Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Vancouver: “It’s the Arts”

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Kristin here:

I wonder how many of my readers will recognize the source of this entry’s title. Is Monty Python’s Flying Circus still the perennial classic it was among young people for decades after its original series was broadcast? That brief sentence was the title of the sixth episode of the first season, shown in 1969, though I didn’t see it until some years later. The episode itself has little to do with the arts, but for some reason that particular title stuck with David and me, as few if any others did. Whenever we have encountered a TV program or a review, often something pretentious, one of us will turn to the other, or both simultaneously, and say, “It’s the Arts!”

The Vancouver International Film Festival has an admirable custom of showing many documentaries. They often deal with ecological issues and Canadian subject matter. One prominent thread, however, is documentaries about the arts. These are known as MAD, or “Music, Art and Design.” Although, as I mentioned in my previous entry, I tend to stick to the Panorama program of international fiction films, I always try to attend a few of these arts documentaries when they fit in with my interests. Most of these are in fact wonderful, not pretentious. Still, I am too accustomed to the phrase, and I think automatically, “It’s the Arts.”

Paris Calligrammes (2019)

One documentary that I was keen to see is Ulrike Ottinger’s autobiographical account of her years living in Paris during the 1960s. Ottinger is known, at least in the US, primarily for her experimental fiction films, like Freak Orlando (1981) and Joan of Arc of Mongolia (1989). I had not encountered her work since then and was eager to catch up with her at this year’s festival.

Ottinger did what many young people think of doing but never carry through on. She left home at the tender age of twenty for an exciting new life. In 1962, she moved from Germany to Paris, where she lived until 1969 before returning to West Germany. In France she lived among Bohemians and stayed long enough to witness the protests of May, 1968.

Naturally she was hugely influenced by her experiences. She tells of encountering artists and ideas: “In my euphoria, I wanted to convert all my experiences directly into art.” But how? Early on, she muses on how to convey those experiences of decades ago:

I ask myself that same question over fifty years later. How can I make a film from the perspective of a very young artist I remember, with the experience of the older artist I am today? In Paris, I followed in the footsteps of my heroines and heroes. Wherever I found them, they will appear in this film.

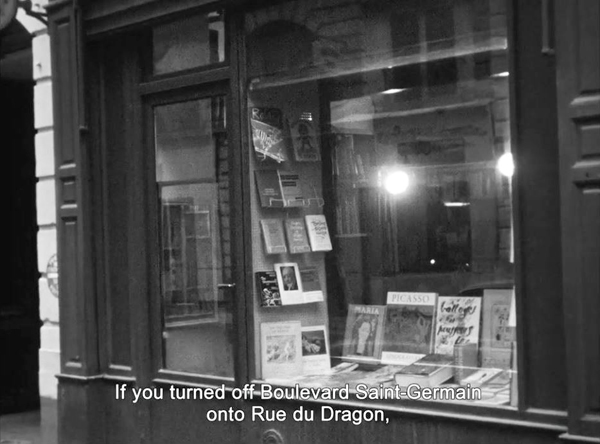

There is no footage of Ottinger from this period, and relatively few relevant photographs. Instead she wisely organizes the early portions of the film around her connection to an extraordinary bookshop that was a center of artistic and intellectual life at the time: Calligrammes (above), founded in 1951 by Fritz Picard, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. As a dealer in rare German and other books on the arts, Picard became host to innumerable avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Ottinger recalls buying many books on the German Expressionists and other avant-garde artists and movements of earlier decades.

(David bought some books for his dissertation on French Impressionist cinema at Calligrammes in the summer of 1973. Picard died in November of that year, though the shop was continued for a time by others.)

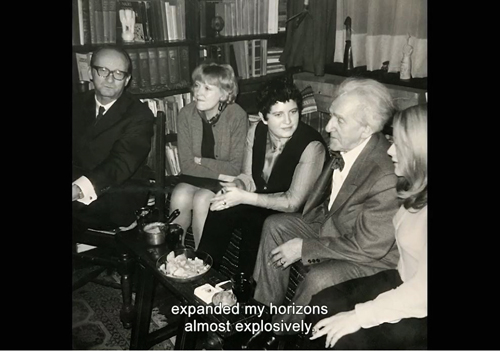

Ottinger became a friend of Picard and socialized with the patrons and visitors of the shop. Below, she’s in the black vest, sitting beside Picard at a party. She also was indirectly influenced by the great artists of the past, such as Hans Richter, who had frequented Calligrammes. In one sequence she flips through the guest-book signed by many a famous visitor, and we see clips from films like Ghosts before Breakfast, which influenced her.

Following this section, Ottinger gives us sequences on the effects of the Algierian war on her friends in Paris and describes the protests of May, 1968, some of which she was able to see from her apartment near the Sorbonne.

Perhaps inevitably, Paris Calligrammes reminded me of some of the Agnès Varda’s late autobiographical work. Ottinger is less lyrical and personal, as well as being more overtly political. There is more of a sense of name-dropping, at least in the early section. Still, who wouldn’t be interested in hearing about the early life of someone who has had such adventures? Ottinger also describes the influences on her by the artists she learned about and met. The brief clips from her own films should inspire a new generation of film buffs to seek out her work.

Like so many of the films at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, Paris Calligrammes was shown in Berlin. For an enthusiastic and informative review done at the time, see Richard Brody’s piece in The New Yorker.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

I am of two minds about Matthew Taylor’s documentary on Duchamp. It presents an excellent overview of the artist’s career and work, and one could learn a great deal from it. It makes clear, for example, the relationship between Duchamp’s early ready-mades and the fact that they were mostly subsequently lost and much later replaced by replicas–all with the artist’s cooperation. It puts his important early painting “Nude Descending a Staircase” (see bottom) in its historical context.

There are the usual experts explaining Duchamp’s intellectual approach to his artworks and his considerable influence on subsequent generations. We are not given much indication concerning who some of these experts are. The identifying labels often just say “Curator” or “Art historian” without linking the experts to any institution or publication. I tried looking one of them up on the internet and couldn’t find him. I’m sure, however, that they know Duchamp’s life and work well.

These experts are also almost all extremely enthusiastic about Duchamp’s work and especially the impact he has had upon art–not, as they emphasize, just specific trends but absolutely all subsequent art up to the present. Early on in the film, before we have been introduced to most of the talking heads, a voiceover declares, “Without him, imagine where we would be. We’d be painting in the style of Matisse or Picasso. That’s what modern art would be without Duchamp.”

(Ironic note: Duchamp’s stepson, Paul Matisse, is the grandson of Henri Matisse.)

That’s a pretty remarkable claim. It’s hard to think of a period that long in the post-Medieval era when art has just frozen in place for a century. Surely innovative styles and individual artists would have come along and produced distinctive work that did not depend on Duchamp’s main claim to fame, his demonstration that anything could become an artwork if we regard it as such. Did the Soviet Constructivists depend on Duchamp’s idea? Did the German Expressionists? Do highly individualistic artists? (See the section below.) Do manga and graphic novels, which are coming to be thought of as worthy of attention as art–not just because someone found them and declared them so, but because they contains qualities that were considered artistic well before Duchamp?

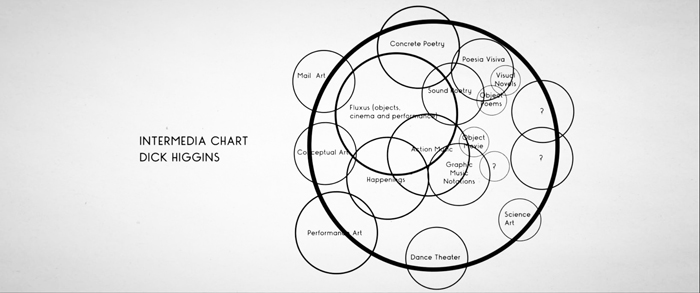

To be sure, Duchamp did have a huge impact, as this chart, shown in the film, suggests. It was devised by Dick Higgins, artist and co-founder of Fluxus. (The absence of Pop Art among the circles is rather puzzling, though it does figure in the film.) One could, however, devise many other circles for trends and institutions that do not reflect that impact.

Toward the end of the film, the experts go further, suggesting that Duchamp encourages the democratization of art by suggesting that anyone can be an artist, whether on their own or by taking and re-purposing existing artworks or objects or sounds. Yet would we say that the many outsider artists of the past century who have come to the recent attention of taste-makers had anything to do with Duchamp? And fanart, if that is included in this vast generalization, existed before Duchamp.

Despite the obvious excitement the experts display in extolling Duchamp’s work, someone watching the film might be less sympathetic, given the debatable state into which Postmodernism in general has led the art world. As one inevitably thinks, what’s next, Post-Postmodernism?

Duchamp himself seems, according to the film, to have had considerably less enthusiasm about his own artworks, preferring perhaps the idea of them rather than the execution. He took twelve years to complete the Great Glass and declared himself pleased with the results when an accident severely cracked its surface. He did not bother to keep track of his ready-mades, most of which disappeared. One wonders why he bothered to follow the initial venture into that area with “Fountain” (a urinal signed “R. Mutt 1911”), since subsequent ready-mades like “Hat Rack” (above) make the same intellectual point.

Late in life Duchamp seemingly gave up art-making to devote himself to competitive chess. After his death it turned out that from 1946 to 1966 he had been working on “Étant donnés,” a peep-show view of a spreadeagled nude woman, based on his mistress during part of that time. Despite the raptures expressed by the experts, it looks like it could be considered revenge porn. But only, presumably, if one calls it that.

Only one of the experts, Peter Goulds, departs from the general unquestioning idolization of Duchamp. Near the end he says,

Later in life, of course, he must have found it incredibly amusing to hear people latch onto his theories as though they were universal truths, when actually his whole life was about bucking those very conventions and defying them. So I’d like to suggest that his form of so-called conceptual art was a much more playful exchange. I’m not so sure about how even serious he was about it himself. Here he throws these things out as suggestions, with thought. Others, perhaps more needy than himself, would make these rules be therefore solely applicable.

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Frida Kahlo is one of those artists who don’t appear to owe much, if anything to the influence of Marcel Duchamp. As the film makes clear from the start, she was aware of European artistic movements and developments. Still, neither she nor her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, seem to have absorbed much from them. Kahlo always denied that her later work was Surrealistic, and one might rather attribute its fantastical elements derive more from the Latin American tradition of Magical Realism.

Indeed, the whole idea that Duchamp influenced all of modern art comes to seem remarkably Amero- and Euro-centric if one considers that it implicitly either scoops highly individual artists like Kahlo up into one enormous category or eliminates them from that category altogether.

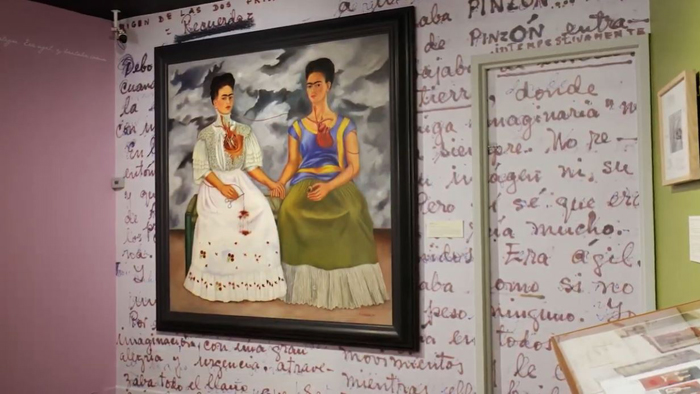

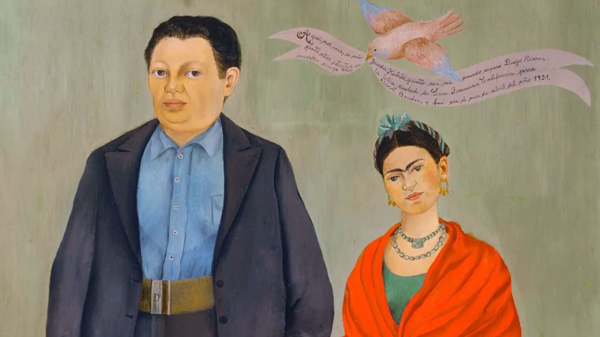

I found Frida Kahlo more satisfying than Marcel Duchamp. Its experts are all clearly identified as to their position and institution. Some are curators of the institutions which own her works, such as the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. There “The Two Fridas” is shown (see top) as the curator discusses it.

These experts are as enthusiastic about their subject as those in the Duchamp film, but they are focused entirely on recounting Kahlo’s life, her social context, and the influences on and changes in her style across her life. For example the simple presentation of “Frida and Diego Rivera,” an early portrait done shortly after their marriage, gives way to the more sophisticated and symbolic “The Two Fridas.”

Archival photographs and film clips illustrate the eras of the places where Kahlo lived and traveled. The impact of the lingering effects of her injuries in an extremely serious traffic accident in her youth, her travels with Rivera in the US, and the rockiness of their marriage are all discussed to help clarify the often cryptic visual references in her paintings.

In short, Frida Kahlo is a model of a staightforward and informative documentary on an artist. I was pleased to be introduced by it to its producers, Exhibition on Screen. In business since 2011, it has made twenty-six such documentaries. These are shown in theaters and festivals initially, before being made available on disc and streaming on their website. Frida Kahlo is promised for streaming on October 20.

Once again, thanks, as usual to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

Vancouver: Stories, spliced and stacked

Sarita (2019).

DB here:

Humans love stories, the more the better. As a result, many storytellers find ways to bring distinct story lines together. The most common way is to link them, through subplots involving major and minor characters. Viktor Shklovsky urged us to think of folktales, novels, and plays as “braided” out of several story lines. At other times, the stories are bracketed within a bigger plot. A character tells others about incidents in childhood, or characters tell completely detachable tales, as Scheherazade and Chaucer’s pilgrims do. Instead of braiding, we get embedding within a frame situation.

I started to think again about these options watching four films at the always exhilarating Vancouver International Film Festival. All were engaging, partly because they often mixed comedy and drama in rewarding ways. They also offer a nice menu of creative possibilities, exploited by ambitious filmmakers.

Screen life

An omnibus film can offer a frame story, as the British classic Dead of Night does, but most modern ones simply line up one tale after another, in blocks. Essentially these are short stories, and they tend to follow literary patterns.

One option is the “snapper,” the plot consisting of twists and a sting in the tail, a surprise ending. Edgar Allan Poe may have invented this format, O. Henry canonized it, and Roald Dahl gave it a grisly tenor. Diverting examples of the surprise-ending story can be found in the omnibus Spanish film Tales of the Lockdown (2020).

All five modules are comic, though sometimes in a macabre vein. Produced during the COVID-19 lockdown, somehow staged and shot remotely, each episode is cleverly scripted and elegantly directed. In one, a reclusive Milquetoast is pressed by an aggressive neighbor who wants to sell him a plan to expunge “bad vibrations” from his apartment. The Feng Shui saleslady gets more than she bargained for when she learns the source of those vibes.

In another, an aspiring hitman recruited by The Agency gets a remote tutorial from an experienced killer, who makes him practice techniques on a teddy bear and the dogs he snags from the neighborhood. A third, gentler episode is still tricky: we’re led to presume some things about a couple that turn out to be not valid–at least, not until the end. Sorry to be so elliptical, but films like this oblige you to avoid spoilers.

The most straightforward comedy concerns a woman auditioning by video for a TV part, aided by her husband who decides he could get a role as well. For a local audience, the fact that she is played by star Sara Sálamo and her actual husband, a Real Madrid football player, doubtless adds to the fun. The last episode, a black comedy, presents a rich couple’s extreme reaction to a tenant strike in one of their buildings.

The filmmakers have found many nifty ways to exploit the limited viewpoint enforced by lockdown. Naturally, remote conversations take place over laptops, which motivates minimal change of setting and little need for elaborate action scenes, or even ordinary staging in interiors. Offscreen action is likewise conveyed minimally, just by speech or noise in the world outside. The funniest moments in the fifth episode concern the rich couple learning they’ve received a “package” which we never see and must assume is problematic, since the thug on speakerphone says it’s “middle-aged.”

Confined settings have in effect created five “chamber plays” of the kind I’ve talked about before. This constraint allows directors to design and dress settings and find playful compositions to accentuate the plot twists that keep us glued to the screen.

In all, Tales of the Lockdown is a display of light and lively cinema craftsmanship. It’s heartening to see creative energy maintained in pandemic conditions. It premiered on Spanish Amazon Prime and would be worth looking for on that platform in other markets.

Food, memories, and the future

The major alternative to the twisty snapper tale is the “slice of life,” the muted drama of a situation that may change little or not at all. Here the emphasis falls on characters–their relations, their reactions, and their sensitivity to one another. The classic examples come from Chekhov and from Joyce’s Dubliners, but they’re also prevalent in what used to be thought of as the classic New Yorker short story of John Cheever or J. D. Salinger.

Pensive incompleteness of this sort well suits the Hong Kong film Memories to Choke on, Drinks to Wash Them Down (2019). Directors Kate Reilly and Leung Ming-kai have made three of the four stories fictional, treating them as vignettes of restrained realism. A Malay caregiver takes a grandma on an afternoon outing. She wants to go to a political rally where rice will be given out, and she hopes to meet old friends from her village. The old lady is forgetful, and her chatter recycles memories of her youth. The trip turns out to be something quite different, but she doesn’t realize it. The caregiver’s concern turns a simple duty into an act of kindness, as well as a tactful political gesture.

In “Toy Stories,” two brothers meet in their mother’s toy store, which is being sold, contents and all. As with the first episode, memory comes to the fore. The men play games and quarrel about the Power Rangers figures they loved. One, who has a son, tries to find something educational to bring back. He is barely hanging on financially, while his brother has lost his job. A final scene shows a bit of development in their situation, and gives room for a little hope; it’s the only episode that ends, “To Be Continued.”

The third episode is a wistful, Wongkarwai-ish almost-romance. Ruth, an American Caucasian, has come to teach in the school where John, a Chinese, teaches economics. Both are on their way elsewhere–Ruth to teach in Beijing, John to “try something different” in America. They bond over food. (Of course; this is a Hong Kong movie.) From their meeting at a vending machine to the street stalls and cheap restaurants they explore, Ruth learns of the joys of salted egg, pig intestines, and above all yuen yeung, a uniquely local mixture of tea and coffee.

These three stories quietly evoke distinctive Hong Kong culture–the older generation’s memories of moving to the colony, the Gen-X absorption in popular culture, and the particularities of local cuisine. The fourth segment builds on these in looking toward the future.

It’s a documentary showing the barista and cat-lover Jessica Lam running for a local council seat. She faces a pro-Beijing candidate, but she’s more grassroots. She’s also an amateur and runs a fairly minimal campaign. Although she does denounce police violence against demonstrators, the main force of this sequence is the portrait of a sincere young woman trying to improve neighborhood life. This is the only episode with a climax, the election-day vote count. And there is a twist when Jessica gives her final verdict on the results.

The omnibus format has proven a strong option for contemporary Hong Kong cinema, as witness the powerful Ten Years (2015). Memories to Choke On addresses not state oppression, as that did, but the politics of everyday life, the ways in which the sagging economy and the Chinese takeover ripple through the lives of ordinary people. The impact is quite specific: local audiences would know that the actor playing John in the third segment is Gregory Wong Chung-yiu, who is at risk of years of imprisonment for participation in a demonstration. Each story is a telling vignette, a slice of Hong Kong life that will engage overseas audiences and instill a mixed nostalgia in everybody who has ever visited what Chuck Norris in The Octagon (a very different movie) calls “the place.”

Camp as community

The option of embedding the stories within a frame can blur their edges more or less. Sarita (aka Tell Me Who I Am; 2019), an Italian film about refugees from Bhutan living in a Nepalese camp, could have been a straightforward documentary about problems of exile and resettlement under the auspices of the UN. Instead, it blends real-life stories of the refugees with a young girl’s quest to recover her memory. In what filmmaker Sergio Basso calls a more fanciful and energetic approach than a “tragic” documentary would give, we get a film close to magical realism–with DIY Bollywood musical numbers.

Sarita is more or less happy in the camp. She has friends to play and dance with, a school to attend, and every opportunity to worship her favorite god Shiva. But she often quarrels with her parents and wonders why they can’t go back home, a place she has never known. Shiva wipes Sarita’s memory, endowing her with the drive to ask questions of everyone around her. In this Rip van Winkle device, we are introduced to camp routines, as well as the history of her displaced neighbors.

Sarita visits her beloved teacher, only to find that he is often laid low by his injuries from torture sessions. People tell her of ethnic cleansing in Bhutan, of disappeared relatives and political oppression. Deciding that “building my future is easier than desiring my past,” Sarita turns to her immediate prospects. But her sister tells of the hardships of getting a university education. Taking her grandma to be treated for diabetes, she learns of people sleeping in a clinic as they wait days for treatment.

After the family is assigned a home in Oslo, she acquires a super-8 camera and cassette recorder and begins to document the life she will leave behind. Now the world she rejected seems precious. After Sarita has gone, we see her grandmother and those left behind lingering at a tree, studying mementos of their departed neighbors.

Counterpointing the harsh realities of daily routines and homesickness are moments of song and dance, in bursts of brilliant color and gymnastic choreography. We also get fantasy scenes, satires on overeager bureaucracy (the resettlement officer is a hyperactive Gene Kelly wannabe), and signs that youthful exuberance can’t be contained by drab regimentation. We hear “There is no childhood here” on the soundtrack as kids are shown inventing games and playing jacks with pebbles. The ending, however, has the poignancy of pure realism (even though it’s fictitious).

This film is an extraordinary achievement. Basso and his colleagues made it over ten years–filming without electricity and no funding from national governments or NGOs. Yet the minimal conditions enabled close collaboration with the camp residents. Seeing the children’s dances inspired Basso to make it a musical, and he gained access to local leaders. Thanks to the Kuleshov effect, Sarita even appears to interview the head of the resettlement office. Although the performers had some coaching from a theatre director and a choreographer, they clearly have natural gifts, particularly Sasha Biswas, who carries the film.

In the wake of the coronavirus, seventy Italian independent cinemas cooperated in making Sarita available on streaming platforms. There, Basso reports, it has found an encouragingly large audience. Another item to look for on the streaming menu in your area!

Visions of the good life, words of disquiet

One more film about memory, but now the memories themselves are captured on film. And the stories aren’t sealed off in blocks or gently embedded in a wider frame. They’re stacked.

Again, to say too much would soften your efforts to come to grips with the teasing, hypnotic My Mexican Bretzel (2019). Think of it as layered, like a cake.

The image track consists of a Swiss family’s home movies from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. In luscious color we see a couple leading a European life of leisure: summers on the beach, winter skiing, tours of postcard capitals, yummy meals with friends in open-air restaurants. The husband, a genial, brawny fellow, clowns for the camera, but most screen time is given to his wife, a willowy brunette with a radiant smile. The landscapes might have come straight out of Holiday, that oversize American magazine dedicated to worldwide vacationing.

The next layer is a written text, purportedly a diary of Vivian Barrett. This tells of the marriage. Vivian traces the efforts of husband Leon to make and market an antidepressant. Leon’s love of flying during the war has translated into his urge to travel widely, especially on his luxurious yacht. But as the years pass, Vivian starts to record her worries, her dissatisfactions, and the temptation of taking a lover. Her musings are interrupted by remarks she finds in an untitled book by the Indian guru Kharjappalli. (Sample piece of wisdom: “God also doubts your existence.”) The couple’s lives form the outline of an Antonioni film.

Léon is making a record too. He’s wielding the Daddycam as he documents all those vacations and breakfasts and views of Manhattan, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and aqueducts. Vivian has misgivings (“If you film, you don’t have to live”) but learns to use the camera herself, and even steer the yacht.

Finally there is an exceptionally discreet effects track. The home-movie scenes are eerily silent because there’s no voice-over, but occasional noises are dubbed in, and very rarely there’s a snatch of music. On the whole, the absence of musical cues for emotion renders the pictures and the diary texts all the more powerful. (Compare the emotional tug of Jóhannsson’s score for Last and First Men, a film that also “overwrites” mysterious visuals with a text sourced to a woman.) The result is a dry, unsentimental treatment of a crumbling marriage in the midst of Europe’s postwar boom.

Out of 29 hours of found footage Nuria Giménez and her colleagues have fashioned a fascinating film that is at once pure documentary and creative fiction. I like to think of it as another way to assemble a narrative–at one level simple chronology of a cosmopolitan couple’s life, on another the hidden story of voyages to Italy and elsewhere. I kept seeing the ghosts of Bergman and Sanders in this couple on the modern Grand Tour.

I knew about none of these films before encountering them at VIFF, which is of course one reason we cherish this and all other festivals. Granted, there’s reassuring pleasure in seeing the latest accomplishments of established and esteemed old hands (here Ozon, Petzold, Vinterberg, Rasoulof et al.). Just as valuable, though, is the jolt of seeing newcomers present beguiling variants on familiar traditions. Three of these films, as far as I can tell, are first features, and they offer fresh takes on stories we thought we’d seen before.

All are graced with sharp cinematic intelligence and offer pointed commentary on lives lived now and back then, close to home or far away. All remind me of why this VIFF wing is called Panorama. Every movie widened my vision.

Thanks, as usual, to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival. Thanks as well to programmer and consultant Shelly Kraicer for background on Memories to Choke On.

You can sample the films in their trailers: Tales of the Lockdown is here; Memories to Choke On is here; Sarita is here; and a particularly shrewd one for My Mexican Bretzel is here (incorporating, I think, footage not in the film). Giménez’s film won the Found Footage Award at Rotterdam. If you insist on knowing about how her film was made before seeing it, you can check this Film at Lincoln Center interview.

I hope other festivals, and streaming services, and even theatres will pick up all these films for wide distribution.

My Mexican Bretzel (2019).

Vancouver: Three gems from Iran and India

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (2020).

Kristin here:

Among the always bounteous offerings of the Vancouver International Film Festival, my favorite section is “Panorama,” since I enjoy seeing new films from countries all around the globe. Often some of these are from Iran, and the two Iranian films featured this year did not disappoint. The sole Indian film turned out to be an engaging, imaginative tale from an area of the world seldom represented on the screen.

There Is No Evil (2020)

Vancouver is in part a festival of festivals, drawing upon international films already premiered in Berlin, Cannes, Rotterdam, and other earlier festivals. Of necessity, this year’s items come from the pre-Coronavirus festivals, with films from Berlin especially prominent in the schedule. Mohammad Rasoulof’s There Is No Evil, Golden Bear winner as best film, continued the director’s regular contributions to past Vancouver festivals. (For entries on other Rasoulof films we have seen at Vancouver, see here and here.) Christian Petzold’s Undine, discussed by David in the previous entry, won the Silver Bear as best actress for Paula Beer.

There Is No Evil is a deeply ironic title, since its four self-contained episodes deal with one of Iran’s notorious evils, its record for executing its citizens. As Peter DeBruge pointed out in his Variety review, “According to Amnesty Int’l statistics, Iran was responsible for more than half the world’s recorded executions in 2017. The number has since dropped, but the country continues to kill its citizens at alarming rates.”

Often the process of carrying through executions is assigned to hired civilians or is forced to be performed by soldiers. Rasoulof explores various ways in which such executions affect the willing or unwilling people who carry out the orders, as well as the effects on people they know and love. I don’t want to spoil the slow development of these consequences for the characters by describing the plots of each of the four episodes in too much detail. Suffice it to say that the revelation of those consequences are worked up to very slowly and occur dramatically.

The four episodes are shot in quite different styles. Those styles are to a considerable extent determined by the fact that the episodes move to increasingly remote locales.

The first begins in a bustling city and is shot in a bright, ordinary style befitting the depiction of a bourgeois lifestyle, with appointments to pick up spouses and children, shopping trips, and alternately bickering and affectionate conversation.

The second episode abruptly switches to a gloomy, desaturated color scheme of grays and muted browns and greens suited to a film noir (above). This segment begins with a military man assigned to perform an execution panicking because he cannot face killing anyone. During this episode, the tone and even the genre switch abruptly twice, from film noir to thriller to … something else.

The third story has a soldier on leave visiting a family of old friends, including the daughter whom he loves and hopes to become engaged to. Here the film is done in a lyrical, bright style, emphasizing scenes in the lush woods and in the happy rural home of a couple who foster a group opposing the government. Here the soldier talks with the mother of the family.

The fourth episode centers on a couple who have retired to a bee-keeping farm in a remote, mountainous area. They must contend with the visit of a niece, but neither is willing to answer her questions about the past.

I think the style in this part pays homage to Abbas Kiarostami, with numerous shots of the couple’s pickup on winding country roads (see bottom). There’s a specific echo of The Wind Will Carry Us in the motif of the girl’s repeated attempts to find cell-phone coverage to call her parents abroad.

Given the relatively large cast and considerable number of interior and exterior locales, one might wonder how Rasoulof, under an order to stop filmmaking, could make a two-and-a-half hour film critical of government policy. DeBruge’s review, linked above, also comments: “By subdividing the project like this, Rasoulof was able to direct the segments without being shut down by authorities — who are more carefully focused on features — and, in the process, he also builds a stronger argument.” In an earlier Vancouver report, we noted that Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014) used a network-narrative structure because she could only get permission to make a series of shorts–which she then wove together into a feature.

As DeBruge writes, the reliance on episodic structure does not handicap Rasoulof. The slow accumulation of indifference, regret, and guilt demonstrates that executions have unnoticed, unforeseen, and undeserved effects. The stylistic shifts emphasize the differences in those effects and maintain interest across a long film.

The effectiveness of Rasoulof’s film has not gone unnoticed, however, and a Golden Bear is clearly not enough to protect him. On March 4, he was summoned to begin serving his long-delayed prison term, despite the widespread incidence of COVID-19 in Iranian prisons. (On March 1, three days before the summons, Indiewire published a history of government strictures on Rasoulof.) Many official protests have been launched, and one can only hope that once again the result will be yet another suspension of the enforcement of the sentences against him.

Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness (2019)

Yalda is the second feature by Iranian director Massoud Bakhshi, whose first, A Respectable Family, we recommended as “an unexpected gem” when it played in Vancouver in 2012. Yalda is another film that comes to Vancouver via this year’s Berlin International Film Festival, where it was nominated for a Crystal Bear. It also played at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Grand Jury prize in the “World Cinema – Dramatic” category.

The film centers around one episode of a television series, “Joy of Forgiveness,” based on the premise that each week someone convicted of a crime seeks to be forgiven by the victim or a relative of the victim. Although not an actual law, such forgiveness is encouraged in Iran under Islamic law. If forgiveness can be obtained, the criminal is typically absolved of the crime. There are now charities, celebrities (including film director Asghar Farhadi), and other forces working informally to foster forgiveness and free guilty people, though this may include a payment of “blood money” given to the person doing the forgiving. (A real TV show based on this premise, “Honey Moon,” was the inspiration for Yalda.)

In this case, a young, shy working-class woman, Maryam, who had been married to a wealthy older man, has been convicted of killing her husband. She insists, however, that it was an accident. As the film begins, Maryam’s mother brings her to the television station. The young woman is terrified and declares she does not want to participate. But since this would mean a death sentence being carried out, her mother and the production team of the show ignore her protestations and hurry her through the preparations.

Representing the victim is Mona, his daughter, who, as the title of the TV series suggests, is expected to provide the standard happy ending to the show by forgiving Maryam. Mona seems to have reasons to do so, since she would receive the blood money proffered by “Joy of Forgiving” and is planning to emigrate from Iran in the near future.

So far we seem to have a situation familiar from the films of Asghar Farhadi, with two or more people at odds who are gradually revealed to be flawed and to some degree at fault. The situation then typically ends in reluctant understanding between or among the opponents.

As the host interviews the two women, however, he shows a distinct bias toward Mona’s viewpoint. Rather than pleading her case humbly, as the television crew expects, Maryam becomes desperate and accusatory. Her exchanges with Mona grow more heated.

The producers begin to panic. As one points out, this show is occurring on Yalda, a festival held on the day of the winter solstice. The longest night of the year is believed to be unlucky, and traditionally Iranian families gather to eat, tell stories, read poetry, and generally cheer each other up through the night. Seeing a sad ending to the program would badly disappoint the audience.

Telling his story in what is essentially continuous time and at a brisk pace, Bakhshi starts out by sticking closely to Maryam, building up considerable sympathy for her as everyone ignores her pleas and bosses her around. Once the program begins, the increasing hostility of Mona generates a suspense that is well maintained up to the final twists of the ending–twists showing that Bakhshi is not going for a Farhadi-style resolution.

The script is tightly constructed and engrossing, so much so that one could imagine a Hollywood remake–if a plausible legal situation could be devised as the premise.

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (2020)

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (director Pushpendra Singh) also was shown at the Berlin festival, in its Encounters section. It also won best director in the “Young Cinema Competition (World)” at the online competition for this year’s cancelled Hong Kong International Film Festival.

The film begins with a young man, Tanvir, struggling to lift and shoulder a heavy stone, a traditional test for a prospective husband among a tribe to which whom the beautiful shepherdess of the title, Laila, belongs. Soon a title is superimposed: “Song of Marriage,” the first of the seven songs. These songs are sung over the action–unsubtitled, unfortunately–and give a sense of the story taking place in some old folk tale. (Indeed, a title in the credits declares that the film is “Based on a Rajasthani folk-tale by Vijaydan Detha,” a well-known twentieth-century author of numerous such short stories.)

The fact that the tribes cook over open fires and follow what seem to be old traditions reinforces this impression, until a night scene where some of the men wield LED flashlights. Another title, “Song of Migration,” leads to a the journey of the nomadic tribe into which Laila has married herding their large flock toward the village that is their home base. They pass along modern highways, moving aside for traffic to pass, through landscapes that provide beautiful shots (see the top of this entry). This stretch of the film is lyrical and captivating, thoroughly drawing the spectator into the film.

Abruptly another modern touch, a radio carried by one of the men, thrusts the action into the troubled politics of the present. A newscaster declares, “In the Kashmir Valley protests against Article 5A have escalated.” Two protestors, he says, have been killed. The reference is to Pakistan and India’s dispute over control of Kashmir, and the Kashmiri struggle for independence from both. Laila, it later is revealed, is Kashmiri, while Tanvir’s tribe lives in an area controlled by India.

Laila’s beauty soon attracts the attention of the local Station-master and his subordinate, Mushtaq. They hint that as a Kashmiri she might possibly be a terrorist. This accusation comes to nothing, and Mushtaq’s clumsy attempts to seduce Laila lead to a switch in tone. A series of episodes, each a separate “song,” follow Laila promising trysts with him and then bringing her husband along on a pretext. Mushtaq’s continued gullibility in trusting that each new assignation is made in earnest lends a farcical comic touch to this lengthy passage of the film. At the same time, however, Laila is testing whether her husband, strong enough to lift the stone and win her as his bride, has the moral power to defend her rather than currying favor with Mushtaq by turning a blind eye to his designs on Laila.

I felt that the last portion of the film ran out of the energy it had sustained so well, since Laila is strong enough to turn her back on two unacceptable men but has no apparent sense of where to turn once she has done so. Still, overall The Shepherdess is beautifully filmed, as the frames at the top of this section and of the entry demonstrate. It also tells a thoroughly absorbing story.

So far David and I have reported on six films from this year’s Vancouver festival. Already it has become clear that our accumulated experiences from past years have allowed us to trace the development of promising young filmmakers into great ones and to discover promising new ones whom we hope to encounter at future festivals.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

There Is No Evil (2020).

Vancouver: First sightings

Big Tech as Pac-Man: The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

DB here:

Every festival has had to adjust to COVID-19. This year the venerated Vancover International Film Festival continues with some in-person events at the VIFF Centre and the Cinematheque, but most of the screenings are done remotely. The streaming resource is available only in British Columbia and is a wonderful option for regional cinephiles.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll continue our annual tradition of covering some of the outstanding films mounted by this superb festival. As usual, we hope to guide local viewers while the event is in progress and to signal readers about upcoming releases in their territories.

Deep dives

Undine (2020).

No lyrical drone vistas, no establishing shot, no title telling us where and when we are, no voice-over trying to lure us in. Just bam, here it is, deal with it. Any movie that starts with a reaction shot in OTS (over the shoulder) of a fiercely downcast woman gets points automatically. The fact that she goes on to threaten to kill the man she’s talking to is just a bonus.

That threat, made by the protagonist of Christian Petzold’s Undine, is about the only hint that she’s capable of homicide. She seems otherwise a well-adjusted young woman free-lancing as a guide in Berlin’s Urban Development Center. As in other Petzold films, thriller conventions are invoked but suspended while a deepening personal drama emerges. At first, we tag along with Undine in her rebound-affair with Christophe, an engineer specializing in repairing underwater equipment. All is going well enough, but there are signs of trouble, particularly a near-death experience in a lake. Then, after the midpoint, tension ratchets up with two quick twists that put new pressure on Undine to take violent action.

Sorry to be so oblique, but this is one of those movies with a real plot, and since it’s eventually coming to the US, I’m avoiding spoilers. Admittedly, the last twenty minutes take off into new territory, and I found myself unable to know what to expect next. (It’s one of those movies that seems to end several times. That is often a good thing.) But the unruffled precision of Petzold’s direction, the thriftily paid-out backstory, and his gift for suspenseful storytelling mitigate the quasi-supernatural tint of the twists. I tend to see them as GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema), ambiguous moments that may flow from the characters’ imaginations.

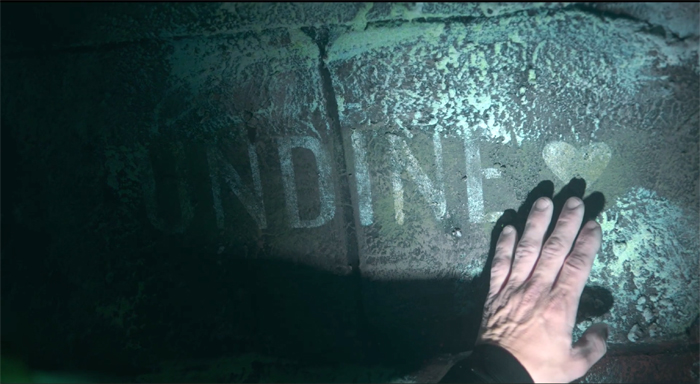

An undine is a water nymph, the heroine’s lover is a diver, her job is to lecture on the rebuilding of Berlin over the years, and his job is to explore a submerged city (which hosts a slab bearing her name). All this was for me a reminder that ambitious directors can invest genre conventions with poetic lyricism. Admirers of Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and Transit (2018) will need no urging to visit a film I found completely absorbing.

A film from two billion years from now

Last and First Men (2020).

On the visual level, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is a good example of what we call “abstract form” in our book Film Art. The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities. Everyday objects can yield these qualities (our example is Ballet Mécanique), but abstract form can also be found in unusual, even unidentifiable sources.

That’s what we get here. The shots reveal structures and textures in immense, brutal constructions of metal, stone, and cement. Are they sculptures? Totems of some bizarre religion? Remnants of blasted modernist buildings? Fragments of space ships crashed to earth? The moving camera reveals their shapes, textures, and off-kilter strains for symmetry. You lose all sense of scale: these might be the size of dinner tables or tabernacles. Most are set against the sky, alternately misty or searingly bright.

No story connects our views of these strange monuments. On the soundtrack, though, a woman’s voice recounts the history of the future. After two billion years, the narrator represents the “eighteenth species” of humans, and via telepathy she informs us of the impending end of human life on Neptune.

We never see any of those events, just the ruins calmly surveyed by the camera. Almost never does the commentary sync up with the shots. The woman’s account of future humans might at first seem to match the carved, staring blocks we see, but she goes on describe them as furry or translucent.

The disparity between description and depiction emphasizes the gap between tracks.

For most of the film, then, we have a split. The image track explores abstract, nonnarrative form. The soundtrack supplies a narrative, actually a Very Grand Narrative. The text, it’s revealed in the credits, comes from Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science-fiction novel, Last and First Men.

There’s yet a third layer. Jóhannsson, a brilliant composer who died in 2018, gave us memorable concert music and film scores (Sicario, Arrival, The Miners’ Hymns). Along with the voice-over we hear a sometimes radiant, sometimes jarring orchestral accompaniment created by Jóhansson and electronic composer Yair Elazar Glotman. The music doesn’t cooperate much with the voice-over. As the commentary proceeds with a businesslike dryness, the music often flows and eddies on its own course.

The fact that the three channels of picture, voice, and music seldom converge actually sets your imagination free. There’s no need to see the images as illustrating the text, or the music as operatically enhancing either one. We’re allowed to keep the realms separate, or to test obscure correspondences. We can, for instance, see the expressive qualities of the shots as enduring remnants of human will–eccentric, obstinate, and obscure as it can be. The music’s alternation of drone passages, scraps of choral lyricism, and ominous rumbles might seem to chart humans’ up-and-down fate in the late Anthropocene. The narration, recited by Tilda Swinton, adds a quality of stoic dignity to the mix. And you’re invited to try out metaphors, as when cavities in what seems to be an elongated cathedral suggest eyeholes for staring across space.

The disparity of channels is enhanced by another mystery I haven’t seen mentioned in reviews. The images betray their origins on 16mm film. There are light leaks on the frame edges, specks of white suggesting dust on the negative, and even bits of grit and hair in the aperture. Perhaps you can see the hair snagged in the upper right of the image below.

These flaws have not been digitally removed. Indeed, the film’s opening moments linger on black frames flecked with white dust, priming us to watch for faults in these images.

The effect is to add an archaic quality, as if this is all found footage from long before the end recounted on the soundtrack. Since the narrator tells us that humankind goes through many near-extinctions until the big one, these relics may be from one of those future collapses–or, perhaps, from our own past, remnants of a calamity we’ve forgotten. The text speaks of “the debased rites of your religions long ago,” and those big-eyed humanoids are reminiscent of Australian aboriginal art.

In all, it’s a bleakly beautiful experiment. The film premiered with live orchestral accompaniment in the 2017 Manchester International Festival, and it must have been hypnotic. The film and soundtrack are now available on a CD/Blu-ray combination, as well as on vinyl.

Meet the New New Boss, same as the Old New Boss

The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

The scathing 2003 documentary The Corporation took seriously the idea that corporations were persons. Their behavior, considered clinically, is that of a sociopath. Now Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott’s followup shows how the 2008 financial crisis provoked corporations to rehabilitate. Hip CEOs admit the existence of racial bigotry, income inequality and the failures of conservative government. The solution? More corporate power. Did this make them any less dangerous?

Nope. Multinationals shape government policy as vigorously as ever, especially in the era of Trump and other demagogues. But the corporations’ new message is soft power. Posing as socially committed, emphasizing stakeholders as well as shareholders, Big Business is (a) trying to convince consumers that it’s on their side; and (b) arguing that the New Corporation will correct the shortcomings of government policy through privatization. In other words: We’ve learned our lesson. We get it. So let us run things. Besides, what choice do you have?

Bakan and Abbott shrewdly show that this ploy neatly fits an updated clinical symptom of the sociopath: “Use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.”

The film begins with a fascinating visit to the Davos Forum, where air-kissing one-percenters solemnly assure us that everybody wins when a corporation acknowledges the public good. The star player is Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase. Having helped crush American cities in the financial crisis (and paying a derisory $13 billion fine), he is now playing rescuer by supporting the rebuilding of Detroit, to the benefit of his company’s image. The film goes on to trace how the public face of caring executives is belied by business as usual, most savagely British Petroleum’s catastrophes in Texas City and at Deep Water Horizon.

Bakan and Abbott marshall a great deal of evidence to show how the plutocracy, and especially those in the digital technology sector, have turned a market economy into a market society. For us, the role of worker-consumer redefines the other dimensions of civic life. You work without union protections and scramble to keep up. You give your personal information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon in exchange for convenience and lower costs. (The old adage holds: If something is free, the product is you.) Schools, postal delivery, war, water, and relationships are all ripe to be rendered as private enterprise. With AI algorithms, the customer-customized milieu of Minority Report is already here.

Talking heads, from Chomsky and Robert Reich to Diane Ravitch and Vandana Shiva, offer pithy critiques, and footage garnered from around the world illuminates each of the points in the Corporate Playbook. As a counterweight, later portions of The New Corporation show some pushback. Katie Porter poleaxes Mr. Dimon in a House hearing, and we glimpse AOC in her usual passionate eloquence. Still, the emphasis falls less on pols and more on citizens who struggle against corporate power.

Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign are shown to be as important to the left as the Tea Party was to the right. The filmmakers give special attention to the efforts of many tough, idealistic people to run for public office. As one commenter puts it, “Even in the worst situations, people always fight.” In a remarkable passage, a dopy prankster from The Corporation is shown to have become a proud progressive after seeing the first film and joining the Sanders campaign.

The film is startlingly up-to-date, incorporating events around the George Floyd atrocity and the Black Lives Matter street actions. Some will say that the late sections drift a bit from the film’s core message of analyzing the fake social concerns of the New Corporation. But income inequality and environmental destruction, central drivers of new social movements, are invoked in corporate PR as vital concerns for companies’ new image, so the final sequences don’t seem to me tacked on. They show what real social engagement, as opposed to panting coverage in Forbes, looks like.

Where do you start? someone asks in Tout va bien. The answer: Everywhere at once. I think The New Corporation indicates that this might just work.

The three films I’ve discussed are exemplary of the strengths that have characterized the Vancouver festival for its 39 years. Here you can plunge into international auteur cinema, unusual experimental work, and documentaries committed to our noblest aspirations. Programmers Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and their colleagues scour the world for provocative films, and the results have taught Kristin and me lessons about cinema we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. It’s worth noting that VIFF’s welcome to Canadian cinema has always been fruitful: The New Corporation, like its predecessor, is a British Columbia production and is featured in the festival’s ongoing True North series.

Fourteen years ago I wrote that Vancouver was the very model of a regional festival, at once deeply local and unpretentiously cosmopolitan. It still is. Take that, corornavirus! Nothing stops dedicated film lovers.

Thanks to Alan Franey, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

A sensitive review of Undine is offered by David Hudson at the Criterion Daily.

A note on Last and First Men: In watching the film, I found myself constantly asking if these structures really existed, or whether they were CGI creations or miniatures or objects purpose-built for the film. Some reviews have revealed their secret identity, and knowing what they are does raise some interesting thematic implications. But I’m refraining from telling you because I think your first encounter with the film ought to include that mystery about what exactly you are seeing. If you want to know what they are, Google is at your service. There’s also this spoiler-filled behind-the-scenes video.

Jennifer Abbott has another documentary in this year’s festival: The Magnitude of All Things. I look forward to it.

Undine (2020).