Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Streaming media: All you can eat, until it eats you

DB here:

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas remarked: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

I wrote the preceding paragraph two years ago, and the Covid outbreak and enhanced technology have made the split between theatrical distribution and streaming distribution even sharper. (And as the Movie Brats predicted, multiplexes are raising ticket prices.) A crisis point was reached last month when Netflix glumly reported that instead of adding 2.5 million customers as it had expected, it lost some 200,000. Worse, the firm announced a likely loss of 2 million more in the next quarter. The news led Netflix stock to fall by over 30%, wiping out over $45 billion in value.

This stunning decline, coupled with Warner Bros. Discovery’s decision to cut the recently launched CNN+, sent shock waves through the industry. Stock values dropped for Disney, Warners, Paramount, and Roku as well, even though some had strong subscription growth. At the moment, disillusion seems to be settling in. A Wall Street analyst has noted:

We think the industry is facing a point of no return in which the economics of the old models look increasingly frail while the potential of the brave new world now appears overly hyped.

Discussions of mergers, acquisitions, and big company restructuring are ongoing, with layoffs already starting.

As researchers, we at The Blog try to see past current convulsions to larger patterns. But it seems plausible that we are approaching some significant changes. Without trying to predict much, and being no expert on streaming tech, I still thought I’d try to think through some ideas about the state of streaming and its historical significance.

An interim report

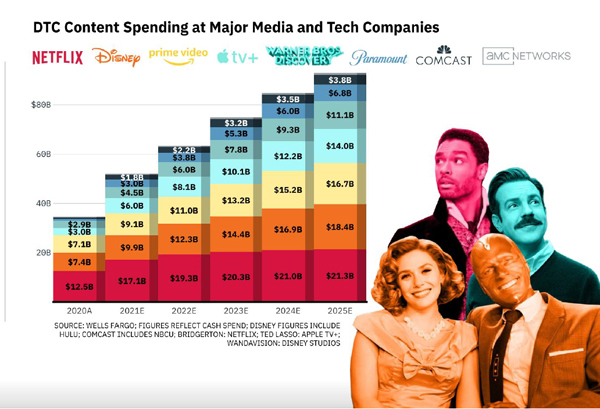

The Future of Content, Variety Intelligence Platform April 2022, p. 10.

Best to start with some basic information. Here’s what I came up with, all subject to correction and nuancing.

Streaming is now firmly established as a distribution/exhibition platform. It’s now the focus of all major US media conglomerates and it’s a market force every independent producer and company must reckon with. Broadcast television is waning. Viewership is declining, and this year saw a ten-year low in the number of pilot shows ordered by the networks. Cable subscriptions are likewise plummeting. Over the last ten years, cable channels lost 30-50% of viewers. Only the Discovery channel managed to grow, and live sports (e.g., ESPN) hung on, though damaged by the pandemic. Globally, streaming is growing rapidly, with both Hollywood majors and national and regional media firms plunging in.

Theatrical film, severely curtailed by the pandemic, is staggering. In nearly every country of the world, 2021 attendance was half or less that of 2017-2019. Studios are now releasing far fewer features, even in the crowded summer months. About 1000 theatre locations have not reopened since early 2020. Los Angeles has lost the Arclight and Pacific Theatres chains and the Landmark Pico theatre. In my home town a five-screen second-run house shuttered during the pandemic, and a six-screen multiplex is rumored to close soon.

As Lucas and Spielberg foresaw, the films that fill multiplexes are blockbuster franchises. So far this year, Spider-Man: No Way Home and Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness have done robust business, and exhibitors confidently expect big turnout for Top Gun: Maverick and Jurassic World Dominion. The surprise success of Everything Everywhere All at Once ($47 million box office) doesn’t mitigate the bleak prospects for most offbeat theatrical fare. Prestige films, romantic comedies, arthouse films, and many genre pictures can’t usually yield big enough returns, and the aftermarket–cable, DVD, and other ancillary outlets–which helped support them in the past scarcely survives.

Which leaves streaming as a primary source of filmed entertainment. At least 86% of US households access streaming services, either by subscription (SVOD) or as ad-supported services. The result is an immense amount of choice. You can browse studio libraries, imports, straight-to-streaming features (e.g., the latest Pixar releases) and series (e.g., Inventing Anna, Tokyo Vice).

Except for Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple+, the major streaming services are aligned with US entertainment conglomerates. Indeed, streaming made Netflix and Amazon entertainment behemoths, as attested by recent Academy Awards and Emmys.

Exact figures fluctuate, but the principal subscription streamers vary enormously in scale. At the beginning of this year, pre-meltdown, Netflix declared a global subscription base of about 220 million, with Disney+ at 196 million. Paramount claimed about 56 million (incuding Showtime and other offshoots), Discovery 22 million, and Peacock 24.5 million, including both paid and free. According to Amazon, over 200 million Prime members streamed material in 2021. As of March, Apple+ was estimated to have 25 million paid subscribers, with about twice that number benefiting from access via promotions (e.g., purchase of Apple hardware).

The simultaneous theatrical/streaming release (Dune, Wonder Woman 1984) is becoming rare as audiences return to theatres, but it remains an option (e.g., Firestarter). More common is a strategic delay far less than the usual ninety-day window that was common before the pandemic. The Batman opened in multiplexes on 4 March and was streaming 18 April. Universal and Paramount are prepared to send a feature online 17 days after theatrical release.

Fickle audiences and fluctuating “content” create churn. As a monthly subscription transaction, paid streaming lets consumers depart at will. Canceling cable subscriptions was difficult due to long-term contracts and obstreperous bureaucracy. Unsubscribing to Netflix or Apple+ is a lot easier. In addition, cable programming had a considerable stability, with long seasons and evergreen attractions. Studios signed extensive licenses for films and series, since cable was a perpetual money machine. Moreover, a movie might be available on several cable outlets. Now, however, the streaming industry faces audience churn.

Defections are common, especially among the young. An April survey found that nearly a third of Gen X subscribers and nearly half of Millennial and Gen Z subscribers have both added and dropped at least one streaming service in the last six months. Overall, nearly a third of subscribers say they have canceled at least one service in the same period. Web-experienced viewers are adept at hopping onto and off the latest thing.

Churn is accentuated by the exclusivity of the new media oligopoly. As the majors discovered the money to be made, they regained control of their library licenses. Netflix had The Office, its most popular attraction, until Warners took it back in 2019–soon after Netflix had renewed it for $100 million. The turnover is ongoing: this month Netflix lost Top Gun, the Ninja Turtles, the Muppets, Marvel TV series, and the first six seasons of Downton Abbey. The majors have gradually reasserted the exclusivity of their product.

As competition has intensified, streamers have been forced to acquire their own programming, both films and series. The pool must be refreshed to retain current subscribers and attract new ones. The problem is that once the new material has run its course, viewer loyalty can wane. This is especially true when the streamer dumps a full season of a series for bingeing: it encourages newcomers to sign up briefly and then defect. Disney has executed a powerful balancing act between legacy material and new offerings (Pixar features, Marvel spinoffs) that keep audiences faithful.

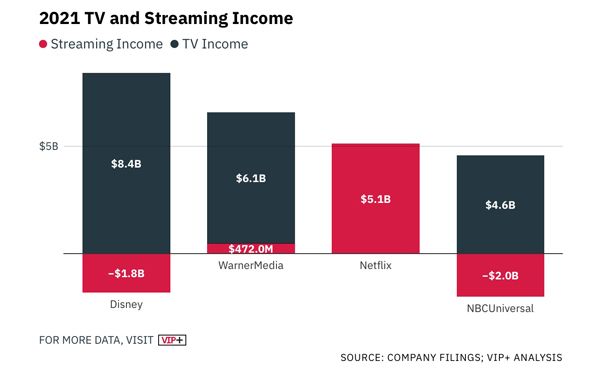

Streaming is not yet profitable. Broadcast and cable television are far more lucrative because they gain revenue from advertising and fees. Disney and Universal each lost about$2 billion on streaming in 2021.

Hence the concern over Netflix’s April report of decline in subscriptions. Streaming is its core business. A loss of $2 billion for the Disney conglomerate (parks, cruises, ABC TV, etc.) amounts to a rounding error. The majors’ deep pockets can sustain streaming enterprises for some time, but Netflix is far more vulnerable.

The streaming services are investing huge amounts in new “content.” The major providers are estimated to spend $50 billion acquiring projects this year. Producers are in a powerful position to demand big budgets to outmatch the competition. The costs are exacerbated by the high demands of talent, who now expect to be paid largely up front, since there is little opportunity for the deferred fees and back-end deals that depend on ancillary revenue.

No wonder then that several services have raised subscription rates. More drastically, in its current crisis Netflix has announced plans to offer an ad-supported tier of the sort already provided by Universal/NBC’s Peacock. Other services, Disney included, will probably shift to a similar option, especially since there is some evidence indicating that consumers will accept commercial interruptions in exchange for lower fees. Netflix also plans to control password-sharing, which helped it grow recognition but in the face of intense competition depletes its audience. It may be harder to combat the use of virtual private networks, aka VPNs, which allow roundabout access to region-based offerings.

One monetization strategy seems to be the rebirth of windows. Once a high-demand film is released to streaming, the service can add an upcharge for accessing it. Blockbusters like The Batman and the new Spider-Man trilogy were launched online with an extra fee for initial viewing. Over time, the prices fell gradually, just as in the old first-run/ second-run days. Even classics can benefit from premium treatment: The Godfather is free on Paramount+, but a rental costs $3.99 on Amazon Prime and Apple+. Arthouse fare is even more privileged; I paid $19.99 to see Drive My Car in its online release, though now it’s free on HBO Max.

It’s still TV

Bill Amend, Foxtrot.

In the late 2000s, streaming video entertainment was the province of mostly smallish, scattered companies like Twitch, Pluto, and others. Netflix and YouTube also took the plunge. Hulu, a consortium of Fox, Universal, and Disney, represented the majors’ initial effort to explore the market. As download speeds improved, problems with buffering and latency were overcome by new streaming protocols.

Soon enough, a familiar cycle emerged. Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch shows that mass information technologies (telegraph, telephone, film, TV) tend to consolidate into oligopolies. Major companies buy or kill off the competition. This happened with streaming, as one by one the big players came to the foreground. Netflix had early-mover’s advantage, having pioneered the distribution of DVDs by mail, and Amazon had a massive customer base in place already. The studios had helped Blockbuster wipe out small video-store chains, which had demonstrated the existence of a massive market, then turned their attention to selling discs directly to consumers. In 2019 the big players began to consolidate control over the expanding streaming landscape.

By acquiring other services (e.g., Paramount’s buying Pluto) and assembling proprietary components already in hand (e.g., WarnerMedia’s repurposing HBO Go), the firms have come up with integrated platforms. Disney+ launched in 2019, Peacock and HBO Max in 2020. Discovery+ and Paramount+ appeared in 2021, and Amazon bought MGM earlier this year. Sony, while licensing its film releases to its counterparts, has focused on animation by picking up Crunchyroll, which will absorb Sony’s Funimation service.

It’s early in the game, and it will take time for the companies to reassemble libraries that have licenses yet to expire. Doubtless many titles will be available for premium rental on rival sites, since no company wants to leave money on the table. Still, it seems clear that a considerable siloing of “content” will enable firms to enhance their power over their intellectual property. From this standpoint, we can think of streaming as a new phase in the development of home video.

In the earlier entry, I argued that home video formats gave the consumer a great deal of freedom. Even cable promoted “appointment viewing,” but tape, and then DVD, allowed the consumer a lot of flexibility. You could buy or rent a movie and watch it when you pleased. You could copy it too. Convenience is always a plus in a consumer item, and home video added to it a welcome price point: renting a tape or disc was cheaper than buying a movie admission, and in discount bins you could find a DVD for a few bucks.

With physical media, movies became manipulable by the audience. Ripping a DVD yielded a file that could be remade. Mashups, Gifs, and other transformations were feasible. Video essays changed film studies, and satire, homages, and fan analyses filled the internet. You could play with your movies.

Streaming withdrew this flexibility but offered greater convenience. A platform combines the array of a video store (think of those tiled pages as display racks) with push-button access. You still have the option of time-shifting, and you can share home viewing with others. But there’s no longer a physical medium. You don’t own or rent the film as object; you have bought access to it as a display, and only when you’re online. (“Buying” a digital copy is no guarantee of possession, if the service loses its license to the title.)

For decades, movie exhibition was a service business. We paid for the experience. Briefly, between 1980 and 2020, films became consumer artifacts as well. Ordinary folk enjoyed the sense of possession shared by film collectors of earlier decades. But with the decline of discs, we are once more paying for the experience while the object lies elsewhere.

Because of Hollywood’s preternatural fear of piracy, turning the artifact back into a service is a way to secure intellectual property. Not that people will stop trying to make personal copies. It’s possible to record streaming transmission, but the majors are counting on several factors. Just as people became tired of piling up DVDs they probably won’t watch, they could tire of filling hard drives with rips.

A few hardcore headbangers will enjoy sticking it to the man, but most people will reckon if you already pay for streaming the movie, why copy it? Given customer inertia and the convenience of streaming, why bother to pirate a movie that’s probably on streaming somewhere, available whenever you want? The trouble and expense of ripping may be greater than simply signing up for another subscription service. There are certainly overseas markets for pirated streaming shows, but as the companies expand their platforms abroad, piracy may diminish.

In sum, streaming has become the next step in the majors’ reassertion of control over their IP. It surpasses the old video store’s inventory, offers the convenience of click-ordering and time-shifting, and retains the advantages of in-home consumption. All we relinquish is ownership of a copy. Now that SVOD services are generating new attractions, providing long-running series with spaced-out hour-long episodes, and exploiting advertising-supported tiers, we are getting a version of fully on-demand cable TV.

We can glimpse this prospect in the demand for bundling, or aggregation. Customers’ biggest complaint is that there’s too much choice. The 200 channels of maximal cable are dwarfed by the streaming torrent. Nielsen estimates that as of last February there were 817,000 unique program titles available. Hence the emergence of streaming MVPDs, the “multichannel video programming distributors.” They provide a mix of movies, broadcast network series, classic TV, sports, and cable news. The best example is YouTube Live, which charges $64.99 per month, far beyond most of its SVOD competitors and reminiscent of classic cable fees. Yet YouTube Live is the most popular MVPD.

Add to this the number of FAST outlets, free ad-supported streamers such as Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Freevee, et al. With MVPDs these already constitute about a third of streaming offerings. One survey found that 34% of US consumers would prefer a free streaming service with 12 minutes of ads per hour. Streaming is starting to look like. . . well, just good old TV. The free platforms approximate broadcast TV, and the paid ones are cable reborn.

It takes time to make a classic

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill (2007).

Streaming demands a constant flow of new material, compared with the relative stability of broadcast TV, so the problem has been how to release it all. Netflix made a splash by dumping entire seasons at once, encouraging bingeing and getting immediate buzz and uptake. Viewers came to expect the big gulp. One survey found that over half of viewers under sixty now want firms to provide all the episodes of a series at once. But this strategy can damage long-term subscriptions by encouraging churn.

It also makes the product forgettable. Most direct-to-streaming films have a short shelf life. Does anybody watch War Machine (2017) or Bird Box (2018) now? Most auteur efforts seem to me to have had little cultural impact, not even Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019, with a mild theatrical release as well) or Soderbergh’s The Laundromat (2019). They came and went fairly quickly. A rolled-out theatrical film had an afterlife, it could circulate through the culture in many ways, and it could find niche audiences. Could The Godfather (1972) have its standing today if it were released straight to SVOD? Are there now “classic” streaming features?

This applies to art films too, I suspect. The international festival circuit allowed films to trickle from the big events to national and regional festivals over months, so outstanding films could build critical response and whet audience interest. Eventually some would find commercial distribution city by city. The pandemic compressed that process as festivals began to allow remote viewing of their screened titles, sometimes to audiences outside the locality. Kino Lorber’s Kino Marquee plan, which allowed simultaneous online access to new releases across the country, was a creative effort to maximize a film’s reach. Sponsored by local theatres, the plan in effect yielded a quick nationwide release on a scale that couldn’t easily be matched in pre-Covid days. It’s hard to imagine, though, that L’Avventura (1960) would have its standing today if it had played so quickly throughout the country.

Producers are belatedly realizing that the slow rollout characteristic of classic film distribution had the advantage of building audience awareness. A theatrical trailer is targeted toward habitual moviegoers and word of mouth. Theatrical releases garner promotion and extensive critical coverage that last longer than a Twitter alert. Theatrical screening can make a film an event–not always successfully, but at least it offers a chance. At a 19 May Cannes panel, a Swiss distributor pointed out that theatrical releases do better on streaming than straight-to-streaming ones.

The rationale is partly financial, of course. Here is the new head of Warner Bros. Discovery David Zaslav:

When you open a movie in the theaters, it has a whole stream of monetization. But more importantly, it’s marketed and builds a brand. And so when it does go to a streaming service, there is a view that that has a higher quality that benefits the streaming service.

There’s also the fact that a film on the big screen has a force that even a home theatre display can’t match. Another executive notes: “The undivided attention you get from an audience in a theater is where franchises are born.”

Classics, too. Even if most people see most films on monitors and personal screens, there need to be places for the proper display of them–living museums of cinema, in archives and cinémathèques but also in multiplexes and art houses. If streaming is making films ephemeral, we need to hang on to screening situations that let films claim our full engagement. If cinema becomes more like opera, as Lucas and Spielberg prophesied, let’s all become patrons and devotees, even snobs. Let films ripen over the years in a shared cultural space. Then we may get future masterpieces. Or so we might hope.

Thanks to Erik Gunneson, Peter Sengstock, and Jeff Smith for information and ideas.

Thompson/Bordwell online books now available for free

DB here:

For some years we’ve offered digital books for sale via our site. These are either original works, like Pandora’s Digital Box and our Christopher Nolan study, or updatings of out-of-print publications like Planet Hong Kong and On the History of Film Style. Those have been available through purchase via PayPal.

I was never comfortable with using that service, but its ubiquity favored it. Now that its chieftain, billionaire Peter Thiel, is bankrolling Ohio Senate candidate J. D. Vance and other mega-MAGA figures, we see no reason to add to PayPal’s revenues, not even the few cents it receives from a purchase here.

So starting today, all the books formerly for sale are free to all. They sit in a stack on the right of this page. They are unlocked pdf files, and can be read or downloaded as you wish. Click on whatever interests you.

Thank you to all our readers who purchased some books in the past. We hope that making other titles easily available will attract you as well. Thanks as well to those educators who have asked students to use these in course work. If you haven’t acquired any of these so far, you’re welcome to pick them up!

Thanks as ever to our web tsarina Meg Hamel for setting up our online book sales originally, and for liberating them today.

P.S. 17 May 2022: Some readers have noted that Peter Thiel may no longer have an association with PayPal, as he sold his founding interest in the company in 2002. But he may still be one of several stockholders. Still, if we’re in error, we regret it and apologize. We don’t regret highlighting his deplorable political activities. And we’re glad to release the books.

Wisconsin Film Festival 2022: A return to the theaters

Hit the Road (2021).

KT here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival ended last week. This was the first in-person festival after one cancelled (2020) and one presented through streaming (2021). Given David’s health situation, I was not able to attend many films, but here are some of the highlights that I caught.

Wisconsinite David Koepp visited the festival, bringing two films he scripted, Kimi (Steven Soderbergh, 2022) and Death Becomes Her (Robert Zemeckis, 1992), as well as one that inspired the former, Sorry, Wrong Number (Anatole Litvak, 1948). David and I had already seen Kimi on streaming, but I jumped at the chance to see it on the big screen. The sell-out crowd was utterly enthralled throughout, and David K. charmed them during an all-too-short Q&A session. I won’t say anything more about it, since David B. has blogged about it. I did enjoy two Middle Eastern films and the new Claire Denis. (Not the one about to be in competition at Cannes. The woman is certainly cranking them out.

Amira (2021)

In 2017, the Wisconsin Film Festival showed Mohamed Diab’s extraordinary Clash (2016), an epic restaging of the 2013 riots that brought down the Muslim Brotherhood government, all observed by a group of prisoners in a police paddy-wagon. I was excited to see that this year’s festival included Diab’s next film, Amira.

The new film is quite different from Clash. While that showed a cross-section of Cairo participants in the riots or simply bystanders swept up by the police, Amira centers on a personal drama of an extended family living in an unidentified occupied Palestinian area of Israel. (The film was shot in Jordan, so local landmarks would be no help in figuring out exactly where the family lives.) Amira’s parents have never consummated their marriage, since the husband, Nawar, is imprisoned for life, and his wife Warda became pregnant through semen smuggled out of the prison. Amira is officially the daughter of Nawar’s brother, but she is fiercely devoted to Nawar, going through elaborate security procedures to visit him in prison.

The plot gets going when it is revealed that Nawar has a genetic abnormality that rendered him sterile from birth. The close-knit family descends into vicious arguments and accusations, with Warda being suspected of infidelity, the men on both sides of the family indignantly refusing to take DNA tests, and Amira concocting wild schemes to protect both her parents and ultimately take revenge on the person deemed guilty of bringing disgrace on the family.

Despite the impressive shot of Amira and her boyfriend against the city (above, a cropped image from the widescreen film), the film opts for crowded interiors most of the time–though not as limited as the paddy-wagon of Clash. Small apartments, narrow alleyways, and above all the visits to the prison create a claustrophobic atmosphere where nature and the bustle of society in the city are largely eliminated.

The prison scenes involve extended shot/reverse-shot conversations between Nawar and his family members through a glass barrier.

Shot with telephoto lenses, the scenes use shallow focus to concentrate our attention on the central characters. At the same time, though, reflections and planes of action out of focus create a sense of cramped space and similar conversations going on in a cramped room. Here Nawar suggests that he and Warda have a second child, since an opportunity to smuggle out some of his semen again. Amira’s delight at the idea and Warda’s doubtful expression set up the disastrous revelation to come: that Nawar cannot in fact be Amira’s father.

Checking Diab’s filmography on IMDb, I was surprised to learn that he is the main director on the current Marvel streaming series, Moon Knight. I had been completely ignoring this show, since I have little to no interest in the MCU. I did notice some comments by Egyptological friends on Facebook that the hieroglyphic texts were authentic (an important chapter from the so-called Book of the Dead), as attested by actual Egyptologists. One reviewer commented, “Hollywood has had a problem with how Egypt is represented in both film and TV. ‘Moon Knight’ has done a superb job with episode three, showing Egypt as an actual modern civilization as opposed to a barren wasteland of only sand with a yellow tinted filter over it.” He does not seem to have noticed that this might be due to the fact that an actual Egyptian director was chosen.

I suppose this is not terribly surprising, since for years there has been a trend toward Hollywood producers suddenly elevating talented foreign and indie directors into the ranks of makers of big franchise films. Taika Waititi went from What We Do in the Shadows and Boy to Thor: Ragnarok and Chloe Zhao from Nomadland to Eternals. (I list a considerable number of similar leaps from the festival scene to the world of blockbusters in my entry on Waititi’s rise to international fame.) Still, Diab seems a strange choice. Maybe Clash was sufficient demonstration that he could do epic scenes of violence. I suppose I shall have to give Moon Knight a look.

Hit the Road (2021)

For years now we’ve been blogging about Panahi films (click on Directors: Panahi in the Categories at the right). Now we have another, but it’s not by Jafar. Panah Panahi is his son, and this is his feature debut. Panah began by making shorts, worked as a set photographer, and later as an editor, most notably on his father’s latest feature, Three Faces.

Hit the Road (the Farsi title is more literally translated as “Dirt Road”) reminded me more of the films of Abbas Kiarostami than of the elder Panahi. Jafar worked as an assistant director on Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees (1994). Panah was only ten years old at that point, having been born in 1984, the year of Kiarostami’s early feature documentary, First Graders. The New Iranian Cinema came to world prominence later in the 1980s and into the 1990s. Jafar moved into directing features in 1995 with The White Balloon.

Growing up, Panah must have become familiar with the now-classic films of Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, as well as those of his father in the years before the latter’s arrest in 2010.

Hit the Road is reminiscent of the “child quest” films of the early years of the movement. In this case, though, the child in question is not the center of the plot, even though the rambunctious kid steals every scene he’s in. He’s accompanying his parents and older son on a road trip that occupies the entire length of the film. The older son is as quiet as his brother is noisy, but it gradually comes out that he is heading for a spot where he will join others being smuggled out of the country in search of better lives. The parents keep this a secret from the little boy, fearing that he will blurt out something that will draw attention to their goal.

The film is a skillful blend of suspense on that account, of a poignant if quarrelsome love among the family, and a good deal of comedy supplied by the little boy. Amid all the raucous exchanges there are quiet moments, as when during a rest stop the unnamed mother nags her older son about smoking too much while sharing a cigarette with him and asking what his favorite movie is. By this point we suspect that she fears that she will never see him again once they reach the border. (Richard Brody’s insightful review captures this mixture of tones.)

Unlike Amira, Hit the Road is shot entirely out of doors, and often in beautiful, bleak Iranian landscapes (top of entry and below).

At times the family’s SUV climbs hills in shots that recall those of Kiarostami’s films,especially And Life Goes On and The Taste of Cherries, as in the frame at the top of this section. (The literal translation of the Farsi title, Jaddah Khaki, is “Dirt Road.”)

The film has been critically acclaimed and successful on the festival circuit, winner Best Film at the London and Mar del Plata festivals. It seems likely that we will now have two Panahis to report on from future festivals.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire, 2022)

I found Denis’s latest a frustrating and puzzling film for almost its entire length. It reminded me of a similar experience I had with Pablo Larraín’s Ema at the 2019 Venice International Film Festival. I described my initial reaction to that film at the time: “While watching it, I could not discern much of a plot or even a coherent character study.”

Denis’s film, shown outside France under the rather baffling title Fire, starts out innocently enough with a scene of lovers, played by Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon, enjoying a blissful, solitary, wordless swim in the ocean. This sets up the “amour” part of the original title. Surprisingly enough, this idyllic sequence, the most visually attractive of the film (above and at the bottom of the entry) was shot during the pandemic on a phone with just the two actors, the director, and the cinematographer present.

Sara and Jean are long-time lovers, and their happiness together continues as they return to their Parisian flat. Soon, however, Sara’s previous lover, François, re-enters their life. He has asked Jean, who has in the past been in prison for some unspecified crime, probably financial, to join him in a athletic scouting agency. Coincidentally, Sara has spotted François in the street, an encounter that seemingly stirs up her old passion for him. She mentions the encounter to Jean, but treats it as a minor thing, expressing pleasure that Jean has been given an opportunity to go into business with his old friend.

From that point the film becomes largely a series of increasingly fraught arguments, as Sara seems to pledge her devotion to both men while resenting the jealousy that they both increasingly feel. All three are revealed to be unpleasant characters acting unwisely, and I, at least, wondered what the point of it all was. The plot seemed to be the classic love triangle, with the question being which man Sara should end up with and whether she will make the right decision–and the issue seeming not to make a great deal of difference for the viewer.

I don’t want to say any more about the plot, since the point of it is to figure out at the very end what Denis had been up to all along. I realized that she was undercutting our expecations about the very clichés that she had presented to us. Apparently I was right. In an interview with Denis, Joseph Cronk mentions that “In an interview in the press notes for the film, you mentioned that the film’s simplicity was ‘a way of foiling clichés.'” Indeed. I’m not sure that many people in the audience with whom I saw the film got the point. I heard some grumbling among the spectators as we left the theater.

It is rather odd to make a film where the audience can “enjoy” it only in retrospect.

I should add that the title Fire does not help a bit.I don’t know who came up with it, but it’s misleading. As Denis has pointed out in interviews, there is no equivalent word to acharnement in English. In the interview mentioned above, Cronk suggests that “With Love and Fury” might be a better title. Denis responds:

No, archarnement doesn’t mean fury. There’s no direct translation, but it means something–from our body, something from your flesh. A sort of tension in the flesh. Fury is something different than acharnement. When I tried translating Avec amour et acharnement, I found no English word I liked that could convey what acharnement means. But Stuart [Staples, the composer] had written the song “Both Sides of the Blade,” and I thought this would be the perfect English title.”

Actually I don’t think “Both Sides of the Blade” would give the spectator much of a clue as to what’s going on in the film. Keeping in mind Denis’s explanation of the French title, however, would.

The quotations from Joseph Cronk’s interview appear in the latest issue of cinema scope, #90 (July 31, 2022), “Not on the Lips: Claire Denis on Avec amour et acharnement.”

Thanks as always to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and all the staff and volunteers of the Wisconsin Film Festival.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire).

Oscar’s siren song: The revenge

King Richard

The Oscars are upon us again. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences may have decided that “Music (Original Score)” is one of the categories not important enough to show live along with the rest of the awarding of the golden statuettes. We, of course, think this is absurd. (Will the Oscar ceremony gain a single extra TV viewer through this tactic?)

We welcome back our friend and colleague Jeff Smith to continue his annual comments and predictions concerning the nominees in both musical categories: song and original score. This year he has, if anything, outdone himself in providing insights into the historical contexts and the formal qualities of the ten nominees.

‘Tis the season to pass out little gold men to people in gowns and tuxedos. This year’s Oscar ceremony is scheduled to take place on Sunday night, March 27th. And this is about the time when I offer my annual assessment of the nominees in the music categories.

The title I’ve given this blog post might appear to represent a failure of imagination. After posting the first of these surveys, I opted for a sequelitis motif by using Roman numerals and corny words like “Return.” Yet this year’s sequel title seems all too apt. The producers of the Academy Awards have been winnowing away the amount of airtime given to the music awards in the past two years. They no longer present all five of the Best Original Song nominees as part of the broadcast. This year the award for Original Score will be prerecorded before the broadcast and the winner announced in between other, presumably more important awards.

If the Academy Awards doesn’t seem to care about these categories, then why should I? Well, because as a scholar and educator, this is what I do. Consider this blog post the petty revenge of someone who believes these categories still matter, even if the organization sponsoring the awards doesn’t seem to think so.

In the case of the award for Best Original Score, there will be some bitter irony in the fact that we’ll never see the faces of the composers on the big five-way split screen used to show nominees. But we’ll hear their scores played as walk-up music if Penelope Cruz wins for Best Actress. Or if Greig Fraser wins for Best Cinematography. Or Encanto wins for Best Animated Film. Or Jane Campion wins for Best Director. Or Adam McKay wins for Best Original Screenplay.

At the end of each award preview, I’ll make an educated guess as to who the winner of the category will be. All the usual caveats apply. These predictions are not intended for wagering purposes, I offer the usual disclosure that my predictions over the years typically yield one right and one wrong. (It’s up to you to figure out which is which.)

Lastly, a warning of some spoilers. I do my best to try to avoid giving away too much information about a film. But sometimes it is unavoidable if you want to get into the nitty gritty of the choices composers make in how they score their films.

The Susan Lucci of songwriting

Last month, Diane Warren earned her 13th Oscar nomination for Best Original Song, the most by a woman in any category without a win. This isn’t the most, though, in the music categories as composers Thomas Newman and Alex North both earned 15 nominations for Best Score without ever taking home Oscar. Last April, Warren told Billboard that she the old saw about it being “nice to be nominated” was true, but that she really would like to finally win an Oscar. Said Warren, “I’m like a sports team that has lost the World Series for decades. This is 33 years since my first nomination.” Warren’s record begs comparison with soap opera star Susan Lucci, who earned 18 Daytime Emmy nominations for her role as Erica Kane on All My Children before finally winning the award in 1999.

Warren’s current nomination is for her song, “Somehow You Do,” which is featured in Rodrigo Garcia’s drama about opioid addiction, Four Good Days. Sung by Reba McEntire, Warren’s number is a countrified version of the sort of power ballad that the tunesmith has specialized in for decades. The first verse is modestly arranged for two guitars, one an acoustic and the other pedal steel. The song gradually adds more texture as it nears the chorus, with the bass adding some bottom end and a chorus punching up McEntire’s lead vocal.

The second verse continues to build with the addition of a drum kit that firmly establishes the song’s 6/8 meter and slow tempo. The song’s bridge introduces a contrasting melody and roughens up the sweetness of McEntire’s voice with some pulsating power chords played by an electric guitar. This prepares for the requisite key change as the song shifts to the final verse and chorus. The tune reaches its emotional peak here and then gradually tapers down. A brief coda returns us to the spare sound of McEntire’s voice accompanied by an acoustic guitar.

The song is very well-crafted if a bit by the numbers. It is a testament to Warren’s mastery of her craft that she finds new ways to enliven the venerable AABA structure of classic songs and fit them to the dramatic needs of the films she works on.

Yet Warren’s chances of winning seem to be hampered by a couple of factors. If you asked yourself, “What is Four Good Days?”, you are not alone. The film garnered little attention from critics and fans, earning less than $900,000 during its theatrical release. Moreover, although McEntire is a huge star in the world of country music, that probably won’t cut much ice for voters in the Academy music branch who represent a different industry demographic.

There seems little doubt that Warren has a dedicated following within the music branch. However, although it is big enough to consistently yield nominations, it isn’t large enough to deliver the big prize. Warren likely will have to content herself with “It’s nice to be nominated.” If she starts to feel too downhearted, Warren can console herself by looking at her royalty statements for “Rhythm of the Night.” Or “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing.” Or “How Do I Live.” (You get the idea…)

The Legends (and I don’t mean John, Chrissy, Luna, and Miles)

The next two nominees are among pop music’s biggest icons, representing more than ninety years of combined experience in the biz. A bit surprisingly, though, both artists also are first-time Oscar nominees.

First up is the man who epitomizes Northern Soul: Irish singer and songwriter Van Morrison. Morrison is nominated for “Down to Joy” from Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast. Like Branagh, Morrison was born and raised in Belfast. He also has been closely associated with the city throughout his career, receiving the monikers of “the Belfast Cowboy” and “the Belfast Lion.” The early peak of Morrison’s career also coincides with the onset in 1969 of “the Troubles” depicted in Belfast. Besides “Down to Joy,” Branagh selected eight other Morrison tracks for the film’s soundtrack, many of them lesser-known tracks like “Caledonia Swing” and “Carrickfergus.” By digging deep into Morrison’s catalog, Branagh is not only able to provide a musical biography of his childhood, but also indicates how deeply Van the Man’s music was woven into the fabric of everyday life in Belfast.

Morrison’s “Down to Joy” also shows the durability of AABA form, albeit in this case channeling the sound of his early mid-tempo rockers like “Caravan” and “Domino.” The latter recordings are among the songs that would cement Morrison’s status as a Celtic interpreter of the revue style of sixties soul music, especially the Stax sound epitomized by singers such as Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding. Morrison based his entire career on melding those influences with more native elements of Irish folk music. For nearly sixty years, Morrison has demonstrated that the idiom of sixties soul seems almost timeless, an impression confirmed by even more modern practitioners, like Sharon Jones & the Dap Kings or Nathaniel Rateliff & the Night Sweats.

Appearing over the end credits, “Down to Joy” neatly encapsulates the overall tone of Belfast and its mix of nostalgia, melancholy, and hope. At the end of Belfast, young Buddy and his family have been displaced by “the Troubles,” forced to relocate by threats of IRA retaliation. Their journey to England is colored by the pain of family separation. Yet it also represents a horizon of new possibilities. “Down to Joy” reflects that latter sentiment with lyrics describing a new morning after a dark night, and the glory and gratitude expressed through Buddy’s child-like naivete.

So, what are the chances that Van the Man wraps his hands around a small golden dude? Not very good, if you ask me.

Don’t get me wrong! Morrison albums of the late sixties and seventies – Astral Weeks, Moondance, Tupelo Honey, Saint Dominic’s Preview – are stone cold classics. It’s Too Late to Stop Now is among the finest live albums ever recorded. Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” is my wife’s very favorite song ever!

I’m a Van fan, but his public statements about the United Kingdom’s Coronavirus restrictions have probably killed his chances of winning an Oscar. If younger members of the Academy know Morrison at all, it is likely as a conspiracy crank who is now recording with equally obnoxious anti-vaxxer Eric Clapton. I just can’t see Academy voters giving Morrison a platform to air his views on social distancing and lockdowns. If they did, it would produce the kinds of news clips and headlines that the Academy would like to avoid. Just imagine the public response to an acceptance speech in which the boos from the crowd rain down on the winner. I imagine that a lot of folks in the music branch just can’t bring themselves to vote for Morrison in the current political landscape. And, even as a lifelong fan, I can’t really blame them.

The third nominee for Best Original Song is “Be Alive” by DIXSON and Beyoncé Knowles Carter. The song appears in the end credits of King Richard, the biopic about Richard Williams, the father of tennis phenoms Serena and Venus. The tone of the music and lyrics succeed in doing something the film itself struggles to do, namely give voice to the two women who end up rewriting the record books of professional tennis.

In contrast, King Richard casts Williams the elder as a Svengali figure shepherding his young prodigies into the world of big-time sports. He acts as the girls’ agent, manager, coach, and protector, shielding Serena and Venus from the sorts of predations that characterize an industry with a bad reputation for chewing up and spitting out young talent. The lyrics of “Be Alive” speak to the family’s sense of fierce independence and Williams’ own “bootstrap” mentality. This is evident in couplets like:

Couldn’t wipe this black off if I tried

That’s why I lift my head with pride

Later, Beyoncé sings the praises of sisterhood, a theme that can be heard in some of her biggest hits, such as “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” or “Independent Women Part I,” the latter recorded as a member of Destiny’s Child.

With its steady marching tempo borrowed from the Doors’ “Five to One” and Beyoncé’s soaring vocals, “Be Alive” bespeaks a mood of strength and defiance. Yet, it isn’t as well placed as some of the other songs in the category and, unlike many of Beyoncé’s popular records, it also isn’t the kind of earworm that lights up record charts. “Be Alive” peaked at #40 in Billboard’s Hot 100, likely a disappointment considering how well King Richard has performed in other audience metrics.

Come Sunday, I suspect that Beyoncé will likely go home empty handed. Like Diane Warren, she’ll need to console herself with the mantra “It’s nice to be nominated” and the many other Grammys, ASCAP, Billboard, BET, MTV, and American Music Awards that line her trophy case.

The Young Bloods

The final two nominees had big years in the world of entertainment in 2021. An Oscar would put a capper on a period of creative ferment that’s the envy of most singers and songwriters. Yet, for these two performers, it just seems like another day at the office.

Lin-Manuel Miranda received his second Oscar nomination for “Dos Oruguitas,” one of several songs he wrote for the Disney animated musical Encanto. The song is performed by Columbian singer Sebastián Yatra and appears in a flashback that dramatizes Abuela Alma’s tragic backstory. As a young woman, Alma, her husband Pedro, and their triplets attempt to escape their village after war breaks out. During their journey, they are beset by armed horsemen. The refugees scatter, but Pedro is killed when he halts the charging caballeros, presumably to ask for mercy for himself and his family. A candle Alma is holding protects the rest of the group, and its magical properties transform their future home into the “Casita,” a fantastic space where its denizens are revealed to have supernatural abilities and the house has a mind of its own.

The sequence itself is reminiscent of similar moments from films made by Disney’s friendly rival, Pixar. The montage that encapsulates an entire life in a couple of minutes of screen time recalls the opening of Up (2008) which depicts the long, happy marriage of Carl and Ellie until her illness and untimely death. The song that accompanies a flashback explaining the source of a character’s trauma and grief is also seen in Toy Story 2. Cowgirl Jessie relates how she once was her owner Emily’s favorite doll, but ends up forgotten and left behind when Emily grows up. This is all set to the strains of Sarah McLachlan’s “When She Loved Me.” The montage from Encanto nicely fuses together both these narrative devices but gives them a Latin pop spin.

Like “Somehow You Do,” “Dos Oruguitas” begins quietly with a brief introduction played on an acoustic guitar. The slight syncopation of the guitar figure, though, gives it a bit of Hispanic flair. As Yatra’s voice enters, the song’s chord structure follows a chromatically descending bass line, a device that heightens the harmonic tension until it circles back to the tonic. The tune pauses briefly as Abuela confesses her guilt for forgetting what the purpose of the magic was for. Mirabel reassures her that the Madrigal family’s entire livelihood is due to the earlier sacrifices the Abuela made and the suffering she endured. When they embrace, “Dos Oruguitas” kicks back in with a slightly faster tempo and with fuller orchestration that includes strings, percussion, a chorus, and a harp. With the rift between Alma and Mirabel healed, the Madrigals band together to rebuild the “Casita.” The harmony created by the restored family bonds allows it to regain its sentient properties.

As an Oscar nominee, “Dos Oruguitas” has a lot going for it. It accompanies a very emotional scene of intergenerational reconciliation. It is a featured track on the Encanto soundtrack, which has spent the past nine weeks atop Billboard’s Top 200 album chart. And Lin-Manuel Miranda is on a roll having served as the director of Tick, Tick…Boom!, the musical biopic of Rent composer Jonathan Larson, and as the producer of In the Heights, the screen adaptation of Miranda’s own hit Broadway play.

Perhaps the only thing working against it is the fact that it’s been overshadowed by another song from Encanto. “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” is a certified pop culture sensation, spending five weeks as the #1 song on Billboard’s Hot 100, accumulating more than 300 million views on Vevo, and featured in 21 different languages on Instagram. Did Disney submit the wrong song for nomination? Maybe, but “Dos Oruguitas” still might been benefit from the reflected glory of its more popular sibling. This and the fact that Encanto is up for some other major awards have kept Miranda among the frontrunners.

The last nominee is the title song from the most recent entry in the venerable James Bond series, No Time to Die. The tune is performed by Billie Eilish and written by Eilish and her frequent songwriting partner, brother Finneas. Like Miranda, 2021 has been a good year for Eilish. Her new album Happier Than Ever topped the charts in 26 countries across the globe, including the US. It also earned two Grammy awards and landed on several year-end “best of” lists. In addition to her music, Eilish also appeared in two films: a concert film featuring songs from Happier Than Ever and a “behind the scenes” documentary distributed by Neon and Apple TV+ called Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry.

In some respects, Eilish seems like an exemplary contributor to the amazing catalog of songs written for the Bond canon. She is an immensely popular artist. She is also someone who could update the template for the series by adding emo, dream-pop, and electro-pop touches to the usual Bond formula.

In other respects, though, Eilish represents something of a departure from previous Bond songstresses. When one thinks of iconic Bond songs, one thinks of tunes like “Goldfinger,” “Diamonds Are Forever,” “Licence to Kill,” “Goldeneye,” “The World is Not Enough,” “Skyfall,” and “Another Way to Die.” What do these songs all have in common? They are all sung by women with big voices, belters like Gladys Knight, Tina Turner, Adele, Alicia Keys, and the two Shirleys: Bassey and Manson. In contrast, Eilish is known for a much softer style of singing: hushed, sensitive, and intimate. That seems fitting for a performer whose best-known album was inspired by lucid dreaming and night terrors. Yet it seems less well-suited for an almost mythic film character defined by his swagger, toughness, and even a streak of cruelty.

Yet, if there was moment to rethink the traits of the typical Bond song, this was certainly it. In retrospect, the selection of Eilish was a masterstroke by the Bond brain trust led by Barbara Broccoli, the current head of Eon Productions. As the last film to feature Daniel Craig as James Bond, No Time to Die not only caps off his five-film arc, but also serves as a reflexive meditation on the series as a whole. At one level, the explicit meaning of No Time to Die is both simple and banal: everyone dies. Yet, by making references to several earlier films in the series, the accumulated weight of intertextual resonances invests the many deaths that occur in No Time to Die with an unusual sense of depth and gravity.

No Time to Die begins with a scene where Bond visits the tomb of Vesper Lynd, the fellow agent featured in Casino Royale who helps Bond defeat the evil Le Chiffre. Lynd and Bond fall in love, but she proves to be a double agent working for a rival operative. At film’s end, Lynd sacrifices herself when she drowns in a locked elevator car that has submerged.

M then reveals that she was an unwilling accomplice, a victim of blackmail after her previous boyfriend was abducted and threatened.

Bond’s pilgrimage to Lynd’s grave presages several additional deaths in the film. Bond’s best friend, CIA Agent Felix Leiter, and his mortal enemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, are killed in separate incidents. Even Bond himself perishes in the climax of No Time to Die. He sacrifices himself to foil a scheme by Lyutsifer Safin to unleash a bioweapon upon the world that is transmitted by touch and kills its victims based upon their DNA. After a missile strike is launched against Safin’s compound, Bond stays behind to assure that the silo’s blast-proof doors stay open. Bond’s gesture that not only saves the world but allows his current paramour, Madeleine Swann, and the young daughter he never knew he had, to safely escape the island.

Given how much of No Time to Die is pervaded by a sense of grief and sorrow, the decision to include a title song reflective of the film’s solemnity and melancholy makes perfect sense. Like some of the other nominees, Eilish’s tune begins slowly and quietly with a piano plunking out a repeated four note motif accompanied by strings and low brass. Eilish intones the first lyric, “I should have known” in a sung whisper. The serpentine melody unwinds through the verse and chorus, eventually taking Eilish into the upper range of her soprano on the lines:

Fool me once, fool me twice

Are you death or paradise?

You’ll never see me cry

There’s just no time to die

Just as the chorus ends, a thunderous bass chord enters, and the opening four note motif returns. The song continues to build, and more instruments are added as the song reaches its second chorus. Our four-note motif returns once more, but this time played in full orchestral splendor by the strings and the full brass section. The musical bombast ultimately fulfills the remit of other classic Bond songs. Eilish even follows suit by loudly belting out the chorus, revealing a power and huskiness to her voice that most of her fans probably hadn’t heard before.

“No Time to Die” finishes with a coda that returns to the sparse arrangement of the tune heard at the start. Eilish also goes back to the shivery murmur that is her stock in trade for one last iteration of the chorus’ last two lines.

No Time to Die larger themes of love, death, grief, and martyrdom presented a special challenge. Billie and Finneas rise to it beautifully. Moreover, the Eilishes also cleverly incorporate musical elements that evoke the harmonies and tonalities of John Barry’s best-known scores in the series. The four-note motif that serves as a spine for the song sounds like it could have easily been drawn from From Russia with Love, Goldfinger, or Thunderball. They also conclude the song with an electric guitar strumming an EmMaj9 chord, the so-called spy chord that Vic Flick plays at the end of the famous James Bond theme that started it all.

Does this mean that “No Time to Die” is the odds-on favorite to win? Perhaps, but it also seems to be overshadowed by another song, much as “Dos Oruguitas” was. In this case, the song was written for a completely different Bond film and mostly functions as an Easter Egg for die-hard fans of the series. It is “We Have All the Time in the World,” which was written by John Barry and Hal David and performed by Louis Armstrong over the end credits of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1968). Notably, the song appears just after Bond’s new bride, Tracy, has been killed in a drive-by shooting by Blofeld and his assistant, Irma Bunt. It is yet another evocation of death in No Time to Die with Tracy, like Vesper Lynd, implicitly included in the film’s mounting body count. Notably Hans Zimmer’s score for No Time to Die incorporates the melody to “We Have All the Time in the World” in three of the cues he wrote for the film. Indeed, long-time fans like me might well recognize the older Bond song in Zimmer’s score much more readily than the new one specifically written for it.

Prediction for Best Original Song

An Oscar would confer EGOT status on Lin-Manuel Miranda, a distinction held by just a handful of other entertainment luminaries. In fact, because Miranda also won a Pulitzer Prize for Hamilton and a MacArthur Genius Award, an Oscar would place him in entirely unique category. Say hello to the MacPEGOT.

Yet, although an award for “Dos Oruguitas” would make history, recent Oscar ceremonies have favored Bond songs. Adele won for “Skyfall” in 2013. Sam Smith repeated the feat with “Writing’s on the Wall” in 2016. “No Time to Die” also has already won a Grammy, a Golden Globe, and more than a dozen awards from prominent critics’ societies. Eilish is also a newly minted pop star, whose personal story is the kind of underdog narrative that Oscar voters seem to like.

If you are looking for a dark horse in the field, you might consider “Be Alive.” (Although when would you ever consider Beyoncé a dark horse for anything?) But I am sticking with the favorite. On Sunday, I expect Eilish to win. It is the clubhouse leader in terms of the betting markets and also my personal favorite among the field.

An ode to the new cleffer

One of the first things you might notice about this year’s slate of nominees for Best Original Score is the relative absence of the “usual suspects” in the music branch, such as Thomas Newman, Alexandre Desplat, or John Williams. Between them, these three composers have received a total of 78 nominations. Admittedly, only one of the five nominees this year – Germaine Franco – is a first timer. However, aside from Hans Zimmer’s twelve previous nominations, none of the other composers has received more than four.

Franco’s nomination is significant for other reasons. In February, she became the sixth woman nominated for Best Original Score and the first Latina. The field has a decided international flair with nominees from Britain, Germany, and Spain joining two Americans.

Of the five nominees, Alberto Iglesias’ music for Parallel Mothers (above and at bottom) comes closest to the style of a classical score. Yet it also presents a slight departure from those norms in its use of a chamber orchestra with most cues arranged for strings, piano, and the occasional wind instrument. Some feature the strident bowing style associated with Bernard Herrmann’s famous score for Psycho (1960). Others create lush combinations of strings and solo piano, an approach reminiscent of Frank Skinner’s music for older Universal melodramas like All That Heaven Allows (1956).

If that sounds a bit odd, it shouldn’t. Alfred Hitchcock and Douglas Sirk have been prominent influences on Pedro Almodovar’s cinema over the years. Parallel Mothers is the thirteenth film that Iglesias has scored for the great Spanish auteur. The composer admits that Almodovar’s films are always rooted in melodrama. But Parallel Mothers also had the generic trappings of a thriller, and his music strived to infuse scenes of psychological intimacy such that they crackled “with energy and light.” Iglesias also sought to accentuate the protagonists’ intertwined lives at a macro-level, using parallel musical structures to underscore how Ana enters and exits Janis’ life at several points in the film.

Iglesias is a four-time nominee and his score for Parallel Mothers is among his best. But I fear this is not his year. Parallel Mothers is among the biggest longshots in the Oscar betting markets not only for Iglesias in the Best Score category but also for Penelope Cruz as Best Actress. Moreover, the fact that Spain snubbed Parallel Mothers when submitting its nominee for Best International Feature Film also doesn’t bode well. Iglesias is once again a very deserving nominee whose work is likely to be overlooked in a highly competitive field.

Stretching the classical style: Incorporating novel idioms

Nicholas Britell earned his third Oscar nomination for Don’t Look Up, Adam McKay’s acrid satire of contemporary politics and media. The film’s dark humor and its apocalyptic conclusion undoubtedly posed a conceptual challenge for Britell. How do you preserve the comedic qualities of the story while still respecting the existential crisis that hints at larger issues around climate change, COVID, and the increasing distrust of science and medicine? As Britell acknowledges, he was “unprepared for the wild ride” that viewers experience over the course of the film. Britell’s solution? A hyperbolic paean to science, a smattering of wacky electronic sounds, some rollicking big band jazz, and garage-band style Farfisa organ.

In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Britell notes that two cues were especially important in articulating the overall concept for the score. Even before production had wrapped, Britell created a demo cue entitled “Overture to Logic and Knowledge” that McKay played on set to enable the cast to get in the right frame of mind.

The piece unfolds as a canon performed on a piano that’s been recorded with heavy reverb. After the statement of the initial theme, Britell interweaves additional voices in contrapuntal harmony, approximating the sort of mathematical precision one associates with Bach fugues. Afterward, Britell then tried to suss out what the opposite of that compositional style might be, eventually landing on big band jazz. The idiom is evident in the film’s main title, which features walking bass, a simple brass and bass saxophone riff, and a soaring trumpet obligato. Another cue – “It’s a Strange Glorious World” – reprises that big band style, yet further estranges the viewer from the serious global crisis dramatized in Don’t Look Up with the use of banjo and toy piano for instrumental color.

Britell saves his most savage musical satire for a theme written for Peter Isherwell, the billionaire tech genius played by Mark Rylance.

The composer arranges the theme for celestas, toy pianos, Farfisa organ, and bass synthesizers. These instrumental colors suggest Isherwell’s childlike faith that new technology can solve all of humankind’s biggest problems. Of course, Isherwell exudes this relentless optimism to mask his real intentions. Isherwell proposes a foolhardy mission to try and capture the streaking comet rather than deflecting or destroying it. He does so to feed his corporate greed as the comet possesses rare minerals that Isherwell hopes to harvest for use in his production of microchips.

Britell’s score displays incredible musical sophistication even as it is asked to underscore scenes that occasionally seem silly or in which the satire seems all too crude. That being said, I have some doubts that it will win for Best Original Score. This is not to gainsay Britell’s extraordinary ingenuity in devising his music. Rather, it is just the brute reality that other films have better odds in what seems to be a close race.

Germaine Franco’s music for Encanto also pushes the bounds of the classical score. In this case, though, it does so by incorporating various styles of Latin pop music rather than using big band jazz. To be sure, there was a strain of this type of composition in earlier eras, Think, for example, of the music written by Henry Mancini, Nelson Riddle, and Quincy Jones for films of the 1960s. That music, though, reflected the predominant Latin pop styles of the period, which included congas, rhumbas, cha-chas, sambas, and bossa novas.

In contrast, Franco drew upon a different repertoire of Latin rhythms to fashion her score for Encanto, including some folk music styles specific to the film’s Colombian setting. These not only include more familiar idioms like salsa, but also more modern developments like reggaeton. The latter is a style that originated in Panama in the 1990s and mixes hip-hop beats with Jamaican riddims. It rapidly spread through Spanish-speaking countries in the Caribbean.

In Encanto, reggaeton can be heard in Luisa Madrigal’s big number, “Surface Pressure.” The song, of course, was written by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Franco then incorporated the style into certain cues to ensure a strong sense of unity between the mood and vibe of the songs and those of the score.

Other cues, however, are written in folk styles native to Colombia with Franco once again taking her cues from the rhythms of Miranda’s songs. Encanto’s opener, “The Family Madrigal,” is an up-tempo vallenato song played in standard 2/4 meter. It features marimba, three-button accordion, and guachara, a Colombian percussion instrument played by rubbing a fork over a wooden, ribbed stick. Mirabel’s “I want” song, “Waiting on a Miracle,” uses bambuco rhythms. It unfolds in a fast triple meter characteristic of the idiom. As the only song featuring this rhythm, Miranda used it to further underline how Mirabel feels separated from her family due to her lack of a special gift for magic.

Perhaps Franco’s most important gesture, though, was using cumbia rhythms to underscore Mirabel’s movement. Cumbia is popular style throughout South America but has its origins among enslaved African populations on the coasts of Colombia and different Caribbean nations. It uses a clave rhythm common in Afro-Cuban music. As the style spread throughout Colombia in the early 1900s, musicians incorporated indigenous drums and wind instruments, including tambora, llamador, and gaitas. As Franco has noted in interviews, she uses the cumbia to accompany Mirabel’s first entrance into the “Casita.” From that point on, according to Franco, “The rhythm of the cumbia becomes the forward motion of her trying to find a solution to the problem.”

I suspect Franco’s fellow composers in the music branch are as impressed as I am by her attention to details of rhythm and orchestration. To get the precise tone color needed for some of these Latin pop and folk styles, Franco had a special marimba native to the Choco rainforest region of Colombia disassembled and shipped to her in parts. After it was put back together, Franco played the marimba herself, two mallets in each hand.

Encanto isn’t the favorite to take home the prize for Original Score. But if you’re looking for a potential surprise on Sunday night, Franco seems to be in the best position to pull an upset.

Rock of the Westies

Many pop music fans know Jonny Greenwood from his work as a songwriter and lead guitarist in the British rock band, Radiohead. Greenwood, though, has also established a considerable reputation as a film composer. He is perhaps best known for his work with director Paul Thomas Anderson, who has collaborated with Greenwood on his past five projects. Beginning with There Will Be Blood (2007), Greenwood went on to score The Master (2012), Inherent Vice (2014), Phantom Thread (2018), and Licorice Pizza (2021).

In February, Greenwood earned his second Oscar nomination for Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog. Much like the rest of the film, Greenwood’s score works against many of the conventions of the classic Hollywood Western. Many studio-era oaters developed their scores around orchestrated versions of tunes in the cowboy songbook or around Coplandesque rhythms and harmonies. Both these approaches strived to evoke the majesty of the films’ visuals, which often featured mountain vistas, endless prairies, and sunlit horizons.

Instead of looking to the “sweeping strings” style used in older Westerns, Greenwood was inspired by the atonal brass music that was used in old Star Trek episodes to underscore the exploration of unknown planets. When Peter ventures into the mountains and discovers a dead cow, Greenwood accompanies these scenes with a dissonant French horn duet to highlight the strange and forbidding quality this has on the impressionable teenager.

Similarly, instead of a big string sound, Greenwood opted for smaller ensembles, occasionally writing things for six cellos or four violas. Greenwood also plucked strings of a cello as a correlate for Phil’s onscreen banjo playing. Here again, the goal was to create a tone color that seemed just slightly off, emphasizing microtonal inflections to create a sound that was somber yet sinister.

Phil’s banjo playing also furnishes one of the most memorable scenes in The Power of the Dog. Peter’s mother, Rose, initially seems ill at ease after coming to live with George and Phil on the brothers’ ranch. At one point, she seats herself at the piano and proceeds to struggle through a piano reduction of Johann Strauss Sr.’s “Radetzky March.” Campion then cuts to Phil sitting in his bedroom offscreen. Phil then picks up the melody of the Strauss piece on his banjo, playing it almost effortlessly and improvising his own coda. In a test of wills, Phil’s virtuosity humiliates Rose, who increasingly turns to alcohol to soothe her emotional wounds.

Because of this scene, Greenwood used a detuned mechanical piano as a musical timbre associated with Rose.

To produce this effect, Greenwood used computer software to create the sound of a piano roll for his pianola. Then, as the music was played back, Greenwood used a tuning wrench to slightly alter the pitches to create a sound akin to the honkytonk pianos scene in the saloons of older Westerns. For Greenwood, the sound proved perfect for Rose’s character arc. As he states in an interview for Variety, “Not only is her story wrapped up in the instrument, but it was also a good texture for her gradual mental unraveling. I recorded hours of this stuff – poor Jane (Campion) had to hear quite a lot of it.”

Greenwood’s modernist take on the typical Western score makes him one of the top contenders in this year’s Oscars. Of course, it doesn’t hurt that Greenwood wrote music for two other nominated films: Licorice Pizza and Pablo Larraín’s Princess Diana biopic, Spencer. The betting markets have Greenwood as a longshot. However, since The Power of the Dog leads the field with a dozen nominations in all, Greenwood could prevail in the event of a Dog sweep.

Today’s sounds for tomorrow’s people

The last nominee for Original Score is the current favorite. Hans Zimmer earned his thirteenth Oscar nomination for Dune, Denis Villeneuve’s big budget adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic science-fiction novel. As Zimmer notes in a New York Times profile, he self-consciously rejected the musical style associated with the Star Wars series and its many imitators. Those scores looked to the past for inspiration, finding it in Gustav Holst, Igor Stravinsky, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and even Benny Goodman. Instead, Zimmer set himself an almost impossible task, trying to create sounds that no one had ever heard before.

The result is a score that Darryn King calls “one of Zimmer’s most unorthodox and most provocative.” The composer reports that he spent days contriving new sounds, sometimes commissioning the construction of new instruments or using conventional instruments in extremely unusual ways to get the effect he desired. Although synthesizers keep the score rooted in Zimmer’s pop music past, he combines these with several unusual sonorities that include Irish whistles, Indian bamboo flutes, and metallic scraping noises.

Many of these instrumental choices are keyed to aspects of Dune’s intergalactic setting. The rumble of distorted electric guitars evokes the seismic shifts occurring beneath the desert sands on the planet’s surface. Zimmer even used some of the environmental details to communicate what he wanted from the musicians performing on the soundtrack. Slide guitarist David Fleming reports that Zimmer told him for one cue, “This needs to sound like sand.”

Zimmer performed similar wonders in his use of other instruments. For the scene where the House of Atreides arrives on Arrakis, Zimmer recorded thirty bagpipes playing in a Scottish church. The added reverberance raised the volume of the ensemble to ear-splitting levels of 130 decibels. The highland players needed to wear earplugs to avoiding damaging their hearing. But Zimmer got the sound he wanted, the musical equivalent of a blaring air raid siren.

Zimmer’s desire to find new sounds not only altered the usual timbres of instruments but also of the voice as well. For Dune, Zimmer engaged the services of music therapist and singer Loire Cotler. To create the qualities Zimmer was seeking, Cotler drew on several non-Western singing styles. Her syncretic method combined Jewish niggun, South Indian vocal percussion, Celtic lamentation, and Tuvan throat-singing. The end result was a hybridized style that sounded wholly unique: a war cry expressed as though it were an ancient antecedent of Esperanto. Cotler tried to find a name for the new vocal technique, ultimately settling for the person responsible; she called it the “Hans Zimmer.”

Perhaps Zimmer’s most audacious gesture involved hiring winds player Pedro Eustache to build new instruments from scratch. Eustache created a 21-foot horn, a sort of modern version of the old animal horns fashioned into shofars and zinks during the Middle Ages. He also produced a contrabass version of the duduk, which King described as a “supersize version of the ancient Armenian woodwind instrument.”

What does it all add up to? A score that hits all the right notes in transposing Herbert’s imposing epic to the big screen. Zimmer’s music is at times quietly menacing, somber and pensive at other moments, and brooding but anthemic for Dune’s big action scenes. Zimmer’s score for Dune does not depict the kind of triumphalism found in Star Wars or other space operas. Rather, it opts to capture the elements of dark mysticism and doleful psychedelia that made Herbert’s novel a literary head trip in the 1960s. To be sure, Zimmer’s music doesn’t concoct earworms to evoke the sandworms. Yet it succeeds admirably where others have failed nobly. (If you think this is easy, just watch and listen to David Lynch’s misbegotten adaptation from 1984.)

Prediction

One could easily make the case for Germaine Franco to win for Encanto. The score and the album have dominated the popular music scene ever since the film was released in late November. Yet Dune stands a good chance at claiming several other craft awards, such as those for Sound and Production Design, which bodes well for Zimmer’s chances on Sunday.

In the world of film music today, the Burgomeister of Bleeding Fingers Music casts a shadow over the field as large as any of the luminaries who preceded him like Ennio Morricone, Jerry Goldsmith, or Dimitri Tiomkin. When I contemplate the sheer number of innovations Zimmer made in the music he composed for Dune, I can’t bring myself to bet against him. I think Hans takes home the Oscar on Sunday. He’ll walk away with another hunk of metal to scrape for the Dune sequel.

Once again, I want to give a shout-out to Jon Burlingame for his excellent coverage of Hollywood and international film music for Variety. As a subscriber, I always enjoy reading his work for the venerable trade journal, not just during awards season but year-round.

The Diane Warren interview with USA Today that I referenced can be found here. Additional interviews with Deadline and Gold Derby are found here and here.

Interviews with Lin-Manuel Miranda discussing the songs he wrote for Encanto can be found here , here, and here.

Vulture published a nice piece on the process of writing the title song for No Time to Die, which can be found here.

Alberto Iglesias discusses with work with director Pedro Almodovar here .

Nicholas Britell talks about his work Don’t Look Up with Indiewire and Variety here and here . One can find several interviews with Germaine Franco about her process on creating the score for Encanto. A sample can be found here, here, here, and here. A movie score suite featuring Franco’s themes for Encanto can be found here.

Jonny Greenwood talks with Variety about his collaboration with Jane Campion here and here.

The indie-music website provides an interesting review of Greenwood’s soundtrack for The Power of the Dog here.

Finally, Darryn King’s superb overview of Hans Zimmer’s score for Dune can be found here.

Parallel Mothers