Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

“Student film,” exploitation film, indie classic

Kristin here:

Flicker Alley continues to bring out an eclectic and unpredictable series of restored films, from French Impressionist classics to Cinerama films to obscure film noir Bs to early films directed by women, and the list goes on. (Search this blog for “Flicker Alley” and you’ll find many more.)

On May 19, the company released a Blu-ray/DVD dual-format set of Spring Night Summer Night (1967), directed by J. L. Anderson. Anderson is known to film academics primarily as Joseph L. Anderson, the co-author with Donald Richie of The Japanese Cinema: Art and Industry (1959, rev. ed. 1983), the first substantial English-language survey of that national cinema.

In the mid-1960s Anderson was teaching filmmaking at the Ohio University in Athens. He and his students made some 16mm short films for the university. He wanted, however, to give them experience making a professional-level feature on 35mm, shot in the part of Appalachia located in southeastern Ohio, near Athens. Apart from teaching film technique, Anderson showed his students art films, many of them from Europe. He was particularly fond of Italian Neorealism and wanted to apply its aesthetic approach to a story set in the poverty-stricken milieu of Appalachia in the wake of the closing of the area’s coalmines.

Students undertook the cinematography and other tasks. The main roles were cast with experienced actors, while local people filled the minor roles and worked as extras. One of the students, Franklin Miller, was deeply involved in the filmmaking: he co-produced, co-wrote, and co-edited the film. The pair even did sound-effects recording, combining their name as “Joe Franklin” in the credits.

Local color galore

The film deals with a farming family. The father, Virgil, has a son, Carl, by his previous wife, who died in childbirth. Virgil and his current wife Mae are raising their daughter, Jessie, along with four younger children. Carl and Jessie have fallen in love and despite being half-siblings, yield to temptation, leaving her pregnant. Virgil causes strife in the family by trying to find out who the father is and to force him to marry Jessie. Eventually the couple begin to wonder if they are indeed blood relations, given that Mae is obviously having a long-term affair with another man.

Although the story is involving, the main strength of the film is the remarkably rich depiction of life in an impoverished, largely rural area. Absolutely everything, exteriors and interiors alike, was shot on location. A remarkable pair of scenes in a crowded bar was shot in Athens rather than the main tiny town, Shawnee, but the difference is unnoticeable.

The supplements to Spring Night Summer Night reveal that the bar scene extras were gathered by advertising that anyone attending the bar would be given five dollars’ worth of fake money good only at the bar. Given that bottles of beer were twenty-five cents, the unexpectedly large crowd became quite lively. The filmmakers were able to insert staged bits of action–mainly a fight between the jealous Carl and a boy who dances with Jessie–among the spontaneous activities of the local people without any of the extras seeming to take notice.

The cinematography in all the locations is beautiful, as the images above and at the bottom of the entry show. While the cameras were run by filmmaking majors, the result looks quite professional. As Larue Hall, who played Jessie, says in the Cleveland Cinematheque Q&A supplement, “I never call it a ‘student film’ when I talk about it.” Anderson obviously was a good teacher.

One memorable scene displays the filmmakers’ skill. It’s a single take, four minutes and ten seconds, that takes place in a bar. The camera begins behind a man whose face we never see, then arcs around him to focus on Virgil.

Virgil summarizes his life, including its more prosperous days when the coal mines were the main local employer: “Better believe it was different when the mines was working. Made some good money in the pits.” He describes his two marriages and his life in the military and concludes sadly, “You try to live your life right, but it just don’t work out.” The other man, offscreen for most of the shot, never replies. (The scene as scripted would have lasted longer, but the limitation of the camera’s capacities forced a condensation.)

This release was of particular interest to David and me, since we knew the two people most involved in the various phases of making the film. Anderson himself visited the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the 1980s, in his capacity as an historian of Japanese cinema. He did a benshi performance to a silent Japanese film, which was a rare treat. After his studies finished, Franklin Miller got a job teaching production in the University of Iowa’s budding film division. There David and I met him a few years later when we were both graduate students. Neither of us took a course with him, but it was a small division and we got to be friends. He’s now a professor emeritus, living in Ohio with his wife Judy, who served as the “continuity girl” on Spring Night, and did other jobs as well. Indeed, as Franklin emphasizes in the supplements, everyone in the cast and crew pitched in wherever they were needed.

The Making-of

To me, almost as fascinating as the film is a making-of documentary included as a supplement: Behind-the-Scenes of SPRING NIGHT SUMMER NIGHT. (This is listed in the menu as 16mm Behind-the-Scenes Footage.) It includes a commentary track that is a basically a long conversation between one of the people most responsible for the restoration, Peter Conheim, who also edited the 16mm footage from 1965 into this roughly hour-long film, and Franklin.

This is a very recent interview indeed, since Franklin’s part had to be recorded remotely due to the current pandemic. In it, despite the roughly 55-year interval since the completion of the film, he remembers the names of all the people involved and gives a great deal of information about the filmmaking procedures seen being used in the footage.

(In preparing this entry, I got in touch with Franklin after having had no contact for years, and I am grateful to him for providing some additional technical details that I’ve included parenthetically here.)

The footage and still photos were shot by several members of the cast and crew. As Franklin remarks in the commentary, “If nothing else, if you’re making a film in Athens, Ohio, and everyone on the crew is a photographer, one of the things you’re going to get is lots of documentation.” Indeed, there were so many people hovering around filming the filming that often part of what you see is them doing so.

Having been a jack-of-all-trades on this project, Franklin is seen in the film nearly as much as is Anderson. At 25 during the shooting in 1965, he looks very young indeed. Here he is with the owner of the farm which was used as the location (interior and exterior) for the main family’s house.

One reason the film looks so professionally made is the equipment used. The production was able to rent some Arriflex 35mm cameras which were outdated and sitting around the equipment supplier’s shop. (According to Franklin, these were model 2C, and needed a large blimp; they also required AC motors to shoot sync sound: “Anything that looks handheld and sync was dubbed.”) The black-and-white 35mm results look great.

Some shots do look very handheld, particularly a frenetic chase for an escaped rooster inside the farmhouse and the lively barroom scenes. Much of the sound was indeed post-dubbed.

Often, though, the camera was on a tripod or a dolly rolling on platforms made of plywood. See, for example, the frame at the top of this section. That’s Anderson in the short-sleeved white shirt and dark pants, walking along behind John Crawford as Virgil. Anderson often directed in this fashion, staying close to the actors. In the same frame above, that’s Franklin in the white T-shirt pitching in as usual by pushing the dolly (improvised from “a prototype sports car that the King Midget Company (Athens, Oh) had abandoned,” again according to Franklin.) Judy, in a dark sweater, sits on the dolly with her continuity notebook.

There are also some impressive tracking shots alongside a speeding motorcycle, done with the camera on a platform sticking out the side of an open van.

At one point we see the filming of a night scene of Carl and Jessie in the woods, with Carl scuffling with his father Virgil. Franklin remarks on the commentary that they had only one or occasionally two small units for night shoots. He would have preferred to have more of these to cast some fill light on the surrounding trees. (According to Franklin, “The light that the couple walk toward at the end was a 5-minute magnesium flare. Three feet long and four inches in diameter. Just like the silent days. Plus it adds smoke.”) As this frame from Behind-the-Scenes shows, the result was very stark indeed, with the glaring light, ostensibly coming from the headlights of Virgil’s car, placing the characters against a dark void.

The result could be said to be more realistic, as woods at night do tend to be very dark. In some shots, though, the low lighting is artistically impressive as well, notably in an extreme long shot of the couple walking in the distance in a patch of dim light that silhouettes some trees, again surrounded by darkness. (See image at top.)

All in all it’s a lovely film, and a major early example of the low-budget regional cinema that later became a staple of the Sundance Film Festival.

A scuppered release

So why have virtually none of us heard of Spring Night Summer Night, which seemed so destined to become a classic when it was finished and ready for release in the late 1960s? Its world premiere was at the Pesaro Film Festival in 1967, and all seemed well. It was scheduled to show at the 1968 New York Film Festival, but for reasons unknown it was bumped in favor of John Cassavetes’ Faces.

As a result, it found no distributor until Joseph Brenner Associates, which specialized in exploitation films, bought it on the condition that some soft-core sex scenes be added. To save the project, Anderson shot these, and the result was released in 1970 as Miss Jessica Is Pregnant. I won’t go into the details of that apparent ignominious end to a project that had been the result of so much enthusiastic, devoted effort by students and local people. It is dealt with in the program booklet accompanying the Flicker Alley release, as well as a supplement, In the Middle of the Nights: From Arthouse to Grindhouse and Back Again, on the discs. After that, the original negative sat in Franklin Miller’s office, and the film was essentially forgotten.

After decades, an effort to restore and reconstruct the original film was undertaken. Again, the full stories of this difficult endeavor are provided in the booklet notes. Anderson and Franklin both approved two small changes that were made to the original film, making this a director’s cut of sorts. (The changes are described on p. 24 of the booklet.) Anderson is now quietly retired in Florida. He was able to participate in the two supplements, Spring Night Summer Night: 50 Years Later and Cleveland Cinematheque Q&A. Unfortunately his health did not permit him to attend when the film finally received its screening, exactly fifty years delayed, at the New York Film Festival in 2018. (For coverage of that event, as well as a good summary of the film’s history, see Chris O’Falt’s piece on Indiewire–which adds a comma, not in the original, to the film’s title.)

The restoration certainly shows no signs of the film’s troubled history and different versions. It’s a beautiful job, and this release should at last elevate Spring Night Summer Night to the status of classic that it deserved from the beginning.

Peter Conheim was co-restorer of the film, along with Ross Lipman, via the Cinema Preservation Alliance. Peter has sent me information on a second planned restoration: “Joe only made one other feature after SNSN, AMERICA FIRST (1972), but it was never released. I actually hold all the original materials on the film and hope to do preservation on it … assuming I can find the funding. It’s a sort-of follow up to SNSN, though very different in tone. Filmed in color, in the same area, but more like ZABRISKIE POINT than SNSN!” Eminent cinematographer Ed Lachman (True Stories, The Limey, A Prairie Home Companion, Carol, Dark Waters, and many more) began his film career by shooting America First, and he has agreed to participate in the color correction.

Peter also tells me that there was a first pass at preservation by by the UCLA Film and Television Archive back in 2014.

Thanks to Franklin Miller, Jeffery Masino, and Peter Conheim for assistance in preparing this entry.

Little stabs at happiness 2: Short and sweet, in a city on fire

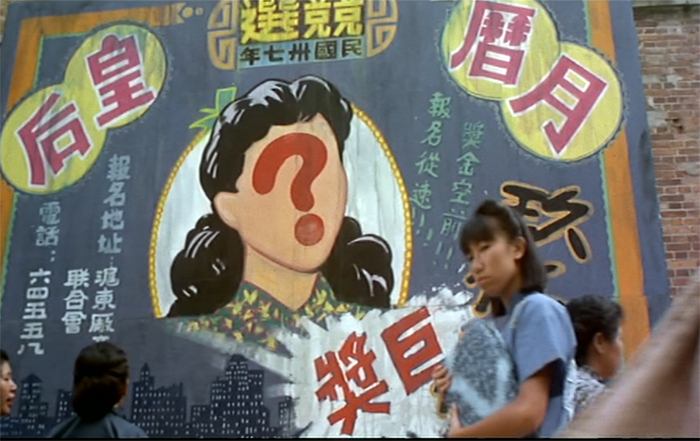

Shanghai Blues (1984).

While US streets pulse with protests against racism and police violence and a fascistic presidential regime, it’s worth remembering that we aren’t alone. Hong Kong has been through this many times, and there the people’s struggle is growing ever more acute. The idea of “burning together” (laam chau) is starting to seem the only option when civil remedies are met by oppression. Hong Kong identity, a palpable force of history, is at stake. As one of my HK correspondents writes: “When it comes it comes. I am sure we won’t just stand here . . . . We will keep fighting for our rights.”

It’s hard to find consolation in these times, but again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs for swiping his title, I offer you a pause to let film art take over. It’s especially poignant in that film, one of Hong Kong’s great contributions to world culture, can seize and hold moments of rapture. All the more ironic that this film, Shanghai Blues, is about ordinary people fleeing the mainland for the British colony to the south.

It’s as goofy a comedy as Tsui Hark ever made, but as usual with Tsui in his prime, it brims with energy. At the end of World War II, Doremi (Kenny Bee), an aspiring composer, is searching for the woman (Shu-shu, Sylvia Chang Ai-chia) he met and lost in a 1937 bombardment. But he’s living unwittingly in the same building she’s in. Meanwhile, a naive young woman (Sally Yeh Chia-wen) arrives from the country trying to make her way in the city. Over all hover two contests: a Calendar Queen prize, and a song competition.

Here’s the sequence that always makes me grin. Doremi comes out at night to play his composition. I really admire how Tsui synchronizes the rhythm of the visuals (especially Sally’s pop-up frame entrance) with the music.

Unfortunately, the film isn’t easily available. There’s a goodish French DVD, but no streaming source I know of. (My clips come from the laserdisc.) If you want more, and at the risk of a supreme spoiler, I offer you the climax, a reprise of the balcony moment that yields a happy ending and a bittersweet time loop.

This virtuoso scene is another example of Tsui’s skillful use of music, cutting, and composition. The movie may be set in Shanghai, but its shameless vivacity is pure Hong Kong.

Here are some resources if you want to help the people of Hong Kong. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for this link. Yvonne blogs, captivatingly, at Webs of Significance.

I write about Tsui, and Shanghai Blues, in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment.

Shanghai Blues (1984).

Sometimes a swordfight . . .

The Valiant Ones (Zhonglie tu, 1975).

DB here:

. . . makes you sit up. And notice a simple but ingenious cinematic technique.

One of the refrains of this blog is: We want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

Over my years of studying Hong Kong film, I kept coming back to the work of King Hu (Hu Jingquan), one of the great directors of Chinese cinema. Most famous for A Touch of Zen (1971), Hu made several other striking martial arts films: Come Drink with Me (1966), Dragon Inn (aka Dragon Gate Inn, 1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), and Raining in the Mountain (1979).

Kristin and I have a special fondness for The Valiant Ones (1975), which consists largely of virtuoso combat sequences. Here we find some of Hu’s most spectacular experiments in staging, framing, and cutting action scenes. The story isn’t complicated, but the result lives up to his motto: “If the plots are simple, the stylistic delivery will be even richer.” Unhappily, for reasons of rights, The Valiant Ones is harder to see than his other masterworks.

When I was studying Hu’s work at a European archive, I told the archivist that watching The Valiant Ones I had started to understand his secrets. She smiled and said, “All right, but don’t tell anyone.” Ha! Fat chance. I broke the news in an article and then in Planet Hong Kong. I use our current lockdown to share it more widely.

Suppose you have a character called the Whirlwind Swordsman. He circles his adversary so quickly, ducking and bobbing, shifting front and back, that the target is bewildered. How would you render this quicker-than-the eye tactic on film? Today’s directors think automatically of digital effects. But that wasn’t on the menu in 1975.

Wu Jiayun and his wife are pretending to be interested in joining a pirate gang. In a series of audition bouts, the chief pirate sends his minions to spar with them. Here we see first Wu’s wife take up a monk’s archery challenge. (I include that as bonus material.) It’s a fair sample of the rhythm Hu gets through a combination of editing and figure movement. The audition continues with Wu showing a stout pirate his Whirlwind technique.

Did you see what King Hu did? He used a double for Wu, dressed him in white, and had him rocket into and out of the foreground while the primary Wu dodged in and out of frame in the background. Sometimes Wu leaves one spot and reappears elsewhere only one frame later!

Significantly, Hu set up this cleverly confined framing by means of a simple axial match-on-action. The larger view oriented us to the area clearly.

Giving up his fondness for discontinuous cuts, Hu used this cut to prime us to expect continuity of space as the shot unfolds. The double is in effect inserted in the splice.

Is it merely a trick? All’s fair in cinema. The gliding, percussive force of the frame entrances and exits shows us a preternaturally gifted fighter whose moves are too fast for the naked eye. We have no time to reflect on how it was done.

Interestingly, Wu seems to have taught Mrs. Wu his technique. At the climax she gets a chance to practice surrounding a hapless fighter. See my stills up top and at the bottom.

Secrets? You bet. We appreciate them all the more when we work to discover them.

For more on King Hu, see Stephen Teo, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). I discuss Hu’s style in more detail in “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema, and in “Three Martial Masters” in Planet Hong Kong, 2d. ed.

A Touch of Zen and Dragon Inn are available in fine restorations in the Criterion Collection and on the Criterion Channel. Also on the Channel is Hubert Niogret’s superb biographical film about King Hu.

Some recent entries (here and here) review the ideas of axial cutting and matches on action.

This is the second time I’ve used King Hu in this series; he’s a rich source of startling cinema. For other “Sometimes…” entries, go here.

The Valiant Ones (1975).

Hollywood starts here, or hereabouts

The Woman in White (1917). Toning by DB.

DB here:

Do you know Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White? I hope so.

The traps set by this novel of mystery and suspense–a prototype of what was called “sensation fiction”–are still ensnaring audiences. Serialized in 1859-1860, it became one of the best-selling books of the nineteenth century. Merchandisers pounced on it, offering Woman in White cloaks, bonnets, perfumes, and songs. Stage and film adaptations followed. The Brits, always eager to mine classics, have created no fewer than three TV versions (1982, 1997, and 2018). There’s a pretty good Warners “nervous A” picture from 1948, with Sydney Greenstreet as the deadly, jovial Count Fosco.

The 1917 version from the Thanhouser studio is, lucky us, currently streaming on Vimeo for free. It’s also available on DVD, as part of the excellent series of Thanhouser films. The print is a 1920 re-release, but nothing significant seems missing or altered.

Apart from its entertainment value, the Thanhouser Woman in White can teach us a lot about film history. Why? Because it sums up very forcefully what American narrative cinema could do in that crucial year 1917. Forget your Griffith, leave aside (regretfully, just a moment) your Webers and Harts and Fords and Fairbankses. The mostly unheralded team of screenwriter Lloyd Lonergan and director Ernest C. Warde have given us a concise demonstration of the power harbored by classical Hollywood from the start. The storytelling tools assembled in that era remain with us still.

Women in peril

The novel’s plot is a tale of–well, plots. Counterplots too.

Collins’ book is hugely complicated, swirling together secrets, hidden identities, abduction, impersonations, illegitimate birth, bigamy, insanity, forged records, fake tombstones, assorted hugger-mugger, and timetables that even the author had trouble keeping straight. The intricacy is magnified by Collins’ decision to adopt a “casebook” structure, in which participants and onlookers write up their accounts of what they witnessed. Each piece of testimony is restricted wholly to one character’s viewpoint, and the writers are forbidden to fill in material they learned later. “As the Judge might once have heard it, so the Reader shall hear it now.” This stricture isn’t fully observed, though, because at least one witness sneaks looks at what counterparts have written.

The book’s key image is, of course, the apparition that greets Walter Hartright on the road one sultry night.

There, in the middle of the broad, bright high-road–there, as if it had that moment sprung out of the earth or dropped from the heaven–stood the figure of a solitary Woman, dressed from head to foot in white garments; her face bent in grave inquiry on mine, her hand pointing to the dark cloud over London as I faced her.

Recovering his senses (“It was like a dream”), Hartright listens to her gap-filled story and helps her find a cab. But soon he sees two bravos halt their carriage and hail a policeman. They ask: Has he seen a woman in white? No. Why does it matter? What has she done?

“Done! She has escaped from my Asylum. Don’t forget: a woman in white. Drive on.”

The first installment ends here, and the adolescent window opens a little wider.

The main plot centers on Laura Fairlie and her half-sister Marian. Hartright is engaged as Laura’s drawing teacher and they fall in love. But Laura’s father has promised her to Sir Perceval Glyde, an apparently upright aristo. (Collins was opposed to marriage as an institution. His class hatred comes out as well, though perhaps not as scathingly as it does in his other masterpiece, The Moonstone.) Once the marriage takes place, Glyde introduces into the household Count Fosco, a suave “doctor” with the habit of letting his pet mice scamper around his waistcoat. It doesn’t take long for Marian to realize that Glyde has a Secret, and she must turn detective to protect Laura from him.

Without pressing into spoilers, you can already tell that this lays down a template for the sort of story Hollywood would later love to tell. The Woman in White is a prototype for the woman-in-peril plot that we’ll find in Suspicion (1941), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), The Spiral Staircase (1946), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Sleep My Love (1948), and many 1940s classics. These in turn rely on literary works in Collins’ wake by Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon Eberhart, and other women authors who updated Gothic and sensation-fiction conventions for the twentieth century.

Lloyd Lonergan was said to have suggested reducing the eight-reel cut of The Woman in White to only six. It’s indeed a tightly coiled presentation of Collins’ sprawling plot. Swathes of backstory are dropped. Instead of Collins’ multiple narrators we get an omniscient narration that shifts freely across various intrigues. Fairly quickly we learn that Glyde and Dr. Cumeo (the Fosco of the novel) are scheming to switch Laura with her lookalike Anne, the woman in white. We also realize that Marian, as an obstacle to the plan, is in mortal danger. Thanks to crosscutting, we’re aware of several lines of action unfolding at once, and in a film full of spying and eavesdropping, compositions tell us who’s snooping on whom.

Still, some revelations are saved for the end, notably one that looks forward to the flashback-heavy 1940s. When Laura and Marian discover Glyde’s secret, their informant gives them the crucial information in a flashback, which precipitates a fiery climax. The flashback device was previewed when Marian, recovering from her collapse, recalled the plans she heard on the patio between Glyde and Cumeo; a nearly Surrealist dissolve superimposes that earlier scene.

In preferring to give us a lot of information, favoring suspense over surprise, this Woman in White is typical of Hollywood scriptwriting of the classical years. In particular, the film employs strategies later elaborated by Hitchcock (discussed here and here and here). One scene in particular displays the Hitchcock touch, years before Sir Alfred took up filmmaking. Even more specifically, let’s note that the basic situation looks forward to Notorious: a woman imprisoned by her husband and a confederate is slowly softened up for disposal.

Choreography, cutting, and showing us the door

Anyone who has viewed films with critical attention must be aware that in a film we are constantly, and without knowing it, being directed what to look at. In a stage play you may be looking at one moment at the actor who is speaking; at another moment watching the face of the person addressed, or observing the behaviour of other characters on the stage. If you go repeatedly to the same play, you may choose to look at different actors in a different order, for you certainly cannot observe everybody and everything simultaneously. But in a film, the lens of the camera is constantly telling you wha to look at–it may be a close-up of the actor’s hand, by the movement of which he betrays the emotion not visible in his face.

T. S. Eliot, 1951

The 1910s were an exciting era in cinema because, as I try to show in this video lecture, the foundations of “our cinema” were laid then. The film business, movie culture, and mass audiences settled into patterns that would hold for over a hundred years.

Just as important, the forms and styles of film craft were put in place. Among those changes was a transition from a style that relied on performance and staging to an approach more reliant on editing, on breaking scenes into many shots. The dominance of editing as a principle of guiding attention is evident from the Eliot quotation; he can’t conceive that staging, lighting, and other “theatrical” techniques could steer us to the important parts of the action.

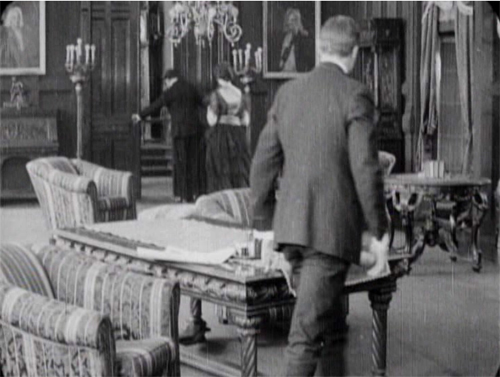

The earlier, “tableau” approach to scenes was perfectly capable of funneling attention too, but editing had many advantages, both economic and aesthetic. By 1917, as Kristin and Janet Staiger and I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, the editing-based approach had coalesced into the dominant style. The Woman in White is a nifty illustration of what an ordinary film from that year could accomplish with cutting–while still retaining vestiges of the tableau style.

A simple example of the tableau technique comes when Sir Perceval Glyde calls on Laura and Marian. He has just kissed Laura’s unwilling hand, and Marian comes up from the rear of the shot to him. As she moves forward, Laura shifts aside slightly to clear our view of the others. This choreography doesn’t seem stilted because it expresses Laura’s withdrawal from her fiancé.

This is an example of the Cross, the staging technique that coordinates actors’ switching positions in the frame. Marian moves from frame left to frame right as Laura shifts to the left.

The tableau approach often plays between a lateral arrangement of characters in the foreground and a more diagonal array of figures packed into depth. As the shot unfolds, Marian is given a beat to take notice of Laura’s reaction as Glyde retreats to the background. She conveniently blocks his departure as she looks warily back at him.

But Glyde steps back into visibility in the distance as he says goodbye, with the women turning away from us so that we’re sure to concentrate on him. Then as the women turn back to react, he can be glimpsed leaving on the far right.

Doorways in the distance, characters advancing to and retreating from the camera, figures spreading themselves out horizontally but also blocking our view of things behind them, only to reveal them at the right moment–these tactics of the tableau became supple and subtle during the late 1900s and throughout the 1910s.

Eliot need not have worried that our attention would stray. Centering, frontality, movement vs. stasis, lighting, gesture, and other creative choices push us to notice the important elements of the scene. And these factors aren’t equivalent to what we see on the theatre stage; the optical properties of the camera lens create a very different playing space. (See here and here.)

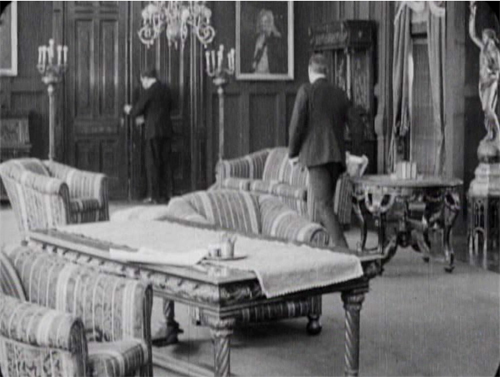

Tableau staging hung on in editing-driven cinema, but it tended to be relegated to the role of an establishing shot. The first part of this scene consists of another tableau setup broken by a cut when the slimy Glyde kisses Laura’s hand.

Here the closer view underscores his gesture while isolating Laura’s concern.

The coordination of staging and cutting is nicely shown when Walter Hartright, having resigned from his post as Laura’s teacher, accidentallly encounters Glyde at the train station. Glyde is coming to arrange his marriage to Laura, so the plot needs to establish the friction between the two men early on. As they confront each other, Glyde’s assistant loads his luggage into the cab in the background.

The first phase of the scene choreographs the men’s encounter through the Cross.

Then close views underscore the significance of the encounter.

Cut back to a two-shot that reorients us.

The fact that it’s not the same framing as we saw at the start indicates the reliance of the style on editing; even the full view is re-calibrated in light of changing shot scales. And during the shot of Walter, Glyde’s position has changed from his orientation in his medium shot. That’s the sort of flexibility editing gives you. The new arrangement heightens the clash of the two men. (Typical of the 1910s emphasis on depth, Glyde’s assistant and the driver continue to load the cab in the background.)

Glyde’s enlarged hand kiss and the inserts of the two men in the station scene exemplify the axial cut. This is a cut made along the lens axis of the camera–a straightforward enlargement of a chunk of space. It’s very common in 1910s cinema, and it’s still around, though it’s not as common as it was. Editors came to prefer analytical cuts that were more angular, yielding less the sense of a sudden enlargement. Sometimes you’ll see claims that cut-ins or cut-backs should shift the angle by 30 degrees. Yet Kurosawa and Eisenstein made powerful use of the axial cut, and it’s sometimes used as a self-conscious device. During the 1910s, some directors began using the over-the-shoulder (OTS) framing as a way to assure distinct angle changes.

The cut to Glyde’s creepy kiss is also a match on action, smoothly linking Glyde’s gesture across the shot change. This too emerged in the 1910s and became a mainstay of classic editing technique, to this day. (See my earlier post on Watchmen for contemporary examples.)

The Woman in White has several adroit matches on action, which shows that the learning curve among directors was more or less complete by 1917. When Walter first encounters the mysterious woman on the road, his striking a match is carried across a cut, with the second shot introducing her coming toward in him n the distance.

One of the most common editing devices of classical continuity is the eyeline match, and filmmakers were mastering this from quite early on. By 1917, it was part of every director’s tool kit. We can see how it works together with the other techniques in a fine, smooth scene that leads up to a crucial turning point in the action. Glyde and Dr. Cuneo are in the library, where Marian is uneasily reading a novel. Cuneo moseys over behind her, softly threatening, and an axial cut matching his movement lets us know she notices.

Another match on action brings her off the sofa. Love those delicately splayed fingers.

As she starts to leave, we get the Cross, as Glyde rises from his armchair and goes frame right. We now get the start of a major piece of business: Cuneo’s byplay with the sliding doors.

Securing their privacy, Cuneo prepares to consult with Glyde about their skulduggery. But a match on action, carried by a powerful axial cut–a huge enlargement from the extreme long shot setup–alerts us. He’s listening.

Another match on action as he busies himself with the door. A new diagonal composition prepares us for a shot of Glyde to come shortly. And yet again Cuneo is matched as he opens the door.

The payoff: Cuneo has detected Marian outside listening. She bluffs, saying she left her novel behind.

Now comes the shot that was prepared for by the over-the-shoulder long shot above. It’s not an axial cut, but a genuine reverse angle on Glyde, who’s suspicious about Marian’s return.

This is a killer shot because the camera can assume a drastically new position. It has put us in between the characters in a way we weren’t in the station scene. In effect, there’s an axis of action running from Glyde to the doctor and Marian at the door. The reverse angle is a one-off technique at this moment, but the possibility of penetrating the dramatic space in this way will be central to continuity cutting.

Now tableau principles can kick in. Marian comes forward and gets the book while Cuneo watches warily in the background.

In the course of the shot, Marian leaves, and this time, thanks to deep staging, we and the plotters can see she’s not eavesdropping. As she goes upstairs, Cuneo closes the door and the men can settle down to scheming.

Five matches on action, a striking eyeline match, restrained but pointed performances, and a cogent staging of the action have yielded a vigorous, engaging scene. By 1917, classical screen storytelling is well established in even a run-of-the-mill production. But there’s nothing run-of-the-mill about the suspense that follows this trim tension-builder.

1910s noir rides again

The Woman in White illustrates a lot of other 1910s innovations in pictorial storytelling. There are, for instance, some concise special effects, as when on Laura’s wedding day she sees herself and Walter in her vanity mirror.

There are also dramatic lighting effects, motivated by firelight, single lamps, and eventually lightning flashes.

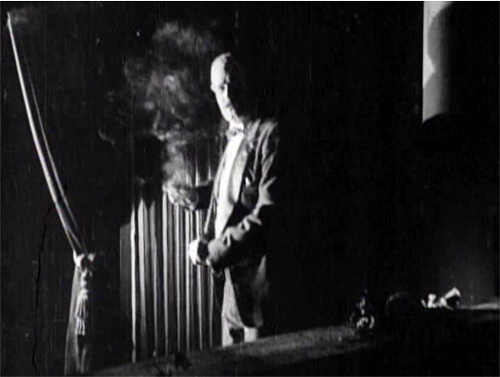

But more audacious is a sustained experiment in “1910s noir.” At that period filmmakers began associating crime and mystery with shadows and stark lighting. (See this entry.) When Glyde and Dr. Cuneo adjourn to the terrace to discuss their scheme, we get a remarkable instance. I won’t indulge my impulse to shower you with images, but I’ll try to suggest why you should try to see the sequence for yourself.

While the men smoke and talk outside, Marian has seen to the sleeping Laura before going to her own bedroom. (A sign of the film’s tidiness is the way it establishes the main characters’ rooms in the upstairs hallway. This geography becomes important when Glyde and Cuneo exchange Anne for Laura.) Opening her window, Marian hears the men outside and ventures onto the balcony above them. This yields a remarkable extreme long shot: She eavesdrops from above.

It’s a difficult shot by later standards. The main action is wildly decentered, set off on the right. But at least this framing has the virtue of preparing us for the later development of the scene, which will involve Marian sneaking along the balcony back to her room, where the light comes from.

The vertical layout of the action is immediately clarified by two closer shots, a lovely chiaroscuro image of the men and the other of Marian listening.

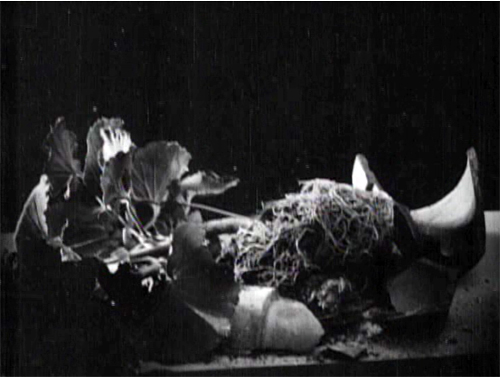

She hears just enough to suggest the men’s scheme before complications ensue. Glyde goes inside and upstairs, where he might discover her. Meanwhile, a rainstorm starts, and Marian dislodges a potted plant. Cuneo turns, in a new setup that emphasizes the railing in the right foreground, so that we can see the fallen plant. The shattered pot is given a close-up more or less from Cuneo’s viewpoint. His reaction supplies a moment of suspicion.

Marian, now drenched by rain, seems trapped between her two adversaries. Will one or both discover her?

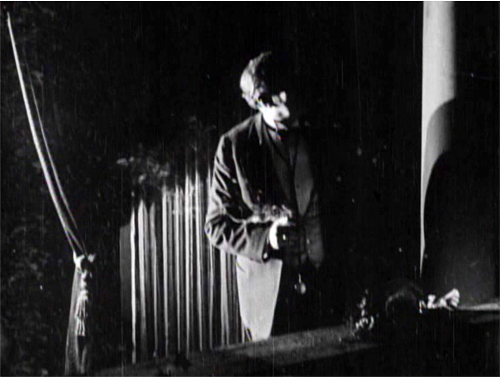

Glyde who has gone to Laura’s window and is looking around outside. We’re reoriented through a new master shot of the house, a framing that varies from the original setup. The shot shows both Laura’s and Marian’s windows lit. There follows a dark passage in which Marian creeps up to Laura’s window. That action takes place in the shot I’ve put up above.

An extra twist: Glyde looks out, but then pulls the shade. Little things mean a lot. A soaked Marian manages to crawl back through her window.

Apart from its virtuosity in handling cutting and lighting, the sequence is crucial for the plot. Marian collapses from her exposure to the storm, and her illness provides a pretext for Cuneo to isolate her while he and Glyde proceed with their plan.

I invoke Hitchcock because this long passage of suspense depends on our knowing all the relevant factors in the situation, and the possibility of a giveaway–the smashed plant–drives up the tension. What I’m really saying, I guess, is that Hitchcock expanded and deepened story mechanics that were already in place in the silent era. Apart from refining them, he managed to brand them as his own.

No film from 1917 or thereabouts is faultless in executing the new editing-based style. The Woman in White has its share of mismatches. Then again, so do movies from the 1920s to the present. (Don’t get me started on the mismatched cuts in The Irishman, 2019.) The crucial point is that the system of Hollywood storytelling and style is in place, and not in a crude form. Talk all you want about post-classical cinema, chaos cinema, post-cinema–whatever. The variations we detect today arise against a background of stable norms that remain a lingua franca of world filmmaking, and they’re headed well into their next century.

Thanks to Ned Thanhouser for years of faithful service to the studio’s legacy. Now is an ideal time to visit his site for background on this remarkable company and the efforts to preserve its output. A staggering 132 Thanouser films are available for streaming on Ned’s Vimeo channel.

To find out more about what preceded this crystallization of techniques, see Charlie Keil’s Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking 1907-1913 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2002).

An excellent survey of Collins’ place in the history of dossier novels is A. B. Emrys, Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011). Her treatment of Caspary and Laura, both favorites of this blog, is just as valuable. My quotation from T. S. Eliot comes from “Poetry and Film: Mr. T. S. Eliot’s Views,” in The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot: The Critical Edition, vol. 4: A European Society, 1947-1953, ed. Iman Javadi and Ronald Schuchard (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 581.

For lots more on 1910s storytelling, see the categories 1910s Cinema and Tableau Staging. Flashbacks, the woman-in-peril plot, and other conventions that coalesce in the 1940s are discussed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The Woman in White (1917). Toning by DB.