Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

RAINING IN THE MOUNTAIN at UW Cinematheque!

Raining in the Mountain (Hu Jinquan/King Hu, 1979).

DB here:

Thanks to friendly distributors, our University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque has sustained itself with virtual screenings every week. Coming up is one of King Hu’s most marvelous movies, Raining in the Mountain. In tribute, I joined Mike King to talk about it in the Cinematheque’s ongoing podcast series.

Best of all, thanks to Film Movement, you can watch the film through our Cinematheque’s virtual cinema!

For a limited time, the Cinematheque offers a limited number of opportunities to view Raining in the Mountain at home for free. To receive instructions, send an email to info@cinema.wisc.edu and simply include the word RAINING in the subject line. No further message is necessary.

Now, why should you watch it?

Well, it’s one of the most visually splendid Chinese films ever made. The Buddhist monastery that serves as the setting was actually assembled by editing together several South Korean locations, all majestic. Add in the brilliant color design and costumes of vibrant splendor, and you get a spectacle that David Lean would kill for.

Among this pageantry we find a cast of rogues, supple-spined thieves, selfish and lustful monks, and a couple of wise elders who see through the vanities of this world. A splashy finish is provided by a bevy of cascading courtesans wielding dazzling crimson and gold sashes–handy for trussing up a thief who has anger issues.

Key scenes take place in the monastery library, but the filmmakers were forbidden to shoot there. In a weird echo of the movie’s plot, the monk in charge was bribed and the crew stole the shots they needed. The footage was whisked off to Seoul, but the stratagem cost the producers a few days in custody.

The plot, as Mike and I discuss, is really three stories in one. There’s a heist scheme, in which a plutocrat and a general compete to steal a rare scroll. There’s a political intrigue, as monks jockey to succeed the retiring abbot of the monastery. And there’s a redemption arc, centering on an unjustly convicted prisoner who struggles to get on the path of righteousness. Much of the film is an attack on worldly selfishness. Even in the monastery, the monks are obsessed with money and have to be forced to do honest work. It’s a film about who deserves power, and right now, in our America, it’s welcome to see pragmatic humility rewarded.

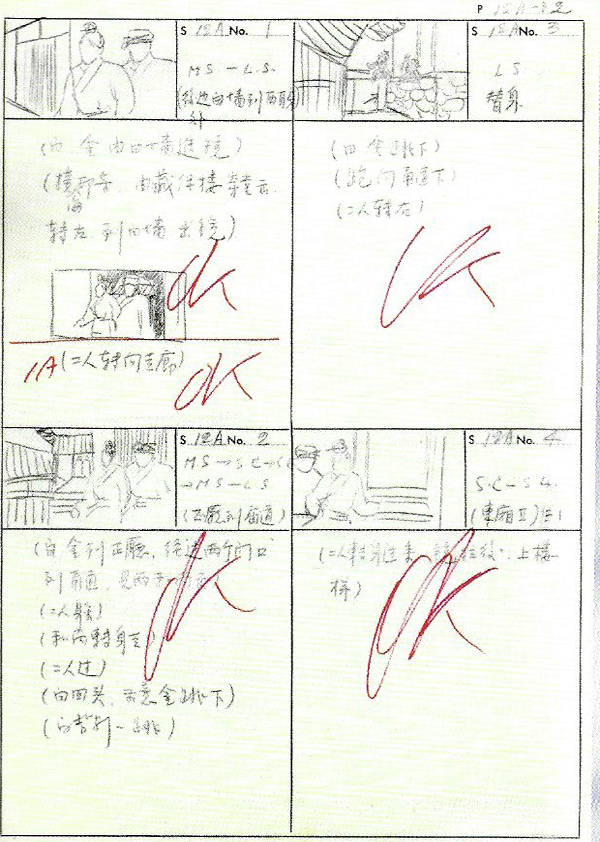

King Hu didn’t finish that many films. He took months to research his projects, and his meticulous planning of costumes and sets made him a slow worker. Unlike many Hong Kong directors, he prepared storyboards and worked out his compositions carefully. As he completed his shots, he checked them off with an “OK,” like the American filmmakers of the silent era.

The connection isn’t accidental. Like a silent filmmaker, Hu had a pictorial intelligence that conceived scenes shot by shot, without the pointless flourishes (arcing camera, slow track-ins) that today’s filmmakers are addicted to. He’s a fast cutter, but his locked-down compositions give you time to see everything.

As a result, Raining in the Mountain is not your typical martial-arts movie. For one thing, what usually counts as action–an aggressive fight, involving punches and kicks–doesn’t come along for an hour. In our conversation, I argue that King Hu replaces fights with zigzag chases, evasions, and hide-and-seek maneuvers. The geography of the monastery gave him vast opportunities for booby-trapped compositions. Figures and faces pop in and out of doorways, corridors, and windows.

The film is designed for the big screen, where details can blossom in distant crannies. So on a monitor (forget the tablet, the laptop, and the phone), you have keep your eyes peeled. While the two thieves drop into a passageway and race into the distance. . .

…a peekaboo framing gradually reveals why they’re hiding: a monk in blue emerges (tiny) in the ledge above them,

The spaciousness of the setting seems to have nudged Hu to try leading our attention to tiny bits of action in the anamorphic frame. Watch how he stages Chang’s preparation for a knife attack in a long shot. Gold Lock is crouching on the left, watching, like us, for the glint of Chang’s blade.

No close-ups are necessary. Hu trusts that we’ll keep up.

As usual in King Hu, there’s a quiet jubilation in watching the calm confidence of fighters leaping from room to room, hopping into a niche, or backflipping under a porch. Hu favors a slow buildup, capped by percussive bursts of action in rhythms recalling Beijing Opera. He cares less about traditional martial arts than about finding ways to create uniquely kinetic dramas of honor, heroism, and protection of the innocent. For him, combat is a staccato dance, and conflict is a test of moral rectitude.

As Mike points out in our conversation, King Hu looms ever larger in film history. A firm line runs from A Touch of Zen to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Hero (2002), and on to Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003). Tsui Hark’s swordplay films, especially The Blade (1995), owe a great deal to King Hu. (Not to mention John Zorn’s ear-bleeding album dedicated to the director and his incandescent female star Xu Feng.) King Hu remains one of the most original and engaging filmmakers in world cinema.

Film Movement’s site provides a trailer for Raining in the Mountain.

Thanks to Mike King and Ben Reiser for arranging the podcast, and Jim Healy and Pauline Lampert for coordinating so many superb programs under difficult conditions.

A Touch of Zen (1971-1972), which took three years to make, is King Hu’s official classic, and it displays many of his virtues. It’s now easy to see. (There’s a splendid Criterion disc, and it streams on Criterion and on Amazon Prime.) But don’t neglect his breakthrough Come Drink with Me (1966) and his other “inn films,” Dragon Inn (1968; also Criterion Channel ) and The Fate of Lee Khan (1973; streaming here). Perhaps his most dazzling experiment in action cinema is The Valiant Ones (1975), but I don’t know of any good copies on disc or elsewhere. I’m less enamored of Legend of the Mountain (1975), a ghost story, and All the King’s Men (1982), a tale of court intrigue, but it’s possible I’d like them more if I saw them now.

For more on King Hu, precious documents, essays, and recollections are available in Transcending the Times: King Hu and Eileen Chang (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1998) and King Hu: The Renaissance Man (Taipei: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012). The storyboards above come from the Hong Kong volume. I recommend Steven Teo’s deeply informed books on Chinese film, particularly Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition, and his monograph King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. Hubert Niogret’s fine biographical study of King Hu is on the Criterion Channel.

I discuss King Hu’s work in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema, and in other entries on this site. In the podcast with Mike, I mention Hu’s ingenious method of making swordfighters disappear and reappear; this entry explains how he does it and includes a clip.

Raining in the Mountain (1979).

When John was Jack: Ford’s early westerns rescued

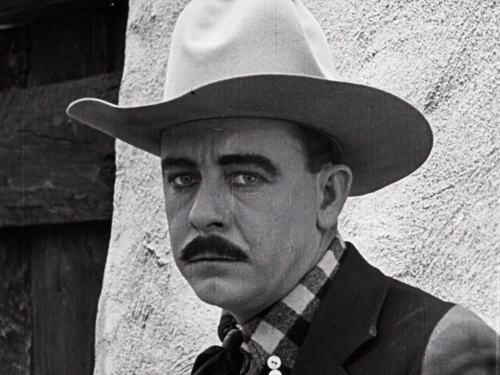

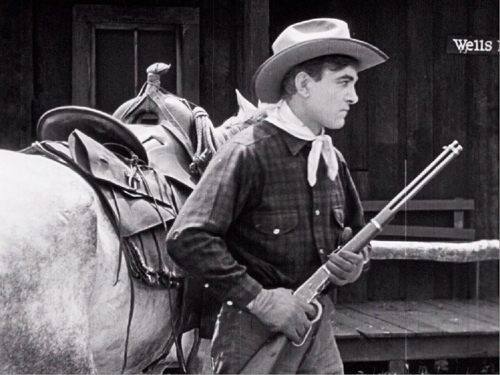

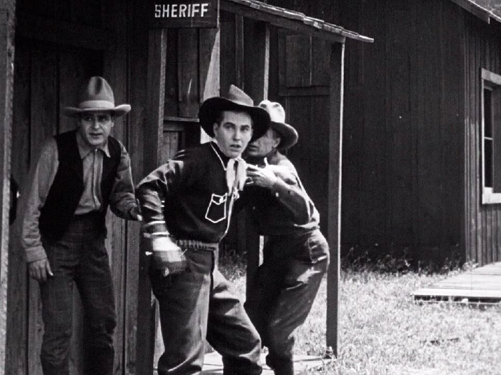

Straight Shooting (1917).

Kristin here–

Recently I received a most welcome message from cinephile extraordinaire Michael Campi, whom David first met at the 1995 Hong Kong Film Festival and with whom we have shared many a meal at subsequent festivals on three continents. His smiling face has shown up often across the history of this blog, most recently here. Michael was alerting me to the existence of a Blu-ray edition of John (aka Jack) Ford’s Hell Bent (1918). Kino Lorber released it on August 25, and as I discovered upon investigation, it had released a Blu-ray of Straight Shooting (1917) on July 14. A third feature, Bucking Broadway (1917) also survives, albeit in somewhat truncated form. (See below.)

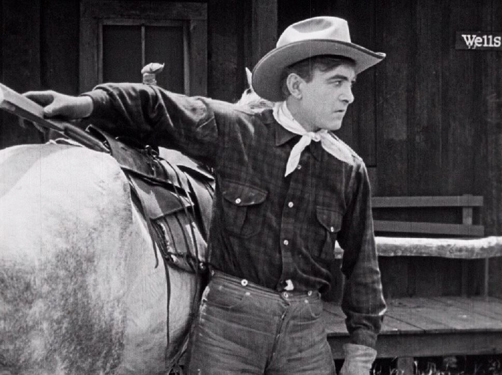

Jack Ford, as he signed his films up to 1923, had made five two-reel westerns in 1917 before his first feature, Straight Shooting, followed by three other features that year. Harry Carey’s character, Cheyenne Harry, was popular, and Universal was clearly happy to have Ford crank out five-reelers starring Carey. (Stories of how Ford supposedly tricked Universal into “letting” him make a feature strike me as having been concocted well after the fact.) Cheyenne Harry was Carey’s main persona, but these features were not a series or serial. Carey is a different Harry each time, winning and marrying different women. When he departed from his good-bad man character, he took a different name, as with upstanding cowboy Buck in Bucking Broadway.

Even across these three films, the plots seem fairly formulaic, but the execution already displays considerable stylistic and technical sophistication. Ford had already mastered the continuity guidelines that had gelled over the previous years. Most of his films were shot in direct or diffused daylight, but he knew how to create an effective chiaroscuro with artificial light when a scene called for it. He often staged in depth to a degree that was unusual in that period. Particularly in Hell Bent he creates flashy scenes to show off his mastery of the cinema.

Both films survived only at the Národní filmovy archiv in the Czech Republic. (Go here for a remarkable list of major international classic films which have survived only because there were unique prints of them in this archive.) That chance survival is very lucky for us. Ford is credited with making 32 films from 1917 to 1919 (fifteen in 1919 alone, though some were shorts). Only three survive in anything close to complete form, and a few brief scraps have come down to us as well. These new releases and an earlier one make all three available in the best prints out there.

Straight Shooting

Straight Shooting is the earliest and arguably the best of the three. Its story is tight and develops continually, without the padding noticeable in Hell Bent and Bucking Broadway. The plot of the ranchers trying to drive out the settlers runs through it consistently and holds it tightly together. Straight Shooting also sets the pattern of making a romance line of action prominent in the plot. In both Straight Shooting and Hell Bent Harry begins as a criminal and reforms when he falls for the virtuous heroine. In Bucking Broadway, another common pattern is used. As a cowhand on a ranch, Harry woos and wins the hand of the rancher’s daughter, only to lose her to a slick visitor from the city who persuades her to elope with him to New York. Naturally he turns out to be a scoundrel, and she needs rescuing to return to the little house Harry has built for his bride.

To some extent, these patterns are taking up conventions of William S. Hart’s films, though Harry is a more easygoing, comic character than the solemn, stalwart heroes Hart tended to play.

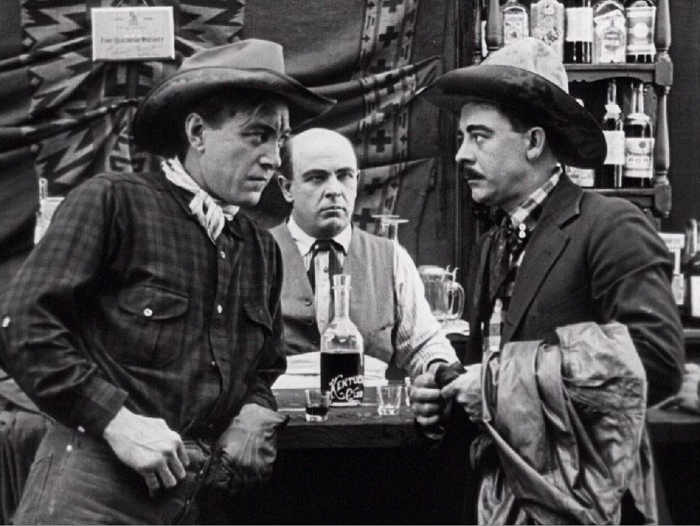

Already Ford displays his remarkable mastery of the medium. The famous shoot-out scene is handled with an unusual panache. After Harry comes out of a building and sees Fremont riding toward him, he unsheathes his rifle. A reverse shot shows Fremont dismounting and doing the same.

In the same shot, Fremont moves forward, leading to a tighter reverse shot of Harry, waiting.

A tighter reverse shot of Fremont follows, leading to a repetition of the original framing as Harry moves rightward.

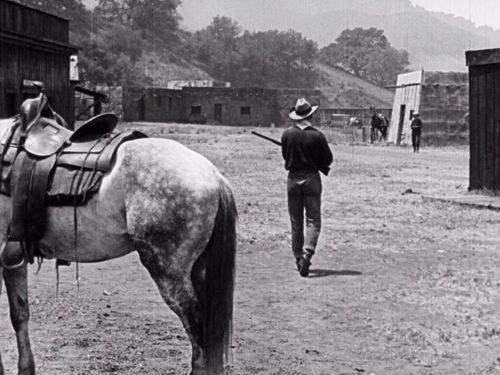

The original framing of Fremont is repeated as he responds by moving leftward. A long-shot in depth (emphasized by the placement of the horse in the foreground, shows the two men in the same space, establishing the distance between the two but also setting up the building on the far right that Fremont will duck behind, leading to a cat-and-mouse game that forms the last part of the shoot-out.

A tighter shot-reserve shot places the two men in irises. Harry moves toward the camera.

Fremont moves forward as well and comes even closer to the camera than Harry does; the camera also lingers on his face longer than on Harry’s. These close views of Fremont place considerable emphasis on his fearful expression in comparison with Harry’s determination. This fear sets up the moment when Fremont ducks behind the building.

A cutaway to some onlookers ducking into the alley at the rear builds suspense but also shows that the sheriff is too scared to interfere (as he had been in an earlier scene in the bar).

In the repeated depth framing, the two men walk slowly toward each other. More cutaways show frightened townspeople ducking into hiding. Harry and Fremont walk past each other without firing , which adds an unconventional little twist to the scene, and Fremont suddenly hides behind the building.

Although a high point, the shoot-out is not the only indication that Ford was born to make movies.

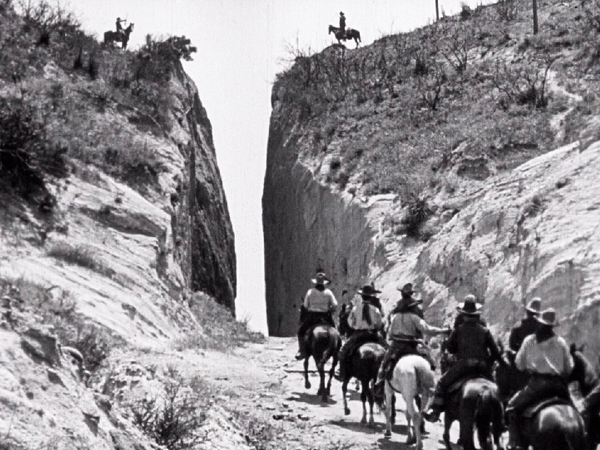

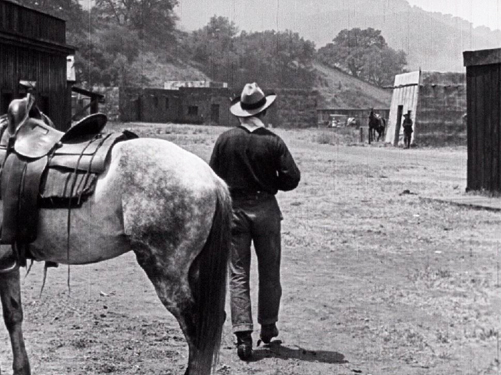

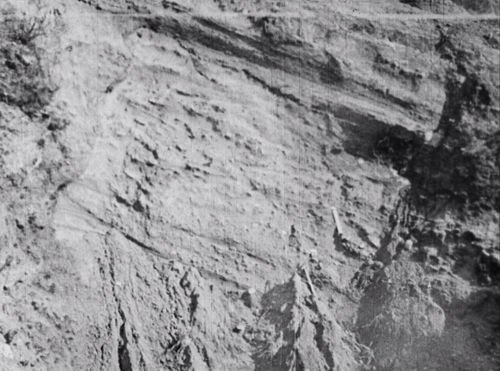

His use of natural locations was distinctive from the start. He may have already been using Beale’s Cut, the narrow passage in the frame at the top of this section, in his short films. (Other filmmakers, such as Keaton, shot there as well. Tag Gallagher’s video essay on the disc runs through a few of them.) This formation appears relatively briefly in Straight Shooting, but Ford used it more extensively in Hell Bent. It may have been the Monument Valley of Ford’s early career.

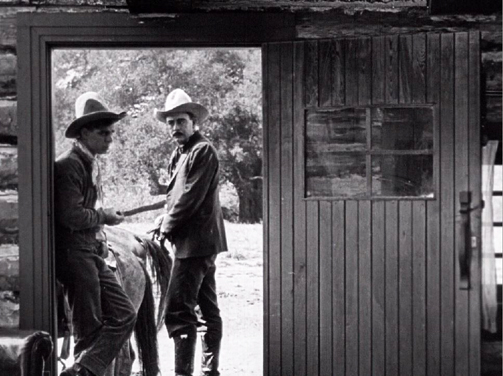

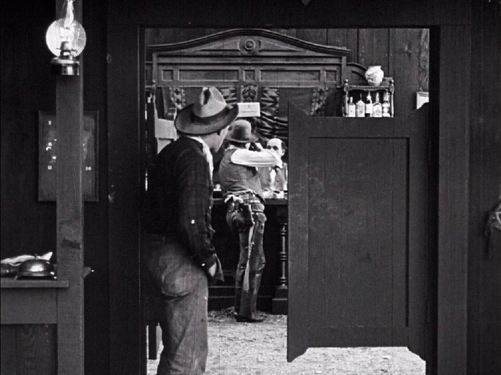

His penchant for doorways has appeared by this early point. On the left, the young cowboy Danny and Fremont pass in the door of the villainous rancher Flint’s house. On the right, the bar doorway is combined with considerable depth as Harry arrives to announce that he is quitting the gang.

Depth is used in natural settings as well. The ranchers’ attack on the farmhouse includes a dramatic composition with horsemen shown in near silhouette against the distant house, visible through a cloud of gunsmoke and dust. At the right, the staging of a meeting in which Flint discusses strategy with his henchmen has the furniture in the foreground, with the placement of the sofa forcing two of the men to face away from the viewer, creating a naturalistic touch. By the way, compare the diffused lighting and set design, with its ceiling beam, with a nighttime scene at the villain’s lair in Hell Bent, below.

Most Ford fans are probably familiar with Straight Shooting, albeit in inferior prints. Before I pass on to the lesser-known Hell Bent, some information about the Kino Lorber version.

According to Tag Gallagher’s essay in the accompanying booklet, the Nederlands Filmmuseum used a copy of the Czech print to create a tinted version. The Museum of Modern Art also made a version from the Czech print; its head title and credits copy the design of Universal intertitles of the period. That print, presumably the one I saw years ago, translated the Czech titles. The Kino Lorber print is a 2016 restoration by Universal, which adopts the MoMA credits but uses title text drawn from an early continuity script of the film. I must agree with Gallagher that the decisions to use those titles and not to tint the print were correct. As the image at the top of this entry shows, the result is a huge improvement on previously available versions.

Apart from this booklet, the supplements also include a brief video essay on Ford’s early career by Gallagher, an audio commentary by Ford scholar Joseph McBride, and a three-minute fragment of Hitchin’ Posts, which is all that is known to survive of Ford’s 1920 film.

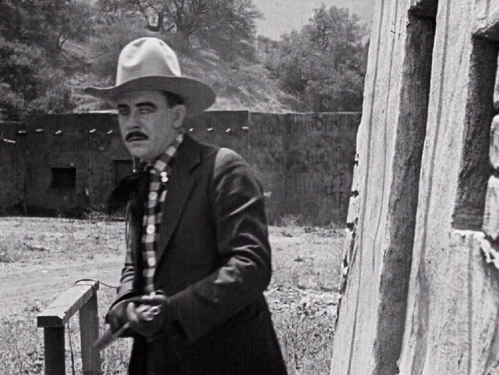

Hell Bent

We first saw Hell Bent when it was screened at “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival in 1988. Although the surviving Czech print was missing over twenty minutes of footage (near the beginning and especially the ending as far as I could tell), it was another impressive revelation of Ford’s very early work. It was also quite worn, more than Straight Shooting, it would seem, since even a comparable restoration by Universal could not quite replicate the visual quality of the Straight Shooting Blu-ray. Still, it is again a big improvement.

The plot of Hell Bent is considerably less well constructed than that of Straight Shooting. Early in the film there is an impressive stagecoach robbery sequence that sets up the criminal gang, led by Beau Ross, that Harry is initially linked to as a sometime hit-man. The robbery in fact fails, as the expected Wells Fargo cash-box has been secretly sent by by wagon taking a different route. Nothing comes of that immediately.

The opening of the robbery scene displays Ford’s expertise in both editing and dramatic cinematography. The scene begins with the gang high on a hill looking off expectantly. A POV long shot reveals a stagecoach passing below.

The group turn and begin to ride off left. There follows an extreme long shot of a winding road with the stage moving up the lower part of the road.

We see the bandits riding rapidly down a steep slope. Finally the stagecoach is seen in the same framing as before, now further along, and moments later the gang appear at the upper right around the bend, galloping to intercept the coach.

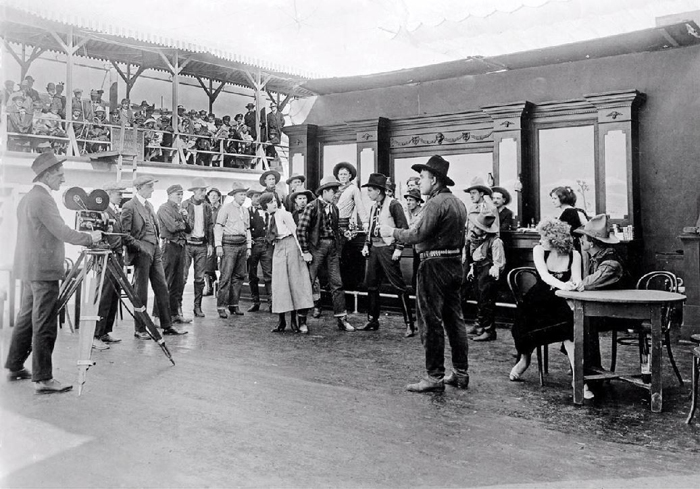

After the failure of the robbery, there is little plot development in the first half of the film. There’s a long comic scene as Harry arrives in town and finds all the beds in the local saloon/dance hall occupied. He rides his horse up to the room with a single occupant who has refused to share his bed. Harry demands that he do so, and the two take turns forcing each other to jump from the window until they end up drinking together and becoming chums. (The bar here may well be the same set as that in Straight Shooting redressed. Bars apparently played a large role in Ford’s films, not only in these scenes but also in the production still at the bottom of this entry.) Teaming up with another cowboy gains Harry an ally in later in the action, but their initial encounter is quite drawn out.

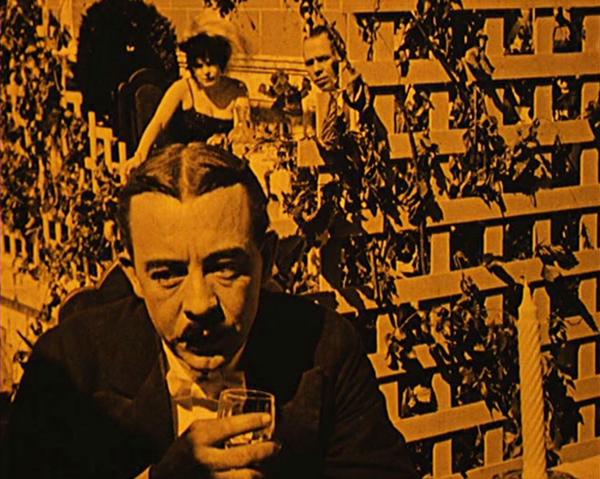

As in Straight Shooting, Harry falls in love and reforms. (We witness the process of him contemplating the benefits of a settled domestic life in the close-up at the top of this section.) The second half becomes more goal-driven, with Harry leading the effort to defeat Ross’s gang.

There is no sustained action that is as flashy as the gunfight in Straight Shooting. Still, Ford seems even more determined to flaunt his prowess as a director. He gives us our first view of our hero as a reflection in a pond. He shows horsemen as shadows in a shot that prefigures a similar device in the Indian attack in The Iron Horse (1924).

The beginning of the climactic attack on the stagecoach begins with Ross signaling to his men on distant hilltops to converge. This is handled with excellent graphic matches of Ross, his henchman, and back to Ross. A short time before, as the gang rides out of town, they are filmed so that the horses gallop toward and jump over the camera.

Most of the interiors were shot on stages at Universal with muslin diffusers draped overhead to create an even, overall light. The image at the bottom of today’s entry shows this setup for another Harry Carey film by Ford. Incidentally, it also shows an audience watching the filming. Ford again creates chiaroscuro, this time more elaborately, for Ross’s house. There is a ceiling of log beams with something over them to block out the light. The distant room is lit more brightly than the foreground one, which is lit only by a fire (presumably simulated with one or more arcs) in the left foreground. For some of the more static exteriors, Ford has the camera shooting obliquely toward the sun, creating considerable modeling on the characters.

Although, as I said, there is no big final scene, there is a jaw-dropping shot during the gang’s pursuit of the stagecoach in the climactic sequence that demonstrates how thoroughly Ford had already grasped the powers of mise-en-scene and the camera. Although the scenery looks quite different from that of the high-angle extreme-long shot of the winding road earlier, I’m fairly sure that this is the same road, shot from a different vantage point, more or less where the gang had been waiting in the earlier scene. If not, it is certainly somewhere similar nearby, with a hairpin road on the side of a mountain.

The stage initially comes forward from the distance at the upper left (the area where the gang had come from when they appeared in the final shot of the sequence reproduced above). As the horses round the curve and race down toward the right, the coach breaks lose and begins to fall over the edge.

The camera tilts to follow it, but after it falls out of sight at the bottom, the tilting movement pauses, not continuing with it until it crashes offscreen.

After this pause, the tilt resumes, revealing the crushed coach at the bottom of the cliff. The reason for the pause in the tilt becomes apparent: offscreen the horses have rounded a bend and now come unexpectedly racing through the shot, past the coach. The camera had paused, waiting for the timing to be just right to catch them. I believe that someone who could figure out the logistics of that action and that camera movement had a pretty good feeling for cinema from very early on.

In addition to this dramatic mountain road, Ford uses Beale’s Cut in multiple scenes, making it the location of the gang’s hide-out.

Hell Bent was also restored by Universal from the Czech print. There’s no booklet with this one, but Gallagher again provides a second, different brief video essay. The other supplements consist of another commentary by Joseph McBride, as well as a 1970 interview he did with Ford.

Bucking Broadway

Watching the two Kino Lorber releases, I was reminded that a third Ford feature of this era also survives–though, like Hell Bent, it is missing footage, probably about the same amount, given the running lengths. Bucking Broadway was one of eight features by Ford released in 1918. His ninth feature, it also stars Harry Carey, this time as Buck. The plot is thin, with Harry as a cowhand who falls for the rancher’s daughter and is given his blessing to marry her. She elopes with a man from the city, who does intend to marry her but turns out to be a drunkard and lout. Harry and his cowboy friends come to New York and rescue her.

Even more than Hell Bent, the film seems like a two-reeler stretched to five. Harry’s engagement party involves a comically maudlin scene the cowboys picking out “Home, Sweet Home” on a piano and bursting into tears as they sing along. The final rescue and fight are expanded to create some comedy about cowboys riding their horses through the city, and the final brawl seems barely staged and way too long.

Nevertheless, there are flashes of Ford’s skill at intervals, with his door motif recurring as a site for the rancher to mourn his daughter’s departure and a scene by a fireplace using the stark low-key lighting popularized by The Cheat three years before.

There are plenty of depth shots like this one, as the cowboy in the foreground calls the others to gather and we see three of them in the distance. See the top of this section for an unusually flashy depth shot as two friends of Buck watch the villain getting drunk in the close foreground.

There are none of the virtuoso treatments of editing, landscape, and camera movement that characterize the other two films of this era, but any Ford completist will want it. After all, it comes as a supplement to The Criterion Collection’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of Stagecoach. It includes a charming musical accompaniment by Donald Sosin, whose piano and violin playing (often simultaneously!) has enlivened many an Il Cinema Ritrovato screening.

The photograph below was borrowed from Tag Gallagher’s video-essay supplement on the Hell Bent disc.

Beale’s Cut is not a natural formation. As the name suggests, it is a man-made passageway created in the 1850s and 1860s as a convenient route into and out of nearby Santa Clarita (just north of the San Fernando Valley). It still exists, though comments on Google Maps suggest that, being located on land belonging to an oil finery, it is fenced off, partially collapsed, and full of trash. For a brief account of its sad decline, see here. There are many historical photos of it online.

Shooting an unidentified Ford-Carey movie at Universal City’s stages.

1917 and DUNKIRK: A conversation

1917 (2019).

DB here:

For over twenty years, the Willson Center for Humanities and Arts at the University of Georgia at Athens has hosted Cinema Roundtable, a series of film screenings and discussions. Covid-19 hasn’t stopped them from keeping it going, and they kindly invited Kristin and me to visit, virtually, and talk about two war films. The title is “Wartime Suspense in ‘Dunkirk’ and ‘1917’: A Conversation with Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell.”

We discussed aspects of style and genre. Many participants, notably Professor Tanine Allison of Emory, brought up other points about these two intriguing movies. It was also nice to see some old friends from Wisconsin logging in.

The entire session is on YouTube.

We enjoyed participating and thank our hosts, Dick Neupert and Dave Marr. In preparing for the session, I think it’s fair to say we liked both films better on rewatching them.

And no, we haven’t yet seen Tenet. Health precautions keep us at a distance. But we are keen, and when we can write about it, we will.

In a piece of good timing, Tom Shone’s book The Nolan Variations came out three days before our session. It’s excellent and offers the most comprehensive overview of this director’s achievements.

Our e-book on Christopher Nolan is available for download here. (Thanks to those Willson attenders who picked it up!) There’s some background on the book here. Our various blog entries on Nolan’s work are here.

Dunkirk (2017).