Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

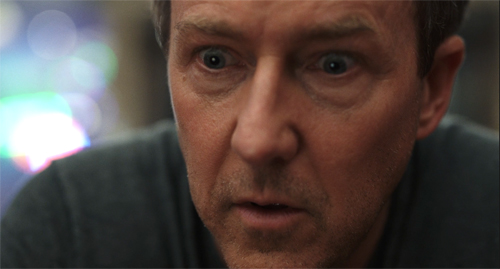

GLASS ONION: Multiplying mysteries

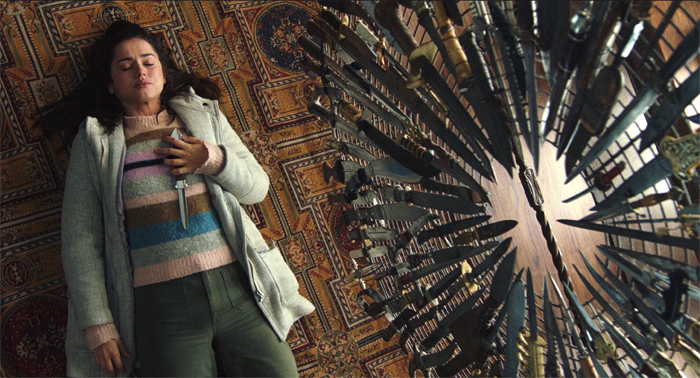

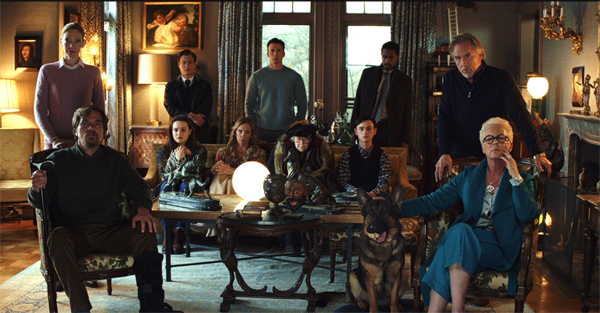

Glass Onion (2022).

DB here:

Rian Johnson’s enthusiasm for classic mysteries made it inevitable that I’d get interested in writing about Knives Out. Although I merely allude to the film in Perplexing Plots, I devoted a blog entry to it. While thinking about a follow-up on Glass Onion, I began a rewarding correspondence with Jason Mittell, adroit blogger and author of Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. Today’s entry reflects my thoughts after this exchange of ideas.

Despite the near-universal acclaim received by Glass Onion, it didn’t whet my interest as much as its predecessor. It’s a little too campy and overproduced for my taste. But Johnson’s ingenuity in manipulating conventions of the Golden Age detective stories by Christie, Sayers et al. makes it ripe for the sort of analysis I try out in the book. So here we go.

Needless to say, there are spoilers for Glass Onion and Knives Out. But I bet you’ve seen both films.

Tools of the trade

Knives Out.

Plotting a story is a craft, and it has some essential tools. There is, for instance, the ordering of events. Will you present events in linear story sequence, or will you arrange them in a nonchronological pattern? You can’t avoid choosing one or the other or some combination of the two.

There’s also the matter of viewpoint. Will you attach the audience to what a single character experiences, or will you roam among several characters?

And there’s segmentation: How will you break your plot up into chunks? In literature, we have sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. In theatre, scenes and acts. In film, scenes and sequences (and sometimes reels or chapters). Even one-shot movies have moments of pause or shifts of viewpoint that mark off phases of the action.

These are forced choices that every storyteller must face. It’s these three–linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation–that Perplexing Plots relies on in order to analyze both mainstream storytelling and mystery fiction.

In addition, the craft requires the audience to be engaged–at least interested, at most emotionally moved. You must choose whether to get your audience to empathize with certain characters or to keep the characters remote and unknowable. Do you want to arouse anger, approval, or some other emotion? You must decide how the choices of linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation can trigger these responses.

For example, your plot can usually build empathy for a character by showing incidents in which that person is treated unfairly. Those actions will be more intense if they’re rendered from the character’s viewpoint. This is what Rian Johnson does in Knives Out when he shows Marta persecuted by the vindictive Thrombey family, and then exploited by Hugh. The disparity in power (David vs Goliath) heightens our sense of indignation and makes the finale seem to be poetic justice (My house/my rules).

Some emotions depend directly on choices about chronological sequence. If your plot signals that some past events are significant but then doesn’t reveal them, you’re using linearity to create curiosity. If the plot summons up anticipations about particular future story events, you create a degree of suspense. If your plot introduces an event that momentarily seems out of keeping with the linear story, you can summon up surprise.

Each of these “cognitive emotions” (“cognitive” because they rely on knowledge and belief) is shaped by perspective and segmentation. Creating curiosity, suspense, and surprise depends on viewpoint: each character will have different states of knowledge about the course of events. In Knives Out, Hugh Drysdale is not suffering curiosity about whodunit: he knows he did it. But because we’re attached to Marta and detective Benoît Blanc, we share their state of uncertainty–and suspense about what may come.

Similarly, decisions about segmentation will often be made based on the cognitive emotions in play. You might end a book chapter or a play’s act or a film’s scene on a note of curiosity (“Then whose body is in that grave?”), suspense (the stalker draws near the prey), or surprise (“I’m your father!”).

As my examples from Knives Out suggest, the three tools I’ve picked out have special purposes in a mystery story. Perhaps one reason for the enduring popularity of mystery as a narrative device is its ingenious use of linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation to build cognitive emotions, especially curiosity. But a perennial problem of the genre is to build up other emotions. So we need sympathetic detectives and victims along with unsympathetic suspects, cops, and gangsters to engage us. Some writers also vamp up the suspense factor by putting the investigator in danger, a hallmark of hardboiled stories and domestic psychological thrillers (Rinehart, Eberhart, and their modern counterparts). Perplexing Plots traces some of these creative options through the history of mystery fiction.

Hidden stories

Evil Under the Sun (1982).

The mystery plot centered on an investigation tells two partial and overlapping stories. The investigation is presented as an effort to disclose what happened in the past, an incomplete and puzzling chain of events. Writers in the 1920s started to call this “the hidden story.”

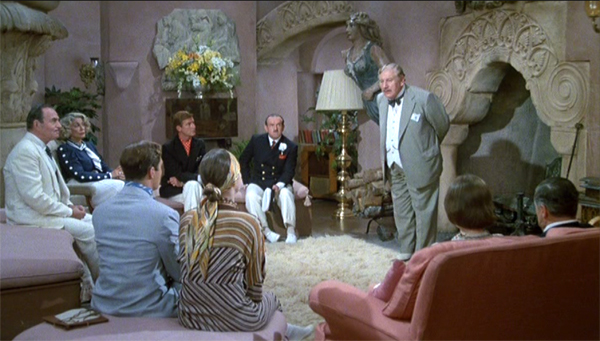

In the standard case, the detective reveals those events and makes a single continuous story out of everything. The revelation is typically saved for the climax of the present-time story line, with the detective explaining the missing events in a summing-up. Often all the suspects are gathered and the detective reviews the evidence before presenting the solution to the puzzle. In other instances, the detective may confide the results to a friend or an official.

The summing-up is often a verbal performance, with the detective recounting the hidden story. A classic example is the Christie novel Evil Under the Sun (1941), in which Hercule Poirot explains to the assembled suspects how the crime was committed. To make this scene less monotonous onscreen, filmmakers often illustrate the hidden story by brief flashbacks, as in the 1982 film adaptation of the Christie novel. Johnson employs this strategy in Knives Out, supplying quick shots of how Hugh’s scheme was enacted.

The detective’s explanation often rests on yet another hidden story line: parts of the investigation we didn’t see. Very often the detective operates backstage, pursuing clues we didn’t notice. Sherlock Holmes absents himself for a good stretch of The Hound of the Baskervilles, leaving Watson to explore the mystery of the Moors. Only later do we learn what Holmes was up to. Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe likes to keep his assistant Archie, our narrator, ignorant of information that he asks other operatives to dig up for him.

As a result, in the final summing-up, the detective’s filling in of the plot may include telling us of his offstage busywork. Again, that may be rendered on film as flashbacks to make sure the audience appreciates the sleuth’s cunning. These might include flashbacks that replay parts of the inquiry, but from a new viewpoint. In the film version of Evil Under the Sun, we see Poirot’s first visit to the cliff’s edge.

But the replay during his summing up expands this by dwelling on the vertiginous effects he feels.

In Glass Onion, Johnson finds a fresh way to treat the detective’s offstage machinations, and that depends, as you’d expect, on exploiting the three basic tools.

A package of puzzles

The most obvious innovation involves segmentation. Johnson splits his plot into two almost exactly equal halves. The first, running about seventy minutes, is a more or less complete classic puzzle.

Tech magnate Miles Bron invites his old friends for a weekend party on his private island. Their affinities go back to their days hanging out together in a pub, the Glass Onion. A fifth friend, Cassandra “Andi” Brand, co-founded Alpha with Miles, but he cheated her out of her share when she refused to expand into questionable paths. Andi shows up at the island to join what Miles calls the Disruptors. There’s Claire, an ambitious politician; Lionel, a scientist working for Miles on a new energy source; Birdie, a scatty fashionista; and Duke, an aggrieved online spokesman for patriarchy. Famous detective Benoît Blanc joins the party, even though it’s unclear who invited him.

These characters are introduced in a rapid opening sequence that shuttles us from one to the other as each gets a puzzle box. Crosscutting and split-screen imagery yield an omniscient narration; we seem to know everything. Johnson points out the expositional advantages: “The box gave it an element of fun, a spine, and a way for all the characters to be on speaker phone solving the mystery of how to open it together, so you see the dynamics between them in real time.”

Then we see a so-far unnamed woman receive a box and break it open. Finally we find Blanc himself, stewing in boredom in his bathtub. In all, a shifting spotlight has introduced us to all but one of the major characters.

Once the group assembles on the pier to board the ship that will take them to Miles’s island, the narration narrows its range and concentrates mostly on Blanc’s reactions.

In what follows, Blanc observes the others, occasionally trailing them, and asks questions about their pasts. By and large, this half of the film will be attached to him, though sometimes the narration will stray briefly to others (chiefly to give each a motive for killing Miles). The first half assigns Blanc the conventional role of curious investigator.

Miles has planned a murder game in which he’s the victim, but that puzzle collapses the first evening when Blanc solves it instantly. A new crime emerges: Duke abruptly dies of poisoning. And soon someone shoots Andi. Blanc gathers the suspects and announces he nearly has a solution. “It’s time I finished this. . . . Only one person can tell us who killed Cassandra Brand.”

In the spirit of Golden Age whodunits, Johnson has poured out a cascade of mysteries, big and small. Who sent Blanc the extra box? Why did Andi, still smarting from her courtroom loss to Miles, show up at his party? When Duke died, he drank from Miles’s glass, so who was trying to kill Miles? Duke’s pistol mysteriously disappears; who took it? The same person who killed Andi?

Johnson’s narration can be both reliable and unreliable. During the drinking session a quick long shot reveals that Miles forced Duke to take the poisoned glass. This is a daring gesture toward Fair Play (that some of us noticed), but Johnson will try to cancel our impression. He will soon offer a lying replay to blot this out.

To further swerve suspicion from Miles, Johnson uses viewpoint. We see Miles reacting in shock to a POV image of the fallen glass with his name on it, as if he were just realizing he, not Duke, was the target.

Of course he’s faking, but by privileging his viewpoint in order to underscore his reaction Johnson suggests he’s innocent. Cheating? Not really, just misleading. Johnson gives with one hand, takes away with the other–as his mentor Agatha Christie does in prose (as I try to show in the book).

Fugue states

So Blanc has a lot to explain. But instead of continuing the traditional summing-up denouement, Johnson pauses and in effect replays the first half of the film by concentrating on the detective’s offstage activities.

Turns out, Blanc has been much busier and less naive than he seemed in the first part. A conventional assembly-of-the-suspects climax would have included explanations of his scheming, but Johnson daringly fleshes these out to forty minutes that annotate scenes that we’ve already witnessed. In this play with linearity, gaps are filled, and new information is provided.

The second part starts with a young woman delivering the wrecked puzzle box to Blanc. She is not Andi but her twin sister Helen. (Yes, Johnson unblushingly taps the convention of false identity, with twins no less.) Andi is dead, killed by carbon-dioxide fumes in her garage. Helen suspects not suicide but murder and gives Blanc an account of Andi’s career through flashbacks. These bursts of nonlinearity skip freely from the gang’s youthful days to Miles’s cheating of Andi.

Moved, Blanc coaxes Helen to impersonate Andi and go to the party, as if accepting Miles’s invitation. (Blanc will convince the authorities to suppress news of Andi’s death for a time.) The two of them form a team to investigate Miles’s posse and find Andi’s killer. So now two puzzles–who sent Blanc the box? why did Andi, or rather “Andi,” show up at the island?–are set to rest. Just as important, as Knives Out focused our empathy on Marta, this second half gives us Helen as a sympathetic figure, so the puzzle element is enhanced by emotion.

Blanc’s saunters around the compound are now replayed as more purposeful, while “Andi” stands revealed not simply as an intruder but a snoop. Some scenes are only sampled, while others are fleshed out through viewpoint shifts. In addition, the narration offers hypothetical flashbacks when Helen and Blanc play with the possibilities of who might have killed Andi.

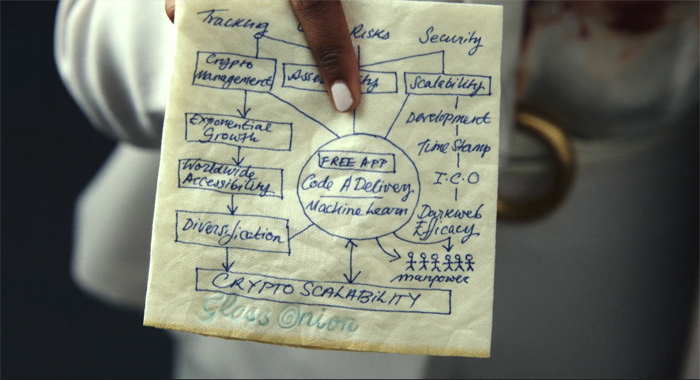

Driving the second part is the search for a crucial piece of evidence that would have won Andi the court case: the Glass Onion napkin on which she jotted down a plan for the company. After the trial she found it and told Miles’s circle; her murder was triggered by the killer’s plan to recover the napkin. When Helen finds it, she can confront Miles. In a final twist, it’s revealed that the bullet that apparently killed Helen was blocked by Andi’s diary. At her return to the group, Blanc can launch a proper summing-up and denunciation of the guilty.

The annotated replays run about 37 minutes. These incidents could have been much more concisely presented as part of Blanc’s explanation, but as Jason Mittell pointed out to me, this new plot structure gives the second part a dynamic we associate with another genre: a film tracing a big con, like The Sting. There’s a pleasure in seeing how scenes we interpreted one way now stand out as manipulated by Blanc and Helen.

Blanc’s explanations, and Miles’s efforts to block it, take another sixteen minutes. Eventually the Disruptors unite to support Andi, and Miles is facing murder charges. The film ends not with a shot of the complacent Blanc but of the righteous Helen/Andi, the co-protagonist of the second part, a figure of vengeance and vindication.

Replays that amplify and contextualize scenes we’ve already seen are common in mysteries and other genres. Johnson’s originality comes in building one long segment out of such replays. To make it work he relies on our memory of the chronological order of previous scenes to create a double-entry plot structure in which the detective’s backstage scheming revises and corrects our perception of the core action. You could lay out the action on a table of the sort I occasionally resort to in Perplexing Plots.

Johnson’s pride in folding the second half of the film back over the first part is teased when a guest at Birdie’s party explains the fugue that Miles has embedded in the puzzle box. “A fugue is a beautiful musical puzzle based on just one tune. If you layer this tune on top of itself, it starts to change and turns into a beautiful new structure.”

Johnson’s virtuoso play with segmentation has a place in the mystery story tradition; Perplexing Plots reviews several Golden Age examples. (One somewhat similar novel is Richard Hull’s Excellent Intentions of 1938.) You can imagine a version of Glass Onion that attaches its viewpoint to Blanc and Andi from the start, with the “infiltration” strategy of something like Notorious (1946) or Mission: Impossible II (2000). But that wouldn’t engage us through its gamelike, self-consciously artificiality. No film I can recall has so thoroughly routed the offstage activities of the detective onto a track parallel to that of the unfolding crime. Creating a double-column plot like this shows not only the cleverness of design demanded by mystery stories but something I stress throughout the book: the eager drive of popular storytelling toward innovation and novelty–within familiar boundaries.

Thanks to Jason Mittell for a stimulating correspondence and to Erik Gunneson and Peter Sengstock for further suggestions.

Johnson discusses how he shaped the guest assembly on the pier around Blanc’s viewpoint in “Notes on a Scene” in Vanity Fair. A lengthy piece in Vulture explains some of the citations and in-jokes in the film.

P.S. 13 January: Thanks to Antti Alanen and Fiona Pleasance for correction of two names!

Glass Onion.

The ten best films of … 1932

Shanghai Express.

Kristin here–

The year draws to a close, and the internet abounds with lists by professional critics, educated fans, and clueless people proffering opinions on the ten best films of 2022. David and I avoid this custom, but fifteen years ago I stumbled into a habit of listing the ten best films of ninety years ago. Such films have by now stood the test of time, and they have one enormous advantage: no one is speculating about many Oscar nominations each will get.

Back in the day, only two of the films on my list got nominated at all, and those two collected a total of three Oscars. (For a hint at one winner, see the image at the top. He will feature prominently in this year’s list.)

These ten films are of course my own choices, and for those who disagree, they are quite welcome to make their own lists.

As usual, my list is a mix of very familiar titles and some not so familiar ones. My hope is to call attention to unfamiliar films that are well worth a look. Actually this year nine of the films should be familiar to any serious film student or fan, but the tenth is a masterpiece that deserves to be rescued from obscurity.

Most historians seem to agree that 1932 was the year when Hollywood emerged from the difficult transition to sound and made polished movies that regained the fluidity of cinematography, staging, and editing that had been lost to some extent. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Janet Staiger, David, and I proposed that the transitional period lasted from 1928 to 1931.

The same was not internationally true, however. My list contains one silent film, since the Japanese industry went through a considerably longer transition. No wonder that half of this year’s list atypically consists of Hollywood movies.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, and 1931.

As usual, I’ll try to point readers toward the best available Blu-rays or DVDs. Those who prefer streaming should be able to find these titles for themselves. David and I prefer discs, at least for important films. With the decline of access t0 35mm and 16mm prints, studying films closely has become more dependent on discs (which also still have better quality images than streaming). Eventually, with streaming the only option obtaining frame grabs of the sort that illustrate these entries, close film analysis will become extremely difficult.

Hooray for Hollywood!

Trouble in Paradise

Ernst Lubitsch is one of the best-loved of film directors, both within the film industry and among cinephiles. I was lucky enough to be invited to teach a one-month summer course at the University of Stockholm on any topic related to silent cinema. I jumped at the chance to follow up on a vaguely planned project on Lubitsch, specifically a comparison of his German and American silent films. The course became a book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, now out of print but available through open access.

Trouble in Paradise is widely considered his best film, though I would say that at least Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Shop around the Corner are equal to it and others are not far behind.

The witty script is a model of sophisticated humor, and the casting is perfect. Herbert Marshall for a change got to play the suave hero, a dazzlingly expert crook who teams up romantically with Miriam Hopkins, his match as a wily pickpocket. In this 82-minute film, their hilarious courtship in a Venice hotel runs for a remarkable 17 minutes as they top each other in stealing things from each other, with her returning his watch and his flaunting her garter:

It doesn’t seem a minute too long. Essence of Lubitsch.

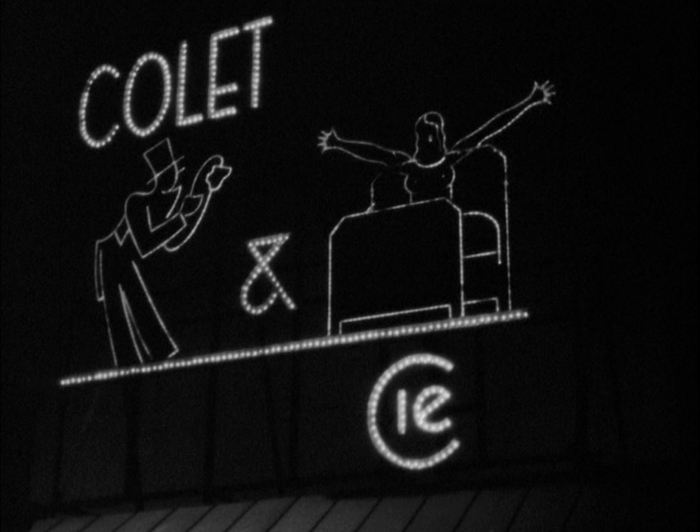

Kay Francis provides the potential trouble that threatens their idyllic life of thievery; she’s a beyond-wealthy owner of perfumery Colet & Cie. (see bottom)–so wealthy that she doesn’t really mind that her “secretary” may be a famous criminal worming his way into her confidence. Charles Ruggles and especially Edward Everett Horton provide hilarity as hopeless suitors wooing Madame Colet.

The comedy is played out in shining art-deco sets (above), lit with perfect three-point Hollywood lighting. As I demonstrate in my book, Lubitsch moved effortlessly from being the master of German silent film style to being the master of Hollywood style. It shows in every aspect of Trouble in Paradise.

The Criterion Collection DVD is still available.

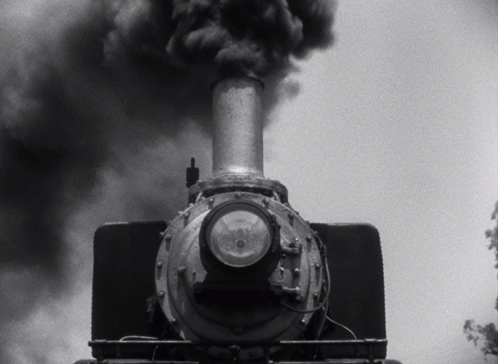

Shanghai Express

The Josef von Sternberg/Marlene Dietrich teaming. The Blue Angel, featured on my list in 1930. The pair famously made a series of Hollywood films together, all built around the glamor of Dietrich. For me, the best of the bunch is Shanghai Express. It has a stronger script than the others, being set on a train traveling from Beijing to Shanghai during the Chinese Civil War (which had started in 1927). The device of a group on a journey lends the film both unity and suspense. It’s basically a thriller with a romance included. There are more characters than in some of the other Dietrich films, the typical bunch of eccentrics for such journey-plots lending interest, humor, and pathos along the way. Dietrich’s character is strong and likeable. She pursues the man she loves, but on her own terms while he stands around cluelessly keeping his upper lip stiff.

Then there are the incredible visuals. The set design is even more dense than usual for a von Sternberg film. The train windows, both exterior (top) and interior (above) are used brilliantly, and the rebel headquarters where the group is trapped for much of the second half has hanging gauze and stairways that create a complete contrast with the train scenes.

And the Oscar mentioned above went to … Lee Garmes, whose five films in 1932 also included Scarface (see below). Apart from his photography of the settings, he shows off with with other dazzling moments, including an extraordinary tracking shot following an official along the crowded platform for nearly the entire length of the train.

Needless to say, the glamor shots of Dietrich are among the most beautiful ever (Garmes also shot Morocco and Dishonored).

In general, the train station scenes are spectacular and give a remarkable sense of authenticity. Speaking of which, all the extras and minor characters seem to be played by Chinese, or at least Asian people. Anna May Wong has a prominent role as Hui Fei. Whether casting Warner Oland as the rebel leader Henry Chang would count today as “whitewashing” is up for debate. He was born in Sweden but claimed some Mongolian ancestry (so far unproven).

The Criterion Collection has the set of six Dietrich/von Sternberg films on Blu-ray and DVD. (My frames were pulled from an old TCM DVD pairing the film with Dishonored. TCM now offers Shanghai Express by itself on DVD or Blu-ray.)

A Farewell to Arms

The second Oscar-winner of the three mentioned above was Charles Lang, for his cinematography of A Farewell to Arms. (The film also won the third Oscar, for sound recording.)

Frank Borzage has been a staple of these ten-best lists, with Lazybones (1925), 7th Heaven (1927), and Lucky Star (1929). This may be his final appearance in these year-end lists, with growing competition internationally.

A Farewell to Arms adapts Hemingway’s novel of World War I. Gary Cooper plays Frederic, an ambulance medic who spends his spare time drinking and visiting brothels with his friend, Italian Dr. Rinaldi (Adophe Menjou). He meets Catherine, a nurse, at a party, and they fall immediately in love, succumbing to passion under the assumption that war’s uncertainties may not give them another chance. Becoming pregnant, Catherine departs for Switzerland to have the baby, but her letters to Frederic and his to her, are returned to sender. Frederic risks a firing squad by deserting and desperately trying to find her.

Like Trouble in Paradise and other 1932 films, A Farewell to Arms benefited from the fact that the self-censorship Hollywood studios instituted under the Production Code (aka the “Hays code”) in 1933 was not yet in force. The result is a grittier and more honest look at life in wartime than would be possible in later years. Apart from the quite restrained brothel scene (above), there is considerable emphasis on the forbidden unwed motherhood rife among the nurses Catherine works with.

The two stars make a convincing romantic couple of the kind Borzage had become famous for, and the cinematography is lovely. Lang, too, was an expert at creating glamorous images.

Amazon would very much like you to watch the film for free with ads or with a subscription to Paramount+ or with a free Fandor trial or by paying $2.99. Once you scroll past those enticements, you can find Kino Classics release of a Blu-ray or DVD in a remastered version by George Eastman House. It seems a bit overly dark to me, but maybe the original nitrate copy was, too.

Scarface

I have to admit that gangster films are not my favorites. Still, there are outstanding films in the genre, as the presence of von Sternberg’s Underworld on my 1927 list indicates. The early 1930s established the genre solidly, and Scarface stands out among the other classics examples of the time. I have not seen the two other such classics still commonly watched, Public Enemy or Little Caesar, for a very long time, but I recall not being very impressed.

Scarface marks Howard Hawks’s first appearance on one of my lists. It’s not up to his greatest films of the 1930s, Twentieth Century and Only Angels Have Wings (and some would say Bringing Up Baby).

One thing that makes Scarface stand out for me is its considerable use of humor, which seems unusual for a gangster film. Paul Muni, so dignified in his prestigious bio-pics of this same period, lets go and struts with aggressive arrogance, lets go in fits of rage, and makes Tony Camonte a figure of fun with his accent (“That’s putty nice”) and flaunted ignorance. When the woman he’s trying to impress and seduce remarks sarcastically that his clothes are gaudy, he delightedly takes it as a compliment.

The comic relief flirts with slapstick in the figure of Camonte’s “secretary,” who is illiterate, inept, and downright stupid. According to the AFI Catalog, his character name is Angelo, though Camonte addresses him as Dope. There’s a running gag of him being unable to get basic information from callers. At one point during a raging gunfight in a restaurant, he struggles to hear a caller’s name, unaware that a tank behind him has been pierced and is dousing him.

The film also has its visual pleasures. It was one of five films, along with Shanghai Express, that Lee Garmes lensed in 1932. The cinematography is appropriately less glamorous than in Shanghai Express, but it’s dark and occasionally beautiful, as in the hospital-invasion scene at the top of this section.

Many films of the early 1930s start off with an impressive moving-camera shot, presumably to show off before settling down into scenes with standard continuity cutting. Scarface has quite an impressive opening, with a plan sequence leading up to the first act of violence.

It begins with a low angle of a streetlight going out, and then tilts down and tracks rightward past a milk delivery cart and a sign that establishes the locale.

Continuing rightward, it reaches a tired janitor who removes a sign informing us that a stag party had been held there the night before. The camera tracks rights as he starts to clean up.

The camera follows through the wall and continues as he tackles the job in a room festooned with streamers–possibly an homage to the big party scene in Underworld. One artifact of the party that he finds is a brassiere that has lost its owner.

As he pauses, the camera leaves him to pan right and track in on a gang boss and two of his men talking about a potential danger from a rival gangster. He declares that he doesn’t want war and is satisfied with the money he’s making.

The men stand, and the boss promises an even bigger party in a week. Thus for a gangster, he seems a decent sort, not willing to stir up violence against those seeking to invade his territory.

The men leave, and the camera follows the boss across the room and into a phone booth. He starts to make a call.

The camera glides past him and away off to the right, where it picks up a menacing shadow in the next room.

It follows the silhouette as the unknown man walks toward the corridor where the phone booth is. Silhouetted against a translucent window, he pulls a gun, fires it, polishes it with a handkerchief, and throws it on the floor. (This sort of offscreen or partially offscreen treatment allows the violence to be less explicit, a ploy that continues throughout the film.)

As the killer disappears, the camera tracks back to the left, revealing the boss’s body. The janitor enters, sees it, takes off his work clothes, and tosses them in the phone booth.

The scene ends with a pan left to follow the janitor as he hurriedly moves through the mess and leaves.

My frames were pulled from the Universal Cinema Classics DVD, a release which has since come out on Blu-ray. (Amazon still has the same edition on VHS!)

Love Me Tonight

So many of the early 1930s musicals were stagey. The review musicals were series of numbers without a connective narrative (convenient because they could be popular abroad without dubbing or subtitling) or backstage musicals where a “put on a show” premise also led to numbers on a stage. But with the growing freedom of the camera and editing, the musical could become something more.

Love Me Tonight feels like a wildly enthusiastic celebration of that new freedom. The story is a modern Ruritanian romance. A Parisian tailor, played by Maurice Chevalier, travels to a country chateau to collect money owed him by a client, who is a member of the aristocracy. While on his way, Maurice bumps into the debtor’s sister, Princess Jeanette, and falls in love with her without realizing who she is. Once at the chateau, he is mistaken for a Baron and proceeds to charm the Princess’ entire family and gain her love–until his lowly birth is discovered. Throughout, the dialogue is witty and the music and songs, by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

Much of the high spirits of the film arise from the fact that the songs are not sung by one or two people in a single locale. Instead, the music starts out in this limited way but passes along to other characters, spreading infectiously through a household or across a countryside. The process begins on a morning in Paris, as the city wakes up and goes to work. Gradually the rhythmic sounds of various activities build up to a symphony made of sound effects: a woman’s broom against a pavement or two cobblers’ hammers striking in counterpoint.

The first actual music when a man getting married that day picks up his formal outfit and Maurice sings about his work in “Isn’t It Romantic?” The groom goes out singing it, and it passes to a taxi-driver and then his fare–who happens to be a composer. Cut to a train, where he hums the music and writes it down (top of section), overheard by a group of soldiers; cut to a field where they march along singing it, and so on, until we reach the chateau and are introduced to the Princess, also bursting into “Isn’t It Romantic?”

Upon meeting Jeanette, Maurice woos her by singing “Mimi” to her. Here it’s a straightforward solo, though one that is filmed in an unusual fashion with Maurice singing and Jeanette reacting in shot/reverse shot directly into the camera.

Once at the chateau, Maurice apparently sings the infectious “Mimi” for the family and guests since there is a montage moving among them as they all cheerfully warble the song in their respective rooms. The same thing happens still later, when Maurice’s low birth is discovered; the song “The Son of a Gun Is Nothing but a Tailor,” similarly spreads throughout the building, including to the servants, who show a snobbery equal to that of their masters. Who can resist lyrics like those sung by a washerwoman?

Down upon my hand and knees/Washing out his BVDs/Is a job that hardly please me./If I had known I would have tore/The buttons off his panties for/The son of a gun is nothing but a tailor!

Overall one gets a sense that music and singing are irrepressible and ripple outward from the soloists to infect everyone within hearing distance.

Of course once Maurice has been thrown out, Jeanette decides to defy her family and races after his train on horseback. Mamoulian throws in some Soviet-style compositions as she heroically stands on the tracks and forces the train to stop.

Apart from its infectious style and music, Love Me Tonight has a wonderful cast, with Charles Butterworth as Jeanette’s wimpy but titled suitor, Charles Ruggles as the debtor son, Myna Loy as the man-hungry younger sister, and C. Aubrey Smith as the curmudgeonly father who becomes downright jolly under Maurice’s influence. Sheer entertainment.

Love Me Tonight is available from Kino Lorber on DVD or Blu-ray.

Hooray for the Rest of the World!

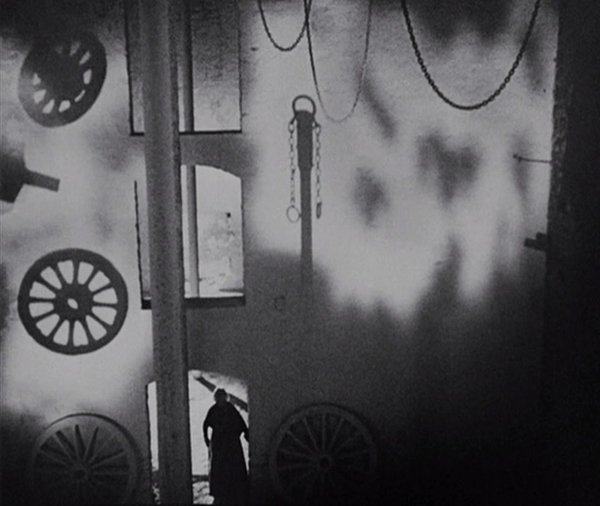

Vampyr

Two masters of cinema made vampire films a decade apart. I dealt with Murnau’s Nosferatu in the 1922 entry.

The two films could hardly be more different from each other. Murnau’s film was a plagiarized version of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula. He followed the original very loosely, cutting out most of the characters, including Van Helsing and hence the entire lengthy investigation process. Dreyer may well have known Murnau’s film, but it is hard to detect any influence or inspiration apart from the use of a book as exposition. The Universal version starring Bela Legosi was still in production when Dreyer finished shooting Vampyr. Instead, Dreyer drew even more loosely from the collection of horror-fantasy series short stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, published as In a Glass Darkly (1872).

Dreyer seems to have taken a few ideas from the stories, but does not use the narratives associated with those ideas. The notion of a female vampire is probably derived from one of the stories, “Carmilla,” though Le Fanu’s vampire is young and beautiful, while Dreyer’s is an elderly woman, Marguerite Chopin. The collection of stories is presented as having been case studies collected by a Dr. Hesselius, a researcher of the arcane. Allan Gray may be inspired by Hesselius, though he does no evident research and reacts in fear in most cases where he encounters anything strange and grotesque. Gray’s dream of being trapped in a coffin and carried off to be buried comes from “The Room in the Dragon Volant.”

On the whole, though, one of the most striking things about Vampyr is how little it adheres to the conventions of the vampire tale. It is not told as a collection of documents, as are Le Fanu’s stories (“Carmilla”is told in first person by Laura, the heroine and victim of the vampire) and Dracula (a collection of documentation by gathered by several characters). As in Nosferatu, a book is included to help present the “rules” of vampire stories, but the book is not written by Gray. It is given to him by the old Chatelain. The premises that vampires must travel in coffins full of dirt or will be killed if exposed to sunlight, so important in Nosferatu, are ignored here. Actually, the intention seems to be that Chopin is active mainly at night, but since the entire film was shot in murky daylight, it’s difficult to to tell night from day. Vampires also tend to be of noble birth, and we usually find out something about their family history. Chopin seems to be a local woman who somehow became a vampire.

To create a creepy atmosphere, Dreyer has Gray wander about observing menacing, unnatural, or unexplained phenomena in the neighborhood of the village of Courtempierre. These are not phenomena conventional to vampire stories, so they seem as mysterious to us as to Gray. Much of what Gray observes is never explains. Gray sees numerous shadows and reflections of beings who are not visible. He follows the shadow of a peg-leg man until it finally rejoins the soldier who should be casting it. Most vampires live in crumbling Gothic castles, but Chopin seems to have made her headquarters in a dilapidated factory of some sort. (Dreyer chose a deserted plaster factory whose white walls would show off the shadows cast on them.) Her main minions, a sinister doctor and the one-legged military man apparently do whatever they do there, waiting to do her bidding. As the images above and on the right below show, Dreyer creates a mysterious air to the building through the circles and curves of large gears, wheels, and hanging chains.

Beyond such motifs, there are the actors’ unpredictable exits and entrances into the frame during camera movement and the eerie offscreen sounds that hint at something disturbing happening nearby. David has analyzed all this in detail in his book, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (out of print but available from second-hand book dealers).

For the ending, Dreyer draws upon the convention of a stake through the heart as the way to kill a vampire. It isn’t Gray that figures this out. A remarkably passive protagonist, he sits dreaming of being buried alive while the old servant, initially a minor character, reads the Chatelain’s book, gathers the needed equipment, and initiates the task of the staking of the vampire in her grave.

The 1998 restored version of the film is available from The Criterion Collection on DVD or Blu-ray, with a particularly good set of supplements. These include a visual essay by Danish expert Caspar Tybjerg that deals in more detail with the influences of previous vampire literature and films on Dreyer’s work; I have drawn upon it for some of the information above. Vampyr also streams on The Criterion Channel, accompanied by some of these supplements as well as a video essay by David, “Vampyr: The Genre Film as Experimental Film.”

Boudu Saved from Drowning

Jean Renoir entered this list in 1931 with La Chienne. Although a grim melodrama for the most part, the film provides put-upon accountant Maurice Legrand with a happy ending as he leaves home and becomes a jovial tramp.

Boudu, the self-centered, careless tramp at the center of this film, is presumably not Legrand, despite being played by the same actor, Michael Simon, and Boudu Saved from Drowning is not a sequel. It almost could be, but this time the genre is comedy.

The opening sets Boudu up as an unusual tramp. He is not begging, and when a little girl offers him a small bill, he asks what it is for. “To buy bread,” she replies. Soon Boudu does beg by opening a car door for a rich man, and when the man can’t find any money in his pockets to tip him, Boudu hands him the small bill “To buy bread” and walks away.

Unexpectedly, Boudu jumps into the river in a suicide attempt. Lestingois, a prosperous bookseller whose shop and apartment are across the street, witnesses this and rushes out to dive in and save Boudu. He succeeds, receiving praise from the onlookers as a bourgeois who would take this trouble for a mere tramp. Lestingois is fascinated and amused by this “perfect tramp” and takes him in, offering him dry clothes, food, and a sofa to sleep on for the night, much to the disgust of his wife.

Boudu’s antics delight Lestingois, who treats him somewhat like a pet dog (top of section). He also gives Boudu a lottery ticket, which predictably will become a vital plot device later on. The tramp, however, disrupts the routine of the household–in particular sleeping in a spot that prevents Lestingois from making his nightly visits to the maid Anne-Marie.

Boudu lingers on, seeing this cushy home as a good setup; he tries to fit in by shaving his bushy beard and trying to dress respectably. He is utterly uncouth, however, shining his shoes on the wife’s bedspread, and knocking things off shelves, and causing a flood by leaving water running in the kitchen. Lestingois ultimately gets fed up with him–but in the nick of time Boudu wins the lottery and the attitude of the household changes. Anne-Marie, who supposedly loves Lestingois, suddenly becomes engaged to him.

On the wedding day, however, as the happy couple are in a rowboat on the river, Boudu upsets the boat and floats away to resume his old life as a tramp.

Stylistically the film is distinctly Renoirian. He shot his exteriors in Paris streets and parks, seemingly concealing the camera in some cases. A telephoto lens captures Boudu wandering along the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine, with the other people presumably ignoring him as a real tramp.

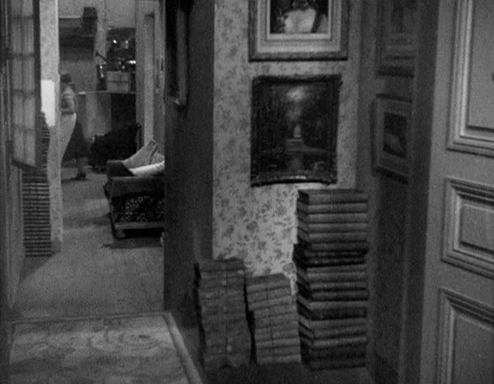

In a modest way, Renoir used the sort of roving camera movement that he would later develop into a major feature his late-1930s masterpieces. One scene starts with Lestingois and his wife eating a meal along with Boudu, seen from a distance down a hallway. As Anne Marie finishes serving, she exits left, and the camera moves left into the next room, where she is glimpsed walking toward the kitchen. It continues moving and stops briefly as Anna Marie enters the kitchen and puts down her tray. As she comes forward to the kitchen window, the camera tracks closer to the foreground window and stops, still at a distance as she talks with an unseen neighbor.

Boudu Saved from Drowning is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection and streams on The Criterion Channel (along with some supplements).

Wooden Crosses

Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses is this year’s masterpiece unknown to most modern viewers, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. I discovered the film through The Criterion Channel. David and I were relatively early in our “Observations on Film Art” series of supplements–early enough that the service was still called Filmstruck. In picking a film for a video essay, I thought it would be helpful to choose titles that were obscure but very much worth calling attention to.

One such film on the Criteron list was Wooden Crosses. I was dubious about it, since my only association with Bernard’s work was the 1924 historical epic, The Miracle of the Wolves, which I had seen back in my post-graduate days and found pretty turgid. Nevertheless, I gave Wooden Crosses a try and was bowled over by it. My video essay, “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses,” became number 16 and is available to subscribers.

In some ways Wooden Crosses is France’s great anti-war film of the early 1930s, following Hollywood’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Germany’s Westfront 1918, both of which were in my top ten for 1930. For me, it’s the best of the three.

The film begins with stock footage of Parisian crowds cheering the young men signing up to fight and marching off to war. Like The Big Parade, it introduces the war from well behind the lines, as new recruits arrive at a farmyard where the more experienced troops are billeted. The action takes place shortly after the Battle of the Marne in autumn of 1914; it was won by the French, but did not succeed in achieving ultimate victory. In Wooden Crosses, the experienced men scoff at the recruits for having arrived too late to experience any fighting.

Their optimistic assessment proves wrong, and the group is ordered to march to the front-line trenches. The result is an impressive sequence shot at night as the group goes through open areas, woods, and finally ends neck-deep in the trenches looking out across no man’s land in the darkness. As my video-essay title suggests, there is a considerable amount of night footage in the film. One point I make in that essay is that the epic footage in the film made an impression in Hollywood:

In 1935, the head of the newly merged 20th Century-Fox studio, Darryl Zanuck, bought the North American rights for Bernard’s film. He didn’t intend to release it theatrically. Instead, he realized that the spectacular battle footage was beyond anything that the studio could afford, and he wanted to reuse it.

The film it was to be used in was Howard Hawks’s The Road to Glory, released in 1936. Hawks, however, wasn’t just keen to use the battle footage. Like me, he seems to have admired the many night scenes. He said of Wooden Crosses that it had “Some fabulous film in it, marvelous scenes of great masses of people moving up to the front and through trenches—wonderful night stuff.”

The group of soldiers are quickly and marvelously characterized, notably by Charles Vanel as the group’s quiet, sensible Corporal and Gabriel Gabrio (Javert in Bernard’s Les Misérables) as the sarcastic, boastful Sulphart–a key source of comic relief in the film. Graduallynew volunteer Gilbert Demachy emerges as our main point-of-view character, though the others are kept prominent. There is a suspenseful series of scenes as they hear the sounds of German sappers tunneling below their dugout to lay mines. They are ordered to stay put, as there is plenty of time before the explosions, but as we discover, this is an example of a common motif in these films: the incompetence of the leadership.

One of the film’s most impressive aspects is the epic recreation of battle scenes. There’s no stock footage here, and there are shots over vast areas of no man’s land with explosions going off among the actors.

The climactic battle goes on and on–ten days, as repeated superimposed titles inform us–and conveys the relentlessness of the struggle that the group undergoes.

The battle ends in a long, tense scene, ironically set in a cemetery where many of the graves have been blasted open. These substitute for trenches as the men hunker down under German attack.

As with some of the other films on this year’s list, the cinematography of Wooden Crosses is extraordinary. It was shot by Jules Kruger, who had worked with major French Impressionist directors, notably Marcel L’Herbier on L’Argent and Abel Gance’s Napoléon, the latter of which no doubt gave him considerable experience with epic battle scenes. His most famous films after Wooden Crosses were La belle équipe and Pépé le Moko.

The Criterion Collection did a great service by releasing Wooden Crosses paired with Bernard’s Les Misérables in their Eclipse series. It also streams permanently on The Criterion Channel along with my video essay linked above. (New Year’s resolution: watch more Bernard films. I should give The Miracle of the Wolves another chance and set aside plenty of time to watch Les Misérables, a three-feature serial adaptation of the novel that clocks in at 281 minutes.)

I Was Born, But …

Yasujiro Ozu makes his third appearance in a row on these lists (see here and here for the first two). If I were to live to 102 and if I were still posting these lists, his last film would be on the 2052 list. That’s unlikely, but even so, he will probably be the director most represented on these lists as long as this series continues. I am still pondering whether to give him three spots on the 2023 list or just group his three masterpieces from that year as tied for a single spot.

I Was Born, But … was the first of Ozu’s silent films to become available in the West, and it is still probably the best known. So many of his early films are lost, but this may be the one where he achieved the perfect balance of humor and poignancy that characterizes so many of his best films.

Ozu is known for creating stories centered around the stages of life, often expressed as seasons in their titles, such as Late Spring‘s focusing on a daughter pushing the limits of marriageable age to care for her elderly father. His surviving early films often dealt with students or recent graduates struggling as “salarymen” in the job market of the Depression. In this film for the first time he shows the woes of the salaryman largely from the viewpoint of his children. Many of Ozu’s films are based on relations between parents and children young or grown. Those that dealt with young children were among his masterpieces: Passing Fancy, The Only Son, There Was a Father, Record of a Tenement Gentleman, and Ohayu.

The salaryman films deal with the difficulties of getting jobs, competing with colleagues, and surviving on meager wages. I Was Born, But … adds the problem of the subservience and even humiliation a salaryman sometimes undergoes and how it affects his family.

The story unfolds in parts that to some extent echo each other. Early in the film the two sons are bullied at school by the son of their father’s boss. They manage to defeat the bully and in a show of bravado boast that their father is the best in the world.

Later the family is invited to a gathering at the home of Yoshii’s boss, who shows some home movies of his employees showing off for the camera. These include Yoshii making faces and playing the fool, obviously at his boss’s insistence. The sons’ delight in seeing their father on the screen fades as they realize that their father has been humiliated and is not the great man they boasted about. Implicitly, Yoshii is being bullied as well but must submit in order to please his boss.

In an angry confrontation with their father, the sons accuse him of having proved himself not to be the man they had looked up to. The confrontation ends in their refusal to eat or speak to their parents. The parents admit to each other that their life is disappointing and not one they would wish for their children. The quarrel soon ends, with the boys accepting that their father is not the greatest.

As with That Night’s Wife (1930), Ozu is already using some of the techniques that would be part of his style for his entire career. For example, there is a transition between scenes that uses graphic values and objects in a series of images that do not behave like ordinary establishing shots.

I Was Born, But … is available in another DVD set in The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse series, “Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies.” The other two are the charming Tokyo Chorus and the wonderful Passing Fancy (which will definitely appear on next year’s top ten). Along with a slew of other Ozu films, it also streams on The Channel. Many of you know David’s book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema; it’s long out of print but available through open access on the Center for Japanese Studies Publications site (with the frames from the color films in color!).

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?

Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe, scripted by Bertolt Brecht, was a bold pro-Communist film made in the year before the Nazis swept into power.

Kuhle Wampe, named for the workers’ camp in which much of it is set, starts with the dire situation for the working class in Depression Germany. A typical family is singled out, with the son returning home after one of many fruitless searches for work (below). His parents blame him for his failure to find work in a society where unemployment is rampant. Their anger drives him to suicide. A neighbor woman remarks resignedly to the camera, “One fewer unemployed.”

The boy’s sister Anni becomes one of the main characters. Another is Fritz, her boyfriend, a leader in the labor protests in a local factory. When Anni becomes pregnant, the pair split up but eventually reunite when her family is evicted and moves into the tent city of the title, run by a Communist group (above). Communism is portrayed as a solution to the problems presented earlier. A lengthy sequence at a Communist youth sports festival emphasizes the happy life on offer by the Party. In the final scene, directed by Brecht himself, Anni and Fritz have an argument about the world’s financial dilemma with some middle-class passengers.

In 1933, Brecht fled the country, eventually ending up in Hollywood, and Dudow was expelled from Germany, only returning after the war to help found the Communist-run East German film industry.

As far as I can tell, the only DVDs or Blu-ray discs available in the US are imports and may not play on encoded machines. (It’s not even on YouTube!) For those with region-free players, the BFI’s release in either format seems to be best source.

Trouble in Paradise.

HEAT revisited

Heat (1995).

DB here:

Last year, Quentin Tarantino wrote a novel that extended and reconsidered the story of Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019). Less elaborate is Michael Mann’s new bestseller Heat 2, written with Meg Gardiner. It’s not his first reworking of his film’s world: Heat (1995) was itself an expansion of a TV movie, LA Takedown (1989). Tarantino’s book was fairly experimental, as I tried to show, but Heat 2 is more conventional, being, as reviewers have mentioned, at once a sequel and a prequel to the original film. Yet it has its own interest, I think, and it provides me a chance to revisit a film I’ve long admired.

You’ve probably seen the film, but I’ll warn you of spoilers when I come to discuss the book.

Two genres for the price of one

In the film, Mann blends two schemas for crime plots: the heist film and the police procedural. What’s remarkable is the way both get expanded and interwoven to a degree rare in each of the genres.

The heist plot centers on Neil McCauley’s gang, consisting of Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer), Michael Ceritto (Tom Sizemore), and Trejo (Danny Trejo). The team members are married, and two have children. McCauley (Robert DeNiro) is a loner, living by the code that by being free of personal ties he can escape when the police close in.

In the course of the film, the gang plans three scores. The first, in the opening, is a robbery of an armored truck. Being short-handed, McCauley has had to add another team member, the sociopath Waingro, to consummate the heist. This robbery will reverberate through the film. Waingro shoots one of the truck drivers, forcing the gang to kill all of them. By seizing the bearer bonds of the money launderer Roger Van Zant and trying to sell them back to him, the gang sets off a cascade of broken deals and violent confrontations. McCauley fails to kill Waingro as punishment for damaging the heist, and Waingro emerges to help Van Zant stalk McCauley.

The second score, an effort to access precious metals, is aborted when McCauley realizes that the police are monitoring their preparations. The third score is a brutal bank robbery in which the team is virtually wiped out, with only McCauley and Chris surviving.

The heist plot adheres to many of the phases I’ve sketched in an earlier entry on the genre. The jobs are set up by the fence Nate and the computer whiz Kelso. The gang meets to plan each attack, with a division of labor among them. As often in the genre, the private lives of the robbers intervene. Chris, a gambling junkie, is in a fraught marriage with Charlene (Ashley Judd). Before the last score, McCauley advises Ceritto to walk away, since his wife Elaine takes good care of him. For the bank job McCauley recruits a prison pal Don Breedan (Dennis Hastert), whose wife Lilian (Kim Staunton) tries to sustain his effort to hold a job. And after Waingro kills Trejo’s wife Anna, the fatally wounded Trejo feels nothing left to live for. Most risky of all is McCauley’s growing love for Eady (Amy Brenneman), who makes him inclined to relinquish his solitude and unite with her after the bank job.

Braided with the heist plot is an investigation plot centering on homicide lieutenant Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino). He’s brought in through the armored-car murders and begins systematically to trace leads to the gang. In the usual procedural fashion, Hanna and his colleagues visit snitches, search records, tail and tape suspects, and gradually identify the gang. It’s their botched surveillance that induces McCauley to drop the second score. There emerges a game of tit-for-tat, as the gang in turn surveils the police and use their informants in the police to identify Hanna.

Police procedurals often fill out the action with scenes of the cops’ personal lives, and here that function is fulfilled by a portrait of Hanna’s failing marriage to Justine (Diane Venora) and his effort to nurture Lauren (Natalie Portman), their teenage daughter from another marriage. As the robberies test the family relations of the crooks, Hanna’s commitment to the investigation drives home to Justine his emotional distance and his refusal to open up to her about how he reacts to the crimes he encounters. Further intertwining the two plotlines, Hanna must also investigate the latest in a string of serial murders of prostitutes. We will learn that the killer is Waingro.

We might think of Hanna as the protagonist, with McCauley as the antagonist. But the weight given McCauley and his plotline inclines me to say that the film has two protagonists. Each is an antagonist to the other, with subsidiary antagonists (Waingro, Van Zant) adding pressure to the conflicts. Each man stands out, of course, by virtue of the presence of major stars. The performances are carefully calibrated. As McCauley, Robert DeNiro underplays to the point of paralysis: he acts mostly with the space between his hairline and his eyebrows.

By contrast, Al Pacio’s Hanna is full of swagger and bravado, using what Mann calls “manically extroverted” gestures and speech to intimidate others. But that’s on the job. At home, he’s taciturn, justifying his impassivity there as a way to preserve his angst and keep his edge for the street.

Mann’s screenplay teases us with brief confrontations between the two men. One takes place via surveillance video during the second score.

The most famous encounter is the celebrated diner scene, handled in protracted over-the-shoulder views. Here Hanna is much more subdued, modulating his eye movements to match McCauley’s constant scanning of the room.

The two plotlines culminate at the airport. McCauley interrupts his escape to kill Waingro and, reverting to his “discipline” of abandoning personal ties, must leave Eady alone. But he’s pursued by Hanna for a final shootout.

Apart from its binary-protagonist structure, the sweep of the film also makes it something of a network narrative. There are a great many characters and locales, and nearly every scene is elaborated in such physical detail that we have a wide-ranging survey of vivid personalities and situations. I haven’t mentioned the memorable informers whom Hanna interrogates, or Charlene’s louche lover Marciano, or Dr. Bob, the veterinarian who patches up the wounded Chris. Even the smallest roles (often played by recognizable actors) gain a memorable intensity. The breadth and depth of the story world suggests that the film might be a prototype for the “mosaic” structure of TV series like The Wire (20002-2008).

Work/ life imbalance

Narratives cohere largely through patterns of causality. One incident triggers another. But narratives also depend on parallelism–likenesses and difference among aspects of the story world. Parallels can draw comparisons among characters, locales, and situations. Michael Mann deliberately built Heat on parallels, as he points out in the 2005 DVD commentary track.

Most obvious is the comparison of Hanna and McCauley as men devoted to their work, at the expense of intimate relationships. (Parallels between cop and crook are virtually a convention of the policier.) Each man’s willed solitude is virtually a compulsion, and they recognize their affinity in the diner conversation. That is prepared for by almost telepathic reverse angles during the video surveillance, with the lighting’s angles presenting them as virtually split.

One benefit of the expansive plotting of the film is the way it creates parallels to other men. Nate, Kelso, and Van Zant seem as isolated as McCauley, though perhaps not out of principle. At the extreme is Waingro, also a loner, but one who preys on women–a psychopathic alternative to McCauley’s asceticism.

The film multiplies parallels among the couples. Ceritto has a warm relationship with his wife, and Trejo chooses death over life without Anna. Chris, for all his faults, is deeply in love with Charlene. Breedan responds resolutely to Lilian’s urging to reconcile himself to the unfairness of his new job.

Likewise, Hanna’s police colleagues are happily married. In parallel scenes, we see the gang and the squad enjoying lively restaurant dinners. Even Hanna unbends enough for a dance with Justine. Only McCauley, alone with the other couples, is marked as without a woman–a status that impels him to call Eady and invite himself over.

There are plenty of other parallels, not least that of vulnerable daughters, with the suicidal Lauren and the teenage hooker Waingro kills. But the ones I’ve just examined point up a common feature of classical Hollywoood plotting. Often American studio films interweave two lines of action, one based on work and another based on romantic love. Problems arise when the two can’t be reconciled. The husband may be consumed by pressures of the job, while the wife is neglected and her wishes dismissed.

More specifically, cop films and novels often play out the conflicting demands of duty (danger, disruption of routine) and love (of wife and children). This is exactly the life that McCauley foreswears and that Hanna tries to negotiate. The crux of the film is that both McCauley and Hanna entertain the possibility of a normal life only to find that their nature precludes it. Their counterparts seem to have managed it, but each gang member is also drawn to the adrenalin high of crime. “For me,” Ceritto says, “the action is the juice.” They all go along with the bank heist, with ruinous results. To a lesser degree, they are on the same spectrum as McCauley and Hanna.

The work/life tension is sometimes made apparent on the level of style. After Hanna dances playfully with Justine, Mann interrupts with the next scene, in which Hanna blocks the distraught mother from approaching her daughter’s corpse.

There is deeper concern, to the point of passion, in Hanna’s frantic embrace of this grieving stranger than in his flirtatious dance with his wife.

In such ways the film spares sympathy for the women. The plot brings out the parallel situations showing women beseeching the men to face their problems. Mann also uses visual motifs to heighten the comparisons. The women express themselves in shots of their hands. A bold composition in which Hanna blocks Justine heightens her gesture of annoyed resignation, and later close-ups show Charlene’s secret signal to Chris and Eady’s tension while waiting at the airport.

Men’s hands have other things to do, although one close-up of Neil fetching water for Eady suggests the man he might become.

The climax of this motif comes at the end, as Neil lies dying and Hanna accepts his handclasp.

Scrambled backstory

Now the spoilers for the novel commence.

In planning Heat 2 Mann and Gardiner faced some problems. At the end of the film several characters are dead, including the fascinatingly reticent Neil McCauley. To revive him, you have to create his backstory. Chris Shiherlis and his wife Charlene survive, but she has chosen not to give him to the police, so he will have to find a new way to live. And how will you treat Vincent Hanna–his past, his future?

The authors found several solutions, some of which vary Mann’s usual narrative strategies. The novel is broken into time periods, but not in the manner of the prototype for such sagas, Godfather II (1974). After a prologue sketching the action of the film, one section is devoted to the immediate aftermath of the bank robbery. This alternates Chris’s escape from LA and Hanna’s inability to track him.

The authors found several solutions, some of which vary Mann’s usual narrative strategies. The novel is broken into time periods, but not in the manner of the prototype for such sagas, Godfather II (1974). After a prologue sketching the action of the film, one section is devoted to the immediate aftermath of the bank robbery. This alternates Chris’s escape from LA and Hanna’s inability to track him.

There follows a flashback to 1988, set mostly in Chicago, in which McCauley and his crew launch new heists. These scenes alternate with episodes of Hanna, stationed in Chicago, investigating some brutal home invasions. Eventually the gang executing the invasions learns of McCauley’s plans for a southwestern raid on drug smugglers and decides to rip off the team. The initiative is led by the monstrous Otis Wardell, a Waingro on steroids, who enjoys raping the women whose homes he invades. Ultimately Hanna’s frustration with his boss’s constraints on his investigation leads him to quit the force.

Most Mann films are resolutely linear in plotting. Apart from the time-jumping montage at the start of Ali (2001), he prefers chronological narrative. But now Heat 2 jumps ahead to 1995-1996. Chris has fled to Paraguay, where he takes up with a Taiwanese family involved in the arms trade and cybercrime. He falls in love with the chief’s daughter Ana, whom he helps gain power in the family.

The action returns to the southern border in 1988, with a showdown between Wardell and McCauley. In the course of a protracted firefight, Wardell kills Elisa Vasquez, the woman McCauley loves. Losing her is what plunges McCauley into the willed solitude that he projects in the film.

After another passage from 1996 bringing Chris and Ana up to date, the action jumps to 2000, after the events of the film. Everyone is now back in Los Angeles, and Hanna, remembering Wardell from his Chicago days, vows to capture him, while Chis vows to kill Hanna in revenge for McCauley’s death. Complicating things is the presence of Gabriela, Elisa’s daughter, who becomes a new target for Wardell. All these forces converge at a bloody climax.

Why did Mann break the prequel material into blocks and alternate the time periods? I suspect it was to maintain interest in the runup to the film’s action. If all the 1988 action preceded Chris’ 1990s career in Paraguay, we would have lost both McCauley and Hanna about a third of the way through the book. Chris would have had to carry a large central chunk of the story. Even as a soldier of fortune, he just isn’t as charismatic as Hanna and McCauley, so holding the resolution of the McCauley plotline in suspension keeps us turning the pages. Elisa’s death and McCauley’s devastation provides a strong lead-in to the film we have. Thereafter, the 2000 followup serves to wrap up nearly all the action. (The last line presents is a dangling cause that could lead to yet another sequel.)

The novel is less concerned with parallels than the film, although Ana’s frustration with the closed-in Chris matches that of Heat‘s wives. And Hanna’s fury at Wardell’s rape and beating of a teenage girl fuels his mission to find the gang, while thanks to a coincidence Wardell realizes that the waitress in a diner is the daughter of the woman he murdered in the desert. What knits the novel together most tightly is the premise that Hanna, McCauley, and Wardell were all in Chicago in the same years, but they were largely unaware of each other. We see links that the characters aren’t aware of.

This roaming-spotlight viewpoint is at work in the film as well, with the constant crosscutting of cops and crooks. But Mann and Gardiner take omniscience farther by penetrating the minds of the characters. Scene by scene we learn what the major characters are thinking, with some scenes containing several shifts of perspective. It would be as if the film gave us voice-overs from Hanna, McCauley, Chris, and others. The novel’s inner monologues remind me of Mann’s commentary track for Heat, which frequently draws larger conclusions and fills us in on what the characters are thinking. When Drucker pressures Charlene to give up Chris, Mann’s commentary reminds us that he’s trying to “build emotional solidarity” with her “despite having “a very short window.” Of Heat‘s two protagonists, he says:

These are the only two guys like each other in the universe. . . they are fully aware and conscious of who they are.

In the novel’s prologue the passage is:

Each navigated the future racing at him with eyes wide open. . . Polar opposites in some ways, they were the same in taking in how the world worked, devoid of illusions and self-deception.

The result is a narration that is, by the standards of Hammett or Elmore Leonard, over the top. On the same page, we get: “The detonation behind her eyes is seismic” and “For a second, she looks like she might explode.” Likewise, the perspective-shifting encourages scenes to be overelaborated; nothing is left to the imagination. But as with a lot of pulp writing, the novel has a raw power. We can treat it as a package, wrapping a Mann plot and dialogue in blunt, brash commentary.

Novel as script

A great deal of the appeal of a Michael Mann film is its richly textured surface. He is a “realistic” director insofar as he carefully researches a film’s milieu and takes pride in exact historical details. During a visit to Madison, he praised Dunkirk for Nolan’s attention to the Bakelite knobs on the aircraft. Yet Mann is also a pictorialist, always seeking striking, expressive shots that can de-realize the most familiar landscape, often through long lenses.

His early interest in video capture indicates both his realist impulse and his gift for abstract color design. Wanting to reveal LA at night in Collateral (2004), he wound up with night visions like nothing else on earth. Add in his talent for innovative film music. Heat‘s eclectic, melancholic score, so different from that of the routine action picture, is a big part of its power. So approximating a Michael Mann film on the printed page is far from easy.

Heat 2.0 tries. Written in the present tense, it has the staccato quality of a screenplay.

Gunfire. Deep. A rifle. Behind, them, rounds hit the connecting door from the far side. Somebody kicks it. Chris spins and fires a three-shot burst. They hear a body fall. More shots come through the wood, splintering it.

Reading it, you may find yourself hearing the dialogue in the voice of DeNiro or Pacino.

Ceritto glances around. The walls of boxes gleam in the spooky light. “Which one has the Holy Grail?”

Neil opens a gym bag. “Don’t matter. You find Jesus Christ, haul him out and hand him a sledgehammer.”

Hanna leans down into Alex’s face and grabs the crucifix in his right ear and rips it out through the lobe. Alex screams. Blood pours from the tear.

“Asshole!” Hanna shouts. “What the fuck do you think we’re gonna do? You are gonna flip, you dumb prick. You are gonna tell me everything I want to know, you cocksucker!”

He jerks Alex’s chin up, stares into his eyes, and shoves forward the cross. “The power of Christ commands you! I am your motherfucking exorcist. Tell me!”

Mann says he hopes to make a film of the novel. If he does, readers will hope that passages like these make their way into it.

Heat has proven to be an enduring modern classic. It’s encouraging that a followup to a movie nearly thirty years old can stir such widespread interest. Whatever happens to Heat 2, it shows that at age 79 Mann has not lost his lustre.

Nick James’s appreciative monograph on Heat offers many insights into the film. I discuss the heist genre and the police procedural in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots.

Heat (1995).

Enter Benoît Blanc: KNIVES OUT as murder mystery

Knives Out (2019).

DB here:

Now that a sequel, Glass Onion, has been announced for the Toronto International Film Festival, it seems a good time to look back at Rian Johnson’s first whodunit Knives Out. The effort has a special appeal for me because it chimes well with arguments I make in Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder.

I don’t analyze Knives Out in the book, but it would have fitted in nicely. The movie exemplifies one of the major traditions I study, the classic Golden Age puzzle, and it shows how the conventions of that can be shrewdly adapted to film and to the tastes of modern viewers. In addition, Johnson’s film supports my point that the narrative strategies of “Complex Storytelling” have become widely available to viewers, especially when those strategies are adjusted to the demands of popular genres. Historically, such strategies became user-friendly, I maintain, partly because of the ingenuity demanded by mystery plotting.

Needless to say, spoilers loom ahead.

Revisiting and revising

The prototypical puzzle mysteries are associated with Anglo-American novels of the 1920s-1940s, the “Golden Age” ruled by talents such as Dorothy L. Sayers, Anthony Berkeley Cox, John Dickson Carr, Ngaio Marsh, Ellery Queen, and many others–supremely by Dame Agatha Christie. Similar books are still written today, often under the guise of “cozies” because they supposedly offer the comforting warmth of familiarity. Golden Age plotting flourishes in television too, in all those (largely British) shows about murder in supposedly humdrum villages.

Knives Out relies on Golden Age conventions from top to bottom. A rich, odious family is overseen by a domineering patriarch, mystery novelist Harlan Thrombey. When he’s found dead in his mansion, apparently of suicide, his family members become nervous because each has a guilty secret. The conflicts are brought into focus when it’s revealed that Harlan changed his will so as to disinherit all his offspring. He leaves his fortune and his house to Marta Cabrera, the nurse who administered his medications and became his friend and confidant. Is there foul play? Investigating the case are are two policemen and the private investigator Benoît Blanc. They must decide whether Harlan’s apparent suicide is actually murder and if so, who’s the culprit.

Johnson organizes his plot around many classic techniques. In the Golden Age, writers tended to fill the action out to book length by adding more crimes, such as blackmail schemes or a series of murders. Both of these devices are exploited in Knives Out. Marta is apparently the target of an extortioner, and the family housekeeper Fran is the victim of a poisoner. The film also employs the least-likely-suspect convention (a favorite of Christie’s) and a false solution (another way to fill out a book). Johnson supplies traditional set-pieces as well: the discovery of the body, a string of interrogations of the suspects, the assembling of suspects to hear the will read, and a denouement in which the master sleuth announces the solution by recapitulating how the crime was committed.

The conventions are updated in ways both familiar and fresh. The sprightly music and the flamboyant bric-à-brac of Harlan’s mansion deliberately recall Sleuth (1972), another reflexive, slightly campy revisiting of murder conventions. Johnson wanted to evoke the all-star, well-upholstered adaptations of Christie novels like Murder on the Orient Express (1974, 2017) and Death on the Nile (1978, 2022). But he has courted younger audiences with citations (the title is borrowed from Radiohead) and social commentary, such as references to Trump, neo-Nazis, and illegal immigration. The Thrombey clan’s inability to remember what country Marta came from reminds us of something not usually acknowledged about Golden Age classics: they often provided satire and social critique of inequities in contemporary society. (In the book I discuss Sayers’ Murder Must Advertise as an example.)

Like earlier Christie adaptations, Johnson’s film has recourse to flashbacks illustrating how the crime was actually committed. In Benoît Blanc’s reconstruction of the murder scheme, rapidly cut shots illustrate how the family black sheep Ransom sought to kill Harlan by switching the contents of his medicine vials, which would make Marta the old man’s murderer. But her expertise as a nurse unconsciously led her to switch the vials again, so she didn’t administer a fatal dose. This forced Ransom to continually revise his scheme, chiefly by destroying evidence of Marta’s innocence and trying to murder Fran, who suspected what he had done.

All of this is carried by the now-familiar tactic of crosscutting Blanc’s solution with shots of Ransom’s efforts, guided by Blanc’s voice-over. At some moments, the alternation of past and present is very percussive, with echoing dialogue (“You’re not gonna give up that,” “You’ve come this far”). For modern audiences, this swift audio-visual revelation of the “hidden story” is far more dynamic than a purely verbal recitation like that on the printed page.

Johnson tries for a more virtuoso revision of a classic convention in treating the standard interrogation of the suspects. Lieutenant Elliott’s questioning, followed by questions posed by Blanc, consumes an astonishing sixteen minutes of screen time. Such a lump of exposition could have been dull. But the accounts provided by Harlan’s daughter Linda, her husband Richard, Harlan’s son Walt, his daughter-in-law Joni, and Joni’s daughter Meg are brought to life by flashbacks to the day of Harlan’s death. Aided by voice-over, we get a sharp sense of each character’s personality while the mechanics of who-was-where-when during the birthday party are spelled out. Some flashbacks are replayed in order to alert us to disparities in the stories, which stir curiosity and set up further lines of inquiry. The technique isn’t utterly new, though; in the book I show that such shifts across viewpoints emerged in mystery films from the 1910s onward.

The pace picks up when, instead of sticking to one-by-one witness accounts, Johnson starts to intercut them, showing varied responses to the same questions.

The editing creates a conversation among the witnesses, as one disputes the testimony of another. This freedom of narration, mixing different accounts in a fluid montage, plays to modern viewers’ abilities to follow fast, time-shifting narratives.