “Mixing business with pleasure: Johnnie To’s DRUG WAR.”

DVDs to consider

At intervals we post round-ups of recent DVD and Blu-ray releases. The titles usually aren’t the big, recent, popular films, but more specialized items put out by companies like Flicker Alley, Eureka!, and Kino that specialize in issuing classic films, often in beautifully restored versions. A lot of these films have never been available on home video before, and they open up new possibilities for teachers who want to broaden their students’ viewing experiences. They’re also titles to recommend to those enthusiastic students who want recommendations for films they can view on their own.

“Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, for a fröliche Weihnachten!” deals mostly with German silent films, including a set of four starring the early superstar Asta Nielsen, and two films by G. W. Pabst: the first release of his debut film, an Expressionist-style work called Der Schatz, and the most complete restoration so far available of The Joyless Street. A new and longer version of Ernst Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao is included, as is a charming Technicolor version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado from 1939.

Regular readers are familiar with our annual tradition of naming the ten-best films of the current year but of 90 years ago. For once all the films on our list of “The ten best films of … 1922” are all available on DVD, including a stunning print of Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse der Spieler and the Criterion Collection’s release of the Svenska Filminstitutet’s restoration of Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (better known in the USA as Witchcraft through the Ages).

As of September 28, Observations on Film Art will be seven years old.

Fantomas (1913).