Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

Just really long films

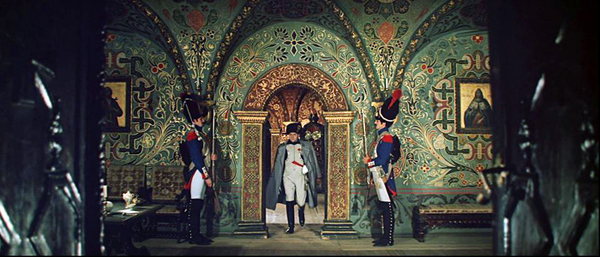

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

Who will match the Watchmen?

Watchmen (2019), Episode 7.

DB here:

If we want to understand the craft of filmmaking, we should pay attention to what filmmakers say about their technique. Sometimes we have to confirm what they tell us with other evidence and the onscreen results, but practitioners usually offer unique angles on their creative choices. For this reason I found it fascinating to come upon what Director of Photography Gregory Middleton had to say about his work on HBO’s limited-series Watchmen.

I had read the comic back in the 1980s and was intrigued by its experiments in pictorial storytelling. I’d also seen the movie, which I thought not as adventurous as the book and vitiated by the book’s adolescent nihilism. (Your mileage may vary.) But Middleton’s interview made me watch the series. So I thought I’d use this anxious pause in normal activities to share some ideas with you.

Middleton has a lot to say about the visual design, such as the sort of lenses he used to get startling depth effects. These echo some common graphic-novel compositions.

But I got more interested in other questions. How does the show adapt some classical cutting techniques? And how do those techniques square with the “editing” techniques we get in the original comic?

Here’s the relevant passage:

And transitions are the biggest tell when you cut from a beat of one thing to a beat of something else. In the case of the comics, one of the transitional devices we wanted to use to echo the graphic novel is the match cut. In the comic you’ve got one panel with a character in the foreground and someone in the background. The next panel is the same character in the foreground, but they are somewhere else — or somewhere else in a different outfit. And the background is something similar, but it’s something else, and you’re basically just jumping time because you’re really with the character and where their state of mind is, so the intervening time between how they went from here to there is irrelevant.

There is a great one in episode two where Angela walks back after they just sat down, and she sort of disagrees with the idea of going to rustle up the people at Nixonville, and she walks away, and she’s pacing as a match cut to her pacing at the police lineup at Nixonville. You go right where she’s thinking, like Okay, I don’t want to be here, but now I’m gonna be here, and suddenly you’re right there.

The match cut is also a way to instantly transport the audience without introducing a lot of other extraneous visual information. In episode four, we did her opening and closing her trunk when she is going to just get rid of the wheelchair she’s cut apart. She chucks it in the trunk, slams the trunk, and it’s a match cut to her opening the trunk, and she’s already somewhere else. And that just works — you don’t need to see her driving and parking and all that. The point is you just know she is dumping this thing, and it’s a nice, clever way to keep you on point with where she is with her intent.

Afterward, it’s like he’s just jumped ahead again — both places, same time. So it’s a way to sort of double-use that technique. It just takes a lot of planning and preparation. Nicole [Kassell, director/producer] and I worked hard on all the transitions in that episode to try and achieve that effect and make it interesting.

The transitions between scenes that Middleton is discussing are, I think, what have been since the 1940s called “hooks.” His comments open up some ideas about how editing works with them.

There are some spoilers, but not my usual quota.

Matchmaking

We can enhance our understanding of filmmakers’ creative options if we systematize a little bit the choices they face and the terms they use. That’s what I try to do in the online essay on hooks between scenes. There I suggest that we can have four sorts of palpable hooks from shot to shot: sound/sound, sound/image, image/sound, image/image. My examples come from National Treasure (2004), a movie that revels in tricky transitions.

For example, one transition in Watchmen creates a sound/ image hook. The Game Warden tells Adrian, “No Mercy” and we cut to a close-up of a Mercy perfume being tested on a focus group.

Middleton calls the cuts that create image/ image hooks “matches.” “Match” is a broad term that points up a general principle of cutting for continuity. In a match shot-change, which might be a cut or a dissolve, something in shot B picks up something that was in shot A. Without distinguishing different types of matching, Middleton is stressing how continuity editing techniques, normally applied within scenes, can be used as transitions between scenes as well.

So let’s create an initial menu of possibilities. Within scenes, there’s the eyeline match, which shows a single character looking, followed by a shot of what the character sees (not necessarily from their optical viewpoint).

Shot/reverse exchanges like this one often rely on the eyeline match, but need not; you can have a shot/reverse pattern if the characters aren’t looking at each other. (Imagine two people talking with their backs to each other.) The eyeline match can link more than two characters within story space.

There’s also the match on action, where a bit of movement in A is carried over into B, despite the change of camera position. The scene between Wade and Angela continues with a combination of the eyeline match and the match on action.

Another sort of match plays upon the sheer pictorial qualities of the two shots. As Middleton says, shapes and color patches can be carried over from the background or foreground or both. Filmmakers don’t seem to have developed a specific term for this type of shot change, although they were clearly using it from at least the 1920s onward. (Eisenstein was the most explicit.) In Film Art: An Introduction, Kristin and I proposed calling the lining-up of compositional features from A to B a graphic match.

Precise graphic matches are common in experimental films, but they seldom show up within scenes of narrative films. Still, Eisenstein, Lang, Ozu (here, from An Autumn Afternoon), and a few other directors made bold use of them. And they’re obviously a matter of degree: Ozu can match an overall shot in some detail, as above, or just one portion of the frame.

We might add the possibility of the “category match,” as when a prop in shot A is followed by something comparable in shot B. Imagine cuts among wanted posters inside a sheriff’s office.

When we move beyond the individual scene, what are the possibilities? Clearly, all types of match-cutting can be used for transitions.

In Watchmen, an eyeline match shifts us from Angela, lying wounded on her living room floor, to a view of Judd looking down at her in the hospital when she awakens. Here the eyeline yields an optical POV.

A match on action takes us from one scene of Cal opening his hand to another as Angela reaches for the hydrogen-atom ring.

A hook can also exploit a graphic match. As Laurie lies sideways after a bomb blast, the image dissolves to a similar composition, a twisting view of a masked bust.

Middleton points to one striking moment that viewers are likely to notice: a match on action that’s also a bold graphic match. Angela strides away from one scene and continues her movement, and her compositional thrust, in a new location, Nixonville.

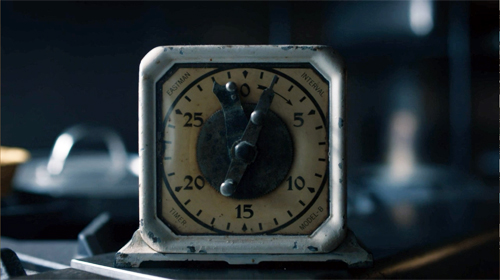

The “category match” is at work on occasion too, as when one scene ends on a pocket watch and the next starts on a clock face.

The category match blends with the graphic match when hands links scenes.

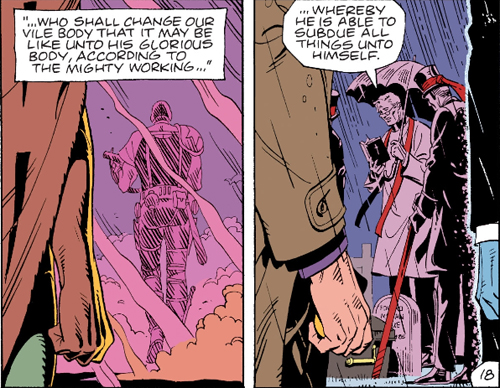

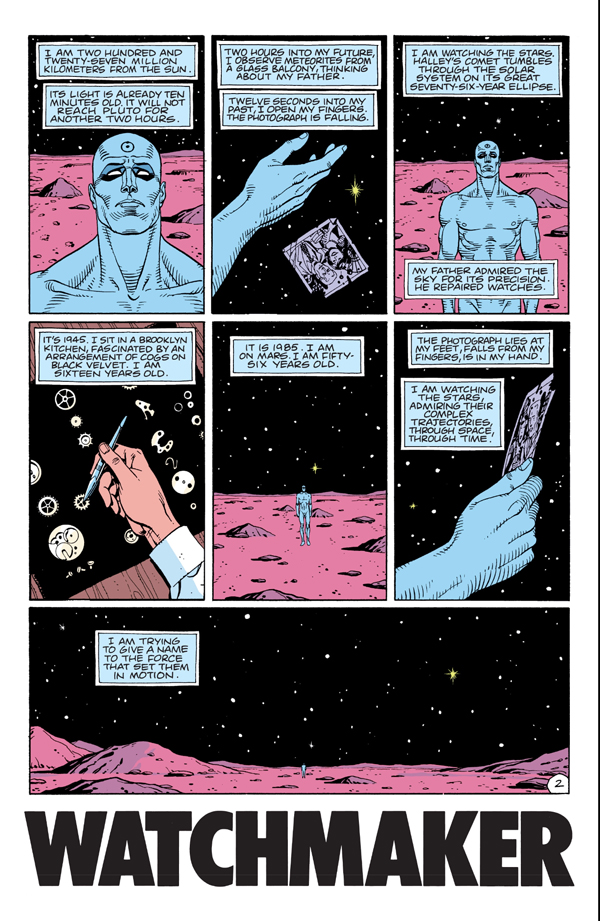

What seems to have sensitized the show’s creators to the possibilities of hooks is the fact that the Moore/Gibbons comic makes punchy use of graphic matches between panels. These are often used to signal character memories by opening and closing flashbacks.

Vivid as these examples and others are, the hook, even the graphically matched one, has a long lineage, as my essay tries to show. The creators of Watchmen are working in a distinct tradition of classic filmmaking.

Showing and showing off

More broadly, that classic tradition favors speed and quick pickup. The new Watchmen is essentially a police procedural, unlike the comic and the feature film. Accordingly, the investigation of a crime is interwoven with the personal lives of the police, the “cop soap opera” that brings in friends, family, lovers, and secrets from the investigators’ pasts.

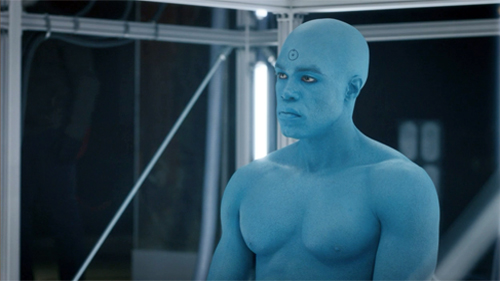

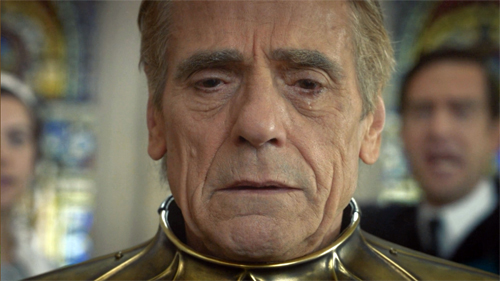

The crucial backstory involves Angela Abar, who knits together many threads. The child of a US black soldier and a Vietnamese woman, she became a policewoman in Tulsa and underwent the new militarization of the force in response to white supremacy. Some of the earlier Watchmen team, notably Adrian Veidt and Dr. Manhattan, are still exercising their power, while Laurie Blake, the daughter of Silk Spectre, is now working for the FBI.

Like the comic, the series must move the plot swiftly between past and present. The comic splinters time more audaciously, jumping back and forth across its grid of nine vertical panels. But in a classical film, where you don’t normally pause or go back, the story must unwind linearly, and so other strategies come forward to impose a felt pattern.

Older films might dwell on the aftermath of a scene, letting the tension relax a little, and provide a cadence that marks off a distinct section. Modern films, especially if they’re presented in the distracting environment of home viewing, display a need to maintain a rapid pace. So scenes push to a high point, then provide a “button” like that close-up of Laurie, and then move swiftly to the next. Among other advantages, this tactic keeps people from pausing or changing the input. Still, the scene shifts need to be clear fairly quickly.

Hooks can help on both fronts. They snap up the pace, keep us alert, maintain interest from moment to moment. A less clear-cut hook can provide a bump of surprise that teases us into the next scene. Soon, though, we will get imagery, and especially dialogue, that anchors us in the ongoing action.

Hooks also provide motifs that can cascade through the film. Adrian’s ambitions to be the new Alexander the Great are provided by cuts that mock his pretentions.

And, as in the comic, the cinematic hooks facilitate subjectivity. The most common way classical storytelling justifies unrealistic or nonlinear narration is through getting into characters’ heads. (Middleton: “You’re really with the character and where their state of mind is.”) Abrupt and startling cuts can be motivated if what we see is a memory, a dream, or a hallucination. This is what we get when Angela embraces Judd’s legs: a match-on-action hook to a flashback of her slow-dancing with Cal.

The most elaborate hooks can provide something more: a certain elation in virtuosity. The precise matching of Angela’s stride across those two scenes above is a stylistic flourish that asks us to appreciate the care and bravado of the filmmakers.

Watchmen‘s hooks, however flamboyant, stand out against a pervasive backdrop of classically constructed scenes. We get lots of over-the-shoulder reverse angles, properly timed reaction shots, now-standard cuts to extreme distant shots that provide a “beat” for the scene, and other devices that have been around for decades. Plenty of other traditional strategies for narrative coherence are on display, from goal-oriented protagonists and deadlines to newspaper headlines and TV broadcasts as sources of impersonal narration. There’s even the inevitable Hollywood line: “What are you doing here?” As usual, striking moments emerge out of a familiar flow of narrative cause and effect, with some mysterious gaps eventually filled.

Paging the Watchmen

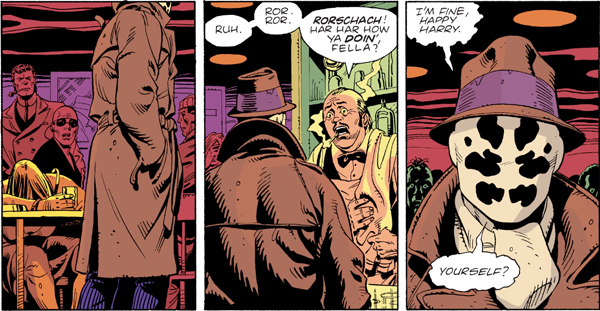

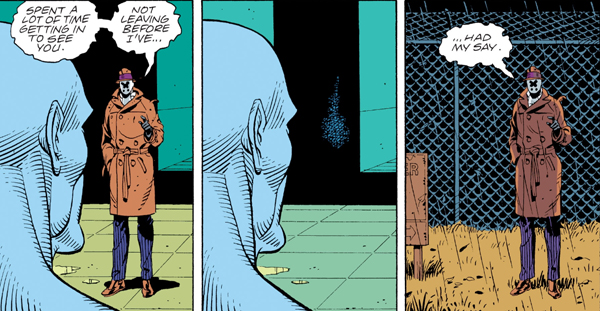

Comics artists absorbed the lessons of continuity filmmaking. If the hooks in films stand out by contrast with the overall smoothness and linearity of classic construction, something similar happens in comics. Here are three “continuity shots” from the Watchmen graphic novel, complete with obedience to the axis of action, reverse-angle cutting, and a “single” for emphasis on Rorschach’s reaction.

Even a match-on-action hook can be suggested, as when Laurie’s lifting a goblet on Mars “cuts” to her as a teenager lifting a dumbbell.

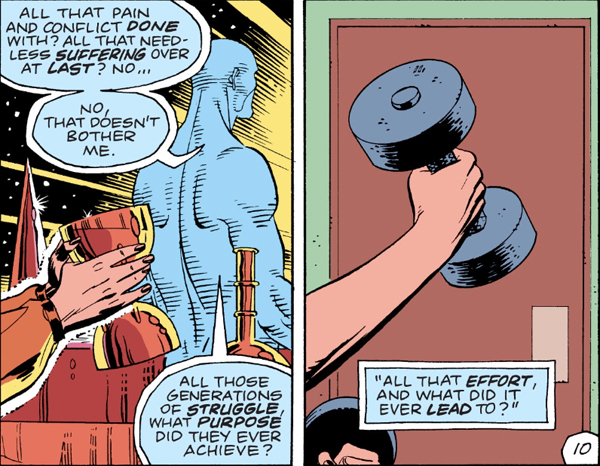

Graphic continuities and discontinuities can be motivated by science-fiction premises, as when Dr. Manhattan teleports Rorschach out of the facility. The sense of instantaneous change wouldn’t be so strong if Rorschach’s size and placement in the format weren’t kept constant.

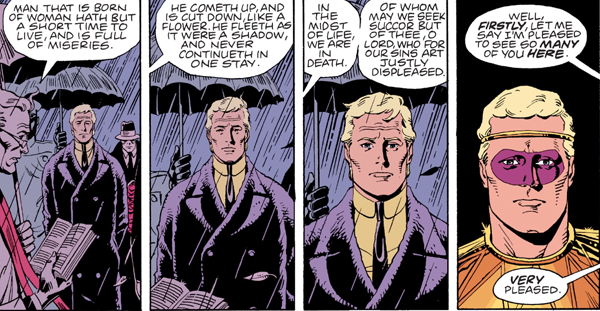

In a way, the graphic continuities are almost needed for the time-shifting transitions. A new angle on Adrian at the start of the funeral flashback below would be more confusing than the frontal close-up that completes a gradual enlargement of his face. The new costume and the “offscreen” dialogue cue us to a new scene.

To keep things tidy, the flashback ends with a foreground graphic match on Adrian, leading us back to the funeral.

As ever, popular narrative maintains symmetry and redundancy to keep the action clear. Here’s a more “staggered” but no less symmetrical foreground graphic match–used, again, for subjectivity.

The rectilinear staging evokes either a track-in (the first two panels) and a track-back (the last two) or axial cuts in to and back from Dr. Manhattan. (The Soviets called these in-and-out edits “accordion” cuts.)

So there are some rough equivalents between film editing and the principles binding comic panels, especially ones this jammed with information. But comics have unique resources too–ones that Watchmen‘s creators were well aware of. Dave Gibbons notes that he exploited techniques articulated by the great Will Eisner, “where you could, say, hold the camera’s point of view and have characters walk past it, or follow the characters through a scene acrosss a changing background, where you could echo panel compositions . . . .”

The echoes Gibbons mentions depend on the fact that the book page and its role in a two-page spread create a force-field that displays the story both as a timeline and a spatial array. Panels are at once phases of action and a simultaneous order of images, and the interplay of story information and pictorial pattern can become quite rich, even baroque.

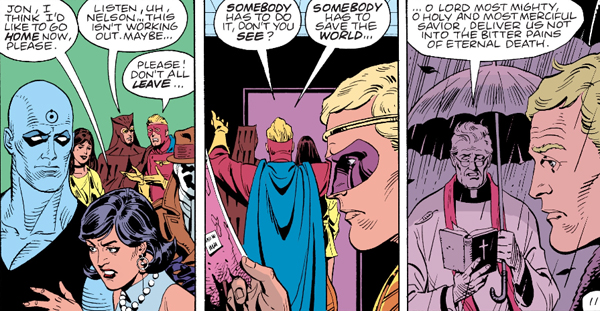

Consider when Rorschach rummages in the Comedian’s closet. Even if we could replicate the panels in a movie shot by shot, the page’s severe structure couldn’t be grasped as a simultaneous whole onscreen.

The echoes are striking. Panel 1, the establishing shot, is enlarged in panel 7 on the bottom row, as is panel 2 in panel 8. Each lower-tier mate is markedly closer than the top one, emphasizing the growing sense of discovery. Panel 2, with its sidelong strips of solid black, is echoed in panel 4 and panel 6 (a slight “pan” left from 4) and, with another enlargement, in panel 9, the climax. The color slabs (yellow/black, grey/purple) accentuate the repetitions and variations. The middle stretch, panels 3-6, forms a suite of variations as well (5 picks up 3, 6 picks up 4), while Eisensteinian cuts flip us back and forth across the axis formed by the straightened coat hanger. All the cuts are compass-point shifts, moving us in 90-degree multiples. The crisp geometry of the découpage renders the unhurried professionalism of Rorschach’s search, an effect accentuated by the snapshot imagery (no motion lines).

The effect depends in large part on the presence of all these images on the page at once. The alternation of shot scale and color fields can be discerned only by seeing the overall architecture of the page.

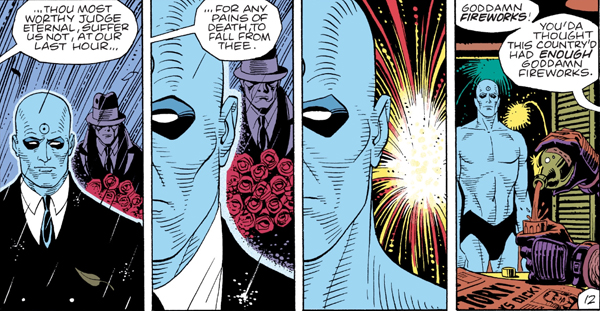

Panels 1, 3, and 5 build to the climax of the wide framing on the bottom as we pull farther back from Dr. Manhattan during his soliloquy. Panels 2 and 6, echoes of a close-up of the photograph, provide a sharp contrast to the landscape and emphasize the power of memory. That power is enacted in another variant of the hand image, as the young Jon Osterman arranges watch parts, like stars, on a velvet ground.

The page is one standard mid-size unit for the comics story, but the two-page spread is the next phase up. A continuous action can be spread across the open book, with echoes emerging. In the big fight scene, the shifting POV (occasionally objective, but also bouncing us among Rorschach, Adrian, and Daniel) is capped by symmetrical wide panels at the bottom of each page. The rose-tinted panels on the right page add their own fillip of pattern.

In a film such symmetries and variations unfold over time. We can make them apparent only through a “spatialized” analysis, spread out on the page like a comic-album layout. (Such were those pioneered by Raymond Bellour in the 1960s and 1970s.) In comics, these patterns strike us immediately, as a primary and palpable expressive vehicle. One-off devices like the graphic match can be sustained both on the screen and on the page, but each medium stamps its own structures on the flow of time.

There’s a lot more chop and change in the space-time continuum of the Watchmen comic than I can do justice to here. (Some pages run three time periods simultaneously.) But my main point should be clear. As usual, when we start to pay attention to the films and media artifacts that fascinate us, we always find more going on than we realized. Both movies and comics work on us so directly that their design subtleties can easily pass unnoticed. We can keep reverse-engineering them as long as we like, and we’ll learn a lot. And the creators can be very helpful guides about what to pay attention to.

I first became aware of Gregory Middleton’s comments by reading the review essay by Namwali Serpell, “In the Time of Monsters,” New York Review of Books (9 April 2020). I’m grateful to Serpell for calling my attention to the problem of cutting in the Watchmen series.

The essay is somewhat misleading in its account of match cutting, which is said to create “‘jumps’ rather than flows from shot to shot.” It’s actually just the opposite. The match cut creates continuity of time, space, and graphics between shots. It need not, as the essay claims, link two settings, and it’s not an alternative to a “splice cut,” which is a term with no currency I’m aware of. (A splice is simply the physical join between film strips, and it can govern any type of cut. Splices are increasingly rare with the dominance of digital editing.) The alternative to match cutting would be discontinuity cutting.

Serpell’s essay is worth reading for its interpretive dimension. She argues that for all the creators’ efforts to create strong images of minority heroes fighting white supremacy, there is a critical, antiheroic aspect to the original comic that isn’t picked up in the series. The sanctioned violence of Angela, Wade, and others is treated as unproblematically righteous.

I’d largely agree. Yet I’m not sure that the original book’s portrayal of superhero trauma (the result of the go-to source, childhood abuse) elevates these caped crusaders much. They seem to me best understood as part of that cycle of debunked superheroes we find in other 80s comics, notably The Dark Knight. Why would someone put on a mask to fight crime alone? What dignifies vigilantism? Are these “the heroes we need now”? These, we’re told, are deep questions, but they seem to me the tropes of a quickly standardized set of conventions. They signal a “new complexity” and “adult attitude” comparable to the romanticism of film noir and the cynicism about samurai ideals we find in Japanese swordplay movies. Bringing heroic genres low is itself a genre convention.

More broadly, I’d propose that the the storytelling strategy Serpell highlights is part of the common move within thematically ambitious mass-market movies to be strategically ambiguous. Creators, I’ve suggested here, often throw many things against the wall to see what will stick. They can then point to contradictory aspects which show balance. So yes, Angela tortures members of the Seventh Kavalry, but (a) they’d do the same to her; and (b) she’s driven by righteous vengeance for ancient wrongs; and (c) we want to make you a little uncomfortable with her vigilantism anyhow. Nowadays, it may be that what seem involuntary contradictions are deliberate efforts to have things many ways at once. This maximizes viewer outreach and gives critics fodder for debate. For another recent instance, see the previous entry on The Hunt.

The Dave Gibbons quotation comes from the supplement “The Phenomenon: The Comic That Changed Comics” available on the DVD of the Director’s Cut of Watchmen, 9:35-10:14.

Raymond Bellour’s “spatialized” analyses of repetition and variation can be found collected in The Analysis of Film (Indiana University Press, 2001). Some efforts of mine are in On the History of Film Style and in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (available for free, if patient download here), as well as in other material on this site.

Watchmen (2019).

Hunting Deplorables, gathering themes

The Hunt (2020).

DB here:

I recently participated in a Film Comment podcast with Nic Rapold and Imogen Sarah Smith. It was fun. Yes, The Hunt was involved.

And last month I posted a “blog lecture” for my seminar on Poetics of Cinema. Because it included references to classroom material, I thought it was too insular for general consumption, so I posted it privately. Encouragingly, some of our regular readers wrote to ask about accessing it, so today I’m putting up a more broadly-aimed version. Again, yes, The Hunt is involved.

We like to watch (and listen)

First and fast, some foundations. As Paul Krugman might say, wonkish ones.

Most basically, I’m interested in two questions: How do films work? How do they work on us? The first question, I think, can productively start with filmmaking craft and the norms that filmmakers work with in their historical situation. Within and against those norms, filmmakers create work that blends tradition and innovation. I’m interested in conventions–the conventional side of “unconventional” works, and the unconventional side of more apparently rule-abiding ones. I sometimes say I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

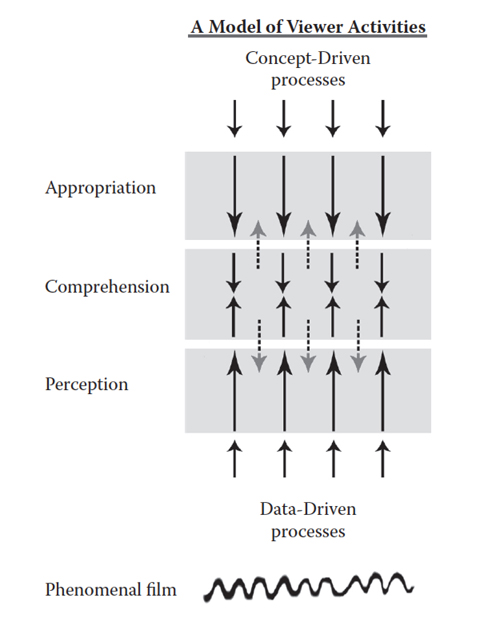

But asking how films work on us has driven me to posit a conception of spectators’ activities. After all, in any art it’s legitimate to try to explain how the design features of a work are shaped to elicit effects, ranging from perceptual and emotional ones to broader effects of comprehension and what I call appropriation. I assume that in every sphere “the beholder’s share” in watching movies is considerable, and active.

Using a common psychological distinction, I’ve argued we can roughly understand this process with a diagram, above.

The activity proceeds both “from the bottom up” via the fast, mandatory, specialized activities of visual and auditory perception. The process works as well as from the “top down” via more deliberative mental acts. Comprehension, typically of story patterns, operates in the middle. So you “just see” a man in tights walking across the shot. Thanks to story comprehension skills you “just see” Batman striding to face off against a crook. Thanks to your wider conceptual schemes, you can appropriate that as patriarchy in action, or the pain of vigilante justice, or a template for an action figure you might buy, or whatever. Where’s emotion? At all stages, I think.

And all these processes seem to me inference-based to some degree. In grasping artworks, even perception has an inferential dimension, going beyond the information given. Patches and contours on the screen are grasped as people, places, and things; sound waves are grasped as speech and music. The process is inferential because these perceptual conclusions are defeasible, as most illusions are. Things might be otherwise than they seem; we bet (fast, unreflectingly) that things are as they seem until other information pulls us up short. Similarly, story comprehension relies on skills of inference we’ve developed since childhood, built partly upon our social intelligence. And appropriation is obviously inferential, building hypotheses about the meanings and uses we can ascribe to film.

Perception and comprehension are strongly shaped by the film’s form and style. But as we go up from perception, the filmmaker’s power decreases and the viewer’s power increases. Viewers wield most power in appropriation, those top-down, concept-driven inferences that pull the film, or at least the viewer’s construct of the film, into wider projects.

Let’s think of appropriation as most basically using the film for myriad personal or social ends. That activity involves, for want of a better term, themes–ideas, categories, dualities, pop-culture memes, right up to wider beliefs about the world. Cultural processes, affecting the lower levels to some degree, are at work here most explicitly.

At this moment, when many people are sheltering at home, they are appropriating films for many purposes–to distract them, to entertain the kids, to learn more about health policy or the effects of pandemics. Fans, I assume, are seizing the pretext to binge on a saga they love, or check out a series they’ve put off. Online critics, pressed to turn in copy, are mustering their new listicles, recommendations of films to watch while we’re in lockdown.

This situation is just a special case of appropriation, of finding aspects of the film that can be recruited for purposes that may or may not accord with the filmmakers’ original intentions. No producer planned for Outbreak (1995) or Contagion (2011) to serve as audiovisual aids during a plague.

As my Batman example indicates, interpretation is a rich instance of appropriation, displaying how resourceful people can be in their inferential elaborations.

I wrote the book Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema (1989) as an attempt to spell out my ideas. I concentrated on two critical institutions, journalistic criticism and academic interpretation. But I think my claims could be applied to “amateur” critics and fandoms too. (This blog entry on Room 237 gestures in these directions.) Another article on this site, “Film Interpretation Revisited,” is a summary of the book, as well as a reply to critics.

So much for “the beholder’s share.” Can we go back to the “maker”? In a later section I’ll float some ideas about the place of thematics in relation to form and style. I’ll also consider how artists can anticipate and manipulate the appropriation process–a sort of meta-strategy to grab control higher up the chain.

Yes, spoilers for The Hunt are involved.

Interpretation, whys and wherefores

Interpretation seems to me to involve two tasks. First, there’s problem-solving: How should I interpret this film (or show, or whatever?) Second, there’s argument, or rhetoric: How should I make the case that this interpretation is worthwhile? Making Meaning has a lot to say about critical rhetoric, but I’ll concentrate on the problems interpreters set themselves.

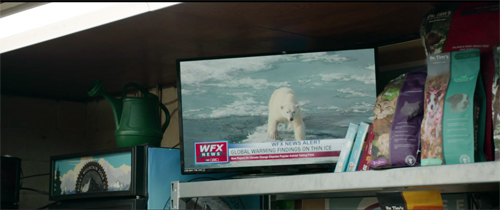

I assume that interpretation ascribes meanings to films. What sorts? I start with referential meanings (a big category including building the story world as well as tapping into real-world information, like specific times and places). In The Hunt, recurring TV images of polar bears struggling on melting ice floes nudge us to remember the climate crisis.

There’s an extra referential layer in the chyron, which expresses Fox-News style skepticism about climate change. That line helps confirm the right-wing ideology that supposedly permeates the quickee mart.

The other sorts of meaning I identify are more abstract. They include explicit meaning, usually given in language. In The Hunt, Athena expresses her disdain for the Deplorables whom she has gathered her friends to kill. She articulates a part of the film’s explicit meaning: The elite treat their social inferiors as prey.

There’s also implicit meaning, suggested through many cues, not just verbal ones. Crystal, the fierce fighter who confronts Athena at the end, is too laconic to speechify, and she never asserts that the underclass can be resilient and pitiless. But we are to grasp that meaning through her behavior–as the prey fighting the predator. Story comprehension feeds our interpretive move. By the end of the film we may take the polar-bear footage as implying that the Politically Correct hunters care more for these beasts than their vulnerable fellow humans.

Referential meaning, explicit meaning, and implicit meaning are typically under the control of the filmmakers. Clearly Craig Zobel, Damon Lindelof, Nick Cuse, and their colleagues want us to make the inferences I just made, along with many others. But it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that some implicit meanings escape the filmmakers. I’ll try to show later that filmmakers sometimes try to back up and frame their films to cover those unintended implications.

We can argue about some of these meanings. In The Hunt, Crystal recalls a childhood story of a race between a rabbit and a turtle. The rabbit lost through laziness, but he took revenge on the turtle by killing him and his family. The tale becomes part of a motif: Early in the film we see a video of a turtle humping a boot, while at the end we see a bunny hop into a gory kitchen.

After telling the story, Crystal declares she’s not sure whether she’s the rabbit or the turtle in the hunt. I think we’re supposed to think about whether the underclass (if it’s the turtle) can ever win more than a temporary victory. This sort of equivocation about implicit meaning is common in artworks. Indeed, the clash of implications encourages us to interpret them. The tactic might seem designed only for “difficult” films, but it’s surprisingly frequent in mainstream movies, as I’ll suggest later.

A fourth sort of meaning, I think, is what people have come to call symptomatic meaning. Here the film says more than it intends. It reveals, like a psychoanalytical symptom, an “unconscious” problem with the explicit and implicit dimensions put forth. (This is the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” which Susan Sontag discusses in “Against Interpretation” in relation to Marx and Freud.)

Critics may say that cheerful Eisenhower-era comedies betray anxieties about gender and identity. Some consider superhero franchises as unwittingly betraying a commitment to fascistic authority. From this perspective, Indiana Jones is less an adventurer than an imperialist. Symptomatic meanings leak out and can’t be contained. If implicit meaning is the filmmaker being more or less subtle, symptomatic meaning works behind the filmmaker’s back.

The Hunt is of course ripe for symptomatic interpretation, as I’ll mention below. However much its sympathies may seem to lie with the prey, it seems unable to avoid double-edged gags at their expense.

For all of these types of meaning, the process I posit is the same. The viewer maps, from the top down, concepts onto cues and patterns found in the film. Given the results of perception and comprehension, the viewer selects certain items to bear the meanings we bring to the task.

For example, I said that Athena articulates the predatory view of the oligarchy. Why did I pay attention to her and her words rather than, say, the layout of comestibles on the kitchen island? Because I have a rough but well-practiced mental schema for personhood. That’s more salient in building up a narrative than spotting bits and pieces of scenery. (These details can become salient, as the cheese-slicer will eventually, but the filmmaker has to make them so, as hand props or in close-ups or whatever.)

Making movies mean (but not like Zahler does)

The information in a film is most simply a flow of images and sounds. Perceptually I go beyond that information to recognize a person. Given that my person schema is furnished with properties like beliefs, desires, consciousness, and so on, I can build up a sense that Athena is stating her views on late capitalism.

Similarly, my repertoire of person schemas enables me to build up a sense of Crystal’s character, based on her appearance, speech, and actions. She too has beliefs (she’s being hunted), desires (she wants to survive), plans (she will fight), and attitudes (she scorns the sissified elites). She has character traits. In certain relevant respects, she’s like us and the people we know.

Filmmakers are practical psychologists. They know, from having consumed films as well as made them, how to highlight information and make it vivid and salient, so that we’ll lock in our concepts easily. For lots of reasons, we’re interested in other people, so that gives film artists an immediate purchase on using characters and their actions to convey abstract or general meanings.

For symptomatic interpretation, the same process holds. Character recognition and construction will be important for finding the flaws and failings of the film’s primary meanings. Of course, the symptomatic critic may “read against the grain” and look for less salient items that betray the film’s unconscious meanings. The fact that the climactic confrontation takes place in a kitchen could suggest that the filmmakers, for all their flaunting of strong women, are assuming a patriarchal ideology: Woman’s place, even as a killer, is in the home.

And the very end of the film, with Crystal strutting out as a fashionista, suggests that she has bought into the shallow values of the elite.

She’s not leading a revolution but killing her way to upward mobility.

I emphasize character as a site of interpretive elaboration because it’s so central to all critical schools, from fandom and journalism to the upper reaches of Academe. It’s not the only set of cues that get mobilized, though. Small details dropped in can serve too. A jar of Pickled Pigs Lips in a fake quickee mart reveals the sneering disdain of the hunters who’ve set up the display, but some viewers may find that it nudges us to mock trailer-trash taste.

The glimpse we get of the jars before the camera pans away seems to be the sort of cue aimed at “committed viewers,” willing to freeze the frame in playback to look for touches like this.

In Making Meaning, I talk about structural patterns as well, like journeys and character relationships, which prompt us to assign interpretations. There are stylistic cues too–not just the soundtrack with its dialogue and not just written language, but also camera movements, cutting, lighting, and so on. All these can be recruited to bear meanings. Critics often interpret a low angle as conferring power on a figure. Style, at bottom aimed at guiding attention and creating emphasis through the line of least resistance, can sometimes come forward and fill less concrete and fundamental functions–that of suggesting implicit or symptomatic meanings.

To wax wonkish again, Making Meaning suggests that the abstract meanings critics map onto cues are organized as semantic fields,which are in turn processed by assumptions and hypotheses. All that machinery is put into motion through schemas (prototypes and mental models) and heuristics (short-cut reasoning routines provided by social milieu or personal proclivity). The result is a “model film,” the film as interpreted by the critic.

You need lose no sleep over these matters. I simply argue that interpretation is a rational, fairly systematic process of informal reasoning operating within institutions that reward certain activities. Academics reward novel “readings,” while arts journalism does less elaborate versions as well. Even the “male gaze,” though stripped of its Lacanian baggage, has found its way into mainstream criticism (and the film industry).

Themes are memes, sometimes

“Themes come cheap,” I said one night in the seminar, rather flippantly. “They’re practically free.”

What I was suggesting was that themes are often obvious in a way style and overall form aren’t. They rise out at us unbidden. Before people watched The Hunt, they had been alerted to look for certain meanings. Mass media, critics, and the filmmakers had primed us to catch the big ideas the film was laying out.

That’s because films take meanings not only as effects but also materials. Films are made out of images and sounds, but they’re organized through form and style . . . and themes. If we look at it from the filmmaker’s standpoint, themes (like subject matter) can be treated as stuff to be worked on through technique. Like subject matter, they can float “obviously” on the surface, protruding a bit but still tugged by the flow of form and style.

In the Poetics Aristotle posited the category of “thought” as a component of tragedy. This term appears to mean something rather special. “Thought” isn’t what characters in drama think, or even what the playwright thinks. Rather, it’s what the characters say: their efforts to crystallize ideas and feelings in statements. The functions of thought in this sense “are demonstration, refutation, the arousal of emotions such as pity, fear, anger, and such like, and arguing for the importance or unimportance of things.”

The plot, Aristotle says, must create its effects through events and their patterning, “but these must appear without explicit statement, whereas in the spoken language it is the speaker and his words which produce the effect.” Thought in Ari’s sense spells out what action leaves tacit.

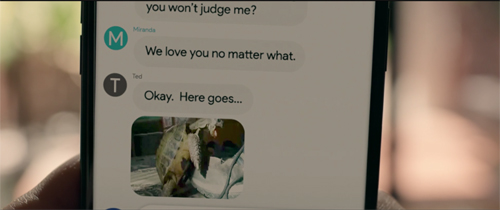

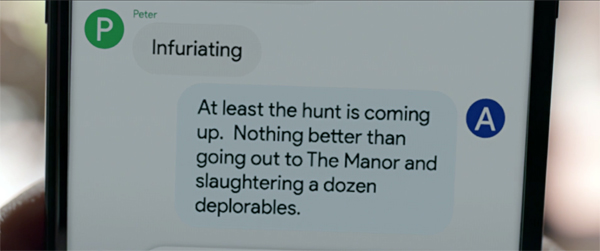

The Hunt does both. Ideas, images, and stereotypes circulating in US society have been taken by the filmmakers as already-fairly-processed material to be reworked into images and sounds and story. The explicit and implicit meanings critics build out from the film are the result of form and style shaping all this stuff into a perceptible, comprehensible experience. At moments, though, the oligarchs and the Deplorables state their sociopolitical views pretty frankly, as in the text message above. As Ari puts it, “they argue for the importance and unimportance of things.” Thought-as-theme is a prime cue for interpretation.

Themes can become not only material but also pattern. Certain genres of narrative are heavily “thematized” in that their organization is based on explicit or implicit meanings. Allegory is a classic instance. The Pilgrim’s Progress has a thematic armature, crystallized in the journey of Pilgrim to the Heavenly City. Ditto Animal Farm, which is usually taken as an allegory of the Russian Revolution. (Interestingly, The Hunt cites Animal Farm.) I expect that right now some grad students are writing papers about The Hunt as an allegory of working-class resistance.

Other heavily thematic genres are parables, fables, and the like. Crystal’s childhood story of the rabbit and the turtle becomes a parable of social injustice.

There are lots of ways that themes provide formal architecture. Some early films, like One Is Business, the Other Crime (1912), depend on thematic contrast. Here the fate of a poor man forced into thievery is juxtaposed with the law’s ignoral of a rich man’s transgressions. (Class resentment didn’t start with The Hunt.) Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) tries for a four-way thematic comparison/contrast of prejudice through the ages.

We also have “social cross-section” films, where stages of the narrative enact encounters with various institutions. As critics have noted, in The Bicycle Thieves(1948), Ricci’s search for his stolen bike brings him into contact with the labor union, the government, the church, and the bourgeoisie–none of whom are of help. A similar cross-sectional dynamic suggests social critique in Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu (1952) and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960).

Granted, in such modes, the film’s thematic skeleton can seem obvious. Other films leave meaning more free-floating, and even allegories can be less clear-cut than they may seem. (Think of Kafka.) I just want to signal, for the sake of comprehensive coverage, that filmmakers, like other artists, draw upon abstract ideas and meanings as materials to be reworked by their art.

To be good critics, we ought to be aware of both the materials and the transformations that come from them. I suggest this in a piece I’ve flagged before, “Zip. Zero. Zeitgeist.”

The filmmakers fight the power (of viewers)

The filmmaker’s power wanes as we move toward appropriation. But not completely. Filmmakers can use themes to manage a film’s reception.

For example, the Russian Formalist literary theorists floated the idea of the “biographical legend.” This is a public version of the artist’s life that can guide interpretations of the work. Boris Eichenbaum suggested that the Americans had one biographical legend for O. Henry, but the Russians built up a different one.

Critics and commentators build up the biographical legend in order to support interpretations, but the artist can contribute to the process. When Christopher Nolan tells us that as a youth he loved Star Wars, noir movies, and experimental fiction, he’s inviting us to put his own “intellectual blockbusters” in a certain perspective. He’s flagging certain cues, inviting certain mental sets, coaxing us toward certain inferences.

It’s not news. Contemporary critics took Douglas Sirk’s 1950s melodramas as glossy reflections of the superficial values of Eisenhower America. But when he was interviewed by Jon Halliday, he presented himself as offering a Brechtian critique of those values. Later critics eagerly started scanning the films for narrative and stylistic cues that suggested implicit meanings that subverted the suburban bourgeoisie. Chabrol, typically jaundiced, put it this way:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics with their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, not knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want.

If critics can use the artist to interpret the film, why can’t the artist use the critics to steer us toward preferred interpretations?

It isn’t just the filmmaker doing this. Auteur personas created by the filmmaker, the industry, and critical discourse can be seen as pushing us toward certain thematic interpretations.

Now to finish with a point I suggested above. It’s often in a filmmaker’s interest to avoid consistent and clear presentation of themes. I’ve come to think that many ambitious Hollywood films are systematically ambivalent about what they are “saying.” Rather than make a weighted, compact statement of “thought” in Ari’s sense, they scuttle and shuttle between alternate thematic possibilities. Or rather, they shuffle several disparate “thought” statements to counterbalance one another.

This has many benefits. It can stoke controversies. Is The Dark Knight in favor of vigilantism, or does it celebrate anarchy, or does it hold out hope of noble self-sacrifice? Nolan says:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Another benefit: If someone objects to one piece of thematic material, you can always say, “But look, we offset that with this…” It’s a way of widening the film’s appeal to many lines of thinking, while marketing the film as complex.

The creators of The Hunt claim to have aimed the film at smugly woke people like themselves in an effort to humanize the Other.

So we heightened the reality as much as we could. Some of the people who are being hunted are literally the guy with the tiki torch or a guy posing next to a dead animal; they’re two-dimensional stereotypical representations of what liberals see conservatives as. And then we had to do the same thing with the liberals. But there had to be one character in the movie, the hero who defied the conventions of stereotyping, who when you look at her you basically say, “Oh, she has an accent like this. She wears clothes like this. This is who she is.” And let’s be wrong about her. Let’s let the movie be about the cautionary tale of, here’s what happens when you get it wrong.

I think that the idea the audience wants Athena to be wrong about Crystal is maybe our own interior desire to say, “Maybe I’m wrong about my uncle who I’m screaming at at Thanksgiving. Maybe there’s a little bit more to him than meets the eye. Maybe I’m trying to put him in this specific lane because we have to choose a side, but maybe there’s many sides and there’s a little bit more nuance in the conversation.”

The caricaturing of the woke characters allows woke viewers to recognize the satire (and since woke viewers are likely to be educated, they know that satire exaggerates). Presentation of the Deplorables is exaggerated too, confirming that “There’s many sides.”

But there’s a kink for a symptomatic reading: Crystal may not be an actual Deplorable. We never learn her politics. She has been kidnapped in error, mistaken for a fierce Trumpist with the same name. So again the film manages to have it many ways. “Getting it wrong” here doesn’t mean disparaging a right-winger but rather not knowing whether somebody is right-wing or not. The real conversation is postponed because of a mistake. (No mistakes, no stories.)

I don’t mean to sound cynical about this. Art is opportunistic. We just ought to be aware that filmmakers can make the meta-move, using whatever means they can to close off interpretations that they might not prefer. Ultimately, since appropriation is top-down, they can’t control everything we might ascribe to the film. (See Room 237 again.) But there is a bit of a struggle there. Filmmakers will always try to join and constrain the hunt for meaning in their movies.

There’s a lot more to be said about interpretation, but I hope that readers will find something worth considering here. I may redo other Private seminar entries as public ones when time permits.

Thanks to Nic Rapold of Film Comment and Imogen Sarah Smith for a pleasant discussion. My citation of Aristotle on “thought” is from Stephen Halliwell, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill, 1987), 53. The reinterpretation of Sirk’s melodramas was undertaken in Jon Halliday’s interview book Sirk on Sirk (Secker and Warburg, 1971). The Chabrol quote is from Making Meaning (Harvard University Press, 1989), 210.

Phoenix (2014), one of the Christian Petzold films discussed in the Film Comment “At Home” podcast.

Light up with Hildy Johnson: The NYT viewing party for HIS GIRL FRIDAY

DB here:

Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott have had the excellent idea of picking a film for readers to watch over the weekend and inviting them to write about it. Here’s the viral viewing scheme.

I’ll be keen to read what the multitudes have to say.

If you’re interested, our site has paid homage to this classic several times. First I rehearsed a bit of history about how it snuck into university courses. Then I wrote an appreciation of it to accompany the release of the packed Criterion disc. (Find out why it’s called His Girl Friday!)

That disc release included a video essay in which I analyzed some things that fascinate me about this endless enjoyable movie. The video now accompanies the film on the Criterion Channel. There’s a vast trove of Hawksiana there as well, with expert comments and background information.

From its first edition in 1979, our textbook Film Art: An Introduction has used the film as a prime example of classical Hollywood storytelling. My colleagues Lea Jacobs and Vance Kepley have written a lot about it too. It’s the movie of our whole Wisconsin film studies program.

What more do you want? The 1940s. Hawks. Grant, Russell, the sublimely sincere Ralph Bellamy. His Girl Friday draws breakneck comedy out of how the fast-talking and quick-witted can trounce the fumblers and boobs. (Would that it happened in real life.) The whole carnival is played out by one of the greatest scramble of sharp-edged character actors in Hollywood history.

And thanks for reading the second paragraph.

Thanks to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Curtis Tsui, and all their colleagues at Criterion for making this Hawksapalooza possible.