Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

70s mixtape hit: Tom Nichols and the Deplorables

From studying the polls, I would guess that about a third of the American people at any given moment would welcome a fascist state.

Gore Vidal, 1975

DB here:

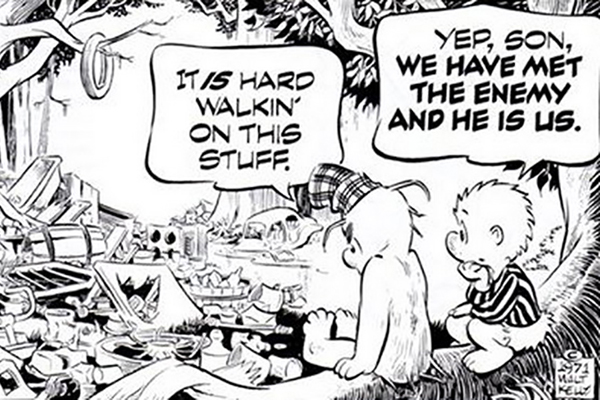

For American conservatives, Hollywood is a prime villain, coarsening the culture and spreading liberal propaganda. Yet when Reagan promised to veto tax-increase legislation, he quoted Dirty Harry’s “Make my day.” He also promoted a “Star Wars” space defense system. Now Steve Bannon models his political ethos on Twelve O’Clock High. Stephen Miller is reported to idolize the Robert de Niro character in Casino, even mimicking his dress code. When Brad Parscale wanted to scare the Democrats, he compared his Trump campaign organization to the Death Star (evidently he didn’t see the movie’s ending). Roger Ailes’ son Zach quotes Tombstone, and Sidney Powell compared her bumbling assault on 2020 election results to an attack of the Kraken. The red pill/blue pill choice from The Matrix is at the center of the ideology of QOnan (not a typo). A conspiracy “meme queen” had a cinematic epiphany about Pizzagate: “The world opened up in Technicolor for me. It was like the Matrix — everything just started to download.”

An academic might argue that right-wingers are practicing their own version of ad subversion, twisting the Hollywood product to their own ends, like a Situationist détournement. But actually, most of these associations may betray the Republican fascination with violence. Pat Buchanan’s command that his followers “Lock and load” and Sarah Palin’s evocation of “Second Amendment solutions” would plausibly lead to a mindset that results in zealous young Republicans in 2007 calling themselves “The Young Guns,” after a now-forgotten western. A famous line in The Town (2010) about going out to hurt some people found an eager GOP takeup.

One would think that the more conspiracy-minded right would fetishize the long-running cycle of Deep-State political thrillers like JFK (1991), Clear and Present Danger (1994), Air Force One (1997) and Enemy of the State(1998), up to Equalizer 2 (2018). Such films center on rogue cadres within the government aiming to undermine official policy by working with ambitious office-holders, zealous bureaucrats, free-lance killers, and terrorists or drug smugglers. This “paranoid political thriller” is one legacy of a cascade of US assassinations in the sixties, resulting in classics like Seven Days in May (1964) and The Parallax View (1974).

Perhaps these too are Golden Oldies for Y’all Queda. But one of the most ingenious appropriations I’ve encountered comes from a less fringe figure. 3 Days of the Condor (1975), another in the Deep State cycle, is invoked in an unusual way in a new book by Tom Nichols. Like other conservatives, he finds that it illuminates contemporary politics, but not because of its revelation of off-the-books intrigue.

When the hero-on-the-run Robert Redford says he’s revealed the conspiracy to the press, Cliff Robertson as the CIA man isn’t worried. The Times may not print the story, but even if it does, the public won’t care. When the next crisis comes, the people will ask only not to be discomfited. They will expect their government to solve problems they have happily ignored for years.

For Nichols, this is a parable of the decline of American civic virtue. Democracy could end because “uninformed, spoiled, irascible voters simply can’t produce coherent demands other than ‘just get it for us.’” Technocratic elites will oblige in ways that concentrate their power because “bored and dissipated citizens” see the only threats as ones to their living standards.

How did the populace become so infantilized? Our Own Worst Enemy seeks an explanation—one that I find as provocative as it is incomplete. Here’s my take. Yes, films (with spoilers) are involved.

The hippest conservative?

Tom Nichols, 10 June 2021, Sona restaurant, New York City.

For some time, the conservative movement has been in search of a leading public intellectual. William F. Buckley loomed so large for many decades that few late arrivals have matched him, or even George Will. Current contenders include William Kristol, David Frum, David Brooks, and Ross Douthat, but Tom Nichols may turn to be the most widely influential.

He’s a late arrival. Kristol has been on the scene for decades. Brooks and Frum are Nichols’ contemporaries (all born 1960-1961), but they’ve had far more exposure, not least in several books of sweeping political commentary: five from Brooks, nine from Frum. Douthat is nearly twenty years younger than these, but he has already published six books, most claiming some attention. Brooks and Douthat have a powerful platform, the Opinion wing of the New York Times, while Frum, a formidable intellectual, is a senior editor at the newly energized Atlantic. Frum as well has extensive White House experience, notably as a speechwriter for George W. Bush.

By contrast, Nichols has been a scholar specializing in Cold War geopolitics and international relations. He teaches at the U. S. Naval War College and at Harvard Extension School. Fluent in Russian, he has written monographs on military policy with a focus on Soviet and post-Soviet history and nuclear deterrence.

Graduating from high school in 1975, Nichols became a late-stage Cold Warrior. He enthusiastically voted for Reagan twice. He worked for Republican Senator John Heinz, on the recommendation of Jeane Kirkpatrick. He opposed Trump in 2016, but he stayed in the party hoping to break the fever. (Excellent invocation of Die Hard in his declaration.) He broke permanently with the GOP in 2018 when Susan Collins endorsed Brett Kavanaugh for the Supreme Court. He has become another political commentator, writing for USA Today and The Atlantic.

In his new anti-GOP phase, Nichols’ expertise has enabled him to be more prescient than his counterparts. In two 2017 pieces he pointed out problems with the chain of command devoted to launching nuclear weapons, anticipating the crisis concerning Trump and General Mark Milley. In 2020, a week before January 6, he warned that Trump was considering war with Iran after losing the election.

On other fronts, his prophetic powers failed him. In 2016, Nichols was in despair at the Clinton/Trump option; he despised Clinton, a tenable view, but worried about Trump more. His prophetic powers–always at risk among hot-take pundits–were less than accurate, though. If Trump were to win in 2016, Nichols predicted:

His white nationalist supporters, clinging to him like lice in the fur of an angry chimp, will shake their fists along with him for a time, until they too eventually slink away. By 2020, his core constituency will be a tiny sliver of what’s left of the white working class, pathetically standing at the gates of empty factories they thought Trump would re-open.

Conservatives can recover from four, or even eight, years of Hillary Clinton. We might even flourish. . . . [But Trump] will obliterate Republicans further down the ticket in 2016 and 2020, smear conservatism as nothing more than his own brand of narcissism, and destroy decades of hard work, including Ronald Reagan’s legacy.

Oops. Still, he did get this part right:

After four years of thrashing around in the Oval Office like the ignorant boor he is, voters will no longer be able distinguish between the words “Trump,” “Republican,” “conservative,” and “buffoon.”

As you can see, Nichols is a zesty writer, more casually hip than the solemn Frum, the bland Brooks, the grinning and shrugging Kristol, and the piously calm Douthat. Douthat has written film reviews for National Review, but Nichols plunges into popular culture with more zest. He’s a five-time Jeopardy champion, and he loves Star Trek and the band Boston (but is pretty hard on most 70s TV and music).

He also understands the churn of Net life. His early blogs attracted international attention, so with a publisher’s encouragement he developed their ideas into a book, The Death of Expertise (2017). For Our Own Worst Enemy, his “Radio Free Tom” Twitter feed playfully carries out social-media branding. While David Frum provides purchasers of his book dignified bookplates, Nichols offers bookplates with the pawprint of his beloved cat Carla, along with a T-shirt, a playlist of all the songs mentioned in the text, and a contest to find a factual mistake (about a movie, no less) that he spotted too late. He has encouraged readers to send photos of their pets cuddling with the book (#PetsDefendingDemocracy).

He also understands the churn of Net life. His early blogs attracted international attention, so with a publisher’s encouragement he developed their ideas into a book, The Death of Expertise (2017). For Our Own Worst Enemy, his “Radio Free Tom” Twitter feed playfully carries out social-media branding. While David Frum provides purchasers of his book dignified bookplates, Nichols offers bookplates with the pawprint of his beloved cat Carla, along with a T-shirt, a playlist of all the songs mentioned in the text, and a contest to find a factual mistake (about a movie, no less) that he spotted too late. He has encouraged readers to send photos of their pets cuddling with the book (#PetsDefendingDemocracy).

Beyond the PR, his Twitter feed emits a stream of commentary, wisecracks, retweets, and replies to insults. Most Saturday mornings Nichols and two compadres live-tweet their reactions to reruns of Casey Kasem’s 1970s top-forty countdowns. Most famously, he sparked a controversy in 2019 when he declared on Twitter, “Indian food is bad and we pretend it isn’t.” The online battle raged until June 2021, when Preet Bhahrara took him to a New York restaurant and Nichols was won to the joys of biriyani. In the process, the stunt raised over $120,000 for Indian COVID relief.

Nichols is a passionate, ironic presence on podcasts and talk shows, and his rapid-fire sense of humor, fueled by self-deprecating anecdotes and boyhood memories, sets him apart from his more sober counterparts. In 2008, Frum famously complained about the “levity and sarcasm” on Rachel Maddow’s show, but Nichols knows the new rules and he deploys gags, mockery, and bad language with cheerful abandon. As I was writing this, he was sitting with Nicolle Wallace, another renegade Republican, saying that Trump wouldn’t know the Insurrection Act from a Macdonald’s menu. In the pages of the august Atlantic, he declared J. D. Vance an “asshole” (“nothing else will do”), an invective-escalation that leaves his more constrained Times rivals in the dust. Yet he’s not always frivolous. A Greek Orthodox Christian, he struggles with his growing indifference to the Covid deniers who wind up on ventilators.

All in all, a very interesting person. Nichols’ Twitter stream has half a million followers, more than Brooks’ and Douthat’s put together. Publishers dream of writers who get this degree of fan engagement. He has won the allegiance of the major anti-Trump online magazine The Bulwark, run by Wisconsin’s former Rush Limbaugh Charlie Syes. Nichols has announced his retirement from the Academy this year, which will surely allow him more energy for punditry.

Curiously Frum, Douthat, and Nichols run in parallel lanes, seldom mentioning one another, let alone debating or making common cause. They compete to offer differing maps of the American hellscape blasted by Trump and Trumpism. I’m not capable of making in-depth comparisons among them, but I do want to focus on Nichols’ claims.

I think that by pitching its analysis at the level of the sensibility of a group, Nichols’ book misses some particular forces that have tapped into that sensibility. Those are forces that are historical and as we say now, systemic. These forces not only complicate his historical account but reveal some basic flaws in Republicanism and conservatism more generally.

A hotbed of apathy

As the polity becomes more and more conscious of the nullity at the center of American life, there will develop not the revolutionary situation dreamed of in certain radical circles, but, rather, a deep contempt for the nation and its institutions, an apathy bound to be exploited by clever human engineers.

Gore Vidal, 1972

Nichols’ core claim in the book is that contemporary American society is best characterized as one that has abandoned civility and respect in favor of selfishness and entitlement. We are, to use his frequent terms, no longer an adult or a “serious” people.

But who is we?

In interviews he sometimes says he means all of us. But that can’t be right. Thoughtful adults like Nichols, his readers, me, and probably you aren’t the people he criticizes. Nor are the “the most disadvantaged members of society.” They seldom vote, struggle from day to day, don’t show up at Trump rallies, and don’t own pleasure boats. In 2019 they counted as over 33 million people.

In interviews he sometimes says he means all of us. But that can’t be right. Thoughtful adults like Nichols, his readers, me, and probably you aren’t the people he criticizes. Nor are the “the most disadvantaged members of society.” They seldom vote, struggle from day to day, don’t show up at Trump rallies, and don’t own pleasure boats. In 2019 they counted as over 33 million people.

Evidently “we” are not the ultra rich, either—a class fraction to which Nichols makes little reference, despite their outsize role in shaping politics. The “we” of Nichols’ book is a they, a group he calls in an echo of Marx the lumpen-bourgeoisie.

Members of that fraction typified the mob that invaded the Capitol. A lot of the riot’s footage seems to feature classic good ol’ boys, but Nichols doesn’t see them as typical. Forty percent of those arrested, a University of Chicago study claims, were white-collar workers or business owners. Several of those indicted are current or former police officers or members of the military. Nichols invokes vivid instances: rioters chartering jets to Washington, potbellied men trying to swagger under expensive military gear, a realtor who used the insurrection as a marketing tool. So we have to wrap our heads around the prospect that people shopping for granite countertops keep Confederate flags in the guest room. Perhaps all may belong to the group that Nichols’ tweets identify as “Rube Nation.”

In any case, he concentrates on this segment of Trump support, the lower-to-upper middle-class householder enjoying a second home, nautical craft, Disney World vacations, and a truculent attitude. With this vivid prototype, he aims to show how “a sated middle class” became the lumpen-bougeoisie.

Its behavior springs not from material conditions of plutocracy or macro-policies, nor from the members’ social prejudices. Most studies show the strongest correlation with Trump support is not class or education but racial animus, an inference supported by the Chicago study, but Nichols’ book gives racial bias only a couple of pages of attention. He attributes the problem to deeper attitudes born of material plenty. He provides some statistical information, choice quotes from experts and pundits, personal anecdotes, and audiovisual aids drawn from pop culture.

The l-b had so much affluence after the wild 1970s that they succumbed to bad habits. Their standard of living, vastly above that of other nations, pampered them into narcissism. Reviving Christopher Lasch’s 1979 diagnosis, Nichols says that “tempts us away from thinking about the needs of other people and to see them only as objects in relation to our own happiness.” As selfish as spoiled toddlers, and as pain-averse as Princess Buttercup in The Princess Bride, the l-b see that everything is available on demand, and yet they want more. They simply do whatever they can get away with. They are discourteous and entitled. Now people take off their shoes on plane flights, an outrage Nichols aired in 2019 and that provides a vivid example of what’s wrong with us/them.

The l-b had so much affluence after the wild 1970s that they succumbed to bad habits. Their standard of living, vastly above that of other nations, pampered them into narcissism. Reviving Christopher Lasch’s 1979 diagnosis, Nichols says that “tempts us away from thinking about the needs of other people and to see them only as objects in relation to our own happiness.” As selfish as spoiled toddlers, and as pain-averse as Princess Buttercup in The Princess Bride, the l-b see that everything is available on demand, and yet they want more. They simply do whatever they can get away with. They are discourteous and entitled. Now people take off their shoes on plane flights, an outrage Nichols aired in 2019 and that provides a vivid example of what’s wrong with us/them.

Now, though, the l-b’s self-centeredness has become a national threat. Americans have sunk into “perpetual adolescence.” To our overseas friends, this has been evident for a long time; the French call us les grands enfants, the big kids. For Nichols this infantilism is revealed partly through Americans’ fascination with show-business celebrities and empty political stars like Bill Clinton and, eventually, Donald Trump. The inevitable movie example is A Face in the Crowd.

When the l-b are thwarted in their self-indulgence, they get mad. For Nichols, anger joins narcissism as a symptom of the new sensibility. True, Nichols grants that we’re largely happy (especially “wealthy, married Republicans”) but narcissism has made us distrustful of others. Americans poll as angrier than their international counterparts, which again seems inane, given US wealth and power. Yet Democrats are unreasonably angry about Republicans, and Republicans about Democrats, thereby “escalating political differences to existential struggles.”

Anger shades off into a third syndrome of Nichols’ account: ressentiment. He defines this well-worn political concept as “an anti-democratic desire to see [others] torn down in the name of ‘equality.’” It’s that grudging envy, again stemming from overstuffed narcissism, that says you deserve what others have, and they don’t. While Nichols claims ressentiment afflicts the left, his examples lean rightward. Trevor from Tennessee would rather die than support Obamacare; the Tea Partyers favored retaining the safety net for themselves but resent “handouts” to “undeserving” citizens. Nichols even makes common cause with Thomas Frank, outstanding leftist historian, whose account of “Richistan” chronicles the persistent fury of prosperous people driven by the spectacle of others who have still more. The l-b got what they wanted, and seeing that others have more has made them miserable.

Nostalgia is the fourth failing Nichols picks out. The l-b yearn to return to the past. He invokes popular culture to show how people gauze over earlier times (Happy Days, That 70s Show). Yet the same culture gives expression to rage, as in All in the Family, “a constant argument . . . about who was to blame for everything being terrible.” Today’s l-b, declaring they want their country back, are ignoring the real problems of the present in favoring a return to…what? The malaise and oil shock of the 1970s? The Mad Men conformity of the 1960s (but what about all those social conflicts)? Nichols doesn’t get specific, largely confining himself to an interpretation of a Night Gallery episode. By the end of his summation he concludes that not just the l-b but “an entire population” entertains “comforting lies about the past.”

All these frailties are cranked up by the screech of the internet, a site of hyper-connectivity. The speed of online life swamps our ability to reflect on matters in a disciplined way. It exaggerates fear and yet encourages us to seek out the drama and danger of catastrophe. It allows people to share isolated anecdotes that can seem to add up to a trend. Nichols shrewdly points out that the illusory intimacy fostered by Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms has actually fostered conflict—Freud’s “narcissism of small differences.” Quarrels get clicks, so people are encouraged to fight.

Our online access to other lifestyles builds the l-b’s anger and ressentiment. Sunny vacation tweets and virtual house tours show them how people everywhere are richer and happier than we are. To the nationalization of minor local elections there corresponds a nationalization of social activity. Everyone knows about hip-hop, the Kardashians, Friends, and school-board disputes in Chillicothe. Instead of local subcultures, “there is now one culture, mediated through the internet and cable television, and we’re all living in it.”

Even if we were to slow our pace of consumption, the damage has been done. People are already more isolated, depressed, and angry. The architects of social media have trained us too well in self-regard and exhibitionism. Here “we” actually becomes we: Nichols “must admit to my own hypocrisy.” He knows that his career as media pundit, and the success of this book, owe a great deal to the virus of digital culture.

Decades of decadence

Every day we get evidence of Nichols’ case about the Trumpistas’ lunatic self-absorption. The Woodward/ Costa blockbuster, Peril, reports the chatter a Congressman overheard on a Stop the Steal flight out of DC.

America was so bad, so lost, one young man said, “I’m just going to move to South Korea.” . . .

“You should move to Idaho,” suggested one woman.

“I just don’t think they have decent seafood in Idaho,” the young man replied.

Still, one objection to Nichols’ social diagnosis pops up immediately. The liberal wing of the population has grown up with the same sense of entitlement as the l-b. The cosmopolitan upper-middle-class is in thrall to narcissism, ressentiment (status seeking, conspicuous consumption), social-media frenzy, and of course anger at the goobers.

But metrosexuals aren’t storming the Capitol armed with bear spray and plotting to kidnap governors, let alone shooting unarmed citizens. Although conservatives claim that the libs are closet Socialists, the evidence is scanty; Bill Gates is no Kerensky, possibly because half of everything is already his. What is the secret sauce that turns the lumpen-bourgeoisie into a raging army? Nichols doesn’t engage with the most obvious explanations: superstition (e.g., Evangelicalism), gun fetishism, racial prejudice, proud ignorance (Trump: “I love the poorly educated”), bad health, and, well, drugs.

Instead, Nichols paints a landscape of social behavior that I think we can call decadent. This has long been a conservative theme, as Corey Robin points out in The Reactionary Mind: Conservativism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump. Burke and Joseph Maistre found the eighteenth-century nobility weakened by their self-absorption, while Edmond Sorel denounced the bourgeoisie as similarly unable to see how rising tides of revolution threatened their rule.

More recently, in the US, many conservatives saw the war on terror as shaking off Clintonian complacency and taking muscular steps to reestablish American dominance. Donald and Frederick Kagan, in While America Sleeps (2000) lamented the “lack of imagination” that keeps the American bourgeoisie locked in pleasurable security without the need to define itself “by virtue of whom we were up against.” From this perspective, war abroad and cultural strife at home would seem redemptive.

Ross Douthat sounds the theme in a book called, no kidding, The Decadent Society (2020). Adapting Jacques Barzun’s use of the term, Douthat finds that a decadent society enjoys a high level of prosperity and technological development but suffers from “economic stagnation, institutional decay, and intellectual exhaustion.” American life is so flat, hollow, and mired in repetition of ideas, cultural flotsam, and social rituals that no really new force can emerge. (For Douthat, that would partly entail a religious awakening.) Along with the creature comforts Nichols complains of, Douthat sees Americans as having lost faith in the expansionary impulse that opened the frontier and sent men to the moon. He apologizes for defending imperialism, but at least the conquest of other peoples provided “consolation” for Europeans’ waning religious faith.

Needless to say, film is involved. In several pages Douthat finds numbing cultural repetition most evident in Hollywood, which relies on earlier films and legacy intellectual properties. (When did it not?) And yes, Star Wars makes its inevitable appearance. Zeitgeists too. As usual, the 70s were better, when those daring nonconformist movies grappled with reality. I try to type this with a straight face.

Nichols makes no reference to Douthat or his book, but he might have acknowledged that his own worry about American torpor is a diagnosis that conservatives often have to hand. Nichols’ sense of decadence emphasizes loss of civic responsibility, while Douthat is more wide-ranging; but both see our problems as born of a population unable to shake off comfort and become engaged in moving history forward.

We often envision conservative thought as clinging to a status quo, but Robin points out that conservatives are literally reactionary. They define their program by reacting to any threats to social hierarchy, whether that is a revolutionary surge from below or simply a barren landscape of peace and plenty that leaves the populace apathetic and vulnerable to enemies, inside or out.

Hard to be a grown-up

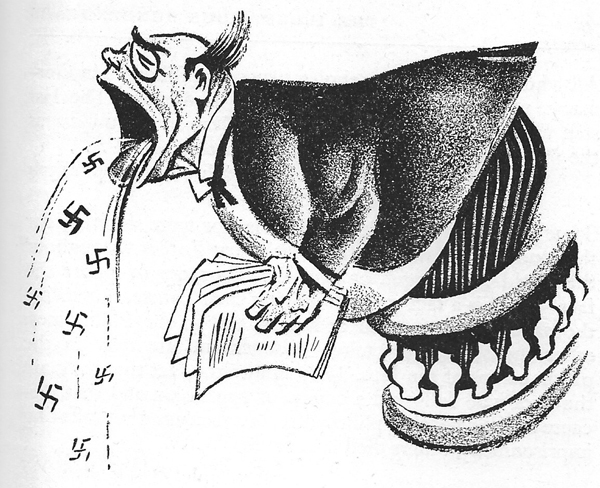

William Gropper, caricature of Rep. Clare Hoffman (R-Michigan)(1942).

Nichols asks virtuous citizens to be “mature” and “adult” and “serious.” We deliberate questions, we trust experts, we avoid conspiracy theories and reckless accusations. Yet this raises the question of whether the political party he has supported for forty years measures up. You can go back to any point in Republican history, but just let me recall the 1940s version of America First and how members of that party responded to it. There are some striking anticipations of today’s rhetoric.

Hamilton Fish (R-New York) 1940: “We don’t want any alien philosophies in this country. This is a Christian American nation. . . America for the Americans—that should be the cry of the America First Committee.” When he referred to “international bankers” dragging the US into war, the crowd cried, “The Jews. The Jews.” Fish smiled approvingly.

Clare A. Hoffman (R-Michigan) 1940: “His [Roosevelt’s] threat to use the sovereignty of a Government is but the threat of a Hitler, a Mussolini, a Stalin to silence all opposition and criticism.”

George Bender (R-Ohio) 1940: “Our people hate everything Hitler stands for, we despise dictatorship in any form, but I challenge anyone to tell us the difference between the Executive Orders issued by Roosevelt and those issued by Hitler.”

Clare A. Hoffman (R-Michigan) 1942: “Perhaps nothing but a march on Washington will ever restore this Government to the people.”

These are the serious people Republicans elected to Congress in the good old days when we were just emerging from the Depression and had to fight a world war. Has the party changed?

According to Nichols, the scales fell from his eyes in 2016, when Trump won the nomination.

I spent nearly 40 years as a Republican, a relationship that began when I joined a revitalized GOP that saw itself not as a victim but as the vehicle for lifting America out of the wreckage of the 1970s, defeating the Soviet Union, and extending human freedom at home and abroad. I stayed during the turbulence of the Tea Party tomfoolery. I moved out briefly during the abusive 2012 primaries. But now I’m filing for divorce, and I am taking nothing with me when I go.

Yet Nichols’ former party has long failed to exhibit the virtues he exalts. During his adherence to the party, the notably unserious Dan Quayle and Sarah Palin were nominated to be a breath away from the presidency. Joe the (not) Plumber was a campaign gimmick. Bush’s Vulcans Cheney (“Reagan proved deficits don’t matter”), Rice, Rumsfeld, Armitage, and Wolfowitz lied the country into two wars, built a mercenary invasive force, and ignored the 9-11 terrorists’ ties to Saudi Arabia.

Nichols was there for the rise of Birtherism in the party, along with the sideshow of backwoods GOP time-servers circulating cartoons of the First Family as sharecroppers and cannibals. He apparently missed the capture of the Party, over George H. W. Bush’s objections (safely in retirement), by the National Rife Association starting in 1995. Nichols says he was “hating on” the Tea Party from the start, but it didn’t nudge him to break. Well before Trump’s nomination, Nichols witnessed Mitch McConnell’s refusal to set nominations for Merrick Garland, which could be a deal-breaker if you think mature adults play in good faith. Today’s canny reinforcement of public distrust was already on display in McConnell’s reply when asked if Obama was a Muslim: “I take him at his word.” On Twitter Nichols deplores our GOP equivocators who dance around questions of vaccination and the legitimacy of Biden’s election. But these hacks are reactivating dodges on display for decades. Dog whistles were never pitched all that high.

As a Boomer, I can match Nichols with a couple of personal anecdotes. In rural New York, I saw often enough the racism that emerges if just one or two Black families move into a community. Classroom: Teacher describes Brazil nuts as “n-gg-r toes.” Schoolyard: Kids surround the only Black student and shout the word at her.

Later, in those narcissistic days of the 70’s, I thought that people lining up for gas during the Oil Shock would later have sufficient memories to be prudent about energy. But when the shortage subsided, people went on to buy gas-guzzling vans and SUVs. A big chunk of the electorate was already pretty infantilized. Thirty years later, at the depths of the 2008 recession (blamed by Nichols on people’s imprudent longing for home ownership), a solid 24% approved Bush’s handling of the economy. The obtuse are a persistent voting bloc.

Nichols is fond of quoting JFK’s “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country” as a clarion call for virtuous citizenship. Yet it was Ronald Reagan who turned that on its head in October 1980: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” True, Reagan went on to worry about unemployment figures and national defense, but pitching the problems as concerning one’s personal comfort looks a lot like “tempting us away from thinking about the needs of other people and to see them only as objects in relation to our own happiness.”

Further, Reagan tapped into nostalgia (“a shining city on a hill”) and ressentiment (the “welfare queen,” the unworthy Black man buying steaks with “our” tax money). For the anger ingredient, he would subcontract that to wingmen like Oliver North. For years his team laughed off the AIDS epidemic. Apart from all that, Reagan didn’t offer us the option of deliberating, as thoughtful citizens, whether “we” should sell weaponry to Iran and divert the money to an undeclared war in Nicaragua.

More on-the-spot evidence emerges from the sorrowful memoir by Stuart Stevens, long-time successful GOP political consultant. It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump (2020) traces in detail how after World War II, and especially after the Civil Rights movement, the party became firmly allied with white supremacy. Unlike Nichols, Samuels puts race prejudice at the center of his argument, making it the very basis of the 1970s Republican resurgence. Well before the rise of Trump, the thought leaders of the right were not legislators but Rush Limbaugh and other talk-radio blowhards, along with Newt Gingrich. In his 2021 preface Stevens admits that even he didn’t anticipate Trump’s efforts to overturn the election, let alone the Stop the Steal rally.

(2020) traces in detail how after World War II, and especially after the Civil Rights movement, the party became firmly allied with white supremacy. Unlike Nichols, Samuels puts race prejudice at the center of his argument, making it the very basis of the 1970s Republican resurgence. Well before the rise of Trump, the thought leaders of the right were not legislators but Rush Limbaugh and other talk-radio blowhards, along with Newt Gingrich. In his 2021 preface Stevens admits that even he didn’t anticipate Trump’s efforts to overturn the election, let alone the Stop the Steal rally.

I could not conceive of the Republican Party becoming the greatest internal threat to democracy since the Civil War. But that is the reality of this moment.

He spares some thoughts for the millions who have bought into Trumpism, but I think that he sets the balance more justly than Nichols does. A long con allows us to blame the victims for their gullibility, especially if they continue to be milked for years. But ultimately we blame the grifter, not the chumps.

Of course many Democrats have been bigoted, corrupt, and mendacious. There were Dixiecrats and brutal Democratic political machines ruling cities. (One reason not to join either party and instead support select candidates.) But it’s fair to bring up GOP names, then and now, because Nichols relies on a personality-centered conception of mature human agency: temperament as projected publicly, as opposed to socially mediated action.

I was struck by a central anecdote. His father, a staunch Republican, declared that the country would be “just fine” whether Romney or Obama won in 2012. “They’re both good men.” Putting aside the charge that Nichols here indulges in nostalgia, is that really a mature, adult judgment?

Mitt Romney is a financial speculator, famed for asset-stripping distressed companies into bankruptcy and wiping out jobs. (He was attacked as such by none other than Gingrich.) He ran for office on a Republican platform that vowed to cut corporate tax rates, reduce Medicare, privatize Amtrak and other intercity rail systems, block union organizing, and initiate a Constitutional amendment to limit federal spending. The platform also maintained that states had the right to forbid same-sex marriages. Romney’s purported principles would not leave everyone “just fine.” And even though he once joined a George Floyd protest march, he’s given no sign of opposing the voter-suppression measures now under consideration in dozens of states.

There’s much to be said against Romney’s presidential rival Obama as well, but surely Nichols would declare that the crucial factor in judging either man’s candidacy is not whether you think well of the guy. He praises his dad for equanimity, but by his own standards, that isn’t enough for informed citizenship. Mature judgment requires understanding of substance, process, and context–and taking action.

A movie memory of mine matches 3 Days of the Condor. I grew up fed on the films and TV shows providing social commentary from a more or less Democratic angle. I was also tempted by stronger appeals; in high school I subscribed to the newspapers of the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Socialist Labor Party, as well as The New Republic. Later I would recognize Preminger’s Advise and Consent (1962) as the best movie about Washington politics (i.e., gridlock).

Rediscovering The Best Man (1964) lately, I think Cliff Robertson’s sound-bite speech to a Convention gaggle might have reinforced my teenage skepticism about the GOP. Robertson is a right-wing Democrat trying to wrest the nomination from Henry Fonda, an Adlai-Stevenson-style intellectual.

Despite his noble principles, Robertson is prepared to play very dirty. At this moment, he is threatening Fonda with circulating confidential documents about treatment for a mild breakdown. That is still the GOP strategy. The bafflegab about patriotism, limiting government, balancing the budget, and accepting “personal responsibility” is a fig leaf for the urge to install power where it belongs, among the rich, mostly white, mostly male elite.

But even if you’re not that skeptical, you have to admit that nearly sixty years ago Gore Vidal’s screenplay distills the essence of unchanging conservative values. With almost no changes Robertson’s speech could be delivered today by the “serious” party patricians. It was all a lie, Stevens says. Could Nichols issue a similar judgment? Or is the blame with us because we were lazy, ignorant, and dumb enough to believe the lie?

Well, not all of us were.

What happens between elections

Katie Porter questions Jamie Dimon, 10 April 2019 at a session of the House Financial Services Committee.

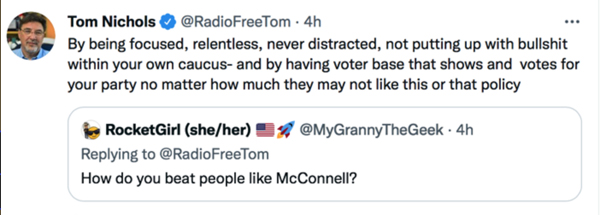

Just as he reduces human agency to displays of cultivated virtue, Nichols relies surprisingly often on a narrow basis for political activity. His “we” are almost completely characterized as voters. That’s where their power lies. A recent Twitter riposte has a suggestion.

For Our Own Worst Enemy, the primary role of citizenship, it seems, is that of casting a ballot. We are lazy consumers; we need to become informed, committed voters. (Nichols’ entire defense of his position on a Daily Beast podcast relied on voting statistics.) Constantly invoking “participation,” he doesn’t analyze what people might do between elections.

Nichols’ American “we” doesn’t include activists, street marchers, petitioners, whistleblowers, strikers, strategic investors, boycotters, donors to good causes, voter registration solicitors, or volunteers at food banks and homeless shelters and vaccination centers, let alone professional social workers, medical workers, researchers, teachers, public defenders, civil servants, and others trying to improve the lot of the world with a day job.

What about the media? Despite the faults of much reportage, the fall of Trump owed a good deal to a critical press. Academics have also played a role. Chomsky has long been the leader here, but he has many other counterparts. Without William Cronin’s research into ALEC, would we know about the way this shadowy group produces “model bills” that are virtually Xeroxed into legislation throughout the states? (Despite Republicans’ lip service to free speech, Cronin was hounded and smeared.)

Every day the Southern Poverty Law Center, Marc Elias’s Democracy Docket, Chef José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen, and other organizations exemplify the robust civic virtues that Nichols finds lacking in the l-b. Not all of us on are Facebook all the time; some do political work, and not just as campaign workers.

Some of us even run for office. If Nichols really values mature, precise inquiry, he might pick out some moments in Congressional hearings: Katie Porter poleaxing Jamie Dimon, Kamala Harris turning a butterball Attorney General to wriggling evasion, or AOC revealing Mark Zuckerberg’s mafioso-level amnesia. Adults do stuff like this all the time.

Such absences are fairly stunning when you consider what was happening outside when Nichols wrote his book. The Republicans’ recent aggressive assault on voting rights came too late to be included in his manuscript, I surmise, but that party’s voter suppression strategies go far back, notably in my state of Wisconsin. They don’t rate notice from Nichols—surprising for a Kremlinologist who might find an affinity with Putin’s “managed democracy.” Black Lives Matter is mentioned only as a pretext for the January Capitol invasion. Our Own Worst Enemy is silent on the atrocities around the shootings of Black people by white cops or the killings of demonstrators in Charlottesville and Kenosha.

Nichols seems to think that the policies we vote for every few years come principally from the professionals, and not from a constant struggle between demands for social change and the moneyed interests controlling elected officials, as mediated by gatekeepers and agenda-setters. As I reconstruct his view, ideally the two US parties hold distinct principles, which they debate reasonably. The principles get hammered into policies, also negotiated and argued over. (Perhaps in Mitt Romney’s “quiet rooms.”) Eventually voters get to decide at the ballot box which policies they prefer.

But of course this story ignores the constant pressures on politicians to enact specific policies benefiting corporations and the wealthy and then to justify them by some public rationale, from “personal freedom” to trickle-down economics. Legislators become lobbyists, corporate players join the executive branch, even the Cabinet. The wealthy’s priorities saturate political culture before, during, and after the moment of an election.

By contrast, Nichols doesn’t treat Occupy, MeToo, people pressing for gun control or clean air or water—all the striving citizens who aren’t at home watching Nascar–as significant participators in political culture. Yet through public protests and community organizing, many ideas like same-sex marriage and a guaranteed minimum income have become gradually thinkable for a broad public.

None of these activities figures in Nichols’ final chapter, on what “we” can do. It consists of “modest proposals,” a fair description, innocent of Swiftian irony. More ambitious solutions are dismissed through a strategy of comparison with other countries. Nichols claims that risky populist symptoms aren’t unique to America, because he finds the same illiberal tendencies in Europe and India. Therefore ameliorating US inequality won’t change things because “more equal” countries are seeing the same rise in protofascist movements. Education hasn’t worked either, and persuasion won’t: the Trumpists are “true believers” in Eric Hoffer’s sense, living on belief fixation. In tweets Nichols insists that talking to them is a waste of time.

To go cinephile again, his deep doubt about change is close to that of the professional jury consultant in Runaway Jury (2003). Gene Hackman tells his adversary Dustin Hoffman that people don’t care about gun violence, or much of anything.

Yet unlike the uncertainty at the end of Condor, in this movie things turn out well. A majority of the jury votes against the gun manufacturers—not thanks to John Cusack’s tricks in their deliberations, but through an appeal to reason and empathy. They voted, he reports, according to their hearts. In the Hollywood manner, the film strategically avoids showing us that process, but it holds out some hope that if appealed to, ordinary people can behave with prudence and decency. And our protagonists, Cusack and Rachel Weisz, will turn the payments they extorted from Hackman toward rebuilding a town devastated by a school massacre. This is the Hollywood that conservatives despise. Right-wing fantasies of violence inspire nifty slogans; left-wing fantasies of social justice are brainwashing.

Virtue, and virtue signaling

Women’s March on Washington, 21 January 2017. (Chang W. Lee, New York Times).

Because Nichols plays down the people’s ability to do the right thing outside of clear-cut policy debates, his proposals are oriented toward top-down edicts. He would like to see political parties become stronger bulwarks against demagogues. He’d like to see a “summer of service,” a stint of military training yielding a common experience for all citizens, to replace the “Spartan” volunteer/ mercenary system we have. He’d advocate changes in the Constitution that could expand the House of Representatives or the number of states (but not any eliminating the Electoral College, which would revert to “pure majoritarianism”). Ultimately, through voting we are to reform the political class to reflect a more virtuous, “adult” electorate—which “we” should strive to become.

I’m less narrow in my hopes, and Nichols himself exemplifies why. He has argued that education and persuasion haven’t proven effective in convincing the l-b that their views are deeply mistaken. Maybe nothing reaches this group, but for whatever reasons, American young people may now lean somewhat more liberal than before Trump. Even former Republicans like Nichols (and the Lincoln Project et al.) have been shocked by how their party fostered the rise of right-wing authoritarianism and now embraces fascism and coup-plotting. Women’s pushback against Trump turned GOP adherent Jennifer Rubin into something like a feminist.

Let’s also not forget that, for young Nichols and me and many others, the soft power of the media has long delivered contentious, even mildly critical ideas with an emotional punch that policy debates don’t. That seems to be what provoked twentysomething Nichols in 3 Days of the Condor.

Perhaps events on the ground have made Nichols less conservative? Not completely. He castigates the Democrats as “torn between totalitarian instincts on one side and complete political malpractice on the other,” along the way declaring that liberals believe that “human nature is malleable clay to be reshaped by wise government policy.” Now that’s a book-length argument that I’d like to read, if Nichols addressed expert evolutionary and cultural evidence about human nature.

Still, he thinks abortion should be legal, that the military budget is too big, and that elites “either by design or incompetence, have enriched themselves at the expense of ordinary citizens.” He deplores class disparities, finds the Founders imperfect humans, acknowledges racism among the rural poor (thanks to a scene from Mississippi Burning), declares that racial and gender-based bigotry is unjustifiable, claims that health care is a human right, asserts that the rich should pay more taxes, and announces that popular media sand off the threatening edges of rap and hip-hop to satisfy “the dominant white demographic.”

In his tweets, columns, and Our Own Worst Enemy these comments are mostly offhand and usually followed by a caveat of one sort or another. He offers no example of how elitists could “incompetently” enrich themselves (maybe in an Adam Sandler movie?), and he casually notes there always will be people who cannot make ends meet (the poor are always with us, just never are us). But when in a rare aside he concedes that “the delayed promises of equality to women and minorities. . . will call justifiably enraged citizens into the streets to demand actions from recalcitrant authorities who have been in power too comfortably and too long,” I had to think back to our experience of the Women’s March on Washington. The timing was just right—the day after the inauguration, an immediate thrust in the face of the looming threat. Voters weren’t ready to wait till the next election to confront a career criminal who was, to everyone who had eyes to see, a catastrophic threat to our common good.

You can’t just blame angry, sybaritic voters. The lumpen-bourgeoisie have long been there, ripe for capture. The blame lies centrally with the Republican Party. It more or less accidentally discovered in Donald Trump the figure whose madness could merge the alt-right fringes with the mainstream party elites, and thus provide a juggernaut for seizing power and holding it in perpetuity.

One powerful counterweight to Nichols’ book is Adam Serwer’s The Cruelty Is the Point: The Past, Present, and Future of Trump’s America, a book whose historical and analytical acumen fulfill all Nichols’ demands for mature, nuanced judgment. Same goes for Serwer’s recent outline of the now-exposed Eastman memo. A little more gonzo, but well-documented, is the survey of earlier GOP voter suppression in Greg Palast and Ted Rall’s How Trump Stole 2020: The Hunt for America’s Vanished Voters (Seven Stories Press, 2020). Just as important, Thomas Frank’s The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism (Holt, 2020) saw where Nichols was going in The Death of Expertise:

What has happened, the thinkers of the Beltway and the C-Suite tell us, is that the common folk have declared independence from experts and along the way from reality itself. . . [Nichols] equated populism with “the celebration of ignorance.”

The Republican comments from the 1940s come from the collection of Congressional speeches in Rex Stout’s The Illustrious Dunderheads (Knopf, 1942). As you see, Gore Vidal, one of America’s best essayists, disclosed many of these pervasive forces in the hallowed 1970s. My excerpts come from his provocative collection, United States: Essays 1952-1992. Robert Hughes’ The Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America (Knopf, 1993) also anticipated some of Nichols’ arguments, although he emphasizes “Political Correctness” in the intelligentsia more than “Patriotic Correctness” among the malcontents.

Nicholas Grossman admirably lays bare Ross Douthat’s sophistries here. I’ll just add that most recently, Douthat argues that we ought not to get too excited by the current rate of 1 in 500 US Covid deaths because it could have been much worse–say, 1 in 50–and then people would have taken notice. “If the fatality figures were one-tenth as high, I suspect there would be much more internal liberal debate over the wisdom of the sweeping early response. And if they were 10 times higher, I think there might have been more red-state support for public-health restrictions of all kinds.”

This from the pundit who confidently predicted that Hillary Clinton would win the Electoral College with 322 votes. Four years later, under the title “There Will Be No Trump Coup,” he declared that if Trump lost he would “not attempt some wild resistance.”

Meanwhile, the scenarios that have been spun out in reputable publications — where Trump induces Republican state legislatures to overrule the clear outcome in their states or militia violence intimidates the Supreme Court into vacating a Biden victory — bear no relationship to the Trump presidency we’ve actually experienced.

Again, who is we? And why does this man still have a job?

For what it’s worth, my suggestion three years ago that the Trump regime constituted a slow-moving fascist coup has become more plausible to many. (Surprisingly, as I finish this entry, none other than Robert Kagan.) Other entries on this site include praise for Omarosa’s insights in Unhinged; guarded acceptance of the comradeship of the Lincoln Project; the cinematic dimensions of the second impeachment trial; the currency of a classic documentary; and the political use of associational form in Demi Lovato’s rendition of “Commander in Chief.” On Romney and Obama as storytellers, see here.

Once upon a time in Hollywood, again: Tarantino revises his fairy tale

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019).

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

–Quentin Tarantino

DB here:

Tarantino has often embraced print-based texts that revise or complement his films. He’s shared screenplays that differ sharply from the finished product, and written graphic novels derived from Django Unchained. Now he’s gone farther. He’s published a novelization that playfully modifies the film’s title: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, without the three-dot ellipsis.

Tarantino has often embraced print-based texts that revise or complement his films. He’s shared screenplays that differ sharply from the finished product, and written graphic novels derived from Django Unchained. Now he’s gone farther. He’s published a novelization that playfully modifies the film’s title: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, without the three-dot ellipsis.

Some will say, rightly, that the book is another instance of today’s tendency toward cross-platform narrative, what Henry Jenkins calls transmedia storytelling. As such it sells more stuff, builds fan connoisseurship, and provides academics like me more to talk about.

But I think it does more. Tarantino has long borrowed from popular literature, particularly crime fiction. (The book I just finished writing tries to trace out some of his debts.) With his novelization, he returns the favor by transferring some of his creative methods to the long-form prose format. Moreover, he realized that some conventions of two genres–the movie novelization and the Hollywood novel–could be steered in fresh directions. What he provides, I think, is not only a fresh path through the story world that will tease fans but also another of his accessible experiments with narrative form. As a bonus, the book shows the author to be a stimulating historian of American studio cinema.

Of course what follows contains spoilers for both the film and the book. But since you’ve had a good stretch of time to catch the film, and since the book currently sits at the top of the New York Times bestseller list, I’m hoping a fairly close analysis won’t scare away many readers. Even if you don’t read on, maybe the mere existence of this entry will send you to the two items in this intriguing multimedia package.

TV or not TV: What is the question?

The film weaves together the doings of actor Rick Dalton, stuntman Cliff Booth, and actor Sharon Tate, over the space of a few days. Rick has been hired to play a villain in a pilot for the TV series Lancer, and Cliff, no longer employable as a stuntman, fills his days serving as Rick’s personal assistant, maintenance man, and boon companion. Sharon, wife of Roman Polanski, lives a life of partygoing, shopping, and occasional screen performing. These characters cross paths with members of Charles Manson’s cultist “Family,” who in 1969 actually murdered Sharon and her guests in a home invasion. In the film, things turn out differently. The novelization takes up these characters and basic incidents but recasts them.

The typical novelization is published to promote a film just before its film’s release, and it sometimes serves as an enduring fan memento or a contribution to a franchise’s “canon.” The writer is often working from a screenplay or a detailed synopsis, so changes made in the later phases of production can render the finished film quite different from the book. But Tarantino’s novelization comes two years after audiences saw his film. Many readers have already seen the film, possibly several times, so they will be sensitive to deviations from the original. Tarantino exploits that knowingness in ways that are sometimes traditional, sometimes striking.

As you’d expect, a lot of the book is devoted to filling in the backstory of the three major characters. Flashbacks show how Sharon got to Hollywood and how Cliff became a stuntman (and a killer). Like other novelizations, Tarantino’s fleshes out subsidiary characters as well, providing the sort of enrichment of the story world that fans enjoy. And some scenes omitted from the finished film are dwelt on in the novel. For example, in the original pilot the Lancer half-brothers meet when they accidentally come to town on the same stagecoach. (Sorry about the punk YouTube rip.) Tarantino, always obliging, shot the scene in his own way and provides it as a bonus material on the disc.

The woman in the TV show is the patriarch’s ward, but in the novel and the film she becomes his daughter Mirabella, and thus the men’s half-sister.

Because a novel can plunge us more deeply into characters’ minds, Tarantino can share the thoughts of Cliff, Rick, and Sharon, as well as secondary figures like Squeaky Frome, Pussycat, Jay Sebring, Roman Polanski, and Manson himself. This widening of perspective alters Tarantino’s habitual storytelling method.

I’ve argued that his films rely on block construction, longish “chapters”attached to one character or set of characters. Whether offering us present-time scenes or flashbacks, they remain fairly self-contained chunks, often set off by titles. As a film, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood broke with this scheme somewhat and presented more alternation among shorter scenes, though still anchored to one of the three main characters.

The novel is even more chopped up, presenting the story in twenty-five chapters, many of them including shifts in time or viewpoint. The transitions are clearly marked, with inner monologues rendered in italics and verb tense differentiating the present-time story from flashbacks. In all, the short, sharp scenes sample a broader panorama of Hollywood life than we find in the film, yielding something more like a network narrative.

The same expansion goes for time. The film leaves Rick’s future somewhat open, but the book sketches in his career after his confrontation with the Family marauders. We learn fairly early in the book that in the 1970s he will cut down on his drinking, an important motif in the book. We also learn the career arc of Trudi Fraser, the little girl with whom Rick performs in the Lancer pilot. A more conventional novelization probably wouldn’t include this anticipatory material, because it would foreclose developments that filmmakers might want to conjure up in a sequel.

Still, Tarantino does adhere to his block aesthetic in an odd way. Big chunks of the Lancer backstory not dramatized in the TV episode are given to us in dedicated chapters, written as if they were extracts from another novel. Recounted by an omniscient narration, they treat the Lancer family history on the same fictional level as the contemporary Hollywood plot. Why? I’ll try to explain below.

Tarantino has experimented with viewpoint shifts and replays throughout his work, most notably in the repeated money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown. Now, like a writer of fan fiction, he can extend the strategy to prose. So an episode registered by one character in the film can be filtered through another in the book. The most extended viewpoint displacement involves Cliff’s visit to Spahn ranch. In the film, we’re attached to him throughout, but in the book everything that happens in that scene is restricted to what Squeaky sees and hears. Viewers are likely to remember Cliff’s fruitless conversation with George, so the replay allows Tarantino to build up a more sympathetic portrait of Squeaky than we get in the film.

Two other narrative strategies are more surprising, but both target readers’ memory of the film. First, the book begins with an office conversation between Rick and agent Marvin Schwarz that echoes the restaurant meeting that opens the film. The reader is likely to think that the book’s ending will resemble the film’s end, which shows the Manson followers attacking Rick’s house rather than Polanski’s. This is the most drastic “alternative history” in the film, like the assassination of Hitler in Inglourious Basterds.

But the reader who’s seen the film will be thrown off on page 110. In a flashforward to March 1970, Rick gets a call from director Paul Wendkos inviting him to join a project. Prompted by a teasing remark by Wendkos, the narration quickly summarizes the summer 1969 invasion and its aftermath before briskly scanning the effect on Rick’s career in the seventies. If you’ve seen the movie, now you can’t be sure what will happen at the end of the book. Will the book’s climax replay the movie’s firefight? Or will something else tie up the plot? Call it show-offish or shrewd, Tarantino’s anticipation of the film’s ending has activated the reader’s awareness of his choices about narrative structure.

Related to this replacement-ending problem is a shift in rendering the filmmaking process. The film shows two scenes of the Lancer pilot being filmed. In the first, Johnny Madrid/Lancer rides into town, shoots down a hired gunman, and discusses joining Caleb DeCoteau’s gang. In the second scene, Caleb holds Lancer’s daughter Mirabella hostage while he arranges for ransom from Scott Lancer.

But the novel version only alludes to these scenes; it doesn’t dramatize the filming of them. The meeting of Johnny and Caleb is presented as part of the inserted Lancer “novel,” while the hostage parley is merely mentioned. The only scene that the book describes being shot is one for Rosemary’s Baby.

Instead, the novel dwells on what happens before shooting. On a porch Rick and Trudi discuss acting in general, and later she urges him to scare her during the hostage scene. Tarantino suppresses the act of filming this big scene, simply indicating laconically: “And Caleb and Miranda act out the scene.” Likewise, Sharon Tate, recalling her slapstick scene in The Wrecking Crew, dwells on what happened before the camera rolled.

Why the shift from filming to preparation? I’ll suggest one possibility a bit later.

Palimpsest of a period

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a “Hollywood novel.” Typically that genre centers on the rise and fall of a fictional star (Inside Daisy Clover) or an executive (The Last Tycoon), with glimpses of production woven in. The fictional characters dominate the plot, but there are references to actual people and studios, which (libel laws being what they are) serve mostly as colorful background. Tarantino follows these guidelines, but he offers a deeper analysis of American film history than any other Hollywood novel I know.

His isn’t a dry historical approach, though, because of the flamboyance displayed by the narrator. Instead of giving us a prudent bystander’s account in first-person narration, as What Makes Sammy Run? does, the book presents an omniscient yarn-spinner addressing us through phrases like “And bear in mind,” “Now, truth be told,” and “You must remember.” At the same time, efforts at purely literary bravado mix the cheap tabloid alliteration of James Ellroy with the weirdness of Cornell Woolrich.

Still, none could really match Aldo Ray when it came to publicly played-out poignant pity.

The six powerful equines come to a gentle stop.

The diminutive Polanski sports bed head on his cranium.

Who’s speaking? This narrator is at once omniscient and lightly personified. The Lancer segments are straight Western-novel narration, except when they’re not.

With his light Texas twang, Monty sang out, “Royo del Oro, last stop!” The backlit sunshine rays filtered through the gauze-like brown dust in the way, a hundred years from now, all cinematographers of western movies would hope to duplicate.

An “I” almost never creeps in, but throughout we’re hearing the Tarantino who produces interview patter and whose screenplays insert wise-ass stage directions.

Freddy finishes his playing-possum piss (Reservoir Dogs).

Everyone is smiling except you-know-who (Pulp Fiction).

From the floor, the bloody, sweaty, and in excruciating pain (she’ll probably lose that leg) German movie star says to the two American soldiers she’s just meeting for the first time. . . . (Inglourious Basterds).

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood goes some way to confirming Tarantino’s repeated claims that when he stops making movies, he’ll turn to novels. I will read them.

Every Hollywood novel is in a sense an alternative history, I suppose, but this unpredictable prose helps prepare us for something peculiar. Start with the time frame. The first and longest stretch of the film takes place on Friday 7 January 1969 and the following day, and these chapters are tagged with time indications. The film then skips ahead to the day and night of 10 August 1969, with the attack on Rick’s home. The book adheres to the February dates but as we’ve seen it “spoils” the film’s climax by announcing the massacre fairly early on.

The central action of the book confines itself to the two days when Rick meets Schwarz and shoots the Lancer pilot, on 7-8 February, 1969. But that chronology is thrown off by another tag. After chapters presenting the day and evening of Friday the 7th, a new chapter indicates that Pusssycat’s Kreepy Krawl (another Ellroyism) takes place at 2:20 AM on that day. It’s either a flashback to an early-morning period before the previous four chapters (why?) or a scene taking place after the earlier chapters, and so is occurring at 2:20 on the 8th, not the 7th.

The Krawl anomaly is an early indication that a misaligned calendar governs the whole book, as it did the film. The actual Lancer pilot was shot in 1968, not 1969. Tarantino has merged events of one year (Rick’s career crisis, the Lancer shoot) with those of a later one (the actual Tate-LaBianca murders).

The typical Hollywood novel inserts made-up stories into a world of real ones, but Tarantino goes further. Your typical director would have pasted Rick on the cover of Time, but Tarantino goes for Mad. Your average movie-geek director would have had Rick reading an actual western novel, maybe Hombre in homage to Elmore Leonard. Instead, Tarantino invents a novel, Ride a Wild Bronc, by the real author Marvin H. Albert, because he wants a parallel between Rick and that book’s hero Easy Breezy. (The fact that Albert himself wrote many novelizations is a bonus.) Likewise, amid a flood of information about genuine Paul Wendkos films and stars therein, Tarantino deletes one actor (James Franciscus) from Hell Boats (1970) to cast the fictitious Rick in the part.

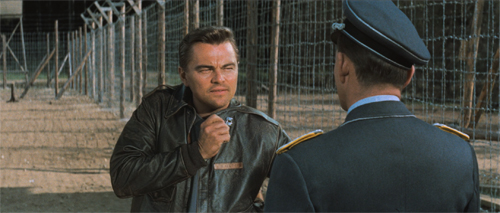

The substitution gambit is literalized in the film, when we learn the gossip that Rick supposedly just missed getting the McQueen part in The Great Escape (1963).

A comparable substitution conceit in the book is the jumble of publisher advertisements printed in the back. What could Tarantino’s book promote? Other books of the period published by Harper, of course: Oliver’s Story (1978), Serpico (1973), and Leonard’s The Switch (1978). The dates suggest that the “original” version of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was published in the late 70s, and this accords with hints in the narration and the book’s design. These period ads sit alongside one for the fake Ride a Wild Bronc and one for a purported hardcover edition of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (fake? forthcoming?).

Yet these dabs of phony history allow the book to float some genuine historical analysis. The constant references to obscure movies and TV shows might be taken as merely Tarantino’s nerdy self-indulgence. In fact, these citations fit into a fairly coherent cross-section of the period’s filmmaking and film culture, with the trends filtered through the business decisions and personal tastes of his characters. 1960s Hollywood turns out to be a palimpsest.

One layer is the fading of the studio system, reflected in agent Schwarz’s boast that he handles old royalty like Farley Granger and Joseph Cotten. Rick expresses his admiration for classic B-picture directors Wendkos and William Witney. Sharon’s backstory, when she hitched a ride to LA, reminds us of the enduring Hollywood myth of fresh-faced outsiders breaking in.

There’s also the new competition from European genres and overseas art films. Cliff, who scorns Antonioni and Resnais, is a big fan of Kurosawa and I Am Curious–Yellow. Now a European arthouse director has made a smash American hit, Rosemary’s Baby, and Rick fantasizes being tapped by Polanski. By contrast, Rick is reluctant to venture into spaghetti westerns, the new territory for a has-been US star.

“TV,” people used to say, “gets ’em on the way up or on the way down.” That’s been pretty much Rick’s career trajectory. Broadcast television has disrupted everything. B-directors like Wendkos shift between the two media, but the A-list older stars can’t sustain a series. Still, the narrator admits that some of these “sought to subvert their personas,” as Henry Fonda did in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Young talent is on the make. James Garner, James Coburn, and many other TV stars can jump to film, while Lee Marvin can shift from B-film villainy to TV heroism (M Squad) and return to films to play dark lead roles. The most shining example is Steve McQueen, who after his series Wanted–Dead or Alive became a top film star. In Tarantino’s film, he’s briefly seen commenting on Polanski’s ménage, but in the book McQueen haunts Rick’s life. The misbegotten anecdote about The Great Escape follows him everywhere.

At forty-two Rick is caught between two trends. He’s loyal to older directors and a classic genre, and he hates Eurowesterns and the counterculture. But to keep working he’s in competition with “the three Georges”–Peppard, Maharis, and Chakiris. Ten years ago he had his own series. Now he must wear a mustache and a biker wig and be the bad guy shot down by the newest “swinging dick.”

Said dick would be, in the Lancer pilot, James Stacy, to whom an entire chapter is devoted. He is the next failed McQueen, the young paladin who started memorably on Gunsmoke but now realizes that the clean-cut bad boy is on the way out. He admires Rick’s early work and envies Rick’s “fucking fly” look as Caleb. He yearns to wear a mustache.

The TV western has developed its own conventions, which Tarantino’s novel filters through the characters’ awareness. Schwarz introduces us to the antagonism between the series hero and the heavy, emphasizing that with every one-shot appearance, the guest star’s image suffers. After Rick reads the Lancer script, he admires its boldness in choosing as a protagonist Johnny, the sort of cocksure hothead who’d normally be shot down in the last act. Trudi is well aware that she is “just the ‘little tyke’ series regular.” More broadly, the book’s narrating voice realizes that westerns are based on “the man of principle pushed past his breaking point and beyond his nature. Most of Greek tragedy, half of all English theater, and three-quarters of American cinema operated from this premise.”

Men in war and at work

Men in War (1957); Aldo Ray on left.

The book spares some thoughts for women working in Hollywood. Schwarz’s secretary Miss Himmelsteen winds up becoming a talent agent who also performs fellatio on her clients. Sharon Tate, who prefers the Monkees to the Beatles, is fully aware that she’s playing the role of “sexy little me” in most social encounters. Yet she genuinely enjoys the audience laughter aroused by her klutzy scene in the not-very-good The Wrecking Crew.

Still, the book dwells far more on the men. The Mannix episode on Cliff’s TV spells it out.

These men are anxious. Both Rick Dalton and James Stacy see their futures endangered. Charlie Manson is trying to build a career in the music business, but his clumsy networking reveals him as a loser. Most strikingly, in devoting seven chapters to Cliff Booth’s life story, the narration presents a composite of trends swirling through the period.

We who’ve seen the film know Cliff’s manic, LSD-buzzed defense of Rick’s home. But who is he? This war hero who has murdered his wife and three other people is a hard case with a soft spot for foreign films. He’s a dog lover who put his pit bull Brandy through harrowing fights. He hurls Bruce Lee against a car but, out of concern for George Spahn, worries that the hippies encamped on his ranch are exploiting him. If Rick and James’ niches in the hierarchy are shifting, Cliff knows his place is near the bottom. Living in a crummy trailer eating Kraft Macaroni & Cheese, he can survive thanks to his muscle and his wits. He might be a man of principle who’s just pushed past his breaking point a bit too often.

Enter Aldo Ray, an actual actor whom Tarantino has long celebrated. Despite working with George Cukor, Anthony Mann, Raoul Walsh, and other top directors, Ray destroyed himself through alcohol and wasteful spending. He gets his own chapter near the end, brought into the story when Cliff is stunting on a runaway production in Spain. While Charles Bronson is becoming a star, Aldo is sinking into a numb despair. He is what Rick or Stacy might become.

As the book closes, this parade of masculine misery replaces the film’s Manson Family siege. After finishing the day’s Lancer shoot, Rick and Stacy head out to the Drinker’s Hall of Fame, a tribute to great Hollywood drunks. Cliff and other acquaintances join them, and they share stories of their sex lives and the productions they worked on. Rick finally manages to spell out why he hates the Great Escape rumor. He admits to his peers that he never really had any chance for the McQueen part. That clarity seems to give Rick a dose of prudence: he leaves early because he needs to learn his lines for tomorrow. For the reader, the drinking bout chimes with Aldo Ray’s plight in the prior chapter, and it suggests how Rick will survive the 1970s. His reconciliation with Stacy will lead both to keep their alcoholism under better control.

Rick’s flash of self-discipline is among the many epiphanies that pile up in the final pages. Sharon, sweet-natured throughout, now gets annoyed with Polanski’s whining bossiness and maneuvers him into holding a pool party. Schwarz calls Rick and offers him a chance for a spaghetti western. Rick runs into Steve McQueen, and his resentment of the superstar drains away in a shared memory of male camaraderie, a pool game long ago. Above all, Rick gets a call from Trudi that resets his relation to his past and his craft.

An actor prepares

Tarantino admires directors, but he adores actors. Has any film more fully portrayed the insecurities of performers? Rick sees his career going down the drain while upstarts like Stacy and the coolly competent Trudi Fraser, only eight years old, are more professional than he is. Rick is baffled by the director’s pretentious ambitions (“Be evil sexy Hamlet”) and rages in his trailer when he blows his lines. Each small error confirms Schwarz’s diagnosis that Rick can flourish only in a downmarket cinema, below even episodic TV.

One of the film’s finest sequences builds enormous tension when it shows Rick struggling to keep up with Stacy in their saloon reunion.

Tarantino could have shot this sequence in 4:3 ratio and TV style, in accord with the Bounty Law commercial that opens the movie. But the bar sequence, like the hostage scene to come later, maintains the same stylistic tenor–widescreen, long takes, rich color–that presents the story of Rick, Cliff, and Sharon. Remarkably, we don’t see any shots of the director and crew watching the performance. The production staff remain offscreen, cueing Rick’s lines. Tarantino has fused the modern camera with the TV camera, “rewriting” the TV production with shadowy modern lighting and arcing camera moves. This filming strategy puts the pilot on par with the surrounding story, just as in the book the Lancer family saga carries the same weight as the 1969 story line.

At the same time, the sequence lets us see just how difficult film acting is. (You can see Stacy trying to match his spoon’s movements to get a clean retake.) An awkward axial cut-in to the bartender delivering Johnny’s beans may be hinting that already Rick has blown a line and they had to reshoot it.

Acting is hard. Even bad acting is hard. Could you or I do what Rick has to do in this scene?

Seeing Rick’s malfunctioning performance in this scene puts more pressure on the big hostage scene, which again runs as if it’s part of the surrounding film. But now, after Rick aces the scene, we get our first crew shot and the director’s happy reaction, along with Trudi’s whispered praise.

Even more than the film, the book pays homage to the strain of actors’ working lives. By sequestering the Lancer episodes in separate chapters, Tarantino can focus elsewhere on the sheer terror of preparation for filming them. Now we see why the book stresses the performers’ leadup to each shoot. We’ve seen in the film how harrowing it is to screw up, and the book digs into the panic of preparation.

Which is why, I suggest, the book ends with one more phone call. (The back cover of the paperback hints at its imporance.) Suspecting that Rick is slacking off, Trudi calls Rick to goad him into rehearsing. As they start to run the lines, they slip into their characters. The narration cooperates.

Which is why, I suggest, the book ends with one more phone call. (The back cover of the paperback hints at its imporance.) Suspecting that Rick is slacking off, Trudi calls Rick to goad him into rehearsing. As they start to run the lines, they slip into their characters. The narration cooperates.

Caleb answers flippantly, “Greed’s what makes the world go ’round, little lady.”

The little lady says her name out loud: “Mirabella.”

“What?” Caleb asks.

The eight-year-old child repeats her name to the outlaw leader. “My name is Mirabella. If you’re gonna murder me in cold blood, I don’t want you to just think of me as Murdock Lancer’s little girl.”

Something about the way she says that registers with the outlaw. And suddenly it becomes important for Caleb to make her understand his fairness on this matter.

Through Rick’s performance the narration can plunge into Caleb’s mind. Things get even more complex when Johnny enters the scene, voiced by Trudi.

Trudi as Johnny points out, “Something happens to that money and we don’t get it, that’s our problem.”

Caleb spins toward Johnny and violently says, “Something happens to that money, that’s her problem!” With fire in his eyes, he tells Johnny Lancer, “Git it straight, boy! . . .”

Very soon Caleb will be shot dead, as enacted by Rick over the phone.

As usual, we won’t see the scene filmed, but Trudi foresees the result. “We’re going to kill this scene tomorrow.” Rick agrees. When she adds that they’re in a great line of work, Rick has his biggest epiphany. Trudi is right. The career that seemed so dismal has let him work with great actors, make love to beautiful women, enjoy luxuries most men never dream of.

He looks around at the fabulous house he owns. Paid for by doing what he used to do for free when he was a little boy: pretending to be a cowboy.

Boys will be boys, apparently forever.

Tracing three movie careers–a fading star, an aspiring starlet, and a below-the-line crew member–the film and the book provide Tarantino’s views not just of swinging-60s Hollywood (“You shoulda been there!”) but what working in The Business is like. Like most books and movies set in the film capital, these two texts show the pleasures and pains of a life that’s at once glamorous and dangerous.

But thanks to visual and verbal bravado, ingenious crosstalk between cinema and prose, and a respect for actors, Tarantino has gone beyond the usual finger-wagging chastisement of Hollywood excess. His taste for low-grade product, which has sometimes seemed an auteur provocation, is revealed as a respect for the desperate energy that animates even barely talented performers. That stubborn struggle, he suggests, is more rewarding than hippies’ hopes to mosey into nirvana.

Tarantino’s respect for those who dare to make movies, even opportunistic and down-market ones, puts him squarely in the classical Hollywood tradition of striving professionalism. His protagonist realizes, Capra style, that he has a wonderful life. Weird as it sounds to say it, Tarantino’s multimedia fairy tale might be the squarest story he ever told.