Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Calm that camera!

Succession (2023).

DB here:

Thanks to our Wisconsin Film Festival, Ken Kwapis paid us a visit. Director of The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and many other features, Ken also has experience directing TV, notably The Office. He’s a generous filmmaker, and he radiates enthusiasm for his vocation. I took the opportunity to talk with him about camera movement in contemporary media. He taught me a lot, and what I’ve come away with I share with you.

Camera ubiquity, with a vengeance

In the early silent era, fiction filmmakers around the world discovered what we might call camera ubiquity—the possibility that the camera could film its subject from any point in space. This resource was more evident in exterior filming than in a studio set, so early films often display a greater freedom of camera placement when the scene is shot on location.

At the same time, filmmakers began realizing the power of editing. This technique offered the possibility of cutting together two shots taken from radically different points in space. Yet an infinity of choices is threatening, and some filmmakers, mostly in the US, constrained their choices by confining the camera to only one side of the “axis of action,” the line connecting the major figures in the scene. Different shots could cut together smoothly if they were all taken from the same side of the 180-degree line. The result was the development of classical continuity editing. The director was expected to provide “coverage” of the basic story action from a variety of angles, but all from the same side of the line. Classical continuity was in force for American films by 1920 and was quickly adopted in other national cinemas.

The one-side-of-the-action constraint was encouraged by the fact that much filming of staged action took place on a set, designed according to the theatrical model. The camera side of the space was behind an invisible fourth wall, like that in proscenium theatre. To some extent directors compensated for the limitation on camera position by fluidly moving actors around the frame, from side to side and into depth or toward the viewer. Still, the “bias” in choosing setups was reinforced by the increasing weight of the camera in the sound era, which made it hard to maneuver within both interior and exterior settings. Camera movement in a more or less wraparound space was possible, but it was usually very difficult. It commonly required a dolly or crane on tracks to prevent bumps.

Technicolor filming, with its monstrously big camera units, reinforced the bias toward proscenium sets, 180-degree space, and a rigid camera. So did the postwar vogue for widescreen cinema. But in the 1950s filmmakers were also exploring the possibility of lighter, more flexible cameras. The body-braced cameras often produced bumpy, slightly disorienting images but yielded a more “immersive” space that gave the story action immediacy and spontaneity. By the early 1960s, handheld camerawork was being seen in both documentaries and fiction films. At the same time, fiction filmmakers were gravitating toward more location filming. In addition shooting on location with portable cameras promised greater savings on budgets, an attractive option for both independent and mainstream directors.

Handheld shooting was becoming more common in the 1970s, when its problems were overcome by the invention of the Steadicam, first displayed to audiences in Bound for Glory (1976). This stabilizer permits the operator to move smoothly through a space.

The new device was more than simply a substitute for a camera on a dolly and tracks. Ken pointed out to me that the Steadicam encouraged the increasing use of the walk-and-talk shot showing two or more characters striding toward a constantly retreating camera. This proved to be an efficient way of covering pages of dialogue. Beyond that, the Steadicam became an all-purpose camera for filming any sort of scene.

Over the same years, directors embraced multiple-camera shooting—originally aimed at handling complex stunts—for every scene, and they recruited A and B cameras, often mounted on Steadicams, for ordinary dialogue scenes. In most cases, the B camera was mounted alongside the A, but with the B camera in other spots there was a certain erosion of the axis of action. Now a conversation may be captured from a greater variety of angles than classical coverage would favor. Filmmakers have replaced 180-degree staging and shooting with what’s called 250-degree coverage. In The Way Hollywood Tells It I drew an example from Homicide: Life on the Streets. A free approach to the axis of action is common today, as in this example from Succession (2023).

A rough sense of the axis of action is maintained, and there are matches on action, but our vantage “jumps the line” as well. Moreover, the camera is constantly moving within the shots. It’s panning to follow or reframe the characters, sometimes circling them or abruptly zooming, and always wavering a bit, as if trembling. What some Europeans call the “free camera” is very common nowadays, and Ken and I talked mostly about this creative option.

Eye candy

By now, many filmmakers have chosen to make nearly every shot display some camera movement independent of following moving characters. This tactic was noted and recommended in a manual by Gil Bettman (First Time Director, 2003). (Readers of The Blog know of my fondness for manuals.) “To make it as a director in today’s film business, you must move your camera” (p. 54). The risk is making the audience more aware of the camerawork than of the story, so Bettman adds:

A good objective for any first time director would be to move his camera as much as possible to look as hip and MTV-wise as he can, right up to the point where the audience would actually take notice and say, ‘Look at that cool camera move.”

Like cinematographers in the classical tradition, Bettman declares that the camerawork should be “invisible” (p. 55). By now, you could argue, the predominance of camera movement has made it somewhat unnoticeable. Ordinary viewers have probably adapted to it.

One factor that aids the “invisibility” of camera moves is the speed of cutting. If the shots are short, the viewer registers the camera movement but probably doesn’t have time to notice whether it’s distracting or not. The effect of this isn’t restricted to action scenes. Even dialogue scenes may catch conversations up in a paroxysm of character reactions, camera movement, and swift editing. Creating these rapid-fire impressions, it seems to me, is what a lot of modern filmmaking seeks to do, at least since the early 2000s. It’s sometimes called “run and gun” shooting. Here’s an instance from The Shield (2003), with sixteen shots in less than a minute.

Arguably, Hill Street Blues (1981-1987) popularized this look for the police procedural genre, when DP Robert Butler urged his team to “Make it look messy.”

This sequence and the Succession passage points up another factor. Knowing that their films would ultimately be displayed on TV, some directors began “shooting for the box” by using tighter shots and closer views. TV directors such as Jack Webb were already working in this vein of “intensified continuity,” and many others had started their careers in broadcast drama and accepted the impulse toward forceful technique. Television has long demanded that the image seize and hold viewers, likely sitting in living rooms and prey to many distractions. Fast cutting and constant camera movements keep the viewer’s eye engaged. No surprise, then, that our TV programs present a fusillade of images that make it hard to look away.

Constant camera movement has another benefit. Many camera movements tease us. The start of a shot suggests that the camera will bring us new information, so we must wait for the end. Filmmakers love a “reveal,” and even a small reframing can suggest the camera is probing for something new to see. By now, however, filmmakers can play with us and use camera movement to flirt with our attention: the shot can begin with a clear image but drift away to conceal the main subject. I first noticed this almost maddening stylistic tic in The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), but it crops up occasionally elsewhere. In one scene of The Shield (2006), the camera slides behind a character, finds nothing to see, and slides back.

The peekaboo reframing would seem to throw the viewer out of the story in just the way that worries Bettman. I’m inclined, though, to think that it is part of a general, and fairly recent, expansion of viewers’ tastes. Self-conscious technical virtuosity has long been an attraction of mainstream filmmaking, and audiences have responded with appreciation. Think of Busby Berkeley or Fred Astaire dance numbers, or the railroad junction scene in Gone with the Wind. I suspect that many members of today’s audiences now happily say, “Look at that cool camera move” and don’t mind being pulled out of the story. (I’d say, though, that they aren’t being pulled out of the film, but that’s matter for another blog entry.)

This tendency would accord with what Bettman calls the taste for eye candy. For him, this seems to consist of bursts of light or color, usually produced by camera movement. More generally, I think audiences would consider impressive sets, striking costumes, and good-looking people to be eye candy. And now, I suspect, flashy camera work counts as eye candy too. The case is obvious with the showboating following shots in Scorsese and De Palma, but I think it applies to the jagged, in-your-face techniques seen in run-and-gun sequences. Advocates of the silent film as a distinct art never tired of insisting that cinema was above all pictorial. “The time of the image has come!” thundered Abel Gance. It took a while, but now that people compete for bigger home screens we have to admit, for better or worse, that everybody acknowledges that film is a visual art.

Many flies on many walls

Most moving shots today don’t utilize the Steadicam, whose usage needs to be budgeted and scheduled separately. The run-and-gun look is well served by modern cameras designed to be handheld. DPs and operators know that a wavering, even rough shot is acceptable to most modern audiences, and filmmakers seem to assume that handheld images lend a documentary “fly-on-the-wall” immediacy to the scene. In addition, wayward pans, swish pans, and abrupt zooms are felt to enhance that sense that we’re seeing something immediate and authentic. (Flies are easily distracted.)

Problem is, this approach is far from what a real documentary film looks like. True, the individual images might be rough, but their relation to one another is quite different from those in a documentary. For one thing, they occupy positions that documentary shots can’t achieve. Shot B may be taken from a spot we’ve just seen to be empty in shot A, as in the sequence from Succession. As Ken put it, “There’s no such thing as a reverse angle in a documentary.” Or shot B may be taken from a very high or low angle, where a camera is unlikely to perch, as in this passage of The Shield (2007) which hangs the camera in space peering through a railing.

Sometimes shot B will represent the optical viewpoint of a character, which is unlikely in an unstaged documentary. Putting it awkwardly, the free-camera style achieves a greater degree of camera ubiquity than we can find in a standard documentary. (Years ago, I made this point in relation to The Office.)

For another thing, the flow of run-and-gun shots always captures the salient story points. A documentarist, with one or two cameras following an action, is still likely to miss something significant (and to cover the omission with elliptical editing and continuous sound). But the modern method offers its own rough-edged equivalent of classical coverage. The action remains comprehensible. Sometimes the camera will even wander off on its own to frame something the characters aren’t aware of, providing a modern equivalent of classical “omniscient” narration.

What we have, I think, is a modern variant of the one-point-per-shot mandate of traditional editing, but featuring shots of that evoke greater “rawness” than studio filming did. And maybe it’s not as modern as we think. Here’s a sequence from Faces (1968), complete with walk-and-talk, or rather stagger-and-talk, as well as camera ubiquity and matches on action that would be difficult in a documentary.

I’d argue that John Cassavetes, much admired by filmmakers who followed, supplied the prototype for today’s run-and-gun look. Admittedly, it’s been stepped up; I suggested in The Way Hollywood Tells It that intensified continuity has been further intensified.

Nervous energy

Intensified how? Apart from all the swishes and zooms and focus changes, some bells and whistles aim to enhance the sense of “energy” attributed to the style. The peekaboo framings I mentioned would be one instance. Here are some others.

The shot, distant or close, which simply trembles. Let’s call it the wobblecam. It suggests the handheld shot, but it’s brief and seems shaky just to evoke a sort of vague tension. Wobblecam shots are so common now that entire scenes are built out of them, as in the Succession clip.

The arc: In filming TV talk shows, how do you keep viewers glued to the screen? One option is what a 1970 manual calls the arc. Here the camera travels in a slow partial circle that refreshes the image gradually. The framing reveals constantly changing aspects of the panelists and is a nice change from master shot/ insert editing. I remember this as common in 1950s programs.

The “roundy-round” (thanks, Ken): This extends the arc to 360 degrees, circling around one or more characters, urging us to watch for bits of action or dialogue—usually timed for maximum visibility. It’s also used to convey a character at a loss, say mystified by which way to turn, or characters embracing (whoopee). The technique can be found sporadically before the 1990s, when it becomes quite common. Ken pointed out that the roundy-round was extensively used on E. R. to underscore time slipping away during life-and-death surgery.

The “roundy-round” (thanks, Ken): This extends the arc to 360 degrees, circling around one or more characters, urging us to watch for bits of action or dialogue—usually timed for maximum visibility. It’s also used to convey a character at a loss, say mystified by which way to turn, or characters embracing (whoopee). The technique can be found sporadically before the 1990s, when it becomes quite common. Ken pointed out that the roundy-round was extensively used on E. R. to underscore time slipping away during life-and-death surgery.

The slider: The enhancement I find most distracting is the camera’s slow leftward or rightward drift while filming static action. Usually it’s a master shot, but it doesn’t have to be, and it can sometimes interrupt a series of close views. Unlike the wobblecam, this is more teasing because we’re used to such a shot revealing something. It doesn’t, but I think it holds out the promise and keeps us watching.

Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema I came to realize that supply companies created lighting and camera devices designed to meet the developing needs of filmmakers. Thanks to Ken, I learn that this tradition continues. You can buy or rent gear that will enable arcs, roundy-rounds, and the slider (right). Both in technique and technology today’s Hollywood is a continuation of yesterday’s.

If a director constantly relies on camera movement, there’s no reason to object. The elegant moves of Ophuls or Mizoguchi or of McTiernan in Die Hard provide the sort of continuous engagement and ultimate pictorial payoffs that justify the technique. My examples illustrate more gratuitous camera moves, choices that “add energy” but once they’ve become conventional, seem wasteful. Usually, they reveal nothing and end up minimizing the power of a gradual reveal when it comes along.

But who am I to complain? Film styles change under production pressures and artistic inclinations. As a student of film history, I have to study what’s out there. Still, run-and-gun remains only one option. There are still lots of films and shows, like Tär and The Woman King and Barry, that rely on rigid camera setups and discreetly motivated movements. (Ken’s Dunston Checks In (1996), shown to an appreciative crowd at the festival, is a good example.) Another alternative is providing precise shot breakdowns that feature unusual “eye-candy” angles, as in Better Call Saul’s views from inside mailboxes and gas tanks. That trend constitutes another way to expand options within camera ubiquity. There are also the long-take films in which complicated camera moves preserve the patterns and emphases of classic continuity. (See the discussion of Birdman.) And then there’s the effort by Wes Anderson to go in the other direction, to submit to constraints far more severe than classical shooting—an austere refusal of camera ubiquity.

I must ask Ken about all these options too. Next time, I hope.

Thanks to Ken Kwapis, who enormously expanded my sense of the practical choices available to the filmmaker.

The TV production manual discussing the arcing shot is Colby Lewis, The TV Director/Interpreter (New York: Hastings, 1970), 131-132. Other mobile framings are reviewed in the same chapter.

For examples of filmmakers believing that the rough-edged style is like documentary shooting, see remarks on Succession in Zoe Mutter, “Fury in the Family,” British Cinematographer and Jason Hellerman, “How Does the ‘Succession’ Cinematography Accentuate the Story?” at No Film School. Butler’s comments on Hill Street Blues are quoted in Todd Gitlin, “’Make It Look Messy,’” American Film (September 1981) available here.

You can feel the thrill of silent-era creators and critics in realizing the possibility of camera ubiquity. Dziga-Vertov celebrated the power of the Kino-Eye to go anywhere, while Rudolf Arnheim saluted cinema’s ability to provide unusual angles that bring out expressive qualities of the world. What would they make of a shot like this below?

Better Call Saul (2015): Extremes of camera ubiquity.

Older, but wiser?

Calais Pier (J. M. W. Turner, 1803).

Kristin here–

Over the past three years, starting early in the pandemic, I have found a soothing and edifying occupation which one can indulge in at home: doing online jigsaw puzzles. Mostly I choose ones with images of ancient Egyptian places and artifacts and of my favorite painters. Having exhausted the available Botticelli, Bruegel, Bosch, Van Eyck, and others, I decided to try J. M. W. Turner, whose work I was somewhat interested in. Doing puzzles, I realized, was a way of concentrating on their details, almost a form of analysis. I became quite fascinated, not to say obsessed, with Turner’s work. I’ve been reading a lot about him as well, since he’s a compelling figure for many reasons.

One of these is that about two thirds of the way through his long career his style began to change radically. He gained a reputation early on for detailed, realistic landscapes and seascapes such as, to give it its full title, Calais Pier, with French Poissards preparing for Sea: an English Packet arriving (he was fond of long titles). It was exhibited at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition in 1803, when Turner was twenty-eight years old. His first oil painting to be in the exhibition had been Fishermen at Sea, seven years earlier (1796), and he had exhibited watercolors starting in 1790, when he was 15. Soon he was gaining fame and came to be considered by most as the greatest English painter. For decades his paintings commanded higher prices than those of his contemporaries, and he attracted a number of wealthy patrons who collected his work. He became the richest artist in Britain (a fact glossed over in Mike Leigh’s 2014 film, Mr. Turner).

During the 1830s and especially the 1840s, Turner’s style became less detailed and more abstract, emphasizing color and light rather than the subject, as in Approach to Venice, below, exhibited at the RA in 1844. He was 69 years old. He lived until 1851, dying at 76, and exhibited paintings of this sort until the year before his death.

This change caused many admirers and collectors to revise their opinions of the artist. Had his aged hands become unable to hold a brush steadily? Was his eyesight going? Was he more than a little touched in the head? Or had old age endowed him with some sort of visionary insight, as his most loyal supporters argued? “Late Turner” became a matter of controversy, with changing attitudes toward his challenging style continuing until the present. In the past few decades, one book and two exhibition catalogues have tackled the subject: the Salander-O’Reilly Galleries catalogue, Exploring Late Turner (1999),the Tate Britain catalogue, Late Turner: Painting Set Free (2014), and Sam Smiles’s The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner: The Artist and his Critics (2020).

This controversy reminded me of discussions that sometimes crop up among film fans and scholars. Are the late works of a given filmmaker greater than those what came before? Does age confer wisdom or philosophical resignation or a fear of mortality or some other kind of new understanding that is reflected in artworks in a stylistic or thematic fashion, creating a distinctive late period? I believe we do tend to believe this of artists, including filmmakers (primarily directors). Most audiences would probably think a retrospective of the later films of Yasujiro Ozu, say, from Late Spring (1949) on, to be as logical–maybe more so–than a series of highlights drawn from the surviving films of his entire career. The same might be true of Agnès Varda or Ingmar Bergman or other much-admired filmmakers with long working lives.

Let’s return to the career of Turner to see if there might be problems behind this assumption.

The Old Man and the seascape

Turner was well aware that he was a great painter, perhaps the best the UK had ever produced and quite possibly would ever produce. He was concerned that future generations should be kept aware of that. In 1848, three years before his death, he sought to guarantee that his legacy would last by revising the last of a series of wills, leaving all the finished paintings still in his home studio/gallery to the nation, on condition that a section in the National Gallery be given over to his work. Upon his death, his relatives contested the will, seeing these valuable objects slipping away while they were left with paltry sums of money.

After a five-year court case, the sage and fortunate judgment (fortunate for us, at least) was that it was impossible to tell which of the paintings were finished, so that everything in the gallery should be part of the bequest. This meant that hundreds of finished and unfinished oil paintings and tens of thousands of finished watercolors, unfinished watercolors, about 300 sketchbooks, casual sketches, studies, doodles, annotated train schedules (handy for following his many sketching travels), and paint equipment and supplies went to the nation. Most of the Turner Bequest, including abut 60% of his entire body of (finished?) oil paintings, is now in the Tate Britain, apart from several in the National Gallery. Most of the finished (?) watercolors are there as well.

At the time, as more and more of these paintings, finished or not, were cleaned, framed, and exhibited, for decades new Turners appeared before the public–almost as if he had never died. This included, of course, some of his older finished paintings that he had failed to sell or had deliberately held back or even bought back to represent his art to future generations. One such was that favorite of the British people, The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838 (1839), for which he had refused a fabulous offer of five thousand guineas, more than ten times the usual price of oils by prominent painters of the day. He was 64 at the time. In that same year’s exhibition at the Royal Academy, Turner presented Ancient Rome: Agrippina Landing with the Ashes of Germanicus (see bottom). These two finished paintings demonstrate that Turner had not lost his physical or mental ability to paint very well indeed. Both were part of the Turner Bequest to the nation. (We know which paintings were finished and given titles by Turner largely if he exhibited them at the RA or in his own gallery, or if he sold them.)

Turner’s plan has succeeded spectacularly, and admiration for the artist quickly revived and has remained high ever since. (Since April of last year, his youthful self-portrait and part of The Fighting Temeraire have occupied the verso of the English twenty-pound note.)

The creation of a gallery devoted to his work, however, was slow to be accomplished. It took the formation of the National Gallery of British Art in 1897, later the Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain, plus the building of a new wing onto Tate Britain, finally accomplished in 1987 when the Clore Galleries extension was opened; it displays the large number of oils in rotation. Some oils and watercolors from the Bequest are now in the National Gallery and the British Museum.

When French Impressionism became an international sensation later in the century, some patriotic British art historians and critics pointed out that Turner had been a forerunner of the style. The claims gradually grew, with Turner touted as having used many of the Impressionists’ techniques years before they did. Ultimately some critics went completely overboard and declared that Turner had done everything the Impressionists did. The French were not amused, but the idea has lingered on.

Similar claims were made well into the twentieth century. Turner had invented Impressionism, then abstract art, then Expressionism, and then Abstract Expressionism. These claims were based partly on his finished later work, but also on the huge number of undated, untitled, and unfinished pieces like the one above. (It was not named by Turner, who didn’t expect anyone else ever to see it, but is called by the Tate Sea and Sky and also called Rain Clouds, estimated date 1845). Often removed from sketchbooks to be sold as individual paintings, the most preliminary of sketches ended up much later being shown in exhibitions simply as artworks, taken out of their original contexts. From generation to generation, he could remain “Turner, our contemporary.” How had he envisioned all these modern techniques? Presumably because of the deep understanding of a genius reaching old age.

All this culminated in 1966 when the Museum of Modern Art put on an exhibition, “Turner: Imagination and Reality,” mainly based on unfinished works. The paintings were taken out of their elaborate carved and gilded wood frames, put in new, simple ones, and hung in austere galleries. The exhibition was a huge success. When one of the curators was asked why a museum dedicated to modern art would present an exhibition centered on a painter who had been dead for over a century, he responded, “Because we know a modern painter when we see one.”

Since the 1980s the pendulum has gradually swung the other way. Thorough historical research on the artist’s context by Turner scholars has revealed him as an artist not of the twentieth-century world but of the modern world of his own day. He reacted to the Industrial Revolution with enthusiasm, integrating factories, trains, steamships, and other innovations into his works, mostly famously Rain, Steam and Speed (in 1844, when he was 69), a depiction of a train racing toward the foreground. As a painter primarily of landscapes and seascapes, he was fascinated by all aspects of the natural world and had many friends who were making the major scientific discoveries of the age in a wide variety of fields, including Michael Faraday and Mary Somerville.

Most of his “abstract” sketches and studies, like the one above, were attempts to capture the movements of clouds, storms, waves, and any number of other natural phenomena, often based on his knowledge of the revelations of scientists. Presumably they served as reference images for potential use as details in future paintings. The obsession he developed with pure color did not arise from an elderly man’s poor eyesight or an uncanny prediction of artistic trends to come. All his adult life he voraciously read theoretical treatises on painting, and the 1840 translation into English of Goethe’s Theory of Colours had a profound influence on him. His own copy, annotated with both approving and argumentative comments, survives. John Constable, both Turner’s rival and his friend, commented that he had “a wonderful range of mind.”

Smiles’s book The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner, mentioned above, is entirely devoted to tracing the claims about Turner’s late period being a compendium of practically all future modernist movements of his and the following centuries. Smiles used historical research to trace how the artist’s life was affected by the contemporary events of his own day and the influences that other artists and writers had on him. He explains how such factors were the causes of his changed style. Smiles sums up some of the main problems with the blanket “late period” assumptions.

As Gordon McMullan has shown, the false attribution of agedness has dogged interpretations of Shakespeare’s later plays, as though The Tempest were the work of an elderly playwright using Prospero’s renunciation of his art to bid farewell to his own profession, as opposed to being written by a man in his forties who collaborated with other writers in three new plays shortly afterwards. Beethoven, likewise, is considered by most commentators to be one of the supreme examples of an artist developing a late style, yet he was only fifty-six when he died. What explains this tendency towards Altersstil interpretations of late works is surely the entrenched notion that the last works of great geniuses disclose profound truths about existence and the human condition and that these sage-like insights can only come at the end of a long creative life.

Paradoxically, however, the idea of a distinctive late phase of production has occasionally been applied to the final works of artists who died even younger than Shakespeare and Beethoven, as for example the idea of late Mozart and late Schubert, even late Keats. . . . The idea that a late style may be detectable in the work of a relatively short-lived artist demonstrates that a strong connection is presumed to exist between intense creativity and feelings of mortality, as though the imminence of death could telescope into a short period the experience an aged artist can command. Alluring as this may seem, it is not something that can be convincingly proved and certainly not for those whose death was unexpected. Furthermore, it aligns late style with an existential predicament above all else: it is the advance of death that is supposed to drive it. . . .

If the relationship of late style to biographical age is opaque, a further problem emerges in connection with its duration. How late is ‘late’? Is the immediate proximity of death essential? If not, how would we limit our exploration of late style? To the last five years of an artist’s activity? Or the last ten? Or would the last twenty years be permissible in some cases?

One might add that the notion of insight gained through growing old is assumed to be a phenomenon shared by all artists, seemingly in a similar way. Surely, however, brilliant artists age in different ways, with a huge variety of reactions to becoming elderly and eventually facing death. Surely also, they encounter all sorts of experiences and obstacles beyond their control that may cause changes of style and theme.

As the case of Turner’s life and legacy shows vividly, simple recourse to designating an artist’s “late period” as an explanation of almost anything that the person does in later life makes it easy to ignore the pertinent, provable circumstances that actually caused changes in his or her work. History is so hard to do.

What can Turner’s career and posthumous reputation tell us about the need to study the contexts of aging filmmakers’ works? For purposes of this discussion, 65 is taken to be the point at which one becomes “officially old” (as Ian McKellen entitled the blog entry he posted on his sixty-fifth birthday) .

Too old to have a late period? Manoel de Oliveira

At 100 years old, Oliveira in 2008 shooting Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl

An obvious place to start is with the Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira. He was born December 11, 1908 and died April 7, 2015, at age 106. He might have had the longest ever career in filmmaking, but he had trouble breaking into the industry and experienced a very slow start. Probably his first film to be completed is Douro, Faina Fluvia, which fortunately survives. It’s a beautiful, short city symphony about his home town, finished in 1931, when he was 23. His first feature, Aniki-Bóbó (1942), was made when he was 34, and his second, Rite of Spring, came out in 1963 when he was 55. In between he had made documentary shorts; in 2019 Il Cinema Ritrovato presented restored versions of two of these. The third, Past and Present did not appear until 1972, when he was 63.

At 63, he should have been on the cusp of a late period, but his career was just picking up steam. He had 28 features and many shorts still to come over the next 43 years. Beginning in 1985 (age 77), he released a feature film nearly every year until 2012. Two shorts followed, one of which came out in 2015 the year Oliveira died. He even made a reflective, modest film about his life, Visita ou Memórias e Confissões in 1982, to be shown after his death. So at the 2015 Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, we saw a “new” and charming Oliveira.

Here we confront Smiles’s problem of how long before death to start the late period. Going by strictly by the 65-year-old rule, that would be with Benilde or the Virgin Mother (1975), released when he was 67. That places nearly all of Oliveira’s features–28 of 31–in his putative late period. Not very useful. But what about style or tone? Can the films be grouped in some way to determine where a director in his 90s or past 100 might finally reach a late period–if at all? Presumably all or most of the films made within that period share some characteristics that mark them as late.

I would suggest a hypothetical test to see if such a distinction can be made from the films themselves, and I will also predict the outcome of that test, since it’s pretty obvious.

Say we show two films by Oliveira to some people who know nothing about him or his films: Francisca and The Strange Case of Angelica. Both are tales of obsessive love on the part of a male protagonist, which helps the comparison. Afterward, ask the subjects which is the film of an old man and which of a young man. If such a test could be arranged, I would bet that most or all of the people asked such a question would pick The Strange Case of Angelica (2010, Oliveira’s 30th feature, released when he was 101) as the film of a young man and Francisca (1981, his sixth feature, aged 72) that of an old man. In the case of Oliveira, at 72 we must count him as a youngish man, at least in the context of his film career.

David and I were lucky enough to see and report on Oliveira’s last three features at the Vancouver International Film Festival. These were Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl (2009), Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow (2012). Although we pretty much had to mention the director’s age, going back to our reports I was happy to see that we did not treat the films as the accomplishments of an old man.

Discussing Eccentricities, David described the strange device of having characters who are ostensibly talking to each other say their lines directly to the camera. He concluded, “Whippersnapper directors a third Oliveira’s age would not dare so much.”

Of Angelica the following year, I wrote, “The fact that Oliveira was 101 when he made this film, as well as the fact that he is still directing at least a film a year (for last year’s Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, see here), is too extraordinary not to be remarked on. Yet we shouldn’t let it dominate our view of Angelica or tempt us to treat it as an old man’s film. Slowly paced and meditative it may be, but it is also imaginative and full of humor, despite being centered around a young man’s obsessive love for a dead woman.”

Playing the role of a little old lady: Agnès Varda

Oliveira’s career is almost as anomalous as one can be in the realm of filmmaking. He started very late and kept going very late. Agnès Varda, on the other hand, started young and charged ahead, remaining productive until her death at the ripe old age of 90 (May 30, 1928 to March 29, 2019)–though not always making films.

Varda had established a career as a photographer by the time she directed her first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955), which was released when she was in her mid-20s. It’s a sort of blend of Neorealism, the psychological concerns which were becoming prominent in 1950s art cinema, and her own budding style. The film gained enthusiastic reviews from the Cahiers du cinéma critics but was otherwise largely ignored. Only recently has it gained attention and, ironically, gained Varda a reputation as the grandmother of the New Wave. After her first film’s failure, she made three short films before gaining attention with Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962).

Few would deny that Varda had a late period, and one that can be precisely dated. I believe that she did, but my point here is that late periods can and often do result not from a maturing mental state caused by age. Varda’s late period was caused by her tenuous position in the French film industry and the developing technology of filmmaking.

In 1954, Varda formed Ciné-Tamaris (French for a family of flower-bearing plants known as Tamarisk or Tamarix), her own production company. Most of her films were produced by it, cobbling together funding from a variety of film companies, government subsidy, and European television channels. In this way she kept control of her films from La Pointe Courte to the end. She also managed to be enormously productive, making fiction features, documentaries, and films that seemed to be both at once. She was an independent working largely on the margins of the European film industry.

Then, in 1995, there came a more commercial feature, Les Cents et une Nuits, a relatively big-budget project. It was also made by Ciné-Tamaris with a somewhat larger group of investors providing a bigger budget. It had famous stars, Michel Piccoli and Marcello Mastroianni, in the main roles plus many bit parts and walk-ons involving an amazing group of cinema luminaries. Despite all this, the film failed and thereby caused a crisis in Varda’s life.

My colleague and friend Kelley Conway, an expert on Varda, has summed up the nature and causes of her late period:

Yes, there is a commonly held belief in the scholarly community that Varda really did experience a “late period” that began precisely in 2000.

Three things stand out: her embrace of digital video, her turn to autobiography, and her venture into fine arts. (She become a plasticienne [visual artist], as she often said.)

After the critical and commercial failure of Les Cent et une nuits (1995), she withdrew from filmmaking. She renovated a building on some property she owned in the south of France, created an inn, and appeared to be headed for a pleasant retirement. But then, in 2000 she made GLEANERS AND I, which put her back on the map. She often stated–and I have no reason to believe it’s not true–that she was inspired by digital technology to re-engage in filmmaking.

The “fine arts” that Varda’s urge to create led to were largely installation pieces and photography. She made no films for five years.

Varda expert Bernard Bastide agrees with Kelley’s description and also emphasizes that the availability of small digital cameras enabled to a considerable degree a revival of the earlier phases of her career:

She threw herself into installations because she rediscovered a simpler creativity, linked to her pleasure in “making” and without the necessity to assemble large budgets.

The return to filmmaking was in fact caused by the shift to digital cameras (DV, mini DVD). That moment was a return to her beginnings (lightweight equipment, freedom of movement, etc.) and the pleasure of regaining the playful dimension of the cinema which she had lost with the large production of Cent et une nuits.

The main difference between the digitally-made films that resulted from Varda’s return to filmmaking and her pre-1995 work is, as Kelley points out, a greater autobiographical content. Varda appears in these films, as subject and narrator. (She had appeared in some of her earlier films, but less as the central figure of attention.) This was probably in part a practical decision, since she could work with a minimal crew and replace the actors whom she would otherwise need to pay. As Kelley also points out, however, the late features are not entries in an ordinary autobiography. Here she is writing on the overtly autobiographical The Beaches of Agnès (2008), made when the director was 80:

The very first shot of the film features Varda walking backwards slowly on a beach. She announces, “I’m playing the role of a little old woman, pleasantly plump and talkative, telling her life story.” If Varda is playing the role of a little old woman telling her life story, then the question immediately arises, is this just one of the many roles she could play? [….]

A close look at the style and rhetoric of the film reveals that Varda is not particularly interested in the traditional concerns of the autobiographical documentary, such as the exploration of personal crisis, the critique of the family or socio-political analysis. Les Plages d’Agnès strives, above all, to assert Varda’s status as an active, working, ever-evolving artist, and to memorialize her œuvre in photography, film and installations.

The idea of memorializing her non-film work in particular becomes more prominent in her final feature, Varda par Agnès, where the installations and photography play a large role.

At any rate, Varda does seem to have had a late period, if one that came about through circumstances beyond her control. And yes, there was probably an autobiographical strain in some of the films brought on in part by a growing sense of the end approaching.

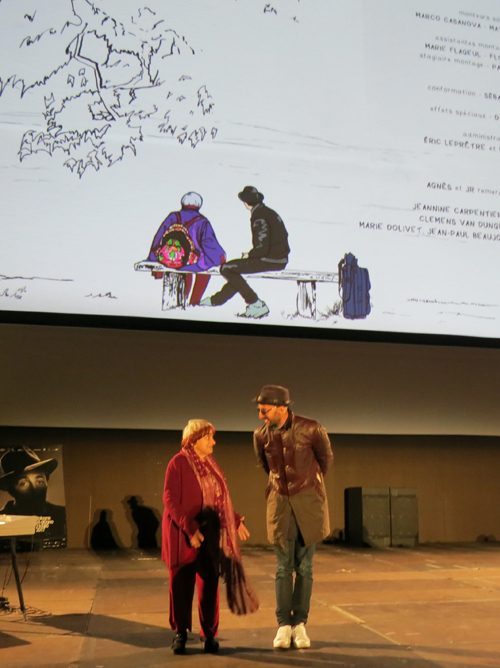

Yet to resort to a cliché, she was one of those people who seemed perpetually young. I met her only briefly twice, but I vividly remember Varda’s appearance at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna in July, 2017. She and her collaborator, street artist and photographer JR, had brought Visages, Villages, which had its Italian premiere as the 10 pm film in the piazza on the last night of the festival. It was hardly a re-found or restored film, the presentation of which is the raison d’être of the festival. But the fact that a brand-new film that hadn’t yet had the slightest chance to be lost or in need of restoration was screening in a place of honor didn’t bother anyone. The standing ovation that greeted the pair afterward (above) went on for many minutes, despite it being past midnight, because the crowd didn’t want to stop sharing the delight that she so obviously felt deeply.

We turned out to be staying in the same hotel as Varda and JR, and we saw them bright and early at breakfast the next morning. We went over to say hello, having met Varda briefly when she visited Madison for a retrospective of her films and a conference devoted to her and her work. We reminded her of this, and though she could hardly have remembered us, she grabbed my hand and held it as JR, David, Varda’s daughter Rosalie, and others carried on a conversation about the thrilling reception of their film. She could hardly have slept more than a few hours, if at all but her energy and eagerness to talk completely belied her age. I’m not sure why she held my hand, but I suspect it was because I happened to be the nearest to her and she was so happy that she wanted to embrace everyone there.

A few brief examples

There are many other directors one could cite, but the point should be clear enough with a few others.

It seems as if Ozu Yasujiro is one of those directors that people love to think of as having had a late period. As I mentioned above, a sure draw as a retrospective would involve Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Tokyo Story (1953), Equinox Flower ( which gets better every time I see it, 1958), Late Autumn (1960), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962, above). Nearly all of them revolve around the breakup of a family through the marriage of a daughter and involve elderly parents as central or at least major characters (the grandparents in Early Summer). The titles’ trip through the seasons of a year (though An Autumn Afternoon‘s title translates as The Taste of Mackerel) seems to echo Ozu’s own aging over the years, and the assumption probably is that Ozu identifies with the elderly fathers (or mother in Late Autumn) who bow to the inevitable marriage of a daughter. I suspect that many people assume Ozu was quite elderly when he died.

But isn’t all this something of an illusion? With his usual flare for precision, Ozu (December 12, 1903 to December 12, 1963) died at age sixty on his sixtieth birthday. So in fact he fell short of becoming officially old. What we think of as the wisdom achieved in old age seem to have been with him much earlier, perhaps from the start. The comic tone of his early “salaryman” films suggests the cynicism that often comes with long experience.

Consider, too, Tokyo Story, his saddest film. Even earlier than most of his films about young people flying the parental nest, he made a film dealing with what can happen to those parents after the offspring leave. The elderly couple face neglect from their own children and gain consolation only from a daughter-in-law, not their own children (though the grimness is mitigated to some extent by having the youngest daughter still at home.) It’s the only one of these later films where one of the parents dies. Ozu was fifty when it was released.

Despite this seeming consistency of subject matter in these, the best-known of his films, Ozu was making others, quite different, alongside these. Most notably in this context, Ohayu (1959), a very funny film about two boys who engage in farting contests with their friends and go on a silence strike to pressure their parents into getting them a television, came out only three years before An Autumn Afternoon. Equinox Flower is considerably more comic in his treatment of parents and marriageable children than the other films in this group, and the parents are not as elderly as in the other films.

Going back to my idea of showing two films to a group completely unaware of the director’s work, let’s imagine people seeing Tokyo Story and Ohayu and being asked the same question.

Sergei Eisenstein is an interesting case. He died fairly young, just after his fiftieth birthday, in 1948. Clearly he had two different periods, First there were the silent Montage films of the 1920s, from Strike in 1925 to Old and New in 1929. We can’t really judge the years after that, with ¡Que viva México! (1932) being taken away from him before it was completed and Bezhin Meadow (1937), banned and apparently destroyed, though clippings survived and were used to create a reconstruction made up of still frames.

A new period started with Alexander Nevsky (1938) and continued with Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1943) and Part II (banned and not released until 1958). With the Montage films denounced as “formalist” in the early 1930s, Eisenstein changed perforce, to the officially approved genre of epic historical biographies, primarily of pre-Revoluntionary figures interpreted as heroes working toward the spirit of Communism. Ivan was a particular favorite of Stalin, who identified with him. During the late 1930s, Eisenstein managed to avoid the gulag and the firing squad, though many of his colleagues, including the major stage director Vsevolod Meyerhold, did not.

The conditions under which Eisenstein could work and escape such fates demanded that he change his style, and he adopted a new one, though subtly incorporating some principles of the Montage movement and working out new techniques of his own. I suppose these films could be considered as constituting the late period of a middle-aged man, but in this case the impetus came from a very strict and dangerous outside force.

The idea of filmmakers reaching a late period through life experience that gives them greater insight may happen in some cases and is not necessarily a worthless one. Robert Bresson’s early films from Diary of a Country Priest (1951) on centered in some fashion around the quality of religious grace, but gradually his films slipped into a more bitter tone, as exemplified by the grim ending of his version of the Arthurian Legend, Lancelot du Lac (1974), which ends on a heap of dead armor-clad knights. Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud seems to stand apart from his earlier films as the work of an old man.

Yet other filmmakers as great as these seem to have, as it were, their late periods early on. That is, they produced their best work for a time well before old age and then declined to some extent. I know there are people who enjoy and admire Jean Renoir’s later films, say, after The River (1950)–which were made over a span of twenty years. Yet few among them, I suspect, would say that those films rise to the level of his incredible burst of brilliant films during the 1930s.

Renoir’s decline goes against the foundations of the late-period premises that Smiles critiqued in the passage above. The concept depends largely on the idea that the late period comes when artists have gained the insight of age and applied it to their work to impressive effect. The knowledge of upcoming death is partly what spurs, presumably, greater contemplation of the world and the elderly artists’ places in it.

The concept of an artist’s late period can be usefully applied in some cases, but not every artist’s life included experiences or obstacles or opportunities that shaped that period. The misunderstanding and even unjustified appropriation of Turner’s late work for so long after his death provides a warning that when we are attempting to apply the concept to an artist’s creative life, we should not assume that just doing so in itself conveys something meaningful. All this is not to say that Turner did not have a later period. He clearly did. But a study of any artist’s historical context must be undertaken in order to explain how and why that particular artist’s work would change with age–or not.

The Sam Smiles quotation is taken from his excellent The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner: The Artist and His Critics (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art: 2020), p. 8. The quotation from the smug MOMA curator comes from another excellent Smiles book, J. M. W. Turner: The Making of a Modern Artist (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), which thoroughly takes apart the notion that Turner managed to foresee or even invent virtually every western art movement of the twentieth Century.

Constable’s comment that Turner had a wonderful range of mind is not apocryphal. He wrote it in a letter to his sister. It has often been quoted, including in the title of John Gage’s J. M. W. Turner: “A Wonderful Range of Mind” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987). I would recommend this book as a good place to start learning about Turner. Gage’s Color in Turner: Poetry and Truth (New York: Praeger, 1969) is a rather dry read (it had been his dissertation), but it marked a turning point in the interpretation of Turner’s late work. Coming only a few years after the MOMA exhibition, it revealed Turner as not an eccentric visionary but as an intellectual interested in science and the theory of painting. Turner’s interest in Goethe’s theory was first made known here. Gage’s later book, just cited, expanded his coverage of Turner’s influences as an artist and is presented in a more palatable fashion. Other scholars such as James Hamilton (Turner and the Scientists), Sam Smiles (the two works cited above), and many more followed with similar investigations.

Online jigsaw puzzles can be played and created very easily on jigsawplanet: My own puzzles created from Turner paintings are here. I always make them at the maximum number of pieces, 300, but the flexible site allows you to pick how many pieces you prefer. When you finish the puzzle, the lines between pieces dissolve away, and you are rewarded by a clear image of the painting or object.

My thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing her thoughts on Varda’s “late period” in a recent email discussion. I have quoted the first passages above from that correspondence (March 30-31, 2023). The second quotation, beginning “A close look …” is from her essay,” Varda at work: Les Plages d’Agnès” Studies in French Cinema 10, 2 (2010):126-27. Her book, Agnès Varda (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), is based on a friendship with the filmmaker, as well as extensive work in published sources and the filmmaker’s own archives.

My thanks also to Bernard Bastide, journalist, film scholar, and teacher, with whom Kelley put me touch. He also offered a summary of the causes for that five-year hiatus in Varda’s filmmaking and kindly allowed me to quote him, using my own translation (email communication, March 31, 2023).

Manual labors

The Tin Star (1957).

DB here:

Type “screenplay writing” into Amazon and you’ll get over 6000 hits. Some of those books will be biographies of writers or screenplays of released films. But there’s still a huge number of DIY books with titles like How to Write a Movie in 21 Days and Writing Screenplays That Sell. A lot of people are apparently only one manual away from a finished script.

Screenplay manuals trigger suspicion. Can it really be that easy? Wouldn’t this be a paradise for grifters? A successful writer would hardly share trade secrets, so most of these books would be written by losers and wannabes. And if you read enough of the manuals, you’ll see the inevitable repetition of banalities. Make your protagonist “relatable.” Keep the conflicts going. Try for a twist.

Reading through them can be mind-numbing, but if you’re interested in how filmmakers tell stories, sometimes they can open up your thinking. Or so I’ll argue.

DIY scripting

The tide of manuals rose during the 1910s, when the emerging American studio system was seeking talent. The tide subsided between the 1930s and the 1960s, when screenwriting was contract labor in that system. But as filmmaking turned “independent,” ambitious people outside the industry could break in with an original script. Manuals, most famously Syd Field’s Screenplay (1979), began to pop up, and the market for how-to books expanded. Field’s book remains in vigorous circulation today, among many competitors.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

If your research touches on matters of style, you may find it illuminating to study the way practitioners pick solutions to practical problems. Which is to say that the manuals can point us toward norms. Norms are, I’ve argued, like a menu of more and less preferred options for treating the material. We developed this angle of inquiry in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, and now it seems well-established that the manuals can sometimes point us toward tacit norms of construction or visual style. For examples of how this can work, see Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, my The Way Hollywood Tells It, and Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Many of our blog entries have also explored these paths. With screenplay manuals, we just have to be particularly careful to distinguish valuable data from bilge–which means checking the manual’s precept against many films.

And we shouldn’t expect the manuals or professional journals to identify every normalized device. For example, screenwriters now love to start scenes with friends greeting one another with “Hey” and “Hey,” but I doubt that there’s an explicit decision to avoid “Hi.” Similarly, I’ve never found anyone writing in the classic era who mentions the common Hollywood device of the double plot, with one line of action devoted to a goal-oriented activity and another, interdependent one devoted to heterosexual romance. Even the rather elaborate 180-degree classical editing system wasn’t apparently spelled out anywhere; it was learned by imitation and reinforced because it was economical and efficient. People can learn and follow rules that are simply taken for granted as “the way we do things.”

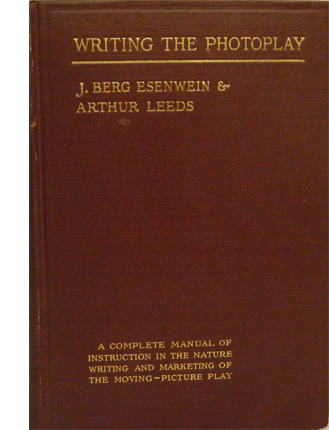

I think my soft spot for the manuals owes a good deal to my long-term affection for one item I saw in a 1913 guide. J. Berg Esinwein and Arthur Leeds’ Writing the Photoplay contains a lot of hints about standard practices of the period, but one of their diagrams changed my basic attitude about silent film technique.

The cinematic stage

In the late 1990s I became interested in the norms of scene staging in early film. I assumed that filmmakers had to call attention to story action without benefit of cutting to closer views, so I tried itemizing in a straightforward way the staging choices that could guide the viewer’s eye.

Many of the choices could be called “theatrical.” Lighting and setting could emphasize an actor’s gesture or facial expression. Performance factors operated as well, especially since actors were typically facing the viewer. Filmmakers’ reliance on these cues seemed to confirm the standard impression that early film was less “cinematic” than what came later.

Yet there were purely pictorial factors in play as well–notably, the placement of figures in the overall image. Composition of the frame, as in painting (and theatre) played a crucial role in guiding our attention.

There was something else. I was fascinated, for reasons sketched here, with the depth that many scenes in “tableau cinema” displayed. Here’s a quick example from Alfred Machin’s Le Diamant noir (1913). The entire film is available from the Belgian Cinematek.

The young secretary Luc is accused of stealing the missing diamond. He protests his innocence, but the accusation will force him to leave the country.

All the cues I’ve mentioned are at work here: centered figure placement, frontally facing characters, attention-grabbing gesture, favorable setting (the rear doorway and curtains highlight Luc’s arrival), and so on. In addition, a tunnel of information bores through the frame, leading from the distance and culminating in action in the foreground.

But this tunnel couldn’t fairly be considered “theatrical,” since if the action were played on a stage, not all viewers would have the optimal view presented in the shot. Most of the audience simply couldn’t see this alignment of players. Theatrical staging tends to be lateral and fairly shallow, so that people sitting in different seats can all see the scene. A good part of planning a stage production is calculating sightlines. But in film, there’s only one sightline, that of the camera lens.

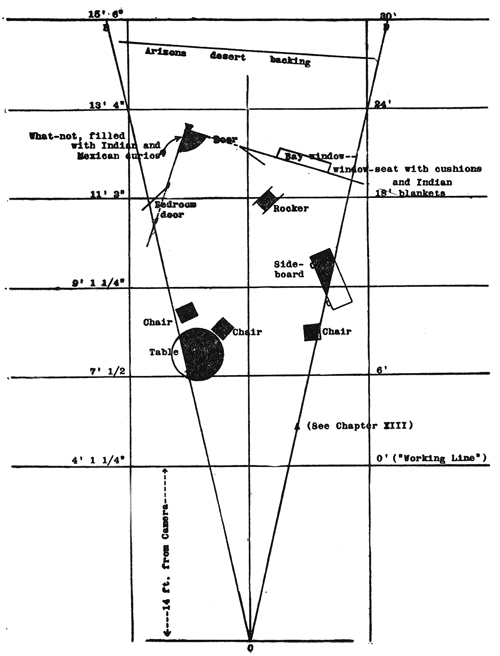

We tend to see film space as cubical, a room with a missing fourth wall. Actually, the playing space–what Esenwein and Leeds call “the photoplay stage”–is a tapering pyramid whose point touches the lens. Because the film image captures an optical projection, the space is narrow but deep. The authors provide a diagram of a scene to explain. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve removed some of their annotations; the full version is on p. 160 of their book.) The effect is of wedge shape that carves into what would be the wide space of a theatre scene.

In 1910s cinema, the camera lens (at point 0) is assumed to be some distance from the “working line,” the layer of maximal attention. For some filmmakers this line was nine or eleven feet from the camera, rather than the 14 feet assumed here. The rest of the space falls away in the distance, and depending on the lens and lighting used, these areas can be in more or less sharp focus. Filmmakers of the period often marked out the pyramid on the studio floor so that actors would know when they were out of shot.

This diagram makes explicit many of our taken-for-granted notions about film space. Someone moving closer to the camera gets larger, of course; but the figure also blocks out more and more of the background as the pyramid narrows. An actor’s forward movement on the stage inevitably takes up a small part of the overall area, but in cinema forward-thrusting action can dominate the frame.

Just as important, the fixity of the lens makes it possible to choreograph actors with a precision impossible in theatre. Luc’s confrontation with his employer in my second frame gives him pride of place, but once he’s slumped at the foreground desk, he can move his head and clear the central zone for us to see a servant waiting in the distance. In tableau cinema, staging isn’t just “blocking.” It’s blocking and revealing, a constant flow of information presented through shifting arrays of figures. I provide several examples in the lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

My heightened awareness of the visual pyramid made me more sensitive to staging in all periods of cinema. We might think that after the tableau cinema period, when filmmakers became more dependent on editing, their reliance on the “photoplay stage” vanished. But of course every shot, close or distant, presents us with the visual pyramid, and some filmmakers relied upon it to provide the graduated layers of space in an edited sequence. Specifically, the “deep focus” that became a favored technique of 1940s cinema around the world would seem a modernization of the principles of the 1910s recognition of wedge-shaped playing space. Here’s an outrageous example from Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), shot by Gregg Toland after Citizen Kane.

Less punchy imagery than this suggest that the skills of 1910s staging were never really lost. Another passage from Ball of Fire brings Professor Potts to the foreground in a way reminiscent of Machin’s film. Of course it helps when Gary Cooper is the tallest galoot in the scene.

Cinema’s visual pyramid becomes almost sadistic at the climax of Anthony Mann’s Tin Star (1957). The young sheriff stops a lynching by shaming the town bully. The bully responds as you’d expect, but not in the sort of shot you’d expect.

Mann’s earlier films had experimented with foregrounds thrusting out at the viewer, but this sequence carries the idea to a limit. The actor collapses against the camera, inadvertently proving how lines of cinematic sight converge at the lens–that is, at our viewpoint. Try doing this on the stage!

This entry is more a piece of intellectual autobiography than anything else. I doubt many other people were opened up to the intricacies of staging thanks to a diagram in an old book. I mean it just as an example of how reading manuals can set you thinking about the expressive possibilities of film, and taking you in directions that you couldn’t predict.

More recently, in writing Perplexing Plots, I poked into manuals for would-be fiction writers, an area that literary historians seem to have neglected. These manuals yielded a lot of principles of what people thought went into good storytelling. In particular, I found that while Henry James and Joseph Conrad were making arguments about viewpoint and chronology, so too were people writing how-to manuals. The books indicated a new awareness of these techniques among writers aiming at mass audiences.

Terry Bailey surveys and analyzes early manuals in “Normatizing the silent drama: Photoplay manuals of the 1910s and early 1920s,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (Jun 2014), p. 209 – 224. For a comprehensive overview, see Steven Price, A History of the Screenplay.

The main argument here is developed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

Ball of Fire (1941).

The reader is warned

Where the Crawdads Sing (2022; production still).

DB here:

When I wasn’t paying attention, along came Where the Crawdads Sing (2018 novel, 2022 film). The book was a huge bestseller, while the movie version was panned by critics but attracted a good-sized audience. It exemplifies how strategies of nonlinear storytelling have become deeply woven into mainstream entertainment.

It has an investigation plot, structured around the trial of “swamp girl” Kya, who’s accused of the murder of her boyfriend Chase in the marshlands of North Carolina. Through flashbacks we learn of her desperate childhood, as she is abandoned by her family and castigated by the townfolk. She learns to live alone in the family cabin and fills her days drawing precise images of the natural life around her. A well-meaning young man teaches her to read but he too he leaves her to struggle alone. Soon she meets Chase, a charming good-for-nothing. Is his fall from a swamp tower an accident, or did someone push him? A kindly local attorney takes her case, and the plot climaxes first in the jury’s verdict and then a twist that reveals what happened at the scene of the crime.

We’re so used to plots like this that we may forget how nonlinear they are. In the Crawdads film, the court investigation probes the circumstances of Chase’s death, but the flashbacks, instead of illustrating stages of the crime, supply Kya’s life story in chronological order. They contextualize the long-range causes of her dilemma. Accordingly, they’re narrated by her in voice-over. Titles supply the relevant timeline, dating episodes from 1963 through to 1970, the year of the trial.

All of these strategies have become familiar from a century of popular storytelling. A court case as an occasion to visit the past goes back at least to Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), although the play dramatizes testimony in a way that Crawdads doesn’t. (Its flashbacks, more boldly, are in reverse order.) The crosscutting of past and present has become common to explain (or obfuscate) ongoing story events. Tying us to a character’s viewpoint and letting the character’s voice narrate what we see is likewise a standard device in modern media. And of course an investigation plot is inherently nonlinear. The task is for someone to uncover the “hidden story” of what occurred in the past.

Simple though it is, Where the Crawdads Sing shows just how pervasive devices associated with mystery and detective fiction have become in mainstream storytelling. Told chronologically, the story would be a biography of Kya (and would presumably have to reveal how Chase died). Instead, the film becomes what Wikipedia calls “a coming-of-age murder mystery.”

By splitting the chronological story into two parts and interweaving them, manipulating viewpoint, and rearranging temporal order, the film tries to achieve interest and suspense. We know from the start that Chase is dead, so we watch every scene with him for clues as to what could have caused it. Tension gets amplified as time passes, when the shifts between the courtroom drama and the day of Chase’s death come faster and faster. These effects couldn’t be achieved with a linear layout.

One of the major points of Perplexing Plots is to remind us just how much of popular entertainment trades on narrative strategies forged in the big genre of mystery. Once we’re reminded, we can ask: How did those strategies get implemented? How did audiences come to understand and enjoy these highly artificial ways of telling stories?

I promise not to keep plugging the book on this blog, but allow me one more notice. A Q and A with me has been published on the Columbia University Press site. It tries to inform any souls whom fate has cast my way about the argument of the book. You may find it of interest.

I’m taking the occasion to note some features of the book not advertised elsewhere. Perhaps they too would appeal to you, especially if you’re interested in some of the choices a writer has to make.

Obscure is as obscure does

First, the book draws on some unorthodox sources. Most obviously, I tried to canvass obscure novels and plays that are now forgotten but that did try some experiments with nonlinear storytelling. Who’d expect a reverse-chronology play in 1921, years before Pinter’s Betrayal (1978)? A 1919 play anticipates Rear Window by offering testimony from a deaf witness and then a blind one. The first version plays out on stage in pantomime, the second in a completely dark setting. A 1936 novel offers a string of conflicting character viewpoints on a single situation, revising and correcting previous accounts, well in advance of Herman Diaz’s recent novel Trust. A 1919 play depicts a woman in different aspects, as seen by the people who know her. These instances of what we now call “complex narrative” belong to what literary scholars have called “the great unread,” the thousands of pieces of fiction and drama that haven’t become canonical through enduring popularity or academic favor.

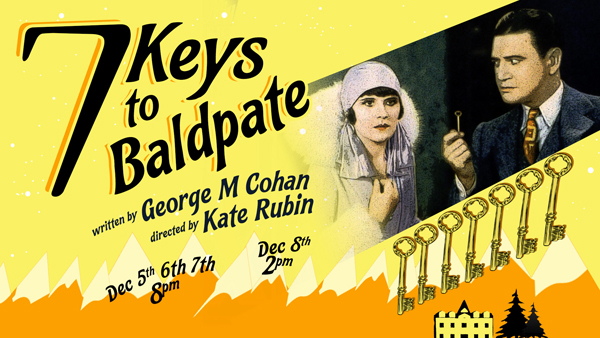

Other precedents are dimly recalled but seldom revisited, such as George M. Cohan’s play Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913) and W. R. Burnett’s Goodbye to the Past (1934). How many people would be aware of Kaufman and Hart’s reverse-chronology play Merrily We Roll Along (1934) if Stephen Sondheim hadn’t turned it into a musical? The very existence of these marginal works helps support the premise that a lot of what we consider innovative today has broad historical roots. They just aren’t as vivid to our memory as more recent instances. But fifty years from now, will many viewers remember contemporary experiments like Go (1999) and Shimmer Lake (2017)?

The book uses other unorthodox sources. I put craft technique at the center, and so it makes sense to look at the principles that writers of fiction and drama were using. Of necessity I review the emerging idea of the “art novel” at the end of the nineteenth century, with Henry James as spokesman for this trend. In addition, unlike most mainstream literary histories, Perplexing Plots consults contemporary manuals for aspiring writers. These books are the progenitors of all those how-to-get-published books that fill Amazon today, and they reveal a surprising sophistication. Manuals allow me to show how a new self-consciousness about linearity, particularly point of view, became central to popular writing as a craft. For example, a now-forgotten critic, Clayton Hamilton, epitomizes the willingness of ambitious writers to try out new possibilities.

So one choice I made was to search out fiction, drama, and films that have fallen into obscurity. Another was to look at the nuts and bolts of plotting, as practitioners seemed to be conceiving it. These help explain why many novels and plays, major and minor, began tinkering with innovative storytelling.

Time as space

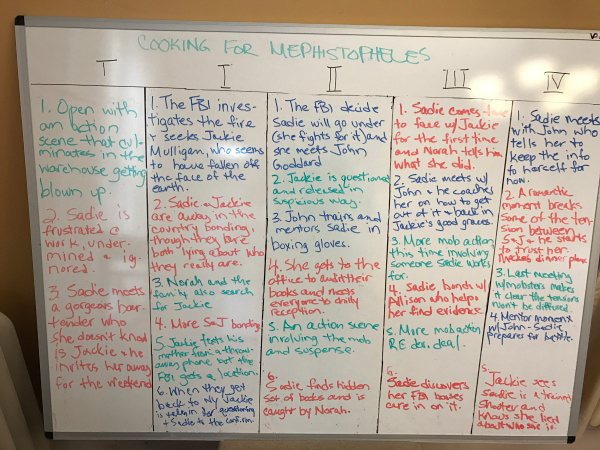

From Karen Loves TV: “Contemplations on the Whiteboard.”

A nonlinear plot has a geometrical feel to it, so one way of thinking about it is to envision it as a table or spreadsheet. Where the Crawdads Sing could be laid out in a double-column table, with each present-time scene aligned with the past sequence that follows it.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

Novelists have long made use of such charts. The most famous is that prepared by James Joyce for Ulysses, where each chapter is assigned a different color, body organ, and so on. This was published in Stuart Gilbert’s 1930 book. Because the rights to reproduction are obscure, we regrettably didn’t include it my book. No surprise, though, it’s available online.

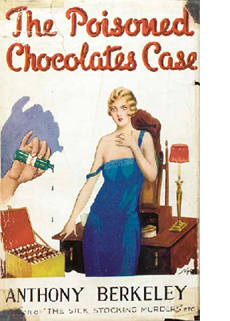

I did, however, obtain rights to a less-known but rather brilliant table included in Anthony Berkeley’s Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Later chapters of Perplexing Plots use tables of my own devising to clarify the complicated layout of Richard Stark’s Parker novels, the chapter structures of Tarantino films, and the alternating viewpoints and time schemes of Gone Girl. There will always be readers who complain that these tables are just academic filigree, but I believe that they help us appreciate the intricate interplay of time, segmentation, and viewpoint. They show how precise the narrative architecture of mystery fiction can be.

To spoil or not to spoil

For decades, criticism of mystery fiction has labored under the expectation that a critic must not reveal a story’s ending, or the story’s central deception. In journalistic reviews of literature and film, the writer is expected to keep such things secret, but even academic studies of crime fiction put pressure on the critic to maintain the surprise of whodunit and howdunit.

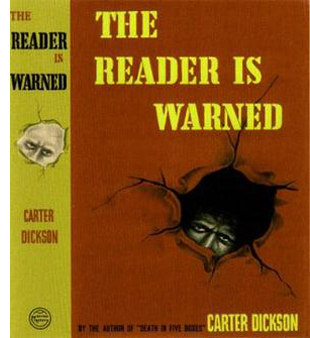

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

Part of the justification for hiding the legerdemain is the doctrine of “fair play.” I trace how this idea emerged in the Golden Age of detective fiction, when a story was treated as a game of wits between author and reader. In principle, nothing necessary to the solution of the puzzle should be withheld, though it can be disguised or hinted at. One thing I learned in writing the book is that fair play has become a premise of most duplicitous narratives in any genre, from horror to science fiction. People don’t realize how much the maneuvers of Psycho and Arrival owe to the belief that the audience should in principle be able to go back and see how we were misled. (We can do this with the “missing clue” in Crawdads as well.)

Fair play encourages the author to be ingenious and entices the audience to appreciate artifice-driven construction. Both effects are legacies of classic detective fiction, and they still shape much mainstream entertainment.

Thanks to Maritza Herrera-Diaz of Columbia University Press for arranging for the Q & A published on the Press site.

The phrase “the great unread” is used by Margaret Cohen in The Sentimental Education of the Novel (Princeton, 1999) and cited in Franco Moretti, “The Slaughterhouse of Literature,” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 61, 1 (March 2000), 208.

As I’ve indicated in an earlier entry, Martin Edwards’ The Life of Crime is a vast and entertaining survey of the history of mystery fiction. It was crucial help to me in writing Perplexing Plots. Martin, an advance reader of the manuscript, has been kind enough to discuss my book on his blog.

Other early responses to the book have been encouraging. Michael Casey reviewed it for The Boulder Weekly, and Doug Holm discussed it on KBOO on his show Film at 11. My thanks to both these commenters.

Psycho (1960): Misdirection and fair play all in one shot.