Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

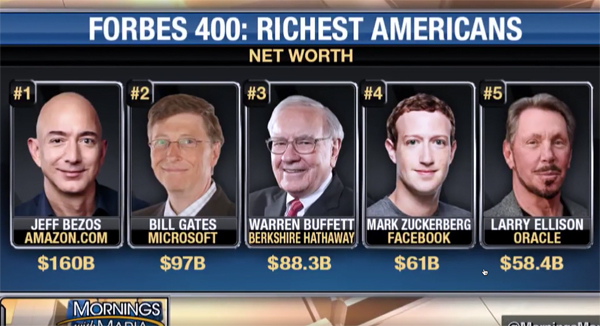

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

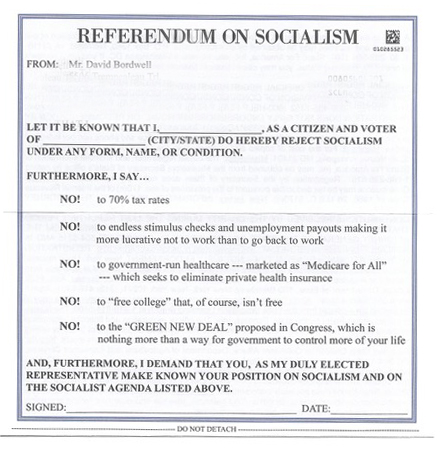

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

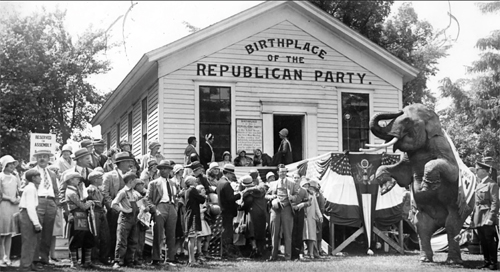

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

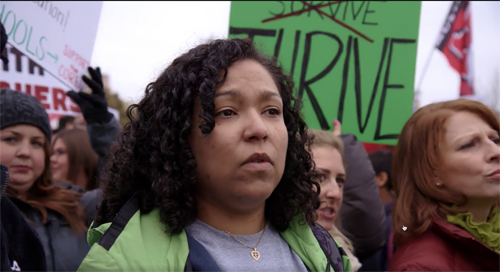

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

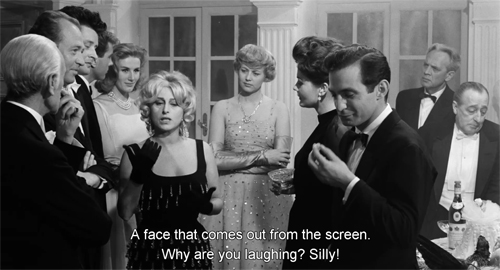

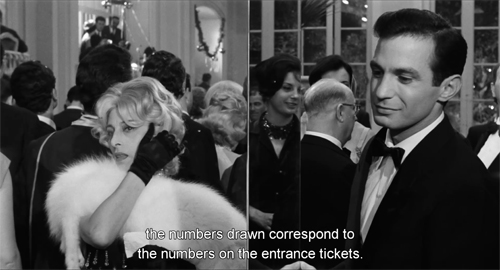

The Passionate Thief (1960).

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).

How the world ended in 1916

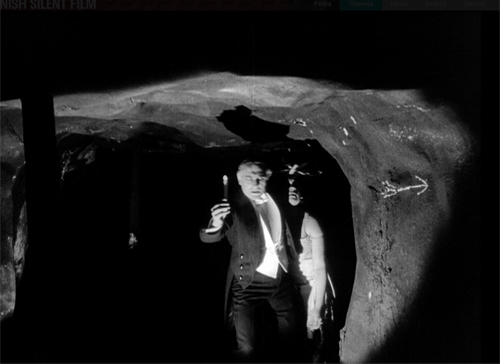

The End of the World (1916).

DB here:

The pull-quote might be “Gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema!” (Too long for a poster, though.) It appears in my essay on a remarkable silent film you may not know. I bet you’d like it.

Danish cinema has gripped my interest for about fifty years. Like most cinéphiles, I started with Dreyer, moved on to Christensen, and then just tried to keep up with trends leading to Scherfig, Vinterberg, Winding Refn, Anders Thomas Jensen, and Dogme. There always seemed to be a new comedy or noir or psychological drama or just weird-ass experiment to keep my loyalty (most recently, the well-crafted Another Round).

One of our first blog entries, on 20 October 2006, was devoted to an anthology on the great film company Nordisk. Soon I was chattering about von Trier’s editing in The Boss of It All and surveying a big batch of recent releases.

Now this national cinema’s silent-era history is coming steadily online. The Danes are too modest to brag about the enormous accomplishment of making so many beautifully restored classics available for anyone to watch. But here they are, accompanied by thematic essays from critics and historians.

Like other Little Cinemas That Could (Hong Kong, Taiwan. Iran), Denmark attracts me because it has shown what can be done a lot of imagination on smallish budgets. Or sometimes, biggish budgets. That’s an impulse that emerged in the 1910s when Nordisk was struggling to keep a foothold in the international market during the Great War. One result was a pair of remarkable spectacles.

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet, 1918) is a massive, nutty plea for peace and international—make that interplanetary—understanding. The Martians are more or less like us, except they don’t kill other creatures, which leaves them time to assemble in carefully picturesque crowds and invest in ambitious infrastructure projects.

The other big Nordisk production was The End of the World (Verdens Undergang, 1916). A comet is plunging toward earth. Can we avoid collision? Or at least survive?

All the conventions of the cosmic disaster movie (Armageddon, Independence Day, 2012) are already in place. We have the innocent family, the corrupt capitalist squeezing money out of catastrophe, the scientists trying to calm the public, and of course the separated lovers who must find one another in the midst of chaos.

The special effects range from passable to truly impressive, as in the model of the village under fiery bombardment, surmounting today’s entry. The comet’s approach is cleverly suggested as a blip in the sky, and the shots of the heroine’s drowned neighborhood are splendid.

Just as remarkable are other technical achievements. The lighting in the underground passages of the capitalist’s mansion, with its Caligariesque steps, could teach the Germans a few tricks, and the miners’ fierce assault on the plutocrats is cut with rowdy, immersive vigor.

August Blom had made his reputation with Asta Nielsen dramas and another would-be blockbuster (Atlantis, 1913). He’s often considered a stolid director, but The End of the World seems to me an underrated achievement. Dismissed by many critics as over-produced, its ambitious spectacle is probably more to our current taste for overwhelming scale. For us, it seems, too much is never enough.

So I recommend to your attention this remarkable movie. As usual, I throw in a case for the 1910s as one of the great and glorious eras of film history. You can handily sample further evidence in the film links alongside the essay.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and his colleagues at the Danish Film Archive. It was fun!

There’s always more to say about the Danes. Outside our blog entries, I’ve written about Nordisk and the “tableau aesthetic” and on early Dreyer in another essay on the Danish Film Institute site.

The End of the World (1916).

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Best Original Song

One Night in Miami (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

On Monday, I offered an overview of the five nominees for Best Original Score as well as a prediction regarding the winner. Today, I do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

As we’ll see, the race in the Best Original Song category is extremely competitive. Indeed, I almost flipped a coin to make my final decision. I didn’t. But the very fact that I thought about it indicates the low level of certainty I have about my prediction.

I should add that there are a few SPOILERS AHEAD. If you don’t want to know some of the key plot twists in Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga or a small but important plot point of The Life Ahead, you can skip to the last section.

Best Original Song: The Underdog

One striking detail about this year’s nominees is the fact that four of the five function as “needle drops” introduced as the film’s closing credits start to roll. Perhaps a steady diet of television episodes streamed during the pandemic has accustomed viewers to expect that this is the way songs now function in movies. Several shows, both old and new, have used these needle drops quite creatively. (I’m thinking here of Mad Men, The Marvelous Mrs. Maysles, and WandaVision. I’m sure you all have your own favorites.)

Set off from the narrative flow of the episode, music supervisors found they could use a song as a curtain closer to highlight elements of theme, tone, or mood without worrying about things like time period or the musical tastes of the show’s characters. Such transmedial influences eventually might establish this as the primary function of popular songs in films. If this year’s nominees are any indication, the trend is already well on its way.

The one exception is “Husavik (My Hometown)” from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga. The film, of course, is a vehicle for star Will Ferrell. He plays an Icelandic version of his usual man-child persona. It adds, though, a musical competition element borrowed from other comedies, like Pitch Perfect, and from popular music shows, like American Idol.

Ferrell plays Lars Ericksong, a humble “meter maid” whose lifelong dream is to compete in the Eurovision Song Contest. Eurovision, of course, is an annual event in real-life. It remains the longest running internationally televised music competition. The contest played an instrumental role in launching the careers of artists like ABBA, Céline Dion, and Julio Iglesias.

Lars hopes to follow in their footsteps, but his ambitions are mocked by the other residents in his small town.

Lars’ only defender is Sigrit, his childhood friend and his partner in the musical duo Fire Saga. Fire Saga plays a vital role in the town’s musical culture, performing regularly at a local bar. Yet their audience mostly rejects their musical offerings. Instead, they prefer “Ja Ja Ding Dong,” a sexually suggestive nonsense song that is the antithesis of past Eurovision winners.

Sigrit, played winningly by Rachel McAdams, is steeped in Icelandic folklore. She makes offerings to a small den of elves that she hopes will prompt Lars to return her considerable affections for him. She also believes in the “speorg note,” a mystic tone that Sigrit’s mother tells her represents the truest expression of the self.

Fire Saga enters the national competition hoping to earn the honor of representing Iceland. During an Icelandic Public Television meeting, their song is picked at random simply to meet Eurovision’s requirements for a country’s eligibility. At Reykjavik, Lars and Sigrit nervously wait backstage for their performance. Sigrit wishes that she could sing in their native language since it would calm her down. Lars, though, warns against it noting that a song in Icelandic would never win Eurovision.

Fire Saga loses to a talented competitor named Katiana, played by Demi Lovato in a nice cameo. Embittered, Lars refuses to attend a party celebrating the winner and Sigrit joins him in solidarity. When the boat hosting the party explodes, killing everyone aboard, Fire Saga becomes the Icelandic entry as the only surviving runner-up.

Once in Edinburgh, the site of the 2020 competition, Lars and Sigrit clash regarding the best way to present their music. (In reality, the 2020 Eurovision contest was to be held in Rotterdam but was cancelled due to the pandemic.) Lars wants to wow the audience with elaborate costumes and stagecraft. He also hires a K-Pop producer to remix their recording, giving it a hip new arrangement. Sigrit would rather just let the music speak for itself.

During the semi-finals, Fire Saga’s performance of “Double Trouble” seems to be going well. But Lars’ desire for showmanship backfires when the absurdly long scarf he has given Sigrit gets caught in the gears of his giant hamster wheel.

Sigrit is able to free herself before she suffers the fate of Isadora Duncan. But the hamster wheel breaks free and crashes into the audience. Although Lars and Sigrit recover just in time to finish the song, they are initially met with stunned silence. This is followed by some snickers scattered amongst the crowd. Lars and Sigrit leave the stage dejected, smarting from their humiliation.

Crestfallen, Lars returns to Húsavik, reconciled to life as a fisherman rather than a musician. Sigrit stays behind to continue her dalliance with Alexander Lemtov, a rival contestant from Russia. Sigrit is gobsmacked when she learns that Fire Saga has been voted through to the finals, a plot twist perhaps inspired by the real-life hate-watching that produced surprisingly long runs by American Idol contestants like Sanjaya Malakar.

Lars makes a mad dash back to Edinburgh, both to participate in the finals and to declare his love for Sigrit. Looking like the Gorton Fish guy, Lars sneaks onstage just as Sigrit has begun “Double Trouble.” He stops her mid-phrase and persuades her to sing a new song even though he knows the change will result in Fire Saga’s disqualification. Sigrit begins tentatively but soon grows in confidence as she reaches the chorus, sung in Icelandic much to the delight of those watching in Húsavik. The song builds to its climactic final note, a high C# that is held for several seconds, leaving both the audience and Lars rapt in awe. This time Fire Saga’s performance is met with thunderous applause. In an aside just for the viewer, Lars exclaims, “The speorg note!”

There’s a lot wrong with Eurovision. Some of the film’s gags misfire badly. The race to get Lars from the airport to the auditorium features the kind of crazy stunt work that’s grown stale from overuse. (Think spinning car and reaction shots of screaming passengers!) And at 126 minutes, Eurovision has two or even three subplots too many.

Yet the filmmakers definitely stick the landing with Fire Saga’s triumphant performance of “Husavik (My Hometown).” Seeing Lars cede the spotlight to Sigrit and her rise to the moment brings a lump to the throat, just as it does in other show-biz success stories like 42nd Street (1932) and A Star is Born (2017). (It’s an old formula but a potent one.)

Moreover, the sequence pays off several dangling causes (the reference to Icelandic lyrics in the scene backstage, the rekindled romance of Lars’ father and Sigrit’s mother, the speorg note). Even Fire Saga’s disqualification strikes the right tone by making the duo the musical equivalent of Rocky. They win by losing, content in the knowledge they were worthy contenders and in the realization of what they truly value. Watching the folks back in Húsavik swell with community and nationalist pride is just the cherry on top of a very satisfying sundae.

Any one of Eurovision’s Europop pastiches would have been worthy of nomination. For example, the faintly ridiculous quality of Lemtov’s “Lion of Love” makes it a perfect surrogate for the character’s ostentation and vanity. But only “Husavik (My Hometown)” both tickles the fancy and tugs the heartstrings.

Still, despite its appositeness for Eurovision’s story, I think it is a long shot when it comes to claiming the trophy. You have to go back to The Muppets in 2011 to find an Oscar-winning song in a live action comedy. And that was a strange year in which there were only two nominees. Before that, you have to reach all the way back to 1984’s The Woman in Red. That year, the winner was “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” written and performed by the great Stevie Wonder. Despite its considerable craft, “Husavik (My Hometown)” seems unlikely to alter a trend that rewards songs in dramas rather than comedies.

The Bridesmaid (as in “Always the…”)

This past February, Diane Warren received her twelfth Academy Award nomination for “Io Sì (Seen),” featured in the Italian film, La Vita davanti a sé. Warren has won an Emmy, a Grammy, and two Golden Globe awards, but has yet to claim an Oscar. This puts Warren in some pretty good company. Her colleague, composer Thomas Newman, has been nominated fifteen times without winning. Composer Victor Young received 21 nominations before finally breaking through with Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Sadly, Victor Young didn’t live long enough to actually receive the award. He died at age 57 just months before the ceremony.

Warren’s latest effort, “Io Sì (Seen),” is the type of soaring power ballad she has spent much of her professional life perfecting. The song starts with a modest piano figure that accompanies Laura Pausini’s indomitable voice at a moderate tempo. The lyrics offer a simple but powerful declaration of emotional support regarding the need to be “seen.” Pausini’s voice rises in the chorus as she vows in Italian, “But if you want, if you want me, I’m here.” The addition of a string orchestra and tasteful percussion accents provides additional emotional heft.

The modest arrangement allows the song’s simple beauty to shine through. Its mood and Pausini’s vocal delivery seem miles away from the bombast that made Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” one of Warren’s earlier nominees, a chart-topping single.

For me, though, that is all to the good. La Vita davanti a sé is itself an unassuming coming-of-age tale that depicts the unlikely friendship that develops between Madam Rosa, an elderly Holocaust survivor, and Momo, a 12-year-old orphan from Senegal.

Buoyed by Sophia Loren’s valedictory performance, the song reflects the strong filial bonds that form when Momo becomes Rosa’s ward. The lyrics’ reassurance that “I’m here” capture the ways in which Momo and Rosa have learned to care for one another. Placed just after the funeral ceremony that closes the film, “Io Sì (Seen)” sustains the scene’s bittersweet, melancholy tone and carries it into the credits. The song also reiterates the story’s central themes regarding the need for unconditional acceptance and love’s ability to overcome differences in gender, race, and age.

La Vita davanti a sé has become an unlikely hit for Netflix. At the peak of its popularity, it reached the streaming service giant’s top ten in 37 different countries. Perhaps that sleeper success will bolster Warren’s chances among Academy voters. She is eminently deserving of the award as a sort of career honor.

Could this be Warren’s year? Perhaps. Still, the fact that more famous songs by Warren, like “Because You Loved Me” and “How Do I Live,” also suffered defeat raises some doubts.

Panthers and Boxers and Yippies (Oh My!)

The three remaining nominees are all songs featured in films that look back at the legacy of sixties political activism. Unlike Eurovision Song Contest and La Vita davanti a sé, Judas and the Black Messiah, One Night in Miami, and The Trial of the Chicago 7 all received multiple nominations. Often the halo effect created by that reflected glow can make a difference in very competitive races. Moreover, the two titles receiving Best Picture nominations – Judas and Chicago – also benefit from the massive “For Your Consideration” ad campaigns that appear in trade publications like Variety. All of this suggests that, if you are looking for this year’s winner, you might look here.

Let’s start with “Fight for You,” the groovin’ track by H.E.R. that closes Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah. The song self-consciously evokes music from the period depicted in the film. As H.E.R. told Variety, she wanted the music to have a hopeful vibe, but lyrics that connected to the Black Panthers’ historic fight against injustice. She drew upon the classic soul music of Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone, artists who made records that were both popular and politically astute.

The final product is a remarkable synthesis of these different elements. The syncopated brass and organ chords recall vintage Sly and the Family Stone tunes like “Stand.” The spare but funky bass line and the supple guitar melody wouldn’t be out of place on Gaye’s classic, “Let’s Get it On” while the doubling of H.E.R.’s voice, sometimes in octaves and sometimes in thirds, conjures up his masterful What’s Going On album. The string arrangements and choral melody also bring to mind Curtis Mayfield’s classic score for Superfly (1972) for good measure. Only one of the five nominees will make you want to get up dance, and this is it. With its Funk Brothers arrangement and uplifting social message, “Fight for You” educes a bit of folk wisdom from P-Funk guru George Clinton: “free your mind… and your ass will follow.”

Celeste and Daniel Pemberton’s “Hear My Voice” from The Trial of the Chicago 7 also evokes sixties soul, albeit with more of pop flavor and even a dash of Northern soul. Celeste grew up around Brighton on England’s southern coast. Her interest in music was nurtured by her early exposure to American jazz vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Those influences can be heard in Celeste’s elegant phrasing on “Hear My Voice.” (Beware ads.) But her vocal style has also drawn comparisons to more contemporary British soul singers like Amy Winehouse and Adele.

The end result doesn’t slavishly duplicate any of those other singers, emerging as something else entirely. In fact, although Celeste’s voice has a timbre all her own, to my ears, the slightly retro vibe of “Hear My Voice” evokes sixties pop and blue-eyed soul artists like Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield. The song itself is a mid-tempo ballad with a loping, syncopated beat and an arching upward melody furnishing the tune’s main hook. Pemberton’s arrangement heightens the pop elements in the recording by emphasizing the piano and strings climbing steadily upward.

The Trial of the Chicago 7’s title is fairly self-explanatory, dramatizing the prosecution of activists from the Black Panthers, the Yippies, and Students for a Democratic Society after protesters violently clashed with police at the 1968 Democratic Convention. David’s blog on Aaron Sorkin shows, among other things, how the screenwriter/director drew upon the “drama of ideas,” a tradition associated with “turn of the century” playwrights like Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw. In a slight break from that tradition, though, Sorkin sought to end the film on a note of optimism and hope that would yield a sense of empowerment.

According to Pemberton, the director’s first choice for an end-title song to reflect that tone was the Beatles’ classic from Abbey Road, “Here Comes the Sun.” The composer, though, gently persuaded Sorkin to try something fresh, a new song unburdened by the enormity of the Beatles’ legacy. He also reminded Sorkin of the huge licensing fees that any Beatles song would inevitably command. Pemberton and Celeste’s much-deserved Oscar nomination vindicates the composer’s instincts. Had Sorkin used “Here Comes the Sun,” viewers would have soaked in its upbeat vibe. But The Trial of the Chicago 7 would have gotten only five nominations rather than the six it ultimately received.

Last, but certainly not least, we have Leslie Odom Jr. and Sam Ashworth’s “Speak Now,” featured in Regina King’s directorial debut, One Night in Miami. The film offers a fictionalized account of a fabled meeting of four icons of the 1960s: Malcolm X, Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali, and Sam Cooke.

The group assembles in a room at the Hampton Hotel to celebrate Ali’s victory over then heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. Yet, with only some vanilla ice cream and a flask of booze as party favors, the good-natured banter soon devolves into a debate about the best ways to achieve social change on the path toward racial equality.

Both musically and lyrically, “Speak Now” seems keyed to an important scene in the film where Malcolm chides Cooke for recording trifling love songs rather than music that speaks to the ongoing struggle for civil rights. He pulls out a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and plays “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Malcolm then asks Sam why it is that a white boy from Minnesota makes music that seems so perfectly attuned to the historical moment. Isn’t “Blowin’ in the Wind” the type of song Cooke should write? Malcolm’s criticism becomes a dangling cause that is picked up in the film’s epilogue. As a guest on The Tonight Show, Sam performs “A Change is Gonna Come” for the first time, showing how he embraced Malcolm’s challenge to him.

Beginning with a syncopated acoustic guitar riff, “Speak Now” not only recalls several moments of the film where Cooke pulls out his own guitar, but also evokes the type of folk music that was Dylan’s stock in trade during the early sixties. The guitar is soon joined by a swirling Hammond B-3 organ. The instrument’s timbre evokes both the gospel music that inspired Cooke throughout his career and Al Kooper’s distinctive organ stylings on two Dylan masterpieces recorded after he went electric: Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. Floating above both is Odom’s plaintive voice, urging the film’s viewer to “Listen, listen, listen.” Providing the link between past and present, the lyrics entreat the audience hear to the “echoes of martyrs” and the “whispers of ghosts.” Odom’s soaring falsetto suggests both vulnerability and hope. The song gradually builds, adding strings and percussion, until it reaches a rousing climax.

With its simple arrangement and its mixture of styles, “Speak Now” sounds like the musical child that Bob Dylan and Sam Cooke never had the opportunity to conceive. It provides a fitting end to One Night in Miami by reminding us that the struggle for civil rights continues, especially at a historic juncture where America is challenged to confront the structural and institutional foundations of white privilege and white supremacy.

Prediction

On Oscar night, I will be watching with bated breath to see if…..

…singer Molly Sandén hits the “speorg note” during the performance of “Husavik.” If she does, it will bring down the house (or at least break a few champagne glasses).

But the winner? Your guess is as good as mine. This is among this year’s most competitive races. In Variety, Jon Burlingame notes that Diane Warren’s past nominations made her the early favorite, but adds, “You can’t count out anyone, however, in this year’s level playing field.”

If the vote reflects the song that is most clearly integrated into the film’s story, it’s “Husavik.” It is also rumored to be making a late charge, aided by late campaigns by Netflix and the tiny town of the title.

If, on the other hand, the vote reflects the song that I’d want next in my iTunes queue, it’s “Fight For You.” It’s got a funky groove that just keeps on keepin’ on.

That being said, I don’t think either of those two songs will carry the day. Ever since the nominations were announced, it’s generally felt like a two-horse race: Diane Warren vs. Leslie Odom Jr. The voting could split between those who desire to finally recognize Warren after so many nominations and those who find Odom deserving of the award for Best Supporting Actor but who still voted for Daniel Kaluuya instead.

The fact that Odom is a double nominee would seem to help his chances. But his song’s social significance also gives it a slight edge. In 2015, Common and John Legend took home the prize for “Glory,” their inspirational song from Selma. Like “Speak Now,” the lyrics of “Glory” captured the zeitgeist surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. The message of “Speak Now” is just as relevant and just as timely. It is possible that voters will want to acknowledge it for that very reason.

Still my gut tells me this is Diane Warren’s year. Thirty-three years ago, Warren sat in the venerable Shrine Auditorium as a first-time nominee. She came in with a fighter’s chance. Her song, Starship’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,” had a fighter’s chance having hit the top of the charts in five different countries, eventually earning gold or platinum record status in four of them. But it was aced out by an even more popular song, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” from Dirty Dancing. It had gone to #1 in six countries and earned gold or platinum status in seven different markets.

Warren’s been waiting ever since for a chance to pop the cork in a champagne bottle at an Oscars afterparty. I think the bubbly finally flows for her this Sunday.

Once again, a shoutout to Jon Burlingame for his coverage in Variety of the Academy Awards’ music categories. His analysis of the Best Original Song nominees can be found here, here, and here.

To find short interviews with all of the songwriting teams, check out these items from The Hollywood Reporter and Billboard.

A podcast with H.E.R. discussing her collaboration with Tiara Thomas and D’Mile on “Fight For You” can be heard here.

A very long interview with Daniel Pemberton describing his work on The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be found here.

Leslie Odom Jr. talks about writing “Speak Now” here and here.

Finally, Diane Warren performs a medley of all twelve of her Oscar-nominated songs here.

Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga (2020).

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Original Score

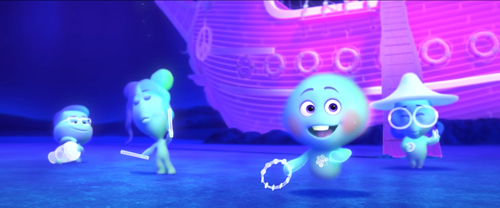

Soul (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

After a short hiatus, I’m back with a preview of this year’s Oscar nominees for Best Achievement in Music Written for Motion Pictures. As with everything else in the COVID pandemic, this year’s nominees represent a slight departure from previous years. With the massive shuffling of release schedules, some films like No Time to Die, Dune, and In the Heights that would have been strong contenders in these categories will have to wait until next year. At the same time, the closure of theaters, and the attendant changes regarding Oscar eligibility, meant that some smaller films’ fortunes were boosted by their availability on top streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime.

Here I survey the five scores that received nominations and offer a prediction regarding the eventual winner. Later this week, I’ll do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

Moreover, I admit that my track record hasn’t exactly been stellar. If memory serves, I’ve gone five for eight in my previous predictions. That’s about a 62% accuracy rate. Better than chance but hardly anything to brag about.

Consequently, I advise readers to treat both predictions as the equivalent of a handicapper’s pick for a daily double. It feels really good if you are right. But truth be told, odds are against it.

Let’s turn now to the nominees for Best Original Score. At first blush, it would be hard to imagine a more disparate group of nominated films. It includes a Western, an adventure film, a family drama, a retro-styled biopic, and a metaphysical comedy in cartoon form.

Composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross are heavy favorites going into Sunday as double nominees. They were recognized both for their jazz-flavored orchestral score for Mank and, along with fellow nominee Jon Batiste, for their electronic atmospherics in Soul. As previous winners for The Social Network (2010), they stand a good chance of adding more little gold men to their mantles.

The long shot

The Oscar betting markets have Terence Blanchard’s score Da 5 Bloods as the nominee with the longest odds. That is a shame insofar as Blanchard remains one of the most underrated composers writing for films. Using a 90-piece orchestra, Blanchard provides an epic sound for Spike Lee’s clever take on The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I wouldn’t say Blanchard and Lee’s collaboration on Da 5 Bloods is a career best. For me, their peak is represented by the magisterial score in 25th Hour (2003), one of the best films of the 2000s. Still, Blanchard’s music for Da 5 Bloods is awfully, awfully good.

Besides the resources of a conventional orchestra, Blanchard also engaged the services of Pedro Eustache to play the duduk, an Armenian double reed instrument that adds an unusual tone color to some of the score’s melodies. The duduk adds a touch of exoticism as a reminder that the protagonist Paul and his crew of Vietnam vets are strangers in a strange land. Yet the score wisely avoids the kinds of Orientalizing musical gestures that are common in many Hollywood films with South Asian settings. The duduk is heard in a handful of cues that underscore Otis’ relationship with Tien, his old Vietnamese girlfriend.

In contrast, strings and brass are key to several cues pitched in an elegiac register. As Todd Decker notes in his book, Hymns for the Fallen: Combat Movie Music and Sound after Vietnam, this style of music became especially common in Hollywood war films after Samuel Barber’s famous Adagio for Strings was used so memorably in Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986). A good example is “MLK Assassinated” where the squad reacts to Hanoi Hannah’s announcement of the civil rights leader’s death.

Blanchard, too, mines this vein in cues accompanying scenes where the crew recalls the death of their squad commander Stormin’ Norman Earl Holloway.

Da 5 Bloods is a film of greed and grief, rage and remorse. Blanchard’s score not only captures the frustrations occasioned by America’s racial reckoning, but also reveals the deep sadness beneath, paying tribute to the sacrifices Black soldiers made while serving in Vietnam.

The Newbie

Our second nominee is Minari, which features the music of composer Emile Mosseri. Mosseri studied film scoring at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston. But he also is a member of an indie rock band, The Dig, which has released three albums and four EPs since their debut in 2010. Mosseri got his first major film assignment in 2019 when he wrote the score for Joe Talbot’s acclaimed debut, The Last Black Man in San Francisco. Mosseri soon established himself as an up-and-comer in the world of American Indie cinema. In 2020, Mosseri not only wrote the music for Minari, but also scored Miranda July’s Kajillionaire.

Minari tells the autobiographical story of a Korean-American family’s move to Arkansas in the 1980s. When Mosseri offered to help with the film’s music, director Lee Isaac Chung gave the composer only one directive. He told him not to do something Korean. Instead, Chung and Mosseri discussed the work of Maurice Ravel and Erik Satie, seeing their impressionistic, delicate tone as an idiom more fitting for the story. Mosseri took the unusual step of writing some sketches before production began. This assured that the tone of the score was “baked in” to the film throughout post-production. It also allowed Chung and his film editor to adjust the duration of shots and select takes to better fit Mosseri’s already existing music.

Given Ravel’s and Satie’s influence on the score, it is not surprising that Mosseri’s melodies and orchestrations emphasize piano and strings. Mosseri, though, varies the tonal palette by occasionally adding voices, winds, and vintage LFO synthesizers, instruments whose timbre helps to suggest the feeling of a “dream-memory” soundscape. Many of the cues unfold as patterns of slowly shifting harmonies. This is evident in “Outro” which can be heard below.

Mosseri notes that the real challenge in the film was to communicate Minari’s warm and gentle tone without being saccharine. The score’s modesty makes it appear to be the polar opposite of Blanchard’s epic style in Da 5 Bloods. Whereas Blanchard goes for emotional sweep and impassioned sorrow, Mosseri strives for reserve and subtlety. Moreover, although Blanchard writes for a 90-piece orchestra, Mosseri’s ensemble is less than half that size. Lastly, whereas Da 5 Bloods contains a lot of music — not just Blanchard’s score, but also another ten period-appropriate songs — Minari has a little over thirty minutes of underscore, heard for less than a third of the film’s 115-minute running time.

Still, Minari and Da 5 Bloods have one thing in common. A film composer’s first job is to serve the story, tailoring their music to the specific needs of each scene. Blanchard and Mosseri have done that as well as anyone this past year. I would be happy to hear either one of their names called out as the winner come Sunday night.

The Oater

The third film nominated for Best Original Score is the Paul Greengrass Western, News of the World. Unlike Mosseri, who is a first-time nominee, this is composer James Newton Howard’s ninth nomination. During a career in Hollywood that spans more than 35 years, Howard has enjoyed close collaborations with directors like M. Night Shyamalan and Francis Lawrence. His music has also been a vital component of popular franchises like The Hunger Games and the Harry Potter spinoff, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

On a personal note, Howard played a key role in my own musical biography. Earlier in his career, Howard did string arrangements and played keyboards on Elton John’s Blue Moves (1976), an album that was among the first dozen or so I bought as a teenager. I also listened repeatedly to its biggest hit, “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word,” trying to slavishly duplicate both Elton’s piano part and Howard’s nifty keyboard solo. Elton won last year for Rocketman in the category of Best Original Song. It somehow seems fitting that Howard could take home an Oscar this year for Best Original Score.

News of the World tells the story of Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, a Civil War veteran who travels across Texas, reading news stories aloud in frontier towns for both entertainment and edification. Early on, Kidd comes across an overturned wagon and discovers a lost child. Abducted by the Kiowa, Johanna was being escorted back to her family by a federal officer when their party was bushwhacked. Kidd learns that Johanna will have to wait several months for the return of the Bureau of Indian Affairs representative. So the Captain decides to deliver Johanna to her surviving family. The rest of the film dramatizes their growing bond as Kidd and Johanna make the 400-mile trek through hostile territory to her aunt and uncle’s homestead.

Adapted from Paulette Jiles’ 2016 novel, News of the World feels a bit like a mashup of The Searchers (1956) and the Coen Brothers’ remake of True Grit (2010). Its kidnapped-child premise seems inspired by the former while the picaresque journey structure and “father-daughter” emotional dynamic derive from the latter.

Several of the film’s plot elements, though, offer comment on contemporary politics. The brusque handling of Johanna by Union Army officials in Texas can’t help but remind us of the Trump administration’s family separation policies. Similarly, when Kidd and Johanna are stopped by brigands from a radical militia, they are taken to a town governed under White Supremacist principles, an episode that serves as a grim reminder of contemporary threats of domestic terrorism.

Like Mosseri’s score for Minari, much of Howard’s music in News of the World strives to capture the intimacy and deepening trust that develops between the central characters. That relationship is reflected in one of Howard’s main musical themes heard here in a cue entitled “Kidd Visits Maria.”

Howard’s cues often feature long languid melodies in the strings, but he also nominally adheres to genre convention by incorporating harmonica, mandolin, banjo, guitar, and scratchy fiddle airs to flavor the score with a folksy, period sound. For a handful of scenes involving shootouts, hazardous travel, and hair’s breadth escapes, Howard furnishes the rhythmic drive and dynamics that give them their emotional punch. But the score is most effective in its quiet and reflective moments. Kidd and Johanna both suffer from a sense of loss and loneliness. As they gradually come to realize how much they need each other, Howard’s music communicates that well of feeling, expressing what the characters themselves are too reticent to admit.

Souls and the Soulless

This brings us to the final two nominees: Mank and Soul. For Mank, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross sought to create a score that would seem experimental if it were featured in a film made in 1940. To some extent, they succeed. By opting for an orchestral jazz sound, they evoke a style that did not become common until the 1950s when it was popularized by later Hollywood composers like Alex North, Elmer Bernstein, and Henry Mancini. Still, despite that disjuncture, Reznor and Ross’ score still seems period appropriate insofar as it recalls much of the popular music recorded during the 1930s.

In preparing Mank’s score, Reznor and Ross decided to write cues in two different, but related styles. One set of cues involved big-band and foxtrot arrangements that would underscore scenes involving studio politics. An example is the cue “Fool’s Paradise” heard below.

The other set of cues deployed an orchestral palette and speak more to Mank’s emotional journey over the course of the film.

Notably, Reznor also admits that they often referred back to Citizen Kane during the writing process. Not surprisingly, some cues, like “Welcome to Victorville” and “Absolution,” sound a bit “Herrmannesque” in their evocation of Kane’s famous score.

A few, such as “San Simeon Waltz,” are even in the lyric mode Bernard Herrmann used in scores like The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). The latter, not coincidentally, was directed by Herman Mankiewicz’s younger brother, Joseph.

For the most part, Mank’s music hits all the right notes, as bracing as a warm breeze on a summer day. The score is aptly sweet and tender for the heart-to-heart talks between Mank and Marion Davies, arch and mischievous for moments that display Mank’s acrid wit. In fact, Mank’s score seems most period-appropriate on the rare occasions when it indulges a bit of “Mickey-mousing.” An example of this occurs in the scene where Mank drunkenly stumbles as he exits a car in front of Glendale Station. As Ross notes, the music “gets drunk” as well with muted horn figures that could easily have been pulled from an MGM or Warner Bros. cartoon. All that’s missing is the sound of Mank’s hiccup.

And then there’s Soul. Reznor and Ross’ collaboration with New Orleans musician Jon Batiste is a favorite with good reason. The film’s protagonist is a jazz pianist, an element of the story that makes music integral to the viewer’s experience. Such narrative motivation has certainly helped several previous winners, like La La Land, The Red Violin, and Round Midnight. It also helps that Soul has swept almost all of the year-end critics’ awards for Best Score as well as winning a Golden Globe, a BAFTA, and a Society for Composers and Lyricists Award.

Like the score for Mank, most of the music for Soul consists of two types. On the one hand, there is the earthbound jazz performed by Joe Gardner, the film’s protagonist. These cues provide Jon Batiste an opportunity to shine. Anyone who knows Batiste from his regular gig with Stay Human, the house band on Late Night with Stephen Colbert, are well aware of his enormous talent. For me, even more amazing is Pixar’s skill in animating Joe’s pianistic skills which mimic Batiste’s virtuoso scale runs and arpeggios.

On the other hand, though, we have the music Reznor and Ross wrote for the film’s depiction of the “Great Before,” the way station where counselors prepare unborn souls for their journey to Earth.

And for the zone, a place where souls can experience euphoria upon realizing their life’s passions.

Some reviewers have characterized these cues as spacey New Age music, and that description has a grain of truth to it. Yet, the sounds created by Reznor and Ross seem more like an extension of the electronic experiments they explored in their cutting-edge work on The Social Network, Gone Girl (2014), and Waves (2018).

According to Reznor, to convey the sense of the afterlife as a world both strange and comforting, he and Ross brought in some ideas about microphone placement, vocal textures, and scraping noises they had tried out in their studio. They also processed the sounds from samples and recordings of instruments to give them a slightly off-kilter quality. Such techniques were intended to underline the “imperfections of humanity” in an interesting way. The end product is a “very sublime synthetic score,” in the words of sound designer Ren Klyce. To it, Klyce added the sounds of waving wheat fields and children’s voices to create an environment that felt safe, peaceful, relaxing, and nurturing.

The tranquil score is a perfect fit for director Pete Docter’s vision of the “Great Before.” Yet it also feels a bit uncanny coming from Reznor, a pioneer of industrial music, a style of rock music as cacophonous, abrasive, and propulsive as its name implies. Reznor’s primal howl as the frontman for Nine Inch Nails remains a cultural touchstone of premillennial, post-adolescent angst. Reznor’s contributions to Soul not only show he has mellowed with age, but also that the guy has got extraordinary range.

Prediction

This is the easy one. Barring some groundswell of support that would produce a Minari sweep, Soul will take home the Oscar for Best Original Score. All of its previous awards are very strong indicators. It’s hard to see how the Academy will be any different from any of the 35 other organizations that have recognized Soul’s score as the best of the past year.

As always, my go to source for information about the Academy Awards’ music categories is Jon Burlingame, Variety’s film music specialist. Burlingame’s coverage of these races is always informative and insightful. Some examples of his reportage can be found here, here, and here.

The Hollywood Reporter also has published some useful articles about this year’s nominees, which can be found here.

Besides the interviews mentioned above, one can find many other interviews through the web. An interview with James Newton Howard about his work on News of the World can be found here.

Discussions with Emile Mosseri about the collaboration with Lee Isaac Chung can be found here, here, and here.

Terence Blanchard talks about the music for Da 5 Bloods and his long partnership with Spike Lee here, here, and here.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross discuss their approach to Mank here.

The duo are featured in a long video discussing and demonstrating their creative process here.

Lastly, a link to Todd Decker’s Hymns for the Fallen can be found here.

Soul.