Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Cine-Vienna

The Third Man (1949).

DB here:

En route to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, Kristin and I paid a visit to this wonderful city. We wandered around, stomped through museums, ate tasty food, and saw a bit of the city’s film culture.

Visiting venues

Our first stop was the Austrian Film Museum. Founded in 1964 by the avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka, the Museum has built up a collection of over 30,000 films. It contains a fine film theatre with features of the “Invisible Cinema” (above) that Kubelka and Jonas Mekas set up in Anthology Film Archive many years ago.

The Museum has been a pioneer in producing outstanding books and DVD editions devoted to an eclectic array of filmmakers (James Benning, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Straub/Huillet, Joe Dante). Exceptional as well are the Museum’s online offerings of films, clips, images, and paper documents.

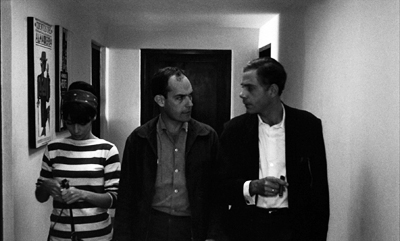

Our host was our old friend, the ebullient curator Christoph Huber. Here he is with his colleagues Alexandra Thiele and Jurij Meden.

We didn’t have a chance to visit the classic Stadtkino in the same neighborhood, nor did we check out the highly esteemed Austrian Film Archive. But I did mosey down to the Gartenbaukino, a big, beautiful modernistic venue.

Built as a ballroom that occasionally screened films, the Gartenbau was made a permanent cinema in 1919. In 1960, after being redesigned by Robert Kotas, it opened as a showcase for widescreen motion pictures.

It’s now said to be the biggest theatre in Austria, with over 700 seats. Note the rising curtain, said to be a rarity these days.

The Gartenbaukino is equipped to project not only digital and 35mm but also 70mm. Managing Director Norman Shetler notes that it was the first Austrian theatre to boast large-format projection (for Spartacus) and was adapted for Cinerama as well.

More recently, the Gartenbau reactivated its 70mm equipment to show The Hateful Eight. The Phillips DP70 projectors now screen wide-gauge classics like Lawrence of Arabia and The Sound of Music. Picture and sound were excellent for The Dead Don’t Die, so I bet 70mm shows here are fantastic. Like the Stadtkino, the Austrian Film Archive, and the Film Museum, the Gartenbau is a venue for the city’s annual film festival, the Viennale.

Prater, not so violet

Plenty of movies have been set in Vienna, most notably The Joyless Street, Merry-Go-Round, Letter from an Unknown Women, and Amadeus. But for movie nerds the most flagrant example is The Third Man (1949). And Vienna hasn’t forgotten what this movie did for its local landscape, not least the amusement park set within the vast and beautiful park known as the Prater.

Said to be the oldest amusement park in the world, the Prater ‘s entertainment sector contains attractions that are shiny and enjoyable old-school rides: roller coaster, loop-the-loop, tilt-a-whirl, haunted house. There are shooting galleries, ice-cream stands, and even a Madame Tussaud’s.

But of course the looming attraction is the great Ferris wheel that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and Harry Lime (Orson Welles) share during their ominous reunion. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who always expects Harry to try to throw his old friend out of the cabin.

The big wheel has been declared a site of European film culture and decorated with a more or less accurate image of the coy Lime.

My ride in the wagon was gentle and elating. I tried to replicate Harry’s POV on the “ants” below, whose lives, he says, can’t matter much.

A studio-based version of the Prater featured in the now mostly lost Josef von Sternberg film, The Case of Lena Smith (1929).

Oh, yeah–we also paid a visit to a street named for one of my favorite auteurs. See below.

Next up: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

For information about Viennese film culture, thanks to Christoph Huber, his colleagues, and the indefatigable Ted Fendt. Thanks as well to Norman Shetler and two staff members at the Gartenbau cinema. Christoph, by the way, is an exceptional critic. You’ll learn from reading his essays in Cinema Scope.

Cognitive film studies: The Hamburg Variations

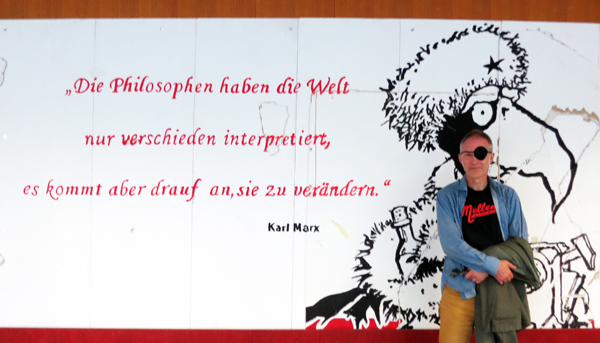

Lobby, Von-Melle-Park 9, Universität Hamburg, with Murray Smith.

DB here:

How many universities in the US would post a big quotation from Karl Marx in the lobby of a classroom building? (Answer: None.) But a cartoonish rendition of Marx’s killer app–the task of philosophy being not only to understand the world but also to change it–greeted the one hundred or so scholars attending the latest conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image last week at the Universität Hamburg.

How much we’ll change the world remains to be seen. What is clear now is that thanks to the superb organization of Kathrin Fahlenbach, Maike S. Reinerth, and their team, the SCSMI had a lively four days of papers, discussions, and excursions–as well as a screening of a strong film by a skillful director previously unknown to me. In all, every good reason to go to a conference.

Big questions, candidate answers

Carl Plantinga, Dirk Eitzen, and Kathrin Fahlenbach on the Hamburg Harbor cruise.

The range was huge, as usual, because this is a very diverse group. Our community, as I’ve mentioned in earlier reports, hosts film scholars, scholars of other media (television, games, internet), psychologists, and philosophers. Recurring questions include: How do viewers comprehend media presentations? What is the role of morality in film and television? How do practitioners conceive their craft? How do media present and trigger emotions? What appeals are specific to certain genres or historical periods? Not least: How may we construct good theories to answer such questions?

Three sessions ran simultaneously at each time slot, so I missed many good presentations. Kristin and I occasionally doubled up. Many of the talks will eventually become published papers, several in the Society’s journal Projections, so let me just highlight a few strands.

For those of us interested in how style interacts with narrative, there were several significant presentations. James Cutting, who has pioneered the use of Big Data techniques in scanning large batches of films, provided a compact account of how “sequences” (as opposed to scenes) displayed patterns of coherence and grouping. Karen Pearlman discussed her films, and James examined them to reveal fractal patterns in their rhythms–patterns that match the dynamics of footsteps, heartbeats, and breathing.

Two papers added to our understanding of the Kuleshov effect, much discussed on this site. Marta Calbi and her collaborators conducted EEG testing on spectators exposed to a Kuleshovian film scene, while Anna Kolesnikov, another member of the team, traced the contradictory versions of the “experiments” that Kuleshov and his students purportedly constructed. Both were exciting contributions to our understanding of Kuleshov’s legacy, which as the years go by looks more complex than we had thought.

Other papers on visual style included Barbara Flückiger’s tour of the staggering resource she and her colleagues have devoted to the history of color in film–a database of images from 400 films illustrating a range of technologies, periods, and genres. She has also mounted a magnificent array of tools for detailed analysis of color. (Significantly, she has taken the images from film prints, not video copies.) Here’s one of several stunning images she has taken from Helmut Käutner’s Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944, Agfa nitrate).

Stephen Prince, whose book Digital Cinema has just been published, surveyed the emergence of “deep fakes,” manipulated images that have no basis in reality but which are indiscernible from an accurate image. Steve was once skeptical that digital images would ever cut us off entirely from photographic reality, but now machine learning has managed to do it. Sped up by social media, the rise of unverifiable “records” creates what he called “an attack on an information system we call society.”

Hitchcock, everybody’s idea of a shrewd filmmaker (when will cognitivists discover Lang?), came in for his usual close treatment. Todd Berliner proposed five ways in which story information can be set up and paid off in a narrative, and he used Psycho as an instance of at least four of those methods. Maria Belodubrovskaya countered Hitchcock’s constant claim that he relied on suspense and not surprise. She showed that both single sequences and overall plots (e.g., Suspicion, Psycho) were heavily dependent on surprise effects.

In the first day, the range of the “humanistic” side of SCSMI was on vivid display. Malcolm Turvey asked whether the give and take of philosophers’ arguments converged on a consensus about truth, the way that much of science progresses. To illustrate the process, he considered the return of an “illusion” theory of images put forth by Robert Hopkins. Later that day, Jeff Smith used the cognitive theory of confirmation bias to show how characters in Spike Lee’s Clockers systematically misunderstand the story situation. The result, enhanced by genre conventions and a violation of some traditions of the detective story, enmeshes the viewer in the same error.

On the other end of the spectrum, there were papers mobilizing empirical research. Timothy Justus drew upon Lisa Feldman’s work in How Emotions Are Made to suggest that a biocultural account of facial expression should not rely too strongly on Paul Ekman’s classic argument about universal, basic expressions. More room, Justus proposed, should be given to cultural forces that build “emotion concepts” that filmmakers and viewers draw on.

A more hands-on empirical project was that coming from a team at Aarhus university. Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen posed the question: What if sympathy for a film’s villain varies with the personality of the spectator? As he put it, “If you are like a villain, will you like a villain?” So via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk the team ran questionnaires testing how personality types matched tastes in villains. Not to spoil their public announcement, I’ll just say that the results seem to confirm the belief that the most dangerous creatures on earth are young human males.

There was a lot more here than I can report, including provocative keynote addresses from Professors Anne Bartsch and Cornelia Müller (presenting work done with Hermann Kappelhoff). There was also a moving tribute to Torben Grodal, a central force in SCSMI and a leading-edge theorist applying evolutionary psychology and embodiment theory to traditional genre studies.

And, since SCSMI wants to understand how creators create, there was a film and its maker.

Without bullshit

In the past, our conferences have featured Lars von Trier and Béla Tarr, talking with us about their work. This time the guest was Thomas Arslan, a prominent “Berlin-school” director, who brought his 2010 film In the Shadows (Im Schatten) to the lovely Cinema Metropolis.

The film is a dry, hard-edged crime exercise. Trojan, fresh out of prison, comes to his boss to claim his share of the loot. In a tense confrontation he manages to get some of what he’s owed, but he’s now a target for elimination. He searches for a new robbery scheme and settles on the heist of an armored car. As usual, things don’t go as planned, particularly due to the intervention of a crooked cop.

Shot in a laconic style, In the Shadows took advantage of the Red One camera to produce remarkable depth in dark surroundings. (We saw it as a print because in 2010 theatres weren’t quite ready to show digital files. The print looked fine.) The drab locations complemented the anti-psychological impact of the story. Characters barely speak, the music is spare and almost subliminal, and the framing doesn’t accentuate the action expressively. In his post-film discussion, Arslan explained that the style grew out of the small budget and the rapid schedule. The result was a sort of modern B-film, avoiding the excess of CinemaScope and explosive chase sequences.

Arslan refuses to glamorize his gangsters, but he summons up sympathy for Trojan by minimal means. The protagonist is a solid, efficient professional, and he’s loyal to his boss until he realizes he’ll be betrayed. And as Hollywood screenwriters would remind us, you can sympathize with someone who’s been treated unfairly. I liked the unfussy handling of the story; it was a bit reminiscent of Rudolf Thome’s bare-bones Detective (1968). Arslan would be a good director to shoot a Richard Stark noir. “He does it without bullshit,” Arslan said of his thieving protagonist. It’s a good description of Arslan’s own technique.

SCSMI continues its tradition of merging humanistic inquiry with findings from empirical science. We can fruitfully ask questions that cut across traditional boundaries if we ground those questions in clear concepts and solid evidence. Our gathering next year moves back to the States–Grand Rapids, no less. More fun on the way.

Go here for earlier years’ coverage of SCSMI conferences.

On Richard Stark noir novels, see here and here. In the Shadows would fit nicely into my discussion of conventions of the heist film.

My own SCSMI contributions were two: a tribute to Torben Grodal and a little talk on contemporary women’s domestic thrillers (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, etc.). I may post the latter as a video lecture later this summer.

James Cutting lecturing at the SCSMI conference.

How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on the Criterion Channel

Street of Shame (1956).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Kenji Mizoguchi

DB here:

So much of contemporary film and TV takes pictorial space for granted. Yes, The Avengers: Endgame stuffs its frame with, well, stuff, but you’re seldom given time to see everything. Even in films not so dominated by CGI, if the the actors’ faces and gestures come across and you can hear the line readings, that’s pretty much enough. Most of the rest is there to fill out the very wide frame.

“Wait,” I hear someone saying. “Thanks to Steadicam, directors use camera movements to sweep through space all the time.” Yeah, that’s just my point: They sweep through. We’re following characters’ backs or fronts, not exploring space as such. Very seldom do we get a chance to probe what’s revealed, except in carefully wrought movies like Sunset (which tease you into trying to discern what’s not even in focus).

Moreover, today the pace of the editing is so fast, even in an “intimate” movie like Booksmart, that the actors’ faces dominate everything. For fifty years many directors have been “shooting for the box,” shoving their actors into close-ups that will read on TV, now on computers and smartphones. Like the endlessly moving camera, the big heads and the quick cuts refresh the image often enough to hold our interest in a distracting environment.

Granted, most filmmakers now supplement their fast-cut, rapid-pan close-ups with an occasional landscape shot that can look pretty, in a calendar-image sort of way. Overhead shots, now facilitated by drones, swoop us through the towering corridors of The City or across a swath of forest in a way that is undeniably impressive. This convention doesn’t count, for me, as pictorial intelligence unless somebody like Tony Scott does something, however nutty, with it.

I’m not against these stylistic choices per se; every style is valid if it’s pursued with imagination, rigor, and delicacy. Nor am I suggesting that the other extreme, so-called slow cinema, is inherently more virtuous. Long unmoving takes can be paralyzingly dull. Ozu made fast cutting just as “contemplative” as Hou or Tarr, because he knew how to design pictures.

It’s just that the norms of intensified continuity and the “free camera” have overwhelmingly dominated current practice. It’s worth remembering other ways moving pictures can be. One way to do that is to revisit film history, and the work of Mizoguchi Kenji is an ideal place to start.

His Street of Shame (1956) is the subject of this month’s Observations entry on the Criterion Channel. In it, I invite you to join me in attending a master class in staging.

The theme is Mizoguchi’s perennial one, that of the ways in which women succumb to or resist their oppression in a patriarchal society. We’re in the Dreamland brothel, where five–eventually, six–women are working at the very moment the government debates eliminating prostitution. Mizoguchi shows how they both cooperate and compete, trying to quit, deploying different strategies for managing their clients, and just getting by. It’s all done through what Mizoguchi called the “hypnotic power” of carefully choreographed images.

A personal note

In a way, Mizoguchi made me a film teacher.

During the week of 25 September 1969, what could you have have seen in Manhattan? I Am Curious: Yellow, La Chinoise, Closely Watched Trains, Miracle in Milan, Hell’s Angels ’69, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Midnight Cowboy, The Killing of Sister George, De Sade, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, One Second in Montreal, <—->, Take the Money and Run, Alice’s Restaurant, Medium Cool, In the Year of the Pig, Easy Rider, Putney Swope, and programs of Kubelka and Jack Smith movies. There were many double bills on offer: The Wild Bunch and Ride the High Country, Yellow Submarine and The Gold Rush, King Kong and The Lady Vanishes, Seven Samurai and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, Monterey Pop and Don’t Look Back, The Deadly Affair and Funeral in Berlin, Little Sister and Alice in Acidland, Lonesome Cowboys and Flesh.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

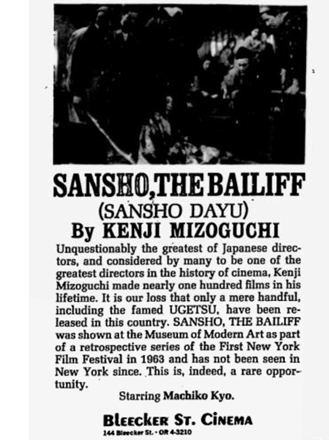

In the city for only a few hours, I didn’t go to any of those shows. There was yet another double bill at the Bleecker but I could catch only one title: not Lola Montès (I would see that in Paris a year later), but Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff.

As a teenager I had read books about cinema (Welles, Hitchcock) and in college I’d written movie reviews and participated in a film club. Now, newly graduated, I was teaching high school. The only Japanese films I’d seen were the Kurosawa standards our club programmed. Despite planning for a career in high-school teaching, I thought about film most of the time. In the pages of Film Culture and Movie I had read about Mizoguchi.

I came out of Sansho with tears streaming down my cheeks. I heard two young men in the lobby talking about the film. Did they go to NYU or Columbia or some such place? All I know was that they loved Mizoguchi’s long takes, as I did. Somehow, those takes had to be connected to the way the movie hit me. I thought something like: I’d like to study this sort of thing.

I returned to my apartment and began figuring out how to apply to graduate school.

Mizoguchi was still largely unknown, certainly unappreciated. The New York Times didn’t get around to reviewing Sansho until it resurfaced in a later run. Roger Greenspun made up for the neglect with a a gracious note.

“The Bailiff” is a film of breathtaking visual beauty, but the conditions of that beauty also change–from the etheral delicacy of its beginning (before the kidnapping), through the dark masses of the Bailiff’s compound, to the ordered perspectives of Kyoto and the governor’s palace, and finally to the spare symbolic horizons at the end.

In effect, it moves from easy poetry to difficult poetry. Its impulses, which are profound but not transcendental, follow an esthetic program that is also a moral progression, and that emerges, with supreme lucidity, only from the greatest art.

People talked that way then, with good reason.

Choreography all the way down

I didn’t see much Mizoguchi in the years following. There wasn’t much available. (And Ozu was unknown to us.) I did see Ugetsu and Street of Shame, though they didn’t grab me as fast as Sansho had. Fairly soon, though, New Yorker Films and Audio-Brandon made prints of other Mizoguchi titles available. I started using Mizoguchi films in my teaching, and the more I studied them the more I admired them. I was also inspired by critics Robin Wood and Noël Burch, who sought to explain the emotional and cinematic force of this filmmaker.

I began studying Mizoguchi’s films, traveling to Europe to see them all and make frames from prints. Eventually that work would inform my chapter on his staging in Figures Traced in Light. Although there he bested me two falls out of three, I think that discussion made some headway in analyzing his unique visual strategies. I tried to develop those ideas further in an online supplement to that chapter and in the blog entries “Secrets of the Exquisite Image” and “Sleeves.”

More skilfully and subtly than nearly anybody else, Mizoguchi arranges bodies in space to create powerful pictures. Yet his gorgeous shots aren’t just decoration. He never lets the images, elegant as they are, distract from the dramatic issues arising among the characters. The result, I argue, achieves the sort of “hypnotic power” that Mizoguchi claimed to seek.

In Mizoguchi, I suggest, a fairly dense image “becomes a story” as its elements start to mingle and separate out, letting our eye discover (with guidance) a drama as it emerges. A situation precipitates out of a rich mass of material, and the result is an accumulating tension that’s at once dramatic and pictorial. He evidently learned a lot from von Sternberg, but I think this thickening-and-release dynamic of story and style is reminiscent of Hitchcock or Lang as well.

The students were right: Mizoguchi is a master of the long take. The long take, he said, “allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.”

But we shouldn’t think of this technique in the sort of marathon-competition terms people apply to long takes nowadays. (The current example is Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night.) Today’s long takes are often virtuoso traveling shots. While Mizo made wonderful use of camera movement, he knew the power of stillness. He showed that you can just clamp the camera on the tripod (or the crane) and sculpt the action in front of it.

Among Mizoguchians, there are some who find his later films stylistically compromised. Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942; below) and Loves of the Actress Sumako (1947), with their far-off figures and impeccable, “all-over” compositions, merge austerity and density in ways almost inconceivable today.

Given this radical approach, his greater reliance on closer views in the 1950s work can seem a step backward.

But Mizoguchi was a pluralistic director from his earliest days forward. As I try to show in Figures, he fitted his visual design to the needs of a scene, and even the most severe films draw on diverse techniques. Street of Shame shows his endless resourcefulness in enriching three-shots and two-shots and singles. He found choreographic possibilities at every shot scale, with small gestures and glances becoming as important as characters shifting around the set. In the last shot of the last film he made, a single darting eye commands the image and carries the drama.

Given the sustained shot, Mizoguchi fills it and drains it, re-fills it and thins it out and channels it to a climax, all with a graceful, unobtrusive choreography always driven by the emotions pulsing through the scene. I go back constantly to Philippe Demonsablon: “He emits a note so pure that the slightest variation becomes expressive.”

Mizoguchi works in melodrama. Some directors, such as Sirk, take intense situations and amp them up. But Mizoguchi, like Stahl and Preminger, is always banking the fires. His style presents hot emotions in a cool way, betting that detachment and restraint give the emotions a sort of stark purity. If more filmmakers studied his work, who knows what kind of cinema we might have? I hope you have a chance to check in on this entry.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole fine Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts.

Street of Shame is also available on a generous Criterion Eclipse DVD set. Some years back Masters of Cinema series gave us beautiful Blu-ray transfers of many Mizoguchi films. The Street of Shame edition has a fine feature-length audio commentary by Tony Rayns. Alas, the set including the film has apparently gone out of print.

Robin Wood’s influential essay on Mizoguchi is “The Ghost Princess and the Seaweed Gatherer,” in Personal Views: Explorations in Film (Gordon Fraser, 1976), 224-248. Noël Burch’s revisionist account of Japanese cinema is To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), where chapter 20 is devoted to Mizoguchi. (The book is available online here.) Roger Greenspun’s review, “‘Bailiff’ Returns,” appeared in the New York Times (17 December 1969), 61.

For more on the place of Japanese directors in film culture, you can try this entry on Kurosawa and this one on Shimizu.

Street of Shame (1956). The sign reads “Cooperative Association Members” and “Confidential Membership.” Thanks to Steve Ridgely for the translation.

Politics and subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on the Criterion Channel

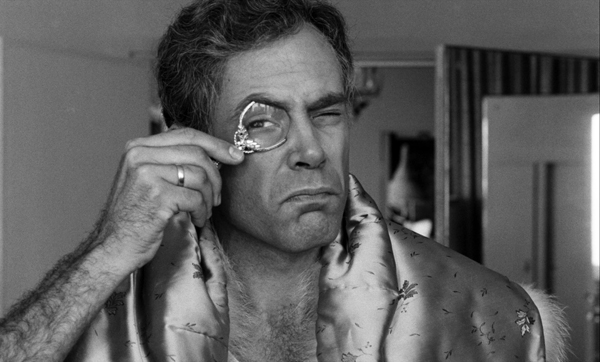

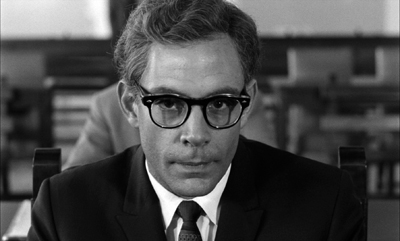

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Jeff Smith here:

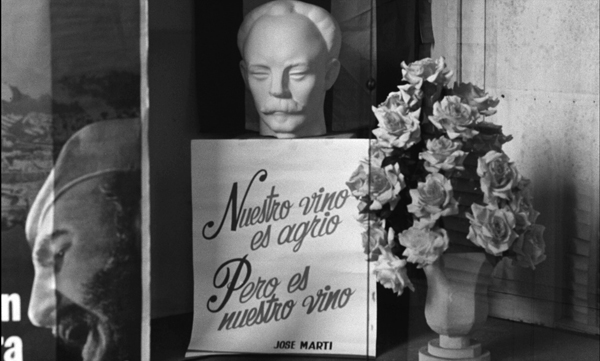

Early last week, the Criterion Channel posted the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art.” It was my turn at the plate with a video essay on Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. The film has long been a personal favorite due to its formal and political complexity. If the aphorism “the personal is political” rings true for you, then you owe it yourself to watch Memories of Underdevelopment. It is a post-revolutionary culture’s most fully realized depictions of the survival of apre-revolutionary mentality.

A Third Way for Third Cinema

Hour of the Furnaces (1968).

“Toward a Third Cinema,” the 1969 manifesto written by filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, remains an important touchstone in the history of global film culture. It captures the militant spirit that characterized post-colonial activism in the late sixties and early seventies. At one point, Solanas and Getino describe the camera as an “inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons” and the projector as a “gun that can shoot 24 frames per second…” (For the record, that less than a quarter of the speed of an M134 MInigun, which fires at a rate of 100 rounds per second.)

As advocates for the vital role guerrilla filmmaking could play in anti-imperialist struggles, Solanas and Gettino explicitly opposed “third cinema” to more established modes of film production. Of course, the big enemy was Hollywood. It represented a form of commercial cinema that was inextricably linked to the ideology of American capitalism.

More surprisingly, though, Solanas and Getino also condemned European art cinema and its attendant emphasis on individual personal expression. Although art cinema represented a step forward in terms of its attempt to create a non-standard language, it remained “trapped inside the fortress” in Jean-Luc Godard’s words. For Solanas and Getino, the French New Wave and Brazil’s Cinema Novo opened up new aesthetic possibilities. They offered the brio and rebelliousness of youth, yet fit neatly into established commercial distribution networks as the “angry wing” of a capitalist, bourgeois society.

Solanas and Getino practiced what they preached, however. Their ambitious 4-hour agit-prop documentary The Hour of the Furnaces remains a prototype of third cinema practice. The film is a collage of contrasting images and sounds. These juxtapositions often involve the kinds of associational editing and montage principles that Soviet directors like Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein used in their work. At one point, Solanas and Gettino intercut cattle and sheep being slaughtered on the killing floor of a meatpacking plant with ads for various products originating in Western capitalist societies. (See below and above.)

The comparison was about as subtle as the sledgehammer used to kill the cattle. But the message was clear. The global success of American products, like Chevrolets, depended upon the violent suppression of “underdeveloped” populations.

Memories of Underdevelopment’s critique of post-colonialism is no less incisive, but it’s much less didactic. At first blush, Alea’s film seems to be the kind of European-influenced art cinema that Solanas and Getino explicitly reject. Indeed, Alea even self-consciously gestures toward this tradition through his explicit citation of French New Wave films, like Hiroshima Mon Amour. These allusions are reminiscent of the kinds of cinematic quotations that Godard and Francois Truffaut embedded in their own films.

Moreover, Alea also creates the kind of depth of narration in Memories of Underdevelopment that became strongly associated with art cinema’s emphasis on subjective realism. Throughout the film, Sergio’s thoughts and feelings on the current state of Cuba are given to us via voiceover narration. Many of Sergio’s observations function as ongoing commentary on the symptoms of “underdevelopment” that define contemporary Cuban society. For instance, over shots of downtown shops and boutiques, Sergio notes that Havana is often called the “Paris of the Caribbean.”

Such a descriptor seems a double-edged sword. The comparison to Paris is a way of praising the vibrancy of Havana’s cultural life, its bookstores, museums, cinemas, and modern department stores. Yet the qualification “…of the Caribbean” highlights its isolation from true taste-makers and fashionistas in New York, London, and Paris. For anyone who doesn’t live there, Havana is, at best, a playground for rich tourists from Europe and America.

As a member of the Cuban intelligentsia, Sergio often seems an unusually perceptive social critic. Yet Alea’s creation of such a strong alignment with Sergio seems designed to test the viewer’s moral and political allegiance. As a repository of pre-revolutionary attitudes, Alea’s characterization of Sergio encourages us to ask why Havana should aspire to be Paris in the first place. In a society that seeks to eliminate class distinction, why would one strive for such elitism no matter how rich and storied its culture may be?

In employing a device that often fosters sympathetic engagement with characters, is Alea just as “trapped inside the fortress” as French New Wave directors are? Actually, Alea also seems determined to turn the purpose of character alignment on its head.

As an intellectual, Sergio possesses a great understanding of Cuba’s relation to the rest of the world, but he seems determined to ask the wrong questions about its future. Therein lies the character’s great tragedy. As novelist Edmundo Desnoes observes, “His irony, his intelligence, is a defense mechanism which prevents him from being involved in the reality.” There is no place outside the palace gates for those like Sergio. Yet in probing his place “inside the fortress” Alea also shows how it rots from within.

By turning the camera’s gaze inward, Alea navigates a path between the agit-prop documentary of Solanas and Getino and the formal adventurousness of an art cinema director like Chile’s Raúl Ruiz. He set out to examine the vestiges of bourgeois thinking in Castro’s Cuba, using Sergio as a “litmus test” for Cuban audience’s political sensibilities. If you find yourself sympathizing with Sergio, seeing him as a victim of the revolution…. Well, then you better check yourself before you wreck yourself. In posing such a challenge, Alea pulls off a pretty neat trick. He manages to create a “third way” in third cinema by merging the polemical aims of agit-prop with devices and formal structures of the art film.

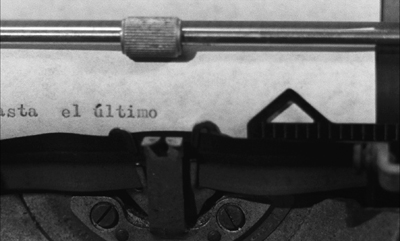

The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Cad

In a gesture that displays both self-consciousness and hubris, Edmundo Desnoes, the author of the novel that served as the source of the film, cast his hero as a writer. Although Alea changed much of Desnoes’ original story, this one small detail was something he preserved in his adaptation of the book. Indeed, just after Sergio has said goodbye to his wife and parents at the airport, we see him sitting at a typewriter. The sentence he writes – “All those who have loved and fucked me over up to the last moment have already gone.” – indicates both his anger in the moment and that his writing has more than a trace of autobiography.

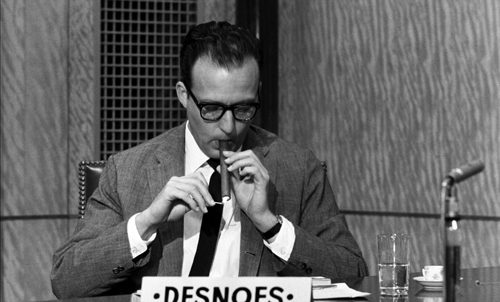

Sergio’s status as a writer encourages the viewer to see him as a surrogate for both Desnoes and Alea. This possibility is even reinforced in a scene where Sergio attends a roundtable discussion of “Literature and Underdevelopment” where Desnoes is featured as one of the panelists.

If Sergio truly is a surrogate for the filmmakers, then Alea shows some real guts in centering his film on an alter ego that is both politically reactionary and sexually predatory.

It is a mark of the film’s complexity that Sergio has certain very attractive traits even though he emerges as a thoroughly unlikeable cad. He is smart, cultured, and good-looking, for example. But he is also passive, cynical, and snobbish.

The dimension of Memories of Underdevelopment, however, that most clearly reveals Sergio’s corruption and moral rot involves his various relationships with women. Alea develops this idea throughout the film in terms of a Pygmalion motif: Sergio seeks to remake his romantic partners in the image of his first love, a German girl named Hanna.

In flashbacks, we learn that Sergio taught his first wife how to talk and dress, how to approximate a downmarket version of European elegance. Similarly, when Sergio initiates a romance with Elena, we see him taking her to bookstores and museums, trying to instill in her some appreciation for art and literature.

Sergios’ European ideals even pervade his sexual fantasies. After looking at an image of Botticelli’s Venus, Sergio imagines his housekeeper, Noemi, lying naked on his bed in a similar pose.

Similarly, when Noemi describes her Christian baptism to Sergio, he imagines it in images that seem culled from a hack romance novel. They embrace in a swoon, with their eyes locked, all wet clinging fabric and raging hormones.

Shot in slow motion, the episode is also accompanied by Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, a concert piece so familiar to most audiences that its inclusion borders on cliché.

It would be one thing, however, if Sergio’s sexual peccadilloes remained in the realm of harmless fantasy. More often than not, Alea depicts Sergio’s relations with women as episodes of exploitation and mental cruelty. A flashback to Sergio’s adolescence implies that the psychological roots of this misogyny lies in his first sexual experience as he and a school chum visit a brothel.

The transactional nature of the encounter is replicated in Sergio’s relationships later in life. After Sergio splits with Hanna, he marries Laura and is given a cushy job in the family business. He also lures Elena up to his penthouse with the promise of his ex-wife’s old clothes. In each instance, Sergio’s sexual or romantic relations with women are based on some notion of recompense: cold hard cash with the prostitute, the reward of a job with his wife, and haute couture with Elena, his new conquest.

As before, the exploitative undertones of Sergio’s relationships with women are reinforced by the film’s style. Sergio’s initial meeting with Elena is handled in a series of long tracking shots representing his optical point of view.

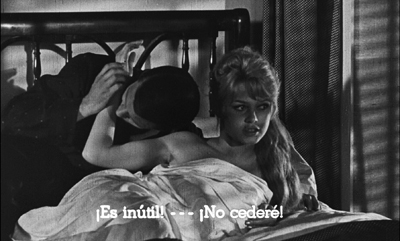

With his creepy pickup line, Sergio seems more of a stalker than a paramour. The troubling implications of this first encounter become more explicit midway through the film when Sergio literally chases Elena around his bedroom. The narrative rhyme with the earlier scene is made evident in Alea’s mobile long take, which once again represents Sergio’s visual perspective. Elena flirts coquettishly, sticking out her tongue at the camera.

But her discomfort in the situation becomes evident in her attempts to rebuff Sergio’s advances. Like the film’s use of voice-over, the moving pov shots spatially align the viewer with Alea’s unlikeable protagonist even as it implicates the audience in his victimization of Elena.

Later, when Sergio is put on trial for sexually assaulting Elena, he becomes the object of the camera’s unrelenting look along with the other petitioners. Here Alea uses a variant of the previous style. The longish takes remain. But where the previous shots used movement to suggest Sergio’s brazen advances toward Elena, the camera’s stasis within the courtroom reflects the perspective of the tribunal hearing the case. Alea cuts quite freely around the space. Still, he always returns to static close-ups of Sergio, Elena, her mother, her father, and her brother as they respond to the questions of offscreen interlocutors.

The scene proves to be the biggest challenge to the viewer’s allegiance with Sergio. He affects the demeanor of someone wrongfully accused. Yet, although the act itself is elided, Elena’s protestations beforehand and her tears afterward suggest that Sergio is probably guilty of the crimes for which he is accused. His voice-over, however, reveals his resentment toward the entire proceedings. The matter of his guilt or innocence is immaterial. What truly angers Sergio is the fact that someone of his lofty station endures treatment more suited to a common crook. He claims that he would never have faced charges during the Batista era. Sergio blames his ordeal on Cuba’s new political landscape. The judgment of his actions is more a matter of proletarian revenge rather than anything he has done.

It is easy to imagine some viewers feeling a pang of sympathy for Sergio. Jurisprudence often includes the presumption of innocence and Alea’s handling of the incident with Elena is ambiguous enough to have certain doubts. Moreover, Sergio has been impoverished by the government’s seizure of his property, something that makes his anger at Elena and her family seem more reasonable.

But what is especially striking in Sergio’s voice-over is the sense of entitlement he displays based on his previous social position. Alea seems to count on the fact that Cuban audiences in 1968 will recognize Sergio’s condescension as a symptom of pre-revolutionary ideology. His previous wealth, his education and culture, his status as an artist all sanction his satisfaction of his desires, even if that means taking the virginity of an 18-year old girl. In his characterization of Sergio, Alea not only reflects the broader influence of the French New Wave. He also revives a classic character type of French literature and cinema: the Parisian roué.

Mr. Schwitters Meets Mr. Alea: Mixing Modalities in Memories

The most oft-quoted line in Memories of Underdevelopment is not something said by Sergio, Elena, or even Sergio’s brusque friend, Pablo. Instead it is uttered by Alea in a director cameo. He appears in a scene where Elena performs in a screen test at ICAIC, Cuba’s central institute of film production. Alea (center, below) shows Sergio and Elena some of his work in progress, saying, “It’s a collage. A bit of this and a bit of that.”

Most critics have noted both the self-consciousness of the moment and its layers of meaning. The footage that Alea screens is made up of scenes cut out by Cuban censors under the Batista regime. It offers a fairly dismal portrait of Cuban film history as something mostly comprised of titles imported from other colonial empires, like the Brigitte Bardot vehicle Une parisienne. This is precisely the kind of cinematic legacy that Alea and other Third Cinema directors set out to counter.

Alea’s description of his film as a collage also has been interpreted as a clue as to how one should view Memories of Underdevelopment itself. More specifically, his comment captures some sense of the film’s complex visual texture, its mix of still photographs, television clips, newspaper headlines, and even comic strip panels.

It also describes the way Alea embeds documentary footage within his portrait of Sergio as a disaffected intellectual. To some extent, this strategy is simply a continuation of Alea’s digressive approach to narration. These interpolated documentary passages fit a larger scheme that also shows fragments of Sergio’s consciousness in fleeting fantasy images and elliptical flashback sequences. Yet these segments of Memories of Underdevelopment also sharpen its political edge. In effect, Alea injects the agit-prop spirit of The Hours of the Furnaces into his “second cinema” character study.

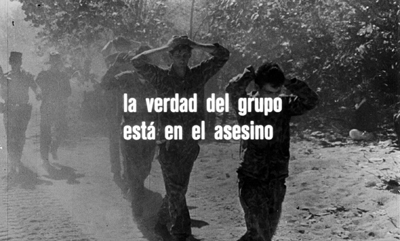

Consider the segment entitled “The Truth of the Group is in the Murderer.”

It is motivated as Sergio’s description to Pablo of the book he is currently reading. But it uses photographs and newsreel footage to explore the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the system of political repression and torture that existed under Batista. The title hints at the larger ideological point of the sequence, namely that the regime’s institutional framework served as a means of displacing and shifting criminal culpability away from its individual members. As a member of the bourgeoisie, Sergio is implicated in this dialectical arrangement between the individual and the group insofar as each part of it gives meaning to the whole.

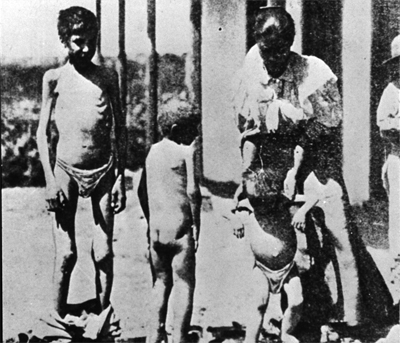

In a scene where Pablo gets his car ready for inventory, Sergio’s mind begins to wander. Alea then cuts to a series of still photos depicting hunger and starvation in Latin America.

In his voiceover, Sergio notes that the death toll from malnutrition exceeds the combat deaths of World War II. The sequence suggests Sergio’s insight into the problems of underdevelopment under capitalism. Alea’s imagery poignantly illustrates the disproportionate impact of such deprivations on society’s most vulnerable members, its children. This mini-documentary in Memories pointedly rebukes the colonialist regimes still present in Latin America by highlighting the cruel effects of such economic exploitation by First World powers.

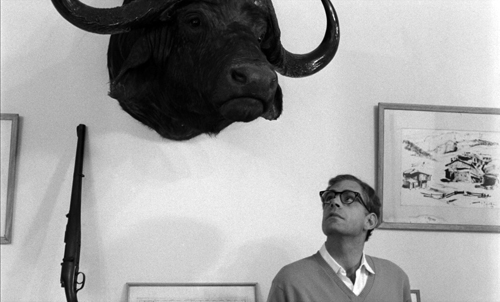

Similar sequences pop up in the episode labelled, “A Tropical Adventure.” The title refers to Sergio and Elena’s visit to Ernest Hemingway’s former home in Havana, which had been turned into a museum.

A series of photos shows Hemingway’s involvement in Spanish politics, particularly the civil war of the 1930s. A second series of photos depicts Hemingway’s relationship with his longtime servant Rene Villarreal. In his voiceover, Sergio hints that their master-servant relationship captured some of the vagaries of American imperialism. Sergio concludes that Hemingway must have been unbearable.

Sergio’s voice-over during these sequences offers one of the clearest statements of his character’s dualism. He conveys sympathy with Villarreal as a fellow Cuban and recognizes that Hemingway’s paternalism is itself an expression of colonialist ideology. Yet Sergio also seems to identify with Hemingway’s social position given his elite status as a rentier and aspiring writer. His trenchant observations about Hemingway’s relationship with his servant is an unwitting acknowledgement of how easily he could slip into the shoes of the great American author and adventurer.

In the battle for Sergio’s soul the “great white hunter” wins out as we see him hiding from Elena until she just gives up and walks away. Sergio’s condescending treatment of Elena is merely the flip side of the imperialist dialectic expressed by “the faithful servant and the great Lord. The colonialist and Gunga Din.”

Memories’ political sophistication largely derives from Alea’s sensitive treatment of his protagonist’s inner conflict. As a remnant of a previous historical moment, Sergio’s jaundiced perspective suggests that life under the Castro regime has simply substituted a new set of problems for life under the Batista regime. Indeed, for many viewers circa 1968, Alea’s look back at the era between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis might seem an endorsement of his hero’s nihilism and fatalism. Such was the case for several U.S. film critics who Alea disparaged later, claiming that their identification with Sergio caused them to mistakenly privilege the depiction of the artist’s self-interest over the needs of Revolution.

As Alea wrote more than a decade after Memories of Underdevelopment was released, “In Cuba, the Revolution is in power. This means that the conditions of struggle have changed.” Sergio’s struggle to find his place within post-Revolutionary Cuba becomes a metaphor for struggle itself. It is easy to celebrate the moment of triumph when a nation overthrows its oppressors. But a society’s problems don’t just disappear when you have regime change. Memories is the rare film that confronts the challenges faced in the aftermath of any revolution. It takes a hard look at the difficulties in remaking both a society and culture caught in the shadows of two global superpowers: the US and the USSR. In Alea himself put it:

It is to the spectator that the film should reveal the symptoms of possible contradictions and incongruities between good revolutionary intentions – in the abstract – and a spontaneous and unconscious adherence to certain – concrete – values belonging to bourgeois ideology.

Sergio simply becomes the vehicle through which Cuban audiences were encouraged to consciously grasp their own contradictions.

Alea’s insights here attest to his remarkable achievement in Memories of Underdevelopment. By exploring Cuba’s travails after Castro’s seizure of power, Alea knew that First World audiences might misinterpret the film. They might even use Memories to affirm their own imperialist identity. Yet this was not a design flaw. Instead, the film’s vulnerability would also turn out to be its greatest strength among domestic Cuban audiences. Alea’s use of cinematic devices to convey subjectivity imparts a simple but powerful lesson: the Revolution may be over, but revolutionary struggle never ends.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work. Also thanks to our colleague Erik Gunneson.

The text of “Toward a Third Cinema” is widely available on the Internet, as here.

The most useful resource for information on Memories of Underdevelopment remains the volume in Rutgers Films in Print series. The book contains a reproduction of the continuity script, a reprint of Edmund Desnoes’ original novella, contemporaneous reviews, and Alea’s own reflections on the film some twelve years after it was released.

The film was rereleased in 2018 after undergoing a 4k restoration. Reviews can be found here, here, here, and here. An interview with director Tomas Gutiérrez Alea can be found here. An excellent overview of Alea’s career in its entirety can be found here.

Here’s a complete listing of our Observations series on the Criterion Channel. Our installment on Hiroshima mon amour provides an intriguing comparison to this entry.

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).