Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Rotterdam surprises

Mitra (2021)

Kristin here:

On Saturday morning (8:30 am our time), the International Film Festival Rotterdam will be screening its annual Surprise Film. We’re naturally curious to learn what it is. But Rotterdam comes so early in the year that often we go into its other offerings knowing almost nothing about them. Here are two of the very pleasant surprises from recent days.

Iranian cinema from the Netherlands

Kaweh Modiri, the director of Mitra, was born in Iran but has lived in the Netherlands since he was six years old. Still, he remains concerned with Iranian issues and clearly has been influenced by the flourishing Iranian art cinema of recent decades.

Asghar Farhadi’s success in international festivals and territories has been the most influential instance recently, at least outside of Iran. His plots are often built around conflicts, not between good and bad people, but behind people who clash because of cross-purposes. Late revelations and tortured discussions lead to reconciliations that are not the happy endings of Hollywood films but instead are resigned agreements to admit mistakes and make compromises.

Mitra is such a film, but it is based around more politically based conflicts than Farhadi has used–ones that have life and death consequences for those involved.

The film moves between two settings and eras: Tehran in 1981-82, the years shortly after the ouster of the Shah, and the Netherlands in 2019, the fortieth anniversary of that revolution. The opening is set in 1982, when the heroine, Haleh, receives an abrupt, unexpected telephone calls announcing that her daughter Mitra has been executed. We move then to 2019, when Haleh, now an academic in the Netherlands, addresses a conference on “The Islamic Revolution at Forty.” Soon she is visited by members of “The Organization,” a group aimed at bringing down the current government of Iran. They tell Haleh that Leyla, whose betrayal of Mitra caused her death, has arrived with her daughter in the Netherlands. She goes under the name Sale, having appealed for refuge status. The Organization wants Haleh’s confirmation that Sale is indeed Leyla.

The rest of the plot centers around a shifting relationship, as Haleh vows revenge on Leyla. Her goal is complicated by the fact that she has never actually seen Leyla, having only heard her voice. Nevertheless, she calls Sale and is convinced that she recognizes the woman’s voice, even after nearly forty years. Once they meet, however, Haleh seemingly bonds with Sale and her endearing daughter Nilu. Indeed, Haleh’s attraction to Nilu hints at her possible acceptance of Sale as a substitute daughter and Nilu as a granddaughter.

Interspersed with this story are flashbacks to the younger Haleh’s 1981 experiences, when Mitra, who has joined the resistance in Iran, is still alive. Scenes like a clandestine meeting with Mitra at a crowded market emphasize Haleh’s love for her daughter (top of section).

Modiri expertly lures us into sympathizing with all the characters involved. To the end we remain uncertain as to whether Sale, who after some doubts accepts Haleh as a friend and even as a substitute mother in a new land, is actually the treacherous Leyla. Even if she is, is it worth ruining young Nilu’s life to turn Sale in to the ruthless Organization?

Supporting all this is Haleh’s relationship with her brother Mohsen, who at first seems a somewhat comic, eccentric sidekick but is later revealed to be suffering the effects of torture and lengthy imprisonment in Iran. His exchanges with Haleh initially seem like sibling bickering, but he becomes the moral compass that holds her together as she pursues revenge (see top).

Mitra starts out seeming to be a conventional revenge story, but its moral and personal shifts and surprises lead to a moving and not-quite-resolved ending.

The film has had its world premiere at the IFFR and is due for a May 20 release in the Netherlands. I hope it plays other festivals and travels further, because it is a definite contribution to the continuation of world interest in Iranian cinema. Like other such Iranian films, it had to be made elsewhere (the scenes set in Iran were shot in Jordan), but it carries forward what we have loved about Iranian films.

An Australian surveillance-cam thriller

Jonathan Ogilvie’s Lone Wolf (2021) adopts the new convention of creating a story based largely on surveillance and cell-phone footage. In a frame story Kylie, a Special Crimes Sergeant, bursts into the office of an unnamed Police Commissioner and demands that he watch a video she has secretly compiled from a mass of such footage.

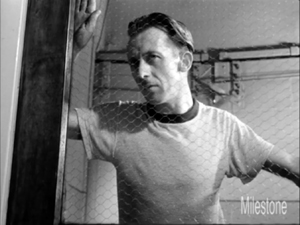

The inner story is seemingly set more-or-less in the present day, but it’s a slightly alternative world in which surveillance has become even more pervasive than it already is. The read-outs in the images reveal that cameras are spying on the characters from such household devices as TVs and smoke detectors. One of these is, ironically, in a bathroom where Winnie sneaks the occasional cigarette by an open window (above). How Kylie gets access to all of these is never explained, and the premise is implausible–especially in scenes built around extensive, undamaged footage which she has somehow managed to extract from a phone that has been through a bomb explosion.

If one stifles such doubts, however, the tale Kylie’s film tells is an absorbing one, full of twists and turns. It centers on Conrad and Winnie, a couple who run a book/video-rental/sex shop and do occasional jobs for underground political groups. They are not the most appealing characters, but they gain our sympathy through their devotion to Winnie’s charming little brother Stevie, who has Down’s Syndrome and an insatiable curiosity about the world.

Australia is soon to host a G20 meeting, and a man from a radical group asks Conrad to set up a “victimless atrocity” in the form of a bomb explosion in a deserted area. At first Conrad refuses, but when offered a large sum, he gives in. Despite the grimness of this plot thread, there is quite a bit of humor in the film, provided by Stevie and by a group of Conrad’s misfit friends who gather to play cards above the shop. The combination of found footage also creates occasionally amusing moments, as when the film-within-a-film includes an instructional YouTube-style video that Stevie has posted or poor-quality footage from an old security camera in the shop that Winnie and Conrad think has been turned off (bottom).

The consequences of the bomb plot introduce a grim twist, but the return to the frame story creates a more gratifying one as Kylie reveals why she has pressed her video upon the Commissioner.

While Rotterdam provided Lone Wolf‘s world premiere, it has a distributor in Australia, though its August, 2020 release was postponed by the pandemic. Ogilvie hopes it will have wide theatrical play after a possible in-person premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival this coming August.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to discover these surprises!

Lone Wolf (2021)

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

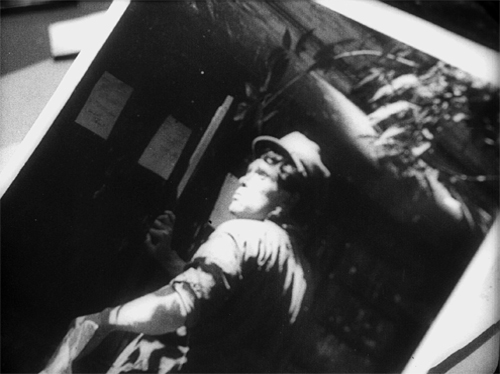

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).

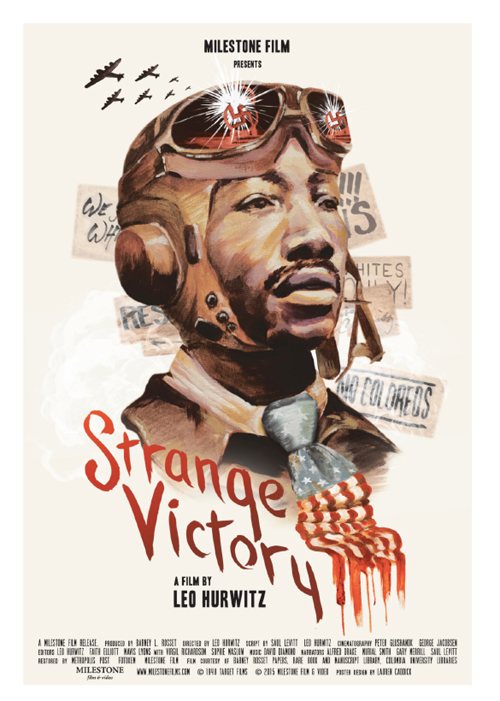

Repost: Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

We have never reposted an entry before, but given recent events in US history, and the celebration of Martin Luther King’s legacy yesterday, and the impending inauguration of a new president tomorrow, we are re-running this entry, unrevised, from nearly four years ago.

It’s not just that it remains timely. (The interpolations remind us that Trump has been inciting violence from the start.) We wanted also to note that thanks to Milestone Films you can stream Strange Victory here. I plan to write more about the end of the Trump era in the days to come, but for now we can acknowledge the struggles ahead of us. We can be strengthened by recognizing that in 1948 people who had sacrificed far more than we have still sustained an urge to fight for decency and justice. –DB

DB here:

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

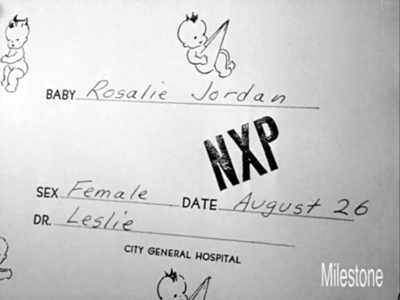

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).

The ten best films of … 1930

The Blue Angel (1930)

Kristin here:

The end of this horrendous year is fast approaching, though we are still facing a long struggle to end the pandemic. On a happier note, it is also time for a little distraction in the form of my annual year-end round-up of the ten best films of ninety years ago. 1930 was also a grim year, with the Depression well established and nowhere close to its end. Herbert Hoover decided not to use federal governmental powers to help end the crisis (sound familiar?) and eventually was cashiered into a 32-year retirement, though he continued to oppose Roosevelt’s policies. At least we don’t face that long a stretch of down time with the current “president.”

I discovered that 1930 did not produce many masterpieces. There are some obvious titles on my final list, as always, but some of the films are good but not great. In any other year they would not have made the cut. (The contrast with 1927, for example, is pretty stark.) Presumably one major reason is that filmmakers were still struggling with the introduction of sound. Fritz Lang didn’t release a film that year, though he came roaring back with M in 1931, as assured a treatment of sound cinema as one could find during those early days. (For those of you who subscribe to The Criterion Channel, I contributed a video essay on sound in M to David’s, Jeff Smith’s, and my series, also called “Observations on Film Art.”) Eisenstein was off in Hollywood unsuccessfully trying to make a film for Paramount and about to fall in love with Mexico. With one notable exception, Hollywood’s important auteurs made no films or minor films or films that don’t survive.

This dearth of really great films will be short-lived. From 1932 on, I shall no doubt have the opposite problem. For now, here are my picks. All the films are worth seeing, though good copies or even any copies of some are hard to track down. (The idea that all films are available to stream online is as absurd as when, back in 2007 when I wrote “The Celestial Multiplex.”) Some of my illustrations in this entry are subpar, but 1930 does not seem to be a year that studios and home-video companies are mining for titles to restore. I hope this entry will give them a few ideas.

I try not to include more than one film by the same director in these entries, aiming for variety and coverage. This year’s most prolific great directors were Josef von Sternberg and Yasujiro Ozu, who together could have filled in half the ten slots, but I have stuck to my guideline. (When we reach 1932 and 1933, I may be tempted to make an exception for Ozu.)

Given that sound developed at a different pace in different countries, some of this year’s films are silent.

For previous 90-year-ago lists, see 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928 and 1929.

Dovzhenko’s Earth

Some of the films on my top-ten list this year may raise eyebrows, but Earth is probably my least controversial choice. It remains one of the last classics of the Soviet Montage movement.

The policy of merging small farms into collective ones had begun in 1927 as part of the First Five-Year Plan. In 1929-30, the push increased, with the seizure of the assets of the more prosperous peasants who resisted collectivization, termed kulaks. Major films were made with the aim of villainizing the kulaks and emphasizing the backbreaking labor involved in traditional, non-mechanized farming. Eager young peasants were hailed as heroes, and tractors appeared as the means to greatly increase wheat yields–wheat which was often seized and sent to the cities to enable rapid industrialization.

Eisenstein had promoted collectivization with his Old and New in 1929, and Dovzhenko followed a year later with Earth. While Eisenstein’s approach had been sarcastic and comic, Dovzhenko pursued his poetic approach to cinema. The opening celebrates the fecundity of the earth and the cycles of nature. The famous opening juxtaposes a peasant girl’s face with a large sunflower. Semion, an aged peasant, is calmly, even cheerfully awaiting his imminent death, lying on a blanket and surrounded by heaps of apples.

A kulak family is soon introduced, angry at the idea that their possessions will be seized. The head of the family declares that he will kill his animals rather than turn them over, and he tries to attack his horse with an axe.

The arrival of the village’s new government-provided tractor marks a shift to an emphasis on the advantages of collective farming. As it approaches, the kulaks stand watching and mocking the idea of a machine taking over. In one shot, an elderly kulak stands framed against the sky, his wealth indicated by the presence of a hefty cow. The tractor temporarily halts, but it turns out that the radiator is dry. The simple solution is for the collective members to urinate into it.

Earth is a visually beautiful film, but like other Soviet classics I have complained about, there is no decent print of it available. The old Kino disc groups it with Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (the cropping of which I mentiooned in the 1927 entry) and Chess Fever. The copy of Earth is too dark and indistinct. To get some frames for illustrations, I watched the visually superior copy on YouTube, but there the images are cropped to a widescreen format. Just as bad, there are ads scattered through it, including one in the middle of Vasyl’s twilight dance in the road just before he is shot!

As before, I must end by pointing out that an archival restoration and a Blu-ray release are in order.

Ozu debuts on the list

Although after 1937 there are years when Ozu did not make a film, he will likely feature on these lists as long as I continue to post them. In 1930 he made six features and a short. Only three survive: Walk Cheerfully, I Flunked, But … , and That Night’s Wife. I’ve chosen the last, though Walk Cheerfully is a viable candidate as well. Sound was adopted slowly in Japan, and Ozu held out until 1936 before releasing his first talkie, The Only Son, which will doubtless feature on my list for that year.

The British Film Institute released That Night’s Wife in a boxed set called “The Gangster Films,” along with Walk Cheerfully and Dragnet Girl. Yes, Ozu made gangster films, including the wonderful Dragnet Girl, the film that might lead me to make my exception in the 1933 entry.

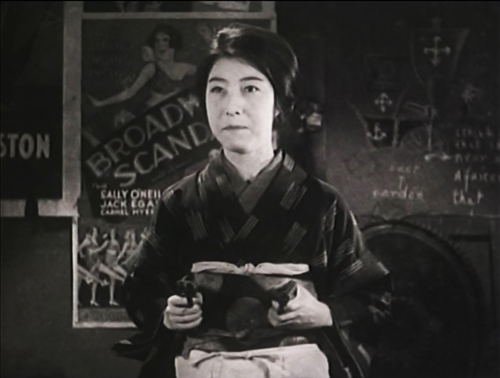

That Night’s Wife, though, is not really a gangster film. Shuji, the father of a daughter with a potentially fatal illness, is not a gang member but a decent working man who stages a hold-up to get money for her medicine. Ozu handles this hoary plot premise with his usual unconventional approach.

The opening, with its shots of dark, empty streets through which the police chase Shuji, is film noir ahead of its time. We soon are introduced to his worried wife, Mayumi, tending the little girl. She’s cute but has a distinctly bratty streak so common to Ozu children. This and fairly frequent moments of subtle humor help Ozu avoid a purely melodramatic presentation of the situation.

Once Shuji arrives at home, Mayumi gets him to confess what he has done. He intends to turn himself in after the daughter’s crisis passes, but a gruff detective who has posed as a cabby to find out where he lives, appears. Being told that the daughter will only survive if she lasts through the night, the Detective agrees to stay and settles in to guard his prisoner. Mayumi reveals her inner toughness and determination to defend her husband. At one point the Detective dozes off and she steals his gun and points it and her husband’s pistol at him, urging Shuji to escape (above). That shot, by the way, shows a motif typical of early Ozu films: having posters, often for American movies, visible on the walls behind the characters.

That Night’s Wife doesn’t display the fully mature Ozu style, but no one would mistake it for a film by another director. He has already mastered the perfect match on action, and he uses one in the early scene where Mayumi sits down as the doctor tends the daughter. Ozu cuts in with a move across the axis of action that places us 180 degrees on the other side of her.

Ozu is not using 360-degree space consistently yet, but he’s playing with the idea. Twice he has transitions that move through a series of adjacent spaces, one of his key devices and one that will last throughout his career. Here we move from the worried Mayumi to Shuji, trying to elude the police after the theft.

There’s a lyrical motif mutating from shot to shot: worried wife, interior lamp, interior plant against wood, outdoor light with leaves, stone building with the shadows of leaves, and stone building with the subject of Mayumi’s thoughts, cowering. But causally the four “extra” shots tell us little about where Shuji is in relation to the home he seeks to reach.

I took these frames from the BFI set, but in the US Criterion released the same three films in its Eclipse brand under the more accurate title “Silent Ozu – Three Crime Dramas.” (I Flunked, But … is in the BFI’s four-film set, “The Student Comedies.” Criterion hasn’t released a DVD of it, but it is streaming on the Channel.)

The Germans’ sound advantage

Unlike other countries, Germany developed its own sound system, owned by the Tobis-Klangfilm company. Tobis was initially able to use court injunctions to keep American films out of the German market. In 1930, this pressure led ERPI and RCA, owners of patents on the major US sound-on-film systems, to form a cartel in conjunction with Tobis, which had producing and distribution subsidiaries throughout Europe. Tobis-Klangfilm continued to dominate European sound recording and reproduction until the beginning of World War II.

Partly as a result of this technical advantage, several early 1930s German films became classics, though not all of them are known abroad.

One internationally famous classic is The Blue Angel. I’ve mentioned that von Sternberg was among the most prolific of major directors in 1930. I debated whether to put this or Morocco on the list. If cinematography were the main criterion, Morocco would have been the choice. Not surprisingly, Lee Garmes’s camerawork and lighting is spectacularly good.

I initially saw The Blue Angel decades ago, in grad school. It was the usual hazy 16mm print of the American release version. Watching it again in the German version, remastered from a 35mm negative, was a revelation. Not that it will ever be one of my favorites. It has its problems. The motif of the clown, implied to be Lola’s degraded ex-lover, is heavy-handed. Emil Jannings’ lumbering performance as Prof. Rath is at odds with the casual realism of the other performances. The time-passing montage accomplished via a hair-curler ripping down a series of calendar pages creates a time gap of years passing and the characters–especially Lola–have changed radically. Her change from a kind attitude toward Rath to cruelty and indifference is logical, given his passive decline from professor to clown, but it is presented too abruptly. Still, in my opinion the film’s pluses outweigh its minuses.

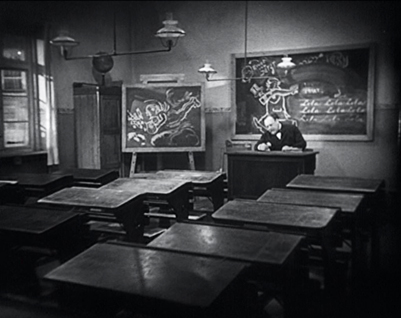

The Blue Angel, seen in a good print, is wonderfully photographed as well (see top). It may not have Lee Garmes, but it has Günther Rittau (co-cinematographer with Hans Schneeberger). He had lensed Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, Heimkehr, and Asphalt. He brings a dark look to the film, as in these shots of Rath in dignified professor mode and later onstage in a caricature of his former self.

The camera movements are rare and unobtrusive. A visual motif set up early on shows the bustling classroom that Rath presides over, where despite the students’ dislike of him, they obey his strict commands. Later, in after Rath has visited The Blue Angel and met Lola, his blackboard is covered with caricatures and insults drawn there by the students to mock his obsession with Lola. A slow track back emphasizes the empty classroom as he sits at his desk, his authority over the students gone.

No doubt it’s a matter of taste, but I find Marlene Dietrich’s performance here more attractive than in Morocco–and it is, of course, central to the film’s appeal. Her amused playfulness with Rath, her quietly sarcastic attitude toward her sexuality being The Blue Angel’s main attraction, and her frequent bits of business with props unrelated to the story all differ considerably from her Hollywood performances. She has a natural glamor here that will disappear in her roles for von Sternberg in Hollywood.

After this film, von Sternberg made Dietrich a Hollywood symbol of glamor, but as a result she tends to be less spontaneous and active, with the camera and lighting lingering over her. Basically her glamor became more sultry. The result has its own appeal (and Shanghai Express is a good bet for a place on the 1932 list), but it is revealing to see her performing in a way that she only recaptured occasionally, if at all, in her subsequent films.

The frames were taken from the Kino on Video two-disc set, which has both the German and truncated American versions, as well as some supplements. It was subsequently released on Blu-ray, but I haven’t seen that version.

I always try to call attention to little-known films rather than sticking to the conventional classics for the whole list–and there aren’t a lot of such classics this year anyway. This time it’s a charming, imaginative musical romance, Die Drei von der Tankstelle, or “The Three from the Filling Station,” directed by Wilhelm Thiele and starring Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch. It was so popular that it outgrossed The Blue Angel in Germany.

Three carefree young men, who start off driving in a car and singing about friendship, arrive in their lavish shared home to discover that they are bankrupt. Low on gas, they are inspired to start their own filling station. They sing a nonsense song, “Kuckuck” (the German equivalent of “cuckoo”) as their belongings are hauled away, and they give this name to their art-deco filling station.

Lilian (the heroine’s name as well) shows up in search of gas for her roadster, and the three men fall in love with her. The rest of the film involves their competition over her. Naturally she chooses Willy (Fritsch’s character name). The two were often paired in later German films of the 1930s and became the ideal movie couple.

The film maintains its playful, often silly tone until the end. As Lilian and Willy are united before a closed theatrical curtain, she turns front and says, “People! The public!” There is an objection that this is not the way to end an operetta and the curtain opens to reveal the entire cast as well as additional dancers and singers performing a lively and somewhat chaotic grand-finale number.

I originally saw this film at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). As it does not circulate in the US on home-video, I have taken these low-quality frames from a homemade DVD, probably originally dubbed from an unsubtitled German VHS copy. It is available on a German DVD, since it is considered a perennial classic there. Unfortunately it has no subtitles. (The German manufacturers do not seem to have cottoned onto what their counterparts in other European nations–notably France–have: that if you include optional English subtitles, you can sell more copies.)

I hope, however, that eventually someone at the DVD/Blu-ray companies will discover this very entertaining film and make it more widely available.

A German director abroad

F. W. Murnau’s City Girl is another of those films I saw in a poor print decades ago and respect a great deal more after seeing it in a good version and knowing more about film than I did then. I wouldn’t put it in the same league as some of his earlier films, but for a 1930 list, it stands out.

Murnau was already on the way out at Fox when he was making the film. After his departure, the film was “finished,” including some dialogue scenes that were inserted. As with several other films of the era, such as Borzage’s Lucky Star and Duvivier’s Au Bonheur des Dames (see below), we are lucky in that only the silent version survives. The restored dialogue scenes in Fejos’s Lonesome show how ghastly these added interludes could be. (My apologies to the restorers. Obviously somebody had to do it.)

The heroine of the title is Kate, a waitress in a busy Chicago diner. Disillusioned by the obnoxious male customers she must cope with and lonely in her sparse apartment (below), she dreams of the apparently peaceful countryside that she sees in pictures. Lem wanders in for a meal, having been sent by his tyrannical father to sell the harvest from their wheat farm in Minnesota. He becomes a regular customer as he stays in Chicago waiting for the price of wheat to rise. His friendly, courteous behavior confirms her idealization of rural life, and they fall in love. Once she arrives at the farm, however, her illusions are shattered by the father’s violent rejection and the loutish behavior of a gang hired to help with the harvest, against neither of whom Lem seems able to defend her.

As in Sunrise, City Girl creates a contrast of city and country, though on the whole the city here comes across as more oppressive than the relatively friendly treatment the couple in Sunrise receive there. Sunrise spends half the film presenting the aftermath to the couple’s reconciliation, while City Girl has a grimmer tone, and the happy ending arrives very suddenly and briefly.

According to Janet Bergstrom’s informative essay accompanying the “Murnau, Borzage and Fox” DVD boxed-set, Murnau initially wanted to film in Grandeur, a widescreen format of the day, but the budget wouldn’t allow it. (I suppose the effect might have worked, as the 70mm version of Days of Heaven demonstrates with a similar locale.) Perhaps it was just as well. Cinematographer Ernest Palmer has handled the landscapes well (top of this section) and given a distinctly documentary look to the harvest scenes.

The restored version of the film in the Fox boxed-set is excellent, but that box is long out of print. British company Eureka! has released City Girl on Blu-ray, which should look even better, available as an import on Amazon.com in the US (where it is listed as Blu-ray but is the same edition as is listed on amazon.co.uk as dual-format Blu-ray/DVD).

The French between silence and sound

René Clair has long been considered one of the directors whose early sound films were among the most imaginative and technically sophisticated. Indeed, that era was perhaps the high point of his career, with Sous les toits de Paris (1930), Le Million (1931), and À nous la liberté (1932) coming out in quick succession. The first two were made for the French subsidiary of Tobis, Films Sonores Tobis, which produced French films in its Epinay Studios. Its prosperity and technical sophistication are evident in the large sets constructed for Sous les toits.

The film centers on Albert, who makes his living selling sheet music to passersby in the street and leading them in sing-alongs. In the opening scene, a small crowd joins in a song called “Sous les toits de Paris” (above). He falls in love with Pola, who is claimed by Fred, one of the many thugs played by Gaston Modot across his career. She moves in with Albert, but when he is framed for a crime committed by Fred’s gang and sent to jail, she takes up with Albert’s best friend.

This light tale gives Clair the opportunity to show off the flexibility and even flashiness of his style. The opening shot is a long crane movement descending from chimneys against the sky to the crowd singing along with Albert. Clair also uses a variety of camera angles, as in the low-angle still above.

There are several carefully lit street scenes, including this one shot in depth with both characters’ backs to the camera as Albert spots Pola outside a bar.

The climactic scene involves a tense conversation between Albert and his pal as Pola looks on. Clair shoots the two men in shot/reverse shot through glass doors, so that we do not hear them but only watch their actions and faces in a deliberate reversion to silent cinema.

Sous les toits de Paris is still in print as a DVD from The Criterion Collection. (An early issue, number 161.)

At least in the US, Julien Duvivier is not as familiar as Clair, being known mainly for Pépé le Moko, but his reputation is rightly growing. David did his part in promoting Duvivier by contributing a video analysis of his 1941 Hollywood romance Lydia on The Criterion Channel.

I don’t know whether Duvivier was inspired by L’Herbier’s L’Argent (which featured on my 1928 list) to make Au Bonheur des Dames, but there are certainly similarities between them. L’Herbier’s film was adapted from the eighteenth novel in Zola’s Rougon-Macquart series, published in 1891, but the film updated the story to the 1920s. Au Bonheur des Dames was adapted from the eleventh novel in the series (1883) and also updated. L’Argent showed the harm done by large banks, while Au Bonheur des Dames deals with the damage wrought on traditional small shops by the rise of huge, corporate-level department stores. Zola had modeled his giant store on Le Bon Marché, while Duvivier was able to shoot interiors for the store “Au Bonheur des Dames” in the Galerie Lafayette–much as L’Herbier had shot in the Paris Bourse over a weekend.

The story concerns Denise (Dita Parlo in her first French film), a naive young woman who comes to Paris expecting to work and live in her uncle’s custom-tailor shop. Instead she finds him on the verge of ruin, since the new department store is located directly across the street. He refuses to sell to Mouret, who runs the department store and wants to expand. But all the shop-owners on the block have given up, and the demolition work removing them gradually drives the tailor mad. In the meantime Denise, fascinated despite herself with the glamor of the department store, gets a job as a model there. She attracts the romantic attention of Mouret and the lecherous attention of a manager and would-be rapist (see respectively in the center and right foreground in the frame above).

Also like L’Argent, Duvivier’s film has strong elements of the Impressionist movement, which was largely over by the late 1920s. The opening portrays Denise’s reaction to the bustle of Paris after she arrives by train by a rapid montage images superimposed around her bewildered face. Later, her uncle’s growing obsession with the demolition of his neighborhood is suggested by many subjective devices, including a prismatic shot of the workers.

There are also many shots staged in depth, including a cut between Denise’s cousin’s fiancé, who has been caught sneaking out to desert her, and a reverse angle (maintaining screen direction) from behind her as he looks guiltily back.

The film was made in both sound and silent versions. Only the latter survives. I watched the Arte Video/Lobster Films version, still in print. (A Facets release in the US is out of print.) The French DVD has English subtitles, as well as a short, informative video introduction by Serge Bromberg in lieu of program notes.

The lingering legacy of World War I

During World War I, the relatively small number of films about the war naturally supported the combat, demonized the enemy, and in the US, urged people to buy War Bonds.

Given the pointlessness and widespread death and injury caused by the war, a reaction soon occurred in filmmaking within the major countries involved. Abel Gance’s J’Accuse (1919) is the earliest film displaying a bitterness about the needless bloodshed of the war, followed soon by Rex Ingram’s adaptation of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 bestseller, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The film made it onto my 1921 ten-best list. There the emphasis shifts to family members and friends of different nationalities having to fight each other (a theme that Griffith had used in The Birth of a Nation). Four Horsemen ended with progressively distant views revealing an enormous cemetery of white wooden crosses, a motif also used briefly in J’Accuse that would become common in pacifist films of the period.

The next big film was King Vidor’s The Big Parade (see my 1925 list), one of the great box-office successes of the 1920s. The filmmakers went so far as to end the film with the hero reunited with his French love, but having lost a leg in the combat. From that point, killing off some or all of the major characters became the norm of subsequent significant anti-war films. (The Big Parade does kill off the hero’s two friends-in-arms.)

The 1930s carried on the condemnation of World War I, with two of the major films on opposite sides being released in 1930. They carry on the idea introduced in The Big Parade that the ordinary soldiers fighting on the German and American sides were basically alike and could recognize each other’s humanity.

G. W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918 starts late in the war, when the German soldiers in the trenches have become thoroughly disillusioned and unspeakably weary. The first big attack on their position turns out to be friendly fire from their own artillery. (The trope of incompetent commanding officers as among the true villains in World War I–and in some case other wars–has lingered in films ever since.) One of the four German soldiers who form the group protagonist falls in love with a French barmaid in a village near the front. In the final scene, huge numbers of casualties from the latest French attack are treated at a German war hospital, with French and German patients mixed together–as the dead had been in the battle itself (see the image above).

Pabst, like other filmmakers, uses the visit home on leave as a way to emphasize the war’s impact on the home front. Karl, the most important character of the four main soldiers, returns for the first time in eighteen months only to find his wife in bed with another man. Pabst introduces the home-front section with a long line of people waiting to buy food. Karl’s mother sees him arrive but cannot greet him because after hours of waiting she had reached the front of the line.

The impressive final battle scene ends with the last of the central characters dead, and the carnage drives the lieutenant who commands them into mad raving.

The film makes a powerful statement designed to end all wars, and yet one cannot help wonder if those Germans inclined to resent the results of the Treaty of Versailles might have been inspired to a greater desire for revenge by it.

The American counterpart of Pabst’s film is Lewis Milestone’s adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front. The 1929 translation of the German novel had become a huge bestseller in the US. Producer Carl Laemmle, who was born in Germany and visited friends and family there regularly, no doubt had a personal as well as a financial incentive to acquire the rights for Universal.

It would be easy to dismiss this big Hollywood production and ultimate Best Picture winner at the Oscars as a slick commercial venture. Certainly it has the glossy, expensive studio look that Westfront 1918 lacks, as in this scene, with its perfect three-point lighting carefully picking out each figure.

Being from a German novel, however, makes this the first significant Hollywood film to treat German soldiers sympathetically and to make them the lead characters. As in Westfront 1918, there is a tight little group of friends, three in this case, with the point-of-view figure being Paul (Lew Ayres). He is the one whom we follow on his visit home while on leave. There he visits his mother, as expected, but he also drops in on his old classroom and is disgusted to find that his teacher is glorifying war and preparing a new generation of young men to go off to become soldiers.

The opening of the film had shown Paul as a student being told of the glories of war and rushing off to sign up. This is the only one of the anti-war films I know of that portrays this sort of social indoctrination as a crucial cause of the horrors of war.

As with the other anti-war films of the 1920s and 1930s, the scenes of are extended and realistic in their depiction of trench warfare. And as in Westfront 1918, all the main characters die. At the end we see them marching off, with vast fields of white crosses superimposed.

The French produced their great anti-war films only slightly behind the Germans and Americans. Raymond Bernard’s masterful but little-known Wooden Crosses (1932), which focuses largely on French troops, is no less powerful in its depiction of trench warfare. Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1938) broke with tradition by downplaying battlefield action and focusing on the senseless loss of life and liberty and the effects of class differences in warfare.

All Quiet on the Western Front has been restored and released on Blu-ray a deluxe edition with DVD and supplements or with the supplements but no DVD.

Experimental cinema in 1930

Surprisingly enough, in a weak year for commercial feature films, there was a considerable number of significant experimental films made. The standard historical accounts when I was a grad student (and probably thereafter) suggested that sound made film production too expensive for the shoestring-budgets of experimental filmmakers. Clearly, though, many of them carried on. Some of the 1930 films are silent, but by no means all. Therefore I’ve decided to devote the tenth slot in my list to a brief summary of several of them. These are in no particular order.

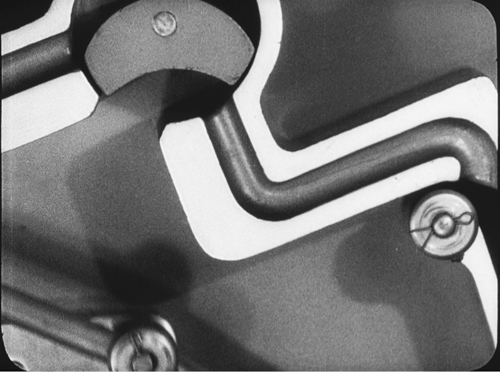

Mechanical Principles was Ralph Steiner’s next film after the better-known H2O (1929). Despite the scientific-sounding name, Mechanical Principles is an abstract film made by shooting close view of moving gears and other devices for moving parts of machines (above). The shapes and movements are engaging in themselves, but there is also, I think, a subtle and amusing progression toward more odd and even absurd-looking mechanisms. I doubt anyone would learn anything about “mechanical principles” from the film. (Included in Flicker Alley’s excellent duel Blu-ray/DVD collection, “Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970.” The visual quality is distinctly better than the versions on YouTube.)

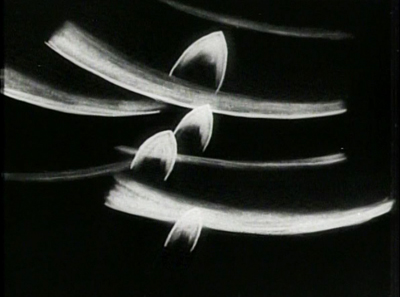

The wonderful German animator Oskar Fischinger specialized in making abstract animation in time to pieces of music. In 1930 he made Studies No. 2 through 7. YouTube contains only snippets of his films; presumably the rights holder, the Center for Visual Music, has diligently patrolled it.) Studies No. 6 and 7 are the most widely seen. I am particularly fond of Study No. 6, to “Los Verderomes fandango,” by Jacinto Guerrero (below). These shorts use a broad range of musical accompaniment. Study No. 7 is done to Brahms’s “Hungarian Dance No. 5.” I haven’t seen all of the Studies, but I assume they all use the same technique, charcoal drawings on paper. There were VHS videotapes released and a laserdisc in 1996, all long out of print. The Center for Visual Music has brought out two DVDs with selections from his films, digitally remastered and with intriguing-sounding supplements.They are sold through the CVM.

The Bridge is a silent film, adapted from the Ambrose Bierce story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” Its director, Charles Vidor (né Karoly Vidor in Hungary, no relation to King Vidor), had come to the US in 1924 and worked as a chorus singer. He managed to self-finance The Bridge, which centers on a man condemned to execution as a spy. As he is being hanged by a military escort on a bridge, we see a complex combination of flashbacks to his childhood and fantasies of escape (below). The film was impressive enough to gain Vidor to gain an MGM contract to direct The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932). The high points of his long career are Cover Girl (1944) and Gilda (1946).

The Bridge is included on the fourth disc in the “Unseen Cinema” collection.

Walther Ruttmann’s Weekend (the original title is in English) is not a exactly a film, even though its subtitle is “Ein Hörfilm von Walter [sic] Ruttmann.” That roughly translates as “a radio-film,” and it was produced by the Reichsrundfunk Gesellschaft (national radio). On the DVD it is reproduced as a black screen with sound over, which one could play in projection. The list of sections given at the beginning runs: “Jazz der Arbeit / Feierabend / Fahrt ins Freie / Pastorale / Wiederbeginn der Arbeit / Jazz der Arbeit” (Jazz of Work / Quitting time / Travel in the Open Air / Pastorale / Recommencing Work / Jazz of Work). The “film” is a lively and often amusing montage of sounds, including trains, tools, engines starting, drum beats, brief snatches of dialogue, a cuckoo clock, a siren, a rooster, and so on. Its twelve-minute length is well gauged to avoid having the device wear out its welcome.

I hardly need to write anything about Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass. For many years Vertov held his high reputation largely on the basis of Man with a Movie Camera, one of last year’s top ten. Enthusiasm was Vertov’s last Ukrainian film and apparently the first Ukrainian sound feature. Although the film’s credits emphasize that it was shot on location, including the interior of a coal mine, clearly nearly all the footage was shot silent and had a “symphony” of sounds woven together and laid over it.

The film has some of the playfulness and experimental cinematography so familiar from Man with a Movie Camera. That film is so engaging in part because it was primarily a lively look at Soviet everyday life, including movie-going. Enthusiasm, however, is far more overtly propagandistic, being largely a celebration of the early achievement of the First Five Year Plan’s coal quota in the Ukraine in four years. This was thanks to the “enthusiasts,” as the film puts it: Stakhanovites, that is, workers who did considerably more than their comrades through hard labor and efficiency. (They were named after Alexei Stakhanov, a coal miner; the movement started in the coal industry.) Some of the Soviet workers and peasants sincerely approached their work in this way, but in reality much of the achievements of the Plan were achieved through forced labor.

The restored film is included on Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray disc, “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and Other Newly Restored Works.”

One of the finest experimental films of 1930 is Lázló Moholy-Nagy’s Ein Lichtspiel: Schwartz Weiss Grau (“A light play [i.e., a film]: Black White Gray”). It is derived from his constructive sculpture, Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne (“Light device for an electric stage”), which consists of many metal elements, some of them pierced with rows of holes, through which lights can be shown to create moving shadows. It later came to be known as the Light-Space Modulator. (The original is in the Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard.)

Moholy-Nagy made a film of the Modulator in action, with shifting solid shapes and shadows. It is sometimes hard to tell whether the camera or the device itself itself is moving.

Unfortunately no high-quality print seems to be available. Facets offers several of Moholy-Nagy’s films on separate DVDs, including Ein Lichtspiel–which is a little odd, given that it is only six and a half minutes long. (The modern soundtrack makes the object seem like a very elaborate set of wind chimes.) This DVD is probably the source of some of the better versions of the film posted on YouTube. It would be a pity to encounter the film in this way, but given the current situation, this is the best of the copies available there.

Kenneth MacPherson was co-founder of the Swiss-based Pool-Group, along with his wife, Bryher (née Annie Winifred Ellerman) and the poet, HD (Hilda Doolittle). Together they started Close-up, an important journal on international art and experimental cinema (1927-33). MacPherson made a few films, most notably the short silent feature Borderline. MacPherson was influenced by French Impressionism and Soviet Montage, and their stylistic traits are used in Borderline, including subjective camerawork and bursts of very rapid editing to convey violence or psychological stress.

The plot deals with racial and sexual tensions in a small Swiss village when a black couple comes to live there. Pete, in a genial performance by Paul Robeson, takes back his fiancée (or wife?) after she has had an affair with a white man, Thorne. Thorne remains obsessed with her, which gradually drives his neurotic, racist wife, Astrid (HD, credited as Helga Doorn) mad. Although Thorne has rented a room over a tavern owned by people sympathetic to the black couple, the scandal leads the villages to demand that Thorne be evicted, and he leaves town.

Some other experimental films made in 1930 that I didn’t think were as good as these but are still worth watching if one is particularly interested in this genre:

Francis Bruguière’s Light Rhythms (on the third disc of the Unseen Cinema set), a more low-budget attempt at something like Ein Lichtspiel, using paper cut-outs.

Luis Buñuel’s L’Âge d’or. (The BFI Blu-ray/DVD combo is out of print, although amazon.com is still selling it. Kino Lorber put out a DVD, which I haven’t seen.) I know this is considered a wonderful film by many, but I dislike it and much prefer Un chien andalou.

James Sibley Watson’s Tomatos Another Day (on Kino International’s “Avant-garde 3” set) is a pretty dreadful film, a sort of “theater of the absurd” before its time. I suspect it is a parody of a modernist play of the day. If so, and if anyone knows what play it was, please message me on Facebook and I’ll add that information. Suffice it to say that the husband, his wife, and her lover say obvious things out loud and very slowly “You are my lover,” “I am alone,” that sort of thing. Then all three start talking in dreadful puns (“Tomotos’ another day”). One might say it’s so bad, it’s good.

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigory Alexandrov co-directed Romance sentimentale, a quite uncharacteristic imitation of French Impression or city symphonies. Finally getting a chance to see it decades ago was one of the great disappointments of my life. It is available as a supplement on the Kino DVD of the restored Qué viva México.

A succinct account of Tobis-Klangfilm’s business operations can be found in Douglas Gomery’s “Tri-Ergon, Tobis-Klangfilm, and the Coming of Sound,” Cinema Journal 16, 1 (August 1976): 51-61. (Available on JSTOR.)

I have summarized the “wooden crosses” motif that is almost universal in anti-war films of the 1920s and 1930s (and occasional later films as well) in my video essay on Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses on The Criterion Channel, where the film is permanently streaming.

Our friend and colleague Vance Kepley published an excellent study, In the Service of the State: The Films of Alexander Dovzhenko (University of Wisconsin Press, 1986).

January 27, 2021: Thanks to Cindy Keefer of the Center for Visual Music for kindly sending some corrections to my discussion of Oskar Fischinger:

All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)